Submitted:

09 October 2023

Posted:

11 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diet composition and feeding

2.2. Live Weight and Daily Weight Gain

2.3. Feed Conversion ratio and Income Over Feed Cost

2.4. Water footprint estimation

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alcamo, J.; Döll, P.; Henrichs, T.; Kaspar, F.; Lehner, B.; Rösch, T.; Siebert, S. Development and testing of the WaterGAP 2 global model of water use and availability. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2003, 48, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosegrant, M.W.; Ringler, C.; Zhu, T. Water for agriculture: maintaining food security under growing scarcity. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 2009, 34, 205–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosegrant, M.W.; Cai, X.; Cline, S.A. . Global water outlook to 2025. Averting an Impending Crisis. International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington. D.C. USA, 2002; pp. 12–24. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6289055.pdf. (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Hoekstra, A.Y. Virtual water: An introduction. In Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade. Delft, The Netherlands. 12 and 13 December 2002; Hoekstra, A.Y. Ed. UNESCO-IHE: Delft, The Netherlands, 2003 www.waterfootprint.org/Reports/Report12.pdf. (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Chapagain, A.K.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Virtual Water Flows Between Nations in Relation to Trade in Livestock and Livestock Products. Value of Water Research Report. UNESCO-IHE. Delft, The Netherlands, 2003. pp. 11–30. https://www.waterfootprint.org/resources/Report13.pdf. (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems, 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Neale, C.M.U; Ray, C.; Erickson, G.E.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Water producivity in meat an milk production in the US from 1960 to 2016. Environ. Int., 2019, 132, 105084. [CrossRef]

- Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. Livestock: on our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Glob. Food Sec., 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fraiture. C.; Wichelns, D.; Rockström, J.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Eriyagama, N.; Gordon, L.J.; Hanjra, M.A.; Hoogeveen, J.; Huber-Lee, A.; Karlberg, L. Looking ahead to 2050: scenarios of alternative investment approaches. In Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of of Water Management in Agriculture; Molden D., Ed.; International Water Management Institute: Colombo; London, UK, 2007; pp. 91–145.

- Gerbens-Leenes, P.W.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The water footprint of poultry, pork and beef: A comparative study in different countries and production systems. Water Resour. Ind., 2013, 1–2, 25–36. [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, G.; Sanguansri, P.; Nolan, M.; Marks, N. Meat consumption and water scarcity: beware of generalizations, J. Clean. Prod., 2012, 28, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adduci, F.; Labella, C.; Musto, M.; D’Adamo, C.; Freschi, P.; Cosentino, C. Use of Technical and Economical Parameters for Evaluating Dairy Cow Ration Efficiency. Ital. J. Agron. 2015, 10, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campiotti, M. Sistemi pratici per fare più reddito in stalla. Informatore agrario, 2005, 3, 27–33.

- Cosentino, C.; Adduci, F.; Musto, M.; Paolino, R.; Freschi, P.; Pecora, G.; D’Adamo, C.; Valentini, V. Low vs high "water footprint assessment" diet in milk production: A comparison between triticale and corn silage based diets. Emir. J. Food Agric., 2015, 27(3): 312-317.

- Zhang, H.; Zhuo, L.; Xie, D.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Wu, A.; Wu, P. Water footprints and efficiencies of ruminant animals and products in China over 2008–2017. J. Clean. Prod., 2022, 379, 134624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarricone, S.; Colonna, M.A.; Giannico, F.; Facciolongo, A.M.; Caputi Jambrenghi, A.; Ragni, M. Effects of dietary extruded linseed (Linum usitatissumum L.) on performance and meat quality in Podolian young bulls. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci., 2019, 49, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzas, C.; Sniffen, C.J.; Seo, S.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fox, D.G. A revised CNCPS feed carbohydrate fractionation scheme for formulating rations for ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol., 2007, 136, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Schönleben, M.; Mentschel, J.; Göres, N.; Fissore, P.; Cohrs, I.; Sauerwein, H.M.; Ghaffari, H. Growth performance and economic impact of Simmental fattening bulls fed dry or corn silage-based total mixed rations, Animals, 2023. 17(4): 100762. [CrossRef]

- Schingoethe, D.J. A 100-Year Review: Total mixed ration feeding of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci., 2017, 100, 10143–10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, F.; Agabriel, J.; Micol, D. Alimentation des bovines in en croissance et à l’engrais. In Alimentation des bovins, ovins et caprins. Besoins des animaux- Valeurs des aliments. Table INRA; Editions Quae, Paris, France, 2010, pp. 91–122. Available online: http://www.civamad53.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Tables-INRA.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Fox, D.G.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Guiroy, P.J. 2001. Determining feed intake and feed efficiency of individual cattle fed in groups. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253681583 (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Bailey, K.; Beck, T.; Cowan, E.; Ishler, V. (2009). Dairy Risk–Management Education: Managing Income Over Feed Costs. Agricultural Communications and Marketing, The Pennsylvania State University, PA, USA.

- Chapagain, A.K.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Water footprints of nations. Volume 1: Main report; UNESCO-IHE, Delft, The Netherlands, 2004, p. 25. www.waterfootprint.org/Reports/Report16Vol1.pdf. (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Mekonnen, M.M. Global Water Scarcity: Monthly Blue Water Footprint Compared to Blue Water Availability for the World’s Major River Basins. Value of Water Research Report Series No.53. UNESCO-IHE: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 12–24.

- Palhares, J.C.P.; Morelli, M.; Novelli, T.I. Water footprint of a tropical beef cattle production system: The impact of individual-animal and feed management. Adv. Water Resour., 2021, 149, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eady, S.; Viner, J.; MacDonnell, J. On-farm greenhouse gas emissions and water use: Case studies in the Queensland beef industry. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2011, 51, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, R.; Jaafar, H.H.; Daghir, N. New estimates of water footprint for animal products in fifteen countries of the Middle East and North Africa (2010–2016). Water Resour. Ind., 2019, 22, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maré, F.A.; Jordaan, H.; Mekonnen, M.M. The Water Footprint of Primary Cow– Calf Production: a revised bottom-up approach applied on different breeds of beef cattle. Water, 2020, 12, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.M. Land and Water Usage in Beef Production Systems. Animals, 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | CSF | TSF |

|---|---|---|

| Diet composition, % | ||

| Corn Silage | 41.1 | - |

| Triticale Silage | - | 45.9 |

| Corn Meal | 13.7 | 13.7 |

| Wheat Straw | 13.7 | 6.9 |

| Barley Meal | 1.4 | 5.5 |

| Corn Gluten Meal | - | 3.8 |

| Sunflower Meal | - | 6.9 |

| Soybean Meal Extraction | 10.27 | - |

| Beet Pressed Pulp | 3.4 | 5.5 |

| Corn Distillers | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| Hydrogenated Fat | 1.0 | - |

| Vitamin Mineral Supplement | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| NaHCO3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| NaCl | 0.7 | 1.03 |

| Water Mixing | 8.9 | 6.8 |

| DM | 58.4 | 58.3 |

| Feed cost | ||

| €/kg DM | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Chemical composition, g/kg DM a | ||

| CP | 147.4 | 147.0 |

| CF | 166.4 | 167.6 |

| NDF | 367.5 | 390.7 |

| ADF | 212.3 | 239.7 |

| ADL | 42.7 | 46.3 |

| EE | 43.0 | 27.1 |

| Ash | 78.9 | 87.9 |

| Starch | 248.8 | 249.7 |

| Nutritive value, kg/DM | ||

| UFV b | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| PDIN c | 96.5 | 106.0 |

| PDIE d | 105.1 | 111.8 |

| PDIA e | 51.5 | 59.5 |

| Trial day | CSF | TSF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | SE | DM | SE | |

| 0 | 6.56 | 0.039 | 6.41 | 0.033 |

| 14 | 6.80 | 0.041 | 6.64 | 0.035 |

| 28 | 7.03 | 0.043 | 6.86 | 0.036 |

| 42 | 7.26 | 0.044 | 7.09 | 0.037 |

| 56 | 7.49 | 0.046 | 7.31 | 0.039 |

| 70 | 7.71 | 0.048 | 7.52 | 0.04 |

| 84 | 7.93 | 0.049 | 7.73 | 0.042 |

| 98 | 8.14 | 0.051 | 7.94 | 0.043 |

| 112 | 8.35 | 0.052 | 8.15 | 0.044 |

| 126 | 8.55 | 0.054 | 8.34 | 0.045 |

| 140 | 8.75 | 0.055 | 8.54 | 0.046 |

| 154 | 8.95 | 0.057 | 8.73 | 0.048 |

| 168 | 9.13 | 0.058 | 8.91 | 0.049 |

| 182 | 9.32 | 0.059 | 9.09 | 0.05 |

| All | 8.00 | 0.05 | 7.80 | 0.04 |

| Trial day | LW, kg | ADG, kg/day | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | SE | TSF | SE | CSF | SE | TSF | SE | |

| 1 | 347.43 | 0.741 | 341.30 | 0.636 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 1.39 | 0.003 |

| 14 | 367.32 | 0.783 | 360.84 | 0.673 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 1.40 | 0.003 |

| 28 | 387.26 | 0.826 | 380.43 | 0.709 | 1.43 | 0.003 | 1.40 | 0.003 |

| 42 | 407.19 | 0.868 | 400.01 | 0.746 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 1.40 | 0.003 |

| 56 | 427.07 | 0.911 | 419.53 | 0.782 | 1.42 | 0.003 | 1.39 | 0.003 |

| 70 | 446.84 | 0.953 | 438.95 | 0.818 | 1.41 | 0.003 | 1.38 | 0.003 |

| 84 | 466.45 | 0.994 | 458.23 | 0.854 | 1.40 | 0.003 | 1.37 | 0.003 |

| 98 | 485.88 | 1.036 | 477.31 | 0.89 | 1.38 | 0.003 | 1.36 | 0.003 |

| 112 | 505.07 | 1.077 | 496.16 | 0.925 | 1.36 | 0.003 | 1.34 | 0.002 |

| 126 | 524.00 | 1.117 | 514.75 | 0.959 | 1.34 | 0.003 | 1.32 | 0.002 |

| 140 | 542.62 | 1.157 | 533.05 | 0.993 | 1.32 | 0.003 | 1.30 | 0.002 |

| 154 | 560.92 | 1.196 | 551.02 | 1.027 | 1.30 | 0.003 | 1.27 | 0.002 |

| 168 | 578.86 | 1.234 | 568.65 | 1.06 | 1.27 | 0.003 | 1.25 | 0.002 |

| 182 | 596.43 | 1.272 | 585.91 | 1.092 | 1.24 | 0.003 | 1.22 | 0.002 |

| All | - | - | - | - | 1.365 | 0.003 | 1.341 | 0.002 |

| Trial day | FCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | SE | TSF | SE | |

| 0 | 4.629 | 0.08 | 4.603 | 0.09 |

| 14 | 4.777 | 0.05 | 4.748 | 0.03 |

| 28 | 4.935 | 0.09 | 4.904 | 0.02 |

| 42 | 5.104 | 0.11 | 5.072 | 0.12 |

| 56 | 5.285 | 0.07 | 5.251 | 0.06 |

| 70 | 5.477 | 0.06 | 5.442 | 0.05 |

| 84 | 5.682 | 0.07 | 5.645 | 0.05 |

| 98 | 5.900 | 0.07 | 5.860 | 0.04 |

| 112 | 6.131 | 0.06 | 6.089 | 0.09 |

| 126 | 6.376 | 0.09 | 6.332 | 0.03 |

| 140 | 6.635 | 0.05 | 6.589 | 0.09 |

| 154 | 6.91 | 0.07 | 6.861 | 0.07 |

| 168 | 7.200 | 0.08 | 7.149 | 0.05 |

| 182 | 7.507 | 0.07 | 7.454 | 0.09 |

| All | 5.896 | 0.05 | 5.857 | 0.09 |

| Trial day | IOFC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF | SE | TSF | SE | |

| 0 | 2.215 | 0.25 | 2.173 | 0.13 |

| 14 | 2.114 | 0.13 | 2.111 | 0.11 |

| 28 | 2.052 | 0.09 | 2.019 | 0.15 |

| 42 | 1.921 | 0.15 | 1.922 | 0.09 |

| 56 | 1.824 | 0.08 | 1.795 | 0.13 |

| 70 | 1.697 | 0.10 | 1.672 | 0.20 |

| 84 | 1.569 | 0.11 | 1.548 | 0.12 |

| 98 | 1.411 | 0.11 | 1.425 | 0.10 |

| 112 | 1.253 | 0.09 | 1.267 | 0.14 |

| 126 | 1.099 | 0.10 | 1.117 | 0.08 |

| 140 | 0.945 | 0.12 | 0.963 | 0.16 |

| 154 | 0.791 | 0.14 | 0.778 | 0.08 |

| 168 | 0.610 | 1.13 | 0.633 | 0.11 |

| 182 | 0.426 | 1.11 | 0.452 | 0.13 |

| All | 1.418 | 0.90 | 1.418 | 0.11 |

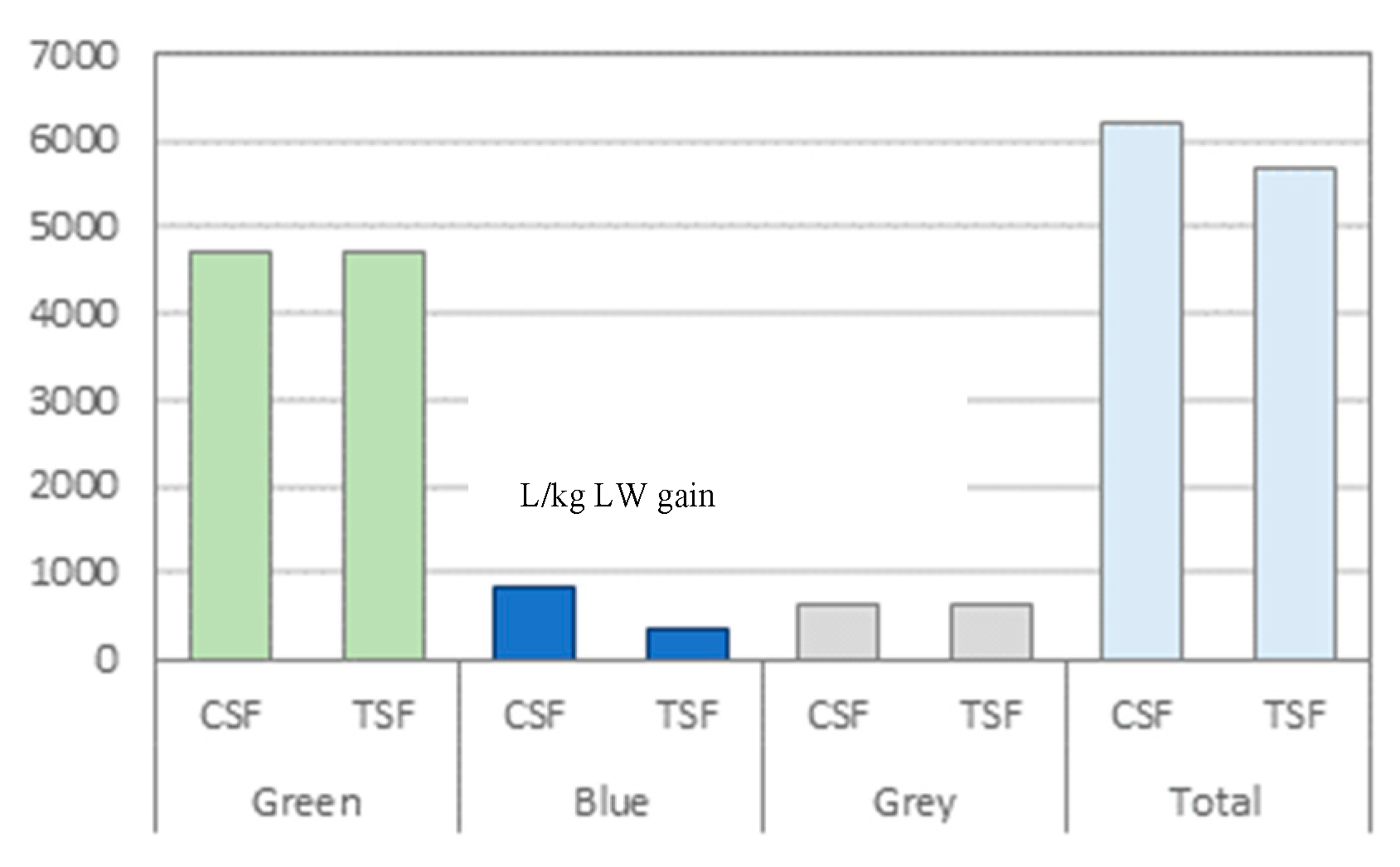

| Groups 1 | Indirect water footprint | Direct water footprint | WF Average L/day/animal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFFeed | WFFeed Mixing | WFDrinking | WFService | ||

| Estimated | Observed | ||||

| CSF | 8471 | 1.439 | 23.99 | 75 | 8571 |

| TSF | 7626 | 1.756 | 23.41 | 75 | 7726 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).