Submitted:

29 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

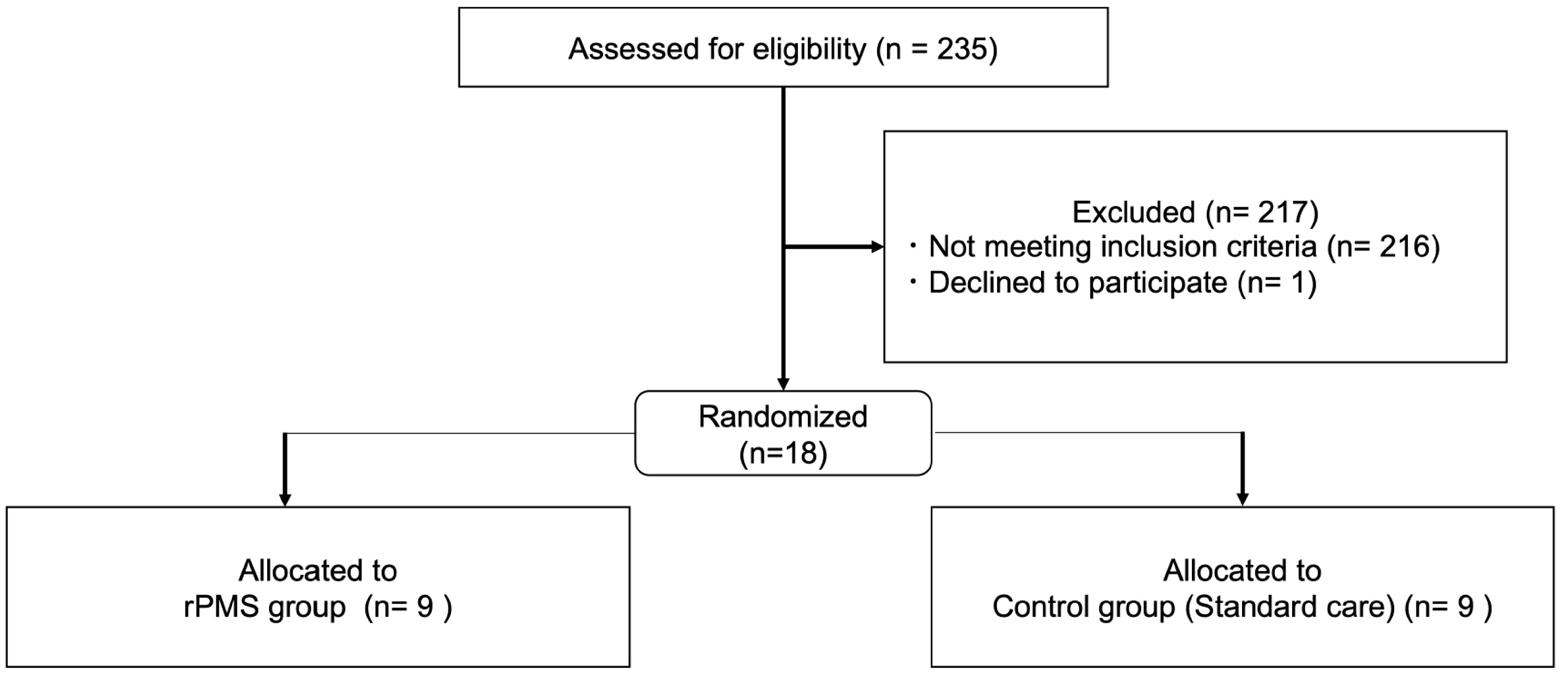

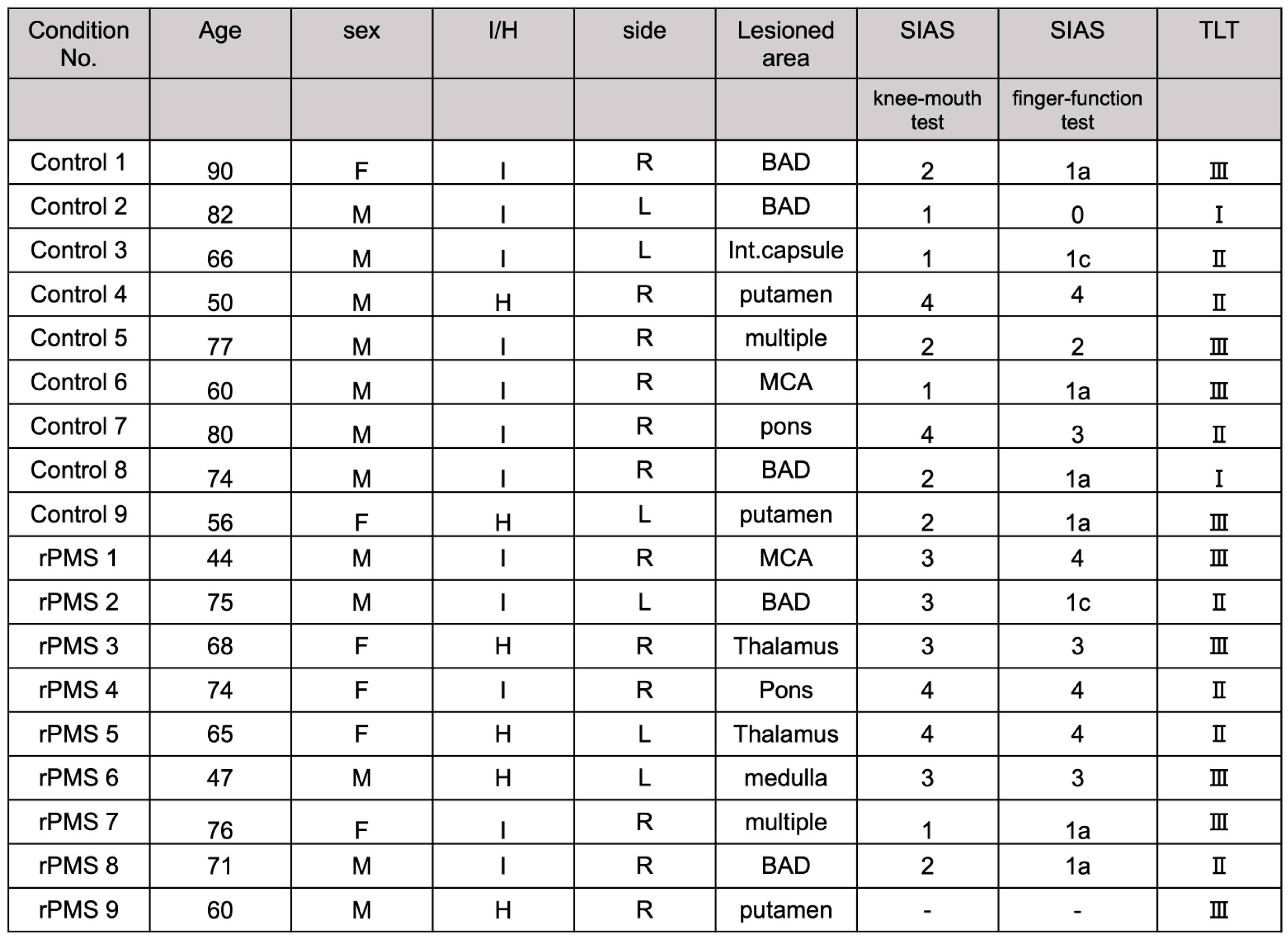

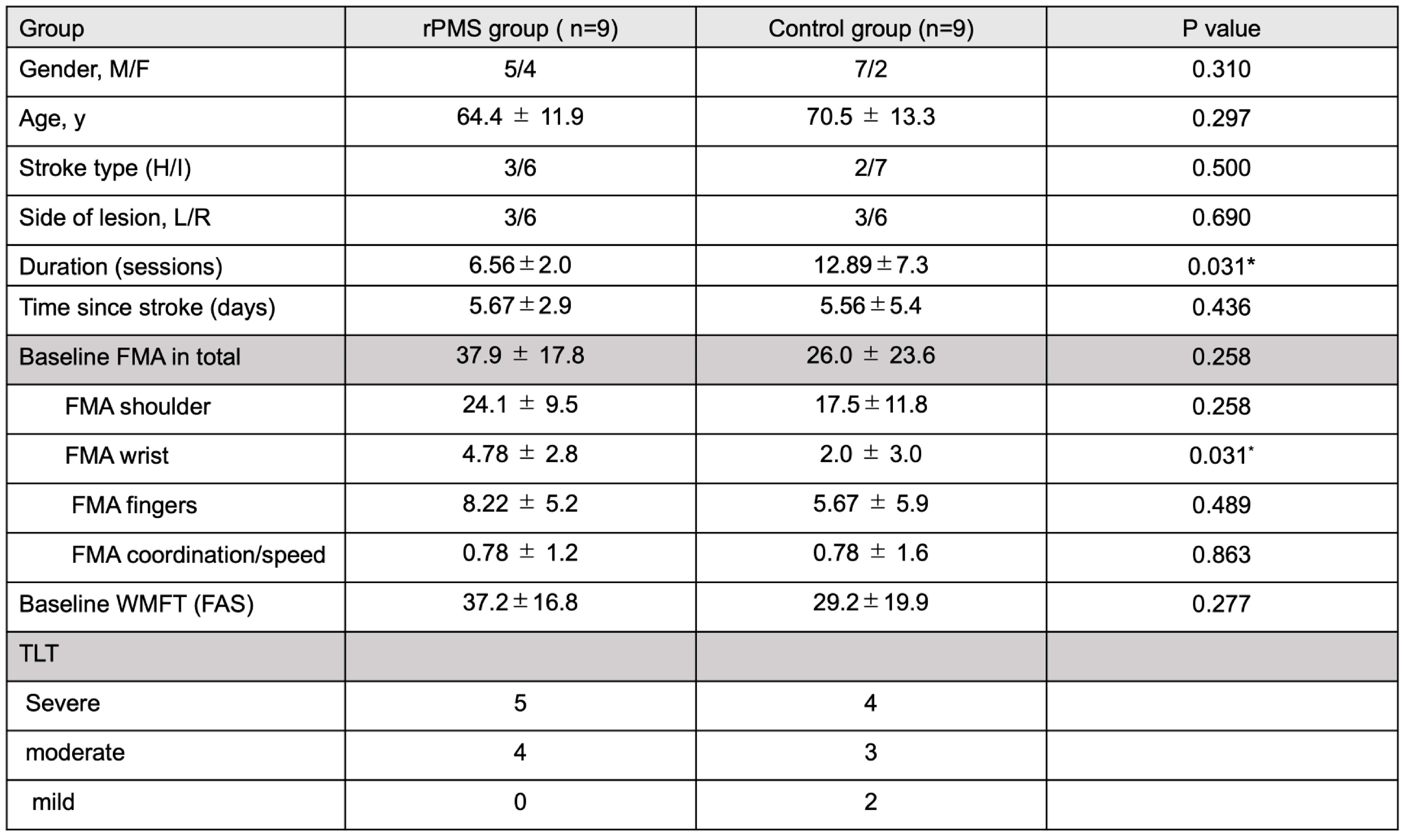

2.1. Participants

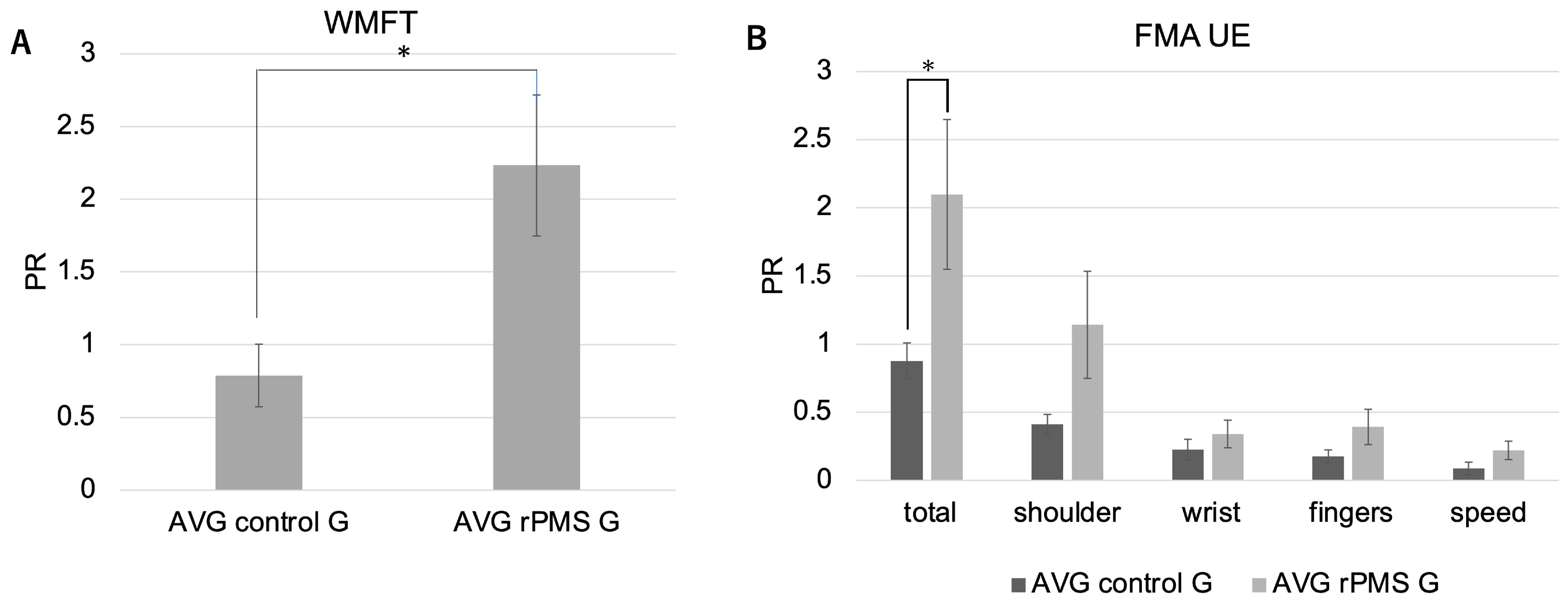

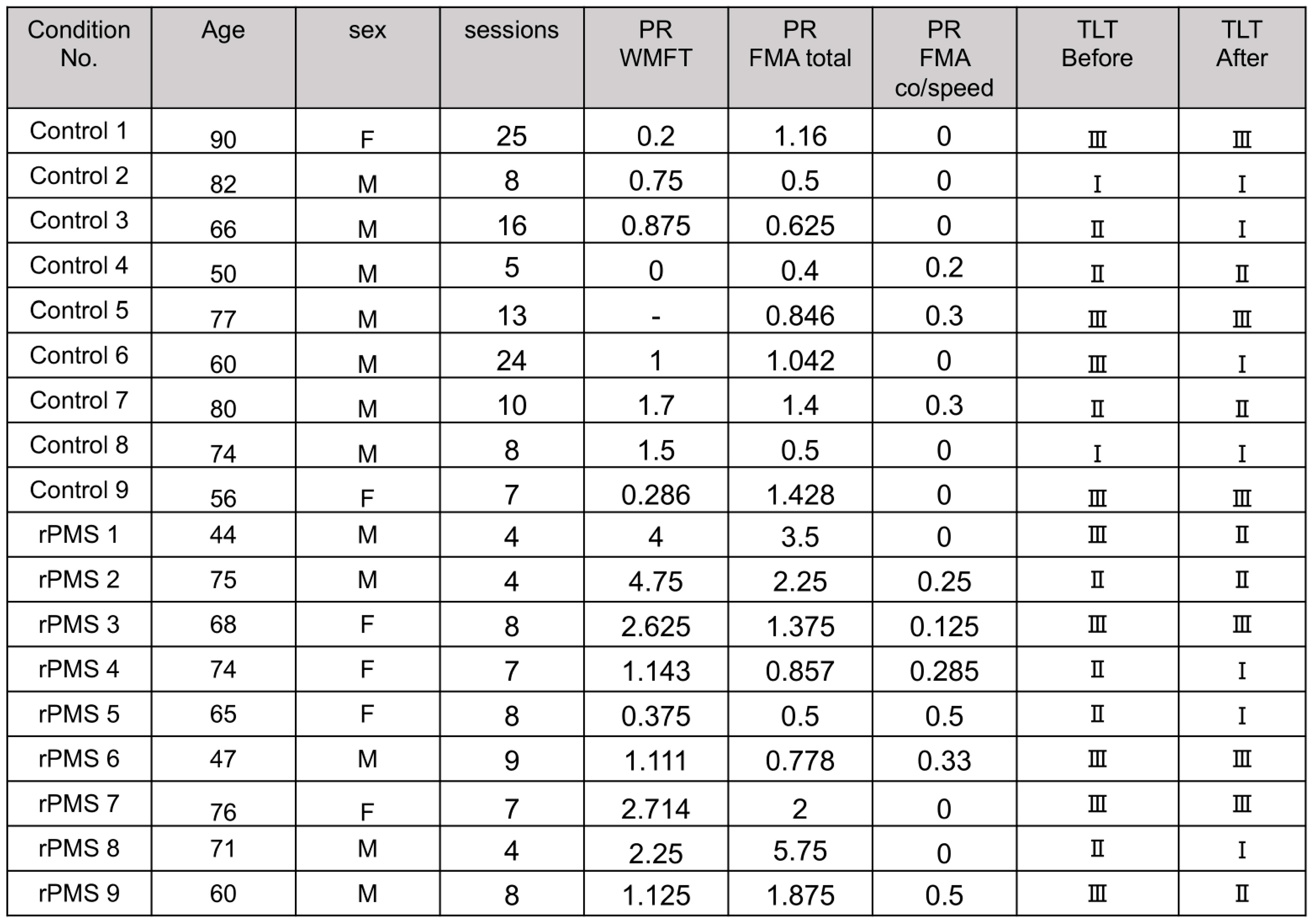

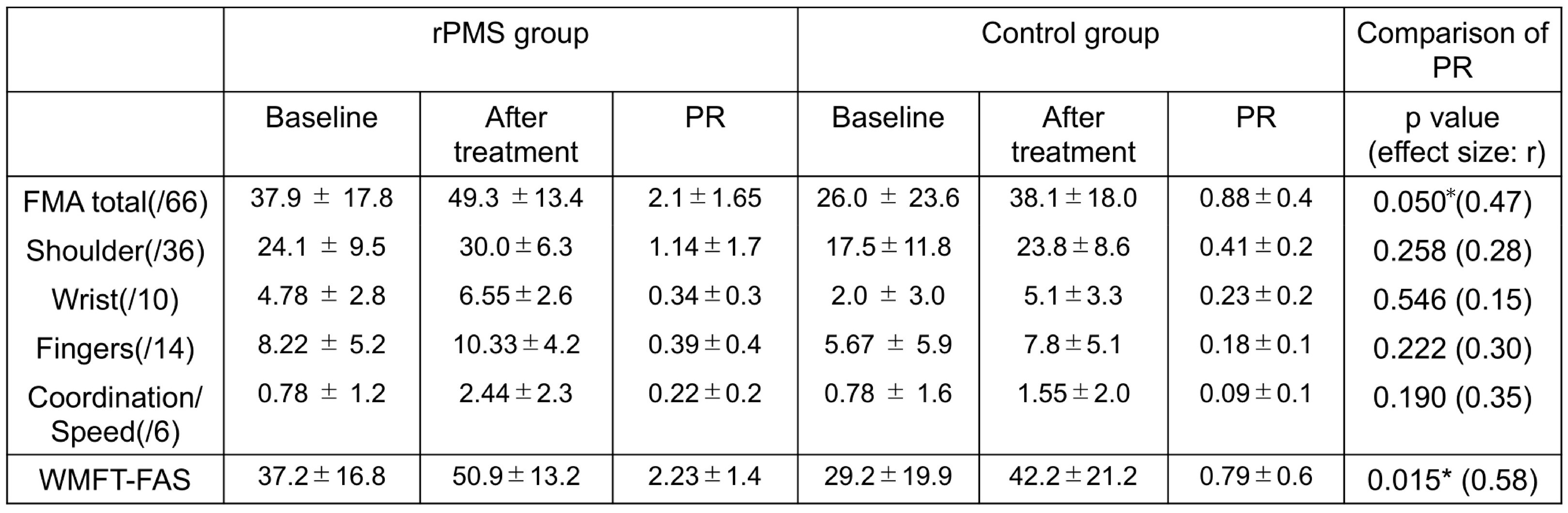

2.2. Effects of rPMS on motor recovery

2.3. Effects of rPMS on proprioceptive function

2.4. Others

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

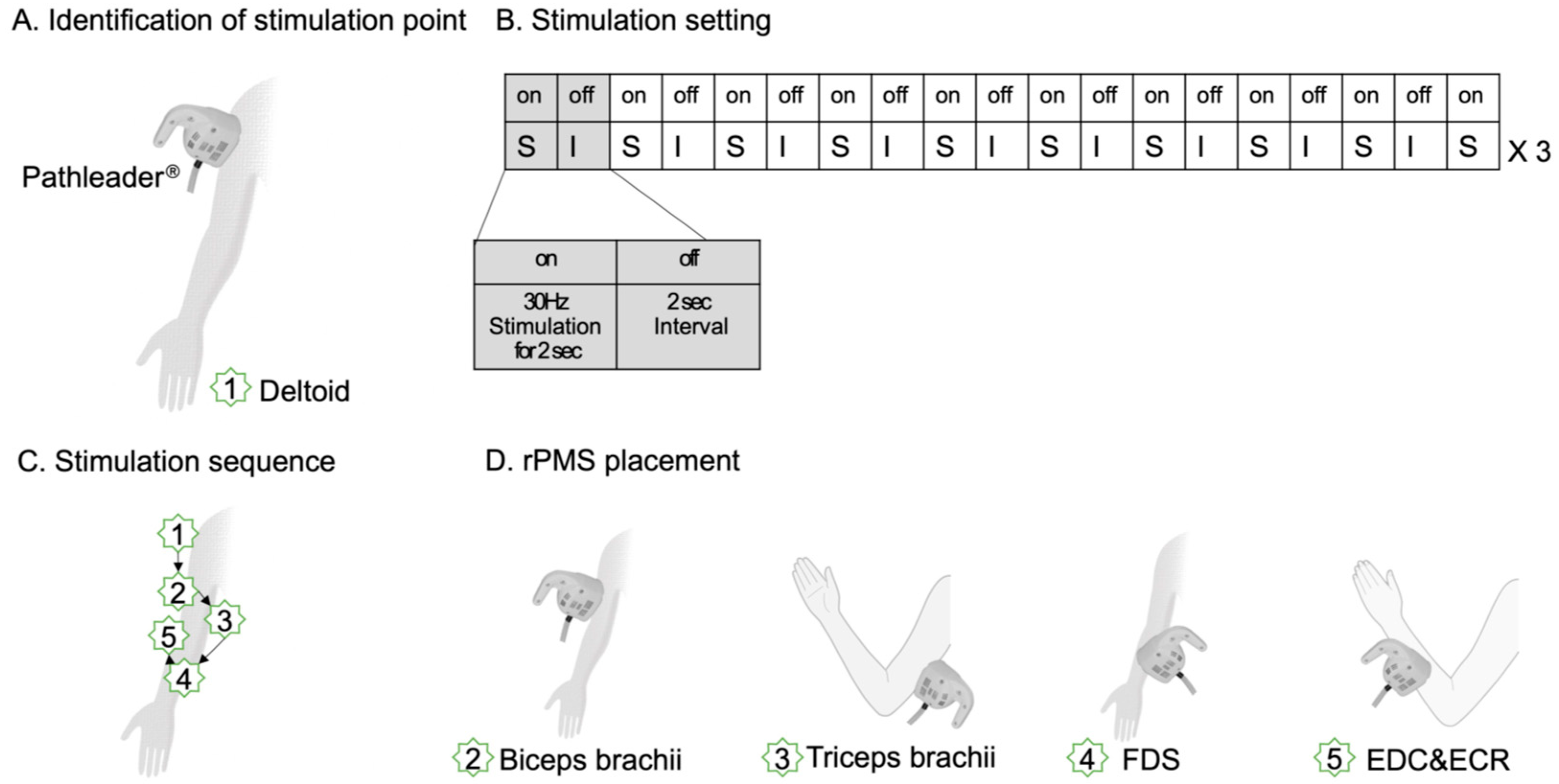

4.2. Interventional Protocols

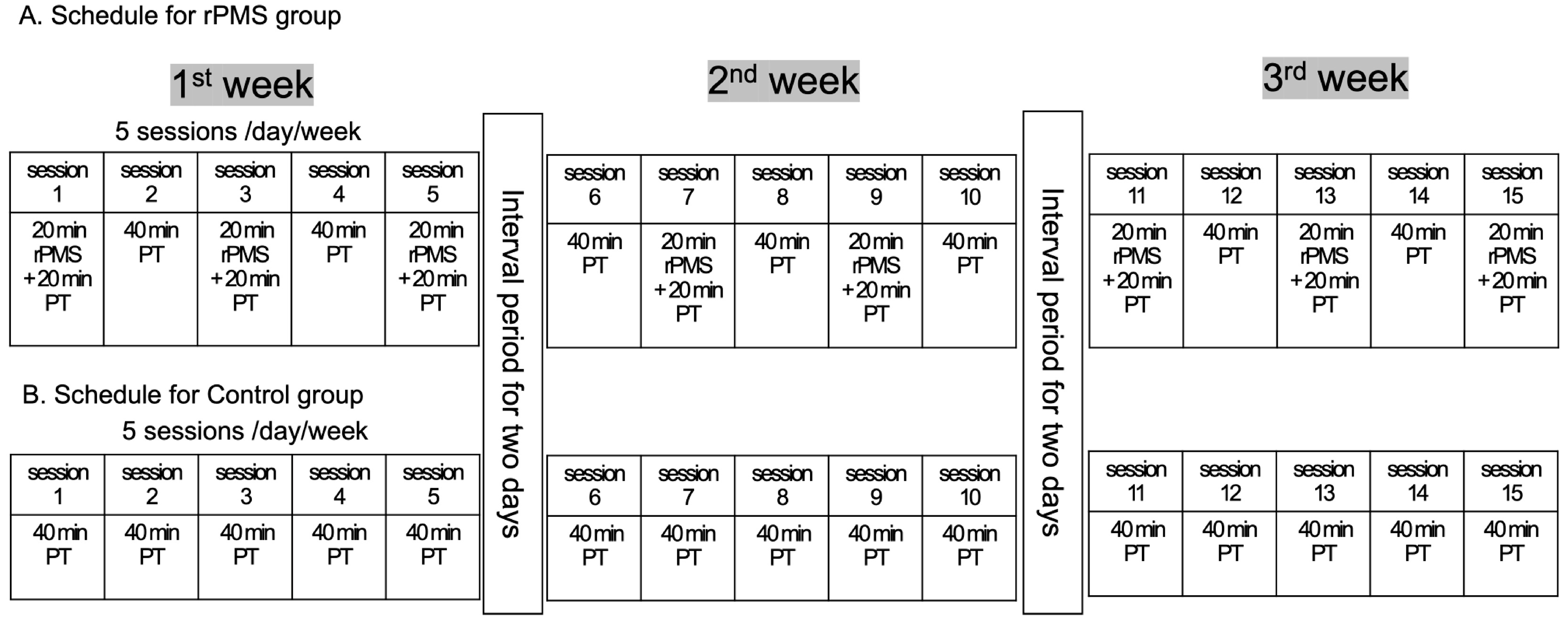

4.3. Intervention protocol

4.4. Outcome measures

4.5. Assessment of Proprioceptive function

4.6. Indices of corrected gains of UE motor recovery

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeannerod, M. The Neural and Behavioral Organization of Goal-Directed Movements. Oxford University Press. 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.A.L., T. Motor Control and Learning. 5th Edn. Champaign, IL.: Human Kinetics. 1988.

- Adamo, D.E.; Martin, B.J.; Brown, S.H. Age-related differences in upper limb proprioceptive acuity. Percept Mot Skills 2007, 104, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, L.M.; Matyas, T.A.; Oke, L.E. Sensory loss in stroke patients: effective training of tactile and proprioceptive discrimination. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993, 74, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, S.F.; Hanley, M.; Chillala, J.; Selley, A.B.; Tallis, R.C. Sensory loss in hospital-admitted people with stroke: characteristics, associated factors, and relationship with function. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2008, 22, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, L.A.; Lincoln, N.B.; Radford, K.A. Somatosensory impairment after stroke: frequency of different deficits and their recovery. Clin Rehabil 2008, 22, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, B.D.; Yiannikas, C. Functional prognosis in stroke: use of somatosensory evoked potentials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989, 52, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerfeld, D.K.; von Arbin, M.H. The impact of somatosensory function on activity performance and length of hospital stay in geriatric patients with stroke. Clin Rehabil 2004, 18, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, D. , Weiss, P.L., Gottlieb, D. Does Proprioceptive Loss Influence Recovery of the Upper Extremity After Stroke? Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair 1999, 13, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusoffsky, A.; Wadell, I.; Nilsson, B.Y. The relationship between sensory impairment and motor recovery in patients with hemiplegia. Scand J Rehabil Med 1982, 14, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weerdt, W.; Lincoln, N.B.; Harrison, M.A. Prediction of arm and hand function recovery in stroke patients. Int J Rehabil Res 1987, 10, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.T.; Langton-Hewer, R.; Wood, V.A.; Skilbeck, C.E.; Ismail, H.M. The hemiplegic arm after stroke: measurement and recovery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1983, 46, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayashi, S.; Takahashi, R. Repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation improves severe upper limb paresis in early acute phase stroke survivors. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayashi, S.; Saito, H. Neuromuscular Stimulation as an Intervention Tool for Recovery from Upper Limb Paresis after Stroke and the Neural Basis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayashi, S.; Takahashi, R.; Onuki, M. Upper limb recovery in early acute phase stroke survivors by coupled EMG-triggered and cyclic neuromuscular electrical stimulation. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 46, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, G.; Chae, J.; Chawla, H.; Kirshblum, S.; Zorowitz, R.; Lewis, G.; Pang, S. Electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation for improving the arm function of acute stroke survivors: a randomized pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998, 79, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Hai, H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.W. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Repetitive Peripheral Magnetic Stimulation applied in Early Subacute Stroke: Effects on Severe Upper-limb Impairment. Clin Rehabil 2022, 36, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, L.D.; Schneider, C. Effects of repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation on normal or impaired motor control. A review. Neurophysiol Clin 2013, 43, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goble, D.J.; Coxon, J.P.; Van Impe, A.; Geurts, M.; Van Hecke, W.; Sunaert, S.; Wenderoth, N.; Swinnen, S.P. The neural basis of central proprioceptive processing in older versus younger adults: an important sensory role for right putamen. Hum Brain Mapp 2012, 33, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisawa, Y. Morphological study of mechanoreceptors on the coracoacromial ligament. J Orthop Sci 1998, 3, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swash, M.; Fox, K.P. The effect of age on human skeletal muscle. Studies of the morphology and innervation of muscle spindles. J Neurol Sci 1972, 16, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Suzuki, S.; Kanda, K. Age-related physiological and morphological changes of muscle spindles in rats. J Physiol 2007, 582, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, C.D.; Johnsrude, I.S.; Ashburner, J.; Henson, R.N.; Friston, K.J.; Frackowiak, R.S. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage 2001, 14, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemann, U.; Ishii, K.; Borgheresi, A.; Yaseen, Z.; Battaglia, F.; Hallett, M.; Cincotta, M.; Wassermann, E.M. Dissociation of the pathways mediating ipsilateral and contralateral motor-evoked potentials in human hand and arm muscles. J Physiol 1999, 518 Pt 3, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Hosaki, A.; Hino, T.; Sato, M.; Komori, T.; Hirai, S.; Rossini, P.M. Motor cortical disinhibition in the unaffected hemisphere after unilateral cortical stroke. Brain 2002, 125, 1896–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, M.T.; Ben Assayag, E.; Shabashov-Stone, D.; Liraz-Zaltsman, S.; Mazzitelli, J.; Arenas, M.; Abduljawad, N.; Kliper, E.; Korczyn, A.D.; Thareja, N.S.; et al. CCR5 Is a Therapeutic Target for Recovery after Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell 2019, 176, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, K.; Fukutake, T.; Kawamura, M. 'Thumb localizing test' for detecting a lesion in the posterior column-medial lemniscal system. J Neurol Sci 1999, 167, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lou, T.; Shen, X. Correlation Between Proprioceptive Impairment and Motor Deficits After Stroke: A Meta-Analysis Review. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 688616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Kawakami, M.; Okuyama, K.; Ishii, R.; Oshima, O.; Hijikata, N.; Nakamura, T.; Oka, A.; Kondo, K.; Liu, M. Validity and Reliability of the Semmes-Weinstein Monofilament Test and the Thumb Localizing Test in Patients With Stroke. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 625917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C.M.; Tommasino, P.; Budhota, A.; Campolo, D. Upper extremity proprioception in healthy aging and stroke populations, and the effects of therapist- and robot-based rehabilitation therapies on proprioceptive function. Front Hum Neurosci 2015, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winward, C.E.; Halligan, P.W.; Wade, D.T. The Rivermead Assessment of Somatosensory Performance (RASP): standardization and reliability data. Clin Rehabil 2002, 16, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krewer, C.; Hartl, S.; Muller, F.; Koenig, E. Effects of repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation on upper-limb spasticity and impairment in patients with spastic hemiparesis: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014, 95, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldmann, B.; Kerkhoff, G.; Struppler, A.; Havel, P.; Jahn, T. Repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation alleviates tactile extinction. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 3193–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamand, V.H.; Schneider, C. Noninvasive and painless magnetic stimulation of nerves improved brain motor function and mobility in a cerebral palsy case. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014, 95, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struppler, A.; Binkofski, F.; Angerer, B.; Bernhardt, M.; Spiegel, S.; Drzezga, A.; Bartenstein, P. A fronto-parietal network is mediating improvement of motor function related to repetitive peripheral magnetic stimulation: A PET-H2O15 study. Neuroimage 2007, 36 Suppl 2, T174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.C. Techniques and mechanisms of action of transcranial stimulation of the human motor cortex. J Neurosci Methods 1997, 74, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amassian, V.E.; Stewart, M.; Quirk, G.J.; Rosenthal, J.L. Physiological basis of motor effects of a transient stimulus to cerebral cortex. Neurosurgery 1987, 20, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volz, L.J.; Hamada, M.; Rothwell, J.C.; Grefkes, C. What Makes the Muscle Twitch: Motor System Connectivity and TMS-Induced Activity. Cereb Cortex 2015, 25, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudo, R.J.; Wise, B.M.; SiFuentes, F.; Milliken, G.W. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science 1996, 272, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R. Connectivity-based approaches in stroke and recovery of function. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Obayashi, S.; Tsujiuchi, K.; Muraoka, Y. The effects of electromyography-controlled functional electrical stimulation on upper extremity function and cortical perfusion in stroke patients. Clin Neurophysiol 2013, 124, 2008–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickenstorfer, A.; Kleiser, R.; Keller, T.; Keisker, B.; Meyer, M.; Riener, R.; Kollias, S. Cortical and subcortical correlates of functional electrical stimulation of wrist extensor and flexor muscles revealed by fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 2009, 30, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.L.; Catlin, P.A.; Ellis, M.; Archer, A.L.; Morgan, B.; Piacentino, A. Assessing Wolf motor function test as outcome measure for research in patients after stroke. Stroke 2001, 32, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugl-Meyer, A.R.; Jaasko, L.; Leyman, I.; Olsson, S.; Steglind, S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med 1975, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, R.J.; Garraway, W.M.; Akhtar, A.J. Predicting functional outcome following acute stroke using a standard clinical examination. Stroke 1982, 13, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).