Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

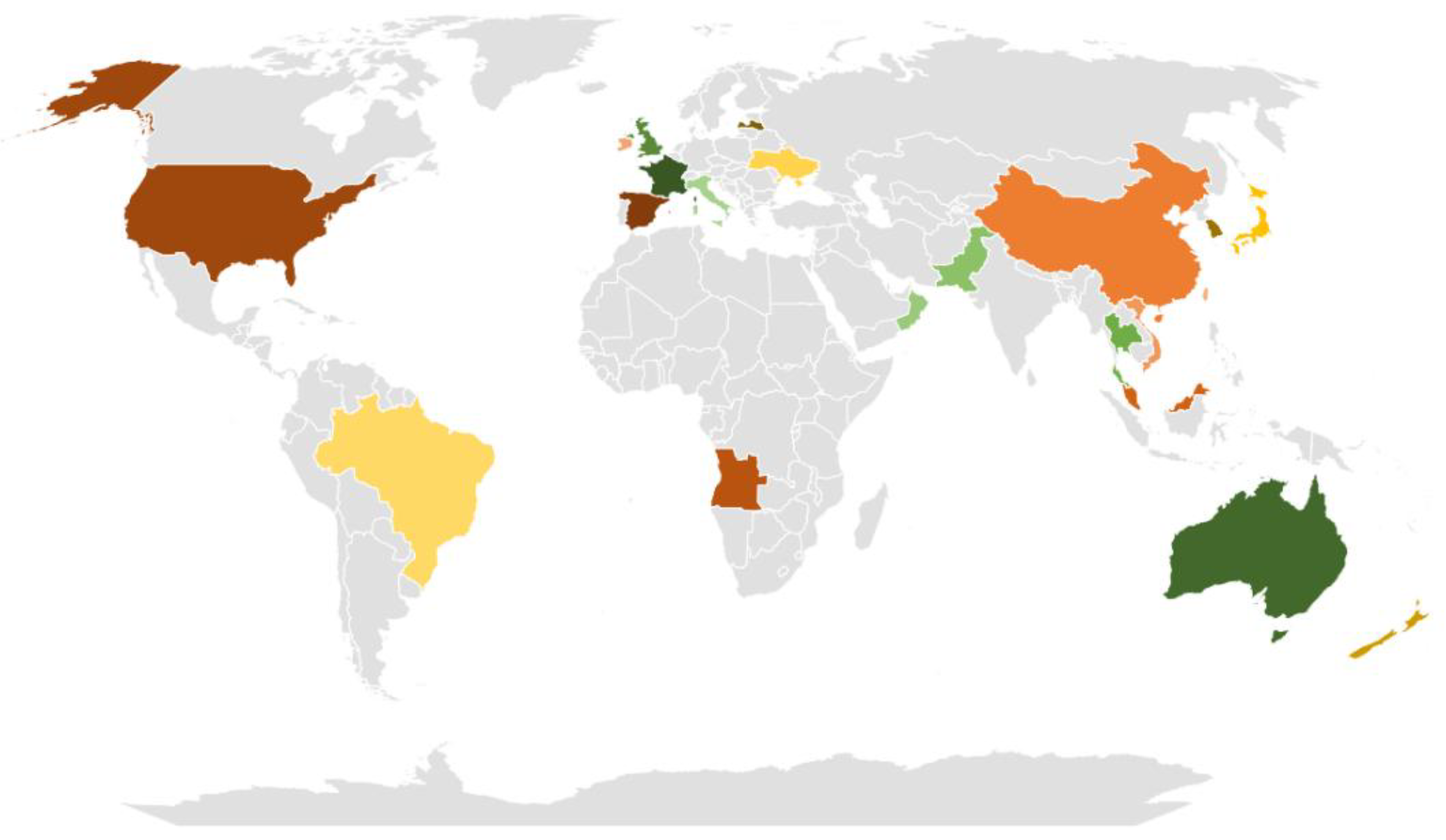

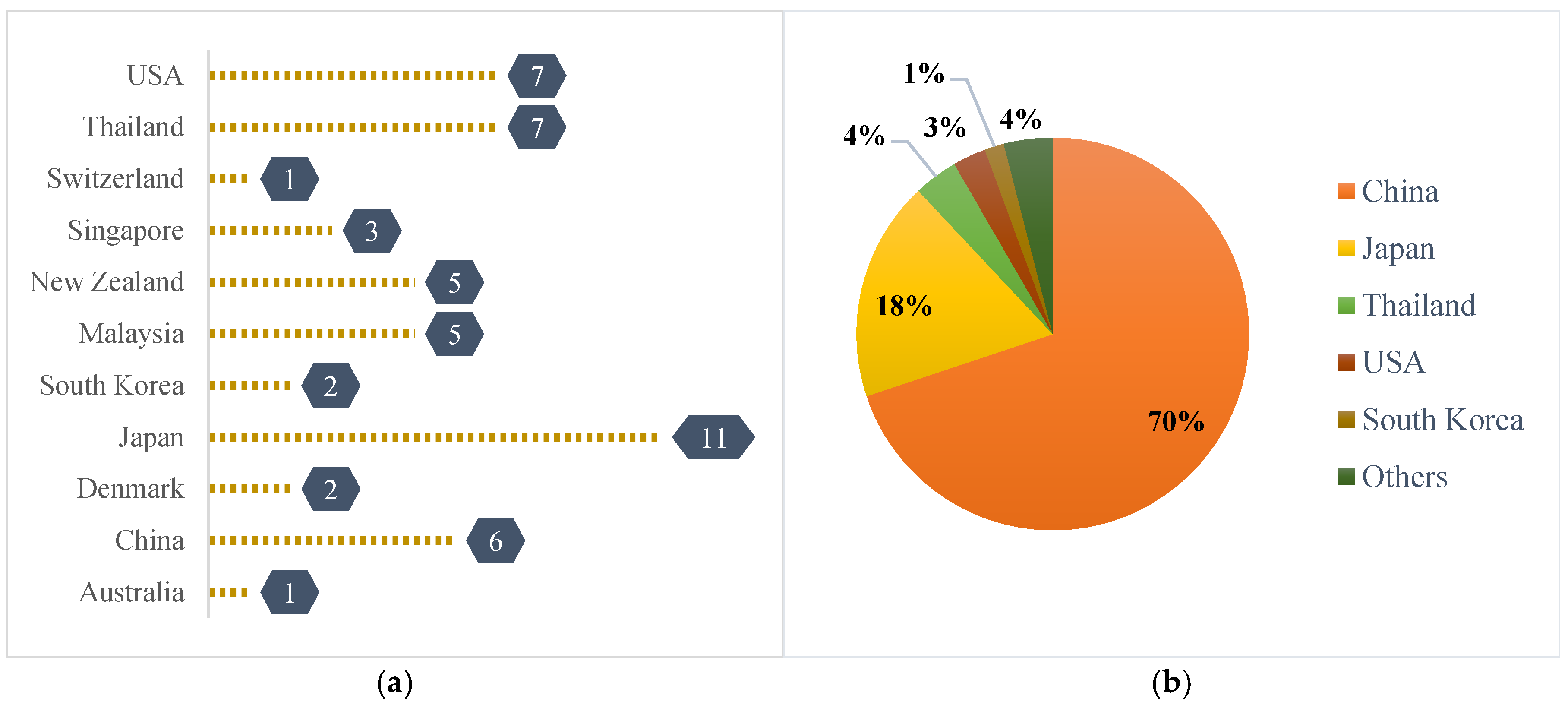

2.1. Market Survey and Collection of Samples

2.2. Measurement of Specific Gravity

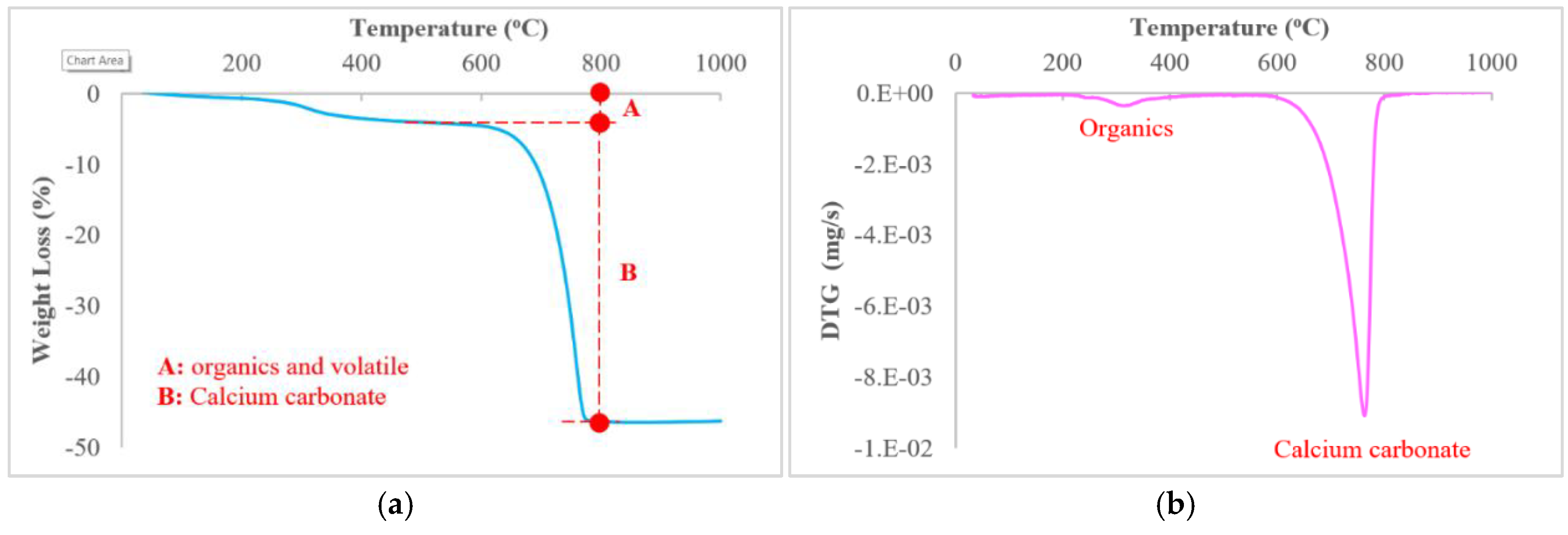

2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.4. Use of Eggshells as a Cement Replacement

2.4.1. Selection of Eggshells

2.4.2. Properties of OPC, LS, and Selected ES

2.4.3. Details of Concrete Mixes and Strength Measurement

3. Results

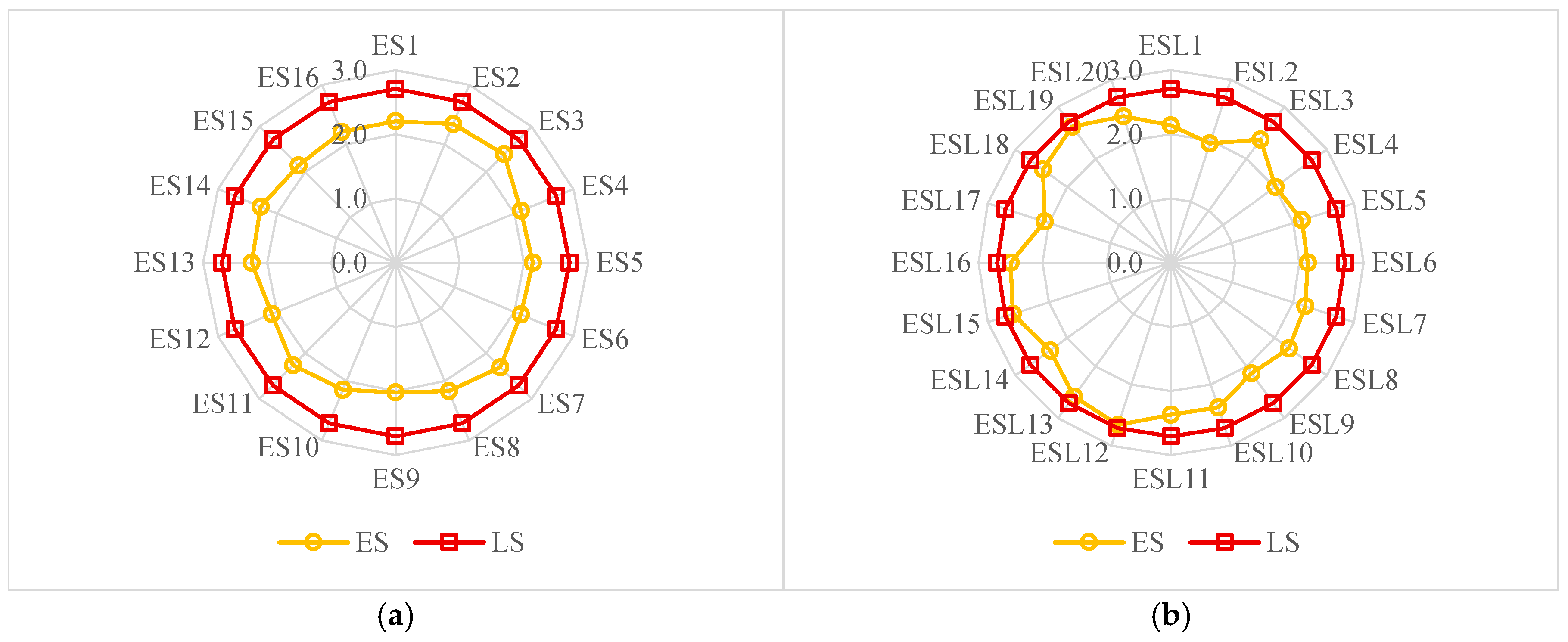

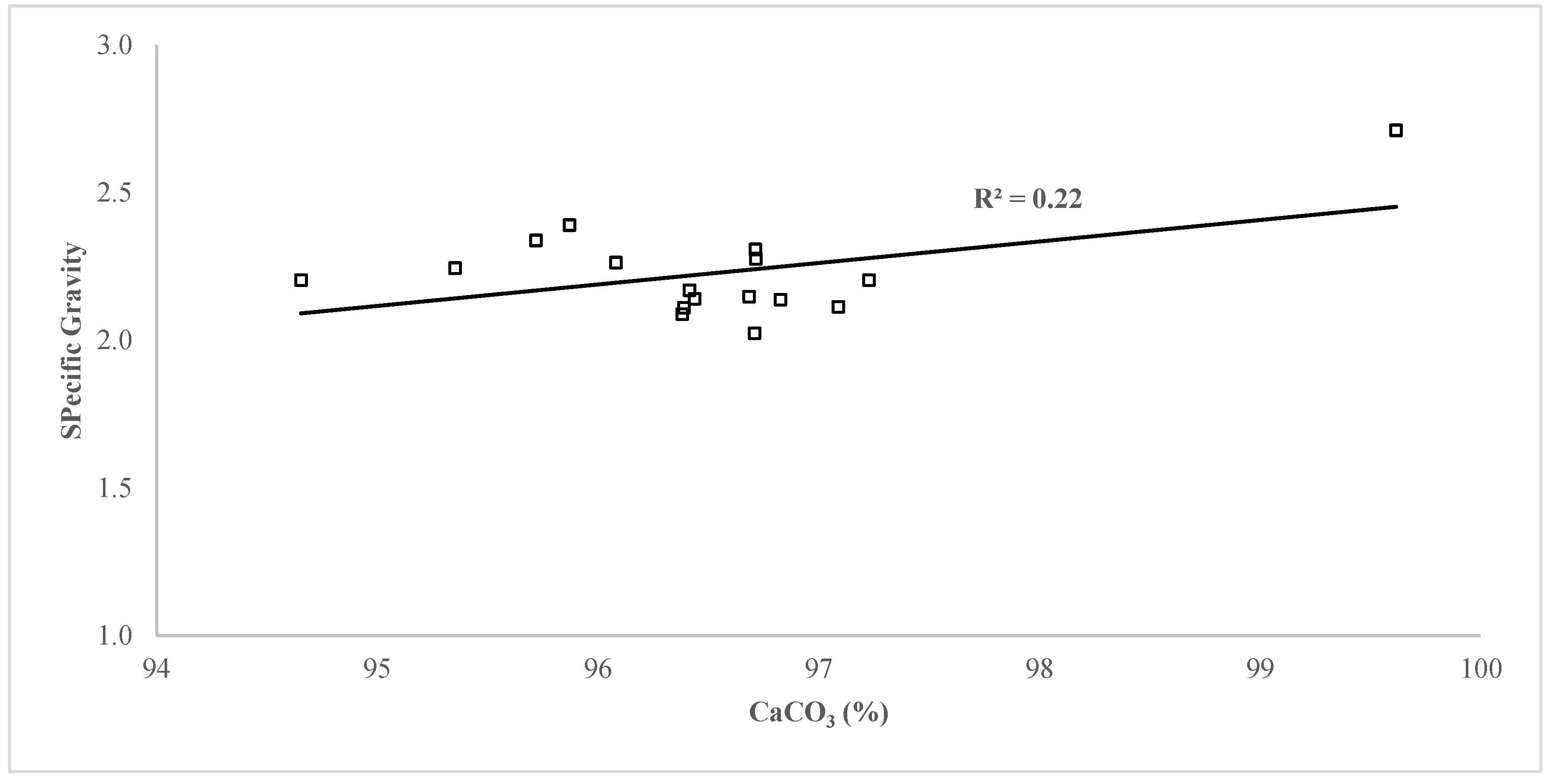

3.1. Specific Gravity of Sample Eggshells

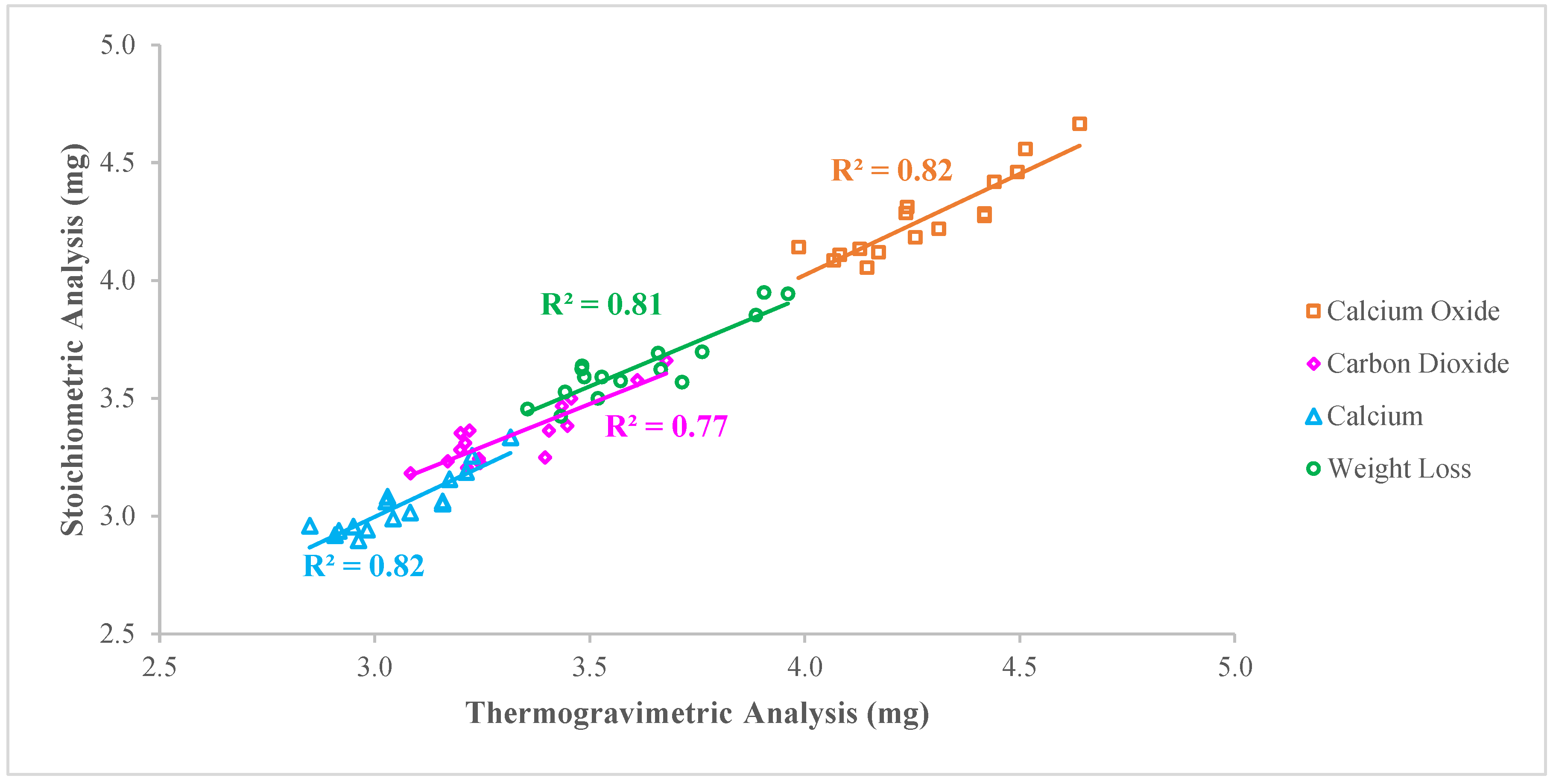

3.2. Quantification of Minerals

3.3. Application of Eggshells as a Cement Replacement

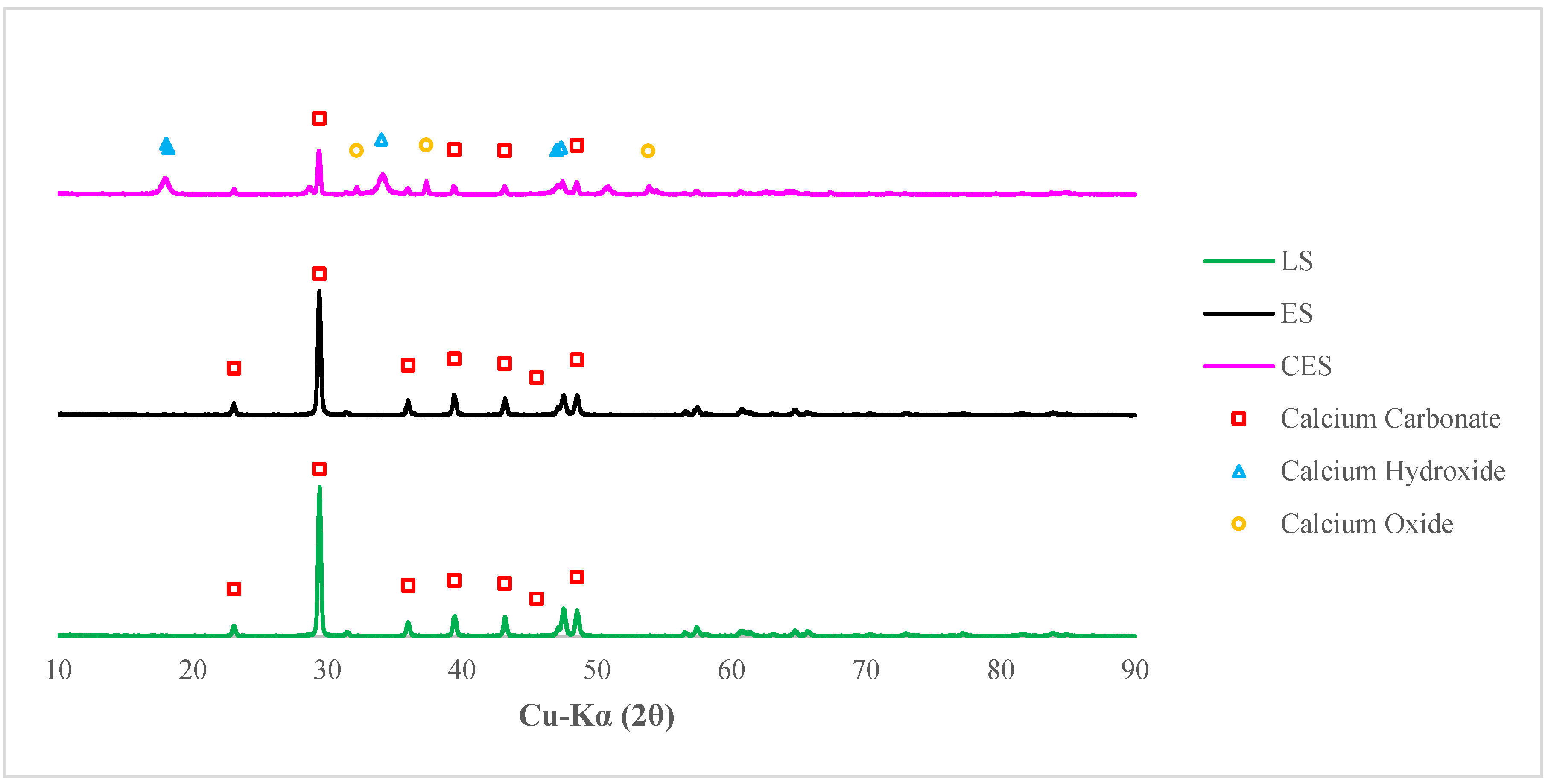

3.3.1. Selection of Eggshells and their Properties

3.3.2. Compressive Strength and Relative Change in Strength of Concrete Specimens

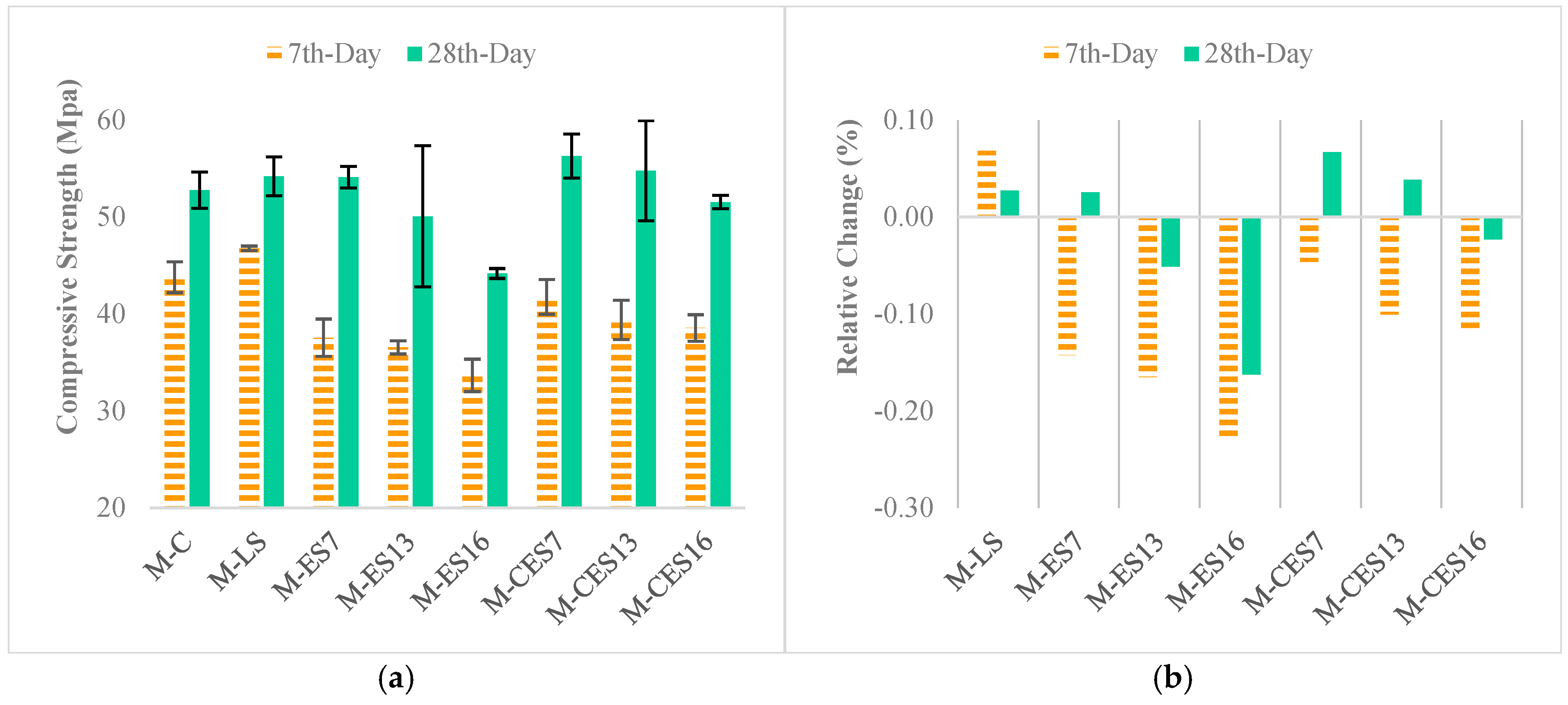

4. Discussions

4.1. Calcium carbonate vs Specific Gravity in Uncalcined Eggshells

4.2. Role of Calcium Carbonate

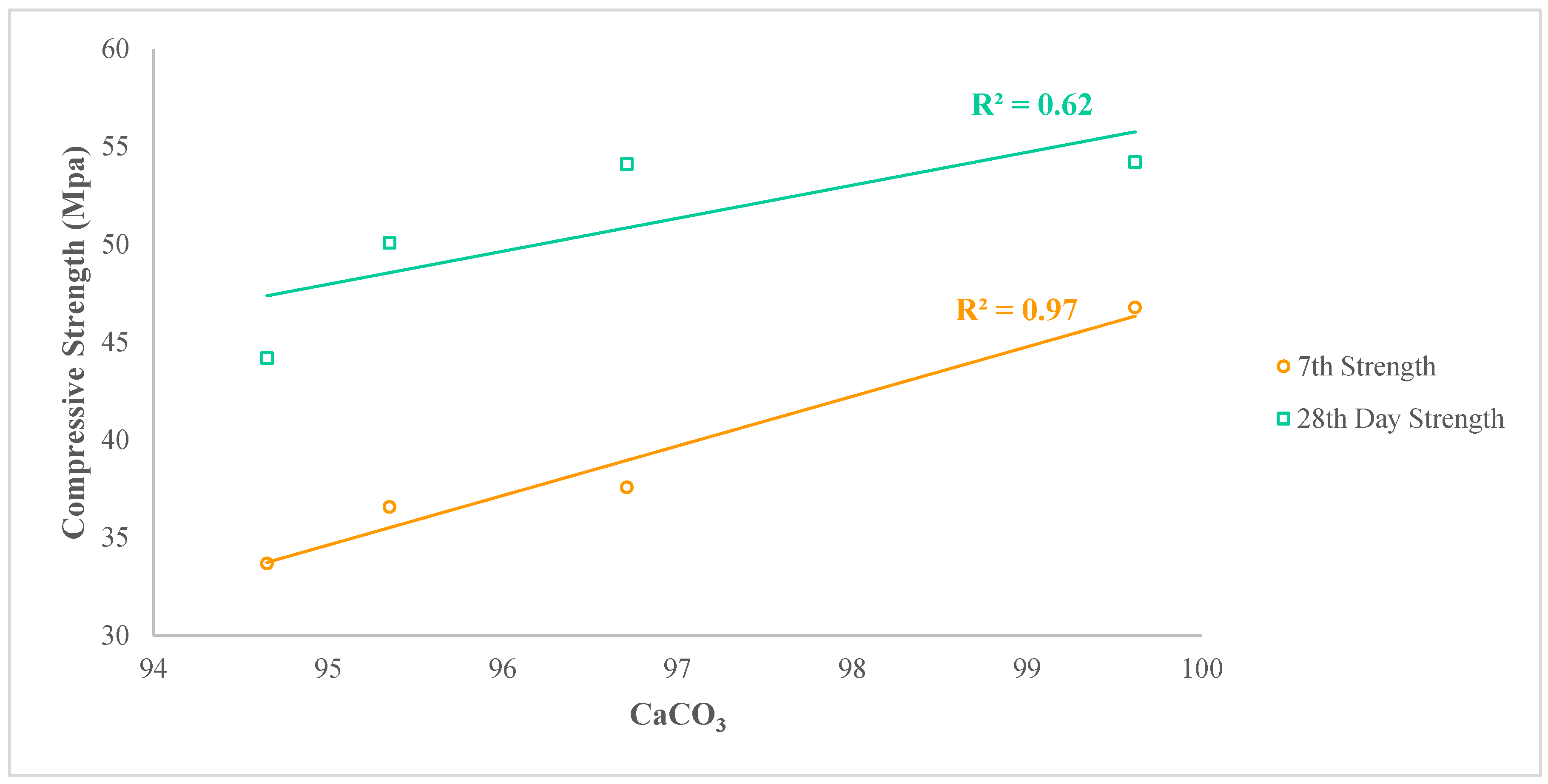

4.2.1. Calcium Carbonate vs Strength Development

4.2.2. Filler Effect and Heterogeneous Nucleation

4.3. Role of Calcium Oxide in Strength Development in Mixes with CES

5. Conclusions

- The specific gravity of eggshells from across the world is lower than that of the industrial-grade extra-pure limestone due to the presence of an organic matrix. Thus, eggshells are impure biological limestone, having less mineral content than an industrial-grade extra-pure limestone. The brown pigmentation in eggshells causes higher specific gravity, but it does not affect the mineral content. Furthermore, the quality of eggshells from different regions across the world is recommended to be defined by their micro-structure in addition to their specific gravity and mineral contents.

- The eggshells from different regions across the globe, both in the uncalcined state and calcined state with decomposed CaCO3, are viable to use as a replacement for cement in Hong Kong. The variation in strength due to the variation in mineral content is acceptable. However, the strength of mixes with calcined eggshells is closer to the control mix and the mix with limestone. The CaCO3 content is the major contributor towards strength development by producing filler/dilution effect and heterogenous nucleation, depending upon the size of particles, in addition to the CaCO3 content, whereas CaO is another factor towards strength development by increasing the quantity of free CaO in the cementitious matrix containing calcined eggshells.

Acknowledgments

References

- FAOSTAT Food Balance Sheets. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- OEC Trade Balance of Eggs in Hong Kong Available online:. Available online: https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/eggs/reporter/hkg?yearExportSelector=exportYear1. (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Quina, M.J.; Soares, M.A.; Quinta-Ferreira, R. Applications of industrial eggshell as a valuable anthropogenic resource. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummartyotin, S.; Manuspiya, H. A Critical Review of Eggshell Waste: An Effective Source of Hydroxyapatite as Photocatalyst. Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals 2018, 28, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S.; Eddie, L.S.S.; Yi, N.H.; Afzal, M. An Insight on the Sufficiency of Waste Eggshells in Hong Kong for Sustainable Commercial Applications in Cementitious Products. Preprints (Basel) 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM ASTM C911-Standard Specification for Quick Lime, Hydrated Lime, and Limestone for Selected Chemical and Industrial Uses. In ASTM Standards; West Conshohocken, PA, 2011; Vol. 06, pp. 6–8.

- Ujin, F.; Ali, K.S.; Harith, Z.Y.H. Viability of Using Eggshells Ash Affecting the Setting Time of Cement. International Journal of Civil, Environmental, Structural, Construction and Architectural Engineering 2016, 10, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, S.; Eddie, L.S. Effect of using calcined eggshells as a cementitious material on early performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Afzal, M.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Gan, J. Extension of IFC Model Schema for Automated Prefabrication of Steel Reinforcement in Concrete Structures. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Innovative Production and Construction (IPC 2020); Hong Kong, China; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Binici, H.; Aksogan, O.; Sevinc, A.H.; Cinpolat, E. Mechanical and radioactivity shielding performances of mortars made with cement, sand and egg shells. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç, A.H.; Durgun, M.Y. A novel epoxy-based composite with eggshell, PVC sawdust, wood sawdust and vermiculite: An investigation on radiation absorption and various engineering properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, D.; Pliya, P. Effect of elevated temperature on eggshell, eggshell powder and eggshell powder mortars for masonry applications. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschei, T.; Lothenbach, B.; Glasser, F.P. Thermodynamic properties of Portland cement hydrates in the system CaO–Al2O3–SiO2–CaSO4–CaCO3–H2O. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1379–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliya, P.; Cree, D. Limestone derived eggshell powder as a replacement in Portland cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyasom, S.; Tangboriboon, N. Development of biomaterial fillers using eggshells, water hyacinth fibers, and banana fibers for green concrete construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerramala, A. Properties of Concrete with Eggshell Powder as Cement Replacement. Indian Concrete Journal 2014, 88, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gowsika, D.; Kokila, S.; Sargunan, K. Experimental Investigation of Egg Shell Powder as Partial Replacement with Cement in Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2014, 14, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EXPERIMENTAL STUDY ON PARTIAL REPLACEMENT OF CEMENT WITH EGG SHELL POWDER AND SILICA FUME. Rasayan J. Chem. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Gowsika, D.; Kokila, S.; Sargunan, K. Experimental Investigation of Egg Shell Powder as Partial Replacement with Cement in Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2014, 14, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EXPERIMENTAL STUDY ON PARTIAL REPLACEMENT OF CEMENT WITH EGG SHELL POWDER AND SILICA FUME. Rasayan J. Chem. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sohu, S.; Bheel, N.; Jhatial, A.A.; Ansari, A.A.; Shar, I.A. Sustainability and mechanical property assessment of concrete incorporating eggshell powder and silica fume as binary and ternary cementitious materials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58685–58697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teara, A.; Ing, D.S. Mechanical properties of high strength concrete that replace cement partly by using fly ash and eggshell powder. Phys. Chem. Earth, Parts A/B/C 2020, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teara, A.; I Doh, S.; Chin, S.C.; Ding, Y.J.; Wong, J.; Jiang, X.X. Investigation on the durability of use fly ash and eggshells powder to replace the cement in concrete productions.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012025.

- Fatahillah, F.; Sumarno, A. The Effect of Concrete Mixture on Usage Fly Ash and Chicken Egg Shell Powder as Cement Substitutions in Concrete Compressive Strength. Neutron 2022, 22, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asman, N.S.A.; Dullah, S.; Ayog, J.L.; Amaludin, A.; Amaludin, H.; Lim, C.H.; Baharum, A.; Zainorizuan, M.; Yong, L.Y.; Siang, L.A.J.M.; et al. Mechanical Properties of Concrete Using Eggshell Ash and Rice Husk Ash As Partial Replacement Of Cement. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 103, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliko, C.; Kabubo, C.K.; Mwero, J.N. Rice Straw and Eggshell Ash as Partial Replacements of Cement in Concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 6481–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, V.; M, V.; S, T.; T, M.P. Experimental Investigation of Partial Replacement of Cement with Glass Powder and Eggshell Powder Ash in Concrete. Civ. Eng. Res. J. 2018, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.E.; Mahmood, A.A.; Min, A.Y.Y. ; A.R., N.N.; Noor, N.M.; Azhari, A. Palm Oil Fuel Ash (POFA) and Eggshell Powder (ESP) as Partial Replacement for Cement in Concrete.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 01004.

- Hamada, H.; Tayeh, B.; Yahaya, F.; Muthusamy, K.; Al-Attar, A. Effects of nano-palm oil fuel ash and nano-eggshell powder on concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.A.A.; Rasid, N.N.A.; Sam, A.R.M.; Lim, N.A.S.; Zardasti, L.; Ismail, M.; Mohamed, A.; A Majid, Z. The hydration effect on palm oil fuel ash concrete containing eggshell powder.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012047.

- A Khalid, N.H.; A Rasid, N.N. ; Mohd.Sam, A.R.; Lim, N.H.A.S.; Ismail, M.; Zardasti, L.; Mohamed, A.; A Majid, Z.; Ariffin, N.F. Characterization of palm oil fuel ash and eggshell powder as partial cement replacement in concrete.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 032002.

- Amin, M.; Attia, M.M.; Agwa, I.S.; Elsakhawy, Y.; Abu El-Hassan, K.; Abdelsalam, B.A. Effects of sugarcane bagasse ash and nano eggshell powder on high-strength concrete properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, F.; Bhuiyan, K.I.; Montasir, F.; Dey, P.; Akash, A.A.; Kumer, A. Evaluating the use of eggshell powder and sawdust ash as cement replacements in sustainable concrete development. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2025, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.O.; Ghayyib, R.J.; Radi, F.M.; Jawad, Z.F.; Nasr, M.S.; Shubbar, A. Recycling of Eggshell Powder and Wheat Straw Ash as Cement Replacement Materials in Mortar. Civ. Eng. J. 2024, 10, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.S.; Agung, A.M.S.; Putri, N.A.; Shifu, M.; Illiyanasafa, N.; Widyaningrum, B.A.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Darmokoesoemo, H. Production and characterization of eco-cement using eggshell powder and water hyacinth ash. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, N.; Habte, L.; Thenepalli, T.; Ahn, J.W. Effect of Eggshell Powder on the Hydration of Cement Paste. Materials 2019, 12, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S.; Eddie, L.S. Effect of using calcined eggshells as a cementitious material on early performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfouli, A.A. Effect of Eggshell Powder Application on the Early and Hardened Properties of Concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Mater. Appl. 2022, 4, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, S.; Goh, W.I.; Jhatial, A.A.; Lakhiar, M.T. Chemical and Fresh State Properties of Foamed Concrete Incorporating Palm Oil Fuel Ash and Eggshell Ash as Cement Replacement. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siong, L.R. Water Absorption and Strength Properties of Lightweight Foamed Concrete with 2.5% and 5.0% Eggshell as Partial Cement Replacement Material, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rehman, 2015.

- Ofuyatan, O.M.; Adeniyi, A.G.; Ijie, D.; Ighalo, J.O.; Oluwafemi, J. Development of high-performance self compacting concrete using eggshell powder and blast furnace slag as partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadi, A.S.; Sor, N.H.; Mohammed, A.A. The behavior of eco-friendly self – compacting concrete partially utilized ultra-fine eggshell powder waste.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Hilal, N.; Al Saffar, D.M.; Ali, T.K.M. Effect of egg shell ash and strap plastic waste on properties of high strength sustainable self-compacting concrete. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Afzal, M.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Gan, J. Concrete Reinforcement Modelling with IFC for Automated Rebar Fabrication. In Proceedings of the The 8th International Conference on Production and Construction (IPC 2020) will jointly organize with The 8th International Conference on Construction Engineering and Project Management (ICCEPM 2020); Hong Kong, China; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M. Evaluation and Development of Automated Detailing Design Optimization Framework for RC Slabs Using BIM and Metaheuristics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, 2019.

- Asamenew, Z.M.; Cherkos, F.D. Physio-mechanical and micro-structural properties of cost-effective waste eggshell-based self-healing bacterial concrete. Clean. Mater. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, P.; Sharma, G.; Singh, R.M. Strength behavior of alkaline activated eggshell powder and flyash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. Steel Slag—Its Production, Processing, Characteristics, and Cementitious Properties. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sofi, M.; Lumantarna, E.; Nicolas, R.S.; Kusuma, G.H.; Mendis, P. Strength Development and Thermogravimetric Investigation of High-Volume Fly Ash Binders. Materials 2019, 12, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraneni, P.; Hajibabaee, A.; Ramanathan, S.; Wang, Y.; Weiss, J. New insights from reactivity testing of supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 103, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristl, M.; Jurak, S.; Brus, M.; Sem, V.; Kristl, J. Evaluation of calcium carbonate in eggshells using thermal analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 2751–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King`oRi, A. A Review of the Uses of Poultry Eggshells and Shell Membranes. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayan, N.; P, S.K.; U. , A.A.; Soman, S. Quantitative Variation in Calcium Carbonate Content in Shell of Different Chicken and Duck Varieties. Adv. Zoöl. Bot. 2020, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, G.D.; Miles, R. Concepts of Eggshell Quality 2012, 1–2.

- Suk, Y.O.; Park, C. Effect of Breed and Age of Hens on the Yolk to Albumen Ratio in Two Different Genetic Stocks. Poult. Sci. 2001, 80, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casiraghi, E.; Hidalgo, A.; Rossi, M. Influence of Weight Grade on Shell Characteristics of Marketed Hen Eggs. In Proceedings of the XI th European Symposium on the Quality of Eggs and Egg Products; Doorwerth, Netherlands; 2005; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Lu, J. Study on the Relationship between Eggshell Colors and Egg Quality as Well as Shell Ultrastructure in Yangzhou Chicken. Afr J Biotechnol 2009, 8, 2898–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Vlčková, J.; Tůmová, E.; Ketta, M.; Englmaierová, M.; Chodová, D. Effect of housing system and age of laying hens on eggshell quality, microbial contamination, and penetration of microorganisms into eggs. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 63, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galic, A.; Filipovic, D.; Janjecic, Z.; Bedekovic, D.; Kovacev, I.; Copec, K.; Pliestic, S. Physical and mechanical characteristics of Hisex Brown hen eggs from three different housing systems. South Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 49, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, E.; Sekeroglu, A. MECHANICAL BEHAVIOR AND PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF CHICKEN EGG AS AFFECTED BY DIFFERENT EGG WEIGHTS. J. Food Process. Eng. 2010, 33, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R. Methods and Factors That Affect the Measurement of Egg Shell Quality, Poult. Sci. 1982, 61, 2022–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, J.H.; Tanaka, K. Factors Influencing Egg Shell Quality—A Review. World's Poult. Sci. J. 1970, 26, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunton, P. Research on eggshell structure and quality: an historical overview. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2005, 7, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.R. Factors Affecting Egg Internal Quality and Egg Shell Quality in Laying Hens. J. Poult. Sci. 2004, 41, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiruri, H.K.; Harrison, P.C. Effect of Roost Temperature on Performance of Chickens in Hot Ambient Environments. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 2253–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livest. Sci. 2010, 130, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayyani, N.; Bakhtiari, H. Heat Stress in Poultry: Background and Affective Factors. International journal of Advanced Biological and Biomedical Research 2013, 1, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.R. Factors Affecting Egg Shell and Internal Egg Quality. In Proceedings of the Proc. 18th Annual ASAIM SE Asian Feed Technology and Nutrition Workshop. Le Meridien Siem Reap, Cambodia; 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- M, D.; J, S.N.; A, C. A Comparative Study on Egg Shell Concrete with Partial Replacement of Cement by Fly Ash. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2015, V4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.K.; Sharma, M.A. An Experimental Study on Partial Replacement of Cement with Brick Dust (Surkhi) in Concrete. J. Civ. Construct. Eng. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Katti̇mAni̇, V.; Panga, G.S.K.; E K, G. Eggshell membrane separation methods-waste to wealth-a scoping review. 19, 18. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.H.; Ren, F.Z.; Huang, Z.J.; Zhao, H.; Guo, H.Y.; Cui, J.Y. Research of Jointing Impact Crushing, Flotation and Acid Treatment of Avian Eggshell Membrane Extraction Method. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2012, 33, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, M.A.; Ferraris, C.F.; Bentz, D. Comparative Study of Methods to Measure the Density of Cementitious Powders. J. Test. Evaluation 2016, 44, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Hsieh, J.S.; Zou, P.; Kokoszka, J. Utilization of calcium carbonate particles from eggshell waste as coating pigments for ink-jet printing paper. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 6416–6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohadi, R.; Anggraini, K.; Riyanti, F.; Lesbani, A. Preparation Calcium Oxide From Chicken Eggshells. Sriwij. J. Environ. 2016, 1, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, M.E.; Mahmood, A.A.; Min, A.Y.Y.; Khalid, N.H.A. A Review of the Mechanical Properties of Concrete Containing Biofillers.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012064.

- Yadav, V.H.; Eramma, H. Experimental Studies on Concrete for the Partial Replacement of Cement By Egg Shell Powder and Ggbs. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology 2017, 4, 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Suresh, C.; Manikandan, S.; Divya, M.; Nandhakumar, R. An Experimental Investigation of Eggshell Concrete. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 8, 851–852. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth, T.; Sasidharan, B.; Udhayakumar, M.R.; Yuvasakthi, V.; Hameed A., A. Replacement of Cement Using Eggshell and Fully Replacement by Red Sand. International Journal of Intellectual Advancements and Research in Engineering Computation 2018, 6, 1133–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.R.; Mahendran, R.; Nathan, S.G.; Sathya, D.; Thamaraikannan, K. An Experimental Study on Concrete Using Coconut Shell Ash and Egg Shell Powder. South Asian Journal of Engineering and Technology 2017, 3, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S. A Study on Compressive Strength of Concrete by Partial Replacement of Cement with Dolomite Powder. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 7, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, R. Specific Gravity of Eggs and Eggshell Weight from Commercial Layers and Broiler Breeders in Relation to Time of Oviposition. Poult. Sci. 1991, 70, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Mesha, A. N. Mesha, A. Roopa, P.S.B. A Thesis on Partial Replacement of Cement by Eggshell Powder and Fine Aggregate by Crushed Gullet Pieces. International Journals of Advanced Research in Computer Science and Software Engineering ISSN: 2277-128X (Volume-8, Issue-4) 2018, 347–354.

- Yerramala, A. Properties of Concrete with Eggshell Powder as Cement Replacement. Indian Concrete Journal 2014, 88, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Adogla, F.; Paa Kofi Yalley, P.; Arkoh, M. Improving Compressed Laterite Bricks Using Powdered Eggshells. Int J Eng Sci (Ghaziabad) 2016, 5, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, G.; Pathak, N. Strength and Durability Study on Standard Concrete with Partial Replacement of Cement and Sand Using Egg Shell Powder and Earthenware Aggregates for Sustainable Construction. International Journal for Research & Development in Technology 2017, 8, 360–371. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, K.; Kuang, W.; Yan, S.; Wang, Z.; Lee, H. Utilization of bio-waste eggshell powder as a potential filler material for cement: Analyses of zeta potential, hydration and sustainability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, S.M. Improving mechanical properties of lightweight Porcelanite aggregate concrete using different waste material. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.N.; Holanda, J.N.F. Characterization of avian eggshell waste aiming its use in a ceramic wall tile paste. 52. [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, B.Z.; Yehualaw, M.D.; Taffese, W.Z.; Vo, D.-H. Optimizing Alkali-Activated Mortars with Steel Slag and Eggshell Powder. Buildings 2024, 14, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi, R.; Le, M.-T.; Khabbaz, H.; Fatahi, B. Eggshell Powder as an Ameliorating Agent for Cement-Stabilised Expansive Soil in Road Construction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation Geotechnics; Springer, 2024; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupoirieux, L.; Pourquier, D.; Souyris, F. Powdered eggshell: a pilot study on a new bone substitute for use in maxillofacial surgery. J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 1995, 23, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Materials for Making Concrete. In Advanced Concrete. In Advanced Concrete Technology; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2011; ISBN 9780470437438. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.; Yang, J.; Lai, C.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, C.; Yeh, C. Characterization and adsorption properties of eggshells and eggshell membrane. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, S.M. Improving mechanical properties of lightweight Porcelanite aggregate concrete using different waste material. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Al-Attar, A.; Yahaya, F.M.; Muthusamy, K.; Humada, A.M. The present state of the use of eggshell powder in concrete: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, F.S.; Rodrigues, P.O.; de Campos, C.M.T.; Silva, M.A.S. Physicochemical study of CaCO3 from egg shells. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 27, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoon, T. Characterization of calcium oxide derived from waste eggshell and its application as CO2 sorbent. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 3291–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesbani, A.; Tamba, P.; Mohadi, R.; Fahmariyanti, F. PREPARATION OF CALCIUM OXIDE FROM Achatina fulica AS CATALYST FOR PRODUCTION OF BIODIESEL FROM WASTE COOKING OIL. Indones. J. Chem. 2013, 13, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayan, N.; P, S.K.; U. , A.A.; Soman, S. Quantitative Variation in Calcium Carbonate Content in Shell of Different Chicken and Duck Varieties. Adv. Zoöl. Bot. 2020, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, D.; Rutter, A. Sustainable Bio-Inspired Limestone Eggshell Powder for Potential Industrialized Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Lu, J. Study on the Relationship between Eggshell Colors and Egg Quality as Well as Shell Ultrastructure in Yangzhou Chicken. Afr J Biotechnol 2009, 8, 2898–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, N.S.; Robinson, N.A.; Renema, R.A.; Robinson, F.E. Shell Quality and Color Variation in Broiler Breeder Eggs. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 1999, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.D.G.; Deeming, D. Correlation between shell colour and ultrastructure in pheasant eggs. Br. Poult. Sci. 2001, 42, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.E. Egg & Eggshell Quality.; Iowa State University Press, 1997; ISBN 0813828279.

- Tůmová, E.; Englmaierová, M.; Ledvinka, Z.; Charvátová, V. Interaction between housing system and genotype in relation to internal and external egg quality parameters. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 56, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketta, M.; Tůmová, E. Eggshell structure, measurements, and quality-affecting factors in laying hens: a review. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 61, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschei, T.; Lothenbach, B.; Glasser, F.P. Thermodynamic properties of Portland cement hydrates in the system CaO–Al2O3–SiO2–CaSO4–CaCO3–H2O. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1379–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipavec, A.; Gabrovšek, R.; Vuk, T.; Kaučič, V.; Maček, J.; Meden, A. Carboaluminate Phases Formation During the Hydration of Calcite-Containing Portland Cement. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 94, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Pandey, S. Influence of mineral additives on the hydration characteristics of ordinary Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Jennings, H.M.; Chen, J.J. Influence of Nucleation Seeding on the Hydration Mechanisms of Tricalcium Silicate and Cement. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 4327–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, E.H.; Aggoun, S.; De Schutter, G.; Ezziane, K. Combined effect of chemical nature and fineness of mineral powders on Portland cement hydration. Mater. Struct. 2009, 43, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöler, A.; Lothenbach, B.; Winnefeld, F.; Ben Haha, M.; Zajac, M.; Ludwig, H.-M. Early hydration of SCM-blended Portland cements: A pore solution and isothermal calorimetry study. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 93, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, C.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, Z.; Jia, H. A review on effects of limestone powder on the properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 192, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavetti, V.; Donza, H.; Menéndez, G.; Cabrera, O.; Irassar, E. Limestone filler cement in low w/c concrete: A rational use of energy. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; Lawrence, P.; Ringot, E. Efficiency of mineral admixtures in mortars: Quantification of the physical and chemical effects of fine admixtures in relation with compressive strength. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, H. Long-term properties of concrete containing limestone powder. Mater. Struct. 2017, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y. Modeling of Hydration, Compressive Strength, and Carbonation of Portland-Limestone Cement (PLC) Concrete. Materials 2017, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutter, G. De Effect of Limestone Filler as Mineral Addition in Self Compacting Concrete. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference on Our World in Concrete and Structures: “Recenet Advances in the Technology of Fresh Concrete”; Ghent University, Department of Structural Engineering: Ghent, 2011; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, S.; Oyabu, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Yamada, H.; Kühnle, A. True Atomic-Resolution Imaging of (101̅4) Calcite in Aqueous Solution by Frequency Modulation Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 2009, 25, 2850–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, K.; Aguayo, M.; Oey, T.; Sant, G.; Neithalath, N. Hydration and strength development in ternary portland cement blends containing limestone and fly ash or metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 39, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P.; Ardani, A.; Barrett, T.; Jones, S.Z.; Lootens, D.; Peltz, M.A.; Sato, T.; Stutzman, P.E.; Tanesi, J.; Weiss, W.J. Multi-scale investigation of the performance of limestone in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsanitgarn, P.; Wongkeo, W.; Chaipanich, A.; Poon, C.S. Heat of hydration of Portland high-calcium fly ash cement incorporating limestone powder: Effect of limestone particle size. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 66, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïtcin, P.C. Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Blended Cements; Elsevier Ltd: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780081006962. [Google Scholar]

- Mtarfi, N.H.; Rais, Z.; Taleb, M. Effect of Clinker Free Lime and Cement Fineness on the Cement Physicochemical Properties. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science 2017, 8, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar]

- Aïtcin, P.C. Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Blended Cements; Elsevier Ltd: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780081006962. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, C.; Liu, Y.; Jia, M.; Yu, K.; Yu, Z.; Yang, Y. Effect of calcium oxide on mechanical properties and microstructure of alkali-activated slag composites at sub-zero temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.-H.; Chang, J.-E.; Chiang, L.-C. Replacement of raw mix in cement production by municipal solid waste incineration ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Designation | Country | Color | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ES1 | China | Dark Brown | Market |

| ES2 | China | Light Brown | |

| ES3 | Thailand | Dark Brown | |

| ES4 | Japan | White | |

| ES5 | Japan | Dark Brown | |

| ES6 | USA | White | |

| ES7 | USA | Dark Brown | |

| ES8 | Singapore | Dark Brown | |

| ES9 | Singapore | White | |

| ES10 | Malaysia | Dark Brown | |

| ES11 | New Zealand | Dark Brown | |

| ES12 | South Korea | Dark Brown | |

| ES13 | China | Dark Brown | Restaurants |

| ES14 | China | Light Brown | |

| ES15 | Japan | Dark Brown | |

| ES16 | Japan | White |

| Oxide Composition (%) | Bogue’s Components (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | K2O | CaO | Fe2O3 | Others | C3S | C2S | C3A | C4AF |

| 1.12 | 5.45 | 19.10 | 0.13 | 4.51 | 0.67 | 65.50 | 3.00 | 0.43 | 67.66 | 3.74 | 9.37 | 9.13 |

| Specimen | OPC | LS/ES/CES | Fine Aggregates | Coarse Aggregates | w/b | a/b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kg/m3 | Kg/m3 | Kg/m3 | Kg/m3 | |||

| Control | 600 | - | 600 | 1200 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Non-Control | 570 | 30 | 600 | 1200 | 0.5 | 3 |

| Designation | Country | Specific Gravity |

|---|---|---|

| ES1 | China | 2.20 |

| ES2 | China | 2.34 |

| ES3 | Thailand | 2.39 |

| ES4 | Japan | 2.11 |

| ES5 | Japan | 2.14 |

| ES6 | USA | 2.11 |

| ES7 | USA | 2.31 |

| ES8 | Singapore | 2.17 |

| ES9 | Singapore | 2.02 |

| ES10 | Malaysia | 2.15 |

| ES11 | New Zealand | 2.26 |

| ES12 | South Korea | 2.09 |

| ES13 | China | 2.24 |

| ES14 | China | 2.28 |

| ES15 | Japan | 2.14 |

| ES16 | Japan | 2.20 |

| Average | 2.20 ± 0.01 | |

| Reference | Designation | Region | Specific Gravity |

|---|---|---|---|

| [76] | ESL1 | Malaysia | 2.14 |

| [69] | ESL2 | India | 1.95 |

| [47] | ESL3 | India | 2.37 |

| [77] | ESL4 | India | 2.01 |

| [78] | ESL5 | India | 2.14 |

| [79] | ESL6 | NA | 2.13 |

| [80] | ESL7 | NA | 2.20 |

| [81] | ESL8 | Pakistan | 2.27 |

| [82] | ESL9 | USA | 2.09 - 2.18 |

| [83] | ESL10 | NA | 2.37 |

| [84] | ESL11 | India | 2.37 |

| [70] | ESL12 | Bangladesh | 2.66 |

| [85] | ESL13 | Ghana | 2.58 |

| [86] | ESL14 | India | 2.33 |

| [87] | ESL15 | South Korea | 2.59 |

| [14] | ESL16 | Canada | 2.50 |

| [88] | ESL17 | Iraq | 2.07 |

| [89] | ESL18 | Brazil | 2.47 |

| [90] | ESL19 | Ehtiopia | 2.62 |

| [91] | ESL20 | Australia | 2.40 |

| Average | 2.29 ± 0.21 | ||

| Sample | A1 | B2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | V4 | Thermogravimetric Analysis | Stoichiometric Analysis | CaCO3 | |||||||

| CaO | ΔW | CO2 | Ca | CaO | ΔW | CO2 | Ca | ||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| LS | 0.38 | - | 55.79 | 44.21 | 43.82 | 39.87 | 55.78 | 44.22 | 43.84 | 39.92 | 99.62 |

| ES1 | 1.14 | 1.63 | 54.83 | 45.17 | 42.40 | 39.18 | 54.44 | 45.56 | 42.79 | 38.96 | 97.23 |

| ES2 | 0.94 | 3.35 | 53.61 | 46.39 | 42.10 | 38.31 | 53.59 | 46.41 | 42.12 | 38.36 | 95.72 |

| ES3 | 1.24 | 2.89 | 51.76 | 48.24 | 44.11 | 36.99 | 53.68 | 46.32 | 42.19 | 38.42 | 95.87 |

| ES4 | 0.91 | 2.00 | 54.23 | 45.77 | 42.86 | 38.76 | 54.36 | 45.64 | 42.73 | 38.91 | 97.09 |

| ES5 | 1.09 | 2.08 | 55.29 | 44.71 | 41.54 | 39.51 | 54.22 | 45.78 | 42.61 | 38.80 | 96.83 |

| ES6 | 1.15 | 2.46 | 53.70 | 46.30 | 42.69 | 38.37 | 53.97 | 46.03 | 42.42 | 38.63 | 96.39 |

| ES7 | 1.30 | 1.99 | 53.61 | 46.39 | 43.10 | 38.31 | 54.15 | 45.85 | 42.56 | 38.76 | 96.71 |

| ES8 | 1.22 | 2.37 | 55.92 | 44.08 | 40.50 | 39.96 | 53.98 | 46.02 | 42.43 | 38.64 | 96.41 |

| ES9 | 1.05 | 2.23 | 53.95 | 46.06 | 42.77 | 38.55 | 54.15 | 45.85 | 42.56 | 38.76 | 96.71 |

| ES10 | 1.22 | 2.10 | 55.93 | 44.08 | 40.76 | 39.97 | 54.14 | 45.86 | 42.55 | 38.75 | 96.69 |

| ES11 | 1.34 | 2.58 | 52.98 | 47.02 | 43.10 | 37.86 | 53.80 | 46.20 | 42.28 | 38.50 | 96.08 |

| ES12 | 1.51 | 2.11 | 55.27 | 44.73 | 41.11 | 39.49 | 53.97 | 46.03 | 42.42 | 38.62 | 96.38 |

| ES13 | 1.23 | 3.42 | 54.18 | 45.82 | 41.17 | 38.72 | 53.39 | 46.61 | 41.96 | 38.21 | 95.35 |

| ES14 | 1.01 | 2.28 | 53.73 | 46.27 | 42.98 | 38.40 | 54.15 | 45.85 | 42.56 | 38.76 | 96.72 |

| ES15 | 1.09 | 2.47 | 55.28 | 44.72 | 41.15 | 39.51 | 54.00 | 46.00 | 42.44 | 38.65 | 96.44 |

| ES16 | 1.34 | 4.01 | 53.51 | 46.49 | 41.15 | 38.24 | 53.00 | 47.00 | 41.66 | 37.93 | 94.65 |

| Aver. | 1.17 | 2.50 | 54.24 | 45.76 | 42.09 | 38.76 | 53.94 | 46.06 | 42.39 | 38.61 | 96.33 |

| Component | Stochiometric Analysis | Thermogravimetric Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extra Pure Limestone | Eggshells from different countries | Difference | ||

| % | % | % | % | % |

| Ca | 40.08 | 40.03 | 40.24 | 0.21 |

| C | 11.99 | 12.01 | 11.93 | 0.08 |

| O | 47.93 | 47.97 | 47.83 | 0.13 |

| CO2 | 43.92 | 43.99 | 43.70 | 0.30 |

| CaO | 56.08 | 56.01 | 56.30 | 0.30 |

| Material | D [4,3] | D (50) | D (90) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (μm) | (μm) | (μm) | |

| OPC | 17.53 | 11.56 | 42.86 |

| LS | 20.27 | 17.74 | 38.90 |

| ES-7 | 21.26 | 14.62 | 51.45 |

| ES-13 | 16.76 | 10.14 | 42.67 |

| ES-16 | 13.94 | 8.00 | 35.98 |

| CES-7 | 30.21 | 24.98 | 63.83 |

| CES-13 | 24.09 | 16.43 | 56.25 |

| CES-16 | 31.27 | 24.87 | 66.68 |

| S. No | Calcined Eggshells | CaCO3 | Ca(OH)2 | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| 1 | CES7 | 37.5 | 55.3 | 7.2 |

| 2 | CES13 | 37.6 | 55.1 | 7.4 |

| 3 | CES16 | 36.7 | 54.6 | 8.7 |

| Specimens | Compressive Strength | |

|---|---|---|

| 7th Day | 28th | |

| MPa | MPa | |

| Control | 43.79 ± 1.59 | 52.76 ± 1.85 |

| M-LS5 | 46.77 ± 0.23 | 54.20 ± 2.01 |

| M-ES | 35.93 ± 2.19 | 49.45 ± 4.39 |

| M-CES | 39.90 ± 2.09 | 54.20 ± 3.54 |

| Mix | CaO in CES | CaO in OPC | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | HM | LSF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | |||

| OPC | - | 65.5 | 19.1 | 5.45 | 3 | 2.377 | 1.057 |

| M-CES7 | 7.2 | 65.5 | 19.1 | 5.45 | 3 | 2.391 | 1.063 |

| M-CES13 | 7.4 | 65.5 | 19.1 | 5.45 | 3 | 2.392 | 1.063 |

| M-CES16 | 8.7 | 65.5 | 19.1 | 5.45 | 3 | 2.394 | 1.064 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).