I. Introduction

It is well known that when two waves meet, interference may occur. The occurrence of the interference needs certain conditions. Let us examine waves in classical mechanics and matter waves in quantum mechanics.

In the wave theory of classical mechanics, if there are two point vibration sources with the same vibration direction, their positions being at

and

, respectively. The waves they emit can be written as follows

In the area they encounter, the two waves superimpose.

After the superposition, the total wave intensity becomes

The in tensity at every position varies with time. Suppose that the two sources have the same vibration frequency:

In a medium, there is a relationship between frequency and wavelength. When two waves’ frequencies are the same, their wavelengths are same either:

Under the conditions (4) and (5), Eq. (3) is reduced to be

At any time, there is a fixed phase difference

between the two waves at every position. The strength varies with spatial coordinates but not with time. A stable interference pattern is formed, which is the interference of waves [

1].

There are three conditions for two waves to interference: their vibration directions are the same; their vibration frequencies are the same, and there is a fixed phase difference at each point in space. Note that the same frequency can also be said to be the same wavelength.

In quantum mechanics, microscopic particles are of wave-particle duality. The famous de Broglie relations link the physical quantities describing the properties of particles with those describing the properties of waves. When a particle has a momentum p, it has a corresponding wavelength, ; When it has an energy E, it has a corresponding frequency .

Due to the characteristics of wave, material waves can also interfere [2−21]. We examine if the three conditions for wave interference in classical mechanics apply to quantum mechanics. Matter waves do not have the concept of the vibration direction, so the condition of same vibration direction disappears for wave interfence in quantum mechanics. If two matter waves have the same de Broglie wavelength, interference will occur between two beams of particles.

In order to meet this condition, usually, a particle beam is separated into two or more partial beams. Then, the partial beams have the same wavelength and there is a fixed phase differences between them. After the partial beams go through some different paths, they encounter interference. There have been experiments showing this kind of interference. The simplest examples are the double-slit and multi-slit interference of electrons [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], double-slit interference of large molecules [

10], and interference of cold neutrons [

11]. The Davisson-Germer experiment [

12] was to let electrons incident on a crystal to yield diffraction. In verifying the Aharonov-Bohm effect [

13], an electron current was separated into two. The two currents bypassed a region where there was a magnetic field and then encountered interference [

14,

15,

16]. A further experiment was that each of the two separated electronic currents went through a Josephson junction [

17,

18], and then the two currents encountered interference, which could lead to an interference pattern similar to that of double-slit interference [

19,

20].

In fact, the key to forming a stable interference pattern is that at each space point, there is a phase difference between interference waves that does not change over time.

The quantum interference listed above has two features. One is that the interference waves are separated from a beam of particles emitted from source, which ensures that they have a fixed phase difference in every space point, so that a stable interference pattern can be formed. If two identical particle waves are from different sources, they can also encounter interference. There has been an exquisited experiment in this regard [

21]. Another feature is that interference quantum waves are identical particles. If two particles are distinguishable, can they interfere? No such experiment has been seen.

We believe that although there have been many quantum interference experiments, a comprehensive discussion of the interference mechanisms is desirable. It is necessary to explicitly write down the mathematical expressions for the interference mechanisms of matter waves in quantum mechanics. In this paper, we do not take into accout of spin. We point out that for two beams of particles of different masses, there is no interference; For idential particles, there are two interference mechanisms, one is called equal wavelength interference mechanism and the other is exchange effect interference mechanism. A special case is that when the both the mechanisms are met, which mechanism would actually work. We propose an experiment for making the distinction.

II. Two-particle interference in quantum mechanics

A wave function

ψ obeys the Schrödinger equation,

The particle density is defined by

The density’s derivative with respect to time is deduced from the Schrödinger equation,

For a single particle, the Hamiltonian is

When it is substituted into (9), one obtains the continuity equation,

where the current density is expressed by

In this paper, we always consider time-independent Hamiltonian, so that the time factor in the wave function can be separated

Hereafter, the time factor is dropped when we write the wave function.

The simplest case is that there is only kinetic energy in the Hamiltonian (10) and no potential energy. This is a free particle with momentum

p. Its wave function is

where the wave vector is

. The particle’s energy is

. By Eqs. (12) and (13), the current density is expressed by

The above are fundamental knowledges introduced in quantum mechanics textbooks.

Let us consider a two-particles system. The Hamiltonian is

This is substituted into (9) to get

where

Each momentum has a current density. The total current density is the sum of the

and

,

We merely consider the cases where the interaction between the particles can be neglected, such that the Hamiltonian is simplified to be

The Hamiltonian is time-independent. The stationary wave function follows the eigenequation

where

E is eigenenergy. We consider three cases.

-

A.

Two distinguishable particles

The wave function can be written as the product of the two single-particle wave functions:

The equation is substituted into (21) to get the energy

By Eqs. (22) and (9), the current densities of the two momenta are respectively

The total current density is

When there are N free particles, the total wave function is the product of the N free-particle wave functions, . Then, from the Hamiltonian of the N free particles, one obtaines that on the right hand side of (24b), there are N terms. It is natural that the total current is .

Equation (24) shows that the current in space is a constant. The density calculated from the wave function (22) by Eq. (8) is also a constant everywhere. Therefore, when two particle waves of different masses encounter, no interference occurs.

-

B.

Two identical particles withand with no exchange effect

In the case of identical particles, the two masses in Eqs. (16)-(19) are the same

When their de Broglie wave vectors are the same,

the total wave function can be written as the linear superposition of the two single-particle wace functions,

Using (27) in (21), we chieve the energy:

By eqs. (27) and (8), the particle density is

It varies in space but independent of time. So, a stationary interference pattern is formed. Equation (29) seems formally similar to (6), but their expressions of phase difference are not the same. In (29), the fixed phase difference is , which is just the difference of the phases in the two terms in the wave function (27). When (27) is substituted into (18), the expression of the total current density has also this phase difference.

Thus, interference occurs between two beams of identical particles, provided that their de Broglie wavelengths are equal, see (26). This interference mechanism can be called equal wavelength interference mechanism. The experiments [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] mentioned above belong to this mechanism.

Suppose that three particle beams with the same de Broglie wave length encounter. The Hamiltonian is and the wave functions contains three terms, , . The corresponding energy is still (28). In the superposition area, the expression of the particle density has three fixed phase differences: , , and . The interference pattern is the superposition of those with three periods. If there are N particles with differenct momenta, the total wave function of the linear combination of N sinlge-particle wave functions. The corresponding energy is still (28), and the number of fixed phase difference is .

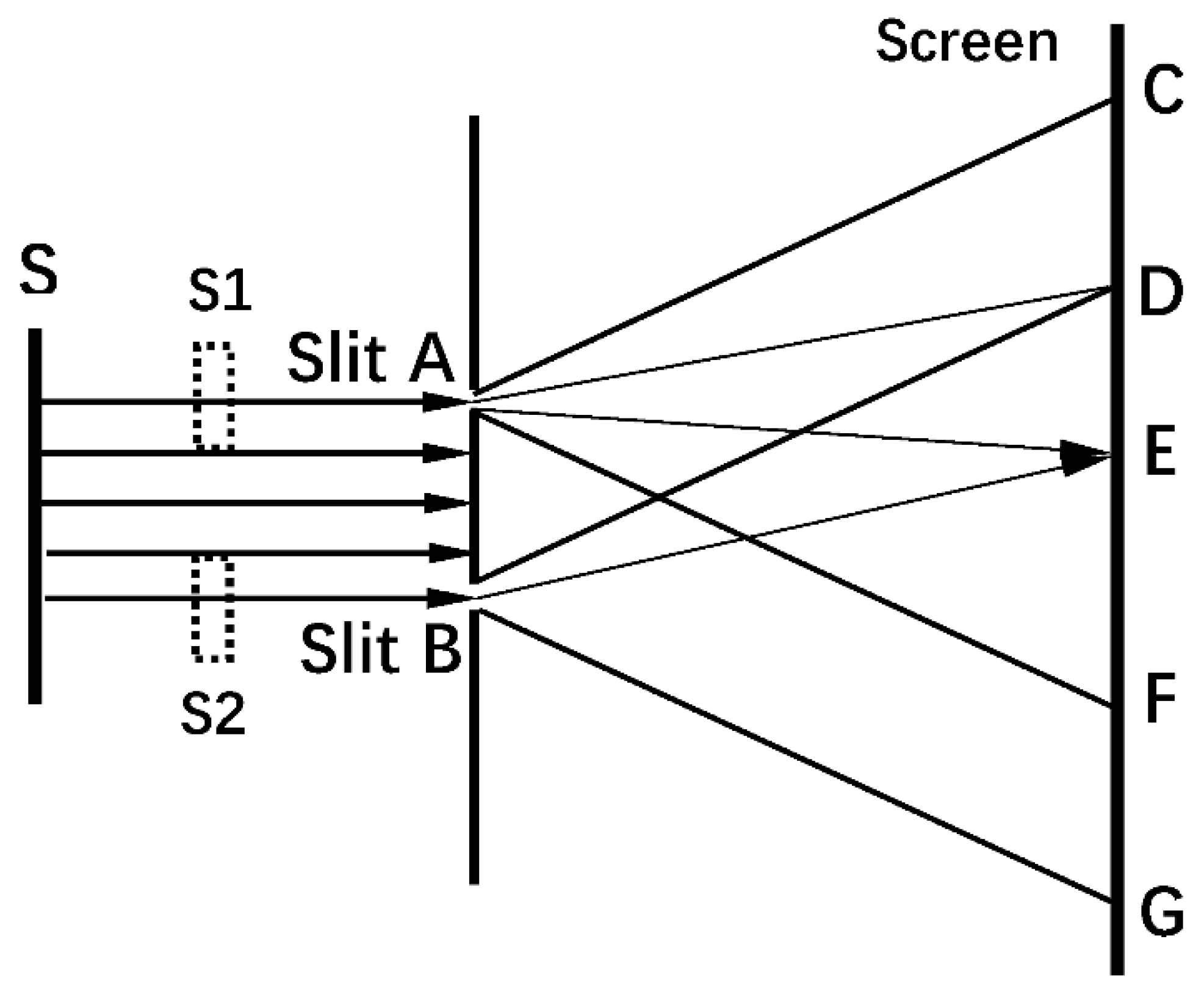

Figure 1 illustrates the interference of two particle beams of this kind of interference mechanism. In every point on the screen in

Figure 1, say, point E, the wave vectors of the paarticles coming from the slits A and B are different, while their de Broglie wavelengths are equal.

The construction of the wave function (27) actually does not require that two particle waves come from the same particle source. They can come from different particle sources. In

Figure 1, we draw two small dotted rectangles that represent two imagined particle sources, S1 and S2, independent of each other. The particles passing through the two slits A and B can respectively come from these two sources with the same de Broglie wavelength. When the single source S is replaced by the sources S1 and S2, the interference pattern in the screen will remain unchanged.

-

C.

Two identical particles with exchange effect

If the de Broglie wavelengths of the two beams of particles are not equal, the wave function (27) does not satisfy equation (21). Oppenheimer [

22] first noted that the wave function of two identical particles should be written in the form of symmetry or antisymmetry with respect to particle exchange. Their wave functions are constructed as follows:

In this wave function, the first (second) term is called direct (exchange) term, and the upper (lower) sign stands for Bosons (Fermions). Substituting (30) into (21), we get the energy of this wave function to be the summation of the two individual particles.

By Eqs. (30) and (8), we have the particle density:

Particle density varies with spatial coordinates but not over time. This results in a stable interference pattern. The phase difference at every space point is . If (30) is substituted into (17), there is the same phase difference in the expression of the current density. The particle density varies periodically in space, the minimum value being 0.

Note that the wave vectors of the two interference waves are not the same. Therefore, they come from different particle sources. See [

21] for such experiments.

In the wave function (30), the phase differenc between the direct and exchange terms is

This is just the phase difference in Eq. (32). It is not the direct interference between the two particle beams as the case of (27). In stead, when they encounter, they first mix to a wave function containing an exchange term, and then, interference occurs between the direct and exchange terms. This is called exchange effect interference mechanism.

Compared with the conditions of classical wave interference, it is seen that in this case even the condition of equal wavelength can be discarded. The reason is that the exchange term provides the required term participating the interference.

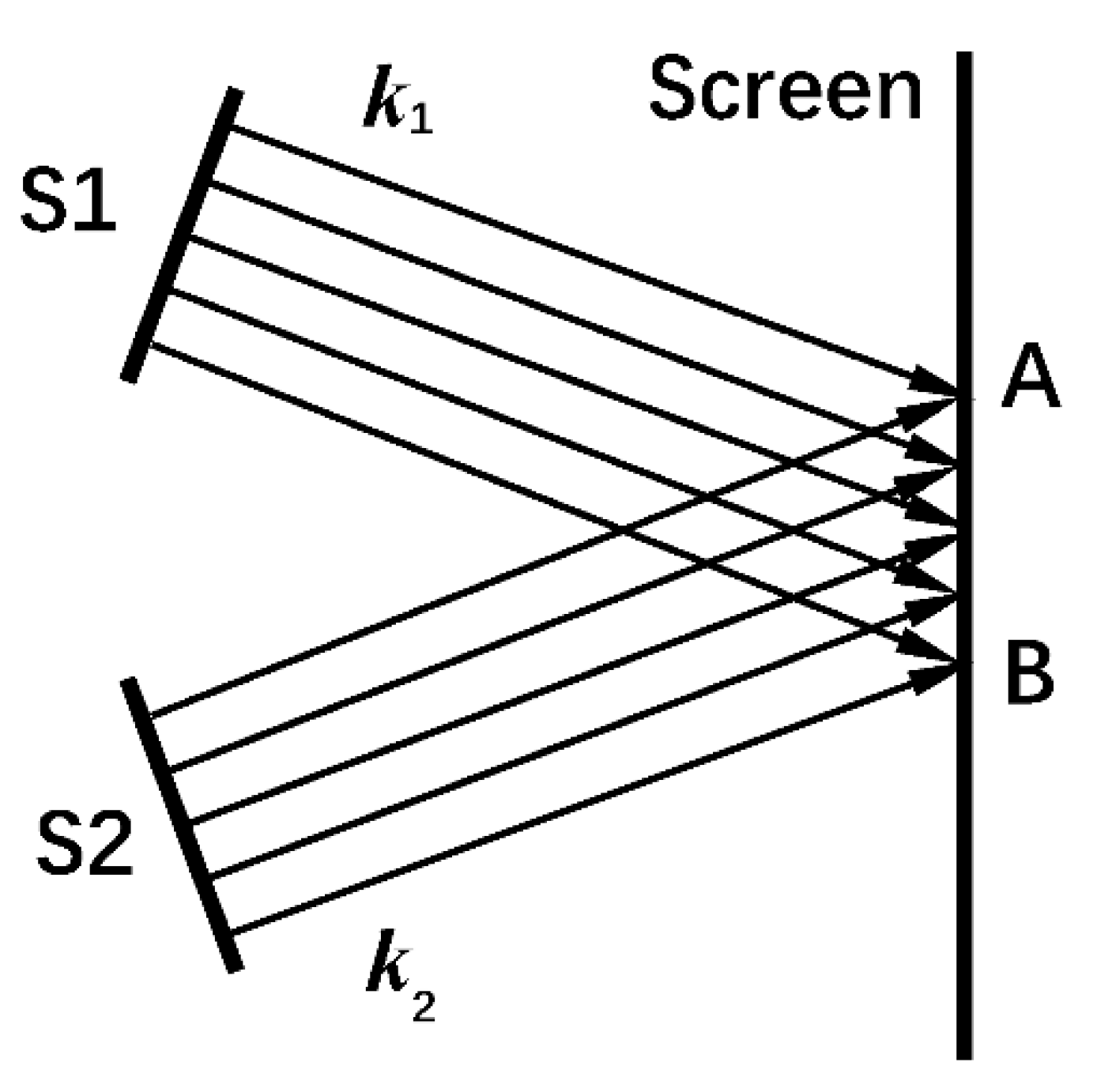

We illustrate this kind of interference in

Figure 2. The particles come from two sources independent of each other. At every point on the screen, the wave vectors of particles from the two sources are always fixed. Although the interference mechanism of the experiment in [

21] is the same as

Figure 2, the setup in

Figure 2 is much simpler. We suggest doing the experiment shown by

Figure 2. This experiment is quite similar to double-slit interference.

Equation (33) applies in one-, two-, and three-dimensional spaces. In the following, we take electrons as an example.

We inspect the spatial periodicity of the interference pattern. Equation (33) helps us to make a numerical estimate. Assuming that the electron is accelerated by a voltage V to obtain the kinetic energy eV, its wave vector is . If two electron beams move in the same direction and are subjected to voltages of 10 V and 9.5 V, respectively, then the interfering period is . The smaller the absolute value of the wave-vector difference, the greater the space period. In this view, the interference period is artificially adjustable.

Table 1 lists the three interference mechanisms and corresponding expressions of spatial phase difference.

When there are two identical particles with respective wave vectors and , the wave function (30) has only one direct term and one exchange term, and these two terms interfere, as shown by Eq. (32). For identical particles with more wave vectors, there are more exchange terms in the multiparticle wave function. Thus, in the expression of particle density, there will be more interference terms. For example, we consider the case of three wave vectors , , and . The three-particle wave function contains one direct term and five exchange terms. The energy is . There are three wave vector difference, , , and , so that the expression of the particle density contains three interference terms, and the interference patter is the superposition of those of three interference periods. In general, if there are N wave vectors, , in a beam of identical particles, the N-particle wave function contains terms, where one is the direct term and all others are exchange terms. The number of wave vector difference, , is . The particle density contains interference terms and the interference pattern is the superposition of interference periods.

For the case of two wave interference, the two independent sources can be arbitrarily placed. They can be linear sources or planar sources. It follows that interference can be formed in one-, two, and three-dimensional space.

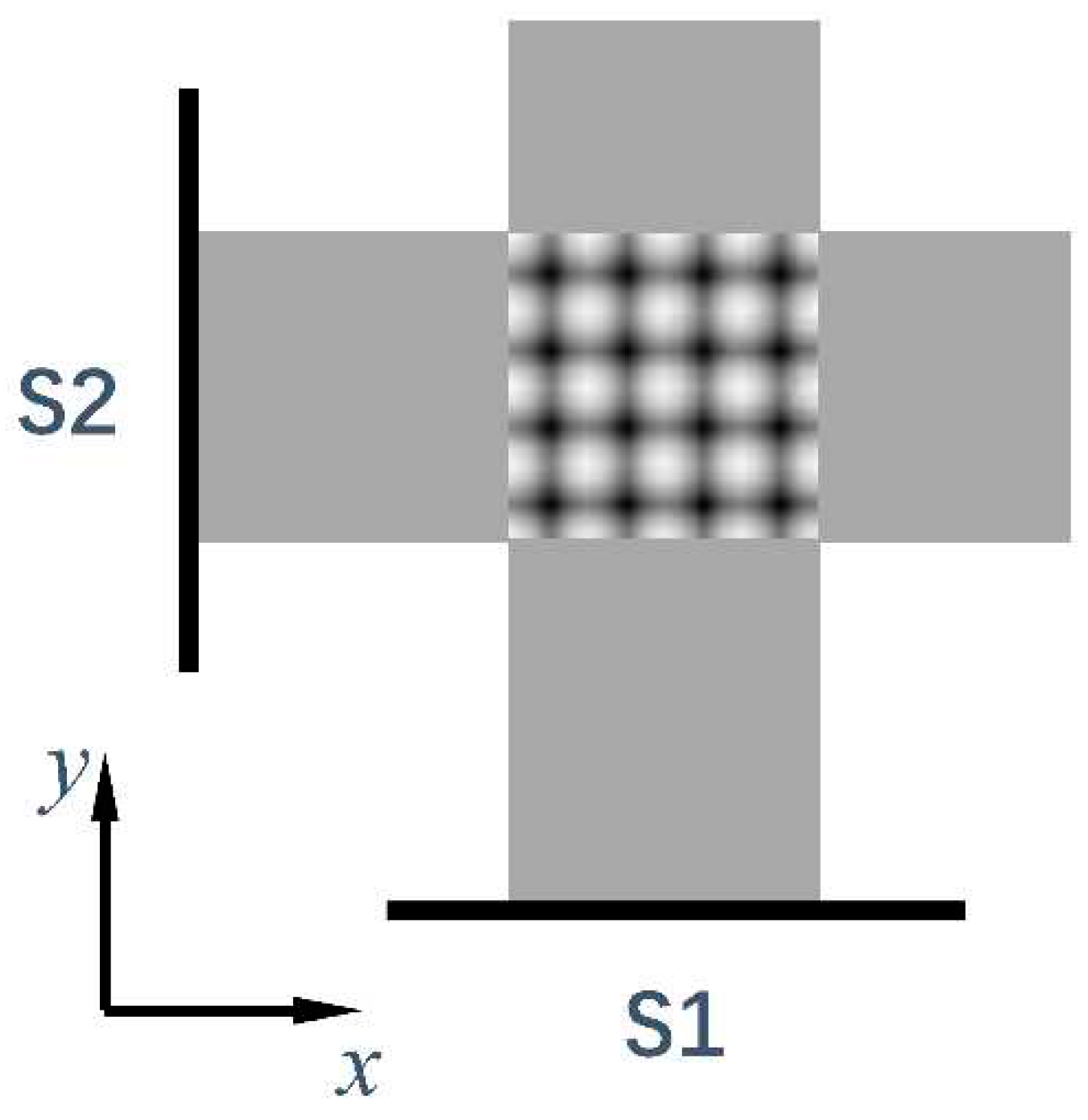

In

Figure 2, the two electron berms form one-dimensional interference pattern on the screen. If the two sources are placed in the way of

Figure 3, such that the two wave vectors

and

of the emitted electron beams are respectively along the

x and

y directions, the interference pattern is formed in two-dimensional space. If the sources in

Figure 3 have widths along the

z directions, i.e., planar sources, and

and

have

z components, then, the interference pattern can be formed in three-dimensional space.

In

Figure 3, an interference maximum, a black ball, can be regarded as a “density particle”. The interference pattern can be regarded as a “density crystal” formed by the periodic arrangement of density particles. Note that such a density crystal is suspended in the air.

Suppose that the two electron current densities emitted by the sources are the same. From Eq. (32), we know that each density particle contains twice the physical quantity of an electron, such as the mass m and charge e. Therefore, the electrons behave as being paired.

-

D.

A special case

In

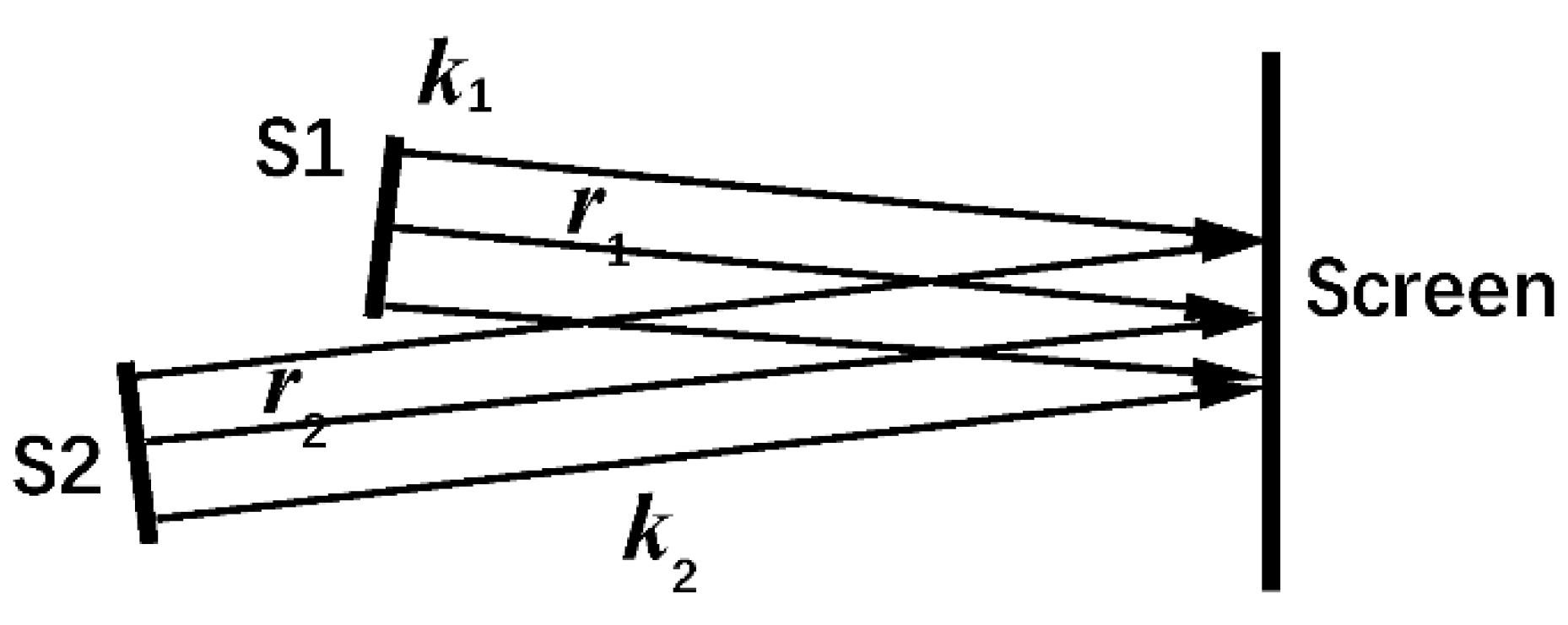

Figure 2, the two beams of electrons can have equal de Broglie wavelength, although their wave vectors are not he same. In that case, the two electron beams also meet equal wavelength interference mechanism besides the exchange effect interference mechanism. Then, which mechanism do the two electron waves interfere by on earth? In other words, is the total wave function in the interference region Eq. (27) or (30)? It is not easy to give an answer.

We suggest an experiment to make a distinction. Let the two sources emit electrons with equal de Broglie wavelength,

. The two sources are placed such that the two emitted beams are almost parallel, i.e.,

, see

Figure 4. Then,

This phase difference is nearly zero. Hence, for exchange effect interference mechanism, the interference fringes are hardly to see. While for equal wavelength interference mechanism, the fixed phase difference is

This phase difference depends on the position vector difference .

Let the electron source S2 in

Figure 4 be arranged such that it can move in the direction of the

. Then, when S2 moves,

varies while

does not. The phase difference (34) is always about zero, while the phase difference (35) varies with the

. Therefore, when S2 moves, if the pattern on the screen does not change, it is an exchange effect interference mechanism, while if the pattern changes, it is the equal wavelength interference mechanism.