Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Measurement of Air Pollutants

2.4. Algal Identification

2.4.1. Merging of Paired-End Reads and Quality Control

2.4.2. Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) Denoising and Species Annotation

2.5. Algal Community Structure

2.6. Relationship Between Algal Diversity and Abundance and the Air Pollutants

3. Results

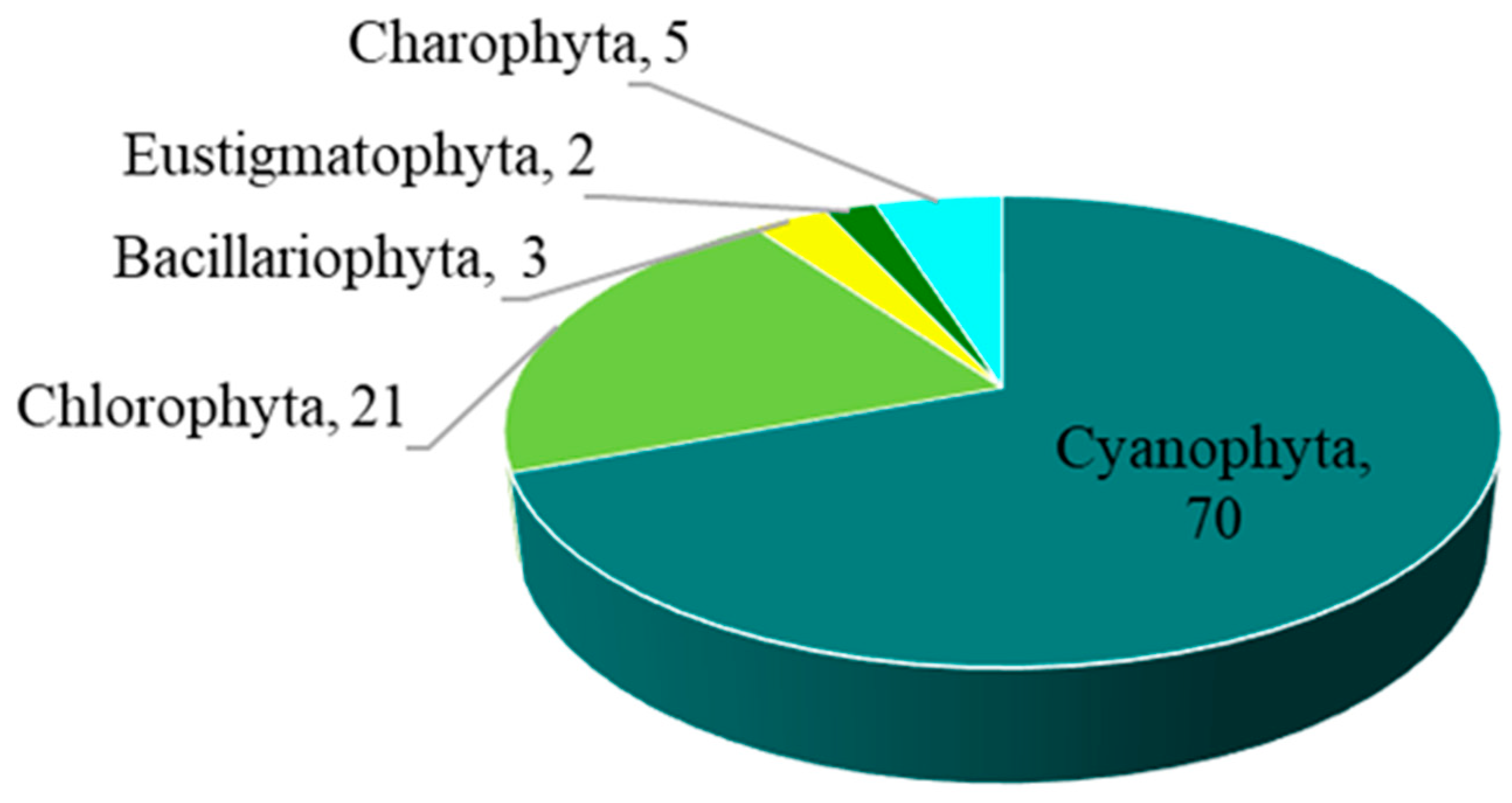

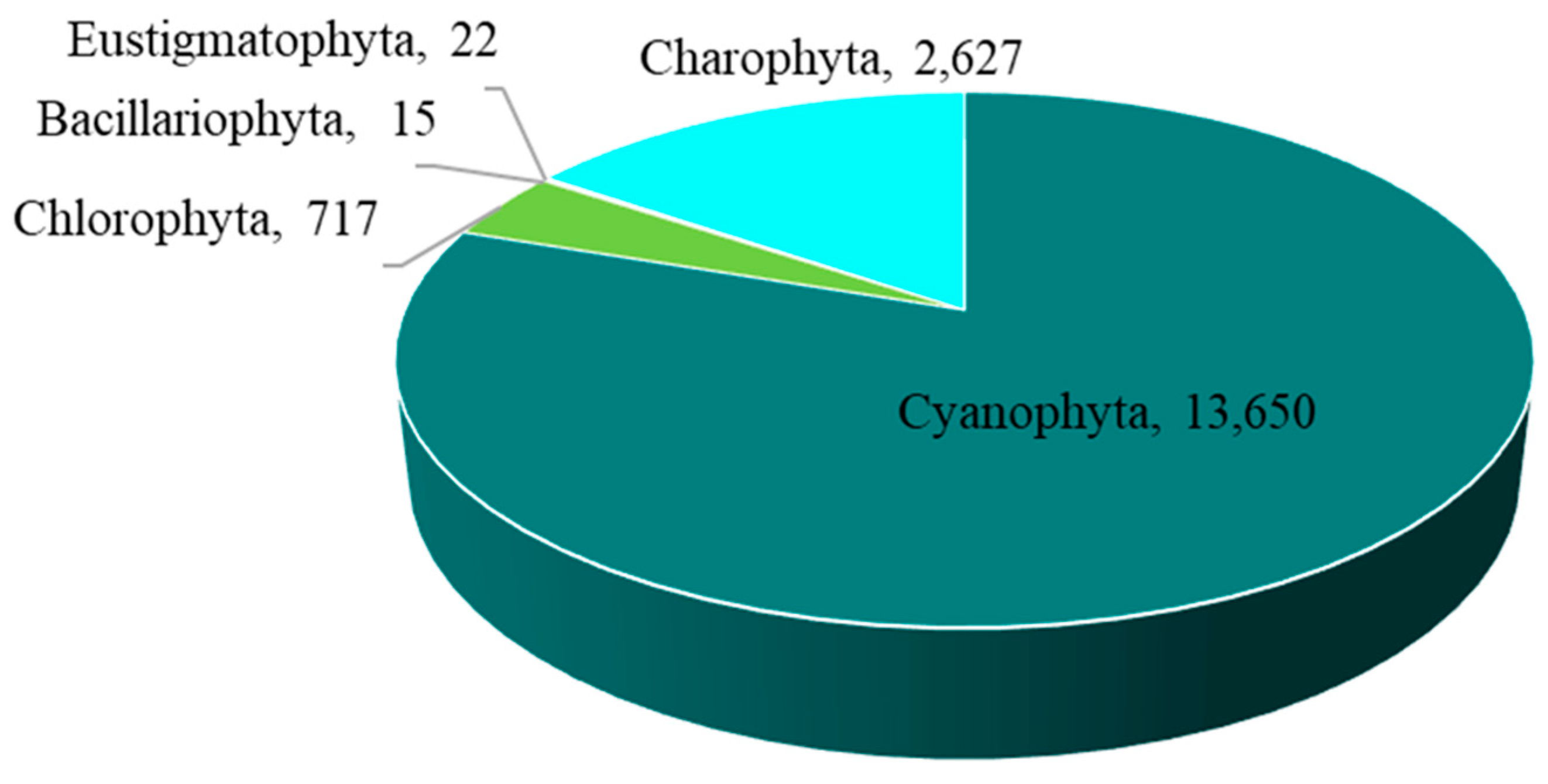

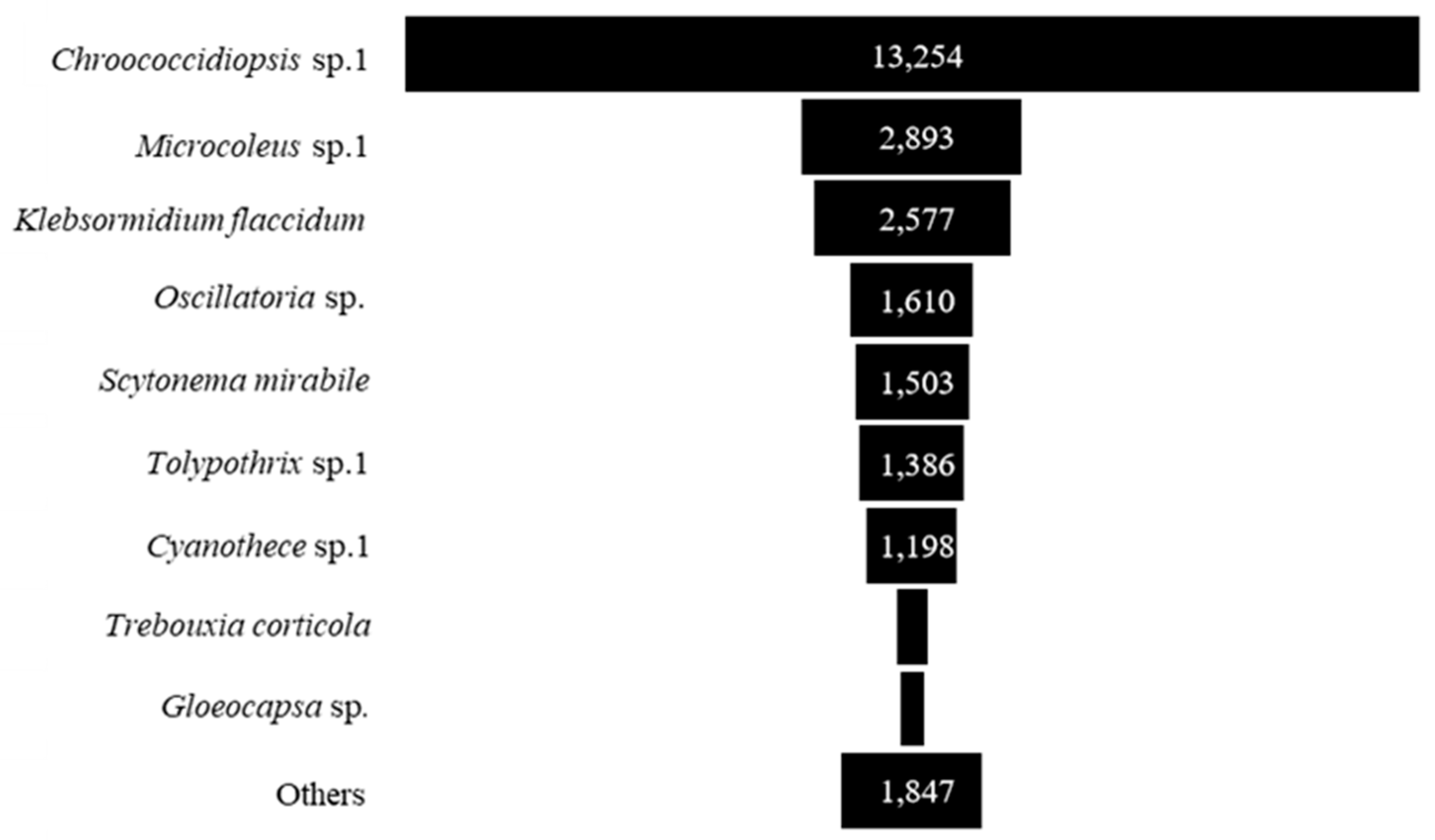

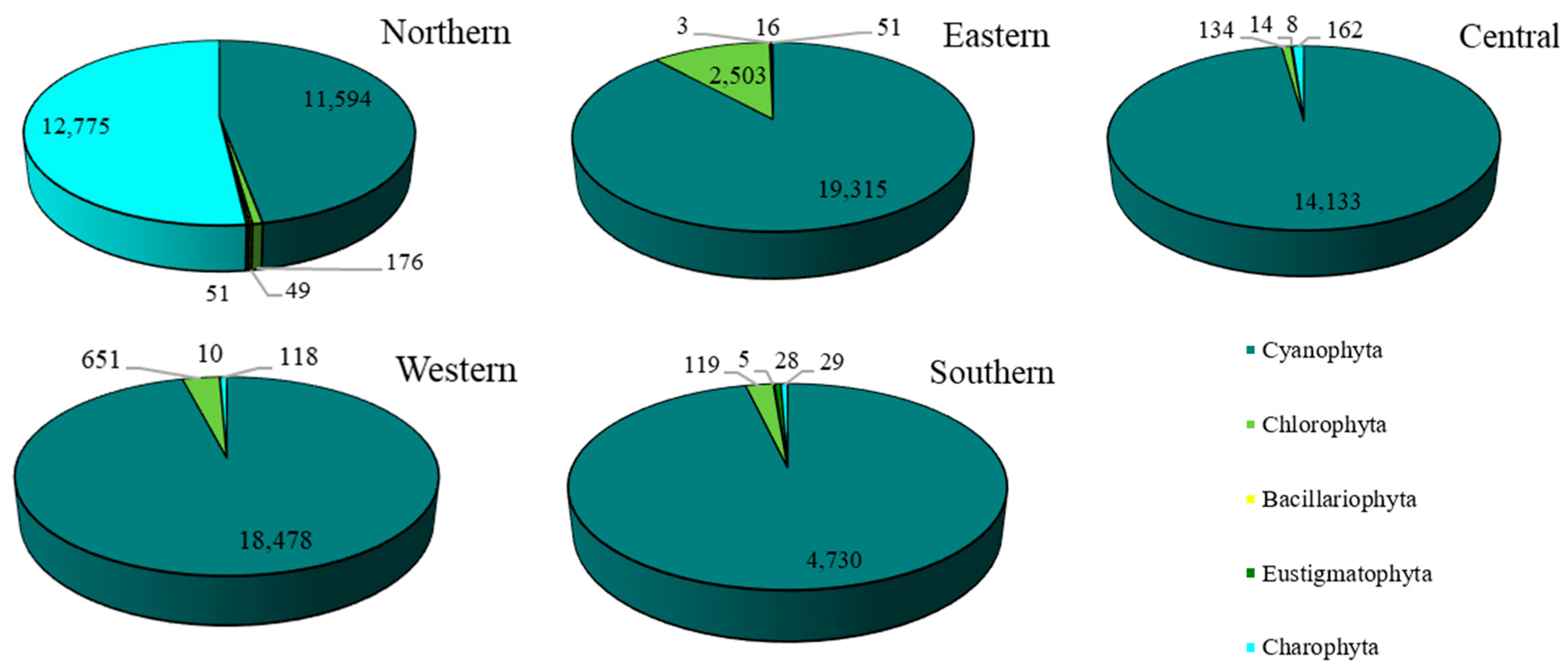

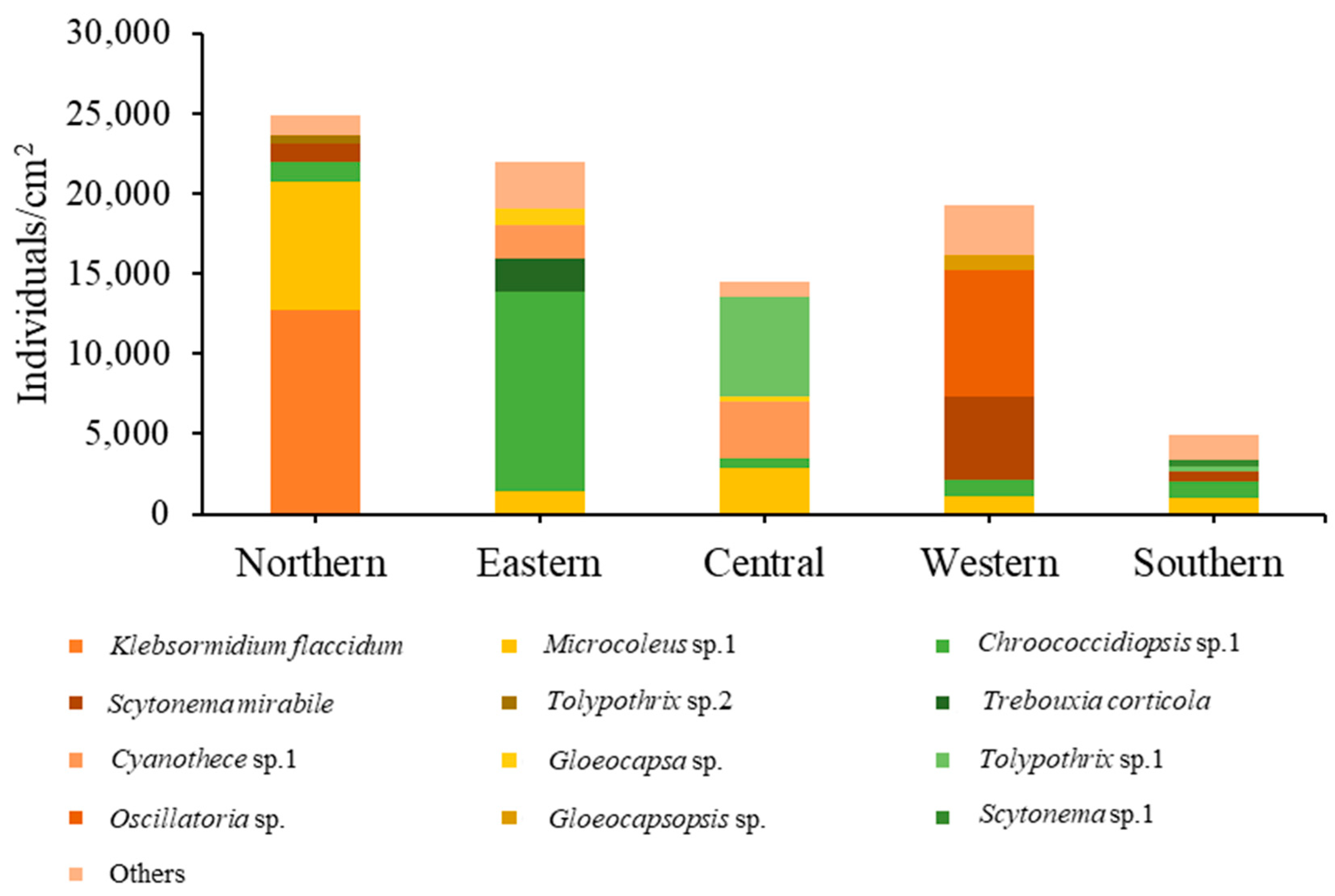

3.1. Diversity and Abundance of Algae

3.2. Types of Air Pollutants

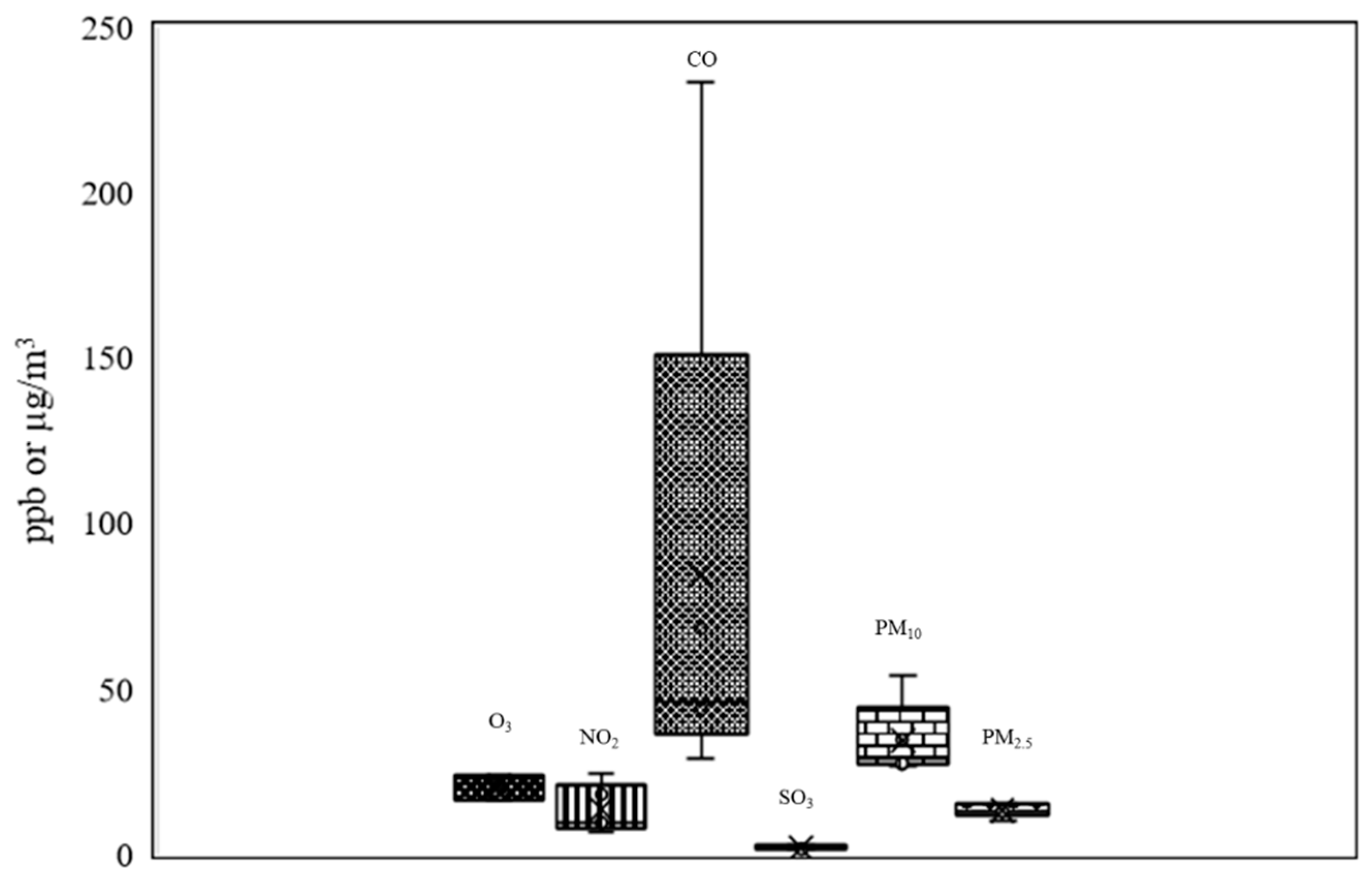

3.3. Index Values for Algal Communities

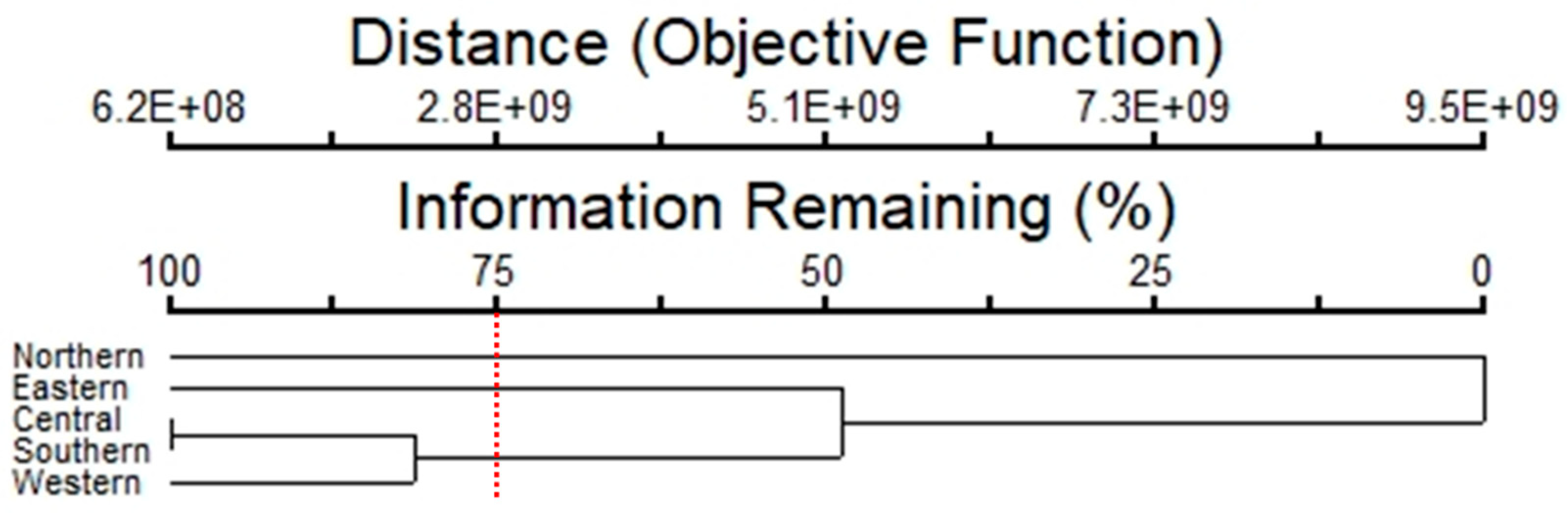

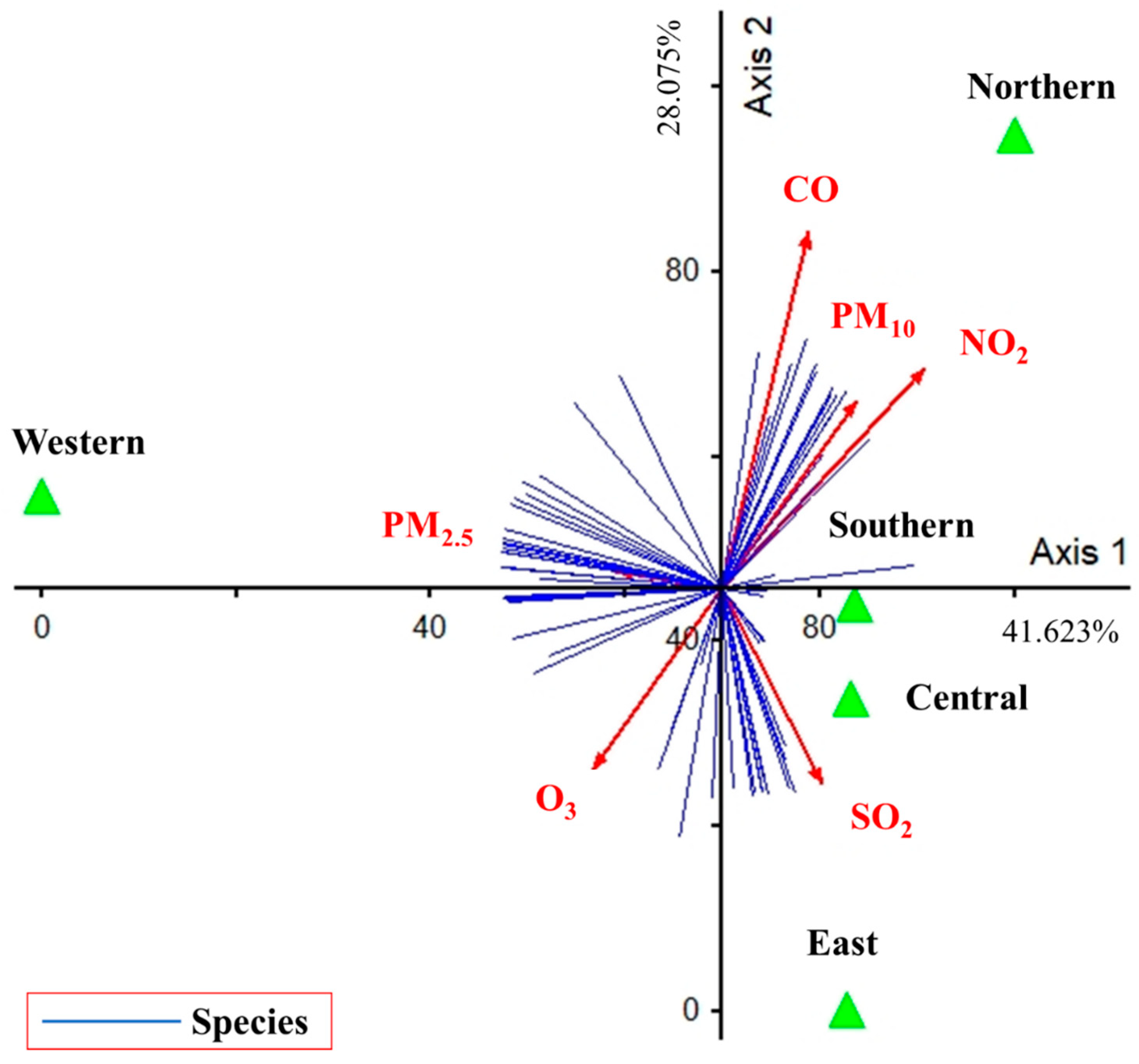

3.4. Relationship between Diversity of Species and Air Pollutants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Northern Site | Eastern Site | Central Site | Western Site | Southern Site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillatoria sp. | 163 | 9 | 22 | 7911 | 102 |

| Scytonema mirabile | 1106 | 265 | 255 | 5232 | 656 |

| Microcoleus sp. 1 | 7941 | 1454 | 2922 | 1144 | 1004 |

| Chroococcidiopsis sp. 1 | 1302 | 12391 | 602 | 962 | 1013 |

| Gloeocapsopsis sp. | 7 | 28 | 8 | 900 | 19 |

| Stanieria sp. | 16 | 7 | 18 | 793 | 14 |

| Tolypothrix sp. 1 | 61 | 140 | 6186 | 242 | 301 |

| Microchaete diplosiphon | 0 | 0 | 0 | 199 | 3 |

| Scytonema sp. 1 | 0 | 164 | 22 | 160 | 444 |

| Tolypothrix sp. 2 | 506 | 244 | 140 | 152 | 165 |

| Calothrix sp. 3 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 131 | 1 |

| Pleurocapsa minor | 90 | 22 | 20 | 122 | 32 |

| Cyanothece sp. 1 | 4 | 2057 | 3543 | 92 | 291 |

| Hyella patelloides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 2 |

| Calothrix sp. 2 | 64 | 6 | 18 | 40 | 156 |

| Nostoc piscinale | 0 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 0 |

| Chondrocystis sp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 |

| Chroococcidiopsis thermalis | 15 | 98 | 10 | 33 | 52 |

| Brasilonema sp. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 2 |

| Calothrix sp. 1 | 0 | 396 | 6 | 17 | 6 |

| Cyanothece sp. 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 5 |

| Gloeocapsa sp. | 164 | 1118 | 282 | 13 | 95 |

| Microcoleus sp. 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| Lusitaniella coriacea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 198 |

| Cyanothece sp. 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Nostoc linckia | 1 | 76 | 1 | 11 | 0 |

| Calothrix brevissima | 0 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 0 |

| Cyanothece sp. 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Nostoc sp. 1 | 61 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| Scytonema hofmannii | 33 | 0 | 11 | 8 | 12 |

| Oscillatoria nigro-viridis | 28 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Nostoc sp. 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Cylindrospermum stagnale | 0 | 551 | 13 | 6 | 0 |

| Scytonema crispum | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 17 |

| Gloeobacter kilaueensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Oculatella neakameniensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Scytonema sp. 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Lyngbya aestuarii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Calothrix sp. 4 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Synechococcus lividus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Oscillatoria acuminata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Trichormus azollae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Nodosilinea sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Thermosynechococcus sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Crinalium epipsammum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sphaerospermopsis kisseleviana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fischerella muscicola | 0 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pleurocapsa sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dolichospermum compactum | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| Stanieria cyanosphaera | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Cyanothece sp. 2 | 40 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Nostoc punctiforme | 1 | 211 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Cylindrospermum muscicola | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Calothrix sp. 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anabaena sp. 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 1 |

| Calothrix sp. 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Jaaginema litorale | 9 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Cylindrospermum sp. | 75 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyanothece sp. 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Camptylonemopsis sp. | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gloeocapsopsis crepidinum | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chroococcidiopsis sp. 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cyanobium gracile | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nostoc carneum | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phormidium tinctorium | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Synechococcus sp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diadesmis sp. | 49 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Nitzschia sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Cylindrotheca closterium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Watanabea reniformis | 21 | 97 | 17 | 16 | 53 |

| Ignatius tetrasporus | 37 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 27 |

| Nannochloris normandinae | 17 | 135 | 36 | 47 | 13 |

| Scenedesmus | 4 | 104 | 24 | 236 | 13 |

| Trebouxia corticola | 5 | 2090 | 38 | 6 | 5 |

| Trebouxia australis | 0 | 9 | 0 | 14 | 2 |

| Chloromonas perforata | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Pyramimonas disomata | 3 | 13 | 0 | 232 | 2 |

| Xylochloris irregularis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Lobosphaera incisa | 3 | 13 | 0 | 18 | 1 |

| Edaphochlorella mirabilis | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Dilabifilum sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 0 |

| Heterochlorella | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| Friedmannia sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Symbiochloris reticulata | 12 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Acutodesmus sp. | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Parachlorella kessleri | 46 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Trebouxia decolorans | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Symbiochloris irregularis | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stichococcus sp. | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlamydomonas zebra | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Monodopsis sp. 2 | 22 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 28 |

| Nannochloropsis oculata | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlorokybus atmophyticus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 2 | 12 | 3 | 35 | 11 | 6 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 1 | 0 | 19 | 13 | 83 | 1 |

| Klebsormidium flaccidum | 12763 | 10 | 91 | 22 | 0 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 3 | 0 | 20 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| CO | NO2 | O3 | PM2.5 | PM10 | SO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillatoria sp. | ‒0.236 | –0.509 | 0.400 | 0.498 | –0.358 | –0.547 |

| Scytonema mirabile | ‒0.097 | –0.378 | 0.274 | 0.549 | –0.239 | –0.580 |

| Microcoleus sp. 1 | 0.939* | 0.730 | –0.510 | –0.307 | 0.916* | –0.354 |

| Chroococcidiopsis sp. 1 | ‒0.327 | –0.276 | 0.294 | –0.026 | 0.046 | 0.784 |

| Gloeocapsopsis sp. | ‒0.264 | –0.532 | 0.420 | 0.500 | –0.377 | –0.524 |

| Stanieria sp. | ‒0.247 | –0.521 | 0.413 | 0.487 | –0.370 | –0.551 |

| Tolypothrix sp. 1 | ‒0.287 | –0.334 | 0.475 | –0.857 | –0.368 | –0.369 |

| Microchaete diplosiphon | ‒0.254 | –0.521 | 0.409 | 0.499 | –0.375 | –0.538 |

| Scytonema sp. 1 | ‒0.386 | 0.034 | –0.317 | 0.678 | –0.460 | 0.562 |

| Tolypothrix sp. 2 | 0.925* | 0.773 | –0.610 | –0.022 | 0.999** | –0.048 |

| Calothrix sp. 3 | 0.017 | –0.312 | 0.244 | 0.498 | –0.114 | –0.633 |

| Pleurocapsa minor | 0.399 | 0.061 | –0.081 | 0.505 | 0.258 | –0.648 |

| Cyanothece sp. 1 | ‒0.499 | –0.495 | 0.638 | –0.866 | –0.371 | 0.082 |

| Hyella patelloides | –0.255 | –0.520 | 0.406 | 0.504 | –0.377 | –0.536 |

| Calothrix sp. 2 | 0.222 | 0.583 | –0.781 | 0.572 | 0.000 | 0.209 |

| Nostoc piscinale | –0.277 | –0.555 | 0.450 | 0.469 | –0.387 | –0.536 |

| Chondrocystis sp. | –0.194 | –0.484 | 0.386 | 0.486 | –0.317 | –0.573 |

| Chroococcidiopsis thermalis | –0.470 | –0.263 | 0.145 | 0.329 | –0.175 | 0.880* |

| Brasilonema sp. | –0.320 | –0.553 | 0.419 | 0.557 | –0.413 | –0.432 |

| Calothrix sp. 1 | –0.388 | –0.340 | 0.353 | –0.041 | –0.017 | 0.734 |

| Cyanothece sp. 3 | 0.079 | –0.110 | –0.036 | 0.785 | –0.051 | –0.384 |

| Gloeocapsa sp. | –0.332 | –0.279 | 0.347 | –0.262 | 0.042 | 0.713 |

| Microcoleus sp. 3 | –0.262 | –0.555 | 0.459 | 0.502 | –0.305 | –0.427 |

| Lusitaniella coriacea | –0.122 | 0.324 | –0.561 | 0.527 | –0.288 | 0.414 |

| Cyanothece sp. 4 | –0.364 | –0.631 | 0.524 | 0.491 | –0.380 | –0.347 |

| Nostoc linckia | –0.402 | –0.390 | 0.398 | 0.004 | –0.035 | 0.682 |

| Calothrix brevissima | –0.445 | –0.750 | 0.691 | 0.205 | –0.522 | –0.564 |

| Cyanothece sp. 5 | –0.056 | –0.374 | 0.297 | 0.495 | –0.183 | –0.615 |

| Nostoc sp. 1 | 0.975* | 0.752 | –0.591 | –0.001 | 0.943* | –0.342 |

| Scytonema hofmannii | 0.964** | 0.841 | –0.709 | –0.059 | 0.805 | –0.444 |

| Oscillatoria nigro-viridis | 0.949* | 0.689 | –0.547 | 0.079 | 0.893* | –0.427 |

| Nostoc sp. 2 | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Cylindrospermum stagnale | –0.376 | –0.327 | 0.349 | –0.070 | –0.003 | 0.734 |

| Scytonema crispum | –0.329 | 0.044 | –0.259 | 0.296 | –0.577 | 0.111 |

| Gloeobacter kilaueensis | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes | –0.097 | –0.226 | 0.044 | 0.737 | –0.300 | –0.447 |

| Oculatella neakameniensis | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 2 | –0.287 | –0.451 | 0.280 | 0.634 | –0.450 | –0.446 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 3 | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Scytonema sp. 2 | –0.486 | –0.563 | 0.530 | 0.178 | –0.167 | 0.491 |

| Lyngbya aestuarii | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Calothrix sp. 4 | –0.585 | –0.790 | 0.917* | –0.705 | –0.503 | 0.281 |

| Synechococcus lividus | –0.226 | 0.103 | –0.384 | 0.728 | –0.441 | 0.185 |

| Oscillatoria acuminata | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Trichormus azollae | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Nodosilinea sp. | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Thermosynechococcus sp. | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Crinalium epipsammum | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Sphaerospermopsis kisseleviana | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Fischerella muscicola | –0.402 | –0.367 | 0.389 | –0.077 | –0.031 | 0.711 |

| Pleurocapsa sp. | 0.600 | 0.231 | –0.184 | 0.356 | 0.485 | –0.662 |

| Dolichospermum compactum | –0.079 | 0.375 | –0.600 | 0.493 | –0.238 | 0.436 |

| Stanieria cyanosphaera | –0.010 | 0.438 | –0.654 | 0.495 | –0.172 | 0.423 |

| Cyanothece sp. 2 | 0.914* | 0.988** | –0.941** | 0.210 | 0.842 | 0.045 |

| Nostoc punctiforme | –0.377 | –0.293 | 0.299 | –0.031 | –0.009 | 0.783 |

| Cylindrospermum muscicola | –0.106 | 0.350 | –0.578 | 0.491 | –0.263 | 0.440 |

| Calothrix sp. 6 | –0.106 | 0.350 | –0.578 | 0.491 | –0.263 | 0.440 |

| Anabaena sp. 1 | –0.272 | –0.310 | 0.453 | –0.861 | –0.353 | –0.358 |

| Calothrix sp. 5 | –0.265 | –0.321 | 0.472 | –0.873 | –0.339 | –0.372 |

| Jaaginema litorale | 0.875 | 0.668 | –0.430 | –0.456 | 0.818 | –0.442 |

| Cylindrospermum sp. | 0.949* | 0.774 | –0.599 | –0.066 | 0.994** | –0.139 |

| Cyanothece sp. 6 | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Camptylonemopsis sp. | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Gloeocapsopsis crepidinum | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Chroococcidiopsis sp. 2 | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Cyanobium gracile | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Leptolyngbya sp. 1 | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Nostoc carneum | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Phormidium tinctorium | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Synechococcus sp. | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Diadesmis sp. | 0.986** | 0.802 | –0.627 | –0.107 | 0.940* | –0.332 |

| Nitzschia sp. | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Cylindrotheca closterium | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Watanabea reniformis | –0.371 | –0.112 | 0.035 | 0.164 | –0.063 | 0.957* |

| Ignatius tetrasporus | 0.774 | 0.801 | –0.835 | 0.589 | 0.761 | 0.142 |

| Nannochloris normandinae | –0.494 | –0.538 | 0.563 | –0.090 | –0.138 | 0.564 |

| Scenedesmus | –0.461 | –0.713 | 0.611 | 0.437 | –0.429 | –0.252 |

| Trebouxia corticola | –0.370 | –0.319 | 0.340 | –0.069 | 0.003 | 0.739 |

| Trebouxia australis | –0.500 | –0.676 | 0.547 | 0.528 | –0.404 | –0.010 |

| Chloromonas perforata | 0.547 | 0.857 | –0.962** | 0.424 | 0.386 | 0.236 |

| Pyramimonas disomata | –0.263 | –0.537 | 0.428 | 0.500 | –0.364 | –0.511 |

| Xylochloris irregularis | –0.396 | –0.572 | 0.406 | 0.632 | –0.460 | –0.285 |

| Lobosphaera incisa | –0.369 | –0.605 | 0.524 | 0.469 | –0.230 | –0.021 |

| Edaphochlorella mirabilis | –0.758 | –0.735 | 0.700 | –0.073 | –0.462 | 0.542 |

| Dilabifilum sp. | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Heterochlorella | –0.406 | –0.701 | 0.693 | –0.086 | –0.566 | –0.750 |

| Friedmannia sp. | –0.252 | –0.524 | 0.416 | 0.491 | –0.370 | –0.542 |

| Symbiochloris reticulata | 0.762 | 0.584 | –0.415 | –0.038 | 0.944* | 0.106 |

| Acutodesmus sp. | –0.452 | –0.481 | 0.641 | –0.896* | –0.333 | 0.015 |

| Parachlorella kessleri | 0.957* | 0.771 | –0.578 | –0.153 | 0.980** | –0.211 |

| Trebouxia decolorans | –0.364 | –0.312 | 0.331 | –0.055 | 0.008 | 0.743 |

| Symbiochloris irregularis | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Stichococcus sp. | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Chlamydomonas zebra | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Monodopsis sp. 2 | 0.382 | 0.763 | –0.775 | –0.034 | 0.384 | 0.560 |

| Nannochloropsis oculata | 0.986** | 0.807 | –0.641 | –0.055 | 0.964** | –0.268 |

| Chlorokybus atmophyticus | –0.119 | 0.329 | –0.564 | 0.520 | –0.284 | 0.419 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 2 | –0.085 | –0.230 | 0.392 | –0.802 | –0.232 | –0.618 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 1 | –0.405 | –0.689 | 0.597 | 0.381 | –0.459 | –0.461 |

| Klebsormidium flaccidum | 0.986** | 0.806 | –0.638 | –0.060 | 0.963** | –0.272 |

| Klebsormidium sp. 3 | –0.506 | –0.516 | 0.661 | –0.798 | –0.288 | 0.243 |

References

- John, D.M. Phylum Chlorophyta (green algae). In The freshwater algal flora of the British Isles; John, D.M., Whitton, B.A., Brook, A.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 287–612. [Google Scholar]

- López-Bautista, J.M.; Rindi, F.; Casamatta, D. The systematics of subaerial algae. In Algae and cyanobacteria in extreme environments; Seckbach, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2007; pp. 599–617. [Google Scholar]

- Rindi, F. Diversity, distribution and ecology of green algae and cyanobacteria in urban habitats. In Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments; Seckbach, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2007; pp. 619–638. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.; Graham, J.; Wilcox, L. Algae, 2nd ed.; Benjamin Cummings (Pearson): San Francisco, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, B.M.; Lim, M.; Wee, Y.C. Effects of desiccation and illumination of photosynthesis and pigmentation of an edaphic population of Trentepohlia odorata (Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 1992, 28, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüttge, U.; Büdel, B. Resurrection kinetics of photosynthesis in desiccation-tolerant terrestrial green algae (Chlorophyta) on tree bark. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 437–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsten, U.; Friedl, T.; Schumann, R.; Hoyer, K.; Lembcke, S. Mycosporine-like amino acids and phylogenies in green algae: Prasiola and its relatives from the Trebouxiophyceae (Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, U.; Karsten, U.; Lembcke, S.; Schumann, R. The effects of ultraviolet radiation on photosynthetic performance, growth, and sunscreen compounds in aeroterrestrial biofilm algae isolated from building facades. Planta 2007, 225, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsten, U.; Schumann, R.; Mostaert, A.S. Aeroterrestrial algae growing on man-made surfaces: what are the secrets of their ecological success? In Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments; Seckbach, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 583–597. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Li, S.; Hu, Z.; Liu, G. Molecular characterization of eukaryotic algal communities in the tropical phyllosphere based on real-time sequencing of the 18S rDNA gene. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, H.; Goltsova, N.; Seppälä, H.S.; Kouki, J.; Lamppu, J.; Popovichev, B. Ecological condition of forests around the eastern part of the Gulf of Finland. Environ. Pollut. 1996, 91, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmor, L.; Degtjarenko, P. Trentepohlia umbrina on Scots pine as bioindicator of alkaline dust pollution. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razli, S.A.; Azlam, A.; Ismail, A.; Murnira, O.; Ahmad, M.A.A.; Hafizah, B.N.; Kadaruddin, A.; Talib, L.M. Epiphytic microalgae as biological indicators for carbon monoxide concentrations in different areas of Peninsular Malaysia. Environ. Forensics 2022, 23, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Ocotla, G.; Carrera, J. Aeroalgae: response to some aerobiological questions. Grana 1993, 32, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, H.S.Y.; Crang, F.E. Changes in thallus and algal cell components of two lichen species in response to low-level air pollution at Pacific Northeast Forests. Microsc. Microanal. 2002, 8, 1078–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Wahab, N.A.; Latif, M.T.; Said, M.; Ismail, A.; Zulkifli, A.R.; Alwi, I.; Daud, D.; Sulaiman, F.N. Atmospheric air pollution and roughness of bark as possible factors in increasing density of epiphytic terrestrial algae. Asian J. Applied Sci. 2016, 4, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hemond, H.F.; Fechner-Levy, E.J. Chemical Fate and Transport in The Environment; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.N.; Oanh, N.T. Photochemical smog pollution in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region of Thailand in relation to O3 precursor concentrations and meteorological conditions. Atmospheric Environment 2002, 36, 4211–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. OECD Green Growth Studies: Green Growth in Bangkok, Thailand; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, S.; Shrestha, A. Bangkok, Thailand. In Cities on A Finite Planet: Towards Transformative Responses to Climate Change; Bartlett, S., Satterthwaite, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Klongvessa, P.; Chotpantarat, S. Statistical analysis of rainfall variations in the Bangkok urban area, Thailand. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 4207–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and Chulalongkorn University. Executive Summary 20-Year Development Plan for Bangkok Metropolis; Strategy and Evaluation Department Bangkok Metropolitan Administration and Faculty of Political Sciences, Chulalongkorn University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwela, D.; Zali, O. Urban traffic pollution; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Muttamara, S.; Leong, S.T. Monitoring and assessment of exhaust emission in Bangkok Street air. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2000, 60, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, R. Review of air pollution and health impacts in Malaysia. Environ. Res. 2003, 92, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, N.; Díaz-Gamboa, R.E. Chapter: 4. line transect sampling. In Introduction to Ecological Sampling; Manly, B., Navarro, J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, 2015; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, A.R.; Presting, G.G. Universal primers amplify a 23S rDNA plastid marker in eukaryotic algae and Cyanobacteria. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, A.R.; Chan, Y.L.; Presting, G.G. Application of universally amplifying plastid primers to environmental sampling of a stream periphyton community. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008, 8, 1011–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haendiges, J.; Timme, R.; Ramachandran, P.; Balkey, M. DNA Quantification Using the Qubit Fluorometer. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/dna-quantification-using-the-qubit-fluorometer-81wgbp3x3vpk/v1 5 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, B.J.; Gevers, D.; Earl, A.M. , Feldgarden, M.; Ward, D.V., Giannoukos, G.; Ciulla, D.; Tabbaa, D.; Highlander, S.K.; Sodergren, E.; et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Shao, D.; Zhou, J.; Gu, J.; Qin, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, W. Signatures within esophageal microbiota with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 32, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berney, C.; Ciuprina, A.; Bender, S.; Brodie, J.; Edgcomb, V.; Kim, E.; Rajan, J.; Parfrey, L.W.; Adl, S.; Audic, S.; et al. UniEuk: Time to speak a common language in protistology! J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2017, 64, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCune, B.; Mefford, M.J. PC-ORD Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data. Version 6; MjM Software, Gleneden Beach, Oregon. 2011.

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation; Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McCune, B. Community Structure and Analysis Biology 570/670; Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University: Corvallis, Oregon, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Neustupa, J.; Škaloud, P. Diversity of subaerial algae and cyanobacteria on tree bark in tropical mountain habitats. Biologia 2008, 63, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustupa, J.; Škaloud, P. Diversity of subaerial algae and cyanobacteria growing on bark and wood in the lowland tropical forests of Singapore. Plant Ecol. Evol. 2010, 143, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaloud, P.; Rindi, F.; Boedeker, C.; Leliaert, F. Chlorophyta: Ulvophyceae. In Süßwasserflora von Mitteleuropa – Freshwater Flora of Central Europe 13; Büdel, B., Gärtner, G., Krienitz, L., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–289. [Google Scholar]

- Klimešová, M.; Rindi, F.; Skaloud, P. DNA cloning demonstrates high genetic heterogeneity in populations of the subaerial green alga Trentepohlia (Trentepohliales, Chlorophyta). J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.K.M.N. Subaerial algae of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Bot. 1972, 1, 13–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, K.K.; Tan, K.H.; Wee, Y.C. Growth conditions of Trentepohlia odorata (Chlorophyta, Ulotrichales). Phycologia 1983, 22, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.; Conklin, K.; Fredrick, P.; Sherwood, A. Pyrosequencing and culturing of Hawaiian corticolous biofilms demonstrate high diversity and confirm phylogenetic placement of the green alga Spongiochrysis hawaiiensis in Cladophorales (Ulvophyceae). Phycologia 2018, 57, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nienow, J.A. Ecology of subaerial algae. Nova Hedwigia 1996, 112, 537–552. [Google Scholar]

- Nienow, J.A. Subaerial communities. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Microbiology; Bitton, G., Ed.; Wiley: New York, USA, 2002; pp. 3055–3065. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbushina, A.A. Life on the rocks. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1613–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Rai, A.K.; Singh, S.; Brown, J.R.M. Airborne algae: Their present status and relevance. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustupa, J.; Štifterová, A. Distribution patterns of subaerial corticolous microalgae in two European regions. Plant Ecol. Evol. 2013, 146, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, B.; Beyens, L.; Vincke, S.; Gremmen, N.J.M. Moss inhibiting diatom communities from Heard Island, sub-Antarctic. Polar Biol. 2004, 27, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.C.; Levanets, A.A.; Blanco, S.; Ector, L. Microcostatus schoemanii sp. nov., M. cholnokyi sp. nov. and M. angloensis sp. nov.: three new terrestrial diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) from South Africa. Phycological Res. 2010, 58, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.W. Biodiversity and systematics of subaerial algae from the neotropics and Hawaii. Doctoral Degree, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Billi, D.; Wilmotte, A.; McKay, C.P. Desert strains of Chroococcidiopsis: a platform to investigate genetic diversity in extreme environments and explore survival potential beyond Earth. In EPSC Abstracts; European Planetary Science Congress: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bothe, H. The cyanobacterium Chroococcidiopsis and its potential for life on Mars. J. Astrobiol. Space Sci. Rev. 2019, 2, 398–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hershkovitz, N.; Oren, A.; Cohen, Y. Accumulation of trehalose and sucrose in cyanobacteria exposed to matric water stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, Y.; Ohad, I.; Kaplan, A. Activation of photosynthesis and resistance to photoinhibition in cyanobacteria within biological desert crust. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3070–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, A.; Vincent, W. F. Strategies of adaptation by Antarctic cyanobacteria to ultraviolet radiation. Eur. J. Phycol. 1997, 32, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, L.; da Rocha, U.N.; Klitgord, N.; Luning, E.G.; Fortney, J.; Axen, S.D.; Shih, P.M.; Bouskill, N.J.; Bowen, B.P.; et al. Dynamic cyanobacterial response to hydration and dehydration in a desert biological soil crust. ISME 2013, 7, 2178–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, G.M. Comparative taxonomic studies on the genus Klebsormidium (Charophyceae) in Europe. In Cryptogamic Studies; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996; Volume 5, pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gaysina, L.A.; Purina, E.S.; Safiullina, L.M.; Bakieva, G.R. Resistance of Klebsormidium flaccidum (Kützing) Silva, Mattox & Blackwell (Streptophyta) to heavy metals. NBU J. Plant Sci. 2009, 3, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gaysina, L.A.; Bohunická, M.; Hazuková, V.; Johansen, J.R. Biodiversity of terrestrial cyanobacteria of the South Ural Region. Cryptogam. Algol. 2018, 39, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaloud, P.; Rindi, F. Ecological differentiation of cryptic species within an asexual protist morphospecies: a case study of filamentous green alga Klebsormidium (Streptophyta). J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2013, 60, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaloud, P.; Lukešova, A.; Malavasi, V.; Ryšánek, D.; Hrčková, K.; Rindi, F. Molecular evidence for the polyphyletic origin of low pH adaptation in the genus Klebsormidium (Klebsormidiophyceae, Streptophyta). Pl. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 147, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Ośródka, L.; Klejnowski, K.; Zejda, J.; Krajny, E.; Wojtylak, M. Air quality index and its significance in environmental health risk communication. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2009, 35, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Environment Bureau Bangkok. AQI Information. Available online: https://bangkokairquality.com/bma/aqi?lang=en (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Hossain, I.; Rahman, S.; Sattar, S.; Haque, M.; Mullick, A.; Siraj, S.; Sultana, N.; Uz-zaman, M.A.; Samima, I.; Haidar, A.; Khan, M. Environmental overview of air quality index (AQI) in Bangladesh: characteristics and challenges in present era. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. 2004. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell: Oxford, USA.

- Bellinger, E.G.; Sigee, D.C. Freshwater Algae: Identification and Use as Bioindicators, 2nd ed.; Wiley–Blackwell: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, K.J.; Haskell, J.B.; Sherman, D.M.; Sherman, L.A. Unicellular, aerobic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria of the genus Cyanothece. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Zhang, C.T. Origins of replication in Cyanothece 51142. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, E.A.; Liberton, M.; Stockel, J.; Loh, T.; Elvitigala, T.; Wang, C.; Wollam, A.; Fulton, R.S.; Clifton, S.W.; Jacobs, J.M.; et al. The genome of Cyanothece 51142, a unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterium important in the marine nitrogen cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 15094–15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareš, J.; Johansen, J.R.; Hauer, T.; Zima, J.Jr.; Ventura, S.; Cuzman, O.; Tiribilli, B.; Kaštovský, J. Taxonomic resolution of the genus Cyanothece (Chroococcales, Cyanobacteria), with a treatment on Gloeothece and three new genera, Crocosphaera, Rippkaea, and Zehria. J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 578–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarek, J.; Cepak, V. Cytomorphological characters supporting the taxonomic validity of Cyanothece (Cyanoprokaryota). Plant Syst. Evol. 1998, 210, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, D.; Rippka, R.; Hernandez-Marine, M. Unusual ultrastructural features in three strains of Cyanothece (cyanobacteria). Arch. Microbiol. 2000, 173, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Sites | Location | Approximate GPS Coordinates | Altitude (m) | Date of Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Urban Site (Vachirabenjatas Park) |

Bangkok | 13° 48.605' N, 100° 33.265' E | 2-7 | May 14, 2022 |

| Eastern Urban Site (Suan Luang Rama IX) |

Bangkok | 13° 41.288' N 100°, 39.488' E | 2-7 | May 15, 2022 |

| Central Urban Site (Lumpini Park) |

Bangkok | 13° 43.884' N 100°, 32.486' E | 4-6 | May 14, 2022 |

| Western Urban Site (Thawi Wanarom Park) |

Bangkok | 13° 44.645' N 100°, 21.139' E | 3-6 | May 13, 2022 |

| Southern Urban Site (Thonburirom Park) |

Bangkok | 13° 39.121' N 100°, 29.484' E | 4-5 | May 13, 2022 |

| Division | Order | Family | (n) Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanophyta | Unclassified | Unclassified | (1) Lusitaniella coriacea |

| Synechococcales | Leptolyngbyaceae | (5) Leptolyngbya sp. 1, Leptolyngbya sp. 2, Oculatella neakameniensis, Leptolyngbya sp. 3, Nodosilinea sp. | |

| Pseudanabaenaceae | (1) Jaaginema littorale | ||

| Synechococcaceae | (4) Synechococcus lividus, Synechococcus sp. Cyanobium gracile, Thermosynechococcus sp. |

||

| Pleurocapsales | Dermocarpellaceae | (2) Stanieria sp.*, Stanieria cyanosphaera | |

| Hyellaceae | (3) Pleurocapsa minor*, Hyella patelloides, Pleurocapsa sp. | ||

| Oscillatoriales | Coleofasciculaceae | (1) Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes | |

| Cyanothecaceae | (6) Cyanothece sp. 1*, Cyanothece sp. 2, Cyanothece sp. 3, Cyanothece sp. 4, Cyanothece sp. 5, Cyanothece sp. 6 | ||

| Gomontiellaceae | (1) Crinalium epipsammum | ||

| Microcoleaceae | (2) Microcoleus sp. 1*, Microcoleus sp. 3 | ||

| Oscillatoriaceae | (5) Oscillatoria nigro-viridis, Lyngbya aestuarii, Phormidium tinctorium, Oscillatoria acuminata, Oscillatoria sp.* | ||

| Nostocales | Aphanizomenonaceae | (2) Dolichospermum compactum, Sphaerospermopsis kisseleviana | |

| Hapalosiphonaceae | (1) Fischerella muscicola | ||

| Nostocaceae | (12) Cylindrospermum stagnale, Nostoc punctiforme, Nostoc linckia, Cylindrospermum sp., Nostoc sp. 1, Nostoc piscinale, Anabaena sp. 1, Nostoc sp. 2, Camptylonemopsis sp., Nostoc carneum, Trichormus azollae, Cylindrospermum muscicola | ||

| Rivulariaceae | (8) Calothrix sp. 1, Calothrix sp. 2*, Microchaete diplosiphon, Calothrix sp. 3, Calothrix brevissima, Calothrix sp. 4, Calothrix sp. 5, Calothrix sp. 6 | ||

| Scytonemataceae | (6) Scytonema mirabile*, Scytonema sp. 1, Scytonema hofmannii, Scytonema crispum, Brasilonema sp., Scytonema sp. 2 | ||

| Tolypothrichaceae | (2) Tolypothrix sp. 1*, Tolypothrix sp. 2* | ||

| Gloeobacterales | Gloeobacteraceae | (1) Gloeobacter kilaueensis | |

| Chroococcidiopsidales | Chroococcidiopsidaceae | (3) Chroococcidiopsis sp. 1*, Chroococcidiopsis thermalis*, Chroococcidiopsis sp. 2 | |

| Chroococcales | Chroococcaceae | (4) Gloeocapsa sp.*, Gloeocapsopsis sp.*, Chondrocystis sp., Gloeocapsopsis crepidinum |

|

| Bacillariophyta | Bacillariales | Bacillariaceae | (2) Nitzschia sp., Cylindrotheca closterium |

| Diadesmidaceae | (1) Diadesmis sp.* | ||

| Chlorophyta | Chaetophorales | Chaetophoraceae | (1) Dilabifilum sp. |

| Chlamydomonadales | Chlamydomonadaceae | (2) Chloromonas perforata, Chlamydomonas zebra | |

| Sphaeropleales | Scenedesmaceae | (2) Scenedesmus sp.*, Acutodesmus sp. | |

| Microthamniales | Unclassified | (1) Trebouxia corticola* | |

| Chlorellales | Chlorellaceae | (2) Nannochloris normandinae*, Lobosphaera incisa | |

| Unclassified | (1) Parachlorella kessleri | ||

| Prasiolales | Prasiolaceae | (1) Edaphochlorella mirabilis | |

| Microthamniales | Unclassified | (1) Friedmannia sp. | |

| Unclassified | Unclassified | (3) Heterochlorella, Watanabea reniformis*, Xylochloris irregularis | |

| Microthamniales | Unclassified | (5) Stichococcus sp., Symbiochloris irregularis, Symbiochloris reticulata, Trebouxia australis, Trebouxia decolorans | |

| Ignatiales | Unclassified | (1) Ignatius tetrasporus* | |

| Pyramimonadales | Unclassified | (1) Pyramimonas disomata | |

| Eustigmatophyta | Eustigmatales | Monodopsidaceae | (2) Monodopsis sp. 2, Nannochloropsis oculata |

| Charophyta | Chlorokybales | Chlorokybaceae | (1) Chlorokybus atmophyticus |

| Klebsormidiales | Klebsormidiaceae | (4) Klebsormidium flaccidum, Klebsormidium sp. 1, Klebsormidium sp. 2*, Klebsormidium sp. 3 |

| Diversity Index (H') | Richness Index | Equitability Index (J') | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Site | 1.37 | 4.43 | 0.3 |

| Eastern Site | 1.71 | 4.65 | 0.37 |

| Central Site | 1.58 | 3.84 | 0.34 |

| Western Site | 1.95 | 6.19 | 0.42 |

| Southern Site | 2.51 | 4.75 | 0.54 |

| Northern Site | Eastern Site | Central Site | Western Site | Southern Site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Site | ‒ | 8 | 22.99 | 15.19 | 27.22 |

| Eastern Site | ‒ | ‒ | 31.92 | 24.29 | 41.04 |

| Central Site | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 41 | 64.82 |

| Western Site | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 54.26 |

| Southern Site | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).