Submitted:

19 October 2023

Posted:

23 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlight

- Catalyst deactivation evolution was studied from fresh, regenerated to spent using different spectroscopy methods (BET, XRF, XRD, and UV-RAMAN).

- The catalyst residence time has an influence on the Catalysts’ physicochemical properties changing

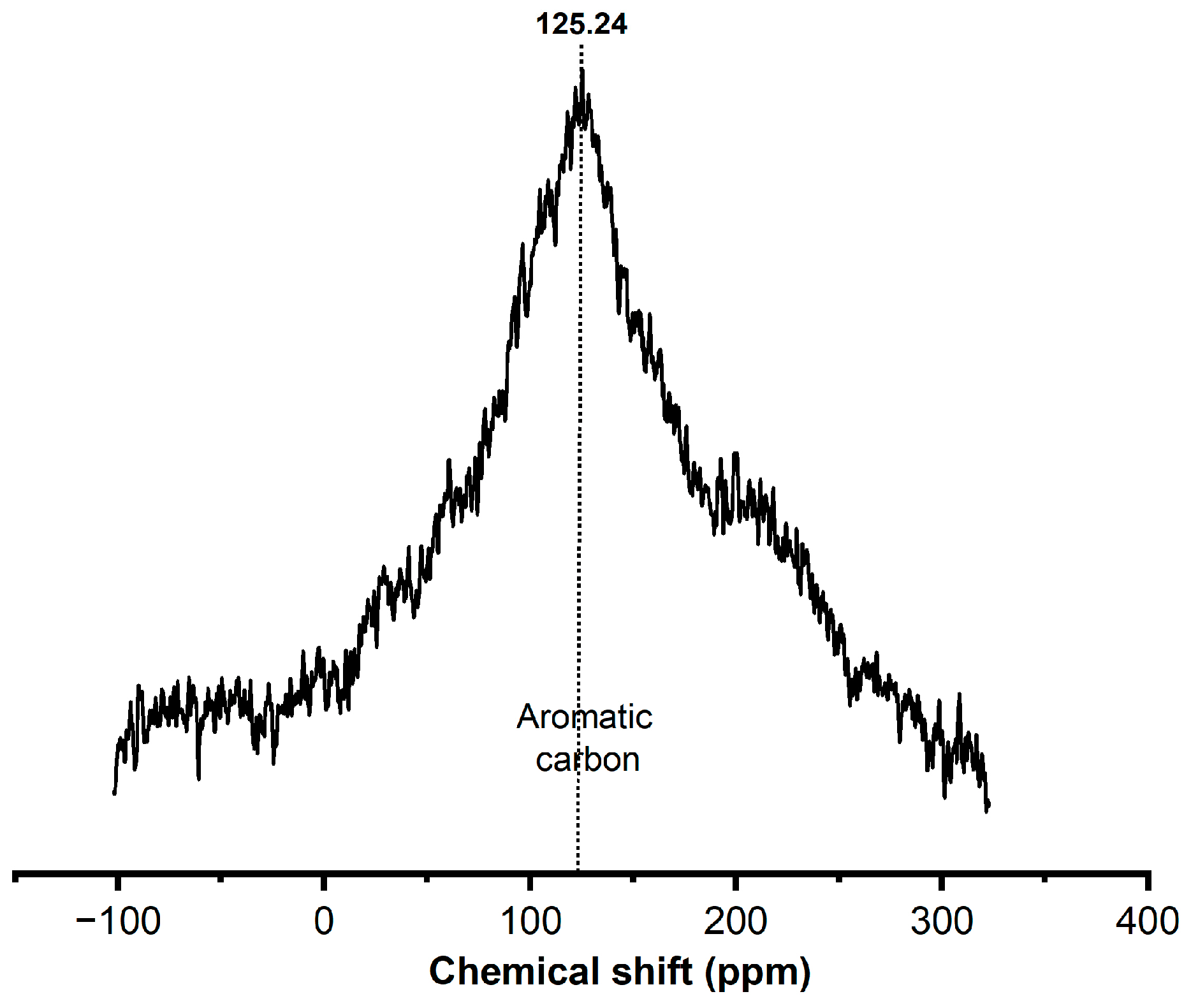

- NMR13C study shows that the polyaromatic hydrocarbon is the main component in the deposited coke of the spent catalyst

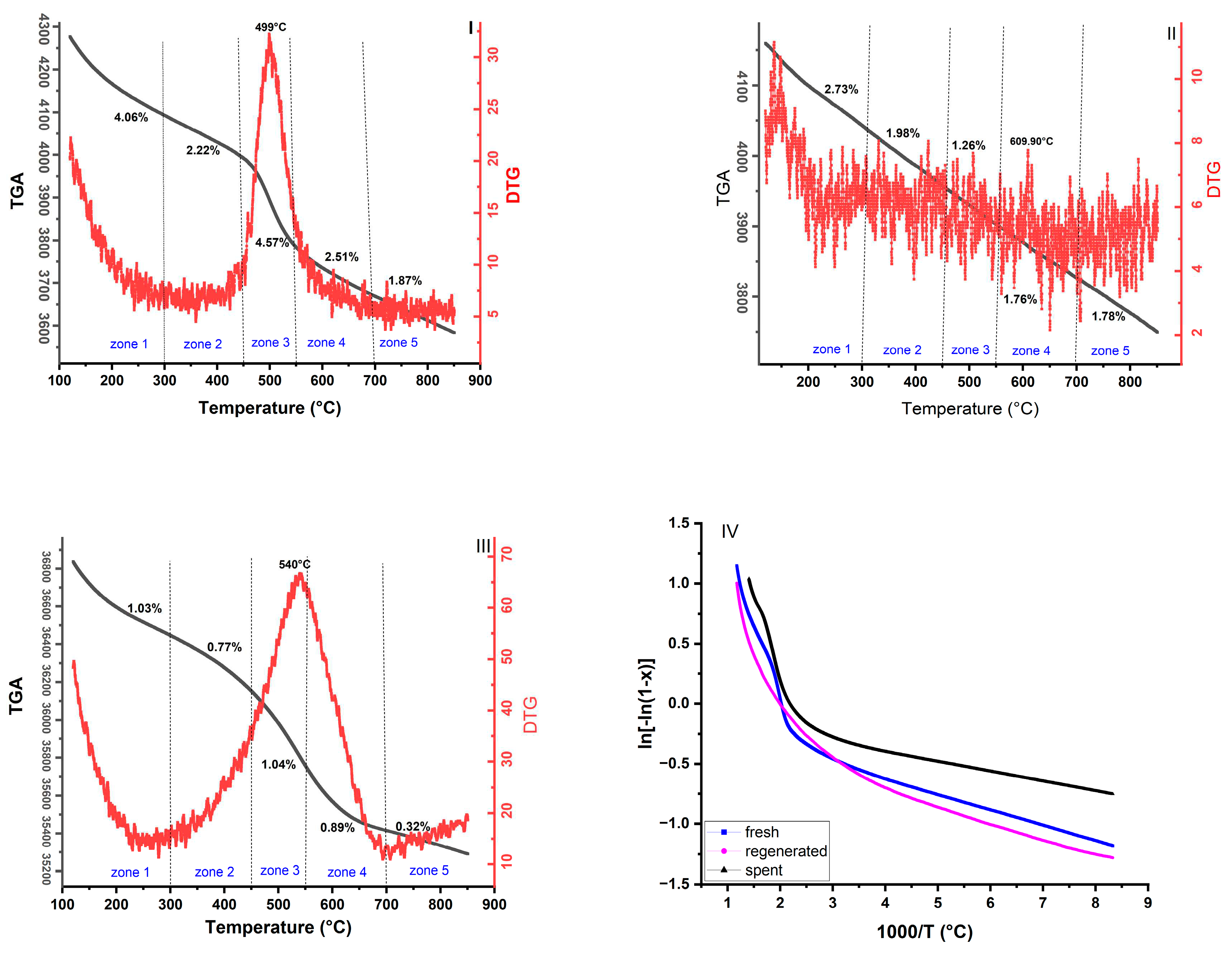

- Thermogravimetric analysis result indicated that the catalyst mass loss order is fresh>regenerated>spent catalyst due to the progressive hydroxyl losses during the thermal treatment

- Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters revealed that all zones are non-spontaneous endothermic reactions.

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sampling of catalyst

2.2. Cracking Reaction and regeneration conditions

2.3. Catalyst characterization

3. Results and discussion

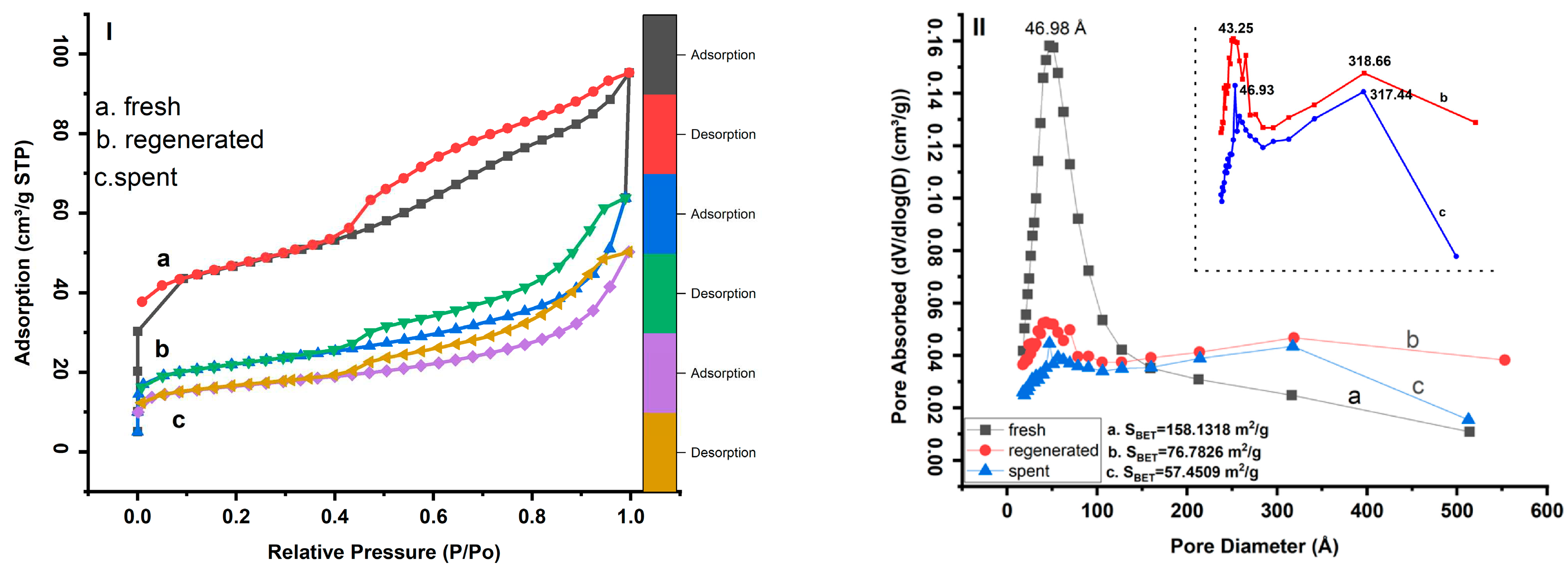

3.1. N2 isotherm and pore size distribution analysis

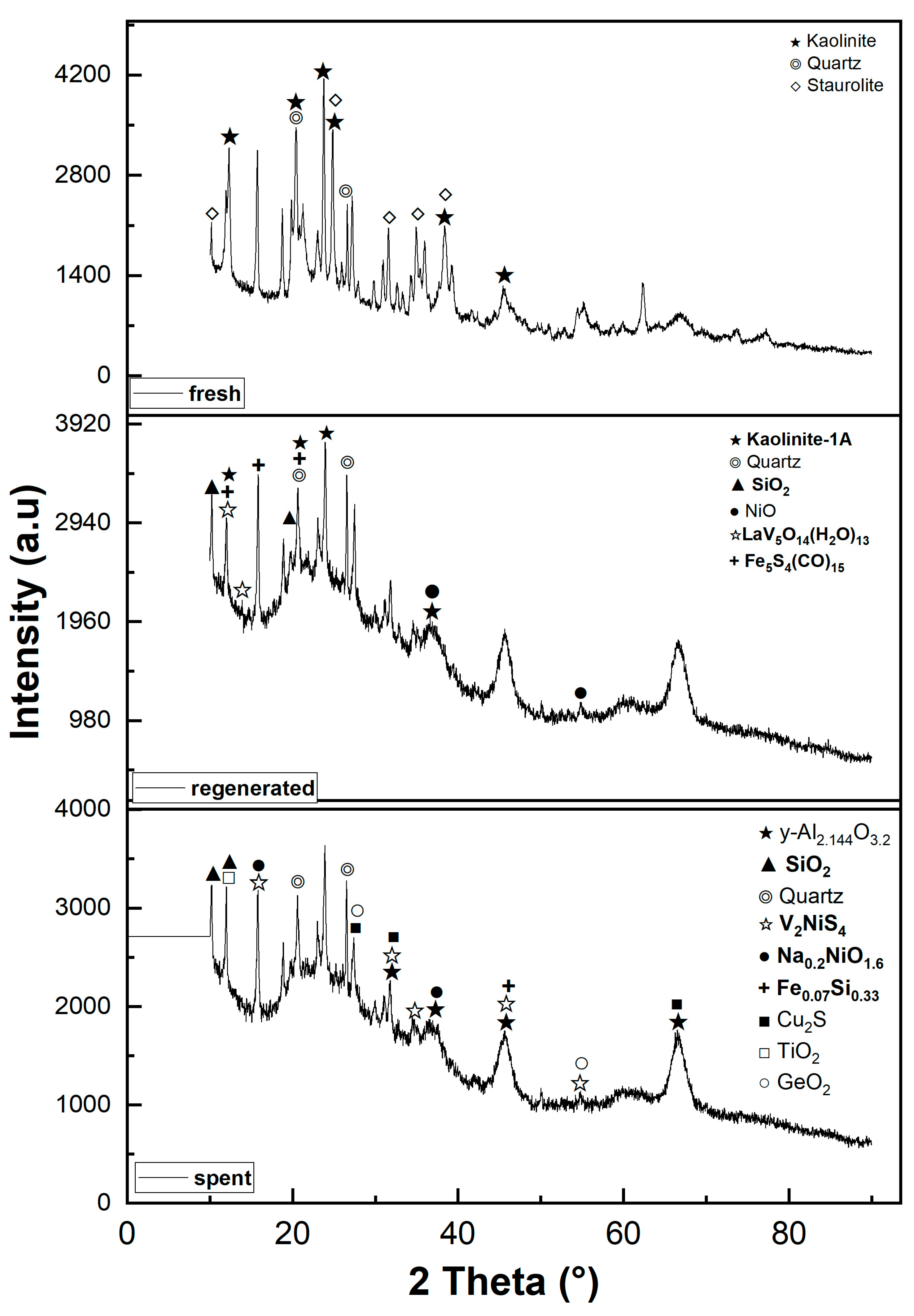

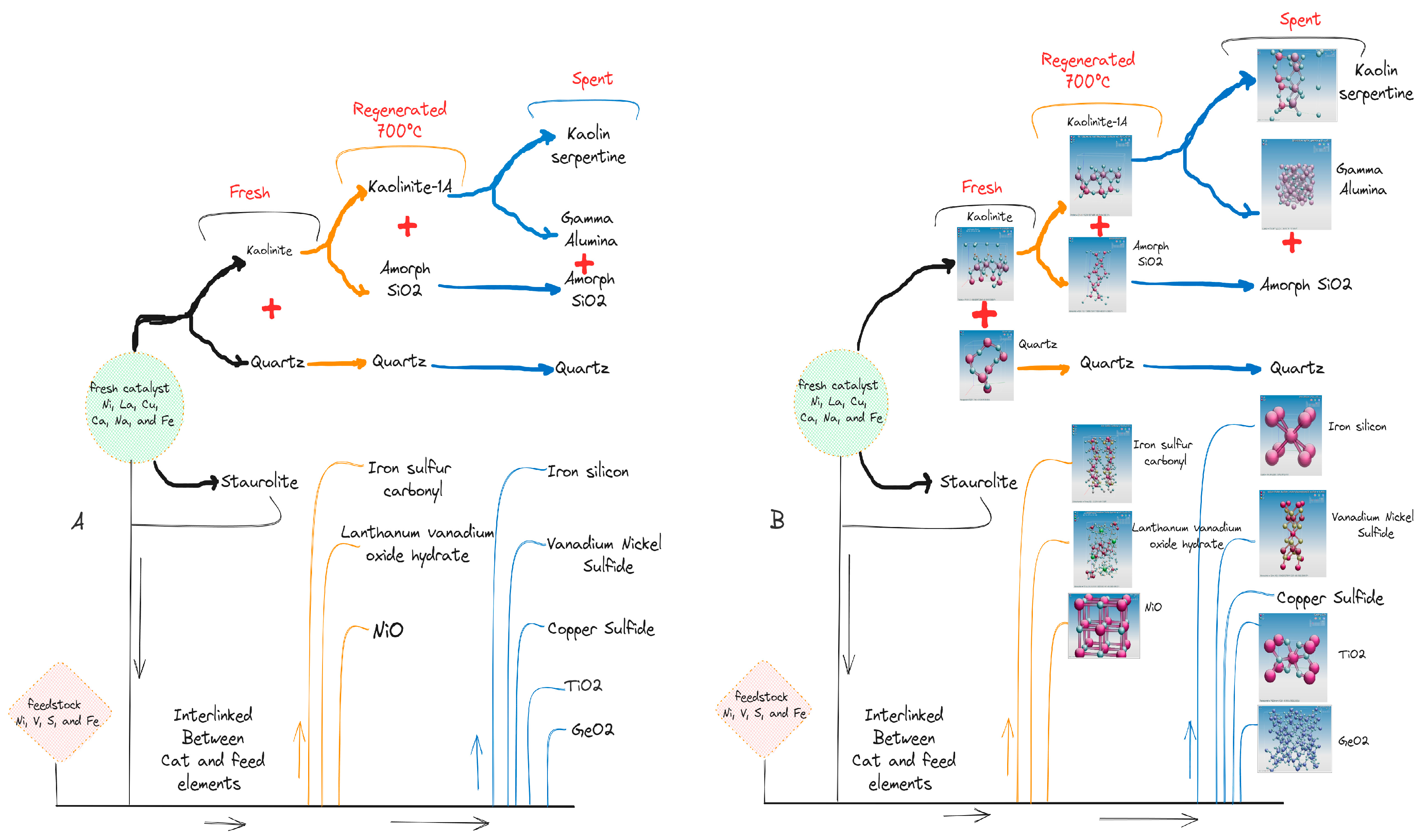

3.2. Crystallography analysis

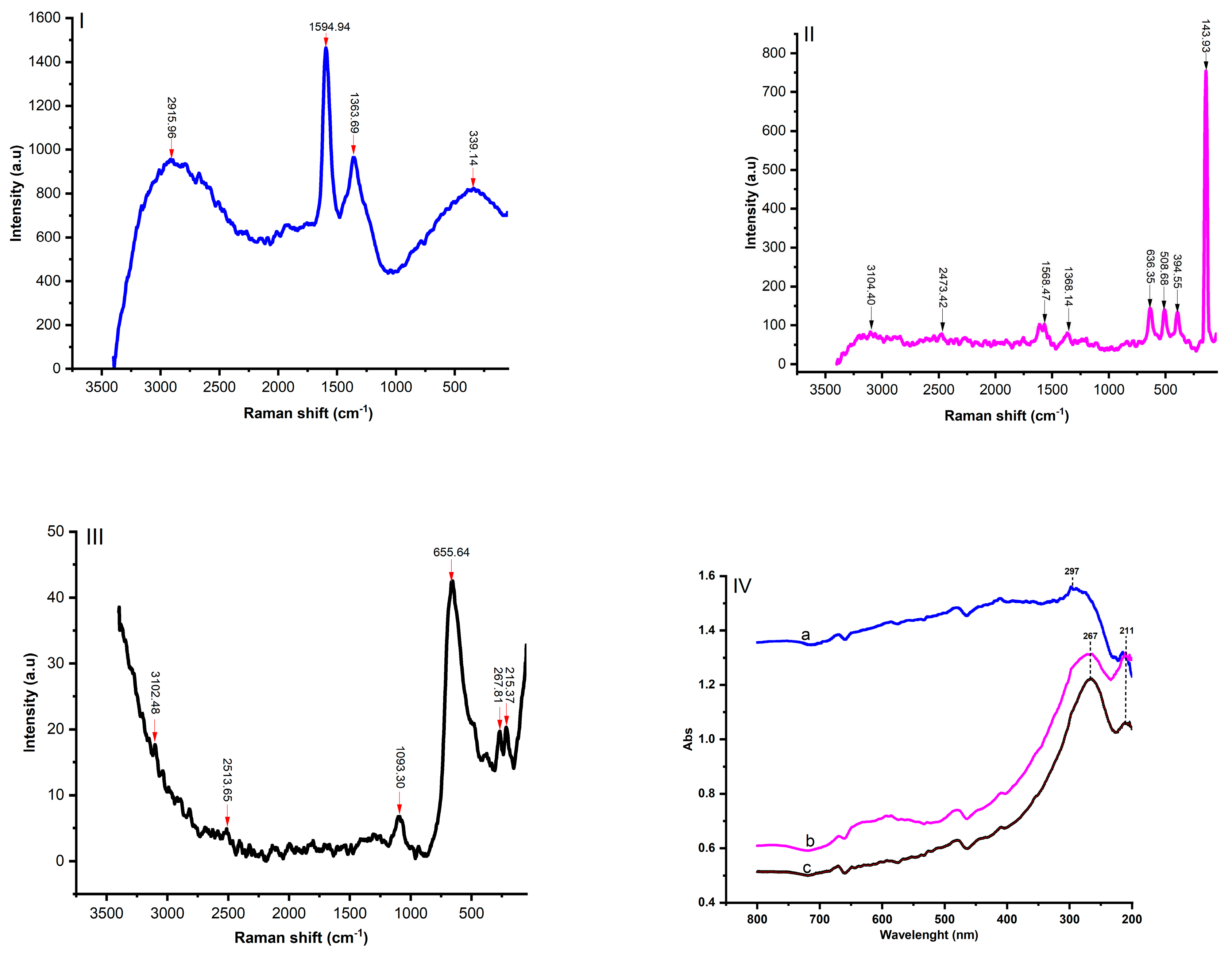

3.3. UV-visible near-infrared spectra and Raman spectra analysis

3.4. Solid-state LECO carbon analyzer and NMR 13C studies

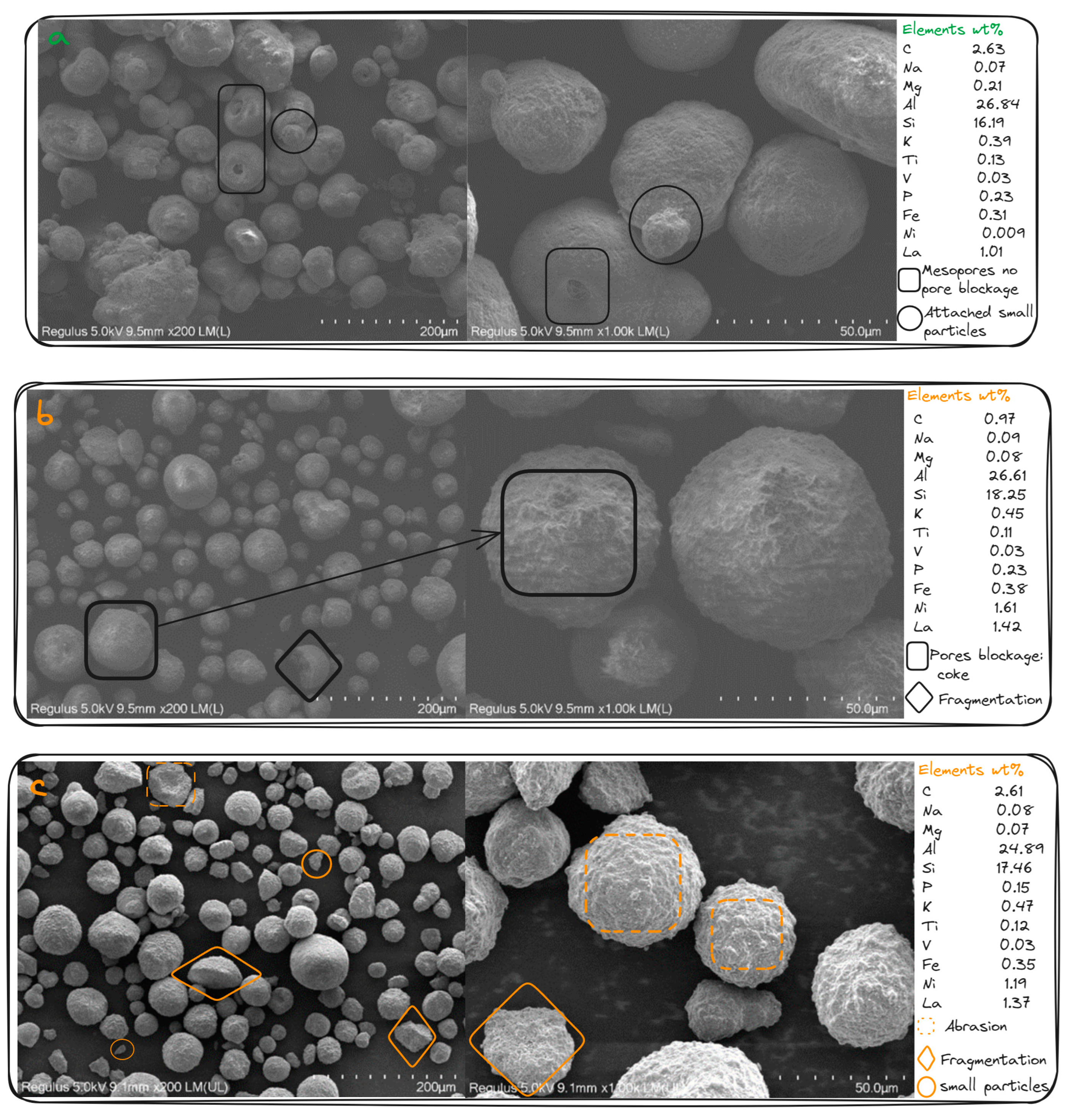

3.5. Catalyst morphology changes during the FCC Process.

3.6. Thermal Analysis

3.7. Kinetics and Thermodynamics Parameters calculation using TGA

Conclusion

References

- Y.S. Zhang, X. Lu, R.E. Owen, G. Manos, R. Xu, F.R. Wang, W.C. Maskell, P.R. Shearing, D.J.L. Brett, Fine structural changes of fluid catalytic catalysts and characterization of coke formed resulting from heavy oil devolatilization, Appl Catal B. 263 (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. Jiménez-García, R. Aguilar-López, R. Maya-Yescas, The fluidized-bed catalytic cracking unit building its future environment, Fuel. 90 (2011) 3531–3541. [CrossRef]

- A. Corma, A. Martínez, Zeolites in refining and petrochemistry, Stud Surf Sci Catal. 157 (2005) 337–366. [CrossRef]

- F. Krumeich, J. Ihli, Y. Shu, W.C. Cheng, J.A. Van Bokhoven, Structural Changes in Deactivated Fluid Catalytic Cracking Catalysts Determined by Electron Microscopy, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 4591–4599. [CrossRef]

- M.E.Z. Velthoen, A. Lucini Paioni, I.E. Teune, M. Baldus, B.M. Weckhuysen, Matrix Effects in a Fluid Catalytic Cracking Catalyst Particle: Influence on Structure, Acidity, and Accessibility, Chemistry - A European Journal. 26 (2020) 11995–12009. [CrossRef]

- F. Krumeich, J. Ihli, Y. Shu, W.C. Cheng, J.A. Van Bokhoven, Structural Changes in Deactivated Fluid Catalytic Cracking Catalysts Determined by Electron Microscopy, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 4591–4599. [CrossRef]

- A. Palčić, V. Valtchev, Synthesis and application of (nano) zeolites, Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry III, Third Edition. 1–10 (2023) 18–40. [CrossRef]

- A. Palčić, V. Valtchev, Synthesis and application of (nano) zeolites, Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry III, Third Edition. 1–10 (2023) 18–40. [CrossRef]

- Q. Almas, M.A. Naeem, M.A.S. Baldanza, J. Solomon, J.C. Kenvin, C.R. Müller, V. Teixeira Da Silva, C.W. Jones, C. Sievers, Transformations of FCC catalysts and carbonaceous deposits during repeated reaction-regeneration cycles, Catal Sci Technol. 9 (2019) 6977–6992. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, Y. Zhang, L. He, C.Q. Jia, Q. Yao, M. Sun, X. Ma, Anti-deactivation of zeolite catalysts for residue fluid catalytic cracking, Appl Catal A Gen. 657 (2023). [CrossRef]

- U.J. Etim, P. Bai, X. Liu, F. Subhan, R. Ullah, Z. Yan, Vanadium and nickel deposition on FCC catalyst: Influence of residual catalyst acidity on catalytic products, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 273 (2019) 276–285. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yan, Y. Fan, X. Bi, C. Lu, Dynamic behaviors of feed jets and catalyst particles in FCC feed injection zone, Chem Eng Sci. 189 (2018) 380–393. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, F. Meirer, C.M. Krest, S. Webb, B.M. Weckhuysen, Relating structure and composition with accessibility of a single catalyst particle using correlative 3-dimensional micro-spectroscopy, Nat Commun. 7 (2016). [CrossRef]

- F. Meirer, D.T. Morris, S. Kalirai, Y. Liu, J.C. Andrews, B.M. Weckhuysen, Mapping metals incorporation of a whole single catalyst particle using element specific X-ray nanotomography, J Am Chem Soc. 137 (2015) 102–105. [CrossRef]

- F. Krumeich, J. Ihli, Y. Shu, W.C. Cheng, J.A. Van Bokhoven, Structural Changes in Deactivated Fluid Catalytic Cracking Catalysts Determined by Electron Microscopy, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 4591–4599. [CrossRef]

- J. Ihli, R.R. Jacob, M. Holler, M. Guizar-Sicairos, A. Diaz, J.C. Da Silva, D. Ferreira Sanchez, F. Krumeich, D. Grolimund, M. Taddei, W.C. Cheng, Y. Shu, A. Menzel, J.A. Van Bokhoven, A three-dimensional view of structural changes caused by deactivation of fluid catalytic cracking catalysts, Nat Commun. 8 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M.D. Argyle, C.H. Bartholomew, Heterogeneous catalyst deactivation and regeneration: A review, Catalysts. 5 (2015) 145–269. [CrossRef]

- F. Krumeich, J. Ihli, Y. Shu, W.C. Cheng, J.A. Van Bokhoven, Structural Changes in Deactivated Fluid Catalytic Cracking Catalysts Determined by Electron Microscopy, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 4591–4599. [CrossRef]

- L. Duarte, L. Garzón, V.G. Baldovino-Medrano, An analysis of the physicochemical properties of spent catalysts from an industrial hydrotreating unit, Catal Today. 338 (2019) 100–107. [CrossRef]

- E.T.C. Vogt, D. Fu, B.M. Weckhuysen, Carbon Deposit Analysis in Catalyst Deactivation, Regeneration, and Rejuvenation, Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. (2023). [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, N. Li, Q. Zhang, C. Li, C. Yang, H. Shan, Studies on the preliminary cracking: The reasons why matrix catalytic function is indispensable for the catalytic cracking of feed with large molecular size, Journal of Energy Chemistry. 25 (2016) 641–653. [CrossRef]

- F. Hernández-Beltrán, E. López-Salinas, R. García-de-León, E. Mogica-Martínez, J.C. Moreno-Mayorga, R. González-Serrano, Study on the deactivation-aging patterns of fluid cracking catalysts in industrial units, Stud Surf Sci Catal. 134 (2001) 87–106. [CrossRef]

- J. Manuel Rêgo Silva, A. Mabel de Morais Araújo, J. Paulo da Costa Evangelista, D. Ribeiro da Silva, A. Duarte Gondim, A. Souza de Araujo, Evaluation of the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters in catalytic pyrolysis process of sunflower oil using Al-MCM-41 and zeolite H-ZSM-5, Fuel. 333 (2023) 126225. [CrossRef]

- K. Patidar, A. Singathia, M. Vashishtha, V. Kumar Sangal, S. Upadhyaya, Investigation of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters approaches to non-isothermal pyrolysis of mustard stalk using model-free and master plots methods, Mater Sci Energy Technol. 5 (2022) 6–14. [CrossRef]

- V. Vasudev, X. Ku, J. Lin, Kinetic study and pyrolysis characteristics of algal and lignocellulosic biomasses, Bioresour Technol. 288 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mr.S.Y. Zakariyaou(薄亚冲), Y. Hua(叶华), O.A.D. Makaou, A Four-Lump Kinetic Model for Atmospheric Residue Conversion in the Fluid Catalytic Cracking Unit: Effect of the Inlet Gas Oil Temperature and Catalyst-Oil Weight Ratio on the Catalytic Reaction Behavior, East African Scholars Journal of Engineering and Computer Sciences. 6 (2023) 39–42. [CrossRef]

- W. Cui, D. Zhu, J. Tan, N. Chen, D. Fan, J. Wang, J. Han, L. Wang, P. Tian, Z. Liu, Synthesis of mesoporous high-silica zeolite Y and their catalytic cracking performance, Chinese Journal of Catalysis. 43 (2022) 1945–1954. [CrossRef]

- M. Thommes, K. Kaneko, A. V. Neimark, J.P. Olivier, F. Rodriguez-Reinoso, J. Rouquerol, K.S.W. Sing, Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report), Pure and Applied Chemistry. 87 (2015) 1051–1069. [CrossRef]

- INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY DIVISION COMMISSION ON COLLOID AND SURFACE CHEMISTRY INCLUDING CATALYSIS* REPORTING PHYSISORPTION DATA FOR GAS/SOLID SYSTEMS with Special Reference to the Determination of Surface Area and Porosity Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems-with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity, 1985.

- Z.A. Alothman, A review: Fundamental aspects of silicate mesoporous materials, Materials. 5 (2012) 2874–2902. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Z. Shen, J. Gong, H. Liu, Influences of regeneration atmospheres on structural transformation and renderability of FCC catalyst, Chin J Chem Eng. (2023). [CrossRef]

- L. Haiyan, C. Liyuan, W. Baoying, F. Yu, S. Gang, B. Xaojun, In-situ Synthesis and Catalytic Properties of ZSM-5/Rectorite Composites as Propylene Boosting Additive in Fluid Catalytic Cracking Process *, 2012.

- D. Hua, Z. Zhou, Deactivation of Mesoporous Titanosilicate-supported WO3 Catalyst for Metathesis of Butene to Propene by Coke, Journal of Thermodynamics & Catalysis. 07 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M.A. Alabdullah, T. Shoinkhorova, A. Dikhtiarenko, S. Ould-Chikh, A. Rodriguez-Gomez, S.H. Chung, A.O. Alahmadi, I. Hita, S. Pairis, J.L. Hazemann, P. Castaño, J. Ruiz-Martinez, I. Morales Osorio, K. Almajnouni, W. Xu, J. Gascon, Understanding catalyst deactivation during the direct cracking of crude oil, Catal Sci Technol. 12 (2022) 5657–5670. [CrossRef]

- V.G. Baldovino-Medrano, V. Niño-Celis, R. Isaacs-Giraldo, E. Refugio, Systematic analysis of the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms recorded for a series of microporous-mesoporous amorphous aluminosilicates using classical methods, n.d.

- G. Lu, X. Lu, P. Liu, Reactivation of spent FCC catalyst by mixed acid leaching for efficient catalytic cracking, Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 92 (2020) 236–242. [CrossRef]

- P. Palmay, C. Medina, C. Donoso, D. Barzallo, J.C. Bruno, Catalytic pyrolysis of recycled polypropylene using a regenerated FCC catalyst, Clean Technol Environ Policy. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Mathieu, A. Corma, M. Echard, M. Bories, Single and combined Fluidized Catalytic Cracking (FCC) catalyst deactivation by iron and calcium metal–organic contaminants, Appl Catal A Gen. 469 (2014) 451–465. [CrossRef]

- I. Cora, I. Dódony, P. Pekker, Electron crystallographic study of a kaolinite single crystal, Appl Clay Sci. 90 (2014) 6–10. [CrossRef]

- A.F. Wright, M.S. Lehmann, The structure of quartz at 25 and 590°C determined by neutron diffraction, J Solid State Chem. 36 (1981) 371–380. [CrossRef]

- F. Caucia, Structural aspects of oxidation-dehydrogenation in staurolite The Crystal Chemistry of Mercury Minerals View project Gems and gem minerals View project, n.d. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299446509.

- I. Cora, I. Dódony, P. Pekker, Electron crystallographic study of a kaolinite single crystal, Appl Clay Sci. 90 (2014) 6–10. [CrossRef]

- Y.X. Wang, H. Gies, B. Marler, U. Müller, Synthesis and crystal structure of zeolite RUB-41 obtained as calcination product of a layered precursor: A systematic approach to a new synthesis route, Chemistry of Materials. 17 (2005) 43–49. [CrossRef]

- X.-H. Peng, Y.-Z. Li, L.-X. Cai, L.-F. Wang, J.-G. Wu, A novel polyoxometalate supramolecular compound: [La(H 2 O) 9 ] 2 [V 10 O 28 ]·8H 2 O, Acta Crystallogr Sect E Struct Rep Online. 58 (2002) i111–i113. [CrossRef]

- S. Koide, Electrical Properties of LixNi(1−x)O Single Crystals, J Physical Soc Japan. 20 (1965) 123–132. [CrossRef]

- C.H. Wei, L.F. Dahl, The Molecular Structure of a Tricyclic Complex, [SFe(CO)3]2, Inorg Chem. 4 (1965) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- R. -S Zhou, R.L. Snyder, Structures and transformation mechanisms of the η, γ and θ transition aluminas, Urn:Issn:0108-7681. 47 (1991) 617–630. [CrossRef]

- M.D. Foster, O.D. Friedrichs, R.G. Bell, F.A.A. Paz, J. Klinowski, Chemical evaluation of hypothetical uninodal zeolites, J Am Chem Soc. 126 (2004) 9769–9775. [CrossRef]

- S. Komarneni, H. Katsuki, S. Furuta, Novel honeycomb structure: a microporous ZSM-5 and macroporous mullite composite, J Mater Chem. 8 (1998) 2327–2329. [CrossRef]

- F.J. Wicks, Status of the reference X-ray powder-diffraction patterns for the serpentine minerals in the PDF database—1997, Powder Diffr. 15 (2000) 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hu, Q. Yong, L. He, Y. Gu, J. Zeng, Structural evolution of kaolinite in muddy intercalation under microwave heating, Mater Res Express. 8 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Nong, X. Yang, L. Zeng, J. Liu, Qualitative and quantitative phase analyses of Pingguo bauxite mineral using X-ray powder diffraction and the Rietveld method, Powder Diffr. 22 (2007) 300–302. [CrossRef]

- T. Murugesan, S. Ramesh, J. Gopalakrishnan, C.N.R. Rao, Ternary vanadium sulfides, J Solid State Chem. 44 (1982) 119–125. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Frolov, R.P. Krentsis, F.A. Sidorenko, P. V. Gel’d, Some physical properties of Co2Si and Ni2Si in the 10-350 °k temperature range, Soviet Physics Journal. 15 (1972) 418–420. [CrossRef]

- Polyhedral thermal expansion in the TiO 2 polymorphs; refinement of the crystal structures of rutile and brookite at high temperature | The Canadian Mineralogist | GeoScienceWorld, (n.d.). https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/canmin/article-abstract/17/1/77/11318/Polyhedral-thermal-expansion-in-the-TiO-2?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed October 4, 2023).

- U.J. Etim, B. Xu, P. Bai, R. Ullah, F. Subhan, Z. Yan, Role of nickel on vanadium poisoned FCC catalyst: A study of physiochemical properties, Journal of Energy Chemistry. 25 (2016) 667–676. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mathieu, A. Corma, M. Echard, M. Bories, Single and combined Fluidized Catalytic Cracking (FCC) catalyst deactivation by iron and calcium metal-organic contaminants, Appl Catal A Gen. 469 (2014) 451–465. [CrossRef]

- B. Behera, S.S. Ray, Structural changes of FCC catalyst from fresh to regeneration stages and associated coke in a FCC refining unit: A multinuclear solid state NMR approach, Catal Today. 141 (2009) 195–204. [CrossRef]

- Y. jie Wang, C. Wang, L. ling Li, Y. Chen, C. hong He, L. Zheng, Assessment of ecotoxicity of spent fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) refinery catalysts on Raphidocelis subcapitata and predictive models for toxicity, Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 222 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Xu, X. Liu, R.J. Madon, Pathways for Y zeolite destruction: The role of sodium and vanadium, J Catal. 207 (2002) 237–246. [CrossRef]

- K. Wijayanti, K. Leistner, S. Chand, A. Kumar, K. Kamasamudram, N.W. Currier, A. Yezerets, L. Olsson, Deactivation of Cu-SSZ-13 by SO2 exposure under SCR conditions, Catal Sci Technol. 6 (2016) 2565–2579. [CrossRef]

- R. Jonsson, P.H. Ho, A. Wang, M. Skoglundh, L. Olsson, The impact of lanthanum and zeolite structure on hydrocarbon storage, Catalysts. 11 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B.B. Hallac, J.C. Brown, E. Stavitski, R.G. Harrison, M.D. Argyle, In situ UV-visible assessment of iron-based high-temperature water-gas shift catalysts promoted with Lanthana: An extent of reduction study, Catalysts. 8 (2018). [CrossRef]

- L. Alcaraz, O. Rodríguez-Largo, M. Álvarez-Montes, F.A. López, C. Baudín, Effect of lanthanum content on physicochemical properties and thermal evolution of spent and beneficiated spent FCC catalysts, Ceram Int. 48 (2022) 17691–17702. [CrossRef]

- M.N. Haddadnezhad, A. Babaei, M.J. Molaei, A. Ataie, Synthesis and characterization of lanthanum nickelate nanoparticles with Rudllesden-Popper crystal structure for cathode materials of solid oxide fuel cells, Journal of Ultrafine Grained and Nanostructured Materials. 53 (2020) 98–109. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou, J. Zhao, J. Zhang, T. Zhang, M. Ye, Z. Liu, Regeneration of catalysts deactivated by coke deposition: A review, Chinese Journal of Catalysis. 41 (2020) 1048–1061. [CrossRef]

- Y.L. Tsai, E. Huang, Y.H. Li, H.T. Hung, J.H. Jiang, T.C. Liu, J.N. Fang, H.F. Chen, Raman spectroscopic characteristics of zeolite group minerals, Minerals. 11 (2021) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, Q. Guo, L. Ding, Y. Gong, G. Yu, Studying effects of solid structure evolution on gasification reactivity of coal chars by in-situ Raman spectroscopy, Fuel. 270 (2020) 117603. [CrossRef]

- A. Sadezky, H. Muckenhuber, H. Grothe, R. Niessner, U. Pöschl, Raman microspectroscopy of soot and related carbonaceous materials: Spectral analysis and structural information, Carbon N Y. 43 (2005) 1731–1742. [CrossRef]

- I. Pala-Rosas, J.L. Contreras, J. Salmones, R. López-Medina, D. Angeles-Beltrán, B. Zeifert, J. Navarrete-Bolaños, N.N. González-Hernández, Effects of the Acidic and Textural Properties of Y-Type Zeolites on the Synthesis of Pyridine and 3-Picoline from Acrolein and Ammonia, Catalysts. 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- A.F. Wright, J.S. Bailey, Organic carbon, total carbon, and total nitrogen determinations in soils of variable calcium carbonate contents using a Leco CN-2000 dry combustion analyzer, Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1081/CSS-120001118. 32 (2011) 3243–3258. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ruiz-Morales, A.D. Miranda-Olvera, B. Portales-Martínez, J.M. Domínguez, Determination of13C NMR Chemical Shift Structural Ranges for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and PAHs in Asphaltenes: An Experimental and Theoretical Density Functional Theory Study, Energy and Fuels. 33 (2019) 7950–7970. [CrossRef]

- S. Kukade, P. Kumar, P.V.C. Rao, N. V. Choudary, Comparative study of attrition measurements of commercial FCC catalysts by ASTM fluidized bed and jet cup test methods, Powder Technol. 301 (2016) 472–477. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Han, D. Li, Z. Zhang, X. Ma, Study on attrition of spherical-shaped Mo/HZSM-5 catalyst for methane dehydro-aromatization in a gas–solid fluidized bed, Chin J Chem Eng. 38 (2021) 172–183. [CrossRef]

- F. Meirer, D.T. Morris, S. Kalirai, Y. Liu, J.C. Andrews, B.M. Weckhuysen, Mapping metals incorporation of a whole single catalyst particle using element specific X-ray nanotomography, J Am Chem Soc. 137 (2015) 102–105. [CrossRef]

- S. Kukade, P. Kumar, P.V.C. Rao, N. V. Choudary, Comparative study of attrition measurements of commercial FCC catalysts by ASTM fluidized bed and jet cup test methods, Powder Technol. 301 (2016) 472–477. [CrossRef]

- C.R. Bemrose, J. Bridgwater, A review of attrition and attrition test methods, Powder Technol. 49 (1987) 97–126. [CrossRef]

- W.L. Forsythe, W.R. Hertwig, Attrition Characteristics of Fluid Cracking Catalysts, Ind Eng Chem. 41 (1949) 1200–1206. [CrossRef]

- J. Werther, J. Reppenhagen, Catalyst attrition in fluidized-bed systems, AIChE Journal. 45 (1999) 2001–2010. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Whitcombe, I.E. Agranovski, R.D. Braddock, Attrition due to mixing of hot and cold FCC catalyst particles, Powder Technol. 137 (2003) 120–130. [CrossRef]

- J. Hao, Y. Zhao, M. Ye, Z. Liu, Influence of Temperature on Fluidized-Bed Catalyst Attrition Behavior, Chem Eng Technol. 39 (2016) 927–934. [CrossRef]

- R. Miandad, M.A. Barakat, M. Rehan, A.S. Aburiazaiza, I.M.I. Ismail, A.S. Nizami, Plastic waste to liquid oil through catalytic pyrolysis using natural and synthetic zeolite catalysts, Waste Management. 69 (2017) 66–78. [CrossRef]

- A.W. Chester, Studies on the Metal Poisoning and Metal Resistance of Zeolitic Cracking Catalysts, Ind Eng Chem Res. 26 (1987) 863–869. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu, W. Zhou, J. Wang, Z. Li, J. Ma, Characterization and analysis of carbon deposited during the dry reforming of methane over Ni/La2O3/Al2O3 catalysts, Cuihua Xuebao/Chinese Journal of Catalysis. 30 (2009) 1076–1084. [CrossRef]

- J.Z. Luo, Z.L. Yu, C.F. Ng, C.T. Au, CO2/CH4 reforming over Ni-La2O3/5A: An investigation on carbon deposition and reaction steps, J Catal. 194 (2000) 198–210. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, X.E. Verykios, ~ APPLI ED CATALYSI S Carbon dioxide reforming of methane to synthesis gas over Ni/La203 catalysts, 1996.

- S. Ramukutty, E. Ramachandran, Reaction Rate Models for the Thermal Decomposition of Ibuprofen Crystals, Journal of Crystallization Process and Technology. 04 (2014) 71–78. [CrossRef]

- R. Arjmandi, A. Hassan, M.K.M. Haafiz, Z. Zakaria, M.S. Islam, Effect of hydrolysed cellulose nanowhiskers on properties of montmorillonite/polylactic acid nanocomposites, Int J Biol Macromol. 82 (2016) 998–1010. [CrossRef]

- D. Trache, Comments on “thermal degradation behavior of hypochlorite-oxidized starch nanocrystals under different oxidized levels,” Carbohydr Polym. 151 (2016) 535–537. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Farrukh, K.M. Butt, K.K. Chong, W.S. Chang, Photoluminescence emission behavior on the reduced band gap of Fe doping in CeO2-SiO2 nanocomposite and photophysical properties, Journal of Saudi Chemical Society. 23 (2019) 561–575. [CrossRef]

- M. Del Mar Graciani, A. Rodríguez, M. Muñoz, M.L. Moyá, Micellar solutions of sulfobetaine surfactants in water-ethylene glycol mixtures: Surface tension, fluorescence, spectroscopic, conductometric, kinetic studies, Langmuir. 21 (2005) 7161–7169. [CrossRef]

- G. Bhardwaj, M. Kumar, P.K. Mishra, S.N. Upadhyay, Kinetic analysis of the slow pyrolysis of paper wastes, Biomass Convers Biorefin. 13 (2023) 3087–3100. [CrossRef]

- O. Verdeş, A. Popa, S. Borcănescu, M. Suba, V. Sasca, Thermogravimetry Applied for Investigation of Coke Formation in Ethanol Conversion over Heteropoly Tungstate Catalysts, Catalysts. 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Saadatkhah, A. Carillo Garcia, S. Ackermann, P. Leclerc, M. Latifi, S. Samih, G.S. Patience, J. Chaouki, Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Thermogravimetric analysis—TGA, Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering. 98 (2020) 34–43. [CrossRef]

- J. Taynara, B. Cunha, V.M. Castro, D. Santana Da Silva, D. De Aguiar Pontes, V. Lima Da Silva, L. Antônio, M. Pontes, R.C. Santos, Coke Deposition on Cracking Catalysts Study by Thermogravimetric Analysis, International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications Www.Ijera.Com. 10 (2020) 43–47. [CrossRef]

- A. Marcilla, A. Gómez-Siurana, A.O. Odjo, R. Navarro, D. Berenguer, Characterization of vacuum gas oil-low density polyethylene blends by thermogravimetric analysis, Polym Degrad Stab. 93 (2008) 723–730. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, Á. Ibarra, J. Bilbao, J.M. Arandes, P. Castaño, Assessment of thermogravimetric methods for calculating coke combustion-regeneration kinetics of deactivated catalyst, Chem Eng Sci. 171 (2017) 459–470. [CrossRef]

- A.T. Aguayo, A.G. Gayubo, A. Atutxa, B. Valle, J. Bilbao, Regeneration of a HZSM-5 zeolite catalyst deactivated in the transformation of aqueous ethanol into hydrocarbons, Catal Today. 107–108 (2005) 410–416. [CrossRef]

- C. Ran, Y. Liu, A.R. Siddiqui, A.A. Siyal, X. Mao, Q. Kang, J. Fu, W. Ao, J. Dai, Pyrolysis of textile dyeing sludge in fluidized bed: Analysis of products, and migration and distribution of heavy metals, J Clean Prod. 241 (2019). [CrossRef]

| Item | value |

|---|---|

| Density (20°C) | 0.9215 g/cm3 |

| API | 22.054 |

| Aniline point | 52.9 °C |

| Residual carbon | 5.5% |

| Ni | 22.9 ppm |

| V | 0.3 ppm |

| Fe | 3.2 ppm |

| Sulfur content | 0.24 m% |

| Nitrogen content | 0.17 m% |

| Molecular weight | 462 |

| Distillation TBP | °C |

| 50% | 343.0 |

| 90% | 378.0 |

| 95% | 385.0 |

| Samples |

SBET (m2g-1) |

Sext (m2g-1) |

Smicro (m2g-1) |

Vtotal (cm3g-1) |

Vmicro (cm3g-1) |

Microporosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 158.13 | 94.24 | 63.8825 | 0.147 | 0.028 | 40.39 |

| Regenerated | 76.78 | 38.55 | 38.2327 | 0.098 | 0.017 | 49.79 |

| Spent | 57.45 | 28.87 | 28.5726 | 0.077 | 0.012 | 49.73 |

| property | Fresh | Regenerated | Spent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Composition (%) | |||

| CO2 | 9.64 | 3.56 | 9.58 |

| N | 0.27 | ||

| Na2O | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| MgO | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Al2O3 | 50.71 | 50.28 | 47.04 |

| SiO2 | 34.65 | 39.04 | 37.35 |

| P2O5 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.35 |

| SO3 | 0.33 | 0.2 | 0.26 |

| K2O | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

| CaO | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| TiO2 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| V2O5 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| Fe2O3 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Co2O3 | 0.12 | 0.08 | |

| NiO | 2.05 | 1.52 | |

| CuO | 0.004 | ||

| ZnO | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Ga2O3 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| GeO2 | 0.004 | ||

| Rb2O | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| Y2O3 | 0.66 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| ZrO2 | 0.003 | 0.004 | |

| Sb2O3 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| La2O3 | 1.18 | 1.66 | 1.61 |

| CeO2 | 0.48 | 0.32 | |

| . | . | Fresh catalyst | Regenerated catalyst | Spent catalyst | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone | T °C | Ea Jmol-1 (*102) |

Jmol-1 (*10-2) |

Jmol-1K-1 (*105) |

Jmol-1 (*106) |

Fitting equation | R2 | Ea Jmol-1 (*102) |

Jmol-1 (*10-2) |

Jmol-1K-1 (*105) |

Jmol-1 (*106) |

Fitting equation | R2 | Ea Jmol-1 (*102) |

Jmol-1 (*10-2) |

Jmol-1K-1 (*105) |

Jmol-1 (*106) |

Fitting equation | R2 |

| 1 | 100-300 | 10.85 | -3.03 | 51.73 | 5.34 | Y= -0.13065x-0.0994 | 0.99 | 12.37 | -3.02 | 58.93 | 6.06 | Y= -0.1488x-0.0984 | 0.99 | 42.45 | -2.86 | 202.24 | 20.38 | Y= -0.5106x+0.5913 | 0.98 |

| 2 | 300-450 | 21.44 | -3.00 | 128.89 | 13.10 | Y= -0.2579x+0.318 | 0.98 | 31.01 | -2.94 | 186.42 | 18.85 | Y= -0.373x+0.6749 | 0.99 | 66.63 | -2.84 | 400.58 | 40.26 | Y= -0.8015x+1.0601 | 0.97 |

| 3 | 450-550 | 133.44 | -2.63 | 913.11 | 91.52 | Y= -1.605x+3.2677 | 0.98 | 52.08 | -2.88 | 356.37 | 35.87 | Y= -0.6264x+1.252 | 0.99 | 201.00 | -2.59 | 1380 | 138 | Y= -2.4176x+3.296 | 0.98 |

| 4 | 550-700 | 77.43 | -2.82 | 626.40 | 62.91 | Y= -0.9313x+2.0443 | 0.99 | 79.01 | -2.84 | 639.18 | 64.19 | Y= -0.9503x+1.8307 | 0.99 | 190.16 | -2.65 | 1540 | 154 | Y= -2.2872x+3.2081 | 0.97 |

| 5 | 700-850 | 137.75 | -2.72 | 1290 | 129 | Y= -1.6568x+3.0534 | 0.98 | 164.49 | -2.69 | 1540 | 154 | Y= -1.9784x+3.275 | 0.98 | 134.56 | -2.77 | 1260 | 126 | Y= -1.6185x+2.4638 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).