Submitted:

28 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

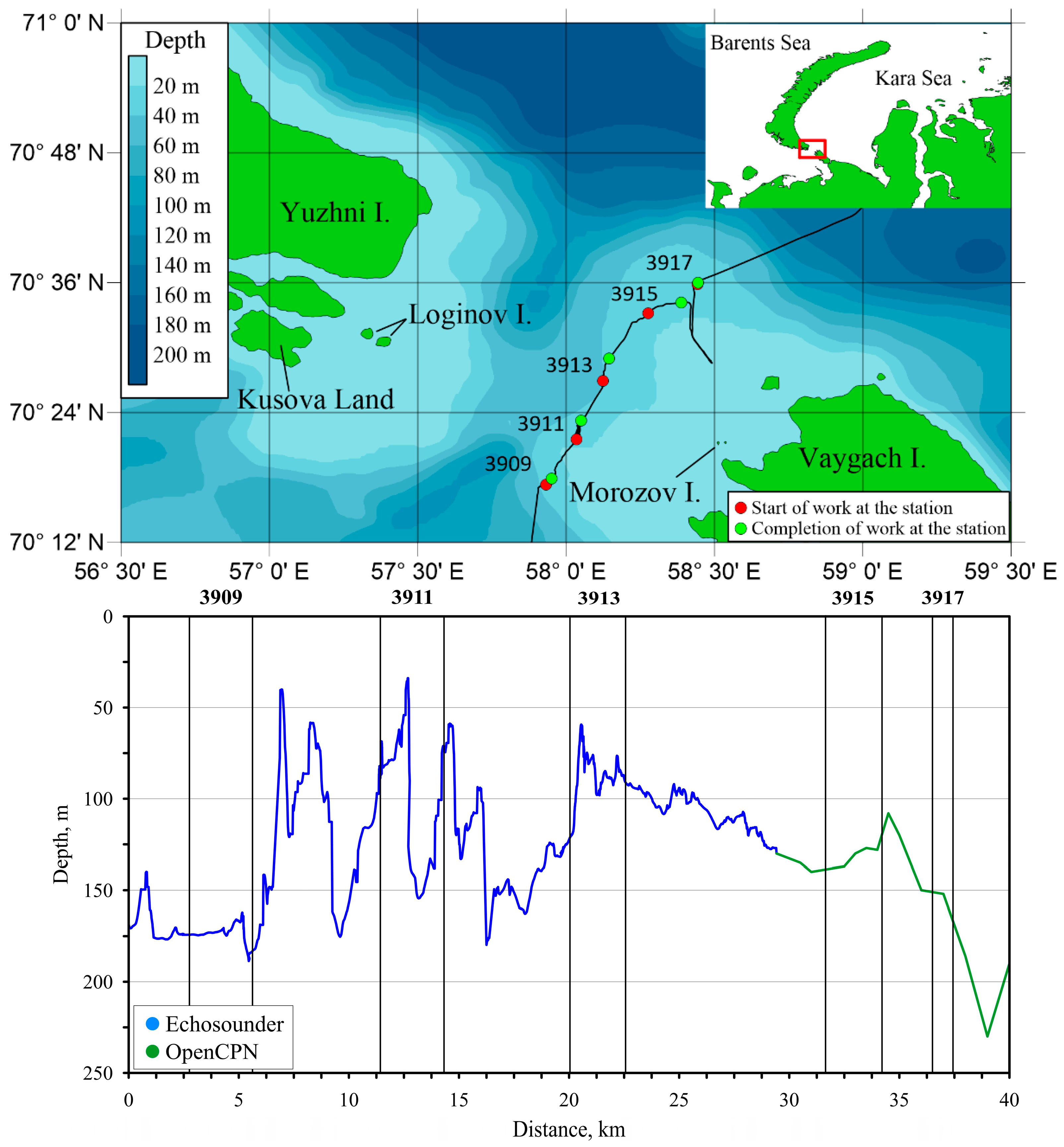

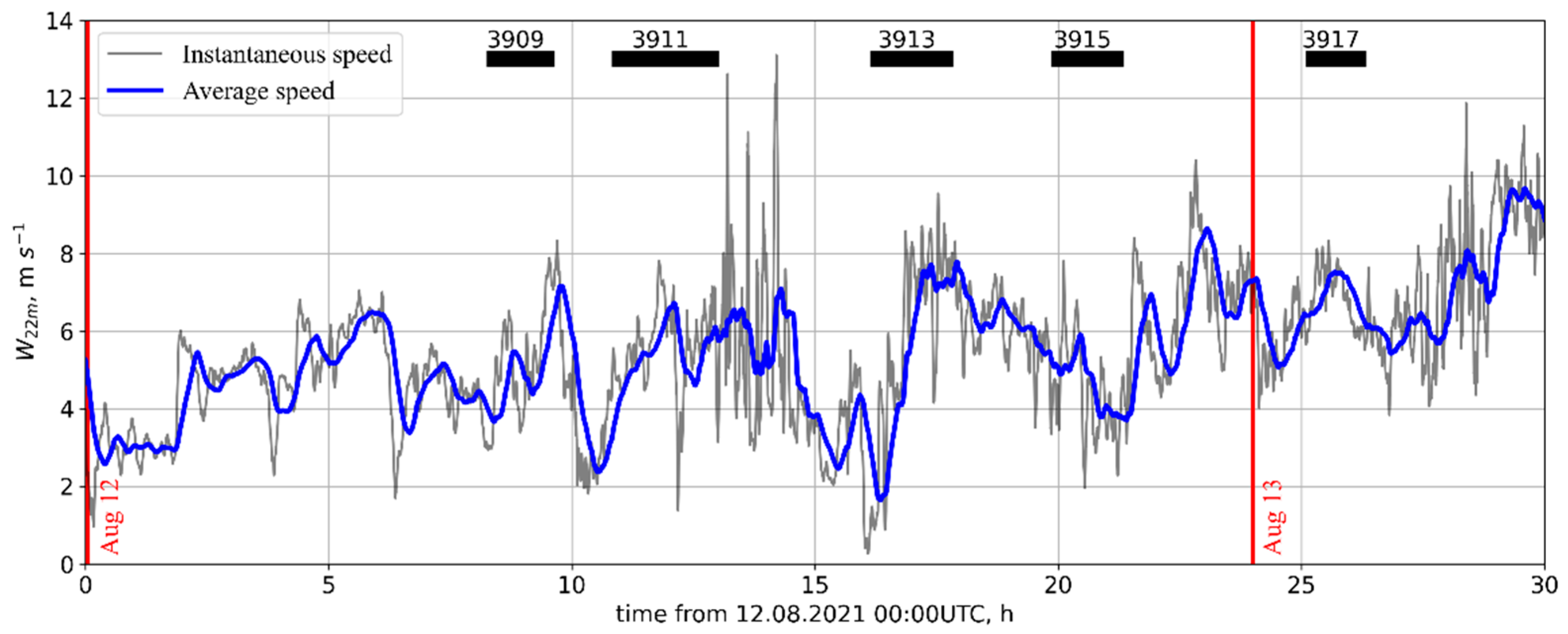

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

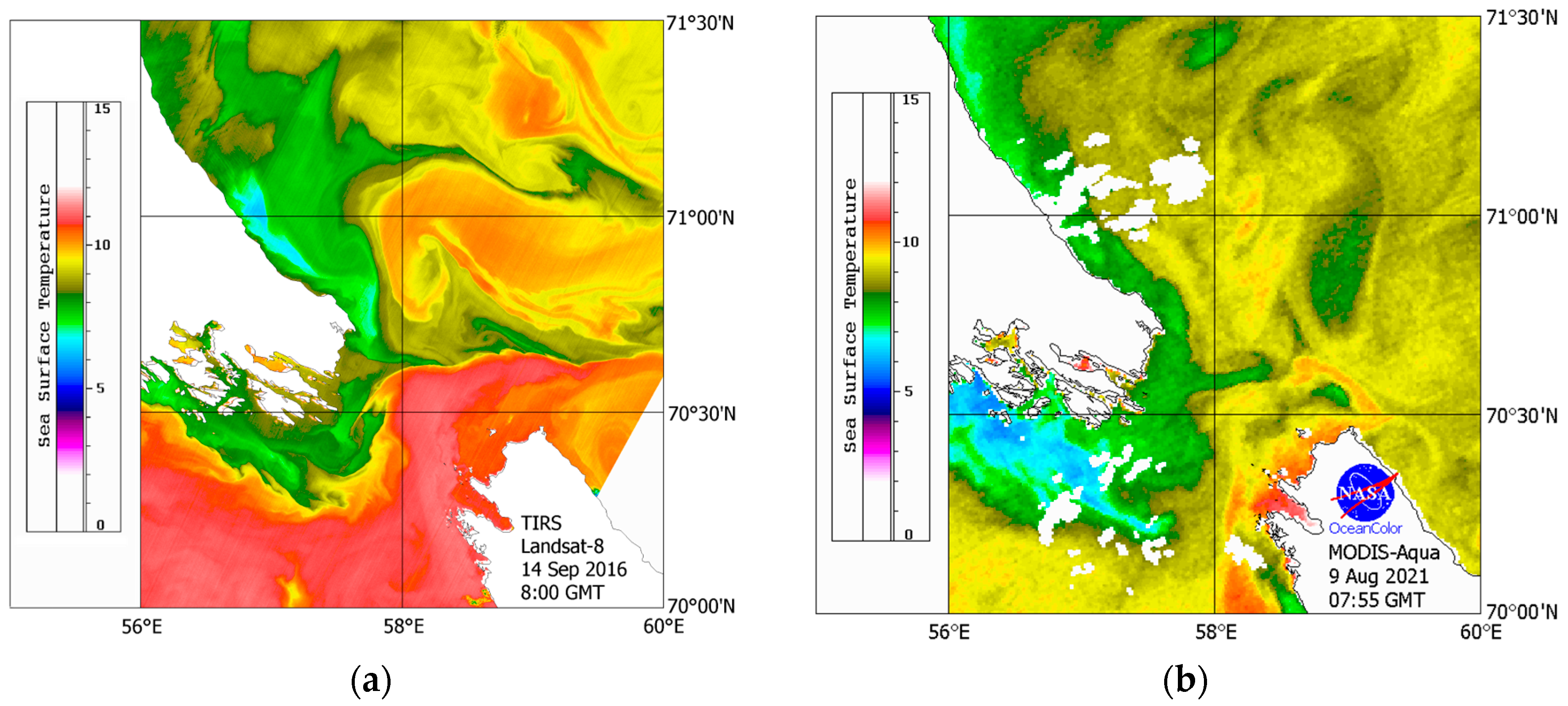

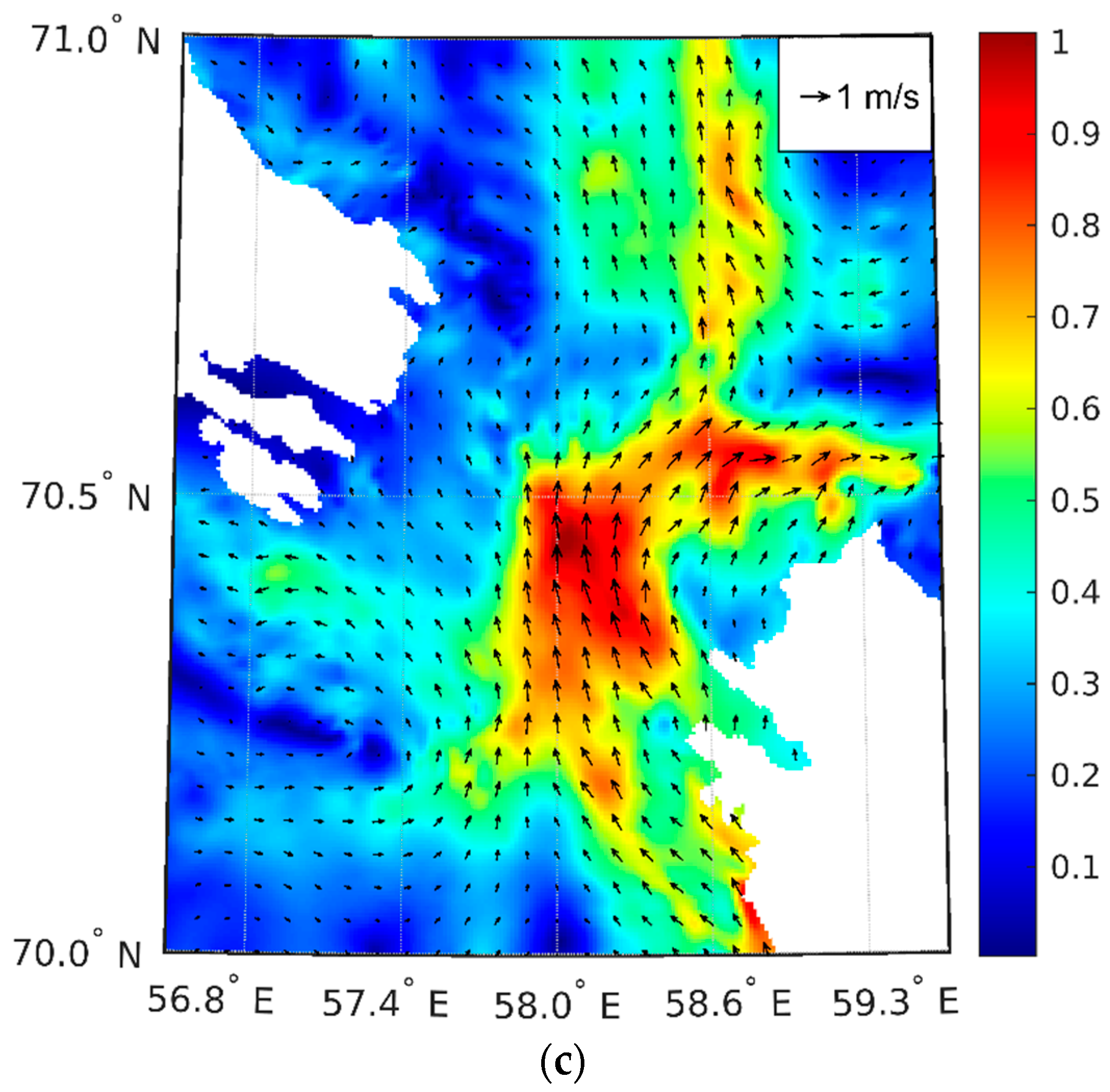

3.1. Background Conditions in the Kara Gates

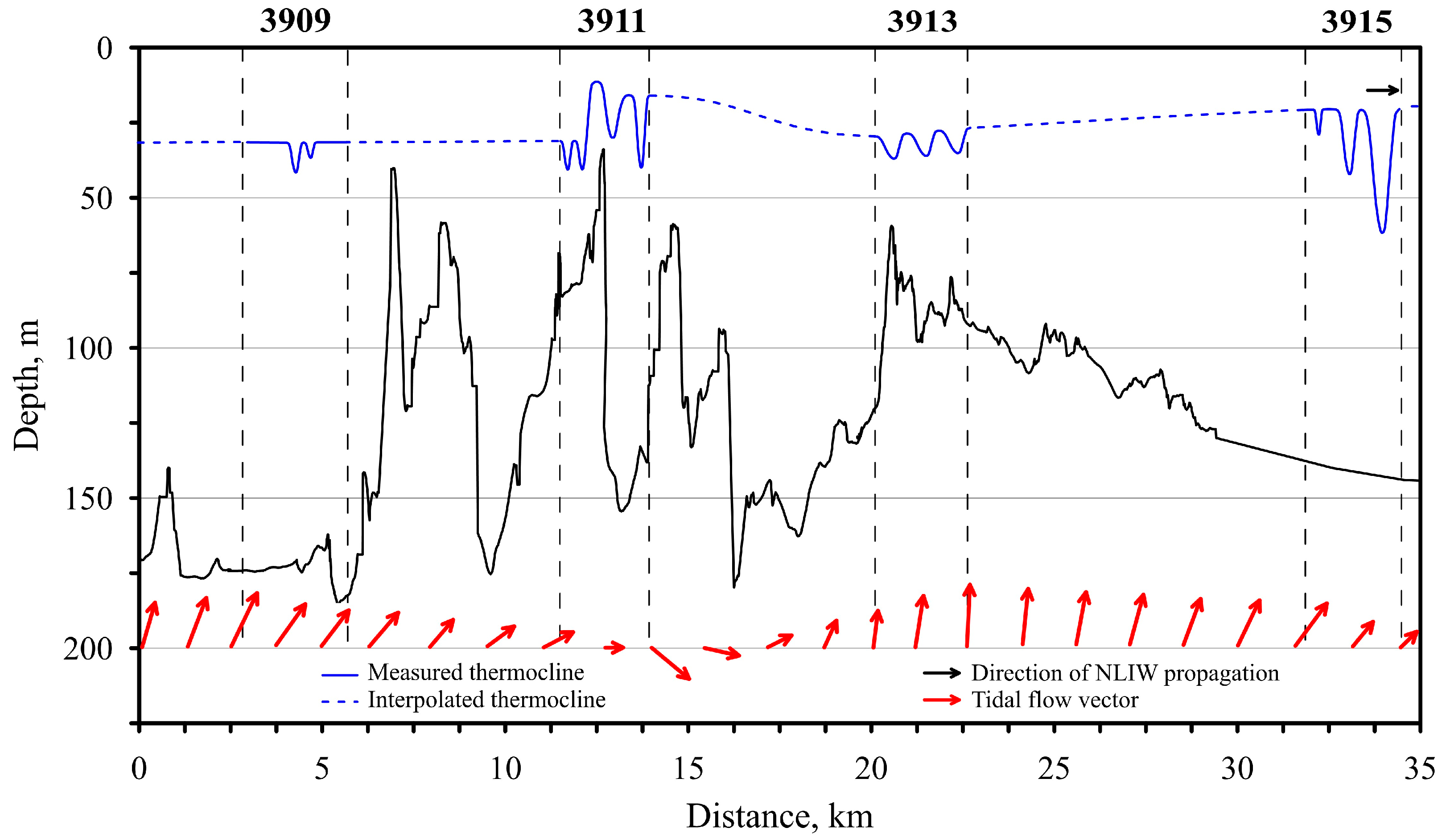

Tidal Conditions

Surface Signatures of NLIWs in Satellite Data

3.2. Vertical Thermohaline Measurements at Stations

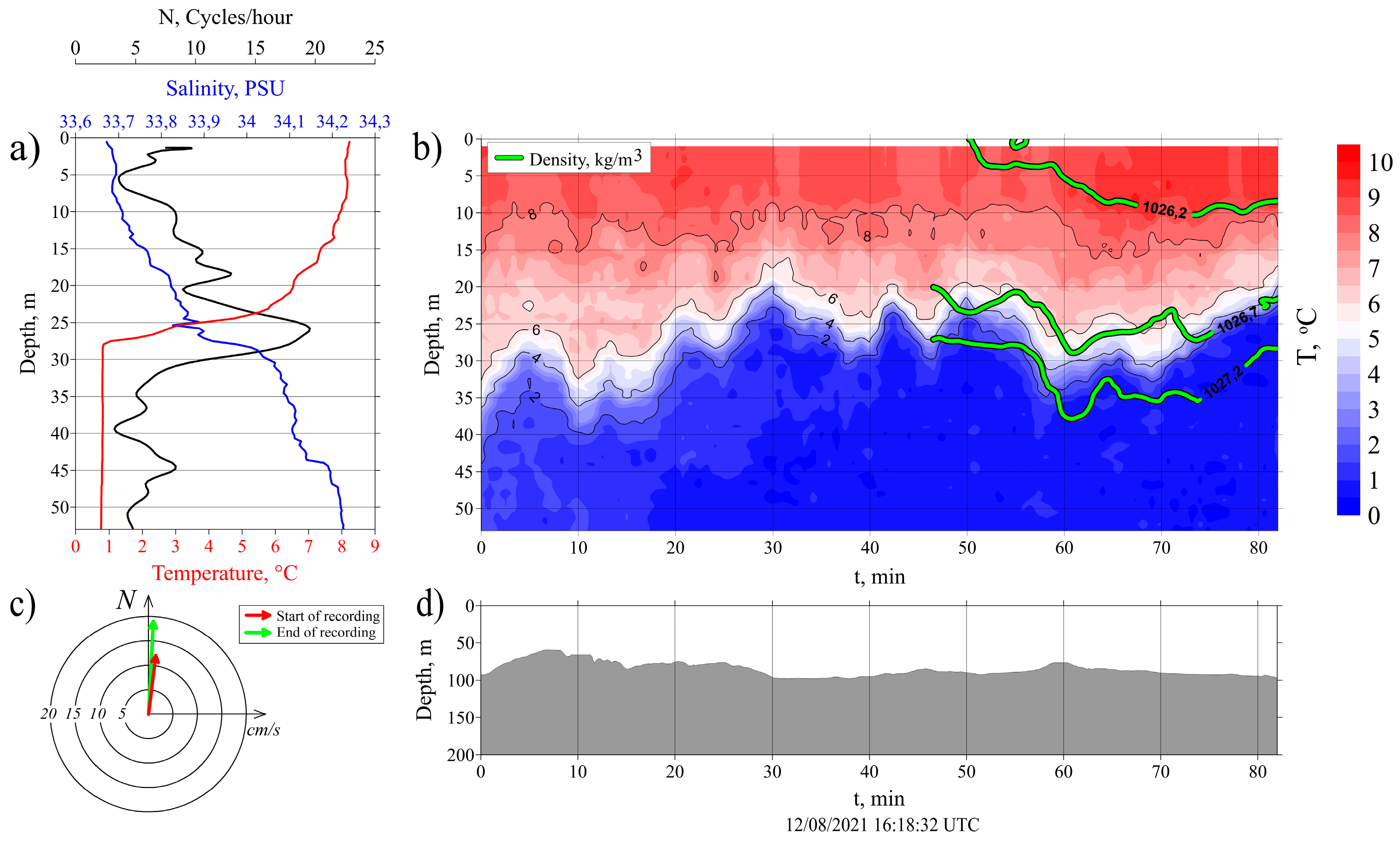

Station #3909

Station #3911

Station #3913

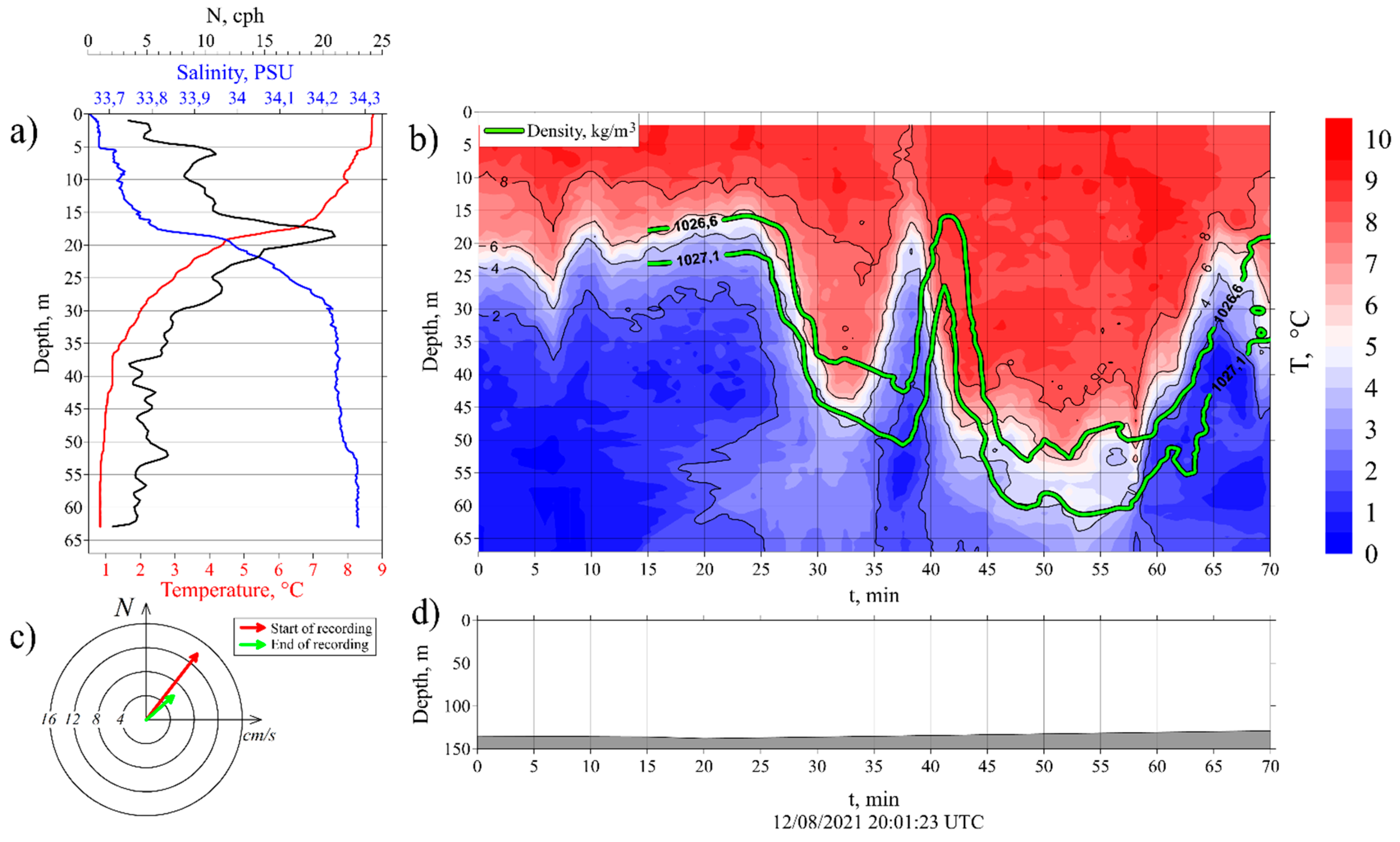

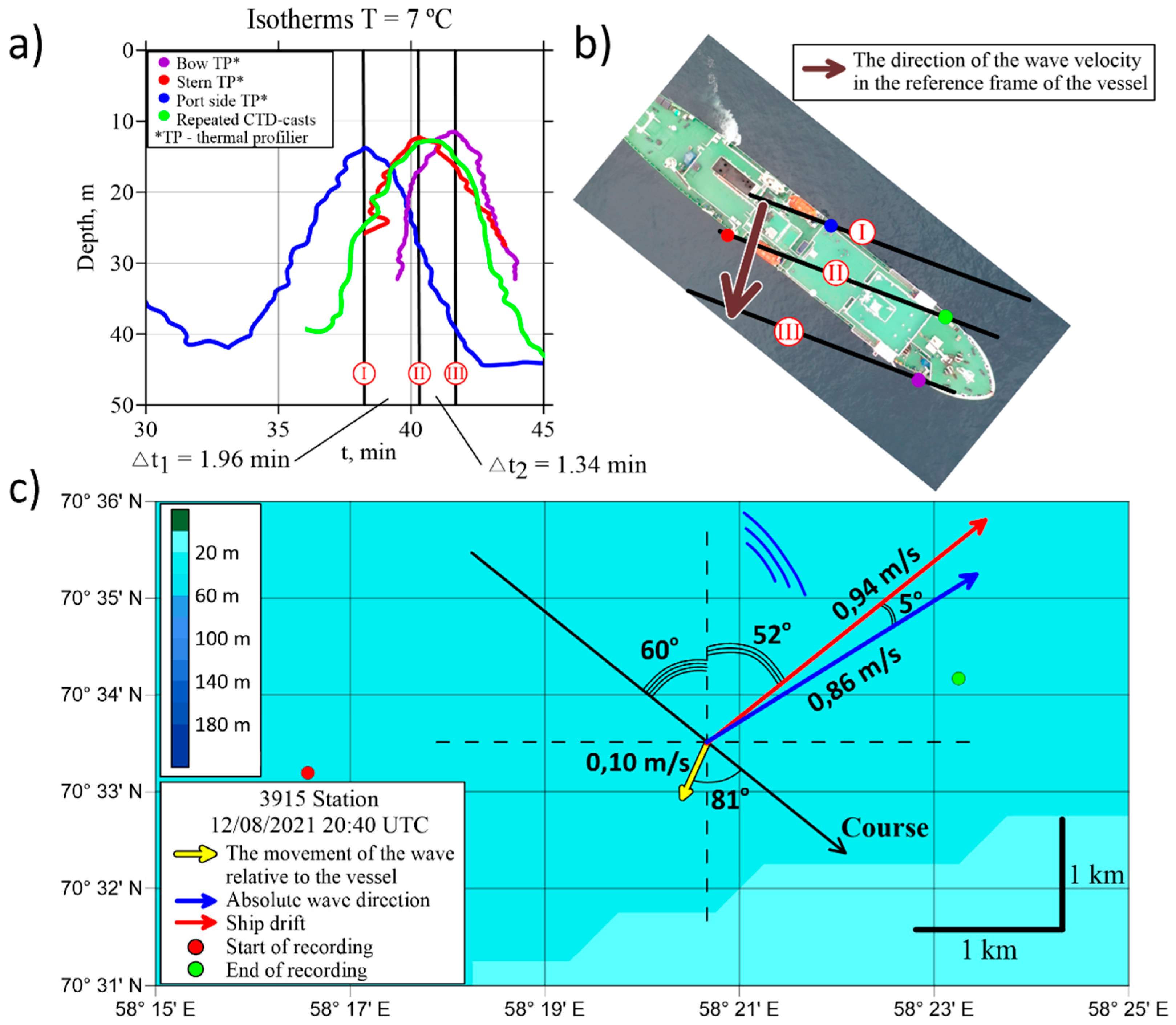

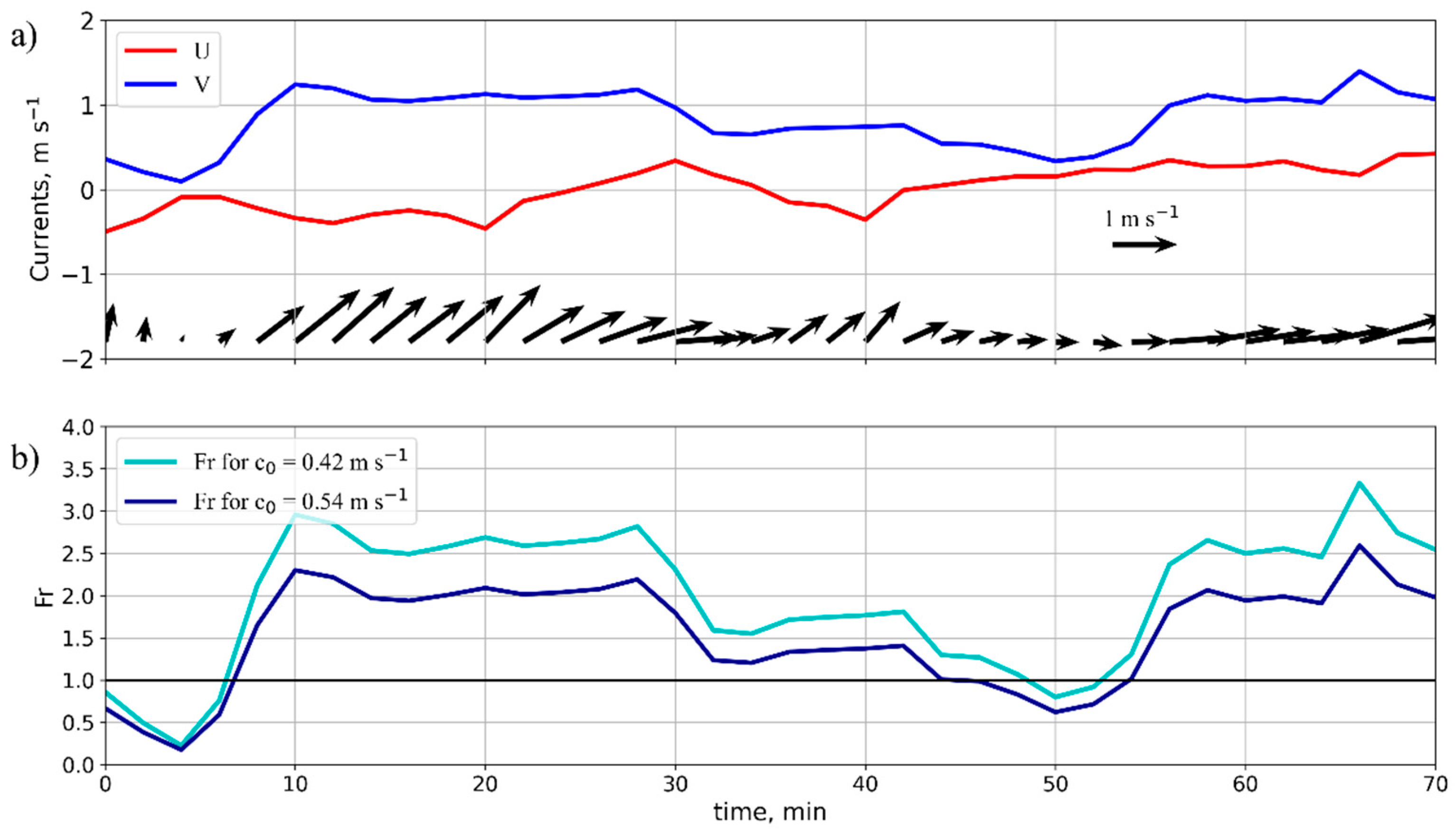

Station #3915

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pineda, J. Predictable upwelling and the shoreward transport of planktonic larvae by internal tidal bores. Science 1991, 253, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moum, J.N.; Farmer, D.M.; Smyth, W.D.; Armi, L.; Vagle, S. Structure and Generation of Turbulence at Interfaces Strained by Internal Solitary Waves Propagating Shoreward over the Continental Shelf. J. Phys. Ocean. 2003, 33, 2093–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moum, J.N.; Nash, J.D. Seafloor pressure measurements of nonlinear internal waves. J. Phys. Ocean. 2008, 38, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boegman, L.; Stastna, M. Sediment Resuspension and Transport by Internal Solitary Waves. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech 2019, 51, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, W.C.; Jones, N.L.; Rayson, M.D.; Ivey, G.N. Calibrated suspended sediment observations beneath large amplitude non-linear internal waves. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2021, 126, e2021JC017538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padman, L.; Dillon, T.M. Turbulent mixing near the Yermak Plateau during the coordinated Eastern Arctic Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1991, 96, 4769–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippeth, T.P.; Vlasenko, V.; Stashchuk, N.; Scannell, B.D.; Green, J.A.M.; Lincoln, B.J.; Bacon, S. Tidal conversion and mixing poleward of the critical latitude (an Arctic case study), Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 12349–12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fer I., Koenig Z., Kozlov I. E., Ostrowski M., Rippeth T. P., Padman L., Bosse A., Kolas E., Tidally forced lee waves drive turbulent mixing along the Arctic Ocean margins. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.E.; Atadzhanova, O.A.; Zimin, A.V. Internal solitary waves in the White Sea: hot-spots, structure, and kinematics from multi-sensor observations. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.; Romanenkov, D.; Zimin, A.; Chapron, B. SAR observing large-scale nonlinear internal waves in the White Sea. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 147, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.E.; Zubkova, E.V.; Kudryavtsev, V.N. Internal solitary waves in the Laptev Sea: first results of spaceborne SAR observations. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 2047–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimin, A.V.; Kozlov, I.E.; Atadzhanova, O.A.; Chapron, B. Monitoring short-period internal waves in the White Sea. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2016, 52, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, A.V.; Morozov, E.G.; Kozlov, I.E.; Frey, D.I. High-amplitude internal waves southeast of Spitsbergen. Cont. Shelf Res. 2021, 227, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.G.; Pisarev, S.V. Internal Waves in the Region of the Akselsundet Strait of Western Spitsbergen Island. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2023, 59, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.G.; Paka, V.T.; Bakhanov, V.V. Strong internal tides in the Kara Gates Strait. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.; Kudryavtsev, V.; Zubkova, E.V.; Zimin, A.V.; Chapron, B. Characteristics of short-period internal waves in the Kara Sea. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2015, 51, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, I.; Kudryavtsev, V.; Zubkova, E.; Atadzhanova, O.; Zimin, A.; Romanenkov, D.; Myasoedov, A.; Chapron, B. SAR observations of internal waves in the Russian Arctic seas. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 947–949. [Google Scholar]

- Morozov, E.G.; Kozlov, I.E.; Shchuka, S.A.; Frey, D.I. Internal tide in the Kara Gates Strait. Oceanology 2017, 57, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, I.H.; Karcher, M.J. Modeling the seasonal variability of circulation and hydrography in the Kara Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 13431–13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.G.; Neiman, V.G.; Shcherbinin, A.D. Internal tide in the Kara Strait. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2003, 393, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Didenko, N.I.; Cherenkov, V.I. Economic and geopolitical aspects of developing the Northern Sea Route. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 180, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, B.M. Increased maritime traffic in the Arctic: Implications for governance of Arctic sea routes. Mar. Pol. 2021, 131, 104566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B. Recent ship traffic and developing shipping trends on the Northern Sea Route—Policy implications for future arctic shipping. Mar. Pol. 2021, 124, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E.G.; Pisarev, S.V.; Erofeeva, S.Yu. Internal waves in the Russian Arctic seas. Surface and internal waves in the Arctic Ocean / Eds. I. V. Lavrenov, E. G. Morozov. Saint-Petersburg, Gidrometeoizdat. 2002; 217–234. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, B.A.; Timofeev, A.A. Modeling of the Stationary Circulation and Semidiurnal Surface and Internal Tides in the Strait of Kara Gates. Fund. Appl. Hydrophys 2015, 8, 72–79, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, I. SAR signatures of oceanic internal waves in the Barents Sea. Proc. of the SAR Oceanogr. Workshop (SeaSAR). Frascati, Italy. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, B.A.; Sofina, E.V. Surface and internal semidiurnal tides and tidally induced diapycnal diffusion in the Barents Sea: a numerical study. Cont. Shelf Res. 2014, 91, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z. A numerical simulation of the generation and evolution of nonlinear internal waves across the Kara Strait. Acta Ocean. Sinica 2019, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyaev, K.V. Internal tide at the critical latitude. Izv. Atm. Ocean. Phys. 2000, 36, 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Morozov, E.G.; Pisarev, S.V. Internal tides at the Arctic latitudes (numerical experiments). Oceanology 2002, 42, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Morozov, E.G.; Paka, V.T. Internal waves in a high-latitude region. Oceanology 2010, 50, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, V.; Stashchuk, N.; Hutter, K.; Sabinin, K. Nonlinear internal waves forced by tides near the critical latitude. Deep Sea Res. Part I. 2003, 50, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermoshkin, A.; Molkov, A. High-Resolution Radar Sensing Sea Surface States During AMK-82 Cruise. IEEE J. Select. Topics Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 2660–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisky, P.V.; Kozlov, I.E. Thermoprofilemeter for Measuring the Vertical Temperature Distribution in the Upper 100-Meter Layer of the Sea and its Testing in the Arctic Basin. Ecol. Saf. Coast. Shelf Zones Sea 2023, 1, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sandven, S.; Johannessen, O.M. High-frequency internal wave observations in the marginal ice zone. J. Geophys. Res. 1987, 92(C7), 6911–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarev, S.V. Low-frequency internal waves near the shelf edge of the Arctic 865 basin. Oceanology 1996, 36, 771–778. [Google Scholar]

- Serebryany, A.; Khimchenko, E.; Popov, O.; Denisov, D.; Kenigsberger, G. Internal Waves Study on a Narrow Steep Shelf of the Black Sea Using the Spatial Antenna of Line Temperature Sensors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrova, K.; Myslenkov, S.; Puzina, O.; Mizyuk, A.; Bykhalova, O. Water Structure in the Utrish Nature Reserve (Black Sea) during 2020–2021 According to Thermistor Chain Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erofeeva, S.; Egbert, G. Arc5km2018: Arctic Ocean Inverse Tide Model on a 5 kilometer grid. Dataset, Arctic Data Center. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhin, V.; Osadchiev, A.; Konovalova, O.P. Structure and variability of the Pechora plume in the southeastern part of the Barents Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1052044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleskerova, A.A.; Kubryakov, A.A.; Stanichny, S.V. A two-channel method for retrieval of the Black Sea surface temperature from Landsat-8 measurement. Izv. Atm. Ocean. Phys. 2017, 52, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotaev, G.; Andreas, E.; Ledimet, F.; Herlin, I.; Stanichny, S.; Solovyev, D.; Wu, L. Retrieving ocean surface current by 4-D variational assimilation of sea surface temperature images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.C.B.; Ermakov, S.A.; Robinson, I.S.; Jeans, D.R.G.; Kijashko, S.V. Role of surface films in ERS SAR signatures of internal waves on the shelf: 1. Short-period internal waves. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 8009–8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, V.; Kozlov, I.; Chapron, B.; Johannessen, J.A. Quad-polarization SAR features of ocean currents. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2014, 119, 6046–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, T.F.; Lynch, J.F.; Irish, J.D.; Beardsley, R.C.; Ramp S.R.; et al. Internal tide and nonlinear wave behavior in the continental slope in the northern South China Sea. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2004, 29, 1105–1130. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Klemas, V.; Zheng, Q.; Li, X.; Yan, X.-H. Estimating parameters of a two-layer stratified ocean from polarity conversion of internal solitary waves observed in satellite SAR images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 92, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, K.R.; Melville, W.K. Long nonlinear internal waves. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2006, 38, 395–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovsky, L.A.; Stepanyants, Y.A. Internal solitons in laboratory experiments: Comparison with theoretical models. Chaos. Interdisc. J. Nonlin. Sci. 2005, 15, 03711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.K.; Chang, Y. S.; Hsu, M.-K.; Liang, N. K. Evolution of nonlinear internal waves in the East and South China Seas. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 7995–8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrusevich, V.Y.; Dmitrenko, I.A.; Kozlov, I.E.; Kirillov, S.A.; Kuzyk, Z.Z.; Komarov, A.S.; Heath, J.P.; Barber, D.G.; Ehn, J.K. Tidally-generated internal waves in Southeast Hudson Bay. Cont. Shelf Res. 2018, 167, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grue, J.; Jensen, A.; Rusas, P.; Sveen, J. Properties of large-amplitude internal waves. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 1999, 380, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.W.; Pan, F.-S.; Renouard, D. Internal solitons on the pycnocline: generation, propagation, and shoaling and breaking over a slope. J. Fluid Mech. 1985, 59, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerkema, T.; Zimmerman, J.T.F. An introduction to internal waves. Lecture notes, Royal NIOZ, Texel 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovsky, L.A.; Irisov, V.G. Strongly nonlinear internal solitons: Models and applications. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2017, 122, 3907–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.P.; Ostrovsky, L.A. Observations of highly nonlinear internal solitons over the continental shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 2695–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.R.; Burch, T. L. Internal solitons in the Andaman Sea. Science. 1980, 208, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.J.; Thompson, D.R. Continental shelf parameters inferred from SAR internal wave observations. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology. 1999, 16, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Klemas, V.; Yan, X.-H. Theoretical expression for an ocean internal soliton synthetic aperture radar image and determination of the soliton characteristic half width. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106(C12), 31415–31423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cai, J.; Xu, T.; Guo, Z. Characteristics of Internal Solitary Waves in the Timor Sea Observed by SAR Satellite. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Xie, J.; Du, H.; Wang, S.; Xuan, P.; Wang, G.; Wei, G.; Cai, S. Analysis of the Differences in Internal Solitary Wave Characteristics Retrieved from Synthetic Aperture Radar Images under Different Background Environments in the Northern South China Sea. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Yan, X.-H.; Klemas, V. Statistical and dynamical analysis of internal waves on the continental shelf of the Middle Atlantic Bight from space shuttle photographs. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98(C5), 8495–8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovsky, L.A.; Stepanyants, Y.A. Do internal solitons exist in the ocean? Rev. Geophys. 1989, 27, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.I. Solitary waves in a finite depth fluid. J. Phys. A Mark. Gen. 1977, 10, L225–L227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, T.B. Internal waves of finite amplitude and permanent form. J. Fluid Mech. 1966, 25, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, O.M. The Dynamics of the Upper Ocean, 2nd ed.; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; 336p. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, R.; Pelinovsky, E.; Talipova, T. Solitary wave transformation in a medium with sign-variable quadratic nonlinearity and cubic nonlinearity. Physica D. 1999, 132, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäranta, M. The drift of sea ice, 2nd ed.; Springer Praxis Books; Springer-Verlag, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czipott, P.V.; Levine, M.D.; Paulson, C.A.; Menemenlis, D.; Farmer, D.M.; Williams, R.G. Ice flexure forced by internal wave packets in the Arctic Ocean. Science 1991, 254, 832–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padman, L.; Dillon, T. M. Turbulent mixing near the Yermak Plateau during the Coordinated Eastern Arctic Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. 1991, 96(C3), 4769–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, Z.; Proshutinsky, A.Y. “The Arctic Ocean tides” in The Polar Oceans Their Role Shaping Global Environment; Johannessen, O.M., Muench, R.D., Overland, J.E., Eds.; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Padman, L.; Erofeeva, S. A barotropic inverse tidal model for the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station #; Time | Length of Measurements, h | Start Latitude | Start Longitude | Start Depth, m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3909; 08:25 UTC | 1.1 | 70° 17.292' | 57° 55.797' | 176 |

| 3911; 10:59 UTC | 1.9 | 70° 21.540' | 58° 02.117' | 82 |

| 3913; 16:18 UTC | 1.4 | 70° 26.882' | 58° 07.401' | 131 |

| 3915; 20:01 UTC | 1.2 | 70° 33.275' | 58° 16.586' | 127 |

| 3917; 01:15 UTC | 0.9 | 70° 35.894' | 58° 25.495' | 148 |

| Parameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eq. # | - | (3), (6) | (3), (4) | (5), (6) | (5), (7) | (5), (9) |

| [m/s] | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | |

| [m/s] | 0.86 | 0.62-0.7 | 0.62-0.69 | 0.87-0.98 | 0.71-0.72 | 0.73-0.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).