1. Introduction

Coral reef ecosystems are undergoing widespread degradation, eroding the ecological roles of key predators and leaving few detailed behavioural datasets to serve as baselines for future comparison. Yet the behaviour and movement patterns of elasmobranchs remain poorly understood due to the challenges of studying highly-mobile marine species (Speed et al., 2010; Castro, 2017; Papastamatiou et al., 2022a). Movement is a fundamental aspect of their behaviour, influencing ecological roles and population dynamics (Papastamatiou et al., 2012; Gallagher et al., 2021). Elasmobranch movements reflect a complex interplay of biotic and abiotic factors governing access to food, mates, and refuge (Speed et al., 2010; Papastamatiou and Lowe, 2012). As mesopredators, reef sharks exert consistent predatory pressure, regulating smaller fish and invertebrate populations, fostering biodiversity and resilience in reef ecosystems (Okey et al., 2004; Bascomte et al., 2005; Freire et al., 2008; Papastamatiou et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2013, 2016; Frisch et al., 2016). Understanding their spatial ecology and behaviour patterns thus provides critical insights into the intricate relationships sustaining coral reefs (Mourier et al., 2013, 2016; Chin et al., 2016; Papastamatiou et al., 2019). The blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) is an ideal species for ethological investigation with its preference for shallow coastal habitats (Papastamatiou et al., 2009; Mourier et al., 2012, 2013; Chin et al., 2013, 2016).

Most recent advances in shark spatial ecology have come from telemetry, acoustic tagging, and other remote monitoring technologies, which have provided important insights into patterns of movement, habitat use, site fidelity, and connectivity (Voegeli, et al., 2001; Papastamatiou et al., 2010; Block et al., 2011; Hammerschlag et al., 2011; Mourier et al., 2012; Renshaw et al., 2024). However, these technologies offer only a snapshot view of the lives of the subjects, fragmented in time and detached from context. They track position but not purpose. They cannot reveal the behavioural motivations, social dynamics, or emotional states driving the movements they record (Whitney et al., 2012; Mourier et. al., 2019; Renshaw et al., 2024). Tags attached to the dorsal fin can affect its structure and hydrodynamics, impacting the results of the given study (Hicks et al., 2024). Many studies of blacktip reef sharks rely on surgically implanted acoustic transmitters (e.g. Meyer, et al., 2008; Mourier and Planes, 2013; Mourier et al. 2016; Bouyoucos et al., 2020), which requires capture, and insertion of the device into the peritoneal cavity. This can introduce stress, risk of infection, haemorrhaging, and behavioural disturbance. The numbers of sharks included in such studies are necessarily limited (e.g. Voegeli et al., 2001), resulting in sampling of only a small subset of a given shark community.

In contrast, long-term, direct underwater observation of individually-identified sharks, an established ethological approach, imposes no such limitations. It allows the observation of undisturbed animals and yields behavioural and contextual information that is unattainable through telemetry. Field observation of non-handled and unstressed animals provides a complementary behavioural framework within which telemetry results can be properly interpreted (Mourier et al., 2019; Renshaw et al., 2024), ensuring that quantitative approaches remain anchored in the realities of the animals’ actual behaviour (Altmann, 1974; Greene 2005; Bateson and Laland, 2013; Bateson and Martin, 2021). Therefore, over a period of 6.5 years, underwater observation was used to document aspects of the behaviour of a blacktip community in a fringing lagoon on the north shore of Mo’orea Island, French Polynesia.

The ethological tradition emphasizes the necessity of detailed descriptions of the actions and interactions of animals in their natural environment as a foundation for quantitative study (Tinbergen, 1951, 1963; Lorenz 1973; Lehner, 1996; Greene, 2005; Alcock, 2013; Bateson and Laland, 2013). In the case of sharks, studying behaviour through direct underwater observation was considered by some to be impossible (Randall and Helfman 1973; Gruber and Myrberg 1977; Castro 2017), resulting in the predominant use of remote sensing devices in shark studies. However, a descriptive foundation is particularly crucial for these marine predators, whose natural behaviours remain poorly documented compared with other vertebrates (Jacoby et al., 2012; Mourier et al., 2019). The rare opportunity to engage in such direct study was therefore seized.

A central element of ethological research is the ability to recognize individual animals by their appearance. The use of natural markings for non-invasive monitoring of individuals of the given species enables repeated observations across time, which alone reveals the degree and nature of individual variation. This technique has a rich tradition in ethology. Landmark studies, such as Jane Goodall’s work on chimpanzees using facial and body scars, have emphasised individual identification to recognize personalities, and thus document social hierarchy, patterns of association, kin relationships, and individual behavioural traits (Goodall, 1968). Cynthia Moss’s elephant research, employing ear vein patterns, revealed much about matriarchal bonds (Moss, 1988), and Scott Kraus’s right whale studies with callosity patterns permitted the assessment of population dynamics (Kraus et al., 1986). Photographic identification of whisker spots in Serengeti lions illuminated coalition strategies (Schaller, 1972) and fluke patterns in humpback whales revealed much about cultural song transmission and evolution (Payne and Payne, 1985). These and other studies have demonstrated the power of observing animals as individuals of a given species for the decoding of complex behaviours.

This approach has also been successfully applied in several shark species. For example, social communities in blacktip reef sharks in Mo’orea were studied through photo-identification of individuals (e.g. Porcher 2005, 2023a; Mourier et al., 2012, Lionnet et al., 2025). Whale sharks have been studied at Ningaloo Reef using natural spot patterns to track individuals across years (Holmberg et al., 2009), and long-term projects in the Red Sea have employed photo-identification of dorsal fins and pigmentation patterns to monitor reef-associated sharks (Marshall and Pierce, 2012). Such methods allow researchers to link movements with spatial ecology, providing insights into site fidelity, social associations, and individual behavioural variation and consistency.

The present study was conducted between 1999 and 2005, prior to the blacktip community’s decimation and eventual loss due to the intensive shark finning that resulted in the country being declared a shark sanctuary in 2006 (Porcher 2010; Séguigne et al., 2023a). While subsequent research in Mo’orea has provided insights into the social associations and residency of C. melanopterus (e.g. Mourier et al., 2012, 2013)), these studies were conducted on a reconstituted population, composed largely of the younger, similarly-aged individuals, that had been protected in the lagoons during the slaughter and were able to recolonize the island after the establishment of the sanctuary. In contrast, the present work documents the behaviour and movements of an intact, naturally-structured blacktip community that had been shaped over evolutionary time scales. As such, it provides an irreplaceable baseline for understanding the social and spatial ecology of blacktip reef sharks in French Polynesia. It also serves for comparison with current studies, there and in other locations where widespread degradation has occurred, to aid in the understanding of how spatial ecology might change in response to extensive damage, including declines in reef shark numbers exceeding 95 % (MacNeil et al., 2020).

Conservation of reef sharks is vital in the face of the shark fin trade and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing (Gallagher et al., 2021; Porcher and Darvell, 2022; Worm et al., 2024). Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a cornerstone of shark conservation, yet their efficacy hinges on movement data, since many reef sharks range beyond protected boundaries, with patterns varying seasonally and across habitats (Papastamatiou et al., 2009, 2010; White et al., 2017; Pike et al., 2024). The blacktip reef shark is listed on Appendix II of CITES; its status is “vulnerable.” Its slow growth, low reproductive rate, and reliance on coastal habitats for mating, pupping, and juvenile development, heighten its vulnerability, not only to fisheries, but to pollution and habitat degradation (Porcher, 2005; Chin et al., 2013; Porcher and Darvell, 2022). It ranges the Indian and tropical Pacific Oceans wherein fisheries management is virtually absent (Porcher and Darvell 2022), emphasizing its need for protection.

Building on a prior ethogram that catalogued 35 behaviours to establish a behavioural foundation (Porcher, 2023a), this study describes details of the movement patterns of this reef-associated predator, contributing to the evidence base informing coral reef conservation strategies.

3. Results

Blacktip reef sharks were the predominant elasmobranch observed in the study area, though other species, including whitetip reef sharks (Triaenodon obesus), nurse sharks (Nebrius concolor), pink whiprays (Himantura fai), and eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari), were also present. Sporadic sightings of sicklefin lemon sharks (Negaprion acutidens) and grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) were recorded.

The initial feeding sessions in Section A primarily attracted mature female blacktip reef sharks whose core ranges included the observation site. Two or three male individuals occasionally joined the females, as did juveniles exceeding an estimated 70 cm in standard length.

After approximately three months, the resident individuals had been identified and were recognizable. These resident sharks began arriving at the beginning of the feeding sessions and dispersed roughly 30 minutes later. Following their departure, new individuals appeared, many of which were transients.

The feeding sessions resulted in an aggregation of reef blacktips that facilitated social interactions (Porcher, 2023a; Klimley

et al., 2023). Many of these occurred beyond visual range, down-current from the food source, but by drifting down-current, the observer could document them directly. Social engagement occasionally took precedence over feeding, for at times, fish scraps remained untouched on the substrate while the gathering of sharks interacted. Indeed, several individuals, residents of nearby regions, were regularly observed arriving late at the sessions, and, instead of seeking food, joining the others in social exchanges (which indicates that the slight provisioning was not a dominant factor in their presence).

Figure 2 shows identified blacktip attendance at the sessions held at Sites A and B from 99-04-11 to 05-09-29.

Observations totalled 506 hours across 501 sessions, with 67 % of observation time (338 hours) during low-light sunset conditions, a key period for activity (Papastamatiou et al. 2009). The sessions recorded 11,514 individual sightings. A total of 475 reliably-distinguishable individual sharks were identified, culled from 581 initial records.

3.1. The Community

Female C. melanopterus exhibited pronounced site fidelity to core home ranges. The lagoon’s natural features significantly influenced their spatial dynamics, with a marked preference for the outer third of the lagoon along the barrier reef, where the coral habitat was healthiest.

Table 1 presents the counts of adult blacktip reef sharks identified at each observation site, detailing the numbers of residents, the average Residency Index, periodic transients, rare transients, and individuals observed either once or during a single brief period.

The limited number of sessions conducted at Site E and Papetoai made it impossible to determine the transients in those areas. As the majority of observation sessions were in Section A, most adult blacktips ranging across the western half of the lagoon were first observed and catalogued there, and are listed in

Table 1 under ‘Site A,’ with the exception of those whose ranges were later located elsewhere. After 2004-06-20, no unidentified blacktips were encountered in the lagoon other than gravid females passing through during the season of parturition. This suggests, with some confidence, that virtually all surviving adult residents had been identified. Thus, over those 40 sessions, the binomial 95 % confidence interval (CI) is estimated at (1 – 3/40, 1) (0.925, 1). However, these were not snapshot observations (

i.e. single events) but over a period of about an hour each time on average. During the course of such a period sharks would be entering and leaving visual range repeatedly. Thus, during such an observation period a shark would appear, and it would be identified. After circling out of sight it may return sooner or later, whereupon it would be identified but of course would not be counted any further. But each such shark appearance is an ‘event’, and there are clearly many during such a period. Say, conservatively, that ‘a shark’ was seen in this way 120 times in that period (

i.e., 2/min) – it was often at a higher rate. It cannot be ruled out that any of those observations could be of a new shark, but each one was checked, and none was found. Accordingly, the estimated 95 % CI becomes (1 3/(40 120), 1) (0.999375, 1).

Sharks with home ranges west of the study site were apparently not only aware of the auditory cues of the approaching kayak but were also positioned to detect and follow the westward-flowing scent trail to the feeding sessions. Conversely, individuals with core ranges up-current (east) of the site were less likely to encounter these cues and scored lower Residency Indexes. However, those in the vicinity—generally within Section A (

Figure 1)—likely became aware of the aggregation of sharks via hearing and the lateral line sense, so in time this difference diminished.

Certain individuals, both adults and juveniles, scored a Residency Index exceeding 0.5 over a period of many months. Upon their disappearance, it was not possible to determine whether they had died or departed. In one instance, the carcass of the individual was found, whereas in all other cases, the reason for their temporary presence and subsequent absence remained unknown.

Some individuals—predominantly males—appeared at intervals of some months, suggesting a circuitous movement pattern, though their core ranges remained unidentified.

One juvenile female, designated #109, attended sessions exclusively between December and April for over three consecutive years, then disappeared in 2004, in her first year of maturity, amid intensive shark finning activities. During her seasonal presence, she maintained a Residency Index above 0.6, yet she was not a year-round resident. Her unique and unusual case highlights the behavioural variability in the species (Porcher, 2022).

Juvenile blacktip reef sharks identified during the study are detailed in

Table 2, categorized as residents, periodic transients, or individuals observed either once or for a single period. No rare transients were identified among juveniles. Sharks initially observed as juveniles, including young-of-the-year, matured over the course of the study, with each assigned to a category based on its status when first identified.

For statistical analyses of the Residency Indexes see the Supplementary Material.

The interpretation of residency requires some care. Suppose the observation site was in the overlap between two ranges, closer to the centre of one than the other. The frequency of observation would be greater for the one, yet both sharks would in fact be fully resident in their core ranges. If now each such range had several occupants, the Residency Index would be in part a measure of relative location of the observation site to the barycentre of each. Of course, ranges vary in size and shape depending on the habitat, while sharks roam widely in as yet unknown ways. Individual variation in terms of distances travelled and roaming tendencies result in transient observations at different frequencies.

Figure 3 illustrates a hypothetical location for a random observation site relative to two individual blacktip shark ranges. Although the two ranges include the site, the residency indexes would differ.

The Nurseries and Juveniles

A prominent blacktip reef shark nursery was located along the curvature of the barrier reef adjacent to Cook’s Bay (Section E), where an annual influx of 100–200 neonates was consistently documented. In contrast, smaller nurseries at the western extremity of the reef and the eastern end of the Papetoai lagoon hosted the offspring of only one or two females.

Approximately 6 weeks to 2 months post-parturition, neonates began dispersing along the reef in small groups. They exhibited heightened vigilance, repeatedly circling outward and regrouping, always poised to retreat to their shallow refuges.

Young-of-the-year occupied shallow zones characterized by dense coral formations which were scattered throughout the lagoon (Galvin and Pointer, 1985). Between the ages of one and two years they reached an estimated length of approximately 70 cm, and began to mingle with adult conspecifics in the lagoon without displaying avoidant behaviour. However, they were not seen in the deeper regions, including the vicinity of Site C, and parts of the barren area separating Sections A and B.

Juvenile male sharks exhibited reduced growth rates compared with females, with some individuals only marginally larger than neonates upon initial observation at feeding sessions. Clasper development commenced approximately two years later, during the third to fourth year of life, with claspers initially appearing as small buds. Fully-proportional clasper development was typically achieved within one year, at approximately four to five years of age.

The onset of clasper development varied among individuals, possibly due to differences in birth dates—the earliest in September, and the latest in February (Porcher, 2005). In some males, clasper maturation occurred sufficiently early to enable mating the same year. However, in others, claspers developed later in the year and were not mature at the onset of the mating season. Consequently, while some males were capable of mating in their fourth to fifth year, others did not reach reproductive maturity until their fifth to sixth year, apparently due to the misalignment of the timing of clasper development with the reproductive season.

By the year preceding maturity, males measured approximately 80 cm to 1 m (estimated) and began a transition to the fore reef, corroborated by visual assessment of clasper length (Mourier et al., 2013). Juveniles were never seen on the fore reef.

One male juvenile, #19, was first identified on August 4, 1999, presumably in his second year. He was periodically observed at Site A during his maturation. Subsequent sightings when he was in his fourth year occurred at the fore reef site during a two year period in which he was not seen in the lagoon—from May 11, 2002, to April 26, 2004. In 2008, he was identified and re-sighted multiple times by Mourier et al., (2012) at their Opunohu observation site on the fore reef opposite Section A, as shown in

Figure 4.

This delayed or staggered maturation in males was paralleled in females, who likewise underwent a year of apparent maturity without successful reproduction. During their subadult phase, between 4 and 5 years of age, female sharks were approaching full size at an estimated 1.5 m and it was at this time that they settled into a home range. Although they mated, as indicated by the presence of extensive mating wounds, pregnancy was not observed, with the exception of one individual (Shark #29). In contrast, mature females became pregnant annually following mating, with no exceptions recorded. There were only two instances in which mature females failed to carry pregnancies to term. In one such case, the pregnancy terminated within three days of a spear or knife wound into the lateral body surface.

Subadult females retained a slender physique and displayed frequent acceleration. Their behavioural profile included an inclination for exploration and a tendency towards bolder actions. But by the subsequent year, they were more robust and displayed reduced agility as pregnancy progressed. In many cases, they also lost their earlier boldness (see Porcher, 2022, for an anecdotal account of sub-adult female behaviour).

3.2. Movements

Table 3 shows the percentage of identified adults and juveniles in each of the categories specified in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.2.1. Inter-Site Movements

Figure 5 shows blacktip reef shark movements observed between sites during the 6.5 years of the study.

Opunohu bay, at a width of approximately 300 m, separated Section A from the Papetoai lagoon. Each hosted a distinct community of females, juveniles, and occasional males. There was minimal evidence of inter-bay movement. Only one female, #179, consistently identified and re-sighted in the Papetoai lagoon, was recorded at Site A, appearing there twice in two different years. No individuals from the study lagoon were observed in the Papetoai lagoon.

Although Section A residents were not observed to cross the bay, they were sighted during daylight hours on the fore reef opposite their core ranges. At times they displayed behaviours suggestive of hunting as they moved parallel to the barrier reef beneath breaking waves. Blacktip reef sharks were frequently observed coming over the reef with incoming waves, suggesting that hunting fish beneath the waves breaking along the fore reef might constitute a component of their predatory repertoire. Females visited the fore reef more frequently than fore reef males entered the back reef.

In Section E, 67 % of the observed female blacktips had already been identified at Site C. Only two unidentified females were seen there. However, no females identified at Site A were ever sighted in that central part of the lagoon. Further, of the 37 females documented at Site C, only 7 (19 %) were ever sighted in Section A, typically on a single occasion. Adult individuals observed at Site C appeared to be transients, with different individuals present at each session and no residents identified. Juveniles seemed to avoid this location, with only one sighting of two older juveniles travelling together. Logistical constraints precluded additional sessions at Site C and in Sections D and E, which might have further elucidated these patterns.

One unusual female, designated #351, was first identified at Site C and subsequently re-sighted there on five occasions. She was also recorded at Site A during 22 sessions and at Site B during 13 sessions, indicating repeated passages along the western side of the lagoon. Yet, despite this extensive sighting record, she was only intermittently present in the study area, and her core range was never located. Her irregular appearances—usually months apart and often in association with different rare transient females—suggest that she was passing through during wider movements rather than residing locally.

3.2.2. Males

The male blacktip reef sharks that roamed the back reef displayed reduced site fidelity to core ranges compared with females; their Residency Indexes were generally lower. They attended feeding sessions irregularly throughout the year, with some appearing infrequently. Males were seen to traverse larger core ranges and exhibited greater daily mobility than females. During the reproductive season, they were frequently absent, sometimes for periods as long as five months. In contrast, males ranging the fore reef typically appeared on the back reef solely during the mating season (November to March; Porcher, 2005), arriving in pairs or small groups (<6) and not associating with lagoon-ranging males.

Only one male identified at the fore reef site was recorded at Site A (on a single occasion), and another had originally been identified—seen only once—at Site C. At the fore reef site, water depth was approximately 7 m, and since male blacktips moved near the seafloor, their identification required diving to the bottom to sketch dorsal fin markings on both sides while maintaining continuous visual contact and without resurfacing for air. Consequently, most males encountered on the fore reef remained unidentified, limiting their representation in the dataset. Nonetheless, these unidentified individuals were verified to be distinct from those previously identified on the back reef.

3.2.3. Colouration

A distinction in colouration was seen in blacktips ranging the fore reef, as opposed to the back reef, which reflected their respective habitats. Those residing on the fore reef, and remaining near the seafloor where they were shielded from solar radiation, exhibited light brown or yellow-ochre hues. In contrast, the sharks residing in the lagoon were subjected to prolonged sunlight exposure in shallow waters, and displayed dark brown or grey pigmentation. This difference is shown in

Figure 6.

Such chromatic variation provided a reliable indicator of an individual’s primary habitat. Similar sun-induced colour changes in shallow-water environments have been documented in other shark species, including nurse sharks (Johnson, 1978) and hammerheads (Lowe and Goodman-Lowe, 1996). However, colour also has a genetic basis, for neonates varied from pale yellow-ochre, to bronze, brown, and grey; most were variations thereof. In addition, mating and parturition were observed at times to result in a sudden, and at times extreme, colour change, which suggests hormonal influences.

3.2.4. Females

Resident female blacktip reef sharks exhibited pronounced fidelity to their core ranges while pursuing a distinct roaming pattern. Some were absent for only about two weeks during mating and again for parturition, while others were absent for spans of up to three months during the period of reproduction from September to April (Porcher, 2005). Occasionally, individuals were absent outside this period, and infrequently, rare transient females, alone, or in groups of two to six, traversed the study area. No consistent behavioural ‘type’ (Jacoby et al., 2014) emerged since each individual appeared to follow a unique pattern of movement.

Their daily behavioural routines also displayed substantial variability. Some individuals, for example, repeatedly navigated the same coral formations at nearly identical times on successive evenings for multiple nights then were absent from the area. There were days when the resident females were not in the western part of the lagoon, contrasted with occasions when they were there, socially interacting with groups of infrequent transients. On most days at midday, the resident females were resting in a wide barren region that divided Sections A and B (Porcher, 2023a) while, occasionally, no reef blacktips were there at midday.

3.2.5. Juveniles

Unexpectedly among the juveniles, it was the smallest, the pups, who exhibited the highest percentage of individuals sighted once, or for a short period only. Throughout the study, a stream of small juveniles was observed traversing the area, with no subsequent re-sightings. Whether these individuals died or settled elsewhere—and the extent of their dispersal—remained unknown. Only two (#29 and #36), initially identified as juveniles passing through, were later re-sighted as subadults, at which time they established residency in the region.

Given the research emphasis on identifying adults, coupled with the pups’ tendency to remain beyond visual range, the definitively-identified pups represent a small subset of their true numbers. Of the initial 581 blacktip reef sharks identified, those insufficiently documented for reliable future recognition and culled from the data set were mostly small juveniles seen only once, indicating that their actual abundance significantly exceeded the recorded figures.

3.2.6. Periodic and Rare Transients

While many transients were solitary, they also arrived in groups of up to six individuals—males, females, and juveniles of all sizes. There was often high-velocity interaction with the residents on their arrival. Especially when groups of females passed through, residents and transients would accelerate through the coral habitat surrounding the feeding site, following each other and moving nose-to-tail or in parallel (Porcher, 2023a). Since companion resident females were not systematically seen together because of their circling roaming patterns (Porcher, 2023a) the movements of consistent travelling companions were most discernible among rare transients who maintained the same associates across multiple years.

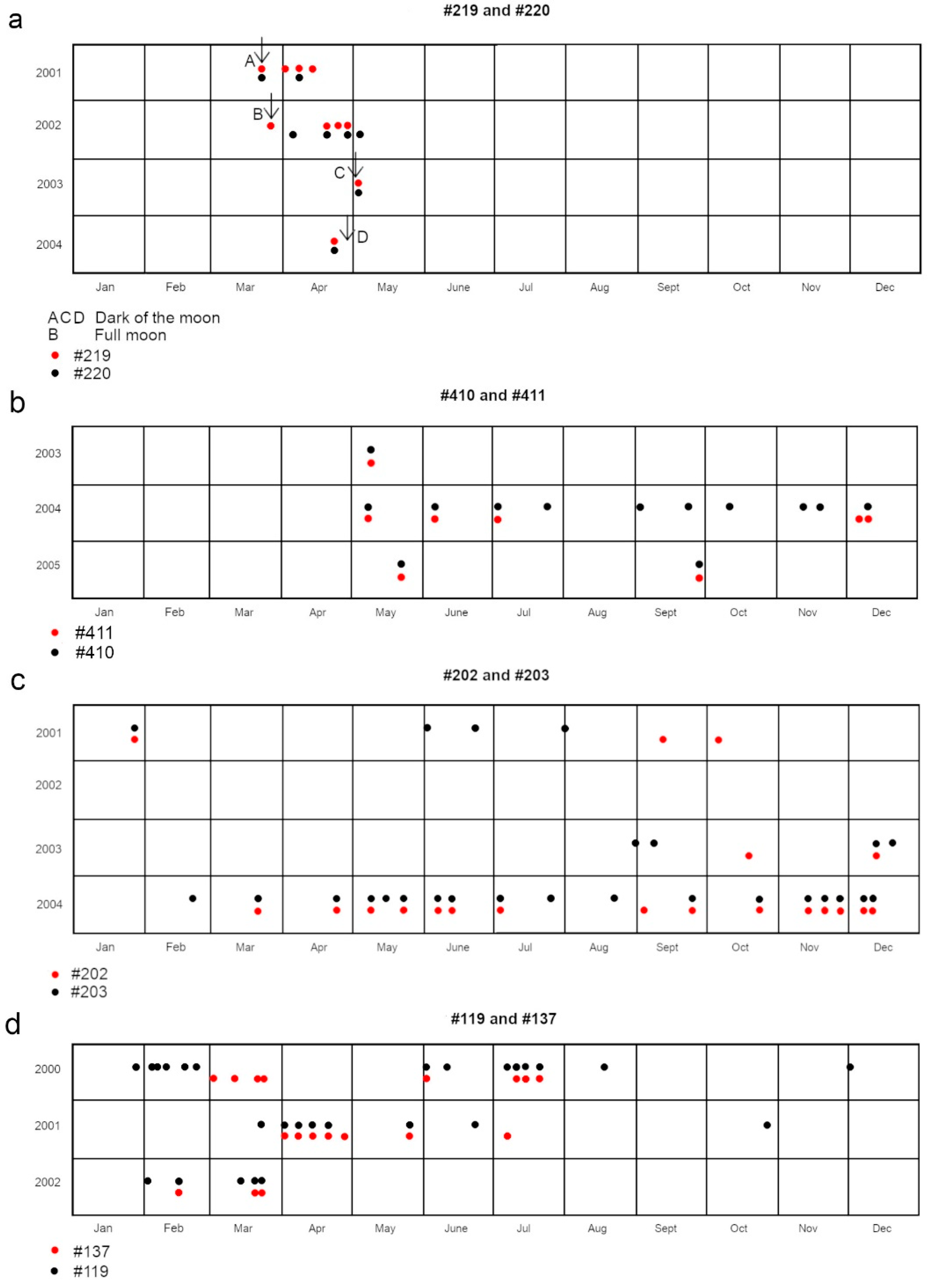

Figure 7 shows four such pairs.

The arrival of these transient groups frequently aligned with the light and dark phases of the lunar cycle, with groups typically lingering in the area until the next lunar phase transition—approximately two weeks—before leaving. On several occasions, certain female residents temporarily departed their core ranges to accompany these departing groups of conspecifics along the back reef. Their behaviour underscored the species’ inclination toward socialization (Mourier et al., 2012) and affinity for interactions with many of the female transients.

Certain transient groups of females were consistently accompanied by a distinct male who typically entered the observation site one to two minutes ahead of the females.

Rare female transients moving through for parturition often displayed a pattern of annual return within a few days of the date of their appearance the previous year.

3.3. Influences on Blacktip Reef Shark Movements

The primary influences on the blacktip reef sharks’ movements were the reproductive season and the lunar cycle.

3.3.1. The Reproductive Season

The reproductive period commenced in September, marked by gravid transient blacktips traversing the study area. Unidentified females passing through at this time were documented throughout the study. Concurrently, resident females approached parturition, then were absent, looking emaciated on their return two or more weeks later.

After a resting period of 1.5 to 2 months, resident females began to display mating wounds, while groups of males were observed arriving in the lagoon after sunset. These males, seen exclusively during the mating season, were presumed to inhabit the fore reef, as did the majority of male conspecifics.

An analysis of the percentage of adult blacktip transients present at the observation sessions during the period of regular sessions between 1999-04-11 and 2002-05-11 in Section A (247 sessions) is shown in

Figure 8. This used unweighted non-linear regression (the variances were homogeneous), treating the frequencies as binomial (SigmaPlot v16; Grafiti, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The calculation is shown in

Table 4.

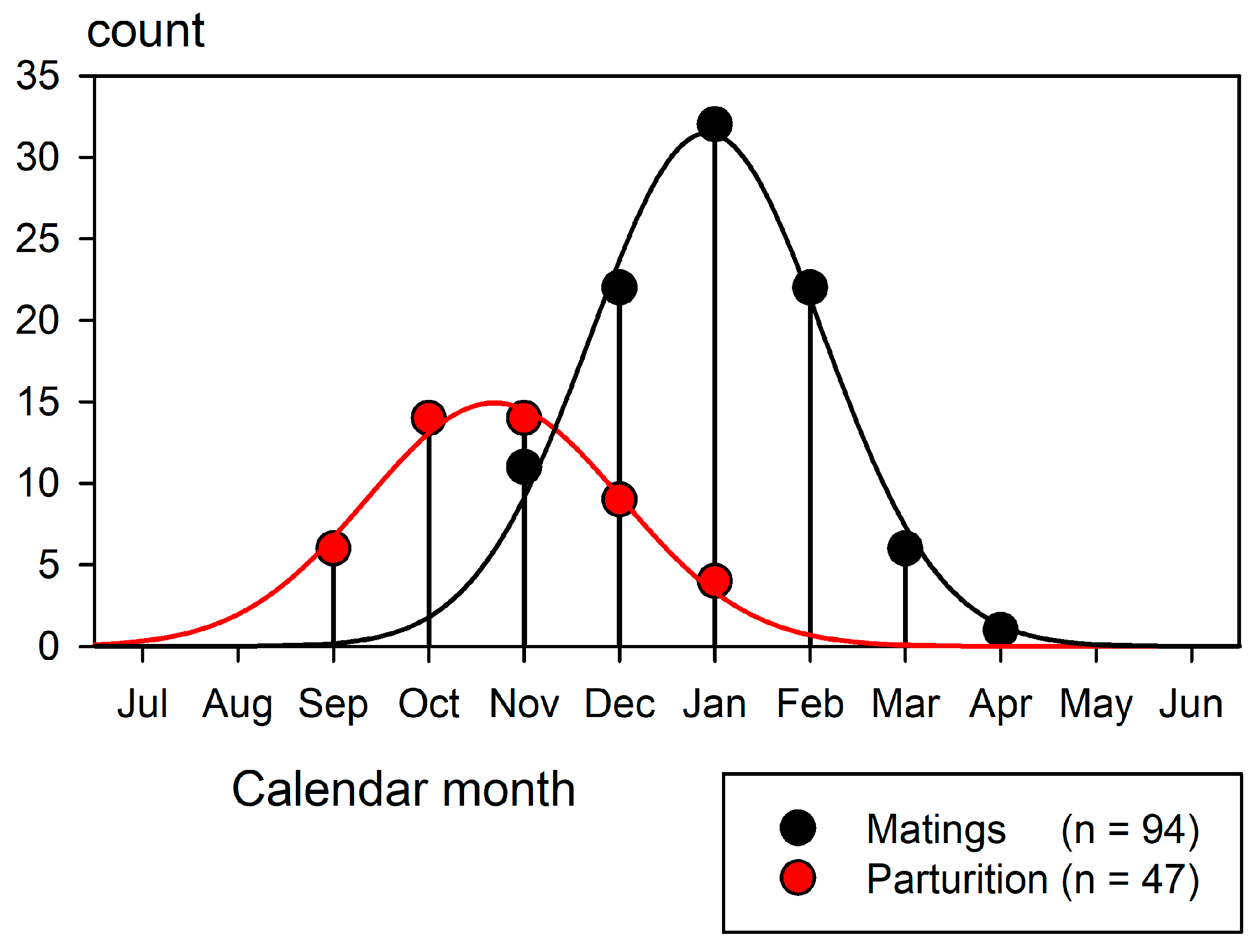

Mating begins in November and continues until the end of March as each female follows her own temporal cycle (Porcher, 2005). Parturition begins in September and continues until January, concluding a gestation period of 286 to 305 days (Porcher, 2005). Each female again mates 1.5 to 2.5 months after parturition to fulfil an annual reproductive cycle.

Figure 9 shows mating and parturition recorded in each month (Porcher, 2005).

A comparison with

Figure 8 illustrates the influence of the reproductive season on the blacktips’ movement patterns. A substantial portion of their travels were driven by this powerful instinctual imperative.

3.3.2. The Lunar Phase

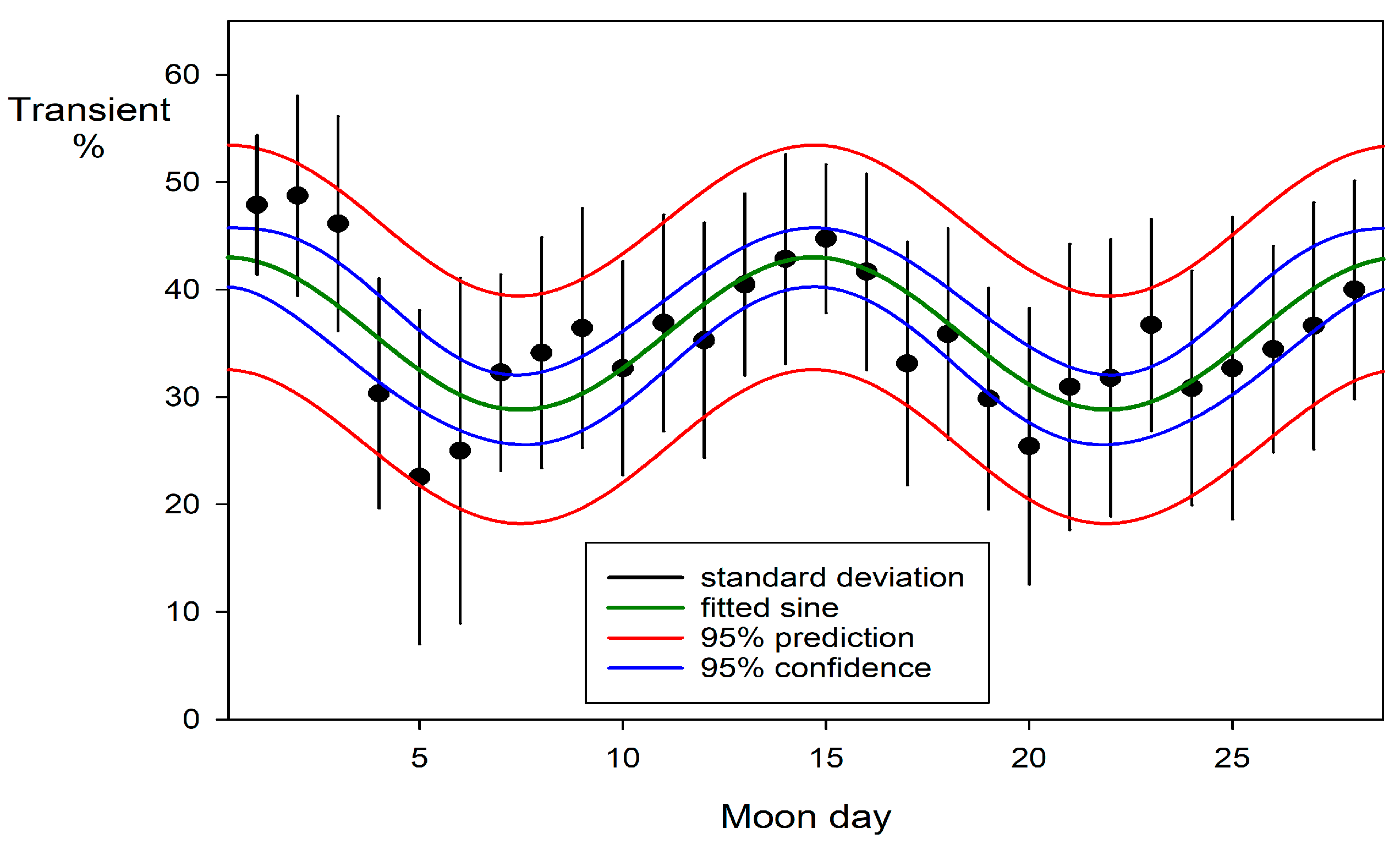

The movement patterns of the identified blacktip reef sharks with respect to the lunar day were analysed in similar fashion to the monthly data above. A notable correlation with lunar phase (

Table 5,

Figure 10) was exhibited, as evidenced by the numbers of transients recorded at feeding sessions across each lunar day. Peaks occurred at both new and full moon.

Not only were blacktip movements correlated with the lunar phase; their behaviour also appeared to be strongly influenced by it. During full moon periods, shark gatherings tended to accelerate more suddenly and frequently and individuals moved at greater velocity, particularly during social interactions. Most instances of sharks ‘slamming’ the observer’s kayak (Porcher, 2022; 2023a) occurred during full moon sessions. In contrast, certain transients tended to appear in the region during the dark lunar phase (

Figure 7).

3.3.3. Unusual Sessions

A distinct pattern emerged of sessions that deviated from the norm. These occurred sporadically with intervals of many months. Only 12 were documented during the 6.5-year study, and most correlated with the lunar phase. These sessions were characterized by the appearance of up to twice the usual number of blacktips, including a high proportion of infrequent transients. Social interactions featured high-velocity, synchronized movements throughout the area (Porcher, 2023a). Conversely, an opposing trend occasionally emerged during full moon phases, marked by the absence of the resident females and the attendance of only juveniles and one or two lagoon-dwelling males.

Of these unusual sessions, six (50 % of the total of 12) coincided with the full moon. During one such session, two groups of rare transients arrived, including individuals #219 and #220, as well as #119 and #137 (

Figure 7). Four sessions (33 %) occurred during the dark lunar phase, while the remaining two (17 %) took place when the moon was 42 % illuminated (lunar day 7), on 2000/07/07/ and 2000/11/03. The latter session was notable for the appearance of the Papetoai resident female (#179), marking one of her two recorded visits to Section A. A rare periodic male transient (#103), present in the area solely during November and December, was also observed at this session as well as during #179’s second documented appearance in Section A.

An intriguing associated observation involved the presence of a sicklefin lemon shark at six sessions over the 6.5-year study period, three of which were at such unusual sessions. Four of the lemon shark visits aligned with the full moon, while the remaining two coincided with the dark lunar phase. This species infrequently entered the back reef; juvenile blacktips use those shallow waters as a refuge from such large predators.

3.3.3. Other Influences

During storms, the heightened oceanic swell transformed the lagoon into a quasi-riverine environment. The large female blacktips exhibited reduced manoeuvrability in strong currents, due to the energy expenditure required to navigate the coral habitat under turbulent conditions. Consequently, fewer adult females were observed in the lagoon when the current was strong. In contrast, the small juvenile sharks, characterized by a streamlined morphology and a higher surface-to-volume ratio, demonstrated greater ease in navigating turbulent conditions. Though much smaller, their caudal fins were nearly comparable in size to those of the large, heavy-set females, facilitating efficient propulsion through the environment during periods of high turbulence.

Under calm conditions, the average attendance of adult sharks across 149 sessions was ~24. In contrast, during 41 sessions marked by strong currents, the average adult attendance dropped to ~18. Notably, in more extreme conditions, adult female attendance was close to zero, with only a few juveniles present.

An unidentified influence resulted in the evacuation of the blacktip communities under human observation on Mo’orea Island around July 23 to August 5, 2002 (Porcher, 2023b), including the smallest pups from their shallow coral refuges. At that time, dive clubs held shark dives at different sites in the lagoons and in the ocean, so blacktip presence was ordinarily confirmed daily. They too found this absence. Though the occasional juvenile male was spotted during the following days both by this observer and on two occasions at a shark dive, the main body of the community remained absent; it returned between August 2 and 5.

In August 2003, when a Singapore-based company began finning the reef sharks, those not immediately killed were absent. Though some reappeared within ten days, most took more than two weeks. A few did not reappear in their core ranges until the same period of the following lunar cycle. As a result of this tendency, and the ongoing slaughter that removed all the elderly females, as well as nearly every mature blacktip under observation, the shark communities originally observed never returned to their former state. By the time international pressure won their protection in 2006, the population of the back reef consisted of juveniles. (The adults were believed to leave the back reef and roam the ocean at night [Richard Johnson, pers. comm.] where they were vulnerable to fishing vessels. But evidently the juveniles did not, for they alone survived). The reef sharks inhabiting the waters on some of the islands in Polynesia were completely fished out, while observers in the wilder parts of the island nation reported countless vessels laden with drying shark fins.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of Observations

While it could be argued that the weekly provisioning sessions influenced the behaviour of the reef sharks familiar with them, several factors mitigate this concern. Provisioning was limited to small amounts of fish scraps—essentially skin and bones—obtained after filleting at local fish shops. Given once a week, in minimal amounts, they provided very little nutritional value for the numbers of sharks attracted. In sharp contrast, shark feeding dives for the tourist trade took place once or more times daily (Mourier et al., 2021) directly across the barrier reef from Section A and at times included whole squid (Esposito et al., 2022). The negligible nourishment and low frequency of the feeding sessions in the present study suggest that the blacktips continued to meet their energetic needs through natural foraging without altering their broad-scale movement patterns. They captured fish with effortless precision whenever they chose to feed.

Multiple lines of evidence support this interpretation. Shark gatherings were restricted exclusively to the sunset feeding window. In no instance of the more than 300 random visits during the day to Site A over the 6.5 years of the study was any congregation observed outside of that period. Resident individuals met the observer only at the edge of the lagoon and followed the kayak to the site, demonstrating responses to specific cues rather than altered habitat use. No shark attended all feeding sessions; the Residency Index for the three immediate residents around the Section A feeding site (#1, #2, and #3) was 0.73 to 0.79. Individuals often missed sessions, they did not stop their wide-ranging movements to stay in the area because of them, and in spite of them, the greatest number of individuals in all categories were those who passed only one time, or for one short period of time. The fish scraps did not cause abandonment of natural ranging behaviour. These findings are consistent with much other work showing that limited provisioning exerts minimal influence on shark movements (Maljković and Côté, 2011; Abrantes et al., 2018; Heim et al., 2021; Mourier et al., 2021; Séguigne et al., 2023b; Matley et al. 2025). The intentionally very limited feeding sessions provided a weak conditioning framework that enabled extended behavioural observation. Further, blacktip behaviour indicated that these gatherings functioned not only as feeding events but also as socially-significant interactions.

Although blacktip reef sharks are known to exhibit peaks in activity at night (Papastamatiou et al., 2009; Mourier et al., 2013), nighttime observations were not feasible due to the lack of visibility and safety concerns given the study sites’ 1 km distance from shore. However, the 6.5-year dataset—comprising 506 hours across 501 observation sessions—helped to mitigate this limitation. The blacktips presented a peak of activity in the low-light period at, and just after, sunset, as seen by other researchers (Papastamatiou et al., 2009; Mourier et al., 2013). Papastamatiou et al., (2015) found that at that time blacktips not only have a sensory advantage over their prey, but also a thermal one.

For this reason, 67 % (337.8 hours) of the observations were conducted during the low-light conditions around sunset. Alongside numerous unprovisioned observations, the study documented natural patterns of movement and habitat use across 475 identified individuals, which exceeds, by many times, that of any telemetry study done so far on the species. By increasing representation of the observed patterns, it enhances confidence in the detection of behavioural trends, including inter-individual variability and differences between the movements and behaviour of males, females, and juveniles. Such a large dataset also offers insights into population-level patterns that may be obscured in smaller-scale studies. Building on an existing ethogram of 35 context-specific behaviours observed in this species (Porcher, 2023a), the present study of an originally undisturbed community of blacktips, provides a robust ethological foundation for expanding current understanding of the behaviour of C. melanopterus in terms of spatial ecology.

4.2. The Community

The marked site fidelity observed in C. melanopterus aligns with the findings of other researches in French Polynesia (Mourier et al., 2013) and is corroborated across diverse locales, including Australia (Speed et al., 2011; Chin et al., 2013; Schlaff et al., 2020), Palmyra Atoll (Papastamatiou et al., 2009, 2010), and Aldabra Atoll (Stevens et al., 1984). Physical landmarks and environmental features influenced their distribution and in part delineated their ranges (Papastamatiou et al., 2010, 2025; Eustache et al., 2023). The back reef predominantly hosted adult females and juveniles, with scant male presence, while the fore reef was primarily occupied by males (Mourier et al., 2013). The spatial separation between fore reef and lagoon males suggests that the two groups occupy distinct ecological and social domains.

Sexual segregation is common in shark populations, and this is frequently interpreted as a female strategy to reduce male harassment and risk of injury (Mucientes et al., 2009; Wearmouth and Sims, 2008; Jacoby et al., 2012). However, in Mo’orea, the CRIOBE work and our observations indicate that segregation in C. melanopterus is the result of female habitat choice and reproductive needs, which result in spatially-structured mating movements (Mourier and Planes, 2013).

Throughout this 6.5-year study, no instance of harassment by lagoon males sharing ranges with females was seen. Mating-associated biting was restricted to periods of female receptivity, and neither sex excluded the other from potentially resource-rich habitats. During incursions of male groups from the fore reef—presumably for mating—resident females were seen to join with them. They engaged without avoidance, as has been noted elsewhere (Mourier and Planes, 2013). Consequently, sexual segregation in C. melanopterus appears unrelated to male aggression or female apprehension.

C. melanopterus is sexually dimorphic (Carrier et al., 2012), which is reflected not only in body size and shape, but also in divergent habitat use and behavioural instincts. Evolutionary pressures have likely selected for females inhabiting shallower, nearshore waters, where reduced predation risk, enhanced prey availability, and warmer conditions, provided both safety and energetic benefits during gestation (Mourier and Planes 2013). In contrast, testosterone-driven males exhibited greater roaming tendencies, possibly as a strategy to maximize mating opportunities by encountering receptive females across larger areas. Similar patterns of sexual segregation have been documented in other elasmobranchs, such as lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris) (Morrissey and Gruber, 1993), tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier); (Heithaus et al., 2002), and scalloped hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini) (Klimley, 1987), suggesting that spatial and behavioural differentiation between the sexes is a widespread evolutionary strategy in sharks. This segregation reduces intraspecific competition for resources while improving reproductive success, thereby reinforcing instincts that continue to shape the ecology of C. melanopterus today.

Chin et al. (2013) documented the exclusive presence of juveniles and adult females in shallow refuges at Magnetic Island, Queensland, with subadults and males largely absent. In contrast, Papastamatiou et al. (2009, 2010) reported a more equitable male distribution across Palmyra Atoll lagoons, with minimal sexual segregation. In the present study, as well as the females, the lagoon accommodated juveniles of all ages alongside a few males. This variation suggests flexibility in segregation behaviour and habitat utilization within the species.

The transient nature of blacktip reef sharks at Site C might be attributable to its widely spaced, predominantly dead, patch reefs with reduced fish abundance, compounded by the noise of boat traffic from a shoreline hotel featuring overwater bungalows (Bleckmann and Zelick, 2009). It is to be noted that generous daily shark provisioning for tourists by the hotel, for a year prior to these observations, had not induced residency in this suboptimal environment, which suggests that the minimal scraps used in this study would have had negligible effect in that sense.

The utilization of small and shallow nursery areas by neonates aligns with findings in other studies (e.g. George et. al., 2019; Papastamatiou et al., 2009; Bouyoucos et al., 2020; Trujillo Moyano, 2023; Eustache et al., 2023). These shallow regions were typically inhabited by a variety of juvenile fish, providing suitable prey for the neonate sharks.

However, the co-occurrence of adults with pups of approximately one year of age challenges current theory, which considers that size segregation reduces predation on neonates and juveniles (Morrissey and Gruber, 1993; Wearmouth and Sims, 2008). Observations by Chin et al. (2013), as in the present study, consistently found that adult females interacted with small juveniles in a manner analogous to larger conspecifics, i.e. non-aggressively. The gradual exploration away from nursery areas by pups over time was also noted by Bouyoucos et al. (2020).

Comparable ontogenetic habitat shifts are evident in lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris) at Bimini lagoon, where juveniles transition to deeper waters with maturity (Gruber et al., 1988). This suggests that it is a successful strategy used by other species as well as by blacktip shark pups for predator avoidance (Bouyoucos et al., 2020; Trujillo Moyano, 2023; Eustache et al., 2023).

4.3. Movements

Categorizing the movement patterns of blacktip reef sharks in this study proved challenging due to substantial inter-individual variability. Although previous studies have reported sedentary tendencies and site fidelity in reef blacktips (Stevens, 1984; Papastamatiou et al., 2009; Mourier et al., 2013; Chin et al., 2013, 2016), our data emphasize movement as a prominent driving instinct. Across all sighting categories, most identified individuals were transients observed either once or for a brief span of time; 82.7 % of males and 62.1 % of females. This predominance is particularly striking given that these individuals were unfamiliar with both the observer and the observation setting, making them less likely to enter the feeding site and remain within visual range long enough for identification and inclusion in the dataset

The unidentified sharks were predominantly juveniles and males because the observer focused first on identifying the mature females at the sessions as they were the primary occupants of the back reef. Further, their slower movements and greater willingness to approach and circle the fish scraps alongside resident females facilitated identification (Porcher, 2023a). Consequently, many more males and juveniles remained unidentified and were excluded from the dataset. Nonetheless, it was these groups that exhibited the highest rates of transience, underscoring their contribution to the observed movement dynamics.

4.3.1. Males

Male-biased dispersal was found to be a life-history trait in French Polynesia by Vignaud et al. (2013), who considered that otherwise philopatry (Mourier and Planes, 2013) each year (Porcher, 2005) would prevent the species from colonizing new areas. The males inhabiting the back reef displayed dark grey-brown colouration, except upon returning from reproductive season excursions, when they re-appeared significantly paler. This change in pigmentation (Johnson, 1978; Lowe and Goodman-Lowe, 1996) suggests extended oceanic sojourns (Mourier and Planes, 2013). Since the females occupy the lagoons, the males could have circumnavigated Mo’orea while remaining in those shallow waters. However, their colour change indicates that instead they travelled in the ocean, possibly to visit other islands (Mourier and Planes, 2013; Vignaud et al., 2013; Schlaff et al., 2020).

Further, given their observed travel speed—approximately 1 km in 35 minutes—a blacktip reef shark could theoretically circumnavigate Mo’orea (≈60 km) within a day or two. Males that typically ranged the study area were nonetheless absent during the reproductive season for extended periods—usually two to three months and on rare occasions up to five. Such prolonged absences reflect a behavioural pattern of extended roaming, likely to other islands (Mourier and Planes, 2013; Vignaud et al., 2013; Schlaff et al., 2020).

The males observed on the fore reef across from Section A were not seen inside the lagoon, even during the reproductive season. This suggests that males did not merely cross the barrier reef to mate with nearby females but likely ranged farther afield to reproduce, implying that mating interactions may occur across larger spatial scales than previously assumed.

A unique observation of coordinated group movement occurred during the return of the community to the study lagoon at the end of their ten-day evacuation in July–August, 2002 (Porcher, 2023b). Several residents of Sections A and B—adults and subadults—came into view from the direction of the lagoon perimeter in a widespread formation. Several small male juveniles were travelling at high velocity some metres ahead of the others; some were tens of metres ahead.

Then there were the cases in which certain transient groups of females were accompanied, on multiple occasions, by one regularly-associated male individual, apparently exceptions to the usual rule of sexual segregation; that male entered the observation site each time in advance of the females by a minute or two. Although uncommon and not quantified, there were instances in which the same infrequent male and female transients appeared at the same sessions, time after time, though these were at different sites and months or years apart. Such co-occurrences cannot be taken as evidence of pair bonds, but they suggest that some male-female associations may extend beyond strictly reproductive encounters and warrant further investigation.

These observations imply that the roles of males—both juveniles during the re-entry event and adults in association with females, may be more nuanced than previously recognized. They highlight the little-known and potentially important dimensions of social complexity in blacktip reef shark communities.

4.3.2. Females

While male-biased dispersal would help to consolidate blacktip communities in new areas (Vignaud et al. 2013; Schlaff et al., 2020), females would be required to establish them. To populate the island chains that formed across the Pacific Ocean in recent geological times, females as well as males necessarily traversed vast oceanic distances. Mo’orea formed between 1.5 and 2 million years ago (Neall and Trewick, 2008), and blacktip reef sharks are distributed across the Indo-Pacific, from the Red Sea and East Africa to the Hawaiian Islands and French Polynesia, from their origin in the coastal regions near Asia (Maisano Delser et al., 2019).

Female philopatry ties females to specific sites, reducing their likelihood of colonizing distant areas. However, in this species the trait has been shown to be variable (Eustache et al., 2023). Not all females always return to their birth site for parturition. Travels over greater distances could have been driven by environmental pressures, resource competition, or stochastic events such as storms and currents, resulting in females reaching new reefs or islands, especially during glacial periods with lower sea levels exposing more reefs.

Subadult females possibly played a critical role. Their behavioural repertoire is characterized by a pronounced tendency for exploration, risk-taking, and boldness (Porcher, 2022), traits that may have facilitated long-range dispersal events across reef networks, particularly during favourable environmental conditions such as Pleistocene sea level fluctuations. Once established in new areas, females could have anchored new populations through philopatric behaviour, while males, with their greater tendency to roam, enabled the persistence and diversity of newly-established communities by mating across fragmented populations and reinforcing the gene flow.

Though Vignaud et al. (2013) found that C. melanopterus rarely travels more than 50 km to other island groups in French Polynesia, in Australia, where habitats are less fragmented, Speed et al. (2016) reported significantly longer parturition-related movements in female C. melanopterus—as long as 275 km—while mean activity space estimates were 12.8 ± 3.1 km² for adults and 7.2 ± 1.3 km² for juveniles. This illustrates the species’ adaptability across varying habitat configurations, and underlines the reef blacktips’ potential for long-distance movements.

Sharks navigate using infrasound (Myrberg, 1978) and the Earth’s magnetic field (Klimley and Ainley, 1996; Keller et al., 2021), with chemoreception likely enabling recognition of distinct island chemical signatures. Undoubtedly a unique scent trail, long and slow, drifts through the ocean from each island, carried by the outflow from its rivers and lagoons. Sharks traversing ocean stretches could use such island scent trails for navigation. The Pacific’s archipelagos form a network of reefs and islands that could have acted as stepping stones for C. melanopterus’ expansion. The species likely colonized these areas incrementally, with both males and females occasionally moving to nearby islands over generations. Given the pronounced individual variation observed, certain C. melanopterus individuals may undertake journeys that far exceed the distances inferred from limited datasets. For instance, among several hundred identified reef blacktips, one exceptional individual, #109 (Porcher, 2022), stood out for her distinctive behaviour, influence within the community, and unusually wide-ranging movements. Her example underscores the potential for exceptional variability in individual mobility, hinting that some sharks may traverse distances well beyond those recorded to date.

Female #351 provides another illustration of an individual with an exceptional ranging pattern. She was repeatedly sighted at multiple sites across the study lagoon, yet showed no evidence of having a core range in the region. Her pattern of arriving with rare transients suggests that certain individuals may undertake extensive movements linking different lagoonal or reef systems. Such movement patterns, though possibly rare, could be ecologically significant, facilitating genetic connectivity and demographic exchange among island populations. If beneficial, sporadic long-range travel could constitute an innate behavioural trait in reef blacktips, even if infrequent.

The presence of such wide-ranging individuals highlights the potential for overlooked spatial linkages within archipelagic shark populations, emphasizing the need for conservation strategies that extend beyond site-based protection. For instance, a study at Ningaloo Reef, Australia, revealed that C. melanopterus ranges extended well beyond MPA boundaries (Speed et al., 2016). Given the naturally limited population sizes of reef sharks, particularly in fragmented habitats (Vignaud et al., 2013), effective conservation strategies must account for their dispersal patterns (Speed et al., 2016).

In this study, the lack of sightings of Papetoai’s resident sharks in the study lagoon could stem from a preference for westward movement, driven by geographical constraints. Papetoai’s lagoon is narrow, with nursery habitats and other features predominantly located westward, and along Mo’orea’s west coast (Mourier et al., 2013). Observations in Papetoai excluded the reproductive season, when some female residents from the study lagoon might have traversed Papetoai en route to west coast nurseries. We found no clear explanation for the absence of west-to-central movements among Section A residents, in contrast to the more extensive use of space by Section E females, who were at times observed in the central lagoon. The back reef habitat was relatively homogeneous in quality and structure, so this spatial asymmetry cannot be attributed to any obvious environmental differences. It suggests that factors beyond habitat uniformity, such as social dynamics, resource distribution, or individual-level behavioural strategies, were shaping movement patterns. Papastamatiou et al. (2010) noted limited inter-lagoon movement and variable residency durations across regions, though the underlying drivers—potentially trophic ecology or social factors—remain unresolved (Papastamatiou et al., 2010). Our findings are consistent with this broader picture of fine-scale, context-dependent spatial ecology in C. melanopterus.

Most gravid transients observed in Sections A and B were likely migrating toward west coast nurseries for parturition (Mourier et al., 2012, 2013). However, some north shore Mo’orea females have been documented travelling to other islands to give birth (Mourier and Planes, 2013). Resident females absent for extended periods, as well as annual transients, and some of those sighted just once, might also have been undertaking inter-island journeys.

4.3.3. Juveniles

Blacktip reef shark pups with an estimated length ≤ 70 cm exhibited the highest proportion (60.5%) of juveniles observed within the study region once or for a single period. This finding is unexpected, particularly given that the dataset is biased against such an outcome due to the reduced likelihood of positively identifying them. Nevertheless, a consistent stream of the smallest juveniles traversed the study area throughout the investigation, without reappearing.

If adults undertake extensive journeys, including inter-island movements (Mourier and Planes, 2013), to return to their natal nurseries, then juveniles must initiate dispersal from their birth areas prior to establishing a home range. Observations in this present study indicate that such dispersal may commence as early as 1.5 to 2.5 years of age. Similarly, Chin et al. (2013, 2016) reported that juveniles tend to exhibit short-term residency, supporting the notion of early dispersal in this species.

4.4. Influences on Blacktip Reef Shark Movements

4.4.1. Transients from Different Origins

Research on C. melanopterus (Mourier et al., 2012) and other shark species has identified a tendency to form social bonds with companions. Strong interpersonal bonds have been documented in bull sharks (Bouveroux et al., 2021) and grey reef sharks (Papastamatiou et al., 2020). Consistent with these findings, the present study has documented companion sharks integrating with other groups before separating to continue their journeys together—a dynamic termed ‘fission and fusion’ (Aureli et al., 2008; Haulsee et al. 2016; Papastamatiou et al., 2020).

In this investigation, most blacktip reef sharks had preferred companions, although some, including infrequent transients, were consistently solitary. The overlapping core ranges of resident sharks, frequent path crossings, regular mutual sightings, and coordinated departures from the study area suggest that these interactions foster the formation of robust bonds among select individuals (Papastamatiou et al., 2018). Multi-year associations and the evident excitement during social encounters highlight the importance of sociality in C. melanopterus (Mourier and Planes, 2012; Porcher, 2023a,b), a trait documented in other shark species (Papastamatiou et al., 2018, 2022; Klimley et al., 2023).

Long-term bonding is likely to be beneficial through enhanced safety in numbers. Resident sharks were observed approaching novel situations in groups (Porcher, 2023a), while solitary individuals tended to linger beyond visual range until they could approach with conspecifics. Such behaviour is indicative of social buffering (Kikusui et al., 2006), where collective presence mitigates stress in new or demanding contexts, and implies social complexity by demonstrating that emotions are involved in social relationships (Kikusui et al., 2006). Such emotional underpinnings could also drive reef blacktips to bond with the familiar individuals that share their ranges when traversing unfamiliar environments. Additional advantages include cooperative foraging and the leveraging of dual sensory inputs to locate prey (Papastamatiou et al., 2010), as found in a variety of other shark species including the great white (Carcharodon carcharias) (Klimley et al., 2000; Papastamatiou et al. 2022).

Over 6.5 years of observing Section A residents, it became apparent that companions frequently circled out of visual range, only to reconnect as their paths reconverged (Porcher, 2023a), a pattern likely to enhance foraging efficiency (Papastamatiou

et al., 2010). The sensory capabilities of reef sharks allow them to maintain awareness of conspecifics when out of visual range, suggesting that their associations may be mediated through a combination of olfactory, auditory, vibratory, and electrosensory cues. Unlike dolphins or primates, where close companions often travel side by side in stable units, blacktip reef sharks typically move independently, executing broad circular trajectories that bring them into regular but temporary contact with familiar individuals (Porcher, 2023a). This distinction underscores the need for caution when inferring social networks from co-occurrence data using software-based methods. Social network analyses of sharks often rely on the “gambit of the group” approach, in which individuals observed together—such as at a feeding site—are assumed to form an association (Whitehead and Dufault, 1999; Franks

et al., 2010; Mourier

et al., 2019). Yet the present study demonstrates that sharks attending the same session frequently originated from different regions (

Figure 8), sometimes from considerable distances. Thus, the sharks attending a feeding session do not form a social group. These findings suggest caution in applying standard social network assumptions to sharks, whose fluid and spatially expansive associations differ fundamentally from those of species with tightly-bonded group structures.

These nuances in association patterns become even more evident when considering the role of transients. Being non-territorial, resident blacktips exhibited an attraction to transients (Porcher, 2023a,c), and so were frequently observed in close proximity to individuals from other regions. At the same time, the species’ characteristic circling movement patterns meant that close companions only travelled side by side occasionally and briefly before arcing away again (Porcher, 2023a).

Transients that elicited the most excited social interactions (Porcher, 2023a) were often the rarest, suggesting that resident sharks maintain recognition of acquaintances encountered annually or less. Not only does this imply a capacity for long-term individual recognition, but also emotional contagion (Porcher, 2022), a phenomenon in which the arousal state of one individual induces similar emotional or physiological responses in others (Hatfield et al., 1993; Preston and de Waal, 2002). The rapid acceleration and intense social engagement observed when transients appeared indicate affective resonance among the sharks, comparable with the emotional contagion described for other social vertebrates (Kareklas and Oliveira, 2024). Given the complex travel patterns already documented for this species (Mourier and Planes, 2013; Maisano Delser, 2019) it is plausible that blacktip reef sharks maintain mental representations of conspecifics with distant home ranges with whom they share infrequent encounters. Such evidence strengthens the case for social and cognitive sophistication in this species and further cautions against assuming that co-occurrence at a given site reflects stable or enduring group membership.

4.4.2. The Lunar Phase

Unlike regions where lunar phase correlations align with tidal patterns, in French Polynesia, the tide is essentially solar, and Mo’orea lies very close to an amphidromic point (Pickard and Emery, 1990; Egbert and Ray, 2000). This distinction results in only minor fluctuations in water levels, with a mere few centimetres’ difference between low and high tides in lagoons, along their perimeters, and at the passes (Hench et al., 2008). Water depth in these zones is predominantly governed by oceanic conditions which determine the volume of water spilling over the reef (Hench et al., 2008). Consequently, the observed correlation between blacktip reef shark movements and lunar phases cannot be attributed to the opening and closing of waterways. Lunar cycle associations have been documented in great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) (Klimley and Ainley, 1996) and aggregations of sharpnose sharks (Rhizoprionodon longurio) (Pérez-Jiménez et al., 2002), with both bright and dark phases proving significant. Conversely, Gallagher et al. (2021) found no lunar influence on the movements of Caribbean reef sharks (Carcharhinus perezii) or tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier).

The use of moonlight for navigation within complex coral habitats is plausible, offering visual cues to avoid obstacles. However, the utility of the dark lunar phase is less apparent. It is possible that blacktips exploit this period’s darkness to hunt fish, using their ampullae of Lorenzini. Certain rare transients consistently arrived in the study area during or immediately following the dark lunar phase (

Figure 7a). As these individuals are most likely to originate from other islands, their timing suggests an awareness of reduced detectability (Porcher, 2023a), potentially advantageous for mesopredators vulnerable to oceanic shark predation (Frisch

et al., 2016).

4.4.3. Other Influences

The tendency for sharks to remain absent after some of their number are fished was regularly mentioned by the native Tahitians, who, traditionally, had wanted their sharks neither fished nor disturbed (Johnson, 1978). A similar response was observed in tiger sharks in the Bahamas, where they were not seen for approximately two months post-disturbance (Abernethy J, pers. comm., 2016).

The abrupt disappearance of blacktip reef sharks from Mo’orea’s north shore between July 23 and August 5, 2002, remains unexplained (Porcher, 2023b). Despite extensive investigation, no cause was identified that could explain the disruption of the population followed by the mass departure of all individuals across both back and fore reefs, including pups from their dense coral refuges. At the same time, the marine mammals appeared undisturbed, for during the shark disappearance a pod of humpback whales, accompanied at times by spinner dolphins, were resting in Opunohu Bay. Subsequently, not all the resident blacktips returned, and the pattern of residency seen in the lagoon prior to the evacuation was disrupted. Certain females did not return for another month, and others were no longer seen so often in their former home ranges. At Site B, where pups had formerly dominated the sessions, there were fewer. In spite of extensive investigation, no reason for their temporary absence was found. The event suggests an unknown pattern or influence at work which was perceived by sharks, but was not apparent to those investigating.

5. Conclusions

The dominant finding of this study is the central role of movement in the lives of blacktip reef sharks. While individuals show strong site fidelity to core ranges for periods, roaming emerges as a fundamental component of their behavioural repertoire. In both adults and juveniles, the largest proportion of identified individuals were observed only once or for one brief span of time, underscoring the prominence of this drive. This tendency was especially pronounced among small juveniles—an unexpected result that reveals the strength of the roaming instinct even at early life stages. Dispersal from natal areas seems to begin between one and two years of age.

Movements, including long distance movements (Mourier and Planes 2013; Vignaud et al., 2013), were strongly associated with the reproductive cycle and lunar phase. Pronounced individual variation, behavioural flexibility, and complex sociality were consistently evident among observed sharks. Their interactions, characterized by multi-year companionships and dynamic fission-fusion patterns, suggest capacities for individual recognition and social learning, aligning with findings in other shark species (e.g., Papastamatiou et al., 2020; Bouveroux et al., 2021; Guttridge et al., 2013).

The importance of movement across all categories of blacktips underscores the need for broader protective measures in the face of the hunt for sharks to supply the shark fin trade. MPAs must be redesigned to encompass the full extent of the movement ranges of this species, as demonstrated by instances where ranges exceeded protected boundaries (Speed et al., 2016).

The near-total depletion of adult blacktip populations during the course of the study illustrates the extreme damage caused by IUU fishing and highlights the urgency of securing effective protection for sharks. The ongoing threats posed by shark finning and at-sea processing for shark liver oil (Finucci et al., 2024) demand urgent international action (Pike et al., 2024). Given the lucrative and unsustainable nature of the shark fin trade, driven by high prices and rich customers with little interest in sustainability, a CITES Appendix I listing is recommended to ban international trade in all sharks, manta rays, devil rays, rhino rays, chimaeras, and their derivatives (Porcher and Darvell, 2022). Sharks should be reclassified globally as protected wildlife rather than commercial fishery resources. Ultimately, a binding international treaty to protect sharks, and threatened biodiversity more broadly, should be an urgent global priority (Dasgupta, 2021).

Figure 1.

The study lagoon divided to show the nominal study areas and the locations of the observation sites. South latitude and west longitude: A: −17.485568, −149.855474. B: −17.482010, −149.849751. C: −17.479502, −149.844196. E: −17.479668, −149.830348. Papetoai lagoon site: −17.485447, −149.870780. Fore reef site: −17.483705, −149.857041. (Area D was not used).

Figure 1.

The study lagoon divided to show the nominal study areas and the locations of the observation sites. South latitude and west longitude: A: −17.485568, −149.855474. B: −17.482010, −149.849751. C: −17.479502, −149.844196. E: −17.479668, −149.830348. Papetoai lagoon site: −17.485447, −149.870780. Fore reef site: −17.483705, −149.857041. (Area D was not used).

Figure 2.

(a) The numbers of identified sharks attending the sessions at Sites A and B between 99-04-11 and 05-09-29. The absences between approximately 02-07-23 and 02-08-05 when the sharks evacuated (Porcher, 2023b) are evident. Other breaks in attendance are due to bad conditions during the stormy months between November and February when not all sharks present could be identified, or the sites were inaccessible. Some peaks (green +) mark unusually animated sessions (3.3.3). There is a break in attendance when intensive shark finning began in August, 2003 and the subsequent disruption of the community is also clear; the numbers present were increasingly juveniles. (b) Expanded plot around the time of the disappearance event.

Figure 2.

(a) The numbers of identified sharks attending the sessions at Sites A and B between 99-04-11 and 05-09-29. The absences between approximately 02-07-23 and 02-08-05 when the sharks evacuated (Porcher, 2023b) are evident. Other breaks in attendance are due to bad conditions during the stormy months between November and February when not all sharks present could be identified, or the sites were inaccessible. Some peaks (green +) mark unusually animated sessions (3.3.3). There is a break in attendance when intensive shark finning began in August, 2003 and the subsequent disruption of the community is also clear; the numbers present were increasingly juveniles. (b) Expanded plot around the time of the disappearance event.

Figure 3.

The effect of the location of a random observation site with respect to two well-defined but overlapping blacktip ranges on the frequency of observation and thus the imputed residency. (Distribution within a core range is shown as normal for illustrative purposes only.).

Figure 3.

The effect of the location of a random observation site with respect to two well-defined but overlapping blacktip ranges on the frequency of observation and thus the imputed residency. (Distribution within a core range is shown as normal for illustrative purposes only.).

Figure 4.

Sightings of #19 both within the lagoon while a juvenile and during his transition to the ocean where he was sighted by Johann Mourier years later, still roaming the reef’s outer slope. (Occurrence symbols staggered vertically for clarity.) Data, and the images of #19 and the study site location provided by Johann Mourier, as indicated.

Figure 4.

Sightings of #19 both within the lagoon while a juvenile and during his transition to the ocean where he was sighted by Johann Mourier years later, still roaming the reef’s outer slope. (Occurrence symbols staggered vertically for clarity.) Data, and the images of #19 and the study site location provided by Johann Mourier, as indicated.

Figure 5.

Individual blacktip reef shark movement between sites. Each line shows the movement of one resident shark to another section. The colours represent the site where the individual was a resident or had been sighted most often.

Figure 5.

Individual blacktip reef shark movement between sites. Each line shows the movement of one resident shark to another section. The colours represent the site where the individual was a resident or had been sighted most often.

Figure 6.

a: Typical light pigmentation of fore reef dwellers. b: Darker pigmentation of back reef dwellers.

Figure 6.

a: Typical light pigmentation of fore reef dwellers. b: Darker pigmentation of back reef dwellers.

Figure 7.

Each dot represents one sighting of the indicated individual. a. The visits of blacktips #219 and #220 correlated strongly with the lunar phase, as indicated by the arrows in the legend. b. Blacktips #410 and #411 tended to arrive as the full moon phase was passing. In 2004, their first three visits took place a moon apart. c. Blacktips #202 and #203 travelled together at times but at other times they roamed separately. d. Blacktip #119 exhibited a distinctive appearance, characterized by unusually dark pigmentation, scattered white speckles, and a prominent white patch positioned symmetrically on each side of her head. In 2001, she was documented consistently at dusk across five consecutive sessions. However, at the sixth session, a similar individual, #137, appeared. This lookalike bore identical white patches on her head, though her overall colouration was marginally lighter. Their striking resemblance suggested a potential association based solely on morphology. Confirmation of their association emerged three months later when #119 and #137 arrived together, moving in a nose-to-tail formation.

Figure 7.

Each dot represents one sighting of the indicated individual. a. The visits of blacktips #219 and #220 correlated strongly with the lunar phase, as indicated by the arrows in the legend. b. Blacktips #410 and #411 tended to arrive as the full moon phase was passing. In 2004, their first three visits took place a moon apart. c. Blacktips #202 and #203 travelled together at times but at other times they roamed separately. d. Blacktip #119 exhibited a distinctive appearance, characterized by unusually dark pigmentation, scattered white speckles, and a prominent white patch positioned symmetrically on each side of her head. In 2001, she was documented consistently at dusk across five consecutive sessions. However, at the sixth session, a similar individual, #137, appeared. This lookalike bore identical white patches on her head, though her overall colouration was marginally lighter. Their striking resemblance suggested a potential association based solely on morphology. Confirmation of their association emerged three months later when #119 and #137 arrived together, moving in a nose-to-tail formation.

Figure 8.

Percentage of transients among the individuals attending feeding sessions during each month between 1999-04-11 and 2002-05-11 in Section A (247 sessions). The occasional missed sessions due to hurricanes and storms during December and January, central to the reproductive season, resulted in lower figures than would otherwise have been recorded for those months. Binomial standard deviation given by (np(1-p)), where n = number of transient sightings, and p = n/total sessions. Continuity assumed across year ends.

Figure 8.