1. Introduction

As the worldwide population ages, neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), are rapidly becoming more prevalent; however, AD diagnosis remains challenging [1-3]. Since the revised guideline was published in 2011, medial temporal lobe atrophy (MTA) has been considered and used as an essential imaging biomarker in brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis framework for AD [4-6].

Therefore, the visual grading of the MTA score including the atrophic change of the hippocampus represented by Scheltens' scale, has been a significant biomarker for diagnosing AD [

7]. This scale showed moderate-to-good interobserver agreement and reproducibility among reviewers [8-10]. However, it is sensitive to the clinician's experience and perspective [

11,

12]. Therefore, to overcome the potential shortness of qualitative measurement, various commercial volumetry software have been developed. These software can aid in quantifying MTA and providing an age-appropriate percentile based on a normative database. For example, NeuroQuant® (version 3.0.1, CorTechs Labs Inc., California, USA) and Aqua® (version 2.0.0, NEUROPHET Inc., Seoul, Korea) are volumetry software. NeuroQuant® is one of the world's most validated volumetry software [

13]; however, Aqua® remains unvalidated in clinical settings. Hence, performance regarding MTA for diagnosing AD should be assessed to help clinicians choose suitable volumetry software because the normative database varies among different software [4,14-16].

Therefore, we aimed to compare the performance of NeuroQuant® and Aqua® in detecting significant MTA in non-AD and AD groups. Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between the calculated mean quantitative hippocampal volume of each software and Scheltens' scale.

2. Materials and methods

This retrospective study was approved by our hospital's institutional review board and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki's principles (Protocol number, PC21RESI0174; approval date, 11 November 2021).

2.1. Sample Eligibility

Between January and August 2021, 203 individuals who underwent brain MRI and visited the neurology or neuropsychiatry departments of our hospital's neuroscience center for subjective memory impairment or transferred from a community mental health center were enrolled as potentially eligible participants. The sample size was estimated based on the previous study and is summarized in Appendix E1 [

17].

2.2. Clinical Diagnosis for AD

To determine whether participants had AD, clinical evaluations were conducted using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Two dementia specialists (one neurologist and one neuropsychiatrist with over 10 years of clinical experience in diagnosing AD) diagnosed and classified the disease groups, including subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and AD based on the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the 2011 edition of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association [

6,

18]. Two clinicians classified participants with SCI and MCI into a non-AD group and the other participants with AD into an AD group.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

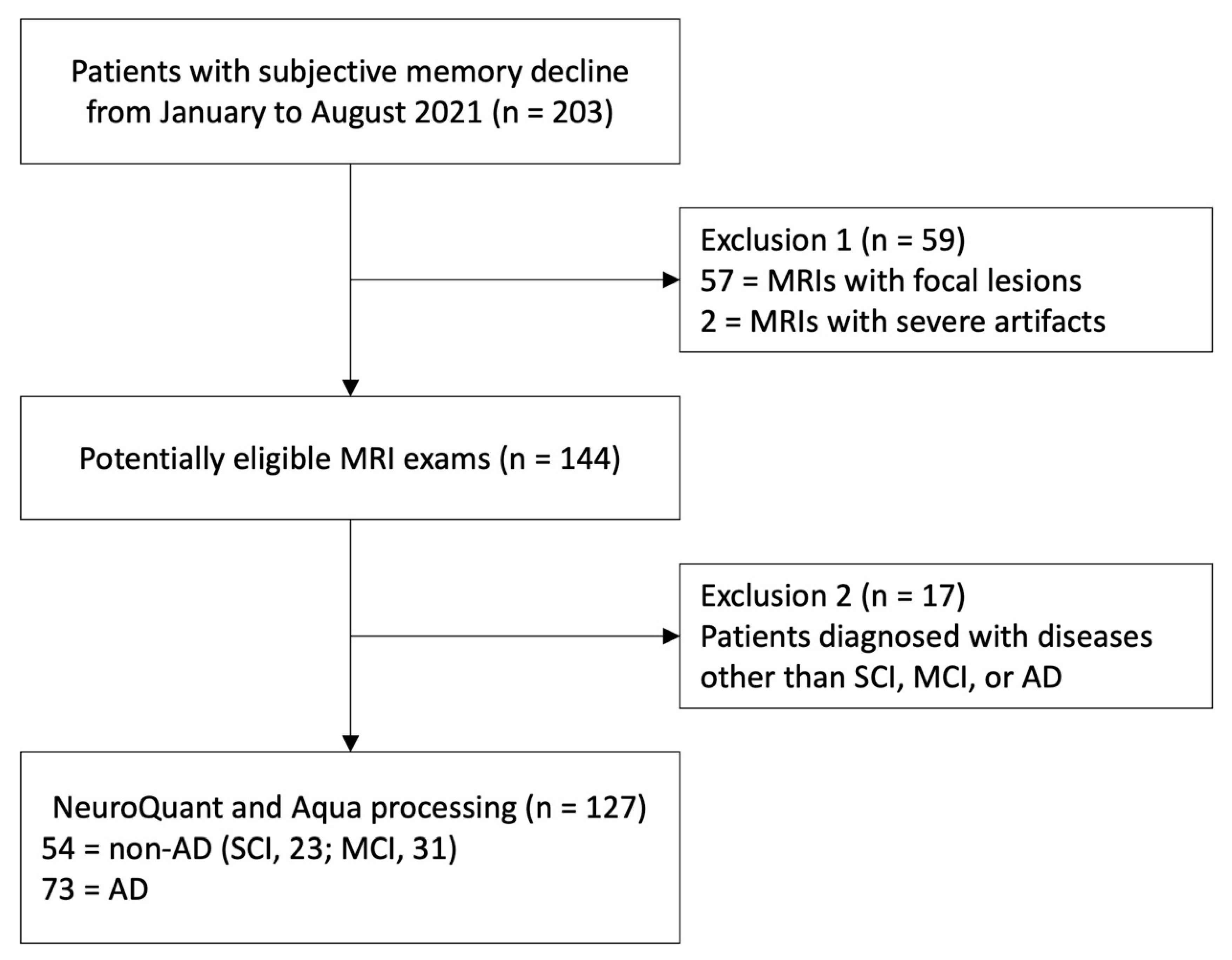

Three neuroradiologists (J.K., S.-W.O., and J.-Y.K. with 8, 17, and 21 years of interpreting brain MRI experience) reviewed all MRI scans and excluded 59 samples that presented focal brain lesions or severe artifacts, which could interfere with the volumetry analyses of each software. Similarly, 17 samples were excluded because clinicians diagnosed the patients with diseases other than SCI, MCI, or AD.

2.4. MRI Acquisition Protocol

Each participant underwent a 3T MRI using a 64-channel head & neck coil (MAGNETOM Vida 3T, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Similarly, three-dimensional (3D) T1-weighted volumetric magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo images were obtained with the following parameters: repetition time, 2090 ms; echo time, 3 ms; inversion time, 1200 ms; number of excitations, 1; section thickness, 1.0 mm; gap, 1.0 mm; matrix size, 256 × 230; flip angle, 9°; and field of view, 250 × 250 mm.

2.5. Volumetry Procedure

All MRI scans were analyzed using NeuroQuant® and Aqua® volumetry software. Each participant underwent one MRI examination including sagittal volumetric T1-weighted imaging, and the obtained images were uploaded to separate NeuroQuant® and Aqua® servers for automated volumetry analyses. After completing the analyses, the volumetry results of each software were returned to the picture archiving and communicating system of our hospital. The system displayed the volume, volume percentile based on the normative database, the proportion of volume to the total intracranial volume of brain substructure, and colored images of each software. More detailed volumetry analysis steps and examples of colored images of NeuroQuant® and Aqua® are described in Appendix E2 and Supplemental

Figure 1. The cutoff of significant MTA was defined as

<5% of the normative percentile.

2.6. Gold Standard for Significant MTA

All MRI examinations were reviewed by three neuroradiologists (J.K., S.-W.O., and J.-Y.K.). For hippocampal volume assessment, the 3D volumetric T1-weighted images were reconstructed into a coronal view perpendicular to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line [

19]. All reviewers were blinded to patients' history, clinical diagnosis, results of volumetry software, and other reviewers. MTA scoring was conducted according to Scheltens' 5-point Likert scale (0–4) based on assessing the width of the choroid fissure, the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle, and the height of the hippocampus [

7]. Similarly, reviewers reported that individuals aged <75 years with an MTA score >2 and those aged

>75 years with an MTA score

>3 had significant MTA [

7]. Consensus was made if there was a disagreement among reviewers.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

First, for comparing detection performance for significant MTA between NeuroQuant® and Aqua®, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were compared using the Chi-square test, defining the non-inferior margin as 0.05. A non-inferior test was performed for detection performance between the two software. We defined a -0.05 or -5% difference as a non-inferiority margin through consensus among participants' neuroradiologists, considering previous studies [

20,

21]. Second, for assessing the correlation between Scheltens' scale and the quantitative mean hippocampal volume of each software, Kendall's τ correlation was used. Additional inter-reviewer agreement among three reviewers was calculated using Fleiss' Kappa analyses with 95% CI. The Kendall's τ correlation coefficients, Kappa values with 95% CI were defined as follows: weak, <0.3; moderate, 0.3 ≤ and <0.7; and strong, ≥0.7. The baseline characteristics between non-AD and AD groups were compared using Student's t-test.

The statistics of sub-analysis for the mean volume comparison and inter-method reliability of each software is described in Appendix E3.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc (version 20.215, MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). P-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

A total of 127 participants (mean age, 78.57±7.01 years; 38 men; 89 women) were enrolled. The number of non-AD (SCI, 23; MCI, 31) and AD were 54 (43%) and 73 (57%), respectively. The flow diagram of participants' enrollment is displayed in

Figure 1. Participants in the AD group had significantly older ages with lower K-MMSE and higher CDR scores than those in the non-AD group (P<0.01). The baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Comparing Detecting Performance for the Significant MTA

The overall accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of NeuroQuant® for detecting significant MTA were as follows: accuracy, 83.5 (95% CI, 77.2–90.0)%; sensitivity, 72.2 (95% CI, 60.3–84.2)%; and specificity, 83.8 (95% CI, 77.6–90.1)%. Aqua® had the following: accuracy, 87.4 (95% CI, 81.8–93.0)%; sensitivity, 72.2 (95% CI, 60.3–84.2)%; and specificity, 95.6 (92.1–99.1)%. Aqua® showed higher specificity and accuracy than NeuroQuant®; however, only specificity showed statistical significance. NeuroQuant® and Aqua® values differed insignificantly in the non-AD and AD groups. As the lower boundary of the CIs of accuracy (3.9%, 3.0–4.6%) and specificity (11.8%, 9.0–14.5%) were above the predefined non-inferiority margin, the non-inferiority of Aqua® was established after comparison with the NeuroQuant® in the non-AD and AD groups. However, Aqua® was not demonstrated to be non-inferior to NeuroQuant® regarding sensitivity. Similar results of the overall population, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of the non-AD and AD groups showed non-inferiority of Aqua® to NeuroQuant® except for sensitivity in the AD group. The detailed results are presented in

Table 2. The Kappa value for MTA among three reviewers was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.86–0.92; P<0.01), indicating strong inter-reviewer agreement.

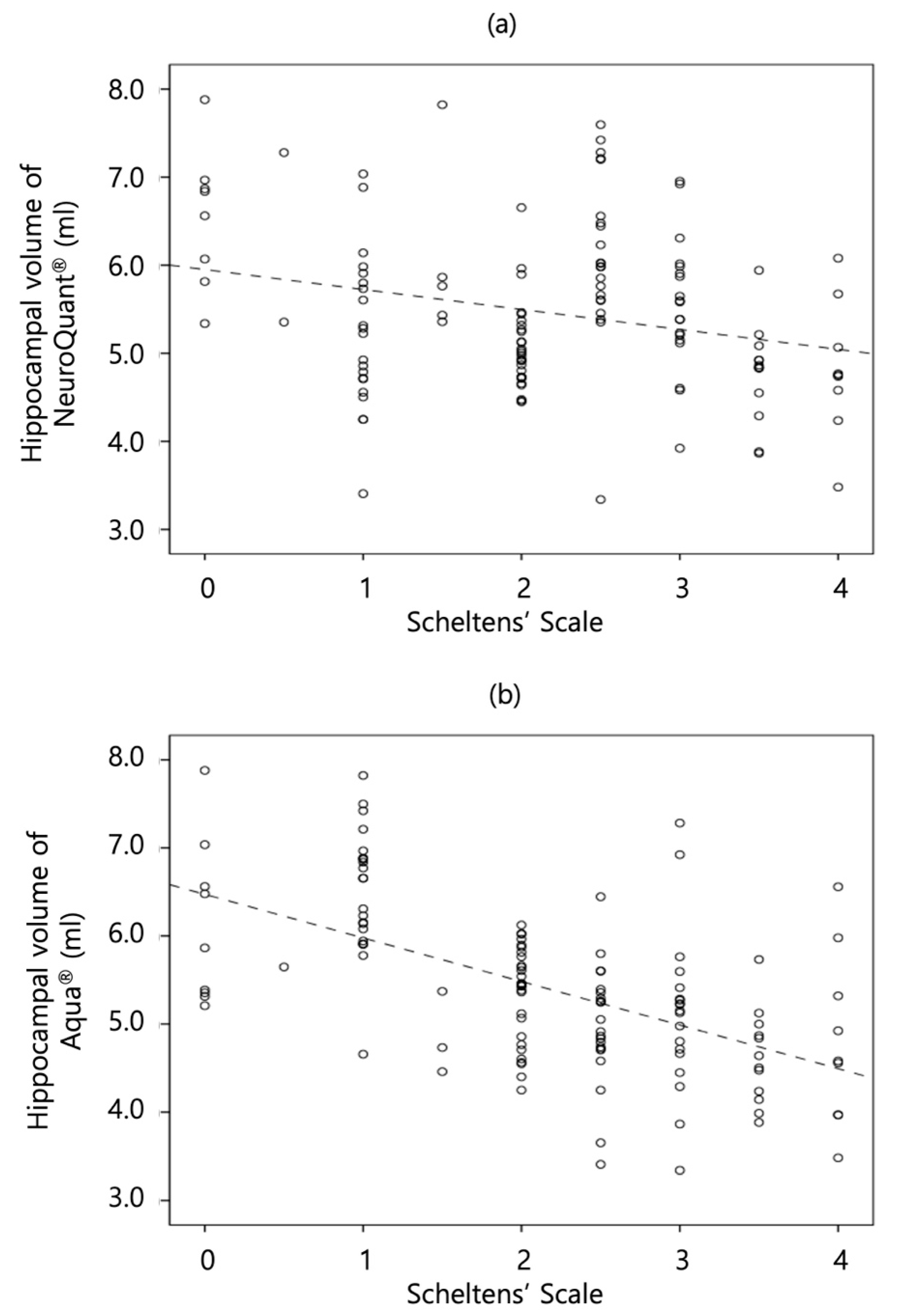

3.3. Correlation of Mean Volume with Scheltens’ Scale

The correlations between Scheltens’ scale and quantitative mean hippocampal volume were analyzed using each software. The correlation between Scheltens’ scale and NeuroQuant® showed a negatively weak correlation with statistical significance in the AD group (τ, - 0.20; P=0.02); however, the correlation was statistically insignificant in the non-AD group. The correlation between Scheltens’ scale and Aqua® showed a negatively moderate correlation with statistical significance in the non-AD (τ, - 0.35; P<0.01) and AD (τ, - 0.49; P<0.01) groups. All the τ of Aqua® in each group were significantly more correlated than those of NeuroQuant®. The scatterplot graphs are illustrated in

Figure 2, and the results are summarized in

Table 3.

3.4. Sub-analysis for Mean Volume Comparison and Inter-method Reliability

The sub-analysis comparing mean hippocampal volumes indicated that Aqua® was significantly larger than NeuroQuant® regardless of clinical diagnosis. The inter-method reliability of mean quantitative hippocampal volume between the two software was moderate-to-strong in the non-AD and AD groups. The statistics and detailed results of the other brain regions are described in Appendix E3 and Table E1.

4. Discussion

Aqua® and NeuroQuant® were compared in two ways in this study. In the former way, the comparison detecting performance for significant MTA, our results demonstrated that Aqua® showed significantly higher specificity than NeuroQuant®. Furthermore, detection accuracy and specificity were comparable between the two software according to a non-inferiority test in the non-AD and AD groups.

In the latter way, the correlation between Scheltens' scale and each software’s calculated mean hippocampal volumes demonstrated that NeuroQuant® showed a weak correlation; however, Aqua® showed a moderate correlation with Scheltens' scale, with a significant difference. This result is inconsistent with those of previous studies, which showed a more than moderate correlation of NeuroQuant® with Scheltens’ scale [

22,

23]. However, our sample has a larger number, and the gold standard was established by three neuroradiologists. Similarly, our mean MTA score and incidence of abnormal MTA were within the range of those in previous studies [7,17,22-24]. Therefore, our results are reasonable and more robust than those of previous studies. Considering that we did not aim to validate but compare two volumetry software, these results should be interpreted as Aqua® being more correlated with Scheltens' scale than NeuroQuant®. Visual assessment of MTA is essential for dementia work-up. Thus, Aqua® could be used by clinicians for monitoring the AD [

5].

In sub-analysis for mean volume comparison, there was a significant hippocampal volume difference between both software with moderate to strong inter-method reliability. The hippocampus and most of the brain regions showed significant volume differences. There could be variable reasons for volume discrepancies between the two software. Different baseline anatomic atlases between NeuroQuant® and Aqua® could be a cause because NeuroQuant® and Aqua® were developed with the Talairach atlas and the Desikan–Killiany cortical atlas, respectively [25-27]. For example, the hippocampus has different anatomical definitions across the software. In the process of developing and establishing the gold standard through manual segmentation, different anatomical boundaries and tracing procedures can provide potential volume differences [

28]. Similarly, different software applications involve using different algorithms to segment brain regions, which can cause variations in regional volume measurements [

17,

29,

30]. Therefore, for clinicians, these factors could complicate the selection of a suitable volumetry software for acquiring a quantitative volume of brain substructure.

NeuroQuant® is one of the most validated volumetry software with good ability for brain volumetry [

13,

17]. To our knowledge, this study would be the first clinical study on Aqua® since the introduction of the software. However, the overall performance of Aqua® for detecting significant MTA and correlation with Scheltens' scale was not inferior to that of NeuroQuant® in our study. Because the brain morphology of the aging population could be affected by ethnicity owing to the geographic environment, implementation of a normative reference database could be a substantial factor for our results [

16,

27].

This study has some limitations. First, because of the study’s retrospective nature, there could be a selection bias. However, it was an inevitable limitation owing to the nature of the study design. Second, since a cutoff of 5% was used for significant MTA of each software, there could be variations in the detection performances when different cutoff values were used. Finally, although the specificity of Aqua® for significant MTA and correlation with Scheltens' scale were superior to those of NeuroQuant®, these results not indicate that Aqua® had better performance than NeuroQuant® for the other regions. Therefore, further comprehensive study would be required to generalize the performance of Aqua®, and clinicians should consider these limitations when selecting the volumetry software and interpreting the results.

5. Conclusions

The accuracy of Aqua® was not inferior to that of NeuroQuant® in detecting MTA. Similarly, Aqua® was significantly more correlated to the calculated hippocampal volume than NeuroQuant®. Therefore, Aqua® could be considered an alternative volumetry option and could aid clinicians in determining MTA.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (a) T1-weighted MR images show conventional axial images at the basal ganglia level; (b) color-coded images of NeuroQuant®; and (c) those of Aqua®.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jee Young Kim. and Se Won Oh.; Data curation, Jimin Kim. Jee Young Kim.; Formal analysis, Jimin Kim. and Se Won Oh.; Investigation, Jimin Kim. and Jee Young Kim.; Methodology, Jimin Kim. and Se Won Oh.; Project administration, Jee Young Kim. and Se Won Oh.; Supervision, Se Won Oh.; Validation, Jimin Kim. and Se Won Oh.; Visualization, Jimin Kim., Regina EY Kim and Donghyeon Kim.; Writing—original draft, Jimin Kim.; Writing—review and editing, Jimin Kim., Jee Young Kim. and Se Won Oh.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was approved by our hospital's institutional review board and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki's principles (Protocol number PC21RESI0174, approval date 11 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

The institutional review board of our hospital has waived the requirement for informed consent due to its retrospective study design.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are unavailable due to privacy and ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the research support center of Eunpyeong St. Mary's Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose. R.E.K. and D.K. are employees of the Research Institute of NEUROPHET Inc., but they have no role in the study design, data collection, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix E1. Calculation of Sample Size

The sample size for the two-tailed Student's t-test was calculated using the common formula for calculating sample sizes for proportions. Based on a statistical power level of 0.80 and a statistical significance level of 0.05, we estimated the sample size. Similarly, based on previous studies, the impact size was conservatively established at 0.5 [

1]. The sample size for this study was calculated to be 128.

Appendix E2. Volumetry Process Steps of NeuroQuant® and Aqua®

NeuroQuant® is a spin-off of FreeSurfer, a software with a research focus used for volumetry. The steps in the NeuroQuant® process were as follows: the process involves removing the scalp, skull, and meninges, expanding the brain into a sphere, mapping that sphere to a shared space using the Talairach atlas coordinates, identifying the segmented brain areas, and contracting the brain back to its original shape [

1].

Similarly, Aqua® is built on FreeSurfer using Split-Attention U-Net, a convolutional neural network with skip routes and a split-attention module that separates brain MRI images. Two open sources and three research sites provided a wide variety of cognitively normal East Asian populations' normative MRI data (age, 18–96 years). The 97 different regions of the brain are divided using Aqua®, which is used to examine structural details, such as atrophy, structural alterations, anatomical asymmetry, and white matter abnormalities associated with degenerative brain illnesses. The segmentation of the central nuclei, hippocampus, brainstem, and ventricles; lobar parcellation; and the detection of white matter abnormality. The process steps of Aqua® included skull stripping, a tissue classification to extract brain tissue compartments, such as the white matter, gray matter, and intra/extra ventricular cerebrospinal fluid [

2,

3].

Appendix E3. Mean Volume Comparison and Inter-method Reliability

We categorized study samples into three groups according to clinical diagnoses by two clinicians: subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer's disease (AD) groups. We compared the mean volume of brain substructures between the two software using the paired t-test. Considering clinical diagnosis, most brain regions showed significant differences in mean volume except for the parietal lobe in the AD group and the frontal lobe and caudate nucleus in the SCI group, the white matter, parietal lobe, caudate nucleus, and cingulate gyrus in the MCI group. Intracranial volume, cortical gray matter, white matter of AD group, parietal lobe, hippocampus, amygdala, caudate nucleus, globus pallidum, and cerebellum were larger in Aqua® than NeuroQuant®. The other regions exhibited the reverse results.

Furthermore, we assessed the inter-method reliability between the two software using Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). Pearson's correlation coefficient and ICC with a 95% confidence interval were defined thus: weak, <0.3; moderate, 0.3 ≤ and < 0.7; strong, ≥0.7. Most brain regions exhibited statistically significant values regardless of the clinical diagnosis, except for the caudate nucleus and accumbens of the SCI group and the cingulate gyrus and globus pallidum of the MCI group. These significant regions showed moderate to strong linear correlations across all groups (r=0.35–0.98). Most brain regions without group classification demonstrated moderate to strong inter-method agreement (ICC=0.45–0.96). Considering clinical diagnosis, the accumbens and globus pallidum of the SCI group and the cingulate gyrus and globus pallidum of the MCI group showed statistically insignificant values. On excluding these data, most brain regions showed moderate to strong inter-method agreement (ICC=0.37–0.97). These results of the mean volume comparison and inter-method reliability between the two software are summarized in Table E1.

References

- Matthews, K.A.; Xu, W.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B.; Mack, D.; McGuire, L.C. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged >/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement 2019, 15, 17-24, doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Hou, N.; Han, F.; Liu, Y. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990–2019. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 14, 937486. [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.S.; Kim, H.-K.; Han, K.; Kwon, H.-S.; Na, H.K.; Lyoo, C.H.; Cho, H. Annual trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13, 883549. [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, A.; De Stefano, N. Clinical use of brain volumetry. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2013, 37, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sarazin, M.; de Souza, L.C.; Lehéricy, S.; Dubois, B. Clinical and research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2012, 22, 23-32,viii, doi:10.1016/j.nic.2011.11.004. [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011, 7, 263-269, doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Leys, D.; Barkhof, F.; Huglo, D.; Weinstein, H.C.; Vermersch, P.; Kuiper, M.; Steinling, M.; Wolters, E.C.; Valk, J. Atrophy of medial temporal lobes on MRI in "probable" Alzheimer's disease and normal ageing: diagnostic value and neuropsychological correlates. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992, 55, 967-972, doi:10.1136/jnnp.55.10.967. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Pasquier, F.; Weerts, J.G.; Barkhof, F.; Leys, D. Qualitative assessment of cerebral atrophy on MRI: inter- and intra-observer reproducibility in dementia and normal aging. Eur Neurol 1997, 37, 95-99, doi:10.1159/000117417. [CrossRef]

- Sarria-Estrada, S.; Acevedo, C.; Mitjana, R.; Frascheri, L.; Siurana, S.; Auger, C.; Rovira, A. Reproducibility of qualitative assessments of temporal lobe atrophy in MRI studies. Radiologia 2015, 57, 225-228, doi:10.1016/j.rx.2014.04.002. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Launer, L.J.; Barkhof, F.; Weinstein, H.C.; van Gool, W.A. Visual assessment of medial temporal lobe atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging: interobserver reliability. J Neurol 1995, 242, 557-560, doi:10.1007/bf00868807. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Cavallin, L.; Spulber, G.; Aguilar, C.; Mecocci, P.; Vellas, B.; Tsolaki, M.; Kłoszewska, I.; Soininen, H.; Spenger, C. Influence of age, disease onset and ApoE4 on visual medial temporal lobe atrophy cut-offs. Journal of internal medicine 2014, 275, 317-330. [CrossRef]

- Ten Kate, M.; Barkhof, F.; Boccardi, M.; Visser, P.J.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Lovblad, K.O.; Frisoni, G.B.; Scheltens, P. Clinical validity of medial temporal atrophy as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease in the context of a structured 5-phase development framework. Neurobiol Aging 2017, 52, 167-182.e161, doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.05.024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.E.; Chung, M.S.; Oh, S.W.; Moon, W.J. [Expert Opinions and Recommendations for the Clinical Use of Quantitative Analysis Software for MRI-Based Brain Volumetry]. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi 2021, 82, 1124-1139, doi:10.3348/jksr.2020.0174. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Beadnall, H.N.; Hatton, S.N.; Bader, G.; Tomic, D.; Silva, D.G.; Barnett, M.H. Automated brain volumetrics in multiple sclerosis: a step closer to clinical application. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016, 87, 754-757, doi:10.1136/jnnp-2015-312304. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Moon, W.J.; Jeon, J.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Moon, Y.S.; Han, S.H. Diagnostic Efficacy of Structural MRI in Patients With Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer Disease: Automated Volumetric Assessment Versus Visual Assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 208, 617-623, doi:10.2214/ajr.16.16894. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Choi, U.S.; Seo, E.H.; Choo, I.H.; Kim, H.; Song, M.K.; Choi, S.M.; Cho, S.H.; et al. Multi-Racial Normative Data for Lobar and Subcortical Brain Volumes in Old Age: Korean and Caucasian Norms May Be Incompatible With Each Other(†). Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 675016, doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.675016. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Oh, S.W.; Chung, M.S.; Park, J.E.; Moon, Y.; Jeon, H.J.; Moon, W.J. Clinically Available Software for Automatic Brain Volumetry: Comparisons of Volume Measurements and Validation of Intermethod Reliability. Korean J Radiol 2021, 22, 405-414, doi:10.3348/kjr.2020.0518. [CrossRef]

- Vahia, V.N. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 2013, 55. [CrossRef]

- Wahlund, L.-O.; Julin, P.; Johansson, S.-E.; Scheltens, P. Visual rating and volumetry of the medial temporal lobe on magnetic resonance imaging in dementia: a comparative study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2000, 69, 630-635. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Volkers, P.; Day, S. An introductory note to CHMP guidelines: choice of the non-inferiority margin and data monitoring committees. Statistics in medicine 2006, 25, 1623-1627. [CrossRef]

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; Jagsi, R.; Jayasekera, J.; Stout, N.K.; Mitchell, S.A.; Feuer, E.J. Evidence-based sizing of non-inferiority trials using decision models. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2019, 19, 3, doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0643-2. [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.; Barca, M.L.; Cavallin, L.; Brækhus, A.; Knapskog, A.-B.; Selbæk, G.; Engedal, K. Comparison of automated volumetry of the hippocampus using NeuroQuant® and visual assessment of the medial temporal lobe in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Radiologica 2018, 59, 997-1001. [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.; Barca, M.L.; Cavallin, L.; Brækhus, A.; Knapskog, A.B.; Selbæk, G.; Engedal, K. Comparison of automated volumetry of the hippocampus using NeuroQuant® and visual assessment of the medial temporal lobe in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Radiol 2018, 59, 997-1001, doi:10.1177/0284185117743778. [CrossRef]

- Molinder, A.; Ziegelitz, D.; Maier, S.E.; Eckerström, C. Validity and reliability of the medial temporal lobe atrophy scale in a memory clinic population. BMC Neurology 2021, 21, 289, doi:10.1186/s12883-021-02325-2. [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.E.; Ochs, A.L.; Seabaugh, J.M.; Shrader, C.R. Man versus machine: comparison of radiologists' interpretations and NeuroQuant® volumetric analyses of brain MRIs in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013, 25, 32-39, doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11120377. [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.E.; Ochs, A.L.; Tate, D.F.; Tokac, U.; Seabaugh, J.; Abildskov, T.J.; Bigler, E.D. High correlations between MRI brain volume measurements based on NeuroQuant® and FreeSurfer. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2018, 278, 69-76, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.05.007. [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.E.; Lee, M.; Kang, D.W.; Wang, S.-M.; Kim, N.-Y.; Lee, M.K.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, D. Deep learning-based segmentation to establish East Asian normative volumes using multisite structural MRI. Diagnostics 2020, 11, 13. [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, M.; Ganzola, R.; Bocchetta, M.; Pievani, M.; Redolfi, A.; Bartzokis, G.; Camicioli, R.; Csernansky, J.G.; De Leon, M.J.; deToledo-Morrell, L. Survey of protocols for the manual segmentation of the hippocampus: preparatory steps towards a joint EADC-ADNI harmonized protocol. Journal of Alzheimer's disease 2011, 26, 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Zaki, L.A.; Vernooij, M.W.; Smits, M.; Tolman, C.; Papma, J.M.; Visser, J.J.; Steketee, R.M. Comparing two artificial intelligence software packages for normative brain volumetry in memory clinic imaging. Neuroradiology 2022, 64, 1359-1366. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lee, S.A.; Jo, S.W.; Chang, S.-K.; Lim, Y.; Yoo, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Sohn, C.-H. Agreement and Reliability between Clinically Available Software Programs in Measuring Volumes and Normative Percentiles of Segmented Brain Regions. Korean Journal of Radiology 2022, 23, 959. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).