1. Introduction

Discordance among the dimensions of sexual orientation presents both theoretical and practical challenges for the study of sexual minorities [

1]. Theoretically, scientists have conceived of human sexuality as “oriented” to more or less consistent behavior among three distinct experiences: sexual attraction (what sex persons are sexually attracted to), sexual behavior (what sex persons have sex with, e.g., same-sex or opposite-sex sex partners), and sexual identity (what persons call themselves, e.g., “gay/homosexual”, “bisexual” or “straight/heterosexual”) [

2]. On this view, human sexuality is socially organized on a spectrum from heterosexual-identified persons who are attracted to and have sex with members of the opposite sex, on the one end, to homosexual-identified persons who are attracted to and have sex with members of the same sex, on the other end. The widely used Kinsey Scale, developed 75 years ago [

3], embeds this assumption of zero-sum sexual orientation by requiring that respondents who indicated greater same-sex attraction thereby simultaneously indicated lower opposite-sex attraction, on a one to seven scale ranging from “heterosexual” at one end to “homosexual” at the other. The expectation is that persons can be classified more or less coherently as homosexual, heterosexual, or something in between. This conception may stem in turn from the heteronormative idea that same-sex sexuality is but a mirror image of opposite-sex sexuality. Discordance directly challenges such a classification scheme [

4,

5].

Practically, many studies of sexual minority populations, and clinical intake processes, have not measured all three dimensions, but assumed that sexual orientation can be reliably inferred from only one or two dimensions. Studies of “men who have sex with men” (MSM) or “women who have sex with women” (WSW) often ignore the other two non-behavioral dimensions [

6]. Public health surveys frequently infer sexual orientation from identification alone [

7,

8]. Studies that classify persons as “bisexual” based on lifetime sexual experience with both men and women likely inadvertently include currently discordant persons in this category [

9]. Discordant persons, moreover, may not choose any of the three dimensions in favor of no response or “something else” [

10]. Such measurement does not accurately capture discordant sexual minorities, thereby underestimating the size and diversity of the sexual minority population, and potentially excluding the very group of persons who may be in most need of health interventions.

The recognition that individuals may experience discordance among two or more of the dimensions of sexual orientation, meaning that they may not be aligned in the same direction, has called these practices into question. Studies have shown that the three dimensions exhibit imperfect correlations and inconsistent predictability with one another [

11,

12] and that each dimension separately predicts differing health disparities [

5]. Therefore, measuring only one dimension without the inclusion or consideration of the others may lead to simplicities and reductionism in research and misclassification of treatment needs in clinical settings. The U.S. National Academy of Science has recently noted that sexual orientation measurement inaccuracies “are not purely academic: they can have severe consequences for sexual and gender minorities in health care and other areas in which measures of sex/gender and sexual orientation are often used for determining appropriate and necessary care” [

13].

Research on sexually discordant persons may help improve both theory and practice, and improve understanding of this doubly marginal population. A repeated finding, for example, is that rates of incongruity are higher among nonheterosexuals. Laumann et al. [

12] were among the first to report that, while these three dimensions were highly congruent for the heterosexual majority, this was not the case for the nonheterosexual minority. In their survey of a representative sample of the American population, they found that, of persons who experienced same-sex orientation on any one of the three dimensions, only 24% of males and 15% of females experienced it on all three dimensions [

12,

14]. Similarly, Geary et al. found in a British survey conducted 2010-2012 only 26% of nonheterosexual men and 14% of nonheterosexual women reported same-sex orientation on all three dimensions [

11].

Recent research has also shed light on fluidity of these three dimensions, emphasizing the dynamic nature of sexual orientation across the lifespan and its bidirectionality over time [

15,

16,

17,

18]. This statement appears particularly relevant to individuals who have ever encountered feelings of same-sex attraction. According to a study of sexual attraction change in four U.S. longitudinal studies, between 26% and 64% of people with same-sex attraction reported changing sexual attraction over time; between one-half and two-thirds of those who changed switched to heterosexuality, while a very small proportion (between 1% and 12%) switched from exclusive opposite-sex attraction to same-sex attraction [

1]. Another study conducted in a large sample of United Kingdom highlighted that the rate of sexual identity fluidity over a 6-year period is relatively low among those who previously self-identified as heterosexual (3.3%), higher among those who self-identified as gay/lesbian (16.1%) and particularly high among those with bisexual (56.8%) and other sexual identities (85.4%) [

19]. In addition, the fluidity of attraction is likely to be accompanied by increased instability of sexual behavior and partner sex. This is particularly evident for bisexual persons [

20], but it is not exclusive to them [

15]. Some authors even consider different types of attraction and behaviors seem to converge simultaneously in some people, mainly nonheterosexuals, and in a minority of heterosexuals referred to as discordant. These studies highlight that sexual attraction and behavior may be closely related to each other, and a change in one could lead to a change in the other.

By the same token, sexual identity stands somewhat over against both attraction and behavior. It is common to find greater discrepancies between identity and attraction and/or identity and behavior than between attraction and behavior [

11,

12]. Studies have also suggested that sexual identity could respond to factors other than attraction and behavior. As a developmental process of intentional self-identification that may be more susceptible to social influences and maturation processes, the relationship of sexual identification to fluidity in attraction and/or behavior is of special interest for understanding the establishment and stability of sexual minority identity. Therefore, the analysis of the mismatch between identity and the history of either attraction or behavior is of special interest.

Heterosexual Identity-Behavior Discordance (IDB)

While data constraints preclude the study of attraction history—no population survey (to our knowledge) has yet asked about past sexual attraction—with the recent appearance of national surveys that capture sexual partner histories by sex of partner, it has become possible to examine developmental questions of identity-behavior discordance (IBD). Due to the small size the nonheterosexual population, such data have mostly supported inferences about IBD in the heterosexual population, that is, persons who identify as heterosexual yet engage, or have engaged in the past, in same-sex sex.

In the last decade, several studies have reported the presence and size of this population. In the United States, the percentage of heterosexual-identified persons reporting a same-sex sexual partner was 10.2 in females and 2.6 in males. Very similar prevalence was obtained in Australia (10.9 in females and 3.7 in males). The lowest prevalence of behavioral discordance has been found in Canada, where 2.7 of females and 0.7 of males, respectively, reported it. The only study found among British population reported that 5.5% of men and 6.1% of women had had same-sex sex, and of these, the majority self-labeled as heterosexual [

11,

21]. Notably, studies have found that sexual IBD is especially prevalent among young adult women [

21,

22,

23]. Studies have also revealed that individuals classified as IBD reported lower levels of physical health and psychological well-being compared to concordant heterosexuals, and engaged in negative behaviors such as binge drinking, revealing the potential negative implications for general health associated with discordance.

Apart from sex, however, few studies explored associations between discordance and various demographic factors, and only limited research has examined the related development and health disparities of the heterosexual population who reported IBD. No study to date has yet examined the fluidity of heterosexual discordance, that is, how the type of sexual partner (male / female) may have changed over time among individuals self-identifying as heterosexual.

The reasons why a person becomes identity-behavior discordant may vary. For example, some authors speculated that heterosexual women are more likely than men to be discordant, possibly as a result of a more fluid sexuality that makes them more susceptible to same-sex behavior [

15]. Other authors argue that younger generations may show a greater propensity to engage in discordant sexual practices as a way of affirming their lack of interest in binary categories of opposite-sex or same-sex partners [

18,

24,

25]. This behavior may be the result of a cultural trend toward a greater acceptability of same-sex romantic behaviors today and the social invitation to self-discover one's sexual orientation. Additionally, alternative viewpoints propose that sexual discordance might be attributable to psychological factors, such as the presence of internalized homophobia. This approach suggests that nonheterosexual persons may conceal their authentic sexual orientation within a heteronormative environment in order to avoid stigma [

21,

26,

27]. As such, there could be multiple forms of discordance and probably different pathways to reach it, so classifying all individuals as identity-behavior discordant does not imply that they are all similar.

Among the conceptual frameworks identified to explain disparities in health issues between heterosexuals and nonheterosexuals, the minority stress theory is probably the most common. This model focuses specifically on sexual orientation-related stressors. It identifies distal stressors (e.g., social stigma, adverse childhood experiences) and proximal stressors (e.g., internalized homophobia, concealment of sexual orientation) that can lead to adverse health outcomes [

28]. Research on bisexual persons, who also suffer higher mental health disparities than other sexual minorities, has proposed that they may face added stigma due to “bisexual invisibility/erasure, experiences of bisexual-specific discrimination, biphobia in the gay community, and lack of support for bisexual sexuality” [

29]. IBD persons may face similar elevated stigma, including IBD-phobia in the gay community.

A second model widely recognized in the literature is the socioecological model. This framework emphasizes the role of social factors, such as socioeconomic status, education, employment, and access to healthcare, in shaping health outcomes. It suggests that sexual minority individuals may face distinct social disadvantages and inequities that contribute to disparities in health [

23]. Finally, recent genetic studies have pointed out that nonheterosexual persons share a genetic predisposition towards risky behaviors. A large genome-wide-association study (GWAS) by Ganna et al. [

30] found nonheterosexual sexual behavior was related to a genetic propensity for risk-taking behaviors related to sexual health. This study confirmed the findings of an earlier, smaller GWAS that had reported the same result [

31]. These frameworks are not mutually exclusive and often overlap, creating intricate intersections. All of them might offer diverse perspectives to researchers and practitioners in an attempt to explain the health disparities experienced by sexual minority individuals.

Objective

The present study aims to amend the gap in this emerging field of research by observing the fluidity of heterosexual IBD, that is, how the type of sexual partner (male / female) may have changed over time among individuals self-identified as heterosexuals, in an attempt to better describe this phenomenon, identify developmental pathways or subgroups, and examine related demographic and health disparities.

Analyzing representative data of the British population in 2010, the study aimed primarily to contribute new information regarding this population. Since the prevalence of individuals in these data who self-identified with any of the categories other than heterosexual (gay/lesbian, bisexual, or other) was low, we focused on the fluidity of identity-behavior discordance among heterosexuals, including the nonheterosexual group as a whole in the analyses for comparative purposes. In our study, we found that 2.8% self-identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual. The most recent nationally representative polling of the UK population showed that 3.1% of the population identified at lesbian, gay or bisexual [

32]. These data indicate little change in terms of prevalence since the Natsal-3 study was conducted to date.

We will begin presentation of the study’s findings by examining the prevalence of IBD in Britain according to sex. From this analysis, we will identify different groups of interest: those who identify as nonheterosexual; concordant heterosexuals; and three distinct profiles of discordant heterosexuals—closeted, experimenters and desisters. We then will compare and contrast these five groups on factors such as sociodemographic factors, attitudes toward sexuality and LGBT rights, multiple risk behaviors, and health status indicators in order to distinguish their unique profile.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive for the Sample

Characteristics of the population-representative sample are detailed in

Table 1 according to sex and sexual orientation. The majority of the participants were female (51%) and heterosexuals (97%). They were also mainly identified as white (89%) and married (52%). Almost half of them were studying or had completed higher education (46%) and did not declare any religious affiliation (48%). These proportions were very similar for both males and females. Compared to heterosexual participants, nonheterosexual participants were more likely to be younger, with a higher educational attainment unmarried, and religiously unaffiliated compared to heterosexual ones.

The prevalence of participants belonging to the five groups of analysis, stratified by sex, are detailed in

Table 2. Of the 12,472 participants who reported having had a sexual partner in the last 5 years, significantly differences (p< .001) by sex were reported by concordant heterosexuals (97% males vs. 96% females) and discordant heterosexuals (3% males vs. 4% females). Of the three groups of discordant heterosexuals, only experimenter discordants significantly differed respect to sex (1% vs. 2%, p< .001). No differences by sex were found with respect to sexual orientation (heterosexuals vs. nonheterosexuals, p = .694).

3.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics of All Analysis Groups

Table 3 presents weighted estimates of sociodemographic characteristics among the five analyzed groups. Among concordant heterosexuals, 51% were male, with a mean age of 42 years, 89% of white ethnicity, 47% obtained higher academic qualifications, most of them were married (55%), religiously affiliated (51%) and lived in urban area (76%). Nearly 17% of concordant heterosexuals reported religious attendance. Almost all (99.9%) reported an opposite-sex partner as the most recent live-in partner, and none reported same-sex partners in the past year.

Among the discordant heterosexual groups, closeted and experimenters were mostly females (61% and 63%, respectively), contrary to desisters (48%). The average ages ranged from 40 to 42 years. A great majority of participants of each group were white (92-95%), obtained higher academic qualifications (59%-62%) and lived in an urban area (72%-78%). Conversely to concordant heterosexuals, they were mostly unmarried (51%-69%) and didn´t report any religious affiliation (58%-69%). The attendance to religious services was low in all groups (8%-19%). Among closeted discordants, 9% reported having a same sex partner as the most recent live-in partner, and all of them reported having had a same-sex partner in the last year. Only 1% of experimenters reported a same sex partner as the most recent live-in partner, whereas none reported same-sex partners in the last year. Among desisters, none reported having had a same-sex either recently cohabiting or sexual in the past year

Nonheterosexuals constituted the youngest group (M = 36 years). Of them, 51% were female, 91% white, 89% lived in an urban area, and 58% obtained higher academic qualifications. They were more likely to be unmarried (75%). The proportion of nonheterosexuals with a religious affiliation was low at levels similar to closeted discordants (68% and 69%, respectively) and 89% reported low religious attendance. As for the sex of their recent partners, 55% reported having had a same-sex partner in their last cohabitation, and 65% reported having had one or more same-sex sexual partners in the last year.

Table 4 shows adjusted associations for demographic characteristics, comparing each IBD group and nonheterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals.

Group A: Closeted discordant heterosexuals

Compared to concordant heterosexuals, closeted discordant heterosexuals were nearly twice as likely to be female and older, up to three times more likely to have postsecondary education, and more than four times more likely to have further academic qualifications. They also were two-thirds less likely to be married and nearly half less likely to report a religious affiliation.

Group B: Experimenter discordant heterosexuals

Experimenter discordants, as compared to concordant heterosexuals, were more likely to be female, twice as likely to have had post-secondary education and more than three times as likely to have further academic qualifications. Also, they were one-third less likely to be married.

Group C: Desister discordant heterosexuals

Desister discordant heterosexuals were twice as likely to have further academic qualifications than concordant heterosexuals, whereas they were nearly half as likely to be married.

Group D: Nonheterosexuals

Nonheterosexuals were twice as likely to have further academic qualifications and an urban residence. They also were two-thirds less likely to be married and nearly half as likely to report a religious affiliation.

In summary, the closeted discordants and experimenters were more likely to be women. The experimenters were also younger. The nonheterosexual group was more likely to live in an urban area. All groups reported a higher likelihood of having more educational attainment, compared to the heterosexual closeted. In addition, all groups reported lower odds of being married, except the experimenters. Finally, all were less likely to belong to a religion.

3.3. Association between Attitudes and Behaviors and Each of the Five Groups of Interest

Table 5 overviews adjusted models for selected risk behaviors and attitudes, comparing each group of discordant heterosexuals and nonheterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals.

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for selected behaviors and attitudes, comparing identity/behavior discordant heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals. Britian, 2010 (N=12,472).

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for selected behaviors and attitudes, comparing identity/behavior discordant heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals. Britian, 2010 (N=12,472).

| |

C vs CH |

E vs CH |

D vs CH |

NH vs CH |

| |

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

| OPINIONS ABOUT SEXUALITY |

|

|

|

|

|

High pro-LGBT attitudes (ref=low) c

|

1.751

(0.9-3.3) |

1.29

(0.9-1.8) |

1.30

(0.9-1.9) |

5.43***

(4.0-7.4) |

|

Same sex sexual relations always wrong (refcat=non-heterosexuals) |

|

|

|

|

|

Same sex sexual relations never wrong (refcat=non-heterosexuals) |

|

|

|

1.0 (reference) |

|

Adultery rarely or never wrong (ref= mostly or always wrong) |

3.77*

(1.3-10.8) |

2.401

(1.0-6.0) |

3.81**

(1.5-9.7) |

2.45**

(1.3-4.8) |

|

One-night stand rarely or never wrong (ref = always wrong) |

1.22

(0.7-2.1) |

1.58*

(1.1-2.4) |

1.481

(1.0-2.3) |

1.35*

(1.0-1.7) |

|

Sex without love is OK; agree strongly (ref = else) |

1.62

(0.9-3.0) |

2.08***

(1.4-3.1) |

2.54***

(1.6-4.0) |

1.54

(1.1-2.1) |

| SEXUAL RISK BEHAVIORS |

|

|

|

|

| Linear trend in number of sex partners |

15.00***

(8.2-27.3) |

2.03***

(1.5-2.8) |

4.08***

(2.5-6.6) |

2.95***

(2.3-3.9) |

|

High STI risk (ref = low or none) |

4.91***

(2.4-10.0) |

0.62

(0.3-1.5) |

3.13**

(1.5-6.6) |

3.58***

(2.2-5.7) |

|

Ever paid for sex (ref = never) |

3.13*

(1.3-7.9) |

2.081

(0.9-5.0) |

7.75***

(4.4-13.8) |

1.48

(0.8-2.7) |

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for selected behaviors and attitudes, comparing identity/behavior discordant heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals. Britian, 2010 (N=12,472) (Cont.).

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) for selected behaviors and attitudes, comparing identity/behavior discordant heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals with concordant heterosexuals. Britian, 2010 (N=12,472) (Cont.).

| |

C vs CH |

E vs CH |

D vs CH |

NH vs CH |

| |

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

OR (95% CI) a

|

| SUBSTANCE USE |

|

|

|

|

|

Ever smoked tobacco (ref = never) |

2.14**

(1.3-3.6) |

3.02***

(2.1-4.4) |

2.20***

(1.5-3.3) |

1.59***

(1.2-2.1) |

|

Currently smokes tobacco (ref = no) |

2.29**

(1.3-4.0) |

1.83**

(1.3-2.6) |

1.431

(1.0-2.2) |

1.46**

(1.1-1.9) |

|

Chain smoker (10+ cigarettes/day) (ref = less than 10 or none) |

1.59

(0.8-3.2) |

1.71*

(1.0-2.8) |

1.44

(0.8-2.5) |

1.15

(0.8-1.7) |

Moderate/high weekly alcohol use

(ref = none/low) |

1.831

(1.0-3.4) |

1.63*

(1.0-2.6) |

1.95**

(1.2-3.1) |

1.60**

(1.2-2.2) |

|

Binge drinks weekly or more often (ref = less than weekly or none) |

1.99*

(1.1-3.7) |

1.32

(0.9-2.0) |

1.30

(0.8-2.1) |

0.96

(0.7-1.3) |

|

Smoked marijuana in the past year (ref = no) |

2.74**

(1.5-5.0) |

2.04**

(1.3-3.3) |

2.19**

(1.4-3.5) |

1.49*

(1.1-2.0) |

|

Used hard drugs in the past year (ref = no) |

4.14***

(2.1-8.3) |

3.48***

(2.0-6.1) |

2.91***

(1.7-4.9) |

3.86***

(2.7-5.5) |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL WELLBEING & ILLNESS |

|

Feeling depressed in the last 2 weeks

(ref = not at all) |

1.08

(0.6-2.1) |

0.97

(0.6-1.7) |

1.28

(0.8-2.2) |

2.20**

(1.6-3.1) |

|

Screened positive for current depression (ref = screened negative) |

0.86

(0.5-1.6) |

1.04

(0.6-1.7) |

1.11

(0.7-1.9) |

1.75**

(1.3-2.5) |

|

Currently taking medication for depression (ref = no) |

1.41

(0.7-2.8) |

2.49***

(1.6-3.9) |

1.57

(0.8-3.0) |

2.52***

(1.8-3.6) |

Feeling apathy in the last 2 weeks

(ref = not at all) |

0.97

(0.5-1.9) |

1.02

(0.6-1.8) |

1.01

(0.6-1.8) |

1.62**

(1.1-2.3) |

|

Has serious physical health infirmity (ref = no) |

0.65

(0.3-1.5) |

1.13

(0.7-1.8) |

1.581

(1.0-2.6) |

1.51*

(1.0-2.3) |

|

Has longstanding limiting illness or disability (ref = non-limiting or none) |

0.89

(0.5-1.8) |

1.52*

(1.0-2.3) |

1.531

(0.9-2.5) |

2.52***

(1.9-3.4) |

Excludes participants who reported no sexual partners in the last 5 years (N = 2,690). Asterisks report p-value of t-test that OR is not equal to 1:1 p < .1; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference; CH, Concordant Heterosexual; C, Closeted, E, Experimenter; D, Desister; NH, Nonheterosexual. a Adjusted for sociodemographic factors: age, sex, residence area, ethnic identity, academic qualifications, civil marital status, and religious affiliation.Excludes participants who reported no sexual partners in the last 5 years (N = 2,690). Asterisks report p-value of t-test that OR is not equal to 1:1 p < .1; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001. Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference; CH, Concordant Heterosexual; C, Closeted, E, Experimenter; D, Desister; NH, Nonheterosexual. a Adjusted for sociodemographic factors: age, sex, residence area, ethnic identity, academic qualifications, civil marital status, and religious affiliation. c A single measure of pro-LGBT attitudes was created. obtaining the mean score of the four attitudes. Internal consistency was very good (Cronbach alpha = .90). This variable was dichotomized by the median to create high and low groups.Opinions about sexuality and LGBT rights

Compared to concordant heterosexuals, nonheterosexuals were 5.4 times more likely to support pro-LGBT attitudes in favor of same-sex relationships and adoption rights. Closeted heterosexuals, at 1.8 times more likely to support pro-LGBT attitudes, were significantly higher than concordant heterosexuals at the .10 critical level, but not at .05. Experimenters and desisters were no more likely than were concordant heterosexuals to express pro-LGBT attitudes. Closeted and desisters were more likely to report that "adultery is rarely or never wrong" while experimenters and nonheterosexuals were more likely to report that "one-night stands is rarely or never wrong". Lastly, experimenters and desisters strongly agreed that sex without love is okay.

Sexual risk behaviors

All groups reported a higher number of sexual partners compared to the heterosexual matched, but undoubtedly, the closeted group reported a much higher number of sexual partners than the rest.

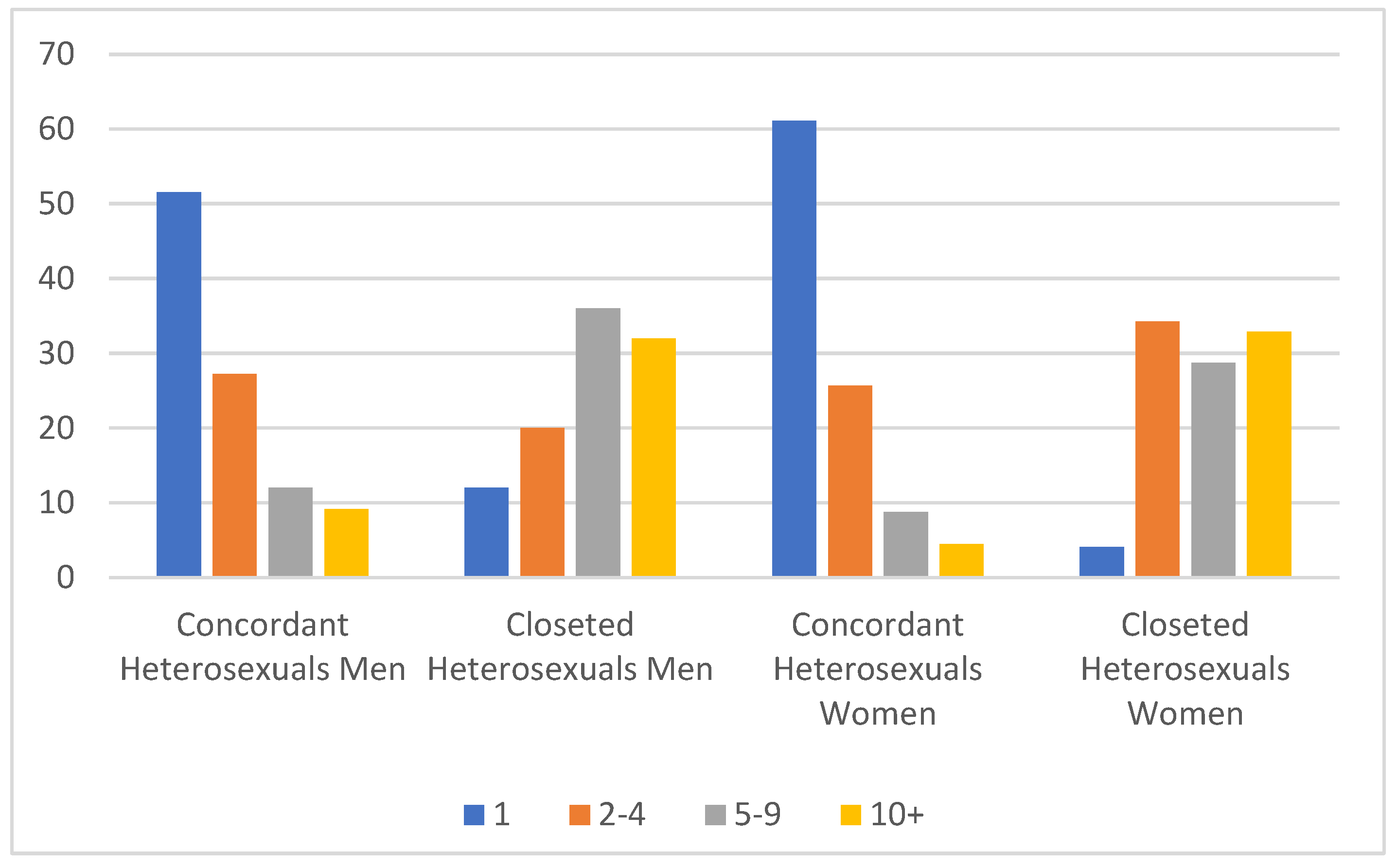

Figure 1 displays the number of sexual partners in the last 5 years of closeted heterosexuals and concordant heterosexuals, by sex. As it can be seen, the evolution of the number of partners for both groups is inversely proportional. Among concordants, the higher the number of partners, the lower the proportion of heterosexual concordants. The opposite occurs among closeted discordants. Both trends are very similar among men and women.

On the other hand, the reported risk of STI was significantly higher among the closeted, the desisters and the nonheterosexuals. Only the closeted and desisters were more likely to ever having paid for sex.

Substance use

Overall, all groups reported higher likelihood of substance use (tobacco, alcohol, binge drinking, marijuana, and hard drugs) compared to concordant heterosexuals. The highest ORs were found for using hard drugs in the past year for all groups. Only experimenter group reported higher risk of being a chain smoker, and closeted of weekly binge drinking.

Psychological wellbeing and illness

Among IBD discordants, only the experimenter group was more likelihood of currently taking medication for depression, and having a longstanding limiting illness or disability. Not surprisingly, the studied indicators of psychological wellbeing (i.e. depression, apathy) and physical health (i.e. physical infirmity, limiting illness or disability) were much more common among nonheterosexual persons than the rest of groups.

Tolerance Analysis

As noted above, despite their exposure to same-sex behavior, none of the IBD groups expressed more support for same-sex relationships and adoptions than did concordant heterosexuals, although the closeted group came close. To address the possibility of IBD homophobia, we examined the extreme responses to the questions asking the respondents view whether same-sex sexual relations between adults were right or wrong. The possible responses were always wrong, mostly wrong, sometimes wrong, rarely wrong, and not wrong at all. “Always wrong” expressed the most intolerant response; “not wrong at all” the most tolerant response.

Table 6 reports the odds on the most tolerant and most intolerant response for all four heterosexual groups–concordant heterosexuals and the three IBD groups–compared to nonheterosexuals.

As

Table 6 reports, all heterosexual groups, including all three IBD groups, were significantly less likely than were nonheterosexuals to report high tolerance of same-sex sexual relations, with ORs ranging from .19 to .33. On the other hand, while concordant heterosexuals were 6.3 times more likely to express high intolerance of same-sex sexual relations, none of the discordant heterosexual groups expressed higher intolerance than did nonheterosexuals. The lack of support for pro-LGBT attitudes among IBD heterosexuals is not linked to high intolerance of same-sex sexual behavior consistent with possible homophobia, as is the case among concordant heterosexuals.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the lifetime fluidity of discordance among currently-identified heterosexual persons. The results reveal three distinct IBD patterns among such persons, who differ markedly from one another on indicators of health status, risk behaviors and attitudes toward sexuality.

Our results confirm numerous previous findings that sexual fluidity was higher among women [

1,

17,

36,

37]. Many studies have identified this phenomenon as true among homosexuals. For example, Vrangalova and Savin-Williams [

25] found that men tended to give more consistent responses to their sexual orientation than women. Ott et al. [

37] found that women reported higher mobility scores regarding sexual orientation identity than men. Findings from a recent longitudinal study of U.S. adults demonstrated that women and nonheterosexuals reported a more fluid sexual identity than heterosexual men [

38]. Our study adds to the few who have extended this finding also to heterosexuals, finding that 4.3% of heterosexual women, compared to 3.0% of heterosexual men, experienced IBD. These higher rates of IBD among heterosexual women than in heterosexual men are also consistent with those found in prior studies [

21,

22,

23].

The origin of these sex disparities, as pointed out by Diamond [

16], remain uncertain and could be related to sexual minority status. While changes can manifest in either direction, there tends to be greater stability among those who self-identify as heterosexual compared to those who identify as mostly heterosexual or bisexual [

37,

38,

39]. Large longitudinal studies have also shown these changes are more often oriented toward heterosexuality than homosexuality [

1]. In line with previous studios, our investigation demonstrates that incongruities and fluidity of the sexual orientation are more prevalent among women, and emphasizes that these aspects are not restricted solely to sexual minority groups.

IBD discordance: closeted, experimenters, and desisters.

When considering the three heterosexual IBD groups collectively in comparison to the nonheterosexual group, several notable similarities and dissimilarities emerge. The heterosexual IDB groups tended to share with nonheterosexuals more secular and less moralistic characteristics than the general heterosexual population: more advanced education, lower participation in marriage and religion, and higher support for adultery and one-night stands. The discordant heterosexuals were also not more negatively proscriptive of same-sex sexual relations than were nonheterosexuals, but at the same time not more positively affirming of them than were concordant heterosexuals. Like nonheterosexuals, all heterosexual IBD groups also reported higher lifetime sex partners than did concordant heterosexuals, and were also more prone to substance abuse, including present and past smoking, and the use of alcohol, marijuana and hard drugs. Nonheterosexuals, however, were more likely to reside in urban areas, to be more supportive of same-sex relationships and adoption rights, and were more susceptible to feelings of depression and apathy than were the heterosexual IBD groups. Each IBD group also presents a unique set of characteristics relative to concordant heterosexuals, compared to other IBD groups and to the nonheterosexual group.

Experimenters

Experimenters, who had had only a single same-sex sexual partner more than a year ago and only heterosexual partner(s) in the past year, reported the least risky sexual behavior–the fewest sex partners, lowest STI risk, and least recourse to prostitution–among the three IBD groups. Like the other IBD groups, experimenters reported more accepting attitudes toward one-night stands and adultery, but also toward loveless sex. Like the closeted, the experimenter group was more female, and experimenters were the only IBD group that was significantly more likely to be of white race or ethnicity, than concordant heterosexuals.

Experimenters had similar levels of psychological and physical well-being as the concordant heterosexual population on most measures, but were more likely to have a limiting illness/disability or to be taking medication for depression. Experimenters also did not differ from concordant heterosexuals in terms of their pro-LGBT attitudes or other variables such as marital status, age, and area of residence. However, the experimenters were more similar to the nonheterosexual group, in contrast to concordant heterosexuals, with respect to their higher educational level, substance abuse, low religious affiliation, and support for one-night stands and adultery.

Closeted

Closeted IBD heterosexuals, who reported ongoing same-sex sexual encounters often contiguous with heterosexual partnerships, stand out for both their elevated number of sexual partners in the past five years and their increased risk for STIs. Closeted heterosexuals reported 15 times more sex partners and almost five times higher STI risk, on average, than did concordant heterosexuals. This is in stark contrast to patterns observed in the heterosexual population, and substantially higher than among nonheterosexuals, experimenters or desisters.

Like experimenters, closeted IBD heterosexuals were more female than either desisters or nonheterosexuals. The preponderance of women among experimenters and closeted IBDs may suggest that, as a form of sex-exploration, women may more frequently engage in sexual activities with same-sex partners without leading them to question their heterosexual identity. Heterosexual identification despite continued same-sex activity may be due to the avoidance of stigma, however in this case one might have expected a higher proportion of males relative to females among the closeted, given that males tend to report greater social stigma [

40], and higher levels of internalized homonegativity [

41].

Closeted heterosexuals are similar to concordant heterosexuals in terms of ethnicity, urban residence, levels of psychological well-being and illness, and sexual attitudes except for adultery. Conversely, they are more similar to the nonheterosexual group in reporting higher academic qualifications, low religious affiliation, being unmarried, and higher substance use. Of the IBD groups, the closeted had the highest support for same-sex relationships and the adoption of children by gays and lesbians, significantly different from concordant heterosexuals at the .10 critical level, but still less than half as high as nonheterosexuals.

Desisters

Desisters, who reported significant past same-sex sexual behavior but none in the past year, were the most similar to concordant heterosexuals of the three heterosexual IBD groups. Desisters generally matched concordant heterosexuals demographically, in terms of sex, age, ethnicity, religious affiliation and area of residence. Their psychological profile was similar to concordant heterosexuals, and like them they did not report high pro-LGBT attitudes. Unlike concordant heterosexuals and like nonheterosexuals, however, desisters reported higher acceptance of loveless sex, one-night stands and adultery, and higher substance use and risky sexual behaviors.

Unlike experimenters and closeted, desisters were not more likely to be female. In addition, they were the group most likely to have ever paid for sex, consistent with their greater male composition.

Nonheterosexual group

Some of the most striking findings of this study were those related to the nonheterosexual group. In terms of prevalence, we found similar rates between males and females, ranging from 2-3%. These proportions are similar to those reported by U.K. Census 2021, according to which, the proportion of the UK population aged 16 years and over identifying as lesbian gay or bisexual (LGB) in 2020 was 3.1% [

32]. This survey collected information about sexual orientation using a question designed to capture sexual identity comparable to the one in this study.

Nonheterosexuals reported much more strongly favorable attitudes toward same-sex relationships and the adoption of children by gays and lesbians than did heterosexual IBDs. Closeted heterosexuals, who currently engaged in same-sex behavior, were more supportive of these pro-LGBT attitudes than were experimenters or desisters, who had ceased doing so; but none of the heterosexual IBD groups were even half as likely to support them as the nonheterosexuals were. The absence of negative judgment of same-sex behavior among heterosexual IBDs argues against a simplistic attribution of these differences to homophobia, or to homophobia alone. Rather, these facts emphasize the close correlation between opinions and self-identification, suggesting that adopting a sexual identity may not be not simply a way of viewing oneself, but also a way of viewing the cultural and political world in which one lives. We have already suggested above that sexual attraction and sexual behavior might share underlying mechanisms that could be distinct from those shared by self-identification and opinions.

With some exceptions, nonheterosexual individuals also reported worse physical and psychological health than heterosexual IBDs. Compared to concordant heterosexuals, experimenters were as likely as nonheterosexuals to be on depression medication, desisters were as likely to have a physical infirmity, and both experimenters and desisters were at elevated but lower risk of a limiting illness or disability. This finding extends abundant previous research which has found homosexual individuals to be at higher risk of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation compared to their heterosexual counterparts [

2,

42,

43]. Our data do not allow us to know the reasons for which these persons reported poorer health, but they do highlight that the nonheterosexual population is more vulnerable to health problems than heterosexuals, discordant or concordant. Many studies corroborate that sexual minority individuals may experience a disproportionately higher prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), increasing their exposure to multiple developmental risk factors that have systemic negative health effects across the lifespan [

44]. Supporting this explanation, our results also showed higher substance use and sexual risk behaviors of this group compared to heterosexual concordants.

According to the Minority Stress Theory, "concealment" refers to the practice of hiding or suppressing one's sexual minority identity in order to avoid potential negative effects of stressors such as discrimination or stigma [

45]. While concealment may provide some short-term relief from stressors, it can also lead to additional stress in the long-term, as it requires continuous effort to maintain the concealment and may result in a lack of authenticity in one's interactions and relationships [

46]. On this theory, we would expect to have found worse health indicators among heterosexual discordants, particularly among those categorized as closeted. On the contrary, we found that discordant heterosexuals did not present greater psychological and physical problems than concordant heterosexuals, subject to the few exceptions already noted, none of which included the closeted. It is possible that the identity reported in the study was different than that publicly expressed by the participants, or that IBD health decreases over time due to concealment. Future research could explore these possibilities further.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, due to the large number of outcomes studied in Natsal-3, only the variables considered to be of greatest interest for our study were selected. Other relevant variables may have been left unexplored. Small group sizes prevented us from exploring many theoretically important covariates or associations of heterosexual IBD, such as race and sex, and from examining IBD among nonheterosexuals. As in any cross-sectional observational study, causal relationships between the factors studied could not be determined from the data.