1. Introduction

Cloud manufacturing (CMfg) is an advanced service-oriented manufacturing model that uses different advanced internet technologies to integrate different virtualized manufacturing resources services [1, 2]. The topic has attracted lots of attention from scholars and practitioners. In CMfg, various lifecycle-oriented manufacturing resources and capabilities, including the hard and software capabilities for product design, production, simulation, transportation, and so on, are virtualized and encapsulated into CMfg platform [

3]. The characteristics of each MCS contain two categories including functional and non-functional attributes [

4]. The non-functional attributes are generally called as QoS. The deployed MCSs in the CMfg platform facilitate customers to select proper MCSs according to their requirements and QoS to complete manufacturing tasks [

5]. In detail, a complex manufacturing task can be split into different subtasks, which can be completed by selecting an MCS from the candidate manufacturing cloud service set (CMCSS) deployed in the CMfg platform, the selected MCSs are integrated to form a manufacturing cloud service composition (MCSC).

Large amounts of MCSs deployed in the CMfg platform with a rapid increase trend bring great challenges to select optimal MCSs. Numerous available candidate MCSs provide the same or analogous functions but have different QoS attributes, such as time, product performance, manufacturing capacity and so on. It is difficult to optimize some QoS attributes at the same time because one attribute may conflict with another. For example, a MCS may have a longer execution time but worse manufacturing capacity whereas another MCS may have a shorter execution time but better manufacturing capacity [

5]. Meanwhile, we also have to consider the issue of service correlations in the composition process that can influence the global QoS of the MCSC [

6]. The above particular problems of CMfg improve the difficulty of selecting MCSs to be composed of MCSC and is still a arduous task that attacked many researchers [

7].

The problem of QoS-MCSC is that each subtask of a cloud task select the suitable MCS to aggregate them in sequence to generate an MCSC. The MCSC can meet both functional requirements and optimal QoS of customers. Finding the optimal composite path from the feasible solutions distributed in a discrete space for QoS-MCSC is known as an NP-Hard problem. Various intelligent optimization algorithms have been developed to explore the optimal composite path for this problem, such as genetic algorithm (GA) [

8], differential evolution algorithm (DE) [

9], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [

10], artificial bee colony algorithm (ABC) [

11] and whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [

12]. Khanouchea et al. [

13] constructed a clustering-based search tree to improve global search capability for the problem QoS-MCSC. Li et al. [

14] proposed an hybrid PSO (AIWPSO) that utiliz adaptive inertia weights to enchance global search capabilities. Deng et al. [

15] developed a hybrid DE with neighborhood mutation operators and opposition-based learning (NOBLDE). Savsani et al. [

16] developed a teaching and learning (TLBO) for non-linear large scale problems. When solving the QoS-MCSC problem, there may be multiple local optimal solutions in the search space, and the above-mentioned approaches are easily trapped in local optimal solutions owing to their randomization or stochastic strategies. Achieving global optimal solutions is still a great challenge.

WOA, as a popular bionic algorithm, is proposed by Mirjalili [

12]. The principle of the WOA is to simulate the behavior of humpback whales in hunting prey, including encircling prey, bubble-net attacking, and searching for prey. Recently, WOA has aroused the interests of many researchers and practitioners, and it has been employed or modified to handle diversified practical engineering problems, such as multilevel threshold image segmentation [

17], permutation flow shop scheduling [

18], microgrid operations planning [

19], and so on. Experimental tests demonstrate that WOA can achieve competitive or better results compared to other heuristic algorithms. For instance, WOA outperforms the DE and grey wolf optimization (GWO) while solving the reactive power planning problems [

20]. However, one disadvantage of WOA is that it may easily drap into local optimization in the later iteration, especially when the number of evolution times exceeds 600 [

21]. The reason is that the probability related to exploration attenuates along with the iterations and the exploration ability of WOA for global optimal solution gradually decreases, while the exploitation ability gradually increases. Some existing algorithms also does not have a strong exploration ability in the later iteration, which might lead the approach to be trapped in the local optimal solution. Generally speaking, the stronger the exploration ability of algorithms, the superior the solution accuracy, especially for the NP-Hard problems.

Lévy flight is a type of generalized random walk algorithm that imitates the trajectory of biological activity [

22], and the direction of each step is completely random. Random direction search facilitates the exploration of the global optimal solution but is not conducive to algorithm convergence. Therefore, Lévy flight has always been integrated into other intelligent algorithms to improve the global search capability. For example, Liu et al. [

23] advances a hybrid approach by combining quantum particle swarm optimization with Lévy flight and straight flight strategy to solve engineering design optimization problems. Zhou et al. [

24] utilized Lévy flight to enhance the global optimization capability of ABC for the MCSC problem. Thus, Lévy flight is employed in WOA to enlarge the search space and increase the exploration capability.

Crossover is one of the essential operators used to preserve the population diversity of GA. Tradition crossover tries to alter a few parts of genes for each individual that is different from WOA which changes all the whale positions at the same time. This mechanism hinders the fast convergence of GA and causes the algorithm to easily fall into local optimal solution because traditional crossover is more inclined to generate similar individuals at the later iteration [

25]. Some studies reported that WOA outperforms GA with traditional crossover when solving MCSC problems [

26]. Thus, different adaptive crossover strategies have been developed to balance the exploration and exploitation ability. More competitive results have been achieved, such as an adaptive genetic algorithm for environment monitoring data acquisition [

27], a genetic algorithm adaptive homogeneous approach for identifying wall cracks problems [

28], adaptive dimensionality reduction GA for high-dimensional large-scale problems [

29] and so on. Inspired by these ideas, an adaptive crossover strategy is employed to balance the exploration and exploitation of WOA.

Adaptive weighting strategies are often developed to preserve population diversity and increase the search space of algorithms. In the exploitation of the standard WOA, whales can only surround prey in a small area, which causes whales to easily fall into local optimal solutions[

21]. Recently, more and more scholars use adaptive weights to optimize algorithms. For example, Li et al. [

14] introducted an AIWPSO, which has excellent global search capabilities. In order to classify underwater sonar images, Wang et al. [

30] introducted a new novel deep learning model that combine with adaptive weights convolutional neural network (AW-CNN). Cao et al. [

31] introducted an image classification algorithm based on adaptive feature weight for the low classification accuracy of the single-feature and multifeatured fusion. Inspired by these algorithms, the adaptive weight strategy is developed to extend the search scale of the exploitation phase.

The approach developed in this research that it uses WOA, adaptive crossover, adaptive weight, and Lévy flight strategies to improve the exploration and exploitation abilities cost-effectively. WOA performs well in exploitation with high convergence speed [

21]. The crossover strategies of GA has been widely adopted for population diversification preservation in real and integer coded optimization problems. Then, adaptive crossover with three crossover strategies and single point mutation is utilized to enhance the algorithm performance and accelerate the convergence of WOA. While Lévy flight is designed to enhance the exploration of WOA by expand the search space. Finally, an adaptive weight strategy is used to enhance the speed at which the whale approaches the prey. This study mainly consists of the following parts:

A novel WOA with adaptive crossover, adaptive weight and Lévy flight strategy (ASWOA) is proposed.

The Lévy flight strategy expands the soultion space and increases the exploration ability for global search.

The adaptive crossover balances the exploration and exploitation of WOA at different iterations and enhances the WOA to escape local optimal at the later iteration.

The adaptive weights are developed to accelerate the speed of approaching prey.

Simulation and comparison experiments conducted on different scale QoS-MCSC problems, which prove the superiority of the proposed ASWOA compared to standard WOA.

The rest is arranged as follows. The background of QoS-MCSC and the approaches for it are summarized in

Section 2. The model of QoTS-MCSC was introduces based on aggregation formulas in

Section 3.

Section 4 presents the proposed ASWOA and related techniques, including WOA, adaptive crossover, Lévy flight, and so on.

Section 5 gives simulation and comparison experiments. Finally,

Section 6 gives a summary and the future research direction.

2. Related work

CMfg is a popular research topic, relevant scholars have carried out a lot of researches on CMfg service modeling and description [

32], cloud architecture design [

33], cloud service standard [

34], and so on. In our previous study, a correlation-aware MCSC model was proposed. This model can describe the QoS dependency between different services [

6].

In recent years, cloud computing and big data advanced by leaps and bounds, and many manufacturing resources have been virtualized and encapsulated to be provided in the network platform, thereby leading to a rapidly and constantly expanding CMfg system. As the amount of MCS increases, how to select appropriate MCS efficiently to accomplish the functional requirements of corresponding manufacturing tasks and how to integrate these MCS into an MCSC with optimal QoS is the promising research issue [

35]. Many novel approaches have been developed to handle the problem of optimal selection of MCSC. There are three main methods to solve MCSC, including salarization-based, Pareto-based and other approaches.

The MCSC problem is considered a multi-objective problem (MOP) [

36]. The scalarization method can convert a MOP into a single-objective problem(SOP). At present, There are two scalarization methods: the fraction-based fitness technique and the simple additive weighting (SAW) technique [

37]. Based on fraction, Canfora et al. [

36] utilized GA to settle the MCSC problem. Based on SAW, Zhou [

38] proposed a hybrid TLBO for the MCSC problem. Mardukhi et al. [

39] proposed a new model, which can decompose global constraints into multiple local constraints. SKG A et al. [

40] have combined the WOA with the eagle strategy for QoS-MCSC problem Yue et al. [

41] developed a hybrid GA based on population diversity and relational matrix coding.

In addition to the declarative meta-heuristic algorithm mentioned above, non heuristic algorithms and heuristic algorithms are also used for MCSC problems. Liu et al. [

42] proposed an adaptive MCSC based on deep reinforcement learning. Jiang et al. [

43] introduced a top k query mechanism and proposed an Key-Path-Based Loose (KPL) algorithm. But, meta-heuristic algorithms have the most competitive performance for MCSC problems [

44].

Pareto is used to solve MOP problems and is to use multi-objective optimization and optimize multiple parameters of QoS at the same time to acquire the Pareto optimal explanation [

45]. Generally, there are some famous MOP methods. For example, Wahild et al. [

46] utilized the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm (SPEA-II) to solve the MOP problem. While Deb et al. [

47] utilized Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) for the MOP problem. Feng et al. [

48] proposed a new algorithm for MOP based on the combination of the idea of the Pareto solution, which was developed to address the SCOS problem. Rudziński et al. [

49] presented an application of generalized Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm (SPEA) with an original multi-objective optimization technique in the logistic facilities location problem. The proposed approach with purpose of seeking out a set of high spread and well-balanced distribution solutions in a specific solution space. Xie et al. [

50] introduced a new algorithm that uses the differential evolution mutation operator in directional guiding ideology and combines the NSGA-II algorithm to improve the solution population distribution. Napoli et al. [

51] proposed a trade-off negotiation strategy that can process multiple QoS properties at the same time. NK et al. [

52] developed Non-dominated Sorting GA (NSGA-II) for composition service problem in IoT. Suciu et al. [

53] introduced an adaptive MOEA/D algorithm for QoS-MCSC problems.

When multiple objectives need to be optimized, it means that the optimization problem becomes more complex, the efficiency of MOEAs will become lower and lower [

54]. In the algorithm execution stage, due to conflicts between different targets, multiple targets cannot be optimized at the same time. It is possible that one goal will be strengthened and another goal will inevitably be weakened. At the same time, the calculation amount of the above method based on Pareto optimization is much larger than that of the salinization method. Moreover, the above method based on Pareto optimization cannot be better to balance the exploration and exploitation.

Apart from the above two methods, many scholars use other methods to resolve this problem. Teixeira et al. [

55] introduced a new service-oriented model that can be conducted without necessarily implementing the real system. This can accomplish QoS tasks at a lower cost. Ping et al. [

56] proposed a new vague information decision model that alleviates the bias of existing approaches through the improved fuzzy ranking index. Zhang et al. [

57] proposed an intuitionistic fuzzy entropy weight BBO algorithm for QoS-MCSC problems. Hu et al. [

58] introduced a game-theoretic power control mechanism based on the hidden markov model (HMM).

In sum, using the above new model or Pareto to solve the MCSC problem has high computational complexity. After increasing the computational complexity, It may not be possible to obtain the global optimal QoS. Therefore, this article uses the salinization method to solve the QoS-MCSC problem.

3. Problem formulation of QoS-aware MCSC

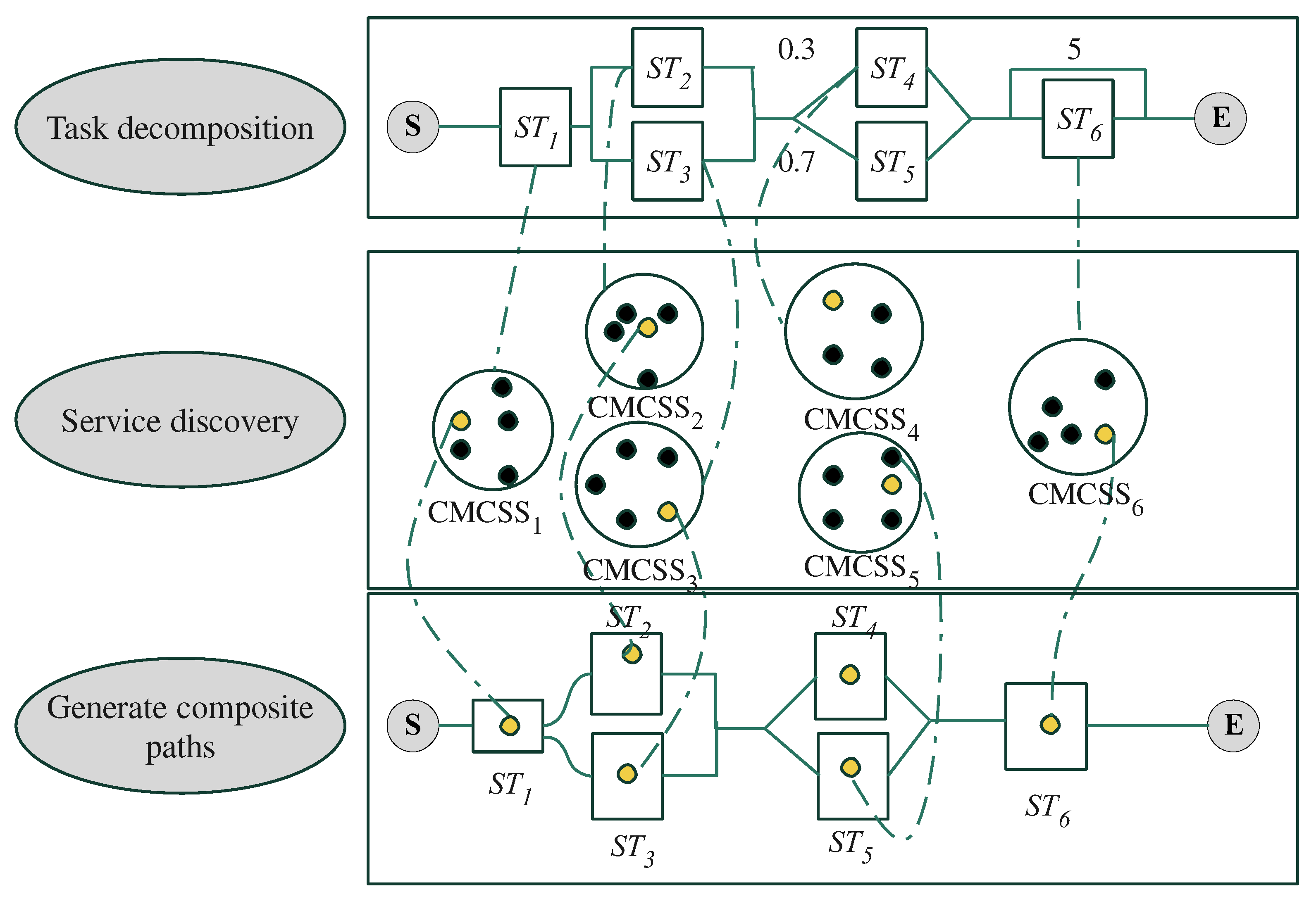

The composition of manufacturing service can be divided into task decomposition, service discovery, and service optimal selection three stages. This process can be illustrated in

Figure 1.

Task decomposition: the complex manufacturing task of the MCSC can be decomposed into multiple subtasks as Task = {ST1, ST2, ..., STi, ..., STn}, where STi represents the subtasks i, n is the total number of subtasks.

Service discovery: Each subtask STi has a candidate service set CMCSSi, CMCSSi = {, , , ..., ..., }, where represents the jth candidate service that can satisfy the functional and QoS constraints of subtask STi, mi represents the total number of MCS for STi.

Generate composite paths: a single MCS or a composition of multiple MCSs are selected for each subtask from CMCSS, and connected as an executable path CMSC. Pj = {, , , , ..., } is taken as the j executable path, and represents the candidate service of STi. Let P = {P1, P2, ..., Pi, ..., } representing the executable path space for task T and . QoS-Aware MCSC is to choose an optimal path from P with a high performance of QoS.

QoS, as the non-functional attribute of MCSC, is used to evaluate the performance of service. There are more than twenty QoS metrics in practical applications, and the four widely used QoS metrics including time (T), cost (C), reliability (R), and availability (A) are taken to construct the QoS evaluation model for MCSs in this study. These four metrics consider the balance of efficiency, economy, effectiveness, and stability of service that customers care about most. The QoS metrics of each MCS can be represented as {, C, , } where denotes the jth candidate MCSs for the ith subtask.

CMCS is composed of sequence, parallel, selective, and circular four types of composite structures. But parallel, selective and circular composite structures are not conducive to the QoS value calculation. Thus, it is necessary to convert the other three composite structures into a sequence structure, and then the QoS value of MCSC can be calculated by the sequential structure formula [

57]. The four structures of formulas are given in

Table 1.

The purpose of QoS-MCSC is to select the optimal combined path, and the global QoS value of each MCSC must be taken as the optimization goal. These QoS attributes are categorized into positive attributes (

) and negative attributes (

) two types. The optimization of QoS-MCSC tries to achieve high value positive QoS attributes, such as availability and reliability but low value of negative QoS attributes, such as time and cost simultaneously. The SAW is employed to convert multiple QoS attributes into a single value. The values of QoS attributes should be normalized in the same scale [0, 1] through SAW, and then conducts a weighted sum for each scaled QoS for aggregation. SAW-based QoS value of MCSC can be defined as the following formula:

where

and

indicates the max and min value of the

tth QoS attribute respectively,

wt is the weight value of each QoS attribute,

=1, and they can be determined by the preference of customers or the CMfg platform.

It is difficult to seek out the global solution for the QoS-MCSC because it has a large solution space. Taking a complex task with N subtasks and each subtask with M MCSs as an example, the solution space reaches up to MN. Thus, WOA with adaptive crossover, adaptive weight and Lévy flight strategies is developed to optimize this challenging problem in this study.

4. The proposed ASWOA for QoS-aware MCSC problem

4.1. Encoding for QoS-aware MCSC

A n-dimension real integer vector X = [x1, x2, ..., xi, ..., xn] is used to represent a solution for the QoS-aware MCSC with n subtasks, where xi is the index of MCS in the CMCSS for subtask i. The value of xi is bounded to be in the discrete range[1, mi], where mi is the number of available MCS for the ith subtask.

4.2. Whale optimization algorithm

WOA is a swarm intelligence algorithm that mimics whale hunting. Its hunting behavior includes three foraging behaviors: surround prey, bubble net attack, and hunt prey randomly [

12]. The mathematical model characterizing the three imitation operators is discussed in details in the following subsections.

Surround prey: Humpback whales can identify the location of nearby target prey and assume the location of the target prey as the best position among the current whales, and then humpback whales approach the prey by continuously updating their position. WOA presumes that the generated feasible solutions are ‘whales’ and takes the current best candidate solution or local optimal solution as ‘best position for prey encircling’. The operator of WOA that simulates the encircling prey shown as follows:

where ∙ is an element-by-element multiplication,

is the current best position of whale in the

tth iteration,

is the currently selected search whale,

denotes the distance between

and

, coefficient

and

are dynamic variables and can be updated by Equation (3) and Equation (4) respectively:

where

will decrease from 2 to 0 according to

with

as the maximum of iteration,

is a random vector in [0, 1]. The introduced random vector

limits the

in the range [-

]. And it is noteworthy that random vector

and

facilitates the whale to update their positions for optimal solution.

Bubble-net attacking: Humpback whales use bubble nets to push prey to the surface to catch them. The spiral bubble net attacking process formulas is as follows:

where

b is used to characterizing the logarithmic spiral shape,

l is a random number in [0, 1].

Hunt prey randomly: humpbacks randomly select a whale position and swim towards the position to explore new target prey while searching for prey. WOA simulates the process for global search using the following formula:

where

is the randomly selected whale position.

The selection of the three operators is determined by a random switch control parameter

in [0, 1] and the vector

is to determine the hunting method of the whale. We assume that the whale have a 50% probability to select bubble-net attacking for their position updating during solution exploitation, and the probability for the selection of operator search for prey or encircling prey is further determined by the adaptive variation of the vector

. The mathematical model for the operator selection can be defined as follows:

WOA takes

as a switch for the transition between exploration (

) and exploitation (

). However, exploration probability will gradually decrease as the number of iterations increases because

decreases as a whole according to its definition given in Equation (3) , which will lead it to be trapped into local optimal [

23].

4.3. WOA enhanced by Lévy flight

WOA renews the position of each individual according to another randomly selected individual in a small range in the standard WOA based on Equation (6) in the exploration phase for the prey, which limits the exploration space. Introducing the random walk mechanism of Lévy flight [

59] in Equation (6) to update position with occasionally long-distance leaps can expand the search scope and strengthen global search capability. The global search expression enhanced by Lévy flight used to update positions of humpback whales can be described as follows:

where

is a symbolic function with three options: -1, 0, or 1.

is a step parameter for distance

and is set to 0.05 in this study.

is the Lévy distribution to characterize the non-Gaussian random process, and the distribution can be expressed as the following formula:

the parameter

s and

is the step length of Lévy flight and index respectively. The

s can be defined by two normal distributions according to Manteca’s algorithm with the following formula:

where

is set to 1.5 in this study,

= 1 and.

4.4. Improved WOA enhanced by adaptive crossover strategies

The decrease of in Equation (7) as the number of iterations increases is not conducive to global search at the later iteration stage, which makes standard WOA not easy to escape the local optimum for global optimal solution exploration. The adaptive crossover with three position adjustment strategies is embedded in WOA. Most whales update their positions based on adaptive parameters, which can improve the position diversity of whale population at the later stage. The adaptive crossover strategies can increase information sharing among whale populations, and strength the capability of the global search in the later stage.

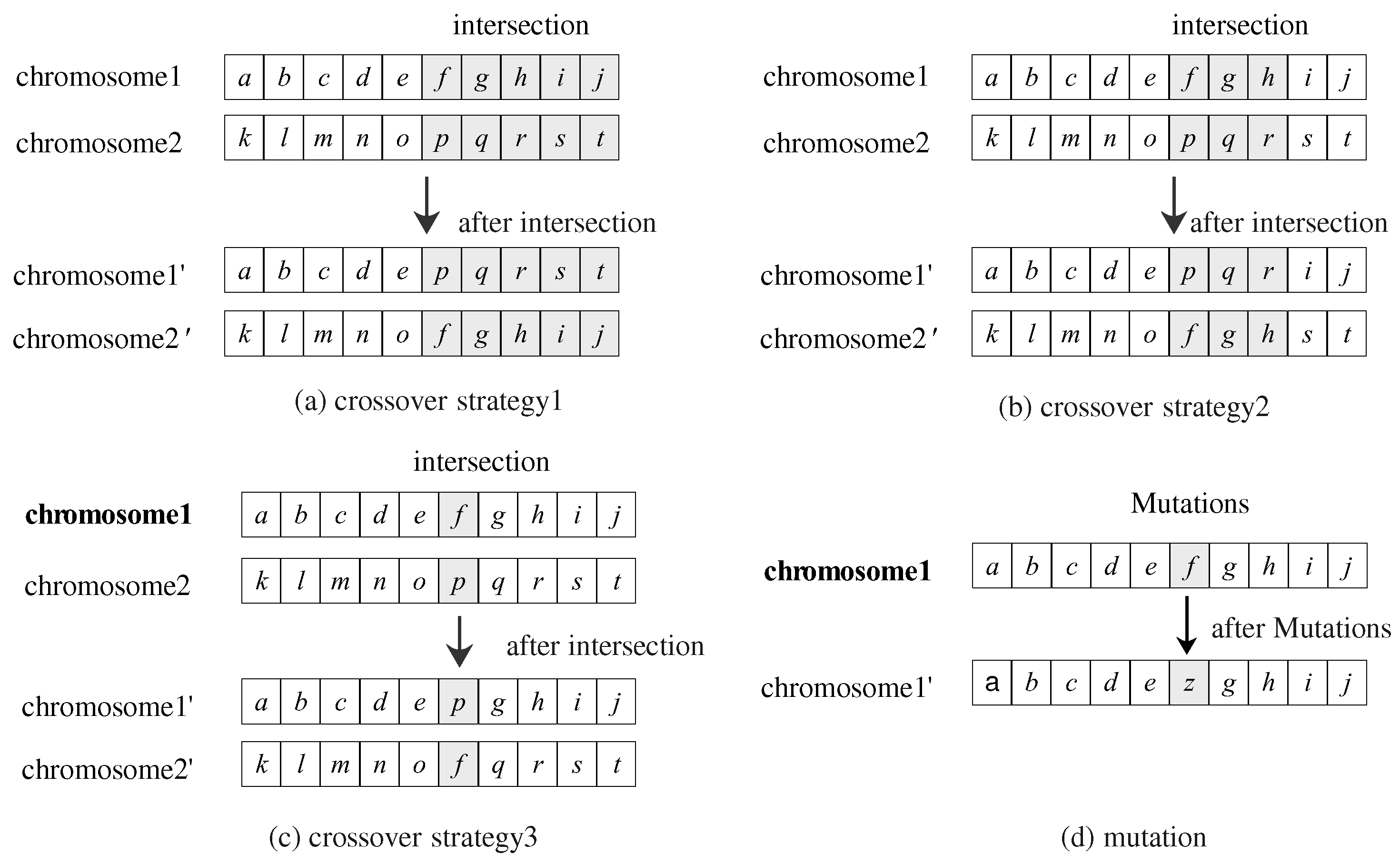

The three crossover strategies adopted to enhance WOA adaptively are suitable for real integer representation, thus they can operate the whale position vector denoting the feasible solution of standard WOA given in

Section 4.1 directly. The three crossover strategies include the multipoint crossover with one intersection point (

MCOIP), the multipoint crossover with two intersection points (

MCTIP), and the single point crossover (

SPC).

For

MCOIP, one intersection point is generated randomly for two search whale position vectors

P1 and

P2, the components behind the intersection point on

P1 will be exchanged with the corresponding components on

P2. While

MCTIP will generate two intersection points randomly for

P1 and

P2 and the components between the two intersection points on

P1 will be exchanged with the corresponding components on

P2; whereas

SPC only exchanges components on the intersection point for

P1 and

P2.

MCOIP and

MCOIP exchange many components for the two select search whales, which means changing candidate service for more subtasks, thus it is more suitable for preventing the whale population to become two similar at the later iteration stage.

SPC exchanges only one component for the selected search whale with a small disturbance for each individual, thus it is more suitable for whales with quite diverse positions at the early iteration stage. Therefore, a switch control parameter

Ap is designed to guide the algorithm to select the proper crossover strategy adaptively. The adaptive parameter

Pt can be formulated as follows:

where

t denotes the current number of iterations, maxiter is the maximum number of iterations, and the value of

Ap is in the range [

,1]. The selection of crossover strategy (Cs) based on the adaptive

Ap is defined by the following formula:

When the the value of

Ap is small while the value of

is large at the early stage of iteration, so ASWOA is more inclined to conduct global search by Equation (6), and the

SPC has the high priority to updating whale positions. ASWOA tends to conduct local search using Equation (2) and Equation (5), whereas Ap will increase and guide algorithm to select strategy

MCOIP or

MCTIP for exploration. The randomly generated number between (0, 1) for the selection of

MCOIP or

MCTIP is designed to further improve the randomness and diversity of whales. Different crossover strategies are shown in

Figure 2 below.

4.5. Improved WOA enhanced by adaptive weight strategies

The adaptive weight strategy is applied to preserve the population diversity [

14]. At the same time, the adaptive weight strategy can also strengthen the local search ability of WOA [

60]. Therefore, based on the above idea, this paper uses an adaptive weight strategy to increase the hunting range of the exploitation phase. The adaptive weight strategy

w is given by:

where maxiter is the maximum number of iterations of the algorithm. t is the iteration number of the current population. The value of w is in the range [0, 1], and the value of w will linearly decrease from 1 to 0. In the exploitation phase of WOA, the adaptive weight strategy is used to accelerate the speed of whales approaching the prey, so as to enhance the exploitation ability of the algorithm. In addition, the adaptive weights can also accelerate the convergence speed. According to the Equation (2) , WOA uses the following formula to update the position:

4.6. Proposed ASWOA

The Lévy flight strategy is introduced to expand the search space and increase the exploration ability for global search. The adaptive crossover is applied to balance the exploration and exploitation of WOA. At the same time, it enhances the ability of WOA to jump out of local optima in late iterations. The adaptive weight strategy is developed to expand the hunting range of the whale bubble net. The pseudo code of the ASWOA is given in Algorithm 1. The formula and notations in Algorithm 1 can refer to the above sections.

|

Algorithm 1: WOA enhanced with adaptive crossover and Lévy flight |

| 1: Initial population Xi (i = 1, 2, …, n), initialize crossover probability pc, flag=0 |

| 2: Calculate the fitness of all individuals according to Equation (1) |

| 3: Store the best solution as Xbest

|

| 4: while (t < tmax) |

| 5: for each search whale Xi in population |

| 6: Update a, C, A, p

|

| 7: if1 (p < 0.5) |

| 8: if2 (|A| < 1) |

| 9: // WOA enhanced by adaptive weight (Presented in Section 4.5) |

| 10: Update Xi by Equation (15) |

| 11: else if2

|

| 12: // WOA enhanced by Lévy flight (Presented in Section 4.3) |

| 13: Update Xi by Equation (8) |

| 14: end if2

|

| 15: else if1 (p >= 0.5) |

| 16: // Bubble-net attacking (Presented in Section 4.2) |

| 17: Update Xi by Equation (5) |

| 18: end if1

|

| 19: end for

|

| 20: flag = flag + 1 |

| 21: // Adaptive crossover phase (Presented in Section 4.4) |

| 22: if1 flag> population size/2 and rand > pc

|

| 23: Update adaptive parameters Ap by Equation (12) |

| 24: for i= 1: population size; i=i+2 |

| 25: if2 Ap > 0.5 |

| 26: if3 rand > 0.5 |

| 27: Conduct the MCOIP to update Xi and Xi+1 |

| 28: else if3 |

| 29: Conduct the MCTIP to update Xi and Xi+1

|

| 30: end if3

|

| 31: else if2 |

| 32: Conduct the SCP to update Xi and Xi+1

|

| 33: end if2

|

| 34: end for

|

| 35: flag = 0 |

| 36: end if1

|

| 37: Amend the updated positions that go beyond the search space |

| 38: Calculate the fitness of all individuals according to Equation (1) |

| 39: Update Xbest if there is a better solution |

| 40: t = t + 1 |

| 41: end while

|

| 42: output Xbest

|

5. Experiment results

The solution searching ability of the proposed ASWOA in QoS-aware MCSC problems is verified in a virtual application and is compared with the four cutting-edge algorithms WOA [

12], AIWPSO [

14], NOBLDE [

15], and TLBO [

16] for QoS-aware MCSC problems in this section. AIWPSO [

14] is modified from standard PSO, in which adaptive weight parameters and a mutation threshold have been introduced to increase the diversity of the population. NOBLDE [

15], as an improved DE, utilizes the neighborhood mutation operator and opposition-based learning to improve the exploration capability. TLBO [

16] is a swarm intelligence algorithm that simulates the traditional classroom teaching process including teacher stage and a learner stage. The parameter settings of the proposed ASWOA and the four comparative algorithms are presented in

Table 2, in which WOA [

12], AIWPSO [

14], NOBLDE [

15], and TLBO [

16] follow the original setting in the refereed articles. For all the approaches, the population size is 30, the maximum iterations is 1000. The experiments are implemented on a PC with operating system MAC(64 bit), CPU Intel i7-6500U 2.50GHz, RAM 16GB RAM, and MATLAB R2017a.

Four QoS attributes, including time, cost, reliability, and availability, for each MCSC are considered. And the values of the four attributes are randomly generated in the interval [0.7, 0.95]. It is assumed customers care more about time and cost and the weights of the difference QoS attributes are set as wtime=0.35, wcost=0.35, wreliability=0.15, and wavailability =0.15 according to the preference of customers. And the MCS correlation is 40%.

In this section, 16 experiments with different service scales were designed. The subtask sizes are 20, 30, 40 and 50 respectively. The candidate service sizes of each subtask are 50, 100, 150 and 200 respectively. For example, T-50-100 indicates that the subtask scale is 30 and the candidate service scale is 100.

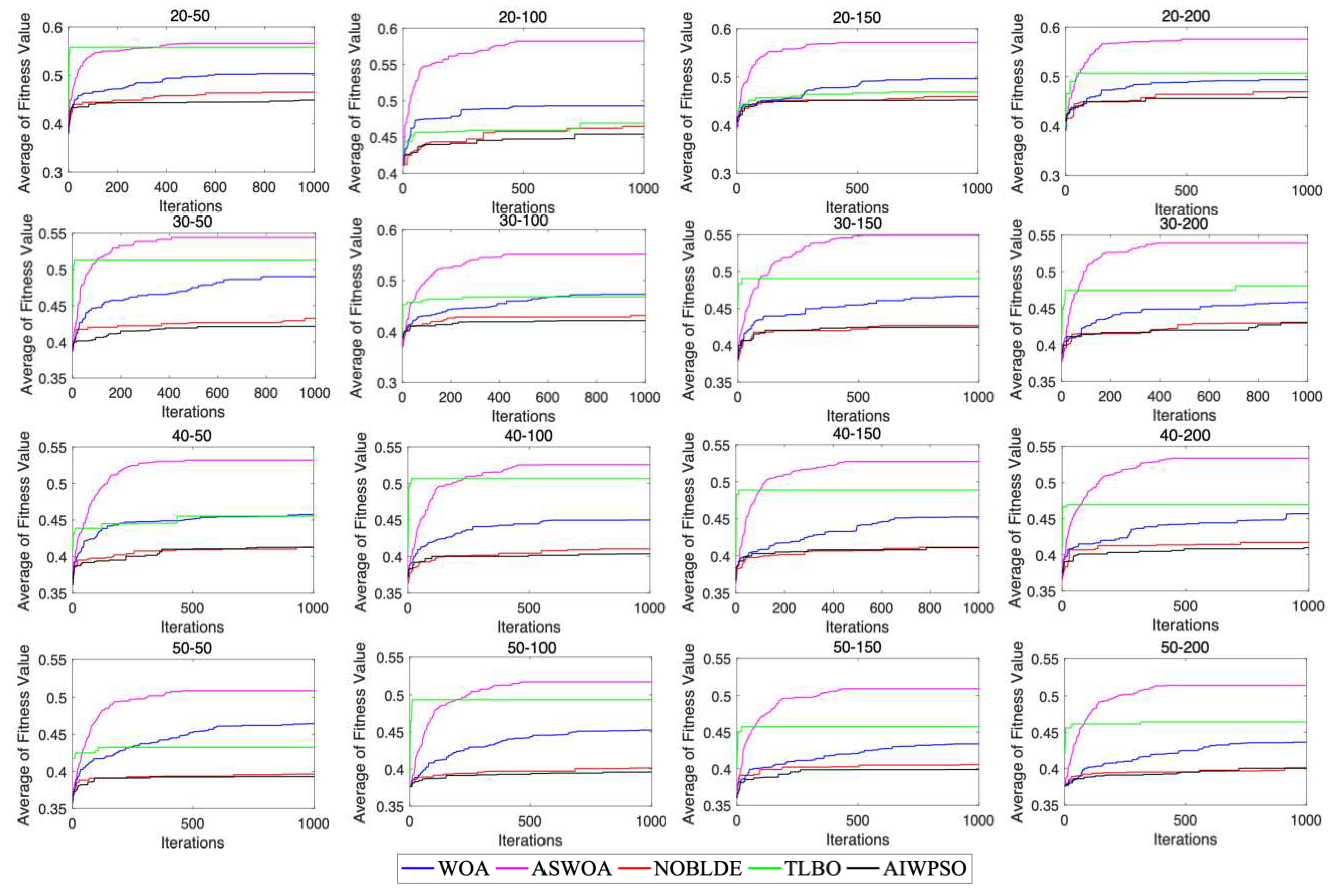

The results of WOA, AIWPSO, NOBLDE, and ASWOA on 16 test problems are given in

Table 3. Please note that ‘

Mean’, ‘

Std’, and ‘

Best’ indicate the average results, corresponding standard deviation, and best result of 30 executions with the best solution as its output in each run. It can be found that the ASWOA outperforms other compared algorithms for all the test problems according to the average QoS fitness values. Meanwhile, ASWOA obtains the best solutions in all cases based on the best QoS fitness values. It can be found that ASWOA has better robustness with lower ‘

Std’ than WOA, AIWPSO, NOBLDE, and TLBO, except for T-20-100, T-20-150, T-20-200, T-30-50, T-30-200, T-50-50, and T-50-100. The present ASWOA can hence robustly provide very good exploration not only for small scale QoS-aware problems but also large scale problems, thus it can be taken as an effective optimizer for the QoS-aware MCSC problem with different scales.

The convergence curves of the different scale QoS-MCSC problems have shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that the average value of ASWOA is better than WOA, TLBO, AIPSO, and NOBLDE in

Table 3. Meanwhile, The global optimal QoS value obtained by the ASWOA is also better than other compared algorithms.

According to the experimental results, The ASWOA uses adaptive crossover strategies and Lévy to enhance ASWOA global search capability. The ASWOA uses the Pt parameters to control crossover frequency to ensure the efficiency of the algorithm and uses the adaptive weight to expand the local search range. Through the above optimization, ASWOA has better convergence accuracy than WOA regardless of the convergence speed.

The execution time of the algorithm is shown in

Table 4. It can be seen that the solution time of ASWOA is longer than the WOA. This is because ASWOA strengthens the later global search capability through crossover-mutation while reducing the operation efficiency. But compared with product design, simulation, processing, transportation, and testing, these links can be ignored. Finding a better solution under the condition of slightly increasing the calculation time has higher cost performance for enterprises.

The execution time of the algorithm is shown in

Table 4. It can be seen that the solution time of ASWOA is longer than the WOA. This is because ASWOA strengthens the later global search capability through crossover-mutation while reducing the operation efficiency. But compared with product design, simulation, processing, transportation, and testing, these links can be ignored. Finding a better solution under the condition of slightly increasing the calculation time has higher cost performance for enterprises.

In summary, the ASWOA can effectively balance local search and global search.The advanced exploration of ASWOA is due to the Pt controlling the crossover strategy. The algorithm can select different crossover strategies according to Pt. At the same time, it not only strengthen the global search ability but also preserve the population diversity, which can avoid the algorithm dropping into a local optimization. Lévy distribution is applied to improve the exploration ability through expanding search space. The Adaptive weight is developed to expand the local search range. The experimental outcome shows that ASWOA has good performance in solving large-scale QoS-MCSC problems.

6. Conclusions

In order to resolve the QoS-MCSC problems as one of the key issue in CMfg, the ASWOA has proposed. In this paper, the adaptive crossover, adaptive weight, and Lévy flight strategies were introduced to better balance global search and local search for QoS-MCSC problems. In the proposed method, the global exploration is improved by Levy Flight, which can expand the search space of the whale. The adaptive crossover are used to strength the exploitation ability, which can preserve the diversity of the population. At the same time, the adaptive weight is used to enhance the exploitation ability in the bubble net stage. The ASWOA is compared with other frontier algorithms in QoS-MCSC problems to verify the performance of ASWOA. The tested results have illustrated that the ASWOA outperforms the compared cutting-edge algorithms.

Even so, there is still a limitation in execution time when solving the QoS-MCSC problem. In the future, the other versions of ASWOA are going to be developed to solve this problem by combining reinforcement learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. J. and C. J.; methodology, H. J.; software, H. J. and C. J.; validation, H. J., C. J. and S. L.; formal analysis, S. L.; investigation, H. J. ; data curation, C. J.; writing—original draft preparation, H. J. and C. J.; writing—review and editing, H. J. and S. L.; visualization, S. L.; project administration, H. J.; funding acquisition, H. J. and S. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, B.H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.L. Cloud manufacturing: a new service-oriented networked manufacturing model. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2010, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, L.; Venkatesh, V.C.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, Y. Cloud manufacturing: a computing and service- oriented manufacturing model. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B-J. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 225, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavvala, S.K.; Jatoth,C. ; Gangadharan, G.R.; Buyya, R. QoS-aware cloud service composition using eagle strategy. Futur. Gener. Comp. Syst. 2019, 90, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhi, A.; Fortineau, V.; Huet, J.C.; Lamouri, S. Ontology for cloud manufacturing based product lifecycle management. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 30, 2171–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, L.D.; Zhang, L.; Li, B.H. CCIoT-CMfg: cloud computing and internet of things-based cloud manufacturing service system. J. Intell. Manuf. 2014, 10, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Yao, X.F.; Chen, Y. Correlation-aware QoS modeling and manufacturing cloud service composition. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 28, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; Ji, Y.J.; Yu, S.Q. Data mining based multi-level aggregate service planning for cloud manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, G.Q.; Yi, L.L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, W.S. Genetic algorithm-based fast real-time automatic mode-locked fiber laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2019, 32, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Wang, Y.N.; Yuan, X.F.; Chen, Z.L. Multiobjective optimization of HEV fuel economy and emissions using the self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm. IEEE T. Veh. Technol. 2011, 60, 2458–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.I.; George, A.D.; Haftka, R.T.; Fregly, B.J. Parallel asynchronous particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2006, 67, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Akay, B. A comparative study of artificial bee colony algorithm. Appl. Math. Comput. 2009, 214, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanouche, M.E.; Attal, F.; Amirat, Y.; Chibani, A.; Kerkar, M. Clustering-based and QoS-aware services composition algorithm for ambient intelligence. Inf. Sci. 2019, 482, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.D.; Zhong, N.; Lu, S.F. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm with adaptive inertia weights. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2019, 18, 833–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Shang, S.F.; Cai, X.; Zhao, H.M.; Song, Y.J.; Xu, J.J. An improved differential evolution algorithm and its application in optimization problem. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5277–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Vakharia, D.P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: an optimization method for continuous non-linear large scale problems. Inf. Sci. 2012, 183, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Bei, J.L.; Song, H.H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, P.L. A whale optimization algorithm with combined mutation and removing similarity for global optimization and multilevel thresholding image segmentation. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2023, 137, 110130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Luo, X.H.; Wu, L.Z. An improved whale optimization algorithm for locating critical slip surface of slopes. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2021, 157, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, S. Improved whale optimization algorithm for solving microgrid operations planning problems. Symmetry 2023, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Bhattacharyya, B. Optimal placement of TCSC and SVC for reactive power planning using whale optimization algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2017, 40, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Shi, B. A hybrid whale optimization algorithm based on modified differential evolution for global optimization problems. Appl. Intel. 2019, 49, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M.; Phillips, R.A.; Watkins, N.W.; Freeman, M.P.; Murphy, E.J.; Afanasyev, V.; Buldyrev, S.V.; da Luz, M.G.E.; Raposo, E.F.; Stanley, H.E.; Viswanathan, G.M. Revisiting Lévy flight search patterns of wandering albatrosses, bumblebees and deer. Nature 2007, 449, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wang, G.G.; Wang, L. LSFQPSO: quantum particle swarm optimization with optimal guided Lévy flight and straight flight for solving optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 4651–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Yao, X.F. Multi-objective hybrid artificial bee colony algorithm enhanced with Lévy flight and self-adaption for cloud manufacturing service composition. Appl. Intel. 2017, 47, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghir, F.; Khababa, A. A hybrid approach using genetic and fruit fly optimization algorithms for QoS-aware cloud service composition. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 29, 1773–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, S.Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. An adaptive genetic algorithm of adjusting sensor acquisition frequency. Sensors 2020, 20, 990–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberti, S.; Grillanda, N.; Mallardo, V.; Milani, G. A genetic algorithm adaptive homogeneous approach for evaluating settlement-induced cracks in masonry walls. Eng. Struct. 2020, 221, 111073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, T.; Hu, Z.; Xu, M. A genetic optimization algorithm based on adaptive dimensionality reduction. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiao, J.; Yin, J.W.; Zhao, W.S.; Han, X. Sun, B.X. Underwater sonar image classification using adaptive weights convolutional neural network. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 146, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.F.; Wang, M. , Li, Y.F.; Zhang, Q. Improved support vector machine classification algorithm based on adaptive feature weight updating in the Hadoop cluster environment. PloS One. 2019, 14, e0215136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.B.; Zhuang, P.; Yin, C. A metadata based manufacturing resource ontology modeling in cloud manufacturing systems. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, A.; Caiazzo, B.; Piccirillo, G.; Santini, S.; Murino, T. An IoT-based and cloud-assisted AI-driven monitoring platform for smart manufacturing: design architecture and experimental validation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2023, 34, 507–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hert, P.; Papakonstantinou, V.; Kamaraa, I. The cloud computing standard ISO/IEC 27018 through the lens of the EU legislation on data protection. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2016, 32, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhao, D.M.; Hu, Y.F.; Zhao, Z.D. Correlation-aware resource service composition and optimal-selection in manufacturing grid. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 201, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, G.; Penta, M.D.; Esposito, R.; Villani, M.L. An approach for QoS-aware service composition based on genetic algorithms. In Proceedings of the 7th annual conference on genetic and evolutionary computation, Washington DC, USA, 25-29 June 2005; pp. 1069–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.Z.; Benatallah, B.; Ngu, A.H.H.; Dumas, M.; Kalagnanam, J.; Chang, H. QoS-aware middleware for web services composition. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2004, 30, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Yao, X.F. Hybrid teaching–learning-based optimization of correlation-aware service composition in cloud manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 9, 3515–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardukhi, F.; Nematbakhsh, N.; Zamanifar, K.; Barati, A. QoS decomposition for service composition using genetic algorithm. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2013, 13, 3409–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavvala, S.K.; Jatoth, C.; Gangadharan, G.R.; Buyya, R. QoS-aware cloud service composition using eagle strategy. Futur. Gener. Comp. Syst. 2019, 90, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.W. Quick convergence of genetic algorithm for QoS-driven web service selection. Comput. Netw. 2008, 52, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Hu, L.Q.; Cai, Z.Q.; Xing, L.N.; Tan, X. Large-scale and adaptive service composition based on deep reinforcement learning. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2019, 65, 102687–102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hu, S.; Liu, Z. Top k query for QoS-aware automatic service composition. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2014, 7, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoth, C.; Gangadharan, G.R.; Buyya, R. Computational Intelligence based QoS-aware web service composition: a systematic literature review. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2017, 10, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burugari, V.K.; Periasamy, P.S. Multi QoS constrained data sharing using hybridized pareto-glowworm swarm optimization. Cluster Comput. 2019, 22, S9727–S9735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Gao, X.; Andreae, P. Multi-objective clustering ensemble for high-dimensional data based on Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm (SPEA-II). Proceedings of 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Science & Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Paris, France, 19-21 October 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Hu, Y.F.; Yu, Y.R.; Wu, H.C. QoS and energy consumption aware service composition and optimal-selection based on Pareto group leader algorithm in cloud manufacturing system. Cent. Europ. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 22, 663–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudziński, F. An application of generalized strength pareto evolutionary algorithm for finding a set of non-dominated solutions with high-spread and well-balanced distribution in the logistics facility location problem. Proceedings of International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing, Zakopane, Poland, 11-15 June 2017; pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Gadhvi, B.; Savsani, V.; Patel, V. Multi-objective optimization of vehicle passive suspension system using NSGA-II, SPEA2 and PESA-II. Procedia Technol. 2016, 23, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.D.; Rossi, S.A. Trade-off negotiation strategy for pareto-optimal service composition with additive QoS-constraints. Group Decis. Negot. 2021, 30, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, N.; Kumari, A.C.; Chhikara, R. Multi-objective optimization using NSGA II for service composition in IoT. Procedia Comput. S. 2020, 167, 1928–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, S.C.; Denis, P.; Marcel, C.; Dumitru, D. Adaptive MOEA/D for QoS-based web service composition. Proceedings of European Conference on Evolutionary Computation in Combinatorial Optimization, Vienna, Austria, 3-5 April 2013; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A.; Parejo, J.A.; Romero, J.R.; Segura, S.; Ruiz-Cortes, A. Evolutionary composition of QoS-aware web services: a many-objective perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 72, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.; Ribeiro, R.; Oliveira, C.; Massa, R. A quality-driven approach for resources planning in service-oriented architectures. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 5366–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, W. QoS-aware web services selection with intuitionistic fuzzy set under consumer's vague perception. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 4460–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, W.Y.; Yu, D.J.; Chen, K. A hybrid approach combining an extended BBO algorithm with an intuitionistic fuzzy entropy weight method for QoS-aware manufacturing service supply chain optimization. Neurocomputing 2017, 272, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yan, H.; Yan, T.; Geng, H.J.; Liu, G.Q. Evaluating QoE in VoIP networks with QoS mapping and machine learning algorithms. Neurocomputing 2020, 386, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ling, Y.; Luo, Q. Lévy flight trajectory-based whale optimization algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 6168–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.P.; Bai, Y.P.; Xu, T. A whale optimization algorithm with inertia weight. WSEAS Trans. Comput. 2016, 15, 319–326. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).