Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

02 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

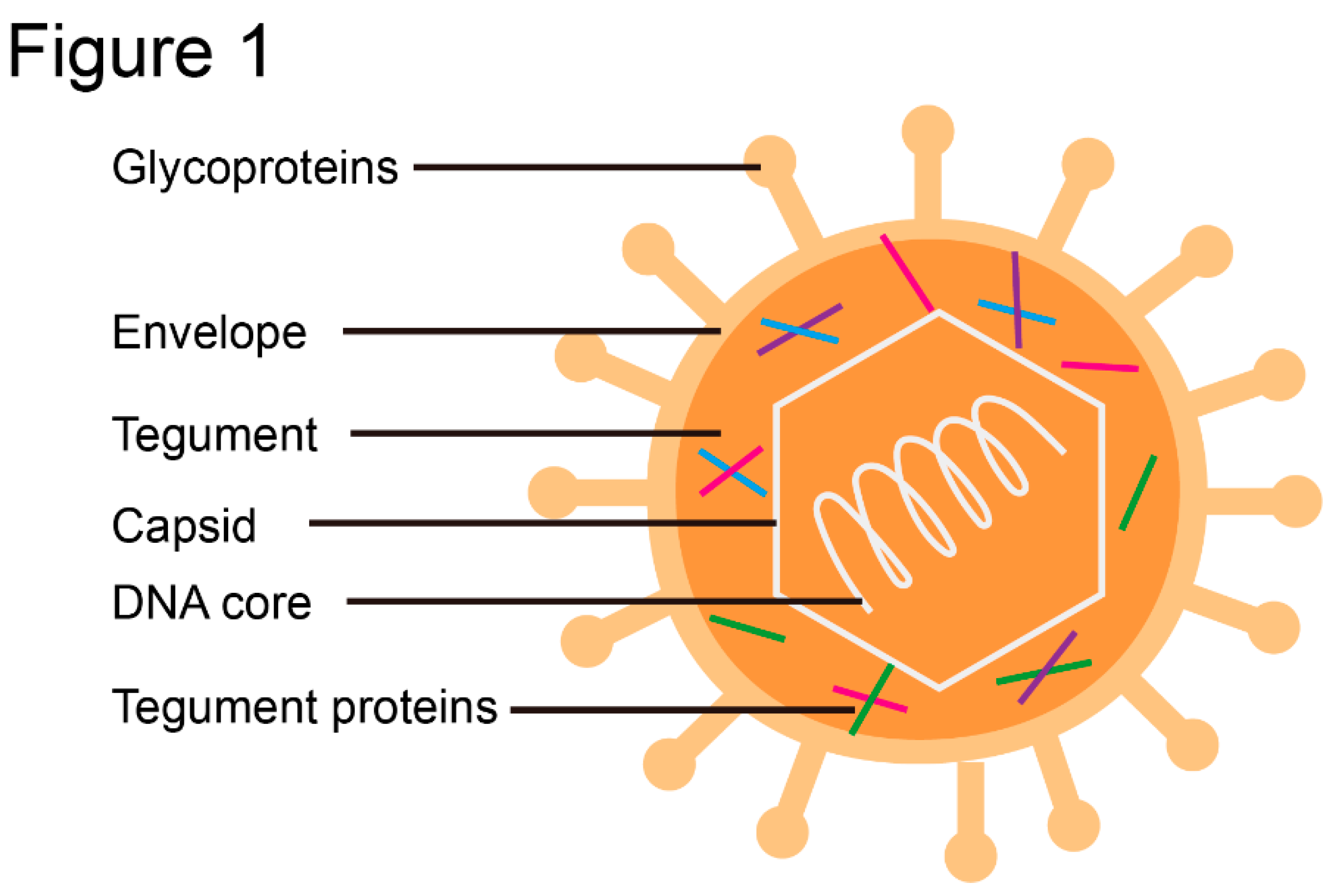

1. Introduction

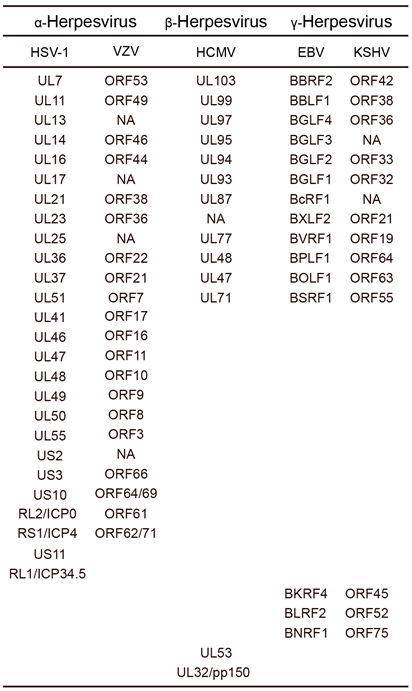

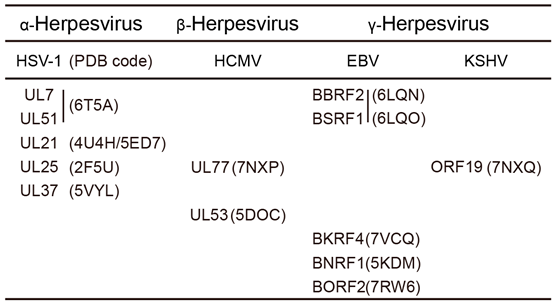

2. Structures of Common Herpesvirus Tegument Proteins

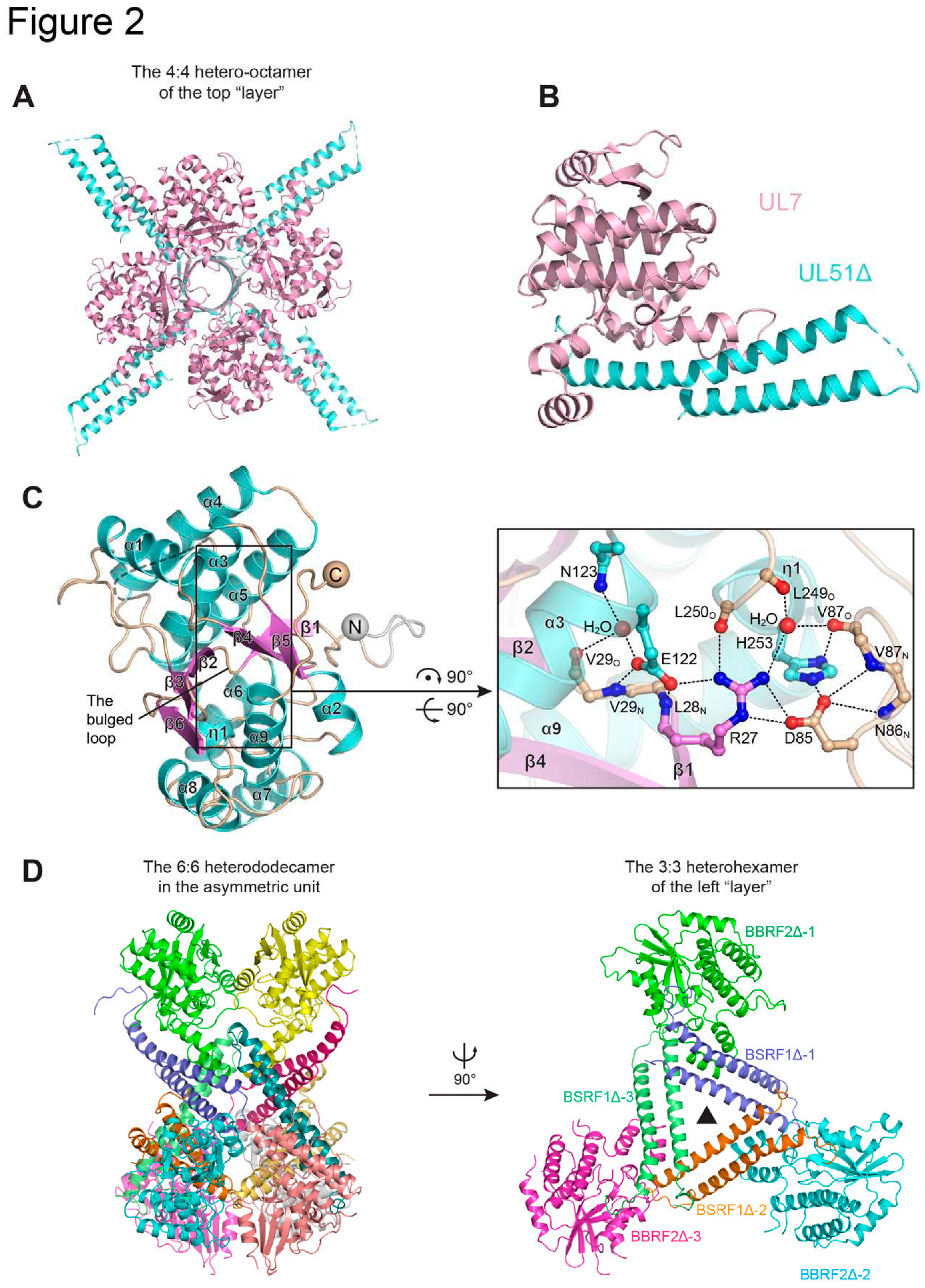

2.1. HSV UL7/UL51 and Homologs

2.2. Functional Hints from the UL7-UL51 and BBRF2-BSRF1 Complex Structure

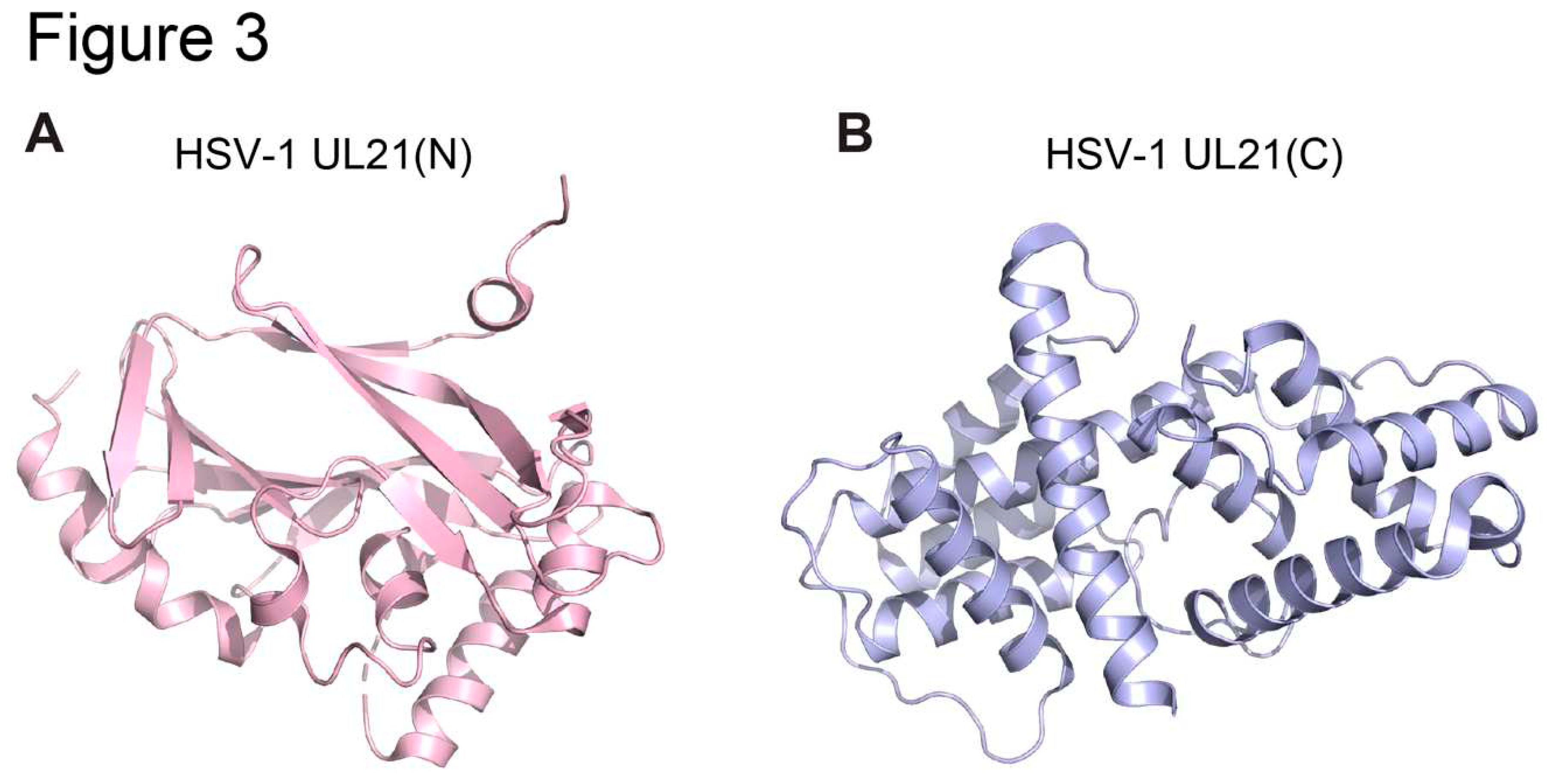

2.3. HSV UL21 and Homologs

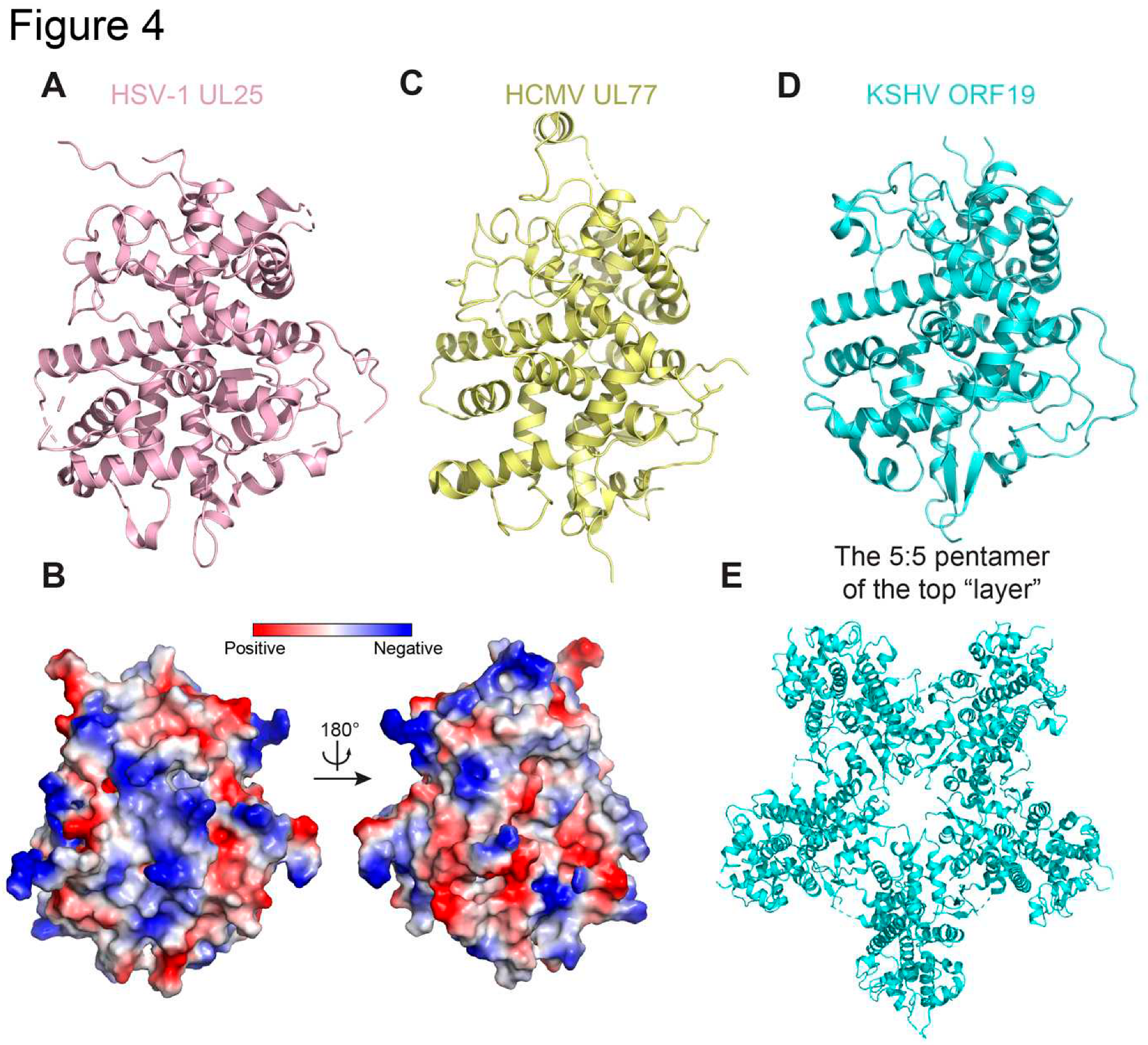

2.4. HSV UL25 and Homologs

2.5. HSV UL37 and Homologs

2.6. HSV Capsid-Associated Tegument Proteins and Homologs

3. Structures of Subfamily-Specific Tegument Proteins

3.1. HCMV UL50 and UL53

3.2. EBV BNRF1

3.3. EBV BORF2

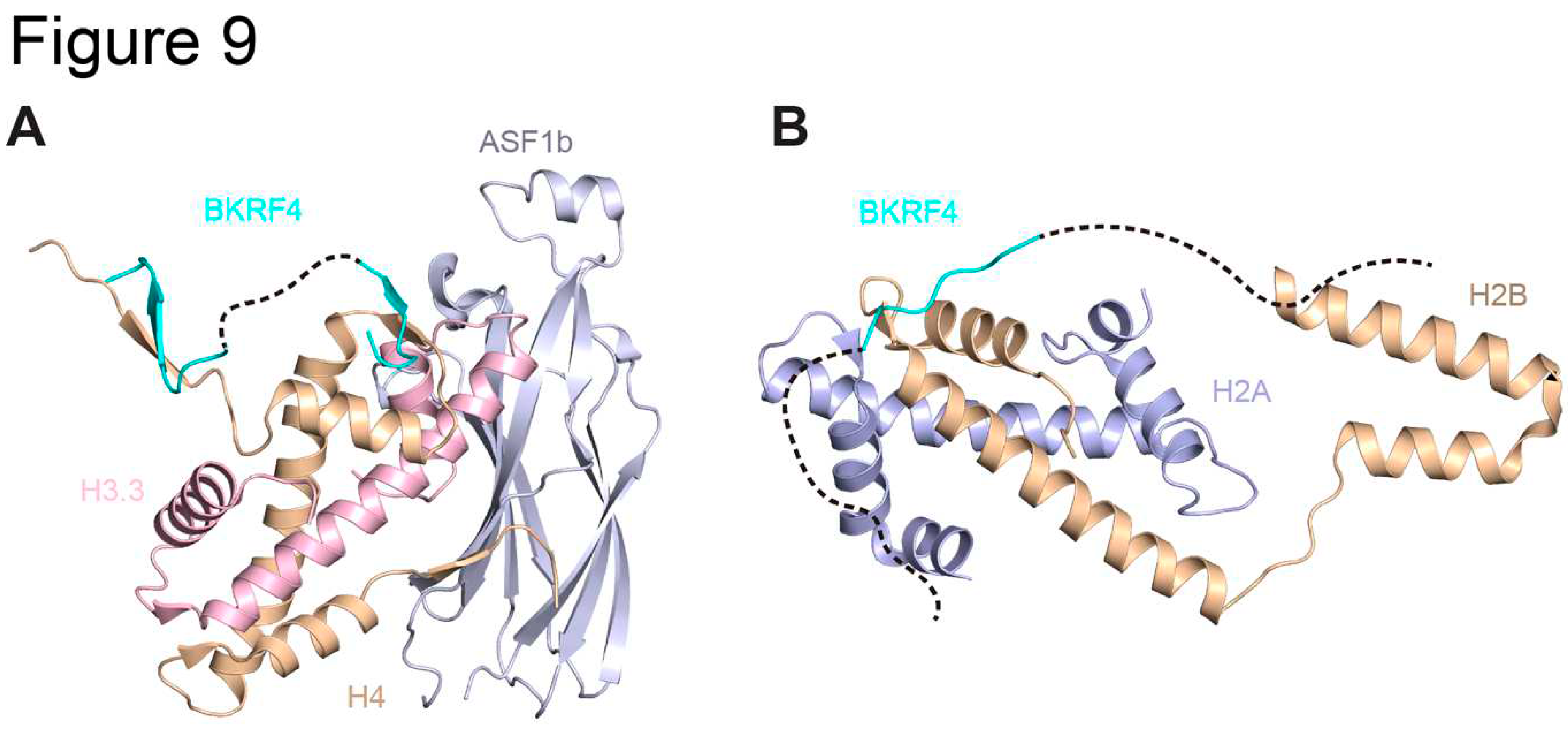

3.4. EBV BKRF4

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Materials & Correspondence:

References

- Murata, T. & Tsurumi, T. Switching of EBV cycles between latent and lytic states. Reviews in Medical Virology (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.1780. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balfour, H. H., Dunmire, S. K. & Hogquist, K. A. Infectious mononucleosis. Clinical and Translational Immunology (2015). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupp, B. G., Fuchs, W., Granzow, H., Nixdorf, R. & Mettenleiter, T. C. Pseudorabies Virus UL36 Tegument Protein Physically Interacts with the UL37 Protein. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3065–3071.

- Whitehurst, C. B. , Vaziri, C., Shackelford, J. & Pagano, J. S. Epstein-Barr Virus BPLF1 Deubiquitinates PCNA and Attenuates Polymerase Recruitment to DNA Damage Sites. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8097–8106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, H. , Su, C., Pearson, A., Mody, C. H. & Zheng, C. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL24 Abrogates the DNA Sensing Signal Pathway by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation. J. Virol. 91, (2017).

- Connolly, S. A. , Jardetzky, T. S. & Longnecker, R. The structural basis of herpesvirus entry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X. & Hong Zhou, Z. Structure of the herpes simplex virus 1 capsid with associated tegument protein complexes. Science 2018, 80, 360. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. , Jih, J., Jiang, J. & Zhou, Z. H. Atomic structure of the human cytomegalovirus capsid with its securing tegument layer of pp150. Science 2017, 80, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. et al. CryoEM structure of the tegumented capsid of Epstein-Barr virus. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 873–884. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xinghong Dai, Danyang Gong, Hanyoung Lim, Jonathan Jih, Ting-Ting Wu, R. & Zhou, S. and Z. H. Structure and mutagenesis reveal essential capsid protein interactions for KSHV replication. Science (80-. ). 2018, 553, 521–525. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-T. , Jih, J., Dai, X., Bi, G.-Q. & Zhou, Z. H. Cryo-EM structures of herpes simplex virus type 1 portal vertex and packaged genome. Nature 2019, 570, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- He, H. P. et al. Structure of Epstein-Barr virus tegument protein complex BBRF2-BSRF1 reveals its potential role in viral envelopment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Al Masud, H. M. A. et al. Epstein-barr virus BBRF2 is required for maximum infectivity. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlqvist, J. & Mocarski, E. Cytomegalovirus UL103 Controls Virion and Dense Body Egress. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 5125–5135. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, R. J. & Fetters, R. The Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL51 Protein Interacts with the UL7 Protein and Plays a Role in Its Recruitment into the Virion. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 3112–3122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gruffat, H. , Kadjouf, F., Mariamé, B. & Manet, E. The Epstein-Barr Virus BcRF1 Gene Product Is a TBP-Like Protein with an Essential Role in Late Gene Expression. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6023–6032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarfo, A. et al. The UL21 Tegument Protein of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Is Differentially Required for the Syncytial Phenotype. J. Virol. 91, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Preston, V. G. , Murray, J., Preston, C. M., McDougall, I. M. & Stow, N. D. The UL25 Gene Product of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Is Involved in Uncoating of the Viral Genome. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 6654–6666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Köppen-Rung, P. , Dittmer, A. & Bogner, E. Intracellular Distribution of Capsid-Associated pUL77 of Human Cytomegalovirus and Interactions with Packaging Proteins and pUL93. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5876–5885. [Google Scholar]

- Pasdeloup, D. , McElwee, M., Beilstein, F., Labetoulle, M. & Rixon, F. J. Herpesvirus Tegument Protein pUL37 Interacts with Dystonin/BPAG1 To Promote Capsid Transport on Microtubules during Egress. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2857–2867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jambunathan, N. et al. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Protein UL37 Interacts with Viral Glycoprotein gK and Membrane Protein UL20 and Functions in Cytoplasmic Virion Envelopment. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5927–5935. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. T. , Strugatsky, D., Liu, W. & Zhou, Z. H. Structure of human cytomegalovirus virion reveals host tRNA binding to capsid-associated tegument protein pp150. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, B. G. et al. Structure of herpes simplex virus pUL7:pUL51, a conserved complex required for efficient herpesvirus assembly. bioRxiv 810663 (2019).

- Womack, A. & Shenk, T. Human Cytomegalovirus Tegument Protein pUL71 Is Required for Efficient Virion Egress. MBio 1, (2010).

- Tanaka, M., Sata, T. & Kawaguchi, Y. The product of the Herpes simplex virus 1 UL7 gene interacts with a mitochondrial protein, adenine nucleotide translocator 2. Virol. J. 2008, 5.

- Xu, X. et al. The mutated tegument protein UL7 attenuates the virulence of herpes simplex virus 1 by reducing the modulation of α-4 gene transcription. Virol. J. 2016, 13.

- Nozawa, N. et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 UL51 Protein Is Involved in Maturation and Egress of Virus Particles. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 6947–6956. [CrossRef]

- Albecka, A. et al. Dual Function of the pUL7-pUL51 Tegument Protein Complex in Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection. J. Virol. 2017, 91.

- Fuchs, W. et al. The UL7 Gene of Pseudorabies Virus Encodes a Nonessential Structural Protein Which Is Involved in Virion Formation and Egress. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 11291–11299. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roller, R. J. , Haugo, A. C., Yang, K. & Baines, J. D. The Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL51 Gene Product Has Cell Type-Specific Functions in Cell-to-Cell Spread. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4058–4068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yanagi, Y. et al. Initial characterization of the Epstein–Barr virus BSRF1 gene product. Viruses 2019, 11.

- Ortiz, D. A. , Glassbrook, J. E. & Pellett, P. E. Protein-Protein Interactions Suggest Novel Activities of Human Cytomegalovirus Tegument Protein pUL103. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 7798–7810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oda, S. , Arii, J., Koyanagi, N., Kato, A. & Kawaguchi, Y. The Interaction between Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Tegument Proteins UL51 and UL14 and Its Role in Virion Morphogenesis. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8754–8767. [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, N. et al. Subcellular Localization of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 UL51 Protein and Role of Palmitoylation in Golgi Apparatus Targeting. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 3204–3216. [CrossRef]

- He, H. P. et al. Structure of Epstein-Barr virus tegument protein complex BBRF2-BSRF1 reveals its potential role in viral envelopment. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5405. [CrossRef]

- Meissner, C. S. , Suffner, S., Schauflinger, M., von Einem, J. & Bogner, E. A Leucine Zipper Motif of a Tegument Protein Triggers Final Envelopment of Human Cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 3370–3382. [Google Scholar]

- Klupp, B. G., Böttcher, S., Granzow, H., Kopp, M. & Mettenleiter, T. C. Complex Formation between the UL16 and UL21 Tegument Proteins of Pseudorabies Virus. J. Virol. (2005). [CrossRef]

- Harper, A. L. et al. Interaction Domains of the UL16 and UL21 Tegument Proteins of Herpes Simplex Virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2963–2971. [CrossRef]

- Le Sage, V. et al. The Herpes Simplex Virus 2 UL21 Protein Is Essential for Virus Propagation. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5904–5915. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J. , Chadha, P., Starkey, J. L. & Wills, J. W. Function of glycoprotein E of herpes simplex virus requires coordinated assembly of three tegument proteins on its cytoplasmic tail. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 19798–19803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aubry, V. et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Late Gene Transcription Depends on the Assembly of a Virus-Specific Preinitiation Complex. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 12825–12838. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Walsh, A., Lam, T. T., Delecluse, H.-J. & El-Guindy, A. A single phosphoacceptor residue in BGLF3 is essential for transcription of Epstein-Barr virus late genes. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007980. [Google Scholar]

- Gruffat, H. , Kadjouf, F., Mariamé, B. & Manet, E. The Epstein-Barr Virus BcRF1 Gene Product Is a TBP-Like Protein with an Essential Role in Late Gene Expression. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 6023–6032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, M. et al. Cytomegalovirus late transcription factor target sequence diversity orchestrates viral early to late transcription. PLoS Pathogens 2021, 17.

- Metrick, C. M. , Chadha, P. & Heldwein, E. E. The Unusual Fold of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL21, a Multifunctional Tegument Protein. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2979–2984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Curanović, D. , Lyman, M. G., Bou-Abboud, C., Card, J. P. & Enquist, L. W. Repair of the U L 21 Locus in Pseudorabies Virus Bartha Enhances the Kinetics of Retrograde, Transneuronal Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klupp, B. G. , Lomniczi, B., Visser, N., Fuchs, W. & Mettenleiter, T. C. Viral Pathogens and ImmunityMutations Affecting the UL21 Gene Contribute to Avirulence of Pseudorabies Virus Vaccine Strain Bartha. Virology 1995, 212, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Wind, N. , Wagenaar, F., Pol, J., Kimman, T. & Berns, A. The pseudorabies virus homology of the herpes simplex virus UL21 gene product is a capsid protein which is involved in capsid maturation. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 7096–7103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, L. Duck enteritis virus UL21 is a late gene encoding a protein that interacts with pUL16. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupp, B. G. , Böttcher, S., Granzow, H., Kopp, M. & Mettenleiter, T. C. Complex Formation between the UL16 and UL21 Tegument Proteins of Pseudorabies Virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar]

- de Wind, N. , Wagenaar, F., Pol, J., Kimman, T. & Berns, A. The pseudorabies virus homology of the herpes simplex virus UL21 gene product is a capsid protein which is involved in capsid maturation. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 7096–7103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takakuwa, H. et al. Herpes simplex virus encodes a virion-associated protein which promotes long cellular processes in over-expressing cells. Genes to Cells 2001, 6, 955–966. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metrick, C. M. & Heldwein, E. E. Novel Structure and Unexpected RNA-Binding Ability of the C-Terminal Domain of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Tegument Protein UL21. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5759–5769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klupp, B. G. , Granzow, H., Keil, G. M. & Mettenleiter, T. C. The Capsid-Associated UL25 Protein of the Alphaherpesvirus Pseudorabies Virus Is Nonessential for Cleavage and Encapsidation of Genomic DNA but Is Required for Nuclear Egress of Capsids. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6235–6246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowman, B. R. et al. Structural Characterization of the UL25 DNA-Packaging Protein from Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 2309–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurlow, J. K. , Murphy, M., Stow, N. D. & Preston, V. G. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 DNA-Packaging Protein UL17 Is Required for Efficient Binding of UL25 to Capsids. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 2118–2126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ali, M. A. , Forghani, B. & Cantin, E. M. Characterization of an essential HSV-1 protein encoded by the UL25 gene reported to be involved in virus penetration and capsid assembly. Virology 1996, 216, 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X. , Gong, D., Wu, T.-T., Sun, R. & Zhou, Z. H. Organization of Capsid-Associated Tegument Components in Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 12694–12702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grzesik, P. et al. Incorporation of the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus capsid vertex-specific component (CVSC) into self-assembled capsids. Virus Res. 2017, 236, 9–13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-T. , Jih, J., Dai, X., Bi, G.-Q. & Zhou, Z. H. Cryo-EM structures of herpes simplex virus type 1 portal vertex and packaged genome. Nature 2019, 570, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naniima, P. et al. Assembly of infectious Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus progeny requires formation of a pORF19 pentamer. PLoS Biology vol. 19 (2021).

- Liu, W. et al. Structures of capsid and capsid-associated tegument complex inside the Epstein–Barr virus. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1285–1298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heming, J. D., Conway, J. F. & Homa, F. L. Herpesvirus Capsid Assembly and DNA Packaging. in Microorganisms vol. 7 119–142 (2017).

- Draganova, E. B. , Zhang, J., Zhou, Z. H. & Heldwein, E. E. Structural basis for capsid recruitment and coat formation during HSV-1 nuclear egress. Elife 2020, 9, 7073–7082. [Google Scholar]

- McNab, A. R. et al. The Product of the Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 UL25 Gene Is Required for Encapsidation but Not for Cleavage of Replicated Viral DNA. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1060–1070. [CrossRef]

- Desai, P. J. A Null Mutation in the UL36 Gene of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Results in Accumulation of Unenveloped DNA-Filled Capsids in the Cytoplasm of Infected Cells. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 11608–11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. et al. A Viral Deamidase Targets the Helicase Domain of RIG-I to Block RNA-Induced Activation. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. et al. Species-Specific Deamidation of cGAS by Herpes Simplex Virus UL37 Protein Facilitates Viral Replication. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, H. M. A. Al et al. The BOLF1 gene is necessary for effective Epstein–Barr viral infectivity. Virology 2019, 531, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J. P. & Monie, T. P. Computational analysis predicts the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus tegument protein ORF63 to be alpha helical. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2012, 80, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts, J. D. , Klabis, J., Richards, A. L., Smith, G. A. & Heldwein, E. E. Crystal Structure of the Herpesvirus Inner Tegument Protein UL37 Supports Its Essential Role in Control of Viral Trafficking. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5462–5473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitehurst, C. B. et al. The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Deubiquitinating Enzyme BPLF1 Reduces EBV Ribonucleotide Reductase Activity. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 4345–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A. , Yamashita, Y., Kanda, T., Murata, T. & Tsurumi, T. Epstein-Barr virus genome packaging factors accumulate in BMRF1-cores within viral replication compartments. PLoS One 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, W. Y. et al. Suppression of cGAS- and RIG-I-mediated innate immune signaling by Epstein-Barr virus deubiquitinase BPLF1. PLoS Pathogens vol. 19 (2023).

- Madrigano, J. & Adam Moser and Darrin M. York, K. R. Labeling and localization of the herpes simplex virus capsid protein UL25 and its interaction with the two triplexes closest to the penton. J Mol Biol 2008, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Trus, B. L. et al. Allosteric Signaling and a Nuclear Exit Strategy: Binding of UL25/UL17 Heterodimers to DNA-Filled HSV-1 Capsids. Mol. Cell 2007, 26, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toropova, K. , Huffman, J. B., Homa, F. L. & Conway, J. F. The Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL17 Protein Is the Second Constituent of the Capsid Vertex-Specific Component Required for DNA Packaging and Retention. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 7513–7522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newcomb, W. W. & Brown, J. C. Structure and Capsid Association of the Herpesvirus Large Tegument Protein UL36. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9408–9414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sam, M. D. , Evans, B. T., Coen, D. M. & Hogle, J. M. Biochemical, Biophysical, and Mutational Analyses of Subunit Interactions of the Human Cytomegalovirus Nuclear Egress Complex. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2996–3006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leigh, K. E. et al. Structure of a herpesvirus nuclear egress complex subunit reveals an interaction groove that is essential for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 9010–9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M. , Kamil, J. P., Coughlin, M., Reim, N. I. & Coen, D. M. Human Cytomegalovirus UL50 and UL53 Recruit Viral Protein Kinase UL97, Not Protein Kinase C, for Disruption of Nuclear Lamina and Nuclear Egress in Infected Cells. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J. , Auerochs, S., Sticht, H. & Marschall, M. Cytomegaloviral proteins that associate with the nuclear lamina: components of a postulated nuclear egress complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, M. et al. Dominant Negative Mutants of the Murine Cytomegalovirus M53 Gene Block Nuclear Egress and Inhibit Capsid Maturation. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 9035–9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, K. E. et al. Structure of a herpesvirus nuclear egress complex subunit reveals an interaction groove that is essential for viral replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 9010–9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, M. F. et al. Unexpected features and mechanism of heterodimer formation of a herpesvirus nuclear egress complex. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2937–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, D. , Damaschke, J., Mautner, J. & Behrends, U. The Epstein-Barr Virus Major Tegument Protein BNRF1 Is a Common Target of Cytotoxic CD4 + T Cells. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. I. Epstein–Barr Virus Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, P. M. Chromatin Structure of Epstein–Barr Virus Latent Episomes. in Cancers vol. 10 71–102 (2015).

- Schreiner, S. & Wodrich, H. Virion Factors That Target Daxx To Overcome Intrinsic Immunity. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10412–10422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, H. et al. Structural basis underlying viral hijacking of a histone chaperone complex. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K. , Messick, T. E. & Lieberman, P. M. Disruption of host antiviral resistances by gammaherpesvirus tegument proteins with homology to the FGARAT purine biosynthesis enzyme. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 14, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A. Z. et al. A Conserved Mechanism of APOBEC3 Relocalization by Herpesviral Ribonucleotide Reductase Large Subunits. J. Virol. 93, (2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A. Z. et al. Epstein–Barr virus BORF2 inhibits cellular APOBEC3B to preserve viral genome integrity. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 4, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, B. L. et al. Ribonucleotide Reductases: Structure, Chemistry, and Metabolism Suggest New Therapeutic Targets. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban, N. M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the EBV ribonucleotide reductase BORF2 and mechanism of APOBEC3B inhibition. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Tegument Protein BKRF4 is a Histone Chaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. et al. Epstein-Barr virus protein BKRF4 restricts nucleosome assembly to suppress host antiviral responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022, 119, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).