Submitted:

12 October 2023

Posted:

12 October 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

- Model description

- Calibration

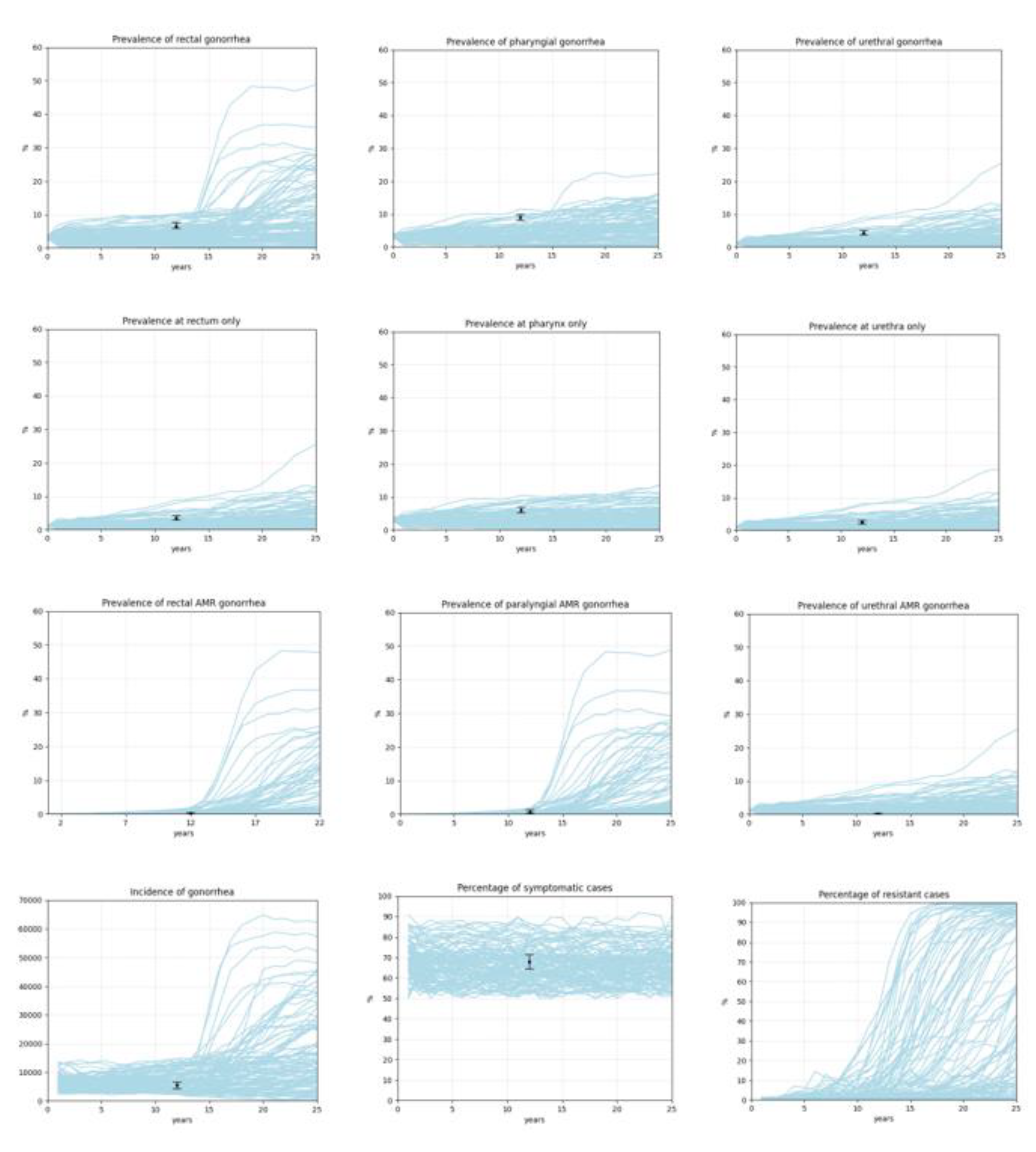

- Incidence of gonorrhea is less than 2000 or greater than 15000.

- Prevalence of rectal gonorrhea is greater than 12%.

- Prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea is greater than 12%.

- Prevalence of urethral gonorrhea is greater than 12%.

- Prevalence of gonorrhea at rectum only is greater than 10%.

- Prevalence of gonorrhea at pharynx only is greater than 12%.

- Prevalence of gonorrhea at urethra only is greater than 10%.

- Prevalence of rectal AMR gonorrhea is greater than 2%.

- Prevalence of pharyngeal AMR gonorrhea is greater than 2%.

- Prevalence of urethral AMR gonorrhea is greater than 2%.

- Percentage of symptomatic cases is less than 50%.

- Surveillance

Results

- 1.

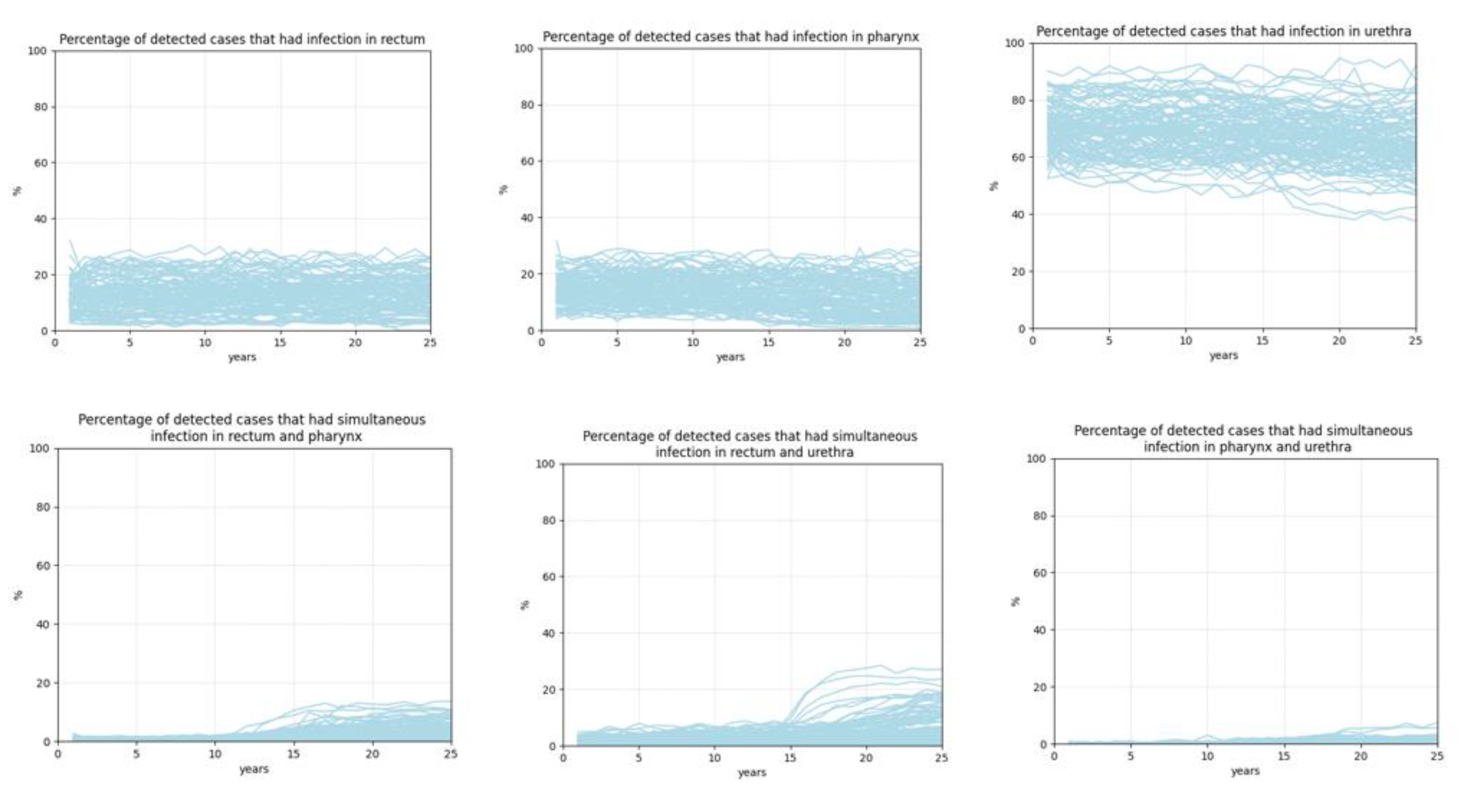

- Calibration results

- 2.

- Surveillance results

Discussion

Acknowledgment

References

- A Dutescu, I.; A Hillier, S. Encouraging the Development of New Antibiotics: Are Financial Incentives the Right Way Forward? A Systematic Review and Case Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Lewis, Will targeting oropharyngeal gonorrhoea delay the further emergence of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains? Sexually transmitted infections 2015, 91, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. A. Chan et al. Extragenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a review of the literature. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- J. C. Dombrowski Chlamydia and gonorrhea. Annals of Internal Medicine 2021, 174, ITC145–ITC160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanis, A.J. Resistance to Antibiotics: Are We in the Post-Antibiotic Era? Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S.; Henderson, I.R.; Capon, R.J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline as of December 2022. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 431–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. f. D. C. a. Prevention, Gonococcal Isolate Surveilance Project (GISP) and Enhanced GISP (eGISP), 2022.

- Spicknall, I.H.; Mayer, K.H.; Aral, S.O.; Romero-Severson, E.O. Assessing Uncertainty in an Anatomical Site-Specific Gonorrhea Transmission Model of Men Who Have Sex With Men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2019, 46, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, L.C.; Fairley, C.K.; Aung, E.T.; Traeger, M.W.; Wright, E.J.; A Stoové, M.; Chow, E.P.F. The Presence or Absence of Symptoms Among Cases of Urethral Gonorrhoea Occurring in a Cohort of Men Taking Human Immunodeficiency Virus Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in the PrEPX Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, J.; Fethers, K.; Howden, B.; Fairley, C.; Chow, E.; Williamson, D.; Petalotis, I.; Aung, E.; Kanhutu, K.; De Petra, V.; et al. Asymptomatic and symptomatic urethral gonorrhoea in men who have sex with men attending a sexual health service. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sánchez, M.; Ong, J.J.; Fairley, C.K.; Chen, M.Y.; Williamson, D.A.; Maddaford, K.; Aung, E.T.; Carter, G.; Bradshaw, C.S.; Chow, E.P.F. Clinical presentation of asymptomatic and symptomatic heterosexual men who tested positive for urethral gonorrhoea at a sexual health clinic in Melbourne, Australia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, C.K.; Chaw, J.K.; Wong, W.; Liska, S.; Gibson, S.; Hubbard, G.; Klausner, J.D. Prevalence of Rectal, Urethral, and Pharyngeal Chlamydia and Gonorrhea Detected in 2 Clinical Settings among Men Who Have Sex with Men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. H. Handsfield et al., Asymptomatic gonorrhea in men: diagnosis, natural course, prevalence and significance. New England Journal of Medicine 1974, 290, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. M. Wall, R. Stephenson, and P. S. Sullivan Frequency of sexual activity with most recent male partner among young, Internet-using men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Homosexuality 2013, 60, 1520–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Carmody, C.; Donovan, B.; Guy, R.J.; Hui, B.B.; Kaldor, J.M.; Lahra, M.M.; Law, M.G.; Lewis, D.A.; Maley, M.; et al. Modelling response strategies for controlling gonorrhoea outbreaks in men who have sex with men in Australia. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gonorrhoea/treatment/#:~:text=It's%20sometimes%20possible%20to%20have,or%20testicles%20to%20disappear%20completely.

- S. S. Cyr et al., Update to CDC's treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020, 69, 1911. [CrossRef]

- Quilter, L.A.S.; Cyr, S.B.S.; Hong, J.; Asbel, L.; Bautista, I.; Carter, B.M. (.; Casimir, Y.A.; Denny, M.; Ervin, M.M.; Gomez, R.M.; et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Urogenital and Extragenital Neisseria gonorrhoeae Isolates Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: Strengthening the US Response to Resistant Gonorrhea and Enhanced Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 2018 to 2019. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, S111–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. L. J. Jones et al., Extragenital chlamydia and gonorrhea among community venue–attending men who have sex with men—five cities, United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2019, 68, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, L.M.; Dowell, D.; Bernstein, K.; Donnelly, J.; Martins, S.; Stenger, M.; Stover, J.; Weinstock, H. A Tale of Two Gonorrhea Epidemics: Results from the STD Surveillance Network. Public Heal. Rep. 2012, 127, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. f. D. C. a. Prevention, Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2017.

- Yaesoubi, R.; Cohen, T.; Hsu, K.; Gift, T.L.; Cyr, S.B.S.; Salomon, J.A.; Grad, Y.H. Evaluating spatially adaptive guidelines for the treatment of gonorrhea to reduce the incidence of gonococcal infection and increase the effective lifespan of antibiotics. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1009842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersh, E.N.; Pham, C.D.; Papp, J.R.; Myers, R.; Steece, R.; Kubin, G.; Gautom, R.; Nash, E.E.; Sharpe, S.; Gernert, K.M.; et al. Expanding U.S. Laboratory Capacity for Neisseria gonorrhoeae Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Whole-Genome Sequencing through the CDC's Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. f. D. C. a. Prevention, Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2020, 2020.

- V. B. Bowen et al., “Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018,” 2019.

- Earnest, R.; Rönn, M.M.; Bellerose, M.B.; Gift, T.L.; Berruti, A.A.; Hsu, K.K.; Testa, C.B.; Zhu, L.; Malyuta, Y.; Menzies, N.A.; et al. Population-level Benefits of Extragenital Gonorrhea Screening Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: An Exploratory Modeling Analysis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2020, 47, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

| p | M, m | Data | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of rectal gonorrhea | 5458, 223 | 6.49% [5.9%, 7.6%] | [12,19] |

| Prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea | 5507, 309 | 9% [8.1%; 10%] | [12,19] |

| Prevalence of urethral gonorrhea | 3435, 148 | 4.31% [3.7%; 5%] | [12] |

| Prevalence of gonorrhea at rectum only | 3435, 121 | 3.52% [3%; 4.2%] | [12] |

| Prevalence of gonorrhea at pharynx only | 3435, 209 | 6% [5.3%; 6.9%] | [12] |

| Prevalence of gonorrhea at urethra only | 3435, 86 | 2.5% [2%; 3.1%] | [12] |

| Prevalence of rectal AMR gonorrhea | 1553, 2 | 0.13% [0.03–0.51] | [18] |

| Prevalence of pharyngeal AMR gonorrhea | 1049, 7 | 0.67% [0.32–1.4] | [18] |

| Prevalence of urethral AMR | 3974, 7 | 0.18% [0.08–0.37] | [18] |

| Percentage of symptomatic cases | 686, 466 | 67.9% [64.4%, 71.4%] | [20] |

| Incidence of gonorrhea | 1736, 91 | 5241.8 (4193, 6290) | [21] |

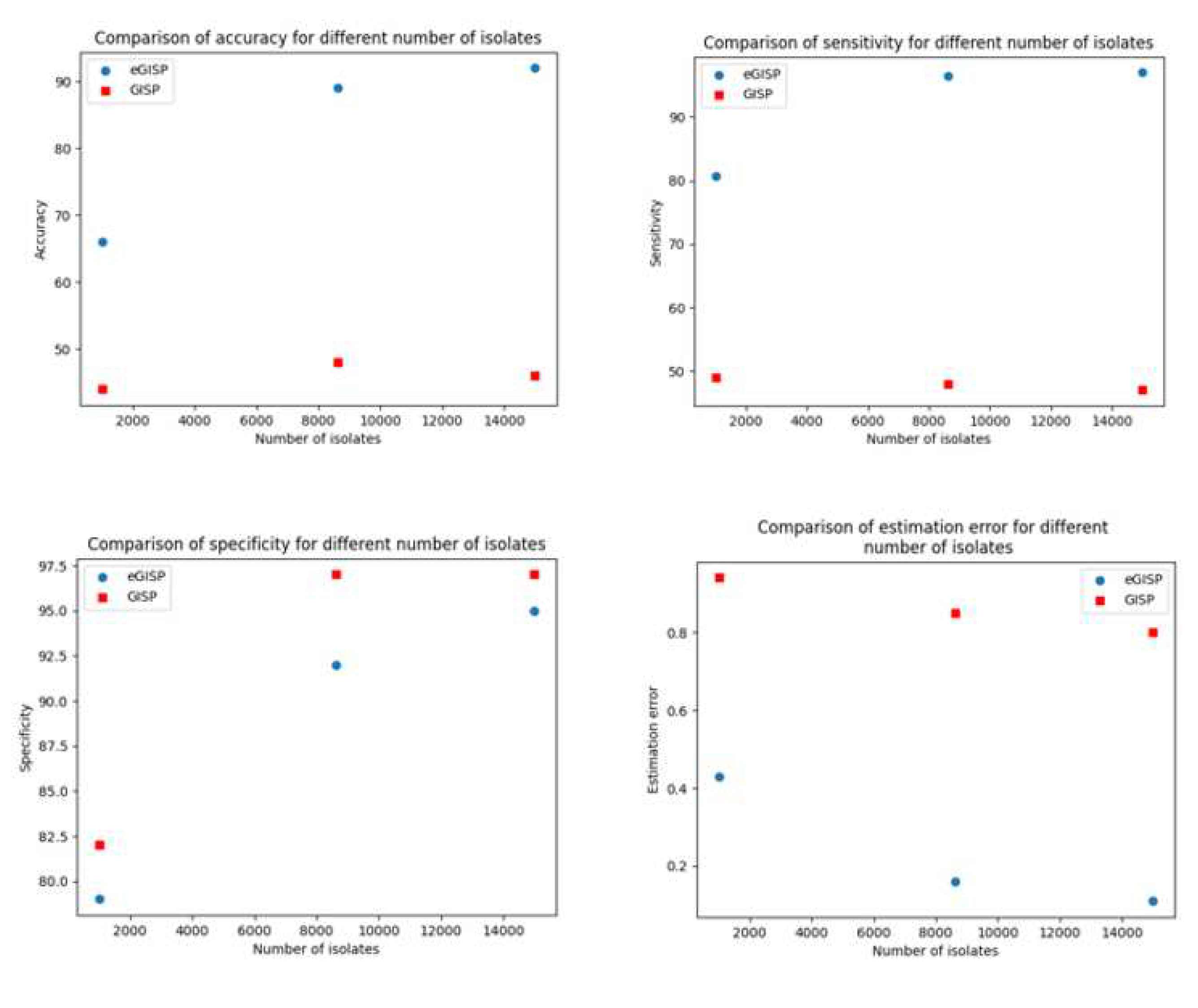

| Simulation experiment | Average time when percentage resistant reaches 5% (years) | Average time when 5% percentage resistant is detected (years) | Estimation error (years) | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real life | 15.4 (8.1, 24) | |||||

| eGISP | 15.3 (7, 24) | 0.16 (0, 2) | 89 | 96.5 | 92 | |

| GISP | 16.24 (8.1, 24) | 0.85 (0, 3.4) | 48 | 48 | 97 |

| Simulation experiment | Average time when percentage resistant reaches 5% (years) | Average time when 5% percentage resistant is detected (years) | Estimation error (years) | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real life | 15.4 (8.1, 24) | |||||

| eGISP | 15.35 (7, 24) | 0.43 (0, 2) | 66 | 80.7 | 79 | |

| GISP | 16 (7, 24.4) | 0.94 (0, 3.4) | 44 | 49 | 82 |

| Simulation experiment | Average time when percentage resistant reaches 5% (years) | Average time when 5% percentage resistant is detected (years) | Estimation error (years) | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real life | 15.4 (8.1, 24) | |||||

| eGISP | 15.38 (7, 24) | 0.11 (0, 1.4) | 92 | 97 | 95 | |

| GISP | 16.2 (8.1, 24) | 0.8 (0, 3.4) | 46 | 47 | 97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).