1. Introduction

Voluntary cosmetic depigmentation is defined as all practices aimed at lightening the skin through the cosmetic use of products with clearly established depigmenting properties [

1]. It is mainly practiced by women in Africa [

2,

3,

4]. Its prevalence among women in Nigeria was estimated at 40.09% in 2021 [

4]. In Burkina Faso, Andonaba et al. reported a prevalence of 49.2% in the city of Bobo-Dioulasso in 2016 [

5]. Prevalence in the city of Ouagadougou is lower and had been estimated in 2005 at 39.5% [

6]. The harmful effects of this practice on health are numerous [6-9], and in some Black African countries, it constitutes a real public health problem [2,6,9-11].

The depigmenting agents usually used are of natural or synthetic origin, and are most often used in combination. They most often consist of strong-class of dermocorticoids (clobetasol propionate, for example), hydroquinone in variable concentrations ranging from 2.00 to 8.00%, or keratolytics (salicylated vaseline with concentrations of up to 50%). There are also homemade preparations containing mercury salts, soda-based soaps, and oxidizing mixtures (based on bleach, hydrogen peroxide, peroxides, or perchlorates, etc.) [

2,

9,

12,

13]. Natural substances used in this practice include kojic acid, alpha arbutin, vitamin C, azelaic acid, retinoids, glutathione, and alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs) [12,14-16]. Andonaba et al. showed, based on label statements, that 81.6% of lightening cosmetics marketed in the city of Bobo Dioulasso in 2017 contained hydroquinone. The remaining products contained various mixtures (11.12%), EDTA (8.33%), kojic acid (4.86%), and unknown substances (14.58%). They also revealed that 98.96% of products did not bear any indication of their origins [

5]. This raises the question of whether the claims made on the labels of these products are accurate and do not relate to misleading commercial practices.

It is with this in mind that we conducted this study, the aim of which was to verify the concordance between the active ingredients (presence and rate of incorporation) mentioned on the label and the actual content of these lightening cosmetic products. After assessing the physical and regulatory characteristics of a sample of lightening cosmetics collected in the city of Ouagadougou, we carried out an analytical screening to detect the presence of hydroquinone (and its ethyl, methyl, and benzyl ethers), clobetasol propionate and kojic acid in these products, and to quantify these three active ingredients. These three depigmenting substances were targeted because they are the most commonly used in lightening cosmetic products at very high percentages, implying numerous side effects [

13,

17,

18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

Kojic acid (99.0%) and hydroquinone monoethyl ether (99.0%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Beclomethasone (99.9%) is from the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur) and Clobetasol propionate (99.9%) is from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP, Rockville, USA). Hydroquinone monomethyl ether (98.0%) and hydroquinone monobenzyl (99.0%) were supplied by Fluka and hydroquinone (99.0%) by Panreac (Spain). Hydrochloric acid (37.0%) and orthophosphoric acid (85.0%) are from VWR Chemicals (USA). Methanol and acetonitrile are HPLC grade and were obtained from Carlo Erba Reagents (Val-de-Reuil, France). Tetrahydrofuran for analysis was obtained from Scharlau (Spain).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sampling

Sample collection sites were the main stores selling cosmetics in the 12 districts of Ouagadougou. These stores were identified based on information obtained from hair salons, beauty salons, and users. To collect the samples, one store was selected in each district, for a total of 12 stores. These 12 stores were chosen based on their reputation for selling lightening products and the diversity of the product range on offer.

We went to each of the 12 selected boutiques to ask the managers for advice, expressing our desire to lighten our skin. After discussions with the managers, we bought two or three products in each boutique, based on the advice we had received and taking care not to use any brand of product we had already bought in previous boutiques. During all stages of the study, the samples collected were kept under the storage conditions specified by the manufacturer or, if necessary, at 20°C in an air-conditioned room.

2.2.2. Evaluation of sample characteristics

The physical form and labeling characteristics of the samples collected were assessed against the regulatory requirements of the WAEMU (West African Economic and Monetary Union) [

19]. The information required on the label and/or packaging of cosmetic products was documented. This information includes the brand name, claimed properties, depigmenting substances mentioned on the packaging, the identity, address, and origin of the manufacturer, INCI list (International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients), capacity, batch number, date of manufacture, expiration date, role and terms of use of the product.

2.2.3. Identification and assay of hydroquinone and its ether derivatives

The method for detection and assay of hydroquinone and its ether derivatives was slightly adapted from the standard BS EN 16956:2017 [

20]. A sample of each cosmetic product was accurately weighed (Metler Toledo XPE206DR balance) and extracted with water/methanol solvent (50:50 v/v) at 60°C. The filtrate was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent 1260 infinity HPLC system coupled to a diode array detector (DAD)). The chromatographic conditions used were: wavelength 295 nm, mobile phase water/tetrahydrofuran (55:45 v/v), elution flow rate 1.0 mL/min, injection volume 10.0 µL, column temperature 30°C, ODS-C18 column (250mm x 4.6 mm x 5 µm).

The reference solution was prepared extemporaneously as indicated in BS EN 16956:2017 [

20].

The analytical method was verified as described in the ICH guide to reproducibility and repeatability parameters [

21].

2.2.4. Identification and assay of kojic acid

Kojic acid was extracted from 2.0 g ± 0.1 g of sample with a 0.1N hydrochloric acid solution and then filtered. The kojic acid reference solution (200µg/mL) was prepared by dissolving 1.0 mg kojic acid standard in a 50.0 mL mobile phase [

22]. The reference solution and extracts were analyzed by HPLC-DAD under the following chromatographic conditions: wavelength 214 nm, mobile phase methanol/distilled water/orthophosphoric acid (250.0mL + 750.0mL + 3.0mL), flow rate 0.8 mL/min, injection volume 5.0 µL, column temperature 40°C, XDB-C8 column (160mm x 4.6 mm x 5 µm). The reproducibility and repeatability of the method were also checked according ICH guidelines [

21].

2.2.5. Identification and assay of clobetasol propionate

The identification and assay of clobetasol propionate from the sample was carried out according USP monograph. For the extraction of clobetasol propionate and reference solution preparation, methanol was used as solvent [

23].

The reference solution and extracts were analyzed by HPLC-DAD at a wavelength of 240 nm, using a mobile phase consisting of methanol/phosphate buffer pH 5.5/acetonitrile (10:47.5:42.5 v/v/v). The elution flow rate was 1.0 mL/min and the injection volume was 10 µL. An L1 column (150mm x 4.6mm x 5 µm) was used at a temperature of 30°C. The system suitability was checked before the start of the analyses, according the requirements of the USP [

23].

2.2.6. Data validation and statistical analysis

All the equipment used was qualified and suitable for its intended use.

All measurements were carried out in triplicate and results expressed as the average percentage of the three analyses.

Retention times used for the identification of hydroquinone and its derivatives were 3.7 min for hydroquinone, 4.2 min for monomethyl ether, 4.5 min for monoethyl ether, and 5.9 min for monobenzyl ether. Retention times for kojic acid and clobetasol propionate were 2.4 min and 7.4 min, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of samples collected

3.1.1. General characteristics

A total of 29 samples of lightening products from different brands were collected. Information on the samples collected is presented in

Table 1 below:

3.1.2. Product forms

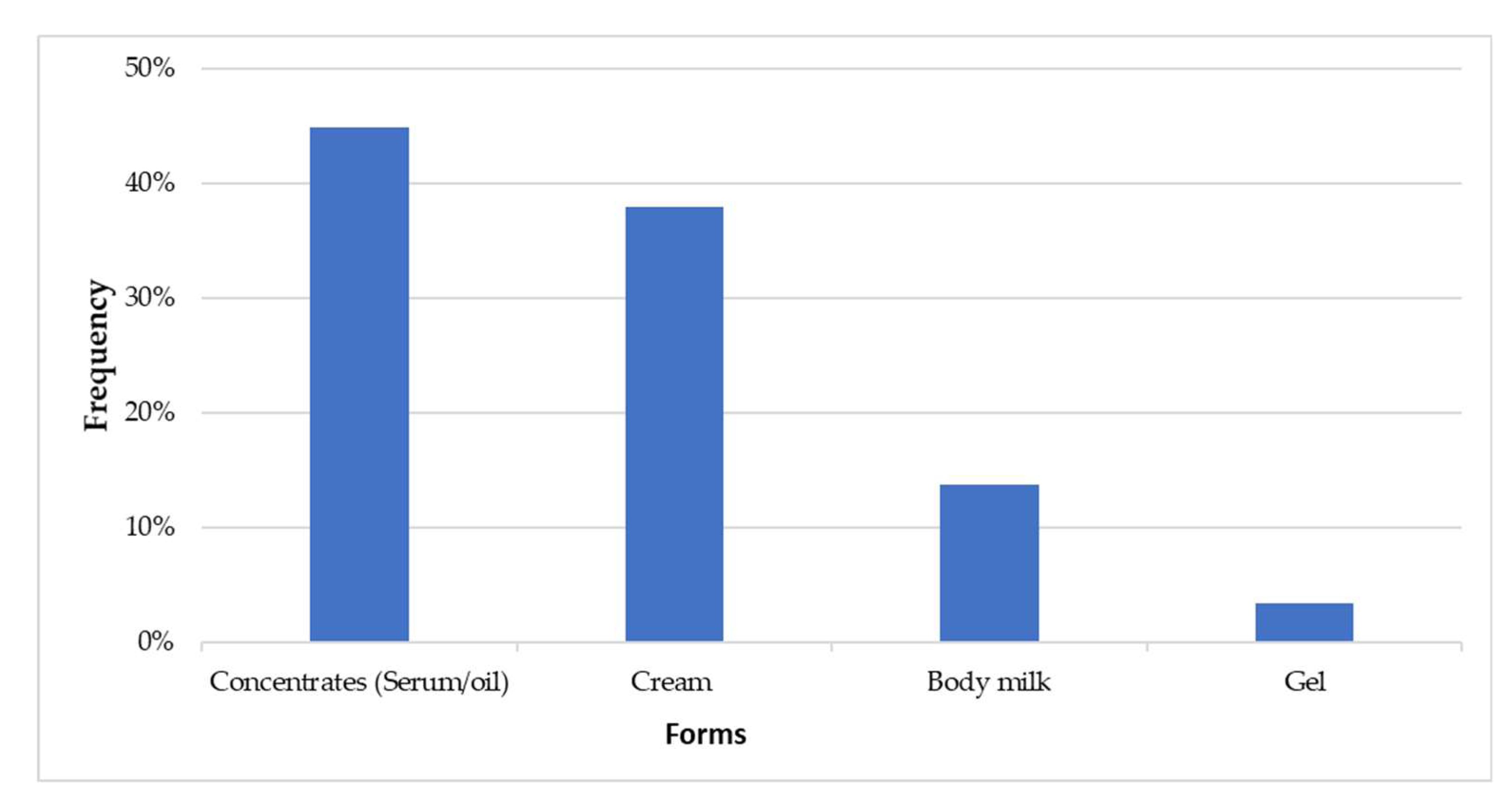

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of collected samples based on their dosage forms.

Oils/serums (44.59%) and creams (37.93%) were the two most commonly used dosage forms of skin-lightening cosmetics.

3.1.3. Manufacturer's Origin

Table 2 presents the distribution of collected samples according to their origins. It should be noted that the country of origin of the manufacturer was not specified in 20.69% of the collected samples. Apart from these products, Côte d'Ivoire and Togo were the two main suppliers of the collected skin-lightening cosmetics.

3.2. Evaluation of Product Labeling

3.2.1. Compliance with Labeling Rules

Table 3 displays the distribution of collected samples according to the various mandatory labeling statements found on the packaging. It is observed that the least adhered-to statements are the lot number and the manufacturing date.

3.2.2. Mentions of the Presence of Depigmenting Substances on Labels

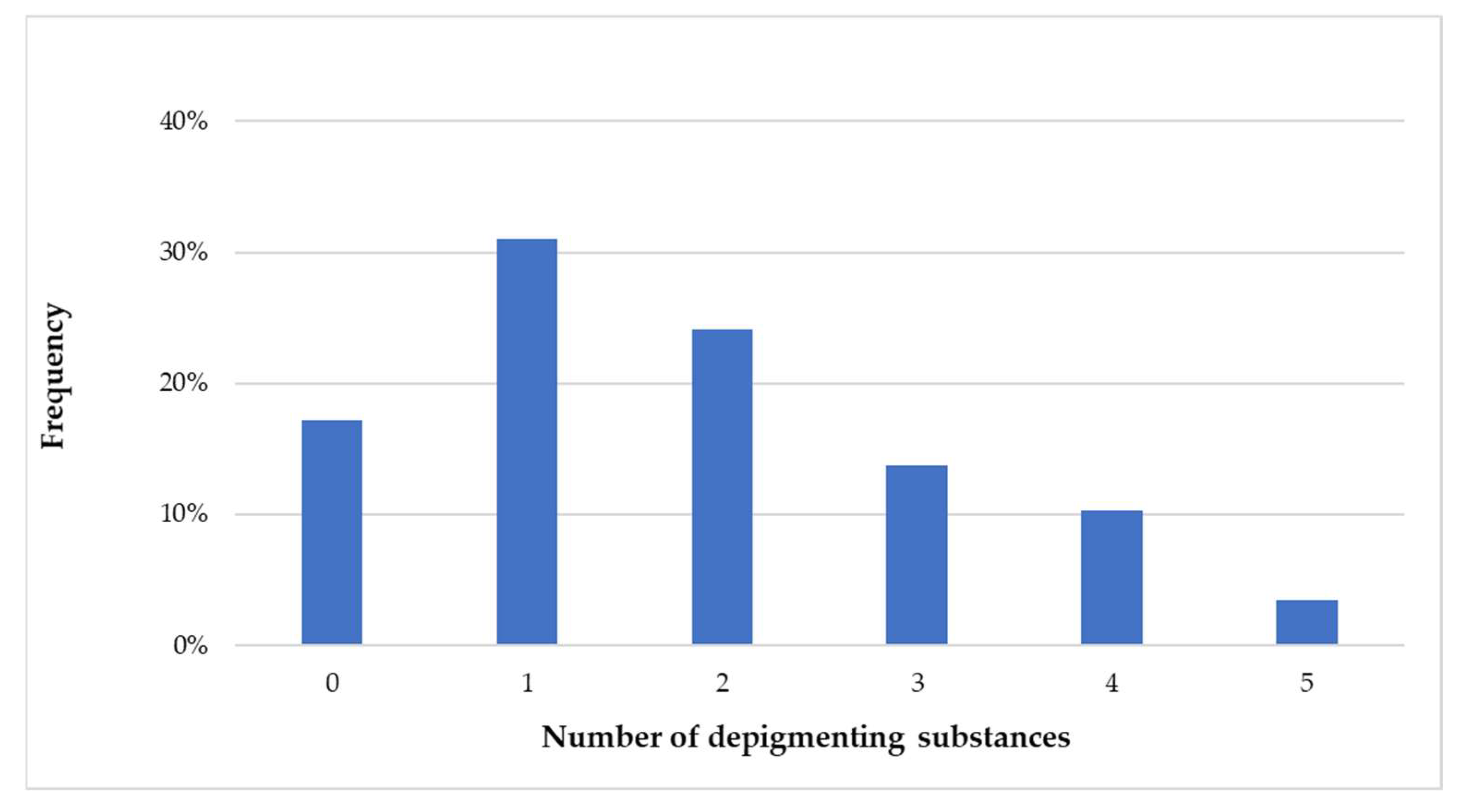

Based on label statements, 82.76% of the collected skin-lightening cosmetics explicitly indicated the presence of depigmenting substances. Among these products, 31.03% claimed the presence of a single depigmenting substance, while 51.72% reported combinations of multiple depigmenting substances.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of samples according to the number of depigmenting substances mentioned on the packaging.

Table 4 shows the distribution of collected samples that claimed the presence of the three depigmenting substances of interest (hydroquinone, kojic acid, and/or clobetasol propionate) on their labels.

As can be observed, kojic acid is the most mentioned depigmenting substance (24.12%) on the labels of the collected samples.

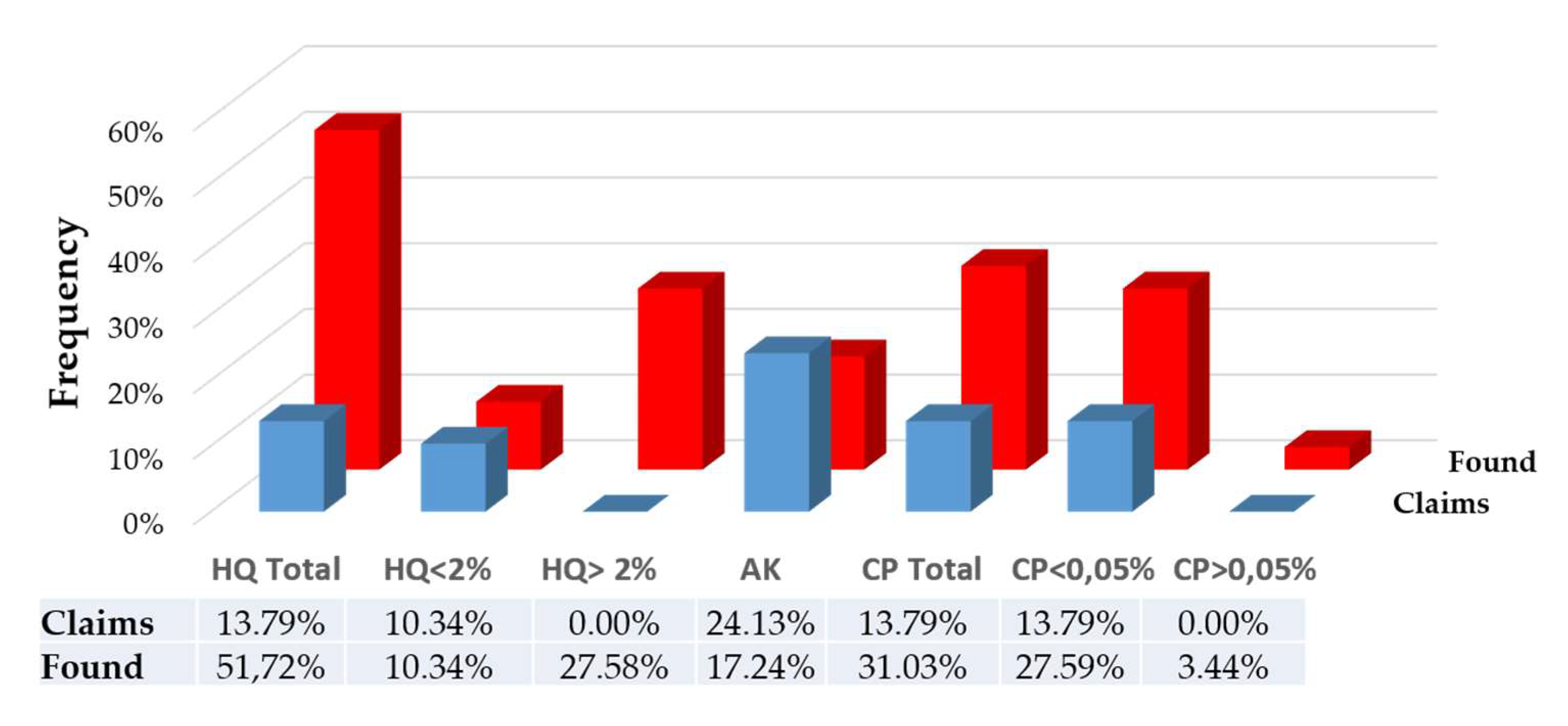

3.3. Results of Screening tests and assay for Depigmenting Substances

The results of the screening analyses and assay show that the presence of hydroquinone was mentioned in four (04) products (13.79%), while fifteen (15) products (51.72%) contained it. Furthermore, the presence of hydroquinone at concentrations greater than 2% was not mentioned in any product, but eight (08) products (27.58%) contained it at higher concentrations. Clobetasol propionate was declared in four (04) products (13.79%), while nine samples (31.03%) contained it. Additionally, one (01) sample had a clobetasol propionate content exceeding 0.05%, even though no sample mentioned a concentration higher than this value. Lastly, while seven (07) samples, or 24.13%, claimed the presence of kojic acid, only five (05) products, or 17.24%, actually contained it.

Table 5 presents the results of screening and quantification tests for the three depigmenting substances.

Figure 3 provides a comparison of the proportions of products claiming the presence of each of the three sought-after depigmenting substances and those that contain them.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Collected Samples

Twenty-nine (29) samples of cosmetic products from different brands claiming 'lightening,' 'clarifying,' or 'whitening' properties were collected. These products were in four different dosage forms: concentrates oil/serum (44.59%), cream (37.93%), lotion (13.79%), and gel (3.45%). Nyiragasigwa Françoise noted in 2021 that there was concurrent use of soap and cream in 61.5% of cases among Black populations in Belgium [

24].

The country of origin of the manufacturer was not specified in 20.69% of the collected samples. The products collected were manufactured in neighboring countries of Burkina Faso, such as Côte d'Ivoire (20.69%) and Togo (17.24%), accounting for 37.93% of the products. Products manufactured in other African countries (Cameroon, Egypt, Senegal) represented 13.79%. The remaining 27.58% were imported from Europe (France, Italy, England), India, the Philippines, Thailand, and the United States of America (USA). No cosmetic product from the collected brands was locally manufactured in Burkina Faso. As Tra Vanessa also mentioned in her study that the basic products used for skin depigmentation in Burkina Faso were all imported. However, mixtures of these imported brand products were usually prepared locally by sellers for the specific needs of each customer [

25].

4.2. Compliance with Labeling Rules

Compliance with labeling rules was assessed following the WAEMU guidelines [

19]. The five most frequently indicated labeling statements on the containers and/or packaging of collected products were the product's purpose (86.20%), the content (indicated by weight or volume) (82.75%), country of origin (79.31%), the list of ingredients or INCI list (79.31%), and the manufacturer's identity (75.86%).

The INCI list is a mandatory nomenclature for cosmetic products. Manufacturers are not obligated to indicate the concentration of each ingredient due to "trade secret," but they must list them in descending order of their weight if they are dosed at more than 1.00%. Below 1.00%, the manufacturer can list them in any order on the packaging [

19].

The mention of the product's indication, appearing on 86.20% of the samples, is a safety requirement of the WAEMU guidelines. It aims to protect human health and provide clear information to consumers regarding the product's use and application [

19].

Out of the 23 products (79.31%) that mentioned the country of origin of the manufacturer, 22 (75.86%) included the manufacturer's identity, and 20 (68.96%) clearly stated the manufacturer's address, following WAEMU guidelines [

19].

The expiry date or expiration date was mentioned on 62.06% of the products. This date is defined as the date until which the product, when stored under appropriate conditions, continues to fulfill its function. It is indicated on products mainly as "Best before (date)" or as the duration of use after opening the bottle, expressed in months or years. Indeed, WAEMU guidelines specify that for cosmetic products with a minimum durability exceeding thirty months, mentioning the expiry date is not mandatory. These products can only indicate the allowed duration of use after opening without harm to the consumer [

19].

The mention of the manufacturing lot number was the least indicated on the samples, appearing on only 24.13% of them. The manufacturing lot number, indicated as numbers and/or letters, serves to identify and track a set of identical products that share certain production characteristics (time and date of production, identification code, etc.). This lot number ensures product traceability and its historical and contextual data [

19].

4.3. Mentions of the Presence of Depigmenting Substances on Labels

In cosmetics, the active ingredient is the guarantor of the product's properties, and its mention on the label and/or packaging is mandatory [

26].

The evaluation of the labels and/or packaging of the collected products shows that 82.76% explicitly indicated the presence of one (31.03% of cases) or multiple depigmenting ingredients (51.72%). The most frequently mentioned depigmenting molecules were, respectively, kojic acid, hydroquinone, clobetasol propionate, AHAs, niacinamide, and retinol.

Kojic acid or 5-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-4-pyrone is a natural substance produced by several species of fungi, especially Aspergillus oryzae [

27]. Its presence was mentioned on the labels of 24.12% of the collected products. Andonaba et al. [

5] found in 2019 that only 4.86% of skin-lightening cosmetics marketed in the city of Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso mentioned the presence of hydroquinone. Indeed, since the ban on the use of hydroquinone in cosmetic products in Europe in 2001 [

27]. Due to its numerous adverse effects, the use of kojic acid as a skin-lightening or depigmenting agent has become widespread. The natural origin of kojic acid and its fewer adverse effects are highlighted, and all manufacturers would like to display it on their packaging to attract customers. However, it is important to note that kojic acid has a strong allergenic potential with a relatively high frequency of contact dermatitis and erythema when improperly used on the skin. It also possesses antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal properties [

12,

29].

Hydroquinone and its derivatives were mentioned on the label and/or packaging of 13.79% of the collected samples. Tra Vanessa [

25] also noted in 2019 a low rate of 15.0%, compared to previous studies' data in 2017 in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso (81.6% mentioned the presence of hydroquinone) [

5]. Hydroquinone and its derivatives have been a reference for depigmenting agents for many years. However, our results show that they are being used less and less now. This could be explained by the presence of new depigmenting molecules on the market, such as kojic acid. It is also possible that manufacturers avoid declaring the presence of hydroquinone to avoid attracting consumers' attention. These manufacturers may continue to incorporate it into their preparations without mentioning it on the label and/or packaging because it is inexpensive and effective. In this latter case, it constitutes deceptive claims. Indeed, hydroquinone and its derivatives are powerful melanogenesis inhibitors, and highly effective in skin whitening. However, they have numerous adverse effects that have led to the prohibition of cosmetic products in the European Union [

28]. They are highly cytotoxic and are involved in the development of ochronosis after prolonged use [

30]. Despite the evidence of their toxicity, the incorporation of hydroquinone in cosmetics remains allowed in WAEMU countries with an exemption dose of 2% [

19].

Clobetasol propionate was declared at a concentration <0.05% in 13.79% of the samples. It is a dermocorticoid, a topical steroid anti-inflammatory used locally. As depigmentation is a side effect, clobetasol propionate is used as a whitening agent in illegally sold cosmetic preparations. Indeed, the incorporation of dermocorticoids in cosmetic products is strictly prohibited in WAEMU countries, regardless of their concentration [

19]. They are only allowed in dermatological medications at the recommended therapeutic dose of 0.05%.

It is important to emphasize that some products mentioned the presence of several active ingredients, often up to 5 depigmenting molecules. Combinations of 2, 3, 4, or 5 depigmenting molecules represented 24.14%, 13.79%, 10.34%, and 3.45%, respectively.

Finally, mentions of certain adjuvants were noted on the labels and/or packaging of the collected products. These adjuvants aim to facilitate the cutaneous penetration of active ingredients. They include actives like AHAs and retinoic acid, and actual adjuvants like propylene glycol [

31].

4.4. Screening and Assay of Hydroquinone, Kojic Acid, and Clobetasol Propionate

Analytical screening was conducted on the 29 collected lightening cosmetic products to detect the presence of hydroquinone and its derivatives, clobetasol propionate, and kojic acid. These three molecules were the most frequently mentioned on the product labels. They are among the most toxic substances [

17], and their use is subject to strict regulations [

19,

28]. The results showed that 24 products, or 82.76%, contained one or more of these three depigmenting molecules, either alone or in combination, while only 51.72% mentioned their presence. Subsequent dosage tests for these three molecules were performed on the products where their presence was detected.

The analytical results showed that 51.72% of the samples contained hydroquinone, while only 13.79% declared its presence. We also found that 27.59% of the products contained hydroquinone concentrations exceeding 2%, while no product had indicated such high concentrations. It should be noted that among the products that expressly claimed to contain hydroquinone at a concentration below 2%, two (02) of them contained it but at a higher concentration. In 2019, Tra Vanessa [

25] found that 44.12% of samples of cosmetic products collected in Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire contained hydroquinone at concentrations below 2%, even though its presence was not mentioned on the labeling. Furthermore, in 2014, a study conducted in West Africa and Canada showed that 38.00% of samples had hydroquinone concentrations exceeding standards [

13]. On the other hand, Siyaka et al. 2016 collected 20 samples of lightning creams in Nigeria and found that all of them contained hydroquinone at percentages ranging from 0.07 to 4.00% [

32]. The high levels of hydroquinone (exceeding 2%) detected in 27.59% of the samples in our study expose users to the risk of exogenous ochronosis and other health problems [

17,

30].

The analyses also revealed that 31.03% of the samples contained clobetasol propionate, with one sample having a concentration of the active ingredient exceeding 0.05%. However, the presence of this active ingredient was only declared in 13.79% of the samples, and none indicated doses exceeding 0.05%. There is a slight decrease in the use of this ingredient in our study compared to that of Gbetoh and Amyot [

13] in 2014, who detected the presence of clobetasol propionate in 39.00% of the samples. Our results show that clobetasol propionate is incorporated in small quantities into lightening preparations and is generally combined with another depigmenting agent to have a synergistic effect. However, clobetasol propionate is a potent local corticosteroid that should only be dispensed by medical prescription. Preparations containing it should not be available in cosmetic product shops. The inappropriate use of this potent corticosteroid exposes individuals to increased risks of serious adverse effects such as the spread and worsening of untreated infections, irreversible skin thinning, dermatitis, acne, and hypertrichosis [

9].

HPLC analyses also revealed that, out of the 7 samples (24.13%) claiming the presence of kojic acid, only 5 products (17.24%) contained it. The incorporation levels of kojic acid found were still low and did not reach 1%, which is the allowed concentration in Europe [

28]. These results lead us to believe that manufacturers often declare the presence of kojic acid, which is popular among consumers but may not use it because its cost is very high compared to that of hydroquinone and clobetasol propionate. However, in 2018, Verdoni et al. found cases of lightening cosmetic products collected in Paris and Benin that contained kojic acid even though it was not listed on their labels [

33]. It is important to note that WAEMU community regulations are silent on the use of kojic acid in cosmetic products.

Based on our laboratory analysis results, we observed that 12 cosmetic products in our sample, representing 41.38%, contained combinations of two of the three molecules sought after. The combinations found were hydroquinone + clobetasol propionate (8 products, or 27.59% of the samples), hydroquinone + kojic acid (3 products, or 10.34% of the samples), and kojic acid + clobetasol propionate (1 product, or 3.45% of the samples). Verdoni et al. also found in their study 3 products out of 7 that contained both hydroquinone and kojic acid [

33].

5. Conclusions

Our study allowed us to verify the conformity of claims related to hydroquinone, clobetasol propionate, and kojic acid in cosmetic products marketed in the city of Ouagadougou. The analytical data show that the declarations on the labels of these products are often misleading. These results should be used to establish stricter regulations on cosmetic products in the WAEMU region and to raise awareness among stakeholders.

Finally, the development of an analytical method that allows for simultaneous detection and quantification of these three molecules in the same sample will enable better tracking of these three depigmenting substances in cosmetic products sold at the community level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B Gérard Josias YAMEOGO and Nomtondon Amina OUEDRAOGO; methodology, Mohamed BELEM and Ouéogo NIKIEMA; validation, B. Gérard Josias YAMEOGO and Ouéogo NIKIEMA; formal analysis and investigation, B.A Lydiane Sandra ILBOUDO, Mohamed BELEM and Bertrand GOUMBRI; resources, B Gérard Josias YAMEOGO.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A Lydiane Sandra ILBOUDO; writing—review and editing, Hermine ZIME-DIAWARA and B. Charles SOMBIE; supervision, Rasmané SEMDE; project administration, Elie KABRE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Couteau, C.; Coiffard, L. Overview of skin whitening agents: Drugs and cosmetic products. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glèlè-Ahanhanzo, Y.; Kpozehouen, A.; Maronko, B.; Azandjèmè, C.; Mongbo, V.; Sossa-Jérôme, C. "Avoir la peau claire...…et pourquoi pas? " : dépigmentation volontaire chez les femmes dans une région du sud-ouest du Bénin. Pan African Medical Journal 2019, 33. [CrossRef]

- Kourouma, H.S.; Gbandama, K.K.P.; Allou, A.S.; Kouassi, Y.I.; Kouassi, K.A.; Kassi, K.; et al. La dépigmentation cutanée volontaire chez les adolescents à peaux foncées: résultats d’une enquête CAP à Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire). Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie 2019, 146, A236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbi, O.G.; Kasia, B. Prevalence, determinants and perception of use of skin lightening products among female medical undergraduates in Nigeria, Skin Health Dis 2021, 1, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Andonaba, J.-B.; Korsaga-Somé, N.N.; Diallo, B.; Yabré, E.; Konaté, I.; Ouédraogo, A.N.; Niamba, P.; Traoré, A. Situation of Artificial Depigmentation among Women in 2016 to Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications 2017, 7, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traore, A.; Kadeba, J.-C; Niamba, P.; Barro, F.; Ouedraogo, L. Use of cutaneous depigmenting products by women in two towns in Burkina Faso: epidemiologic data, motivations, products and side effects. Int J Dermatol. 2005, 44(s1) 30-32. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.H.; Sakakibara, M.; Sera, K.; Andayanie, E. Mercury exposure and health problems of the students using skin-lightening cosmetic products in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Todo, H.; Akiyama, T.; Hirata-Koizumi, M.; Sugibayashi, K.; Ikarashi, Y.; Ono, A.; Hirose, A.; Yokoyama, K. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2016, 81, 128-135. [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.C.A. Spreading of Dangerous Skin-Lightening Products as a Result of Colourism: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebe M, Yahya S, Lo B, Ball M. Etude des complications de la dépigmentation artificielle à Nouakchott, Mauritanie. Mali médical. 2015, 30.

- Ben, E.K.T.; Alexis, A.; Mohamed, N. ; Wang, Y-H.; Khan, I.A.; Liu, B. Skin Bleaching and Dermatologic Health of African and Afro-Caribbean Populations in the US: New Directions for Methodologically Rigorous, Multidisciplinary, and Culturally Sensitive Research, Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) (2016) 6:453–459. [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, M.; Eslamifar, M.; Khezri, K. Kojic acid applications in cosmetic and pharmaceutical preparations. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbetoh, M.H.; Amyot, M. Mercury, hydroquinone and clobetasol propionate in skin lightening products in West Africa and Canada. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Arbutin as a skin depigmenting agent with antimelanogenic and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, A.; Wasnik, S.; Sabale, V. A Systematic Review on Skin Whitening Product. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2021, 71, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, P.; Landreau, A.; Azoulay, S.; Michel, T.; Fernandez, X. Skin Whitening Cosmetics: Feedback and Challenges in the Development of Natural Skin Lighteners, Cosmetics 2016, 3, 36, 1-24; [CrossRef]

- Owolabi J.O., Fabiyi O.S., Adelakin L.A, Ekwerike M.C. Effects of Skin Lightening Cream Agents- Hydroquinone and Kojic Acid, on the Skin of Adult Female Experimental Rats. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology 2020,13, 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, M.S.; Traoré, F.; Tapsoba, G.P.; Ouédraogo, N.A.; Bonkoungou, M.; Korsaga/Somé, N.; Barro/Traoré, F.; Niamba, P.; Traoré, A. Dépigmentation cutanée artificielle : motivations, pratiques et risques dans une ville du Burkina Faso, Annales de dermatologie et de vénéréologie 2019, 146(12S). doi : 10.1016/j.annder.2019.09.

- Commission de l’UEMOA. Annexes des lignes directrices pour l’homologation des produits cosmétiques dans les états membres de l’UEMOA. 2010.

- British Standard EN 16956. Cosmetics - Analytical methods - HPLC/UV method for the identification and assay of hydroquinone, ethers of hydroquinone and corticosteroids in skin whitening cosmetic products, 2017.

- International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Harmonized tripartite guideline validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology, ICH Q2 (R1), 2005.

- Moffat, A.C.; Osselton, M.D.; Widdop, B. Clarke’s analysis of drugs and poisons, Pharmaceutical press 2011, 4th ed.

- United States Pharmacopeial Convention. Monograph for Clobetasol propionate cream. In USP45-NF40, 2022, 1, pp. 1080–1081.

- Nyiragasigwa, F. Les facteurs associés à la dépigmentation volontaire chez les personnes de peau noire en Belgique. Mémoire Master en sciences de la santé publique, finalité spécialisée, Faculté de santé publique, Université catholique de Louvain, 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/thesis:30866.

- Tra, V.B.C. Recherche et dosage de l’hydroquinone dans les produits dépigmentants collectés dans les villes d’Abidjan et de Ouagadougou. Thèse d'exercice en Pharmacie N° 367, Université Joseph KI-ZERBO, Ouagadougou 2019.

- Brin, A-J. Ingrédients cosmétiques. In Actifs et additifs en cosmétologie, 3e édition; Martini, M-C; Seiller, M.; Tec & Doc Lavoisier, 2006, pp. 67-78.

- Shifali, C.; Vijay, L.J.; Vinod, K.; Sumit, G. G.; Saurabh, S. Fungal production of kojic acid and its industrial applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2023, 107, 2111–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Européenne (CE). Règlement (CE) no 1223/2009 du Parlement européen et du Conseil du 30 novembre 2009 relatif aux produits cosmétiques, 2009.

- Phasha, V.; Senabe, J.; Ndzotoyi, P.; Okole, B.; Fouche, G.; Chuturgoon, A. Review on the Use of Kojic Acid—A Skin-Lightening Ingredient. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, S.; Taylor, S.; Oyerinde, O.; Nurmohamed, S.; Dlova, N.; Sarkar, R.; Galadari, H.; Manela-Azulai, M.; Chung, H.S.; Handog, E.; et al. The dark side of skin lightening: An international collaboration and review of a public health issue affecting dermatology. Int. J. Women Dermatol. 2021, 7, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.C; Yang, J.H. Dual Effects of Alpha-Hydroxy Acids on the Skin. Molecules, 2018, 23, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siyaka, L.; Joda, A.E.; Yesufu, H.B.; Akinleye, M.O. Determination of hydroquinone content in skin lightening creams in Lagos, Nigeria, The Pharma Innovation Journal, 2016, 5, 101-105.

- Verdoni, M.; De Pomyers, H.; Gigmes, D.; Luis, J.; Migan, N.; Badirou, E.M.; et al. Méthode d’identification et de quantification par CLHP/SM de substances interdites et/ou réglementées incorporées dans des formulations de produits cosmétiques « éclaircissants ». Toxicologie Analytique et Clinique, 2018, 30, 61–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).