1. Introduction

Each year, the effect of climate change on the planet becomes more evident. Different areas around the world have been affected by more extreme temperatures, droughts, flooding and other problems. These problems have been exacerbated by a misguided approach to water resource management; this approach is driven by the consideration of water more as an economic good than as an essential resource for the existence of life, according to [

1]. These environmental problems cause considerable difficulties in industries that require a fixed and constant supply of water throughout the year, and that cannot be suspended as they contribute to public well-being in various ways, such as by providing employment opportunities, food production, or contributions to a country’s GDP.

Mining is one example of these industries as mining operations work constantly, day and night, every day of the year. Due to this demanding pace, the supply of water is a fixed cost, rather than a variable cost, during the life of the mine. Furthermore, since mining typically takes place in inhospitable areas, it must often deal with water scarcity while also avoiding an excess of water in the operating area [

2]. Hydrological studies are therefore carried out by mining companies in order to establish the water balance and ensure the availability of the resource. However, since these studies do not consider social and environmental factors beyond those indicated in water codes, there is often a divergence between what companies are authorized to extract and what it is prudent to extract [

2].

As the mining industry has relied on the availability of water in the areas where its operations are located, many operations have been negatively affected by the long-term use of surface and groundwater [

3]. This limitation on the use of water, together with the growing need to involve communities in water management to ensure local benefits, has opened the industry to search for solutions to counteract water scarcity, such as reuse, usage of lower volumes of water, or address water issues at catchment scale [

4].

1.1. Hydrological impacts of large-scale mining

In certain areas, mining activity can significantly affect the demand for water. This is often the case in remote regions with low population densities, where mining represents the primary economic activity. The resulting increase in water demand is a significant factor in the environmental impact on local hydrological basins, as it can exceed the ecological flow of the region by up to 46 times [

5]. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that excess mine water discharge in some areas can lead to floods and tailings dam breaches [

6,

7]. These are just two examples of the diverse risks that nearby communities face due to large-scale mining operations.

Typically, the hydrological impact in mining areas is gauged by measuring the level of contamination and the comparison of the available water flow versus the water flow demanded by the sector in an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study. As part of the assessment, actions are proposed to compensate, mitigate, and control the affected environment. Although regulations require mining companies to carry out the assessment, in Chile and other countries, companies are not obliged to comply with the promised actions that would protect the environment due to a lack of regulation and supervision [

8].

1.2. Social License to Operate and Participative Engagement

The Social License to Operate (SLO) can be defined as an intangible agreement between the shareholders of an organization and communities, in which the latter grants their approval to carry out a certain project [

9]. Consequently, it is often said that the license must be earned and prioritized to maintain its status over time [

10]. Although it has been found that gaining an SLO has come to present less of a challenge to the mining industry in recent years, it still ranks third among the top 10 challenges that the mining industry must face [

11], indicating its importance for the industry.

One of the relevant practices for obtaining an SLO is engagement with external stakeholders, which mining companies can develop through meetings with nearby communities that often comprise Indigenous communities. These meetings aim to communicate project characteristics and collect concerns that communities may have. The primary purpose of this relationship building is to obtain the Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the communities and establish a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) among the parties involved. However, the main challenge in establishing such relationships is that mining companies typically focus primarily on obtaining FPIC rather than establishing meaningful and cooperative meetings with communities [

12]. Previous studies have shown that conducting participatory engagement with a multidimensional consideration of nearby communities can improve the social performance of mining companies [

12,

13,

14].

1.3. Rights of water usage in Chile

In Chile, water is a resource that can be granted through a right to use it. These rights are usually expressed in units of volume per unit of time, allowing individuals to decide and utilize this flow according to their convenience or industry [

15,

16,

17]. The water rights have two classifications, based on their consumption or the location of the water. The first classification includes consumptive or non-consumptive rights. In consumptive rights, the beneficiary of the right can fully consume the resource, whereas in non-consumptive rights, the resource must be returned to its natural flow. In addition, water rights are classified as surface or groundwater. Surface sources are those water sources that appear on the earth’s surface, such as rivers, lakes, lagoons, or reservoirs, while groundwater sources are those hidden below the earth’s surface [

15].

According to the Water Atlas conducted by the Chilean General Water Directorate (DGA) [

15], as of August 2015, 52,581 water rights have been granted, of which 81.7% are consumptive and 18.3% are non-consumptive. Within this, the flow of groundwater delivered to the same date corresponds to 467.3 cubic meters per second, while that of surface water amounts to 40,007.71 cubic meters per second. The majority of granted surface water rights correspond to non-consumptive types whereas groundwater rights are mostly consumptive and definitive [

15]. As a result of this legislation, in regions of Chile where mining is the primary economic activity, the majority of water rights are allocated to mining companies, which can leave other stakeholders with limited access to water and make it challenging to implement holistic approaches.

In summary, in Chile (and, it can be expected, in other countries), the integration of environmental and social factors in hydrological basins where mining projects are developed has not been considered as an important part of creating strategies to optimize the use of freshwater. The mining industry needs to reduce its hydrological impact [

2] and enhance its social acceptability by integrating the perceptions of previously marginalized communities into the development of more appropriate water-use strategies. Therefore, a strategic guideline is proposed to integrate the social and environmental assessment of local basins into the planning of water resource use, based on social perceptions and formal hydrological parameters of these basins. The aim of this study is to analyze the applicability of proposed strategies from the perspective of different agents who utilize the water resource, in order to integrate environmental and social factors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Method

In this study, a qualitative approach was adopted to understand the perspectives of different actors in social and environmental dimensions. Initially, a focus group was conducted by interviewing four representatives selected according to the distribution of water rights in the basin. The findings from these semi-structured interviews were then taken into account for the design of questions and answer options for a survey that was then administered to members of the general population. With this second instrument, the aim was to understand the perspective of the population regarding specific strategies identified by focus group participants [

18,

19,

20].

2.2. Study Location

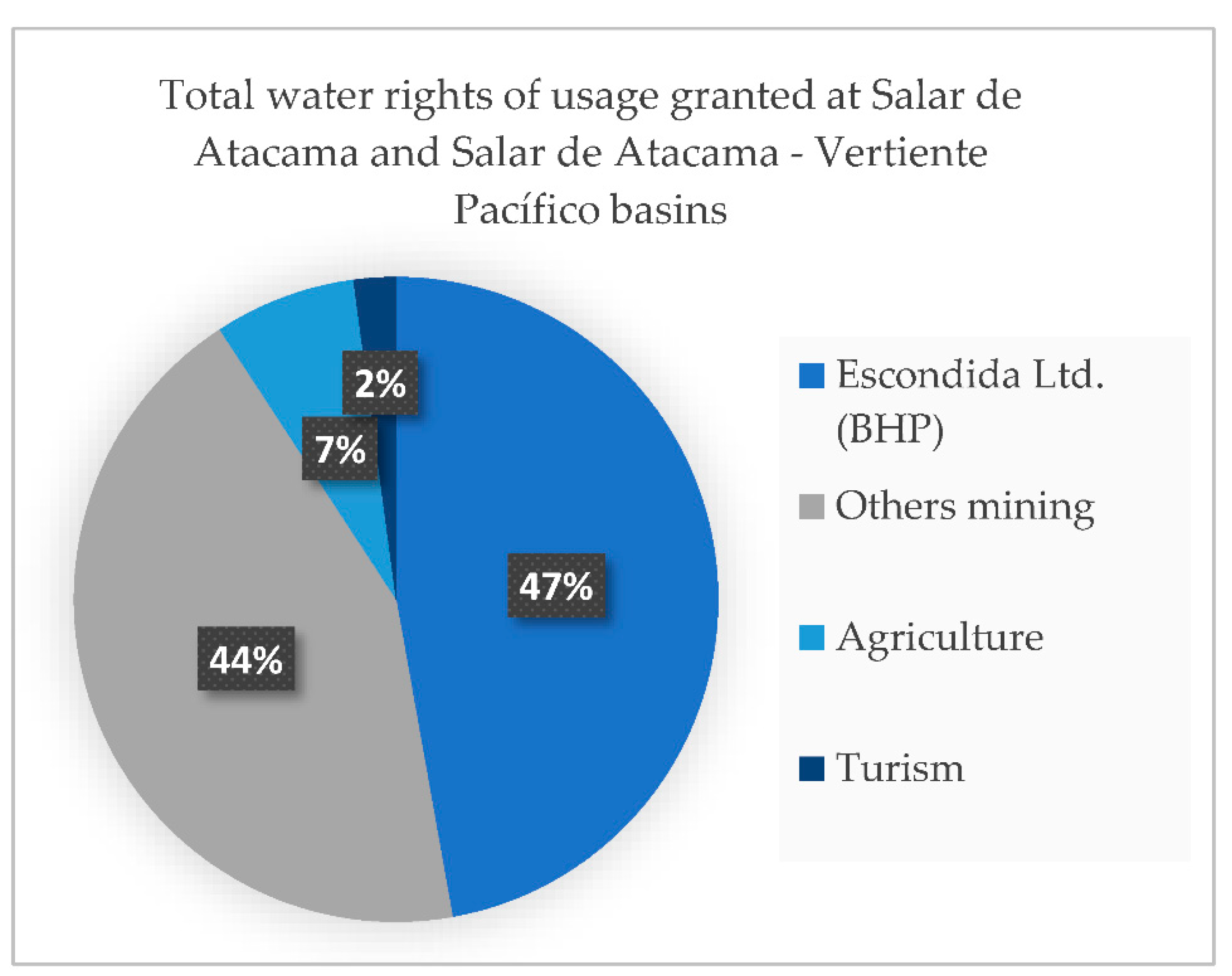

The Salar de Atacama and Salar de Atacama-Vertiente Pacífico basins are located in the Antofagasta region, Chile. They are limited by the Domeyko mountain range and other endorheic basins on the border with Argentina and Bolivia. In their surroundings, communities, mainly indigenous, coexist whose development depends on the water available in the rivers that originate from the Atacama and Punta Negra salt flats. The importance of these basins lies in that their water flow is the main source of this resource in delicate ecosystems under extreme conditions, such as hypersaline lagoons [

21]. Currently, four mining companies hold the largest amount of water extraction rights in this area.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of total water rights, including consumptive and non-consumptive rights, in the study area.

2.3. Population

Through the review of water rights granted in the basins, it was found that most of these rights were granted to private mining companies, while the second largest proportion corresponds to rights granted to state-owned mining companies. Therefore, the focus group comprised a mining engineer in a managerial position at a state-owned mining company, two mining engineers in high-level positions at private mining companies, and a local resident. The age of the focus group participants ranged from 30 to 40 years old. All the mining-related interviewees had pursued graduate studies, while the local resident held an undergraduate degree in a field other than mining.

After the initial instrument was applied, a survey was conducted online using a non-probabilistic sampling method. The survey was distributed freely on professional social media platforms such as LinkedIn. A total of 156 individuals from the central-north region of Chile voluntarily participated, representing a wide age range of 20 to 55 years and varying levels of education.

2.4. Instruments

The instruments used in this study primarily consisted of a semi-structured interview and a survey. The semi-structured interview was used with the focus group to identify key strategies and approaches for water resource management in the social and environmental dimensions of the study area. The survey was used to understand the general population’s perception of the identified strategies and approaches to address the problem. It consisted of closed-ended questions with response options generated from the textual data of the interviewees. Both instruments had three sections aimed at finding out about the level of understanding, potential proposals, and the risks and disadvantages associated with the proposed strategies. The complete instruments can be found in

Appendix A and

Appendix B.

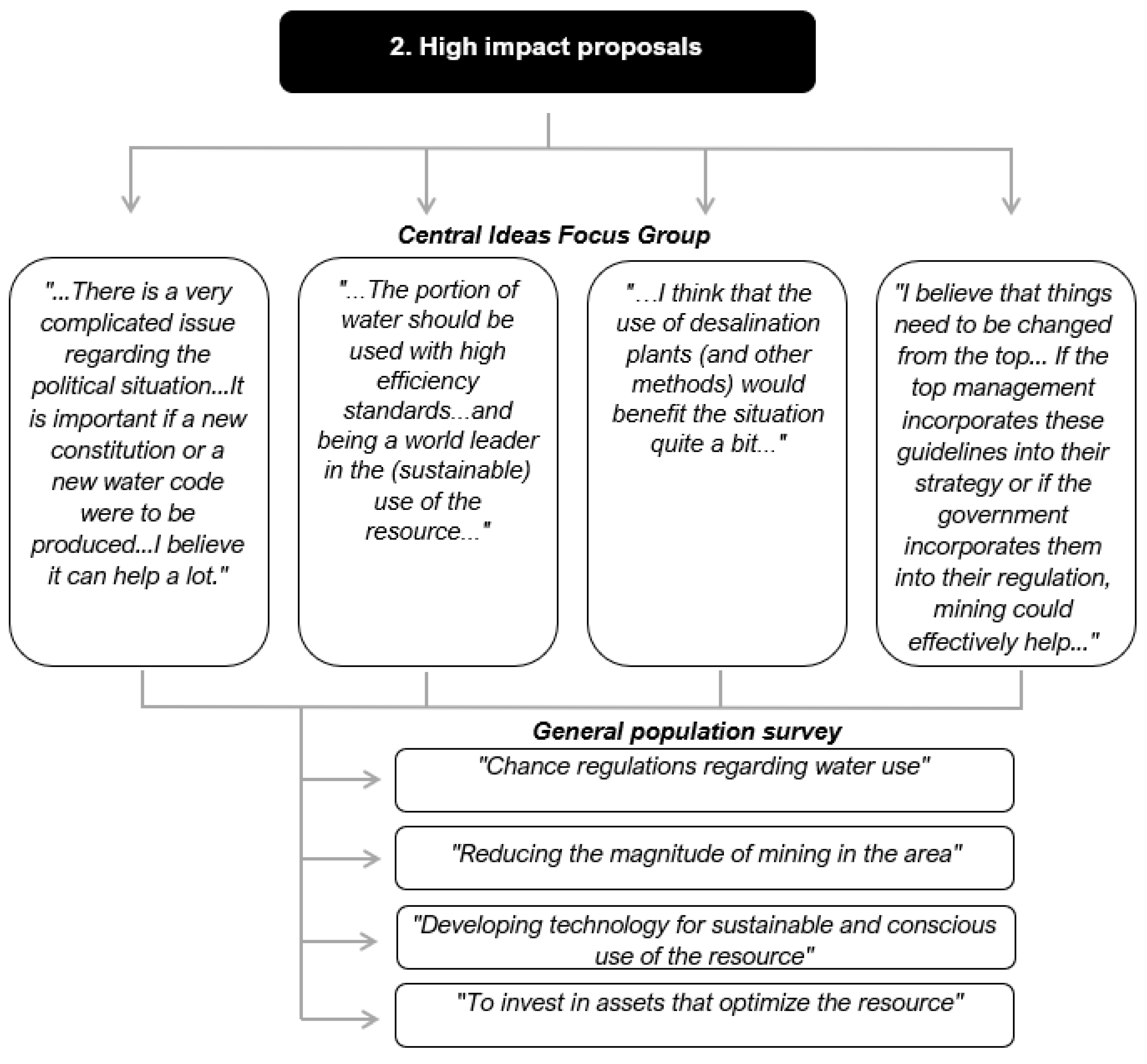

2.5. Development of the survey

Initially, the responses to the interviews were considered as entry perceptions to derive contextualized questions for the survey instrument. From this first exercise, the central ideas expressed by each interviewee, specifically from sections 2 and 3, were taken to obtain the main proposed strategies, which were grouped according to similarity. This process is illustrated in

Figure 2.

These generalities were subsequently taken as alternatives for the survey. The “prefer not to answer” option was included for all questions in order to prevent respondents from feeling obliged to choose any of the previous options. The validation of the qualitative analysis was carried out through consultation with two experts in water management and resource management areas, respectively.

2.6. Ethical considerations

Following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 [

22], the four interviewees in this study freely provided informed consent. The informed consent form outlined the possible risks of participating in this activity, clarified that the questions were intended solely to gather their opinions on the use of water resources for research purposes, and guaranteed the protection, privacy, and anonymization of their personal data, such as age or education level. Since the interviews aimed to obtain their professional assessments and insights on a topic within the industry they are involved in, this activity is exempt from Ethics Board Review according to Chilean laws and international standards [

23,

24,

25].

In addition, the surveyed population also willingly provided informed consent, which stated that the protection, privacy, and anonymization of their personal data, such as their current region of residence or age, are ensured. The informed consent also explained the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. Since the researchers had no direct interaction with the surveyed population, this activity is also exempt from the Ethics Board Review.

It is declared that the present study has no conflicts of interest and has not been funded by any of the companies present in the area.

3. Results

The following section presents the results collected from the application of the research instruments. In order to avoid unnecessarily lengthening the text, only the most relevant questions are analyzed.

3.1. Characterization and understanding of the current situation

The majority of participants in the focus group agreed with the notion that the mining industry ought to seek new alternatives for the utilization of water resources. This sentiment was conveyed through various opinions given by the participants, such as “Let’s start with the fact that industrial activity will always use water... now, in the current reality... the use of water by mining should be optimized and minimized from natural sources... ensuring that other participants have access to the resource” (Interviewee 1) and “I believe we are in a critical state with fresh water... I think the industry should explore alternative ways to obtain water” (Interviewee 2). One of the participants mentioned poor management as a problem: “I believe that the management has not been very good... since we have had many protests because during the summer, several water cuts occurred and the water was cut off for more than a week” (Interviewed 4). This opinion was widely accepted by the surveyed population (n=156), of whom 66% considered that the management of the water resource is carried out in a “very bad” or “bad” way.

Regarding the water management, when the focus group participants were asked to identify main deficiencies and their causes, their responses varied and they mentioned “poor communication among the agents who use the resource”; “every agent is seeking their own interests”; and “mining operations should be scaled down”. In comparison, 73.1% of the surveyed population considered that the main cause of poor management was that “every agent is seeking their own interests”.

Finally, when asked who were the key agents or factors to faciliate taking the population’s perceptions into account, two members of the focus group indicated that the main agent corresponds to “Mining executives”, while one considered that it should be “Legal factors”. However, 44.9% of the surveyed individuals considered that the most relevant agent is “Shareholders of mining companies”.

3.2. High impact proposals

Concerning the high-impact and short-term strategies that the mining industry should adopt, the four participants of the focus group proposed different alternatives, but they agreed that these guidelines should come from an agent with power over management. This stance was expressed through statements such as:

“The political situation is complicated… If a new constitution1 or a new water code were to be produced, I believe it could help a lot” (Interviewee 2), and

“I believe that things need to be changed from the top... If the top management incorporates these guidelines into their strategy or if the government incorporates them into their regulation, mining could effectively help” (Interviewee 1). Amongst the survey respondents, there was more variation with regard to which strategy was considered to be most important. 34% of the population responded that the best strategy would be to

“Invest in assets that optimize the resource”; 32.7% responded that it was

“Developing technology for sustainable and conscious use of the resource”; and 29.5% responded that the

“Regulations regarding water use” should be changed.

In relation to the proposed change to create agreements between companies and communities, all interviewees commented that it should be feasible or “work”. For instance, one commented that “I think that’s how it should ideally be... These types of proposals allow both parties to create a positive environment for future dialogues” (Interviewee 3). However, they each pereceived different constraints for this plan, for example, mentioning that “The main disadvantage I see is the time it may take to reach a feasible agreement” (Interviewee 3) and “I’m not so clear how effective it could be though...One disadvantage could be that the conflict between the parties gets worse.” (Interviewee 1). In the survey, these concerns were also reflected. 39.7% of the respondents considered that “It would work with conditions”, while 21.8% agreed that “Yes, I think it would work” and 21.2% held that “It would work, but it would take a lot of time”.

3.3. Analysis of the new strategies

Regarding the threats and opportunities for the strategies proposed in previous section, each member of the focus group expressed a different analysis. These ranged from opinions such as “I do not believe that there are risks or threats to people or jobs. On the contrary, I believe it is an opportunity” (Interviewee 2) to “[There could be] difficulty in meeting production or economic goals which could make the project unfeasible... I believe that government assistance is needed to transform the industry culturally” (Interviewee 3). In the survey, participants were asked to choose between “Project unfeasibility”; “Availability of job opportunities”; “Damage to the mining industry’s image”; “That it may be too late to renew the (water) resource” or “Do not consider there to be a threat, as it is an opportunity”. The responses were mainly in two distinct categories: 40.4% indicated that the main threat is “the unfeasibility of mining projects”, while 28.8% indicated that “there are no threats, as it is an opportunity for improvement”.

Finally, in connection with the obstacles and facilitators for implementing these new strategies, the focus group participants commented that the main obstacle is “Industry secrecy” and the main facilitator would correspond to “Transparency of the industry towards communities”. These generalizations were derived from opinions such as: “There is no webpage or place where the benefits that mining grants to society are objectively published” (Interviewee 1) and “It would facilitate the process to make known in more detail what the companies do and the impacts that could occur. The main obstacle is that, due to the lack of transparency, there are people who want them to leave, no matter what they offer.” (Interviewee 4). In order to better understand the population’s perception of this topic, questions were asked specifically about a facilitator and an obstacle. The findings show that 53.8% of respondents believe that the main obstacle is “the lack of a solution that satisfies both parties”, while 35.3%, 24.4%, and 22.4% believe that transparency in the actions of mining companies, the provision of objective general information by mining companies to people, and detailed disclosure of how the industry uses resources, respectively, would facilitate the process.

3.4. Analysis of feasibility and prioritization of strategies

In the context of water scarcity and mineral bodies with increasingly lower grades, which require processing larger quantities of ore to achieve the same production output [

26], the strategy of incorporating assets that enable the optimization of resources represents a fast and cost-effective alternative for reducing the use of continental waters.

In this regard, the Chilean Copper Commission (COCHILCO) [

27] states in its report

“Projections of electricity and water consumption in copper mining until 2032” that although 73% of reused water is currently used in mining, 70% of the remaining 27% of

“new inputs” correspond to continental waters. These figures indicate that the trend of most mining companies continues to focus on the use of continental waters and recirculation, rather than investing in assets to use seawater or to increase the resource stockpile.

This approach may be due to the fact that these assets mostly require vast amounts of capital [

28] as they involve pumping water from coastal to mountainous areas, using processes with reduced efficiency, and increasing the cost per cubic meter of water by approximately 3 times compared to the extraction of continental waters [

29]. In addition, current technology is not efficient enough to make this a profitable alternative in most cases [

30]. For example, it is estimated that a desalination plant requires an investment of between 125 and 200 million dollars [

28]. Despite these challenges, large mining companies are willing to invest this capital to become a “good neighbor” to communities and not overexploit continental resources. COCHILCO projects, through a Montecarlo simulation, that by 2032, 68% of the water used by mining will come from seawater [

27].

In relation to the regulatory change in water use, several authors argue that the country suffers from an excess of water rights concessions [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], which has generated conflicts between communities and mining companies. This situation is due to the fact that the regulations consider water as a public use good, but also as an economic good whose rights can be granted to individuals through free concessions without state intervention. This contradiction has reached a critical level as in each region of the country, multiple companies own a large portion of the rights to use this resource [

32]. In the case of the Antofagasta region, the situation is particularly critical since there is an extreme water deficit that negatively affects people’s quality of life and social development, and exacerbates desertification [

33]. Therefore, prioritizing water as a national public use good over its commercial use would help mitigate the negative effects of water rights concessions and encourage the industry to seek other alternatives.

In the development of feasible agreements through participatory engagement between communities and mining companies, there are successful cases in which both parties coexist in a situation of respect and mutual benefit. For example, the mining company Sierra Gorda SCM, located less than 1 kilometer from the homonymous borough, has managed to sign agreements with its neighbors through dialogue tables on issues of employability, environmental education, and community relations. Their relationship with the community has been highlighted as an example of corporate social responsibility due to their transparency, commitment, and immersion in the community [

34]. Therefore, this strategy can be highly effective as long as companies are willing to share and commit significantly to communities. Among the factors that hinder a good relationship between these agents are the lack of direct communication, impartiality, ignorance of the community’s expectations, and the lack of benefits or well-being provided to the community by the mining company.

In order to address the problem of water use in the mining industry in Chile, specific strategies must be prioritized. First, the industry must seek new technologies and ways to reuse water to reduce water stress in watersheds and mitigate the environmental damage caused by the consumption of continental waters. Additionally, it is crucial for mining companies to establish strong relationships with neighboring communities, actively engaging in promoting progress and well-being in the community. Finally, the Chilean government must consider water resources as a common consumable good and not just as an economic good. However, it is acknowledged that this last strategy may be difficult to implement due to the country’s complex political climate [

35].

4. Discussion

Concerning the stage of characterization and understanding of the reality, the focus group and the surveyed individuals agree that the management of water resources in Chile is carried out inadequately; the surveyed population considers that this is due to the pursuit of individual interests by the agents involved. These findings confirm those from previous studies conducted in Chile such as those by Rivera et al. [

5] and Aitken et al. [

8]. These authors also note that the current management does not consider aspects such as the maintenance of the ecological flow, and that the current regulations are inadequate and that there is an excessive granting of water rights.

Regarding the stage of high-impact proposals, despite three of the four focus group members being active collaborators in the mining industry, they all presented different proposals to address the issue. Among the options, investment in assets that optimize water use or increase the availability of the water resource stands out, since it had a high degree of acceptance among respondents. According to the analysis of strategies and their prioritization, this alternative was configured as one of the most feasible and with the greatest impact. However, its main disadvantage is the high investment of resources necessary for its implementation, which suggests the need to establish participatory engagement to obtain feasible agreements with communities to make its execution viable. In this regard, the majority of focus group members indicate that the strategy could work, albeit under certain conditions. These results are consistent with the conclusions of Rodríguez et al. [

36], who highlight the importance of establishing direct and mutually beneficial communication relationships with communities to obtain and maintain SLO. These results are also supported by the projection made by Ernest & Young [

37], where the main risk and opportunity that the mining industry is facing nowadays is to incorporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices.

In the phase of alertness towards transformations, the surveyed population expressed their main concern regarding the proposed strategies as the possible negative impact on the economic viability of mining projects. However, a significant proportion of them consider these strategies as an opportunity rather than a threat. These results are consistent with those from studies conducted by Martínez Varas [

28] and Ahmadvand et al. [

30]. These authors have pointed out that the high investment required to implement this type of technology can affect the expected profits of a project. They also suggest that desalination represents an opportunity for improvement, as it is not yet fully optimized, and it is crucial to reduce energy consumption since it constitutes the main variable cost of the process.

The identified gaps should be addressed through a holistic approach that considers water as a scarce resource in a desert region, essential for the development of all involved parties. Additionally, it is important to promote transparency and close ties between the mining industry and the community, and encourage collaboration to understand and meet the needs of both parties. Finally, it is crucial for the Chilean government to monitor and enforce compliance with regulations to reduce conflicts between stakeholders and ensure the proper distribution and management of water resources.

5. Conclusions

The present investigation has ascertained that the management of water resources in the northern region of Chile is currently deficient in integrating social and environmental factors. To integrate such factors into resource management, the study examined the applicability of various proposed strategies from the perspective of the different agents utilizing the water resource. The results reveal a perception of deficient water management in the area, due to the pursuit of individual interests among the involved parties. Legal factors and mining executives were identified as key factors for improving this perception. After extensive analysis and literature review, investing in assets for water reuse or generating a new stock of this resource and implementing an effective communication policy with communities and agents involved in resource management was found to be the best strategy for incorporating environmental and social factors. In this context, the study detected the primary threat to be the infeasibility of mining projects due to the high monetary capital required to implement the proposed strategies. Nonetheless, both industry participants and the general population regard this strategy as an opportunity for the sector’s improvement. Furthermore, the study elucidated that improving the perceptions of the industry’s transparency and trust towards other agents would be the primary facilitator of the process, while obstacles include the lack of a satisfactory solution for both parties and the industry’s characteristic secrecy.

Among the findings, it is relevant to mention that both the focus group and the surveyed population showed disagreements regarding which strategy to take. This could be suggested as a symptom that both the industry and the population do not have clear guidelines on sustainable strategies applicable to water management. It is proposed to address this gap by providing proper training in sustainability and water governance guidance policies for their management professionals.

This study has identified several shortcomings in water management in the northern region of Chile, including inadequate participatory engagement with communities, deficiencies in the current regulatory framework, and a lack of trust in the mining industry. To address these issues, the following measures are recommended: firstly, taking a holistic approach to the problem by considering all the agents involved in water management; secondly, engaging in participatory processes to establish realistic agreements between the mining industry and local communities; thirdly, promoting oversight by the local government to ensure compliance with current regulations; and finally, encouraging a committed and transparent approach to building relationships between the relevant parties. These proposed actions are expected to contribute to the development of a more effective and sustainable water resource management system in northern Chile, while also facilitating the integration of communities and agents involved in this process.

Author Contributions

Review, editing and writing, V.G.H.; A.C.K., Interview and survey: A.C.K.; V.G.H.; Supervision, V.G.H., Analysis of strategies, A.C.K. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their special thanks to the Faculty of Engineering at Universidad del Desarrollo for providing financial support for the publication of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Stage 1. Characterization and understanding of the reality

What do you understand by water resource management in this area? Who are the actors involved?

Making a distinction between industrial, freshwater, and consumable water: What is your opinion on the use of freshwater by the industry? Why?

Where does the problem come from, or what is the origin of the scarcity of drinking water in this area?

Which factors and key communities do you believe should be considered to ensure that the community’s perception is taken into account by the mining industry when managing the water resource?

How does water resource management operate by all its actors, considering a holistic approach?

Stage 2. High impact proposals

- 6.

Understanding what ecological flow is and what it implies: How can we modify the current situation of water resource use by the mining company to avoid affecting the ecological flow and surrounding communities?

- 7.

Considering the scarcity and the use given to the water resource by different agents in this area, do you have any specific proposals for improving or changing the way the resource is managed, ideally in the short term and with high impact? What are they?

- 8.

If a change strategy based on the establishment of feasible agreements between mining companies and communities in desert areas to manage the water resources was proposed, what would you think about such proposal?

Stage 3. Awareness of transformations

- 9.

What, in your opinion, are the costs of implementing an organizational policy that takes communities into consideration to improve the perception of the mining industry?

- 10.

What kind of threat or risk could a plan of agreements like the one described above pose to a mining company?

- 11.

In your opinion, what are the factors that would facilitate and hinder the implementation of a process to improve the perception of the mining industry?

- 12.

What would you recommend to manage these changes?

- 13.

What would be your main concern regarding the application or implementation of this type of strategy?

Appendix B

Stage 1. Characterization and understanding of the reality

- 1.

-

How would you rate the management of water resources in northern Chile?

- a)

Very good

- b)

Good

- c)

Neither good or bad

- d)

Bad

- e)

Very bad

- f)

Prefer not to answer

- 2.

-

What do you think is the main cause of poor water management in the area is, considering all the agents that use the water?

- a)

Poor communication among the agents who use the resource

- b)

Every agent is seeking their own interests

- c)

Because mining operations should reduce their scale

- d)

Prefer not to answer

- 3.

-

Which of the following factors or communities do you consider having the greatest impact on water management in the area?

- a)

Shareholders of mining companies

- b)

Chilean government

- c)

Farming communities

- d)

Shareholders of local water management and distribution companies

- e)

Prefer not to answer

Stage 2. High impact proposals

- 4.

-

What do you think is the best strategy to improve water resource management? Consider that ideally this strategy should have high impact and be short-term.

- a)

To develop technology for sustainable and conscious use of the resource

- b)

To change regulations regarding water use

- c)

To invest in assets that optimize the resource (i.e.,: Desalinization, tailings thickness, etc).

- d)

To reduce the magnitude of mining in the area

- e)

Prefer not to answer

- 5.

-

Do you think a strategy based on the implementation of feasible agreements between mining companies and communities to manage the water resource would be effective?

- a)

Yes, I think it would work

- b)

It would work with conditions

- c)

It would work, but it would take a lot of time

- d)

No, it would not work

- e)

Prefer not to answer

Stage 3. Awareness about transformations

- 6

-

What do you think would be the main threat of implementing a plan like the one described above?

- a)

The unfeasibility of mining projects

- b)

A lower availability of job opportunities

- c)

Damage to the mining industry’s image

- d)

There are no threats as it is an opportunity for improvement

- e)

Prefer not to answer

- 7

-

What do you think would be the main difficulty in implementing a strategy like the one described above?

- a)

The secrecy of the mining industry

- b)

The determination of the communities not to want mining operations in the area

- c)

The lack of objectivity in the information provided by the mining industry

- d)

The lack of a solution that satisfies both parties

- e)

Prefer not to answer

- 8

-

What do you think would be the main facilitator when implementing a strategy like the one described above?

- a)

To provide a detailed report of how the industry uses the resource

- b)

Transparency of the industry towards communities

- c)

A participative engagement strategy with communities

- d)

To provide objective general information to the communities

- e)

Prefer not to answer

References

- Briscoe, J. Water as an economic good. Cost-benefit analysis and water resources management, 2005, p. 46-70.

- Ossa-Moreno, J.; McIntyre, N.; Ali, S.; Smart, J. C.; Rivera, D.; Lall, U.; Keir, G. The hydro-economics of mining. Ecological Economics, 2018, vol. 145, p. 368-379. [CrossRef]

- Kunz, N. C. Towards a broadened view of water security in mining regions. Water Security, 2020, vol. 11, p. 100079. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.; Kunz, N.C. Water stewardship: Attributes of collaborative partnerships between mining companies and communities. Water, 2018, vol. 10, no 8, p. 1081. [CrossRef]

- Aitken, D.; Rivera, D.; Godoy-Faúndez, A.; Holzapfel, E. Water scarcity and the impact of the mining and agricultural sectors in Chile. Sustainability, 2016, 8(2), 128. [CrossRef]

- Strachan, C.; Goodwin, S. The role of water management in tailings dam incidents. 2016.

- Kunz, N. C.; Moran, C. J. Water management and stewardship in mining regions. In Handbook of Water Resources Management: Discourses, Concepts and Examples. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021. p. 659-674.

- Rivera, D.; Godoy-Faúndez, A.; Lillo, M.; Alvez, A.; Delgado, V.; Gonzalo-Martín, C., ... ; García-Pedrero, Á. Legal disputes as a proxy for regional conflicts over water rights in Chile. Journal of Hydrology, 2016, 535, 36-45.

- Thomson, I.; Boutilier, R. G. Social license to operate. SME mining engineering handbook, 2011, 1, 1779-96.

- Arteaga Pastor, A. F. Estrategias de responsabilidad social empresarial para mantener una licencia social para operar en minería. Una revisión de la literatura científica entre 2009–2019. 2020.

- Ernest & Young. Top 10 business risks and opportunities for mining and metals in 2022. 2021. Retrieved from https://www.ey.com/en_ca/mining-metals/top-10-business-risks-and-opportunities-for-mining-and-metals-in-2022.

- Owen, J. R.; & Kemp, D. ‘Free prior and informed consent’, social complexity and the mining industry: Establishing a knowledge base. Resources Policy, 2014, 41, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Mendes, L. Mapping of the literature on social responsibility in the mining industry: A systematic literature review. Journal of cleaner production, 2018, 181, 88-101. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J. Mining companies and communities: Collaborative approaches to reduce social risk and advance sustainable development. Resources Policy, 2021, 74, 101144. [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Aguas (DGA). Water usage rights per region. 2016, Retrieved March 15, 2023, from https://dga.mop.gob.cl/productosyservicios/derechos_historicos/Paginas/default.aspx.

- Rivadeneira-Tassara, B.; Valdés-González, H.; Fúnez-Guerra, C.; & Reyes-Bozo, L. A Conceptual Model Considering Multiple Agents for Water Management. Water, 2022, 14(13), 2093. [CrossRef]

- Gundermann, H.; Göbel, B. Comunidades indígenas, empresas del litio y sus relaciones en el Salar de Atacama. Chungará (Arica), 2018, 50(3), 471-486. [CrossRef]

- Puga, J. V.; García, M. C. La Aplicación de Entrevistas Semiestructuradas en Distintas Modalidades Durante el Contexto de la Pandemia. Revista Científica Hallazgos, 2022, 21, 7(1), 52-60.

- Bórquez, A. F.; Silva, K. C.; Reyes, J. Experiencias maestros en el trabajo con estudiantes inmigrantes: Desafíos para el logro de aulas inclusivas. Revista colombiana de educación, 2022, (85), 14. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. L. Focus groups. Annual review of sociology, 1996, 22(1), 129-152.

- Gajardo, G.; Redón, S. Andean hypersaline lakes in the Atacama Desert, northern Chile: Between lithium exploitation and unique biodiversity conservation. Conservation Science and Practice, 2019, 1(9), e94. [CrossRef]

- Cortés Vargas, M. A. Análisis de consolidación y secado de relaves para evaluar mejoras de recuperación de aguas en tranques de relave convencionales operados con celdas interiores. 2019.

- DAL-RÉ, R. Waivers of informed consent in research with competent participants and the Declaration of Helsinki. European. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2023, vol. 79, no 4, p. 575-578. [CrossRef]

- University of Toronto. Activities Exempt from Human Ethics Review. 2023. Retrieved from https://research.utoronto.ca/ethics-human-research/activities-exempt-human-ethics-review.

- Government of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (2022). 2023. Retrieved from https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique_tcps2-eptc2_2022.html.

- Library of the National Congress of Chile. Law 20,120: About the scientific research in humans, their genome, and the ban on cloning humans. 2023. Retrieved from https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=253478.

- COCHILCO. Projections of electricity and water consumption in copper mining until 2032. 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cochilco.cl/Mercado%20de%20Metales/Proyección%20Consumo%20EE%202022-2033%20Final%20con%20rpi.pdf.

- Martínez Varas, J. A. Sinergia entre los sistemas de agua desalada de la minería y los requerimientos de consumo agrícola en la Provincia de Copiapó. 2022.

- Odell, S. D. Desalination in Chile’s mining regions: Global drivers and local impacts of a technological fix to hydrosocial conflict. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022, 323, 129104. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadvand, S.; Abbasi, B.; Azarfar, B.; Elhashimi, M.; Zhang, X.; Abbasi, B. Looking beyond energy efficiency: An applied review of water desalination technologies and an introduction to capillary-driven desalination. Water, 2019, 11(4), 696. [CrossRef]

- Belmar, I.; Fernández, A.; Leal, G. Efectos del otorgamiento de derechos de agua en la disponibilidad de recursos hídricos en la cuenca del río Ñuble, Chile Centro Sur/Effects of water rights allocation on water resources availability within the Ñuble River Basin, South Central Chile. Tecnología y ciencias del agua, 2020, 11(5), 225-273.

- Larraín, S.; Poo, P. Conflictos por el agua en Chile: entre los derechos humanos y las reglas del mercado. 2019.

- Correa-Parra, J.; Vergara-Perucich, J. F.; Aguirre-Nuñez, C. Privatización y desigualdad del agua: Coeficiente de Gini para los recursos hídricos en Chile. 2020.

- Piasecki, R.; Gudowski, J. Corporate social responsibility: The challenges and constraints. Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, 2017, vol. 20, no 4, p. 143-157. [CrossRef]

- Atria, F. Constituent moment, Constituted powers in Chile. Law and Critique, 2020, vol. 31, p. 51-58.

- Rodríguez, j.c.; Ortiz, C.; Broitman, C. Chile, país minero. Licencia social y lugares de enunciación en los conflictos socioambientales en Chile. Izquierdas, 2021, vol. 50, p. 0-0.

- Ernest & Young. Top 10 business risks and opportunities for mining and metals in 2023. 2023, Retrieved from https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/mining-metals/ey-top-10-business-risks-and-opportunities-for-mining-and-metals-in-2023.pdf.

| 1 |

The Chilean constitution is currently under review. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).