Submitted:

23 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sample Collection

2.2. Population study

2.3. Ethics Approvals

2.4. SARS-CoV-2 detection

2.5. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.6. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 Genotyping

2.7. Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL)

2.8. Statistical analysis

Results

General characteristics of the study subjects

ACE2 and TMPRSS2 SNP distribution in the Brazilian population

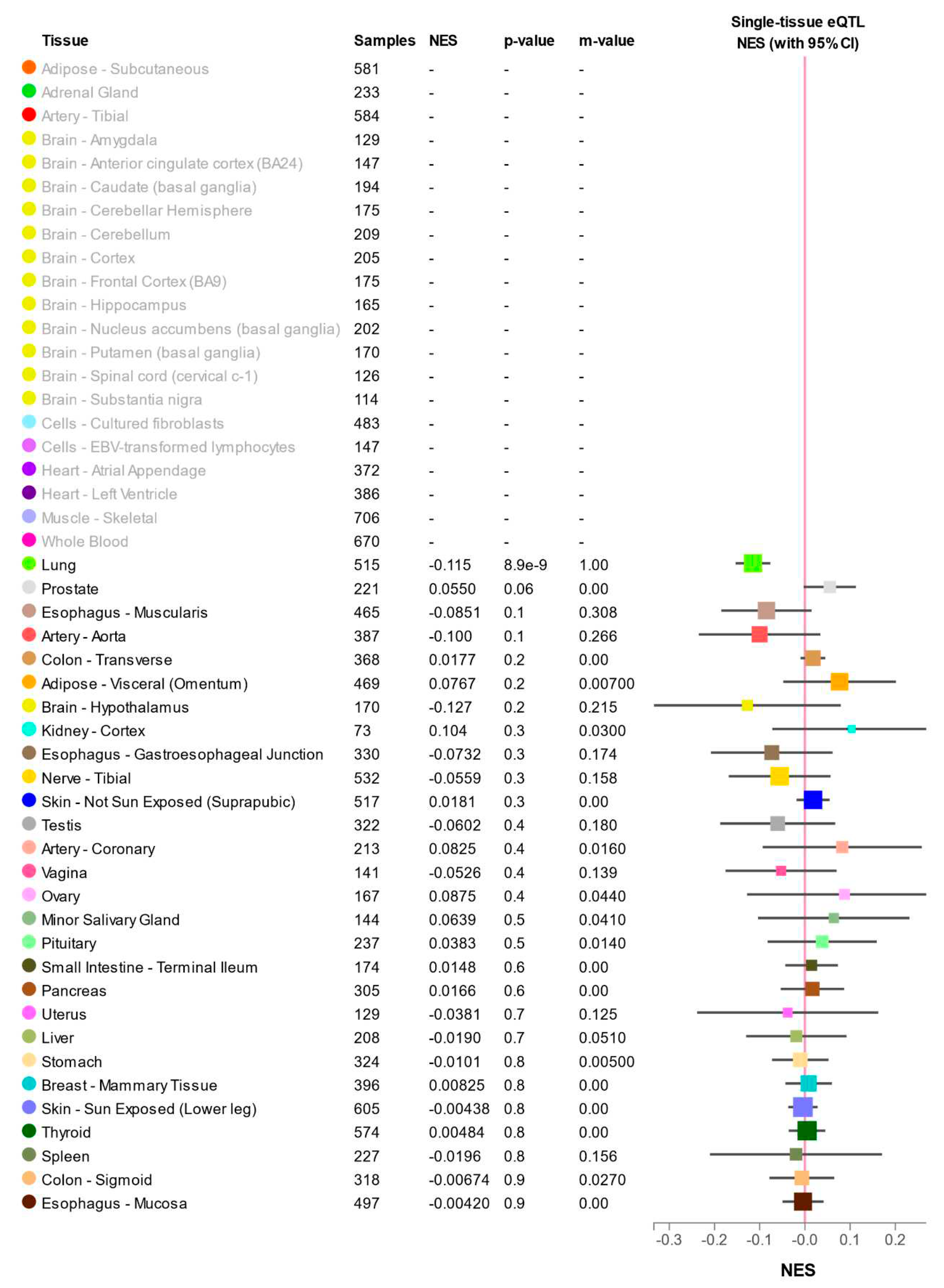

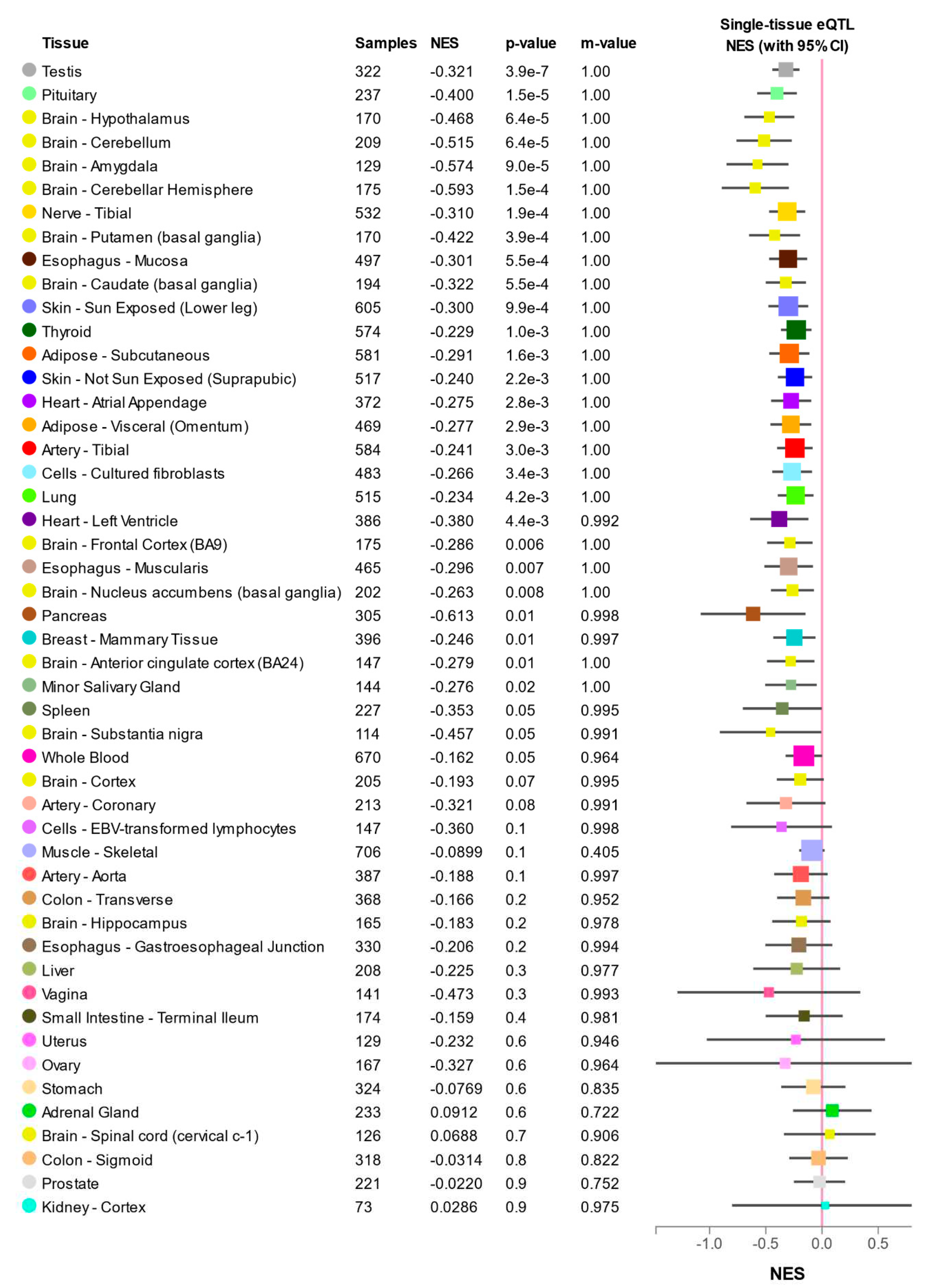

2.9. Expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL)

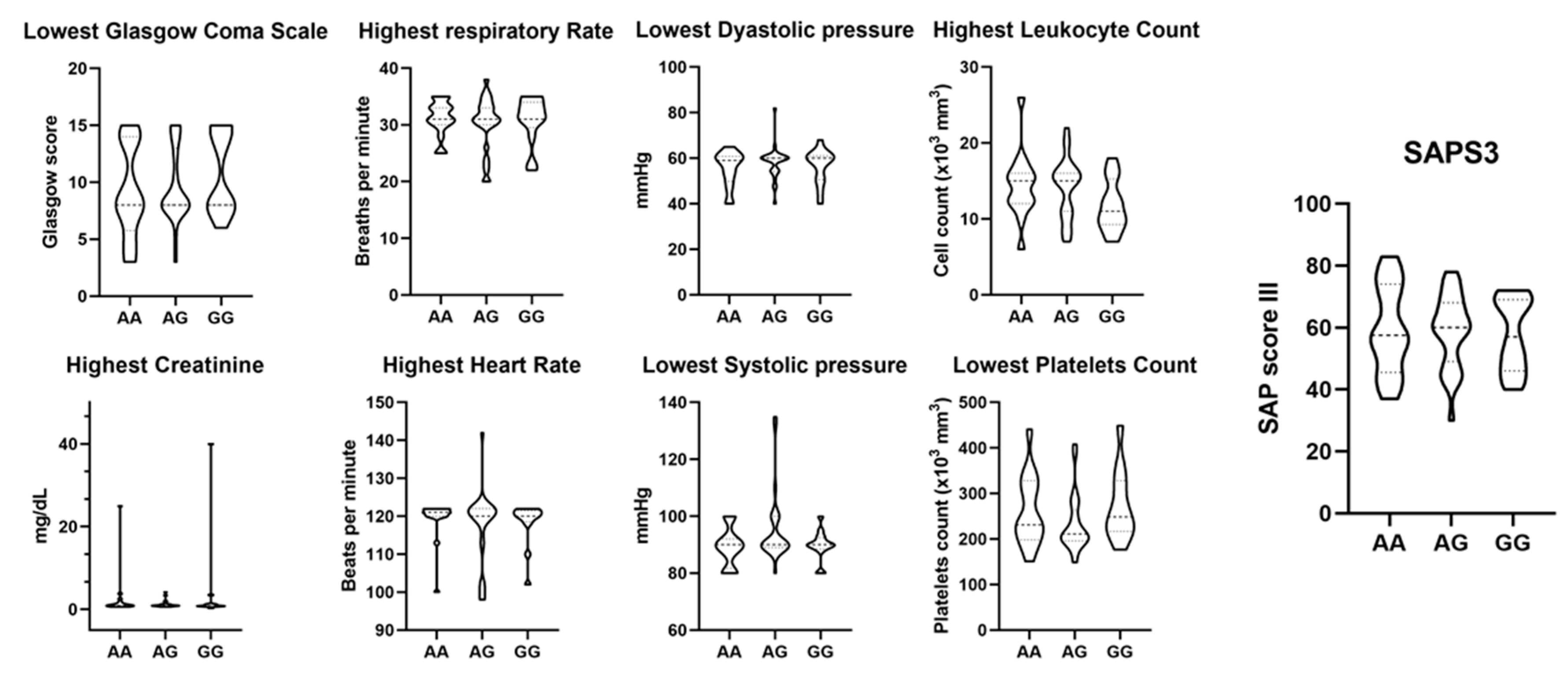

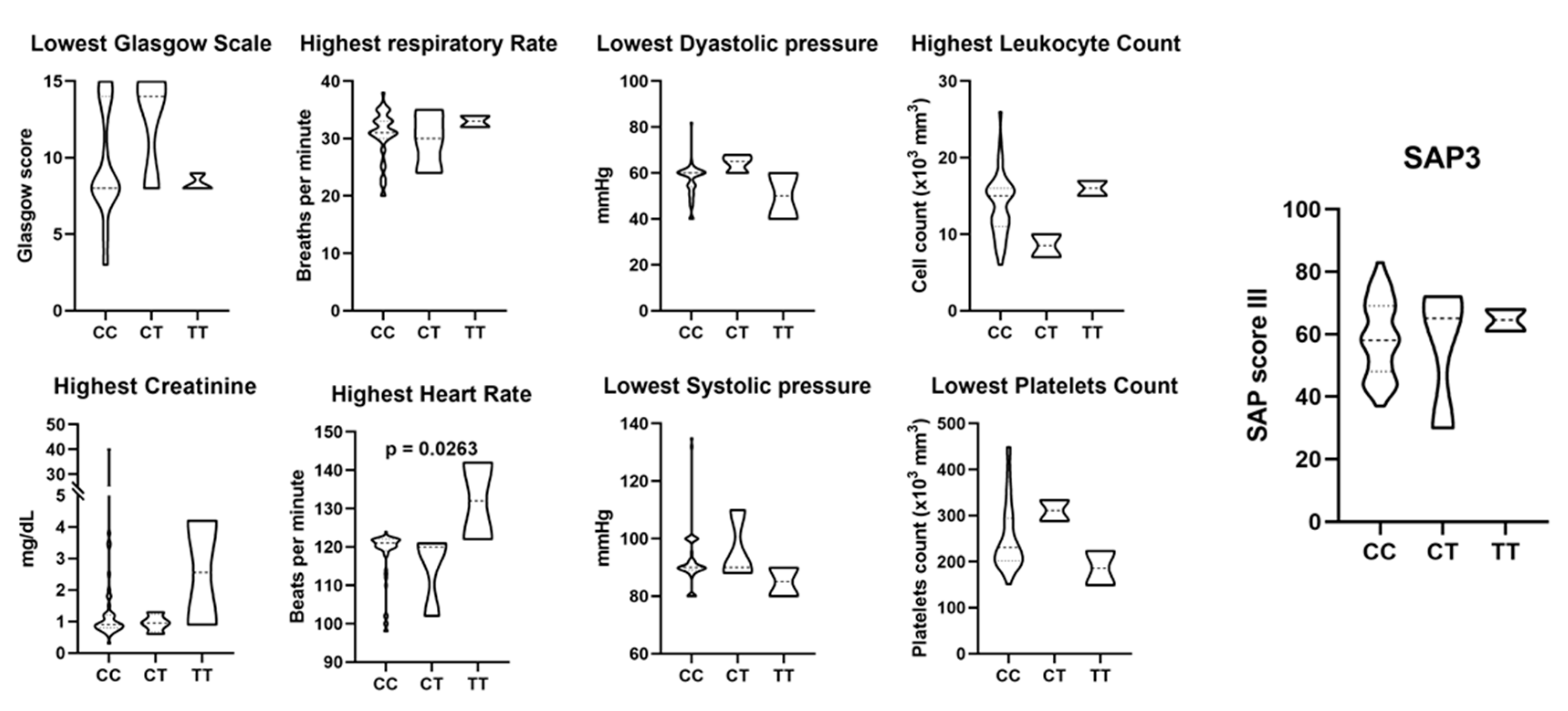

ACE2 and TMPRSS2 SNPs were not associated with COVID-19 severity and mortality

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395(10223), 497–506 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Souza PFN, Mesquita FP, Amaral JL et al. The human pandemic coronaviruses on the show: The spike glycoprotein as the main actor in the coronaviruses play, Elsevier B.V., (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 181(2), 271-280.e8 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science (80-. ). 367(6485), 1444–1448 (2020).

- Strafella C, Caputo V, Termine A et al. Analysis of ACE2 Genetic Variability among Populations Highlights a Possible Link with COVID-19-Related Neurological Complications. Genes 2020, Vol. 11, Page 741 11(7), 741 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kehdy FSG, Pita-Oliveira M, Scudeler MM et al. Human-SARS-CoV-2 interactome and human genetic diversity: TMPRSS2-rs2070788, associated with severe influenza, and its population genetics caveats in Native Americans. Genet. Mol. Biol. 44(1 Suppl 1) (2021). [CrossRef]

- Khayat AS, De Assumpção PP, Khayat BCM et al. ACE2 polymorphisms as potential players in COVID-19 outcome. PLoS One 15(12) (2020). [CrossRef]

- Irham LM, Chou WH, Calkins MJ, Adikusuma W, Hsieh SL, Chang WC. Genetic variants that influence SARS-CoV-2 receptor TMPRSS2 expression among population cohorts from multiple continents. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 529(2), 263–269 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet (London, England) 395(10223), 470–473 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Phan T. Novel coronavirus: From discovery to clinical diagnostics. Infect. Genet. Evol. 79 (2020). [CrossRef]

- de Melo CML, Silva GAS, Melo ARS, de Freitas AC. COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: the Brazilian reality from the first case to the collapse of health services. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 92(4), 1–14 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell Discov. 6(1) (2020). [CrossRef]

- Islam KU, Iqbal J. An Update on Molecular Diagnostics for COVID-19. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Calvo-González E. On slaves and genes: ‘origins’ and ‘processes’ in genetic studies of the Brazilian population. Hist. Cienc. Saude. Manguinhos. 21(4), 1–16 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Suryamohan K, Diwanji D, Stawiski EW et al. Human ACE2 receptor polymorphisms and altered susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. Commun. Biol. 2021 41 4(1), 1–11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ng JW, Chong ETJ, Lee P-C. An Updated Review on the Role of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in COVID-19 Disease Severity: A Global Aspect. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 23(13), 1596–1611 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Suh S, Lee S, Gym H et al. A systematic review on papers that study on Single Nucleotide Polymorphism that affects coronavirus 2019 severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 22(1) (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pena SDJ, Santos FR, Tarazona-Santos E. Genetic admixture in Brazil. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 184(4), 928–938 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Graffelman J, Jain D, Weir B. A genome-wide study of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with next generation sequence data. Hum. Genet. 136(6), 727–741 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Abramovs N, Brass A, Tassabehji M. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium in the Large Scale Genomic Sequencing Era. Front. Genet. 11 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mychaleckyj JC, Havt A, Nayak U et al. Genome-Wide Analysis in Brazilians Reveals Highly Differentiated Native American Genome Regions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34(3), 559–574 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Manta FSN, Pereira R, Caiafa A, Silva DA, Gusmão L, Carvalho EF. Analysis of genetic ancestry in the admixed Brazilian population from Rio de Janeiro using 46 autosomal ancestry-informative indel markers. Ann. Hum. Biol. 40(1), 94–98 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Grover VK, Cole DEC, Hamilton DC. Attributing Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium to population stratification and genetic association in case-control studies. Ann. Hum. Genet. 74(1), 77–87 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Aguet F, Barbeira AN, Bonazzola R et al. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369(6509), 1318–1330 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z, Zhou J, To KKW et al. Identification of TMPRSS2 as a Susceptibility Gene for Severe 2009 Pandemic A(H1N1) Influenza and A(H7N9) Influenza. J. Infect. Dis. 212(8), 1214–1221 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shovlin CL, Vizcaychipi MP. Vascular inflammation and endothelial injury in SARS-CoV-2 infection: The overlooked regulatory cascades implicated by the ACE2 gene cluster. QJM (2020). [CrossRef]

- Giridharan S, Srinivasan M. Mechanisms of NF-κB p65 and strategies for therapeutic manipulation. J. Inflamm. Res. 11, 407–419 (2018).

- Hariharan A, Hakeem AR, Radhakrishnan S, Reddy MS, Rela M. The Role and Therapeutic Potential of NF-kappa-B Pathway in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Inflammopharmacology 29(1), 91–100 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Shoily SS, Ahsan T, Fatema K, Sajib AA. Disparities in COVID-19 severities and casualties across ethnic groups around the globe and patterns of ACE2 and PIR variants. Infect. Genet. Evol. 92 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pandey RK, Srivastava A, Singh PP, Chaubey G. Genetic association of TMPRSS2 rs2070788 polymorphism with COVID-19 case fatality rate among Indian populations. Infect. Genet. Evol. 98, 105206 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Shikov AE, Barbitoff YA, Glotov AS et al. Analysis of the Spectrum of ACE2 Variation Suggests a Possible Influence of Rare and Common Variants on Susceptibility to COVID-19 and Severity of Outcome. Front. Genet. 11, 1129 (2020). [CrossRef]

| Variable | Outcome | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged | Death | All patients | ||

| aAge (Mean ± Std. Dev.) | 48.7 ± 21.5 | 60.5 ± 17.1 | 51 ± 21.10 | 0.094 |

| bGender (%) | ||||

| Male | 25 (78.1%) | 7 (21.9%) | 32 (57.1) | 0.741 |

| Female | 20 (83.3%) | 4 (16.7%) | 24 (42.9) | |

| cClinical-laboratorial measurements [Median (IQR)] | ||||

| Lowest Systolic Blood Pressure | 90 (10) | 89 (2) | 90 (3.75) | 0.001 |

| Lowest Diastolic Blood Pressure | 60 (6) | 55 (11) | 60 (6) | 0.185 |

| Highest Heart Rate | 120 (6) | 121 (2) | 121 (3) | 0.116 |

| Highest Respiratory Rate | 31 (6) | 33 (3) | 31 (3) | 0.001 |

| Lowest Glasgow Scale | 8 (6) | 8 (3) | 8 (6) | 0.021 |

| Highest Leukocyte Count | 14 (6) | 15 (4.5) | 15 (5.75) | 0.295 |

| Lowest Platelets Count | 229.5 (81.8) | 231.0 (138.3) | 231 (94) | 0.602 |

| Highest Creatinine | 0.90 (0.40) | 1.25 (0.97) | 0.90 (0.47) | 0.150 |

| SAPS3 | 57 (21.5) | 71 (15) | 59.5 (20.5) | 0.0003 |

| bSepsis N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (63.2%) | 7 (36.8%) | 19 (33.9) | 0.0325 |

| No | 33 (89.2%) | 4 (10.8%) | 37 (66.1) | |

| bMechanical Ventilation N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 22 (68.75%) | 10 (31.25%) | 32 (57.1) | 0.0161 |

| No | 23 (95.8%) | 1 (4.2%) | 24 (42.9) | |

| TMPRSS2 (rs2070788) | Genotype frequency (N) | HWE | Allele frequency (N) | 'Fisher's exact test# | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | AA | AG | χ² | p-value | G | A | p-value | |

| All | 0.166 (416) | 0.373 (933) | 0.461 (1155) | 3.317 | >0.05 | 0.397 (1987) | 0.603 (3021) | 0.0072 |

| AFR | 0.070 (46) | 0.522 (345) | 0.408 (270) | 0.486 | >0.05 | 0.274 (362) | 0.726 (960) | <0.0001 |

| AMR | 0.245 (85) | 0.256 (89) | 0.499 (173) | 0.003 | >0.05 | 0.494 (343) | 0.506 (351) | 0.6272 |

| EAS | 0.123 (62) | 0.411 (207) | 0.466 (235) | 0.140 | >0.05 | 0.356 (359) | 0.644 (649) | 0.0002 |

| SAS | 0.227 (111) | 0.294 (144) | 0.479 (234) | 0.728 | >0.05 | 0.466 (456) | 0.534 (522) | 0.7904 |

| EUR | 0.223 (112) | 0.294 (148) | 0.483 (243) | 0.418 | >0.05 | 0.464 (467) | 0.536 (539) | 0.7405 |

| BRAZIL | 0.223 (33) | 0.270 (40) | 0.507 (75) | 0.037 | >0.05 | 0.476 (141) | 0.524 (155) | - |

| ACE2 (rs35803318) | Genotype frequencies (N) | HWE | Allele frequencies (N) | Fisher's exact test# | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | TT | CT | χ² | P-value | C | T | p-value | |

| All | 0.486 (1218) | 0.00039 (1) | 0.021 (52) | 0.347 | >0.05 | 0.979 (3696) | 0.021 (79) | 0.0004 |

| AFR | 0.516 (341) | 0 | 0.002 (1) | 0.151 | >0.05 | 0.999 (1002) | 0.001 (1) | <0.0001 |

| AMR | 0.447 (155) | 0 | 0.063 (22) | 1.001 | >0.05 | 0.929 (487) | 0.071 (37) | 0.5581 |

| EAS | 0.516 (260) | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | >0.05 | 1.000 (764) | 0 | <0.0001 |

| SAS | 0.468 (229) | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | >0.05 | 1.000 (718) | 0 | <0.0001 |

| EUR | 0.463 (233) | 0.002 (1) | 0.058 (29) | 0.261 | >0.05 | 0.946 (725) | 0.054 (41) | 0.7656 |

| BRAZIL | 0.926 (137) | 0.040 (6) | 0.034 (5) | 71.182 | <0.05 | 0.943 (279) | 0.057 (17) | - |

| Variable | Genotype % | Allele % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | AA | AG | GG | p-value | G | A | p-value | |

| Outcome | ||||||||

| Hospital discharge | 45 | 24.4 | 48.9 | 26.7 | 0.2776 | 51.1 | 48.9 | 0.2731 |

| Death | 11 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 9.1 | 31.8 | 68.2 | ||

| Sepsis | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 | 26.3 | 42.1 | 31.6 | 0.5654 | 52.6 | 47.4 | 0.5736 |

| No | 37 | 29.7 | 51.4 | 18.9 | 44.6 | 55.4 | ||

| Mechanical Ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 32 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 0.7846 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 0.6526 |

| No | 24 | 33.3 | 45.8 | 20.8 | 43.8 | 56.3 | ||

| Variable | Genotype % | Allele % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | CC | CT | TT | p-value | C | T | p-value | |

| Outcome | ||||||||

| Hospital discharge | 45 | 93.3 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 0.4377 | 95.6 | 4.4 | 0.1408 |

| Death | 11 | 81.8 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 86.4 | 13.6 | ||

| Sepsis | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 | 94.7 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.5857 | 97.4 | 2.6 | 0.6611 |

| No | 37 | 58.9 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 91.9 | 8.1 | ||

| Mechanical Ventilation | ||||||||

| Yes | 32 | 90.6 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 0.3335 | 92.2 | 7.8 | 0.4724 |

| No | 24 | 91.7 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 95.8 | 4.2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).