1. Introduction

On May 2022, a rapidly spreading mpox outbreak appeared and it was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO), on July 23, 2022 [

1,

2]. Compared to all previous mpox epidemic events, the 2022-2023 outbreak presented a peculiar pattern in terms of transmission-associated factors, unusually high frequency of interhuman transmission, and clinical presentation [

3,

4,

5,

6]. For this reason, vaccination against mpox (MpoxVax) was promptly recommended for individuals at high-risk of exposure. Even in Italy, the third-generation modified, non-replicating live Ankara vaccine virus, produced by Bavarian Nordic MVA-BN, was authorized by the Italian Ministry of Health as mpox pre-exposure prophylaxis in adults at high risk of infection [

7]. However, while vaccination is often cited as one of the most effective methods to control the spread of infectious diseases, some individuals are still hesitant to accept receiving vaccinations. Vaccine hesitancy, defined as delayed acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccine services [

8], was identified by the WHO as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019 [

9] and it remains a widespread problem in the general population. More generally, vaccine acceptance is defined as the individual or group decision to accept or refuse, when presented with an opportunity to vaccinate, and it can be active (adherence by an informed public that perceives the benefit of and the need for a vaccine) or passive (compliance by a public that defers to recommendations and social pressure) [

10,

11]. It is well recognized that vaccination intention does not always correlate with actual behaviour, and similarly, vaccine acceptance is not synonymous with vaccine uptake. To date, most studies focused on vaccine acceptance have assessed individuals' intention to receive the vaccine, rather than their explicit acceptance of the available vaccine itself [

12]. Hesitation towards vaccines is context-specific and influenced by factors such as convenience, confidence, risk perception, and ease of access to disease information and immunization services. [

8]. Moreover, sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, geographic area of residence, fear of adverse effects, or distrust of medical personnel and the health care system may influence vaccination decision-making [

12,

13].A number of studies have been published evaluating people’s willingness to accept MpoxVax, including both the general population [

14] and high-risk individuals [

8,

15,

16] but, with the exception of a few recent reports focusing on mpox vaccine uptake in a small number of subjects [

17,

18,

19], data on its determinants are lacking. In the Lazio Region, vaccination coverage has been estimated at around 44% of potentially eligible people, and in order to increase uptake, tools need to be identified [

20]. Therefore, we planned to measure the willingness to accept and receive MpoxVax, by analyzing associated empirical factors, including health-related quality of life (HRQoL), through a survey administered at the time of vaccination to participants in the MPOX-VAC study conducted during the MpoxVax campaign in the Lazio region of Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, study population and ethics

MPOX-VAC is an ongoing prospective observational and monocentric study conducted at the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani” IRCCS in Rome, Italy, enrolling high–risk persons who underwent MpoxVax, with the aims of monitoring safety, efficacy, immunogenicity, and acceptability of the MVA-BN vaccine. The study protocol (MPOX-VAC Study, version 1.0, August 23, 2022), was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute (approval number:41-z 2022) and all the included subjects signed an informed consent (version 1.0, August 23, 2022), for study participation and processing of personal data. Adult individuals (18 years or older) who met the criteria for priority access to MpoxVax, according to current Ministerial guidelines [

3], and had access to MpoxVax at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases ‘L. Spallanzani’ IRCCS, the only regional hub in Lazio, were considered eligible for the study. The target population of the vaccination campaign, according to the Ministry of Health indications, was defined as gay, bisexual, or other MSM (Men Who Have Sex with Men), reporting multiple sexual partners; participation in group sex events; sexual encounters in clubs/cruises/saunas; recent sexually transmitted infections; or with sexual acts associated with the use of chemical drugs. Subjects who were unable or refused to sign the informed consent, those excluded from vaccination due to clinical contraindications, ongoing acute illness, or previous mpox infection, and those lacking basic knowledge of the Italian language, were excluded from the study. Dedicated internet pages on institutional and association websites were used to disseminate information on the vaccination campaign to the target population. Herein, we report the results of a cross-sectional analysis including all the individuals referred to the MpoxVax campaign in the Lazio region, from August 8th, 2022 (vaccination campaign start) to January 13th, 2023, and enrolled in the MPOX-VAC study. Individuals were asked to fill out an anonymous survey of 17 multiple-choice questions on demographics, perceived risk for mpox infection, sexual behavior, vaccination attitude, and perceived health status (Short Form Health Survey 36 questionnaire; SF-36). All the information (clinical, demographic, and behavioral data) was collected in an Electronic Case Report Form (eCRF); partecipants were identified by numeric codes only, and password protected.

2.2. Vaccine Adherence Questionnaire

In this study, the instrument used to conduct the behavioral survey was identified and constructed by a team of neuropsychologists, infectious diseases, and epidemiology specialists. The questionnaire, consisting of 17 items, was divided into two sections: i) the demographic profile section, exploring demographic and biographical information such as sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, education, and work activity; in addition, individuals were asked to indicate their source of information for MpoxVax and the perceived quality of the information received, to indicate their motivation for vaccination (whether voluntary or under medical indication), and;ii) the sexual conduct section, inquiring about the number of partners in the last month, use of contraceptives, number of sexual intercourses with HIV-infected individuals, use of substances and alcohol, number of sexual intercourses under the use of substances and alcohol, and, finally, exploring the perceived risk of acquiring Mpox compared to general population based on sexual behaviors.

2.3. SF-36 questionnaire

HRQoL and self-perception of health status [

21] were assessed through the administration of the validated Italian version of the SF-36 questionnaire [

22], a 36-item self-administered questionnaire with a high degree of reliability [

23,

24]. Eight health domains can be obtained from the SF-36: physical role functioning (PF, 10 items), role limitations–physical (RP, 4 items), bodily pain (BP, 2 items), general health perceptions (GH, 5 items) pertaining to physical health (PH), besides vitality (VT, 4 items), social role functioning (SF, 2 items), emotional role functioning (RE, 3 items), and mental health (MH, 5 items) pertaining instead to mental health (MH). The 8 domains contribute to two different scores: a mental health component summary (MCS) and a physical health component summary (PCS). Individuals can rate their responses on a three- or six-point scale and the summed scores of those responses are then coded and transformed into a scale from 0 (worst health) to 100 (best health) [

25].

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive characteristics were provided using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical ones. Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare participants’ characteristics and survey responses in the two groups (vaccination ≤60 versus >60 days from the vaccination campaign start). Two endpoints were established: a) ‘delayed acceptance’of mpox-Vax (defined as access for vaccination more than 60 days from the campaign starting); b) ‘early acceptance’ of MpoxVax (defined as access for vaccination less than 30 days from the campaign starting). Logistic regression models were used to assess the association between demographic/behavioural factors and the two endpoints.The following factors were investigated as potential predictors of the two selected endpoints: age, sexual orientation, HIV status, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use, ethnicity, perceived risk of mpox, perceived quality of information on vaccination, educational level, number of sexual partners, use of drugs/chems and alcohol, MCS and PCS scores of the SF-36. Potential confounders, and adjustment sets, for each of the exposure of interest, were identified according to the assumptions showed in the directed acyclic graph (DAG) in Supplemental

Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

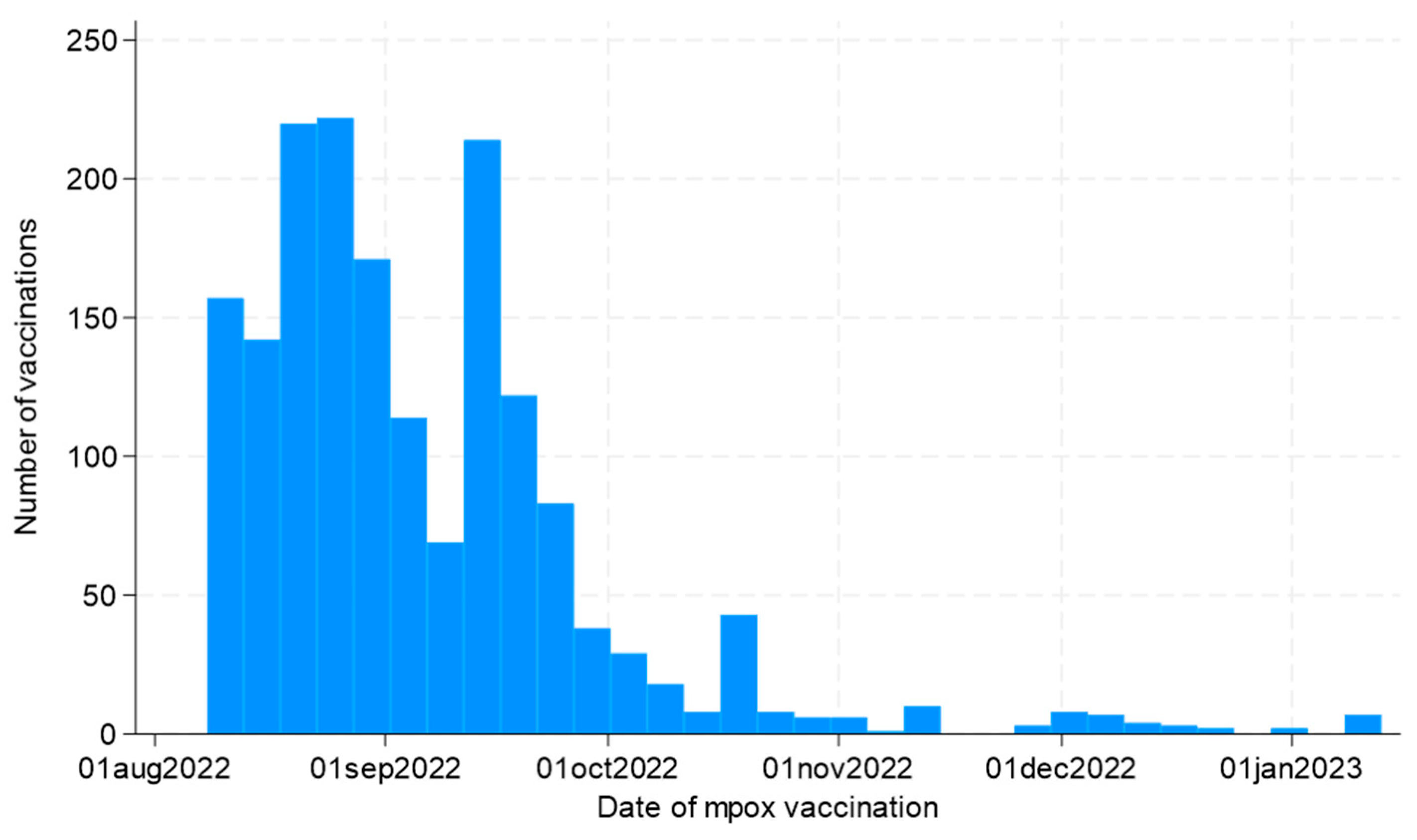

Overall, 1717 participants answered the questionnaires and underwent vaccination. As shown in

Figure 1, the vaccination campaign started on August 8th, 2022, and was characterized by an initial extensive adherence, especially in the first 2 months of the campaign, and a subsequent progressive decrease over time.

General characteristics of the study population and comparisons between the two groups are shown in

Table 1. Among 1717 participants, 129 individuals (7%) had delayed access to vaccination (>60 days from the vaccination campaign start) and 1588 (92.5%) had early access (<30 days). In particular, in the first group of 129 individuals, the median age was 38 (IQR 31-46) with most respondents older than 45 years (87, 67.4%) and 105 (81.4%) were Caucasian;while in the second group of 1588 subjects, the median age was 39 (33-46), 1092 (68. 8%) were older than 45 years and 1354 (85.2%) were Caucasian. Participants were mainly HIV negative (63.6% versus 72%, p =0.074), among these 191 (11.1%) were on PrEP (6.2% versus 11.5%, p =0.048). With regards to the sexual orientation and conduct, participants were mainly homosexual (84.5% versus 93.3%, p <0.001) and the proportions of respondents reporting a higher perceived risk of contracting mpox disease compared to the general population (57.3% versus 63.5%, p=0.002), use of recreational drugs during the last month (17.8% versus 17.3%, p=0.933) and sexual intercourse with alcohol or drugs in the last month (18.6% versus 20.3%, p=0.875) were similar between the two groups.

3.2. Analysis of ‘delayed acceptance’

By fitting separate multivariate logistic regression models for each of the exposures of interest on delayed acceptance endpoint, we observed that bisexual orientation [versus homosexual, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 3.22; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.77-5.84], lower education level (versus high school/university, AOR 3.65; 95%CI 1.83-7.28) and reporting a worse perceived physical (per 10 points lower of SF-36 PCS, AOR 1.16; 95%CI 1.02-1.32) and mental health status (per 10 points lower of SF-36 MCS, AOR 1.13; 95%CI 1.02-1.23) were associated with delayed vaccination. On the contrary, participants with a high perceived risk for mpox infection compared to the general population, showed a lower risk for delayed access to vaccine (AOR 0.61; 95%CI 0.41-0.91) (

Table 2).

3.2. Analysis of ‘early acceptance’

Using the same approach, for the early acceptance endpoint, being PrEP users and, marginally, HIV positive (versus HIV negative not on PrEP, AOR 1.97; 95%CI 1.37-2.82 and AOR 1.24; 95%CI 0.99-1.57, respectively), a bisexual orientation (versus homosexual, AOR 0.29; 95%CI 0.18-0.47), having a high perceived risk for mpox infection (AOR 1.43; 95%CI 1.13-1.82) and reporting high-risk behaviors like the use of recreational drugs (AOR 1.49, 95%CI 1.11-2.00), sex under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol (AOR 1.78; 95%CI 1.36-2.34) and higher number of principal sexual partners (per 1 more, AOR 1.07; 95%CI 1.03-1.11), were associated with early vaccination, along with receiving poor or none information on mpox vaccination (AOR 2.91; 95%CI 1.53-5-55). (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Our data show that, in our population, individuals with a high degree of risk awareness for mpox infection and reporting high-risk behaviors, such as PrEP users and people living with HIV, have access to vaccine in the first 30 days of the vaccination campaign. These results are in accordance with the prioritization criteria of the Italian vaccination campaign. Conversely, a bisexual orientation, a lower education level and reporting a worse perceived physical and mental health status compared to the general population, were critical factors associated with a delayed vaccination access. We therefore see how a number of local, racial, religious and cultural factors, along with several other aspects, including misinformation, can influence people's perceptions of vaccination acceptance, as was clearly observed in the recent COVID-19 pandemic and related vaccination [

26]. In fact, similarly in a recent study, willingness to accept vaccination was observed in 1859 respondents (938 were eligible for primary preventive vaccination and 918 were non-eligible). Of all of them, 81.5% were willing to accept vaccination, with 85% in those eligible (52% used HIV-PrEP , 24% were living with HIV, over the past 3 months 40% reported group sex, 66% reported unprotected anal intercourseduring casual sex, and 70% reported more than three sex partners) and 78% in those non-eligible (HIV negative/untested; none used HIV-PrEP, over the past 3 months 15% reported group sex, 23% reported UAI during casual sex, 25% reported more than three sex partners and 12% used drugs during sex). 12% were unwilling to accept vaccination; this was 10% in those eligible and 13.5% in those non-eligible [

15]. Other findings of current literature indicated a moderate prevalence of Mpox vaccine acceptance (56%), higher in Europe (70%) and lower in Asia (50%) due to the higher incidence in Europe and probably higher associated perception of risk and impact [

27]. Also, as expected, the acceptance of mpox vaccine was lower in the general population (43%) and higher in the LGBTI population (84%), according to the risk to be infected by mpox [

27]. All our study participants asked for vaccination spontaneously, particularly PrEP users and people living with HIV, because they felt more at risk than the general population. This finding is partially consistent with a French survey that reported that, of 402 PrEP users, 369 (87.0%) have been vaccinated against mpox, which most had sought vaccination spontaneously during the summer of 2022. Interestingly, half of the PrEP users who refused vaccination did not feel themselves at risk, probably because, as also described in another French survey, MSM on PrEP reported having few sexual partners [

16,

17]. Thus, among the most frequently reported beliefs for MpoxVax acceptance, we find risk awareness and motivation to protect oneself from infection. Public health communication messages should include more factual information about the risk of exposure, transmission routes, symptoms, and side effects of the vaccine, through awareness-raising campaigns on institutional and non-institutional websites and social platforms. This should encourage a person who has a high risk of exposure to feel himself at risk and to evaluate mpox as potentially serious and the vaccine as beneficial. On the contrary, a lower level of education was a critical factor for delaying vaccination; a similar result was found in a recent study in which the odds of being neutral (as opposed to being willing) towards the mpox vaccine were higher for those with a lower level of education [

15]. Bisexual orientation also emerges as a critical factor for vaccination delay; similarly, in a study comparing the socio-demographic characteristics of eligible participants according to vaccination status, statistically significant differences were found according to gender identity and sexual identity: out of a sample of 331 participants, not being vaccinated was more common, along other characteristics, among bisexuals (31.4% unvaccinated versus 9.4% vaccinated, p < 0.001) [

19].Not surprisingly, the perception of a worse state of physical and mental health in those who access late vaccination could explain the lack of motivation to vaccinate earlier and the increased fear of the side effects of the vaccine on their own condition of health.The strengths of this study were mainly represented by the large sample size and the timing of the survey, in terms of timeliness of data recording, with data collection beginning close to the start of the vaccination campaign, and a large investigation period (six months of data collection), together with the evaluation of a wide range of epidemiological determinants. The limitations of our study were, first of all, a probable self-choice bias of our sample, consisting essentially of individuals who voluntarily underwent vaccination, and a cross-sectional study, so no causality can be established. Also, our sample did not include women. Although MSM constitutes the majority of current Mpox cases in the United States and European countries, all are at risk regardless of their sexual identity. Another limit is represented by the fact that was a single-center analysis, which may impact the generalizability of the results even though it was the only regional reference center and the characteristics of the study participants conform to the vaccination target population. In addition, the lack of a comparison sample composed of unvaccinated subjects upon which to associate our data represents another important limitation of the study, so further research needs to be conducted in these terms.

5. Conclusions

Vaccine hesitancy and acceptance are key determinants of vaccination coverage that should be assessed and consequently addressed with evidence, education, and promotion as part of disease prevention campaigns, including mpox. Therefore, even in the case of mpox, it seems critical to emphasize the need for immunization as an essential public health intervention to contain infection transmission and disease development. In our study, risk awareness was confirmed as a major determinant of vaccination acceptance, along with the need to receive good-quality information about the disease and vaccination. These findings could be a useful tool, at a public health level, for identifying strategies to encourage vaccine acceptance and address vaccine uncertainty or increase uptake.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) depicting the assumed underlying causal paths between the different exposure of interest (A-L) and the 2 binary outcomes of vaccination timing. Age is unconfounded by definition but in order to increase the precision of the estimates logistic models have been adjusted for a strong adjusted for a strong predictor of the outcome as age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Giulia Del Duca, Alessandro Tavelli, Ilaria Mastrorosa, Valentina Mazzotta and Andrea Antinori; Data curation, Jessica Paulicelli, Giorgia Natalini and Angela D'Urso; Formal analysis, Alessandro Tavelli; Funding acquisition, Enrico Girardi and Andrea Antinori; Investigation, Giulia Del Duca; Methodology, Giulia Del Duca, Alessandro Tavelli and Ilaria Mastrorosa; Supervision, Enrico Girardi, Valentina Mazzotta and Andrea Antinori; Writing – original draft, Giulia Del Duca; Writing – review & editing, Alessandro Tavelli, Ilaria Mastrorosa, Camilla Aguglia, Simone Lanini, Anna Clelia Brita, Roberta Gagliardini, Serena Vita, Alessandra Vergori, Jessica Paulicelli, Giorgia Natalini, Angela D'Urso, Pierluca Piselli, Paola Gallì, Vanessa Mondillo, Claudio Mastroianni, Enrica Tamburrini, Loredana Sarmati, Cristof Stingone, Miriam Lichtner, Emanuele Nicastri, Massimo Farinella, Filippo Leserri, Andrea Siddu, Francesco Maggi, Antonella D'Arminio Monforte, Francesco Vairo, Alessandra Barca, Francesco Vaia, Enrico Girardi, Valentina Mazzotta and Andrea Antinori.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Lazzaro Spallanzani” in Rome, Italy [project 5x1000 2021 advanced grant Dr. Andrea Antinori] and by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente Linea 2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol (MPOX-VAC Study, version 1.0, August 23, 2022), was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani” IRCCS in Rome, Italy (approval number:41-z 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent (version 1.0, August 23, 2022), was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data generated and/or analyzed within the present study are available in our institutional repository (rawdata.inmi.it), subject to registration. In the event of a malfunction of the application, the request can be sent directly by e-mail to the Library (biblioteca@inmi.it). No charge for granting access to data is required.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the study participants, doctors and nurses of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Lazzaro Spallanzani” in Rome, Italy and other centers that contributed toward the realization of the study (Icona Foundation, Milan; Umberto I Hospital, Rome; Clinic of Infectious Diseases, A. Gemelli Foundation, Rome; Clinic of Infectious Diseases Tor Vergata Hospital, Rome; STD/HIV San Gallicano Dermatologic Unit IFO, Rome; Infectious Diseases, La Sapienza University Santa Maria Goretti Hospital, Latina; Homosexual Culture Circle Mario Mieli, Rome; Plus Rome, Rome; Regional Directorate for Health and Social-Health Integration, Lazio Region).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests for the present study.

References

- WHO (World Health Organ.) (2023). Mpox (monkeypox). Geneva: World Health Organization; April 18th 2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox.

- WHO (World Health Organ.) (2022).Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/monkeypox-oubreak-2022.

- Thornhill, JP., et al. (2022). Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries - April-June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022 Aug 25;387(8):679-691. [CrossRef]

- Mitjà, O., Ogoina, D., Titanji, BK., Galvan, C., Muyembe, JJ., Marks, M., Orkin, CM. (2022). Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023 Jan 7;401(10370):60-74. [CrossRef]

- Allan-Blitz, LT., Gandhi, M., Adamson, P., Park, I., Bolan, G., Klausner, JD. (2023). A Position Statement on Mpox as a Sexually Transmitted Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Apr 17;76(8):1508-1512. [CrossRef]

- Antinori, A., et al. (2022).Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of four cases of monkeypox support transmission through sexual contact. Eurosurveillance journal, Volume 27, Issue 22. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. 05 August 2022 CIRCOLARE del Ministero della Salute n. 35365. Indicazioni ad interim sulla strategia vaccinale contro il vaiolo delle scimmie (MPX). https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/malattieInfettive/archivioNormativaMalattieInfettive.jsp (Accessed xxx xx, 2023).

- MacDonald, NE. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33:4161–64. [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organ.). (2019). Ten threats to global health in 2019. World Health Organization News, March 21. https://www.who.int/vietnam/news/feature-stories/detail/ten-threats-toglobal-health-in-2019.

- Dudley, MZ., Privor-Dumm, L., Dubé, È., MacDonald, NE. (2020). Words matter: vaccine hesitancy, vaccine demand, vaccine confidence, herd immunity and mandatory vaccination. Vaccine 38:709–11. [CrossRef]

- Millward, G. (2018). Stuart Blume,Immunization: How Vaccines Became Controversial. Soc. Hist.Med. 31:438. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J., Franco, O.H. (2021). Public trust, misinformation and COVID-19 vaccination willingness in Latin America and the Caribbean: Today’s key challenges. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 3, 100073. [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S., et al. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Emerging Variants: Evidence from Six Countries. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 148. [CrossRef]

- Lounis, M, Riad A. (2023). Monkeypox (MPOX)-Related Knowledge and Vaccination Hesitancy in Non-Endemic Countries: Concise Literature Review. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Jan 19;11(2):229. [CrossRef]

- Dukers-Muijrers, NHTM., et al. (2023). Mpox vaccination willingness, determinants, and communication needs in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, in the context of limited vaccine availability in the Netherlands (Dutch Mpox-survey). Front Public Health. 5;10:1058807. [CrossRef]

- Zucman, D., Fourn, E., Touche, P., Majerholc, C., Vallée, A. (2022). Monkeypox Vaccine Hesitancy in French Men Having Sex with Men with PrEP or Living with HIV in France. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Sep 28;10(10):1629. [CrossRef]

- Palich, R., Jedrzejewski, T., et al. (2023). High uptake of vaccination against mpox in men who have sex with men (MSM) on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Paris, France. Sex Transm Infect.sextrans-2023-055885. [CrossRef]

- Von Tokarski, F., et al. (2023). Smallpox vaccine acceptability among French men having sex with men living with HIV in settings of monkeypox outbreak. AIDS 37(5):p 855-856. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, M., et al. (2023). Uptake of Mpox vaccination among transgender people and gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men among sexually-transmitted infection clinic clients in Vancouver, British Columbia. Vaccine;41(15):2485-2494. [CrossRef]

- Vairo F., et al. (2023). The possible effect of sociobehavioral factors and public health actions on the mpox epidemic slowdown. International journal of infectious diseases, volume 130, P83-85. [CrossRef]

- Sintonen, H. (1981). An approach to measuring and valuing health states. Soc Sci Med Med Econ; 15(2): 55-65. [CrossRef]

- Apolone, G., & Mosconi, P. (1998). The italian sf-36 health survey: translation, validation and norming. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 51(11), 1025–1036. [CrossRef]

- McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E., Jr, & Raczek, A. E. (1993). The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical care, 31(3), 247–263. [CrossRef]

- Ware, J. E., Jr, & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care, 30(6), 473–483. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3765916.

- Lins, L., & Carvalho, F. M. (2016). SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE open medicine, 4, 2050312116671725. [CrossRef]

- Pierri, F., Perry, B.L., DeVerna, M.R., Yang, K.C., Flammini, A., Menczer, F., Bryden, J. (2022). Online misinformation is linked to early COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and refusal. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5966. [CrossRef]

- Ulloque-Badaracco, JR., Alarcón-Braga, EA., Hernandez-Bustamante, EA., Al-Kassab-Córdova, A., Benites-Zapata, VA., Bonilla-Aldana, DK., Rodriguez-Morales, AJ. (2022). Acceptance towards Monkeypox Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pathogens.;11(11):1248. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).