1. Introduction

Hemoptysis may be a symptom of diverse respiratory conditions, and is due to lung cancer in about 20% of cases [

1]. Severity of hemoptysis can also vary, ranging from minimal blood-streaked sputum to immediate life-threatening hemorrhage. Effective management of significant hemoptysis includes several interventional procedures and bronchial artery embolization is now the first line treatment to control bleeding [

2]. In less than 10% of patients, hemoptysis originates from the pulmonary artery [

3] and is associated with increased mortality [

4]. Hemoptysis arising from the pulmonary artery may be traumatic (Swan-Ganz catheter), inflammatory (Behcet’s disease), infectious (tuberculosis with Rasmussen aneurysm, aspergillosis, …) or neoplastic [

5]. Several reports underlined the efficacy of pulmonary artery embolization in case of infectious [

6,

7,

8,

9] or inflammatory [

10] disease as well as in case of iatrogenic pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysms [

11]. Data regarding the use of pulmonary artery embolization in the management of hemoptysis related to lung tumors is still very limited [

12].

The goal of the present study was to evaluate safety and efficacy of pulmonary artery embolization in patients presenting with intractable hemoptysis related to lung tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

From December 2008 to December 2020, all lung cancer-related patients presenting with severe hemoptysis treated by pulmonary artery embolization in conjunction or after a failed bronchial artery embolization at the five participating centers were retrospectively included. The study was promoted by the Interbreizh Research Foundation. Ethical committee approval was obtained (registration number 2317). Patients treated with pulmonary embolization of other causes (traumatic or infectious pseudo-aneurysms, pulmonary arterio-venous malformations, …) during the study period were excluded.

Each patient was categorized by age, sex, previous medical history, histologic type of cancer, disease stage, previous therapies (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy), haemostasis abnormality, hemoptysis volume and hemodynamic status. Hemoptysis severity was graded on the basis of the quantity of expectorated blood: <50 mL of hemoptysis as minimal, 50 to 200 mL as medium, and > 200 mL in 24 hours as massive. All patients were examined with a 1-mm collimation computed tomography after administration of iodinated contrast material. Acquisitions were usually started 45 seconds after intravenous injection, to obtain maximum opacification of the pulmonary and bronchial arteries at the same time. Characteristics of the tumor (long diameter, location proximal vs distal, presence of necrosis or cavitation) were recorded. All include patients presented with pulmonary artery lesions considered to account for hemoptysis: proximal pulmonary artery invasion, irregularity of arterial wall or vessel narrowing, pseudoaneurysm and tumoral occlusion. The presence of enlarged bronchial arteries were analyzed. The presence of ground-glass attenuation or alveolar consolidations were also recorded.

2.2. Endovascular management

The initial approach to massive hemoptysis should always begin with airway management and hemodynamic stabilization. Anticoagulant medications should be held for the appropriate period of time and reversal agents employed if necessary. Airway isolation with bronchial blockers and endobronchial use of iced saline and vasoactive agents are among the conservative methods of hemoptysis management. Procedures were performed by 14 interventional radiologists with 2 to 15 years of experience performing embolization (MD, PhD). All interventional procedures were performed under conscious sedation or general anesthesia depending on the hemodynamic status of the patient with continuous monitoring by the intensive care and pulmonology physicians. After percutaneous introduction of a 6- to 9-Fr vascular sheath in the femoral vein, the pulmonary artery was selectively catheterized using a guiding catheter and different shapes of 5-Fr catheters. In case of distal vascular involvement, a 2.4-2.8-Fr microcatheter was used to superselectively catheterize the segmental artery causing bleeding. The choice of embolic agents was left at the operators’ discretion. The following embolization parameters were recorded: level of occlusion (distal/segmental, lobar or proximal), type of embolization agents, fluoroscopy time and total radiation dose. Particles, gelatin sponge pledgets, acrylic glue, metallic coils, vascular plugs or stent grafts were selected by the interventional radiologist. For patients undergoing bronchial embolization, after percutaneous introduction of a 5-Fr sheath in the femoral artery, selective catheterization of the different bronchial arteries was performed with 4 or 5-Fr catheters of different shapes. Target arteries were then superselectively catheterized with a 2.4-2.8-Fr microcatheter. The embolic agent used was microspheres sized between 400 to 900 μm from different vendors. After embolization, all patients were admitted to the intensive care unit.

2.3. Analysis of the Outcome

Technical success was defined as ability to perform super selective catheterization and embolization of target pulmonary artery branches. Clinical success was defined as cessation of bleeding after embolization. Procedure-associated recurrence of hemoptysis and deaths were evaluated as main outcomes in two separate analyses. Complications were classified according to the Society of Interventional Radiology grading system (minor vs major, graded from A to F) [

13]. Patient survival for both outcomes was assessed at 30 days, 6 months and at the end of the study, by the Kaplan-Meier estimator. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Follow-up was defined as time lap between inclusion and December 2020 or loss to follow-up date.

The Cox proportional hazards model for left-truncated and right-censored data was performed in the modelling of the time to the recurrence of hemoptysis and death, in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Potential confounding variables, chosen for their clinical relevance, are indicated in the footnotes of the tables. Analyses were performed using R, version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and RStudio, version 1.4.1717 (Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient population and analysis of imaging

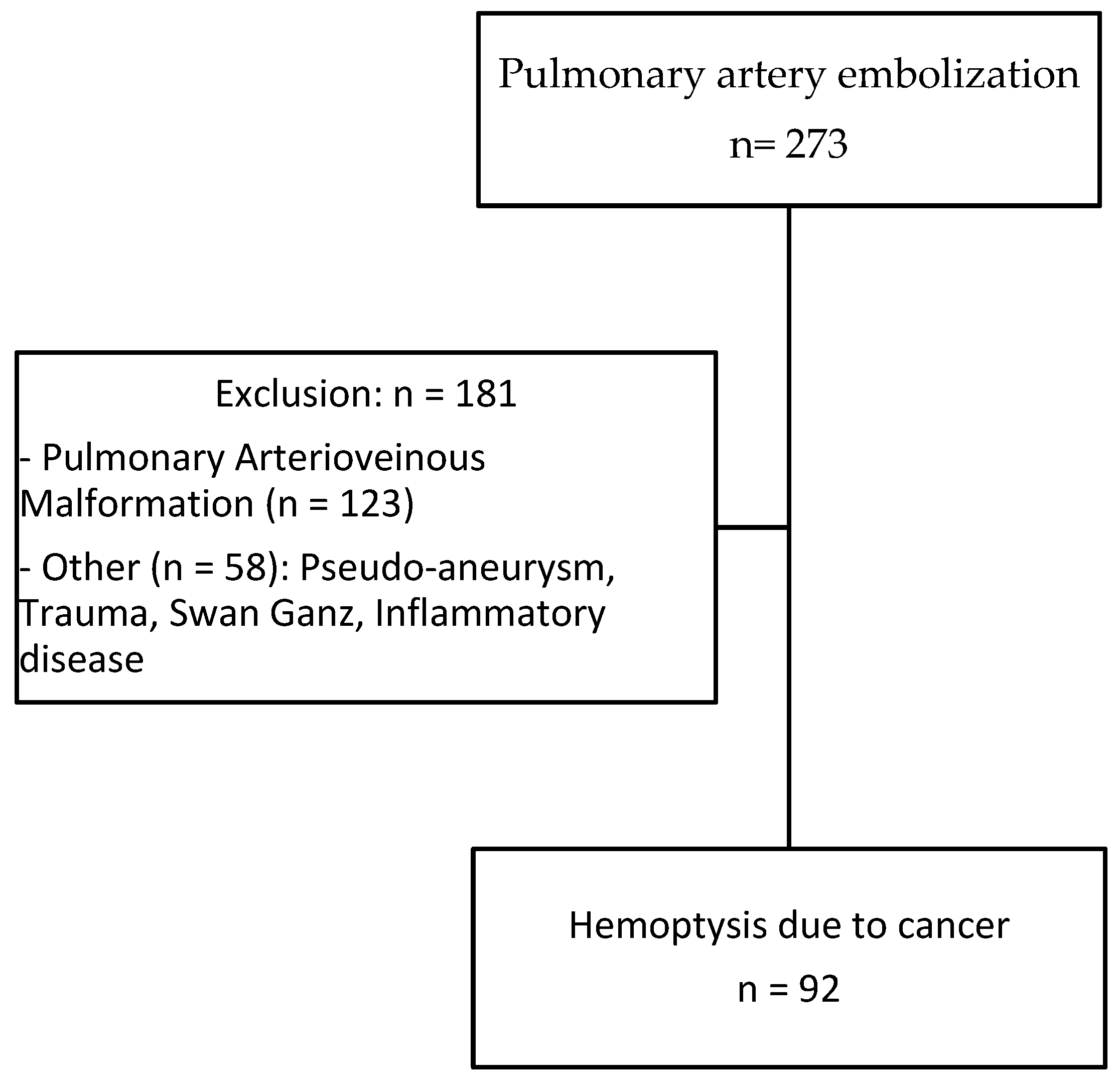

A total of 92 patients (70 men, 22 women) with hemoptysis in the context of cancer aged 63.1 ± 9.9 years treated by pulmonary artery embolization were included (

Figure 1). A total of 74 (94%) patients were smokers with an average of 45.1 ± 18.6 pack-years (median 40.0, min-max 10-120). Primary lung carcinoma was encountered in 80 (93%) patients whereas lung metastases and undetermined lesions were identified in 6 and 6 patients, respectively. Epidermoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma were the most common primary tumors identified in 50 (54%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively (

Table 1). Most of the patients had advanced disease with stage III or IV (97%). Cancer treatment included chemotherapy in 51 (55%), radiotherapy in 11 (12%) and surgical resection in 6 (6%) patients, respectively. Eighteen (20%) patients had hemostasis disorders or were treated with anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapies. Massive and medium hemoptysis were reported in 34 (37%) and 36 (39%) patients, respectively. The remaining patients had minimal but recurrent hemoptysis. Sixty-eight (74%) patients had stable hemodynamic condition and 24 (26%) presented with hemodynamic instability.

Eighty percent of tumors were centrally-located. The mean diameter was 75.2 ± 26.5 mm with 72% exhibiting necrosis and 47% cavitation. Arterial wall irregularity encountered in 45% of patients was the most frequent abnormality detected at CT. Tumoral occlusion and pseudoaneurysm caused by tumor invasion were found in 28% and 21% of cases, respectively. Ground glass attenuation was found in 51% of patients. Hypertrophic bronchial arteries were present in 22 (24%) patients. Imaging results are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Embolization procedure

A total of 12 patients underwent pulmonary artery embolization because of persistent or recurrent bleeding after bronchial artery embolization and 38 (41%) had bronchial and pulmonary embolization carried out at the same time. The remaining 42 (46%) patients had pulmonary artery embolization performed first, based on CT findings suggesting pulmonary artery as the source of bleeding.

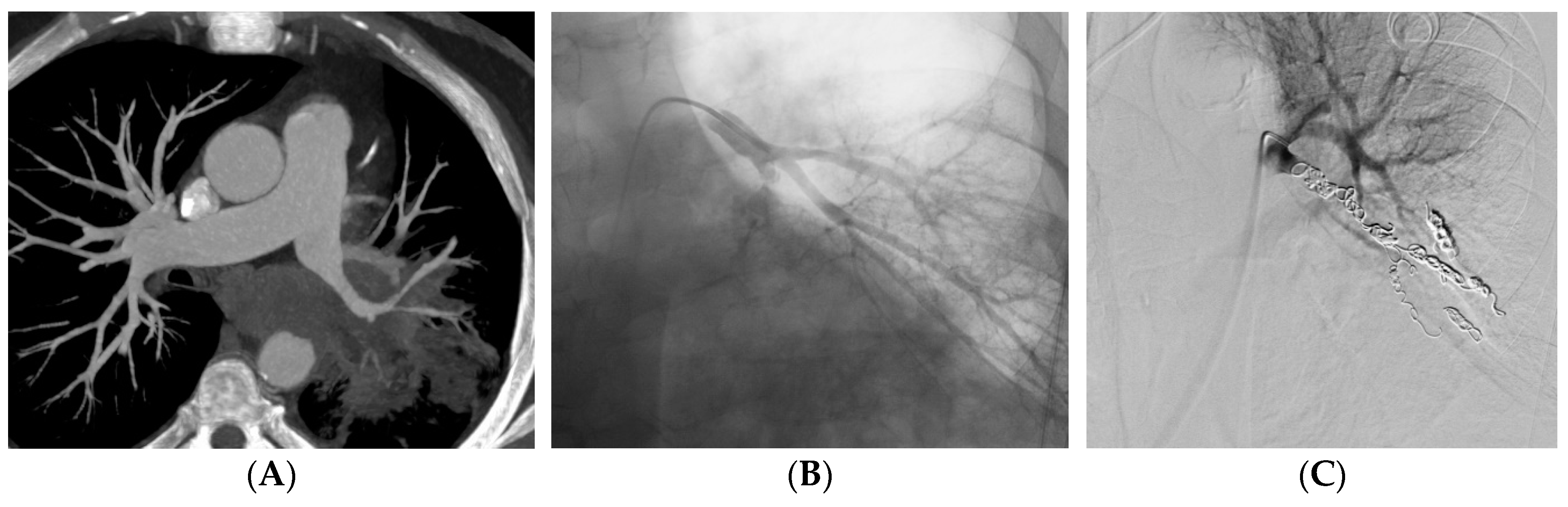

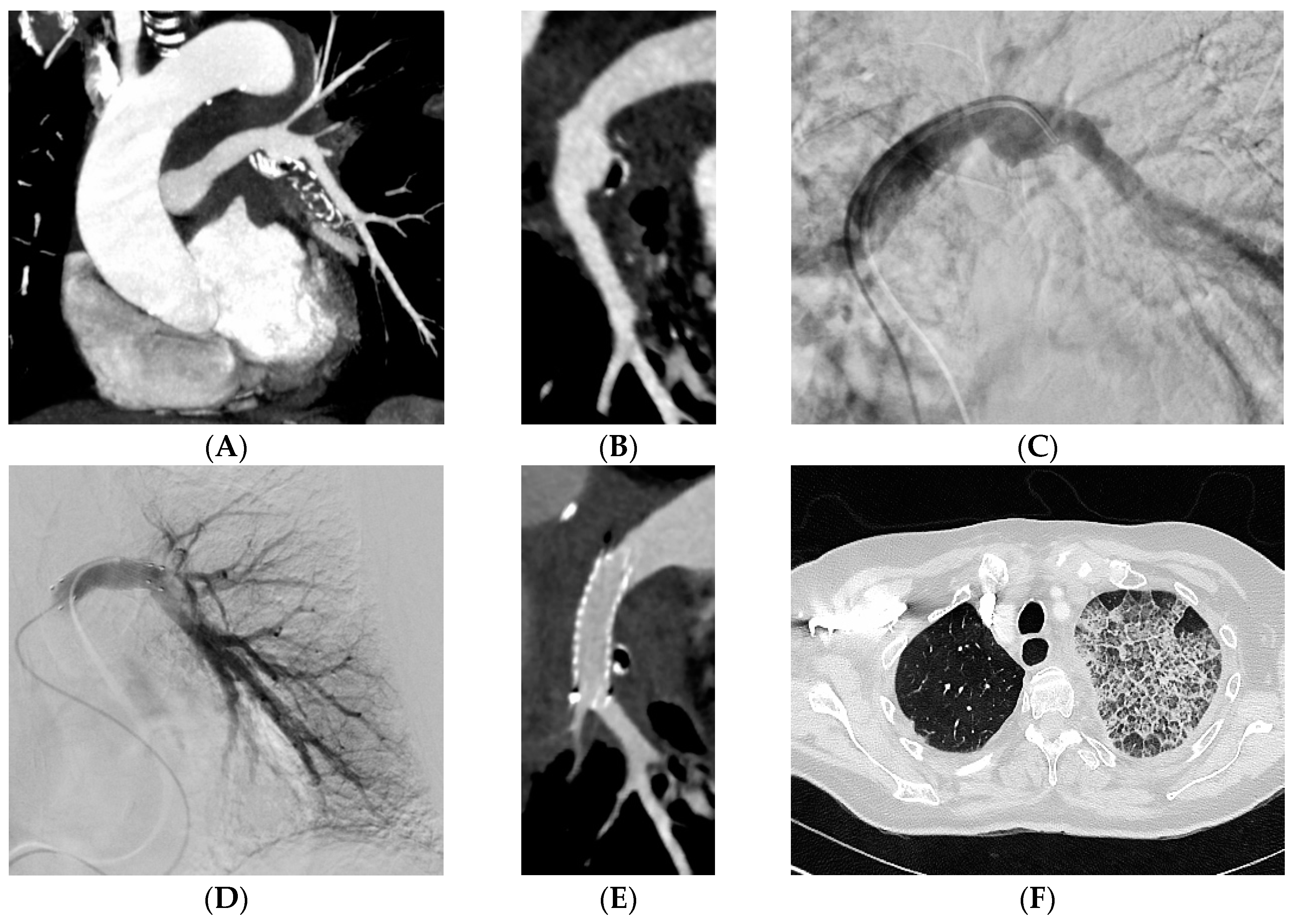

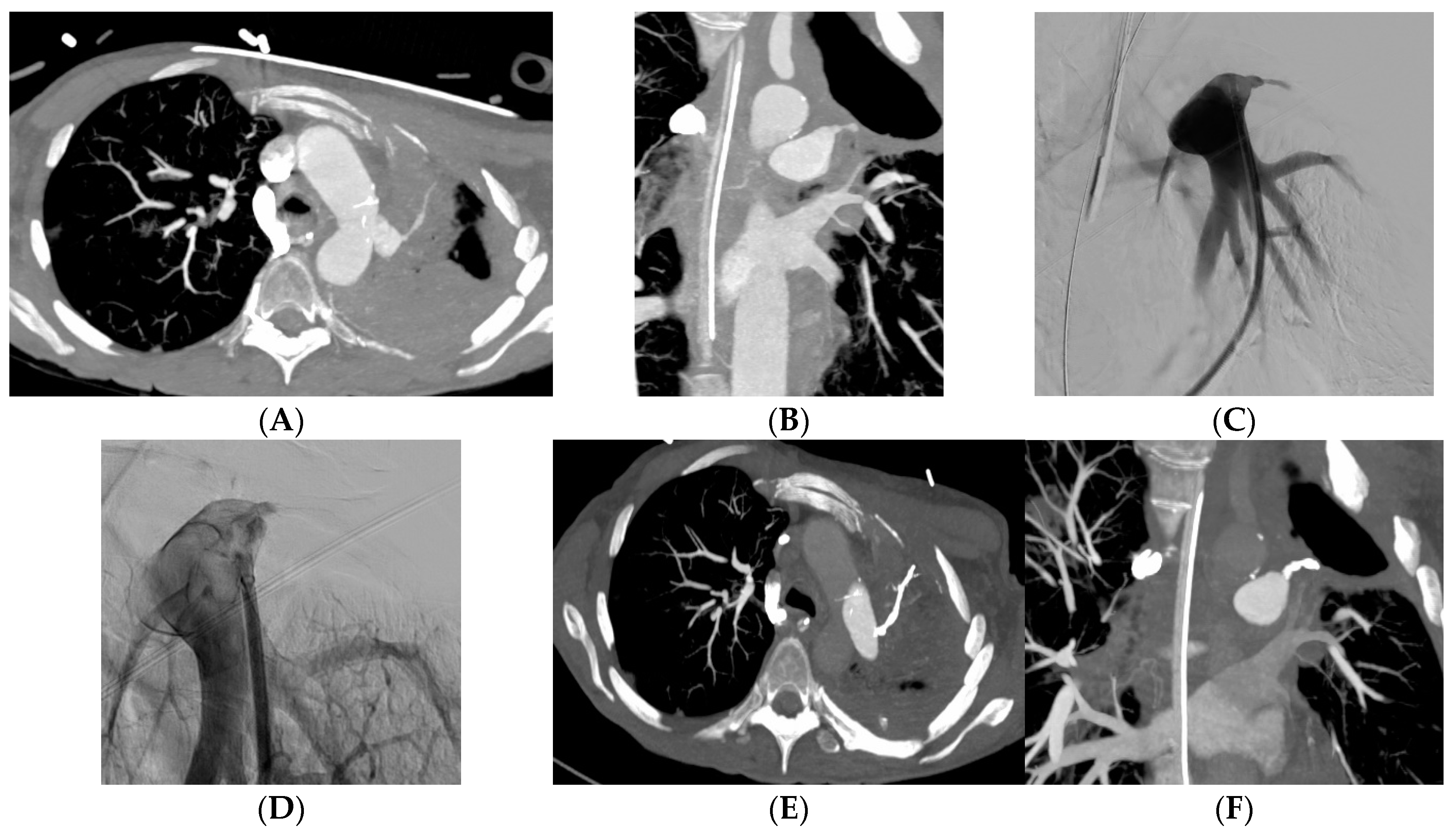

Embolization was carried out at the lobar level in 34 (37%) patients and more proximally in 31 (34%) patients (

Table 2). The material used for the embolization was coils in 35 (39%) patients (

Figure 2), a stent-graft in 29 (32%) patients (

Figure 3), acrylic glue in 13 (14%) patients (

Figure 4), a vascular plug in 12 (13%) patients and gelatin sponge in 1 (2%) patient. In 2 patients, the embolization material was not mentioned in the radiological report. Among the 90 patients, 15 patients had a secondary embolization device used including vascular plugs in 8 cases, metallic coils in 4 cases and gelatin sponge in 2 cases. Mean fluoroscopy time was 25.1

± 12.5 minutes (median 21.0; min-max 7.0-51.0) and mean radiation dose was 74,277.0

± 112,855.8 mGy.cm (median 42,548.0; min-max 2,109.0-567,047.0).

3.3. Clinical results and survival

Ten patients experienced hemoptysis during the procedure. Among them, 3 patients presented massive hemoptysis and 2 ruptures of pseudoaneurysm were reported. Technical success was reported in 82/92 (89%) patients and primary clinical success was 77/92 (84%).

Mean follow-up after embolization was 5.2 ± 9.4 months (median 1.7; range 0.0-66.8 months).

Three patients had recurrence within 24 hours post-embolization.

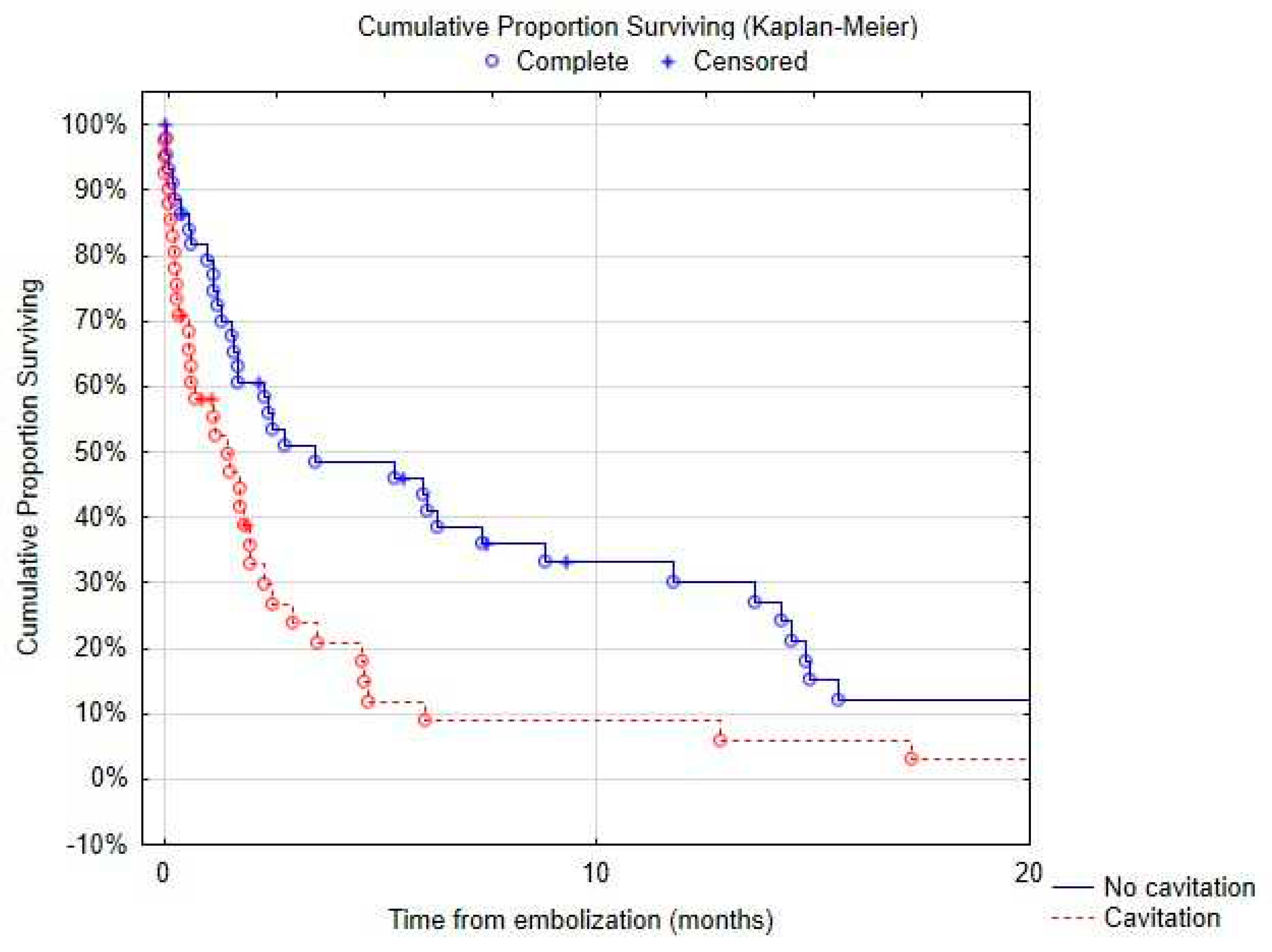

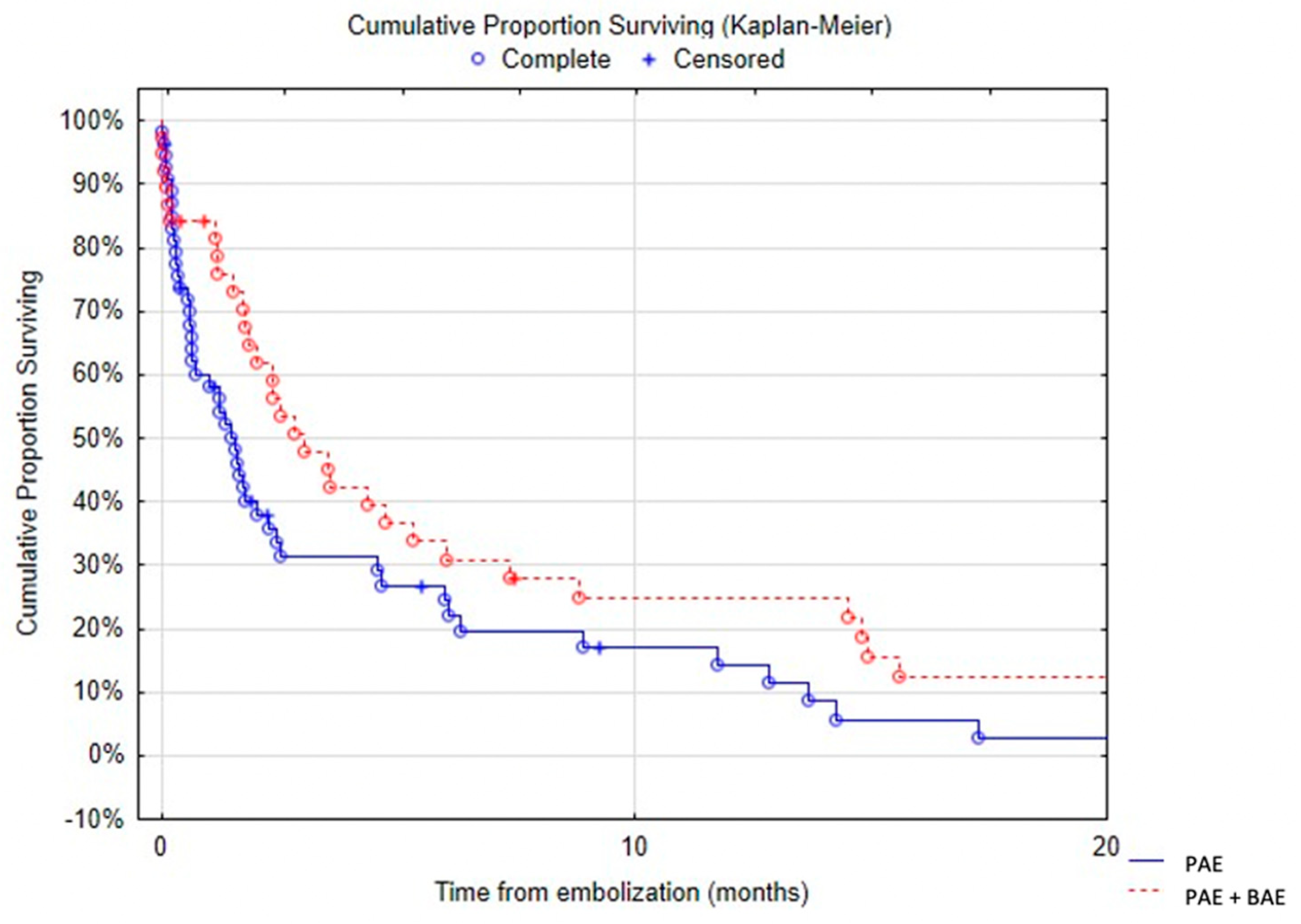

Of the 77 patients with available mid-term follow-up, delayed recurrence of hemoptysis occurred in 38 (49%) patients. Recurrence occurred after a mean of 71.1 ± 164.6 days (median 11.0; min-max 0-730.0). No difference was found in terms of recurrence rate between patients undergoing simultaneous pulmonary and bronchial artery embolization and those treated only with pulmonary artery embolization. Among patients with recurrence, 76% had proximal or lobar involvement. Variables significantly associated with recurrence in univariate analysis are listed in

Table 3 notably tumor size (p=0.004), presence of tumor cavitation (p=.004) or necrosis (p=.04). The presence of tumor cavitation (Hazard ratio HR 6.6, 95% confidence interval CI 1.5-29.4, p=.01) and pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm (HR 86.0, CI 2.9-2538.4, p=.009) were independently associated with higher risk of recurrence using multi-variate analysis (

Table 4). Recurrence occurred in 48% of patients treated with stents, 43% with coils, 23% with glue and 42% with plugs. Multivariate analysis demonstrated higher recurrence in patients treated with covered stents (HR 5.72, CI 1.3-25.6, p=.012) or gelatin sponge (HR 33.3, CI 1.0-1066.2, p=.05). Recurrence rate was lower in patients with epidermoid carcinoma using multivariate analysis (HR 0.13, CI 0.02-0.8, p= .03).

Infectious complications were reported in 15 (16%) patients including fever and pneumonia.

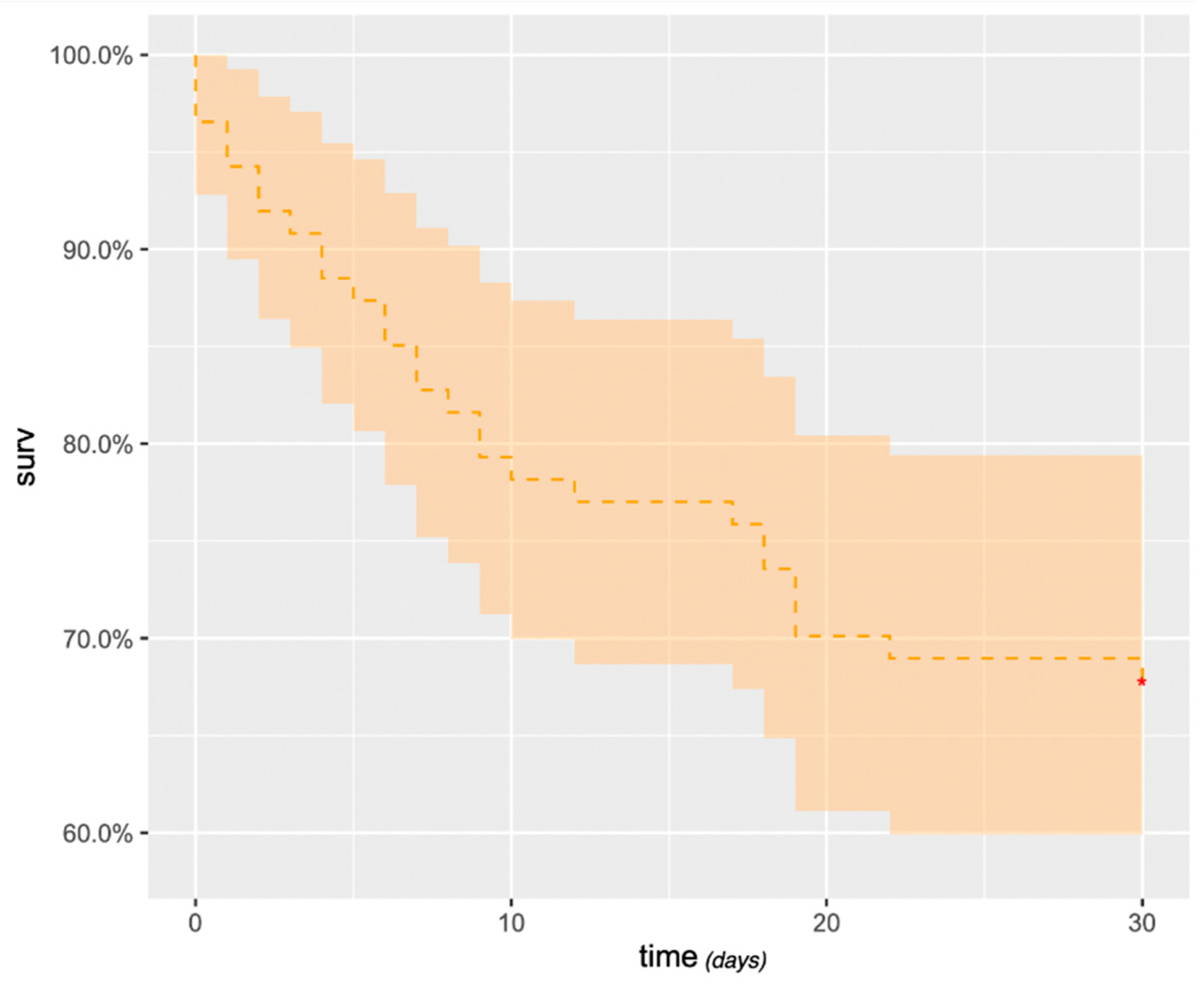

Survival after embolization at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months was 69% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 59%– 78%) (

Figure 5), 38% (95% CI: 28%–48%), 27% (95% CI: 17%–36%) and 19% (95% CI: 10%–27%), respectively. At 3 years, survival was 3.6% (95% CI: 0%–8%). Massive hemoptysis, tumor cavitation (

Figure 6) or necrosis were associated with increased mortality (

Table 5). There was a trend towards decreased survival in patients with arterial wall irregularity. Simultaneous pulmonary artery and bronchial artery embolization was associated with a significantly reduced mortality (

Figure 7). No difference was found in terms of survival between proximal and distal embolization. Variables associated with mortality in univariate analysis are listed in

Table 6 notably tumor size (p=.023), presence of tumor cavitation (p=.003) or necrosis (p=.02). Using a multi-variate analysis, the presence of tumor cavitation (HR 5.0, CI 1.8-13.43 p=.001) and pulmonary artery pseudo-aneurism (HR 13.9, CI 2.0-95.4, p=.007) were independently associated with shorter survival (

Table 7). Multivariate analysis demonstrated shorter survival in patients treated with covered stents (HR 6.2, CI 12.1-18.3, p<.001) or gelatin sponge (HR 21.2, CI 1.3-349.8, p=.03). Using multivariate analysis, patients with epidermoid carcinoma had better survival (HR 0.34, CI 0.12-1.0, p=.05).

4. Discussion

Life-threatening or recurrent hemoptysis remains an important clinical concern for chest physicians. CT angiography permits noninvasive, rapid and accurate assessment of the cause and guides subsequent management [

14]. In the large majority of cases, the source of hemorrhage is of systemic origin with bronchial artery embolization used as a first line effective treatment. Control of hemoptysis can be achieved in 65 to 92 % of cases depending on the cause [

15]. The main causes of treatment failure are technical challenges and bleeding originating from the pulmonary artery. However, lesions of pulmonary artery branches are not routinely described in radiological reports. Indeed, one study showed that only 46% of pulmonary arteries abnormalities were identified on the initial CT studies [

16]. Patients presenting with large tumors and associated pulmonary artery pseudo-aneurisms may benefit from an initial pulmonary artery embolization.

It has been estimated that up to 30% of patients with lung cancer will present hemoptysis and, of these, 10% will experience massive hemoptysis [

17]. Hemoptysis can also reveal cancer [

1]. In patient with tumor-related hemoptysis, overall survival remains low and recurrence is reported in 20 to 30% of cases [

17,

18]. There is no difference in terms of survival between patients who had previously undergone radiation therapy or not [

19].

There are only few studies reporting the use of pulmonary artery embolization and there is no consensus opinion on indications and technique. In previous reports, some authors recommended pulmonary artery embolization only after failure or recurrence of bronchial artery embolization [

2] whereas others recommended pulmonary artery embolization when an abnormality was detected on pulmonary artery at CT [

3,

9]. Marcelin and al, reported that 7 out of 12 patients treated with pulmonary artery embolization first underwent bronchial artery embolization. They have not reported any case of simultaneous embolization of both circulations [

12]. However, our data suggests that pulmonary and bronchial embolization performed at the same time may be associated with increased survival. In addition, for proximal involvement, there is no consensus opinion whether the pathological branches should be occluded with glue or coils, or if the parent pulmonary artery should be spared using a stent graft. Previous reports recommended stent graft placement for proximal pulmonary abnormalities to maintain vessel patency and minimize lung functional loss [

12,

15]. In our practice, when feasible, a ventilation-perfusion lung scintigraphy is obtained prior to proximal embolization to estimate the respective contribution of each lung to the overall function. Nuclear medicine studies are difficult to obtain on an emergency basis and are often not feasible in patients with unstable hemodynamic condition. A higher recurrence and mortality were found in patients embolized with stent grafts. Treatment of proximal lesions may explain these results.

Despite a high technical success rate and initial clinical efficacy associated with embolization, the overall prognosis remains poor. Not surprisingly in patients with stage III or IV large lung tumors, the 1-year survival rate was 19% in our study. It is well known that pulmonary artery involvement in lung cancer is associated with increased mortality in patients with hemoptysis [

4]. The presence of a large or excavated lesion or a pseudo-aneurism seems to be associated with a poor prognosis. In our series, compared to the experience of Marcelin and al. [

12], the survival rate was lower (i.e. 38% versus 67% at 3 months) and the recurrence rate was also much higher (i.e. 49% versus 0%). The differences we found may be probably due to the small number of highly selected patients (19 patients) in the former study, which may have led to an underestimation of overall mortality and recurrence. In addition, there was little descriptive data about the tumor in their study, especially regarding the size of the tumor. Furthermore, the higher number of treatments using stent graft for proximal lesions in our series, 32% versus 16% for Marcelin [

12] may have played an important role. Complications associated with pulmonary artery embolization are mainly infectious complications reported in 16% of cases in our study. No complication was noted by Marcelin and al [

12]. Deaths due to massive hemoptysis during the procedure have been reported in our series and also in several studies [

12,

20]. The rupture of the pulmonary artery might have been caused by increased pressure during superselective injection and also by the repeated friction of the catheter tip on the fragile pulmonary artery.

Our study has some limitations. It was designed as retrospective, one-sample cohort with no control group. The small population size could be considered another limitation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, pulmonary artery embolization is an effective treatment to control hemoptysis in patient with lung carcinoma. However, recurrence rate remains high and overall survival remains poor with less than 5% of patients still alive at 3 years. Pulmonary arterial embolization is not technically easy, the indication should be discussed in a pluridisciplinary tumor board. Special attention should be paid to patients with large, excavated or necrotic tumors or when a pseudoaneurysm is visualized, given the high risk of recurrence and early death.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdulmalak, C.; Cottenet, J.; Beltramo, G.; Georges, M.; Camus, P.; Bonniaud, P.; Quantin, C. Haemoptysis in Adults: A 5-Year Study Using the French Nationwide Hospital Administrative Database. European Respiratory Journal 2015, 46, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, J.Y.; Morgan, R.; Belli, A.M. Radiological Management of Hemoptysis: A Comprehensive Review of Diagnostic Imaging and Bronchial Arterial Embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010, 33, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Parrot, A.; Nedelcu, C.; Fartoukh, M.; Marsault, C.; Carette, M.F. Severe Hemoptysis of Pulmonary Arterial Origin: Signs and Role of Multidetector Row CT Angiography. Chest 2008, 133, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fartoukh, M.; Khoshnood, B.; Parrot, A.; Khalil, A.; Carette, M.F.; Stoclin, A.; Mayaud, C.; Cadranel, J.; Ancel, P.Y. Early Prediction of In-Hospital Mortality of Patients with Hemoptysis: An Approach to Defining Severe Hemoptysis. Respiration 2012, 83, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelage, J.P.; el Hajjam, M.; Lagrange, C.; Chinet, T.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Chagnon, S.; Lacombe, P. Pulmonary Artery Interventions: An Overview. In Proceedings of the Radiographics, November 2005; Volume 25, pp. 1653–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Piracha, S.; Mahmood, A.; Qayyum, N.; Ganaie, M.B. Massive Haemoptysis Secondary to Mycotic Pulmonary Artery Aneurysm in Subacute Invasive Aspergillosis. BMJ Case Rep 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo-Montoya, Á.M.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Hernández-Hurtado, J.D.; López-Salazar, Á.; Lagos-Grisales, G.J.; Ruiz-Granada, V.H. Rasmussen Aneurysm: A Rare but Not Gone Complication of Tuberculosis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018, 69, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukada, J.; Hasegawa, I.; Torikai, H.; Sayama, K.; Jinzaki, M.; Narimatsu, Y. Interventional Therapeutic Strategy for Hemoptysis Originating from Infectious Pulmonary Artery Pseudoaneurysms. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2015, 26, 1046–1051.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbano, H.; Mitchell, A.W.; Ind, P.W.; Jackson, J.E. Peripheral Pulmonary Artery Pseudoaneurysms and Massive Hemoptysis. American Journal of Roentgenology 2005, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ference, B.A.; Shannon, T.M.; White, R.I.; Zawin, M.; Burdge, C.M. Life-Threatening Pulmonary Hemorrhage with Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations and Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Chest 1994, 106, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudziński, P.N.; Henzel, J.; Dzielińska, Z.; Lubiszewska, B.M.; Michałowska, I.; Szymański, P.; Pracoń, R.; Hryniewiecki, T.; Demkow, M. Pulmonary Artery Rupture as a Complication of Swan-Ganz Catheter Application. Diagnosis and Endovascular Treatment: A Single Centre’s Experience. Postepy w Kardiologii Interwencyjnej 2016, 12, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelin, C.; Soussan, J.; Desmots, F.; Gaubert, J.Y.; Vidal, V.; Bartoli, J.M.; Izaaryene, J. Outcomes of Pulmonary Artery Embolization and Stent Graft Placement for the Treatment of Hemoptysis Caused by Lung Tumors. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2018, 29, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.; McClenny, T.E.; Cardella, J.F.; Lewis, C.A. Society of Interventional Radiology Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2003, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzzi, J.F.; Rémy-Jardin, M.; Delhaye, D.; Teisseire, A.; Khalil, C.; Rémy, J. Multi-Detector Row CT of Hemoptysis. Radiographics 2006, 26, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, A.; Fedida, B.; Parrot, A.; Haddad, S.; Fartoukh, M.; Carette, M.F. Severe Hemoptysis: From Diagnosis to Embolization. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015, 96, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Gilman, M.D.; Humphrey, K.L.; Salazar, G.M.; Sharma, A.; Muniappan, A.; Shepard, J.A.O.; Wu, C.C. Pulmonary Artery Pseudoaneurysms: Clinical Features and CT Findings. American Journal of Roentgenology 2017, 208, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, Y. il; Kim, H.Y.; Zo, J.I.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Bronchial Artery and Systemic Artery Embolization in the Management of Primary Lung Cancer Patients with Hemoptysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007, 30, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Olivé, I.; Sanz-Santos, J.; Centeno, C.; Andreo, F.; Muñoz-Ferrer, A.; Serra, P.; Sampere, J.; Michavila, J.M.; Muchart, J.; Manzano, J.R. Results of Bronchial Artery Embolization for the Treatment of Hemoptysis Caused by Neoplasm. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2014, 25, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.R.; Ensor, J.E.; Gupta, S.; Hicks, M.E.; Tam, A.L. Bronchial Artery Embolization for the Management of Hemoptysis in Oncology Patients: Utility and Prognostic Factors. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2009, 20, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, T.B.; Yoon, S.K.; Lee, K.N.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Sung, C.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, C.W. The Role of Pulmonary CT Angiography and Selective Pulmonary Angiography in Endovascular Management of Pulmonary Artery Pseudoaneurysms Associated with Infectious Lung Diseases. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2007, 18, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).