Submitted:

26 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

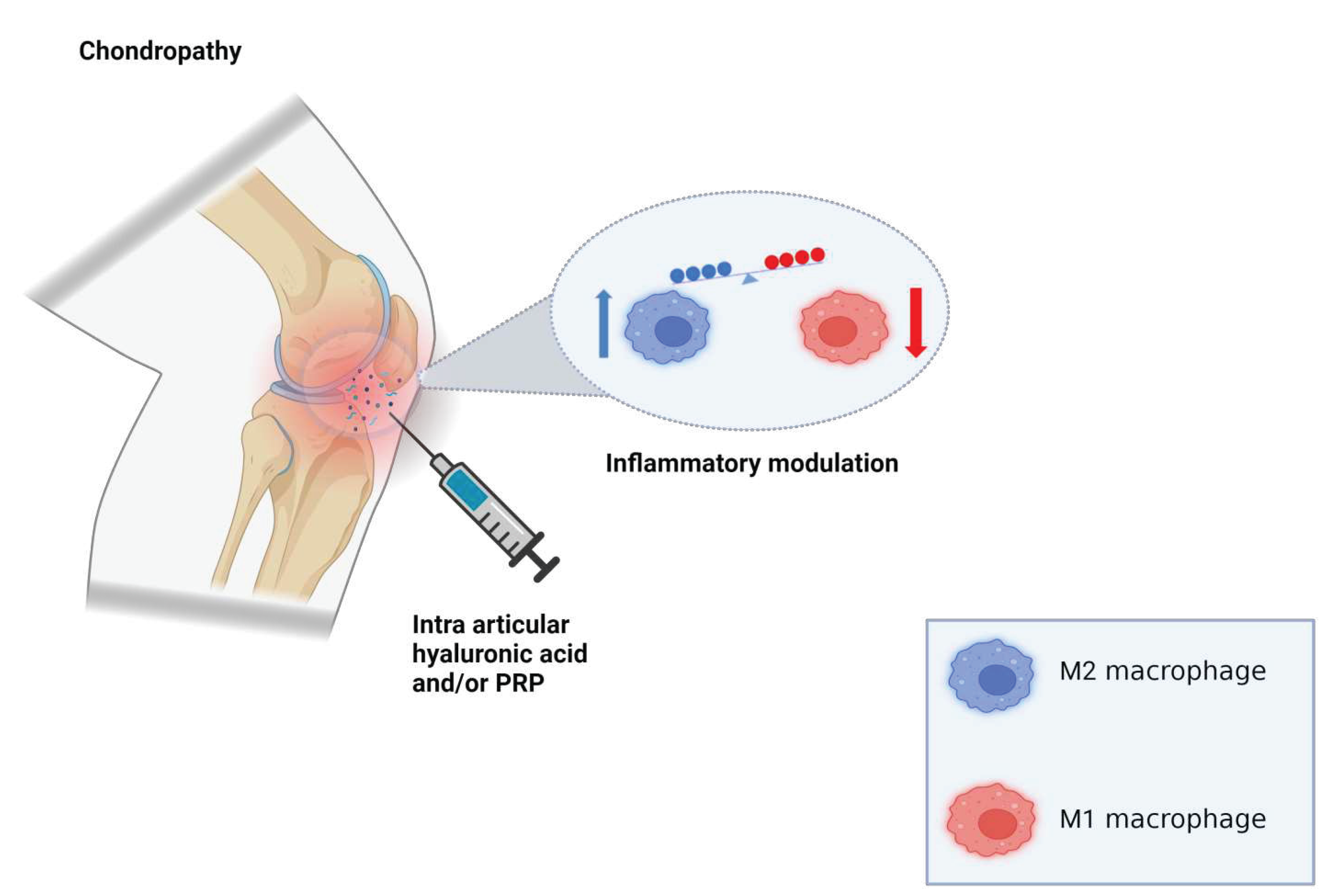

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

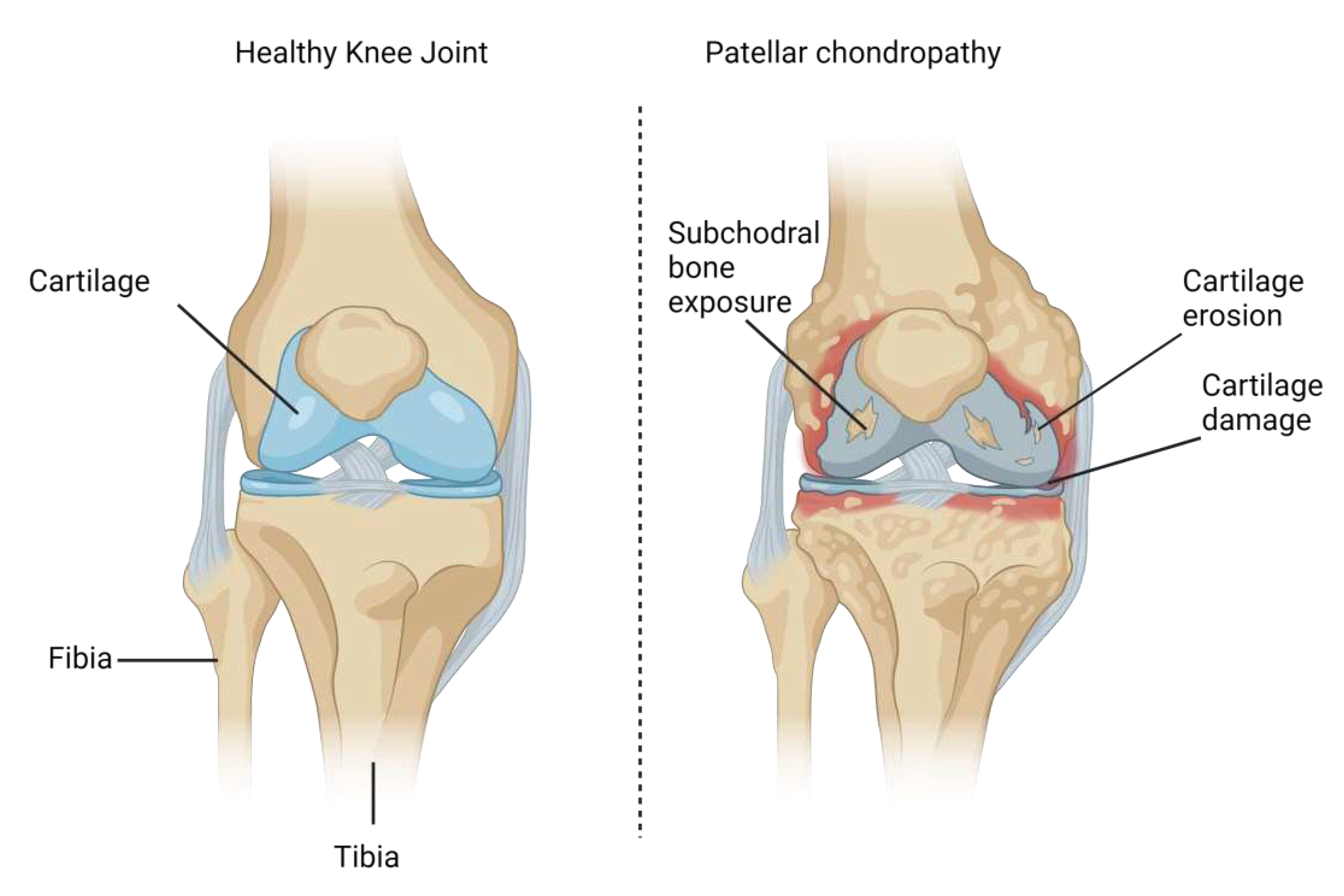

2. Pathophysiology

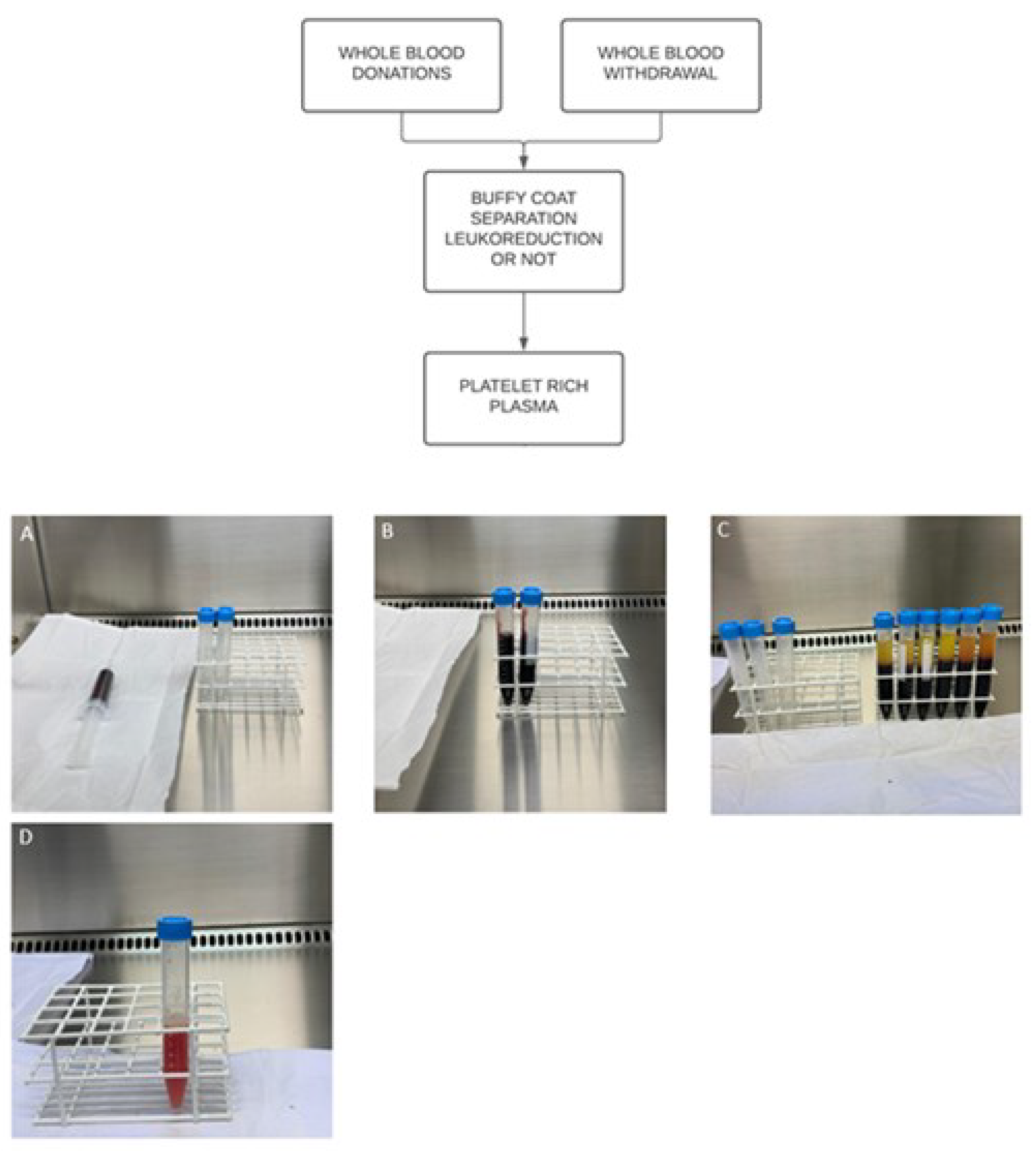

3. PRP

4. Hyaluronic Acid

5. Discussion

6. Author’s Note

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, W.; Li, H.; Hu, K.; Li, L.; Bei, M. Chondromalacia Patellae: Current Options and Emerging Cell Therapies. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R.A.; Sprague, I.S. Outcomes of Prolotherapy in Chondromalacia Patella Patients: Improvements in Pain Level and Function. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2014, 7, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resorlu, H.; Zateri, C.; Nusran, G.; Goksel, F.; Aylanc, N. The Relation between Chondromalacia Patella and Meniscal Tear and the Sulcus Angle/ Trochlear Depth Ratio as a Powerful Predictor. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2017, 30, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, W.; Ellermann, A.; Rembitzki, I.V.; Scheffler, S.; Herbort, M.; Brüggemann, G.P.; Best, R.; Zantop, T.; Liebau, C. Evaluating the Potential Synergistic Benefit of a Realignment Brace on Patients Receiving Exercise Therapy for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016, 136, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizner, R.L.; Petterson, S.C.; Stevens, J.E.; Vandenborne, K.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Early Quadriceps Strength Loss After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005, 87, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravlic, A.H.; Kovač, S.; Pisot, R.; Marusic, U. Neurostructural Correlates of Strength Decrease Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review of the Literature with Meta-Analysis. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Garcia, A.; Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C. Orthobiologics: Current Role in Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2022, 10, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, M.S.; Behera, P.; Patel, S.; Shetty, V. Orthobiologics and Platelet Rich Plasma. Indian J Orthop 2014, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purita, J.; Lana, J.F.S.D.; Kolber, M.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Mosaner, T.; Santos, G.S.; Caliari-Oliveira, C.; Huber, S.C. Bone Marrow-Derived Products: A Classification Proposal – Bone Marrow Aspirate, Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate or Hybrid? WJSC 2020, 12, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lana, J.F.; Purita, J.; Everts, P.A.; De Mendonça Neto, P.A.T.; de Moraes Ferreira Jorge, D.; Mosaner, T.; Huber, S.C.; Azzini, G.O.M.; da Fonseca, L.F.; Jeyaraman, M.; et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma Power-Mix Gel (Ppm)-An Orthobiologic Optimization Protocol Rich in Growth Factors and Fibrin. Gels 2023, 9, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.R.; Costa Marques, M.R.; Costa, V.C.; Santos, G.S.; Martins, R.A.; Santos, M. da S.; Santana, M.H.A.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Jeyaraman, M.; Lana, J.V.B.; et al. Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid in Osteoarthritis and Tendinopathies: Molecular and Clinical Approaches. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.F.S.D.; Lana, A.V.S.D.; da Fonseca, L.F.; Coelho, M.A.; Marques, G.G.; Mosaner, T.; Ribeiro, L.L.; Azzini, G.O.M.; Santos, G.S.; Fonseca, E.; et al. Stromal Vascular Fraction for Knee Osteoarthritis - An Update. J Stem Cells Regen Med 2022, 18, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, H.P.; Maheshwer, B.; Wong, S.E.; Chahla, J.; Cole, B.J.; Yanke, A.B. An Update on the Use of Orthobiologics: Use of Biologics for Osteoarthritis. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Grimalt, R. A Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma: History, Biology, Mechanism of Action, and Classification. Skin Appendage Disorders 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Guidolin, D. Potential Mechanism of Action of Intra-Articular Hyaluronan Therapy in Osteoarthritis: Are the Effects Molecular Weight Dependent? Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örsçelik, A.; Akpancar, S.; Seven, M.M.; Erdem, Y.; Koca, K. The Efficacy of Platelet Rich Plasma and Prolotherapy in Chondromalacia Patella Treatment. Spor Hekimliği Dergisi 2020, 55, 028–037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-V.; Hung, C.-Y.; Aliwarga, F.; Wang, T.-G.; Han, D.-S.; Chen, W.-S. Comparative Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections for Treating Knee Joint Cartilage Degenerative Pathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014, 95, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, V. Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment in Chondromalacia Patellae. JAREM 2017, 7, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, L.; Marom, N.; Dnyanesh, L.; Mei-Dan, O.; Espregueira-Mendes, J.; Gobbi, A. PRP for Degenerative Cartilage Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. CARTILAGE 2017, 8, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; Jorquera, C.; de Dicastillo, L.L.; Fiz, N.; Knörr, J.; Beitia, M.; Aizpurua, B.; Azofra, J.; Delgado, D. Real-World Evidence to Assess the Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Knee Degenerative Pathology: A Prospective Observational Study. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal 2022, 14, 1759720X221100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.; Safi, A.; Komzák, M.; Jajtner, P.; Puskeiler, M.; Hartová, P. Platelet-Rich Plasma in Patients with Tibiofemoral Cartilage Degeneration. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013, 133, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Desouky, I.I. Effectiveness of Intra-Articular Injection of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Isolated Patellofemoral Arthritis. The Egyptian Orthopaedic Journal 2022, 57, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.M.; Kuenze, C.; Bodkin, S.; Hart, J.; Denny, C.; Diduch, D.R. Prospective, Randomized, Double Blind Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Single Dose Hyaluronic Acid for the Treatment of Patellofemoral Chondromalacia. Orthop J Sports Med 2018, 6, 2325967118S00118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jia, M.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z.; Xiao, J. [Hyaluronate acid for treatment of chondromalacia patellae: a 52-week follow-up study]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2019, 39, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, S.R.; da Mota e Albuquerque, R.F.; Helito, C.P.; Camanho, G.L. The Role of Viscosupplementation in Patellar Chondropathy. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2021, 13, 1759720X211015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astur, D.C.; Angelini, F.B.; Santos, M.A.; Arliani, G.G.; Belangero, P.S.; Cohen, M. Use of Exogenous Hyaluronic Acid for the Treatment of Patellar Chondropathy– A Six-Month Randomized Controlled Trial. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 2019, 54, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, B.J.; Karas, V.; Hussey, K.; Merkow, D.B.; Pilz, K.; Fortier, L.A. Hyaluronic Acid Versus Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Prospective, Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Clinical Outcomes and Effects on Intra-Articular Biology for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, R.G.; Santos, G.S.; Alkass, N.; Chiesa, T.L.; Azzini, G.O.; da Fonseca, L.F.; dos Santos, A.F.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Mosaner, T.; Lana, J.F. The Regenerative Mechanisms of Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Review. Cytokine 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzini, G.O.M.; Santos, G.S.; Visoni, S.B.C.; Azzini, V.O.M.; Santos, R.G. dos; Huber, S.C.; Lana, J.F. Metabolic Syndrome and Subchondral Bone Alterations: The Rise of Osteoarthritis – A Review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsi, K.; McKay, J.; Li, J.; Lana, J.F.; Macedo, A.; Santos, G.S.; Murrell, W.D. Nutritional, Metabolic and Genetic Considerations to Optimise Regenerative Medicine Outcome for Knee Osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, H.K.; Donnellan, J.; Ryan, D.; Torreggiani, W.C. Correlation between Subcutaneous Knee Fat Thickness and Chondromalacia Patellae on Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Knee. Can Assoc Radiol J 2013, 64, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Bay-Jensen, A.C.; Lories, R.J.; Abramson, S.; Spector, T.; Pastoureau, P.; Christiansen, C.; Attur, M.; Henriksen, K.; Goldring, S.R.; et al. The Coupling of Bone and Cartilage Turnover in Osteoarthritis: Opportunities for Bone Antiresorptives and Anabolics as Potential Treatments? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadri, A.; Ea, H.K.; Bazille, C.; Hannouche, D.; Lioté, F.; Cohen-Solal, M.E. Osteoprotegerin Inhibits Cartilage Degradation through an Effect on Trabecular Bone in Murine Experimental Osteoarthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, C.; Deberg, M.A.; Piccardi, N.; Msika, P.; Reginster, J.Y.L.; Henrotin, Y.E. Subchondral Bone Osteoblasts Induce Phenotypic Changes in Human Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajeunesse, D. The Role of Bone in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.E.; Miller, R.J.; Malfait, A.-M. OSTEOARTHRITIS JOINT PAIN: THE CYTOKINE CONNECTION. Cytokine 2014, 70, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhou, X.; Scherr, T.; Yang, Y.; Price, C.; Wang, L. Elevated Cross-Talk between Subchondral Bone and Cartilage in Osteoarthritic Joints. Bone 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, W.R.; Roides, B. Musculoskeletal Regeneration. Musculoskeletal Regeneration 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Platelet-Rich Plasma: Evidence to Support Its Use. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, S.; Yuan, Y.; Du, C.; Song, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Fan, Y.; Armstrong, D.G.; Deng, W.; Li, L. Comparison and Investigation of Exosomes Derived from Platelet-Rich Plasma Activated by Different Agonists. Cell Transplant 2021, 30, 9636897211017833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Andia, I.; Zumstein, M.A.; Zhang, C.Q.; Pinto, N.R.; Bielecki, T. Classification of Platelet Concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma-PRP, Platelet-Rich Fibrin-PRF) for Topical and Infiltrative Use in Orthopedic and Sports Medicine: Current Consensus, Clinical Implications and Perspectives. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. [CrossRef]

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Rasmusson, L.; Albrektsson, T. Classification of Platelet Concentrates: From Pure Platelet-Rich Plasma (P-PRP) to Leucocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol 2009, 27, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lana, J.F.S.D.; Purita, J.; Paulus, C.; Huber, S.C.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Rodrigues, A.A.; Santana, M.H.; Madureira, J.L.; Malheiros Luzo, Â.C.; Belangero, W.D.; et al. Contributions for Classification of Platelet Rich Plasma - Proposal of a New Classification: MARSPILL. Regenerative Medicine 2017, 12, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, S.G.; Cole, B.J.; Sundman, E.A.; Karas, V.; Fortier, L.A. Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Milieu of Bioactive Factors. Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, V.; Ciric, M.; Jovanovic, V.; Stojanovic, P. Platelet Rich Plasma: A Short Overview of Certain Bioactive Components. Open Medicine (Poland) 2016. [CrossRef]

- Parrish, W.R.; Roides, B.; Hwang, J.; Mafilios, M.; Story, B.; Bhattacharyya, S. Normal Platelet Function in Platelet Concentrates Requires Non-Platelet Cells: A Comparative in Vitro Evaluation of Leucocyte-Rich (Type 1a) and Leucocyte-Poor (Type 3b) Platelet Concentrates. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2016, 2, e000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, V.; Ciric, M.; Jovanovic, V.; Stojanovic, P. Platelet Rich Plasma: A Short Overview of Certain Bioactive Components. Open Medicine (Poland) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, S.G.; Cole, B.J.; Sundman, E.A.; Karas, V.; Fortier, L.A. Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Milieu of Bioactive Factors. Arthroscopy - Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Fiz, N.; Beitia, M.; Owston, H.E.; Delgado, D.; Jones, E.; Sánchez, M. Effect of Combined Intraosseous and Intraarticular Infiltrations of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma on Subchondral Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Patients with Hip Osteoarthritis. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.E.; Puskas, B.L.; Mandelbaum, B.R.; Gerhardt, M.B.; Rodeo, S.A. Platelet-Rich Plasma: From Basic Science to Clinical Applications. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2009. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meheux, C.J.; McCulloch, P.C.; Lintner, D.M.; Varner, K.E.; Harris, J.D. Efficacy of Intra-Articular Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy 2016, 32, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, J.W.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Houck, D.A.; Goodrich, J.A.; Dragoo, J.L.; McCarty, E.C. Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Hyaluronic Acid for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med 2021, 49, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Cheng, C.; Sun, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Guo, W. Efficacy and Safety of Intra-Articular Platelet-Rich Plasma in Osteoarthritis Knee: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 2191926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-B.; Kim, J.-H.; Ha, C.-W.; Lee, D.-H. Clinical Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection and Its Association With Growth Factors in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Clinical Trial As Compared With Hyaluronic Acid. Am J Sports Med 2021, 49, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, L.-Y.; Zhao, K.; Ruan, J.; Xue, J. Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Orthop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 2325967120973284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-W.; Lin, G.-C.; Lin, H.-S.; Chou, Y.-J.; Liou, I.-H.; Sun, S.-F. Comparing Efficacy of a Single Intraarticular Injection of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Combined with Different Hyaluronans for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022, 23, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Jia, W.; Tuan, R.S.; Zhang, C. Comparative Evaluation of MSCs from Bone Marrow and Adipose Tissue Seeded in PRP-Derived Scaffold for Cartilage Regeneration. Biomaterials 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buul, G.M.; Koevoet, W.L.M.; Kops, N.; Bos, P.K.; Verhaar, J.A.N.; Weinans, H.; Bernsen, M.R.; Van Osch, G.J.V.M. Platelet-Rich Plasma Releasate Inhibits Inflammatory Processes in Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulou, M.; Dai, C.; Tan, X.; Wen, X.; Michalopoulos, G.K.; Liu, Y. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Exerts Its Anti-Inflammatory Action by Disrupting Nuclear Factor-κB Signaling. American Journal of Pathology 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, A.; Patel, S.J.; Song, B.; Sliepka, J.M.; Shybut, T.S.; Lee, B.H.; Jayaram, P. Double-Spin Leukocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich Plasma Is Predominantly Lymphocyte Rich With Notable Concentrations of Other White Blood Cell Subtypes. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022, 4, e335–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.I.; Whitney, K.; Evans, T.; LaPrade, R.F. Platelet-Rich Plasma and Cartilage Repair. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 2018. [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.; Lajeunesse, D.; Hilal, G.; El Atat, O.; Haykal, G.; Serhal, R.; Chalhoub, A.; Khalil, C.; Alaaeddine, N. Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) Induces Chondroprotection via Increasing Autophagy, Anti-Inflammatory Markers, and Decreasing Apoptosis in Human Osteoarthritic Cartilage. Experimental Cell Research 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Prat, L.; Martínez-Vicente, M.; Perdiguero, E.; Ortet, L.; Rodríguez-Ubreva, J.; Rebollo, E.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Gutarra, S.; Ballestar, E.; Serrano, A.L.; et al. Autophagy Maintains Stemness by Preventing Senescence. Nature 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Khosraviani, S.; Noel, S.; Mohan, D.; Donner, T.; Hamad, A.R.A. Interleukin-10 Paradox: A Potent Immunoregulatory Cytokine That Has Been Difficult to Harness for Immunotherapy. Cytokine 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.M.; An, J. Cytokines, Inflammation, and Pain. International Anesthesiology Clinics 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.T.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A. Fibroblasts in Fibrosis: Novel Roles and Mediators. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2014. [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Grose, R. Regulation of Wound Healing by Growth Factors and Cytokines. Physiological Reviews 2003. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Filardo, G.; Mariani, E.; Kon, E.; Marcacci, M.; Pereira Ruiz, M.T.; Facchini, A.; Grigolo, B. Comparison of Platelet-Rich Plasma Formulations for Cartilage Healing: An in Vitro Study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - Series A. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Anitua, E.; Azofra, J.; Aguirre, J.J.; Andia, I. Intra-Articular Injection of an Autologous Preparation Rich in Growth Factors for the Treatment of Knee OA: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008, 26, 910–913. [Google Scholar]

- Opneja, A.; Kapoor, S.; Stavrou, E.X. Contribution of Platelets, the Coagulation and Fibrinolytic Systems to Cutaneous Wound Healing. Thrombosis Research 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nurden, A.T.; Nurden, P.; Sanchez, M.; Andia, I.; Anitua, E. Platelets and Wound Healing. Front Biosci 2008, 13, 3532–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hundelshausen, P.; Koenen, R.R.; Sack, M.; Mause, S.F.; Adriaens, W.; Proudfoot, A.E.I.; Hackeng, T.M.; Weber, C. Heterophilic Interactions of Platelet Factor 4 and RANTES Promote Monocyte Arrest on Endothelium. Blood 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Q.; Kao, K.J. Effect of CXC Chemokine Platelet Factor 4 on Differentiation and Function of Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. International Immunology 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuerer, B.; Ernst, M.; Dürrbaum-Landmann, I.; Fleischer, J.; Grage-Griebenow, E.; Brandt, E.; Flad, H.D.; Petersen, F. The CXC-Chemokine Platelet Factor 4 Promotes Monocyte Survival and Induces Monocyte Differentiation into Macrophages. Blood 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratchev, A.; Kzhyshkowska, J.; Köthe, K.; Muller-Molinet, I.; Kannookadan, S.; Utikal, J.; Goerdt, S. Mφ1 and Mφ2 Can Be Re-Polarized by Th2 or Th1 Cytokines, Respectively, and Respond to Exogenous Danger Signals. Immunobiology 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Sinha, M.; Datta, S.; Abas, M.; Chaffee, S.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Monocyte and Macrophage Plasticity in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. American Journal of Pathology 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lana, J.F.; Huber, S.C.; Purita, J.; Tambeli, C.H.; Santos, G.S.; Paulus, C.; Annichino-Bizzacchi, J.M. Leukocyte-Rich PRP versus Leukocyte-Poor PRP - The Role of Monocyte/Macrophage Function in the Healing Cascade. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meszaros, A.J.; Reichner, J.S.; Albina, J.E. Macrophage-Induced Neutrophil Apoptosis. The Journal of Immunology 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy Reddy, S.H.; Reddy, R.; Babu, N.C.; Ashok, G.N. Stem-Cell Therapy and Platelet-Rich Plasma in Regenerative Medicines: A Review on Pros and Cons of the Technologies. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2018, 22, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latalski, M.; Walczyk, A.; Fatyga, M.; Rutz, E.; Szponder, T.; Bielecki, T.; Danielewicz, A. Allergic Reaction to Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP). Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e14702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cömert Kiliç, S.; Güngörmüş, M. Is Arthrocentesis plus Platelet-Rich Plasma Superior to Arthrocentesis plus Hyaluronic Acid for the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016, 45, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Yan, W.; Leng, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Cheng, J.; Ao, Y. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Placebo in the Treatment of Tendinopathy: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin J Sport Med 2023, 33, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisignoli, G.; Cristino, S.; Piacentini, A.; Cavallo, C.; Caplan, A.I.; Facchini, A. Hyaluronan-Based Polymer Scaffold Modulates the Expression of Inflammatory and Degradative Factors in Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Involvement of Cd44 and Cd54. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, G.M.; Avenoso, A.; Campo, S.; D’Ascola, A.; Traina, P.; Rugolo, C.A.; Calatroni, A. Differential Effect of Molecular Mass Hyaluronan on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Damage in Chondrocytes. Innate Immun 2010, 16, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.J.; de la Motte, C.A. Hyaluronan Cross-Linking: A Protective Mechanism in Inflammation? Trends Immunol 2005, 26, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, K.; Ohno, S.; Fujimoto, K.; Honda, K.; Ijuin, C.; Tanaka, N.; Doi, T.; Nakahara, M.; Tanne, K. Proinflammatory Cytokines Regulate the Gene Expression of Hyaluronic Acid Synthetase in Cultured Rabbit Synovial Membrane Cells. Connect Tissue Res 2001, 42, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheu, E.; Rannou, F.; Reginster, J.Y. Efficacy and Safety of Hyaluronic Acid in the Management of Osteoarthritis: Evidence from Real-Life Setting Trials and Surveys. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.M.; Park, S.J.; Noh, I.; Kim, C.-H. The Effects of the Molecular Weights of Hyaluronic Acid on the Immune Responses. Biomater Res 2021, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Du, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, C.; Gao, F. INT-HA Induces M2-like Macrophage Differentiation of Human Monocytes via TLR4-miR-935 Pathway. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2019, 68, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, R.; Hackel, J.; Niazi, F.; Shaw, P.; Nicholls, M. Efficacy and Safety of Repeated Courses of Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018, 48, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordin, M.; Parrish, W.; Masaquel, C.; Bisson, B.; Copley-Merriman, C. Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid for Osteoarthritis of the Knee in the United States: A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2021, 14, 11795441211047284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Pelletier, J.P.; Branco, J.; Luisa Brandi, M.; Guillemin, F.; Hochberg, M.C.; Kanis, J.A.; Kvien, T.K.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; et al. An Algorithm Recommendation for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Europe and Internationally: A Report from a Task Force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2014, 44, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, P.; Zavan, B.; Vindigni, V.; Schiavinato, A.; Pozzuoli, A.; Iacobellis, C.; Abatangelo, G. In Vitro Response of Osteoarthritic Chondrocytes and Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes to a 500-730 kDa Hyaluronan Amide Derivative. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2012, 100B, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruel, A.V.S.; Ribeiro, L.L.; Gusmão, P.D.; Huber, S.C.; Lana, J.F.S.D. Orthobiologics in the Treatment of Hip Disorders. World J Stem Cells 2021, 13, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julovi, S.M.; Yasuda, T.; Shimizu, M.; Hiramitsu, T.; Nakamura, T. Inhibition of Interleukin-1β-Stimulated Production of Matrix Metalloproteinases by Hyaluronan via CD44 in Human Articular Cartilage. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2004, 50, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaci, A.; Yilmaz, R.H.; Aslan, B.; Sög̈üt, S.; Yanat, A.N.; Uz, E. Effects of Hyaluronan on Nitric Oxide Levels and Superoxide Dismutase Activities in Synovial Fluid in Knee Osteoarthritis. Clinical Rheumatology 2007, 26, 1306–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karna, E.; Miltyk, W.; Surażyński, A.; Pałka, J.A. Protective Effect of Hyaluronic Acid on Interleukin-1-Induced Deregulation of Βeta 1 -Integrin and Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Receptor Signaling and Collagen Biosynthesis in Cultured Human Chondrocytes. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2008, 308, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, M.; Pelotti, P.; De Amicis, D.; Di Iorio, A.; Galletti, S.; Salini, V. Viscosupplementation with Hyaluronic Acid in Hip Osteoarthritis (a Review). Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences 2008, 113, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicker, K.T.; Gurski, L.A.; Pradhan-Bhatt, S.; Witt, R.L.; Farach-Carson, M.C.; Jia, X. Hyaluronan: A Simple Polysaccharide with Diverse Biological Functions. Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 1558–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abatangelo, G.; Vindigni, V.; Avruscio, G.; Pandis, L.; Brun, P. Hyaluronic Acid: Redefining Its Role. Cells 2020, 9, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigetti, D.; Karousou, E.; Viola, M.; Deleonibus, S.; De Luca, G.; Passi, A. Hyaluronan: Biosynthesis and Signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1840, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis, A.; Miralles, A.; Schmidt, R.F.; Belmonte, C. Intra-Articular Injections of Hyaluronan Solutions of Different Elastoviscosity Reduce Nociceptive Nerve Activity in a Model of Osteoarthritic Knee Joint of the Guinea Pig. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2009, 17, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, K.; Cook, J.L.; Kreeger, J.M. Mechanisms of Action and Potential Uses of Hyaluronan in Dogs with Osteoarthritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002, 221, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Gallego, L.; Prieto, J.G.; Coronel, P.; Gamazo, L.E.; Gimeno, M.; Alvarez, A.I. Apoptosis and Nitric Oxide in an Experimental Model of Osteoarthritis in Rabbit after Hyaluronic Acid Treatment. J Orthop Res 2005, 23, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.D.; Moskowitz, R. Intraarticular Sodium Hyaluronate (Hyalgan) in the Treatment of Patients with Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hyalgan Study Group. J Rheumatol 1998, 25, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Kolarz, G.; Kotz, R.; Hochmayer, I. Long-Term Benefits and Repeated Treatment Cycles of Intra-Articular Sodium Hyaluronate (Hyalgan) in Patients with Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2003, 32, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamanna, F.; Giavaresi, G.; Parrilli, A.; Martini, L.; Nicoli Aldini, N.; Abatangelo, G.; Frizziero, A.; Fini, M. Effects of Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid Associated to Chitlac (Arty-Duo®) in a Rat Knee Osteoarthritis Model. J Orthop Res 2019, 37, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarricone, E.; Mattiuzzo, E.; Belluzzi, E.; Elia, R.; Benetti, A.; Venerando, R.; Vindigni, V.; Ruggieri, P.; Brun, P. Anti-Inflammatory Performance of Lactose-Modified Chitosan and Hyaluronic Acid Mixtures in an In Vitro Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation Osteoarthritis Model. Cells 2020, 9, E1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarricone, E.; Elia, R.; Mattiuzzo, E.; Faggian, A.; Pozzuoli, A.; Ruggieri, P.; Brun, P. The Viability and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Hyaluronic Acid-Chitlac-Tracimolone Acetonide- β-Cyclodextrin Complex on Human Chondrocytes. Cartilage 2021, 13, 920S–924S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, A.P.; Dickinson, S.C.; Sims, T.J.; Brun, P.; Cortivo, R.; Kon, E.; Marcacci, M.; Zanasi, S.; Borrione, A.; De Luca, C.; et al. Maturation of Tissue Engineered Cartilage Implanted in Injured and Osteoarthritic Human Knees. Tissue Eng 2006, 12, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lana, J.F.S.D.; Weglein, A.; Sampson, S.E.; Vicente, E.F.; Huber, S.C.; Souza, C.V.; Ambach, M.A.; Vincent, H.; Urban-Paffaro, A.; Onodera, C.M.K.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Hyaluronic Acid, Platelet-Rich Plasma and the Combination of Both in the Treatment of Mild and Moderate Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Stem Cells Regen Med 2016, 12, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levett, P.A.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Malda, J.; Klein, T.J. Hyaluronic Acid Enhances the Mechanical Properties of Tissue-Engineered Cartilage Constructs. PLoS One 2014, 9, e113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbagh, P.; Cannone, A.; Gremion, G.; Gremeaux, V.; Raffoul, W.; Hirt-Burri, N.; Michetti, M.; Abdel-Sayed, P.; Laurent, A.; Wardé, N.; et al. Current Status of PRP Manufacturing Requirements & European Regulatory Frameworks: Practical Tools for the Appropriate Implementation of PRP Therapies in Musculoskeletal Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffler, D.P. Variables Affecting the Potential Efficacy of PRP in Providing Chronic Pain Relief. J Pain Res 2018, 12, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Parihar, A.S.; Pathak, M.; Sharma, V.K. Comparison of Platelet-Rich Plasma Prepared Using Two Methods: Manual Double Spin Method versus a Commercially Available Automated Device. Indian Dermatol Online J 2020, 11, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhurat, R.; Sukesh, M. Principles and Methods of Preparation of Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Review and Author’s Perspective. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2014, 7, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuelson, E.M.; Ebel, J.A.; Reynolds, S.B.; Arnold, R.M.; Brown, D.E. The Cost-Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma Compared With Hyaluronic Acid Injections for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2020, 36, 3072–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, J.; Niazi, F.; Dysart, S. Cost-Effectiveness of Treating Early to Moderate Stage Knee Osteoarthritis with Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid Compared to Conservative Interventions. Adv Ther 2020, 37, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkarappa, R.S.; Chauhan, D.K.; Saikia, B.; Karim, A.; Kanojia, R.K. Metabolic Syndrome and Its Effects on Cartilage Degeneration vs Regeneration: A Pilot Study Using Osteoarthritis Biomarkers. Indian J Orthop 2020, 54, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, S.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Govorukhina, N.; Bischoff, R.; Melgert, B.N. Meta-Inflammation and Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages in Diabetes and Obesity: The Importance of Metabolites. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 746151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussirot, E. Mini-Review: The Contribution of Adipokines to Joint Inflammation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 606560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliddal, H.; Leeds, A.R.; Christensen, R. Osteoarthritis, Obesity and Weight Loss: Evidence, Hypotheses and Horizons - a Scoping Review. Obes Rev 2014, 15, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KURT, M.; ÖNER, A.Y.; UÇAR, M.; ALADAĞ KURT, S. The Relationship between Patellofemoral Arthritis and Fat Tissue Volume, Body Mass Index and Popliteal Artery Intima-Media Thickness through 3T Knee MRI. Turk J Med Sci 2019, 49, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılgöz, V.; Kantarci, M.; Aydın, S. Association between the Subcutaneous Fat Thickness of the Knee and Chondromalacia Patella: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Study. J Int Med Res 2023, 51, 3000605231183581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Radiological Observations |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 (normal) | No radiological findings |

| Grade I | Softening and swelling, edema |

| Grade II | Fragmentation and fissuring in an area of about 1.27cm2 (half an inch) in diameter |

| Grade III | Acute fragmentation and fissuring in an area of greater than 1.27cm2 (half an inch) in diameter |

| Grade IV | Severe cartilage denudation and erosion down to the subchondral bone compartment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).