Submitted:

13 May 2024

Posted:

14 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

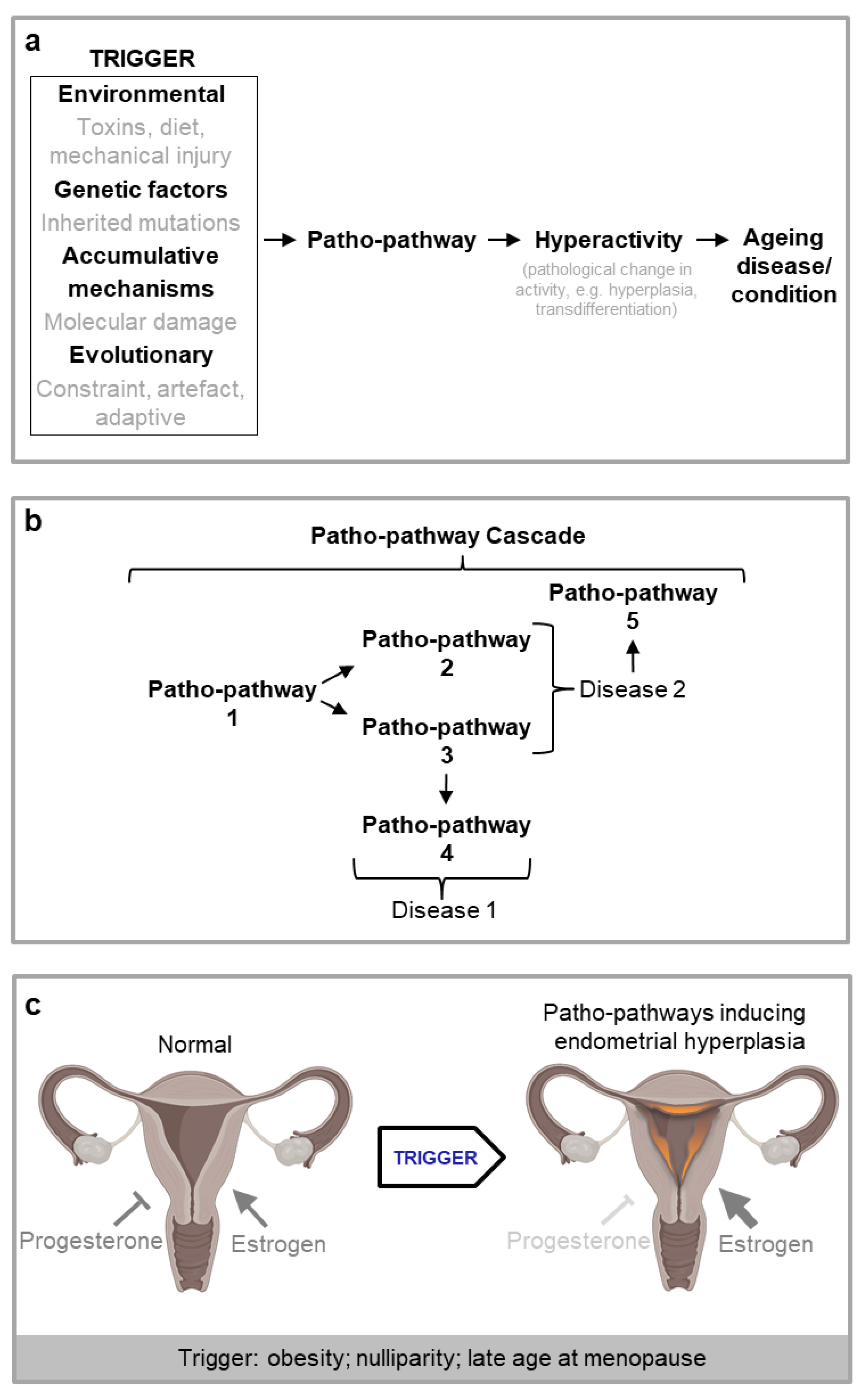

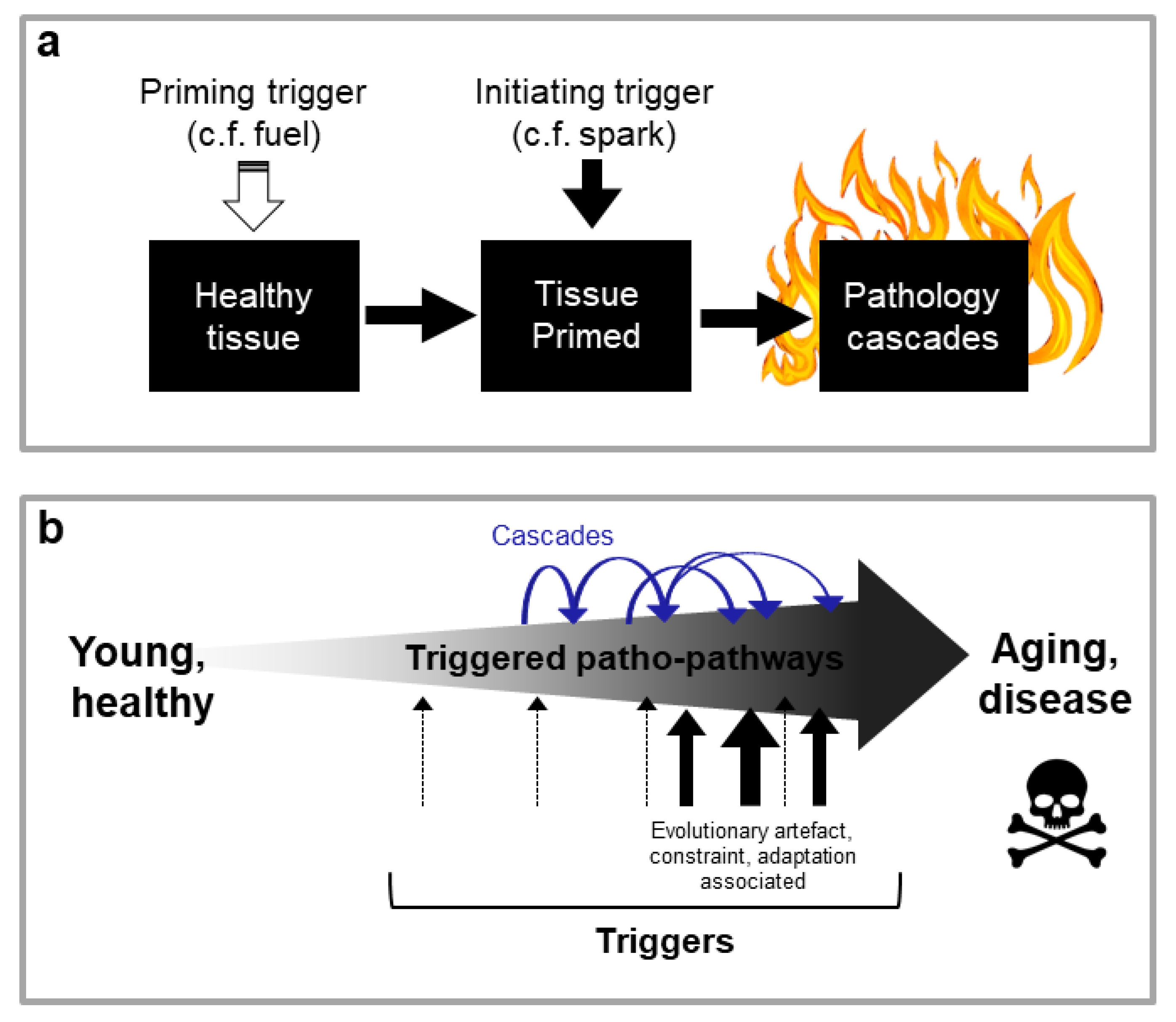

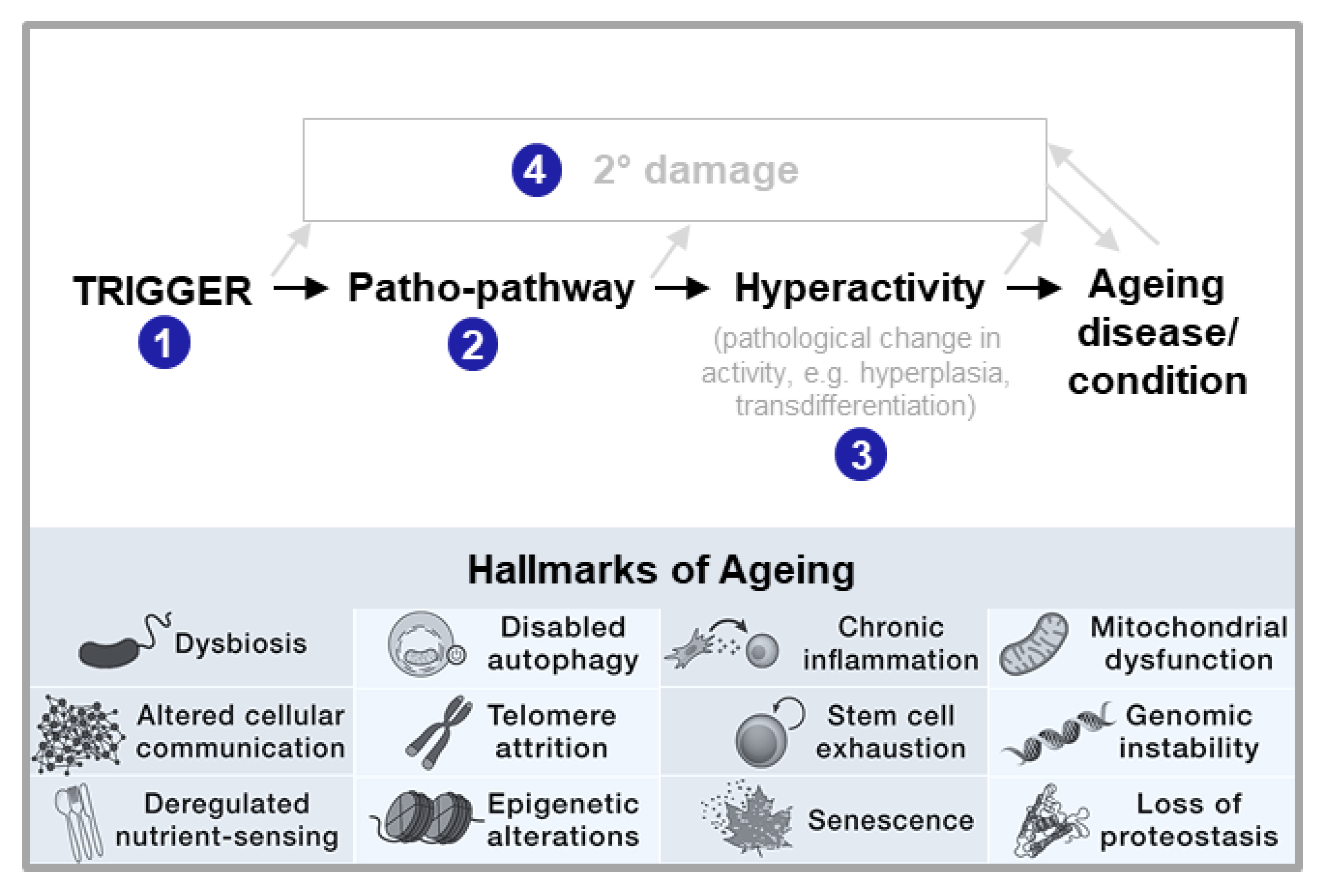

New Theory: Triggered Patho-Pathways

Patho-Pathways Induce Pathology through Cell, Tissue and System Hyperactivity

Disease Onset May Be Dependent on the Convergence of Multiple Patho-Pathway Triggers, Some of which Have Evolutionary Origins

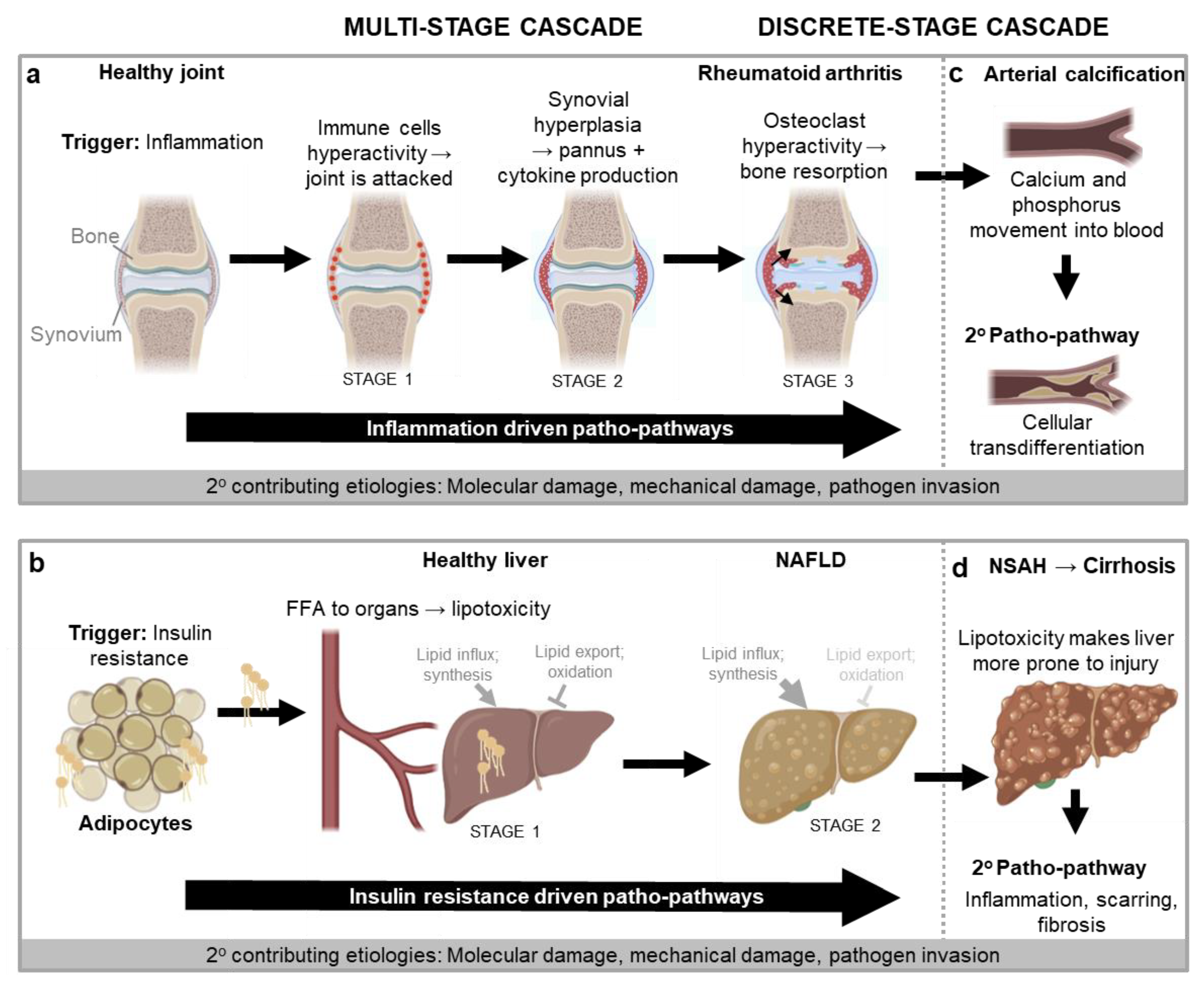

Links between Disparate Age-Related Diseases Can Be Explained through Patho-Pathway Cascades

Patho-Pathway Cascades as a Tool in Disease Prediction

Existing Theories of Ageing in the Context of Our New Theory: The Role of Nutrient Signalling in Ageing

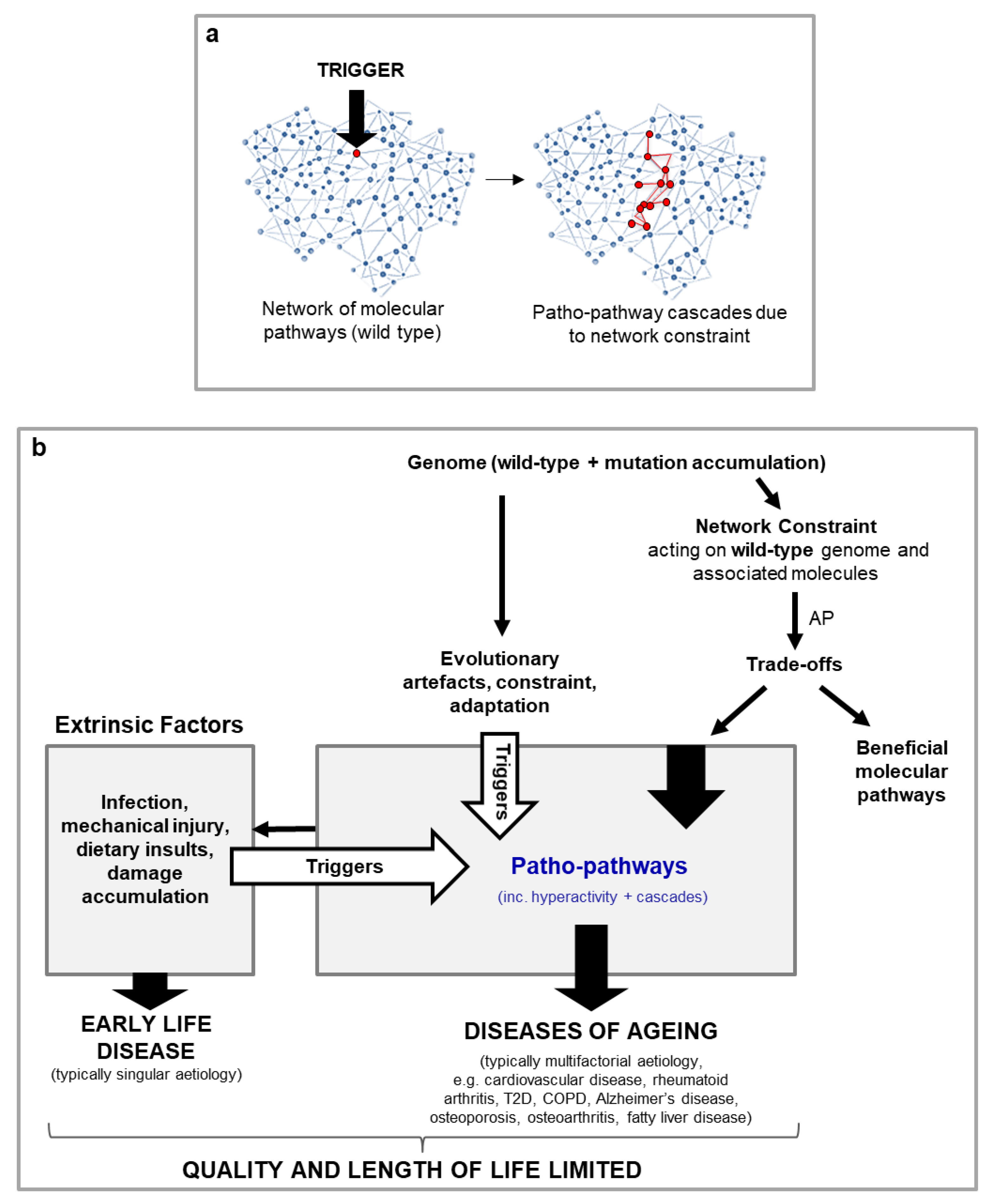

Evolutionary Theory in the Context of Our New Theory

Blueprint Maps of Triggered Patho-Pathways in Wider Aetiological Webs

| Case Study 1: A Blueprint Map of T2D and periodontitis |

| As an illustration of a triggered patho-pathway aetiological web, consider the relationship between type II diabetes (T2D) and periodontitis, where working backwards we find both can stem from menopause-related endocrine changes in women >50 yrs. T2D can suppress the immune system via several different discrete stage patho-pathway cascades. This suppression of the immune system by T2D goes on to risk infection such as periodontitis (severe gum infection that can destroy teeth and the bone that supports them). As an example, hyperglycaemia due to T2D leads to formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). And this in turn induces patho-pathways in macrophages, causing a shift of class frequency. Numbers of M1 macrophages that encourage inflammation are reduced, and numbers of M2 macrophages that favour tissue repair are increased (He et al., 2020). This leads to a reduction in microbicidal capacity (Berbudi et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2012; Pavlou et al., 2018) which, along with reduced blood flow, increases risk of infection and impairs wound healing. Reduction in blood flow results from several causes, including increased blood viscosity from the hyperglycaemia and change in arterial wall tension from AGEs and triggered patho-pathway inflammation that causes vascular endothelial cell dysfunction (Cinar et al., 2001; Hadi and Suwaidi, 2007). To illustrate how complex the picture is, infection risk from T2D-associated immune suppression in the mouth is further compounded by hyposalivation (possibly due to T2D associated impaired blood flow to the salivary glands) and an increase in salivary glucose levels (resulting from elevated plasma glucose) which promotes bacterial growth (Al-Maskari et al., 2011; Pérez-Ros et al., 2021). Hyposalivation contributes to infection risk as saliva contains antimicrobial proteins and peptides, and acts as a mechanical barrier preventing adhesion of microbes to the surface of the oral mucosa. Moreover, a lack of salvia production causes stagnation in flow; any stagnation in flow increases risk of infection via bacterial build-up from a lack of mechanical washing (Iwabuchi et al., 2012). Bacterial build-up both directly destroys tissue, and has indirect effects such as lodging in between the gum and enamel thereby reducing adherence of gum to the enamel (leading to gum recession). When tracing out the cascades, what becomes apparent is that risk of periodontitis must be especially high in post-menopausal women. This is because the menopause increases risk of T2D as well as can directly contribute to periodontitis. Regarding menopause and its relation to T2D, we find that endocrine changes during menopause initiate patho-pathways of insulin resistance that closely mimics the cascades of insulin resistance seen in more general inflammaging (Table 2, Figure 3b). Particularly oestrogen is known to play a role in regulating insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, and so decline in oestrogen causes elevated blood sugar levels that give rise to T2D (Ou et al., 2023). Specifically, oestrogen decline causes patho-pathways associated with a decline in pancreatic insulin production (Godsland, 2005), pulling glucose out of stores like muscle and the adipose tissue. Simultaneously, low oestrogen triggers patho-pathways of liver gluconeogenesis while decreasing glucose catabolism (Shen and Shi, 2015). Regarding the menopause directly contributing to periodontitis, we find oestrogen deficiency induces triggered patho-pathways of bone resorption contributing to loss of bone that supports teeth, and oestrogen decline affects gingiva (gum) integrity (Bhardwaj and Bhardwaj, 2012; Kovacs, 2016). The latter arises from yet another triggered patho-pathway change: oestrogen controls proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts in the gingiva, with low oestrogen favouring cell shedding (Bhardwaj and Bhardwaj, 2012). This complex example illustrates how diverging pathological outcomes from one condition in an aetiological web can reconverge to generate a further disease (here periodontitis). In other words, many diseases can converge to form one disease and one disease can proliferate to generate many more in a domino-style effect. |

Changing Clinical Practice and Scientific Approach: Triggered Patho-Pathway Cascades Are Amenable to Medical Intervention

Predictions of the New Theory

Conclusions

References

- Abedin, M., Tintut, Y. and Demer, L.L., 2004. Vascular calcification: mechanisms and clinical ramifications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 24, 1161-70.

- Acerenza, L., 2016. Constraints, Trade-offs and the Currency of Fitness. J Mol Evol. 82, 117-27. [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.A., Angulo, P. and Lindor, K.D., 2005. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Canad. Med. Assoc. J. 172, 899-905.

- Adinolfi, L.E., Rinaldi, L., Guerrera, B., Restivo, L., Marrone, A., Giordano, M. and Zampino, R., 2016. NAFLD and NASH in HCV Infection: Prevalence and Significance in Hepatic and Extrahepatic Manifestations. Int J Mol Sci. 17. [CrossRef]

- Admasu, T.D., Rae, M. and Stolzing, A., 2021. Dissecting primary and secondary senescence to enable new senotherapeutic strategies. Ageing Res Rev. 70, 101412. [CrossRef]

- Al-Maskari, A.Y., Al-Maskari, M.Y. and Al-Sudairy, S., 2011. Oral Manifestations and Complications of Diabetes Mellitus: A review. Sult. Qab. Uni. med. J. 11, 179-186.

- Baiceanu, A., Mesdom, P., Lagouge, M. and Foufelle, F., 2016. Endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis in hepatic steatosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 12, 710-722. [CrossRef]

- Berbudi, A., Rahmadika, N., Tjahjadi, A.I. and Ruslami, R., 2020. Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 16, 442-449. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A. and Bhardwaj, S.V., 2012. Effect of menopause on women's periodontium. J. Midliife Health. 3, 5-9. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V., 2006. Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle. 5, 2087-102. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V., 2012. Answering the ultimate question "what is the proximal cause of aging?". Aging (Albany NY). 4, 861-877.

- Borash, D.J., Rose, M.R. and Mueller, L.D., 2007. Mutation accumulation affects male virility in Drosophila selected for later reproduction. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 80, 461-472. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.J., Araujo-Vilar, D., Cheung, P.T., Dunger, D., Garg, A., Jack, M., Mungai, L., Oral, E.A., Patni, N., Rother, K.I., von Schnurbein, J., Sorkina, E., Stanley, T., Vigouroux, C., Wabitsch, M., Williams, R. and Yorifuji, T., 2016. The Diagnosis and Management of Lipodystrophy Syndromes: A Multi-Society Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 101, 4500-4511. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.A., Jordan, K.W., Lyman, R.F., Harbison, S.T., Leips, J., Morgan, T.J., DeLuca, M., Awadalla, P. and Mackay, T.F., 2006. Phenotypic variation and natural selection at Catsup, a pleiotropic quantitative trait gene in Drosophila. Current Biology. 16, 912-919. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. and Heitkemper, M.M., 2002. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 123, 1686-1701. [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, B., 2001. Patterns of age-specific means and genetic variances of mortality rates predicted by the mutation-accumulation theory of ageing. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 210, 47-65. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.X. and Moe, S.M., 2012. Vascular calcification: pathophysiology and risk factors. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 14, 228-237. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Yu, R., Xiong, Y., Du, F. and Zhu, S., 2017. A vicious circle between insulin resistance and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids in Health and Disease. 16, 203. [CrossRef]

- Cinar, Y., Senyol, A.M. and Duman, K., 2001. Blood viscosity and blood pressure: role of temperature and hyperglycemia. Am J Hypertens. 14, 433-8. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.S., Bynum, M.L. and Somers, E.C., 2009. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 33, 197-207. [CrossRef]

- Curtsinger, J.W. and Khazaeli, A.A., 2002. Lifespan, QTLs, age-specificity, and pleiotropy in Drosophila. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 123, 81-93.

- De Luca, M., Roshina, N.V., Geiger-Thornsberry, G.L., Lyman, R.F., Pasyukova, E.G. and Mackay, T.F., 2003. Dopa decarboxylase (Ddc) affects variation in Drosophila longevity. Nature genetics. 34, 429-433. [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, J.P., 2005. Open-minded scepticism: inferring the causal mechanisms of human ageing from genetic perturbations. Ageing Res. Rev. 4, 1–22.

- de Magalhães, J.P. and Church, G.M., 2005. Genomes optimize reproduction: aging as a consequence of the developmental program. Physiology. 20, 252–259.

- Demaria, M., Ohtani, N., Youssef, S., Rodier, F., Toussaint, W., Mitchell, J., Laberge, R., Vijg, J., Van Steeg, H., Dollé, M., Hoeijmakers, J., de Bruin, A., Hara, E. and Campisi, J., 2014. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell. 31, 722-733. [CrossRef]

- Demer, L.L., 2002. Vascular calcification and osteoporosis: inflammatory responses to oxidized lipids. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31, 737-741. [CrossRef]

- Distler, J.H.W., Wenger, R.H., Gassmann, M., Kurowska, M., Hirth, A., Gay, S. and Distler, O., 2004. Physiologic responses to hypoxia and implications for hypoxia-inducible factors in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 50, 10-23. [CrossRef]

- Dørum, A., Tonstad, S., Liavaag, A.H., Michelsen, T.M., Hildrum, B. and Dahl, A.A., 2008. Bilateral oophorectomy before 50 years of age is significantly associated with the metabolic syndrome and Framingham risk score: a controlled, population-based study (HUNT-2). Gynecol Oncol. 109, 377-83. [CrossRef]

- Epplein, M., Reed, S.D., Voigt, L.F., Newton, K.M., Holt, V.L. and Weiss, N.S., 2008. Risk of Complex and Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia in Relation to Anthropometric Measures and Reproductive History. Am. J Epidem. 168, 563-570. [CrossRef]

- Escobar, J.S., Jarne, P., Charmantier, A. and David, P., 2008. Outbreeding alleviates senescence in hermaphroditic snails as expected from the mutation-accumulation theory. Current Biology. 18, 906-910. [CrossRef]

- Everman, E.R. and Morgan, T.J., 2018. Antagonistic pleiotropy and mutation accumulation contribute to age-related decline in stress response. Evolution. 72, 303-317. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.P., Zhao, Y., Huang, J.Y., Yang, X., Liu, Y. and Zhang, X.L., 2024. The functional role of cellular senescence during vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15, 1330942. [CrossRef]

- Feil, S., Fehrenbacher, B., Lukowski, R., Essmann, F., Schulze-Osthoff, K., Schaller, M. and Feil, R., 2014. Transdifferentiation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells to Macrophage-Like Cells During Atherogenesis. Circulation Research. 115, 662-667. [CrossRef]

- Gems, D., 2021. Understanding hyperfunction: an emerging paradigm for the biology of aging. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gems, D., 2022. The hyperfunction theory: an emerging paradigm for the biology of aging. Ageing. Res. Rev. 74, 101557. [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.T., Szklo, M., Post, W., Petri, M., Blumenthal, R.S., Lam, G., Gelber, A.C., Detrano, R., Scott, W.W., Kronmal, R.A. and Bathon, J.M., 2009. Coronary arterial calcification in rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 11, R36. [CrossRef]

- Glyn-Jones, S., Palmer, A.J., Agricola, R., Price, A.J., Vincent, T.L., Weinans, H. and Carr, A.J., 2015. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 386, 376-387.

- Godsland, I.F., 2005. Oestrogens and insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 48, 2213-2220. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y., Thompson Jr, J.N. and Woodruff, R., 2006. Effect of deleterious mutations on life span in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 61, 1246-1252.

- Hadi, H.A.R. and Suwaidi, J.A., 2007. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 3, 853-876.

- Hamilton, W.D., 1966. The moulding of senescence by natural selection. J. Theor. Biol. 12, 12-45. [CrossRef]

- Hannemann, M.M., Alexander, H.M., Cope, N.J. and Acheson, N., 2007. Endometrial hyperplasia: a clinician's review. Obst. Gyn. & Reproduct. Med. 17, 169-172.

- He, S., Hu, Q., Xu, X., Niu, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, Y., Su, Q. and Qin, L., 2020. Advanced glycation end products enhance M1 macrophage polarization by activating the MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 525, 334-340. [CrossRef]

- Heppner, F.L., Ransohoff, R.M. and Becher, B., 2015. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 16, 358-372. [CrossRef]

- Hibler, E.A., Kauderer, J., Greene, M.H., Rodriguez, G.C. and Alberts, D.S., 2016. Bone loss after oophorectomy among high-risk women: an NRG oncology/gynecologic oncology group study. Menopause (New York, N.Y.). 23, 1228-1232. [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J.H., Klein, M., Garcia, P., Histing, T., Culemann, U., Pizanis, A., Laschke, M.W., Scheuer, C., Meier, C., Schorr, H., Pohlemann, T. and Menger, M.D., 2008. Rapamycin affects early fracture healing in mice. British journal of pharmacology. 154, 1055-1062. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.A., Alipaz, J.A., Drnevich, J.M. and Reynolds, R.M., 2002. A test of evolutionary theories of aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99, 14286-14291.

- Ising, C., Venegas, C., Zhang, S., Scheiblich, H., Schmidt, S.V., Vieira-Saecker, A., Schwartz, S., Albasset, S., McManus, R.M. and Tejera, D., 2019. NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives tau pathology. Nature. 575, 669-673. [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, H., Fujibayashi, T., Yamane, G., Imai, H. and Nakao, H., 2012. Relationship between Hyposalivation and Acute Respiratory Infection in Dental Outpatients. Gerontology. 58, 205-211. [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A., Bray, F., Center, M.M., Ferlay, J., Ward, E. and Forman, D., 2011. Global cancer statistics. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 61, 69-90.

- Karavassilis, M.E. and Faragher, R., 2013. A relationship exists between replicative senescence and cardiovascular health. Longev Healthspan. 2, 3. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S., Kay, J. and Gravallese, E.M., 2010. Bone damage in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanistic insights and approaches to prevention. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 36, 385-404. [CrossRef]

- Keller, L., Reid, J. and Arcese, P., 2008. Testing evolutionary models of senescence in a natural population: age and inbreeding effects on fitness components in song sparrows. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275, 597-604. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.K., 1999. An experimental method for evaluating the contribution of deleterious mutations to quantitative trait variation. Genetics Research. 73, 263-273. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.K., 2003. Deleterious mutations and the genetic variance of male fitness components in Mimulus guttatus. Genetics. 164, 1071-1085. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.K., 2008. Testing the rare-alleles model of quantitative variation by artificial selection. Genetica. 132, 187-198. [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.C. and Gems, D., 2022. Semelparous Death as one Element of Iteroparous Aging Gone Large. Front Genet. 13, 880343. [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.C., Srivastava, S., Ezcurra, M., Hsiung, K.C., Hui, N., Townsend, S., Maczik, D., Zhang, B., Tse, V., Konstantellos, V., Bähler, J. and Gems, D., 2023. C. elegans ageing is accelerated by a self-destructive reproductive programme. Nature Communications. 14, 4381. [CrossRef]

- Kern, C.C., Townsend, S., Salzmann, A., Rendell, N., Taylor, G., Comisel, R.M., Foukas, L., Bähler, J. and Gems, D., 2021. C. elegans feed yolk to their young in a form of primitive lactation. Nature Communications. 12, 5801. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-E., Paik, H.Y., Yoon, H., Lee, J.E., Kim, N. and Sung, M.-K., 2015. Sex-and gender-specific disparities in colorectal cancer risk. WJG. 21, 5167.

- Knobe, K. and Berntorp, E., 2011. Haemophilia and joint disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. J Comorb. 1, 51-59. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, C.S., 2016. Maternal mineral and bone metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Physiological reviews. [CrossRef]

- Leips, J., Gilligan, P. and Mackay, T.F., 2006. Quantitative trait loci with age-specific effects on fecundity in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 172, 1595-1605. [CrossRef]

- Lesser, K.J., Paiusi, I.C. and Leips, J., 2006. Naturally occurring genetic variation in the age-specific immune response of Drosophila melanogaster. Aging cell. 5, 293-295. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F., Zhang, H.J., Hu, Q.X., Liu, X.Y., Wang, Z.Q., Fan, J.Y., Zhan, M. and Chen, F.L., 2012. Altered polarization, morphology, and impaired innate immunity germane to resident peritoneal macrophages in mice with long-term type 2 diabetes. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012, 867023. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, R.S., Myles, M.H., Livingston, B.A., Criley, J.M. and Franklin, C.L., 2004. Sex influence on chronic intestinal inflammation in Helicobacter hepaticus-infected A/JCr mice. Comp Med. 54, 301-8.

- Long, E. and Zhang, J., 2019. Retesting the influences of mutation accumulation and antagonistic pleiotropy on human senescence and disease. Nat Ecol Evol. 3, 992-993. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C., Blasco, M.A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. and Kroemer, G., 2023. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S.J. and Long, A.D., 2007. Joint estimates of quantitative trait locus effect and frequency using synthetic recombinant populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 176, 1261-1281. [CrossRef]

- Maklakov, A.A. and Chapman, T., 2019. Evolution of ageing as a tangle of trade-offs: energy versus function. Proc Biol Sci. 286, 20191604. [CrossRef]

- Man, Y., Zhang, C., Cheng, C., Yan, L., Zong, M. and Niu, F. Hormone replacement therapy and periodontitis progression in postmenopausal women: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Periodontal Research. n/a. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G., 1978. Genetic syndromes in man with potential relevance to the pathobiology of aging. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 14, 5–39.

- McGee, J.S. and Huttenhower, C., 2021. Of Mice and Men and Women: Sexual Dimorphism of the Gut Microbiome. IJW Derma. [CrossRef]

- Medawar, P.B., 1952. An Unsolved Problem Of Biology, H.K. Lewis, London.

- Miller, R.A., Berger, S.B., Burke, D.T., Galecki, A., Garcia, G.G., Harper, J.M. and Sadighi Akha, A.A., 2005. T cells in aging mice: genetic, developmental, and biochemical analyses. Immunological reviews. 205, 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Nacusi, L.P. and Tindall, D.J., 2011. Targeting 5alpha-reductase for prostate cancer prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Urol. 8, 378-84. [CrossRef]

- NCI, 2023. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program http://seer.cancer.gov/.

- Nuzhdin, S.V., Pasyukova, E.G., Dilda, C.L., Zeng, Z.-B. and Mackay, T.F., 1997. Sex-specific quantitative trait loci affecting longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the national academy of Sciences. 94, 9734-9739. [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.J., Lee, J.I., Huang, S.P., Chen, S.C., Geng, J.H. and Su, C.H., 2023. Association between Menopause, Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Metabolic Syndrome. J Clin Med. 12. [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, S., Lindsay, J., Ingram, R., Xu, H. and Chen, M., 2018. Sustained high glucose exposure sensitizes macrophage responses to cytokine stimuli but reduces their phagocytic activity. BMC Immunol. 19, 24. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ros, P., Navarro-Flores, E., Julián-Rochina, I., Martínez-Arnau, F.M. and Cauli, O., 2021. Changes in Salivary Amylase and Glucose in Diabetes: A Scoping Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 11. [CrossRef]

- Pollreisz, A. and Schmidt-Erfurth, U., 2010. Diabetic cataract-pathogenesis, epidemiology and treatment. J Ophthalmol. 2010, 608751.

- Pollycove, R., Naftolin, F. and Simon, J.A., 2011. The evolutionary origin and significance of menopause. Menopause. 18. [CrossRef]

- Prata, L.G.P.L., Ovsyannikova, I.G., Tchkonia, T. and Kirkland, J.L., 2018. Senescent cell clearance by the immune system: Emerging therapeutic opportunities. Seminars in immunology. 40, 101275-101275. [CrossRef]

- Regan, J., Khericha, M., Dobson, A., Bolukbasi, E., Rattanavirotkul, N. and Partridge, L., 2016. Sex difference in pathology of the ageing gut mediates the greater response of female lifespan to dietary restriction. Elife. 5, e10956.

- Reynolds, R.M., Temiyasathit, S., Reedy, M.M., Ruedi, E.A., Drnevich, J.M., Leips, J. and Hughes, K.A., 2007. Age specificity of inbreeding load in Drosophila melanogaster and implications for the evolution of late-life mortality plateaus. Genetics. 177, 587-595.

- Rong, J.X., Shapiro, M., Trogan, E. and Fisher, E.A., 2003. Transdifferentiation of mouse aortic smooth muscle cells to a macrophage-like state after cholesterol loading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100, 13531-6. [CrossRef]

- Sala Frigerio, C., Wolfs, L., Fattorelli, N., Thrupp, N., Voytyuk, I., Schmidt, I., Mancuso, R., Chen, W., Woodbury, M. and Srivastava, G., 2019. The major risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: age, sex, and genes modulate the microglia response to Aβ plaques. Cell Rep 27: 1293–1306. e6.

- Sapey, E., Greenwood, H., Walton, G., Mann, E., Love, A., Aaronson, N., Insall, R.H., Stockley, R.A. and Lord, J.M., 2014. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition restores neutrophil accuracy in the elderly: toward targeted treatments for immunosenescence. Blood. 123, 239-48. [CrossRef]

- Sears, B. and Perry, M., 2015. The role of fatty acids in insulin resistance. Lipids Health Dis. 14, 121-121. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. and Shi, H., 2015. Sex Hormones and Their Receptors Regulate Liver Energy Homeostasis. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2015, 294278. [CrossRef]

- Stearns, S., Partridge, L., Masoro, E. and Austad, S., 2001. Handbook of the Biology of Aging.

- Strenk, S.A., Strenk, L.M. and Koretz, J.F., 2005. The mechanism of presbyopia. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 24, 379-393. [CrossRef]

- Swindell, W.R. and Bouzat, J.L., 2006. Inbreeding depression and male survivorship in Drosophila: implications for senescence theory. Genetics. 172, 317-327. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y. and Zhou, R.Y., 2020. Review of the Roles and Interaction of Androgen and Inflammation in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 7958316. [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.H., 2003. Minireview: weapons of lean body mass destruction: the role of ectopic lipids in the metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 144, 5159-65. [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, G., Madersbacher, S. and Berger, P., 2005. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: age-related tissue-remodeling. Exp Gerontol. 40, 121-128. [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, J.M., 2014. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 509, 439-446.

- Virchow, R., 1863. Cellular Pathology, as Based upon Physiological and Pathological Histology, Dover Publications, Inc, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Voynow, J.A. and Shinbashi, M., 2021. Neutrophil Elastase and Chronic Lung Disease. Biomolecules. 11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Liu, Y. and Zhou, J., 2015. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl Neurodegener. 4, 19. [CrossRef]

- Waters, D.J., Shen, S. and Glickman, L.T., 2000. Life expectancy, antagonistic pleiotropy, and the testis of dogs and men. The Prostate. 43, 272-277. [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.K., Snook, J.P., Williams, M.A. and Weis, J.J., 2018. Bystander T Cells: A Balancing Act of Friends and Foes. Trends Immunol. 39, 1021-1035. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C., 1957. Pleiotropy, natural selection and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 11, 398-411.

- Xie, J., Van Hoecke, L. and Vandenbroucke, R.E., 2021. The Impact of Systemic Inflammation on Alzheimer's Disease Pathology. Front Immunol. 12, 796867.

| Antagonistic pleiotropy (AP) | Where action of a given gene is both beneficial and detrimental to fitness. If the latter occurs later in life and is therefore subject to weaker selection, such a gene may be favoured by natural selection, and promote ageing (Williams, 1957). |

| Biological constraint | A property of organisms and/or their ecology that prevents the evolution of traits that would increase fitness. |

| Discrete stage patho-pathway cascade (New term) | A series of patho-pathways triggered in a causal chain by different, but linked, triggers (c.f. multi-stage patho-pathway cascade). |

|

Hyperactivity (New term) |

Where an excess of normal cell, tissue or system activity leads to age-related pathology. This includes, not only an increase in normal function, such that it is above optimal for health, but also cells and tissues taking on new, unwanted and pathological activities. |

| Multi-stage patho-pathway cascade (New term) | Where a single underlying trigger drives multiple patho-pathways in succession, such that multiple stages can be distinguished (c.f. discrete stage patho-pathway cascade). |

| Network constraint (new term) | Where a given molecule acts in diverse contexts (cell and tissue types, genotypes, phenotypes, and environmental conditions) across signalling networks within an organism, such that optimisation of function in all contexts is not possible. (This is a type of biological constraint, c.f. biological constraint). |

| Patho-pathway cascade (New term) | A causal chain of patho-pathways, in which each triggers the next in the chain (c.f. multi-stage patho-pathway cascade and discrete patho-pathway cascade). |

| Wild-type | Genes maintained in the population, i.e. non atypical mutant. |

| Multi-Stage Patho-Pathway Cascade Example | Discrete Stage Patho-Pathway Cascade Example |

|

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Key trigger: insulin resistance The progression of NAFLD entails the sequential action of insulin resistance-triggered patho-pathways (Figure 3b). A major initiator of these is inflammation in adipose tissue, typically a consequence of obesity and/or inflammaging. [Obesity, with fat accumulation causes adipocytes reach their limit of expansion. This induces hypoxia which triggers proinflammatory patho-pathways (Sears and Perry, 2015) that mimic effects of inflammaging]. Steps are as follows: (i) Inflammation triggers patho-pathways of adipocyte insulin resistance. This causes increased export of free fatty acids (FFA) from the adipocytes and into the circulation (stage 1). (ii) FFA are then taken up by other organs that are not adapted to store large amounts of fat, such as the liver. This in turn leads to lipotoxicity (lipid-induced dysfunction) in those organs, which triggers localised patho-pathways of insulin resistance at those sites (stage 2) (Adams et al., 2005; Sears and Perry, 2015; Unger, 2003). It is here that the systemic consequences of insulin resistance really start to take effect, as hepatic insulin resistance and lipid accumulation trigger a patho-pathway positive feedback loop, driving the development of the metabolic syndrome (Figure 3b). To compound these changes, insulin resistance impairs control of blood glucose levels, further triggering type II diabetes (T2D) (Adams et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2017; Unger, 2003). Specifically, in the liver insulin resistance associated patho-pathways causes excess glucose secretion into the blood, and insulin resistance patho-pathways in muscle reduces glucose uptake, which together pathologically increase blood glucose levels, to induce T2D. In conclusion, Although NAFLD involves different organs (particularly adipose tissue and liver), the tight causal relationship between patho-pathway changes define a multi-stage patho-pathway cascade. |

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Key trigger: Lipotoxicity associatedinjury Returning to NAFLD (Figure 3b), lipotoxicity increases the susceptibility of the liver to injury (i.e. primes the liver c.f. Figure 2a). As a discrete stage cascade, upon injury, severe inflammation and fibrosis patho-pathways are triggered as an exaggerated wound healing response. (Specifically, proinflammatory cytokines induce patho-pathways of hyperactivity in innate immune cells which directly damage tissue. Concomitantly these cytokines trigger patho-pathways of hyperactivity in fibroblasts which causes the fibroblasts to secrete too much extracellular matrix including collagen - the resulting fibrosis contributes to liver failure via disruption of the liver architecture and function) (Figure 3d). Overall, this can result in disease progression to NASH, an aggressive form of fatty liver disease marked by liver inflammation, and advanced scarring and fibrosis (i.e. cirrhosis) (Adams et al., 2005). |

|

Neurodegeneration Key trigger: inflammation General systemic inflammation, from causes such as those that give rise to NAFLD (Figure 3b), can then go on to further trigger neurodegeneration via patho-pathways associated with microglia hyperactivity. As a specific example, increasing evidence indicates that systemic inflammation might drive the initiation and progression of Alzheimer's disease as immune cues can pass into the brain through various routes (e.g. via the circumventricular organs, across the brain barriers, through activating vascular cells at the brain barriers and even neural routes like cytokines from the thoracic-abdominal cavity (e.g. Kupffer cells in the liver) directly activating the vagal nerve which signals to the brain (Xie et al., 2021)). Neuroinflammation in turn contributes to Alzheimer's disease (Heppner et al., 2015; Sala Frigerio et al., 2019) via microglia hyperactivation as it exacerbates amyloid beta and tau pathologies that in turn cause cognitive decline (Ising et al., 2019). Likewise Parkinson’s disease is associated with neuroinflammation that systemic inflammation contributes to (Wang et al., 2015). | |

|

Diabetic cataracts Key trigger: excessive glucose Insulin resistance leading to T2D (Unger, 2003), can in turn cause diabetic cataracts as a part of a discrete stage patho-pathway cascade. Diabetic cataracts develop due to patho-pathways associated with excessive conversion of glucose into sorbitol, i.e. at a rate higher than sorbitol can be converted into fructose by the enzyme sorbitol dehydrogenase. The resulting build-up of sorbitol then generates increased osmotic stress in the lens fibres, causing them to swell and rupture (Pollreisz and Schmidt-Erfurth, 2010). | |

|

Cellular Senescence accumulation Key trigger: inflammation Another example of a discrete-stage patho-pathway cascade involves immunosenescence and accumulation of cells that have undergone cellular senescence (cell cycle arrest, and entry into a hypertrophic, hypersecretory state) (Prata et al., 2018) due to insulin resistance. Throughout life, fibroblasts undergo these type of differentiative changes to support wound healing (Demaria et al., 2014). Such “senescent” fibroblasts are subsequently cleared by the immune system, triggered by signals within the fibroblast senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Any factor that compromises efficiency of immune clearance of senescent fibroblasts, such as the insulin resistance that contributes to and aggravates systemic inflammation (see Figure 3b), results in path-pathway variants of this - and the accumulation of senescent fibroblasts that go on to disrupt cellular microenvironments which, in mice at least, promotes diverse diseases of ageing (van Deursen, 2014). Secondary cellular senescence Key trigger: autocrine and paracrine signals In an additional discrete stage cascade, accumulating senescent cells can trigger patho-pathways in neighbouring cells that cause them to also undergo senescence (secondary senescence via autocrine and paracrine signals) (Admasu et al., 2021). |

| Predictions of the New Theory | |

| Prediction | Supporting or Falsifying Evidence |

| Nutrient signalling pathway hyperactivity in-vivo will occur in mid to late life, rather than increasing gradually throughout life | To be tested |

| Nutrient signalling pathway hyperactivity will typically originate cell non-autonomously, rather than cell autonomously | To be tested |

|

Ageing and age-related disease is not restricted to old ages – ageing can be “triggered” in the young If age-related disease can indeed be “triggered”, age-related disease alongside their associated patho-pathway cascades, should be observable in the young |

Supporting evidence:

|

|

Observation of age-related increases in genetic variance for fitness components and in inbreeding load Genetic variance. Genetic variance is the difference in DNA sequences between individuals within a population. The more genes involved in generating ageing and related disease, the greater the likelihood of genetic variance being observed for fitness components. Previous proximate mechanism models of AP assume ageing stems from a subset of AP genes. In contrast, triggered patho-pathways and associated cascades do not assume that a small number of AP genes control fitness changes at both early and late stages of life. Cascades arising in later life entail the futile, unregulated triggering of whole hosts of genes and activation of molecules in later life (and any and every gene has the potential to be a pathology inducing AP gene). Inbreeding load. If only a subset of AP genes are driving ageing, an age-related increases in inbreeding load (the negative consequences of recessive allele build-up) is not expected. In our new theory, however, recessive alleles can act as any other extrinsic or extrinsic factor that triggers patho-pathways due to network constraint. This means that an age related increase in inbreeding load is expected. Additionally, we should be able to find specific medical examples of mutated alleles inducing disease via triggering patho-pathways. |

Supporting evidence: Observations of age-related change in genetic variance for fitness components and in inbreeding load has mostly been done in invertebrates such as Drosophila. The results show that genetic variation and inbreeding effects increase dramatically with age (Borash et al., 2007; Charlesworth, 2001; Escobar et al., 2008; Everman and Morgan, 2018; Gong et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2002; Keller et al., 2008; Lesser et al., 2006; Reynolds et al., 2007; Swindell and Bouzat, 2006), in support of our new theory. And there are specific medical examples of mutated alleles inducing disease via triggering patho-pathways. As one such example, the frequency of the mutated allele in haemophilia and so the incidence of the disorder, was greater among the royal families of Europe due to the high levels of royal inbreeding. Haemophilia causes recurring joint bleeding that triggers haemophilic arthropathy due to consequential joint inflammation. This joint inflammation initiates patho-pathways of synovial hypertrophy and other associated cascades as in Figure 3a, with haemophilic arthropathy closely resembling the pathological mechanisms seen in rheumatoid arthritis (Knobe and Berntorp, 2011). |

|

Common versus rare alleles as drivers of ageing Previous proximate mechanism models of AP assume ageing stems from a subset of AP genes. If true, genetic variation in ageing should be mainly due to alleles that segregate at intermediate frequencies. This contrasts our new theory. Not just common alleles, but also rare alleles could be triggered late on as part of patho-pathway cascades and so contribute to ageing. Expression of rare alleles may also act as patho-pathway triggers directly or indirectly via their knock-on effects. If true, there should be medical examples of this. |

Testing the prediction that genetic variation in ageing should be mainly due to alleles that segregate at intermediate frequencies has proved to be challenging, so there is no consensus (Carbone et al., 2006; De Luca et al., 2003; Kelly, 1999; Kelly, 2003; Kelly, 2008; Macdonald and Long, 2007). But in terms of medical examples of rare alleles accelerating age-related disease, there are examples as in the case of Haemophilia above. |

|

Do similar or different genomic regions control variance at early and late ages? Previous proximate mechanism models of AP assume that similar genomic regions will control variance in the phenotype at early and late ages, due to a small number of AP genes. In contrast, late life action of triggered patho-pathways and cascades would mean that different genomic regions would, in fact, be predicted to contribute to variation at early and late ages. Presence of triggered patho-pathways means genes exerting effects at only very specific times during youth for fitness benefits may be more frequently activated in a futile manner late in life. For example, genes and molecules associated with an immune response will only be triggered when an infection is sensed in youth, but may be constantly expressed later in life as part of an autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis. |

Supporting evidence: Results of quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping studies in Drosophila and mice were consistent with our new theory (Curtsinger and Khazaeli, 2002; Leips et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2005; Nuzhdin et al., 1997). There is also more recent work that is looking at using human genome wide association studies (GWAS) to test these predictions, with particular focus on long-term longitudinal studies, but sufficiently large data sets are required to attain reliable results here (Long and Zhang, 2019), which we currently lack. |

|

If network constraint is the reason behind why evolution is unable to uncouple trade-offs (i.e. separate cost from benefit) associated with patho-pathways, we should see evolutionary conservation of network constraint (i.e. all similar species should be subject to network constraint). While this is difficult to test for directly, we should see indirect evidence in the form of conservation of triggered patho-pathways and cascades across species |

Supporting evidence: This prediction is consistent with the presence of similar diseases of ageing in many mammalian species. As a specific example, canine rheumatoid arthritis shows patho-pathway cascades and stages that are very similar to those seen in human rheumatoid arthritis (Figure 3a) (Bennett, 1987; Innes & Clegg, 2010). |

|

If patho-pathways stem from network constraint, a prediction that follows is more broadly we should see a pattern where elements of biology associated with greater plasticity of function are expected to be at greater risk of inducing pathology (because they are subject to greater levels of network constraint). This prediction should hold true at all levels, from the molecular level up to cells and whole tissues and organs An easy means to test this is at the tissue and organ level – are tissue types and organs that show greater plasticity of strategy (such as those associated with active tissue remodelling during adulthood, e.g. to respond to infection, or for reproduction) more likely to be associated with disease? |

Supporting evidence:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).