Submitted:

08 October 2023

Posted:

08 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Brief Review of LE, LLE and HLLE

2.1. LE

2.2. LLE

2.3. HLLE

3. Proposed Method

3.1. FLML: Fused Local Manifold Learning

3.2. FLML based Fault Detection

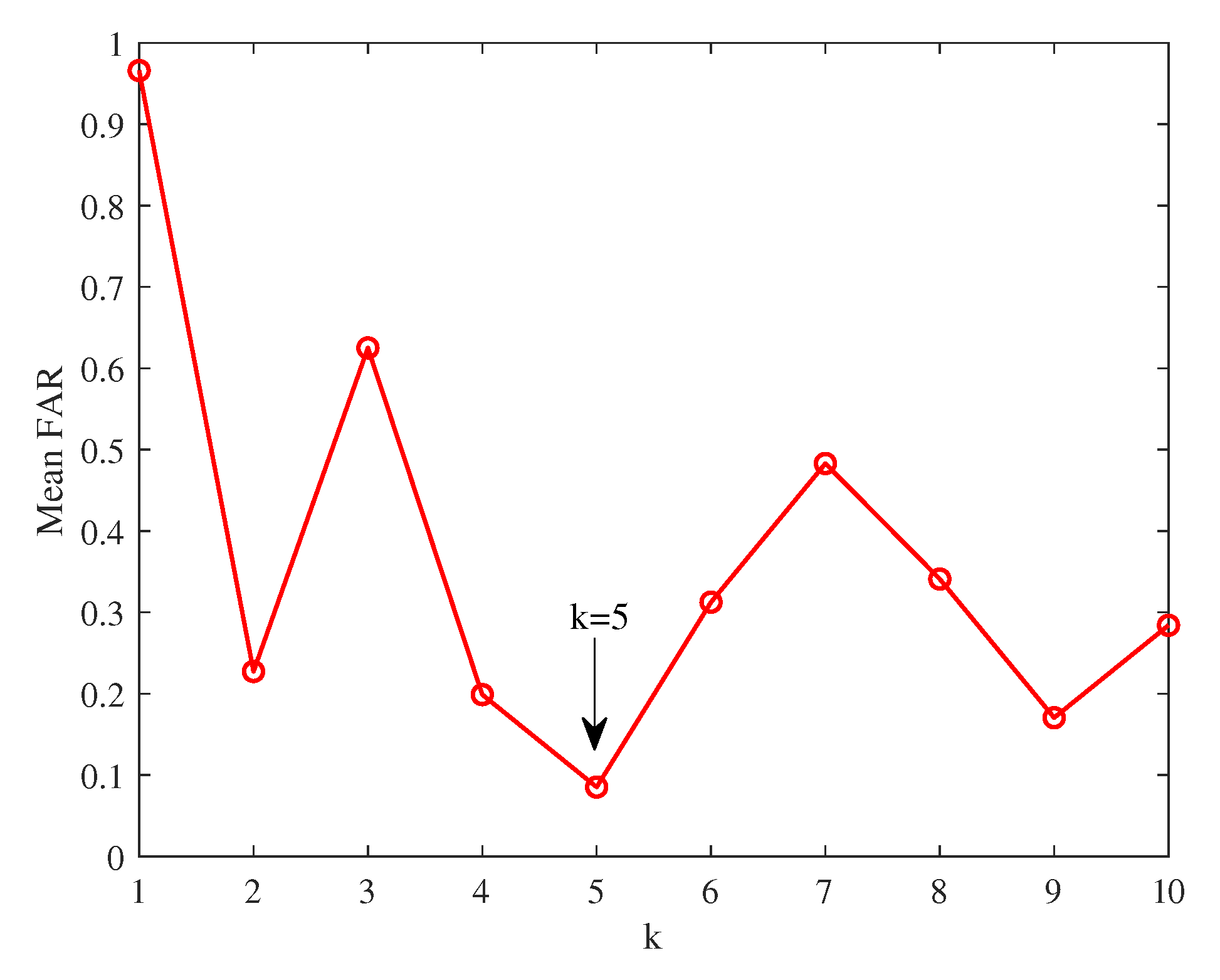

- k: The finding of neighborhood relation is related to the selection of k [23]. To balance the computation complexity and generalization capability, we choose k in the range with the smallest mean false alarm rate (FAR). The definition of FAR can be found in next section.

- : If the bandwidth of the Gaussian heat kernel function is too small, the kernel will be sensitive to noise. A large bandwidth may create an overly smooth mapping [28]. Empirically, the bandwidth is chosen as where m is the size of variables, b is a constant, and represents the variance of the data, which is 1 as the original data is normalized [22]. In the case studies, are selected.

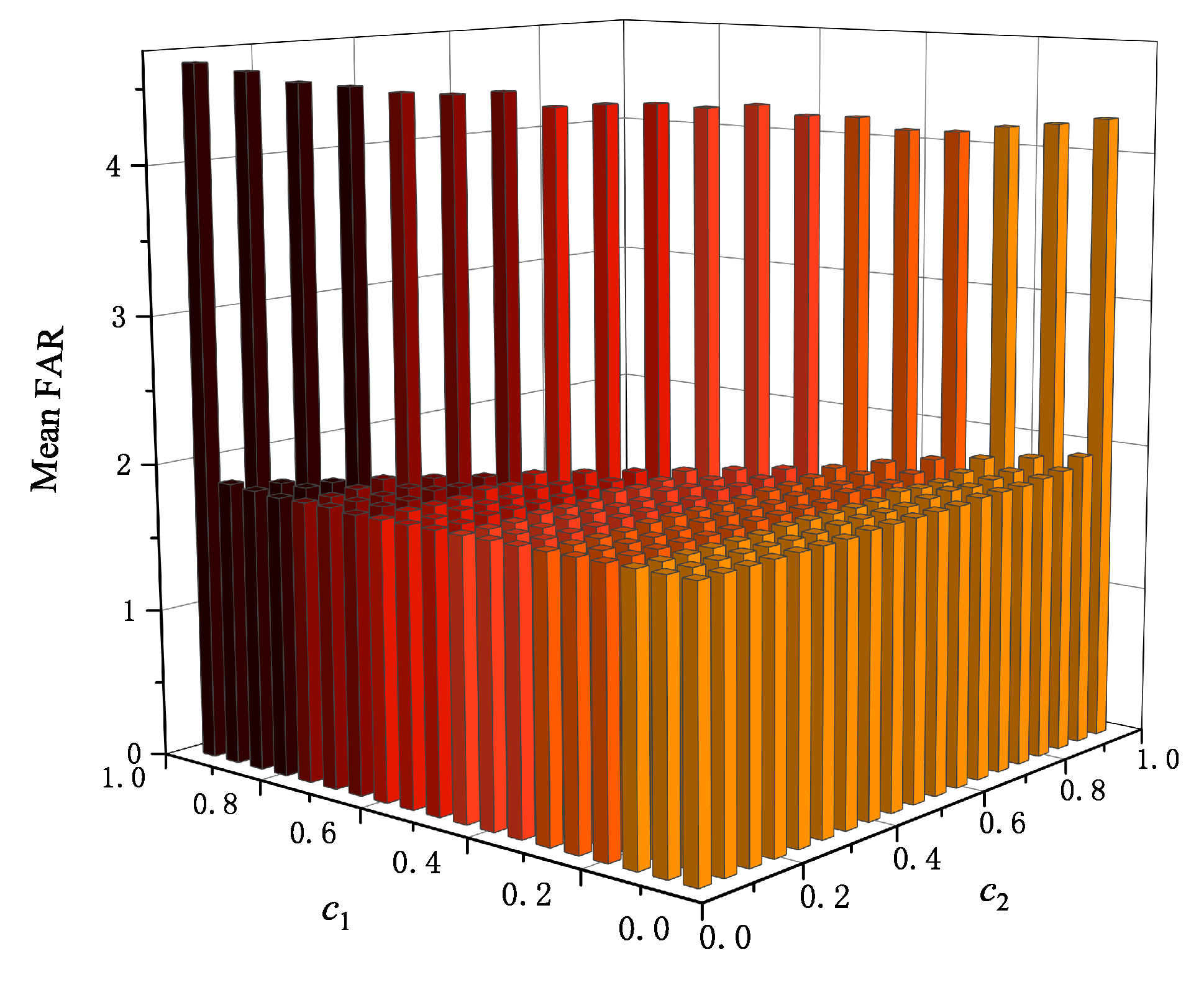

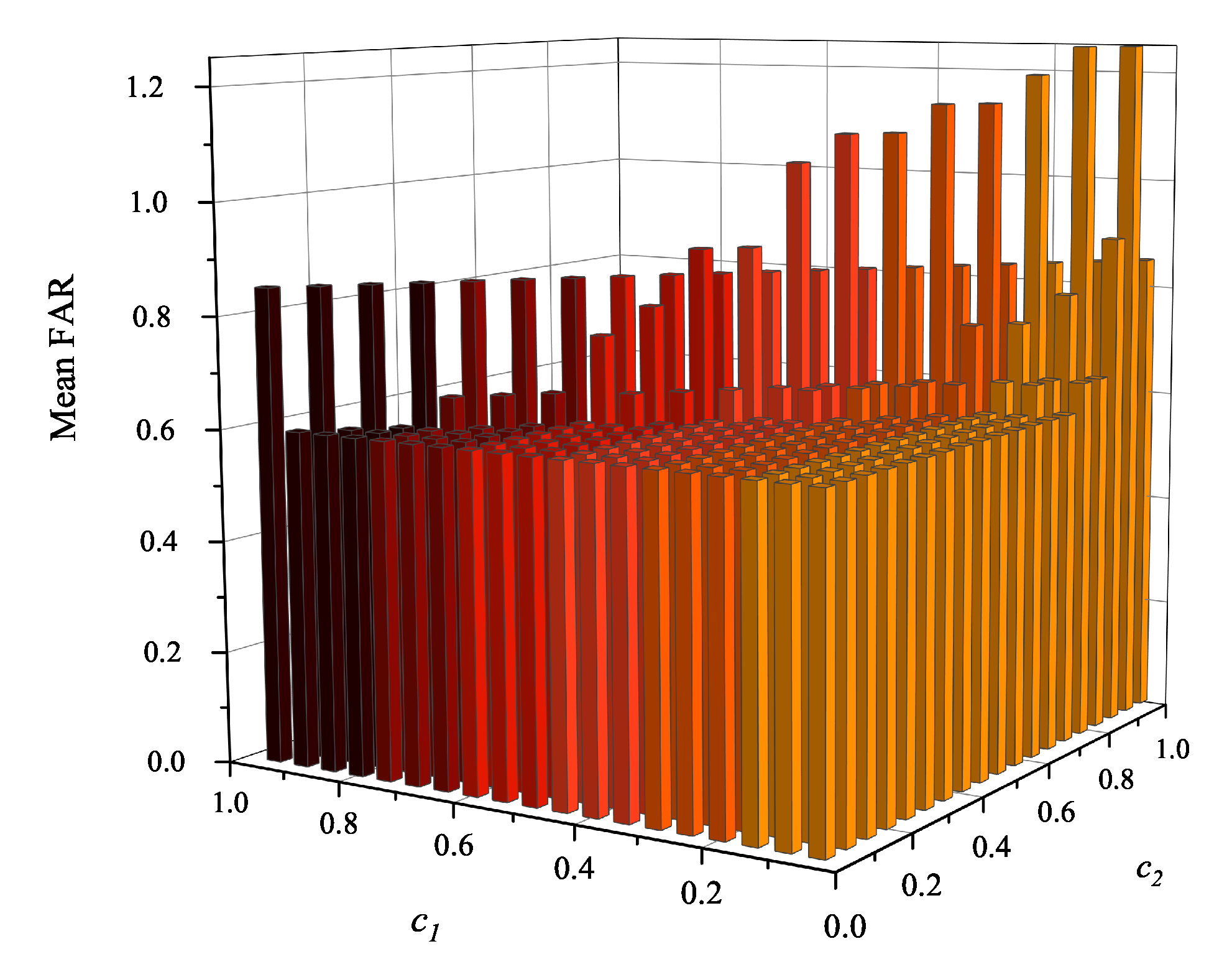

- and : It is noticeable that the hyper-parameters and have a important influence on the performance of the proposed FLML method. However, it is a challenging work to choose a set of optimal hyper-parameters. As a traditional way of performing hyper-parameter optimization, the grid search method is employed. For this purpose, a finite set of and are explored by minimizing the mean FAR.

- d: Similar to NPE-based and LPP-based methods, the number of latent variables d is selected by searching for eigenvalues similar to the smallest non-zero eigenvalue.

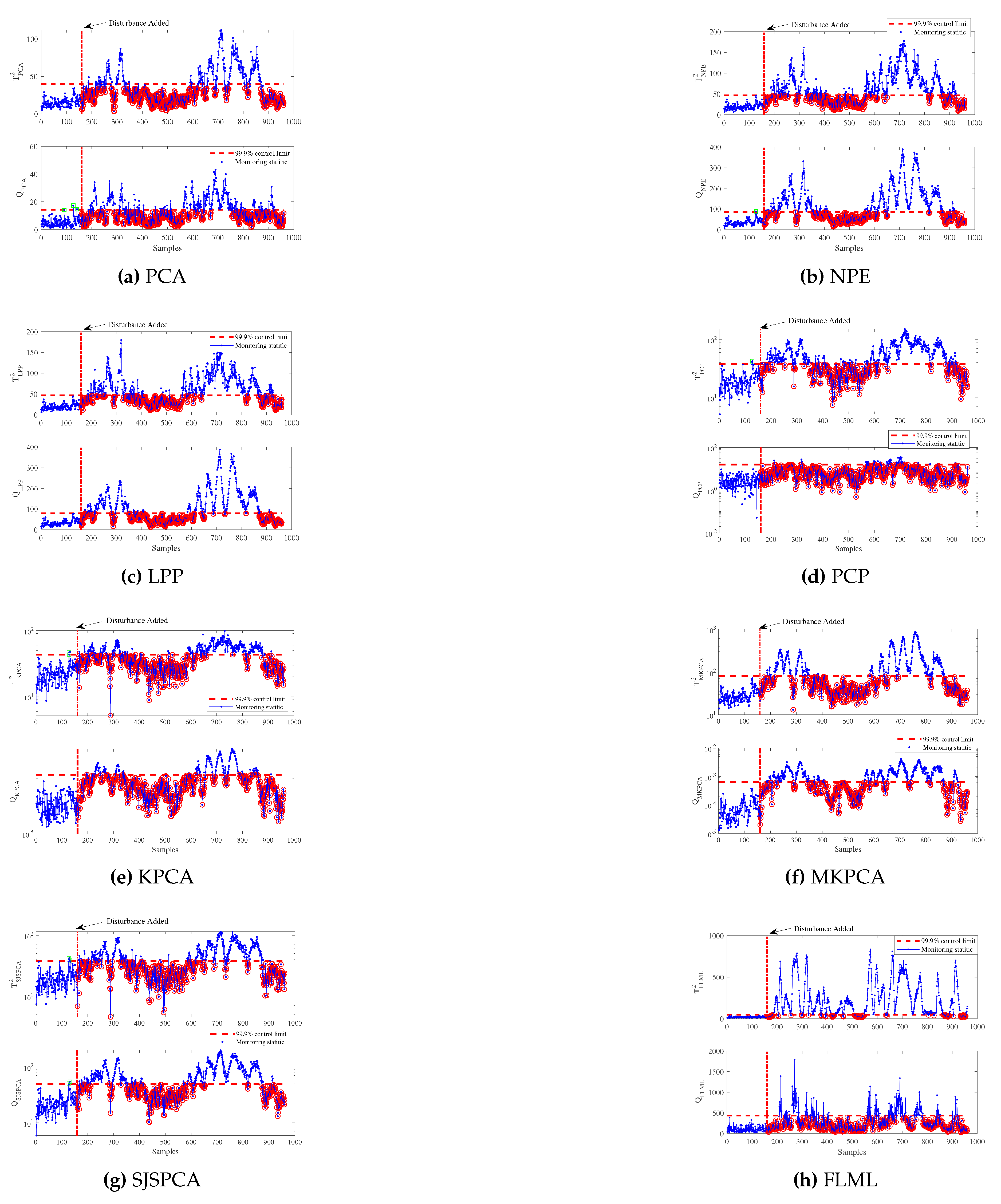

4. Case Studies

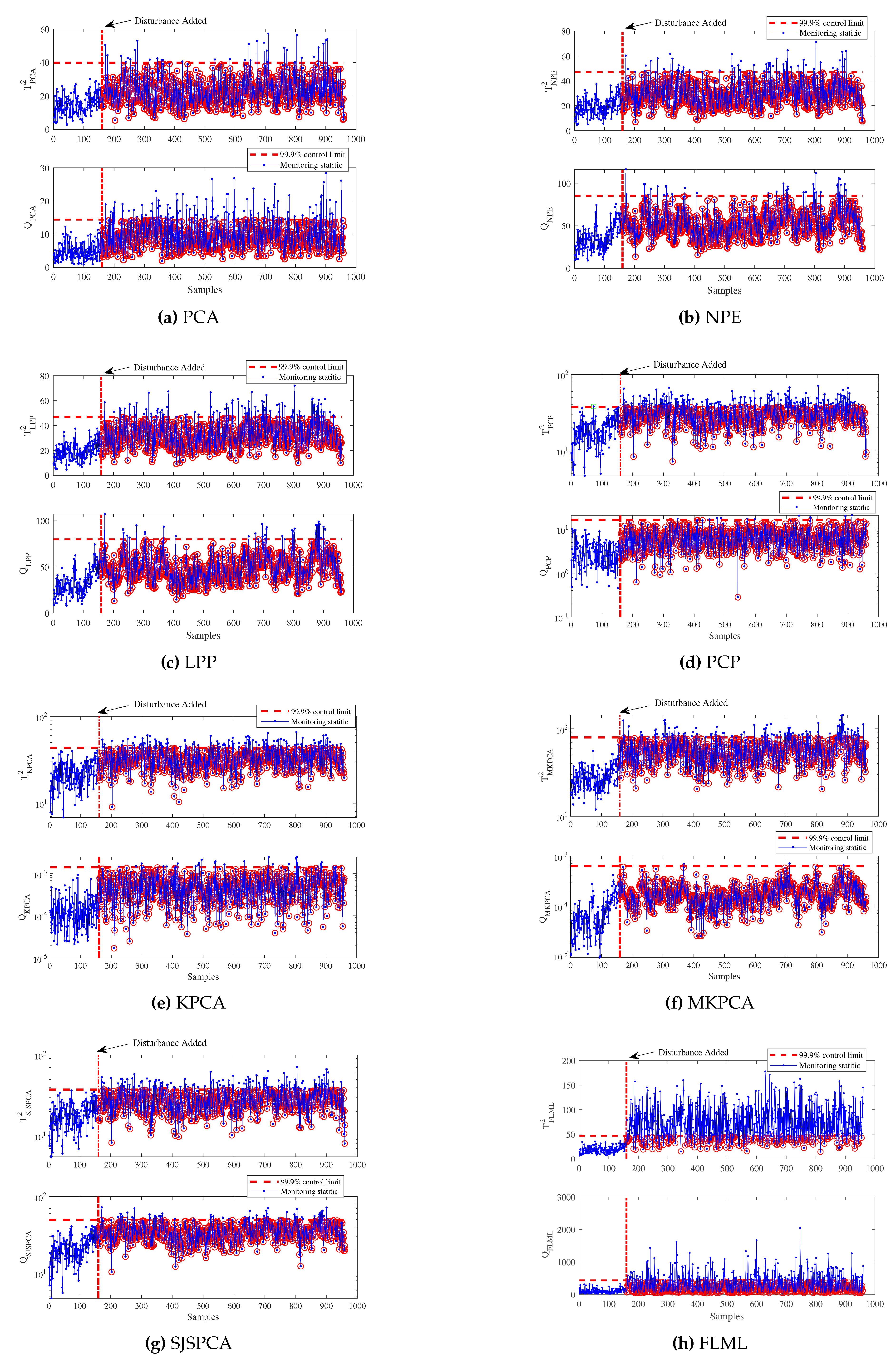

4.1. Tennessee Eastman Process

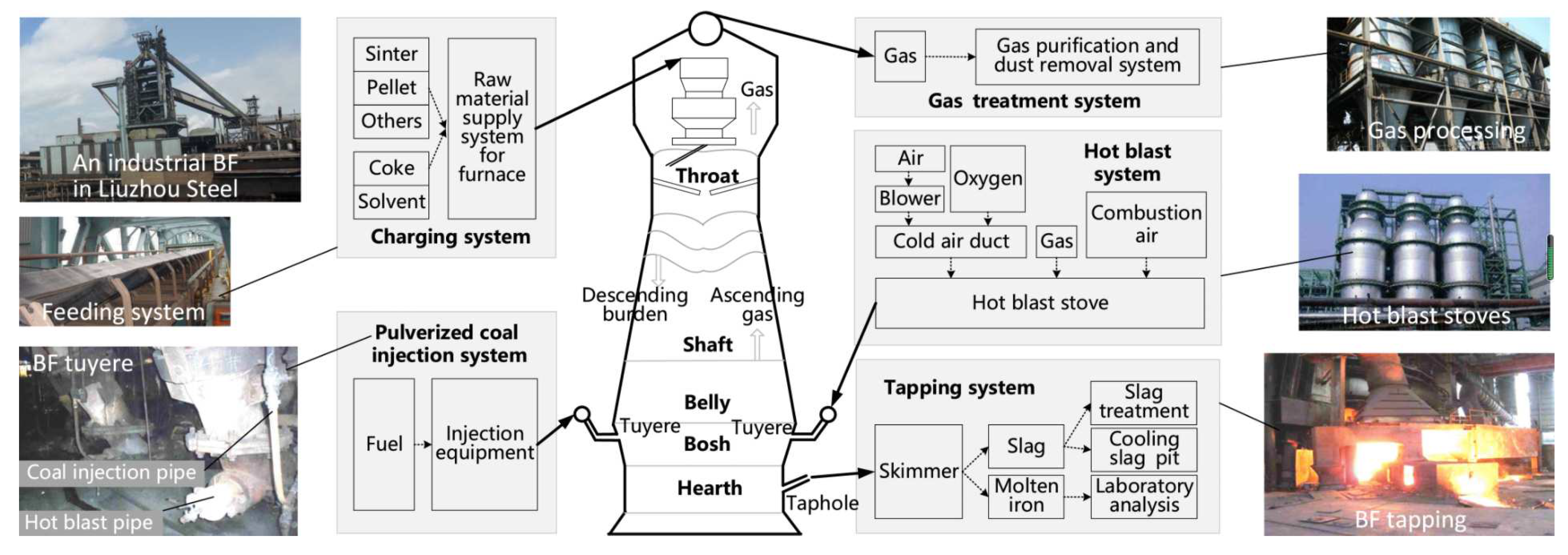

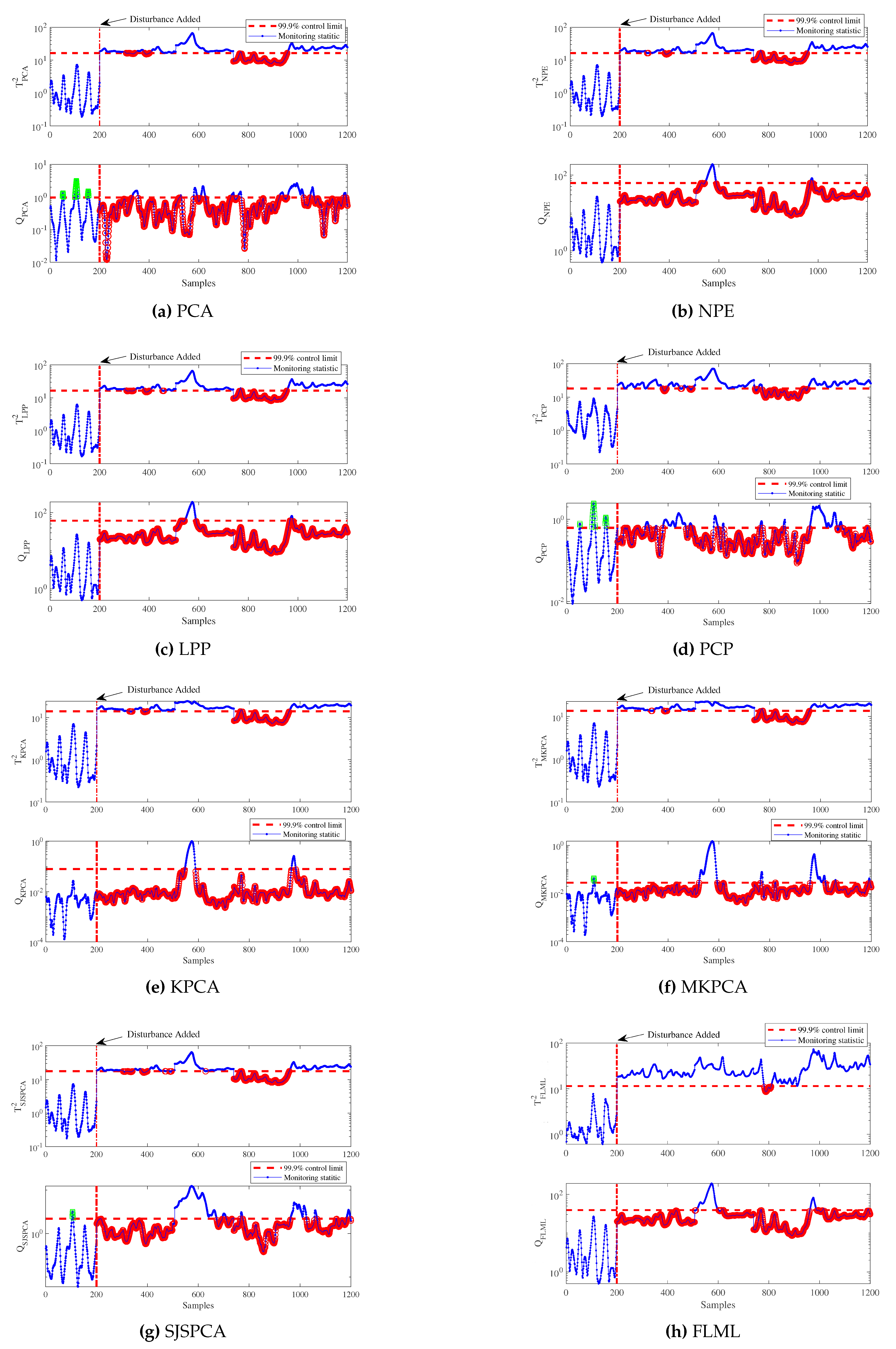

4.2. Blast Furnace Ironmaking Process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Bahr, N.J. System safety engineering and risk assessment: a practical approach; CRC press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.; Rathnayaka, S.; Ahmed, S. Methods and models in process safety and risk management: Past, present and future. Process safety and environmental protection 2015, 98, 116–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.; Khan, F.; Iqbal, M.T. Real-time fault diagnosis using knowledge-based expert system. Process safety and environmental protection 2008, 86, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, V.; Rengaswamy, R.; Yin, K.; Kavuri, S.N. A review of process fault detection and diagnosis: Part I: Quantitative model-based methods. Computers & chemical engineering 2003, 27, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidriri, K.; Chatti, N.; Verron, S.; Tiplica, T. Bridging data-driven and model-based approaches for process fault diagnosis and health monitoring: A review of researches and future challenges. Annual Reviews in Control 2016, 42, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Gao, Z. From model, signal to knowledge: A data-driven perspective of fault detection and diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2013, 9, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ding, S.X.; Xie, X.; Luo, H. A review on basic data-driven approaches for industrial process monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 61, 6418–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.J.; Chiang, L.H. Advances and opportunities in machine learning for process data analytics. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2019, 126, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Ding, S.X.; Haghani, A.; Hao, H.; Zhang, P. A comparison study of basic data-driven fault diagnosis and process monitoring methods on the benchmark Tennessee Eastman process. Journal of process control 2012, 22, 1567–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Qin, S.J. A novel dynamic PCA algorithm for dynamic data modeling and process monitoring. Journal of Process Control 2018, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Li, X.; Gao, H.; Kaynak, O. Data-based techniques focused on modern industry: An overview. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 62, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, J.B.; De Silva, V.; Langford, J.C. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. science 2000, 290, 2319–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roweis, S.T.; Saul, L.K. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction by locally linear embedding. science 2000, 290, 2323–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Laplacian eigenmaps for dimensionality reduction and data representation. Neural computation 2003, 15, 1373–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zha, H. Principal manifolds and nonlinear dimensionality reduction via tangent space alignment. SIAM journal on scientific computing 2004, 26, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Niyogi, P. Locality preserving projections. Advances in neural information processing systems 2004, 16, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Cai, D.; Yan, S.; Zhang, H.J. Neighborhood preserving embedding. In Proceedings of the Tenth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV’05) Volume 1, 2005; IEEE; Vol. 2, pp. 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Grimes, C. Hessian eigenmaps: Locally linear embedding techniques for high-dimensional data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 5591–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Jiang, B.; Chen, W. A modified neighborhood preserving embedding-based incipient fault detection with applications to small-scale cyber–physical systems. ISA transactions 2020, 104, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Ma, Y.; Shi, H. Multimode process monitoring using improved dynamic neighborhood preserving embedding. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 2014, 135, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, M.; Dong, M. A Metric-Learning-Based Nonlinear Modeling Algorithm and Its Application in Key-Performance-Indicator Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2019, 67, 7073–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ge, Z.; Song, Z.; Fu, R. Global–local structure analysis model and its application for fault detection and identification. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2011, 50, 6837–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Lou, S.; Zhang, X.; He, J.; Gao, J. Novel Quality-Relevant Process Monitoring based on Dynamic Locally Linear Embedding Concurrent Canonical Correlation Analysis. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2020, 59, 21439–21457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Supervised locally linear embedding projection (SLLEP) for machinery fault diagnosis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2011, 25, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, K.; Lv, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Du, S. Fusion of local manifold learning methods. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2014, 22, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Du, S.; Wang, K. Robust hessian locally linear embedding techniques for high-dimensional data. Algorithms 2016, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdek, J.C.; Hathaway, R.J. Some notes on alternating optimization. In Proceedings of the AFSS international conference on fuzzy systems. Springer; 2002; pp. 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-de Lázaro, J.; Llanes-Santiago, O.; Prieto-Moreno, A.; Knupp, D.; Silva-Neto, A. Enhanced dynamic approach to improve the detection of small-magnitude faults. Chemical Engineering Science 2016, 146, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.J.; Vogel, E.F. A plant-wide industrial process control problem. Computers & chemical engineering 1993, 17, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L.; Russell, E.; Braatz, R. Fault detection and diagnosis in industrial systems, 2001.

- Candès, E.J.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wright, J. Robust principal component analysis? Journal of the ACM (JACM) 2011, 58, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Yoo, C.; Choi, S.W.; Vanrolleghem, P.A.; Lee, I.B. Nonlinear process monitoring using kernel principal component analysis. Chemical engineering science 2004, 59, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Xie, L.; Luo, S.; Su, H. Structured joint sparse principal component analysis for fault detection and isolation. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 15, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ye, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, M. Process monitoring of iron-making process in a blast furnace with PCA-based methods. Control engineering practice 2016, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Chai, T. Data-driven monitoring and diagnosing of abnormal furnace conditions in blast furnace ironmaking: An integrated PCA-ICA method. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 68, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, M. Effective variable selection and moving window HMM-based approach for iron-making process monitoring. Journal of Process Control 2018, 68, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Fault description | Fault type |

| IDV(0) | Normal situations | - |

| IDV(1) | A/C feed ratio, B composition constant (Stream 4) | Step |

| IDV(2) | B composition, A/C ratio constant (Stream 4) | Step |

| IDV(4) | Reactor cooling water inlet temperature | Step |

| IDV(5) | Condenser cooling water inlet temperature | Step |

| IDV(6) | A feed loss (Stream 1) | Step |

| IDV(7) | C header pressure loss-reduced availability (Stream 4) | Step |

| IDV(8) | A, B, C feed composition (Stream 4) | Random variation |

| IDV(10) | C feed temperature (Stream 4) | Random variation |

| IDV(11) | Reactor cooling water inlet temperature | Random variation |

| IDV(12) | Condenser cooling water inlet temperature | Random variation |

| IDV(13) | Reaction kinetics | Slow drift |

| IDV(14) | Reactor cooling water valve | Sticking |

| IDV(16) | Unknown | Unknown |

| IDV(17) | Unknown | Unknown |

| IDV(18) | Unknown | Unknown |

| IDV(19) | Unknown | Unknown |

| IDV(20) | Unknown | Unknown |

| IDV(21) | Valve fixed at steady-state position | Constant position |

| No. | PCA | NPE | LPP | PCP | KPCA | MKPCA | SJSPCA | FLML | ||||||||

| Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | |||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aver. | ||||||||||||||||

| No. | PCA | NPE | LPP | PCP | KPCA | MKPCA | SJSPCA | FLML | ||||||||

| Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | |||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aver. | ||||||||||||||||

| No. | PCA | NPE | LPP | PCP | KPCA | MKPCA | SJSPCA | FLML | ||||||||

| Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | |||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | ||||||||||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||||||||||

| 14 | ||||||||||||||||

| 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 18 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aver. | ||||||||||||||||

| No. | Variable description | Unit |

| 1 | Oxygen enrichment rate | % |

| 2 | Enriching oxygen flow | |

| 3 | Hot blast temperature | C |

| 4 | Top temperature(1) | C |

| 5 | Top temperature(2) | C |

| 6 | Top temperature(3) | C |

| 7 | Downcomer temperature | C |

| PCA | NPE | LPP | PCP | KPCA | MKPCA | SJSPCA | FLML | ||||||||

| Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | Q | ||||||||

| a | |||||||||||||||

| b | |||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).