1. Introduction

Since the first side-chain liquid crystal polymer been reported in 1978 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. the interest in the synthesis and applications of side-chain liquid crystal polymers (SCLCPs) has evolved. Side-chain liquid crystal polymers are polymers, where mesogenic units are attached to backbones via flexible spacers. Thus, three elements are crucial in determining the properties of liquid crystal side-chain polymers: the polymer backbones, the spacers and the mesogenic units. Among all the backbones reported in the literature, polymethylsiloxanes are arguably the most flexible; this is combined with their excellent thermal stability and low glass transition temperatures. For a given backbone, the molecular structure of the mesogenic units, together with the length and parity of spacers, can have a profound effect on liquid crystal properties and the transition temperature ranges. However, as crystallization might be observed in some of the SCLCPs, a considerable amount of effort has been carried out to prevent polymers from unwanted crystallization and to reduce glass transition temperatures. Examples of such efforts are the use of different type of spacers [

7], the variation of the length of the spacers [

8], the use of mesogens which are either terminally or laterally attached to the side chains [

9], the use of copolymers with different mesogenic units [

10] or even simply the use non-mesogenic groups [

11,

12].

So far, there is no reports on polysiloxanes coupled with side chain dimers to form side chain liquid crystal polymer that exhibits N

tb phase behavior; though it is noted, that number of polymers have been reported that carry di-mesogenic side chains, mainly based on malonate branching groups [

13,

14,

15]. The N

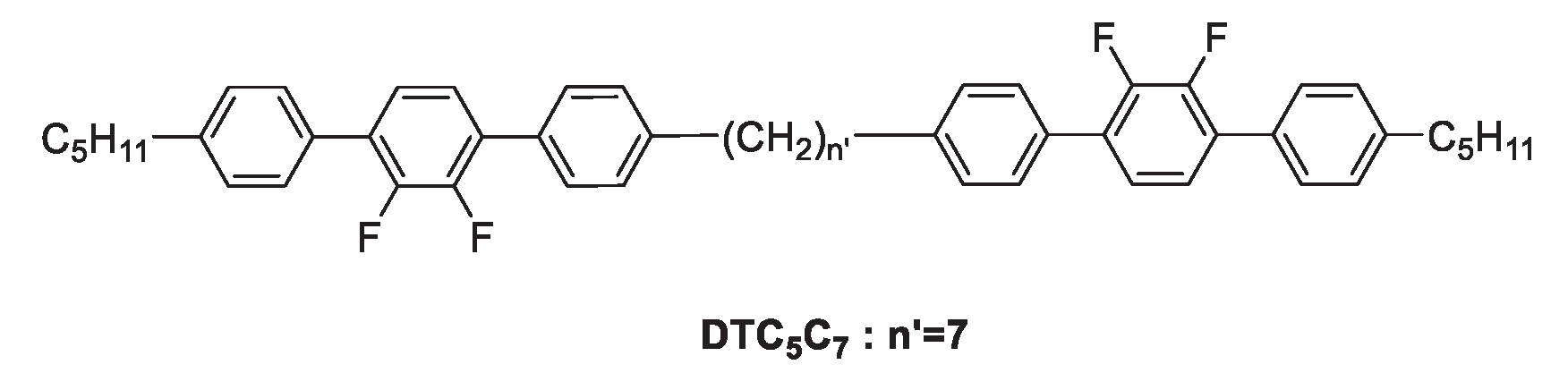

tb phase for dimers is known to show often non-typical optical defect textures, also it is not easy to distinguish it from the nematic phase by X-ray diffraction. So, in this study, a monomer was designed to consist of hydrocarbon units as spacers, triphenyl and biphenyl as mesogenic units, together with terminal double bonds, all designed for controlling the transition temperature and phase sequence.

The reason why this architecture was chosen is because (a) it has been reported that dimers with similar structures such as

DTC5Cn show the N

tb phase [

16], even for related linear oligomers [

17] (b) the dimers structurally related to the system discussed here exhibit the N

tb phase over a large temperature range, a feature that makes it possible to tune the transition temperature of the N

tb phase by fine tuning the architecture [

18]. Also, (c) a nonsymmetric mesogenic system containing altogether five aromatic rings may result in a lower melting point when compared with a six membered ring system. This is critical, as the transition temperatures of side chain polymers are often higher than these of the monomers. Since pentamethydisiloxane derivatives can exhibit properties associated with polymers and maintain the low viscosity of monomers, it is interesting to investigate the liquid crystal functionalized N

tb system too. Additional results of a copolymerization that was carried out to eliminate crystallization are reported. The overall approach is shown in

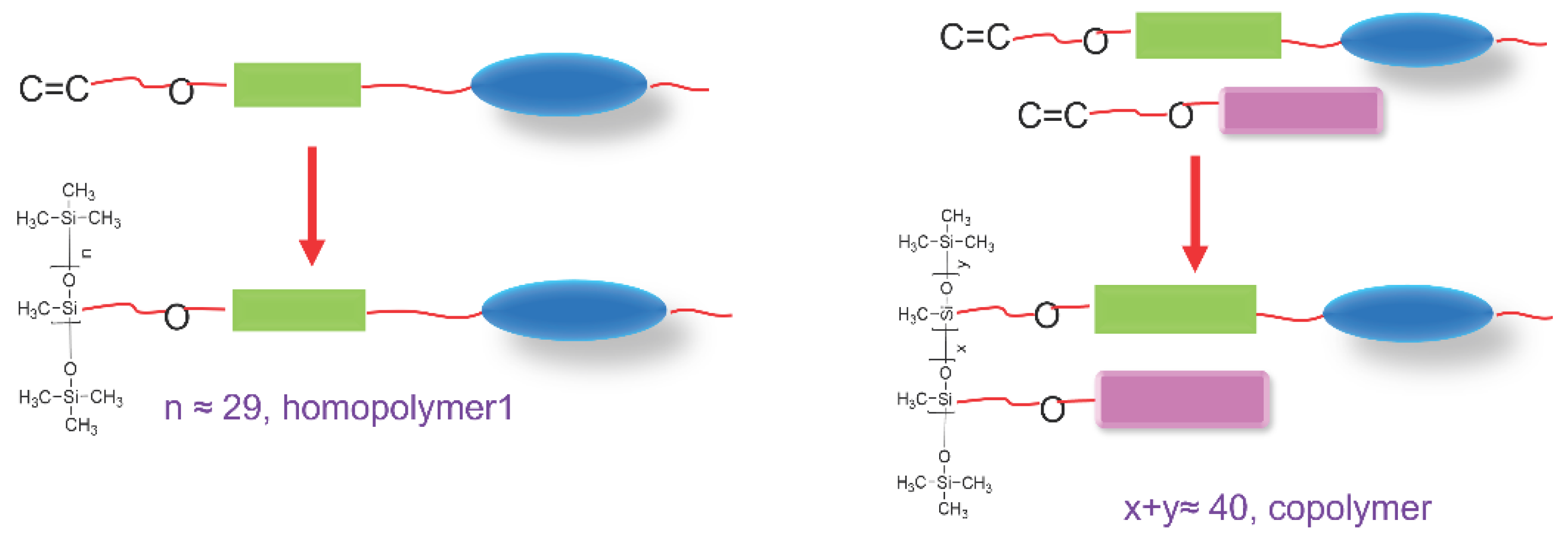

Figure 1.

There were two challenges in this project. Firstly, there was a challenge in the preparation of the mesogen. The challenges is that isomers were formed. They are a byproduct of the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction in presence of hydrocarbon chains that carry olefinic functions. To eliminate the isomers, a co-catalyst has been used together with the conventional Pd catalyst. The second challenge was that it is difficult to identify the Ntb phase of polymers, therefore, binary mixtures of the homopolymer with the Ntb forming material were used to observe the liquid crystal defect textures using optical polarizing microscopy at controlled temperatures. Textures of liquid crystal phases of monomer and homopolymer 1 (HP1) were analyzed by optical polarizing microscopy (OPM), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and through the construction of phase diagrams.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Poly(methylhydrosiloxane) (average Mn 1,700-3,200) and a solution of platinum divinyl tetramethyl disiloxane complexs, with a platinum concentration of 2.5-5 wt% were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

All other starting materials come from Alfa Aesa, Manchester Organics, Fluorochem, and Apollo Scientific. All compounds purchased were used without further purification. TLC Thin layer chromatography was used TLC Silica gel 60 F254 Merck KGaA.

The degree of polymerization which written as is calculated by /, using the values obtained by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), where Mw is the weight average molecular weight of the polymer, and M0 is the molecular weight of the repeating unit or monomer. Molecular weight distribution, also called polydispersity, is calculated by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) as the value of /.

2.2. Methods

Column Chromatography: all purification by column chromatography utilized Fluorochem Ltd. Silica gel 60A 35-70-micron silica gel, and Fisher Scientific U.K Lilted general purpose low iron grade sand.

1H-NMR 400MHz, 13C-NMR 101MHz and 19F-NMR 377MHz were recorded on a Jeol JNM ECP400 spectrometer.

The thermal transitions were both investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and optical polarizing microscopy (OPM). OPM was performed using Olypus BX51 Polarizing Microscope equipped with a Linkam LTS350 heating stage. The DSC data is from a Perkin Elmer Differential Scanning Calorimeter DSC 4000, an aluminum reference pan has been used to load the reference and sample, the calibration material is standard indium. DSC results were normally quoted by the average values for the onset of the second heating and cooling curve, the heating rate, if not mentioned specifically, was at 10 ˚C/min.

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) was run on a 350A HT-GPC system, equipped with two VE-1122 solvent delivery pumps, a VE-7510 solvent degasser, a Vortex 430 autosampler, and the 350A HT detector module. Samples were passed through microfilters before measurement to remove gel. Disposable microfilters were from Whatman Puradisc 25 TF. 0.2 μm PTFE Membrane with Polypropylene Housing Diameter 25mm.

Elemental Analysis was collected from FISONS Instruments EA 1108 CHN and using software Eager Xperience for processing the data.

X-ray powder diffraction data were collected from samples mounted on zero-background silicon discs. A PANAlytical Empyrean diffractometer operating in Bragg-Brentano geometry with copper Kα1 (λ = 1.540546 Å) and a PIXEL detector was used for the data collection. Data were collected in the range 3°≤2𝜃 ≤ 30°.

Monomers were characterized by high resolution mass spectrometers. The samples were run on the Bruker maXis, a Hybrid Quadrupole / Atmospheric Pressure Ionization orthogonal accelerated Time-Of-Flight mass spectrometer.

The side chain liquid crystal polymers were characterized by NMR, gel permeation chromatography (GPC), differential scanning calorimetry, and optical polarizing microscopy.

2.3. Purification of polymers

As the amount of the monomers is always in excess in the polymer analogous reaction with the poly (methylhydrosiloxane backbone, and as the traces of monomers can strongly influence the phase transition of related polymers, it was necessary to remove the monomers and purify the polymers. Purification was achieved by repeated precipitation with methanol, after dissolving the polymer with minimum volumes of toluene. The removal of monomers was monitored by DOSY-NMR, and thin layer chromatography on silica with appropriate solvent combination.

2.4. Synthesis of monomers

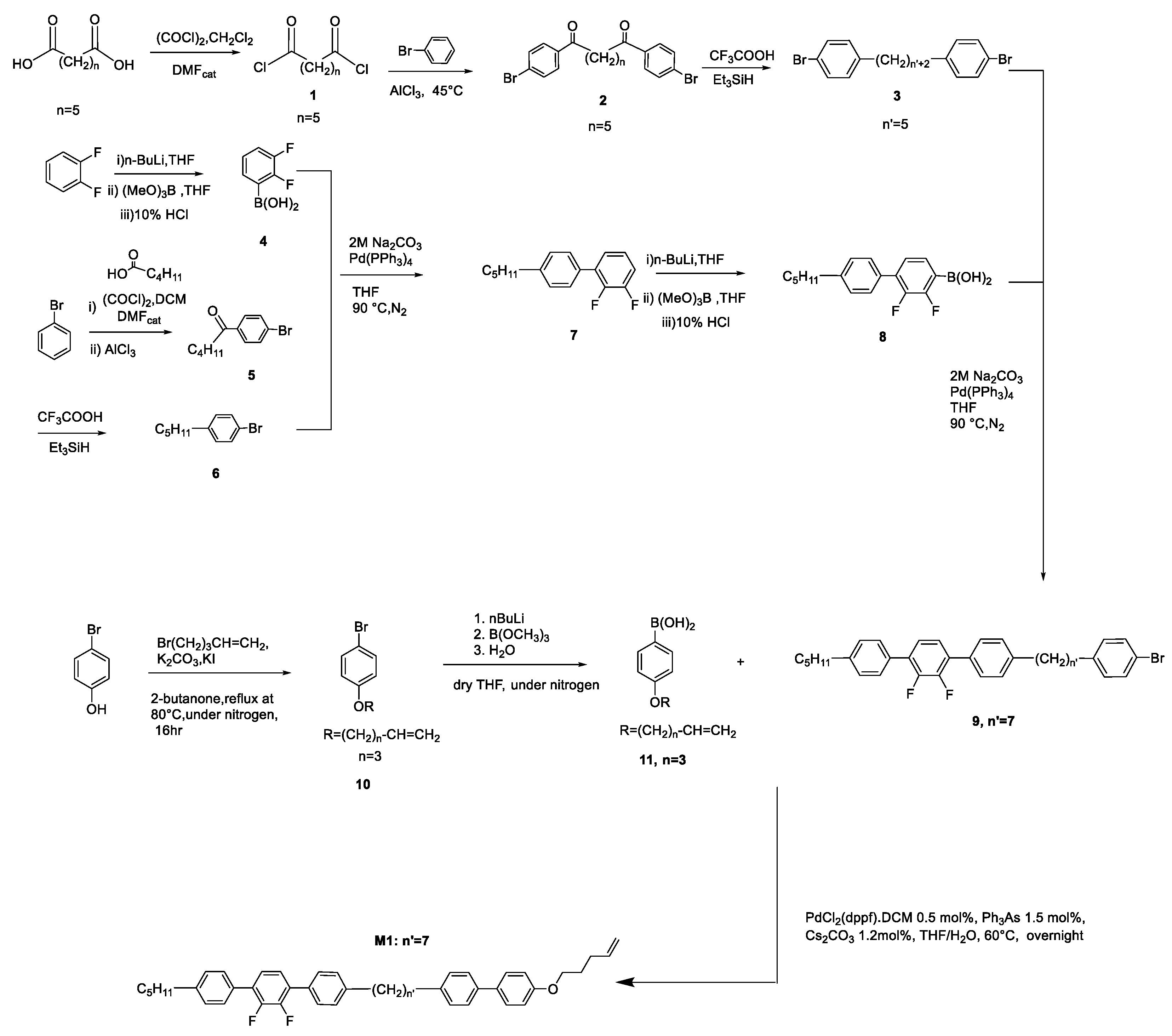

The synthesis route

used to prepare the vinylic monomer is

shown in Scheme 1. The monomer was synthesized in twelve step synthesis route, this was followed by the synthesis of the pentamethyldisiloxane derivative and the polymers.

The overall synthesis is based on a convergent approach. It starts with the conversion of heptanedioic acid to the related acid chloride

1 by using oxalyl chloride. The acid chloride reacts with bromobenzene through a Friedel-Crafts acylation reaction to obtain compound

2. The two keto groups were then reduced by a reaction with triethyl silane and trifluoroacetic acid to reach compound

3. Compound

3 was reacted with compound

8, which was obtained in a separate reaction pathway published earlier on [

19]. To make compound

8, the synthesis was based on another convergent synthesis route. After the reaction of 1,2-difluorobenzene with n-butyllithium, following by reaction with trimethyl borate, the boronic acid intermediate

4 was obtained. This was reacted in a coupling reaction with compound

6. Compound

6 was obtained by reacting bromobenzene with oxalyl chloride and n-pentanoic acid in a Friedel-Crafts acylation, followed by reduction of the ketone group with triethylsilane and trifluoroacetic acid. The coupling of compound

4 and compound

6 resulted in compound

7, which was converted into a boronic acid by reacting first with n-butyllithium. This was followed by the reaction with trimethyl borate to form compound

8. Compound

3 and compound

8 were coupled to form compound

9. (Shown in

Scheme 1). The overall reaction pathway procedure towards this type of dimers has already been reported earlier and hence the chemical characterization will not be reported here again [

17,

18,

20]

Monomer M1 was synthesized through a Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction of compound 9 and compound 11. Compound 11 was prepared by a Williamson Etherification, followed by lithiation and a Miyaura coupling reaction.

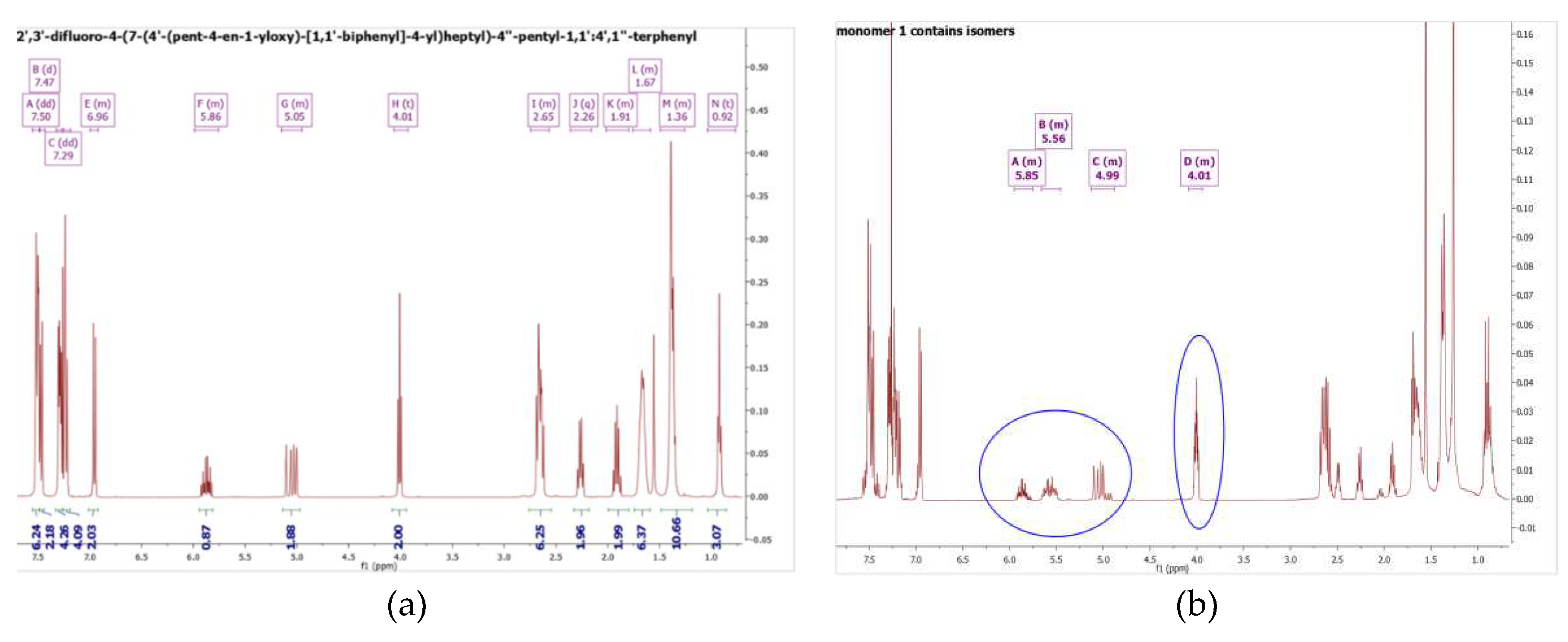

In this synthesis, for the preparation of the monomer, a cocatalyst was used in the Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling to eliminate the formation of isomers in the alkene chain of the hydrocarbon groups of the monomers. The occurrence of isomerization reactions was been discussed early on in 1993 [

21]. An alternative to produce isomer free products is to use P(Ph

3)

4 without cocatalyst. It was found that the main catalyst concentration cannot be higher than 0.5% mol to avoid isomerization of the terminal double bond (see

Figure 2(b)). However, in this procedure, the yield was only 15%, which is very low. Hence a [1,1’-Bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene] dichloropalladium (II) complex with a dichloromethane/ triphenyl arsine catalyst system was employed. The latter catalyst system was not only used to avoid formation of the isomers during coupling reaction, but also to help maintain the yield of the isolated product after column chromatography at higher than 50%. This is due to the bulky structure of the main catalyst formed together with the cocatalyst, suppressing the beta-hydride elimination reaction which produces isomers.

1HNMR results for the pure monomer are shown in

Figure 2 (a) and an example of an isomer formed during the initial exploratory work is shown in

Figure 2(b).

The

1HNMR (CDCl

3) spectra for

HP1 is virtually identical to the monomer

M1, the addition of the signals for the silyl protons at δ= 0.07 (48, s, Si-C

H3), δ= 0.86 (14,s, Si-C

H2) and the loss of signals for the vinylic protons at δ = 5.99 – 5.75 (1H, m, -C

H=CH

2), 5.15 – 4.95 (2H, m, -C

H=CH

2). See and below as the

1HNMR of monomer

M1 and polymer

HP1. As typical for polymers the signals are somewhat broaden when compared to the monomer. The synthesis of monomer 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile discussed later in this work and corresponding homopolymer has been reported in detail much earlier on [

22,

23].

Synthesis of the yet unreported steps for the preparation of M1.

2',3'-difluoro-4-(7-(4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl) heptyl)-4''-pentyl-1,1':4',1''-terphenyl M1

(2,3-difluoro-4-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy) phenyl) boronic acid 11 (0.11 g, 0.52 mmol) and 4-(7-(4-bromophenyl) heptyl)-2',3'-difluoro-4''-pentyl-1,1':4',1''-terphenyl 9 (0.32 g, 0.52 mmol), caesium carbonate was put in THF (50 mL) and water and the solution was degassed for 3 times. After that, the [1,1’-Bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene] dichloropalladium(II) complex with dichloromethane (2.12 mg, 0.5 mol%, 2.6 × 10-6 mmol) was added. This was followed by addition of triphenyl arsine (23 mg, 1.5 mol%, and 7.8 × 10-5 mmol), the stirred mixture was stirred at 60 ̊C overnight. The cooled mixture was poured into brine and the product was extracted into chloroform (3×30 mL). The combined organic layer was dried by anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude compound M1 was purified by column chromatography (DCM: Hexane= 1:4) and recrystallized from iso-propanol.

Yield: 0.18 g, 51.6 %

High Resolution Mass Spectroscopy: m/z 693.3883, err -0.4 ppm.

Elemental Analysis: Theoretical: C 84.14%; H 7.81%; Experimental: C 84.20 %; H 7.83%

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.50 (6H, dd, J = 6.5, 2.3 Hz), 7.47 (2H, d, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.29 (4H, dd, J = 8.1, 4.0 Hz), 7.23 (4H, t, J = 5.8 Hz), 6.99 – 6.92 (2H, m), 5.99 – 5.75 (1H, m), 5.15 – 4.95 (2H, m), 4.01 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz), 2.74 – 2.57 (6H, m), 2.26 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.02 – 1.80 (2H, m), 1.76 – 1.59 (6H, m), 1.49 – 1.26 (10H, m), 0.92 (3H, t, J = 6.7 Hz).

13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.53, 143.23, 143.15, 141.52, 138.34, 137.98, 133.75, 132.04, 129.61, 128.91,128.82, 128.07, 126.69, 124.73, 124.70,115.34, 114.86, 67.37, 35.84, 35.68, 31.71, 31.61, 31.49, 31.25, 30.28, 29.48, 29.36, 28.61, 22.71, 14.20

19F NMR (377 MHz, CDCl3): δ -143.21

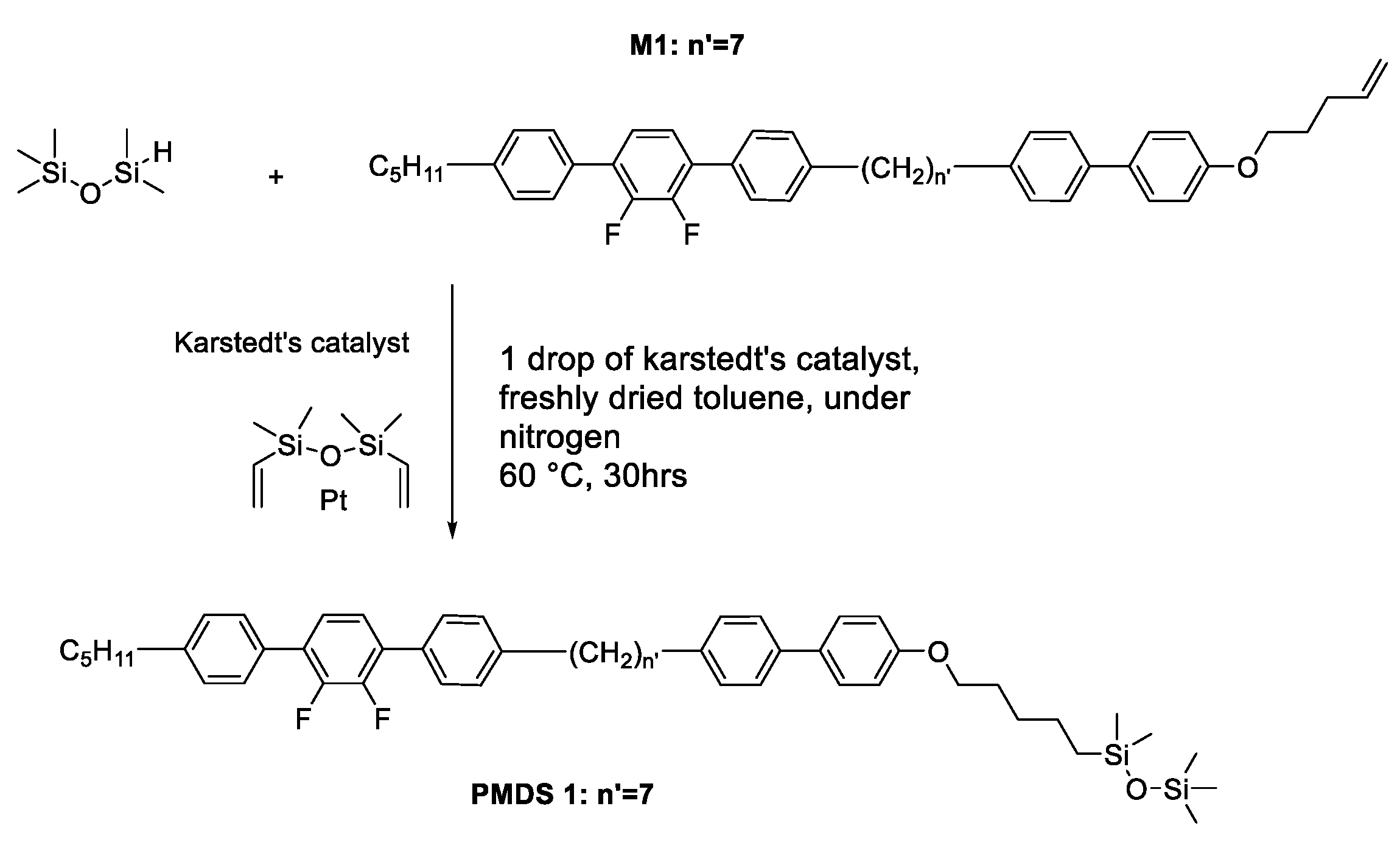

2.5. Synthesis of the pentamethyldisiloxane derivative (PMDS1)

The pentamethydisiloxane derivative was prepared by a platinum-catalyzed hydrosilylation, as shown in

Scheme 2.

After the hydrosilylation reaction with 1,1,1,3,3-pentamethyl-1,3-disiloxane and

M1, using Karstedt’s catalyst, the pentamethydisiloxane derivative

PMDS1 was obtained (see

Scheme 2). The synthesis is described in detail below:

1-(5-((4'-(7-(2',3'-difluoro-4''-pentyl-[1,1':4',1''-terphenyl]-4-yl) heptyl)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl) oxy) pentyl) -1,1,3,3,3-pentamethyldisiloxane PMDS 1

Monomer 2',3'-difluoro-4-(7-(4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl)heptyl)-4''-pentyl-1,1':4',1''-terphenyl M1 (0.17 g, 0.254 mmol) in anhydrous toluene (50mL) was stirred vigorously under nitrogen with 1,1,1,3,3-pentamethyldisiloxane (0.5 mL, 2.56 mmol) at 50°C for 3 days, using a Karstedt’s catalyst solution in xylene (Pt ˜2%) (0.5 mL, 0.0224 mmol) as the catalyst. The solvent was removed by vacuum and catalyst was removed by passing the dry crude through silica gel and washing it DCM. Silica gel column chromatography was used to further purify the crude (DCM/Petrol=1/2). After recrystallization by isopropanol, it was obtained as a white solid, yielding 67 mg, 32.4%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.54 – 7.43 (m, 8H), 7.32 – 7.26 (m, 4H), 7.23 (dd, J = 7.8, 5.0 Hz, 4H), 6.98 – 6.91 (m, 2H), 3.99 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.65 (dt, J = 12.6, 8.0 Hz, 6H), 1.87 – 1.75 (m, 1H), 1.66 (dd, J = 13.0, 7.2 Hz, 6H), 1.45 – 1.19 (m, 17H), 0.99 – 0.81 (m, 6H), 0.10 – 0.03 (m,12H).

(Carbon-fluorine-proton decoupled) 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.63,148.63,143.20,143.12,141.39,138.36,133.60, 132.11, 129.60, 128.89,128.85,128.81,128.03,126.66,124.68, 114.83, 68.16, 35.83, 35.68, 31.71, 31.61, 31.49, 31.25,29.88,29.49,29.21,28.37,23.29,22.71,22.64,18.46, 14.20, 2.14,1.18,0.51.

19FNMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ -143.12

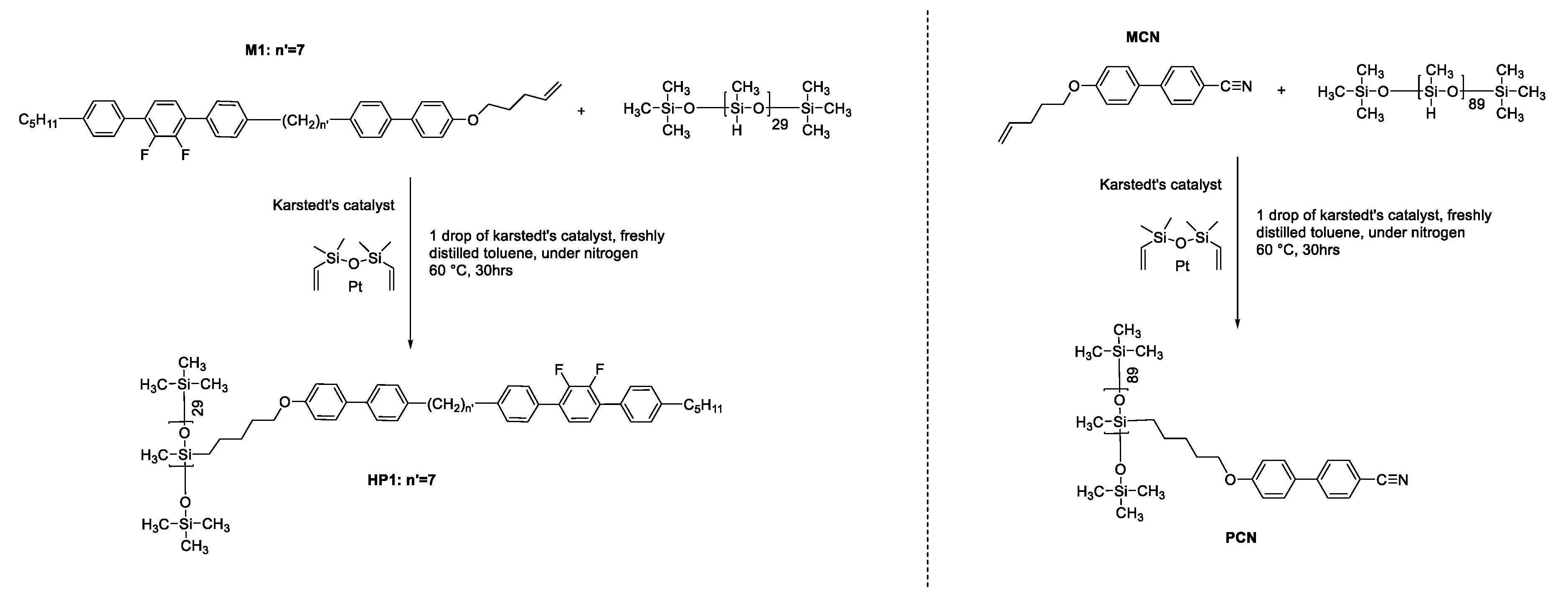

2.6. Synthesis of the homopolymers (HP1 and PCN)

After a hydrosilylation reaction with poly(methylhydrosiloxane) and

M1, using Karstedt’s catalyst,

HP 1 and

PCN were obtained. The synthesis is described in detail below, see

Scheme 3:

PCN

PCN has been reported earlier [

24,

25]. The phase transition was found to be: I-Sm

A 166.6 °C in this work, values which are very close to the transition range reported previously of I-Sm

A 169.5

[

24,

25].

The polymers were synthesized by hydrosilylation of the monomer 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (1.2 g, 4.56 mmol), and polymethylhydrosilane (Mn≈1700 ~3200, 0.228g, 3.8 mmol) using dry toluene as solvent with 2 drops of Karsted’s catalyst (Pt~2%) and the solutions were stirred at 60 °C for 3 days, whilst under an atmosphere of nitrogen. After the reaction was completed, further purification was carried out by repeated precipitation into methanol several times and the product was dried under vacuum.

Isolated yield: 0.25 g, 20.4 %

1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.47 (s, 14H), 7.25 – 7.00 (m, 8H), 6.84 (s, 4H), 3.86 (s, 4H), 2.63 (s, 7H), 1.61 (t, 26H), 0.90 (s, 4H), 0.59 (s, 4H), 0.09 (d, 19H).

The calculation of the yield is listed as below:

The siloxane unit is the repeating unit of the polymer backbone, at 60.1 g/mol in molecular weight. Therefore, 0.228 g of polymer backbone which, except for the end groups, consists of the repeating units of the siloxane unit. It can be assumed that the molar amounts were:

The molecular weight of repeating units of siloxane unit which contains 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile is 323.1 g/mol. The isolated yield of the polymer

PCN can be calculated as:

HP1

2',3'-difluoro-4-(7-(4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-yl)heptyl)-4''-pentyl-1,1':4',1''-terphenyl M1 (0.15g, 0.224 mmol) in dry toluene (30 ml) was stirred with polymethylhydrosilane (Mn≈1700 ~3200, 0.01g, 0.166 mmol) at 60 °C under nitrogen, then 1 drop of Karsted’s catalyst (Pt ~2%) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 days. After the reaction finished, purification was carried out by repeated precipitations into methanol and the product was dried under vacuum.

Yield: 0.031g, 25.6 %

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl

3): δ 7.46 (t, 9H), 7.22 (s, 7H), 6.80 (s, 2H), δ 3.84 (s,2H), 2.62 (s, 8H), 1.33 (s, 17H), 1.27 (d, 18H), 0.97 – 0.76 (m, 13H), 0.23 – 0.02 (m, 48H). Shown in

Figure 3.

The calculation of the yield is listed as below:

The siloxane unit is the repeating unit of the polymer backbone, at 60.1 g/mol in molecular weight. Therefore, 0.01g of polymer backbone which, except for the end groups, consists of the repeating units of the siloxane unit. It can be assumed that the molar amounts were:

The molecular weight of repeating units of the siloxane unit which contains monomer 1 is 730.4 g/mol. The isolated yield of the

HP1 can be calculated as:

2.7. Synthesis of the copolymer (CoP1)

After the hydrosilylation reaction with poly(methylhydrosiloxane) and

M1 using Karstedt’s catalyst,

CoP1 was obtained. The synthesis in details described below, see

Scheme 4:

CoP1

The polymers were synthesized by hydrosilylation of the monomer 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (1.2 g, 4.56 mmol), and polymethylhydrosilane (Mn≈1700 ~3200, 0.051g, 0.85 mmol) using dry toluene as solvent with 2 drops of Karsted’s catalyst (Pt~2%) and stirred at 60 °C for 3 days, while under an atmosphere of nitrogen. After the reaction was finished, further purification was carried out by repeated precipitation into methanol several times and the product was dried under vacuum.

Isolated yield: 0.102g, 21.2%.

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) solvent: δ 7.71 – 7.30 (m,6H), 6.84 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 2H), 1.75 (s, 2H), 1.45 (s, 4H), 0.57 (s, 2H), 0.07 (dd, J = 13.9, 8.0 Hz, 4H).

Calculation of the copolymer composition procedure is as below:

The calculation on the actual molar ratio of the monomers for the reaction is based on 1HNMR results:

The signal with the chemical shift at δ 3.86 ppm belongs to the -CH

2-O group, integration of which is 4. While the chemical shift above 6.5 ppm is associated with the phenyl ring protons, integration of which is 28. Assuming that there is x mol of 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile, and y mol of

M1. The calculation of each group of protons can be performed by integration of the

1HNMR signals.

Therefore, the actual mol ratio is (M1: MCN=1.2:0.8).

The siloxane unit is the repeating units of the polymer backbone, with a molecular weight of 60.1 g/mol. Therefore, 0.051g of poly(methylhydrosiloxane) consists of almost all the repeating units of siloxane backbone, and it can be assumed that the molar amount will be.

As the actual molar ratio of the monomers is (M1: MCN=1.2:0.8). The molecular weight of repeating units of siloxane unit which contains monomer 1 is 730.4 g/mol, whereas the compound containing monomer 4'-(pent-4-en-1-yloxy)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile is 323.13 g/mol.

0.102g = 1.2 a 730.40 + 0.8 a 323.13

Thus a= 0.09 ,

The isolated yield of the

CoP 1 can be calculated as:

The GPC results, indicate that the polydispersity is relatively narrow, and broadly like that of the polymer backbone, for the homopolymer and copolymer (see

Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the design approach.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the design approach.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route to monomer M1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route to monomer M1.

Figure 2.

a) 1HNMR of pure monomer M1 (b) 1HNMR of monomer M1 with isomers (isomer peaks highlight in blue circle).

Figure 2.

a) 1HNMR of pure monomer M1 (b) 1HNMR of monomer M1 with isomers (isomer peaks highlight in blue circle).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis route of pentamethydisiloxane PMDS 1.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis route of pentamethydisiloxane PMDS 1.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis route of homopolymer

HP1 and

PCN.

PCN has been previously reported [

24,

25].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis route of homopolymer

HP1 and

PCN.

PCN has been previously reported [

24,

25].

Figure 3.

HNMR of homopolymer HP1.

Figure 3.

HNMR of homopolymer HP1.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis route of homopolymer CoP 1.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis route of homopolymer CoP 1.

Figure 4.

OPM of monomer M1, the scale bar is 105μm. (a) nematic phase at 112 (b) phase transition at 10 (top left is in Ntb phase, while bottom right is in N phase) (c) Ntb phase at 100 (d) Ntb phase at 100 after shearing (e) phase texture under gently shearing at 80 (f) homeotropic texture after shearing at 95

Figure 4.

OPM of monomer M1, the scale bar is 105μm. (a) nematic phase at 112 (b) phase transition at 10 (top left is in Ntb phase, while bottom right is in N phase) (c) Ntb phase at 100 (d) Ntb phase at 100 after shearing (e) phase texture under gently shearing at 80 (f) homeotropic texture after shearing at 95

Figure 5.

Textures measured by OPM of M1 at the 103 ℃ at different cooling rates. Top left is the Ntb phase, and bottom right is the nematic phase. (a) cooling rate at 10 0.1 ℃/min under 103 ℃ (b) cooling rate at 3 0.1 ℃/min under 103 ℃ (c) cooling rate at 0.1 ℃/min, under 103 ℃.

Figure 5.

Textures measured by OPM of M1 at the 103 ℃ at different cooling rates. Top left is the Ntb phase, and bottom right is the nematic phase. (a) cooling rate at 10 0.1 ℃/min under 103 ℃ (b) cooling rate at 3 0.1 ℃/min under 103 ℃ (c) cooling rate at 0.1 ℃/min, under 103 ℃.

Figure 6.

OPM of pentamethydisiloxane derivative PMDS1, the scale bar is 105μm. (a) A smectic phase emerges from the isotropic state. Bãtonet shapes at 1090.1 ℃ (b) SmA phase at 108 ℃ (c) SmX phase at 74 ℃.

Figure 6.

OPM of pentamethydisiloxane derivative PMDS1, the scale bar is 105μm. (a) A smectic phase emerges from the isotropic state. Bãtonet shapes at 1090.1 ℃ (b) SmA phase at 108 ℃ (c) SmX phase at 74 ℃.

Figure 7.

Structure of DTC5C7.

Figure 7.

Structure of DTC5C7.

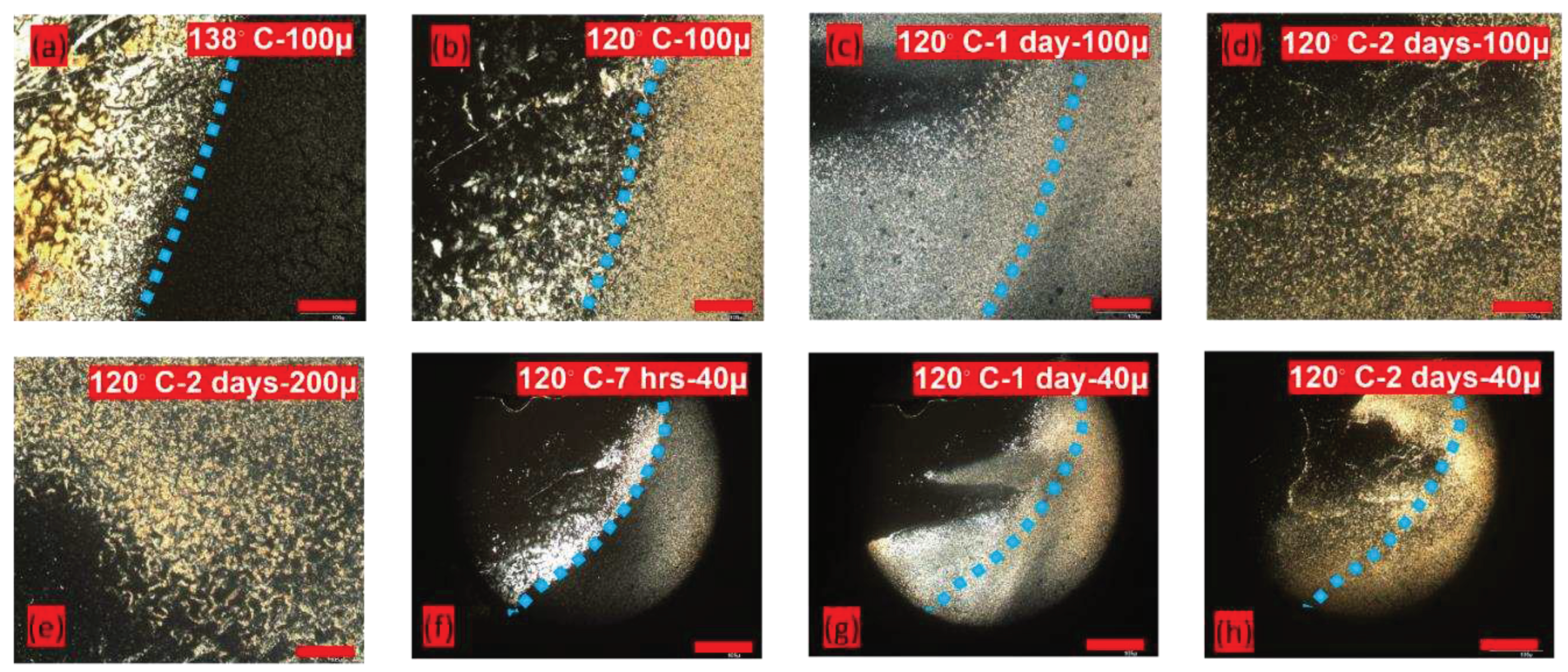

Figure 8.

Textures of the contact preparation HP1 with DTC5C7, displayed by optical polarization microscopy. The scale bar is 105 μm. Left side shows the texture of DTC5C7, right side the texture of HP1, blue dash line indicates the initial separation line (a) texture at 138, DTC5C7 at nematic phase on the left side (b) texture at 120, DTC5C7 in the Ntb phase on the left- side (c) texture at 120, after annealing for 1 day, both sides gradually merge (d),(e) textures at 120, after annealing for 2 days, more clear textures are formed (f) texture at 120, where DTC5C7 shows the Ntb phase in small magnification (g) texture at 120 after annealing for 1 days in a small magnification (h) texture at 120 after annealing for 2 days at a small magnification (x40).

Figure 8.

Textures of the contact preparation HP1 with DTC5C7, displayed by optical polarization microscopy. The scale bar is 105 μm. Left side shows the texture of DTC5C7, right side the texture of HP1, blue dash line indicates the initial separation line (a) texture at 138, DTC5C7 at nematic phase on the left side (b) texture at 120, DTC5C7 in the Ntb phase on the left- side (c) texture at 120, after annealing for 1 day, both sides gradually merge (d),(e) textures at 120, after annealing for 2 days, more clear textures are formed (f) texture at 120, where DTC5C7 shows the Ntb phase in small magnification (g) texture at 120 after annealing for 1 days in a small magnification (h) texture at 120 after annealing for 2 days at a small magnification (x40).

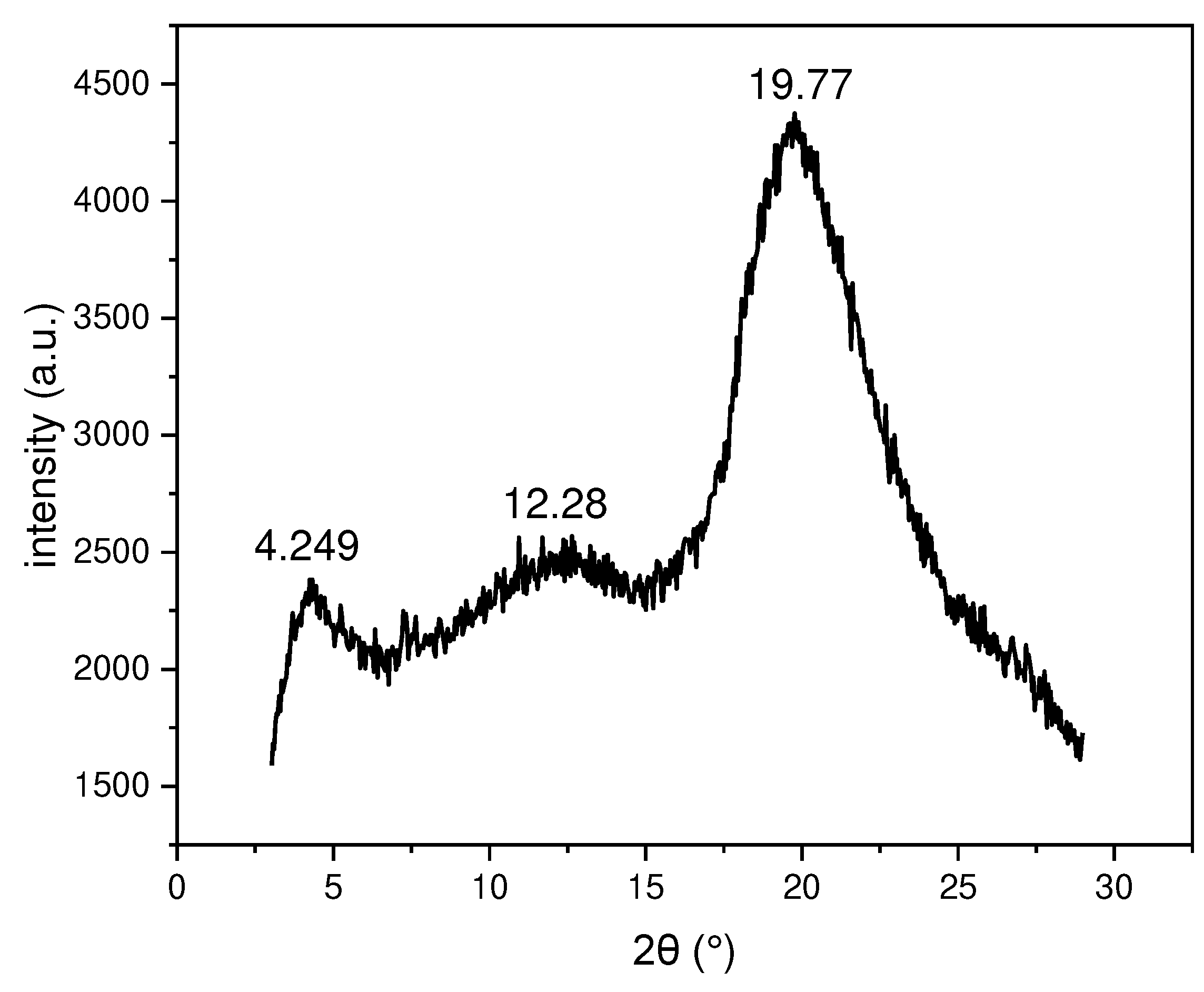

Figure 9.

Plot of 2𝜃 against intensity of the X-ray powder diffraction patterns at room temperature of copolymer1 (CoP1)

Figure 9.

Plot of 2𝜃 against intensity of the X-ray powder diffraction patterns at room temperature of copolymer1 (CoP1)

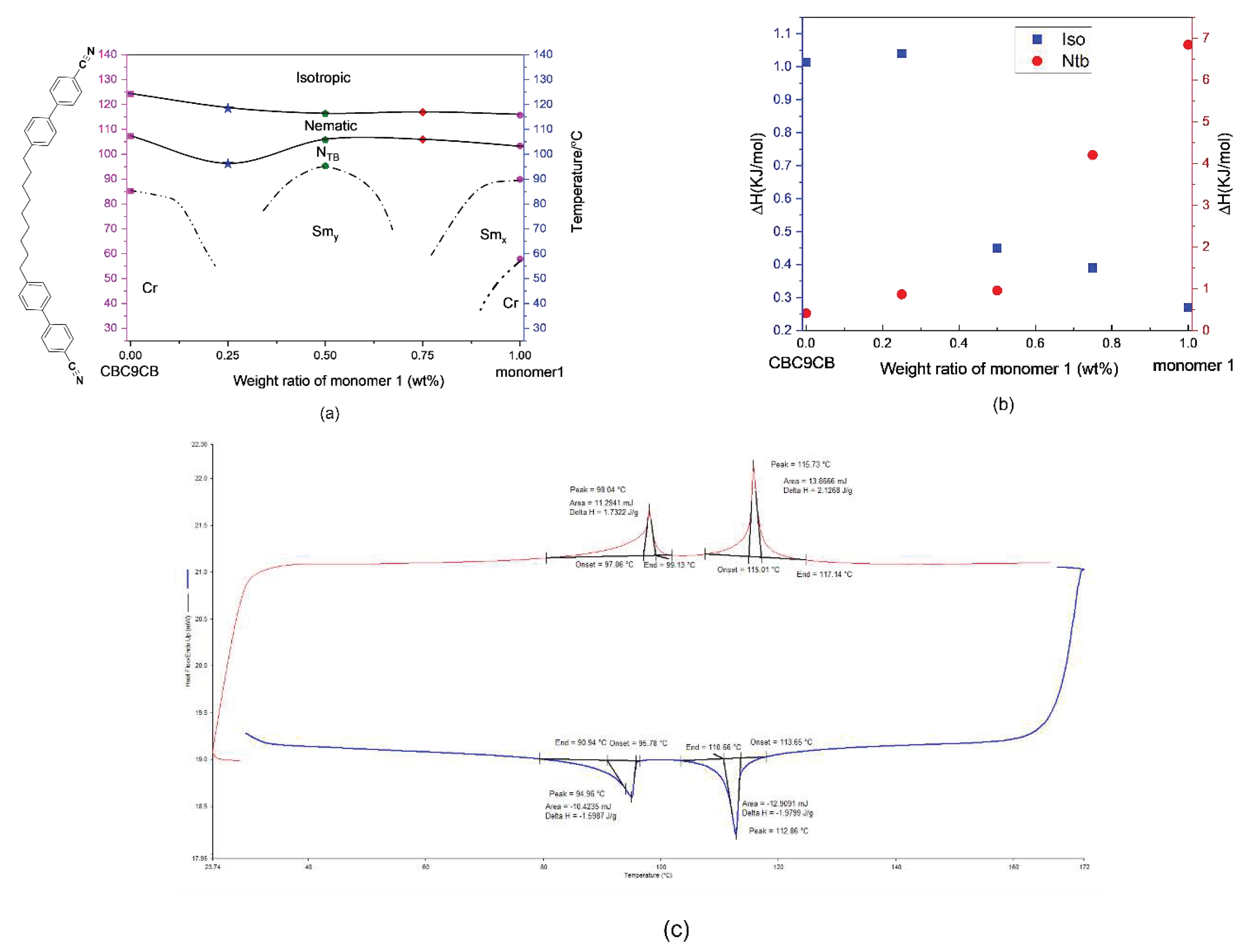

Figure 10.

a)Temperature concentration phase diagrams for the CBC9CB-M1 binary mixtures. Closed colorful symbols are used to denote the transition temperatures taken from the second cooling DSC run. Dash lines represent potential transitions unresolved by the DSC experiments. (b) Enthalpy values from the second cooling run of DSC as a function of concentration of monomer M1, for the Iso-N and N-Ntb phase of the CBC9CB -M1 binary mixtures. Red close circles for the N-Ntb enthalpy changes, while blue square represents the Iso-N enthalpies. (c) 2nd heating and cooling curve at 10℃/min result of a 25 wt% M1 and 75 wt% CBC9CB.

Figure 10.

a)Temperature concentration phase diagrams for the CBC9CB-M1 binary mixtures. Closed colorful symbols are used to denote the transition temperatures taken from the second cooling DSC run. Dash lines represent potential transitions unresolved by the DSC experiments. (b) Enthalpy values from the second cooling run of DSC as a function of concentration of monomer M1, for the Iso-N and N-Ntb phase of the CBC9CB -M1 binary mixtures. Red close circles for the N-Ntb enthalpy changes, while blue square represents the Iso-N enthalpies. (c) 2nd heating and cooling curve at 10℃/min result of a 25 wt% M1 and 75 wt% CBC9CB.

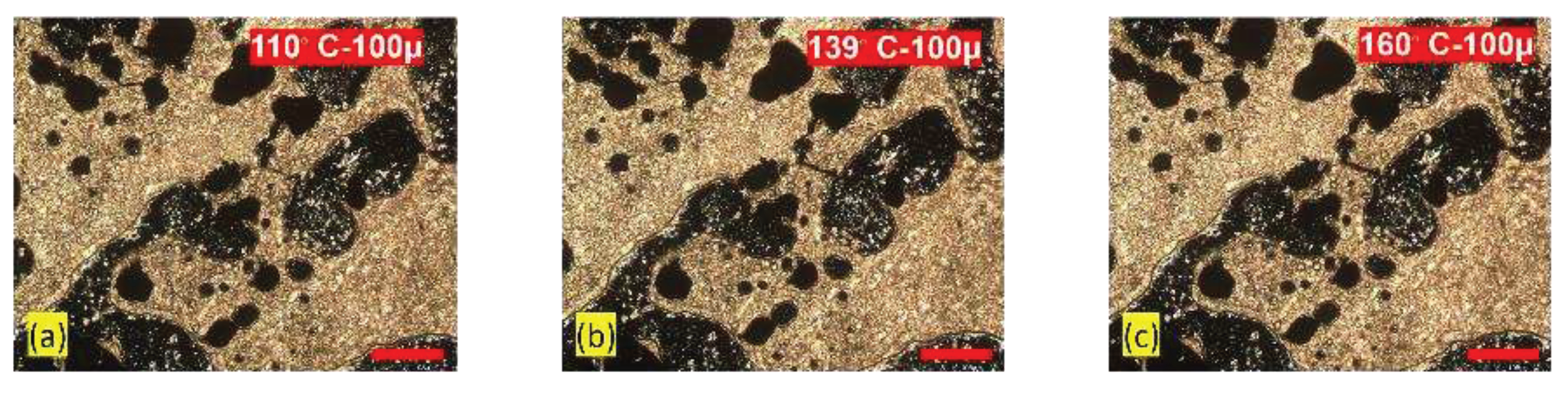

Figure 11.

Defec texture of homopolymer 1 (HP1), as by optical polarization microscopy. The scale bar is 105 μm (a) at 110 (b) at 139 (c) at 160

Figure 11.

Defec texture of homopolymer 1 (HP1), as by optical polarization microscopy. The scale bar is 105 μm (a) at 110 (b) at 139 (c) at 160

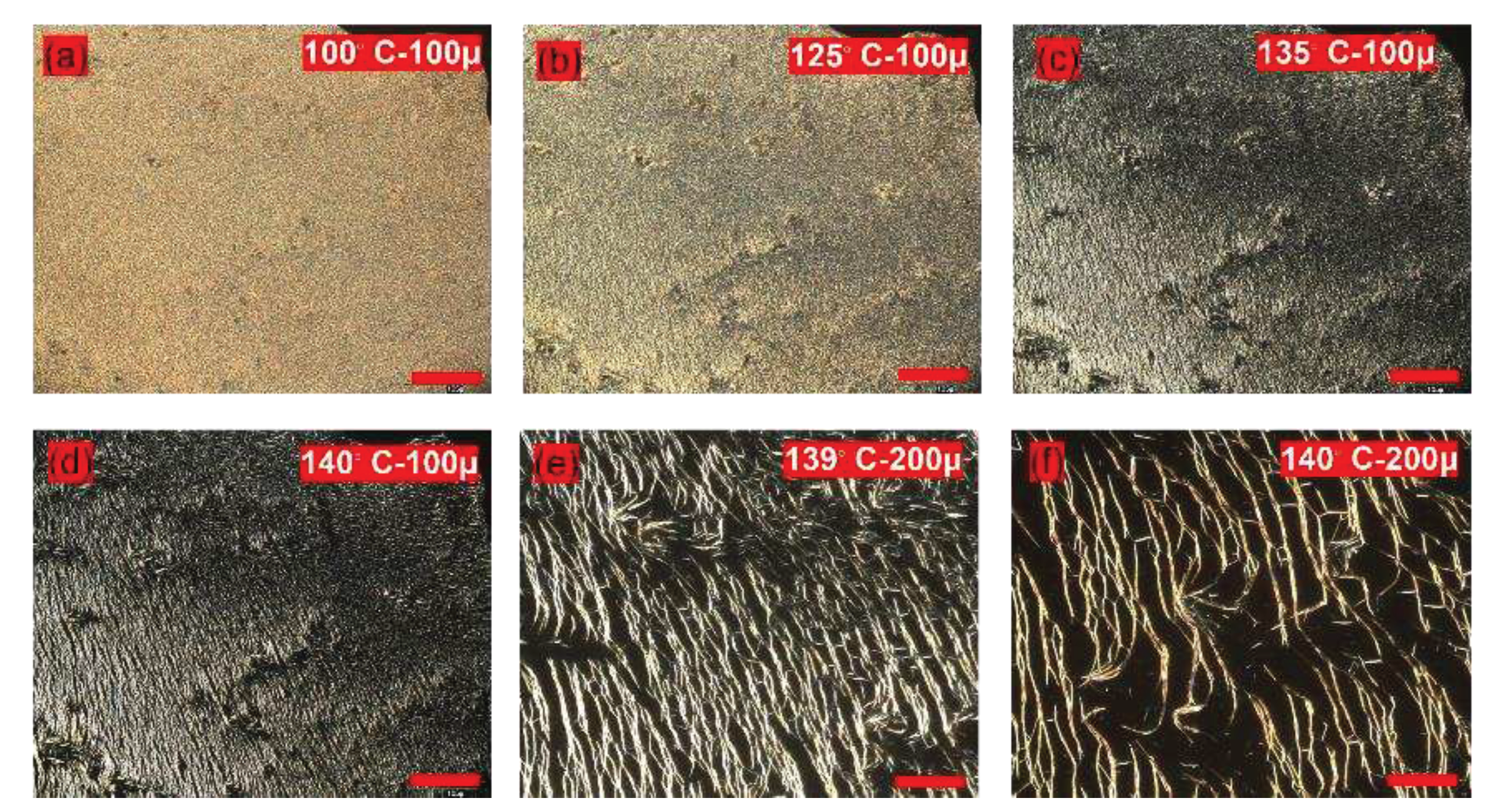

Figure 12.

Optical polarization microscopy displayed by flow contact of copolymer CoP1. The scale bar is 105μm. (a) Nx phase at 100℃ (b) Nx phase at 125℃ (c) Nx phase at 135℃ (d) Nx phase at 140℃ (e) Ntb phase in schlieren texture at 139℃ in 200u (f) Nx phase in schilren texture at 140℃ in 200u resolution.

Figure 12.

Optical polarization microscopy displayed by flow contact of copolymer CoP1. The scale bar is 105μm. (a) Nx phase at 100℃ (b) Nx phase at 125℃ (c) Nx phase at 135℃ (d) Nx phase at 140℃ (e) Ntb phase in schlieren texture at 139℃ in 200u (f) Nx phase in schilren texture at 140℃ in 200u resolution.

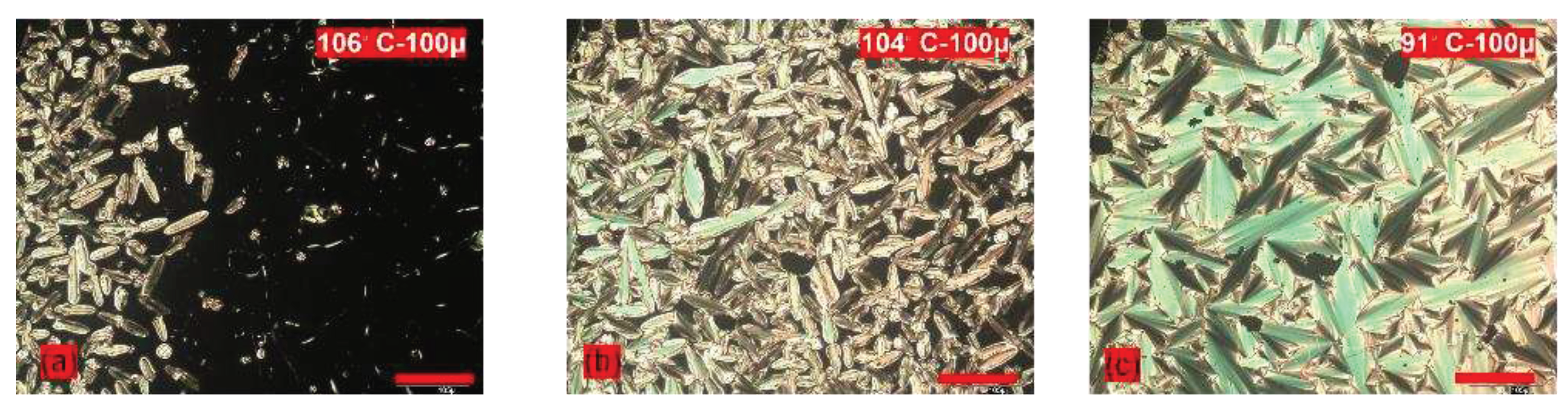

Figure 13.

Optical polarization microscopy of mixture of M1: MCN; molar ratio = 1.2: 0.8. The scale bar is 105μm. (a) phase transition from a nematic phase with a homeotrpic orientation to the SmA phase at 106℃ (b) SmA phase at 104℃ (c) SmA phase at 91℃.

Figure 13.

Optical polarization microscopy of mixture of M1: MCN; molar ratio = 1.2: 0.8. The scale bar is 105μm. (a) phase transition from a nematic phase with a homeotrpic orientation to the SmA phase at 106℃ (b) SmA phase at 104℃ (c) SmA phase at 91℃.

Table 1.

GPC results of polymers.

Table 1.

GPC results of polymers.

| Compound No |

GPC results |

weight average DP obtained by GPC |

Average molecular weight of repeating units |

|

|

/

|

/

|

| Polysiloxane backbone |

830 |

663 |

1.25 |

13.8 |

60.1 |

| HP1 |

21494 |

15441 |

1.39 |

29.4 |

730.4 |

| PCN |

28848 |

14212 |

2.0 |

89.3 |

323.1 |

|

CoP1 (M1: MCN=1.2: 0.8) |

22720 |

12778 |

1.8 |

40 |

567.5 |

Table 2.

Phase transition and phase transition enthalpies for monomer, pentamethyldisiloxane derivative, and polymers.

Table 2.

Phase transition and phase transition enthalpies for monomer, pentamethyldisiloxane derivative, and polymers.

| Compound No |

spacer length |

Fluorine numbers on mesogenic rings |

Transition temperature (using onset and offset of the peaks), measured by DSC at 10 /min, enthalpies unit (J/g) |

Highest LC -I temperature peak width d)

|

| M1 |

5 |

2 |

Cr 87.5 Ntb 101.5 (10.1) N 113.0 (0.51) I a)

|

3.81 |

| I 114.2 (-0.53) N 102.5 (-10.2) Ntb 90.6 (-3.6) Smx 59 Cr |

3.85 |

| MCN |

- |

- |

Cr 86.4 (93.7) I |

- |

| I 66.9 (-1.5) [N 49.3] Cr |

1.51 |

| PMDS 1 |

5 |

2 |

Cr 68.7 Smx 92.5 (1.79) SmA 110.5 (17.5) I |

2.36 |

| I 108.6 (-17.7) SmA 90.4 (-1) SmX 45.3 Cr |

2.48 |

| HP1 |

5 |

2 |

Cr 107.1 NX 182.9 (10.6) I |

32.76 |

| I 174.1 (-10.4) Nx 106.8 Cr |

29.62 |

| PCN |

5 |

0 |

SA 164.9 (5.2) I |

9.45 |

| I 166.6 (-5.3) SA

|

4.87 |

|

CoP1 (M1: MCN=1.2: 0.8) |

5 |

2 |

N 141.39 (7.01) I |

34.5 |

| I 148.3 (-5.9) N |

38.6 |

Table 3.

Summary of X-ray powder diffraction data of copolymer 1(CoP1) at room temperature.

Table 3.

Summary of X-ray powder diffraction data of copolymer 1(CoP1) at room temperature.

| 2 𝜃 (˚) |

d-value (Å) |

| 4.249 |

20.78 |

| 12.28 |

7.20 |

| 19.77 |

4.49 |