1. Introduction

Health workforce willingness to work is an important element of health care delivery. This willingness becomes even more important in the context of a pandemic, which places the greatest demands on all the resources of health systems. Moreover, in a pandemic, the mobilization of health workers takes on the character of an emergency. To predict and possibly increase the willingness of health workers to work in a pandemic context, it is imperative to know what has hindered this willingness in similar experiences in the past.

A total of 580 people participated in a comprehensive research study in Australia by completing an online survey. The primary focus of this survey was to gain insight into their propensity and willingness to continue working under the prevailing pandemic conditions. This research was particularly timely and relevant as the survey went live in April 2020, which coincidentally was shortly after the first wave of documented COVID-19 cases in the Australian territories. Those eligible to participate included licensed professionals such as doctors, nurses or midwives, and even paramedics, who were actively working within the Australian medical system at the time of the study. A key aspect of the survey was to understand the internal reasoning of these professionals. Specifically, participants were asked about the balance they struck between their inherent professional obligation, which can be aptly summarized as a sense of “I should do my duty by working,” and the inherent personal risks they faced, including potential contagion and even the very real threat of inadvertently transmitting the virus to loved ones. An overwhelming majority, 75% to be exact, of respondents openly admitted that they had indeed faced this dilemma. The survey also explored the broader perception of risk acceptance within the healthcare profession. Participants were presented with a statement that essentially asked whether, by virtue of being a healthcare professional, there’s an implicit understanding and acceptance of a certain level of risk associated with exposure to infectious diseases in their workplace. The results here were split, with about one-third, or 35%, of respondents expressing disagreement with this notion. It’s worth noting that within this demographic, the survey found a distinction between professions; physicians, for example, were less likely to agree with this idea than their nursing counterparts. However, one factor emerged as clearly critical in shaping the willingness of these professionals to work under such exigent conditions: the availability of and access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). The prominence of PPE in their decision-making process overshadowed most other considerations. In fact, only two other factors came close to its importance: concerns expressed by their family members about their safety and the direct risk of exposure to COVID-19. Interestingly, the relationship between PPE availability and perceived risk of COVID-19 exposure was stronger than the relationship between family concerns and exposure risk. In addition, statistical analysis revealed that the combined effect of family concerns and the risk of COVID-19 exposure on their willingness to work was second only to the effect of access to PPE, underscoring its paramount importance in the decision-making process of healthcare workers during this period [

1].

In a comprehensive research effort conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, a cohort of 187 practicing physicians and an additional 200 medical students were studied in detail. The methodology of the study involved a cross-sectional approach using a web-based survey instrument, which was distributed in June and July 2020. The main objective was to determine both the risk perception and the inclination towards professional duty among this group of respondents in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The structured questionnaire requested a wide range of information, including socio-demographic details. In addition, it explored the sources from which these professionals obtained their COVID-19-related information, their perceptions of the risks associated with the virus, their willingness to serve in such challenging times, and the potential impact of withdrawing from their professional duties. Analysis of the responses revealed that of the 187 physicians, a significant 74.3% continued to serve in the midst of the pandemic. Digging deeper, 58.3% of this subset expressed a willingness to serve, a minority of 10.7% expressed reluctance, and a small percentage (5.3%) remained ambivalent, responding “I don’t know. Conversely, 25.7% of physicians had refrained from working during this pandemic phase. Of the latter group, 16.6% were still willing to work, 4.8% expressed reservations, and another 4.3% were uncertain. An overwhelming 66.8% of physicians felt it was their ethical duty to work in the midst of such a health crisis. Several salient factors bolstered their commitment: a substantial 57.2% felt compelled to work if they were in good health and considered themselves capable; 34.8% based their willingness on possessing adequate knowledge and skills; while 51.3% underscored the importance of being equipped with adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). Financial and health-related incentives also emerged as strong motivators. Physicians felt strongly that certain provisions, such as hazard pay (52.4%), a guarantee of early vaccination for themselves and their families (55.6%), and a promise to pay for medical treatment in the event of a work-related infection (57.8%), would increase their willingness to work. A majority (54.5%) of respondents expressed a high likelihood of contracting the virus due to their occupational exposure, and a slightly higher percentage (59.4%) expressed acute concern about transmitting the virus to their families. Finally, the study also sought to gauge the level of confidence these professionals had in various personal protective equipment. In particular, their highest level of confidence (categorized as “extremely confident”) in the effectiveness of PPE varied: 35.3% for N95 masks, 21.9% for gloves, 27.3% for face shields and 31.6% for gowns [

2].

In a recent study conducted in Pakistan, researchers used a specialized tool designed to measure “willingness to work” (WTW) during the COVID-19 pandemic among the medical community. This tool consisted of a comprehensive 20-item questionnaire stratified into six different facets: perceived pandemic threat, individual risk perception, perceived role importance, role competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic sense of duty. In addition, the study integrated the Maslach Burnout Inventory and collected demographic variables, including gender, level of workload, specific job title or description, and marital status. The methodological approach involved the online collection of data from 250 medical professionals assigned to isolation units or wards caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Participants were asked two specific questions to assess their preliminary inclination to work during a pandemic. The results showed that a significant 42.6% of respondents were in full agreement with providing their services if requested by their respective departments. In contrast, 15.9% expressed reservations or declined to indicate their willingness. The results also revealed that factors such as perceived pandemic threat, role competence, self-efficacy and sense of duty played a significant role in influencing their willingness to work. However, based on the analysis of this study, perceived individual risk and perceived importance of one’s professional role did not have a significant impact on willingness to work during the pandemic [

3].

From April 21 to May 10, 2020, a cross-sectional observational study was conducted in Bangladesh amid the burgeoning phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the country increased from three thousand to fifteen thousand, coinciding with the imposition of lockdown measures. Data for the study were collected online from 422 registered physicians in Bangladesh. The questionnaire used for data collection was three-part. The first section elicited information on sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, and marital status, as well as professional and job-related characteristics such as years of experience, relevant training, exposure to COVID-19 patients, and facilities at the employing hospital. The next segment addressed understanding of the correct use of personal protective equipment (PPE), hand hygiene protocols, and appropriate use of PPE in various clinical scenarios based on World Health Organization guidelines. The final segment was dedicated to assessing physicians’ willingness to work during the pandemic. The measure used to assess willingness was a simple question: “Are you willing to work in your hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic? “ Positive responses were categorized as “willing,” while negative or uncertain responses were considered indicative of unwillingness. Notably, 96% of respondents were confident in their ability to understand the health implications of COVID-19 for both patients and healthcare workers. At the same time, 85% felt knowledgeable about the necessary protective measures. However, approximately half found it cumbersome to comply with PPE recommendations. Crucially, understanding of COVID-19 risks and protective measures, coupled with a belief in the efficacy of appropriate PPE, correlated positively with willingness to work. Nearly half of the respondents felt that their workplace increased their risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, diligent PPE use, high self-reported compliance and reduced risk perception were positively associated with willingness to work. In terms of sheer numbers, 69.7% of physicians were willing to work during the initial lockdown. In contrast, 8.9% were unwilling and 21.4% remained ambivalent. A multivariable logistic model adjusting for several factors showed that younger physicians were more likely to continue working during the pandemic than their older counterparts. In addition, physicians with prior pandemic experience or those working in emergency departments, surgical/gynecological units, or outpatient clinics were more likely to continue working during the pandemic. Conversely, seniority and direct contact with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases decreased willingness. Positive perceptions of protective equipment, understanding of safety measures, and lower perceived risk of infection from the workplace were strong determinants of willingness to serve. Of the 95 physicians who were either unwilling or uncertain about working during the pandemic, 40 gave specific reasons. Family concerns and the potential risk of transmission were the most important. Comorbidities such as bronchial asthma, diabetes, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) were also cited, as were concerns about inadequate safety precautions, fear of personal infection, lack of involvement in clinical practice, inadequate training, and unsatisfactory working conditions [

4].

A study from Palestine sought to assess the willingness of health care workers (HCWs) to serve amid the COVID-19 pandemic, to elucidate the underlying factors, and to identify the ethical challenges they faced. A mixed-methods approach was used, utilizing both qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (questionnaires) mechanisms, targeting frontline HCWs to understand their willingness to serve and related determinants. Data collection was divided into two distinct phases. The first phase used a cross-sectional online survey targeting frontline HCWs—including doctors, nurses, and technical staff in radiology and laboratories—associated with hospitals and primary health care (PHC) centers. This was followed by a second phase of semi-structured interviews, which expanded the scope and depth of the findings. The quantitative component of the survey used a dichotomous questionnaire. The first section captured demographic characteristics such as age, gender, job tenure, work environment, and family responsibilities, and delved deeper into their living arrangements during the outbreak and interactions with confirmed COVID-19 cases. Their commitment to service during the pandemic was assessed through a simple question. The following section used a 0-5 Likert scale to assess the level of stress, attitudes, and potential disillusionment they experienced while performing their duties during the outbreak. Questions probed the source of stress, emphasizing aspects such as fear of vulnerability, potential transmission to loved ones, and lack of preparedness and experience. At the same time, the qualitative phase, enriched by semi-structured interviews, delved into the psyche of HCWs. Rooted in a synthesis of the literature and preliminary quantitative findings, the interview design explored HCWs’ perceptions of their professional obligations during the pandemic, their motivating forces, their camaraderie with peers, obstacles encountered, and predominant challenges. The culmination of the interview was to measure their risk perceptions and associated fears in the prevailing environment. Of the responses collected, 357 were deemed valid. Interestingly, almost a quarter (24.9%) of respondents expressed reservations about serving during the pandemic. Notably, HCWs associated with primary health care, particularly physicians and nurses, expressed a greater willingness to serve. A significant finding was that 78% of respondents with children were more likely to serve. A discernible trend was that HCWs who were less concerned about contracting the virus and felt relatively safe were more willing to serve. Perceived vulnerability and expected severity of COVID-19 disease were significantly associated with willingness to serve. Inexperience with navigating a pandemic and fear of potential isolation or quarantine were determinants of willingness to serve. Those struggling with increased stress levels or feelings of disappointment were less likely to serve during the pandemic [

5].

In summary, the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) consistently emerged across studies as a significant factor in determining willingness to work. Concern about transmitting the virus to family members was a common worry that affected willingness to work. A significant percentage of healthcare workers in these studies felt an ethical obligation to continue working during the pandemic. Factors such as financial incentives, early vaccination and appropriate training could positively influence willingness to work [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study is to show the determinants of willingness to work in physicians who, during the COVID-19 pandemic, did not report knowingly working in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. The data collected in this research is part of a larger study of work ethic during the pandemic, responsibility, and willingness to work. The full questionnaire was constructed from existing constructs in the literature, and the initial intention of the study was to test how participants’ responses are distributed according to theoretical models of responsibility and work willingness. Several studies published at the time of the questionnaire were used to formulate the items [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

At the beginning of the online survey, participants were presented with an informed consent document to review and accept before proceeding. This consent document detailed the purpose of the study, the researchers involved, and the methods of data collection. Participants were informed: “The information you provide will not be linked to your identity. [...] Completing this survey may increase your awareness of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on your personal well-being and your professional experiences during its duration”. Regarding confidentiality, the segment clarified: “By agreeing to participate in this research, your legal rights will remain intact. The information you contribute to this investigation will be collected and secured under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).” The concluding segment of this consent portion read: “By selecting the CONTINUE option, I give my consent to participate in this research.”

The web-based survey was segmented as follows. Questions 1-18 dealt with socio-demographic details such as gender, age, Romanian region of practice, marital status, and other socio-economic data such as household composition, economic self-assessment, and current employment status. Question 19 focused on physicians’ self-reported illnesses. Because the online format allowed respondents to choose from a diverse list, each disease in our database was divided into a yes-or-no format (e.g., “Have you ever had bronchial asthma, including allergic variations?”). Splitting the choices into dichotomous formats was critical to interpreting the data from this question. Questions 20-25 asked about the physician’s specialty and self-assessment of health in the two weeks before and during the pandemic. Question 26 asked about the specific health care settings in which they worked, such as maternity wards or intensive care units. As participants could select multiple settings, these were also dichotomized. From questions 27 to 36, physicians provided insights into their experiences during the pandemic: work locations, average weekly hours, and potential COVID-related hospitalizations. Question 37 explored the different roles a physician might have played during the pandemic, such as collecting specimens or treating respiratory symptoms, with multiple roles possible. Question 99 asked physicians to rank certain factors that influenced their medical practice. Questions 129 and 130 similarly asked for sources of information and supporting resources. These rankings were then deconstructed into distinct variables. The following questions, from 38 to 144, used a 6-point Likert scale and explored various theoretical constructs. While these items weren’t grouped by their respective constructs in the database, each was labeled accordingly. After data collection, certain items were excluded due to their inapplicability to various physicians. Thus, the collected data weren’t consolidated and internal consistency metrics weren’t calculated. IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 was used for data processing.

The study was carried out between July and August 2020. A total of 1,285 Romanian physicians participated, addressing issues such as responsibility, medical ethics, professional drive and self-confidence during the first wave of the pandemic. The respondents reflected a national spectrum, both demographically and geographically. Of these, 982 were female, 302 were male, and one physician preferred not to disclose his or her gender, reflecting the national gender distribution of physicians. The mean age was approximately 48 years. Given the convenience sampling approach, national representation was an aim but not a guarantee. Distribution was primarily web-based through local medical society chapters, with the aim of achieving broad coverage. The exact participation rate remains uncertain due to the multi-channel distribution strategy. The survey included questions on socio-demographics, medical expertise, and work experience. Physicians responded to statements using a six-point scale to indicate agreement or disagreement. This specific scale was designed to eliminate a midpoint, thus preventing neutral responses. The broader research was designed to examine responses in the context of theoretical relationships among self-confidence, work ethic, and professional commitment. However, data characteristics prevented linear regression due to the skewed distribution and prevalence of “not applicable” options. These options were critical to reflect realistic scenarios. An example is item 48: “When asked to work with COVID-19 patients, I was willing to respond. Because not all physicians were asked to work with COVID-19 patients, there was a “not applicable” response option. Another example is item 53: “I was willing to provide direct patient care even though I did not have access to a K95 mask, although I should have used it. Many physicians have had access to masks from the beginning and have never been faced with this situation where they had to decide whether to risk their health. Given these data limitations, nonparametric treatment of the data was deemed the most appropriate analytical approach.

3. Results

The aim of this study is to show the determinants of willingness to work in physicians who, during the COVID-19 pandemic, did not report knowingly working in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. Of the 1285 physicians who participated in the study, 211 (16.4%) reported working in direct contact with patients diagnosed with COVID-19, while 1074 (83.6%) reported not working in direct contact with patients with COVID-19. In terms of cross tabulation with gender, the batch distribution shows that these two categories of physicians are unevenly distributed by gender (χ2(1) = 4.26; p < 0.05). For example, the frequency of males among those who reported working in direct contact with patients diagnosed with COVID-19 is significantly higher than the expected frequency of the whole group (observed count = 61, expected count = 49.4). Physicians who reported working in direct contact with patients diagnosed with COVID-19 are significantly younger (Mann-Whitney U = 98337; Z = -0.339; p < 0.01), but the effect size is relatively modest (Cohen’s d = 0.23).

We performed the statistical test to verify the normality of the data distribution for the items, which were further included in the analysis as dependent variables. For all data sets, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated that the participants’ responses were not normally distributed.

Table 1 presents the results of the normality test.

We performed Mann-Whitney statistical tests comparing the independent groups formed by the dichotomous variable resulting from item 37f: “Healthcare professional reports having direct contact with COVID-19 patients”. Responses to this item were coded as 1 (YES) or 0 (NO).

Table 1 shows the results of the Mann-Whitney comparisons.

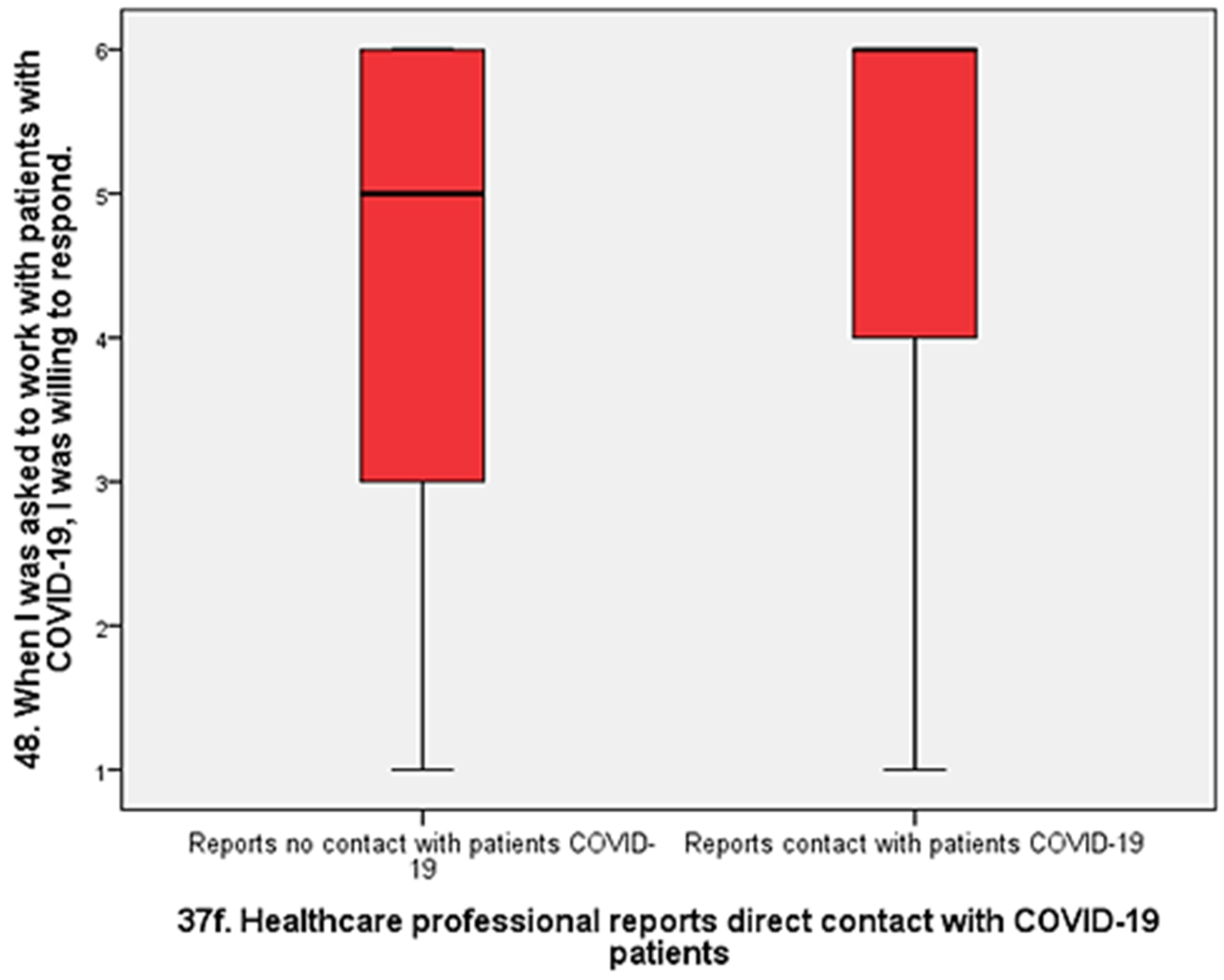

The largest effect we found is that physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19 patients were significantly less willing to work with infected patients than those who reported direct contact with COVID-19 patients (U = 88274; Z = 5.95; p < 0.01; d = 0.47).

Figure 1.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of willingness to work (Mann-Whitney U = 88274; Z = 5.95; p < 0.01; d = 0.47).

Figure 1.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of willingness to work (Mann-Whitney U = 88274; Z = 5.95; p < 0.01; d = 0.47).

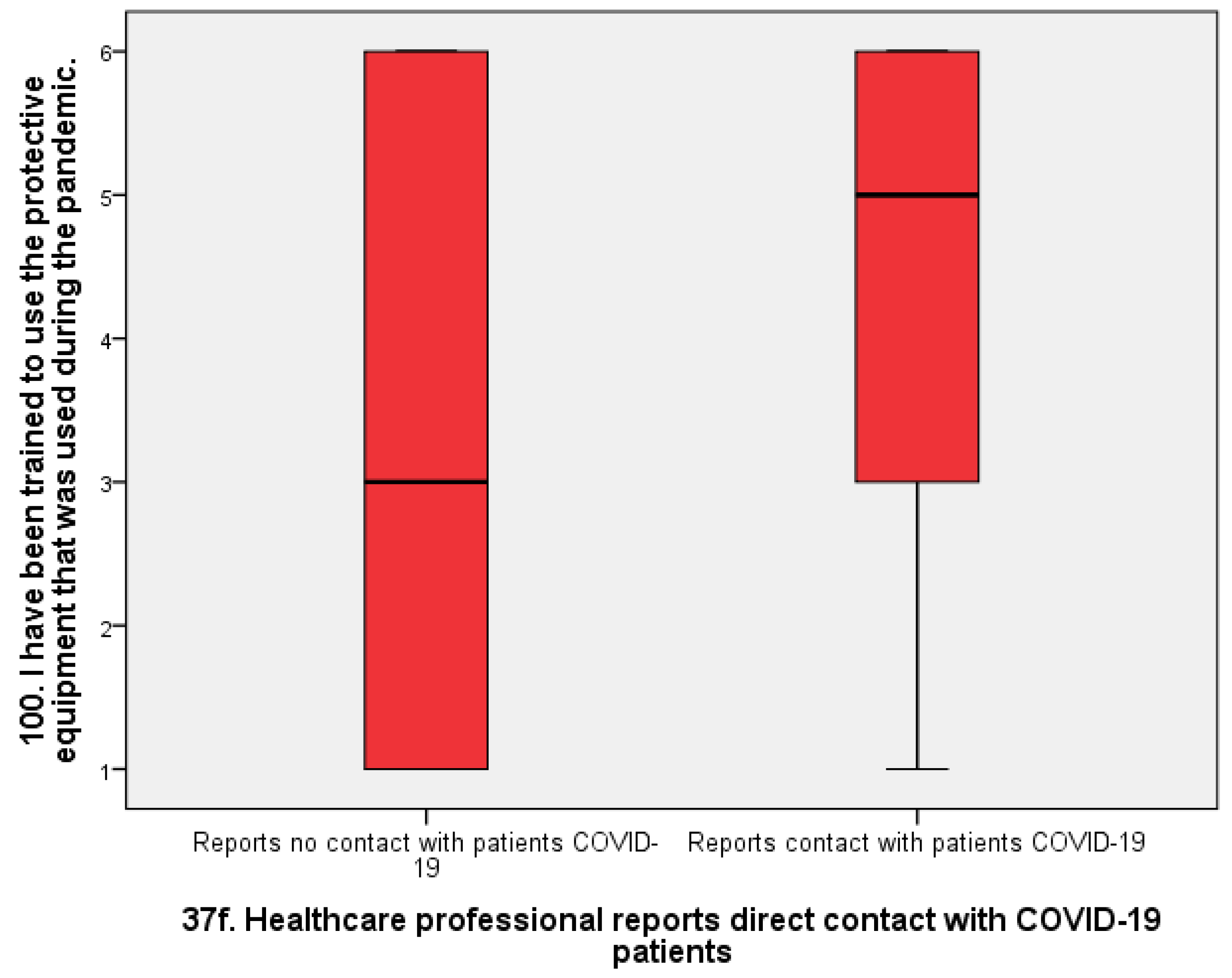

Physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients also reported receiving significantly less training in the use of protective equipment than those who reported direct contact with known COVID-19 patients (Mann-Whitney U = 119354; Z = 4.91; p < 0.01; d = 0.40). Again, the effect size is moderate.

Figure 2.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of training in the use of protective measures (Mann-Whitney U = 119354; Z = 4,91; p < 0.01; d = 0.40).

Figure 2.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of training in the use of protective measures (Mann-Whitney U = 119354; Z = 4,91; p < 0.01; d = 0.40).

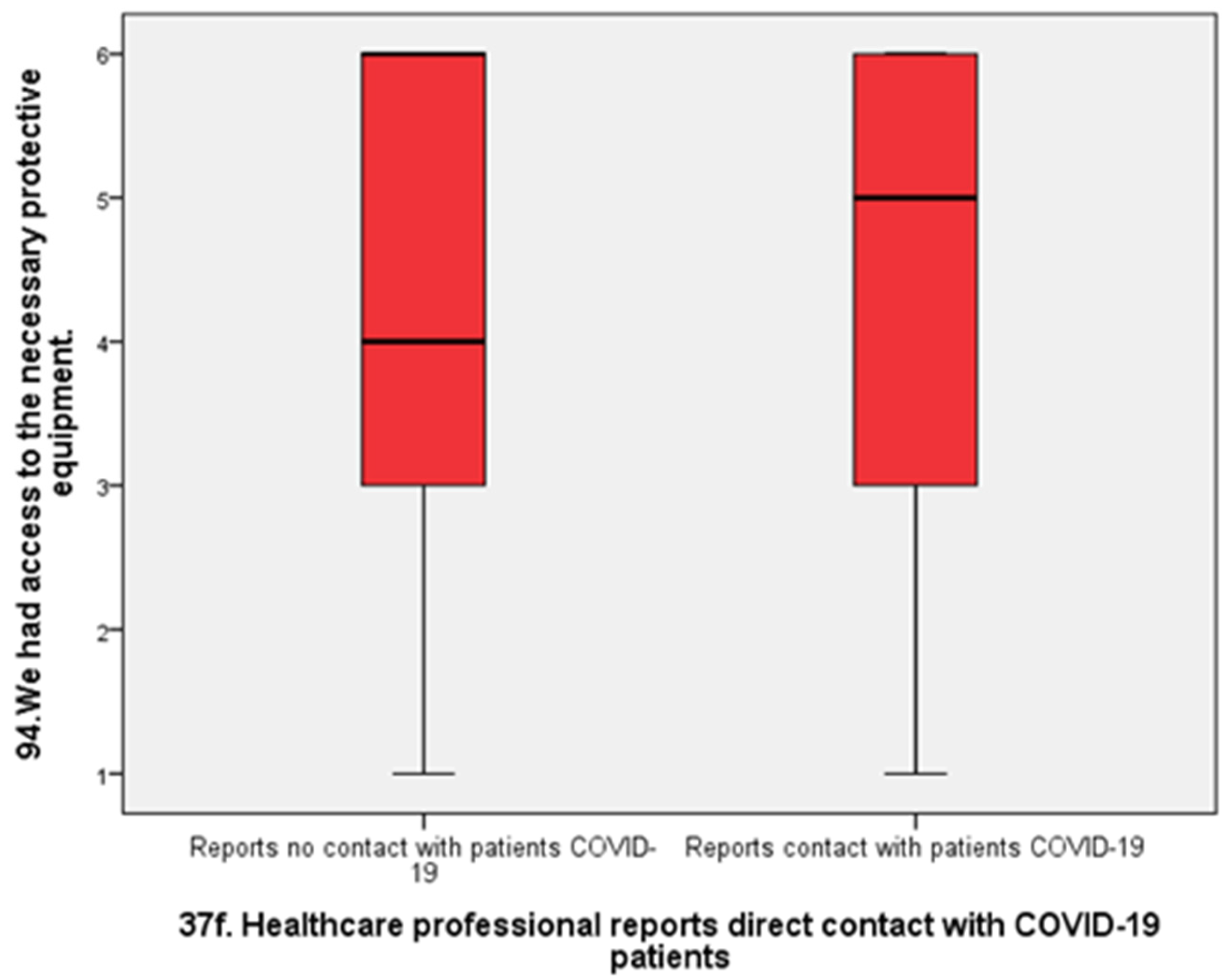

Regarding access to protective equipment, physicians who reported not being in direct contact with patients infected with COVID-19 were significantly less likely to report having access to equipment than physicians who reported being in direct contact with infected patients (Mann-Whitney U = 125.44; p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.26). Effect size is small to moderate.

Figure 3.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of reported access to protective equipment (Mann-Whitney U = 125.44; p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.26).

Figure 3.

Box plot comparing doctors who reported direct contact with infected patients and those who did not report direct contact in terms of reported access to protective equipment (Mann-Whitney U = 125.44; p < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 0.26).

Another result that completes the picture of the information obtained from the statistical processing is the answer to the questions related to the willingness of the doctors to work when one or another of the items constituting the protective equipment, such as the coverall, gloves or mask, was missing. In each of these situations, physicians who reported that they were not in direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients were, on average, more willing to work. This was true for gloves (Mann-Whitney U = 61164; Z = -2.82; p < 0.01; d = 0.23), coveralls (U = 69199.5; Z = -1.99; p < 0.01; d = 0.17), k95 mask (U = 70136; -2.12; p < 0.05; d = 0.16), but also for all equipment (U = 63335; p < 0.01; Z = -2.78; d = 0.20). The effect sizes differed between these situations, with a larger difference between the two categories of physicians for lack of gloves (d = 0.23) and a smaller difference between the two categories of physicians for lack of mask (d = 0.16).

There were no significant differences between physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients and those who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients in terms of confidence in their safety at work (U = 106339.5; p > 0.05) or willingness to work given the increased risk of infecting their own family (U = 110416.5; p > 0.05).

Regarding coercive motivations for working during the pandemic, physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients were significantly more likely than physicians who reported direct contact with COVID-19 patients to report working during the pandemic out of fear of losing their jobs (Mann-Whitney U = 76991; Z = -2. 38; p < 0.05; d = 0.19) or fear of legal repercussions if they refused (Mann-Whitney U = 78124.5; Z = -2.16; p < 0.05; d = 0.14). The effect is modest in both situations, but somewhat larger for fear of job loss.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study is to show the determinants of willingness to work in physicians who, during the COVID-19 pandemic, did not report knowingly working in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. We start with a very important idea that comes from practice. Doctors who worked directly with patients diagnosed with COVID-19 usually used the necessary protective equipment. For example, in the intensive care units of hospitals, it was mandatory for doctors to be fully equipped. In addition, in these first-line units, the equipment was provided most of the time. During all this time, a large proportion of doctors (e.g., family doctors) were not fully equipped most of the time, as they were not necessarily considered to be working with patients with COVID-19. The interesting situation is that despite the lack of diagnosis at the time of consultation, a good proportion of patients were in fact infected with COVID-19. For these doctors, the unrecognized danger was just as great. This idea is supported by our finding that there were no significant difference between physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients and those who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients in terms of confidence in their safety at work. The literature has been generous about the willingness of health professionals to work in general, but has not addressed this difference between those who have knowingly and directly worked with COVID-19 cases and those who have been exposed to COVID-19 cases without being diagnosed. Our data support the hypothesis that the latter physicians were aware of the danger and therefore their willingness to work was lower.

Regarding access to protective equipment, physicians who reported not being in direct contact with patients infected with COVID-19 were significantly less likely to report having access to equipment than physicians who reported being in direct contact with infected patients. For the most part, our data agree very well with data already available in the literature on physicians’ willingness to work during the pandemic. The most striking similarity and the thesis with the most support is the following: a critical factor influencing physicians’ willingness to work during the pandemic is the availability of and access to personal protective equipment (PPE). This conclusion was also explicitly reached by Hill et al. [

1] and Khalid et al. [

2]. Understanding of COVID-19 risks coupled with belief in the effectiveness of PPE correlated positively with willingness to work in the study by Rafi et al. [

4]. Perceived vulnerability was also significantly associated with willingness to work in the study by Maraqa and coworkers [

5]. In our study, we showed that physicians who reported that they did not knowingly have direct contact with patients with COVID-19 had significantly less access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and at the same time were less willing to work. This finding seems to be more understandable in the light of both previous studies and practice.

In terms of the effect we obtained, it is worth noting that there is a real possibility that physicians who reported that they did not come into direct contact with patients diagnosed with COVID-19 may have understood the danger at least as well as those who knowingly encountered COVID-19 patients. We found that there were no significant differences between physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients and those who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients in terms of confidence in their safety at work or willingness to work given the increased risk of infecting their own family. The fact that these physicians consulted patients who were not diagnosed with COVID-19 does not mean that they did not consult patients who may have had COVID-19, especially since the presentation to the physician at that time was for symptoms that were of concern to patients in the context of the pandemic. Knowing that they were less protected than their colleagues in the COVID wards, their willingness to work was significantly lower.

Certainly, the relationship between the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic and physicians’ willingness to work is complex. The most immediate reason is the direct link between PPE and safety. PPE, such as masks, gloves, face shields, and gowns, provides a critical barrier between healthcare workers and the virus. Without it, the risk of contracting the virus increases significantly. Healthcare workers are aware of the risks and may be reluctant to expose themselves without appropriate PPE. Doctors also face a profound ethical dilemma. While they have a professional responsibility to care for patients, they also have a personal responsibility to their own health and the well-being of their families. Without adequate PPE, fulfilling their professional responsibilities may jeopardize their personal responsibilities. In addition, constant exposure to patients with a highly contagious and potentially deadly virus is stressful. This stress is exacerbated when clinicians feel unprotected. Chronic stress can lead to burnout, which can reduce their willingness or ability to work effectively. On the other hand, physicians without PPE not only risk their own health, but can also become vectors for the disease, potentially transmitting it to other patients, colleagues, or family members. This adds another layer of responsibility and stress, which may deter some from working without proper protection. Many physicians may feel that working without proper PPE violates their professional standards. They are trained to follow certain protocols to ensure the highest quality of patient care, and not having PPE compromises these standards. It is also worth noting that if a physician contracts COVID-19 and is quarantined or becomes seriously ill, there are potential financial implications, especially for those in private practice. There may also be career implications if they have to take extended time off work. In addition, a lack of PPE can be perceived as a reflection of how much an institution values its staff. If healthcare workers feel that their institution is not doing enough to protect them, it can undermine trust and reduce their commitment and willingness to work under such conditions. We also know that if some doctors decide not to work because of a lack of PPE, it can influence the decisions of their colleagues. Healthcare is a close-knit community, and the decisions of colleagues can have a ripple effect. Interestingly, working with PPE is physically demanding. Masks can make it difficult to breathe, and gowns can be hot. If PPE is rationed and physicians have to wear it for longer than recommended, this can lead to physical exhaustion, which further affects their willingness to work long hours. In conclusion, the relationship between the availability of PPE and physicians’ willingness to work during the COVID-19 pandemic is influenced by a combination of personal, professional, psychological, and ethical factors. Therefore, the relationship we observed is the same as that observed in the literature and makes sense for several reasons.

It is important to note that we cannot attribute the full effect (d = 0.47) of lower willingness to work among physicians who reported not having direct contact with known cases of COVID-19 to access to equipment or training received. We note that in the group we studied, physicians who reported working in direct contact with patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were significantly younger than the others. Given that some studies capture this relationship between younger age and greater willingness to work [

4], it stands to reason that some of the effect we identified above may be age-related. This may be a limitation in the interpretation of the difference studied.

Another important result is that physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients also reported receiving significantly less training in the use of protective equipment than those who reported direct contact with known COVID-19 patients. Previous findings show that inadequate training in PPE influence willingness to work [

4]. Several explanations are possible. In terms of preparedness and proximity, healthcare facilities with a high number of COVID-19 patients are more likely to prioritize training due to the immediate threat. In areas with fewer cases, or in departments where physicians don’t have direct contact with infected patients, training may be deprioritized, perhaps because of a perceived lower risk. Resource allocation matters: in the early stages of the pandemic, many healthcare facilities were faced with limited resources, including trainers and training materials. It’s plausible that resources were allocated primarily to those on the frontline, directly interacting with COVID-19 patients. The demand for training suggests that physicians in direct contact with COVID-19 patients may actively seek training because they recognize the personal risks associated with their role. In contrast, those not in direct contact may not feel the same urgency. A fourth reason is perceived need. Even if training is available, those who don’t interact with COVID-19 patients may feel that PPE training is not immediately relevant to their current role, especially if the PPE itself is not available. In addition, hospital administrators may focus their immediate training efforts on high-risk departments such as emergency rooms, intensive care units, and COVID units, potentially overlooking other departments. It is also true that as more was learned about the virus, its modes of transmission, and the importance of PPE, facilities may have increased training. Early on, those not in direct contact with COVID-19 patients may have missed the first rounds of training. There is also a possible feedback loop: physicians who are trained may be more willing to work with COVID-19 patients, creating a cycle in which those who are trained continue to gain more experience and possibly more training. Due to possible lack of anticipation, some hospitals may not have anticipated the need to train all physicians, thinking that only specialized units would handle COVID-19 cases. This could lead to a delay in the dissemination of training to all physicians. In areas with lower infection rates, there may be a false sense of security leading to complacency in PPE training for those not in direct contact with infected patients. As other previous findings have suggested, inadequate training affects willingness to work. It’s a cascading effect—those without training may be reluctant to work with infected patients, which means they may not see the need for immediate training, perpetuating the cycle.

Another intriguing finding was the response to questions about physicians’ willingness to work when one or another item of protective equipment, such as coveralls, gloves or masks, was missing. In each of these situations, physicians who reported that they were not in direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients were, on average, more willing to work. This was true for gloves, coveralls, K95 mask, but also for all equipment. The effect sizes differed between these situations, with a larger difference between the two categories of physicians for lack of gloves (d = 0.23) and a smaller difference between the two categories of physicians for lack of mask (d = 0.16). It is interesting to note that physicians who do not report direct contact with patients with COVID-19 are less willing to work overall, but somewhat more willing than their colleagues to work without some form of personal protective equipment (PPE). A possible explanation may be that physicians in dedicated COVID units fully understood the role of PPE, whereas their colleagues with less access to and training in PPE may have understood the general hazard, but may not have linked it as strongly to having or not having PPE. The results we found are not contradictory: in fact, physicians who report no direct contact with patients with COVID-19 have lower willingness to work. This lower willingness to work is related to the lack of protective equipment, but it is possible that their role, although known, was underestimated due to lack of access and training. In contrast to these physicians, physicians who worked in direct contact with patients known to have COVID-19 placed greater emphasis on the relationship between safety and protective equipment. It is important to remember that personal protective equipment is not the only possible means of prevention. There are many other means of prevention, including various types of hand or surface disinfection, patient flow management, etc. When analyzing the dynamics of PSA use among physicians, it’s imperative to consider the multiple influences of their training, the specifics of their work environment, and prevailing professional influences. Physicians who work directly with infected patients typically have a greater appreciation for the role of PPE, due to both their rigorous training and their firsthand encounters with the disease. As a result, this comprehensive understanding may predispose them to be less receptive to compromise on protective measures. Conversely, physicians without direct interactions with COVID-19 patients may not be as aware of the risks associated with omitting certain PPE elements. This divergence isn’t just a reflection of training differences; the work environment is an important determinant. For example, those working in areas with limited exposure to aerosol-generating processes may operate under a reduced perceived threat, leading to assumptions regarding the need for comprehensive PPE. Collegial behavior is a notable influence on this paradigm. Prevailing practices and norms among peers can significantly shape individual PPE use behaviors. For example, if a discernible majority in a non-COVID station operates without certain PPE elements, it could establish an unofficial standard, thereby influencing the decision-making dynamics of the broader group. Still, it’s important to recognize the overarching institutional frameworks at play. Different institutional protocols may define PPE guidelines, with some institutions perhaps imposing more stringent measures for COVID-centric wards than others. Such disparities may lead to different levels of willingness to complete PPE in different units. Historical interactions with PPE also play a role. Physicians who have operated without comprehensive PPE in the past without discernible adverse outcomes may inherently underestimate the risks involved. For some, the demands of their role may lead them to internally justify reduced PPE as a necessary trade-off. In addition, external determinants such as media narratives or institutional communiqués should not be overlooked. Emphasis on specific PPE items, such as masks, in these channels may inevitably shape physicians’ prioritization and perception of particular protective elements.

The smaller difference between the two categories of physicians for willingness to work without a K95 mask (d = 0.16) and the larger difference for gloves (d = 0.23) is in perfect agreement with the findings of Khalid and colleagues [

2]. In their study, the piece of equipment with the highest level of confidence was the mask (35.5% were extremely confident that the mask would protect them). The item with the lowest percentage of confidence was gloves (21.9% were extremely confident). This can be interpreted as a situation where those who are familiar with PPE may have a better understanding of the equipment that provides the most protection, while those who haven’t received training and have not had special access to PPE may have a less thorough evaluation of this PPE.

Regarding coercive motivations for working during the pandemic, physicians who reported no direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients were significantly more likely than physicians who reported direct contact with COVID-19 patients to report working during the pandemic out of fear of losing their jobs (d = 0.19) or fear of legal repercussions if they refused (d = 0.14). The effect is modest in both situations, but somewhat larger for fear of job loss. The data reveal this intriguing disparity: Physicians without direct reported interactions with COVID-19-infected patients manifested a significantly higher propensity to cite extrinsic pressures, such as concerns about job security (d = 0.19) and fears of legal repercussions (d = 0.14), as motivators for their continued service during the pandemic than did their counterparts with direct interactions with infected patients. Several hypotheses may explain this observed discrepancy. Physicians working directly with COVID-19 patients may perceive their role as indispensable because they are on the front lines of a global health crisis, and thus feel more secure in their positions. Conversely, physicians without direct contact with COVID-19 patients may feel more vulnerable to job loss, especially if their specialties or roles were considered less critical during the peak of the pandemic. On the other hand, the nature and tone of communication from hospital administrators or health departments may differ by department or specialty. Those not directly involved with COVID-19 cases may have received more coercive messages emphasizing the potential consequences of non-compliance. It is also possible that physicians directly treating COVID-19 patients are acutely aware of the risks they face, which may translate into a more intrinsic motivation to work, prioritizing patient care over potential external pressures. Those not directly exposed may be more susceptible to external pressures because the immediacy of the health risk is less palpable. Role valorization may also play a role. Direct patient care roles during a pandemic may be associated with valor or societal esteem, reducing the perceived weight of external pressures. In contrast, those in roles with less direct patient interaction may not benefit from the same level of public or institutional valorization, making external pressures more salient. Peer attitudes and choices can also profoundly shape individual perceptions and decisions. If a predominant segment of non-COVID treating physicians felt and discussed fears of job loss or legal repercussions, it could reinforce and amplify these concerns within that group.

The primary source of bias in the study stemmed from the participants’ voluntary decision to participate. While keeping responses anonymous was one strategy to reduce this problem, it couldn’t eliminate self-selection bias. It’s plausible that physicians who were particularly overwhelmed or highly dissatisfied may have been less likely to participate. These potential biases highlight the limitations of the research. In addition, the distribution of the survey through professional circles and associations could introduce another layer of bias. Physicians who are more involved in professional circles or who actively use online platforms may have been more likely to respond. Conversely, those who are less digitally active, less likely to read association updates, or less connected may have been underrepresented.

Another limitation was the study’s inability to pool responses from different questions to derive overarching themes or constructs. Ideally, a cumulative score across multiple questions would have been derived for aspects such as self-belief. Such an approach would have required consistency checks and assessments of score distributions. However, the varying applicability of certain questions to different physicians made the pooling of responses challenging. In practice, the diversity of situations exceeded our initial projections.

While the size of the respondent base in this study is commendable, it is critical to delineate several inherent limitations. One notable limitation stems from the modest size of certain effect sizes. Specifically, the effect sizes related to overall willingness to work (d = 0.47) and access to PPE (d = 0.40) are of moderate magnitude. Other effect sizes, ranging from 0.14 to 0.23, suggest that our results may be more indicative of overarching trends rather than definitive differences between the two physician groups. Such subtleties underscore the need for more extensive research in the future. In addition, the potential influence of unaddressed confounding variables cannot be ruled out. The mere demonstration of differences between two independent groups does not imply a causal relationship. Hidden variables could influence the differences, requiring models that account for such complex interactions. Therefore, any broad generalizations of our conclusions must be made with caution and must be supported by subsequent studies. Another area of concern is the use of a single-item measure for the dependent variable. While this approach is consistent with previous methodologies, such as Rafi et al.’s [

4], it’s important to note that the study treated these responses as a non-normally distributed variable. An inherent limitation of nonparametric statistics is the potentially reduced power to detect nuanced differences. Future research efforts may shed light on more significant determinants that influence willingness to work. A complex metric, as suggested by Mushtaque and colleagues [

3], that uses multiple items to measure readiness, especially during a pandemic, could provide deeper insights. The survey’s “not applicable” response option introduces additional complications. This option was introduced not to be neutral, but to consider the practical circumstances faced by different physicians. For example, self-employed physicians may choose “not applicable” in response to a statement such as “My employer and I share the same values. Such pragmatic choices, while necessary, could potentially compromise the statistical power and representativeness of the survey. Despite the anonymized format of the survey, the issue of self-selection bias remains paramount. The potential non-representation of overworked or dissatisfied physicians and skewed distribution through professional networks could influence the results. Engagement with professional newsletters, Internet accessibility, and the strength of professional connections may have served as determinants of participation.

In addition, the study’s focus on a cohort of Romanian physicians poses challenges in terms of global generalizability. While the sample adequately represents Romanian physicians, extrapolating these observations to an international setting would be premature. Cultural differences may influence perceptions of the determinants of work engagement. Global replications, using culturally adapted standardized instruments, are critical to developing a comprehensive theoretical framework regarding physician willingness to work during pandemics. Nevertheless, the study’s strengths remain its large observational size and its careful analytic methodology that mitigates false positives.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study is to show the determinants of willingness to work in physicians who, during the COVID-19 pandemic, did not report knowingly working in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. Our observations underscore a critical insight derived from real-world practice. Physicians directly engaging with confirmed COVID-19 patients, especially those stationed in intensive care units, routinely utilized the requisite personal protective equipment (PPE) and, more often than not, had it readily supplied. Contrastingly, a significant number of practitioners, such as family doctors, did not consistently have access to comprehensive PPE, given they were not primarily perceived as interfacing with COVID-19 patients. Intriguingly, despite the absence of immediate diagnosis during consultations, a sizable fraction of their patients were, in reality, COVID-19 carriers. Consequently, these physicians faced an equally potent, albeit unrecognized, hazard. This unseen risk was substantial, a notion supported by our observation that confidence in workplace safety was comparable between physicians with known and unknown exposure to COVID-19. A consistent theme of our data, echoing the findings in previous studies, is that the availability of and access to PPE is a critical determinant of physicians’ willingness to work during the pandemic. Importantly, physicians who were unknowingly exposed to COVID-19 cases perceived the danger similarly to those with direct exposure and, given their often less protective measures, demonstrated a reduced willingness to work.

The relationship between the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) and physicians’ willingness to work during the COVID-19 pandemic is complex and influenced by personal, professional, psychological, and ethical considerations. PPE acts as a critical shield, and its absence significantly increases the risk of viral transmission. Our results indicate that physicians without direct contact with known COVID-19 cases reported less access to PPE and related training. Interestingly, while they reported lower overall work engagement due to lack of PPE, they appeared to be somewhat more willing to work without certain PPE items compared to those with direct contact with COVID-19 patients. This difference suggests that physicians who have direct contact with COVID-19 patients have a heightened understanding of the importance of PPE due to intensive training and first-hand experience. However, physicians without such encounters may not fully appreciate the risks associated with specific PPE omissions. In addition, a striking finding in line with previous studies, was the variance in confidence levels for different PPE items. For example, masks elicited higher levels of confidence than gloves. This suggests that experience and training with PPE may lead to a more nuanced understanding and evaluation of individual protective items.

Physicians without direct contact with COVID-19 patients were more likely to report working during the pandemic due to fears of job loss or legal repercussions than those who had direct contact. This disparity suggests that physicians directly treating infected patients may feel their roles are indispensable, leading to intrinsic motivation to work. In contrast, physicians without direct contact may feel more susceptible to external pressures and less societal valorization. Peer attitudes could also influence these perceptions

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Ș.R., Ș.C., O.A., D.C. and L.O.; Methodology, T.-Ș.R., A.P. and L.O.; Validation, T.-Ș.R. and L.O.; Formal analysis, T.-Ș.R., A.P., O.A. and L.O.; Investigation, T.-Ș.R., A.P., Ș.C. and L.O.; Resources, T.-Ș.R., A.P., Ș.C., D.C. and L.O.; Data curation, T.-Ș.R., A.P., O.A. and L.O.; Writing—original draft, T.-Ș.R. and L.O.; Writing—review and editing, A.P., Ș.C., O.A., D.C. and L.O.; Supervision, T.-Ș.R., Ș.C., D.C. and L.O.; Project administration, T.-Ș.R., A.P., Ș.C. and L.O.; Funding acquisition, L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Medicine and Pharmacy Gr. T. Popa Iași (protocol code RESPECT in 24.06.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hill M, Smith E, Mills B. Willingness to Work amongst Australian Frontline Healthcare Workers during Australia’s First Wave of Covid-19 Community Transmission: Results of an Online Survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2021, 17, e44. [CrossRef]

- Khalid M, Khalid H, Bhimani S, et al. Risk Perception and Willingness to Work Among Doctors and Medical Students of Karachi, Pakistan During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 3265–3273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaque I, Raza AZ, Khan AA, Jafri QA. Medical Staff Work Burnout and Willingness to Work during COVID-19 Pandemic Situation in Pakistan. Hosp Top 2022, 100, 123–131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafi MA, Hasan MT, Azad DT, et al. Willingness to work during initial lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic: Study based on an online survey among physicians of Bangladesh. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245885. [CrossRef]

- Maraqa B, Nazzal Z, Zink T. Mixed Method Study to Explore Ethical Dilemmas and Health Care Workers’ Willingness to Work Amid COVID-19 Pandemic in Palestine. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 576820. [CrossRef]

- Damery S, Wilson S, Draper H, et al. Will the NHS continue to fu nction in an influenza pandemic? a survey of healthcare workers in the West Midlands, UK. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett DJ, Balicer RD, Thompson CB, et al. Assessment of local public health workers’ willingness to respond to pandemic influenza through application of the extended parallel process model. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6365. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett DJ, Levine R, Thompson CB, et al. Gauging U.S. Emergency Medical Services workers’ willingness to respond to pandemic influenza using a threat- and efficacy-based assessment framework. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9856. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenstein BP, Hanses F, Salzberger B. Influenza pandemic and professional duty: family or patients first? A survey of hospital employees. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 311. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackler N, Wilkerson W, Cinti S. Will first-responders show up for work during a pandemic? Lessons from a smallpox vaccination survey of paramedics. Disaster Manag Response 2007, 5, 45–48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).