Submitted:

11 October 2023

Posted:

13 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sсope of Research

2.2. Ziziphora serpyllacea Plant (Thyme ziziphora)

2.3. Preparation of Ziziphora serpyllacea Plant Extract

2.4. Determination of the Cytotoxic Activity of Ethanol Extract

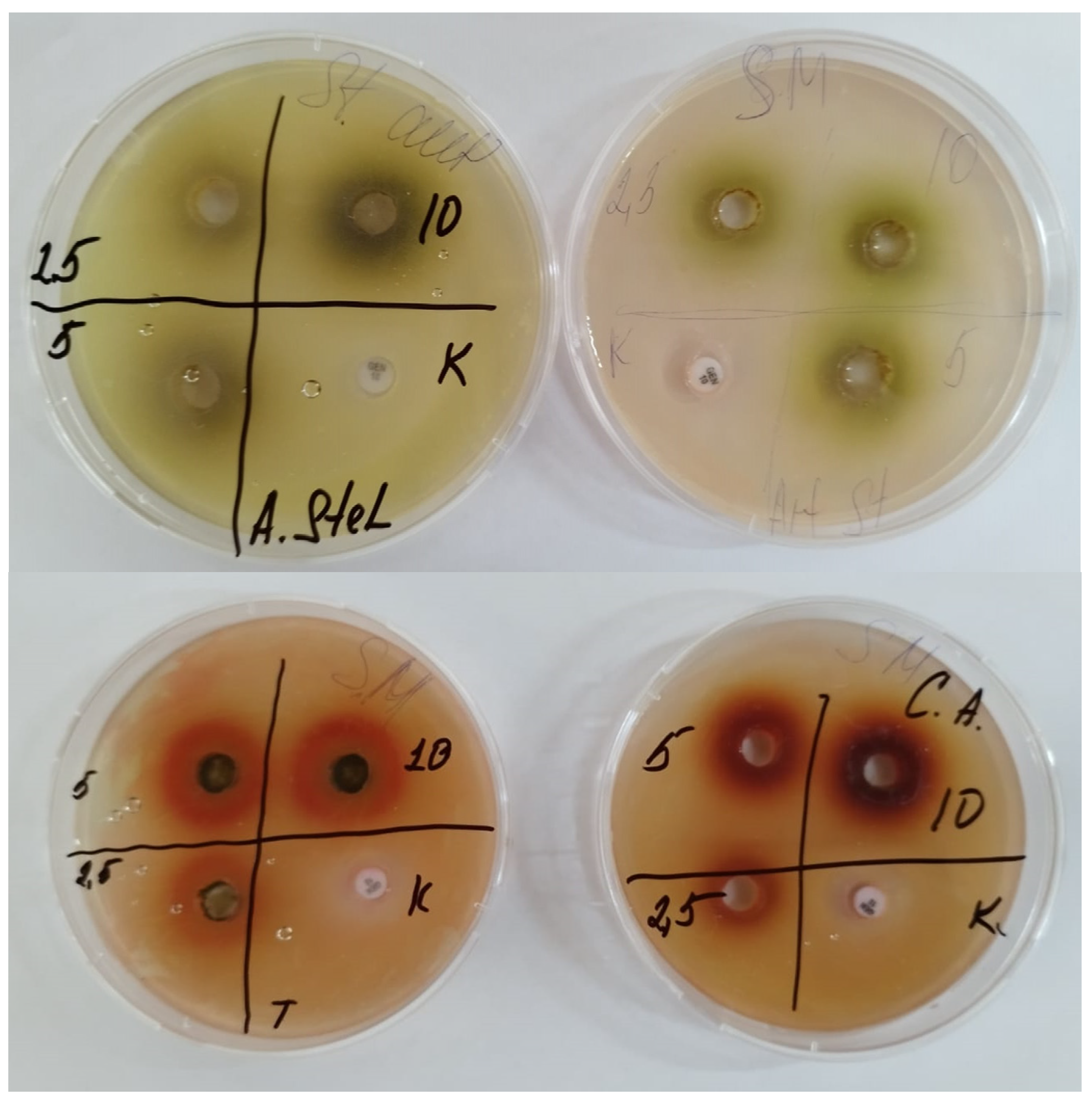

2.5. Determination of Antimicrobial and Antifungal Activity

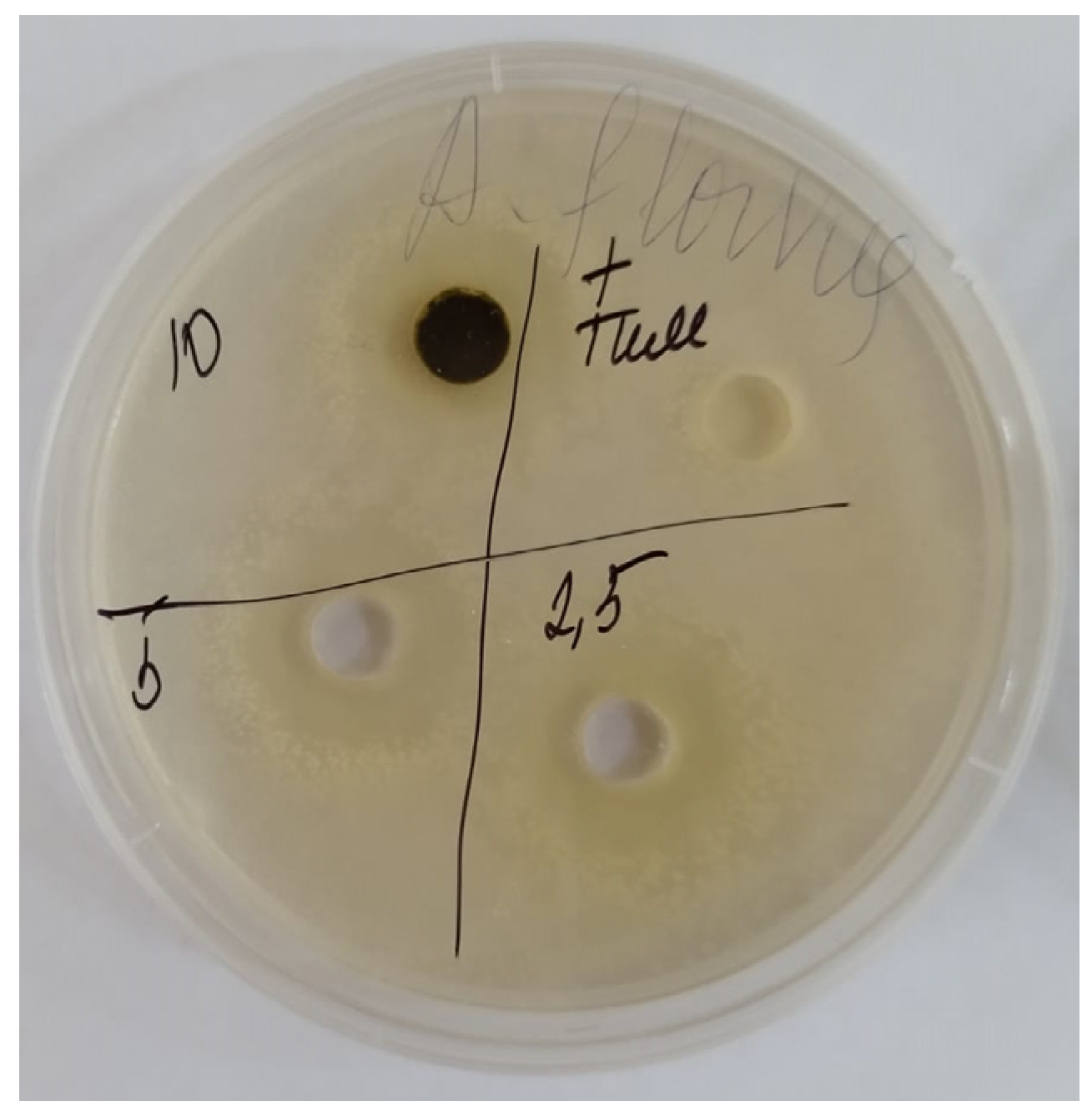

2.6. Aspergillus flavus Strain Cultivation and Nut Contamination

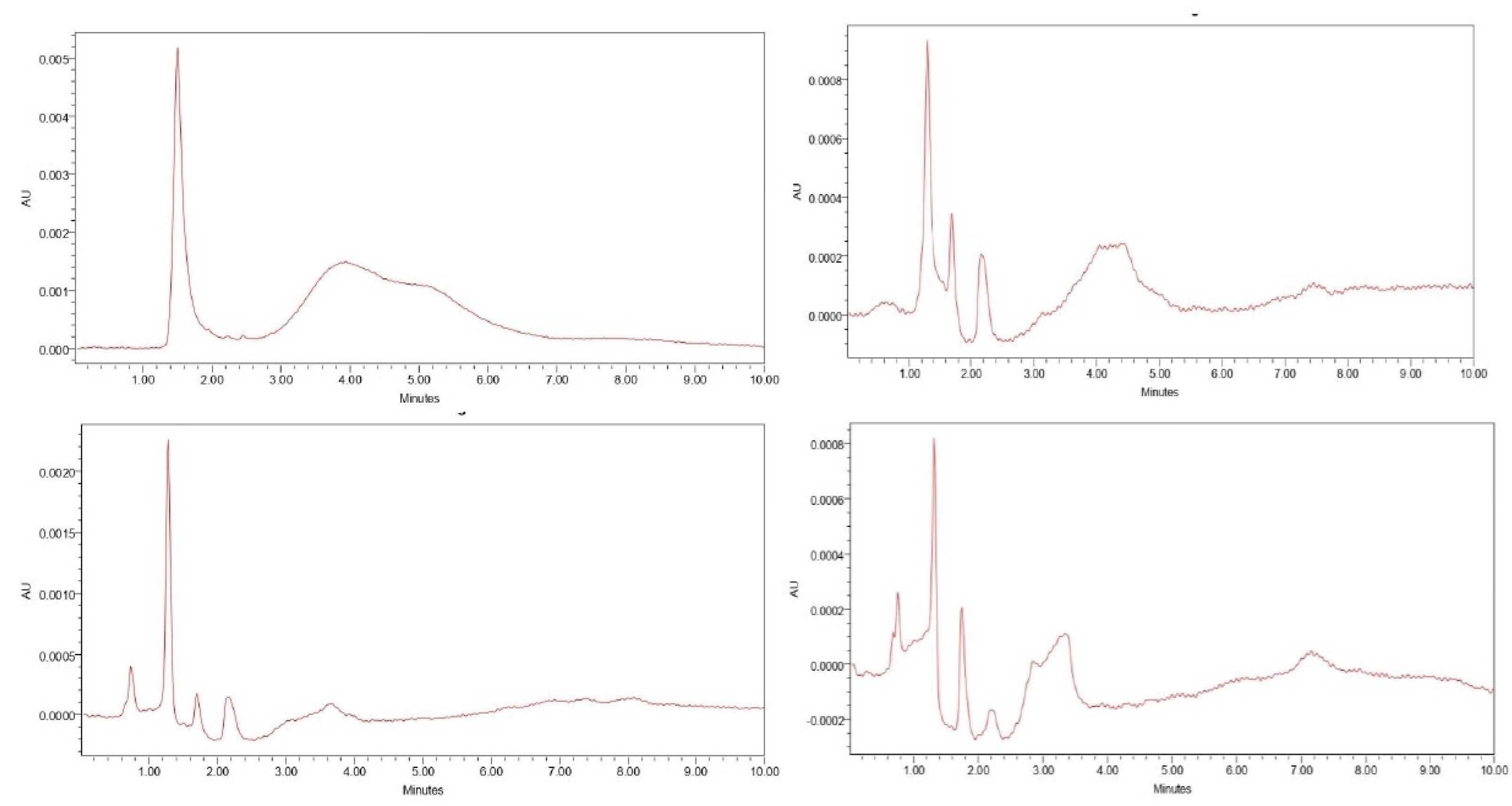

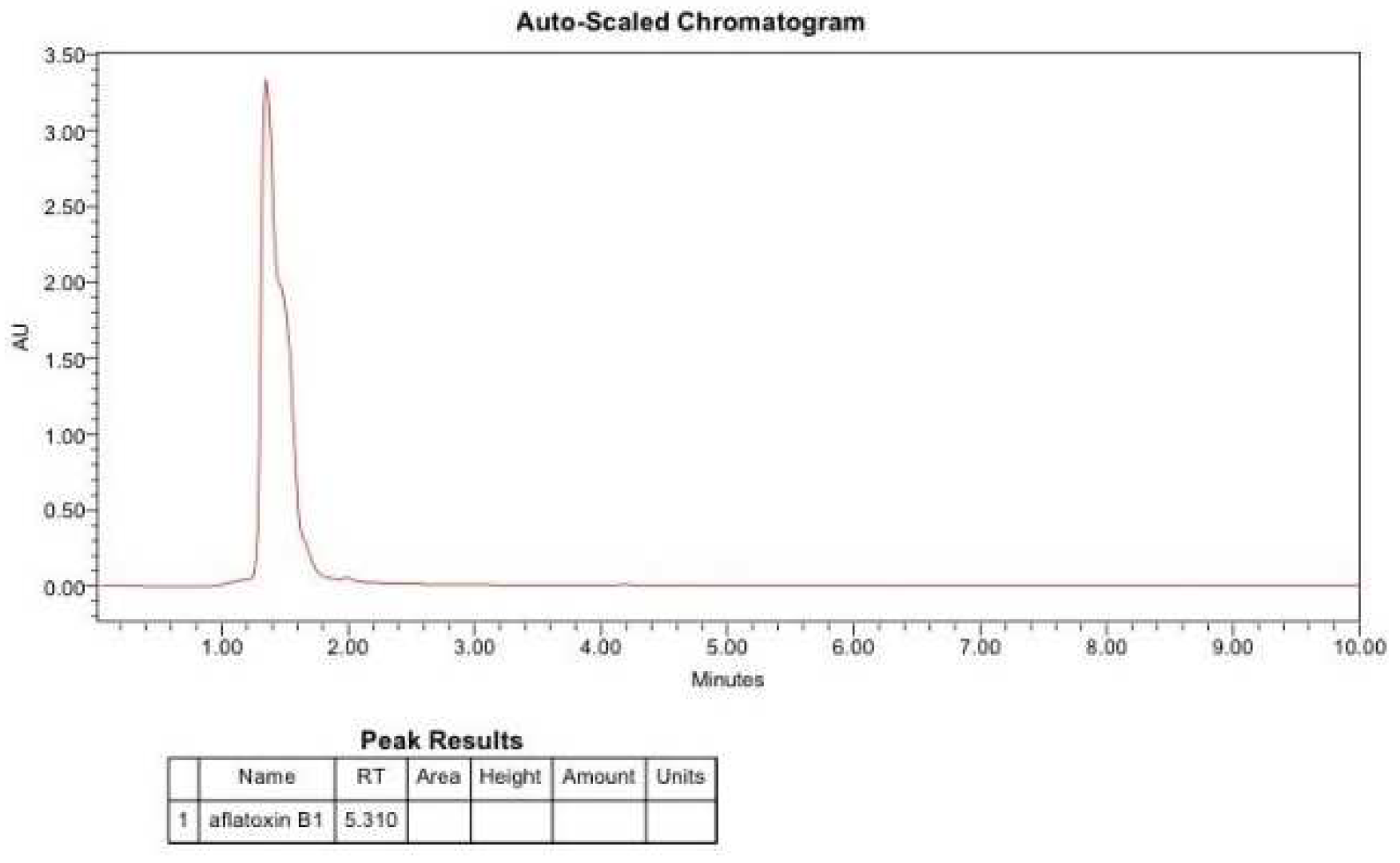

2.7. Detection of Aflatoxin B1 by HPLC

2.8. Organoleptic and Physical–Chemical Studies

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Cytotoxic Activity

3.2. Determination of Antimicrobial and Antifungal Activity

4. Conclusions

Funding

Author’s Contribution

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EC. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L119, 103–157. [Google Scholar]

- ReportLinker. Available online: https://www.reportlinker.com/dataset/bc3b564024b37960eec671aa48900b4f201cf05c (2023).

- Dhanshetty, M.; Elliott, C.T.; Banerjee, K. Decontamination of aflatoxin B1 in peanuts using various cooking methods. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2547–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasas, W.F.O.; Gelderblom, W.C.A.; Shephard, G.S.; Vismer, H.F. Mycotoxins: A global problem. Mycotoxins: Detection Methods, Management, Public Health and Agricultural Trade, 4th ed; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, W.; Ji, N.; Dong, H. Ultraviolet irradiation detoxification of aflatoxins. Trends Food Sci. Amp. Technol. 2015, 42, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, E.D.; Brown, A.E.; Sparks, D.L. A recent review of non-biological remediation of aflatoxin-contaminated crops. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Albores, A.; Veles-Medina, J.; Urbina-Álvarez, E.; Martínez-Bustos, F.; Moreno-Martínez, E. Effect of citric acid on aflatoxin degradation and on functional and textural properties of extruded sorghum. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009, 150, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M.; Jinap, S. Role of sodium hydrosulphite and pressure on the reduction of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in black pepper. Food Control. 2012, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, L.; Geng, H.; Xing, F.; Liu, Y. Detoxification of aflatoxin B1 by H2SO3 during maize wet processing, and toxicity assessmen to fthetrans formation product of aflatoxin B1. Food Control 2022, 131, 108444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesen, J. Detoxification of aflatoxins in groundnut meal. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 1977, 2, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Her, J.Y.; Lee, K.G. Reduction of aflatoxins (B (1), B (2), G (1), and G (2)) in soybean-based model systems. Food Chem. 2015, 189, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, M.; Moraes, A.M.L.; Nishikawa, M.M.; Gatti, M.J.A.; de Alencar, M.V.; Brandão, L.E.; Nóbrega, A. Inactivation of fungi from deteriorated paper materials by radiation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2006, 57, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, F.; Kumar, M.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; Ogunbanwo, T.; Ayanwande, K.B. Bio-detoxification of aflatoxin B1 in artificially contaminated maize grains using lactic acid bacteria. Toxin Rev. 2010, 29, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalli, V.; Kollia, E.; Roidaki, A.; Proestos, C.; Markaki, P. Cistus incanus L. extract inhibits aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus parasiticus in macadamia nuts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, Y.P.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ke, J.; Yao, J.Y. Characterization of tea (Camellia sinensis L.) flower extract and insights into its antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus flavus. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaale, L.D. Comparing the effects of essential oils and methanolic extracts on the inhibition of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus growth and production of aflatoxins. Mycotoxin Res. 2023, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenillas, L.F.; Hernandez, C.; Bailly, S.; Billerach, G.; Durrieu, V.; Bailly, J.D. Role of Polyphenols from the Aqueous Extract of Aloysia citrodora in the Inhibition of Aflatoxin B1 Synthesis in Aspergillus flavus. Molecules 2023, 28, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somai, B.M.; Belewa, V. Aqueous extracts of Tulbaghia violacea inhibit germination of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus conidia. J. Food Prot. 2011, 74, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National. Available online: statisticshttps://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/31/statistic/6 (July, 2023).

- Adoption of Regulations on the Protection of the Territory of the Republic of Kazakhstan from Quarantine Facilities and Non-Indigenous Species. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/B1500012032 (2023).

- Khorasany, S.; Azizi, M.H.; Barzegar, M.; Hamidi, E.Z. A study on the chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oil from Thymus caramanicus, Thymus daenensis and Ziziphora clinopodiaides. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 2016, 3, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, H.; Tahan, V.; Kariman, K. In vitro antibacterial activity of essential oils from Carum copticum and Ziziphora clinopodioides plants against the phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2023, 157, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi, A.R.; Shokri, H.; Minooeianhaghighi, M. Inhibition of aflatoxin production and growth of Aspergillus parasiticus by Cuminum cyminum, Ziziphora clinopodioides, and Nigella sativa essential oils. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyan, X.; Wenhuan, D.; Shuge, T. Phytochemical diversity of Ziziphora clinopodioides Lam. in XinJiang, China. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aliakbarlu, J.; Shameli, F. In vitro antioxidant and antibacterial properties and total phenolic contents of essential oils from Thymus vulgaris, T. kotschyanus, Ziziphora tenuior and Z. clinopodioides. Turk. J. Biochem. /Turk Biyokim. Derg. 2013, 38, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrournia, M.; Shams, A. Elemental determination and essential oil composition of Ziziphora clinopodioides and consideration of its antibacterial effects. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrati, S.; Govahi, M.; Sedaghat, M.; Kashkooli, A.B. A comparative study of essential oil profile, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of two cultivated Ziziphora species (Z. clinopodioides and Z. tenuior). Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 157, 112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, H.D.; Sani, A.M.; Sangatash, M.M. Antifungal activity of essential oil of Ziziphora clinopodioides and the inhibition of aflatoxin B1 production in maize grain. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinezhad, M.; Hojjati, M.; Barzegar, H.; Shahbazi, S.; Askari, H. Effect of gamma irradiation on the physicochemical properties of pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) nuts. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.; Abyavi, T.; Taheri Mirghaed, A.; Payghan, R.; Alishahi, M. Evaluation of Antifungal and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils of Ziziphora clinopodioides, Thymus vulgaris and Salvia rosmarinus to Some Fungal and Bacterial Pathogens of Aquatic Animals. Exp. Anim. Biol. 2023, 11, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

| Parallel | Amount of Nauplii in Monitoring | Amount of Nauplii in the Sample | % of Survived Nauplii in Monitoring | % of Survived Nauplii in the Sample | Case-Fatality Rate, А, %Survived | Neurotoxicity, %Died | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | Died | Survived | Died | par. | |||||

| Ziziphora serpyllácea in concentration of 10 mg/mL | |||||||||

| 1 | 20 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 0 | 95.4 | 85 | 15 | - |

| 2 | 21 | - | 20 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 22 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Avg. | 21 | 1 | 20 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Ziziphora serpyllаcea in concentration of 5 mg/mL | |||||||||

| 1 | 23 | 1 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 95.4 | 87.5 | 29.1 | 12.5 |

| 2 | 20 | - | 25 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 21 | 1 | 21 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Avg. | 21 | 1 | 24 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Ziziphora serpyllаcea in concentration 2.5 mg/mL | |||||||||

| 1 | 23 | 1 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 95.4 | 90.4 | 9.5 | 0 |

| 2 | 20 | - | 24 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 21 | 1 | 20 | - | 0 | ||||

| Avg. | 21 | 1 | 21 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Ziziphora serpyllаcea in concentration 1.0 mg/mL | |||||||||

| 1 | 23 | 1 | 25 | 2 | - | 95.4 | 95.6 | 4.3 | 0 |

| 2 | 20 | - | 22 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 21 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Avg. | 21 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Name | Antibacterial Activity, mm | Antifungal Activity, mm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample code | % |

Staphylococcus aureus |

Sample Code | % |

Staphylococcus aureus |

Sample Code |

| Ziziphora serpyllacea | 5 | 11 ± 0.42 | 12 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 0.51 | 12 ± 0.5 |

| 10 | 18 ± 0.55 | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 16 ± 0.38 | 15 ± 0.2 | 16 ± 0.5 | |

| 20 | 21 ± 0.54 | 20 ± 0.33 | 19.5 ± 0.4 | 19 ± 0.56 | 20 ± 0.6 | |

| Gentamycin | 24 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 0.2 | 26 ± 0.1 | - | ||

| Nystatin | - | - | - | 22 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 0.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).