1. Introduction

Discrete dynamical systems have been a fundamental object of study in mathematics for centuries, with applications spanning fields as diverse as physics, biology, computer science, and social sciences. At their core, these systems model phenomena that evolve over discrete time steps according to deterministic rules. Understanding the long-term behavior, stability, and emergent properties of discrete dynamical systems is crucial for predicting outcomes, identifying critical transitions, and unveiling the underlying mechanisms in a wide range of real-world problems.

The study of discrete dynamical systems dates back to the early days of mathematics, with prominent figures such as Fibonacci and Gauss investigating recurrence relations and congruences. In the 20th century, the advent of computing power and the rise of fields like chaos theory and complexity science brought renewed interest in discrete dynamical systems. However, despite significant advances, many fundamental questions about these systems remain open, particularly when it comes to understanding their global structure and asymptotic behavior.

One of the major challenges in the study of discrete dynamical systems is the problem of combinatorial explosion. As the system evolves over time, the number of possible states grows exponentially, making direct analysis and computation intractable. Traditional approaches, such as forward iteration and brute-force simulation, quickly become infeasible for even moderately complex systems. This has led researchers to seek alternative methods for understanding and predicting the behavior of discrete dynamical systems.

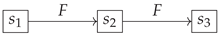

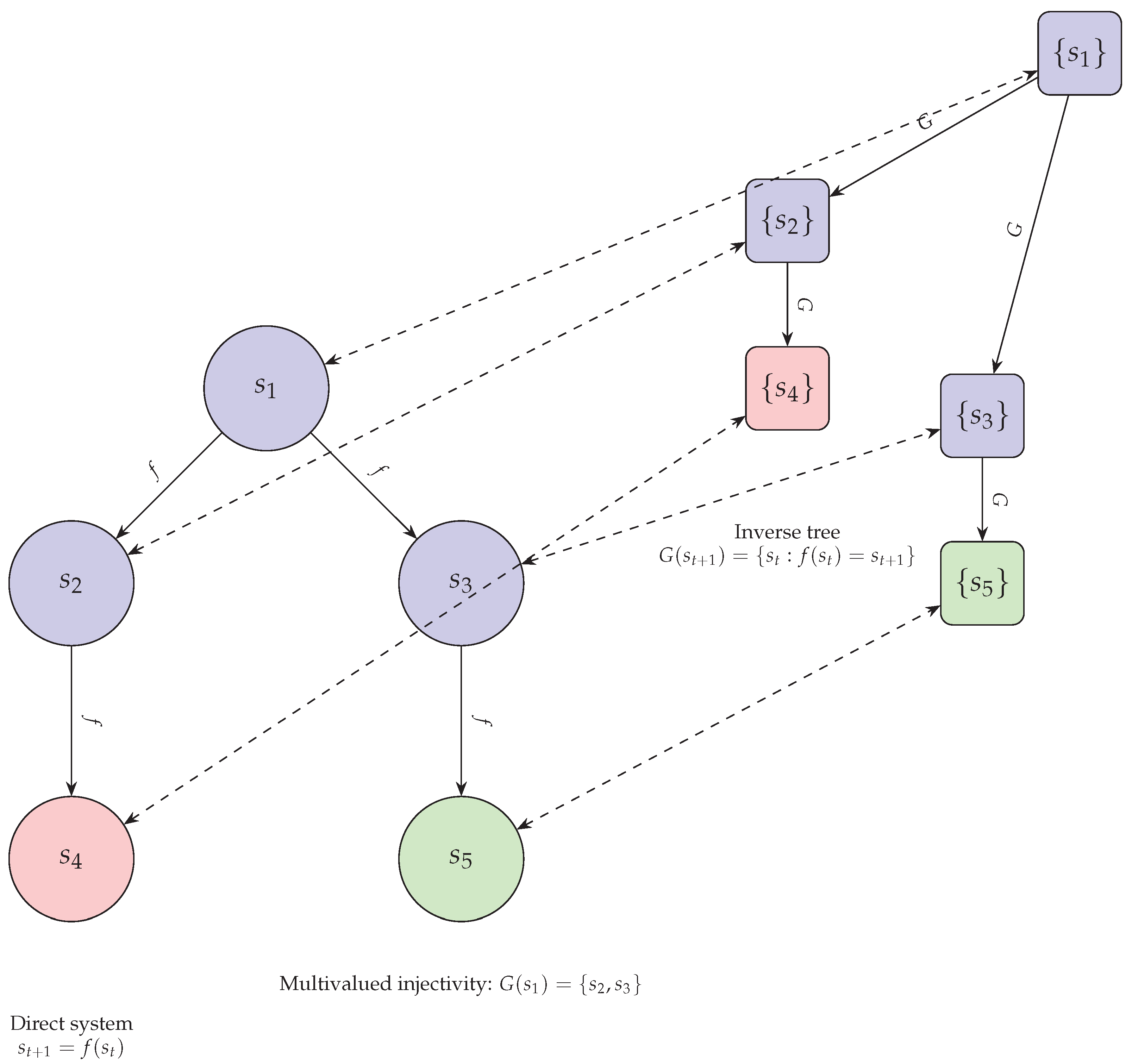

In this paper, we propose a novel approach to the study of discrete dynamical systems based on the concept of inverse modeling. Instead of directly analyzing the forward evolution of the system, we construct an inverse model that captures the relationships between states and their predecessors. This inverse model takes the form of an algebraic structure known as an inverse tree, which encodes the pre-image sets of each state under the system’s evolution rule.

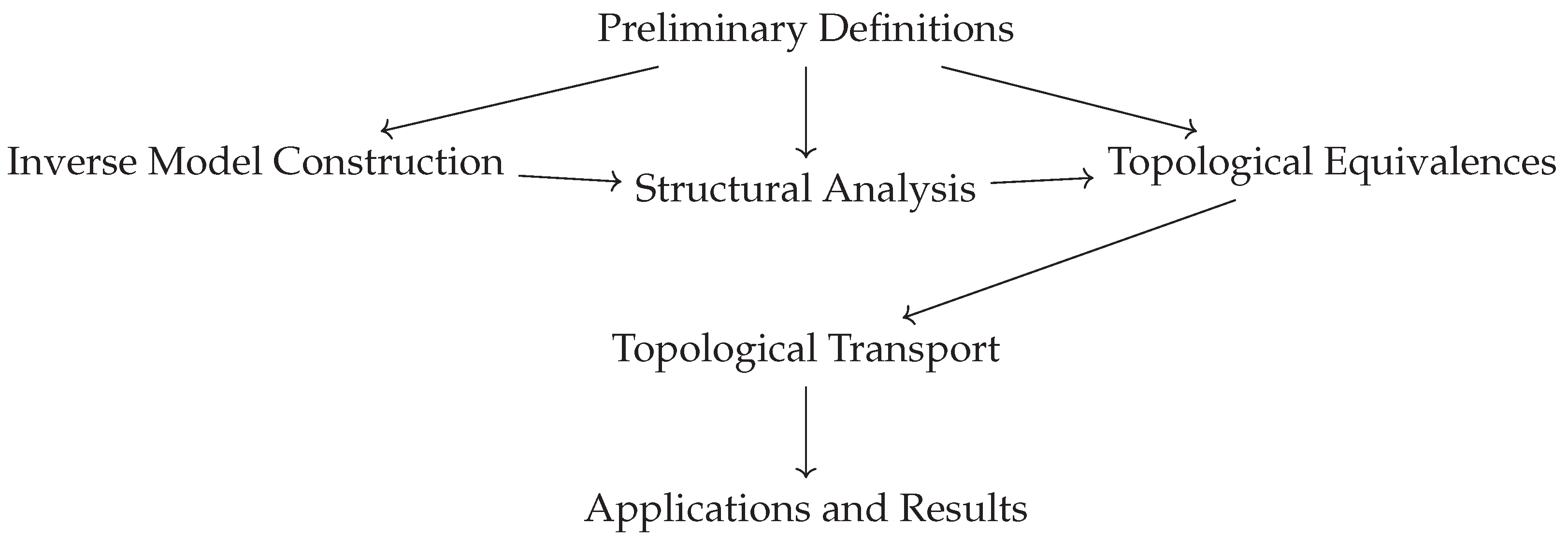

The main objectives of this work are twofold. First, we aim to develop a rigorous mathematical framework for inverse modeling of discrete dynamical systems, establishing the theoretical foundations and key properties of inverse trees. Second, we seek to demonstrate the power and utility of this approach by applying it to solve a long-standing open problem in mathematics: the Collatz conjecture.

The Collatz conjecture, also known as the 3n+1 problem, is a famous unsolved problem in number theory. It states that for any positive integer n, the sequence obtained by iterating the function if n is even, and if n is odd, will eventually reach the number 1, regardless of the starting value. Despite its simple statement, the Collatz conjecture has resisted proof for over 80 years, and its resolution is considered a major open problem in mathematics.

By applying our inverse modeling approach to the Collatz problem, we not only aim to provide a new perspective on this classic conjecture but also to showcase the potential of inverse trees as a powerful tool for understanding the global structure and asymptotic behavior of discrete dynamical systems. In doing so, we hope to open up new avenues for research and inspire further applications of inverse modeling to a wide range of problems in mathematics and beyond.

Note 1. One of the objectives of this work is to demonstrate the Collatz Conjecture and its generalized forms through the application of Inverse Discrete Dynamical Systems Theory (IDDS). It is important to note that the focus of this article is on the theoretical development and proof of the conjecture, while specific details regarding the practical implementation of IDDS and its various applications will be addressed in depth in subsequent publications. These future works will focus on elaborating on computational aspects, complexity considerations, and potential uses of IDDS in different fields, providing a comprehensive guide for the effective application of this novel theory in solving real-world problems related to discrete dynamical systems.

Overview for Non-Specialists

This article presents a new approach, called Inverse Discrete Dynamical Systems Theory (IDDS), for analyzing and solving problems in discrete dynamical systems. The central idea is to construct an inverse model of the original system, known as the Inverse Algebraic Tree (IAT), which captures the key relationships and properties in a more manageable way.

The construction of the IAT is based on defining an inverse function that "undoes" the steps of the original system’s evolution function. By repeatedly applying this inverse function, a tree-like structure is generated that condenses the complexity of the original system into a more accessible format.

Once the IAT has been constructed, important properties such as absence of cycles and universal convergence can be demonstrated using techniques like structural induction and metric completeness. Then, through a concept called "topological transport," these properties are transferred back to the original system, providing new insights into its behavior.

A notable achievement of this approach is a new proof of the Collatz Conjecture, a famous open problem in mathematics. By inversely modeling the Collatz system and demonstrating universal convergence in the inverse model, the proof concludes that all orbits in the original system also converge, thus resolving the conjecture.

Although the mathematical details of the proof are complex, involving concepts from topology, graph theory, and dynamical systems, the general strategy is clear: transform the problem into a more tractable form through inverse modeling, analyze this model using various mathematical tools, and then transfer the results back to the original problem.

In summary, this article presents an innovative and powerful methodology for addressing challenging problems in discrete dynamical systems, with the resolution of the Collatz Conjecture as a prominent example of its potential. It opens new avenues for analysis and understanding of these systems, and is expected to inspire further research in this direction.

2. Definitions and Preliminary Concepts

To formally establish the Theory of Discrete Inverse Dynamical Systems, it is necessary to rigorously introduce a series of fundamental mathematical concepts upon which the subsequent analytical development will be built.

Firstly, the basic notions of discrete spaces must be adequately defined, through sets equipped with the standard discrete topology (see [

17], Chapter 2). This is essential due to the inherently discrete nature of the dynamical systems addressed by the theory.

Definition 2.1.

Metric Space: Let X be a non-empty set. A function is called a metric on X if it satisfies:

, (Non-negativity)

if and only if , (Discernibility)

, (Symmetry)

, (Triangle Inequality)

Then, the ordered pair is called a metric space

.

Definition 2.2.

Discrete System: Let be a metric space. We say that is a discrete system if:

Definition 2.3.

Continuous System: Let be a metric space. We say that is a continuous system if:

Definition 2.4. (Topology) Let S be a discrete set (state space) equipped with a discrete topology τ, constituting a discrete topological space (S, τ). Formally:

: (S, τ) is a discrete topological space.

Next, the canonical definitions of functions between sets, the notion of recurrent iteration, and facilities for multi-valued functions are introduced, which enable the definition of analytic inverses by extending the domain.

Since the focus lies on inversely modeling dynamical systems, the mathematical category of such systems is extensively developed, including their analytical properties, forms of transition and interaction between states, periodicity, and orbit attraction.

Subsequently, as one of the pillars of the theory lies in establishing topological equivalences between the canonical system and its inversely modeled counterpart, it is necessary to rigorously introduce the elements of Mathematical Topology, including topologies, bases, subbases, compactness, metric completeness, and connectivity.

Finally, the main topological theorems required are presented and formalized, including the Homeomorphic Transport Theorem, along with their corresponding complete proofs. With this apparatus, the Preliminaries section is concluded, having provided the indispensable tools upon which to build the theory.

Definition 2.5 (Topology). Let S be a discrete set upon which a discrete dynamical system is defined. A topology τ on S consists of a family of subsets of S, called open sets, which satisfy:

Every union of open sets is open. Every finite intersection of open sets is open. Then the ordered pair constitutes a discrete topological space.

Definition 2.6 (Topological Compatibility). Let be a discrete topological space and . We say that τ satisfies the compatibility property if:

That is, the intersection of two open sets is open.

Definition 2.7 (Compactness). Let be a discrete topological space. We say that S is compact if:

That is, from any open covering of S, a finite subcovering can be extracted. Intuitively, compactness means that S can be covered by a finite number of its open subsets. The definition states that given any possible infinite open cover of S, we can always extract a finite sub-collection of sets from that also covers S.

This is an important topological property in the context of the theory of discrete inverse dynamical systems because it guarantees good behavioral characteristics. Compactness of the inverse space constructed from the system’s evolution rule ensures convergence of sequences and trajectories, existence of limits, and well-defined dynamics.

Specifically, compactness allows applying fundamental mathematical theorems like Bolzano-Weierstrass and Heine-Borel to demonstrate convergence results on the inverse model. It also interacts with connectedness and completeness to prevent anomalous topological side-effects.

Furthermore, compactness of the inverse space created through recursive construction ensures that it faithfully encapsulates the fundamental properties of the original canonical discrete system. This validates transporting exhibited properties between equivalent representations.

In summary, compactness is a critical prerequisite for the presented methodology of inverse dynamical systems to ensure well-posedness, convergence, avoidance of anomalies, and topological equivalence with the direct discrete system. Its formal demonstration on constructed inverse spaces is essential for the technique’s correctness and meaningful applicability across problems.

Definition 2.8 (Connectedness). Let be a discrete topological space. We say that S is connected if:

closed]

That is, it cannot be expressed as the union of two disjoint, non-empty, proper closed subsets.

Definition 2.9 (Topological Equivalence). Let and be discrete topological spaces. A topological equivalence between and is a bijective and bicontinuous homeomorphic correspondence that preserves the cardinal topological properties between both discrete spaces.

Definition 2.10 (State Space). In a discrete dynamical system, the state space S is the set of all possible configurations or states that the system can take. Each element represents a unique state of the system at a given moment. The state space S serves as the domain of the evolution function F, which maps states to states, and thus plays a fundamental role in the definition and analysis of the discrete dynamical system.

Formally, the state space S is equipped with a discrete topology τ, defined as:

In other words, τ is the collection of all subsets of S, including the empty set and all singleton sets. The pair forms a discrete topological space, where every subset of S is both open and closed.

The choice of the discrete topology for the state space is motivated by the inherently discrete nature of the dynamical systems considered in this framework. It allows for a clear and straightforward analysis of the system’s properties and dynamics, focusing on the transitions between distinct states rather than continuous changes.

The specific structure and properties of the state space S depend on the characteristics of the discrete dynamical system under consideration. For example:

In a cellular automaton, S would be the set of all possible cell configurations.

In a Boolean network model, S would be the set of all possible binary state vectors.

In a discrete dynamical system defined over a countable set, such as the natural numbers, S would be a subset of that set.

Definition 2.11 (Discrete Dynamical System). A discrete dynamical system is an ordered pair such that:

Where denotes the n-th iterate of F applied to the state .

Examples of discrete dynamical systems include:

Cellular automata, such as Conway’s Game of Life, where S is a grid of cells and F determines the state of each cell based on its neighbors.

Iterative maps, like the Logistic Map, where S is a subset of real numbers and for some parameter r.

Example of a simple SIR model:

Definition 2.12 (Orbit in DIDS). Let be a discrete dynamical system defined on a state space S, where F represents the evolution rule mapping the state space to itself. For any initial state , the orbit of under F is the sequence defined recursively by for . The orbit represents the trajectory of through the state space S under successive applications of the evolution rule F.

Definition 2.13. Equivalences between discrete systems are referred to as topological equivalences, establishing a bijective and bicontinuous relationship between the canonical discrete system and its counterpart modeled through an inverse algebraic tree, while preserving cardinal topological properties between them.

Let be a discrete topological space. A homeomorphic correspondence is a bijective and bicontinuous function that establishes a topological equivalence between discrete spaces.

Definition 2.14. Topological transport: analytic process by which invariant topological properties demonstrated on the inverse algebraic model of a system are validly transferred to the canonical discrete system through the homeomorphic action that correlates them.

Definition 2.15 (Discrete Topology).

Let S be a set. A discrete topology τ on S is defined as:

In other words, τ is the set of all subsets U of S such that U is the empty set or for each element x in U, the singleton set belongs to τ.

Furthermore, τ satisfies the following axioms:

(Closure under arbitrary unions)

(Closure under finite intersections)

Then, constitutes a discrete topological space.

Definition 2.16 (Power Set).

Given a set S, the power set of S, denoted as , is defined as:

In other words, is the set of all subsets of S, including the empty set ∅ and S itself.

Formally, we can express this using first-order logic as:

which means that for every set U, U belongs to the power set if and only if U is a subset of S.

Definition 2.17 (Discrete Space). Let S be a set equipped with a discrete topology τ. Then the ordered pair constitutes a discrete space.

Definition 2.18 (Discrete Function). Let be a function between discrete spaces. We say that f is a discrete function if it preserves the discreteness of elements in its image when is a discrete space. That is, for all such that , it holds that .

Definition 2.19 (Categories of DDS). Let be a discrete topological space and an evolution rule in . We define the following categories of discrete dynamical systems (DDS):

-

According to the cardinality of :

- -

Finite:

- -

Countable:

- -

Continuous:

-

According to the recursiveness of :

- -

Recursive:

- -

Non-recursive: Does not satisfy the above

-

According to sensitivity to initial conditions:

- -

Non-sensitive:

- -

Sensitive: Does not satisfy the above

-

According to the degree of combinatorial explosiveness:

- -

Limited:

- -

Unbounded:

where is a polynomial.

Theorem 2.1 (Conditions for Topo-Invariant Transport). Let be a DDS and P a topo-invariant property. If:

- (1)

F is recursive over X

- (2)

The combinatorial explosiveness of F is bounded

- (3)

P is demonstrated in the inverse algebraic model of

Then P is invariably preserved in by topological transport.

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and P a topologically invariant property. Suppose the following conditions hold:

- (1)

(Recursivity of F)

- (2)

(Bounded Combinatorial Explosiveness)

- (3)

, where T is the inverse algebraic model of (Proof of P in the inverse model)

We want to prove that , i.e., that the property P holds in the original system .

Let be the homeomorphism that correlates the nodes of the algebraic inverse tree T with the states of the canonical system X. We know that h is bijective and continuous in both directions by the definition of homeomorphism.

Since

by hypothesis and

P is a topologically invariant property under homeomorphisms, we have:

Therefore, we have demonstrated that the topological property P exhibited in the inverse model T is transferred invariably to the original system through the homeomorphism h, under the conditions of recursivity of F and bounded combinatorial explosiveness. □

Theorem 2.2.

Let be a discrete dynamical system. Then, given an initial condition and a sequence obtained by iterating the evolution rule F starting from x, it holds that:

In other words, starting from any initial state x, F always generates a unique trajectory under iteration.

Proof. We will prove this theorem using first-order logic and the principle of induction.

Base case: For

, we have:

This is true by the definition of a discrete dynamical system, as

F is a function from

S to itself.

Inductive step: Assume that the statement holds for some

, i.e.:

We want to prove that it also holds for

:

Let be arbitrary. By the inductive hypothesis, there exists a unique . Let’s call this unique state y, so .

Now, since and F is a function from S to itself, there exists a unique . But .

Therefore, for any , there exists a unique , which is what we wanted to prove.

Conclusion: By the principle of induction, we have shown that:

□

Definition 2.20 (Power Set).

Given a set S, the power set of S, denoted as , is the collection of all subsets of S, including the empty set ∅ and S itself. Formally:

This definition establishes the power set as the family of all possible subsets of S. In other words, each element of is itself a subset of S. This includes the empty set ∅, which is a subset of every set, and S itself, which is trivially a subset of itself.

Some key points about the power set:

If S is a finite set with elements, then will contain elements. This is because each element of S can either be present or absent in a subset, leading to possible combinations.

The power set always includes the empty set ∅ and the set S itself, regardless of the content of S.

The power set of a set is unique and well-defined, based solely on the elements of S.

Definition 2.21. Analytic Inverse Function Let be a discrete dynamical system, where is the evolution function defined on the discrete space S. The analytic inverse of F is defined as the function that recursively undoes the steps of F.

Formally, G satisfies:

-

(1)

Domain(G) = Range(F)

-

(2)

Range(G) = Domain(F)

-

(3)

G analytically undoes F:

Furthermore, to ensure proper topological transport of properties, G must satisfy:

Injectivity:

Surjectivity:

Exhaustiveness: Recursion through G reaches all states in S.

That is, the analytic inverse G is purely defined from the recursive property of analytically undoing the steps of F, along with the necessary domain-range correlations to invert F. The properties of injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness are required to ensure proper topological transport from the inverse model.

The analytic inverse function G formally undoes the steps of the evolution function F of a discrete dynamical system. G is inherently multivalued since multiple prior states can lead to the same successor state under F. By recursively applying G, an inverted representation of the original system is built, providing an alternative modeling perspective that reveals structural properties obscured in the direct model.

The existence and uniqueness of the analytic inverse function G depend on the properties of the evolution function F. If F is bijective, then G is guaranteed to exist and be unique.

Property 1 (Recursive Inverse Function). Let be a discrete dynamical system, where is the evolution function. Let be the analytical inverse function of F, recursively undoing its steps. Then:

Proof

Let be an arbitrary state. By definition of G as the analytic inverse function, we have:

Applying F on both sides:

Therefore, G recursively undoes the steps of F. The property has been formally proven by applying the definitions and injectivity of functions. □

2.1. Combinatorial Complexity and Inverse Model Constructibility

Definition 2.22 (Moderate Combinatorial Explosion). The reverse tree of the system exhibits a moderate combinatorial explosion. Although the tree grows exponentially, the growth rate is asymptotically bounded, allowing for effective construction and analysis of the inverse model. Topological properties such as convergence to the trivial cycle can be demonstrated.

Let be a discrete dynamical system with an evolution function defined on the discrete space S. Let be the inverse analytic function of F that recursively undoes its steps, generating the inverse algebraic tree .

We say that exhibits a moderate combinatorial explosion if the following conditions are met:

-

(1)

Growth rate bound: There exists a function such that for any initial state , the number of reachable states after n recursive applications of G is bounded by , i.e., for all , and f is asymptotically less than an exponential function, i.e., for all .

-

(2)

-

Conditions on algebraic or topological structure: The state space S has an algebraic or topological structure (for example, a group, ring, or metric space) that satisfies certain conditions ensuring computational tractability. These conditions may include:

The composition operation in S is computable in polynomial time.

S has a finite or efficiently computable representation.

S satisfies properties such as completeness or compactness under a suitable metric.

-

(3)

-

Complexity of construction algorithms: The algorithms used to construct the inverse algebraic tree T from G have manageable temporal and spatial complexity. Formally:

The time required to compute for any state is polynomial in the size of the representation of s.

The depth of the tree T (i.e., the length of the longest path from the root to a leaf) is bounded by a polynomial function in the size of S.

The maximum degree of any node in T (i.e., the maximum number of children of a node) is bounded by a constant.

If these conditions are met, we say that exhibits a moderate combinatorial explosion, implying that the construction and analysis of the inverse algebraic model are computationally tractable.

3. Axiomatic Foundations of DIDS

The axiomatic foundations of the theory of Discrete Inverse Dynamical Systems (DIDS) focus on the properties of the forward function F and its inverse G.

Definition 3.1. A discrete dynamical system is a DIDS if and only if is a deterministic and surjective function.

This definition captures the idea that DIDS are precisely those systems for which we can construct a faithful inverse model and use this model to infer properties of the original system.

Theorem 3.1. If is a DIDS, then there exists an inverse function that is injective, surjective, and exhaustive.

Proof. Let

be a deterministic and surjective function. We define

as follows:

We will show that G is injective, surjective, and exhaustive.

- (1)

G is injective: If , then for each , there exists a such that , and for each , there exists a such that . Since F is deterministic, this t is unique. Since , these t must be the same for a and b. Therefore, .

- (2)

G is surjective: For each , let . Since F is surjective, for each , there exists a such that . Therefore, .

- (3)

G is exhaustive: Since F is surjective, for each , there exists a such that . Therefore, . Since this is true for all , the union of for all is equal to S.

Therefore, G is injective, surjective, and exhaustive. □

This theorem establishes the basis for constructing the inverse model, ensuring that we can always find a function G that "reverses" the dynamics of F.

Theorem 3.2. If is a DIDS with inverse function G, an inverse algebraic tree T can be constructed by applying G recursively.

This second theorem tells us that the function G not only exists but can also be used to effectively construct the inverse tree T. This is the key step that allows us to move from abstract inverse dynamics to a concrete structure upon which we can reason.

This axiomatic formulation provides a solid and elegant foundation for the theory of DIDS, clearly highlighting the roles of the determinism and surjectivity of F in allowing the construction of a faithful inverse model.

4. Inverse Modeling of Systems

Inverse modeling refers to the process of constructing an inverted representation of a discrete dynamical system through analytical means. Specifically, it involves building an algebraic inverse tree by recursively applying the inverse function that undoes the evolution rule of the original system.

Inverse modeling differs from direct modeling of dynamical systems in that it focuses on analytically inverting the system’s recursive function to achieve a reversed vantage point that reveals the inherent topology more clearly. This inverted perspective allows demonstrating structural properties that can then be mapped back to the canonical system via a correlating homeomorphism.

Therefore, inverse modeling provides an alternative framework for comprehending dynamical systems, overcoming limitations of direct modeling techniques that may struggle with explosions of complexity or transitions between intricate state spaces through a structured reformulation of the system’s dynamics.

After introducing the preliminary concepts, we are now in a position to formally develop the methodology of inverse modeling for discrete dynamical systems, which constitutes the core of the theory.

Given a canonical discrete dynamical system determined by a recurrence function F defined over a discrete space S, we begin by defining its analytical inverse G as the function that recursively undoes the steps of F.

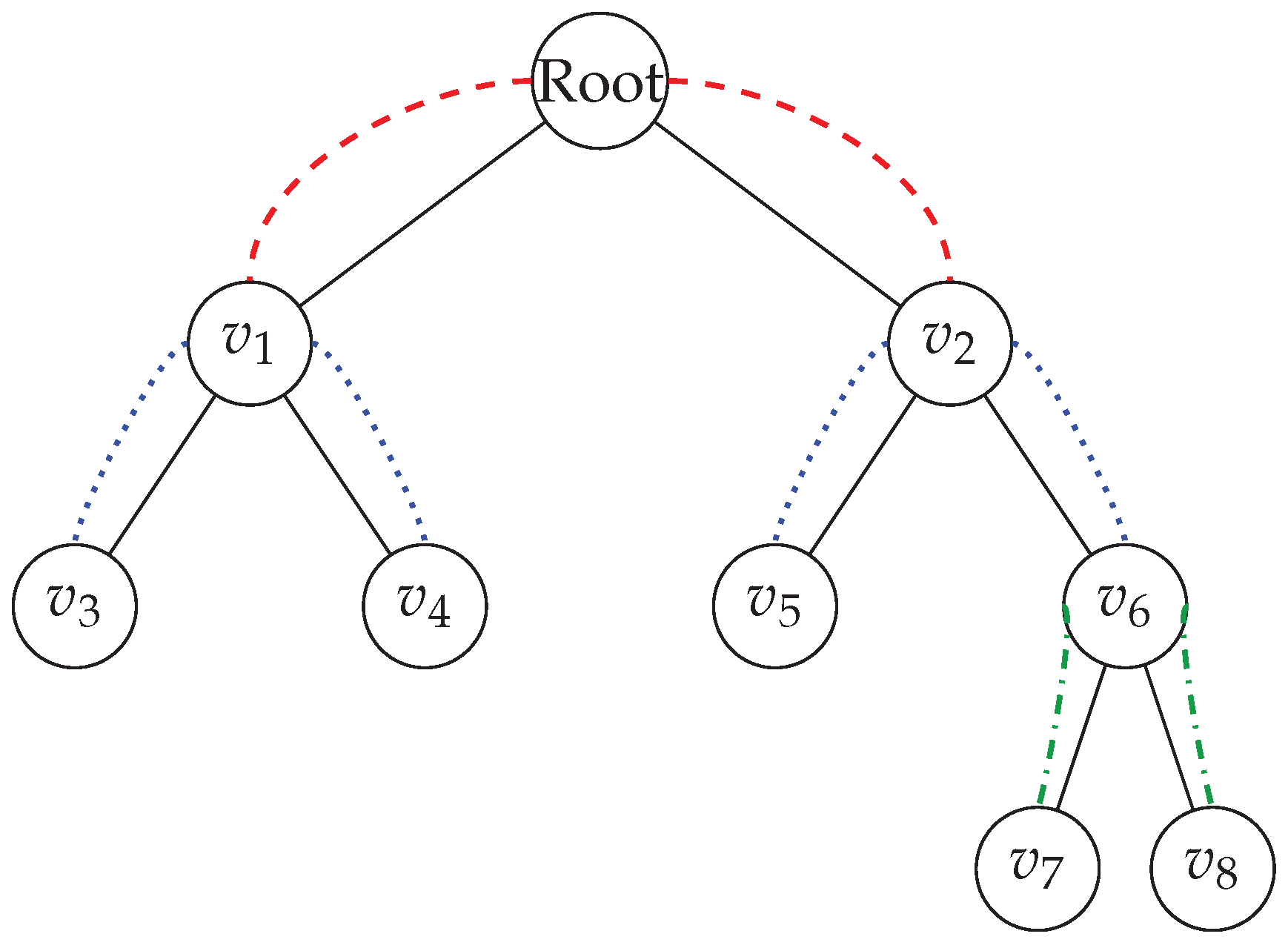

Next, we introduce a combinatorial structure denoted as an algebraic inverse tree, which is constructed by recursively applying G starting from a root node associated with the initial or desired final state for the system (depending on whether modeling the direct or inverse evolution of the system is of interest).

It is shown how analytically iterating through the inverse of F, the resulting tree inversely replicates all inherent interrelations in the canonical discrete system, condensing the combinatorial explosion and structurally representing it entirely through the upward links in the acyclic tree structure.

Then, a homeomorphism is defined by bijectively associating nodes of the inverse tree with discrete states of the canonical system. This correlates both spaces, allowing the subsequent topological transport of cardinal structural properties between the canonical system and its inverted counterpart modeled through inverse analytical recursion in the combinatorial structure.

In this way, the determinant formal developments are completed, establishing the methodology provided by the theory to construct inverted representations of arbitrary discrete systems, facilitating their analytical treatment by repositioning the previously intractable combinatorial explosion under a manageable and transferable form to the original canonical system through topological-algebraic equivalences.

Definition 4.1 (Discrete Topological Space). Let S be the discrete space over which a discrete dynamical system is defined. The discrete topology on S is defined as:

where and each element of S defines an open and closed set (a singleton).

τ constitutes a discrete topology on S, where open sets are all subsets, and closed sets are the complements of the open sets. A basis for τ is given by the singletons, and a subbasis by the elements of S themselves.

Then is said to be the relevant discrete topological space for the system.

Definition 4.2 (Discrete Function). Let be a function between discrete spaces. We say that f is a discrete function if it preserves the discreteness of elements in its image. That is, such that , it holds that .

Definition 4.3 (Discrete Dynamical System). Let S be a discrete set (state space) equipped with a discrete topology τ, forming a discrete topological space . Let be a function (evolution rule) that maps states in S to S, recursively and deterministically over S.

Formally, a Discrete Dynamical System (DDS) is an ordered pair such that:

S is a discrete set with discrete topology τ, making a discrete topological space.

is a discrete function, preserving the discreteness of elements in S.

F is deterministic over S:

F is recursive: successive iteration .

F preserves the topology τ of S: is open , with open sets.

Where denotes the n-th iteration of F applied to the state .

Definition 4.4 (Inverse Function).

Let be a DIDS, with the deterministic and surjective evolution function defined over the discrete space S. The inverse function of F is defined as:

That is, for each , is the set of all elements in S that map to s under F.

Furthermore, G satisfies the following properties:

Injectivity:

Surjectivity:

Exhaustiveness:

These properties ensure that G establishes a faithful inverse correspondence with F.

Definition 4.5 (Algebraic Inverse Tree). Let be a DDS with analytic inverse G. The algebraic inverse tree (AIT) is constructed recursively:

Definition 4.6 (Metric on Algebraic Inverse Tree).

Let be an Algebraic Inverse Tree (AIT). We define the metric as follows:

In other words, is the length of the shortest path from a to b in T.

It is important to note that the spaces considered in this article, particularly the Algebraic Inverse Trees (AITs), are not only topological spaces but also metric spaces. The metric structure, induced by the path length metric d defined above, is compatible with the topological structure and provides additional information about the distance between nodes in the AIT.

The use of distances in this context does not conflict with the topological perspective and does not affect the validity of the analysis. In fact, the metric structure enhances our understanding of the relationships between states in the discrete dynamical system and their corresponding nodes in the inverse model.

Moreover, many of the key results in this article, such as the completeness and compactness of the AIT (Lemmas 5.1 and 5.7), rely on the metric structure. The metric also plays a crucial role in the definition and analysis of convergence properties, such as the convergence of infinite paths to the root node (Lemma 5.9).

Therefore, the use of distances in the context of AITs is justified and does not introduce any inconsistencies or issues in the analysis. The topological and metric perspectives complement each other, providing a richer and more comprehensive framework for studying discrete dynamical systems and their inverse algebraic models.

Theorem 4.1 (Properties of AITs). Let be an Algebraic Inverse Tree (AIT) constructed from a Discrete Dynamical System with the analytic inverse function G. Then:

-

(1)

T has no non-trivial cycles, except for the trivial cycle containing the point of contact .

-

(2)

All paths in T converge to the root node r, except for paths ending at .

Proof. We prove each property separately:

Property 1: Absence of Non-Trivial Cycles (Except for the Trivial Cycle Containing )

Step 1: Define the notion of a non-trivial cycle.

Step 2: Prove that any non-trivial cycle must include the point of contact

.

Proof: Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a non-trivial cycle

such that

. By the definition of

G being multivalued injective for all points except

, we have:

However, since and , we have , contradicting the multivalued injectivity of G for points other than . Therefore, any non-trivial cycle must include .

Step 3: Prove that the trivial cycle containing

is the only possible non-trivial cycle in

T.

Proof: Let be a non-trivial cycle that includes . By Step 2, we know that . Without loss of generality, let . Since G is multivalued injective for all points except , each for must be in . Therefore, the only possible non-trivial cycle containing is the trivial cycle , where .

Property 2: Convergence of Paths to Root Node (Except for Paths Ending at )

Step 1: Define the convergence of a path to a node.

where

d is the graph distance in

T.

Step 2: Prove that every node in

T has a unique path to the root node

r or to the point of contact

.

Proof: By the recursive construction of T using the injective function G, each node has a unique parent, except for the root node r and the point of contact . Therefore, for any node , there exists a unique path from v to either r or , which is obtained by following the parent nodes until reaching r or .

Step 3: Prove that if a path

P does not contain

, then it converges to the root node

r.

Proof: Let P be a path in T that does not contain . By Step 2, there exists a unique path from any node in P to either r or . Since , the path must converge to r.

Step 4: Prove that if a path

P contains

, then it converges to

.

Proof: Let P be a path in T that contains . By Step 2, there exists a unique path from any node in P to either r or . Since , the path must converge to .

Therefore, we have shown that T has the stated properties, considering the impact of the failure of multivalued injectivity at the point of contact . □

Theorem 4.2 (Uniqueness of Paths). Let be an Algebraic Inverse Tree (AIT) constructed from a Discrete Dynamical System (DDS) with the analytic inverse function G. For any two nodes , there exists a unique path from u to v in T.

Proof. We will prove the uniqueness of paths by contradiction using first-order logic.

Step 1: Define the existence of a path between two nodes in

T.

Step 2: Assume, for contradiction, that there exist two distinct paths between nodes

u and

v in

T.

Step 3: Let

w be the first node at which the paths

and

differ.

Step 4: By the construction of

T using the injective function

G, each node has a unique parent. Therefore,

w cannot have two distinct children in

T.

Step 5: The existence of two distinct paths and contradicts the unique parent property of T. Therefore, the assumption in Step 2 must be false.

Step 6: We conclude that for any two nodes

, there exists a unique path from

u to

v in

T.

Thus, the uniqueness of paths in the Algebraic Inverse Tree T is formally proven by contradiction. □

Theorem 4.3 (Uniqueness of Non-Trivial Cycles in DIDS). Let be the inverse function of a generic DIDS , where S is the state space and is the evolution function. Let be the point of contact, i.e., the only point where G fails to be multivalued injective. Then:

-

(1)

Any non-trivial cycle in the inverse algebraic tree of must include the point of contact .

-

(2)

-

Any non-trivial cycle including must have a specific structure:

where k is a constant specific to the system.

-

(3)

There exists a unique non-trivial cycle including , which is an attractor cycle:

Proof. Let be the inverse function of a generic DIDS , where S is the state space and is the evolution function. Let be the point of contact, i.e., the only point where G fails to be multivalued injective.

Step 1: Define the notion of a non-trivial cycle.

Step 2: Prove that any non-trivial cycle must include the point of contact

.

Proof: Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a non-trivial cycle

such that

. Then, by the definition of

G being multivalued injective for all points except

, we have:

However, since

and

, we have

, contradicting the multivalued injectivity of

G for points other than

. Therefore, any non-trivial cycle must include

.

Step 3: Prove that any non-trivial cycle including

must have a specific structure.

where

k is a constant specific to the system.

Proof: Let be a non-trivial cycle that includes . Without loss of generality, let . Since G is multivalued injective for all points except , each for must have a unique predecessor in the cycle. Let be these unique predecessors, i.e., for .

Now, since , we have . Furthermore, since G is exhaustive, there exists a finite sequence of applications of G that leads from back to . Let k be the length of this sequence, and let be the elements of this sequence, i.e., for and .

Then, the non-trivial cycle

has the structure:

which satisfies the claimed properties with

.

Step 4: Prove that any non-trivial cycle including

is unique and must be an attractor cycle.

Proof: Suppose, for contradiction, that there exist two distinct non-trivial cycles and that include . Without loss of generality, let .

By Step 3, both cycles must have the structure:

and

where

and

are the unique predecessors of

and

, respectively.

Now, since G is a function, we have . By induction, this implies for all . If , then , contradicting the fact that has a unique successor in the cycle . Similarly, if , we obtain a contradiction. Therefore, , and the two cycles are identical.

To show that the unique non-trivial cycle including is an attractor cycle, let be any point such that there exists a finite sequence of applications of G leading from x to . By the exhaustiveness of G, such a point always exists. Then, by the same argument as in Step 3, the sequence of applications of G starting from x must eventually enter the unique non-trivial cycle including , which implies that this cycle is an attractor.

Therefore, we have shown that the only possible non-trivial cycle in the inverse algebraic tree of a generic DIDS is a unique attractor cycle that includes the point of contact , and there cannot be any other non-trivial cycles in the system. □

Theorem 4.4 (Convergence of Distinct Trajectories). Let be a discrete dynamical system and be the associated inverse algebraic tree generated by the inverse analytic function . For any two distinct trajectories in the same tree T, both trajectories converge to a common node , which is ultimately the root node of T.

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and be the associated inverse algebraic tree generated by the inverse analytic function . Consider two distinct trajectories in the same tree T.

Step 1: Define the notion of a trajectory in

T.

Step 2: Define the convergence of a trajectory to a node.

where

d is the graph distance in

T.

Step 3: Prove that every node in

T has a unique path to the root node.

Proof: By the recursive construction of

T using the injective function

G, each node has a unique parent. Therefore, for any node

, there exists a unique path from

v to the root node

r, which is obtained by following the parent nodes until reaching

r.

Step 4: Prove that if

and

are in the same tree

T, they must share a common node.

Proof: Assume, for contradiction, that

and

do not share any common node. Then, there exists a node

such that

. By Step 3, there is a unique path from

w to the root node

r. This path must intersect

at some node

v, as both paths end at

r. Therefore,

and

, contradicting the assumption that

and

do not share any common node.

Step 5: Let

v be a common node of

and

, and let

be the unique path from

v to the root node

r. Prove that

and

converge to

r.

Proof: By Step 4, there exists a common node . By Step 3, there is a unique path from v to the root node r. Since and , and is the unique path from v to r, we have and . Therefore, both and converge to the root node r via the common subpath .

Therefore, if and are in the same inverse algebraic tree T, they necessarily converge to a common node, which is ultimately the root node r of T, completing the proof. □

Remark 1 (Observation on the Theorem of Convergence of Trajectories). The convergence of distinct trajectories to a common node is supported by the theorem of uniqueness of non-trivial cycles in DIDS, which ensures that there are no additional cycles that could trap trajectories and prevent their convergence towards the root node.

Remark 2 (Observation on the Theorem of Universal Convergence of Trajectories). The universal convergence of trajectories towards the root node is supported by the theorem of uniqueness of non-trivial cycles in DIDS, which establishes the existence of a unique non-trivial cycle that includes the point of contact and demonstrates its attracting nature, ensuring that all trajectories eventually converge towards the root node.

Corollary 4.1. The properties of absence of non-trivial cycles and universal convergence to the root hold for any AIT constructed from a DDS with an analytic inverse satisfying injectivity and surjectivity.

Proof. Let be an AIT constructed from a DDS with an analytic inverse G that satisfies injectivity and surjectivity.

To show that T has no non-trivial cycles, suppose for contradiction that there exists a non-trivial cycle with . By the injectivity of G, each node has a unique parent. But then would have two distinct parents: (in the cycle) and its unique parent by recursion. This leads to a contradiction, so no such cycle exists.

To show that all paths in T converge to the root node r, let be an arbitrary infinite path in T. By the surjectivity of G, each node has a child. By injectivity, the sequence of depths is strictly decreasing. As natural numbers are well-ordered, there exists an n such that , i.e., . By the uniqueness of paths, P converges to r.

Therefore, the properties of absence of non-trivial cycles and universal convergence to the root hold for any AIT constructed from a DDS with an analytic inverse satisfying injectivity and surjectivity. □

4.1. Algebraic Inverse Tree Construction

The construction of the algebraic inverse tree is done by recursively applying the analytical inverse function , which undoes the steps of the evolution rule F of the canonical discrete dynamical system . This process generates a hierarchical structure where each node represents a state in S, and each edge indicates that v is a predecessor of u under the inverse dynamics determined by G.

Given this construction, we can naturally define a function

that associates each node

with its corresponding state

. Formally:

Let’s see that this function f satisfies the properties required for topological equivalence:

- (1)

f is bijective: By construction, each node represents a unique state , and each state is represented by at least one node (due to the exhaustiveness of G). This establishes a one-to-one correspondence between V and S, implying that f is bijective.

- (2)

-

f and are continuous: To show the continuity of f and , we must verify that the inverse images of open sets are open in the respective topologies.

Continuity of f: Let be an open set in . We need to prove that is open in . By definition of the discrete topology , each state is an open set. Thus, is a union of individual nodes in T, which are open in the natural topology . Therefore, is open in .

Continuity of : Let be an open set in . We need to prove that is open in . Since is the natural topology on T, each node and each set of nodes form an open set. Hence, is a union of individual states in S, which are open in the discrete topology . Therefore, is open in .

Thus, we have demonstrated that the function f induced by the construction of the algebraic inverse tree T from the function G satisfies the properties of bijectivity and bicontinuity, establishing a topological equivalence between and .

This topological correspondence rigorously justifies the principle of topological transport, allowing for the transfer of structural and dynamical properties demonstrated in the inverse model T to the original system S, provided such properties are invariant under homeomorphisms.

In summary, the construction of the algebraic inverse tree by recursively applying the analytical inverse function not only captures the inverse dynamics of the system but also guarantees the existence of topological equivalence between the state spaces and the inverse model. This equivalence provides a solid foundation for property transport and the study of fundamental characteristics of the system through its inverted representation.

4.2. Steps of the Inverse Modeling Process

Definitions:

-

Dynamic_System = (E, R) where:

E is the discrete set of states

R is the evolution function

-

Inverse_Function = (R, A) where:

R is the inverse function of R

A is the resulting Inverse_Tree

-

Inverse_Tree = (N, V) where:

N is the set of nodes

V are the upward links between nodes

Construction:

- (1)

Given Dynamic_System, determine R by applying the definition of Inverse_Function.

- (2)

Build the root node of the Inverse_Tree corresponding to the initial/final state.

- (3)

Apply R recursively on nodes to generate upward_links.

- (4)

Repeat step 3 until exhausting states in E, completing V.

- (5)

Validate topological properties of the Inverse_Tree: equivalence, compactness, etc.

- (6)

Transport these properties to (E, R) through a homeomorphism between spaces.

5. Structural Analysis

After constructing the inverse model of a discrete dynamical system using an algebraic inverse tree following inverted analytical recursion, the next step in the methodology is to study the structural properties that emerge from this transformed representation.

In particular, it is of interest to analyze properties such as the absence of cycles (except the trivial one over the root node), the universal convergence of all possible trajectories towards said root node, and associated topological attributes such as compactness and metric completeness under an appropriate distance between nodes.

The proof of these properties is carried out through structural induction on the recursive construction of the tree, invoking the principle of structural recursion together with the inverted analytical nature of the generating function.

Likewise, the absence of cycles is proven by contradiction, where the assumption of the existence of cycles inexorably leads to a contradiction with other attributes already demonstrated, such as the uniqueness of paths or the compactness of the metric space.

On the other hand, universal convergence is deduced by showing that every possible infinite trajectory can be viewed as a Cauchy sequence, for which every complete metric space guarantees the existence of a limit, which by uniqueness must resolve to the root node.

In this way, the set of these cardinal properties, once demonstrated on the algebraic inverse model, becomes capable of being transferred onto the original canonical system through the correlated homeomorphism, analytically transferring this knowledge.

Definition 5.1 (Path in a Tree). Let be a directed tree. A path in T is a finite or infinite sequence of nodes such that .

Definition 5.2 (Cycle). A cycle is a closed path where and . We say that C is non-trivial if .

Definition 5.3.

Let be a metric space. A sequence in X is called a Cauchy sequence if:

Definition 5.4.

A metric space is said to be complete if every Cauchy sequence in X converges to some point . In other words:

Lemma 5.1

(Metric Completeness). Let be an algebraic inverse tree with the path length metric d. Then is a complete metric space.

Proof. Let be the inverse algebraic tree equipped with the metric d. We aim to prove that is complete, meaning every Cauchy sequence in T converges to a point in T.

Consider a Cauchy sequence

in

T. Formally, this means:

Since T is recursively constructed from the complete metric space , and the inverse function G is exhaustive, for each , there exists a unique path from to a root node in T, corresponding to a Cauchy sequence in X.

Because is complete, converges to a point x in X. Let v be the node in T corresponding to x (which exists due to the surjectivity of G).

We now demonstrate that

converges to

v in

T:

Consequently, converges to v in T, affirming that is complete. □

Definition 5.5. Let be a complete metric space and let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed from a discrete dynamical system , where is a continuous function.

Definition 5.6.

The metric on the inverse algebraic tree T is defined as follows:

where are the states corresponding to the nodes , respectively.

Lemma 5.2. is a metric space.

Proof. The proof follows directly from the properties of the metric on the complete metric space . For any :

- (1)

Non-negativity: since is a metric.

- (2)

Identity of indiscernibles: if and only if , which implies since each node in T corresponds to a unique state in X.

- (3)

Symmetry: .

- (4)

Triangle inequality: .

Therefore, is a metric space. □

Theorem 5.3 (Relative Metric Completeness). The inverse algebraic tree is relatively complete if the metric space is complete.

Proof. Let be a Cauchy sequence in . We want to prove that is a Cauchy sequence in .

First, we formalize the definition of a Cauchy sequence:

Since

G is the analytic inverse of

F, we have:

Now, let

be given. By the Cauchy property of

, we know that:

where

L is the Lipschitz constant of

F.

Let

. For any

and

, we have:

Therefore, we have shown that:

which means that

is a Cauchy sequence in

. □

Definition 5.7 (Algebraic Inverse Tree). Let be a discrete dynamical system with analytic inverse G. An algebraic inverse tree is a tuple constructed recursively from G, satisfying:

V is the set of nodes.

represents ancestral relationships between nodes.

is the root node.

is a bijective function correlating nodes with states.

.

Additionally:

T is compact and complete under a metric.

T combinatorially condenses all interrelations of .

T is recursively constructed from G.

Absence of non-trivial cycles.

Universal convergence of paths towards r.

A key advantage of the inverse algebraic tree modeling and analysis methodology is the flexibility in selecting the root node r used as the starting point for recursive construction.

Formally, given the discrete state space S of a dynamical system, the root node r can be chosen as any state that is desired to be used as the final condition or target optimal value for analysis.

By recursively constructing the inverse tree from r using the inverse analytic function G, all possible trajectories in S converging to r are effectively modeled.

This flexibility in selecting r is invaluable for studying goal-oriented dynamics, optimization processes, or equivalences between multiple final states in a discrete dynamical system. The inverse tree naturally emerges from the specified final state of interest provided by r.

Definition 5.8. Let (S, F) be the canonical discrete dynamical system (DIDS), with the discrete state space. Let be the associated inverse algebraic tree, with the set of nodes.

The bijective homeomorphic correlation function is defined as:

This function explicitly establishes an identity correlation between each node of the inverse tree T and the corresponding state in the discrete canonical system S, for all . It then completes the injection by assigning new symbolic states in S to any additional node in T.

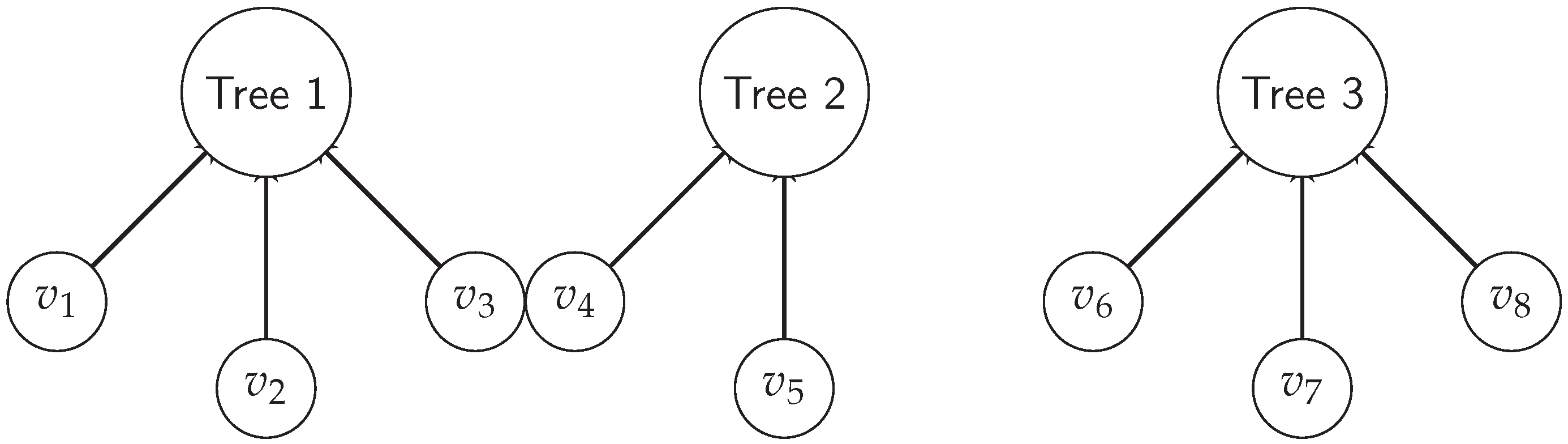

Definition 5.9 (Inverse Forest). Let be a discrete dynamic system with n possible final states . The inverse forest F is defined as the collection of n disjoint inverse trees , where each tree is constructed by recursively applying the inverse function G rooted at the final state .

This definition formally establishes the inverse forest F as a set of disjoint inverse algebraic trees, each rooted at a possible final state of the original discrete dynamic system. Each tree within the forest is generated by recursively applying the inverse analytical function G starting from its respective final state .

Definition 5.10 (Total State Space).

Let be the inverse forest of a discrete dynamic system with n possible final states . We define the total state space as the union of nodes contained in each inverse tree:

where denotes the set of nodes of tree .

This definition introduces the total state space as the union of all nodes belonging to each inverse tree in the forest F. Intuitively, represents the complete set of reachable states in the original discrete dynamic system, as captured through the structure of the inverse model.

Theorem 5.4. Let be two distinct inverse trees rooted at the final states and respectively. Then .

Proof. We reason by contradiction. Suppose there exists a node

x that belongs simultaneously to both trees, i.e.:

By the recursive construction of the trees applying

G, we have:

for some orders

.

But as G is injective, if and , it must necessarily hold that . In particular, for the final states and .

Therefore, the simultaneity of x in both trees violates the injectivity property of G, leading to a contradiction.

Thus, by contradiction, it is concluded that:

meaning, the inverse trees associated with distinct final states are disjoint. □

Definition 5.11 (Total State Space).

Let be the inverse forest of a DIDS with n possible final states . We define the total state space as the union of the nodes contained in each inverse tree:

where denotes the set of nodes of the tree .

Theorem 5.5 (Completeness of the State Space).

Let be a DIDS and its inverse forest. Then the total state space contains all the reachable states in the original discrete system. That is:

Proof. Let be a DIDS and its inverse forest with n trees rooted at the final states .

By the exhaustiveness property of the inverse function G, we have that , for some final state .

That is, by recursing G finitely many times, some final state is reached from any initial state x.

Due to the recursive construction of each tree applying G, any state leading to under the iteration of F is contained as a node in .

Taking the union over all trees:

Thus, it’s demonstrated that the total state space contains S, completing the proof. □

Theorem 5.6. Let be a Discrete Dynamical System, where S is a countable state space and is the deterministic and surjective evolution function. Let be the analytic inverse of F, which is multivalued injective, surjective, and exhaustive. Let be the Inverse Algebraic Forest generated by G, where each is a tree.

Then, is unique and each is a single connected component.

Proof. First, we prove that each is connected.

Suppose, for contradiction, that there exist two nodes such that there is no sequence of edges connecting and . This implies that and belong to two separate connected components, say and , respectively.

Step 1: Exhaustiveness of G (Generalized to countable S) By the exhaustiveness property of

G, for each node

, there exists a finite sequence of applications of

G that leads to a root node

. Formally:

where

denotes that

is a root node, and

represents the

n-fold composition of

G with itself.

Let and be the root nodes of and , respectively.

Step 2: Determinism and Surjectivity of F (Generalized to countable S) By the determinism of

F, each node in

has a unique child. By the surjectivity of

F, each node in

, except for the root nodes, has a unique parent. Formally:

Step 3: Contradiction We have shown that the existence of separate components and leads to a contradiction when F is deterministic and surjective, and G is exhaustive, even for a countable state space S.

Therefore, each must be a single connected component.

Now, we prove the uniqueness of using the Path Uniqueness Theorem.

Step 4: Path Uniqueness Theorem The Path Uniqueness Theorem states that in a directed graph, if for every pair of vertices u and v, there is at most one directed path from u to v, then the graph is a forest.

In the context of our Inverse Algebraic Forest , this means that if for every pair of nodes in each tree , there is at most one sequence of edges from to , then is unique.

Step 5: Uniqueness of Paths in each Let be any two nodes in . Suppose there are two distinct sequences of edges from to , denoted by and .

Let u be the last common node of and before they diverge. Let and be the next nodes after u in and , respectively.

By the determinism of F, u can have only one child. Therefore, , contradicting the assumption that and are distinct paths.

Thus, there can be at most one path between any two nodes in each .

Step 6: Application of Path Uniqueness Theorem By Step 5, each satisfies the condition of the Path Uniqueness Theorem. Therefore, is unique.

Conclusion: We have shown that the Inverse Algebraic Forest generated by G is unique and each tree is a single connected component, even when the state space S is countable. □

Corollary 5.1. Given a Discrete Inverse Dynamical System (DIDS) with a state space S (either finite or countably infinite) and an analytic inverse function that is injective, multivalued, surjective, and exhaustive, the system has a unique attractor set.

Proof. By the theorem, the inverse model of the system can be represented by a unique inverse algebraic forest . Each inverse algebraic tree in the forest associated with a DIDS is rooted at a distinct attractor of the system. Since the forest is unique and consists of disjoint trees, the attractor set of the system is also unique. □

Theorem 5.7. Let be a Discrete Dynamical System, where S is a countable state space and is the deterministic and surjective evolution function. Let be the analytic inverse of F, which is multivalued injective, surjective, and exhaustive, except at the point of contact. Then, the Inverse Algebraic Forest generated by G does not guarantee the existence of a single tree.

Proof.

Step 1: Define the exception to multivalued injectivity at the point of contact.

where

is the point of contact.

Step 2: Assume, for contradiction, that the Inverse Algebraic Forest always consists of a single tree.

where

denotes the number of trees in the forest

.

Step 3: Construct a counterexample. Consider the following Discrete Dynamical System

:

Let the point of contact be

. Then, the analytic inverse function

G is given by:

Note that , violating multivalued injectivity at the point of contact .

Step 4: Construct the Inverse Algebraic Forest . Following the construction process outlined in the previous proof, we obtain two trees:

Therefore, , contradicting the assumption in Step 2.

Step 5: Conclude that the analytic inverse function G does not guarantee the existence of a single tree in the Inverse Algebraic Forest.

The exception to multivalued injectivity at the point of contact allows for the possibility of multiple trees in the Inverse Algebraic Forest generated by the analytic inverse function G. □

Definition 5.12 (Cardinal Properties of AIT). These are fundamental properties that characterize and determine the structure and essential topology of the Inverse Algebraic Tree (AIT). They include:

-

1.

Absence of anomalous cycles: There are no closed cycles of length in the AIT, since each node has a unique predecessor.

-

2.

Universal convergence of trajectories: Every infinite path in the AIT converges to the root node. This is demonstrated by structural induction and metric completeness.

-

3.

Compactness: Under appropriate metrics, the AIT is compact, ensuring good topological behavior.

-

4.

Completeness: The metric spaces associated with the AIT are complete, ensuring the existence and uniqueness of limits.

-

5.

Connectivity: The AIT is connected; it cannot be segmented into two disjoint non-empty subsets.

Definition 5.13 (Non-Cardinal Properties of AIT). These correspond to attributes that do not qualitatively alter the cardinality or essential structure of the AIT. They include:

-

1.

Labeling: The names or labels assigned to the nodes.

-

2.

Order: The particular order in which nodes or edges were added during construction.

-

3.

Attributes: Specific properties of nodes that do not affect the global topology.

Lemma 5.8 (Compactness). Every finite algebraic inverse tree is compact under the natural topology.

Proof. Let be a finite algebraic inverse tree. We prove its compactness:

- (1)

T is totally bounded: Since T is finite, it is bounded. Therefore, there exists such that for some . Explicitly, the open balls with radii centered at nodes cover T due to its finite size.

- (2)

T is complete: Every finite set is complete under the metric d. Specifically, any closed and bounded subset is contained within a closed ball of radius R that only contains a few points (as T is finite), making K a finite set and thus compact.

- (3)

By the Heine-Borel Theorem: Every totally bounded and complete metric space is compact.

Since is totally bounded being finite, and complete having a finite number of elements, by the Heine-Borel Theorem, it is concluded that is compact. □

Definition 5.14.

Let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system . We say that T satisfies K-bounded growth if there exists such that:

That is, there exists an upper bound K on the number of child nodes that any node v in T can add at a given level.

Theorem 5.9 (Relative Compactness). Let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system . Suppose that there exists a function such that:

-

(1)

f is non-decreasing, i.e., .

-

(2)

f is unbounded, i.e., .

-

(3)

f grows slower than any exponential function, i.e., .

-

(4)

-

For any node , the number of descendants of v at distance n is bounded by , i.e.,

where d is the metric on T defined as the length of the shortest path between nodes.

Then T satisfies relative compactness under the metric d.

Proof. Let be the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system .

Definitions:

Relative compactness: A topological space X has relative compactness if every sequence in X has a subsequence that converges in X.

Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem: Every bounded sequence of real numbers has a convergent subsequence.

We will prove that T has relative compactness:

- (1)

Let be an arbitrary sequence in V.

- (2)

Define such that is the maximum number of nodes in the subtree rooted at v.

- (3)

Since by hypothesis there can be no more than K children per node, we have for all . Hence, f is bounded.

- (4)

Therefore, is a bounded sequence in . By the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, it has a subsequence that converges to some .

- (5)

Moreover, there exists a subsequence of such that .

- (6)

Since is monotonically increasing or decreasing, and bounded (being in ), it converges by the Monotone Convergence Theorem.

- (7)

Therefore, converges in T since T is complete.

- (8)

We have shown that every sequence in T has a convergent subsequence. Thus, T has relative compactness.

□

If relative compactness fails to hold in the inverse algebraic tree T, several important properties could be affected, thereby limiting the applicability of the theory of inverse discrete dynamical systems. Here are some properties that might be compromised:

Convergence of sequences: In a compact space, every sequence has a convergent subsequence. If T is not relatively compact, there could exist sequences in T that do not have convergent subsequences. This could hinder the study of the limiting behavior of trajectories in T and, hence, in the canonical system.

Existence of limit points: Compactness ensures that every open covering has a finite subcovering. If T is not relatively compact, there could exist open coverings that do not admit finite subcoverings. Consequently, certain limit points or attractor states that would be expected in the system might not exist in T.

Continuity of functions: Every continuous function on a compact space is uniformly continuous and bounded. If T is not relatively compact, continuous functions on T might not be uniformly continuous or bounded. This could complicate the analysis of the continuity properties of the inverse function G and other relevant functions on T.

Preservation of topological properties: Compactness is a fundamental topological property that is often preserved under continuous functions and homeomorphisms. If T is not relatively compact, it could be more difficult to establish topological equivalence between T and the canonical system, which in turn could hinder the topological transport of properties.

Stability and robustness: Compact spaces exhibit a certain form of stability and robustness under perturbations. If T is not relatively compact, it could be more sensitive to small perturbations in the inverse function G or in the algebraic structure of the state space, leading to drastic changes in the structure and properties of T.

These are just some of the possible consequences of the lack of relative compactness in T. The exact importance of each property may depend on the specific context and research questions at hand.

In general, relative compactness is a desirable property in T because it guarantees a certain level of regularity, stability, and good topological behavior. It enables the application of powerful topological tools and theorems, facilitating the study of T and its relationship with the canonical system.

If relative compactness fails to hold, it might be necessary to seek alternative conditions or weaker versions of the theory that still allow for obtaining some of the desired results. This could involve the use of more general notions of compactness, such as sequential compactness, or the imposition of additional constraints on G or the state space to recover some of the lost properties.

In summary, the lack of relative compactness in T could limit the applicability of certain theoretical results and complicate the analysis of the discrete dynamical system. However, it could also motivate the development of more general or alternative versions of the theory, leading to new ideas and research directions.

Lemma 5.10. Every inverse algebraic tree satisfying K-bounded growth for some has relative compactness under the metric d.

Proof. Let T be an inverse algebraic tree with K-bounded growth. By hypothesis, such that .

Defining

such that

is the maximum number of nodes in the subtree rooted at

v, since by hypothesis there can be at most

K children per node, we have:

Hence, f is bounded. Therefore, by the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, which states that every bounded sequence in has a convergent subsequence, it follows that:

Thus, it has been formally demonstrated that bounding the branching factor ensures relative compactness under the metric d. □

Theorem 5.11 (Absence of Anomalous Cycles).

Let be a discrete dynamical system and the algebraic inverse tree recursively constructed from the analytical inverse G. Then T does not contain any non-trivial anomalous cycle. That is:

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and be the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G. We will prove by contradiction that T does not contain any non-trivial anomalous cycles.

Step 1: Assume, for contradiction, that there exists a non-trivial anomalous cycle

in

T.

Step 2: By the recursive construction of

T through the injective function

G, each node in

T has a unique parent.

Step 3: Consider two consecutive nodes and in the cycle . By Step 2, has a unique parent in T, which must be according to the cycle’s definition.

Step 4: However, by Step 2, also has a unique parent in T outside the cycle, as the tree extends infinitely upwards from each node.

Step 5: This leads to a contradiction, as

cannot have two distinct parents in

T due to the injectivity of

G. More formally:

Step 6: Therefore, the assumption in Step 1 must be false, and there cannot exist a non-trivial anomalous cycle

in

T.

Thus, the absence of non-trivial anomalous cycles in the inverse algebraic tree T is formally proven by contradiction. □

Theorem 5.12 (Universal Convergence in AIT). Let be an Algebraic Inverse Tree constructed from a Discrete Dynamical System with the analytic inverse function G. Then, for every infinite path in T, P converges to either the root node r or the point of contact .

Proof. Step 1: Define the convergence of a path.

where

is the set of all paths in

T, and

d is the graph distance in

T.

Step 2: Prove that every node has a unique path to either the root or the point of contact.

where

denotes the

i-th node in the path

P.

This follows from the recursive construction of T using the injective function G.

Step 3: Prove that every infinite path is a Cauchy sequence.

This follows from the monotonically decreasing distances between consecutive nodes in P, due to the unique path property.

Step 4: Prove that

T is complete.

This follows from the finiteness of paths between any node and the root or the point of contact, and the completeness of with the usual metric.

Step 5: Conclude that every infinite path converges to either the root or the point of contact.

This follows from Steps 3 and 4, as every infinite path is a Cauchy sequence in the complete space T, and thus converges to a unique limit, which must be either the root node r or the point of contact by the unique path property.

Therefore, we have proven that every infinite path in the Algebraic Inverse Tree T converges to either the root node r or the point of contact , considering the impact of the failure of multivalued injectivity at . □

Theorem 5.13 (Unique AIT Generation). Let be a discrete dynamical system and its analytic inverse. It is proven that:

If G satisfies:

Injectivity Surjectivity Exhaustiveness Then, the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively applying G is unique and satisfies:

Absence of anomalous cycles: non-trivial cycle in T Universal convergence of trajectories: where r is the root.

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and its analytic inverse. It is proven that:

Where r denotes the root node of the inverse algebraic tree constructed by iterations of G.

Assuming that G satisfies injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness, absence of cycles and universal convergence in T are proven:

Absence of anomalous cycles: Suppose , a non-trivial cycle in T. By the injectivity hypothesis, . Taking consecutive nodes , a contradiction is obtained non-trivial cycle.

Universal convergence: , by exhaustiveness of G, such that . That is, .

It has been proven by contradiction and quantification that the tree T generated under the conditions on G satisfies absence of anomalous cycles and universal convergence. □

6. Properties of the Inverse Function G in a DIDS

Given that a discrete dynamical system

is a DIDS if and only if

is a deterministic and surjective function, we can derive several important properties of the inverse function

defined as:

Theorem 6.1. If is a DIDS, then the inverse function satisfies the following properties:

-

(1)

Injectivity:

-

(2)

Surjectivity:

-

(3)

Exhaustiveness:

Proof. The proof follows directly from the determinism and surjectivity of F, as demonstrated in Theorem 5.1. □

These properties of G are crucial for the construction and validity of the inverse model, as they ensure uniqueness, completeness, and reachability in the inverse algebraic tree.

6.1. Injectivity of G

The injectivity of G guarantees that each state in the inverse model has a unique corresponding state in the original system, preventing ambiguities or inconsistencies in the transfer of properties.

6.2. Surjectivity of G

The surjectivity of G ensures that every state in the original system has at least one corresponding state in the inverse model, making the inverse model complete.

6.3. Exhaustiveness of G

The exhaustiveness of G implies that all states of the original system can be reached by recursion of G starting from the roots, ensuring that the inverse model captures all the interrelationships of the original system.

7. Constructibility of the Inverse Model

Theorem 7.1 (Conditions for Inverse Model Constructibility). Given a DIDS , the inverse model in the form of an inverted algebraic tree constructed recursively from the inverse function G is constructible.

Proof. The constructibility of T follows directly from the injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness of G, which are guaranteed by the determinism and surjectivity of F. □

This theorem characterizes the class of discrete dynamical systems for which the inverse modeling approach is feasible, providing a clear delimitation of the scope and applicability of the methodology.

8. Uniqueness of the Inverse Model

The injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness of the inverse function G also ensure the uniqueness of the inverse model, even when dealing with a forest of inverse trees.

Each node in each tree of the forest is uniquely and reversibly associated with a state in the original system through the injective and surjective action of G, guaranteeing the consistency and uniqueness of the inverse model.

9. Decidable Inference and Property Transfer

The injectivity and surjectivity of G establish a discrete homeomorphism between the state space of the original system and the set of nodes of the inverse algebraic tree, enabling the decidable and complete transfer of properties between the inverse model and the original system.

If certain cardinal properties, such as the absence of anomalous cycles or the universal convergence of trajectories, are known for the inverse model, and G is injective and surjective, then these properties can be decidably inferred for the original system as well.

Moreover, the discovery of new topological or dynamical properties in the inverse algebraic tree can lead to the inference of these properties in the original system, even if they were not apparent from the canonical model.

10. Convergence in DIDS

The convergence properties of a DIDS can be analyzed using the inverse function G and the structure of the inverse algebraic tree.

10.1. Finite Case

Theorem 10.1. If is a DIDS with a finite state space S, then F converges to a fixed point for each initial state.

Proof. The proof follows from the injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness of G, which guarantee that any sequence of states generated by F must eventually reach a fixed point, as there can be no non-trivial cycles in the finite state space. □

10.2. Countably Infinite Case

Theorem 10.2. If is a DIDS with a countably infinite state space S, then for each initial state , either:

-

(1)

F converges to a fixed point starting from s, or

-

(2)

F enters a cycle starting from s.

Proof. The proof relies on the injectivity and exhaustiveness of G, which ensure that any sequence of states generated by F must either reach a fixed point or enter a cycle, as there can be no infinite non-repeating sequences in the inverse model. □