Submitted:

23 October 2023

Posted:

24 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. GABAergic Hypothesis in Depression

3. GABA and Cognitive Function in Depression

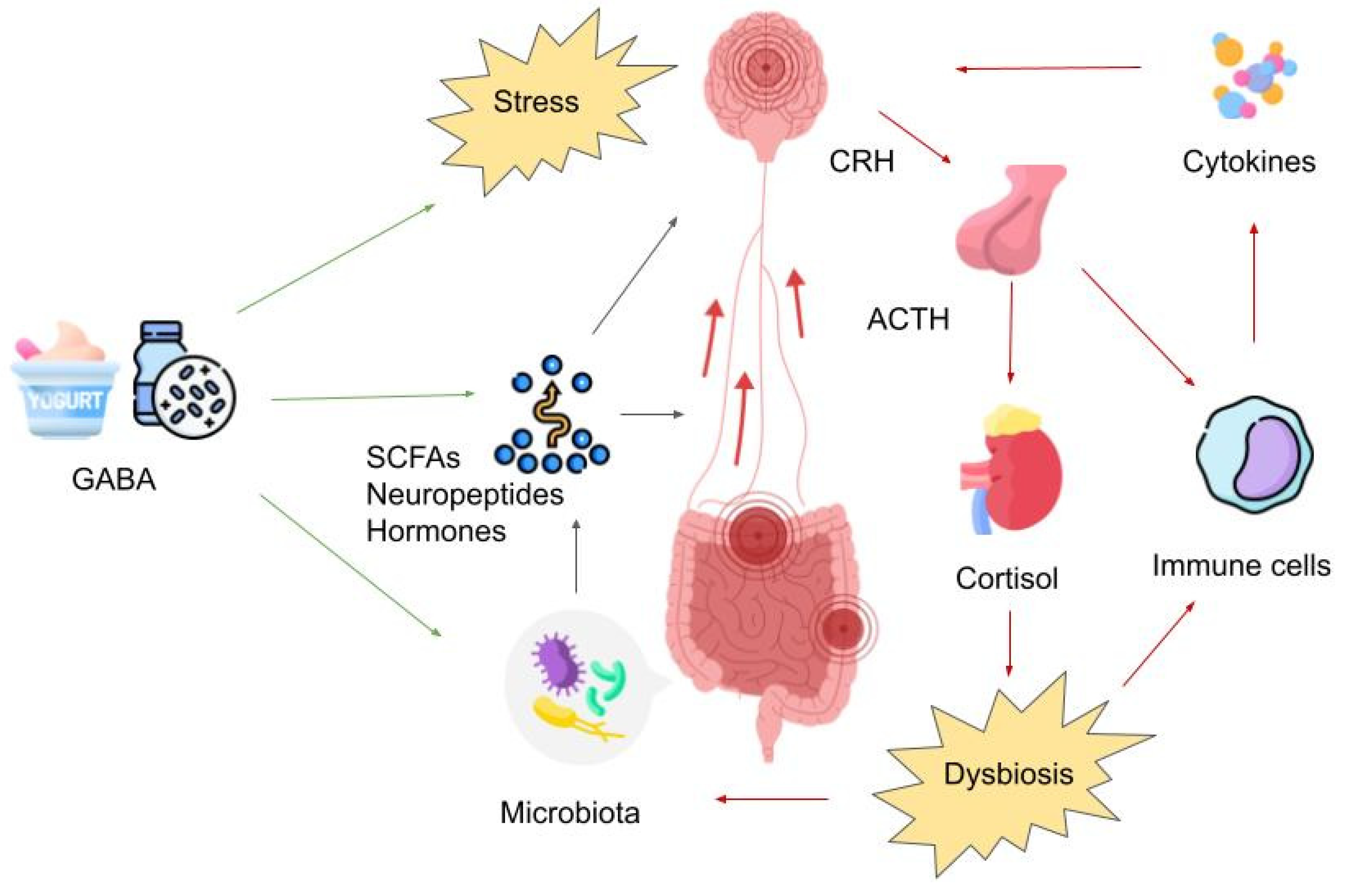

4. GABA and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

5. GABA’s Impact on the Enteric Nervous System

6. Traditional Diets and Their Impact on Mood

7. Fermented Foods Enriched with GABA

8. GABA-Enriched Fermented Foods as Neuro-Therapeutics

9. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx).

- World Health Organization Depression.

- Bierman, E.J.M.; Comijs, H.C.; Jonker, C.; Beekman, A.T.F. Effects of Anxiety Versus Depression on Cognition in Later Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2005, 13, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, E.; Pause, B.M.; Pietrowsky, R. Emotion and Episodic Memory in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Behavioural Brain Research 2010, 215, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, M.; Ising, M.; Künzel, H.; Binder, E.B.; Holsboer, F.; Modell, S.; Zihl, J. Impaired Divided Attention Predicts Delayed Response and Risk to Relapse in Subjects with Depressive Disorders. Psychol Med 2004, 34, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Cha, D.S.; Soczynska, J.K.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Gallaugher, L.A.; Kudlow, P.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Baskaran, A. Cognitive Deficits and Functional Outcomes in Major Depressive Disorder: Determinants, Substrates, and Treatment Interventions. Depress Anxiety 2013, 30, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semkovska, M.; Quinlivan, L.; O’Grady, T.; Johnson, R.; Collins, A.; O’Connor, J.; Knittle, H.; Ahern, E.; Gload, T. Cognitive Function Following a Major Depressive Episode: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.E.; Fournier, A.-A.; Sisitsky, T.; Simes, M.; Berman, R.; Koenigsberg, S.H.; Kessler, R.C. The Economic Burden of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). Pharmacoeconomics 2021, 39, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolote, J.M.; Fleischmann, A.; De Leo, D.; Wasserman, D. Psychiatric Diagnoses and Suicide: Revisiting the Evidence. Crisis 2004, 25, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Gureje, O.; et al. Socio-Economic Variations in the Mental Health Treatment Gap for People with Anxiety, Mood, and Substance Use Disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Psychol Med 2018, 48, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bassett, D.; Boyce, P.; Bryant, R.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Fritz, K.; Hopwood, M.; Lyndon, B.; Mulder, R.; Murray, G.; et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines for Mood Disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2015, 49, 1087–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, H.; Shaw, I.; Hull, S.; Feder, G. NICE Guidelines for the Management of Depression. BMJ 2005, 330, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härter, M.; Prien, P. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Unipolar Depression—National Disease Management Guideline. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Eckshtain, D.; Ng, M.Y.; Corteselli, K.A.; Noma, H.; Quero, S.; Weisz, J.R. Psychotherapy for Depression Across Different Age Groups: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Bell, E. Make News: Treatment-Resistant Depression – an Irreversible Problem in Need of a Reversible Solution? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 54, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Das, P.; Mannie, Z.; Irwin, L. Treatment-Resistant Depression: Problematic Illness or a Problem in Our Approach? British Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 214, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thase, M.E.; Friedman, E.S.; Biggs, M.M.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Trivedi, M.H.; Luther, J.F.; Fava, M.; Nierenberg, A.A.; McGrath, P.J.; Warden, D.; et al. Cognitive Therapy versus Medication in Augmentation and Switch Strategies as Second-Step Treatments: A STAR*D Report. Am J Psychiatry 2007, 164, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Stewart, J.W.; Warden, D.; Niederehe, G.; Thase, M.E.; Lavori, P.W.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report. Am J Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, J.E. Methodologic Issues in the Epidemiology of Treatment Resistant Depression. Contribution to Epidemiology. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol 1974, 7, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, D.J.; Charney, D.S. “Difficult-to-Treat Depression”. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 53, 633–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes, A.J.; Parker, G.B. Comparison of Guidelines for the Treatment of Unipolar Depression: A Focus on Pharmacotherapy and Neurostimulation. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018, 137, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bwalya, G.M.; Srinivasan, V.; Wang, M. Electroconvulsive Therapy Anesthesia Practice Patterns: Results of a UK Postal Survey. J ECT 2011, 27, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pando, D.; González-Menéndez, A.; Aparicio-Basauri, V.; Sanz de la Garza, C.L.; Torracchi-Carrasco, J.E.; Pérez-Álvarez, M. Ethical Implications of Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Review. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry 2021, 23, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergel, T.; Howard, R.; Lawrence, R.; Seneviratne, T. Time to Acknowledge Good Electroconvulsive Therapy Research. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 1032–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscher, B.; Shen, Q.; Sahir, N. The GABAergic Deficit Hypothesis of Major Depressive Disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiering, M.J. The Discovery of GABA in the Brain. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 19159–19160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.M.; Higashiguchi, S.; Horie, K.; Kim, M.; Hatta, H.; Yokogoshi, H. Relaxation and Immunity Enhancement Effects of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Administration in Humans. BioFactors 2006, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Kang, Y.M.; Lim, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, M.-S.; Jeong, M.-H.; Ahn, C.-B.; Je, J.-Y. Antioxidant Activity and γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Content in Sea Tangle Fermented by Lactobacillus Brevis BJ20 Isolated from Traditional Fermented Foods. Food Chem 2010, 122, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wei, M.; Wu, J.; Rui, X.; Dong, M. Novel Fermented Chickpea Milk with Enhanced Level of γ -Aminobutyric Acid and Neuroprotective Effect on PC12 Cells. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Xu, L.; Zeng, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, B.; He, N. New Perspective of GABA as an Inhibitor of Formation of Advanced Lipoxidation End-Products: It’s Interaction with Malondiadehyde. J Biomed Nanotechnol 2010, 6, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, H.; Furuya, Y.; Endo, Y.; Fujimoto, K. Effect of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid-Enriched Tempeh-like Fermented Soybean (GABA-Tempeh) on the Blood Pressure of Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2003, 67, 1806–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, E.K.; Kim, N.Y.; Ahn, H.J.; Ji, G.E. γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Production and Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Activity of Fermented Soybean Containing Sea Tangle by the Co-Culture of Lactobacillus Brevis with Aspergillus Oryzae. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 25, 1315–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, L.; Xu, P. Neurotransmitter γ-Aminobutyric Acid-Mediated Inhibition of the Invasive Ability of Cholangiocarcinoma Cells. Oncol Lett 2011, 2, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.C.; Kemp, J.A. Glutamate- and GABA-Based CNS Therapeutics. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2006, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Rothman, D.L.; Cline, G.W.; Behar, K.L. Glutamine Is the Major Precursor for GABA Synthesis in Rat Neocortex in Vivo Following Acute GABA-Transaminase Inhibition. Brain Res 2001, 919, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möhler, H. Molecular Regulation of Cognitive Functions and Developmental Plasticity: Impact of GABA A Receptors. J Neurochem 2007, 102, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, I.; Pearce, R.A. Diversity of Inhibitory Neurotransmission through GABA(A) Receptors. Trends Neurosci 2004, 27, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mombereau, C.; Kaupmann, K.; Froestl, W.; Sansig, G.; van der Putten, H.; Cryan, J.F. Genetic and Pharmacological Evidence of a Role for GABA(B) Receptors in the Modulation of Anxiety- and Antidepressant-like Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombereau, C.; Kaupmann, K.; Gassmann, M.; Bettler, B.; van der Putten, H.; Cryan, J.F. Altered Anxiety and Depression-Related Behaviour in Mice Lacking GABAB(2) Receptor Subunits. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscher, B.; Shen, Q.; Sahir, N. The GABAergic Deficit Hypothesis of Major Depressive Disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Burgos, G.; Fish, K.N.; Lewis, D.A. GABA Neuron Alterations, Cortical Circuit Dysfunction and Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia. Neural Plast 2011, 2011, 723184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, P.; Perez, J.; Barale, F.; Schettini, G.; Soares, J.C. GABAergic Dysfunction in Mood Disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2003, 8, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horder, J.; Petrinovic, M.M.; Mendez, M.A.; Bruns, A.; Takumi, T.; Spooren, W.; Barker, G.J.; Künnecke, B.; Murphy, D.G. Glutamate and GABA in Autism Spectrum Disorder-a Translational Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study in Man and Rodent Models. Transl Psychiatry 2018, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lener, M.S.; Niciu, M.J.; Ballard, E.D.; Park, M.; Park, L.T.; Nugent, A.C.; Zarate, C.A. Glutamate and Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Systems in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression and Antidepressant Response to Ketamine. Biol Psychiatry 2017, 81, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, M.K.; Near, J.; Blicher, A.B.; Videbech, P.; Blicher, J.U. Magnetic Resonance (MR) Spectroscopic Measurement of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in Major Depression before and after Electroconvulsive Therapy. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2019, 31, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanacora, G.; Treccani, G.; Popoli, M. Towards a Glutamate Hypothesis of Depression: An Emerging Frontier of Neuropsychopharmacology for Mood Disorders. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lener, M.S.; Iosifescu, D. V In Pursuit of Neuroimaging Biomarkers to Guide Treatment Selection in Major Depressive Disorder: A Review of the Literature. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015, 1344, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, C.; Öngür, D. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Studies of Glutamate-Related Abnormalities in Mood Disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2010, 68, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, D.; Mumuni, A.N.; Jauhar, S.; Condon, B.; Cavanagh, J. Indirect Evidence of Selective Glial Involvement in Glutamate-Based Mechanisms of Mood Regulation in Depression: Meta-Analysis of Absolute Prefrontal Neuro-Metabolic Concentrations. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015, 25, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz-Yesiloglu, A.; Ankerst, D.P. Review of 1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Findings in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res 2006, 147, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkowska, G.; O’Dwyer, G.; Teleki, Z.; Stockmeier, C.A.; Miguel-Hidalgo, J.J. GABAergic Neurons Immunoreactive for Calcium Binding Proteins Are Reduced in the Prefrontal Cortex in Major Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, F.; Schlesser, M.A. Plasma GABA in Affective Illness. J Affect Disord 1981, 3, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, F.; Sherman, A.D. Plasma GABA Levels in Psychiatric Illness. J Affect Disord 1984, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerner, R.H.; Hare, T.A. CSF GABA in Normal Subjects and Patients with Depression, Schizophrenia, Mania, and Anorexia Nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1981, 138, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, A.; Bartlett, J.R.; Bouras, N.; Bridges, P.K. Amino Acid Levels in Depression: A Preliminary Investigation. J Psychiatr Res 1988, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, R.B.; Shungu, D.C.; Mao, X.; Nestadt, P.; Kelly, C.; Collins, K.A.; Murrough, J.W.; Charney, D.S.; Mathew, S.J. Amino Acid Neurotransmitters Assessed by Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: Relationship to Treatment Resistance in Major Depressive Disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2009, 65, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schür, R.R.; Draisma, L.W.R.; Wijnen, J.P.; Boks, M.P.; Koevoets, M.G.J.C.; Joëls, M.; Klomp, D.W.; Kahn, R.S.; Vinkers, C.H. Brain GABA Levels across Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of (1) H-MRS Studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2016, 37, 3337–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohrs, R.; Durieux, M.E. Ketamine. Anesth Analg 1998, 87, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fond, G.; Loundou, A.; Rabu, C.; Macgregor, A.; Lançon, C.; Brittner, M.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Richieri, R.; Courtet, P.; Abbar, M.; et al. Ketamine Administration in Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014, 231, 3663–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, D.J.; Carpenter, L.L.; McDonald, W.M.; Potash, J.B.; Tohen, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. Ketamine and Other NMDA Antagonists: Early Clinical Trials and Possible Mechanisms in Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 2015, 172, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esel, E.; Kose, K.; Hacimusalar, Y.; Ozsoy, S.; Kula, M.; Candan, Z.; Turan, T. The Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy on GABAergic Function in Major Depressive Patients. J ECT 2008, 24, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, M.; Tedeschini, E.; Mistretta, M.; Fehling, K.; Aceti, F.; Ceccanti, M.; Fava, M. Adjunctive Pregabalin in Partial Responders with Major Depressive Disorder and Residual Anxiety. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013, 33, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Baldwin, D.S.; Baldinetti, F.; Mandel, F. Efficacy of Pregabalin in Depressive Symptoms Associated with Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Pooled Analysis of 6 Studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2008, 18, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanacora, G.; Fenton, L.R.; Fasula, M.K.; Rothman, D.L.; Levin, Y.; Krystal, J.H.; Mason, G.F. Cortical Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Concentrations in Depressed Patients Receiving Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Biol Psychiatry 2006, 59, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanacora, G.; Mason, G.F.; Rothman, D.L.; Hyder, F.; Ciarcia, J.J.; Ostroff, R.B.; Berman, R.M.; Krystal, J.H. Increased Cortical GABA Concentrations in Depressed Patients Receiving ECT. Am J Psychiatry 2003, 160, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Peng, T.; Gaur, U.; Silva, M.; Little, P.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W. Role of Corticotropin Releasing Factor in the Neuroimmune Mechanisms of Depression: Examination of Current Pharmaceutical and Herbal Therapies. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S.R.; Buhl, E.H.; Halasy, K.; Paulsen, O.; Somogyi, P. Synchronization of Neuronal Activity in Hippocampus by Individual GABAergic Interneurons. Nature 1995, 378, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Q.; Barberis, A.; Higley, M.J. Preserving the Balance: Diverse Forms of Long-Term GABAergic Synaptic Plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Fuchs, E.; Funke, K.; Vlachos, A.; Müller-Dahlhaus, F.; Puts, N.A.J.; Harris, R.E.; Edden, R.A.E. GABA—from Inhibition to Cognition: Emerging Concepts. The Neuroscientist 2018, 24, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, H.; Rudolph, U. Disinhibition, an Emerging Pharmacology of Learning and Memory. F1000Res 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, N.; Kuenzi, F.M.; Jarolimek, W.; Maubach, K.A.; Cothliff, R.; Sur, C.; Smith, A.; Otu, F.M.; Howell, O.; Atack, J.R.; et al. Enhanced Learning and Memory and Altered GABAergic Synaptic Transmission in Mice Lacking the Alpha 5 Subunit of the GABAA Receptor. J Neurosci 2002, 22, 5572–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, G.; Dutar, P.; Epelbaum, J.; Viollet, C. Somatostatinergic Systems: An Update on Brain Functions in Normal and Pathological Aging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U. Expression of Somatostatin Receptor Subtypes (SSTR1-5) in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: An Immunohistochemical Analysis. Neuroscience 2005, 134, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fee, C.; Banasr, M.; Sibille, E. Somatostatin-Positive Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Interneuron Deficits in Depression: Cortical Microcircuit and Therapeutic Perspectives. Biol Psychiatry 2017, 82, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentet, L.J.; Kremer, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Huang, Z.J.; Staiger, J.F.; Petersen, C.C.H. Unique Functional Properties of Somatostatin-Expressing GABAergic Neurons in Mouse Barrel Cortex. Nat Neurosci 2012, 15, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piantadosi, S.C.; French, B.J.; Poe, M.M.; Timić, T.; Marković, B.D.; Pabba, M.; Seney, M.L.; Oh, H.; Orser, B.A.; Savić, M.M.; et al. Sex-Dependent Anti-Stress Effect of an A5 Subunit Containing GABAA Receptor Positive Allosteric Modulator. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, M.T.; Rosenzweig-Lipson, S.; Gallagher, M. Selective GABA(A) A5 Positive Allosteric Modulators Improve Cognitive Function in Aged Rats with Memory Impairment. Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévot, T.; Sibille, E. Altered GABA-Mediated Information Processing and Cognitive Dysfunctions in Depression and Other Brain Disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, G.; Northoff, G. Discovering Imaging Endophenotypes for Major Depression. Mol Psychiatry 2011, 16, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Nutrition and Health. BMJ 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A. V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Pereira, J.S.; Rea, K.; Nolan, Y.M.; O’Leary, O.F.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Depression’s Unholy Trinity: Dysregulated Stress, Immunity, and the Microbiome. Annu Rev Psychol 2020, 71, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, G.; Hart, R.A.; Charlesworth, R.P.G.; Sharpley, C.F. Gut Microbiome and Depression: What We Know and What We Need to Know. Rev Neurosci 2018, 29, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.R.; Borre, Y.; O’ Brien, C.; Patterson, E.; El Aidy, S.; Deane, J.; Kennedy, P.J.; Beers, S.; Scott, K.; Moloney, G.; et al. Transferring the Blues: Depression-Associated Gut Microbiota Induces Neurobehavioural Changes in the Rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016, 82, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zeng, B.; Zhou, C.; Liu, M.; Fang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J.; Fan, S.; Du, X.; et al. Gut Microbiome Remodeling Induces Depressive-like Behaviors through a Pathway Mediated by the Host’s Metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ning, L.; Yin, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Yang, X.; Yin, L.; et al. Age-Related Shifts in Gut Microbiota Contribute to Cognitive Decline in Aged Rats. Aging 2020, 12, 7801–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehme, M.; Guzzetta, K.E.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; van de Wouw, M.; Moloney, G.M.; Gual-Grau, A.; Spichak, S.; Olavarría-Ramírez, L.; Fitzgerald, P.; Morillas, E.; et al. Microbiota from Young Mice Counteracts Selective Age-Associated Behavioral Deficits. Nat Aging 2021, 1, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Pu, J.; Ji, P.; et al. Toward a Deeper Understanding of Gut Microbiome in Depression: The Promise of Clinical Applicability. Advanced Science 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Gangwisch, J.E.; Borsini, A.; Wootton, R.E.; Mayer, E.A. Food and Mood: How Do Diet and Nutrition Affect Mental Wellbeing? BMJ 2020, m2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Harnessing the Microbiota for Therapeutic Purposes. American Journal of Transplantation 2020, 20, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaub, A.-C.; Schneider, E.; Vazquez-Castellanos, J.F.; Schweinfurth, N.; Kettelhack, C.; Doll, J.P.K.; Yamanbaeva, G.; Mählmann, L.; Brand, S.; Beglinger, C.; et al. Clinical, Gut Microbial and Neural Effects of a Probiotic Add-on Therapy in Depressed Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Peters, C.; Ho, C.Y.X.; Lim, D.Y.; Yeo, W.-S. A Meta-Analysis of the Use of Probiotics to Alleviate Depressive Symptoms. J Affect Disord 2018, 228, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, V.L.; Cleare, A.J.; Young, A.H.; Stone, J.M. Acceptability, Tolerability, and Estimates of Putative Treatment Effects of Probiotics as Adjunctive Treatment in Patients With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, A.-C.; Schneider, E.; Vazquez-Castellanos, J.F.; Schweinfurth, N.; Kettelhack, C.; Doll, J.P.K.; Yamanbaeva, G.; Mählmann, L.; Brand, S.; Beglinger, C.; et al. Clinical, Gut Microbial and Neural Effects of a Probiotic Add-on Therapy in Depressed Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Transl Psychiatry 2022, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Gutiérrez, L.; San Vicente, L.; Barrón, L.J.R.; del Carmen Villarán, M.; Chávarri, M. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid and Probiotics: Multiple Health Benefits and Their Future in the Global Functional Food and Nutraceuticals Market. J Funct Foods 2020, 64, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodnar, D.; Paucean, A.; Dulf, F.; Socaciu, C. HPLC Characterization of Lactic Acid Formation and FTIR Fingerprint of Probiotic Bacteria during Fermentation Processes. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj Napoca 2010, 38, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, H.; Green, J.; Jacka, F.N.; Collier, F.; Berk, M.; Pasco, J.; Dawson, S.L. Fermented Foods, the Gut and Mental Health: A Mechanistic Overview with Implications for Depression and Anxiety. Nutr Neurosci 2020, 23, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Lehto, S.M.; Harty, S.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Burnet, P.W.J. Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria–Gut–Brain Signals. Trends Neurosci 2016, 39, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaibe, E.; Metzer, E.; Halpern, Y.S. Metabolic Pathway for the Utilization of L-Arginine, L-Ornithine, Agmatine, and Putrescine as Nitrogen Sources in Escherichia Coli K-12. J Bacteriol 1985, 163, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.K.; Kassam, T.; Singh, B.; Elliott, J.F. Escherichia Coli Has Two Homologous Glutamate Decarboxylase Genes That Map to Distinct Loci. J Bacteriol 1992, 174, 5820–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokusaeva, K.; Johnson, C.; Luk, B.; Uribe, G.; Fu, Y.; Oezguen, N.; Matsunami, R.K.; Lugo, M.; Major, A.; Mori-Akiyama, Y.; et al. <scp>GABA</Scp> -producing Bifidobacterium Dentium Modulates Visceral Sensitivity in the Intestine. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandwitz, P.; Kim, K.H.; Terekhova, D.; Liu, J.K.; Sharma, A.; Levering, J.; McDonald, D.; Dietrich, D.; Ramadhar, T.R.; Lekbua, A.; et al. GABA-Modulating Bacteria of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Forsythe, P.; Chew, M.V.; Escaravage, E.; Savignac, H.M.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Ingestion of Lactobacillus Strain Regulates Emotional Behavior and Central GABA Receptor Expression in a Mouse via the Vagus Nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 16050–16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-Altering Microorganisms: The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Brain and Behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Ann Gastroenterol 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrett, E.; Ross, R.P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C. γ-Aminobutyric Acid Production by Culturable Bacteria from the Human Intestine. J Appl Microbiol 2012, 113, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auteri, M.; Zizzo, M.G.; Serio, R. GABA and GABA Receptors in the Gastrointestinal Tract: From Motility to Inflammation. Pharmacol Res 2015, 93, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front Neurosci 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.A.; Julio-Pieper, M.; Forsythe, P.; Kunze, W.; Dinan, T.G.; Bienenstock, J.; Cryan, J.F. Communication between Gastrointestinal Bacteria and the Nervous System. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2012, 12, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, R.; Roncon, P.; Lagarde, S.; Dibué, M.; Zanello, M.; Bartolomei, F. Latest Views on the Mechanisms of Action of Surgically Implanted Cervical Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Epilepsy. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2023, 26, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; O’Leary, G.H.; Thompson, S.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Comprehensive Review of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Depression. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2022, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrosu, F.; Serra, A.; Maleci, A.; Puligheddu, M.; Biggio, G.; Piga, M. Correlation between GABAA Receptor Density and Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Individuals with Drug-Resistant Partial Epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2003, 55, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Menachem, E.; Hamberger, A.; Hedner, T.; Hammond, E.J.; Uthman, B.M.; Slater, J.; Treig, T.; Stefan, H.; Ramsay, R.E.; Wernicke, J.F.; et al. Effects of Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Amino Acids and Other Metabolites in the CSF of Patients with Partial Seizures. Epilepsy Res 1995, 20, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, B. Fermentation. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology; Wiley, 2004.

- Steinkraus, K.H. Fermentations in World Food Processing. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2002, 1, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.S.; Joyce, R.A.; Hall, G.R.; Hurst, W.J.; McGovern, P.E. Chemical and Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 18937–18940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern Anticancer Activity of Botanical Compounds in Ancient Fermented Beverages (Review). Int J Oncol 2010, 37. [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.E.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hall, G.R.; Moreau, R.A.; Nuñez, A.; Butrym, E.D.; Richards, M.P.; Wang, C.; et al. Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 17593–17598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplice, E. Food Fermentations: Role of Microorganisms in Food Production and Preservation. Int J Food Microbiol 1999, 50, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Borresen, E.; J. Henderson, A.; Kumar, A.; L. Weir, T.; P. Ryan, E. Fermented Foods: Patented Approaches and Formulations for Nutritional Supplementation and Health Promotion. Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition & Agriculturee 2012, 4, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selhub, E.M.; Logan, A.C.; Bested, A.C. Fermented Foods, Microbiota, and Mental Health: Ancient Practice Meets Nutritional Psychiatry. J Physiol Anthropol 2014, 33, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, B.H. Depression as a Disease of Modernity: Explanations for Increasing Prevalence. J Affect Disord 2012, 140, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, A.C.; Selhub, E.M. Vis Medicatrix Naturae: Does Nature “Minister to the Mind”? Biopsychosoc Med 2012, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Martínez-González, M.A. Diet, a New Target to Prevent Depression? BMC Med 2013, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.P.; van Vugt, M.; Colarelli, S.M. The Evolutionary Mismatch Hypothesis: Implications for Psychological Science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2018, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Durante, K.M. Why Consumers Have Everything but Happiness: An Evolutionary Mismatch Perspective. Curr Opin Psychol 2022, 46, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesseltine, C.W.; Wang, H.L. Traditional Fermented Foods. Biotechnol Bioeng 1967, 9, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, N.; Katayama, A.; Dokai Mochimasu, K.; Hishii, S.; Suzuki, H.; Miyatake, N. A Pilot Study of the Relationship between Diet and Mental Health in Community Dwelling Japanese Women. Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 55, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Sancassiani, F.; Contu, M.P.; Latorre, M.; Di Slavatore, M.; Fornaro, M.; Bhugra, D. Mediterranean Diet and Its Benefits on Health and Mental Health: A Literature Review. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health 2020, 16, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, M.; Toyomaki, A.; Miyazaki, A.; Nakai, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Kubo, C.; Suzuki, J.; Ohkubo, I.; Shimizu, M.; Musashi, M.; et al. Mediators of the Effects of Rice Intake on Health in Individuals Consuming a Traditional Japanese Diet Centered on Rice. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanri, A.; Kimura, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Ohta, M.; Sato, M.; Mishima, N.; Sasaki, S.; Mizoue, T. Dietary Patterns and Depressive Symptoms among Japanese Men and Women. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010, 64, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanri, A.; Mizoue, T.; Poudel-Tandukar, K.; Noda, M.; Kato, M.; Kurotani, K.; Goto, A.; Oba, S.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S. Dietary Patterns and Suicide in Japanese Adults: The Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. British Journal of Psychiatry 2013, 203, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Miyaki, K.; Tsutsumi, A.; Hashimoto, H.; Kawakami, N.; Takahashi, M.; Shimazu, A.; Inoue, A.; Kurioka, S.; Kakehashi, M.; et al. Japanese Dietary Pattern Consistently Relates to Low Depressive Symptoms and It Is Modified by Job Strain and Worksite Supports. J Affect Disord 2013, 150, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanada, M.; Imai, T.; Sezaki, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Kawase, F.; Shirai, Y.; Abe, C.; Suzuki, N.; Inden, A.; Kato, T.; et al. Changes in the Association between the Traditional Japanese Diet Score and Suicide Rates over 26 Years: A Global Comparative Study. J Affect Disord 2021, 294, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murooka, Y.; Yamshita, M. Traditional Healthful Fermented Products of Japan. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 35, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N.; Mykletun, A.; Berk, M.; Bjelland, I.; Tell, G.S. The Association Between Habitual Diet Quality and the Common Mental Disorders in Community-Dwelling Adults. Psychosom Med 2011, 73, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Pasco, J.A.; Mykletun, A.; Williams, L.J.; Hodge, A.M.; O’Reilly, S.L.; Nicholson, G.C.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Berk, M. Association of Western and Traditional Diets With Depression and Anxiety in Women. American Journal of Psychiatry 2010, 167, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Alonso, A.; Schlatter, J.; Lahortiga, F.; Majem, L.S.; Martínez-González, M.A. Association of the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern With the Incidence of Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009, 66, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaraly, T.N.; Brunner, E.J.; Ferrie, J.E.; Marmot, M.G.; Kivimaki, M.; Singh-Manoux, A. Dietary Pattern and Depressive Symptoms in Middle Age. British Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 195, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarupski, K.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Li, H.; Evans, D.A.; Morris, M.C. Mediterranean Diet and Depressive Symptoms among Older Adults over Time. J Nutr Health Aging 2013, 17, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienks, J.; Dobson, A.J.; Mishra, G.D. Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Prevalence and Incidence of Depressive Symptoms in Mid-Aged Women: Results from a Large Community-Based Prospective Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013, 67, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Henríquez, P.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Doreste, J. Mediterranean Diet and Depression. Public Health Nutr 2006, 9, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, U.E.; Beglinger, C.; Schweinfurth, N.; Walter, M.; Borgwardt, S. Nutritional Aspects of Depression. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2015, 37, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Löf, M.; Chen, R.; Hultman, C.M.; Fang, F.; Sandin, S. Mediterranean Diet and Depression: A Population-Based Cohort Study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2021, 18, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Arós, F.; Romaguera, D.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Depression: The PREDIMED Randomized Trial. BMC Med 2013, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes, J.; Schloss, J.; Sibbritt, D. A Randomised Controlled Trial Assessing the Effect of a Mediterranean Diet on the Symptoms of Depression in Young Men (the ‘AMMEND’ Study): A Study Protocol. British Journal of Nutrition 2021, 126, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Cabrera-Suárez, B.; Molero, P.; González-Pinto, A.; Chiclana-Actis, C.; Cabrera, C.; Lahortiga-Ramos, F.; Florido-Rodríguez, M.; Vega-Pérez, P.; Vega-Pérez, R.; et al. Preventing the Recurrence of Depression with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil. The PREDI-DEP Trial: Study Protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parletta, N.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Cho, J.; Wilson, A.; Bogomolova, S.; Villani, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Niyonsenga, T.; Blunden, S.; Meyer, B.; et al. A Mediterranean-Style Dietary Intervention Supplemented with Fish Oil Improves Diet Quality and Mental Health in People with Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci 2019, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opie, R.S.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Pizzinga, J.; Itsiopoulos, C. A Modified Mediterranean Dietary Intervention for Adults with Major Depression: Dietary Protocol and Feasibility Data from the SMILES Trial. Nutr Neurosci 2018, 21, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A.T.; Davis, C.R.; Dyer, K.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; Woodman, R.J.; Keage, H.A.D.; Murphy, K.J. A Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Dairy Foods Improves Mood and Processing Speed in an Australian Sample: Results from the MedDairy Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutr Neurosci 2020, 23, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.; Bhatnagar, D. The Mediterranean Diet. Curr Opin Lipidol 2016, 27, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naureen, Z.; Bonetti, G.; Medori, M.C.; Aquilanti, B.; Velluti, V.; Matera, G.; Iaconelli, A.; Bertelli, M. Foods of the Mediterranean Diet: Lacto-Fermented Food, the Food Pyramid and Food Combinations. J Prev Med Hyg 2022, 63, E28–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briguglio, M.; Dell’Osso, B.; Panzica, G.; Malgaroli, A.; Banfi, G.; Zanaboni Dina, C.; Galentino, R.; Porta, M. Dietary Neurotransmitters: A Narrative Review on Current Knowledge. Nutrients 2018, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, M.; Quílez, J.; Rafecas, M. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid as a Bioactive Compound in Foods: A Review. J Funct Foods 2014, 10, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Pan, D.; Zeng, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, G. Effect of Adzuki Bean Sprout Fermented Milk Enriched in γ-Aminobutyric Acid on Mild Depression in a Mouse Model. J Dairy Sci 2021, 104, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I.; Sohedein, M.N.A.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Ab Kadir, S.; Suan, O.P.; Weng Loen, A.W.; Sassi, S.; Ilham, Z. Isolation, Identification, and Optimization of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)-Producing Bacillus Cereus Strain KBC from a Commercial Soy Sauce Moromi in Submerged-Liquid Fermentation. Processes 2020, 8, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, D.M.; O’Callaghan, T.F.; O’Connor, P.M.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Streptococcus Thermophilus APC151 Strain Is Suitable for the Manufacture of Naturally GABA-Enriched Bioactive Yogurt. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, R.; Chamignon, C.; Mhedbi-Hajri, N.; Chain, F.; Derrien, M.; Escribano-Vázquez, U.; Garault, P.; Cotillard, A.; Pham, H.P.; Chervaux, C.; et al. The Potential Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus CNCM I-3690 Strain Protects the Intestinal Barrier by Stimulating Both Mucus Production and Cytoprotective Response. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.-W.; Cheng, M.-Y.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Yin, H.-D.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, R.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Yang, W.-T.; Wang, J.-Z.; et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Promotes Mouse Gut Microbiota Diversity and T Cell Differentiation. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 607735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, R.; Thomason, L.A.M.; Stanisz, A.M.; Forsythe, P.; Bienenstock, J.; Stanisz, G.J. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Reveals Oral Lactobacillus Promotion of Increases in Brain GABA, N-Acetyl Aspartate and Glutamate. Neuroimage 2016, 125, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slykerman, R.F.; Hood, F.; Wickens, K.; Thompson, J.M.D.; Barthow, C.; Murphy, R.; Kang, J.; Rowden, J.; Stone, P.; Crane, J.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus HN001 in Pregnancy on Postpartum Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. EBioMedicine 2017, 24, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunes, R.A.; Poluektova, E.U.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Klimina, K.M.; Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Orlova, V.S.; Danilenko, V.N. GABA Production and Structure of GadB/GadC Genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Strains from Human Microbiota. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Jin, G.; Pang, X.; Mo, Q.; Bao, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, J.; Xie, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Colonization in Early Life Regulates Gut-Brain Axis and Relieves Anxiety-like Behavior in Adulthood. Pharmacol Res 2022, 177, 106090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, A.; Coda, R.; Montemurro, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Use of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria and Quinoa Flour for Manufacturing Novel Yogurt-Like Beverages. Foods 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi Gahruie, H.; Eskandari, M.H.; Mesbahi, G.; Hanifpour, M.A. Scientific and Technical Aspects of Yogurt Fortification: A Review. Food Science and Human Wellness 2015, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, M.C. The Nutrition and Health Benefits of Yoghurt. Int J Dairy Technol 2005, 58, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.Y.; Tan, J.S.; Cheng, L.H. Gamma Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Enrichment in Plant-Based Food – A Mini Review. Food Reviews International 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmaram, N.; Dar, B.; Roohinejad, S.; Koubaa, M.; Barba, F.J.; Greiner, R.; Johnson, S.K. Recent Advances in γ -Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Properties in Pulses: An Overview. J Sci Food Agric 2017, 97, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Shirai, T.; Ochiai, H.; Kasao, M.; Hayakawa, K.; Kimura, M.; Sansawa, H. Blood-Pressure-Lowering Effect of a Novel Fermented Milk Containing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in Mild Hypertensives. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003, 57, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, M.; Quílez, J.; Rafecas, M. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid as a Bioactive Compound in Foods: A Review. J Funct Foods 2014, 10, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, E.; de Kleijn, R.; Colzato, L.S.; Alkemade, A.; Forstmann, B.U.; Nieuwenhuis, S. Neurotransmitters as Food Supplements: The Effects of GABA on Brain and Behavior. Front Psychol 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TSUKADA, Y.; NAGATA, Y.; HIRANO, S. Active Transport of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid in Brain Cortex Slices, with Special Reference to Phosphorus-32 Turnover of Phospholipids in Cytoplasmic Particulates. Nature 1960, 186, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelder, N.M.; Elliott, K.A.C. DISPOSITION OF γ-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID ADMINISTERED TO MAMMALS. J Neurochem 1958, 3, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanaga, H.; Ohtsuki, S.; Hosoya, Ki; Terasaki, T. GAT2/BGT-1 as a System Responsible for the Transport of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid at the Mouse Blood-Brain Barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2001, 21, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.J.; Hamamoto, K.; Aoshima, H.; Hara, Y. Effects of Tea Components on the Response of GABA A Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 3954–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THANAPREEDAWAT, P.; KOBAYASHI, H.; INUI, N.; SAKAMOTO, K.; KIM, M.; YOTO, A.; YOKOGOSHI, H. GABA Affects Novel Object Recognition Memory and Working Memory in Rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2013, 59, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoto, A.; Murao, S.; Motoki, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Horie, N.; Takeshima, K.; Masuda, K.; Kim, M.; Yokogoshi, H. Oral Intake of γ-Aminobutyric Acid Affects Mood and Activities of Central Nervous System during Stressed Condition Induced by Mental Tasks. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.; Wade, A.R.; Penkman, K.E.; Baker, D.H. Dietary Modulation of Cortical Excitation and Inhibition. Journal of Psychopharmacology 2017, 31, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.J.; Cooper, M.A.; Simmons, R.D.J.; Weir, C.J.; Belelli, D. Neurosteroids: Endogenous Allosteric Modulators of GABAA Receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, S48–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, T.; Jelinek, H.F.; Viengkhou, V.; Johnston, G.A.; Matthews, S. Effect of GABA-Fortified Oolong Tea on Reducing Stress in a University Student Cohort. Front Nutr 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waagepetersen, H.S.; Sonnewald, U.; Schousboe, A. The GABA Paradox. J Neurochem 2002, 73, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoshima, H.; Tenpaku, Y. Modulation of GABA Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes by 13- <scp>l</Scp> -Hydoxylinoleic Acid and Food Additives. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 1997, 61, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-H.; Moon, Y.-J.; Oh, C.-H. γ -Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Content of Selected Uncooked Foods. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2003, 8, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamatsu, A.; Yamashita, Y.; Pandharipande, T.; Maru, I.; Kim, M. Effect of Oral γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Administration on Sleep and Its Absorption in Humans. Food Sci Biotechnol 2016, 25, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, J.-I.; Shin, Y.Y.; Chung, S.-E.; Shin, W.C. Safety and Efficacy of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid from Fermented Rice Germ in Patients with Insomnia Symptoms: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2018, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KANEHIRA, T.; NAKAMURA, Y.; NAKAMURA, K.; HORIE, K.; HORIE, N.; FURUGORI, K.; SAUCHI, Y.; YOKOGOSHI, H. Relieving Occupational Fatigue by Consumption of a Beverage Containing Γ-Amino Butyric Acid. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2011, 57, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, R.; Bajpai, V.K.; Baek, K.-H. Production of Gaba (γ - Aminobutyric Acid) by Microorganisms: A Review. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2012, 43, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.N.S.; Ryu, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, B.H. GABA-Enriched Fermented Laminaria Japonica Improves Cognitive Impairment and Neuroplasticity in Scopolamine- and Ethanol-Induced Dementia Model Mice. Nutr Res Pract 2018, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, C.; Angelucci, A.; Costantin, L.; Braschi, C.; Mazzantini, M.; Babbini, F.; Fabbri, M.E.; Tessarollo, L.; Maffei, L.; Berardi, N.; et al. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Is Required for the Enhancement of Hippocampal Neurogenesis Following Environmental Enrichment. European Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 24, 1850–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, M.F.; Kojima, M.; Callicott, J.H.; Goldberg, T.E.; Kolachana, B.S.; Bertolino, A.; Zaitsev, E.; Gold, B.; Goldman, D.; Dean, M.; et al. The BDNF Val66met Polymorphism Affects Activity-Dependent Secretion of BDNF and Human Memory and Hippocampal Function. Cell 2003, 112, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.; Morici, J.F.; Zanoni, M.B.; Bekinschtein, P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Lee, M.-S.; Shim, H.S.; Lee, G.-R.; Chung, S.Y.; Kang, Y.M.; Lee, B.-J.; Seo, Y.B.; Kim, K.S.; Shim, I. Fermented Saccharina Japonica (Phaeophyta) Improves Neuritogenic Activity and TMT-Induced Cognitive Deficits in Rats. ALGAE 2016, 31, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wouw, M.; Walsh, A.M.; Crispie, F.; van Leuven, L.; Lyte, J.M.; Boehme, M.; Clarke, G.; Dinan, T.G.; Cotter, P.D.; Cryan, J.F. Distinct Actions of the Fermented Beverage Kefir on Host Behaviour, Immunity and Microbiome Gut-Brain Modules in the Mouse. Microbiome 2020, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tınok, A.A.; Karabay, A.; Jong, J.D.; Balta, G.; Akyürek, E.G. Effects of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid on Working Memory and Attention: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. J Psychopharmacol 2023, 37, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonte, A.; Colzato, L.S.; Steenbergen, L.; Hommel, B.; Akyürek, E.G. Supplementation of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Affects Temporal, but Not Spatial Visual Attention. Brain Cogn 2018, 120, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzki, L.; Ostrowska, L.; Pawlak, D.; Małus, A.; Pawlak, K.; Waszkiewicz, N.; Szulc, A. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 299v Decreases Kynurenine Concentration and Improves Cognitive Functions in Patients with Major Depression: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo Controlled Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E.; Doll, J.P.K.; Schweinfurth, N.; Kettelhack, C.; Schaub, A.-C.; Yamanbaeva, G.; Varghese, N.; Mählmann, L.; Brand, S.; Eckert, A.; et al. Effect of Short-Term, High-Dose Probiotic Supplementation on Cognition, Related Brain Functions and BDNF in Patients with Depression: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2023, 48, E23–E33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamaladevi, N.; Jayakumar, A.R.; Sujatha, R.; Paul, V.; Subramanian, E.H. Evidence That Nitric Oxide Production Increases γ-Amino Butyric Acid Permeability of Blood-Brain Barrier. Brain Res Bull 2002, 57, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Takishima, T.; Kometani, T.; Yokogoshi, H. Psychological Stress-Reducing Effect of Chocolate Enriched with γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in Humans: Assessment of Stress Using Heart Rate Variability and Salivary Chromogranin A. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009, 60, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), Monograph. Altern Med Rev 2007, 12, 274–279.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).