Background

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is a fundamental human right essential for mental well-being and overall health (Khosla et al., 2015). The Australian National Men’s Health Strategy 2020-2030 states that SRH is a priority issue needing significant commitment and careful planning of health initiatives and services (Department of Health, 2019). However, SRH research and program development among men in Australia largely focuses on sexually transmitted infections and fertility, meaning other areas of men’s SRH are overlooked (Daumler et al., 2016; Mengesha et al., 2023). For instance, sexual dysfunction, which includes diminished sexual desire or sexual pleasure, erection and orgasm difficulties, and premature ejaculation (WHO, 2015), is prevalent in the Australian population (Schlichthorst et al., 2016). The Australian Study of Health and Relationships found that approximately half of Australian men reported experiencing at least one sexual dysfunction, with lack of interest in sex (28%) and premature ejaculation (21%) being the most frequently cited concerns (Richters et al., 2022). Differences in sexual dysfunction among men correlate with health factors, such as poor self-rated health, disability, and mental health conditions, as well as lifestyle choices, including smoking, harmful alcohol consumption, and drug use (Schlichthorst et al., 2016). This implies that addressing men’s sexual dysfunction requires a comprehensive approach that considers both the physical and mental health, and lifestyle aspects of men’s lives (Avasthi et al., 2017).

Sexual dysfunction can significantly impact men’s physical health, mental well-being, and quality of life (Wagner et al., 2000). For example, erectile dysfunction has been found to contribute to reduced sexual satisfaction (Sheng, 2021). Higher number of sexual dysfunction is linked to psychological distress (Lafortune et al., 2023), including depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Mota et al., 2019). Left untreated, these mental health conditions can exacerbate the problem, further inhibiting sexual function and creating a cycle of distress (Xiao et al., 2023). Additionally, unresolved sexual problems may strain intimate relationships leading to communication breakdowns, feelings of inadequacy and relationship breakdowns (Heiman, 2002). Sexual dysfunction can also negatively impact overall life satisfaction (Lu et al., 2020) and hinder participation in professional activities posing a substantial economic burden on employers (Elterman et al., 2021). This suggests that addressing sexual dysfunction through timely intervention and support is crucial for promoting men’s SRH health and well-being and improving quality of life (McCabe & Althof, 2014).

Despite the high prevalence of sexual dysfunctions, a significant reluctance among men to seek healthcare professional help persists, making sexual dysfunction an under-reported and under-treated health condition (Moreira et al., 2005). Analysis from Britain’s third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles found that fewer than half of male respondents experiencing distressing sexual difficulties sought sexual help (Hobbs et al., 2019). Stigma surrounding the discussion of sexual health difficulties and masculine norms contribute to this reluctance to access support (Sever & Vowels, 2024). Furthermore, many men may also feel embarrassed or ashamed to address intimate concerns, leading them to suffer in silence rather than seek assistance from healthcare professionals (Latreille et al., 2014). Men also face structural barriers to accessing healthcare such as prolonged waiting times and high cost of sexual health services (Lafortune et al., 2023). For instance, consultations with a sex therapist or attending couples counselling is often not bulk billed in Australia as these services are not covered by Medicare, creating a financial barrier to access for many individuals (Sever & Vowels, 2024).

Existing research into sexual dysfunction among men in Australia is frequently confined to cross-sectional studies (Schlichthorst et al., 2016), which poses challenges in comprehending its longitudinal burden. While some research has explored provider perceptions on challenges men encounter in accessing sexual health services (Collyer et al., 2018), few published data investigate sexual help-seeking behaviour by men and its determinants (Smith et al., 2013). Drawing on data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health (Ten to Men), the present study aims to address this gap by analysing longitudinal trends in sexual dysfunction rates, common avenues for seeking help, and factors associated with sexual help-seeking behaviour. Understanding factors associated with sexual help seeking behaviour is essential for enhancing equitable access to sexual healthcare, reducing potential stigma, promoting early intervention, and developing programs aimed at improving men’s SRH and psychological wellbeing (Shand & Marcell, 2021).

Methods

Data Source and Participants

This analysis is based on data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health (Ten to Men), a large cohort study of Australian men aged 10-55 at baseline. As described by Currier et al. (2016), a stratified, multi-stage, random cluster sampling technique was used to examine six key areas of male health: wellbeing and mental health, use of health services, health-related behaviours, health status, health knowledge and social determinants. Field workers recruited participants from households in each of the chosen areas if they were males aged 10 to 55, Australian citizens and permanent residents, and had sufficient English language to complete a self-administered survey questionnaire. Our paper uses the longitudinal data of adult men (age 18+) across waves 1 (2013-2014), 2 (2015-2016), 3 (2020) and 4 (2022). The variables of interest were sexual dysfunction, help seeking behaviour and its determinants. Only men who had ever engaged in vaginal, oral or anal sex were included in our analysis leaving a total sample of 12,737 (wave 1), 8,933 (wave 2), 6,991 (wave 3) and 5,804 (wave 4) men.

Variables and Measurement

The key variables of interest in our study were sexual function and sexual help seeking behaviour. In the Ten to Men data, sexual function was assessed using the validated National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Mercer et al., 2005). The measure comprises eight constructs: lacking interest in having sex, lacking enjoyment in sex, feeling anxious during sex, feeling physical pain because of sex, feeling no excitement or arousal during sex, not being able to reach climax or taking too long, reaching climax too quickly, having difficulties getting or keeping an erection. Having a binary (yes/no) response options, all sexually active men were asked if they had experienced any of the sexual difficulties for at least three months in the 12 months prior to the study. Sexual help seeking was measured by asking all sexually active men if they had sought help for sexual health issues from a sexual health clinic, self-help groups, self-help books, relationship counsellor, psychiatrist or psychologist, internet, helpline, other type of clinic or doctor, general practitioner (GP)/family doctor, family member/friend. Response options to these questions were binary yes/no.

Our study controlled for a range of independent variables which were believed to affect men’s sexual help seeking behaviour in the wider literature. These included sociodemographic and economic factors (age, level of education, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status, employment status, area level of disadvantage, sexual identity, relationship status, financial hardship, private health insurance), health conditions (disability, self-rated general health, depression), geographical factors (Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) region), and behavioural factors (health literacy, conformity to masculine norms).

Conformity to masculine norms: Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI)(Mahalik et al., 2003) was used to measure the degree of conformity to traditional masculine roles. It is comprised of 22 items that capture notions of winning, emotional control, risk taking, violence, dominance, sex, self-reliance, primacy of work, power over women, homosexuality, and pursuit of status with a four-point scale response option: 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = agree, and 3 = strongly agree. The scores for each item were summed to produce a total CMNI score, which ranges from 0 to 66, with higher scores indicating greater conformity to masculine norms. The CMNI score is divided into low conformity, middle conformity, and high conformity according to the quantile. CMNI scores were collected at wave 1 and wave 3 for men who were not asked at wave 1 and used as a time-invariant variable at Waves 2 and 4.

Severity of depression: A nine item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)(Kroenke et al., 2001) was used to assess depression among the Ten to Men participants. The questionnaire scores each of the nine symptoms on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with the sum of the scores determining the presence and severity of depression. We considered a PHQ-9 score of 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-19 and 20 or more to indicate no/minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

Health literacy: All participants of the Ten to Men study completed a three-scale Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) (Osborne et al., 2013): ability to find good health information; ability to actively engage with healthcare providers; and feeling understood and supported by healthcare providers (collected only at wave 2). The HLQ comprises several sub-scales that examine the full construct of health literacy with five response options for each item: 0 = ‘cannot do’, 1 = ‘very difficult’, 2 = ‘quite difficult’, 3 = ‘easy’, and 4 = ‘very easy’. A score ranging 0-20 was generated for each participant to fit health literacy variable in the regression model.

CALD: The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) defines CALD as a person who is Non-Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and speaks a language other than English at home (ABS, 2022). Core variables of CALD standards by the ABS were used to identify CALD men in the Ten to Men study. CALD status was collected at wave 1 and used as a time-invariant variable for waves 2, 3 and 4.

Financial hardships: Was assessed using 5 (waves 3 and 4) or 6 (waves 1 and 2) binary (no/yes) items, including could not fill/collect prescription, could not get medical care, could not pay bills on time, could not pay mortgage/rent on time, asked for financial help from others, and/or limited availability fruit and vegetables.

Statistical Analysis

All data management and statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17 software. Background characteristics of the study participants in each wave were summarised using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviations for continuous variables. The summary statistics for sexual dysfunction and sexual health seeking behaviour was compared between CALD and non-CALD men, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) used to assess the statistical significance of differences across waves. To adjust for non-proportional sampling and non-response rates and obtain robust statistical estimates, data were weighted using the survey estimation commands in Stata (svyset command). In the svyset command, wave specific ranked cross-sectional population weight, Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) code, and Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) region were used as variables representing the primary sampling unit (PSU), sampling weight, and strata, respectively.

We used logistic regression to investigate potential factors associated with sexual health-seeking behaviours. To select potential variables, we first conducted bivariate logistic regression (unadjusted regression) for each independent variable in each wave. Then, variables with a p-value ≤ 0.2 in bivariate analysis were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model. In multivariate logistic regression, the association between each independent variable and sexual health seeking behaviour was reported using adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs.

Results

Background Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 below presents the background characteristics of the study participants included in the analysis. The distribution of variables was similar across the waves except for age, private insurance, marital status, and number of financial hardships experienced. The proportion of men aged 55 years and over has been increased from 2.1% in 2013/14 to 31.4% in 2022. Similarly, the proportion of men with private health insurance increased from 54.5% in 2013/14 to 80.9% in 2022. In 2013/14, more than one in ten men (11.9%) had experienced three or more financial hardships, while this figure decreased to 3.5% in 2022. Most men (82.7% in 2013/14, 82.5% in 2015/16, 81.3% in 2020 and 80.7% in 2022) had moderate conformity to masculine norms.

Trends in Sexual Dysfunction

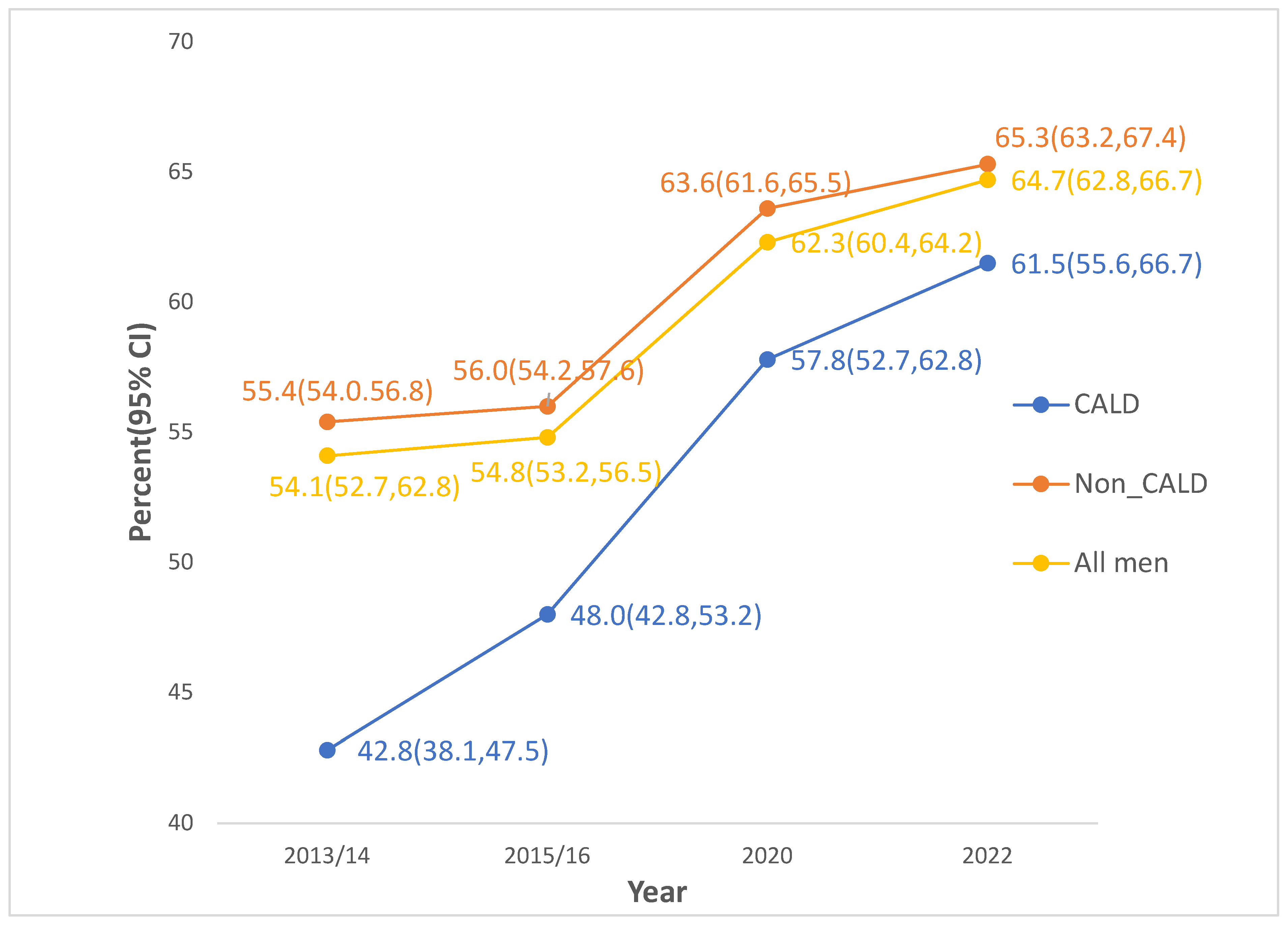

As shown in

Figure 1, the prevalence of at least one sexual difficulty increased significantly, from 54.1% (95% CI: 52.7, 62.8) in 2013/14 to 64.7% (95% CI: 62.8, 66.7) in 2022. The increase was most pronounced among CALD men, from 42.8% (95% CI: 38.1, 47.5) in 2013/14 to 61.5% (95% CI: 55.6, 67.1) in 2022. It is also apparent from

Table 2 that the prevalence of each type of sexual dysfunction increased significantly between 2013/14 and 2022. Reaching climax too early was the most common form of sexual dysfunction in all waves (36.2%, 95% CI: 34.8,37.5 in 2013/14, 36.9%, 95% CI: 35.2,38.5 in 2015/16, 40.1%, 95% CI: 38.3,41.9 in 2020 and 41.0%, 95% CI: 38.9,43.1 in 2022), followed by lacked interest in having sex (17.5%, 95% CI: 16.4,18.6 in 2013/14, 17.7%, 95% CI: 16.5, 19.0 in 2015/16, 24.2%, 95% CI: 22.6, 25.8 in 2020 and 25.4%, 95% CI: 23.6,27.4 in 2022). On average men reported having 1.12 sexual dysfunctions (mean = 1.12; 95 % CI: 1.08–1.17) in 2013/14 and 1.51 (mean=1.51, 95% CI: 1.44,1.58) in 2022.

Trends of Sexual Help Seeking Behaviour in Australian Men

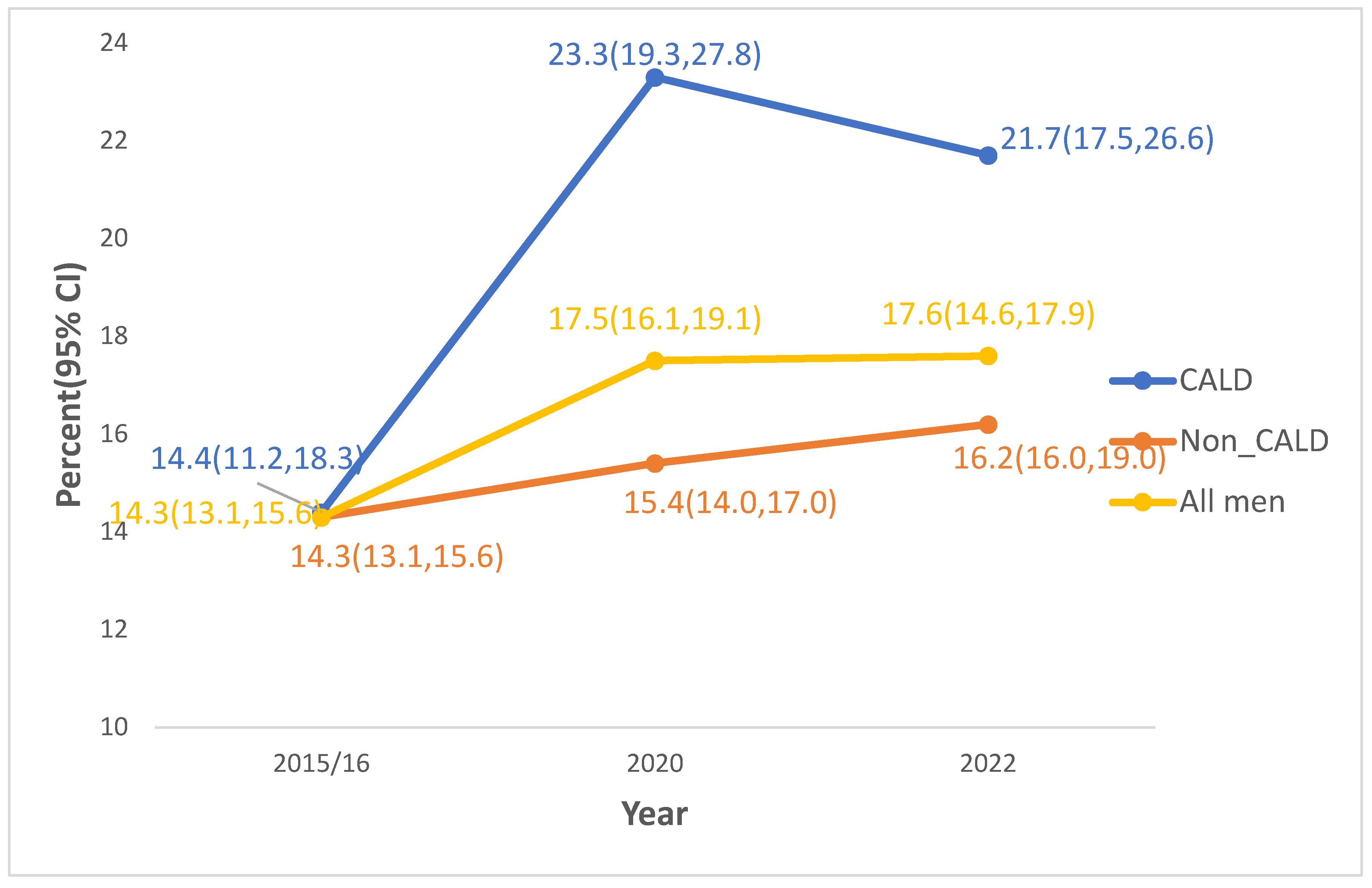

Sexual help seeking behaviour of Australian men remained low over the study period, although there was a significant improvement from 14.3% (95% CI: 13.1, 15.6) in 2015/16 to 17.6% (95% CI: 14.6, 17.9) in 2022. Sexual health seeking behaviour among CALD men also improved significantly from 14.4% (95% CI: 11.2, 18.3) in 2015/16 to 23.3% (95% CI: 19.3, 27.8) in 2020 but declined between 2020 and 2022 (

Figure 2).

Sources of Help for Sexual Health

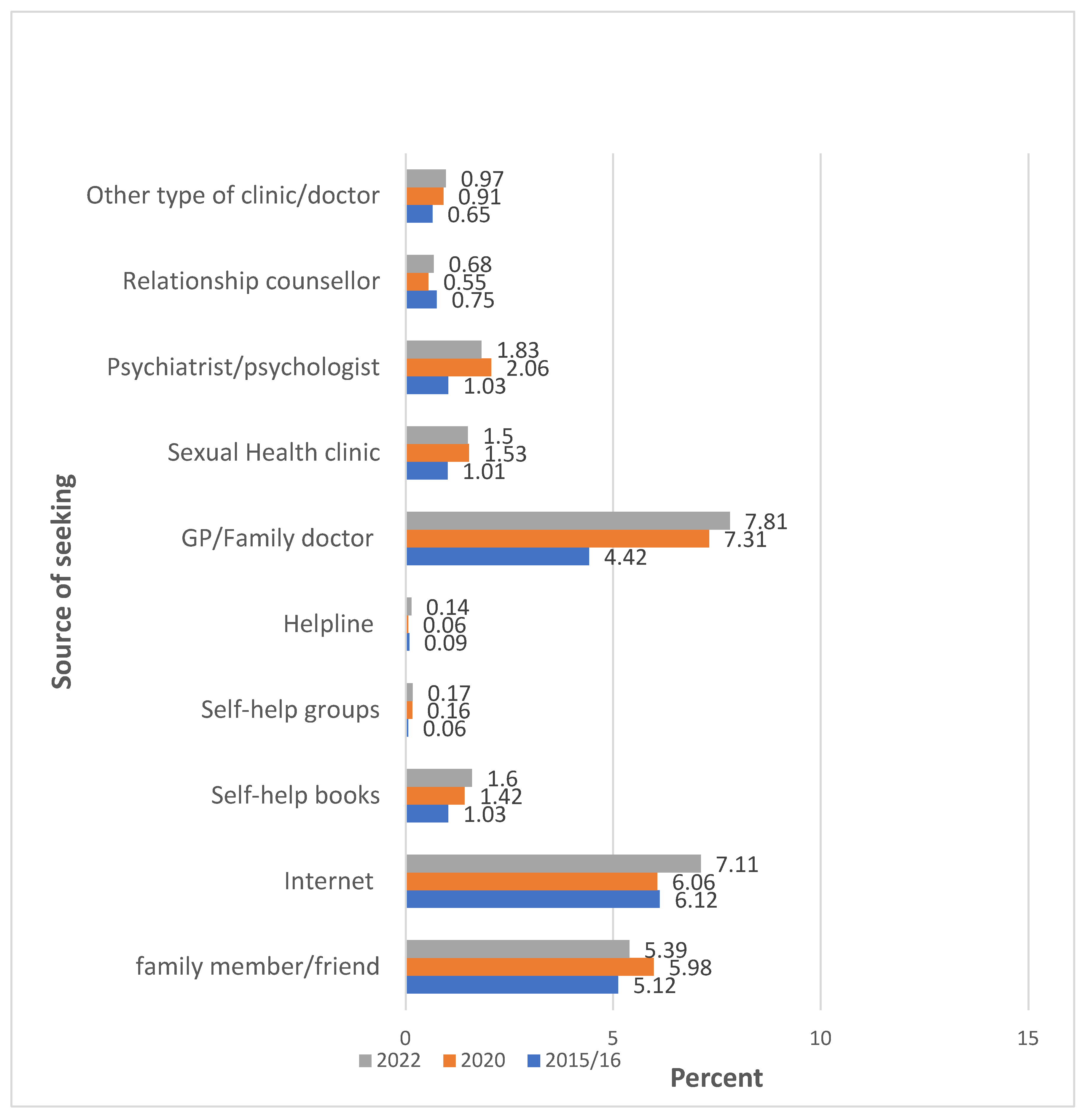

In 2020 and 2022, the most reported source of help was a general practitioner/family doctor (7.81% and 7.31%, respectively), followed by seeking information and support via the internet (7.11% and 6.06%, respectively). In 2015/16, the most common source of help/advice was the Internet (6.12%), followed by family or friends (5.12%) (

Figure 3).

Factors Associated with Sexual Help Seeking Behaviour

The results from the estimation of the logistic regression model, as shown in

Table 3, indicate that after adjusting for potential confounders, the number of sexual difficulties, age, sexual identity, relationship status, conformity to masculine norms, depression, and the number of financial hardships were significantly associated with sexual health-seeking behaviour. Specifically, the number of sexual difficulties experienced, and age were significantly associated with sexual health-seeking behaviour in all waves.

In our estimation, number of sexual difficulties experienced had the largest effect on health seeking behaviour in terms of magnitude. For example, the odds of seeking sexual health services in 2020 were 6.37 (AOR=6.37, 95% CI: 4.48, 9.03) times higher for those who had three or more sexual difficulties compared to those who did not have any difficulties. The corresponding adjusted odds-ratios for 2015/16 and 2022 were 4.85 (AOR=4.85, 95% CI: 3.67, 6.41) and 4.75 (AOR=4.75, 95% CI: 3.36, 6.73), respectively. Moreover, the results indicate younger men in the 18 – 24 age category were more likely to seek help for sexual difficulties than men in older age groups. For example, the odds of sexual health seeking among men aged 45 – 54 was lower by 50% (AOR=0.50, 95% CI: 0.35, 0.73) in 2015/16, 64% (AOR=0.36, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.67) in 2020 and 52% (AOR=0.48, 95% CI: 0.24, 0.97) in 2022 compared to men aged 18- 24 years. Our results found that bisexual and gay men also had higher odds of seeking sexual health services than heterosexual men. Bisexual men had 1.86 (AOR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.14, 3.02) and 2.02 (AOR=2.02, 95% CI: 1.18, 3.48) times higher odds of sexual health seeking than heterosexual men in 2020 and 2022, respectively. The odds of sexual health seeking among gay men was higher by a factor of 3.66 (AOR=3.66, 95% CI: 2.08, 6.44) compared to heterosexual men in 2022.

Similarly, the results indicate higher odds of accessing sexual health services for men who experienced one, two, and three or more financial difficulties compared to those who did not experience any financial hardship. We also found that men in a married or de-facto relationship had lower odds of seeking sexual health services compared to those who were single/separated/widowed/divorced (significant only in 2015/16). Lastly, other factors which significantly increased the likelihood that men sought help included moderate depression (significant in 2015/16), disability (significant in 2020) and high conformity to masculine norms (significant in 2022).

Discussion

Using data from the Ten to Men study, we examined the longitudinal burden of sexual difficulties, common sources for seeking help, and factors associated with sexual help seeking behaviour among a cohort of Australian men. Our findings indicate a significant rise in the prevalence of experiencing at least one sexual difficulty among all men, increasing from 54.1% in 2013/14 to 64.7% in 2022. This trend may be attributed to the increasing age of the study population, with the proportion of those over 55 years old rising from 2.1% to 31.3% over the study period. Comparing the results with previous studies reveals similar trends in the prevalence of sexual difficulties. For example, a study by Lewis et al. (2004) found a comparable increase in sexual dysfunction rates among men in Western countries, pointing to aging populations, lifestyle changes, and increased awareness and reporting of sexual health concerns as contributing factors. Particularly notable increases were observed among men from CALD backgrounds, increasing from 42.8% in 2013/14 to 61.5% in 2022. This trend aligns with studies that highlight disparities in sexual health outcomes among diverse populations (Mengesha et al., 2023). It underscores the growing impact of sexual health concerns on men’s well-being and highlights the importance of addressing them as a public health priority.

Despite the high prevalence of sexual difficulties among Australian men, we found only about one-fifth sought sexual health assistance. There was also no significant longitudinal changes over the study period despite increasing rates of sexual dysfunction. Sever and Vowels (2023) explained that psychological barriers such as embarrassment, shame, and stigma, lack of awareness around where to find sex therapy, and a perception that sexual concerns are not severe health problems hinder the utilisation of sexual health services. In Australia, specialised sex therapies and counselling is mostly not covered by Medicare, which disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, including CALD men (Mengesha et al., 2023), highlighting the need for policy reforms to ensure equitable access to sexual health services (Sever & Vowels, 2024). This is particularly critical given that Australia’s Men’s Health Strategy 2020-2030 has identified CALD men as a priority population and SRH as a priority area for intervention to enhance men’s health and wellbeing outcomes (Department of Health, 2019).

The finding that general practitioners (GPs), the internet, and family members are the most reported sources of help for addressing sexual health concerns has significant implications. It underscores the crucial role of GPs in providing accessible and reliable sexual health services, highlighting the need for ongoing training and resources to ensure they can offer comprehensive support (Ramanathan & Redelman, 2020). This involves ensuring they have current knowledge on diagnosing and treating sexual dysfunction as well as effective communication techniques to sensitively address men’s sexual health issues (Collyer et al., 2018). In addition, men’s reliance on the internet suggests a need for reliable and evidence-based online resources about sexual dysfunction (Zarski et al., 2022). The involvement of family members also emphasises the importance of fostering open and informed discussions about sexual health within families, particularly in marginalised communities (WHO, 2010). These insights can guide targeted interventions and educational efforts to improve sexual health support across these key channels.

Given the significant increase in sexual difficulties among CALD men and the identified variations in sexual help-seeking behaviour by age, sexual identity, relationship status, and number of sexual dysfunctions, it is crucial to address how these intersecting factors influence sexual healthcare and related health outcomes (Bowleg et al., 2013). By adopting an intersectional perspective, researchers and healthcare professionals can better comprehend the multifaceted nature of men’s experiences with sexual health, acknowledging the unique challenges they face at the intersections of various social identities such as age, CALD status and sexual identity (Griffith, 2018). This approach can inform tailored interventions and support services that address the diverse needs of men across different demographic groups, ultimately leading to more inclusive and culturally safe strategies for sexual health promotion and help-seeking (Heard et al., 2019).

Given the increasing prevalence of sexual health issues among Australian men, there is a need for further research to understand the factors underlying the rise in sexual difficulties. Special consideration should be given to CALD men who reported a notably higher increase in rates of sexual dysfunction compared to other groups of Australian men. Qualitative studies involving men and sexual health providers are needed to allow for a more comprehensive understanding of men’s journey towards sexual health services, including the underlying barriers and motivations (Shand & Marcell, 2021).

The study’s strength lies on the use of the four waves of Australia’s Longitudinal Study on Male Health to examine the burden of sexual dysfunctions over a ten-year period. This is significant as there has been little research examining sexual dysfunction rates using longitudinal data. Furthermore, the study has provided additional insights into the emerging research interest of sexual help seeking for sexual difficulties and factors associated with help seeking behaviour. The Ten to Men study only included participants who had sufficient English language proficiency to complete the survey. Consequently, men from CALD backgrounds who lacked English proficiency were excluded, which may limit the generalisability of the results of our analysis to all CALD men in Australia. In our logistic regression analysis aimed at identifying factors associated with sexual help-seeking behaviour, we treated the three waves as cross-sectional data. In future analyses of the Ten to Men dataset, we plan to conduct a more complex analysis to explore the longitudinal associations of health, lifestyle, behavioural and socio-economic factors with sexual dysfunction and help-seeking behaviour.

Conclusions

The present study expanded the current literature on Australian men’s sexual dysfunction and help seeking by examining longitudinal changes and factors associated with help seeking behaviour. Analysis revealed a significantly increasing burden of sexual dysfunctions, with CALD men experiencing higher increases compared to other Australian men. Moreover, most men with sexual dysfunctions do not seek help for them which suggests a high level of unmet sexual health needs. Number of sexual difficulties, age, sexual identity, relationship status, conformity to masculine norms, depression, and number of financial hardships were significantly associated with sexual health seeking behaviour. This suggests the necessity of applying an intersectional lens into the design of programs that aim to improve men’s sexual help seeking behaviour.

Funding

This research is supported a seed fund from the

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- ABS. (2022). Standards for Statistics on Cultural and Language Diversity. ABS. Retrieved June 2024 from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standards-statistics-cultural-and-language-diversity/latest-release.

- Avasthi, A., Grover, S., & Sathyanarayana Rao, T. S. (2017). Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sexual Dysfunction. Indian J Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 1), S91-s115. [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L., Teti, M., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2013). “It’s an uphill battle everyday”: Intersectionality, low-income Black heterosexual men, and implications for HIV prevention research and interventions. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 14(1), 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Collyer, A., Bourke, S., & Temple-Smith, M. (2018). General practitioners’ perspectives on promoting sexual health to young men. Aust J Gen Pract, 47(6), 376-381. [CrossRef]

- Currier, D., Pirkis, J., Carlin, J., Degenhardt, L., Dharmage, S. C., Giles-Corti, B., Gordon, I., Gurrin, L., Hocking, J., Kavanagh, A., Keogh, L. A., Koelmeyer, R., LaMontagne, A. D., Schlichthorst, M., Patton, G., Sanci, L., Spittal, M. J., Studdert, D. M., Williams, J., & English, D. R. (2016). The Australian longitudinal study on male health-methods. BMC Public Health, 16(3), 1030. [CrossRef]

- Daumler, D., Chan, P., Lo, K. C., Takefman, J., & Zelkowitz, P. (2016). Men’s knowledge of their own fertility: a population-based survey examining the awareness of factors that are associated with male infertility. Hum Reprod, 31(12), 2781-2790. [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. (2019). National Men’s Health Strategy 2020-2030.

- Elterman, D. S., Bhattacharyya, S. K., Mafilios, M., Woodward, E., Nitschelm, K., & Burnett, A. L. (2021). The Quality of Life and Economic Burden of Erectile Dysfunction. Res Rep Urol, 13, 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D. M. (2018). “Centering the Margins”: Moving Equity to the Center of Men’s Health Research. Am J Mens Health, 12(5), 1317-1327. [CrossRef]

- Heard, E., Fitzgerald, L., Wigginton, B., & Mutch, A. (2019). Applying intersectionality theory in health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion International, 35(4), 866-876. [CrossRef]

- Heiman, J. R. (2002). Sexual dysfunction: Overview of prevalence, etiological factors, and treatments. Journal of sex research, 39(1), 73-78.

- Hobbs, L. J., Mitchell, K. R., Graham, C. A., Trifonova, V., Bailey, J., Murray, E., Prah, P., & Mercer, C. H. (2019). Help-Seeking for Sexual Difficulties and the Potential Role of Interactive Digital Interventions: Findings From the Third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. J Sex Res, 56(7), 937-946. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, R., Say, L., & Temmerman, M. (2015). Sexual health, human rights, and law. Lancet, 386(9995), 725-726. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med, 16(9), 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, D., Girard, M., Dussault, É., Philibert, M., Hébert, M., Boislard, M. A., Goyette, M., & Godbout, N. (2023). Who seeks sex therapy? Sexual dysfunction prevalence and correlates, and help-seeking among clinical and community samples. PLoS One, 18(3), e0282618. [CrossRef]

- Latreille, S., Collyer, A., & Temple-Smith, M. (2014). Finding a segue into sex: young men’s views on discussing sexual health with a GP. Aust Fam Physician, 43(4), 217-221.

- Lewis, R. W., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., Bosch, R., Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Laumann, E. O., Lizza, E., & Martin-Morales, A. (2004). Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med, 1(1), 35-39. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Fan, S., Cui, J., Yang, Y., Song, Y., Kang, J., Zhang, W., Liu, K., Zhou, K., & Liu, X. (2020). The decline in sexual function, psychological disorders (anxiety and depression) and life satisfaction in older men: A cross-sectional study in a hospital-based population. Andrologia, 52(5), e13559. [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J. R., Locke, B. D., Ludlow, L. H., Diemer, M. A., Scott, R. P. J., Gottfried, M., & Freitas, G. (2003). Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 4(1), 3-25. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M. P., & Althof, S. E. (2014). A systematic review of the psychosocial outcomes associated with erectile dysfunction: does the impact of erectile dysfunction extend beyond a man’s inability to have sex? J Sex Med, 11(2), 347-363. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z., Hawkey, A. J., Baroudi, M., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2023). Men of refugee and migrant backgrounds in Australia: a scoping review of sexual and reproductive health research. Sex Health, 20(1), 20-34. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C. H., Fenton, K. A., Johnson, A. M., Copas, A. J., Macdowall, W., Erens, B., & Wellings, K. (2005). Who reports sexual function problems? Empirical evidence from Britain’s 2000 National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. Sex Transm Infect, 81(5), 394-399. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, E. D., Jr., Brock, G., Glasser, D. B., Nicolosi, A., Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Wang, T., & Gingell, C. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract, 59(1), 6-16. [CrossRef]

- Mota, N., Kraskian-Mujembari, A., & Pirnia, B. (2019). Role of Sexual Function in Prediction of Anxiety, Stress and Depression in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Applied Behavioral Sciences, 5(3), 27-33.

- Osborne, R. H., Batterham, R. W., Elsworth, G. R., Hawkins, M., & Buchbinder, R. (2013). The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 13, 658. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V., & Redelman, M. (2020). Sexual dysfunctions and sex therapy: The role of a general practitioner. Australian Journal for General Practitioners, 49, 412-415. https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2020/july/sexual-dysfunctions-and-sex-therapy.

- Richters, J., Yeung, A., Rissel, C., McGeechan, K., Caruana, T., & de Visser, R. (2022). Sexual Difficulties, Problems, and Help-Seeking in a National Representative Sample: The Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(3), 1435-1446. [CrossRef]

- Schlichthorst, M., Sanci, L. A., & Hocking, J. S. (2016). Health and lifestyle factors associated with sexual difficulties in men – results from a study of Australian men aged 18 to 55 years. BMC Public Health, 16(3), 1043. [CrossRef]

- Sever, Z., & Vowels, L. M. (2023). Beliefs and Attitudes Held Toward Sex Therapy and Sex Therapists. Arch Sex Behav, 52(4), 1729-1741. [CrossRef]

- Sever, Z., & Vowels, L. M. (2024). Barriers to Seeking Treatment for Sexual Difficulties in Sex Therapy. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 23(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Shand, T., & Marcell, A. V. (2021). Engaging Men in Sexual and Reproductive Health. In: Oxford University Press.

- Sheng, Z. (2021). Psychological consequences of erectile dysfunction. Trends in Urology & Men’s Health, 12(6), 19-22. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. M. A., Lyons, A., Ferris, J. A., Richters, J., Pitts, M. K., Shelley, J. M., Simpson, J. M., Patrick, K., & Heywood, W. (2013). Incidence and Persistence/Recurrence of Men’s Sexual Difficulties: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Health and Relationships. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(3), 201-215. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G., Fugl-Meyer, K. S., & Fugl-Meyer, A. R. (2000). Impact of erectile dysfunction on quality of life: patient and partner perspectives. International Journal of Impotence Research, 12(4), S144-S146. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2010). Developing sexual health programmes: A framework for action.

- WHO. (2015). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th revision, Fifth edition, 2016 ed.). World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/246208.

- Xiao, Y., Xie, T., Peng, J., Zhou, X., Long, J., Yang, M., Zhu, H., & Yang, J. (2023). Factors associated with anxiety and depression in patients with erectile dysfunction: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 36. [CrossRef]

- Zarski, A. C., Velten, J., Knauer, J., Berking, M., & Ebert, D. D. (2022). Internet- and mobile-based psychological interventions for sexual dysfunctions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit Med, 5(1), 139. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).