Submitted:

09 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition, Epidemiology and Burden of Diabetes in Elderly patients with CKD

3. Pathophysiology of CKD in DM among the elderly

4. Diagnosis of CKD in the elderly patients with DM

5. Treatment Considerations

5.1. Non-Pharmaceutical interventions and goals of therapy

5.1.1. Exercise

5.1.2. Dietary Considerations

5.1.3. Blood Pressure, Lipid and Glycemia Control in the Elderly with CKD in DM

| Healthy | Complex | Very Complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics Health Status |

Few coexisting chronic illnesses AND intact cognitive and functional status |

At least 3 coexisting chronic illnesses OR 2+ instrumental ADL impairments OR mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment |

Long Term Care facility resident OR end-stage chronic illnesses OR moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment OR 2+ ADL impairments |

| Rationale | Longer remaining life expectancy | Intermediate remaining life expectancy, high treatment burden, hypoglycemia vulnerability, fall risk | Limited remaining life expectancy makes benefit uncertain |

| HbA1c | <7.0–7.5% (53–58 mmol/mol) |

<8.0% (64 mmol/mol) |

Do not rely on HbA1C; glucose control decisions should be based on avoiding hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia |

| Fasting/pre-prandial glucose | 80–130 mg/dL (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) |

90–150 mg/dL (5.0–8.3 mmol/L) |

100–180 mg/dL (5.6–10.0 mmol/L) |

| Bedtime glucose | 80–180 mg/dL (4.4–10.0 mmol/L) | 100–180 mg/dL (5.6–10.0 mmol/L) |

110–200 mg/dL (6.1–11.1 mmol/L) |

| Blood Pressure | <140/90 mmHg | <140/90 mmHg | <150/90 mmHg |

| Lipid Target | Statin unless contraindicated, or not tolerated |

Statin unless contraindicated, or not tolerated |

Consider likelihood of benefit with statin |

5.2. Pharmaceutical interventions to reduce cardiorenal risk in eldelry patients with CKD in DM

5.2.1. Inhibitors of the Renin Angiotensin System

- Kidney function and potassium level should be checked within 7 to 10 days after initiation

- Up to 30% of eGFR decline may be tolerated.

- Drops in kidney function more than 30%, should prompt investigation for RAS, sepsis, volume depletion or concomitant medications, e.g., NSAIDs

- If an alternative explanation for a marked decline in renal function cannot be inferred, the dose of the RASi may be reduced.

- Potassium binders (Patiromer and Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate) may be used to reduce the serum potassium if it rises over 5 mEq/l and allow the RASi to be continued.

- Combination therapy with ACEi, Direct Renin Inhibitor, and ARBs should not be used since multiple clinical trials have shown greater risks of hypotension, hyperkalemia, and acute renal injury with these combinations [94].

- In advanced (stage 4 and 5) CKD, discontinuation [95] of the RASi was associated with a lower risk for hyperkalemia (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.54-0.79), but higher risk of death (HR, 1.39, 95% CI 1.20 – 1.60), and higher risk of progression to ESKD (HR 1.19, 95% CI: 0.86 – 1.65). The STOP-ACEi [96,97] RCT examined the benefits vs. harm of stopping the RASi in patients with advanced CKD (eGFR was ~18 ml/min/1.73m2 at baseline). There was no difference in the eGFR (primary outcome) at 3 years between participants older than 65 years (- 0.32, 95% CI -2.72 – 2.09 ml/min/1.73m2) and those younger than 65 years (- 0.32, 95%CI -2.92 – 2.28 ml/min/1.73m2). ESKD occurred in 128 patients (62%) among those who discontinued the RASi and in 115 patients (56%) who continued them (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.65). There was a similar number of cardiovascular events (108 vs. 88) and deaths (20 vs. 22) in the two arms.

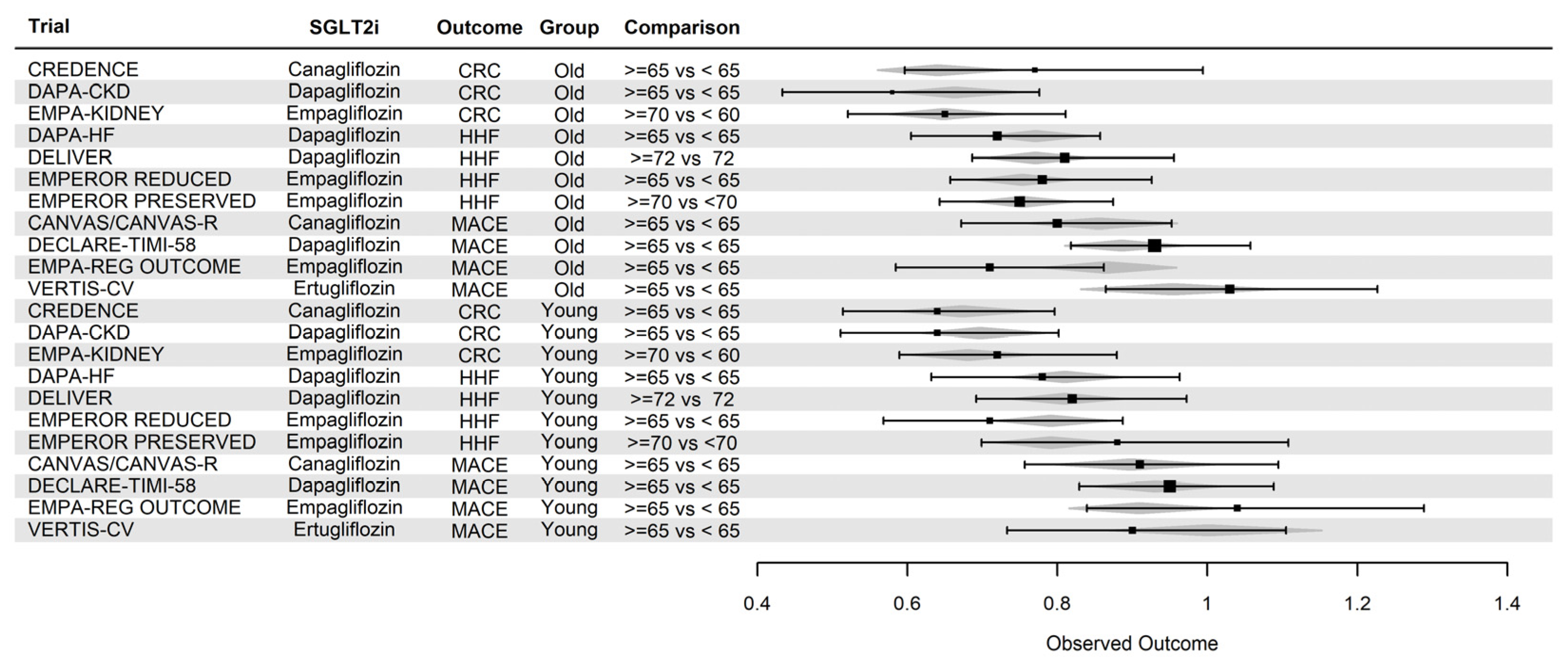

5.2.2. Sodium Glucose Co-transporter two inhibitors

| Adverse Events | Title 2 | At risk |

| Genitourinary Infections | Women, Uncircumcised men |

Adequate perineal hygiene Optimal diabetes care Antifungals Avoid SGLT-2is in patients with history of severe, recurrent infections |

| Diabetic Ketoacidosis | Insulin deficiency, ketogenic diet, alcohol abuse, acute illness, surgery | Maintain insulin; ≤20% reduction in insulin dosage if necessary Discontinue SGLT-2i temporarily in acute illness or surgery Avoid SGLT-2is in patients with history of DKA Discontinue SGLT-2i if patient is not eating or has vomiting and/or diarrhea |

| Acute Kidney Injury | eGFR dip ≥30%, volume depletion | Reassess SGLT-2i regimen Frequently assess renal function, especially in patients with baseline eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 Discontinue SGLT-2i temporarily in acute illness |

| Volume Depletion | eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2, old age, concomitant diuretic, prior volume depletion, hypotension, SBP<110mm Hg | Reduce diuretic or hypotension-inducing agent use Inform patients to maintain adequate oral hydration Discontinue SGLT-2i temporarily in AKI |

| Hypoglycemia | Concomitant insulin or SU, old age | Reduce insulin ≤20% or SU ≤50% if HbA1c<7.0%-8.0% Discontinue SU if HbA1c <8.0% in older patients Gradually reduce SU if HbA1c <8.0% in younger patients |

| Amputation | History of amputation, peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, foot ulcers | Monitor at-risk patients for new pain, skin ulcerations, or infections Inform patients about proper foot care |

| Hyperkalemia | No concern |

5.2.3. Mineralocorticoid antagonists

| Clinical Trial | Outcome | Effect in younger patients | Effect in older patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIGARO-DKD | MACE/HHF2 | 0.90 0.74 – 1.10 |

0.85 0.72 – 1.00 |

| FIGARO-DKD1 | CR3 | 0.72 0.52 – 0.99 |

0.92 0.61-1.38 |

| FIDELIO-DKD | CR | 0.85 0.72 – 1.01 |

0.79 0.67 – 0.94 |

3.2.4. GLP1 and dual GLP1/GIP1 Receptor Agonists

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wild, S.; Roglic, G.; Green, A.; Sicree, R.; King, H. Global Prevalence of Diabetes: Estimates for the Year 2000 and Projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, P.; Caramori, M.L.; Chan, J.C.N.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Hurst, C.; Khunti, K.; Liew, A.; Michos, E.D.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Olowu, W.A.; et al. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International 2022, 102, S1–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkarian, M.; Zelnick, L.R.; Hall, Y.N.; Heagerty, P.J.; Tuttle, K.; Weiss, N.S.; de Boer, I.H. Clinical Manifestations of Kidney Disease Among US Adults With Diabetes, 1988-2014. JAMA 2016, 316, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, J.M. The Emerging Concept of Chronic Kidney Disease without Clinical Proteinuria in Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Metab 2012, 38, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.; McKnight, A.J. The Changing Landscape of Diabetic Kidney Disease: New Reflections on Phenotype, Classification, and Disease Progression to Influence Future Investigative Studies and Therapeutic Trials. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014, 21, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, N.R.; Villa, J.; Gallego, R.H. Non-Proteinuric Diabetic Nephropathy. J Clin Med 2015, 4, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.E. Diabetic Kidney Disease in Elderly Individuals. Med Clin North Am 2013, 97, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, M.; Jorna, T.; Wilkinson, L.; Taylor, J. Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Do They Really Need Referral to the Nephrology Clinic? Clin Kidney J 2017, 10, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Quinn, R.R.; Lam, N.N.; Al-Wahsh, H.; Sood, M.M.; Tangri, N.; Tonelli, M.; Ravani, P. Progression and Regression of Chronic Kidney Disease by Age Among Adults in a Population-Based Cohort in Alberta, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallan, S.I.; Matsushita, K.; Sang, Y.; Mahmoodi, B.K.; Black, C.; Ishani, A.; Kleefstra, N.; Naimark, D.; Roderick, P.; Tonelli, M.; et al. Age and the Association of Kidney Measures with Mortality and End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA 2012, 308, 2349–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.G.; Pavkov, M.E. The Pandemic of Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Kidney News 2020, 12, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. 2020, 32.

- Home; Resources; diabetes, L. with; Acknowledgement; FAQs; Contact; Policy, P. IDF Diabetes Atlas | Tenth Edition.

- Johansen, K.L.; Chertow, G.M.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Herzog, C.A.; Ishani, A.; Israni, A.K.; Ku, E.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; et al. US Renal Data System 2021 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2022, 79, A8–A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.T.; De Cosmo, S.; Viazzi, F.; Mirijello, A.; Ceriello, A.; Guida, P.; Giorda, C.; Cucinotta, D.; Pontremoli, R.; Fioretto, P.; et al. Diabetic Kidney Disease in the Elderly: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates. BMC Geriatr 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K.P.; Morgenstern, H.; Saran, R.; Herman, W.H.; Robinson, B.M. Projecting ESRD Incidence and Prevalence in the United States through 2030. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 30, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.P.; Shardell, M.; Golden, S.H.; Ahima, R.S.; Crews, D.C. Racial/Ethnic Trends in Prevalence of Diabetic Kidney Disease in the United States. Kidney Int Rep 2018, 4, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Medicare & Medical Services, Office of Minority Health Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Diabetes Prevalence, Self-Management, and Health Outcomes among Medicare Beneficiaries; Baltimore, MD, 2017; pp. 1–22;

- Rule, A.D.; Amer, H.; Cornell, L.D.; Taler, S.J.; Cosio, F.G.; Kremers, W.K.; Textor, S.C.; Stegall, M.D. The Association between Age and Nephrosclerosis on Renal Biopsy among Healthy Adults. Ann Intern Med 2010, 152, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tervaert, T.W.C.; Mooyaart, A.L.; Amann, K.; Cohen, A.H.; Cook, H.T.; Drachenberg, C.B.; Ferrario, F.; Fogo, A.B.; Haas, M.; de Heer, E.; et al. Pathologic Classification of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010, 21, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, K.O.; Herzenberg, A.M. Distinguishing Diabetic Nephropathy from Other Causes of Glomerulosclerosis: An Update. J Clin Pathol 2007, 60, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, S.M.; Steffes, M.W.; Ellis, E.N.; Sutherland, D.E.; Brown, D.M.; Goetz, F.C. Structural-Functional Relationships in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Clin Invest 1984, 74, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denic, A.; Lieske, J.C.; Chakkera, H.A.; Poggio, E.D.; Alexander, M.P.; Singh, P.; Kremers, W.K.; Lerman, L.O.; Rule, A.D. The Substantial Loss of Nephrons in Healthy Human Kidneys with Aging. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denic, A.; Mathew, J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lieske, J.C.; Larson, J.J.; Alexander, M.P.; Poggio, E.; Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. Single-Nephron Glomerular Filtration Rate in Healthy Adults. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.; Busque, S.; Workeneh, B.; Ho, B.; Derby, G.; Blouch, K.L.; Sommer, F.G.; Edwards, B.; Myers, B.D. Effects of Aging on Glomerular Function and Number in Living Kidney Donors. Kidney Int 2010, 78, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaih, S.-W.; Pezzolesi, M.G.; Yuan, R.; Warram, J.H.; Krolewski, A.S.; Korstanje, R. Genetic Analysis of Albuminuria in Aging Mice and Concordance with Loci for Human Diabetic Nephropathy Found in a Genome-Wide Association Scan. Kidney Int 2010, 77, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzola, D.; Gandolfo, M.T.; Gaetani, G.; Ferraris, A.; Mangerini, R.; Ferrario, F.; Villaggio, B.; Gianiorio, F.; Tosetti, F.; Weiss, U.; et al. Accelerated Senescence in the Kidneys of Patients with Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2008, 295, F1563–F1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.D. Role of Senescent Renal Cells in Pathophysiology of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Curr Diab Rep 2020, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, M.; Funk, R.H. Age-Related Changes in Cells and Tissues Due to Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs). Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2001, 32, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Zheng, F. Chronic Inflammation Potentiates Kidney Aging. Semin Nephrol 2009, 29, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassara, H.; Torreggiani, M.; Post, J.B.; Zheng, F.; Uribarri, J.; Striker, G.E. Role of Oxidants/Inflammation in Declining Renal Function in Chronic Kidney Disease and Normal Aging. Kidney Int Suppl 2009, S3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassara, H.; Uribarri, J.; Ferrucci, L.; Cai, W.; Torreggiani, M.; Post, J.B.; Zheng, F.; Striker, G.E. Identifying Advanced Glycation End Products as a Major Source of Oxidants in Aging: Implications for the Management and/or Prevention of Reduced Renal Function in Elderly Persons. Semin Nephrol 2009, 29, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhang, W.; Lou, W.; Xia, C.; Han, X.T.; Huang, W.J.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.J. Accelerated Kidney Aging in Diabetes Mellitus. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 1234059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selye, H.; Hall, C.E.; Rowley, E.M. Malignant Hypertension Produced by Treatment with Desoxycorticosterone Acetate and Sodium Chloride. Can Med Assoc J 1943, 49, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, N.S.; Tostes, R.C.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. Aldosterone, Inflammation, Immune System, and Hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2021, 34, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, P.J.; Yang, J.; Young, M.J. 30 YEARS OF THE MINERALOCORTICOID RECEPTOR: Coregulators as Mediators of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Signalling Diversity. J Endocrinol 2017, 234, T23–T34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanami, D.; Takashi, Y.; Muta, Y.; Oda, N.; Nagata, D.; Takahashi, H.; Tanabe, M. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, P.T.; Kaiser, S.; Heinemann, L.; Frenzel, H.; Berger, M. Prevalence of Renal Artery Stenosis in Diabetes Mellitus--an Autopsy Study. J Intern Med 1991, 229, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T.; Omura, K.; Matsubara, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Hayama, K.; Ouchi, M. Arteriolar Hyalinosis Predicts Increase in Albuminuria and GFR Decline in Normo- and Microalbuminuric Japanese Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, E.I.; Jerums, G.; Skene, A.; Crammer, P.; Power, D.; Cheong, K.Y.; Panagiotopoulos, S.; McNeil, K.; Baker, S.T.; Fioretto, P.; et al. Renal Structure in Normoalbuminuric and Albuminuric Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Impaired Renal Function. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 3620–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Furuichi, K.; Yokoyama, H.; Toyama, T.; Iwata, Y.; Sakai, N.; Kaneko, S.; Wada, T. Kidney Lesions in Diabetic Patients with Normoalbuminuric Renal Insufficiency. Clin Exp Nephrol 2014, 18, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Chen, N.; Zeng, L.; Lin, X.-J.; Jiang, F.-X.; Zhuang, X.-J.; Lu, Z.-Y. Clinical Features of and Risk Factors for Normoalbuminuric Diabetic Kidney Disease in Hospitalized Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Endocr Disord 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran, R.; Cull, C.A.; Thorne, K.I.; Adler, A.I.; Holman, R.R.; UKPDS Study Group Risk Factors for Renal Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Ni, L.; Gao, L.; Wu, X. Comparison of Nonalbuminuric and Albuminuric Diabetic Kidney Disease Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 871272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Quinn, R.R.; Lam, N.N.; Elliott, M.J.; Xu, Y.; James, M.T.; Manns, B.; Ravani, P. Accounting for Age in the Definition of Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Internal Medicine 2021, 181, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanaye, P.; Jager, K.J.; Bökenkamp, A.; Christensson, A.; Dubourg, L.; Eriksen, B.O.; Gaillard, F.; Gambaro, G.; van der Giet, M.; Glassock, R.J.; et al. CKD: A Call for an Age-Adapted Definition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019, 30, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zeeuw, D.; Parving, H.-H.; Henning, R.H. Microalbuminuria as an Early Marker for Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 17, 2100–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Henry, R.M.A.; Dekker, J.M.; Nijpels, G.; Heine, R.J.; Bouter, L.M. Microalbuminuria Is Associated with Impaired Brachial Artery, Flow-Mediated Vasodilation in Elderly Individuals without and with Diabetes: Further Evidence for a Link between Microalbuminuria and Endothelial Dysfunction--the Hoorn Study. Kidney Int Suppl 2004, S42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, K.; Park, J.; Kim, D.H.; Jeon, J.; Jang, H.R.; Hur, K.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Huh, W.; Kim, Y.-G.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Albuminuria in Elderly of Various Ages with Diabetes. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H.-J.; Huber, T.B.; Isermann, B.; Schiffer, M. CKD in Diabetes: Diabetic Kidney Disease versus Nondiabetic Kidney Disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018, 14, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Meguira, S.; Friedman, E.A. Geriatric Diabetic Nephropathy: An Analysis of Renal Referral in Patients Age 60 or Older. Am J Kidney Dis 1990, 16, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.M.; Alberti, K.G. Comparison of the Prevalence and Associated Features of Abnormal Albumin Excretion in Insulin-Dependent and Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes. Q J Med 1989, 70, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Parving, H.H.; Gall, M.A.; Skøtt, P.; Jørgensen, H.E.; Løkkegaard, H.; Jørgensen, F.; Nielsen, B.; Larsen, S. Prevalence and Causes of Albuminuria in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients. Kidney Int 1992, 41, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torffvit, O.; Agardh, E.; Agardh, C.D. Albuminuria and Associated Medical Risk Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study in 476 Type I (Insulin-Dependent) Diabetic Patients. Part 1. J Diabet Complications 1991, 5, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.J.; Friedman, E.A. Diabetic Nephropathy in the Elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 2009, 25, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.; Bell, J.M.; Walker, P.D. Renal Biopsy in Patients Aged 80 Years and Older. Am J Kidney Dis 2004, 44, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedi, M.; Bobot, M.; Torrents, J.; Gobert, P.; Magnant, É.; Knefati, Y.; Verhelst, D.; Lebrun, G.; Masson, V.; Giaime, P.; et al. Kidney Biopsy in Very Elderly Patients: Indications, Therapeutic Impact and Complications. BMC Nephrol 2021, 22, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, H.S.; Jairam, A.; Bhat, A.; Sud, K.; Jha, V.; Gupta, K.L.; Sakhuja, V. Safety of Kidney Biopsy in Elderly: A Prospective Study. Int Urol Nephrol 2006, 38, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uezono, S.; Hara, S.; Sato, Y.; Komatsu, H.; Ikeda, N.; Shimao, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Asada, Y.; Fujimoto, S.; Eto, T. Renal Biopsy in Elderly Patients: A Clinicopathological Analysis. Ren Fail 2006, 28, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicklé, J.F.; Doucet, J.; Krummel, T.; Hannedouche, T. Diabetic Nephropathy in the Elderly. Diabetes Metab 2007, 33 Suppl 1, S40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinel, E.; Agraz, I.; Ibernon, M.; Ramos, N.; Fort, J.; Serón, D. Renal Biopsy in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J Clin Med 2015, 4, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, M.; Bolignano, D.; Tesar, V.; Pisano, A.; Biesen, W.V.; Tripepi, G.; D’Arrigo, G.; Gesualdo, L. ; ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group Renal Biopsy in Patients with Diabetes: A Pooled Meta-Analysis of 48 Studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017, 32, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassock, R.J.; Hirschman, G.H.; Striker, G.E. Workshop on the Use of Renal Biopsy in Research on Diabetic Nephropathy: A Summary Report. Am J Kidney Dis 1991, 18, 589–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, B.; Beuscart, J.-B.; Frimat, L. Competing-Risk Analysis of Death and Dialysis Initiation among Elderly (≥80 Years) Newly Referred to Nephrologists: A French Prospective Study. BMC Nephrol 2013, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Wong, L.; St Peter, W.; Roberts, G.; Rangaswami, J.; Mottl, A.; Kliger, A.S.; Harris, R.C.; Gee, P.O.; Fowler, K.; et al. Moving from Evidence to Implementation of Breakthrough Therapies for Diabetic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022, 17, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierre, D.; Ribeiro, P.A.B.; Kramer, C.K.; Leitão, C.B.; Zucatti, A.T.N.; Azevedo, M.J.; Gross, J.L.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Schaan, B.D. Physical Activity Advice Only or Structured Exercise Training and Association with HbA1c Levels in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Maher, C.G.; Briffa, T.; Sherrington, C.; Bennell, K.; Alison, J.; Singh, M.F.; Glasziou, P.P. Prescribing Exercise Interventions for Patients with Chronic Conditions. CMAJ 2016, 188, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L.; Sinclair, A.J. Editorial: What Is New in Exercise Regimes for Frail Older People - How Does the Erasmus Vivifrail Project Take Us Forward? J Nutr Health Aging 2016, 20, 736–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, C.; Aida, R.; Tanaka, S.; Kamada, C.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshimura, Y.; Kodera, R.; Fujihara, K.; Kawasaki, R.; Moriya, T.; et al. Sodium Intake and Incidence of Diabetes Complications in Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes-Analysis of Data from the Japanese Elderly Diabetes Intervention Study (J-EDIT). Nutrients 2021, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klahr, S.; Levey, A.S.; Beck, G.J.; Caggiula, A.W.; Hunsicker, L.; Kusek, J.W.; Striker, G. The Effects of Dietary Protein Restriction and Blood-Pressure Control on the Progression of Chronic Renal Disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994, 330, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijls, L.T.J.; de Vries, H.; van Eijk, J.T.M.; Donker, A.J.M. Protein Restriction, Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002, 56, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Clinical Nutrition and Hydration in Geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G.B.; Cederholm, T.; Avesani, C.M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Bellizzi, V.; Cuerda, C.; Cupisti, A.; Sabatino, A.; Schneider, S.; Torreggiani, M.; et al. Nutritional Status and the Risk of Malnutrition in Older Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease – Implications for Low Protein Intake and Nutritional Care: A Critical Review Endorsed by ERN-ERA and ESPEN. Clinical Nutrition 2023, 42, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; Draznin, B.; Aroda, V.R.; Bakris, G.; Benson, G.; Brown, F.M.; Freeman, R.; Green, J.; Huang, E.; Isaacs, D.; et al. 13. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S195–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.E. Glucose Control in Type 2 Diabetes: Still Worthwhile and Worth Pursuing. JAMA 2009, 301, 1590–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorr, R.I.; Franse, L.V.; Resnick, H.E.; Di Bari, M.; Johnson, K.C.; Pahor, M. Glycemic Control of Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000, 48, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmer, R.A.; Karter, A.J.; Yaffe, K.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Selby, J.V. Hypoglycemic Episodes and Risk of Dementia in Older Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA 2009, 301, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of Intensive Blood-Glucose Control with Metformin on Complications in Overweight Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998, 352, 854–865. [CrossRef]

- Intensive Blood-Glucose Control with Sulphonylureas or Insulin Compared with Conventional Treatment and Risk of Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet 1998, 352, 837–853. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.K.; Chang, T.I.; Cushman, W.C.; Furth, S.L.; Hou, F.F.; Ix, J.H.; Knoll, G.A.; Muntner, P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Sarnak, M.J.; et al. Executive Summary of the KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International 2021, 99, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.S.R. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 373, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, B.; Marston, N.A.; Im, K.; Cannon, C.P.; Sever, P.; Keech, A.; Braunwald, E.; Giugliano, R.P.; Sabatine, M.S. Efficacy and Safety of Lowering LDL Cholesterol in Older Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yourman, L.C.; Cenzer, I.S.; Boscardin, W.J.; Nguyen, B.T.; Smith, A.K.; Schonberg, M.A.; Schoenborn, N.L.; Widera, E.W.; Orkaby, A.; Rodriguez, A.; et al. Evaluation of Time to Benefit of Statins for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Adults Aged 50 to 75 Years: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2021, 181, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2021, 99, S1–S87. [CrossRef]

- Baigent, C.; Landray, M.J.; Reith, C.; Emberson, J.; Wheeler, D.C.; Tomson, C.; Wanner, C.; Krane, V.; Cass, A.; Craig, J.; et al. The Effects of Lowering LDL Cholesterol with Simvastatin plus Ezetimibe in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.J.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Clarke, W.R.; Berl, T.; Pohl, M.A.; Lewis, J.B.; Ritz, E.; Atkins, R.C.; Rohde, R.; Raz, I.; et al. Renoprotective Effect of the Angiotensin-Receptor Antagonist Irbesartan in Patients with Nephropathy Due to Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Keane, W.F.; Mitch, W.E.; Parving, H.H.; Remuzzi, G.; Snapinn, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S.; et al. Effects of Losartan on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers Heerspink, H.J.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; Parving, H.H.; Shahinfar, S.; de Zeeuw, D. Comparison of Different Measures of Urinary Protein Excretion for Prediction of Renal Events. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010, 21, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, D.; Remuzzi, G.; Parving, H.-H.; Keane, W.F.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S.; Snapinn, S.; Cooper, M.E.; Mitch, W.E.; Brenner, B.M. Proteinuria, a Target for Renoprotection in Patients with Type 2 Diabetic Nephropathy: Lessons from RENAAL. Kidney Int 2004, 65, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.F.; Petruski-Ivleva, N.; Folkerts, K.; Schmedt, N.; Velentgas, P.; Kovesdy, C.P. ACE Inhibitor or ARB Treatment among Patients with Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Manag Care 2021, 27, S360–S368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Thumula, V.; Pace, P.F.; Banahan, B.F.; Wilkin, N.E.; Lobb, W.B. High-Risk Diabetic Patients in Medicare Part D Programs: Are They Getting the Recommended ACEI/ARB Therapy? J Gen Intern Med 2010, 25, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.B.; Karter, A.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Selby, J.V.; Schneider, E.C. Use of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in High-Risk Clinical and Ethnic Groups with Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 2004, 19, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Winocour, P.; Chowdhury, T.A.; De, P.; Wahba, M.; Montero, R.; Fogarty, D.; Frankel, A.H.; Karalliedde, J.; Mark, P.B.; et al. Management of Hypertension and Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Blockade in Adults with Diabetic Kidney Disease: Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and the Renal Association UK Guideline Update 2021. BMC Nephrol 2022, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.F.; Emanuele, N.; Zhang, J.H.; Brophy, M.; Conner, T.A.; Duckworth, W.; Leehey, D.J.; McCullough, P.A.; O’Connor, T.; Palevsky, P.M.; et al. Combined Angiotensin Inhibition for the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013, 369, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Shin, J.-I.; Chen, T.K.; Inker, L.A.; Coresh, J.; Alexander, G.C.; Jackson, J.W.; Chang, A.R.; Grams, M.E. Association Between Renin-Angiotensin System Blockade Discontinuation and All-Cause Mortality Among Persons With Low Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate. JAMA Intern Med 2020, 180, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Ives, N.; Brettell, E.A.; Valente, M.; Cockwell, P.; Topham, P.S.; Cleland, J.G.; Khwaja, A.; El Nahas, M. Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Withdrawal in Advanced Renal Disease: The STOP-ACEi Trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016, 31, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Mehta, S.; Khwaja, A.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Ives, N.; Brettell, E.; Chadburn, M.; Cockwell, P. ; STOP ACEi Trial Investigators Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 2021–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapas, A.; Karagiannis, T.; Avgerinos, I.; Matthews, D.R.; Bekiari, E. Comparative Effectiveness of Glucose-Lowering Drugs for Type 2 Diabetes. Ann Intern Med 2021, 174, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, D.Z.I.; Charbonnel, B.; Cosentino, F.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; McGuire, D.K.; Pratley, R.; Shih, W.J.; Frederich, R.; Maldonado, M.; Pong, A.; et al. Effects of Ertugliflozin on Kidney Composite Outcomes, Renal Function and Albuminuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis from the Randomised VERTIS CV Trial. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1256–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, C.C.J.; Wheeler, D.C.; Sjöström, C.D.; Stefansson, B.V.; Cain, V.; Heerspink, H.J.L. Effects of the Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Stages 3b-4 Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018, 33, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, C.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; von Eynatten, M.; Mattheus, M.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; Broedl, U.C.; Zinman, B.; et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Pratley, R.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Mancuso, J.; Huyck, S.; Masiukiewicz, U.; Charbonnel, B.; Frederich, R.; Gallo, S.; Cosentino, F.; et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes with Ertugliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Matthews, D.R. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.-P.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Jardine, M.J.; Neal, B.; Bompoint, S.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Edwards, R.; Agarwal, R.; Bakris, G.; Bull, S.; et al. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.-F.; Mann, J.F.E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lindberg, M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group; Herrington, W.G.; Staplin, N.; Wanner, C.; Green, J.B.; Hauske, S.J.; Emberson, J.R.; Preiss, D.; Judge, P.; Mayne, K.J.; et al. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, E.J.M.; Muskiet, M.H.A.; van Baar, M.J.B.; Tonneijck, L.; Smits, M.M.; Emanuel, A.L.; Bozovic, A.; Danser, A.H.J.; Geurts, F.; Hoorn, E.J.; et al. The Renal Hemodynamic Effects of the SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin Are Caused by Post-Glomerular Vasodilatation Rather than Pre-Glomerular Vasoconstriction in Metformin-Treated Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in the Randomized, Double-Blind RED Trial. Kidney Int 2020, 97, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Clinical Implications of an Acute Dip in eGFR after SGLT2 Inhibitor Initiation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 16, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, B.J.; Weir, M.R.; Bakris, G.L.; Mattheus, M.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Sattar, N.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Ritter, I.; von Eynatten, M.; Zinman, B.; et al. Characterization and Implications of the Initial Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate “dip” upon Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibition with Empagliflozin in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Kidney Int 2021, 99, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, M.E.; Argyropoulos, C. The Cardiovascular Outcomes, Heart Failure and Kidney Disease Trials Tell That the Time to Use Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors Is Now. Clin Cardiol 2020, 43, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, M.; Salih, M.; Regmi, M.; Al-Akchar, M.; Deshpande, R.; Niaz, Z.; Kulkarni, A.; Siddique, M.; Hegde, S. Association of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors With Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Other Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2142078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, W.D.; Griffiths, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and SGLT-2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Biologically Healthy Older Adults. British Journal of Diabetes 2021, 21, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuffield Department of Population Health Renal Studies Group; SGLT2 inhibitor Meta-Analysis Cardio-Renal Trialists’ Consortium Impact of Diabetes on the Effects of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors on Kidney Outcomes: Collaborative Meta-Analysis of Large Placebo-Controlled Trials. Lancet 2022, 400, 1788–1801. [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, S.A.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Argyropoulos, C.P. Physicians’ Considerations and Practice Recommendations Regarding the Use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.Y.; Ruospo, M.; Natale, P.; Bolignano, D.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Palmer, S.C.; Strippoli, G.F. Aldosterone Antagonists in Addition to Renin Angiotensin System Antagonists for Preventing the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020, 2020, CD007004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Chimal, J.; Kolkhof, P.; Lima-Posada, I.; Joachim, A.; Rossignol, P.; Jaisser, F. Differentiation between Emerging Non-Steroidal and Established Steroidal Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists: Head-to-Head Comparisons of Pharmacological and Clinical Characteristics. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021, 30, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Kashihara, N.; Shikata, K.; Nangaku, M.; Wada, T.; Okuda, Y.; Sawanobori, T. Esaxerenone (CS-3150) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria (ESAX-DN): Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. CJASN 2020, 15, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Inagaki, M.; Yoshinari, T.; Terata, R.; Totsuka, N.; Gotou, M.; Hashimoto, G. Apararenone in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Dose-Response Study and Open-Label Extension Study. Clin Exp Nephrol 2021, 25, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; Joseph, A.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Filippatos, G.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; et al. Cardiovascular Events with Finerenone in Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 2252–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Filippatos, G.; Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Rossing, P.; Joseph, A.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Gebel, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes with Finerenone in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: The FIDELITY Pooled Analysis. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Pitt, B.; Anker, S.D.; Rossing, P.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Pergola, P.; Joseph, A.; Lage, A.; Mentenich, N.; et al. Kidney Outcomes with Finerenone: An Analysis from the FIGARO-DKD Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, gfac157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prato, S.; Kahn, S.E.; Pavo, I.; Weerakkody, G.J.; Yang, Z.; Doupis, J.; Aizenberg, D.; Wynne, A.G.; Riesmeyer, J.S.; Heine, R.J.; et al. Tirzepatide versus Insulin Glargine in Type 2 Diabetes and Increased Cardiovascular Risk (SURPASS-4): A Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Multicentre, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Pérez Manghi, F.C.; Fernández Landó, L.; Bergman, B.K.; Liu, B.; Cui, X.; Brown, K. ; SURPASS-2 Investigators Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; Bain, S.C. The Role of Tirzepatide, Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist, in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes: The SURPASS Clinical Trials. Diabetes Ther 2021, 12, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, J.; Wysham, C.; Frías, J.P.; Kaneko, S.; Lee, C.J.; Fernández Landó, L.; Mao, H.; Cui, X.; Karanikas, C.A.; Thieu, V.T. Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Dual GIP and GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Tirzepatide in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-1): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes 2022, 40, 10–38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, W.D.; Griffiths, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and SGLT-2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Biologically Healthy Older Adults. British Journal of Diabetes 2021, 21, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Botros, F.T.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: An Exploratory Analysis of the REWIND Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Sattar, N.; Pavo, I.; Haupt, A.; Duffin, K.L.; Yang, Z.; Wiese, R.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Effects of Tirzepatide versus Insulin Glargine on Kidney Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes in the SURPASS-4 Trial: Post-Hoc Analysis of an Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2022, 10, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Ørsted, D.D.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Marso, S.P.; Poulter, N.R.; Rasmussen, S.; Tornøe, K.; Zinman, B.; Buse, J.B. LEADER Steering Committee and Investigators Liraglutide and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jódar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.H.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, Mortality, and Kidney Outcomes with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, H.C.; Colhoun, H.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Diaz, R.; Lakshmanan, M.; Pais, P.; Probstfield, J.; Botros, F.T.; Riddle, M.C.; Rydén, L.; et al. Dulaglutide and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: An Exploratory Analysis of the REWIND Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. The Lancet 2019, 394, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glomerulus | Arterioles | Mesangium2 | Tubulo-interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse Intra-capillary Glomerulosclerosis |

Subintimal Hyaline Deposits |

Mesangial Matrix Expansion |

Tubular Atrophy / Interstitial Space Expansion |

| Nodular (Kimmelstein Wilson) |

Capillary Walls Bowman Capsules (capsular drops) 1 |

Mesangiolysis |

Tubular Basement Membrane Thickening |

| Glomerulosclerosis | Mesangial CellProliferation | Interstitial Fibrosis | |

| Features On Presentation | Features Developing on Presentation or Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Absence of Retinopathy | Rapid Decline in eGFR (> 5ml/min/1.73m2) |

| Albuminuria < 5 years or > 25 years after diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes |

↓ eGFR by more than 30% after initiation of an Inhibitor of the Renin Angiotensin System |

| Active Urine Sediment or Serologies | Acute Kidney Injury |

| Hematuria/Nephritic Syndrome | Sudden/acute worsening of albuminuria |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).