Submitted:

27 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

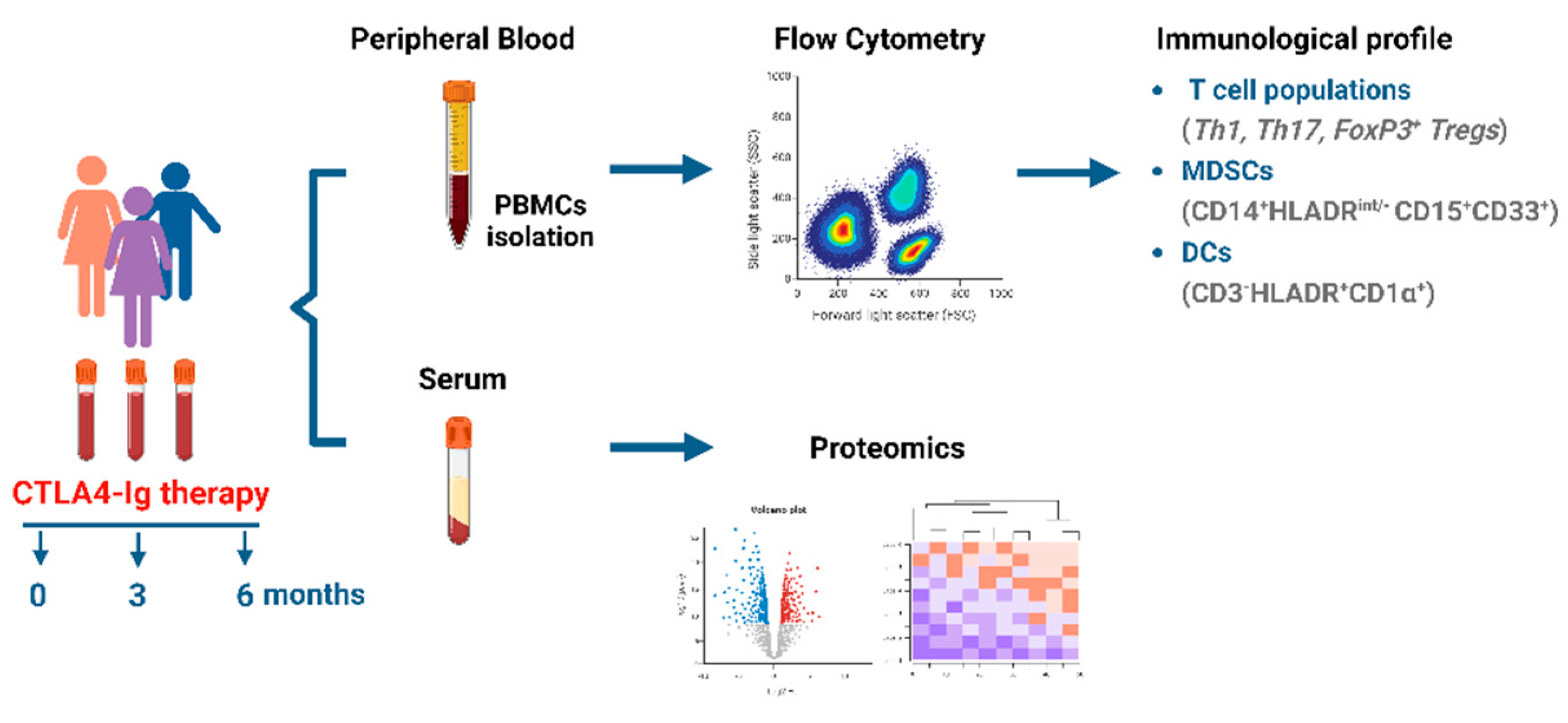

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study approval

2.2. Human subjects

2.3. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolation

2.4. Antibodies

2.5. Flow cytometry

2.6. Cellular Cytokine Expression Assays

2.7. Sample preparation and Proteomics analysis

2.8. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ characteristics at baseline and effect of treatment

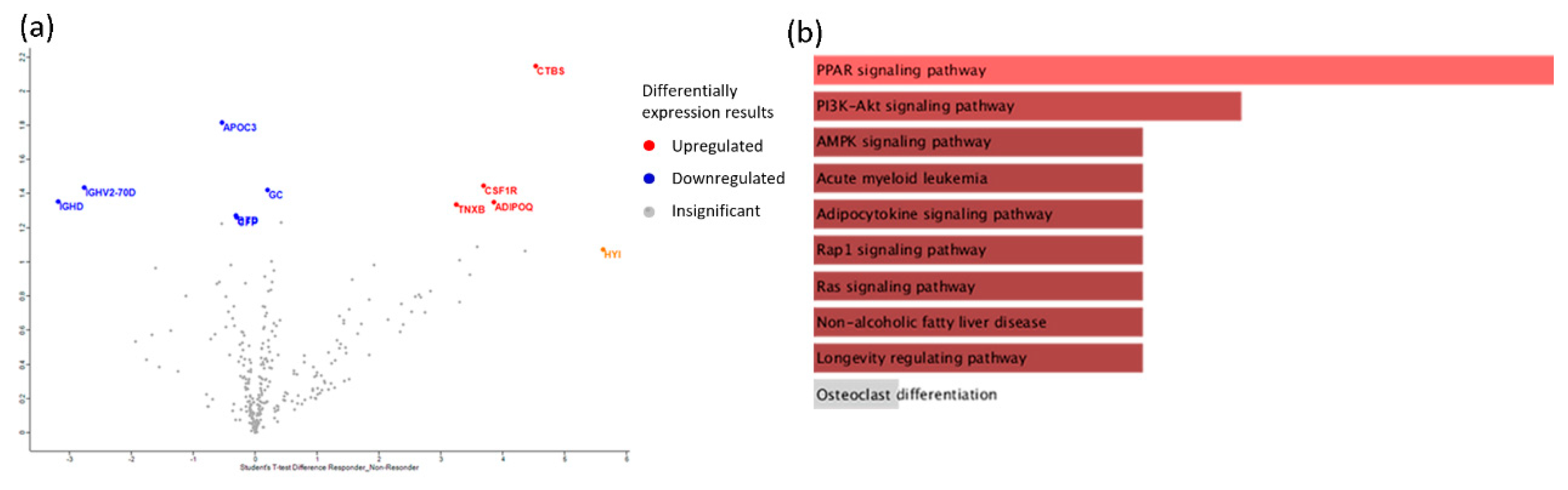

3.2. High disease activity of RA is reflected in serum proteome

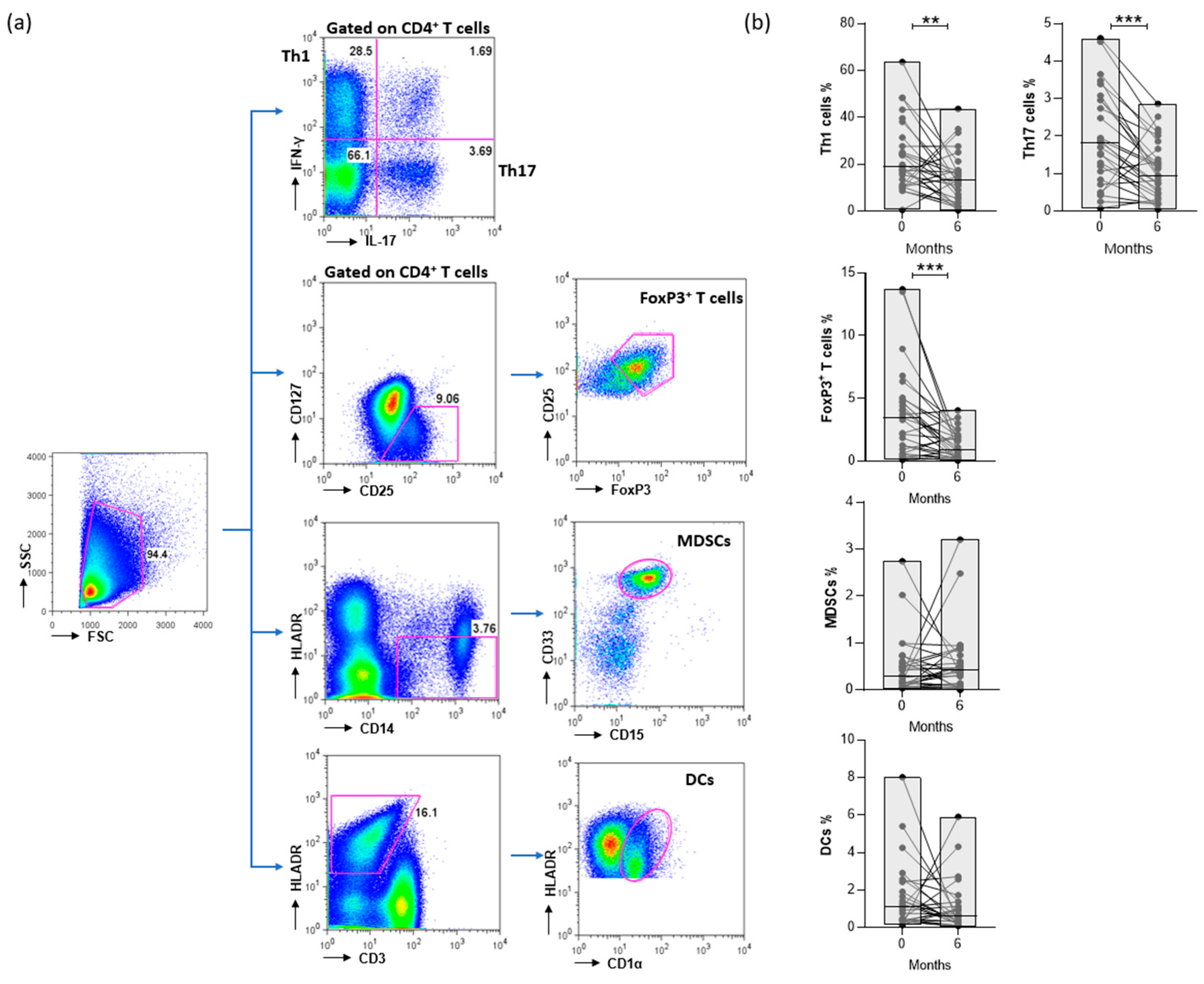

3.3. CTLA4-Ig decreases the levels of CD4+ T cells in RA patients

3.4. Disease activity is positively correlated with the proportion of CD4+ T cell subsets

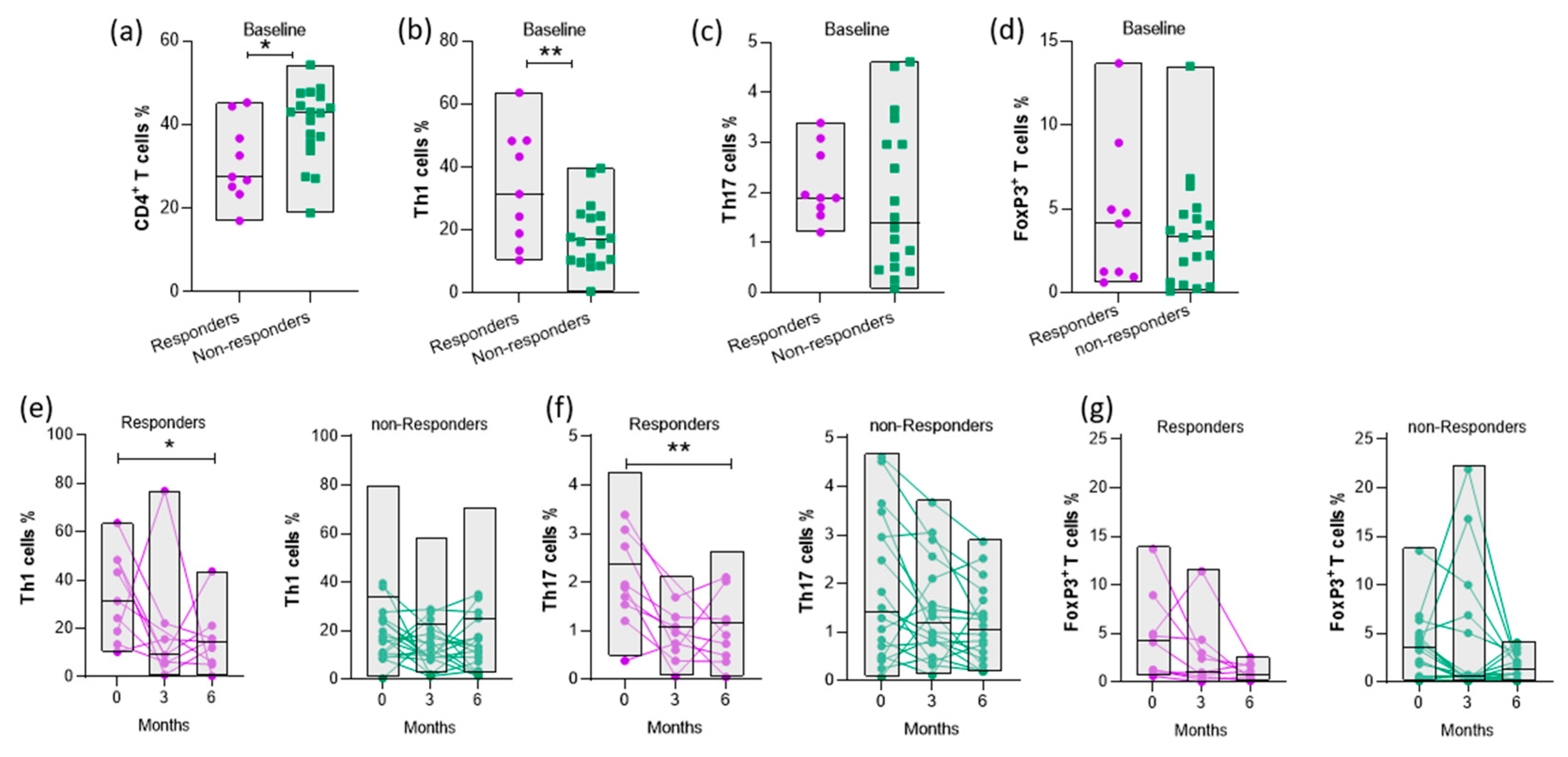

3.5. Increased baseline levels of Th1 cells are associated with response to abatacept therapy

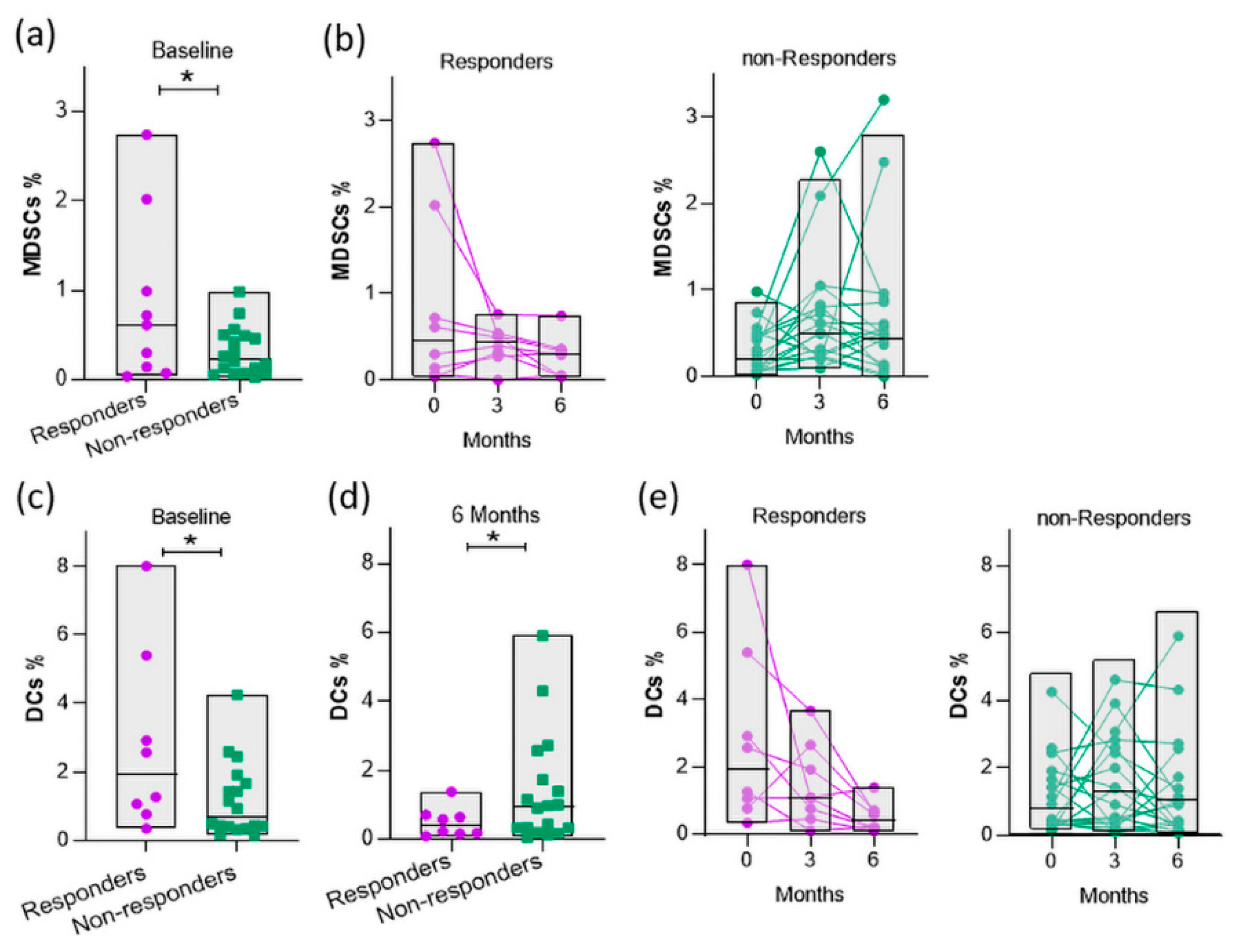

3.6. Baseline myeloid cells are elevated in responders

3.7. Inflammatory mediators are present in serum of responders before therapy initiation

3.8. A composite cellular and proteomic index predicts response to abatacept

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- B. McInnes and G. Schett, “The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 365, no. 23, pp. 2205–2219, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [CrossRef]

- F. Wolfe et al., “The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 481–494, Dec. 1994, doi: 10.1002/art.1780370408. [CrossRef]

- B. McInnes and G. Schett, “Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis,” The Lancet, vol. 389, no. 10086, pp. 2328–2337, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31472-1. [CrossRef]

- T. Namekawa, U. G. Wagner, J. J. Goronzy, and C. M. Weyand, “Functional subsets of CD4 T cells in rheumatoid synovitis,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 41, no. 12, pp. 2108–2116, Dec. 1998, doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2108::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [CrossRef]

- M. Gizinski and D. A. Fox, “T cell subsets and their role in the pathogenesis of rheumatic disease,” Curr Opin Rheumatol, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 204–210, Mar. 2014, doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000036. [CrossRef]

- F. Behrens et al., “Imbalance in distribution of functional autologous regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 1151–1156, Mar. 2007, doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068320. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Carreno and M. Collins, “The B7 Family of Ligands and Its Receptors: New Pathways for Costimulation and Inhibition of Immune Responses,” Annu Rev Immunol, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 29–53, Apr. 2002, doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091101.091806. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Walunas, C. Y. Bakker, and J. A. Bluestone, “CTLA-4 ligation blocks CD28-dependent T cell activation.,” J Exp Med, vol. 183, no. 6, pp. 2541–50, Jun. 1996, doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2541. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Tivol, F. Borriello, A. N. Schweitzer, W. P. Lynch, J. A. Bluestone, and A. H. Sharpe, “Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4,” Immunity, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 541–547, Nov. 1995, doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Linsley, W. Brady, M. Urnes, L. S. Grosmaire, N. K. Damle, and J. A. Ledbetter, “CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7.,” J Exp Med, vol. 174, no. 3, pp. 561–569, Sep. 1991, doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [CrossRef]

- K. Wing et al., “CTLA-4 Control over Foxp3 + Regulatory T Cell Function,” Science (1979), vol. 322, no. 5899, pp. 271–275, Oct. 2008, doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Walunas and J. A. Bluestone, “CTLA-4 regulates tolerance induction and T cell differentiation in vivo.,” J Immunol, vol. 160, no. 8, pp. 3855–60, Apr. 1998. [CrossRef]

- G. Ozen, S. Pedro, R. Schumacher, T. A. Simon, and K. Michaud, “Safety of abatacept compared with other biologic and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: data from an observational study,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 141, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1921-z. [CrossRef]

- J. Bathon et al., “Sustained disease remission and inhibition of radiographic progression in methotrexate-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors treated with abatacept: 2-year outcomes,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 70, no. 11, pp. 1949–1956, Nov. 2011, doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.145268. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Smolen et al., “EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 685–699, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655. [CrossRef]

- Flouri et al., “Comparative effectiveness and survival of infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept for rheumatoid arthritis patients in the Hellenic Registry of Biologics: Low rates of remission and 5-year drug survival,” Semin Arthritis Rheum, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 447–457, Feb. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.07.011. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Hetland et al., “Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: Results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 22–32, Jan. 2010, doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [CrossRef]

- Mulhearn, Barton, and Viatte, “Using the Immunophenotype to Predict Response to Biologic Drugs in Rheumatoid Arthritis,” J Pers Med, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 46, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.3390/jpm9040046. [CrossRef]

- F. C. Arnett et al., “The american rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 315–324, Mar. 1988, doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Wiśniewski, “Filter-Aided Sample Preparation for Proteome Analysis,” 2018, pp. 3–10. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8695-8_1. [CrossRef]

- Y. Perez-Riverol et al., “The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 50, no. D1, pp. D543–D552, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1038. [CrossRef]

- M. Jiao et al., “Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activation attenuates the inflammatory response to protect the liver from acute failure by promoting the autophagy pathway,” Cell Death Dis, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. e1397–e1397, Aug. 2014, doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.361. [CrossRef]

- S. Xie, M. Chen, B. Yan, X. He, X. Chen, and D. Li, “Identification of a Role for the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Innate Immune Cells,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 4, p. e94496, Apr. 2014, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094496. [CrossRef]

- K. Katagiri, M. Hattori, N. Minato, S. Irie, K. Takatsu, and T. Kinashi, “Rap1 Is a Potent Activation Signal for Leukocyte Function-Associated Antigen 1 Distinct from Protein Kinase C and Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH Kinase,” Mol Cell Biol, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 1956–1969, Mar. 2000, doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.6.1956-1969.2000. [CrossRef]

- R. J. E. M. Dolhain, A. N. van der Heiden, N. T. ter Haar, F. C. Breedveld, and A. M. M. Miltenburg, “Shift toward T lymphocytes with a T helper 1 cytokine-secretion profile in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 1961–1969, Dec. 1996, doi: 10.1002/art.1780391204. [CrossRef]

- B. Berner, D. Akça, T. Jung, G. A. Muller, and M. A. Reuss-Borst, “Analysis of Th1 and Th2 cytokines expressing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in rheumatoid arthritis by flow cytometry.,” J Rheumatol, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 1128–35, May 2000.

- M. J. Lewis et al., “Molecular Portraits of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Identify Clinical and Treatment Response Phenotypes,” Cell Rep, vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 2455-2470.e5, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.091. [CrossRef]

- E. Lubberts, M. I. Koenders, and W. B. van den Berg, “ The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models.,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 29, 2005, doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Murphy et al., “Divergent Pro- and Antiinflammatory Roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in Joint Autoimmune Inflammation,” J Exp Med, vol. 198, no. 12, pp. 1951–1957, Dec. 2003, doi: 10.1084/jem.20030896. [CrossRef]

- M. Ziolkowska et al., “High Levels of IL-17 in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: IL-15 Triggers In Vitro IL-17 Production Via Cyclosporin A-Sensitive Mechanism,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 164, no. 5, pp. 2832–2838, Mar. 2000, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2832. [CrossRef]

- W. Yokoyama-Kokuryo et al., “Identification of molecules associated with response to abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 46, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-2137-y. [CrossRef]

- J. Inamo, Y. Kaneko, J. Kikuchi, and T. Takeuchi, “High serum IgA and activated Th17 and Treg predict the efficacy of abatacept in patients with early, seropositive rheumatoid arthritis,” Clin Rheumatol, vol. 40, no. 9, pp. 3615–3626, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05602-0. [CrossRef]

- M. SCARSI, T. ZIGLIOLI, and P. AIRÒ, “Decreased Circulating CD28-negative T Cells in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Abatacept Are Correlated with Clinical Response,” J Rheumatol, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 911–916, May 2010, doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091176. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Navashenaq et al., “The role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in rheumatoid arthritis: An update,” Life Sci, vol. 269, p. 119083, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119083. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are proinflammatory and regulate collagen-induced arthritis through manipulating Th17 cell differentiation,” Clinical Immunology, vol. 157, no. 2, pp. 175–186, Apr. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.02.001. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang et al., “Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to bone erosion in collagen-induced arthritis by differentiating to osteoclasts,” J Autoimmun, vol. 65, pp. 82–89, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.010. [CrossRef]

- C. Guo et al., “Myeloid-derived suppressor cells have a proinflammatory role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 278–285, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205508. [CrossRef]

- W. Fujii et al., “Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Play Crucial Roles in the Regulation of Mouse Collagen-Induced Arthritis,” The Journal of Immunology, vol. 191, no. 3, pp. 1073–1081, Aug. 2013, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203535. [CrossRef]

- M.-J. Park et al., “Interleukin-10 produced by myeloid-derived suppressor cells is critical for the induction of Tregs and attenuation of rheumatoid inflammation in mice,” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 3753, Feb. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21856-2. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Walter et al., “Interaction with activated monocytes enhances cytokine expression and suppressive activity of human CD4+CD45ro+CD25+CD127 low regulatory T cells,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 627–638, Mar. 2013, doi: 10.1002/art.37832. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, D. Zhu, T. Wang, X. Xia, J. Tian, and S. Wang, “Roles of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Subpopulations in Autoimmune Arthritis,” Front Immunol, vol. 9, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02849. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhu et al., “The Expansion of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Is Associated with Joint Inflammation in Rheumatic Patients with Arthritis,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2018, pp. 1–12, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1155/2018/5474828. [CrossRef]

- J. Kurkó et al., “Identification of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study,” BMC Musculoskelet Disord, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 281, Dec. 2014, doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-281. [CrossRef]

- C. PREVOSTO, J. C. GOODALL, and J. S. HILL GASTON, “Cytokine Secretion by Pathogen Recognition Receptor-stimulated Dendritic Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis,” J Rheumatol, vol. 39, no. 10, pp. 1918–1928, Oct. 2012, doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120208. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Lebre, S. L. Jongbloed, S. W. Tas, T. J. M. Smeets, I. B. McInnes, and P. P. Tak, “Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovium Contains Two Subsets of CD83−DC-LAMP− Dendritic Cells with Distinct Cytokine Profiles,” Am J Pathol, vol. 172, no. 4, pp. 940–950, Apr. 2008, doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070703. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Moret et al., “Intra-articular CD1c-expressing myeloid dendritic cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients express a unique set of T cell-attracting chemokines and spontaneously induce Th1, Th17 and Th2 cell activity,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 15, no. 5, p. R155, 2013, doi: 10.1186/ar4338. [CrossRef]

- H. Benham et al., “Citrullinated peptide dendritic cell immunotherapy in HLA risk genotype–positive rheumatoid arthritis patients,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 7, no. 290, Jun. 2015, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa9301. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Bell et al., “Autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells for rheumatoid and inflammatory arthritis,” Ann Rheum Dis, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 227–234, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208456. [CrossRef]

- S. Qureshi et al., “Trans-Endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: A Molecular Basis for the Cell-Extrinsic Function of CTLA-4,” Science (1979), vol. 332, no. 6029, pp. 600–603, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.1126/science.1202947. [CrossRef]

- U. Grohmann et al., “CTLA-4–Ig regulates tryptophan catabolism in vivo,” Nat Immunol, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 1097–1101, Nov. 2002, doi: 10.1038/ni846. [CrossRef]

- S. Garcia et al., “Colony-stimulating factor (CSF) 1 receptor blockade reduces inflammation in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 18, no. 1, p. 75, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0973-6. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu et al., “Imatinib inhibits CSF1R that stimulates proliferation of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes,” Clin Exp Immunol, vol. 195, no. 2, pp. 237–250, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1111/cei.13220. [CrossRef]

- K. Szumilas, P. Szumilas, S. Słuczanowska-Głąbowska, K. Zgutka, and A. Pawlik, “Role of Adiponectin in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 21, no. 21, p. 8265, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.3390/ijms21218265. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Lee and S. Bae, “Circulating adiponectin and visfatin levels in rheumatoid arthritis and their correlation with disease activity: A meta-analysis,” Int J Rheum Dis, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 664–672, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13038. [CrossRef]

- T. F. Li et al., “Distribution of tenascin-X in different synovial samples and synovial membrane-like interface tissue from aseptic loosening of total hip replacement,” Rheumatol Int, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 177–183, Jul. 2000, doi: 10.1007/s002960000044. [CrossRef]

- M. Yanagida et al., “Serum Proteome Analysis in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Receiving Therapy with Tocilizumab: An Anti-Interleukin-6 Receptor Antibody,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2013, pp. 1–9, 2013, doi: 10.1155/2013/607137. [CrossRef]

- C. Martín-González et al., “Apolipoprotein C-III is linked to the insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction that are present in rheumatoid arthritis,” Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 126, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1186/s13075-022-02822-w. [CrossRef]

- U. Hardt, M. M. Corcoran, S. Narang, V. Malmström, L. Padyukov, and G. B. Karlsson Hedestam, “Analysis of IGH allele content in a sample group of rheumatoid arthritis patients demonstrates unrevealed population heterogeneity,” Front Immunol, vol. 14, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1073414. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang and T.-Y. Lee, “Revealing the Immune Heterogeneity between Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Rheumatoid Arthritis Based on Multi-Omics Data Analysis,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 9, p. 5166, May 2022, doi: 10.3390/ijms23095166. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kimura, L. Zhou, T. Miwa, and W.-C. Song, “Genetic and therapeutic targeting of properdin in mice prevents complement-mediated tissue injury,” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 120, no. 10, pp. 3545–3554, Oct. 2010, doi: 10.1172/JCI41782. [CrossRef]

| All | Responders | Non-responders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 29 | 10 | 19 |

| Gender (% females) | 25 (86.2%) | 7 (70.0%) | 18 (94.7%) |

| Age,Median (min,max;IQR) | 64 (32,77;17) | 58 (32,71;20) | 67 (40,77;18) |

| Disease duration,Median (min,max;IQR) | 23 (3,240;45) | 32.5 (8,120;50) | 22 (3,240;40) |

| R.F. positive (%) | 8 (27.6%) | 2 (20.0%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| Anti-CCP positive (%) | 15 (51.7%) | 5 (50.0%) | 10 (52.6%) |

| Methotrexate (%) | 26 (89.65%) | 9 (90%) | 17 (89.47%) |

| Steroids (%) | 10 (34.48%) | 4 (40%) | 6 (31.57%) |

| Disease characteristics before abatacept therapy (Baseline) | |||

| ESR,Median (min,max;IQR) | 26 (4,77;34) | 25.5 (4,69;34) | 27 (4,77;40) |

| CRP,Median (min,max;IQR) | 0.33 (0.24,6.03;0.53) | 0,52 (0.31,3.61;0.70) | 0.33 (0.24,6.03;0.53) |

| Swollen 28,Median (min,max;IQR) | 6 (2,18;5) | 9 (3,15;5) | 6 (2,18;4) |

| Tender 28,Median (min,max;IQR) | 7 (0,23;6) | 9 (2,23;8) | 6 (0,20;6) |

| VAS global,Median (min,max;IQR) | 70 (40,100;20) | 70 (40,100;60) | 60 (40,100;20) |

| DAS28-ESR,Median (min,max;IQR) | 5.48 (3.42,6.85; 1.90) | 5.91 (3.42,6.79;1.89) | 4.63 (3.94,6.85;1.89) |

| Disease characteristics after abatacept therapy (6 months) | |||

| ESR,Median (min,max;IQR) | 28 (6,68,21) | 24.5 (8,68;22) | 31 (6,59;18) |

| CRP,Median (min,max;IQR) | 0.36 (0.10,3.01;0.27) | 0.36 (0.10,1.45;0.18) | 0.36 (0.30,3.01;0.30) |

| Swollen 28,Median (min,max;IQR) | 4 (0,17;6) | 1.5 (0,2;2) | 6 (3,17;8) |

| Tender 28,Median (min,max;IQR) | 2 (0,27;6) | 1 (0,4;2) | 3 (0,27;9) |

| VAS global,Median (min,max;IQR) | 30 (0,100;35) | 30 (0,60;23) | 40 (10,100;50) |

| DAS28-ESR,Median (min,max;IQR) | 4.20 (2.22,8.04;2.13) | 2.93 (2.22,4.61;1.80) | 4.67 (2.85,8.04;2.05) |

| ΔDAS28,Median (min,max;IQR) | 1.30 (-1.84, 4.30; 2.61) | 2.42 (0.16, 4.30;2.48) | 0.48 (-1.84,3.44;2.76) |

| All values are medians (IQR) unless otherwise specified. R.F.: Rheumatoid Factor; anti-CCP: Anti-cyclic Citrullinated Peptide; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; DAS28: Disease activity score using 28 joints | |||

| TH1 % | TH17 % | FoxP3 % | MDSCs % | DCs % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Seropositive | |||||

| No | 27.9 (13.4) | 2.32 (1.43) | 4.58 (4.40) | 0.25 (0.22) | 1.18 (1.19) |

| Yes | 18.8 (15.8) | 1.62 (1.08) | 3.05 (2.43) | 0.77 (0.20) | 2.07 (2.21) |

| P-value | 0.120 | 0.167 | 0.273 | 0.050 | 0.224 |

| ESR (P-value) | -0.237 (0.233) | 0.028 (0.890) | -0.190 (0.343) | -0.143 (0.476) | -0.202 (0.321) |

| CRP (P-value) | 0.083 (0.681) | -0.087 (0.271) | -0.125 (0.535) | 0.261 (0.188) | 0.081 (0.692) |

| Swollen 28 (P-value) | 0.346 (0.077) | -0.220 (0.271) | -0.051 (0.799) | -0.151 (0.452) | -0.124 (0.547) |

| Tender 28 (P-value) | 0.386* (0.047) | 0.173 (0.389) | 0.440* (0.022) | -0.348 (0.075) | -0.133 (0.518) |

| VAS global (P-value) | -0.102 (0.614) | 0.097 (0.631) | 0.085 (0.674) | -0.274 (0.167) | -0.271 (0.180) |

| DAS28-ESR (P-value) | 0.184 (0.359) | 0.195 (0.329) | 0.272 (0.169) | -0.363 (0.063) | -0.204 (0.317) |

| Independent samples T-test (comparison of means) was performed on the upper part of the table and Spearman's correlation coefficient on the lower part. *Significant associations | |||||

| Protein Name | Ratio Responders/ non-Responders | P-value | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSF1R (Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor) | 2,21997 | 1,4471 | Biological regulation; cell differentiation |

| GC (Vitamin D-binding protein) | 2,19503 | 1,42407 | Lipid metabolic process |

| ADIPOQ (Adiponectin) | 2,11482 | 1,35079 | Adiponectin-mediated signaling pathway |

| TNXB (Tenascin-X) | 2,09943 | 1,33687 | Actin cytoskeleton organization |

| CTBS (Chitobiase, Di-N-Acetyl-) | 2,93148 | 2,14787 | Amine metabolic process |

| APOC3 (Apolipoprotein C-III) | -2,60697 | 1,81868 | Acylglycerol metabolic process |

| IGHV2-70D (Immunoglobulin heavy variable 2-70D) | -2,20792 | 1,43596 | Immune response |

| IGHD (Immunoglobulin heavy constant delta) | -2,11844 | 1,35407 | Immune response |

| BTD (Biotinidase) | -2,02902 | 1,27382 | Metabolic process |

| CFP (Complement factor properdin) | -2,01735 | 1,26348 | Activation of immune response |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).