Submitted:

04 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

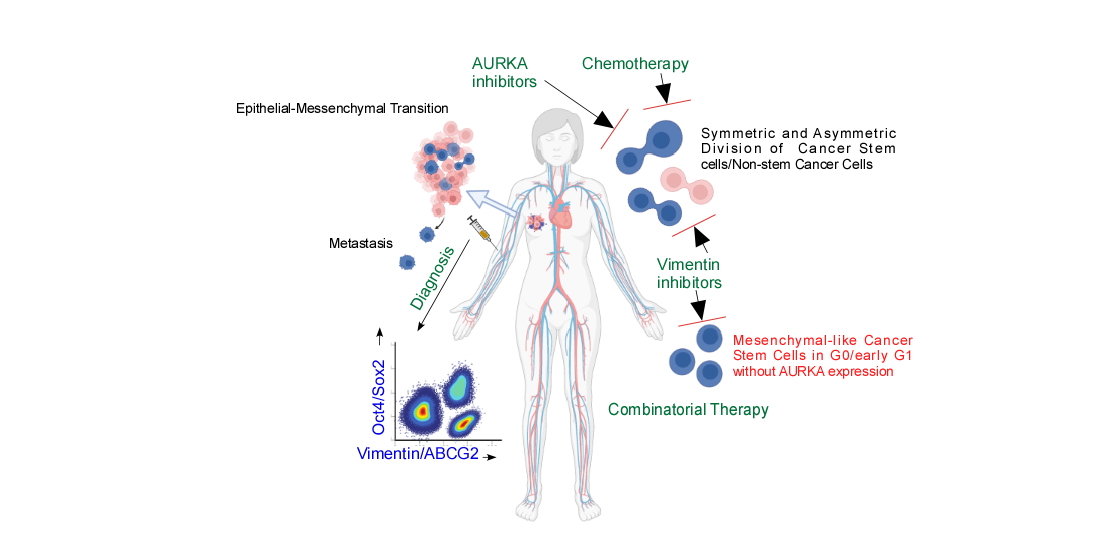

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

Results:

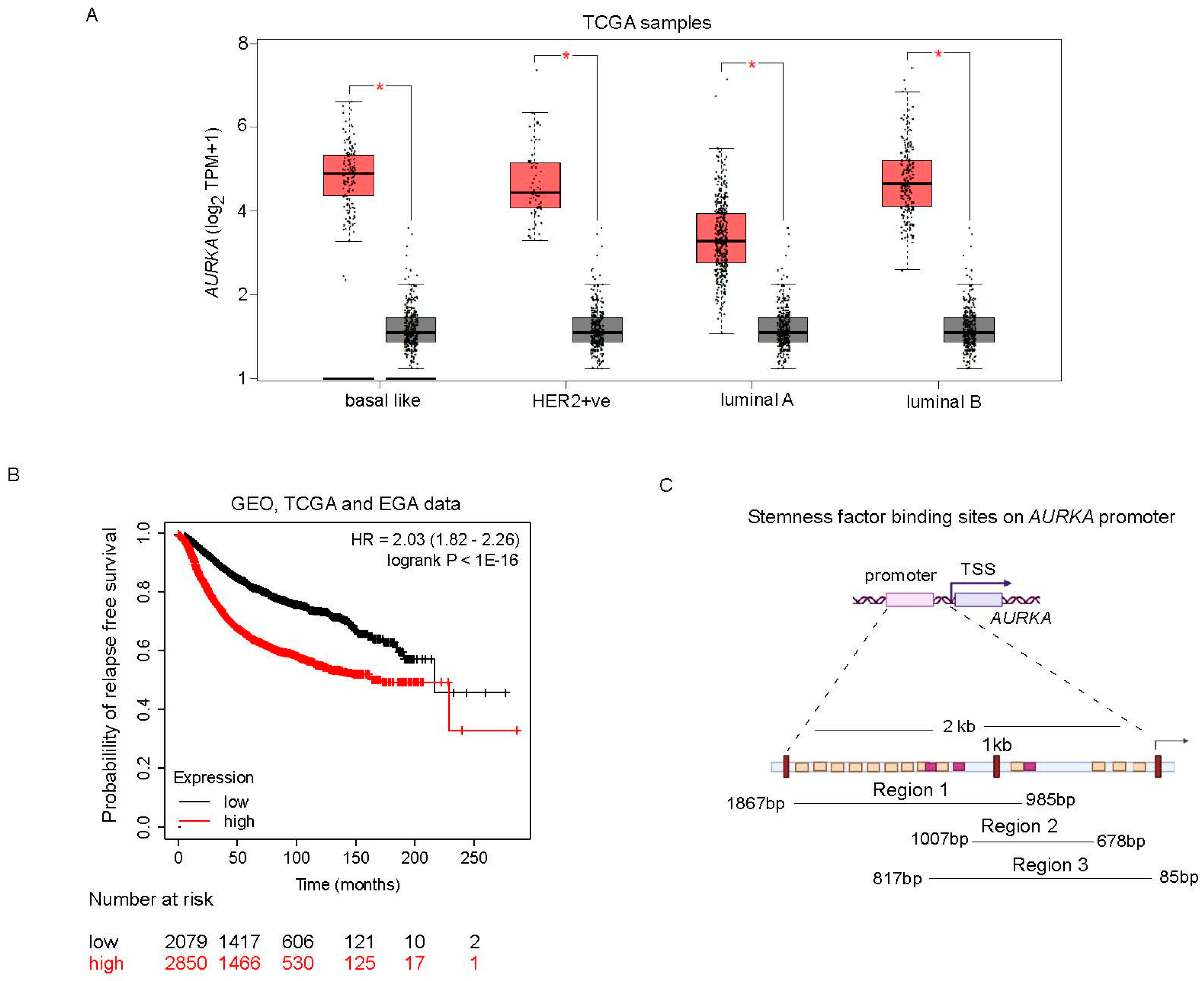

AURKA is transcriptionally upregulated and associated with relapse in breast cancer:

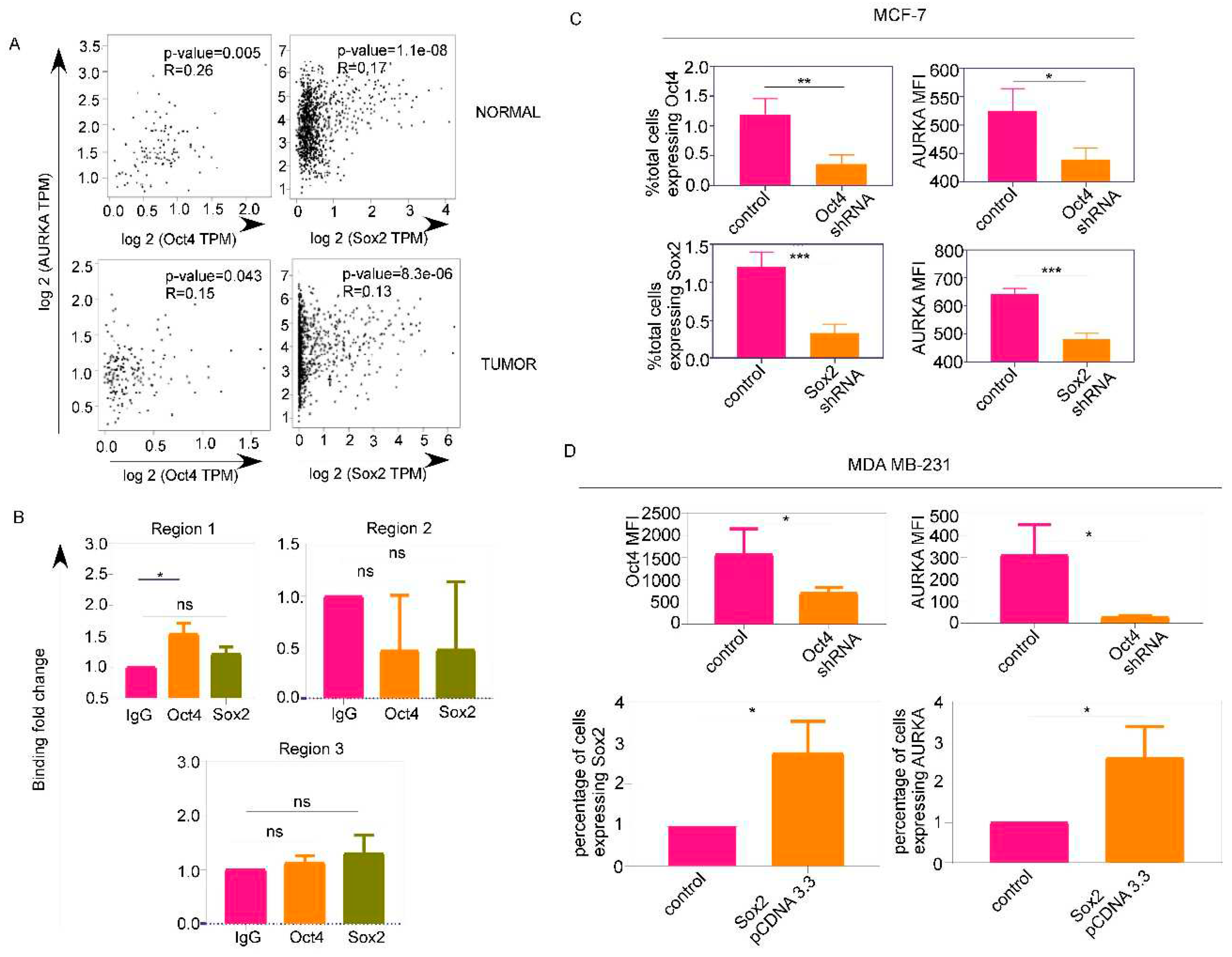

Oct4 and Sox2 regulate AURKA expression which colocalizes with drug-resistance marker ABCG2 and phospho-NUMB:

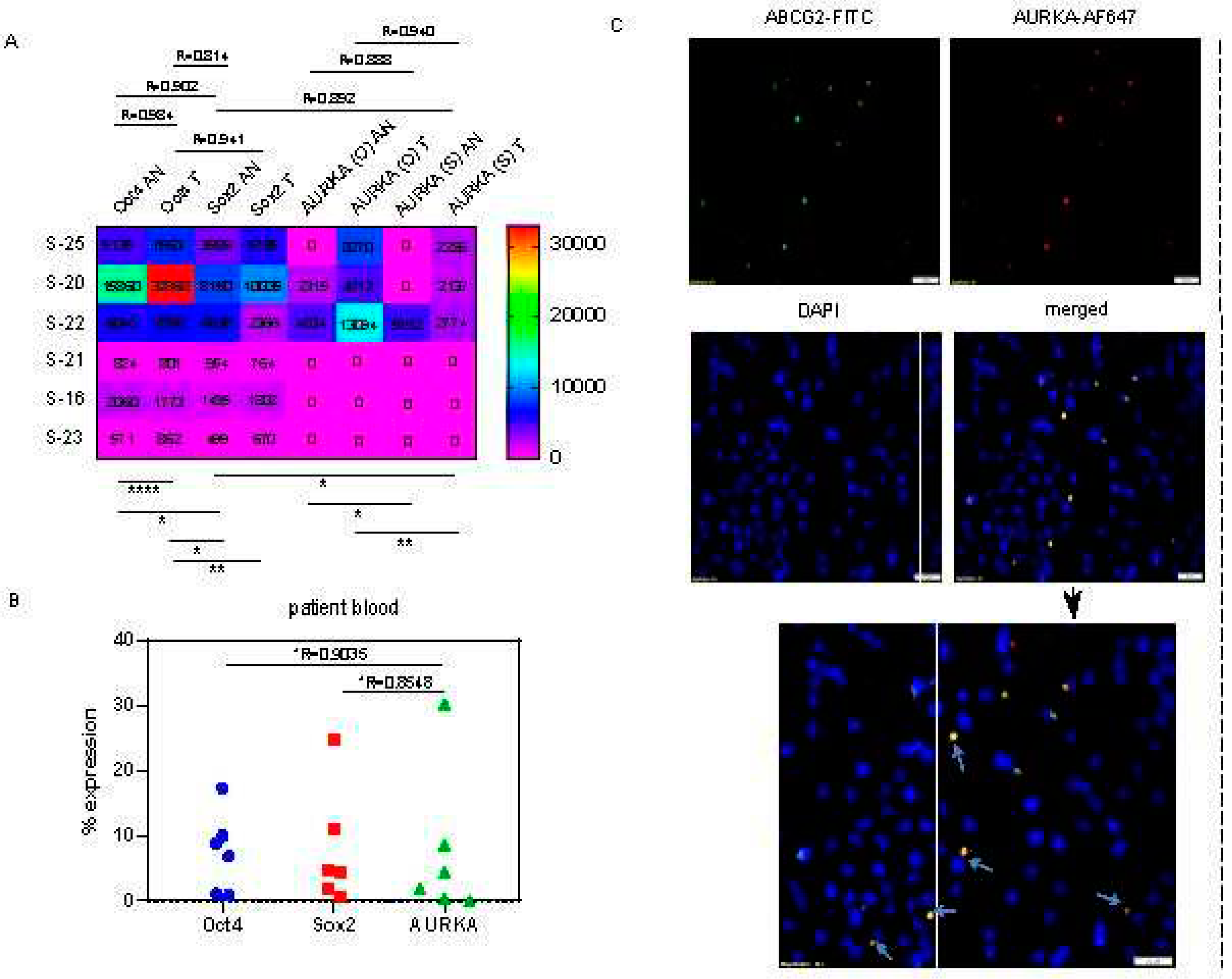

AURKA colocalizes with drug-resistant marker ABCG2 and phospho-NUMB in asymmetrically dividing breast cancer cells:

Oct4/Sox2 is associated with proliferation-independent AURKA functions during epithelial to mesenchymal transition:

Vimentin in addition to AURKA, has to be included as a marker for tracking or targeting drug-resistant Oct4/Sox2 positive BCSCs:

Discussion:

Materials and Methods:

Gene expression analysis:

Survival analysis:

Promoter analysis in silico:

Correlation analyses:

Cell lines and transfections:

Flow cytometric analyses:

Cell Cycle:

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation:

Indirect Immunofluorescence:

Co-immunoprecipitation:

Statistics

Author Contributions

Study approval

Acknowledgement

Declaration

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017, 67, 7–30.

- Colleoni M, Sun Z, Price KN, Karlsson P, Forbes JF, Thürlimann B, et al. Annual Hazard Rates of Recurrence for Breast Cancer During 24 Years of Follow-Up: Results From the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2016, 34, 927–35. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4933127/ (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Roser M, Ortiz-Ospina E, Ritchie H. Life Expectancy Our World in Data [Internet]. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994, 367, 645–8.

- Zhao W, Li Y, Zhang X. Stemness-Related Markers in Cancer. Cancer Transl Med [Internet]. 2017, 3, 87–95. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5737740/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Walcher L, Kistenmacher A-K, Suo H, Kitte R, Dluczek S, Strauß A, et al. Cancer Stem Cells—Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Frontiers in Immunology [Internet]. 2020, 11, 1280. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01280 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Qin S, Jiang J, Lu Y, Nice EC, Huang C, Zhang J, et al. Emerging role of tumor cell plasticity in modifying therapeutic response. Sig Transduct Target Ther [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2020, 5, 1–36. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-020-00313-5 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Zhou H-M, Zhang J-G, Zhang X, Li Q. Targeting cancer stem cells for reversing therapy resistance: mechanism, signaling, and prospective agents. Sig Transduct Target Ther [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2021, 6, 1–17. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-020-00430-1 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Arnold CR, Mangesius J, Skvortsova I-I, Ganswindt U. The Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Radiation Resistance. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2020, 10, 164. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7044409/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Zheng Q, Zhang M, Zhou F, Zhang L, Meng X. The Breast Cancer Stem Cells Traits and Drug Resistance. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2021, 11, 599965. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7876385/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Mavingire N, Campbell P, Wooten J, Aja J, Davis MB, Loaiza-Perez A, et al. Cancer stem cells: Culprits in endocrine resistance and racial disparities in breast cancer outcomes. Cancer Lett. 2021, 500, 64–74.

- Staff S, Isola J, Jumppanen M, Tanner M. Aurora-A gene is frequently amplified in basal-like breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010, 23, 307–12.

- den Hollander J, Rimpi S, Doherty JR, Rudelius M, Buck A, Hoellein A, et al. Aurora kinases A and B are up-regulated by Myc and are essential for maintenance of the malignant state. Blood [Internet]. 2010, 116, 1498–505. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Ueda A, Kanamori H, Ideguchi H, Yang J, Kitajima S, et al. Cell-cycle-dependent regulation of human aurora A transcription is mediated by periodic repression of E4TF1. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 10719–26.

- Wu C-C, Yang T-Y, Yu C-TR, Phan L, Ivan C, Sood AK, et al. p53 negatively regulates Aurora A via both transcriptional and posttranslational regulation. Cell Cycle [Internet]. 2012, 11, 3433–42. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3466554/ (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Du R, Huang C, Liu K, Li X, Dong Z. Targeting AURKA in Cancer: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for Cancer therapy. Molecular Cancer [Internet]. 2021, 20, 15. [CrossRef]

- Nikonova AS, Astsaturov I, Serebriiskii IG, Dunbrack RL, Golemis EA. Aurora A kinase (AURKA) in normal and pathological cell division. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013, 70, 661–87.

- Bertolin G, Tramier M. Insights into the non-mitotic functions of Aurora kinase A: more than just cell division. Cell Mol Life Sci [Internet]. 2020, 77, 1031–47. [CrossRef]

- Yang N, Wang C, Wang Z, Zona S, Lin S-X, Wang X, et al. FOXM1 recruits nuclear Aurora kinase A to participate in a positive feedback loop essential for the self-renewal of breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene [Internet]. 2017, 36, 3428–40. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/onc2016490 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Tanaka T, Kimura M, Matsunaga K, Fukada D, Mori H, Okano Y. Centrosomal kinase AIK1 is overexpressed in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 2041–4.

- Ali HR, Dawson S-J, Blows FM, Provenzano E, Pharoah PD, Caldas C. Aurora kinase A outperforms Ki67 as a prognostic marker in ER-positive breast cancer. Br J Cancer [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2012, 106, 1798–806. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/bjc2012167 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- O’Connor OA, Özcan M, Jacobsen ED, Roncero JM, Trotman J, Demeter J, et al. Randomized Phase III Study of Alisertib or Investigator’s Choice (Selected Single Agent) in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019, 37, 613–23.

- Hu J, Qin K, Zhang Y, Gong J, Li N, Lv D, et al. Downregulation of transcription factor Oct4 induces an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via enhancement of Ca2+ influx in breast cancer cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications [Internet]. 2011, 411, 786–91. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006291X11012447 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Wu F, Zhang J, Wang P, Ye X, Jung K, Bone KM, et al. Identification of two novel phenotypically distinct breast cancer cell subsets based on Sox2 transcription activity. Cell Signal. 2012, 24, 1989–98.

- Siddique HR, Feldman DE, Chen C-L, Punj V, Tokumitsu H, Machida K. NUMB phosphorylation destabilizes p53 and promotes self-renewal of tumor-initiating cells by a NANOG-dependent mechanism in liver cancer. Hepatology. 2015, 62, 1466–79.

- Vagiannis D, Zhang Y, Budagaga Y, Novotna E, Skarka A, Kammerer S, et al. Alisertib shows negligible potential for perpetrating pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions on ABCB1, ABCG2 and cytochromes P450, but acts as dual-activity resistance modulator through the inhibition of ABCC1 transporter. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2022, 434, 115823.

- Arnold CR, Mangesius J, Skvortsova I-I, Ganswindt U. The Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Radiation Resistance. Front Oncol [Internet]. 2020, 10, 164. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7044409/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Brown JA, Schober M. Cellular quiescence: How TGFβ protects cancer cells from chemotherapy. Mol Cell Oncol [Internet]. 2018, 5, e1413495. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5821413/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Chen W, Dong J, Haiech J, Kilhoffer M-C, Zeniou M. Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence and Plasticity as Major Challenges in Cancer Therapy. Stem Cells Int [Internet]. 2016, 2016, 1740936. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4932171/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Walcher L, Kistenmacher A-K, Suo H, Kitte R, Dluczek S, Strauß A, et al. Cancer Stem Cells—Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2020, 11, 1280. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7426526/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Guarino Almeida E, Renaudin X, Venkitaraman AR. A kinase-independent function for AURORA-A in replisome assembly during DNA replication initiation. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. 2020, 48, 7844–55. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7430631/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Strebinger D, Deluz C, Friman ET, Govindan S, Alber AB, Suter DM. Endogenous fluctuations of OCT4 and SOX2 bias pluripotent cell fate decisions. Mol Syst Biol [Internet]. 2019, 15, e9002. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6759502/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Gómez-López S, Lerner RG, Petritsch C. Asymmetric cell division of stem and progenitor cells during homeostasis and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci [Internet]. 2014, 71, 575–97. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3901929/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Morrow CS, Porter TJ, Xu N, Arndt ZP, Ako-Asare K, Heo HJ, et al. Vimentin Coordinates Protein Turnover at the Aggresome during Neural Stem Cell Quiescence Exit. Cell Stem Cell [Internet]. 2020, 26, 558–568e9. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1934590920300187 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Mo W, Zhang J-T. Human ABCG2: structure, function, and its role in multidrug resistance. Int J Biochem Mol Biol [Internet]. 2011, 3, 1–27. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3325772/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Strouhalova K, Přechová M, Gandalovičová A, Brábek J, Gregor M, Rosel D. Vimentin Intermediate Filaments as Potential Target for Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel) [Internet]. 2020, 12, 184. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7017239/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Bargagna-Mohan P, Hamza A, Kim Y, Khuan Abby Ho Y, Mor-Vaknin N, Wendschlag N, et al. The tumor inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent withaferin A targets the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Chem Biol. 2007, 14, 623–34.

- Bai F, Yu Z, Gao X, Gong J, Fan L, Liu F. Simvastatin induces breast cancer cell death through oxidative stress up-regulating miR-140-5p. Aging (Albany NY) [Internet]. 2019, 11, 3198–219. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6555469/ (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Bosch-Barrera J, Corominas-Faja B, Cuyàs E, Martin-Castillo B, Brunet J, Menendez JA. Silibinin Administration Improves Hepatic Failure Due to Extensive Liver Infiltration in a Breast Cancer Patient. Anticancer Research [Internet]. International Institute of Anticancer Research; 2014, 34, 4323–7. Available online: https://ar.iiarjournals.org/content/34/8/4323 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Guo K, Feng Y, Zheng X, Sun L, Wasan HS, Ruan S, et al. Resveratrol and Its Analogs: Potent Agents to Reverse Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Tumors Frontiers in Oncology [Internet]. 2021, 11. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2021.644134 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Dorsch M, Kowalczyk M, Planque M, Heilmann G, Urban S, Dujardin P, et al. Statins affect cancer cell plasticity with distinct consequences for tumor progression and metastasis. Cell Reports [Internet]. 2021, 37, 110056. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211124721015424 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Bollong MJ, Pietilä M, Pearson AD, Sarkar TR, Ahmad I, Soundararajan R, et al. A vimentin binding small molecule leads to mitotic disruption in mesenchymal cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [Internet]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 2017, 114, E9903–12. Available online: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1716009114 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Smith CA, Lau KM, Rahmani Z, Dho SE, Brothers G, She YM, et al. aPKC-mediated phosphorylation regulates asymmetric membrane localization of the cell fate determinant Numb. EMBO J [Internet]. 2007, 26, 468–80. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1783459/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Dho SE, Trejo J, Siderovski DP, McGlade CJ. Dynamic regulation of mammalian numb by G protein-coupled receptors and protein kinase C activation: Structural determinants of numb association with the cortical membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2006, 17, 4142–55.

- Atkinson RL, Yang WT, Rosen DG, Landis MD, Wong H, Lewis MT, et al. Cancer stem cell markers are enriched in normal tissue adjacent to triple negative breast cancer and inversely correlated with DNA repair deficiency. Breast Cancer Research [Internet]. 2013, 15, R77. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Guo M, Zhao F, Liu Q, Wang X. Colonic stem cells from normal tissues adjacent to tumor drive inflammation and fibrosis in colorectal cancer. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2023, 21, 186. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Xu J, Xu Z, Wang Y, Wu S, Wu L, et al. Expression of vimentin and Oct-4 in gallbladder adenocarcinoma and their relationship with vasculogenic mimicry and their clinical significance. Int J Clin Exp Pathol [Internet]. 2018, 11, 3618–27. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6962874/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Wang X, Dai J. Concise Review: Isoforms of OCT4 Contribute to the Confusing Diversity in Stem Cell Biology. Stem Cells [Internet]. 2010, 28, 885–93. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2962909/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Nishikawa G, Kawada K, Nakagawa J, Toda K, Ogawa R, Inamoto S, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote colorectal cancer progression via CCR5. Cell Death Dis [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2019, 10, 1–13. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41419-019-1508-2 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Kim J, Kim NK, Park SR, Choi BH. GM-CSF Enhances Mobilization of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells via a CXCR4-Medicated Mechanism. Tissue Eng Regen Med [Internet]. 2018, 16, 59–68. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6361095/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Kumar A, Taghi Khani A, Sanchez Ortiz A, Swaminathan S. GM-CSF: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2022, 13, 901277. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9294178/ (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Rolf HJ, Niebert S, Niebert M, Gaus L, Schliephake H, Wiese KG. Intercellular Transport of Oct4 in Mammalian Cells: A Basic Principle to Expand a Stem Cell Niche? PLoS One [Internet]. 2012, 7, e32287. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3281129/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Győrffy, B. Survival analysis across the entire transcriptome identifies biomarkers with the highest prognostic power in breast cancer Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal [Internet]. Elsevier; 2021, 19, 4101–9. Available online: https://www.csbj.org/article/S2001-0370(21)00304-4/fulltext (accessed on 19 September 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He W, Kularatne SA, Kalli KR, Prendergast FG, Amato RJ, Klee GG, et al. Quantitation of circulating tumor cells in blood samples from ovarian and prostate cancer patients using tumor-specific fluorescent ligands. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2008, 123, 1968–73. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2778289/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Carbonari M, Mancaniello D, Tedesco T, Fiorilli M. Flow acetone-staining technique: A highly efficient procedure for the simultaneous analysis of DNA content, cell morphology, and immunophenotype by flow cytometry Cytometry Part A [Internet]. 2008, 73A, 168–74. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cyto.a.20521 (accessed on 24 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).