1. Introduction

The introduction Microbial polysaccharide is a substance produced by microorganisms during growth and metabolism. It is a novel biopolymer possessing the physical and chemical properties of thickening, emulsification, stability, and gelation, along with biocompatibility, sustainability, and environmentally friendly features. This renders it highly versatile and useful in a variety of areas, including food, petroleum, cement, textiles, and cosmetics[

1,

2,

3,

4]. In the petroleum industry, biopolymers are widely used in oilfield drilling fluids, fracturing fluids, and profile control and water plugging [

1]. Drilling fluid is a multifaceted mixture consisting of solids, liquids, and chemical agents. Xanthan gum, guar gum, starch, and cellulose derivatives are commonly used biological viscosifiers in drilling fluids due to their good viscosity-increasing properties. However, under extreme high-temperature and high-salt circumstances, the fluid’s weaknesses, including poor thermal stability, weak shear capacity, and reduced viscosity-increasing ability, become more evident [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Hydraulic fracturing technology is a commonly employed method for modifying reservoirs. The effectiveness of the fracturing fluid is crucial to the success of the operation. Biopolymers, such as guar gum, are added to the fracturing fluid as thickeners with retarding properties. Enhancing the temperature resistance of guar gum is achievable by modifying its molecular chain and grafting it with rigid agents. To broaden its application scope, common cross-linking agents include borate, Ti

4+, Zr

4+, and Al

3+ [

9,

10]. As oilfield water plugging agents, biopolymers can not only improve the water absorption profile and displacement effect of water injection wells but also expand the effective layers and directions of oil wells, thereby overall improving oil recovery. Biopolymers currently used for water plugging and profile control mainly include modified starch, modified cellulose, guar gum, xanthan gum, chitosan, etc. However, the majority of biopolymer plugging agents are currently still undergoing laboratory research and are only being produced in small batches [

1].

Currently, the majority of oil fields in China have entered the tertiary oil recovery stage [

11,

12], among which polymer flooding is widely used because it produces more oil than other chemical-enhanced oil recovery methods and is environmentally friendly. The reservoir environment is becoming increasingly hostile as the depth of reservoir formation deepens, the concentration of formed water ions increases, and oil-driven technologies to alter the acidity and alkalinity of the reservoir proliferate, such as CO

2 flooding, alkali flooding, and ternary composite flooding. At present, polymer flooding is developing from medium and low-temperature oil reservoirs to high-temperature and high-salt oil reservoirs. However, the conditions of high-temperature and high-salt oil reservoirs are complex, the oil displacement mechanism needs to be deepened, and the compatibility of the oil displacement system is poor. There is an urgent need for temperature and salt resistance and adaptability to harsh reservoir environments with polymer oil displacing agents [

13]. The polymer oil repulsion system commonly used in oilfields is mainly based on partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) and its modified products[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], this system has excellent oil repulsion effect in low and medium temperature, low and medium mineralization reservoirs, but subject to the influence of temperature, mineralization and acidity and alkalinity, and easy to the environment is prone to pollution, and biopolymer to improve the apparent viscosity of the oil repulsion system and expand the efficiency of the wave and the effect of the system is not weaker than the HPAM, and can be degraded, safe and environmentally friendly.

In recent years, numerous oil fields have implemented microbial-enhanced oil recovery technology (MEOR) to meet the requirements of green and efficient development. This technology has received attention owing to its eco-friendly attributes, superior applicability, and cost-effectiveness [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Zhou Hongtao [

13] explored the feasibility of diutan gum, welan gum, and xanthan gum as new polymers for oil repulsion; Zhang Xifeng [

24] investigated the static and dynamic rheological properties of welan gum aqueous solution at a formation temperature of 40°C and the factors affecting them; Karl-Jan [

25] investigated the rheology of schizophyllan, scleroglucan, guar gum, and xanthan gum in brines at concentrations ranging from 10-2300 mg/L, temperature levels ranging from 25-70°C, and total dissolved solids concentrations of 30100 mg/L and 69100 mg/L; Lai Nanjun [

26] investigated the rheological properties and the ability to enhance the recovery of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and konjac gum at a temperature of 130°C and a mineralization level of 223.07 mg/L. However, less research has been done on the viscosity enhancement, rheological properties, and long-term stability of the three biopolymers, namely, diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan, under extreme reservoir conditions.

The main objective of this paper is to explicitly determine the viscosity enhancement and rheological properties, as well as the oil drive potential of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan solutions. So the viscosity-concentration relationship, steady-state rheological shear properties, linear viscoelastic region LVR and oscillatory frequency scanning, temperature resistance, salt resistance, acid and alkali resistance, long-term stability evaluation in extreme environments were investigated in detail, and they were compared with each other to provide technical support for the construction of polymer oil displacement system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental material

Diutan gum and scleroglucan concentrate were supplied by Hebei Xinhe Bio-Chemical Co., LTD., while xanthan gum was supplied by Meihua Bio-Technology Group Co., LTD. Diutan gum, light yellow colloid, effective content 2 %, molecular weight 5.2×106Da; Scleroglucan, milky white colloid, effective content 2%, molecular weight 1.3×105~6×106Da; Xanthan gum, light yellow powder solid, effective content 90%, molecular weight 2×106Da.

The biopolymer solution is prepared with simulated brine, and six kinds of simulated brine with different salinity were prepared, of which 220 g/L simulated brine was the mother liquor, and the remaining five simulated brine were diluted from the mother liquor. Their compositions are shown in

Table 1. The simulated brine preparation water was distilled water, and sodium chloride, calcium chloride, magnesium chloride hexahydrate, sodium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid reagent grades were purchased from China Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Unless otherwise specified, biopolymer solutions are prepared using 6g /L simulated saline.

2.2. Solution preparation

2.2.1. Preparation method of diutan gum and scleroglucan

At room temperature (25°C), place an appropriate amount of biopolymer concentrate in a beaker, add a small amount of simulated salt water, stir the solution at a speed of 1000 r/ min for 10 min, add the remaining simulated salt water to adjust to volume, and stir for another 3 hours. , until the biopolymer is fully dissolved to obtain a biopolymer solution with a target mass concentration. The prepared water not mentioned in the test experiment is simulated brine with a total salinity of 6 g/L.

2.2.2. Preparation method of xanthan gum

The simulated brine was swirled at 800r/min, and then xanthan gum powder was slowly added along the vortex wall. After all xanthan gum is added, stir at 800r/min for 30min, then reduce the speed to 600r/min and continue stirring until completely dissolved.

Before testing, it must be left at room temperature for 12 hours to fully swell and mature, and internal air bubbles must be eliminated to prevent interference with later performance measurement research.

2.3. Experimental instruments

Thermo Fisher Scientific HAAKE rotation rheometer MARS 60, equipped with two test systems: CC41 DG/Ti-02210522 double-cylinder test system and PZ DG 38 Ti high temperature sealed test system, Thermo Fisher Company, Germany; Brookfield viscometer, Brookfield Company of the United States; Electric blast drying oven, Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.; Electric constant temperature water bath, Shanghai Boxun Industrial Co., Ltd.; pH meter, Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.; Cantilever electric stirrer instrument, Shanghai Lichenbangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd.; electronic balance, Shanghai Zhuojing Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.

2.4. Experimental test methods

2.4.1. Viscosity increase performance test

The apparent viscosities of the three biopolymer solutions at different concentrations were determined at 20 °C and 90 °C to examine the relationship between apparent viscosity and solution concentration. Three biopolymer solutions with a concentration of 1500 mg/L were prepared according to the method of

Section 2.1 using 6 g/L simulated brine under two conditions, (1) temperature range of 20-90 °C with a shear rate of 7.34 s

-1 using a CC41 DG/Ti - 02210522 double cylinder test system; (2) temperature range of 70-150 °C with a shear rate of 250 s

-1 using a PZ DG 38 Ti high temperature confinement test system, to determine the apparent viscosity of the three biopolymer solutions as a function of temperature. The above six simulated brines with different mineralizations were used to formulate biopolymer solutions at a concentration of 1500 mg/L according to the method in section 2.1, and the apparent viscosity changes of biopolymer solutions with different mineralizations at different temperatures were determined. Three biopolymer solutions with a concentration of 1500 mg/L were prepared using 6 g/L simulated brine, and the viscosity changes with pH of the three biopolymer solutions were determined in the pH range of 3-10, at a temperature of 90°C, and a shear rate of 7.34 s

-1.

2.4.2. Rheological properties test

All rheological properties, including steady-state rheological shear, oscillation amplitude sweep, and oscillation frequency sweep tests, were performed on a Haake rotational rheometer Haake MARS 60, using a CC41 DG/Ti-02210522 double-cylinder test system and PZ DG 38 Ti high temperature closed testing system. All tests were repeated at least three times, and the relative deviation was less than 0.05%.

Steady-state rheological shear performance test

The steady-state rheology of three biopolymer solutions was tested to examine the relationship between apparent viscosity and shear rate. The shear rate range was 0.01~1000 s

–1, the temperature was 90 °C, and the temperature deviation was controlled at ±0.1 °C, the polymer solution mass concentration is 1500 mg /L. The measured steady-state rheological curve is fitted using the power law function (1).

In the formula: is the apparent viscosity; is the consistency factor; is the power-law index, dimensionless; is the shear rate, s –1.

Linear viscoelastic zone LVR and oscillation frequency scanning test

First, strain amplitude scanning was performed on the three biopolymer solutions to determine the linear viscoelastic region LVR of the solution. The concentration of the prepared solution was 1500 mg /L, the oscillation frequency was fixed at 1 Hz, the temperature was 90 °C, and the strain was from 0.01% to 100%; after determining the linear viscoelastic zone L VR of the solution, the solution is then subjected to an oscillation frequency scan test, the shear stress is fixed, and the frequency scan is performed in the range of 0.01-10.00Hz at 90 °C.

2.4.3. Long-term stability performance test

Research Take 400 ml of 1500mg/L diutan gum and scleroglucan biopolymer solutions respectively, pour them into 20 high-temperature resistant glass bottles with a volume of 12ml, inject nitrogen into them and seal them, and remove the solution Dissolved oxygen in the solution was used to prevent the oxygen oxidation solution from interfering with the apparent viscosity data. The glass bottle containing the biopolymer solution was then placed in a constant temperature oven at 100 ° C for aging, and the apparent viscosity was measured at intervals.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of viscosity increasing properties of three biopolymers

3.1.1. Viscosity-concentration relationships of three biopolymers

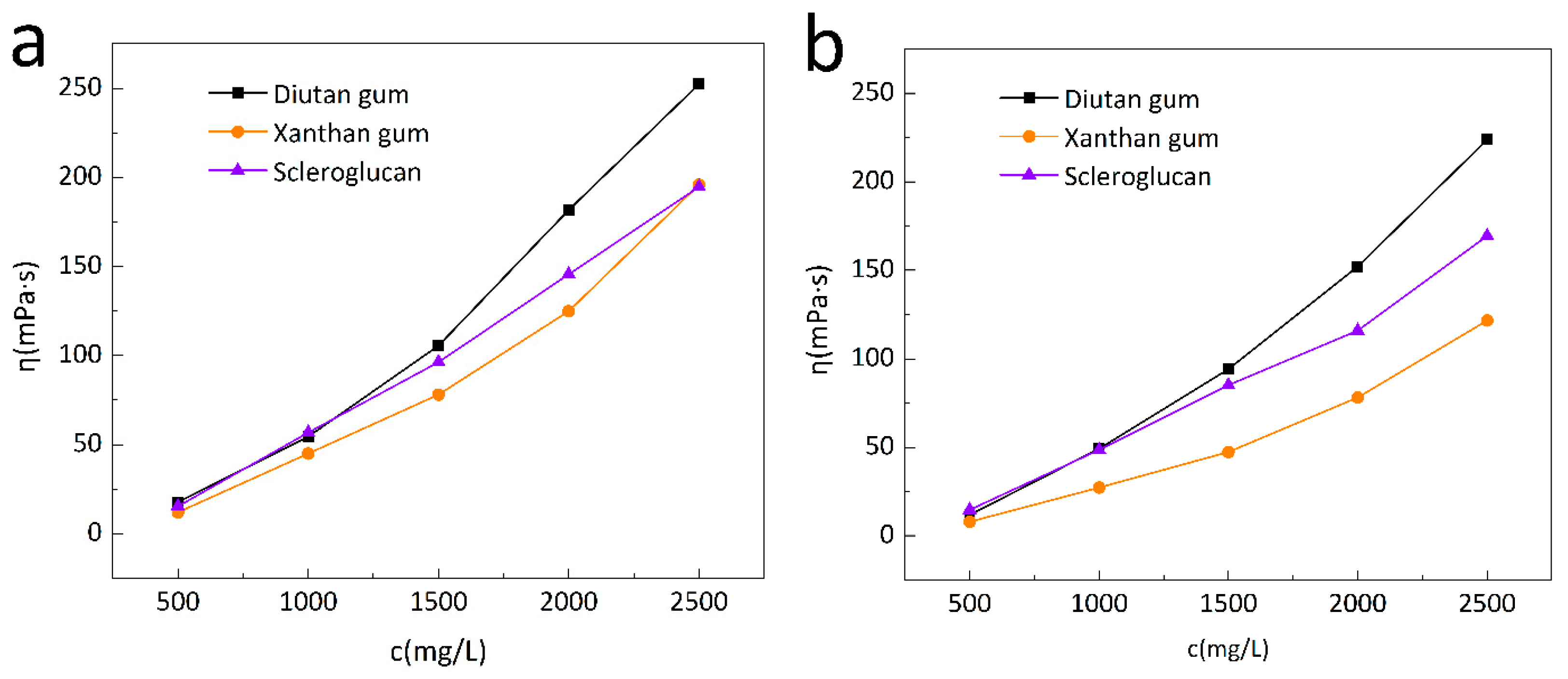

The apparent viscosities of the three biopolymer solutions were measured at a shear rate of 7.34 s

-1 and temperatures of 20 °C and 90 °C. As can be seen in

Figure 1, the apparent viscosities of all three biopolymer solutions increased with the increase in solution concentration, but the apparent viscosities of the biopolymer solutions increased to different extents at different temperatures for different concentrations. For example, at 90 °C, all three biopolymer solutions have a concentration of 2500 mg /L, and the apparent viscosities are 223.8 mPa·s for diutan gum,169.45 mPa·s for scleroglucan and 121.7mPa·s for xanthan gum, the apparent viscosity of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution is nearly 1.84 times and 1.39 times that of xanthan gum respectively.

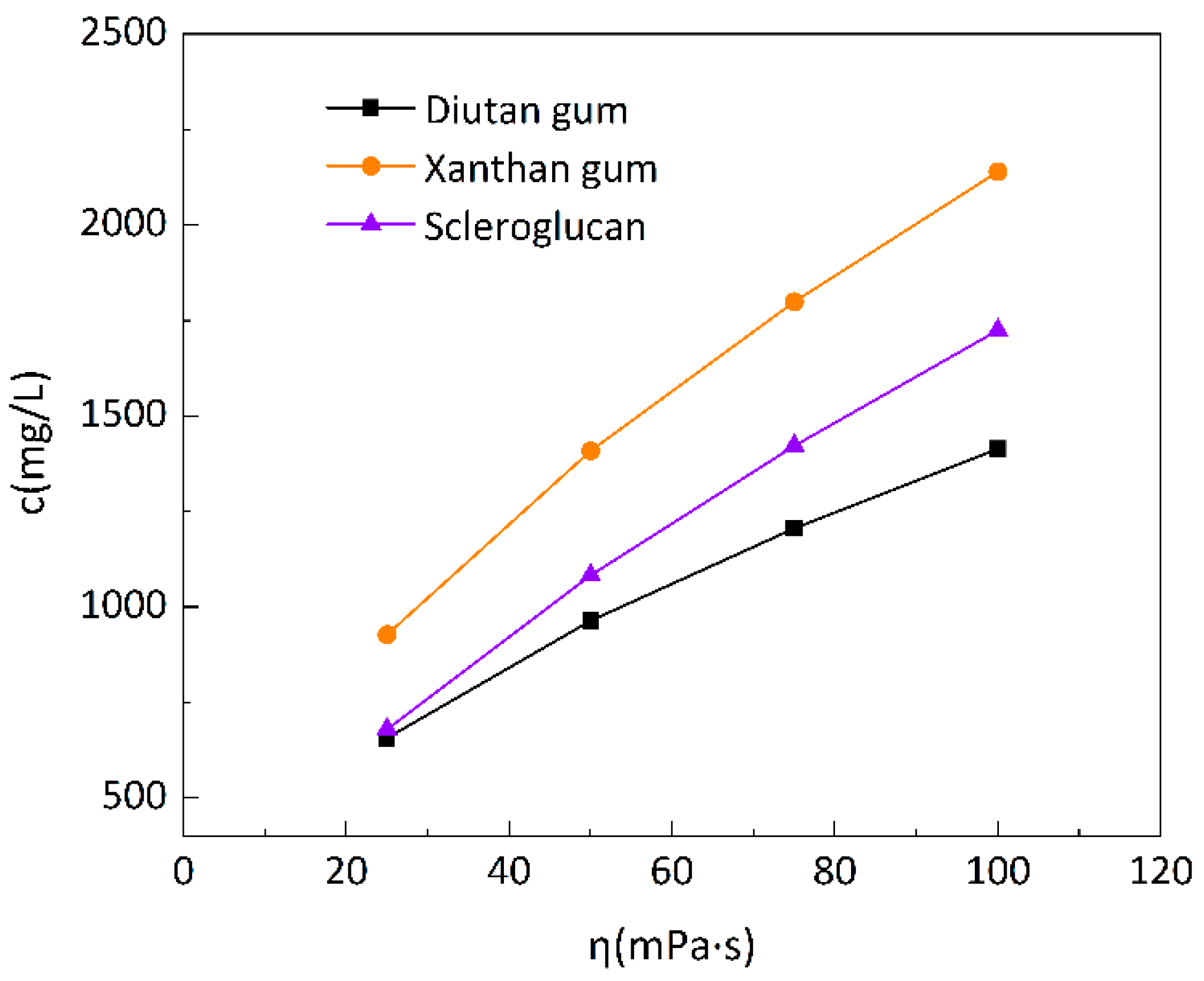

Figure 2 is the change curve of biopolymer solution concentration with apparent viscosity at 90°C. To make the solution have the same apparent viscosity (100mPa·s), it is necessary to add 1414mg/L of diutan gum or 1725mg/L of scleroglucan, while for xanthan gum, a higher concentration is needed, and under the same conditions, it is necessary to achieve the same apparent viscosity, which is about 2140mg/L.

The diutan gum solution showed better viscosity thickening than xanthan gum and scleroglucan solutions. This is due to the high molecular weight of diutan gum, the increase in the entanglement of polymer chains at high concentrations, the corresponding increase in apparent viscosity, and the formation of agglomerates at low shear rates (7.34 s

-1) by entangling the stretched molecules with each other, resulting in greater resistance to fluid flow, leading to a better viscosity enhancement effect. This is similar to the findings of Xu [

2], Holzwarth [

27], and G.P. Mota [

28].

3.1.2. Temperature resistance performance test

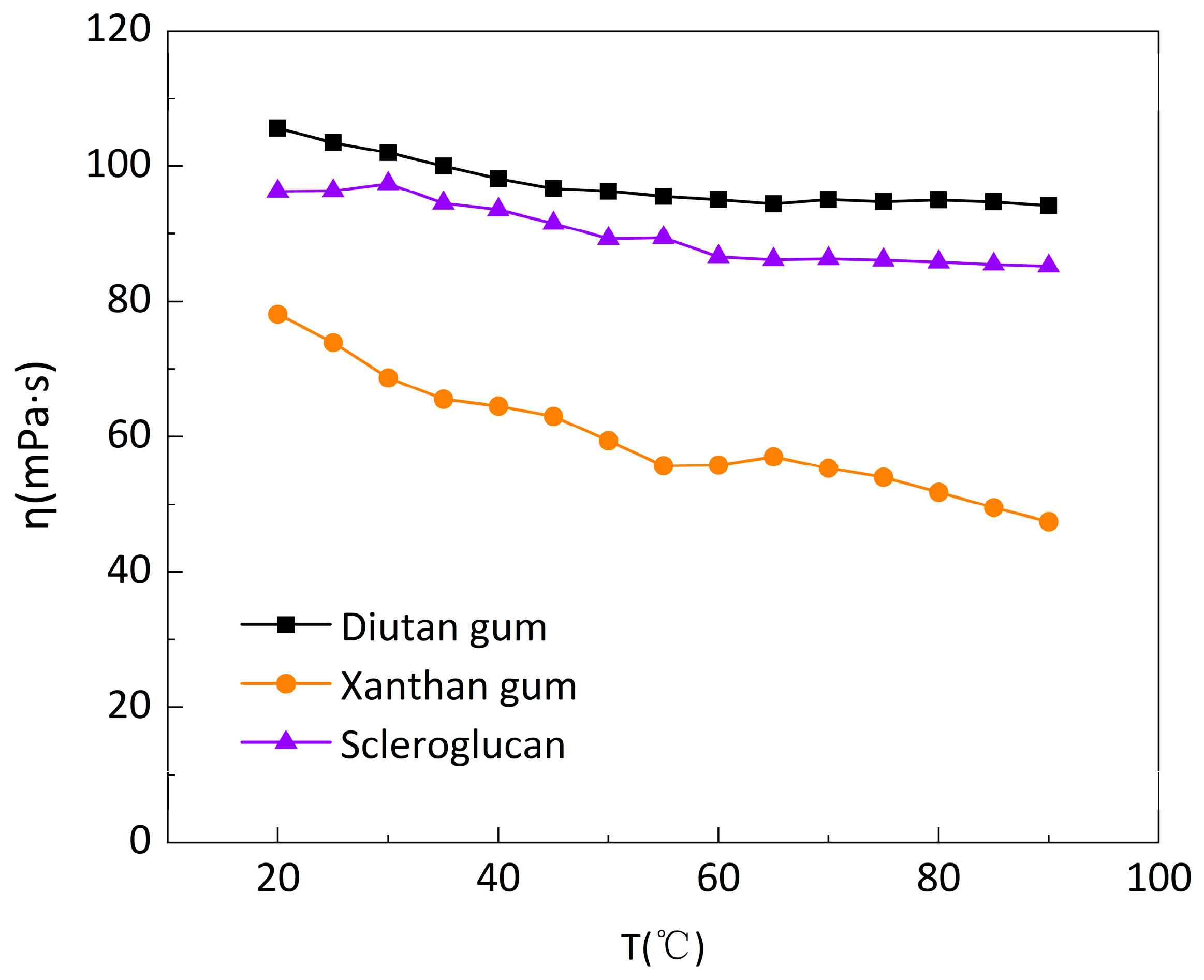

The solutions of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan were prepared at a concentration of 1500mg/L, respectively, and the apparent viscosity versus temperature curves of the three biopolymer solutions was measured at a low shear rate (7.34s

-1) and a temperature range of 20-90°C, which are shown in

Figure 3. It can be seen that all three polymer solutions exhibit thermal thinning behavior [

29]: the apparent viscosity decreases to varying degrees with increasing temperature, with the apparent viscosity of diutan gum and scleroglucan solutions decreasing to a lesser extent, only from 105.6mPa·s and 96.28mPa·s at the initial 20 °C to 94.17mPa·s and 85.21mPa·s at 90°C. Whereas, the apparent viscosity of xanthan gum solution decreased further, from 78.12mPa·s at initial 20°C to 47.42mPa·s at 90°C.

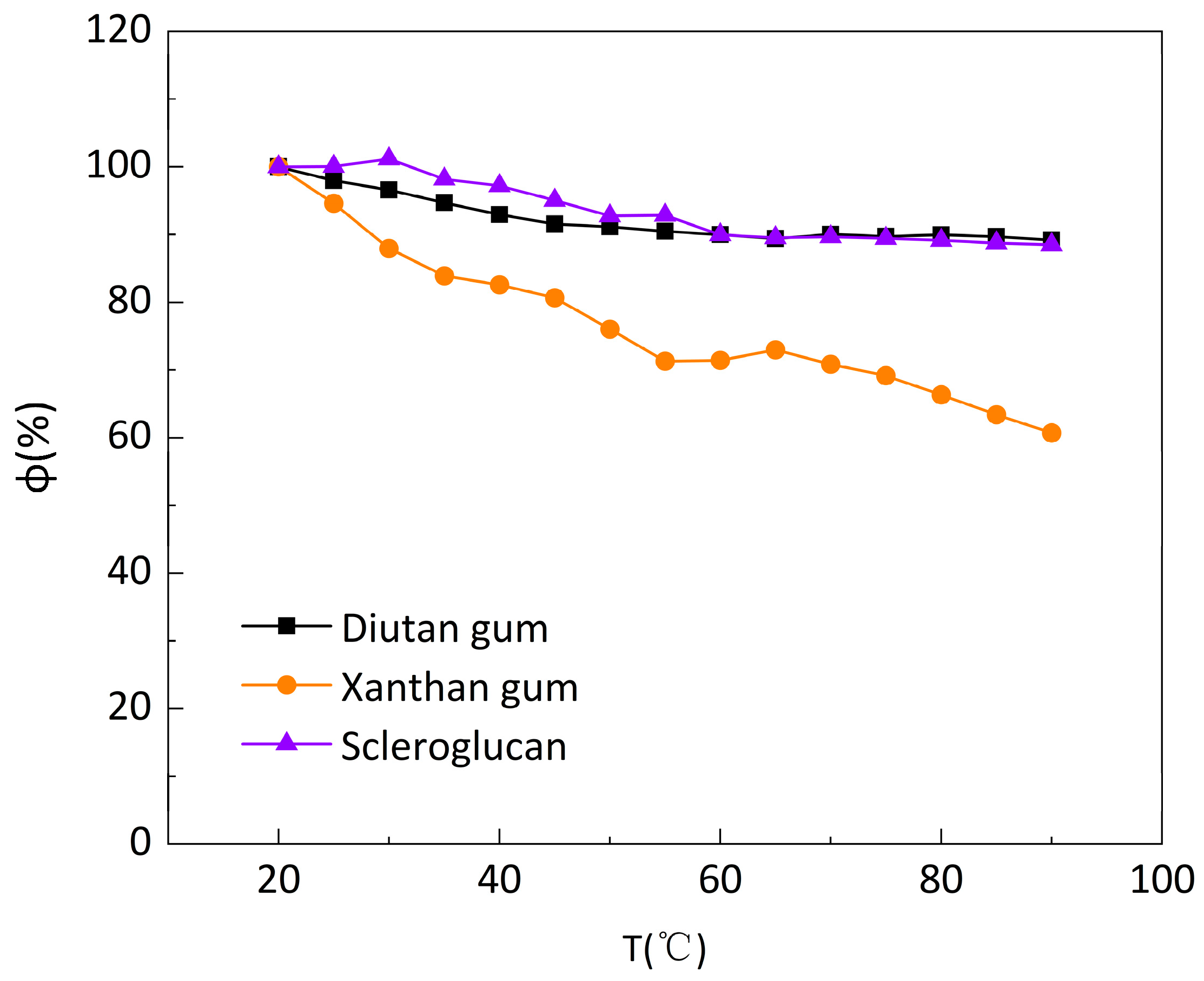

Figure 4 shows the apparent viscosity retention φ (φ, the ratio of apparent viscosity at different temperatures to the initial apparent viscosity at 20°C) of the three biopolymer solutions at temperatures ranging from 20 to 90°C and at a shear rate of 7.34 s

-1. The apparent viscosity retention φ of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution changed extremely slightly with the increase in temperature, while the retention φ of xanthan gum solution gradually decreased and the decrease was larger. Additionally, at the same temperature, the apparent viscosity retention φ of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution was always higher than that of xanthan gum, and the apparent viscosity retention φ of the diutan gum and scleroglucan solution were 89.18% and 88.50%, respectively, while that of the xanthan gum solution was only 60.70% at the temperature of 90°C.

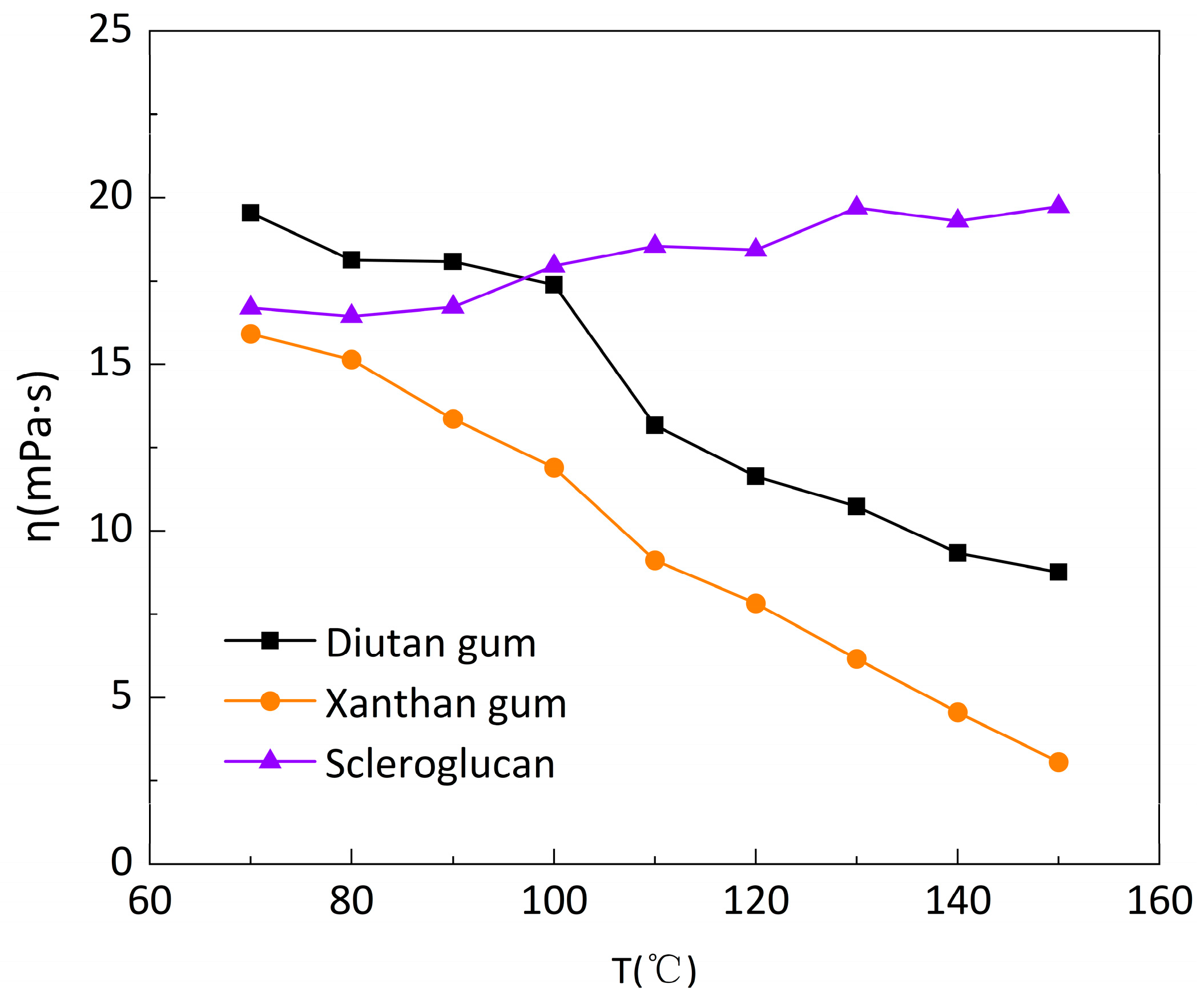

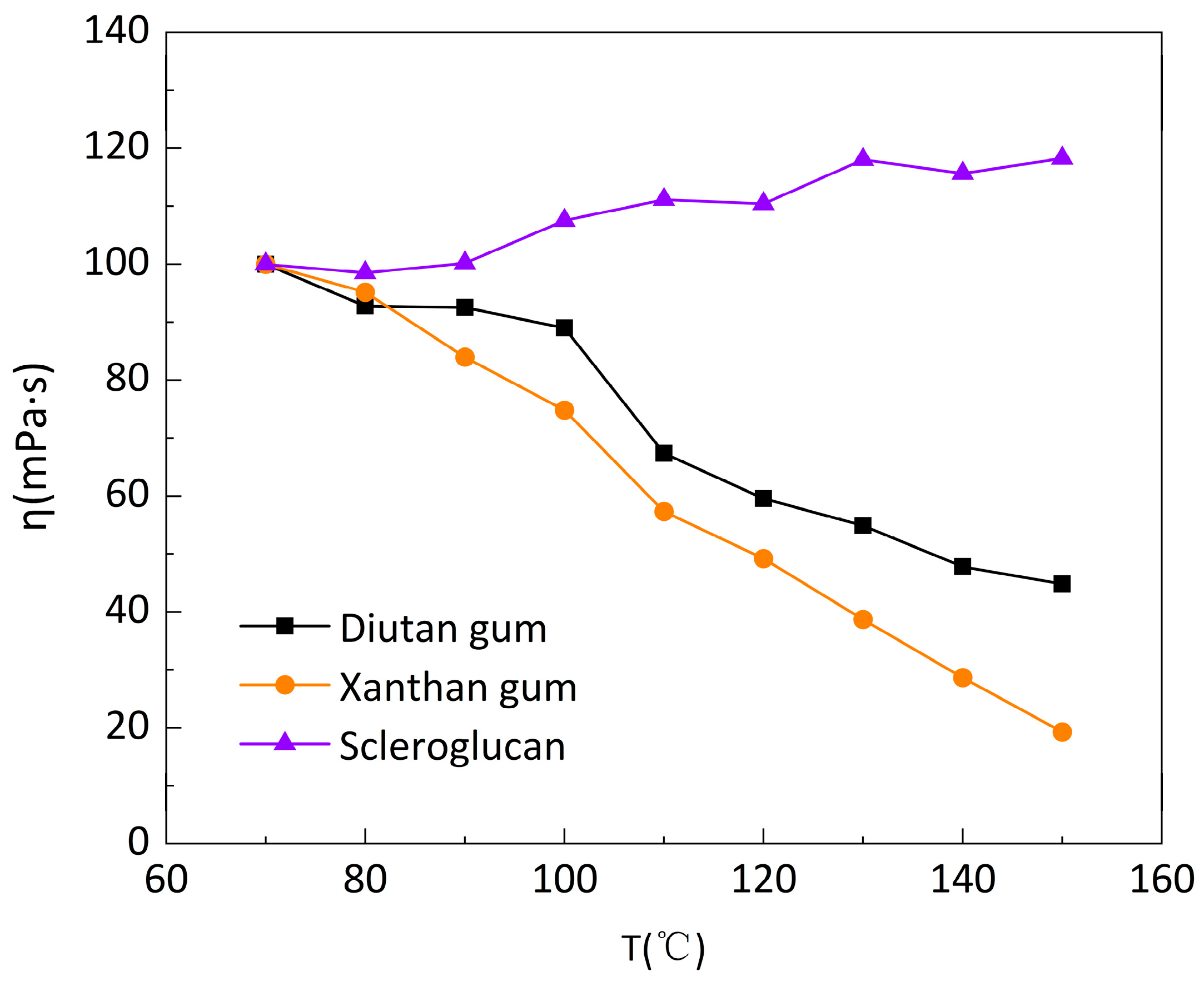

Under the above experimental conditions, the CC41 DG/ Ti-02210522 two-barrel test system of HAAKE Rheometer was used, and the temperature limit of this system was 90°C. For the higher temperature range, a HAAKE Rheometer PZ DG 38 Ti high-temperature confinement test system was used. However, this test system is only suitable for high shear rates (>170 s

-1), so the apparent viscosity of the three biopolymer solutions was tested as a function of temperature in the temperature range of 70-150 °C and at a shear rate of 250 s

-1, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. It can be seen that the apparent viscosity of the diutan gum and xanthan gum solutions decreases significantly with increasing temperature, while the apparent viscosity of the scleroglucan solution does not only decrease but also slightly increases. Compared with 70°C, at 150°C, the apparent viscosity retention rate φ of diutan gum and xanthan gum solution was only 44.83% and 19.3%, while scleroglucan solution indeed had 118.27% apparent viscosity retention rate, which was still able to maintain a higher apparent viscosity under the ultra-high temperature.

It is clear that diutan gum and sclerogucan are less insensitive to temperature than xanthan gum. Commonly, the entanglement of biological macromolecules and the strength of polymer networks are mainly formed by van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds [

30], and an increase in temperature accelerates the movement of molecules and distorts a large number of hydrogen bonds, leading to a gradual loss of the second nearest-neighbor spatial correlation and weakening the van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds [

2,

31]. At high temperatures, water molecules in the molecular chain escape easily due to the weakening of hydrogen bonds and the thermal motion of the molecules. In xanthan gum solution, the reticular structure exists at 20 °C and was destroyed long ago at 90 °C. Water molecules adhering to the edges of the double helix detach from the molecular chain, leading to a decrease in water retention. Meanwhile, xanthan gum molecules undergo a conformational transition from an ordered double-helical structure to a disordered helical structure in the process of temperature increase, weakening the association between molecular chains, and the apparent viscosity gradually decreases[

2,

13]. Due to the rigidity of the molecular chain, the double helix structure of diutan gum can still maintain the conformation well at higher temperatures (<110°C), and a large number of water molecules are still tightly trapped in the double helix structure due to the strong internal force, so it has strong temperature resistance [

2,

28,

29]. The molecular chain of scleroglucan exists in a triple helix structure in aqueous solution, and this structure, due to the stabilization of intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding, makes scleroglucan exhibit strong stability over a wide range of temperatures (<150°C) [

32,

33,

34,

35], which is also approximate to the findings of Kalpakci [

36] et al. Therefore, it can be concluded that diutan gum and scleroglucan solutions have better temperature resistance compared to xanthan gum solutions.

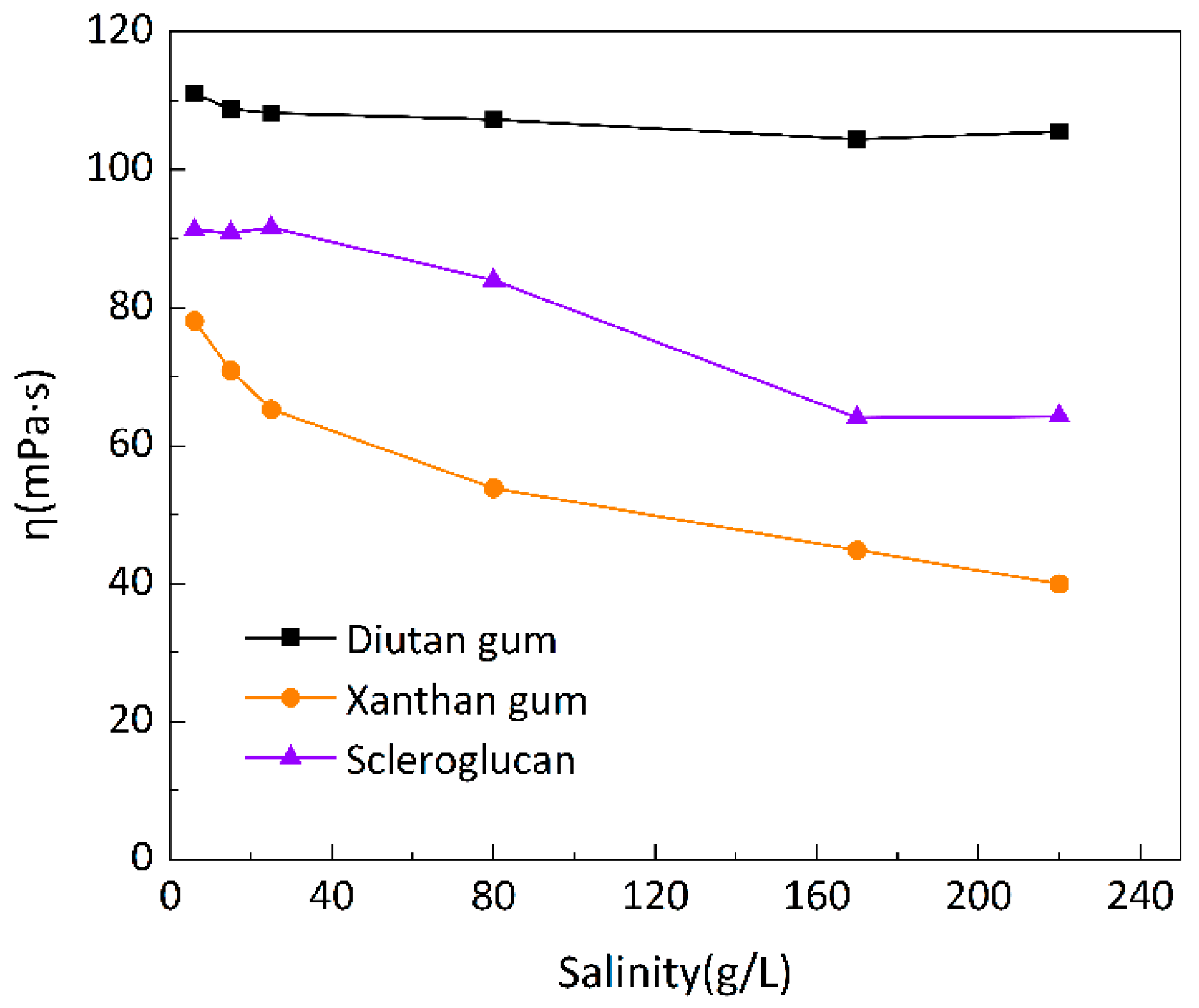

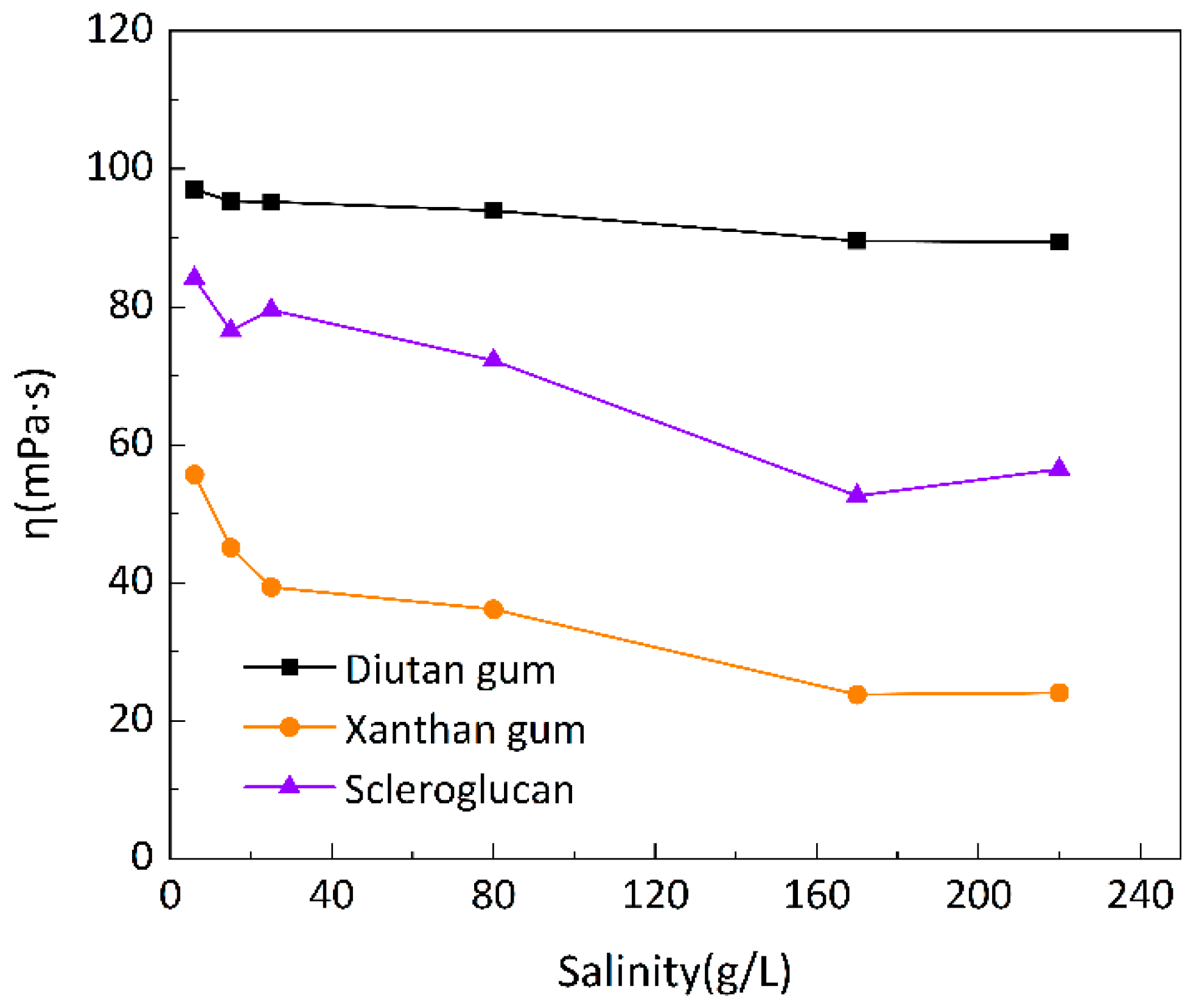

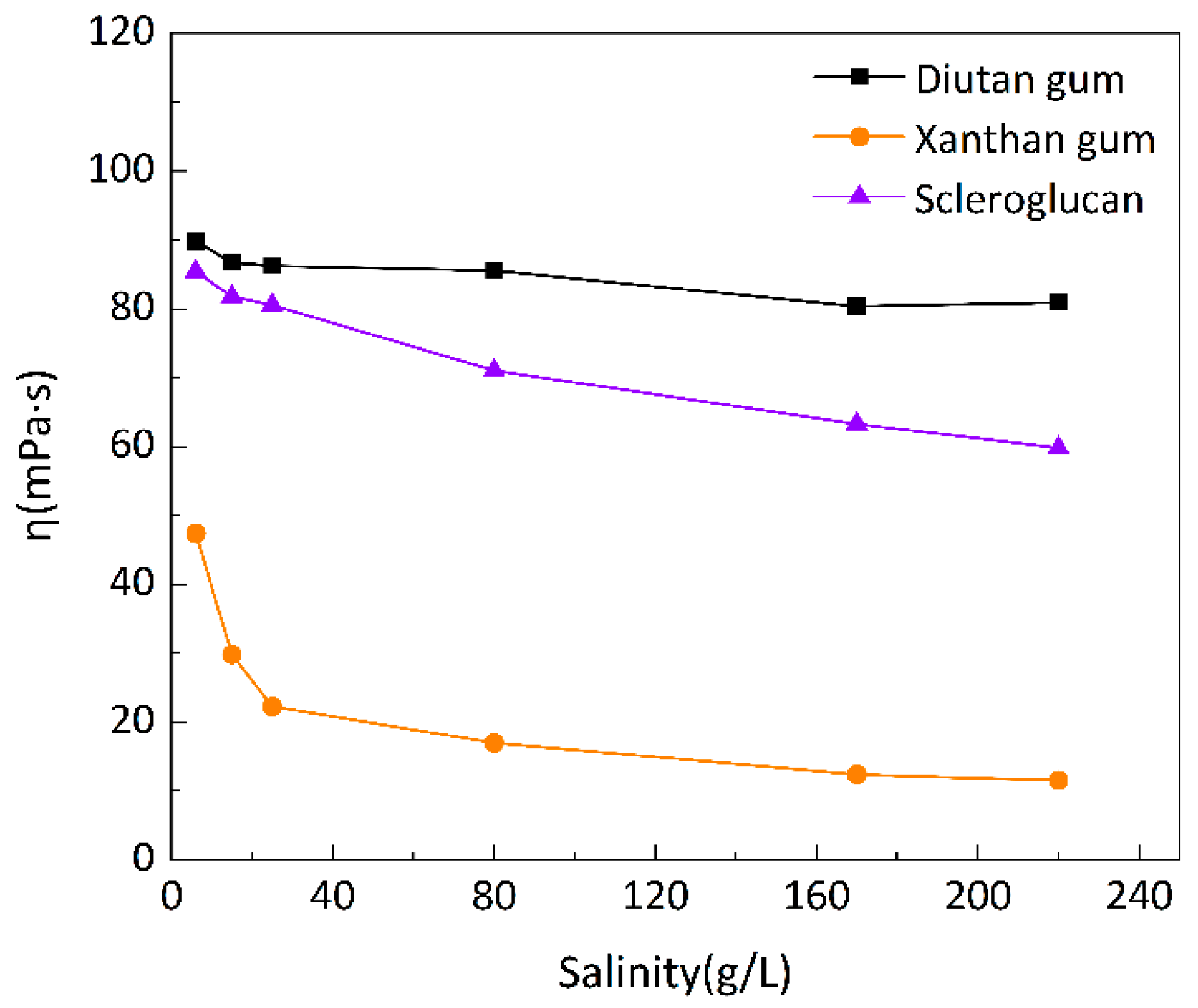

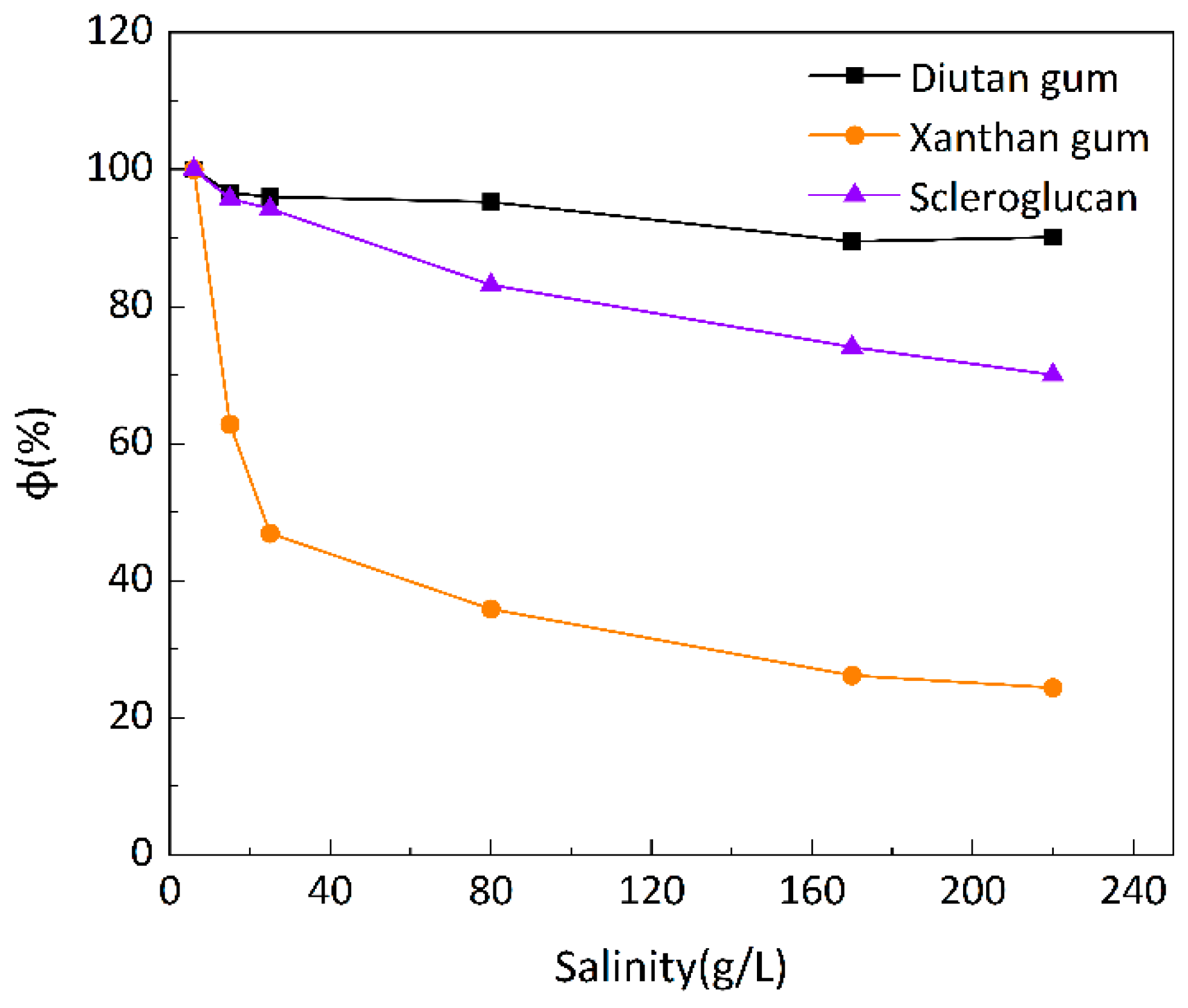

3.1.3. Comparison of salt resistance of three kinds of biopolymers

To investigate the salt resistance of the three biopolymer solutions at different temperatures, six simulated brines with different mineralizations were prepared for the formulation of 1500 mg/L biopolymer solutions, and the changes of apparent viscosity with mineralization were determined at 20 °C, 55 °C, and 90 °C, as shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, with a shear rate of 7.34 s

-1. Moreover,

Figure 10 shows the curve of viscosity retention φ of the biopolymer solution as a function of mineralization at 90 °C.

It can be seen that at these three temperatures, when the mineralization of the biopolymer solution was increased from 6 g/L to 220 g/L, the apparent viscosity of the diutan gum solution essentially remained unchanged and remained high, and the viscosity retention φ was still maintained at 90.12% at 90 °C; the apparent viscosity of the scleroglucan solution was slightly decreased, and the viscosity retention φ was 70.04% at 90 °C; moreover, the apparent viscosity of the xanthan gum solution The apparent viscosity of xanthan gum solution decreased more definitely from 47.42 mPa·s to 11.57 mPa·s, and the viscosity retention rate φ was only 24.40% at 90°C.

Diutan gum and xanthan gum are polyelectrolytes that are polyanionic in aqueous solution [

29,

37,

38]. In the case of anionic polyelectrolytes, the cations (Na

+, Ca

2+, and Mg

2+) in the simulated brine serve two main roles, shielding the electrostatic repulsion between the charged groups of the macromolecules, causing the macromolecules to adopt a more compact conformation, and densifying the hydration layer around the biopolymer molecules, both of which negatively roles lead to a decrease in the apparent viscosity of the solution [

2,

29,

39]. The side chains of the diutan gum molecules are entangled inside the main chains, and the shielding effect of inorganic cations is limited, which has no effect on the water molecules wrapped in the core of the double helix; on the contrary, xanthan gum has a disordered conformation in pure water or low concentration simulated brine, and as the mineralization level increases, xanthan gum starts to show an ordered conformation due to the charge shielding effect, and, according to the study of Long Xu, the presence of inorganic salts did not alter the viscoelastic properties of diutan gum. The viscoelastic properties of diutan gum are still dominated by the elastic component, while the dynamic modulus of xanthan gum decreases, indicating that the solution of diutan gum has a better resistance to high salt [

2]. Scleroglucan is a nonionic water-soluble biopolymer produced by

sclerotium rolfsii [

40], moreover, due to its peculiar rigid triple-helix rod structure, the molecules in scleroglucan solutions are virtually independent of the ionic environment, and thus are insensitive to mineralization [

29,

41].

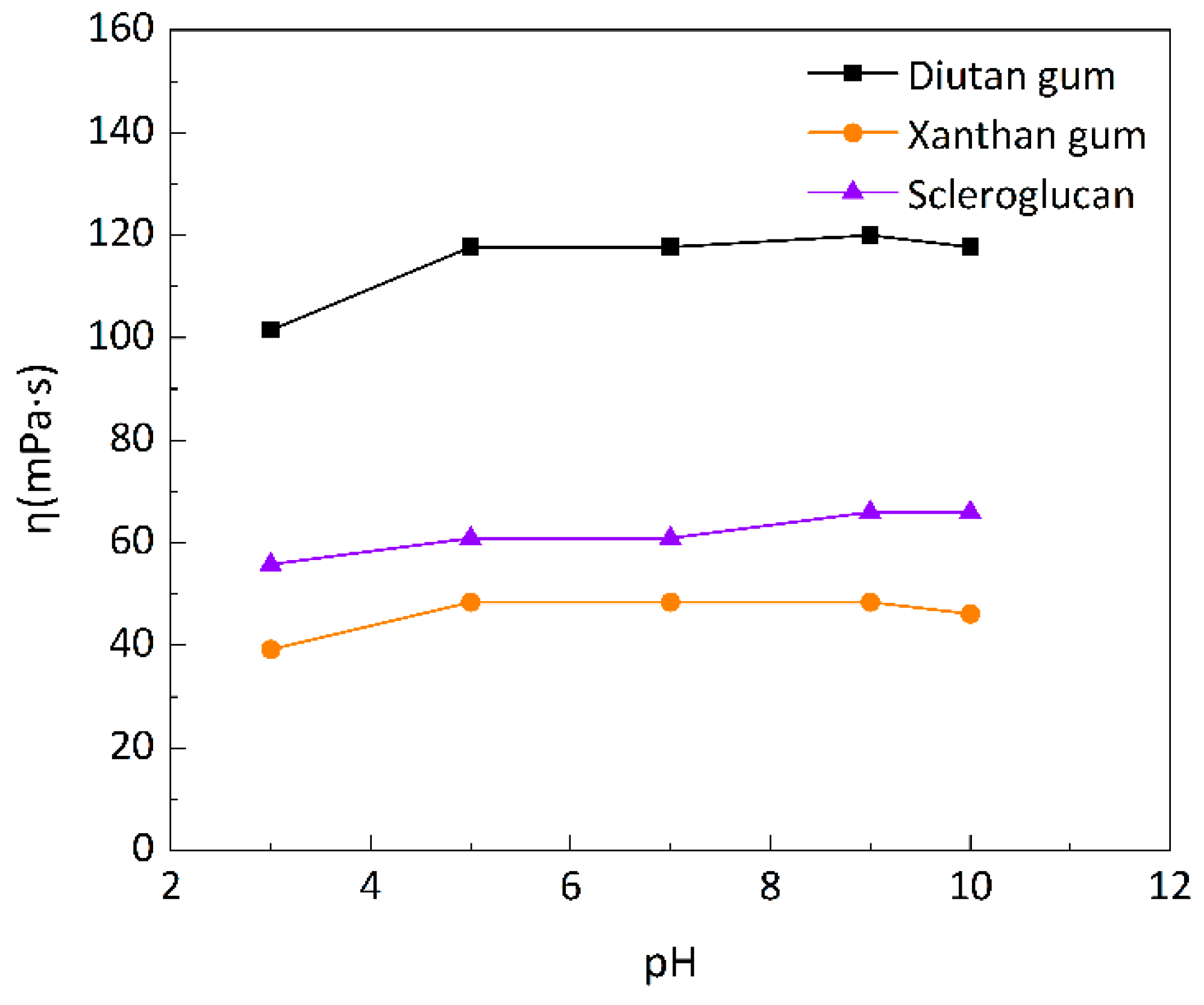

3.1.4. Comparison of acid and alkali resistance of three biopolymers

Most of the reservoirs are in a neutral environment, but the gas flooding in tertiary oil recovery, especially CO

2 flooding, will change the reservoir’s acid-base environment, making the reservoir in acidic environment, and some fields use alkali flooding or ternary composite flooding, making the reservoir in alkaline environment, so it is essential to study the effect of pH on the apparent viscosity of the biopolymer solutions. Simulated brines with mineralization of 6g/L at different pH were prepared to formulate the three biopolymer solutions, and the apparent viscosities of the biopolymer solutions at 90°C were shown in

Figure 11, which showed that the apparent viscosities of the three biopolymer solutions were almost unchanged in the pH range of 5-7 and that the apparent viscosities of the three biopolymer solutions decreased to different degrees in a more acidic environment, among which, xanthan gum solution decreased to a large extent (19.05%), followed by diutan gum and scleroglucan; in alkaline environment, the apparent viscosity of scleroglucan solution slightly increased (up 8.34%), diutan gum solution was stable, and the apparent viscosity of xanthan gum solution slightly decreased, which was due to the destruction of xanthan gum part of the intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding by the strong alkali [

13,

42]. Diutan gum and scleroglucan solution viscosity was not much affected by alkali concentration. It can be used in a wide range of alkali concentrations and can be used in oil fields to improve oil recovery by compounding with alkali.

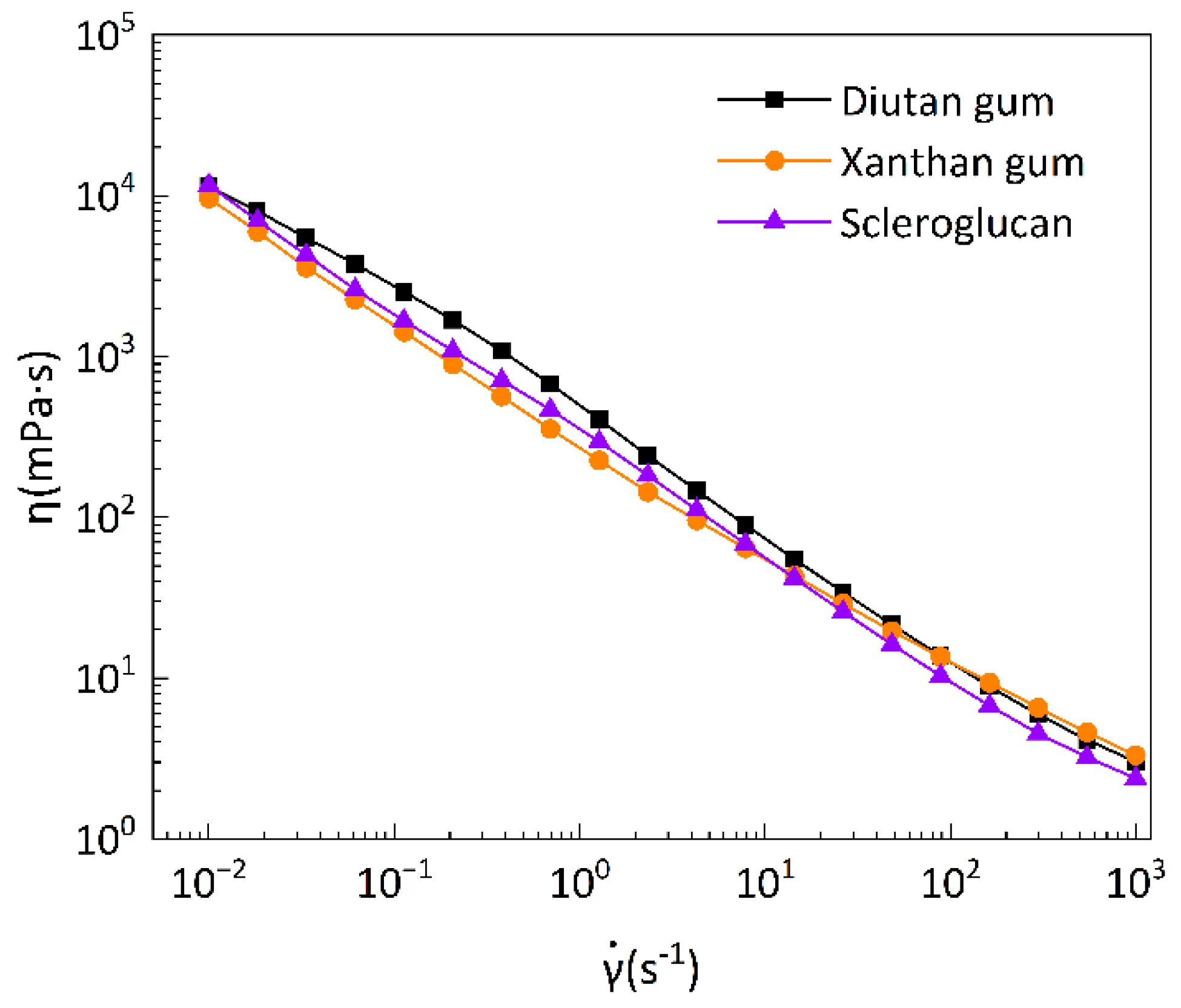

3.2. Rheological properties of three biopolymers

3.2.1. Steady-state rheological shear test

Steady-state rheological shear tests were performed on the biopolymer solutions, and

Figure 12 was obtained as the flow curves of the biopolymer solutions at a temperature of 90 °C (with shear rates in the range of 0.01-1000 s

-1), comparing the apparent viscosity of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan solutions as a function of shear rate. It can be seen that, at elevated temperatures, the apparent viscosities of all three biopolymer solutions decreased with shear rate increase and showed a strong shear thinning behavior, which is an obvious pseudoplastic fluid behavior. At the same time, the apparent viscosities of the three biopolymer solutions do not differ greatly at high shear rates (greater than 100 s

-1), and the apparent viscosities of diutan gum and scleroglucan solutions are higher than that of xanthan gum solution at low shear rates (less than 100 s

-1). This is due to the fact that this shear-thinning property is closely related to the state of molecular aggregation or dispersion in the shear flow [

43]. Biopolymer molecules normally exist as aggregates at low shear rates, and when the shear rate increases, the aggregates gradually dissociate under shear and the individual molecules rearrange themselves along the direction of flow, and the result is a decrease in apparent viscosity, and the molecular weights of diutan gum and scleroglucan are larger relative to those of xanthan gum, which can exhibit higher viscosities at low shear rates [

3,

44].

Table 2 shows the parameters of the power-law model for the apparent viscosity versus shear rate of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan solutions at 90 °C. The power-law model fits well (R

2>0.99) the pseudoplastic behavior of xanthan gum, diutan gum, and scleroglucan solutions in the range of shear rates from 0.01 to 1000 s

-1, while the power-law model has been used numerous times by other researchers to fit the relationship between apparent viscosity and shear rate of biopolymer solutions [

2,

28,

39,

41,

45,

46]. As shown in

Table 2, the power rate exponent n of all three is less than 1, still showing pseudoplastic fluid behavior, and the consistency exponent k of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution is larger than that of xanthan gum solution, as shown in

Figure 12, the apparent viscosity of diutan gum and hard scleroglucan solution is higher compared with that of xanthan gum solution, and the strengths of thickening performances of the three are as follows: diutan gum>scleroglucan>xanthan gum.

3.2.2. Linear viscoelastic zone LVR test

The dynamic rheological test of biopolymer solution is to better reflect its structure. The methods commonly used to examine the structure of the solutions are to test them with oscillatory amplitude scans and oscillatory frequency scans. The oscillation amplitude scanning is first used to determine the linear visco-elastic region LVR of biopolymer solutions because, in general, the appropriate strain applied by oscillation frequency scanning must be within the linear visco-elastic region [

39,

47].

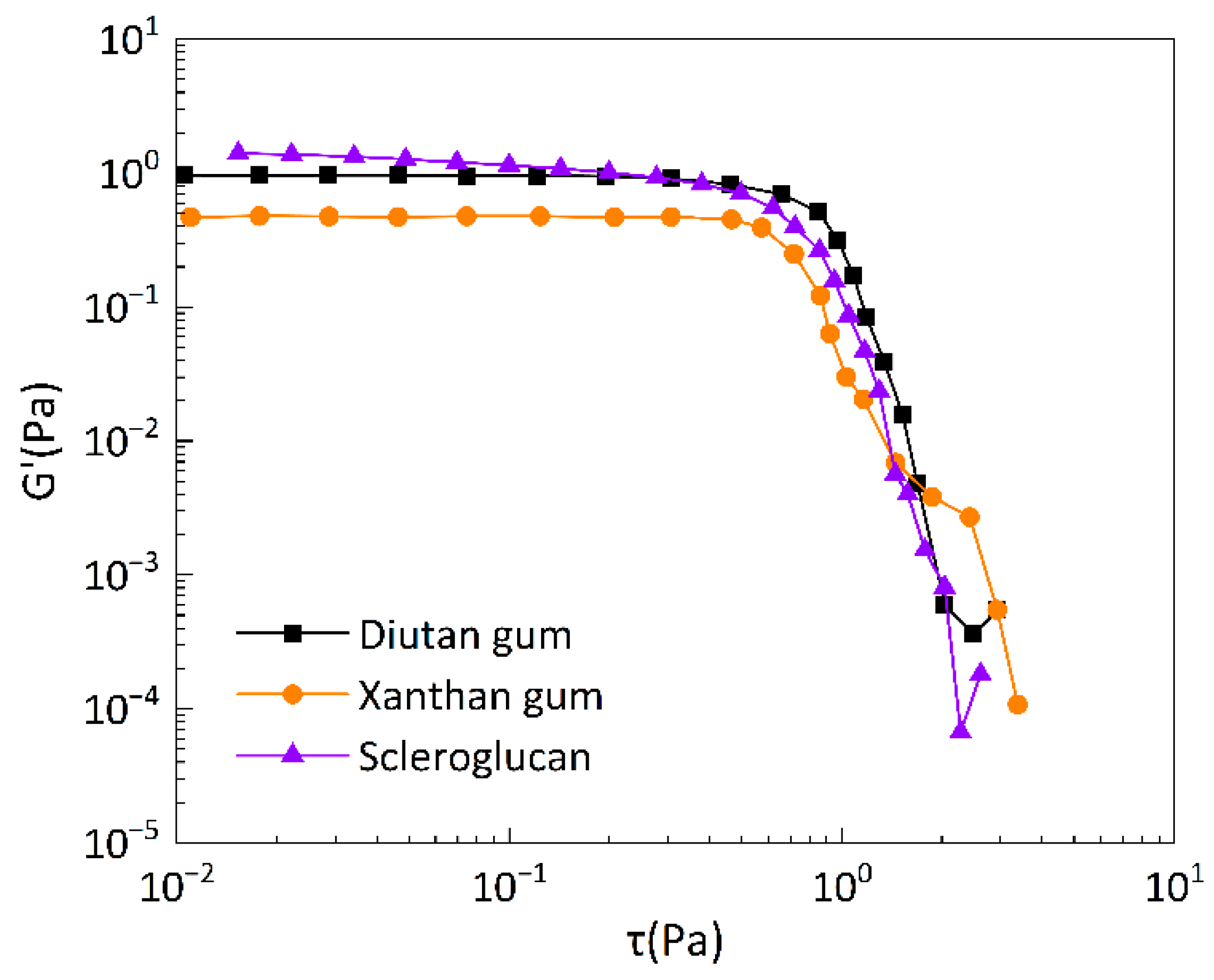

A high plateau of elastic modulus G’ independent of shear stress τ or shear strain is considered to be the linear viscoelastic region. The linear viscoelastic regions of the three biopolymer solutions are shown in

Figure 13, which shows that a linear viscoelastic region exists for diutan gum, scleroglucan, and xanthan gum, and the modulus of elasticity, G’, remains virtually constant with increasing shear stress, τuntil it reaches the critical stress value, τ

c (τ

c, the stress at the inflection point). The critical stress value τ

c reflects the shear resistance of the molecular agglomerates, and the initial molecular agglomerates are destroyed when τ >τ

c. The critical stress value τ

c of the solution is large, the molecular chains overlap and entangle with each other and can withstand greater shear stress, so the more excellent viscoelastic properties[

39]. The plateau values of diutan gum and scleroglucan solutions are higher than xanthan gum, and the critical stress value τc is also higher than xanthan gum, which indicates that the viscoelasticity of diutan gum and scleroglucan solutions is more prominent compared with xanthan gum, and they can withstand larger stresses.

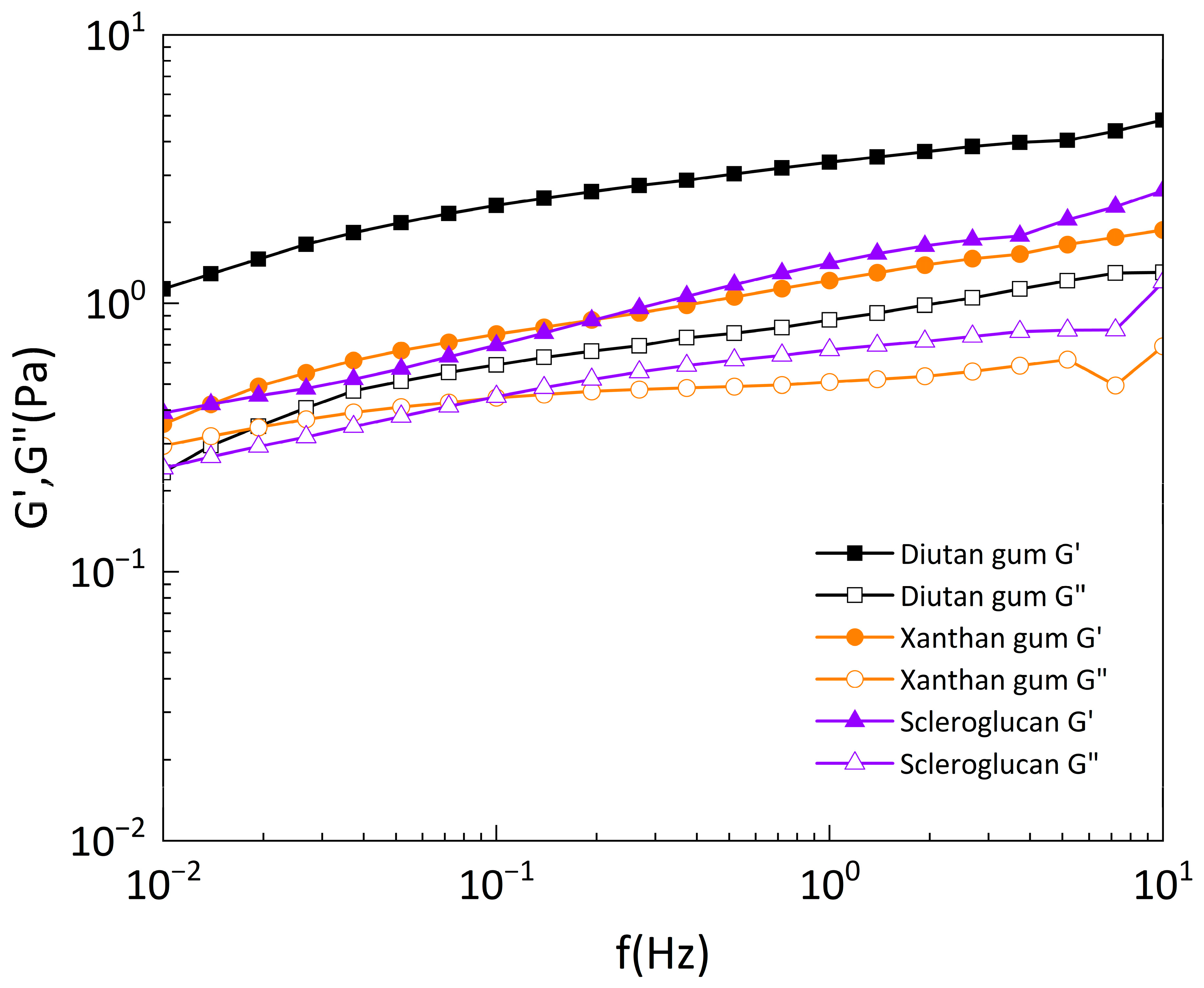

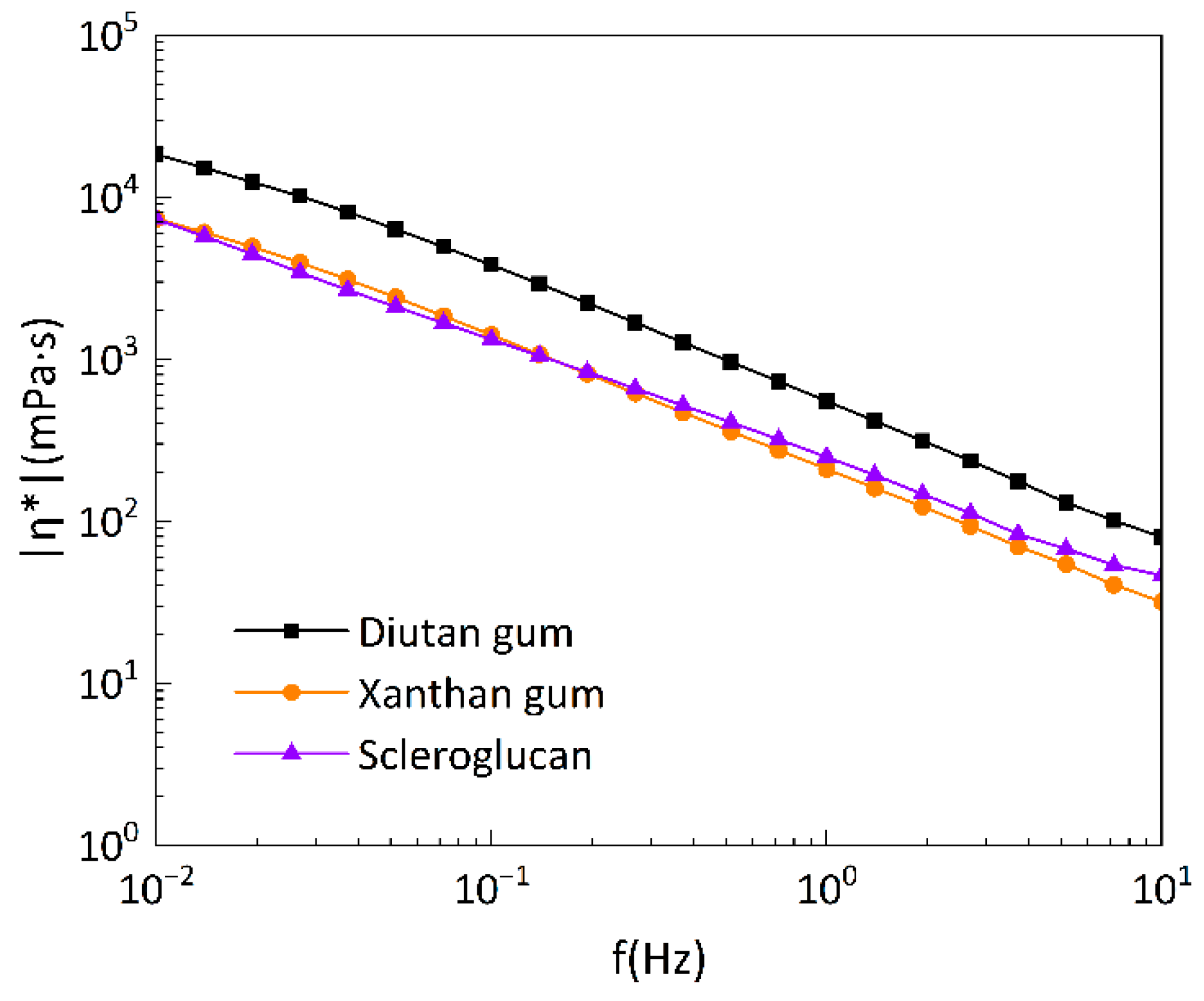

3.2.3. Oscillation frequency sweep test

Figure 14 exhibits the dynamic modulus (i.e., storage modulus G’ and loss modulus G”) of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan solutions versus the oscillation frequency at a temperature of 90°C and 0.1 Pa shear stress. The three biopolymer solutions show a gradual increase in oscillation frequency. At a concentration of 1500mg/L, the storage modulus G’ of all three biopolymers was greater than the loss modulus G”, and the storage modulus G’ and loss modulus G” of diutan gum were greater than those of xanthan gum and scleroglucan, indicating that the viscoelasticity of the solutions was dominated by the elastic component, and the viscoelasticity of diutan gum was better than that of xanthan gum and scleroglucan. It can also be seen from

Figure 14 that the overlap frequency (the frequency corresponding to the intersection of G’ and G”) of xanthan gum and scleroglucan is considerably larger than that of diutan gum, which shows a typical naturally ordered structure. Another feature of this structure is the strong frequency dependence of the dynamic modulus [

2].

Figure 15 shows the relationship between the complex viscosity and the oscillation frequency of the three under the same conditions, and it can be seen that the complex viscosity of diutan gum is also higher than that of xanthan gum and scleroglucan.

Under the concentration of 1500 mg/L, diutan gum shows greater viscoelasticity than xanthan gum and scleroglucan, which is due to the formation of a stronger network structure in the solution of diutan gum. The molecules of diutan gum possess a distinct double helix structure, and its side chains are all distributed in the center of the double-helix main chain so that a large number of water molecules can enter into the inner part of the double-helix structure, and attach themselves to the side chains through hydrogen bonding. In contrast, those of xanthan gum and scleroglucan solutions are only enhanced by intermolecular and intramolecular forces without network structure, which is also similar to the studies of Ke Liang et al. [

2,

29]. Therefore, diutan gum has strong water retention and viscoelastic properties.

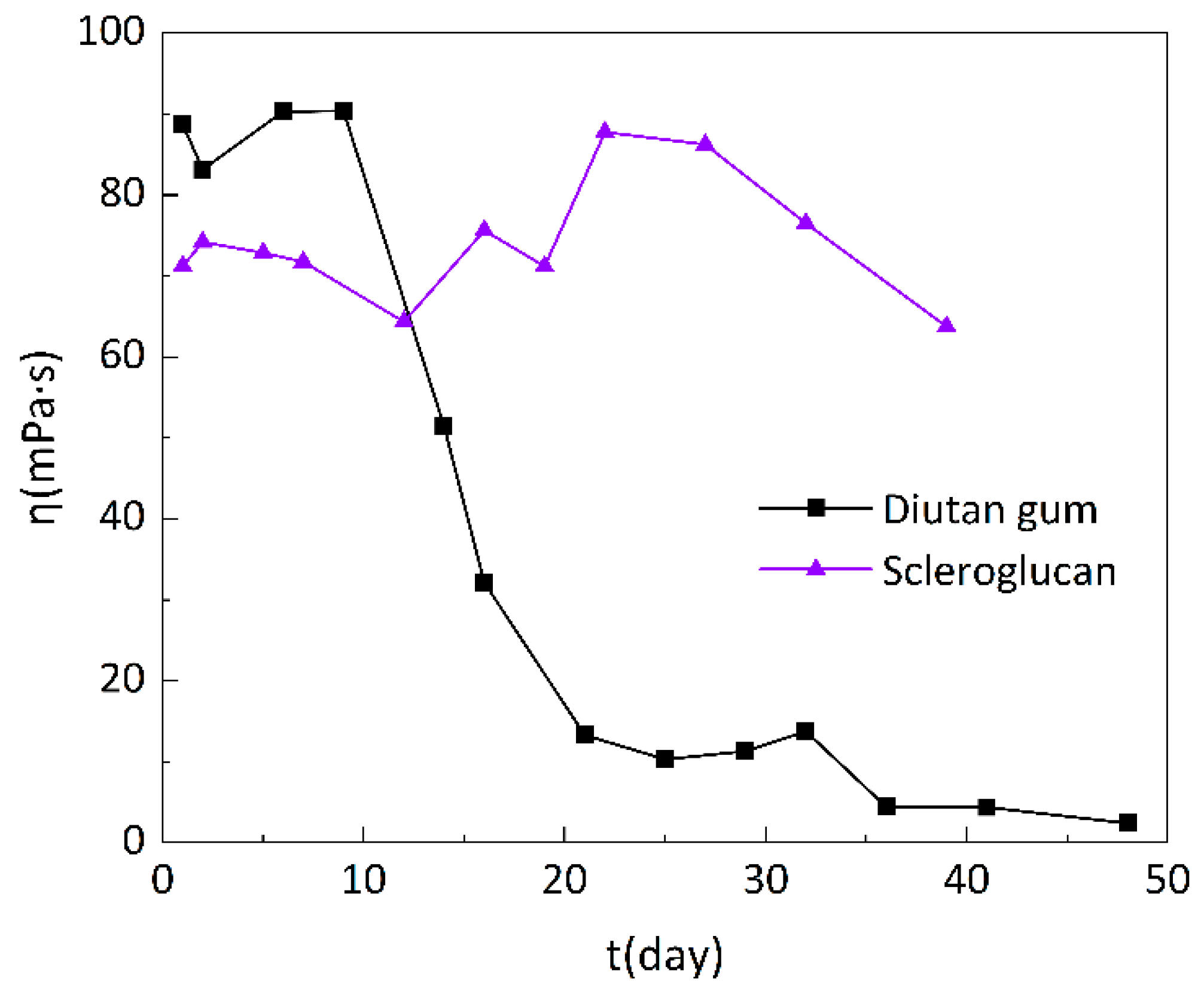

3.3. Long-term stability of diutan gum and scleroglucan

The biopolymer has been in an anaerobic, high-temperature environment during the months-long oil flood in the formation. To test whether biopolymer solutions can maintain sufficient apparent viscosity, aging needs to be simulated in an anaerobic, high-temperature ambient system. A 1500mg/L solution of diutan gum and scleroglucan with a mineralization of 220g/L was prepared, and the samples were loaded and taken in a glove box after designation, and then placed in an oven at 100°C to carry out the evaluation of the long-term thermal stability performance, and to determine the change in apparent viscosity of the biopolymer solution with the aging time.

As can be seen in

Figure 16, the apparent viscosity of the diutan gum solution remained relatively stable in the first 10 days of aging, which was always around 90 mPa·s, but in the period from 10 to 21 days, the apparent viscosity decreased substantially, and on the 21st day, only 13.3 mPa·s was left, with a loss of 85.01% of apparent viscosity, and in the period from 21 to 32 days, the apparent viscosity was maintained at around 12 mPa·s. After 32 days, the apparent viscosity dropped to single digit and gave off a “caramel” odor. The apparent viscosity of scleroglucan solution did not change much in the first 20 days of aging, remaining at about 70 mPa·s, and rose slightly from 20 to 39 days, and on the 39th day, the apparent viscosity was still 63.76 mPa·s, with a loss rate of only 10.46%.

From the above results, it can be obtained that the diutan gum has certain long-term stability of temperature and salt resistance, and it can be kept stable for about 10 days at 100°C and 220g/L mineralization degree, after which, the structure of diutan gum began to change, the intermolecular hydrogen bonding weakened, and the molecular chain began to break, thus the apparent viscosity decreased considerably; On the contrary, the long-term stability of scleroglucan is better than that of diutan gum, which can be maintained at 100°C and 220g/L mineralization for about 40 days, which is mainly attributed to its rigid triple helix structure.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigate the viscosity enhancement, rheological, and long-term stability properties of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan in simulated extreme reservoir environments. The results are as follows:

(1) At the same temperature and mineralization degree, the thickening and viscosity increasing performance of diutan gum are better than that of xanthan gum and scleroglucan, and the amount of diutan gum required to achieve the same apparent viscosity is lower than that of xanthan gum and scleroglucan.

(2) Diutan gum and scleroglucan showed better temperature resistance than xanthan gum. Diutan gum can withstand a maximum temperature of 100 °C, with the apparent viscosity retention rate of 89%; scleroglucan temperature stability up to 150 °C, apparent viscosity retention rate of 118.27%.

(3) Diutan gum and scleroglucan showed better salt resistance than xanthan gum, and both of them could tolerate up to 220 g/L mineralized simulated brine, with 90.12% apparent viscosity retention of diutan gum and 70.04% of scleroglucan, with minor apparent viscosity loss. The acid and alkali resistance of the three biopolymer solutions was relatively excellent, with a slight decrease in apparent viscosity under heavily acidic conditions and an approximately constant apparent viscosity under alkaline conditions.

(4) In the rheological test, the solutions of diutan gum, xanthan gum, and scleroglucan all distinctly showed pseudoplastic fluid behavior, and the diutan gum had strong water retention and viscoelastic properties due to the peculiar double helix structure.

(5) Both diutan gum and scleroglucan have certain long-term stability of temperature and salt resistance. diutan gum can remain stable for about 10 days at 100°C and 220g/L mineralization, and the apparent viscosity is maintained at 90 mPa·s. Scleroglucan can remain stable for approximately 40 days in the same reservoir environment, with an apparent viscosity retention rate of 89.54%.

Comprehensively analyzing the temperature, salt, acid, and alkali resistance, and long-term stability of the three biopolymers, it is concluded that scleroglucan is more tolerant to the extreme conditions of the reservoir and has the best potential for drive modulation applications.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, L.H., and J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, X.G., L.Y., and Y.Z.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This work was supported by the China National Petroleum Corporation Scientific Research and Technology Development Project (No. 2021DJ1605).

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot

be shared at this time, as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, W.M.; Yu, L.; Xiu, J.L.; Yi, L.N.; Huang, L.X.; Peng, B.F. Research progress on application of biopolymer in petroleum industry. Applied Chemical Industry 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Gong, H.J.; Dong, M.Z.; Li, Y.J. Rheological properties and thickening mechanism of aqueous diutan gum solution: Effects of temperature and salts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.C.; Carmona, J.A.; Santos, J.; Alfaro, M.C.; Munoz, J. Effect of temperature and shear on the microstructure of a microbial polysaccharide secreted by Sphingomonas species in aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.; Jan, B.M. Herschel-Bulkley rheological parameters of a novel environmentally friendly lightweight biopolymer drilling fluid from xanthan gum and starch. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2012, 124, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaimon, A.A.; Akintola, S.A.; Johari, M.A.B.M.; Isehunwa, S.O. Evaluation of drilling muds enhanced with modified starch for HPHT well applications. Journal of Petroleum Exploration and Production Technology 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.B.; Belhadri, M. Rheological properties of biopolymers drilling fluids. Journal of Petroleum Science & Engineering 2009, 67, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C. Potential of Welan Gum as mud thickener. 2014.

- Luz, R.C.S.D.; Fagundes, F.P.; Balaban, R.D.C. Water-based drilling fluids: the contribution of xanthan gum and carboxymethylcellulose on filtration control. Chemical Papers- Slovak Academy of Sciences 2017, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.X.; Zhang, L.B.; Davletshin, A.; Li, Z.R.; You, J.H.; Tan, S.Y. Application of Polysaccharide Biopolymer in Petroleum Recovery. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, J.C.; Wang, S.B.; Wang, C. Research status and development trend of high temperature resistant fracturing fluid system. Modern Chemical Industry 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Quraishi, M.; Bhatia, S.K.; Pandit, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Rangarajan, V.; Lahiri, D.; Varjani, S.; Mehariya, S.; Yang, Y.H. Exploiting Microbes in the Petroleum Field: Analyzing the Credibility of Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery (MEOR). Energies 2021, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Hu, S.Y.; Jin, Y. China achieving carbon neutral in 2060, fossil energy to fossil resource era. Modern Chemical Industry 2021, 41, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.T. Properties of novel microbial polysaccharides suitable for the polymer flooding of harsh oil reservoirs. Oil Drilling & Production Technology 2019, 41, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Qiu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhong, H.; Dai, W. Novel hydrophobic associated polymer based nano-silica composite with core–shell structure for intelligent drilling fluid under ultra-high temperature and ultra-high pressure. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Tan, Y.; Che, Y.; Ma, Q. Synthesis of copolymer of acrylamide with sodium vinylsulfonate and its thermal stability in solution. Journal of Polymer Research 2011, 18, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccormick, C.L.; Nonaka, T.; Johnson, C.B. Water-soluble copolymers: 27. Synthesis and aqueous solution behaviour of associative acrylamideN-alkylacrylamide copolymers. Polymer 1988, 29, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei-Long, F.U.; Jie, L. Characterization of the structure of comb-like polymer comb-1. Journal of Xi’an Shiyou University(Natural Science Edition) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.H. , Zhiyu. Self-assembly and regulation of hydrophobic associating polyacrylamide with excellent solubility prepared by aqueous two-phase polymerization. Colloids and Surfaces, A. Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2018, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Shi, R.; Cui, Q.; Han, S.; Dong, H.; Zhang, Y. Biosurfactant production under diverse conditions by two kinds of biosurfactant-producing bacteria for microbial enhanced oil recovery. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2017, 157, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.J.; Banat, I.M.; Joshi, S.J. Biosurfactants: Production and potential applications in microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Cai, Y.; Yan, Y.; Gao, M. Research progress on novel chemical oil displacement technology. Modern Chemical Industry 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.B. Measures to Improve Tertiary Oil Recovery. Chemical Engineering & Equipment 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.S. Basis and progress of microbial oil recovery; 2005.

- Zhang, X.F.; Gao, Y.W.; Wang, B.L.; Qin, C.W. A preliminary study on the feasibility of biopolymer modulation drive technology for Weyland gums. Drilling & Production Technology 2019, 42, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Clinckspoor, K.J.; Ferreira, V.; Moreno, R. Bulk rheology characterization of biopolymer solutions and discussions of their potential for enhanced oil recovery applications. CT y F - Ciencia, Tecnologia y Futuro 2021, 11, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N.J.; Wen, Y.P.; Yang, Z.D.; Chen, J.L.; Zhao, X.B.; Wang, D.D.; He, W.; Chen, Y.M. Polymer flooding in high-temperature and high-salinity heterogeneous reservoir by using diutan gum. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 188, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George; Holzwarth. Molecular weight of xanthan polysaccharide. Carbohydrate Research 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mota, G.P.; Pereira, R.G. A comparison of the rheological behavior of xanthan gum and diutan gum aqueous solutions. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Han, P.; Chen, Q.; Su, X.; Feng, Y. Comparative Study on Enhancing Oil Recovery under High Temperature and High Salinity: Polysaccharides Versus Synthetic Polymer. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 10620–10628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annable; Tom. The rheology of solutions of associating polymers: Comparison of experimental behavior with transient network theory. Journal of Rheology 1993, 37, 695–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristofer; Modig; Bernd; G. ; Pfrommer; Bertil; Halle. Temperature-Dependent Hydrogen-Bond Geometry in Liquid Water. Physical Review Letters 2003, 90, 75502–75502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Xu, X.J. Recent Progress in Chain Conformation and Function of Triple Helical Polysaccharides. journal of Founctional Polymers 2016, 29, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M. Structures and properties of scleroglucan. Oilfield Chemistry 1993, 10, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, P.; Keilhofer, G. Xanthan Gum and Scleroglucan - How both differ at elevated temperatures. Oil Gas European Magazine 2004, 30, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Nok, C.; Lecourtier, J. Studies on scleroglucan conformation by rheological measurements versus temperature up to 150°C. Polymer 1993, 34, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakci, B.J., Y.Magri, N.Padolewski, J. Thermal stability of scleroglucan at realistic reservoir conditions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SPE/DOE Enhanced Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 1990.

- Sun, L.; Wei, P.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, D. Research advance of xanthan system with temperature resistance and salt resistant in the oilfield development. Applied Chemical Industry 2014, 43, 2279. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, P.; Mukherjee, I.; Bhattacharya, S.; Datta, S.; Moulik, S.P.; Sarkar, D. Sorption of water vapor, hydration, and viscosity of carboxymethylhydroxypropyl guar, diutan, and xanthan gums, and their molecular association with and without salts (NaCl, CaCl2, HCOOK, CH3COONa, (NH4)2SO4 and MgSO4) in aqueous solution. Langmuir 2009, 25, 11647–11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Gong], H. The comparison of rheological properties of aqueous welan gum and xanthan gum solutions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, J.I.; Sineriz, F.; Molina, O.E.; Perotti, N.I. Isolation and physicochemical characterization of soluble scleroglucan from Sclerotium rolfsii. Rheological properties, molecular weight and conformational characteristics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 44, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiran, L. Application of Biopolymer to Improve Oil Recovery in High Temperature High Salinity Carbonate Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Wu, W.D.; Wang, Y.Q.; Li, Y.J.; Shi, W.R. Study on the effect of pH on the rheological properties of xanthan gum solutions. Farm Machinery 2012, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, B.S.; Jr, D.L.P.M.; Haag, R.B.; Souza, C.R.D.; Lucas, E.F. Evaluation of hydrophobically associated polyacrylamide-containing aqueous fluids and their potential use in petroleum recovery. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2004, 91, 3686–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Gong, H.; Ding, B.; Dong, M.; Li, Y. A Microbial Exopolysaccharide Produced by Sphingomonas Species for Enhanced Heavy Oil Recovery at High Temperature and High Salinity. Energy & Fuels 2017, 31, 3960–3969. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte, M.; Hoshahili, A.R.T.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Rheological properties of selected hydrocolloids as a function of concentration and temperature. Food Research International 2001, 34, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.J.; Li, D.; ?Zkan, N.; Li, S.J.; Mao, Z.H. Rheological properties of waxy maize starch and xanthan gum mixtures in the presence of sucrose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.G.; Zhao, L.; Dai, G.C. Rheological Properties of Xanthan Gum Solutions. Journal of East China University of Science and Technology (Natural Science Edition) 2011, 37, 4. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Change curves of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with concentration at 20 °C (a) and 90 °C (b).

Figure 1.

Change curves of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with concentration at 20 °C (a) and 90 °C (b).

Figure 2.

Change Curve of Biopolymer Solution Concentration with Apparent Viscosity at 90 °C.

Figure 2.

Change Curve of Biopolymer Solution Concentration with Apparent Viscosity at 90 °C.

Figure 3.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with temperature at shear rate of 7.34s−1.

Figure 3.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with temperature at shear rate of 7.34s−1.

Figure 4.

Apparent viscosity retention rate (φ) of biopolymer solution at different temperatures under a shear rate of 7.34s−1.

Figure 4.

Apparent viscosity retention rate (φ) of biopolymer solution at different temperatures under a shear rate of 7.34s−1.

Figure 5.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with temperature at shear rate of 250s−1.

Figure 5.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with temperature at shear rate of 250s−1.

Figure 6.

Apparent viscosity retention rate (φ) of biopolymer solution at different temperatures under a shear rate of 250s −1.

Figure 6.

Apparent viscosity retention rate (φ) of biopolymer solution at different temperatures under a shear rate of 250s −1.

Figure 7.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 20 °C.

Figure 7.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 20 °C.

Figure 8.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 55 °C.

Figure 8.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 55 °C.

Figure 9.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 90 °C.

Figure 9.

Curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution changing with salinity at 90 °C.

Figure 10.

Curve of viscosity retention rate φ of biopolymer solution changing with salinity degree at 90 °C.

Figure 10.

Curve of viscosity retention rate φ of biopolymer solution changing with salinity degree at 90 °C.

Figure 11.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with pH at 90 °C.

Figure 11.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with pH at 90 °C.

Figure 12.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with shear rate at 90 °C.

Figure 12.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of biopolymer solution with shear rate at 90 °C.

Figure 13.

Oscillation amplitude scanning curve of biopolymer solution at 90 °C and 1Hz frequency.

Figure 13.

Oscillation amplitude scanning curve of biopolymer solution at 90 °C and 1Hz frequency.

Figure 14.

The relationship between the elastic modulus G ′ and viscous modulus G ” of biopolymer solution and the oscillation frequency under 90 °C and 0.1 Pa shear stress.

Figure 14.

The relationship between the elastic modulus G ′ and viscous modulus G ” of biopolymer solution and the oscillation frequency under 90 °C and 0.1 Pa shear stress.

Figure 15.

Relationship curve between complex viscosity and oscillation frequency of biopolymer solution under shear stress of 90 °C and 0.1 Pa.

Figure 15.

Relationship curve between complex viscosity and oscillation frequency of biopolymer solution under shear stress of 90 °C and 0.1 Pa.

Figure 16.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution with aging time.

Figure 16.

Change curve of apparent viscosity of diutan gum and scleroglucan solution with aging time.

Table 1.

Simulated brine composition.

Table 1.

Simulated brine composition.

| Composition(g/L) |

Total Mineralization(g/L) |

| NaCl |

CaCl2

|

MgCl2·6H2O |

| 192.5 |

16.5 |

11 |

220 |

| 148.75 |

12.75 |

8.5 |

170 |

| 70 |

6 |

4 |

80 |

| 21.875 |

1.875 |

1.25 |

25 |

| 13.125 |

1.125 |

0.75 |

15 |

| 5.3 |

0.45 |

0.3 |

6 |

Table 2.

Power law model parameters of biopolymer solution at 90 °C.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

<1000

<1000 <1000

<1000 <1000

<1000