1. Introduction of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive and degenerative neurological disorder that primarily affects the brain [

1], leading to cognitive decline and memory impairment. It is the most common cause of dementia among older adults. Alzheimer’s disease gradually and damages brain cells, resulting in a range of cognitive and behavioral symptoms that worsen over time [

2].

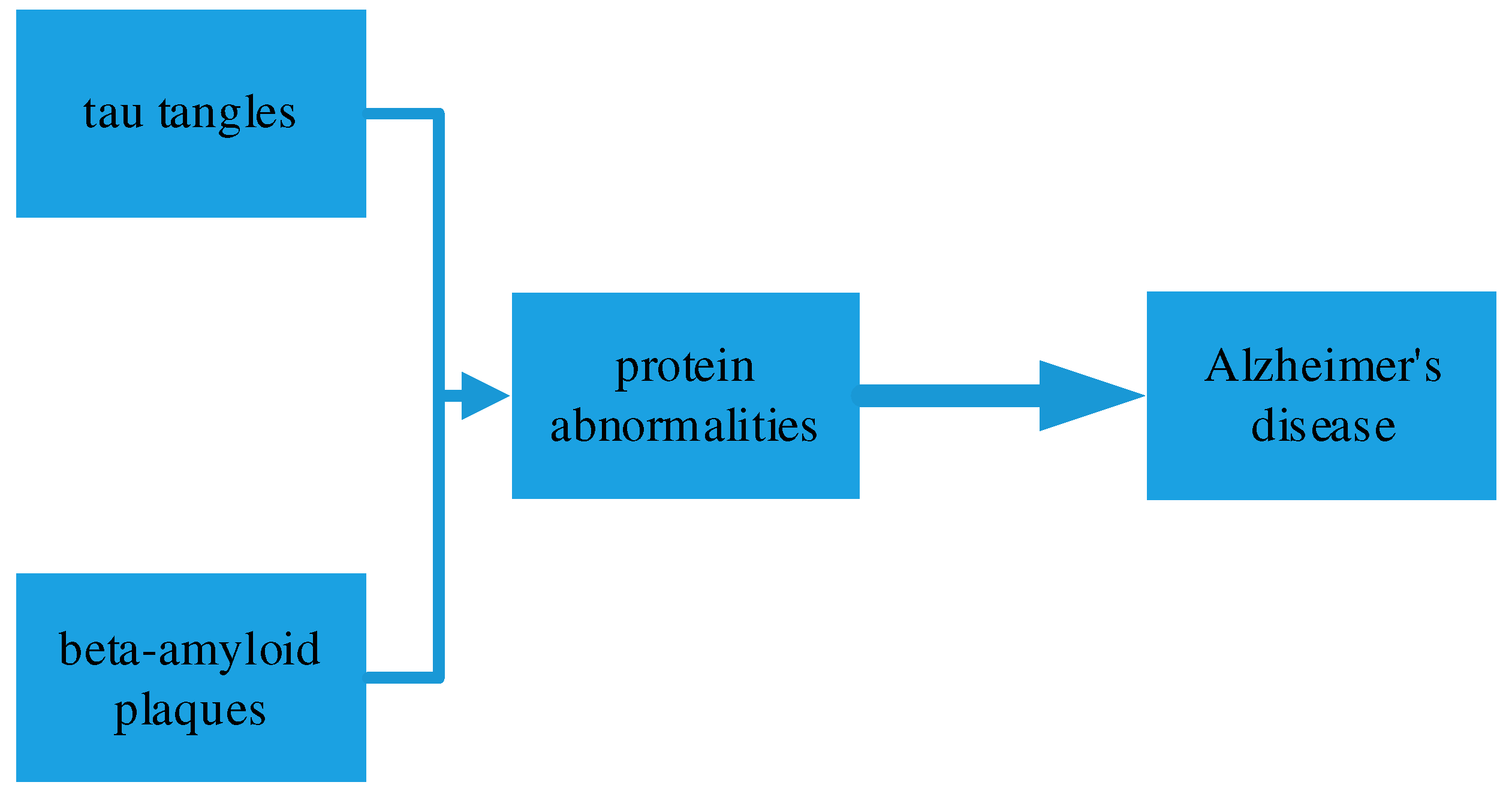

The hallmark pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease include the accumulation of abnormal protein deposits in the brain. Two main types of protein abnormalities are observed: beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles[

3], As shown in

Figure 1. Beta-amyloid plaques are clusters of misfolded beta-amyloid proteins that accumulate between nerve cells, disrupting communication and triggering inflammation. Tau tangles are twisted and abnormal tau proteins that build up inside nerve cells, leading to their dysfunction and eventual cell death.

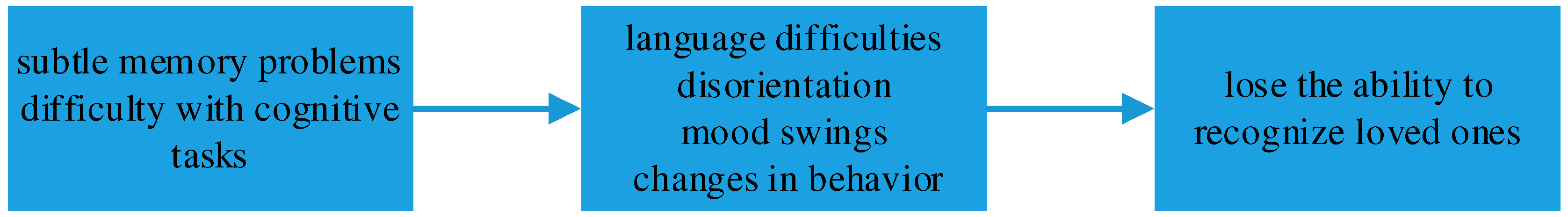

The progression of Alzheimer’s disease typically follows a predictable pattern, beginning with subtle memory problems and difficulty with cognitive tasks [

4]. As the disease advances, individuals may experience language difficulties, disorientation, mood swings, and changes in behavior. In later stages, individuals with Alzheimer’s may require assistance with daily activities and lose the ability to recognize loved ones, As shown in

Figure 2.

The exact cause of Alzheimer’s disease remains unclear, but it is likely due to a combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. While age is the most significant risk factor (the disease predominantly affects individuals over 65), a family history of Alzheimer’s can also increase the risk. Additionally, certain genetic mutations are associated with a higher likelihood of developing the disease[

5,

6].

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Treatment options focus on managing symptoms and may include medications to improve cognitive function or address behavioral symptoms temporarily. Supportive care, such as counseling and assistance with daily tasks, is crucial to maintain the quality of life for individuals with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers. Ongoing research into the underlying mechanisms and potential treatments continues in the quest to find a cure or more effective interventions for this devastating condition[

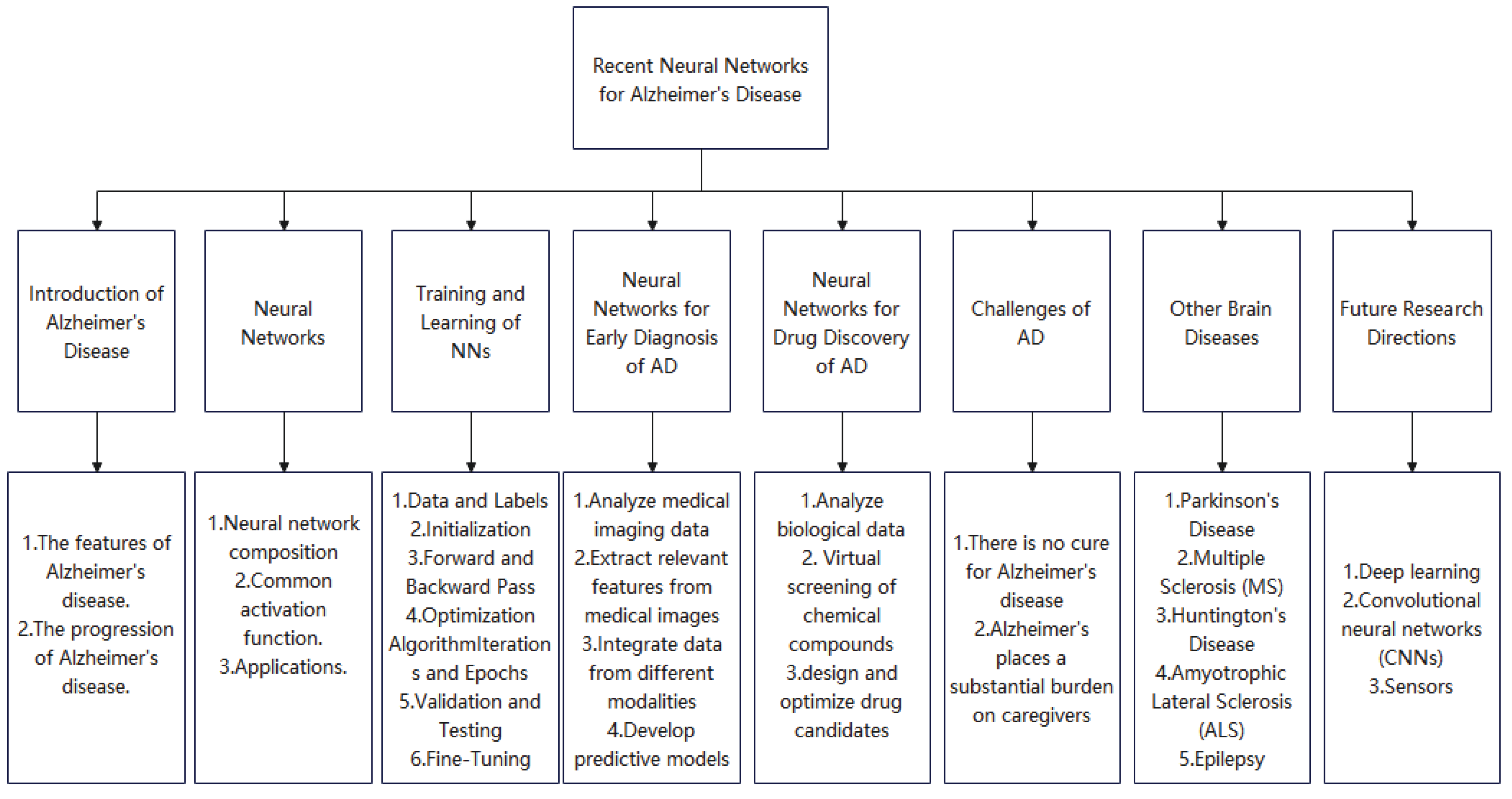

7]. Paper structure is shown in

Figure 3.

2. Neural Networks

A neural network is a computational model inspired by the structure and function of the human brain. It is a type of machine learning [

8] algorithm that processes information in a way that mimics the functioning of biological neural networks [

9]. Neural networks are a fundamental component of deep learning, a subfield of artificial intelligence (AI) [

10].

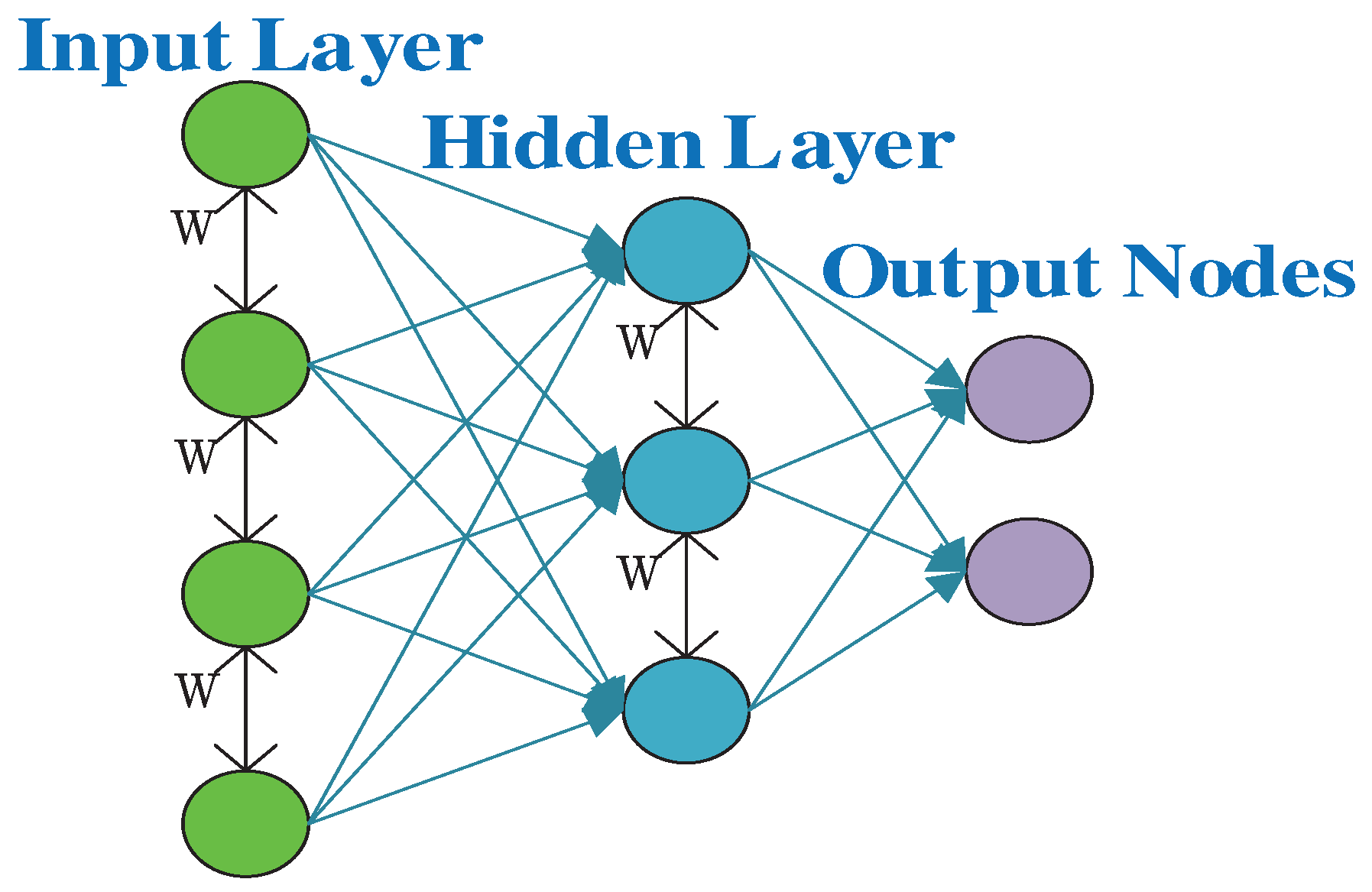

At its core, a neural network is composed of interconnected nodes called neurons or artificial neurons. These neurons are organized into layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Information flows through the network from the input layer, passes through the hidden layers, and produces an output from the output layer[

11]. Each connection between neurons is associated with a weight, which determines the strength of the connection, As shown in

Figure 4.

Neurons within a neural network apply an activation function to the weighted sum of their inputs. This activation function introduces non-linearity into the model, allowing neural networks to learn complex patterns and representations. Common activation functions include sigmoid[

12], ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit)[

13], and tanh (hyperbolic tangent)[

14], The advantages and drawbacks of each activation function are as shown in

Table 1.

Neural networks learn from data through a process called training. During training, the network adjusts the weights of its connections based on the error between its predictions and the actual target values[

15]. The objective is to minimize this error, typically using optimization techniques like gradient descent[

16]. Neural networks learn by iteratively updating their weights, making them more accurate in making predictions or classifications.

Deep neural networks, often referred to as deep learning models, consist of multiple hidden layers[

17]. They have proven to be particularly effective in tasks like image recognition, natural language processing, and playing complex games. Deep learning models are capable of learning hierarchical representations, enabling them to capture intricate patterns in data.

Neural networks find applications in a wide range of fields, including computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing, recommendation systems, autonomous vehicles, and medical diagnosis. They have made significant advancements in areas such as image classification (e.g., convolutional neural networks or CNNs) [

18], language understanding (e.g., recurrent neural networks or RNNs) [

19], and reinforcement learning (e.g., in training game-playing agents) [

20].

In summary, a neural network is a computational model that emulates the interconnected structure of biological neurons. It learns from data by adjusting the strengths of connections between neurons and has found extensive applications in AI and machine learning, particularly in deep learning models with multiple layers. Neural networks are capable of tackling complex and diverse tasks, making them a fundamental technology in modern AI research and applications.

3. Training and Learning of NNs

Training and learning are fundamental processes in the development of neural networks. Neural networks, especially deep neural networks, are designed to learn from data and improve their ability to make predictions or classifications over time [

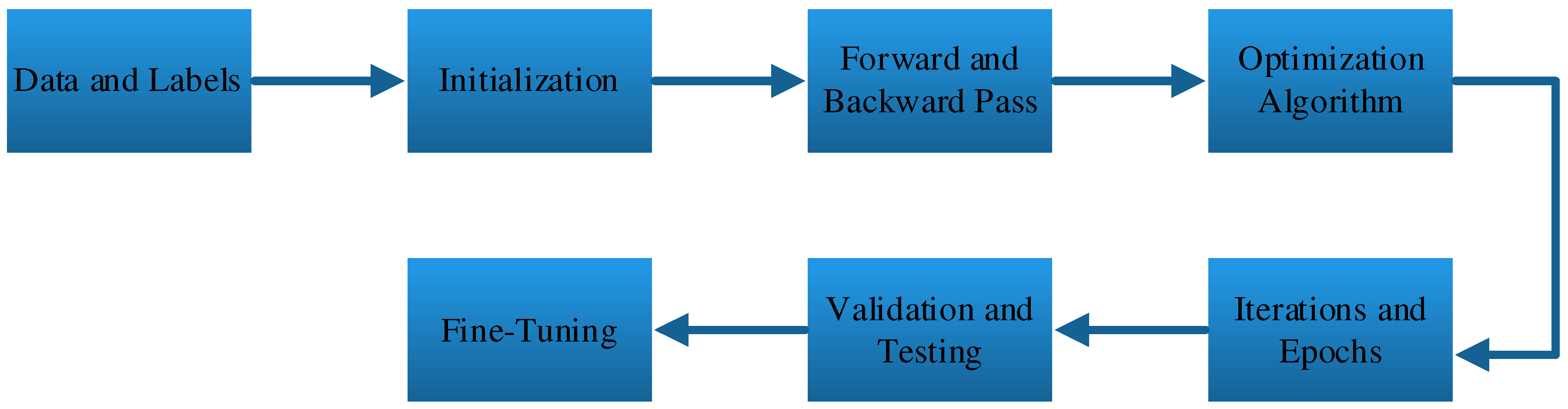

21]. Here’s an explanation of training and learning in neural networks, As shown in

Figure 5.

The training process of a neural network starts with a dataset that includes input data and corresponding labels or target values. The input data can be any form of information, such as images, text, or numerical values, depending on the nature of the problem. The labels represent the correct answers or desired outputs associated with the input data [

22]. For example, in an image classification task, the input data may be images of different objects, and the labels would indicate the object in each image.

Before training begins, the neural network is initialized with random weights and biases [

23]. These initial weights have no relation to the task at hand and are the starting point for learning. During training, the network will adjust these weights to improve its performance on the given dataset.

The training process consists of iteratively performing forward and backward passes through the network. In the forward pass, the input data is fed through the network, and the network makes predictions or classifications based on its current weights. These predictions are compared to the true labels, and an error (or loss) is calculated to quantify the difference between the predicted and actual values. The backward pass (also known as backpropagation[

24]) involves calculating the gradients of the loss with respect to the network’s parameters (weights and biases) and using these gradients to update the parameters.

To update the network’s parameters in the right direction, an optimization algorithm is employed. Gradient descent is a common optimization technique used in neural network training. It adjusts the weights and biases in a way that minimizes the loss function. Other variations of gradient descent, such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and Adam[

25], are often used to accelerate and improve the training process.

Training is an iterative process, and multiple passes through the entire dataset (one pass is called an epoch) are typically required. During each epoch, the network updates its parameters based on the gradients computed from the entire dataset or a subset of it (mini-batch) [

26]. The number of epochs and the learning rate (a hyperparameter[

27]that controls the size of weight updates) are key factors that influence the learning process. Training continues until the loss converges to a satisfactory level or until a predetermined number of epochs is reached.

After training, the neural network is evaluated on separate validation and test datasets to assess its generalization performance. The validation dataset helps in tuning hyperparameters and preventing overfitting, while the test dataset provides an independent evaluation of the model’s performance[

28].

If the model’s performance is not satisfactory, adjustments may be made, such as changing the architecture of the network, modifying hyperparameters, or collecting more data. This iterative process of training, evaluation, and fine-tuning continues until the desired level of performance is achieved[

29].

4. Neural Networks for Early Diagnosis of AD

Neural networks [

30] can assist in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease by analyzing various types of data and detecting patterns associated with the disease [

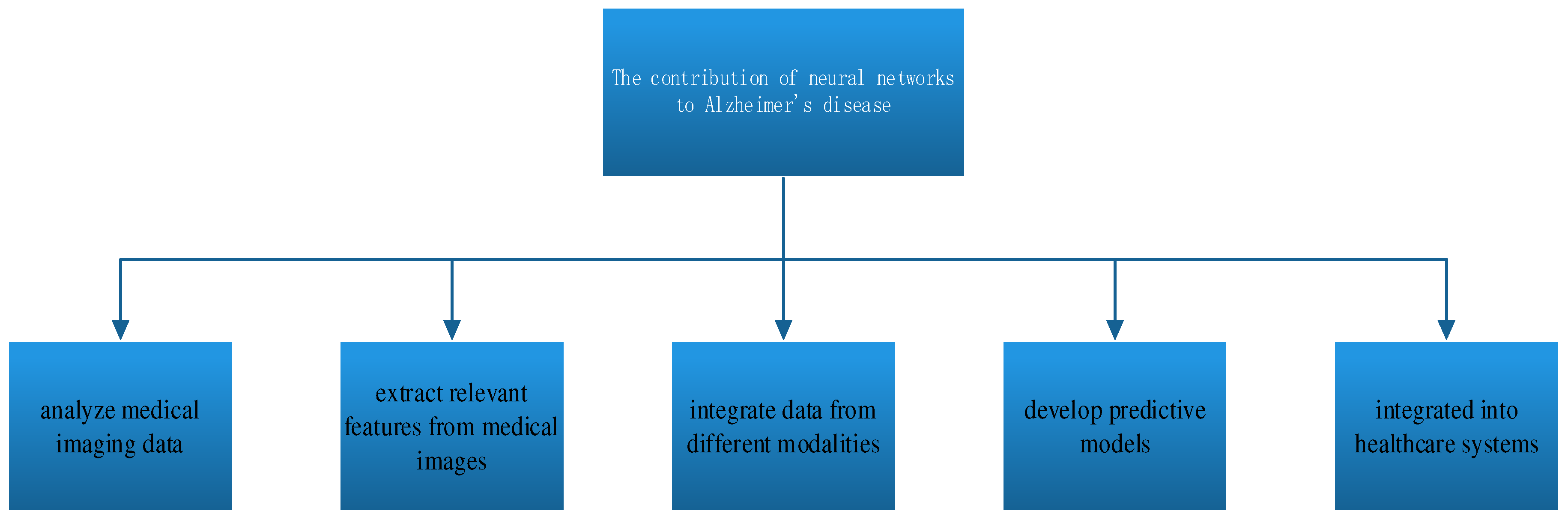

31]. Here’s how neural networks contribute to Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, As shown in

Figure 6.

Neural networks can analyze medical imaging data, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) scans of the brain[

32]. These models can learn to recognize specific patterns, such as the presence of beta-amyloid plaques or brain atrophy, which are indicative of Alzheimer’s disease[

33]. By quantifying these patterns, neural networks help radiologists and clinicians make more accurate and early diagnoses.

Neural networks can automatically extract relevant features from medical images, reducing the need for manual image interpretation [

34]. This feature extraction process can uncover subtle changes in brain structure and function that might not be evident to the human eye [

35,

36].

Alzheimer’s diagnosis often relies on multiple sources of information, including imaging, clinical assessments, and genetic data. Neural networks can integrate data from these different modalities, providing a more comprehensive view of the patient’s condition. Multi-modal models can improve diagnostic accuracy by considering a wider range of information [

37].

Neural networks can develop predictive models that estimate the likelihood of a patient having Alzheimer’s disease based on their medical history, cognitive test results, and other clinical parameters [

38]. These models use machine learning algorithms to weigh different factors and make predictions, assisting clinicians in making informed diagnostic decisions.

In some cases, neural networks can be integrated into healthcare systems to automate the initial screening of individuals for Alzheimer’s disease risk[

39]. For example, automated cognitive assessment tools based on neural networks can quickly evaluate memory and cognitive function, identifying individuals who may benefit from further diagnostic evaluation.

5. Neural Networks for Drug Discovery of AD

Neural networks and machine learning techniques [

40] play a crucial role in drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease by accelerating identifying potential drug candidates and optimizing their properties [

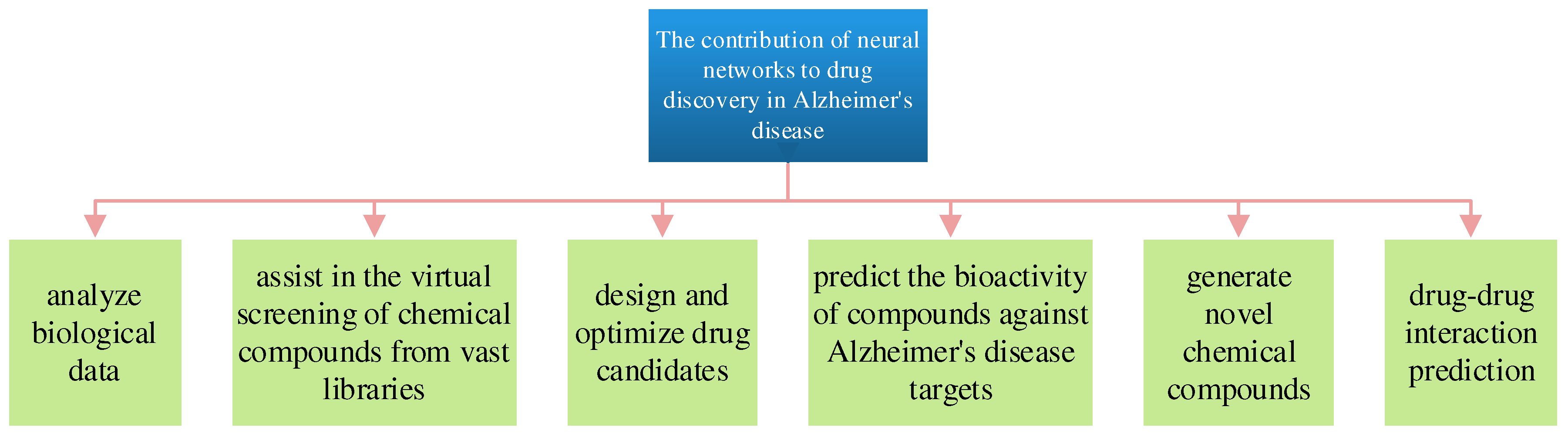

41]. Here’s how neural networks contribute to drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease, As shown in

Figure 7.

Neural networks can analyze biological data, such as genomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics data, to identify potential molecular targets implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. By mining large datasets, these models can uncover associations between genes, proteins, and disease pathways, aiding researchers in selecting promising drug targets[

42].

Neural networks assist in the virtual screening of chemical compounds from vast libraries. These models predict the binding affinity of compounds to specific protein targets associated with Alzheimer’s disease, such as beta-amyloid or tau proteins [

43]. This accelerates the identification of potential drug candidates, saving time and resources compared to traditional experimental screening.

Neural networks are used to design and optimize drug candidates by predicting their pharmacokinetic properties, toxicity, and bioavailability[

44]. These models guide medicinal chemists in modifying molecular structures to enhance drug efficacy while minimizing side effects.

Neural networks can predict the bioactivity of compounds against Alzheimer’s disease targets, helping prioritize compounds that are most likely to have therapeutic effects [

45]. These models take into account structural features, chemical properties, and historical bioactivity data.

Generative neural networks, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs), are used to generate novel chemical compounds with desired properties [

46]. This approach aids in the exploration of new chemical space and the discovery of innovative drug candidates for Alzheimer’s disease.

Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction: Neural networks can predict potential drug-drug interactions and assess the safety of combining Alzheimer’s disease drugs with other medications that patients may be taking. This is essential for minimizing adverse effects and ensuring patient safety [

47].

6. Other Brain Diseases

There are numerous brain diseases and disorders that can affect the structure and function of the brain, as shown in

Figure 8, leading to a wide range of neurological and cognitive symptoms. Some of these brain diseases include:

Parkinson’s Disease: Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. It leads to motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and postural instability [

48].

Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS), leading to demyelination of nerve fibers. This results in a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, muscle weakness, coordination problems, and sensory disturbances [

49].

Huntington’s Disease: Huntington’s disease is a genetic disorder that causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. It leads to motor dysfunction, cognitive decline, and psychiatric symptoms [

50].

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. It leads to muscle weakness, paralysis, and eventual respiratory failure [

51].

Epilepsy: Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, which are abnormal electrical discharges in the brain. Seizures can vary in severity and may involve loss of consciousness and convulsions[

52].

7. Challenges of AD

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, and its course can vary widely among individuals. Predicting how the disease will progress in a particular person is difficult, making it challenging to plan for long-term care and support.

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Available medications may provide temporary relief from symptoms, but they do not alter the course of the disease or address its underlying causes. Developing effective disease-modifying treatments remains a significant challenge.

Alzheimer’s places a substantial burden on caregivers, often family members, who provide care and support to individuals with the disease. Caregivers face emotional, physical, and financial challenges while managing the daily needs of their loved ones [

53].

There is still a stigma associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Misconceptions and lack of awareness can lead to social isolation and discrimination against individuals living with the disease [

54].

Alzheimer’s disease imposes significant healthcare costs on individuals and society. Costs include medical expenses, long-term care, and lost productivity. As the global population ages, these costs are expected to rise dramatically.

8. Discussion and Conclusion

In conclusion, the application of neural networks in the context of Alzheimer’s disease holds significant promise for both diagnosis and drug discovery. Neural networks have demonstrated their effectiveness in several critical areas related to Alzheimer’s disease:

Neural networks can analyze medical imaging data and clinical information to assist in the early detection and accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. This early detection is crucial for timely intervention and improved patient outcomes.

These models can develop predictive models that estimate an individual’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease [

55], enabling personalized preventive strategies and interventions.

Neural networks play a vital role in accelerating drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease by screening chemical compounds, optimizing drug candidates, and predicting compound bioactivity. These contributions expedite the development of potential treatments.

Despite these promising contributions, it’s essential to recognize that neural networks are not a panacea for Alzheimer’s disease. They work in conjunction with healthcare professionals, researchers, and other tools to enhance the diagnostic and therapeutic processes. Ethical considerations, data privacy, and clinical validation remain important aspects of their implementation.

9. Future Research Directions

Furthermore, ongoing research and collaboration are necessary to advance further the field of neural networks in Alzheimer’s disease. Addressing challenges related to data availability, model interpretability, and the complexity of the disease itself are essential steps in harnessing the full potential of these technologies.

Deep learning can aid in the recognition of Alzheimer’s disease by analyzing complex patterns in medical imaging data, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

56] can automatically extract intricate features from brain images, identifying subtle structural changes and abnormalities associated with Alzheimer’s. Additionally, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) [

57] can analyze temporal sequences [

58] of cognitive assessments and clinical data, detecting trends and anomalies indicative of cognitive decline. By leveraging large datasets and deep learning architectures, these techniques offer the potential for earlier and more accurate Alzheimer’s diagnosis, assisting clinicians in providing timely interventions and personalized treatment plans.

Sensors [

59] can play a crucial role in recognizing Alzheimer’s disease by monitoring various physiological and behavioral markers. For instance, wearable sensors and smart devices can track changes in gait, balance, and mobility, which are often affected in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. Additionally, sensors can capture data related to sleep patterns, heart rate variability [

60], and daily activity levels, providing valuable insights into an individual’s cognitive health. Furthermore, environmental sensors can detect anomalies in daily routines, such as forgetting to turn off appliances or leaving doors open, signaling potential cognitive decline. Integrating data from these sensors and employing machine learning algorithms to analyze patterns can assist in early detection, enabling timely intervention and improved management of Alzheimer’s disease,As shown in

Table 2.

Ultimately, the integration of neural networks and other advanced technologies into Alzheimer’s disease research and clinical practice offers hope for improved diagnosis, treatment, and care for individuals affected by this devastating condition. Continued innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration will be key to addressing the global challenge of Alzheimer’s disease effectively.

Funding

This research did not receive any grants.

Acknowledgment

We thank all the anonymous reviewers for their hard reviewing work.

References

- Monfared, A.A.T.; Byrnes, M.J.; White, L.A.; Zhang, Q. Alzheimer’s disease: epidemiology and clinical progression. Neurology and therapy 2022, 11, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirakhori, F.; Moafi, M.; Milanifard, M.; Tahernia, H. . Diagnosis and Treatment Methods in Alzheimer’s Patients Based on Modern Techniques: The Orginal Article. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results 2022, 1889–1907. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch, M.; Franchi, B.; Tesi, M.C.; Tora, V. . The role of beta-amyloid and tau proteins in Alzheimer’s disease: a mathematical model on graph. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.13868. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, O.; Coleman, M. . Alzheimer’s disease: etiology, neuropathology and pathogenesis. Exon Publications 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.R.; Holtzman, D.M.J.N. Biomarker modeling of Alzheimer’s disease. 2013, 80, 1347–1358.

- Reitz, C.; Rogaeva, E.; Beecham, G.W. . Late-onset vs nonmendelian early-onset Alzheimer disease: A distinction without a difference? Neurology Genetics 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benek, O.; Korabecny, J.; Soukup, O. A perspective on multi-target drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2020, 41, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-H.; Zhang, Y.-D. Advances and Challenges of Deep Learning. Recent Patents Eng. 2023, 17, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithiga, G.; Mohan, V.; Senthilkumar, S. A Brief Review of the Development Path of Artificial Intelligence and Its Subfields. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Grad-CAM: Understanding AI Models. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 76, 1321–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Nair, S.; Joshi, R.; Chitre, V. Residual-concatenate neural network with deep regularization layers for binary classification. 2022 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS); 2022; pp. 1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Atamanalp, S.S. Endoscopic Decompression of Sigmoid Volvulus: Review of 748 Patients. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2022, 32, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Ahmed, M.F.; Ali, M.O.; Jang, Y.M. Self-gated rectified linear unit for performance improvement of deep neural networks. ICT Express 2023, 9, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxhaku, B.; Agrawal, P.N. Neural network operators with hyperbolic tangent functions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 226, 119996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brion, D.A.J.; Pattinson, S.W. Generalisable 3D printing error detection and correction via multi-head neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.M.; Ghorbani, B.; Krishnan, S.; Agarwal, N.; Medapati, S.; Badura, M.; Suo, D.; Cardoze, D.; Nado, Z.; Dahl, G.E.; et al. . Adaptive gradient methods at the edge of stability. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.14484. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, G.; Huang, F.; Qin, H.; Wang, B.; Yi, L. Directed graph deep neural network for multi-step daily streamflow forecasting. J. Hydrol. 2022, 607, 127515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Hong, D.; Cai, W.; Yu, C.; Yang, N.; Cai, W. Multi-feature fusion: Graph neural network and CNN combining for hyperspectral image classification. Neurocomputing 2022, 501, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzin, S.; Bova, V.; Kravchenko, Y.; Rodzina, L. . Deep learning techniques for natural language processing. Computer Science On-line Conference; 2022; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Biagiola, M.; Tonella, P. Testing of Deep Reinforcement Learning Agents with Surrogate Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.12751. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Lu, C.; Protgnn, C.L. Protgnn: Towards self-explaining graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2022; pp. 9127–9135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, S.; Sun, S.; Zhu, Z.; Gorriz, J.M.; et al. Deep learning in food category recognition. Inf. Fusion 2023, 98, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. Bionic Artificial Neural Networks in Medical Image Analysis. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kushwaha, S.; Alarfaj, M.; Singh, M. Comprehensive Overview of Backpropagation Algorithm for Digital Image Denoising. Electronics 2022, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beznosikov, A.; Gorbunov, E.; Berard, H.; Loizou, N. . Stochastic gradient descent-ascent: Unified theory and new efficient methods. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; 2023; pp. 172–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Wu, L.; Weinan, E. . A qualitative study of the dynamic behavior for adaptive gradient algorithms. In Mathematical and Scientific Machine Learning; 2022; pp. 671–692. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, A. Impact of Hyperparameters on Deep Learning Model for Customer Churn Prediction in Telecommunication Sector. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.; Ganguly, A.; Mohiuddin, S.; Malakar, S.; Sarkar, R. ViXNet: Vision Transformer with Xception Network for deepfakes based video and image forgery detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 210, 118423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Wei, F.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chan, C.-M.; Chen, W.; et al. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large-scale pre-trained language models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. Deep Learning for COVID-19 Diagnosis via Chest Images. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 76, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.L.; Moustafa, A.A. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, deep learning, and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Journal of Neuroimaging 2023, 33, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Ma, L.; Yang, L.; Lu, R.; Xi, C. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm-Based Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in the Treatment of Glioma Biopsy. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvamangala, D.R.; Kulkarni, R.V. Convolutional neural networks in medical image understanding: a survey. Evol. Intell. 2022, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Fingerspelling identification for Chinese sign language via AlexNet-based transfer learning and Adam optimizer. Scientific Programming 2020, 2020, 3291426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cai, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, D.D.; Chen, M. . Medical image classification with convolutional neural network. 2014 13th international conference on control automation robotics & vision (ICARCV); 2014; pp. 844–848. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, W. N.; PP, F. R.; Ali, M. A. A Meta-Heuristic Multi-Objective Optimization Method for Alzheimer’s Disease Detection Based on Multi-Modal Data. Mathematics 2023, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisely, C.E.; Wang, D.; Henao, R.; Grewal, D.S.; Thompson, A.C.; Robbins, C.B.; Yoon, S.P.; Soundararajan, S.; Polascik, B.W.; Burke, J.R.; et al. Convolutional neural network to identify symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease using multimodal retinal imaging. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 106, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, T.; Yao, Z.; Khleifat, A.A.; Tantiangco, H.; Tamburin, S.; Albertyn, C.; Thakur, L.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Oxtoby, N.P.; Lourida, I.; et al. Artificial intelligence for dementia drug discovery and trials optimization. Alzheimer's Dement. 2023, 19, 5922–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kute, S.S.; Madhav, A.S.; Kumari, S.; Aswathy, S. . Machine Learning–Based Disease Diagnosis and Prediction for E-Healthcare System. Advanced Analytics and Deep Learning Models 2022, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, J.; Chen, S. Medical Big Data and Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Rabl, M.; Dayon, L.; Popp, J. The promise of multi-omics approaches to discover biological alterations with clinical relevance in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1065904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadood, A.; Ajmal, A.; Junaid, M.; Rehman, A.U.; Uddin, R.; Azam, S.S.; Khan, A.Z.; Ali, A. Machine Learning-based Virtual Screening for STAT3 Anticancer Drug Target. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 3023–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, B.; Goel, M.; Priyakumar, U.D. Modern machine learning for tackling inverse problems in chemistry: molecular design to realization. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5316–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Santos, B.P.; Pereira, T.C.; Sofia, R.; Monteiro, N.R.C.; Simões, C.J.V.; Brito, R.M.M.; Ribeiro, B.; Oliveira, J.L.; Arrais, J.P. Designing optimized drug candidates with Generative Adversarial Network. J. Chemin- 2022, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V.; Gaurav, A.; Masand, N.; Lee, V.S.; Patil, V.M. Artificial intelligence and machine-learning approaches in structure and ligand-based discovery of drugs affecting central nervous system. Mol. Divers. 2022, 27, 959–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-H.; Hsieh, K.-L.; Jiang, X.; Kim, Y. Integrating Comorbidity Knowledge for Alzheimer's Disease Drug Repurposing using Multi-task Graph Neural Network. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings 2023, 2023, 378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhang, W. Enhancing Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction Using Deep Attention Neural Networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Dobkin, R.D.; Leentjens, A.F.; Rodriguez-Violante, M.; Schrag, A. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson's disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 21, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmosayyeb, O.; Shaygannejad, V.; Bagherieh, S.; Hosseinabadi, A.M.; Ghajarzadeh, M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 43, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Estevez-Fraga, C.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; Flower, M.D.; I Scahill, R.; Wild, E.J.; Muñoz-Sanjuan, I.; Sampaio, C.; E Rosser, A.; Leavitt, B.R. Potential disease-modifying therapies for Huntington's disease: lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, M.E.; Adhikari, S.; Halden, R.U. Systematic and state-of the science review of the role of environmental factors in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig's Disease. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 817, 152504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, A.M.; Bicchi, M.M. Antiseizure medications for adults with epilepsy: a review. Jama 2022, 327, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, B.M.; Hudson, P.; Hanson, L.C.; Bužgovà, R.; Creutzfeldt, C.J.; Gursahani, R.; et al. Palliative care to support the needs of adults with neurological disease. The Lancet Neurology 2023, 22, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenzek, K.E.; Lapan, E.; Ophir, Y.; Lattimer, T.A. Staying connected: Alzheimer's hashtags and opportunities for engagement and overcoming stigma. J. Aging Stud. 2023, 66, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Dawar, V.; Bhargava, S.; Markan, R.; Sharma, S.; Chawla, S.; Nayyar, A.; Brooks, L.; Gaur, A.; Kukreja, I.; et al. RWD121 Developing a Risk Prediction Model for the Early Identification of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in Elderly Patients. Value Heal. 2023, 26, S383–S384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-D.; Satapathy, S.C.; Zhu, L.-Y.; Gorriz, J.M.; Wang, S.-H. A Seven-Layer Convolutional Neural Network for Chest CT-Based COVID-19 Diagnosis Using Stochastic Pooling. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22, 17573–17582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Shen, D.; Li, Y. Aggregate Investor Attention and Bitcoin Return: The Long Short-term Memory Networks Perspective. Finance Res. Lett. 2022, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqr, M.; López-Pernas, S. The temporal dynamics of online problem-based learning: Why and when sequence matters. Int. J. Comput. Collab. Learn. 2023, 18, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gorriz, J.M.; Wang, S. Modern Forms and New Challenges in Medical Sensors and Body Area Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Networks 2022, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, A.S.; Day, B.D.; Scott, A.J.; Gnatiuk, E.A. Precision and reliability of the polar team pro computer software for analyzing heart rate variability. Sports Eng. 2023, 26, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).