Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

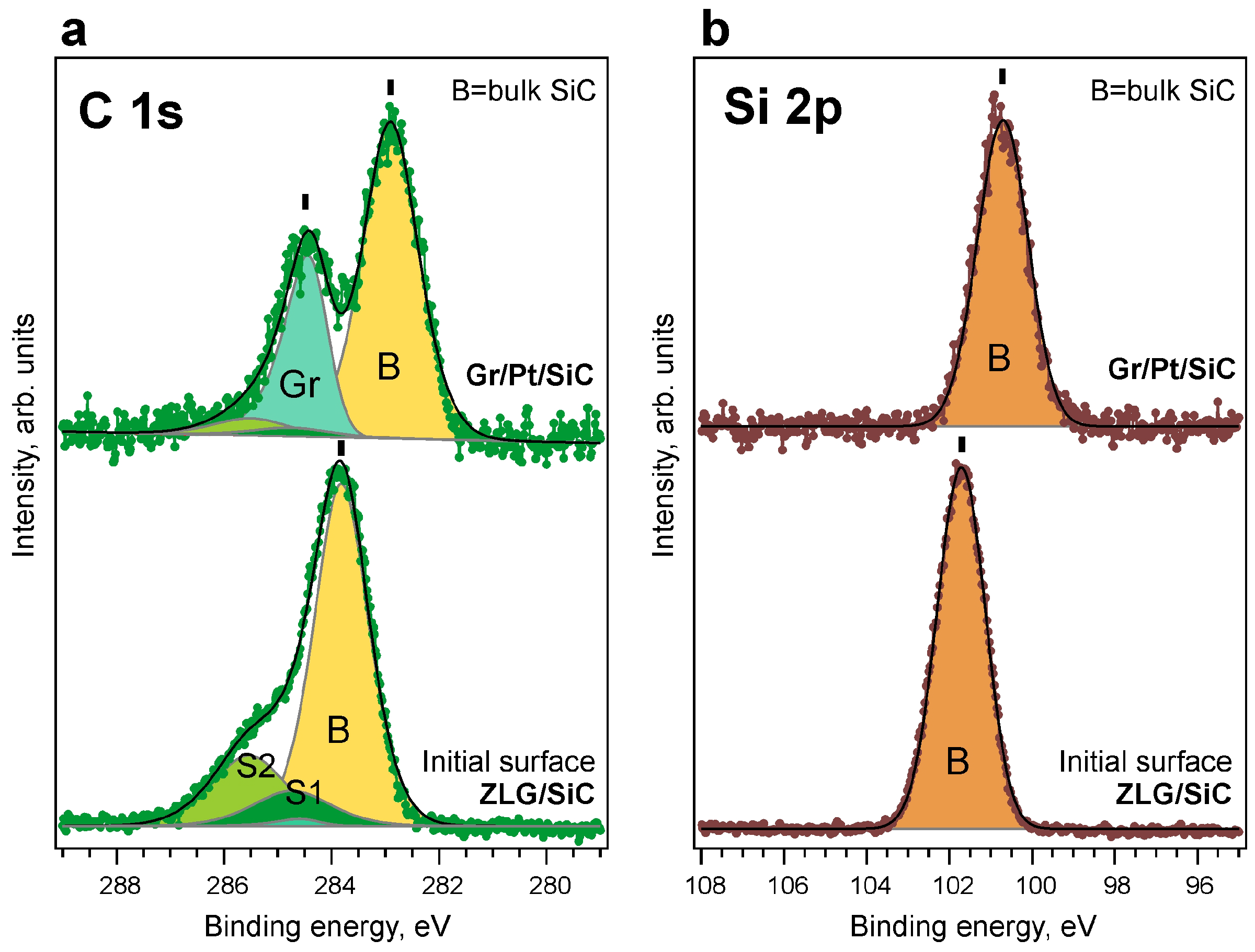

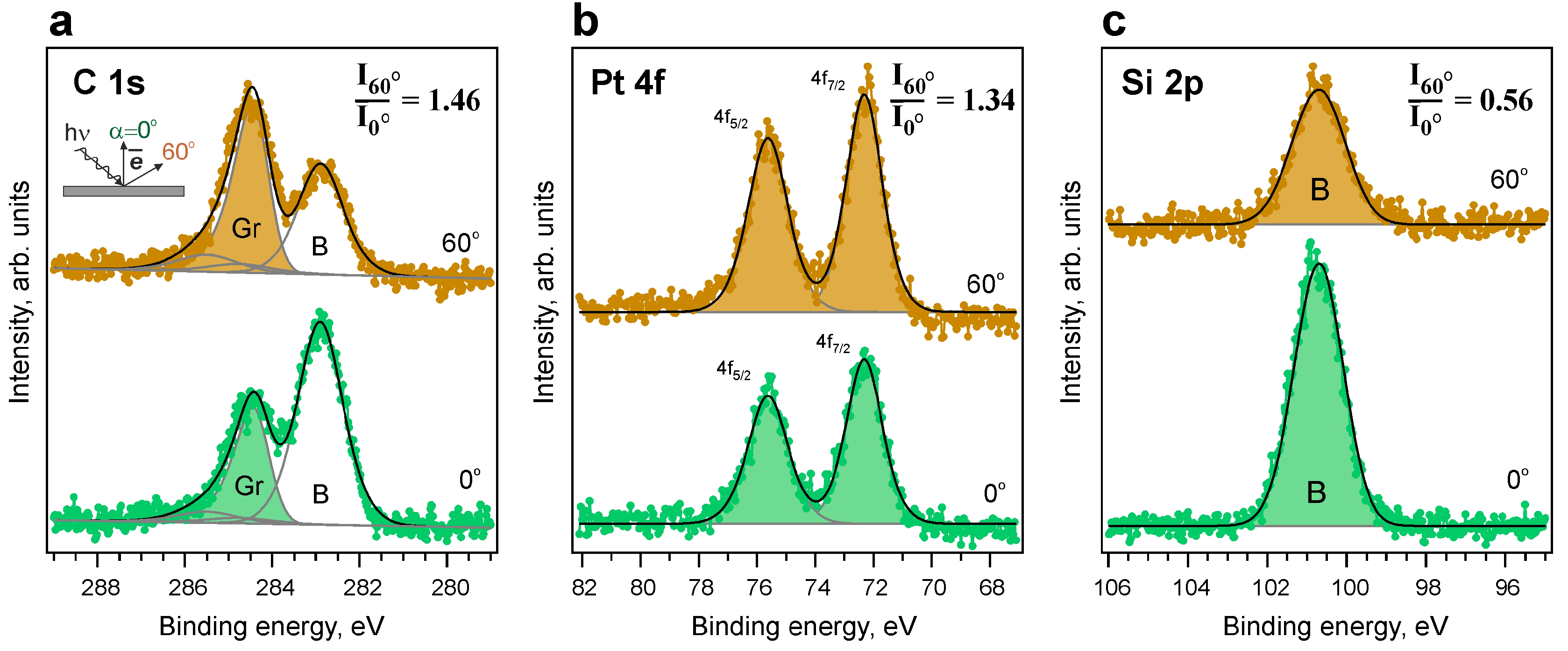

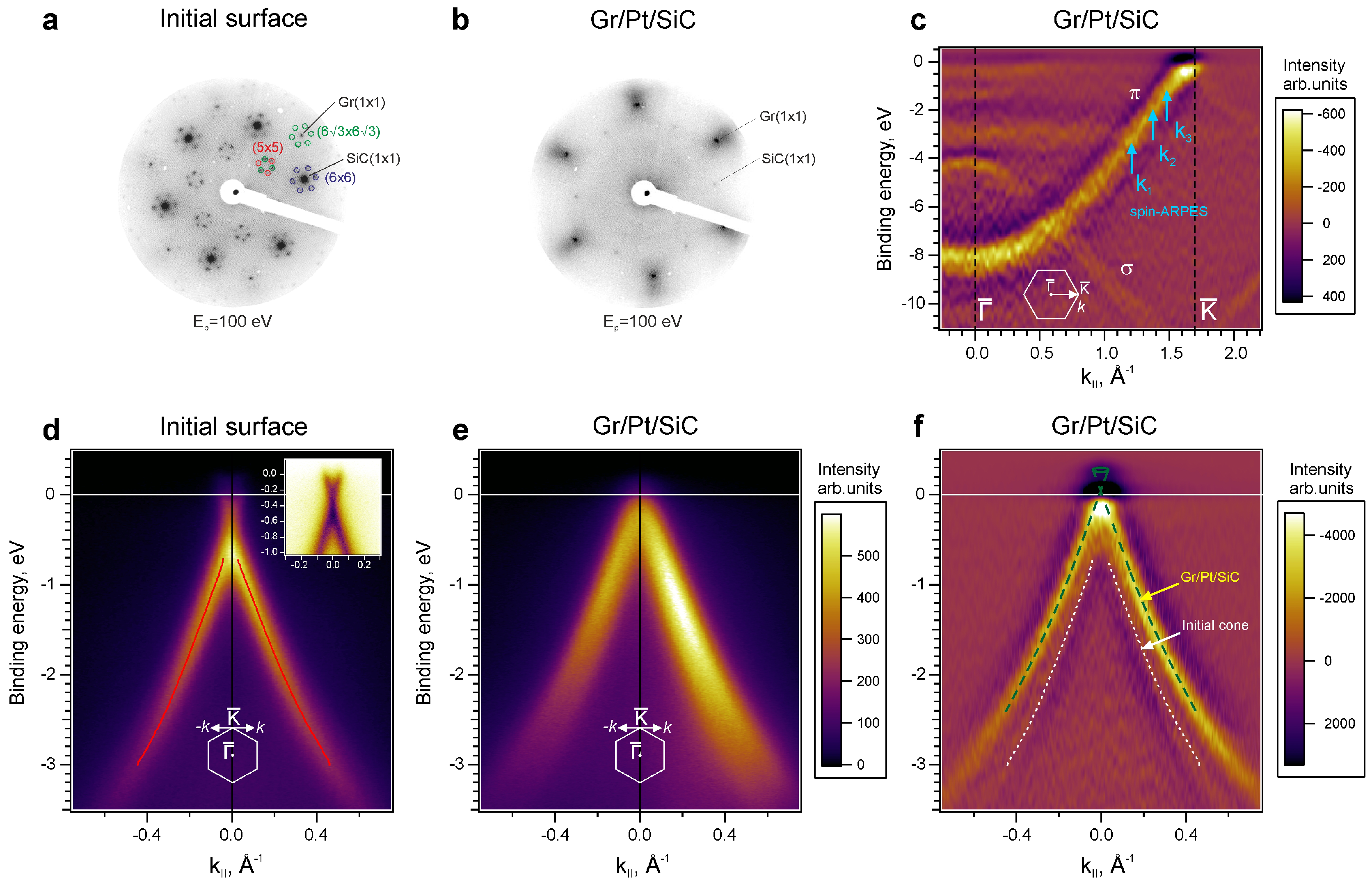

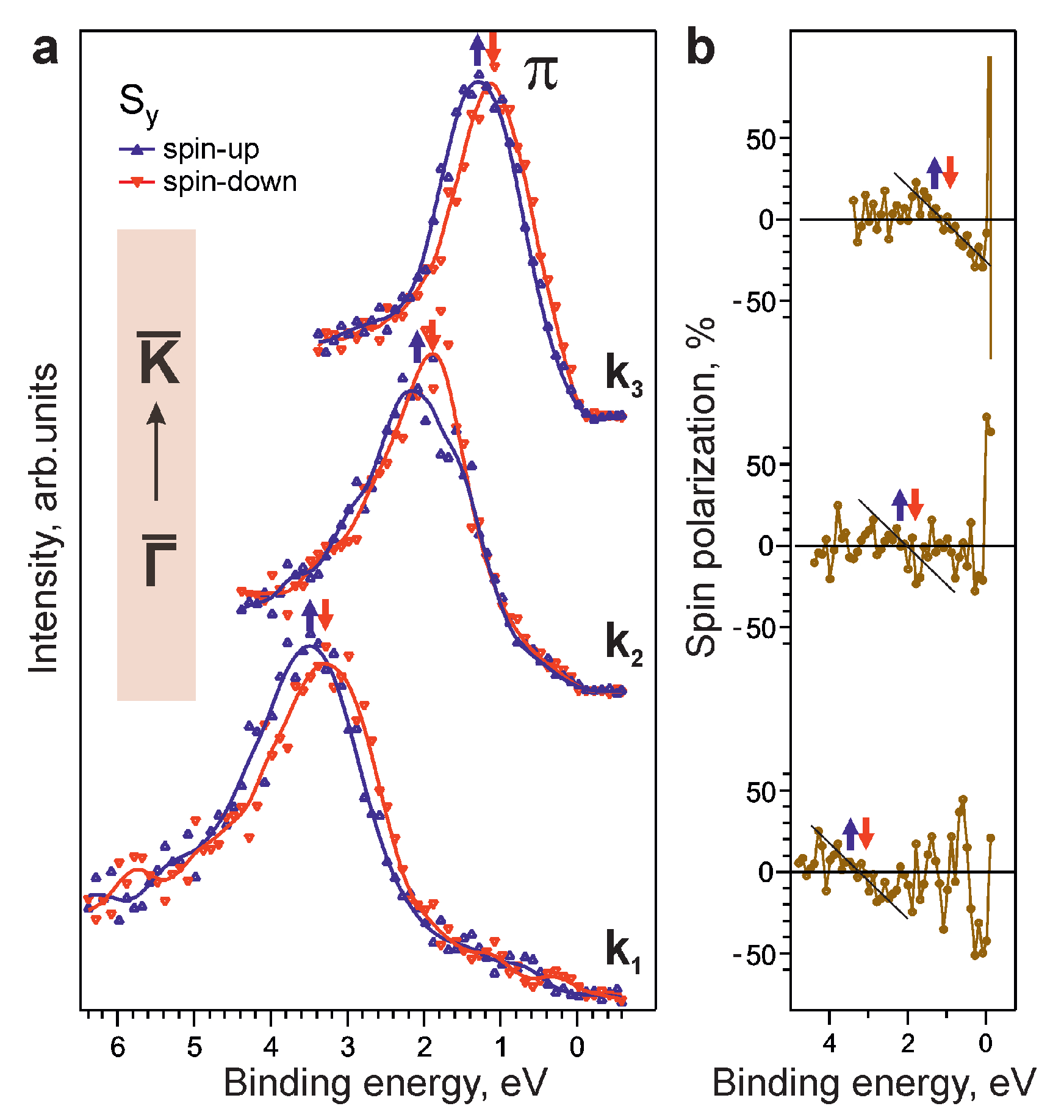

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kane, C.L.; Mele, E.J. Z2 Topological Order and the Quantum Spin Hall Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 146802. [CrossRef]

- Phong, V.T.; Walet, N.R.; Guinea, F. Effective interactions in a graphene layer induced by the proximity to a ferromagnet. 2D Materials 2017, 5, 014004. [CrossRef]

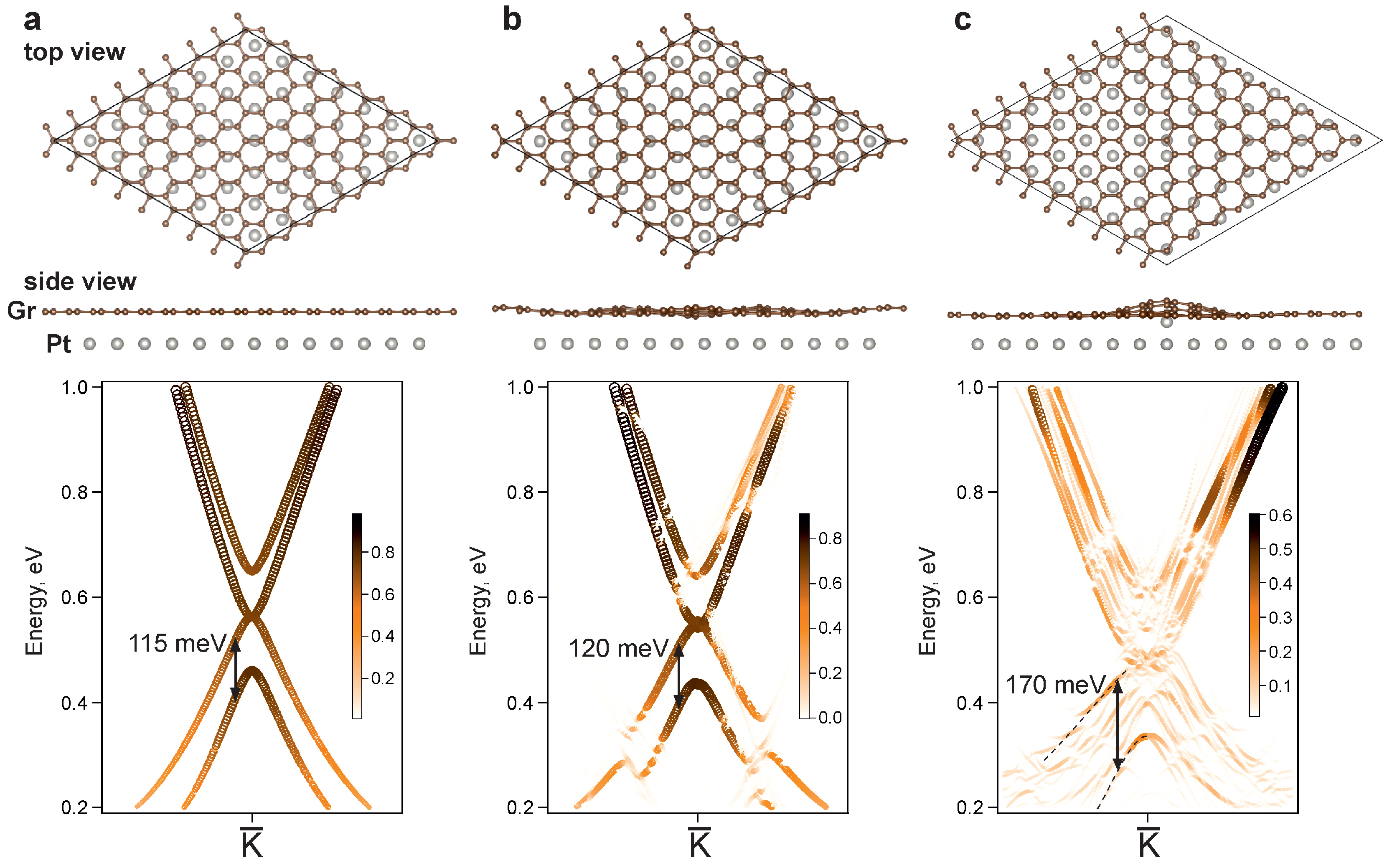

- Eryzhenkov, A.V.; Tarasov, A.V.; Shikin, A.M.; Rybkin, A.G. Non-Trivial Band Topology Criteria for Magneto-Spin-Orbit Graphene. Symmetry 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, F.; Ding, X.M. Rashba spin–orbit coupling induced rectified currents in monolayer graphene with exchange field and sublattice potential. Chinese Physics B 2023, 32, 087103. [CrossRef]

- Shikin, A.M.; Rybkin, A.G.; Marchenko, D.; Rybkina, A.A.; Scholz, M.R.; Rader, O.; Varykhalov, A. Induced spin–orbit splitting in graphene: the role of atomic number of the intercalated metal and pi–d hybridization. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 013016. [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, D.; Varykhalov, A.; Scholz, M.R.; Bihlmayer, G.; Rashba, E.I.; Rybkin, A.; Shikin, A.M.; Rader, O. Giant Rashba splitting in graphene due to hybridization with gold. Nature Communications 2012, 3, 1232, [1208.4265]. [CrossRef]

- Klimovskikh, I.I.; Tsirkin, S.S.; Rybkin, A.G.; Rybkina, A.A.; Filianina, M.V.; Zhizhin, E.V.; Chulkov, E.V.; Shikin, A.M. Nontrivial spin structure of graphene on Pt(111) at the Fermi level due to spin-dependent hybridization. Physical Review B 2014, 90, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, D.; Varykhalov, A.; Sánchez-Barriga, J.; Seyller, T.; Rader, O. Rashba splitting of 100 meV in Au-intercalated graphene on SiC. Applied Physics Letters 2016, 108, 172405, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.4947286/14478504/172405_1_online.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Krivenkov, M.; Golias, E.; Marchenko, D.; Sánchez-Barriga, J.; Bihlmayer, G.; Rader, O.; Varykhalov, A. Nanostructural origin of giant Rashba effect in intercalated graphene. 2D Materials 2017, 4, 035010. [CrossRef]

- Rybkin, A.G.; Rybkina, A.A.; Otrokov, M.M.; Vilkov, O.Y.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Petukhov, A.E.; Filianina, M.V.; Voroshnin, V.Y.; Rusinov, I.P.; Ernst, A.; Arnau, A.; Chulkov, E.V.; Shikin, A.M. Magneto-Spin–Orbit Graphene: Interplay between Exchange and Spin–Orbit Couplings. Nano Letters 2018, 18, 1564–1574. [CrossRef]

- Rybkin, A.G.; Tarasov, A.V.; Rybkina, A.A.; Usachov, D.Y.; Petukhov, A.E.; Eryzhenkov, A.V.; Pudikov, D.A.; Gogina, A.A.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Di Santo, G.; Petaccia, L.; Varykhalov, A.; Shikin, A.M. Sublattice Ferrimagnetism in Quasifreestanding Graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 226401. [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Colmenárez, L.; Peralta, M.; Mireles, F.; Medina, E. Proximity-induced spin-orbit effects in graphene on Au. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 085411. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Murakami, S.; Chen, T.W.; Nagaosa, N. Intrinsic Spin Hall Effect in Platinum: First-Principles Calculations. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100, 096401. [CrossRef]

- Klimovskikh, I.I.; Vilkov, O.; Usachov, D.Y.; Rybkin, A.G.; Tsirkin, S.S.; Filianina, M.V.; Bokai, K.; Chulkov, E.V.; Shikin, A.M. Variation of the character of spin-orbit interaction by Pt intercalation underneath graphene on Ir(111). Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 165402. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, N.; Gebeyehu, Z.M.; Vera, A.; Zhao, T.; Wang, K.; De La Fuente Duran, A.; Bersch, B.; Bowen, T.; Knappenberger, K.L.; Robinson, J.A. Epitaxial graphene/silicon carbide intercalation: a minireview on graphene modulation and unique 2D materials. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 15440–15447. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Johansson, L.I.; Niu, Y.; Zakharov, A.a.; Janzén, E.; Virojanadara, C. High thermal stability quasi-free-standing bilayer graphene formed on 4H-SiC(0001) via platinum intercalation. Carbon 2014, 79, 631–635. [CrossRef]

- Premlal, B.; Cranney, M.; Vonau, F.; Aubel, D.; Casterman, D.; De Souza, M.M.; Simon, L. Surface intercalation of gold underneath a graphene monolayer on SiC(0001) studied by scanning tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy. Applied Physics Letters 2009, 94, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Yagyu, K.; Tajiri, T.; Kohno, A.; Takahashi, K.; Tochihara, H.; Tomokage, H.; Suzuki, T. Fabrication of a single layer graphene by copper intercalation on a SiC(0001) surface. Applied Physics Letters 2014, 104, 053115. [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.J.; Yang, J.W.; Lee, P.R.; Kim, J.G.; Ryu, M.T.; Park, H.M.; Lee, G.; Hwang, C.C.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, J.S.; Chung, J.W. Spin-induced band modifications of graphene through intercalation of magnetic iron atoms. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 3824. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xia, Q.; Gao, H.; Dong, S.; Zhao, G.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, F.; Hu, T. Fabrication and mechanism of Pb-intercalated graphene on SiC. Applied Surface Science 2021, 569, 151012. [CrossRef]

- Gierz, I.; Suzuki, T.; Weitz, R.T.; Lee, D.S.; Krauss, B.; Riedl, C.; Starke, U.; Höchst, H.; Smet, J.H.; Ast, C.R.; Kern, K. Electronic decoupling of an epitaxial graphene monolayer by gold intercalation. Physical Review B 2010, 81, 235408. [CrossRef]

- Shikin, A.M.; Rybkina, A.A.; Rybkin, A.G.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Skirdkov, P.N.; Zvezdin, K.A.; Zvezdin, A.K. Spin current formation at the graphene/Pt interface for magnetization manipulation in magnetic nanodots. Applied Physics Letters 2014, 105, 042407. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, C.; Coletti, C.; Starke, U. Structural and electronic properties of epitaxial graphene on SiC (0 0 0 1): a review of growth, characterization, transfer doping and hydrogen intercalation. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2010, 43, 374009. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, C.; Coletti, C.; Iwasaki, T.; Zakharov, A.A.; Starke, U. Quasi-free-standing epitaxial graphene on SiC obtained by hydrogen intercalation. Physical Review Letters 2009, 103, 1–4, [arXiv:0911.1953v1]. [CrossRef]

- Emtsev, K.V.; Speck, F.; Seyller, T.; Ley, L.; Riley, J.D. Interaction, growth, and ordering of epitaxial graphene on SiC{0001} surfaces: A comparative photoelectron spectroscopy study. Physical Review B - Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2008, 77, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Rybkina, A.A.; Filnov, S.O.; Tarasov, A.V.; Danilov, D.V.; Likholetova, M.V.; Voroshnin, V.Y.; Pudikov, D.A.; Glazkova, D.A.; Eryzhenkov, A.V.; Eliseyev, I.A.; Davydov, V.Y.; Shikin, A.M.; Rybkin, A.G. Quasi-freestanding graphene on SiC(0001) via cobalt intercalation of zero-layer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 155423. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.; Shin, W.; Ryu, S.; Huh, M.; Cha, S.; Kim, K. Graphene p-n junction formed on SiC(0001) by Au intercalation. Journal of the Korean Physical Society 2021, 78, 40. [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Biesinger, M.C.; Linford, M.R. The Gaussian-Lorentzian Sum, Product, and Convolution (Voigt) functions in the context of peak fitting X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) narrow scans. Applied Surface Science 2018, 447, 548–553. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 155108. [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Kino, H. Numerical atomic basis orbitals from H to Kr. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 195113. [CrossRef]

- Troullier, N.; Martins, J.L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Physical review B 1991, 43, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13244–13249. [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Journal of Applied Crystallography 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [CrossRef]

- Merino, P. Dissertation “Structural characterization of epitaxial graphene”; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2014.

- Emtsev, K. Dissertation “Electronic and structural characterizations of unreconstructed SiC(0001) surfaces and the growth of graphene overlayers”; Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 2009.

- Tedesco, J.L.; Rowe, J.E.; Nemanich, R.J. Conducting atomic force microscopy studies of nanoscale cobalt silicide Schottky barriers on Si(111) and Si(100). Journal of Applied Physics 2009, 105, 083721. [CrossRef]

- Rybkin, A.G.; Rybkina, A.A.; Tarasov, A.V.; Pudikov, D.A.; Klimovskikh, I.I.; Vilkov, O.Y.; Petukhov, A.E.; Usachov, D.Y.; Estyunin, D.A.; Voroshnin, V.Y.; Varykhalov, A.; Di Santo, G.; Petaccia, L.; Schwier, E.F.; Shimada, K.; Kimura, A.; Shikin, A.M. A new approach for synthesis of epitaxial nano-thin Pt5Gd alloy via intercalation underneath a graphene. Applied Surface Science 2020, 526, 146687. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, C.; Starke, U.; Bernhardt, J.; Franke, M.; Heinz, K. Structural properties of the graphene-SiC(0001) interface as a key for the preparation of homogeneous large-terrace graphene surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 245406. [CrossRef]

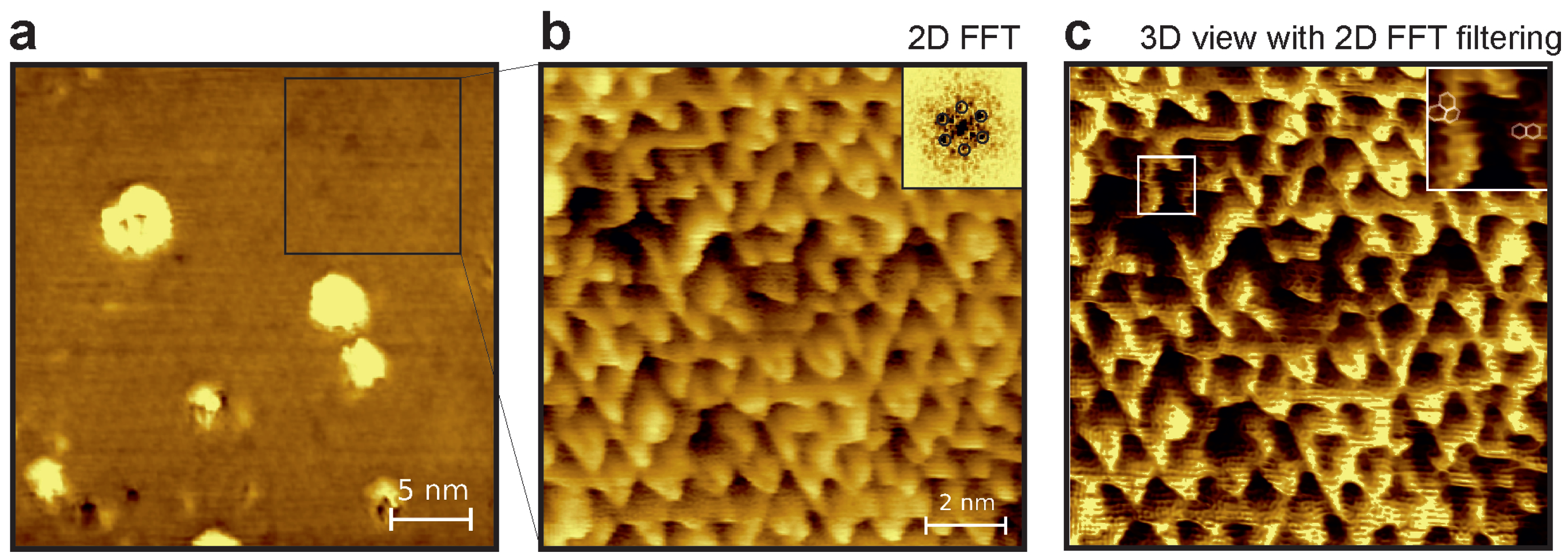

- Merino, P.; Sv̌ec, M.; Pinardi, A.L.; Otero, G.; Martín-Gago, J.A. Strain-Driven Moiré Superstructures of Epitaxial Graphene on Transition Metal Surfaces. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5627–5634. [CrossRef]

- Otero, G.; González, C.; Pinardi, A.L.; Merino, P.; Gardonio, S.; Lizzit, S.; Blanco-Rey, M.; Van de Ruit, K.; Flipse, C.F.J.; Méndez, J.; de Andrés, P.L.; Martín-Gago, J.A. Ordered Vacancy Network Induced by the Growth of Epitaxial Graphene on Pt(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 216102. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Pang, R.; Shi, X. Molecular Precursor Induced Surface Reconstruction at Graphene/Pt(111) Interfaces. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2015, 119, 22534–22541. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).