Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

06 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

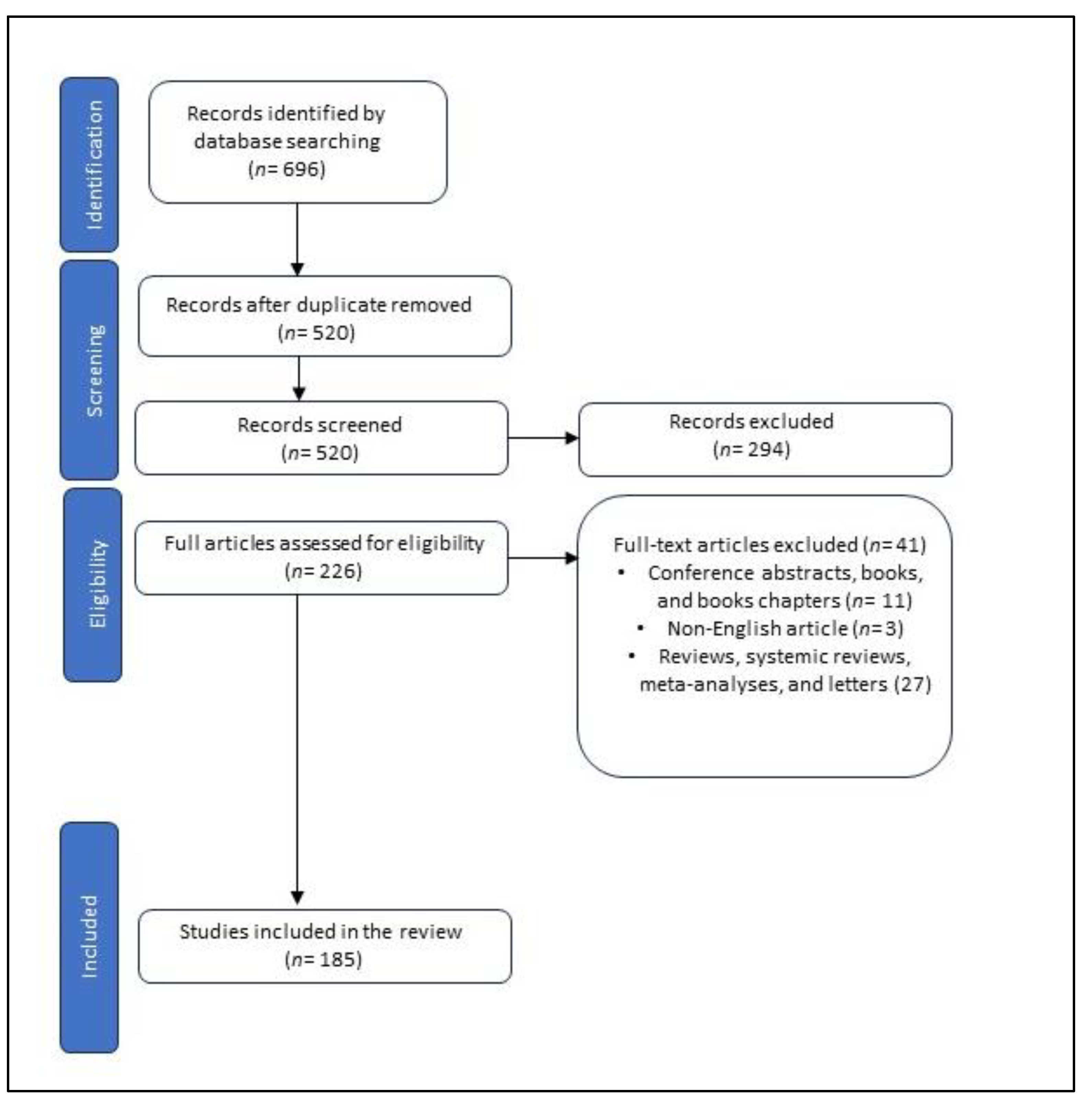

2. Methodology

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data extraction

3. Nicotine

3.1. Chemical and pharmacological properties of nicotine

3.2. The cognitive effects of nicotine

3.3. Short-term cognitive effects of nicotine

3.4. Effects of nicotine on neuroinflammation

3.5. Effects of nicotine on apoptosis

3.6. Effects of nicotine on neurotrophic factors

3.7. Effects of nicotine on amyloid beta peptide (Aβ)

3.8. Effects of nicotine on oxidative stress

4. 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine

4.1. Nicotine catabolism in bacteria as a source of 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine

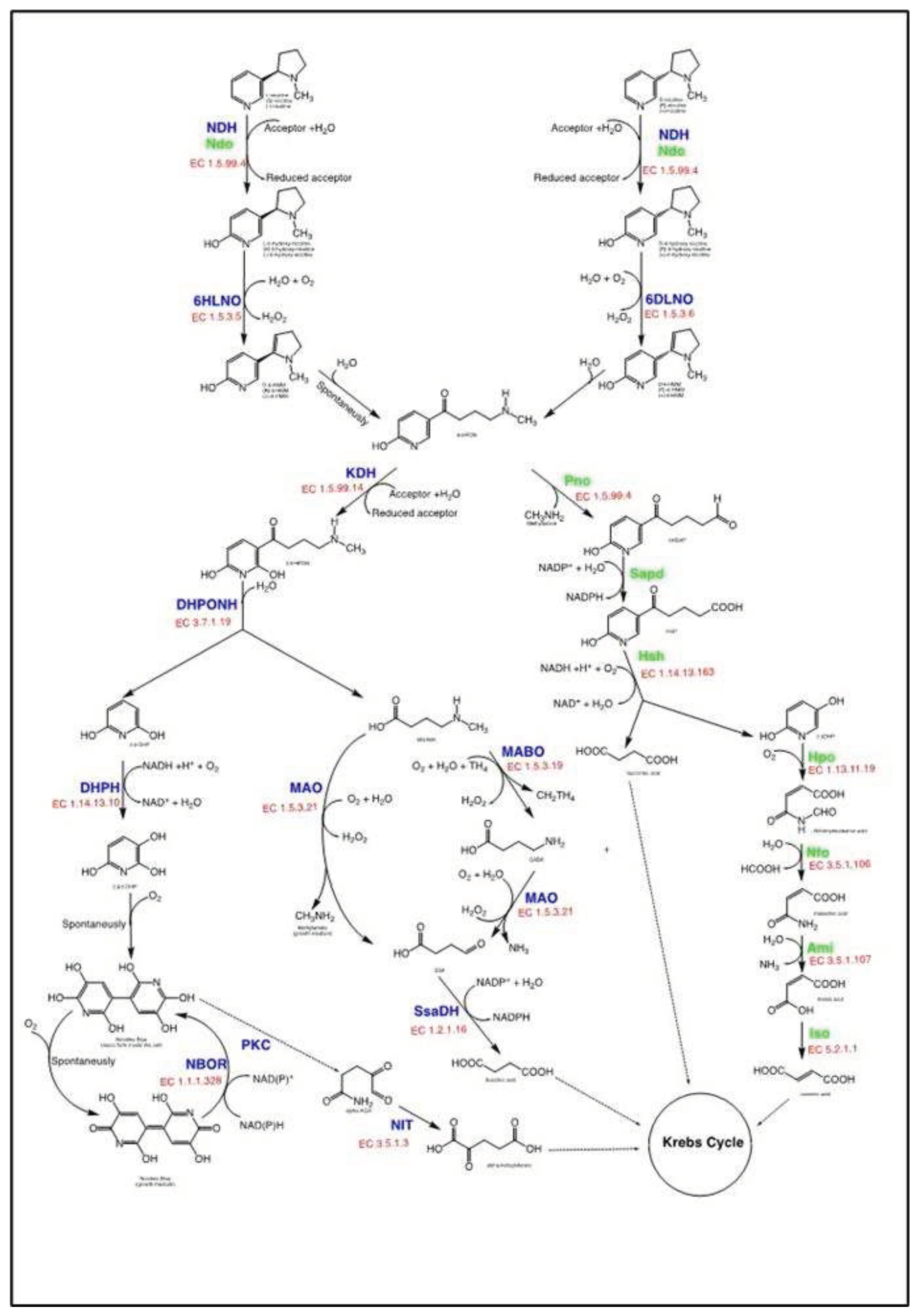

4.1.1. The pyridine pathway for nicotine degradation

4.1.2. The VPP pathway for nicotine degradation

4.2. Applications of NDB for 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine production from nicotine-containing waste

4.3. The behavioral effects of 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine

4.4. Effects of 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine on acetylcholinesterase activity

4.5. Effects of 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine on oxidative stress

4.6. The proposed mechanism of action for 6-hydroxy-L-nicotine

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Picciotto, M.R.; Kenny, P.J. Mechanisms of Nicotine Addiction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, P.; Kellar, K.; Aisen, P.; White, H.; Wesnes, K.; Coderre, E.; Pfaff, A.; Wilkins, H.; Howard, D.; Levin, E.D. Nicotine Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 6-Month Double-Blind Pilot Clinical Trial. Neurology 2012, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Liao, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, F. Nicotine and Menthol Independently Exert Neuroprotective Effects against Cisplatin- or Amyloid- Toxicity by Upregulating Bcl-Xl via JNK Activation in SH-SY5Y Cells. Biocell 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.Q.; Liu, X.X.; Zhang, Y.L.; Gao, F.G. Nicotine Exerts Neuroprotective Effects against β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells through the Erk1/2-P38-JNK-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Med 2014, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; He, X.Y.; Ding, X.; Prabhu, S.; Hong, J.Y. Metabolism of Nicotine and Cotinine by Human Cytochrome P450 2A13. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2005, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Vatandoust, S.M.; Mahmoudi, J.; Rahigh Aghsan, S.; Majdi, A. Cotinine Ameliorates Memory and Learning Impairment in Senescent Mice. Brain Res Bull 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, V.; Zeitlin, R.; Burgess, S.; Patel, S.; Barman, A.; Thakur, G.; Mamcarz, M.; Wang, L.; Sattelle, D.B.; Kirschner, D.A.; et al. Cotinine Reduces Amyloid-β Aggregation and Improves Memory in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2011, 24, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Adam, B.L.; Terry, A. V. Evaluation of Nicotine and Cotinine Analogs as Potential Neuroprotective Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benowitz, N.L.; Hukkanen, J.; Jacob, P. Nicotine Chemistry, Metabolism, Kinetics and Biomarkers. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2009, 192, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, R.; Natarajan, S. Current Status on Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Microbial Degradation of Nicotine. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, C.N.; Gregersen, P.K.; Malhotra, A.K. Metabolism and Biochemical Effects of Nicotine for Primary Care Providers. Medical Clinics of North America 2004, 88, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockman, P.R.; McAfee, G.; Geldenhuys, W.J.; Van Der Schyf, C.J.; Abbruscato, T.J.; Allen, D.D. Brain Uptake Kinetics of Nicotine and Cotinine after Chronic Nicotine Exposure. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2005, 314, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, S.G.; Balfour, D.J.; Benowitz, N.L.; Boyd, R.T.; Buccafusco, J.J.; Caggiula, A.R.; Craig, C.R.; Collins, A.C.; Damaj, M.I.; Donny, E.C.; et al. Guidelines on Nicotine Dose Selection for in Vivo Research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007, 190, 269–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G.; Sofuoglu, M. Cognitive Effects of Nicotine: Recent Progress. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Wang, M.; Song, M.; Sun, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, J.; Jin, X. Acute Nicotine Treatment Alleviates LPS-Induced Impairment of Fear Memory Reconsolidation through AMPK Activation and CRTC1 Upregulation in Hippocampus. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 23, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grus, A.; Hromatko, I. Acute Administration of Nicotine Does Not Enhance Cognitive Functions. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 2019, 70, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluzzi, J.D.; Wang, R.; Leslie, F.M. Acetaldehyde Enhances Acquisition of Nicotine Self-Administration in Adolescent Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltavski, D. V.; Petros, T. V.; Holm, J.E. Lower but Not Higher Doses of Transdermal Nicotine Facilitate Cognitive Performance in Smokers on Gender Non-Preferred Tasks. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2012, 102, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, P.A.; Potter, A.; Singh, A. Effects of Nicotinic Stimulation on Cognitive Performance. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2004, 4, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundey, J.; Amu, R.; Ambrus, G.G.; Batsikadze, G.; Paulus, W.; Nitsche, M.A. Double Dissociation of Working Memory and Attentional Processes in Smokers and Non-Smokers with and without Nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015, 232, 2491–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, A.S.; Newhouse, P.A. Acute Nicotine Improves Cognitive Deficits in Young Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2008, 88, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, M.A.; Banks, W.A. Age-Associated Changes in the Immune System and Blood–Brain Barrier Functions. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shytle, R.D.; Mori, T.; Townsend, K.; Vendrame, M.; Sun, N.; Zeng, J.; Ehrhart, J.; Silver, A.A.; Sanberg, P.R.; Tan, J. Cholinergic Modulation of Microglial Activation by A7 Nicotinic Receptors. J Neurochem 2004, 89, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenaro, E.; Pietronigro, E.; Bianca, V. Della; Piacentino, G.; Marongiu, L.; Budui, S.; Turano, E.; Rossi, B.; Angiari, S.; Dusi, S.; et al. Neutrophils Promote Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology and Cognitive Decline via LFA-1 Integrin. Nat Med 2015, 21, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, A.; Kamari, F.; Vafaee, M.S.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S. Revisiting Nicotine’s Role in the Ageing Brain and Cognitive Impairment. Rev Neurosci 2017, 28, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Simard, A.R.; Turner, G.H.; Wu, J.; Whiteaker, P.; Lukas, R.J.; Shi, F.D. Attenuation of CNS Inflammatory Responses by Nicotine Involves A7 and Non-A7 Nicotinic Receptors. Exp Neurol 2011, 227, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Zheng, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. Acute Nicotine Treatment Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction by Increasing BDNF Expression and Inhibiting Neuroinflammation in the Rat Hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 2015, 604, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Majdi, A.; Mahmoudi, J.; Golzari, S.E.J.; Talebi, M. Astrocytic and Microglial Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: An Overlooked Issue in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neural Transm 2016, 123, 1359–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lau, Y.-L. Nicotine, an Anti-Inflammation Molecule. Inflamm Cell Signal 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, M.; Ochani, M.; Amelia, C.A.; Tanovic, M.; Susarla, S.; Li, J.H.; Wang, H.; Yang, N.; Ulloa, L.; et al. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor A7 Subunit Is an Essential Regulator of Inflammation. Nature 2003, 421, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, R.; Ajmone-Cat, M.A.; Carnevale, D.; Minghetti, L. Activation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor by Nicotine Selectively Up-Regulates Cyclooxygenase-2 and Prostaglandin E2 in Rat Microglial Cultures. J Neuroinflammation 2005, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razani-Boroujerdi, S.; Boyd, R.T.; Dávila-García, M.I.; Nandi, J.S.; Mishra, N.C.; Singh, S.P.; Pena-Philippides, J.C.; Langley, R.; Sopori, M.L. T Cells Express A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunits That Require a Functional TCR and Leukocyte-Specific Protein Tyrosine Kinase for Nicotine-Induced Ca2+ Response. The Journal of Immunology 2007, 179, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizri, E.; Irony-Tur-Sinai, M.; Lory, O.; Orr-Urtreger, A.; Lavi, E.; Brenner, T. Activation of the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory System by Nicotine Attenuates Neuroinflammation via Suppression of Th1 and Th17 Responses. J Immunol 2009, 183, 6681–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, E.; Agrawal, R.; Nath, C.; Shukla, R. Cholinergic Protection via A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors and PI3K-Akt Pathway in LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation. Neurochem Int 2010, 56, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, T. Apoptosis and Its Functional Significance in Molluscs. Apoptosis 2010, 15, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdi, A.; Mahmoudi, J.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Golzari, S.E.J.; Sabermarouf, B.; Reyhani-Rad, S. Permissive Role of Cytosolic PH Acidification in Neurodegeneration: A Closer Look at Its Causes and Consequences. J Neurosci Res 2016, 94, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tizabi, Y.; Manaye, K.F.; Taylor, R.E. Nicotine Blocks Ethanol-Induced Apoptosis in Primary Cultures of Rat Cerebral Cortical and Cerebellar Granule Cells. Neurotox Res 2005, 7, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Mechawar, N.; Krantic, S.; Quirion, R. A7 Nicotinic Receptor Activation Reduces β-Amyloid-Induced Apoptosis by Inhibiting Caspase-Independent Death through Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Signaling. J Neurochem 2011, 119, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, B. Nicotine Attenuates Beta-Amyloid Peptide-Induced Neurotoxicity, Free Radical and Calcium Accumulation in Hippocampal Neuronal Cultures. Br J Pharmacol. 2004, 141, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejmadi, M. V.; Dajas-Bailador, F.; Barns, S.M.; Jones, B.; Wonnacott, S. Neuroprotection by Nicotine against Hypoxia-Induced Apoptosis in Cortical Cultures Involves Activation of Multiple Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subtypes. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 2003, 24, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritcu, L.; Ciobica, A.; Gorgan, L. Nicotine-Induced Memory Impairment by Increasing Brain Oxidative Stress. Cent Eur J Biol 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.H.; Shin, M.C.; Jung, S.B.; Lee, T.H.; Bahn, G.H.; Kwon, Y.K.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, C.J. Alcohol and Nicotine Reduce Cell Proliferation and Enhance Apoptosis in Dentate Gyrus. Neuroreport 2002, 13, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, R.; Mattson, M.P.; Hennig, B.; Toborek, M. Nicotine Protects against Arachidonic-Acid-Induced Caspase Activation, Cytochrome c Release and Apoptosis of Cultured Spinal Cord Neurons. J Neurochem 2001, 76, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, M.B.; Bencherif, M. Convergence of Alpha 7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor-Activated Pathways for Anti-Apoptosis and Anti-Inflammation: Central Role for JAK2 Activation of STAT3 and NF-ΚB. Brain Res 2009, 1256, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo Cardoso, T.; Mondin, T.C.; Wiener, C.D.; Marques, M.B.; Fucolo, B.D.Á.; Pinheiro, R.T.; De Souza, L.D.M.; Da Silva, R.A.; Jansen, K.; Oses, J.P. Neurotrophic Factors, Clinical Features and Gender Differences in Depression. Neurochem Res 2014, 39, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erraji-Benchekroun, L.; Underwood, M.D.; Arango, V.; Galfalvy, H.; Pavlidis, P.; Smyrniotopoulos, P.; Mann, J.J.; Sibille, E. Molecular Aging in Human Prefrontal Cortex Is Selective and Continuous throughout Adult Life. Biol Psychiatry 2005, 57, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmemar, E.; Majdi, A.; Haramshahi, M.; Talebi, M.; Karimi, P.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S. Intranasal Cerebrolysin Attenuates Learning and Memory Impairments in D-Galactose-Induced Senescence in Mice. Exp Gerontol 2017, 87, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrea, S.; Winterer, C. Neuroprotective and Neurotoxic Effects of Nicotine. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009, 42, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongtrakool, C.; Grooms, K.; Bijli, K.M.; Crothers, K.; Fitzpatrick, A.M.; Hart, C.M. Nicotine Stimulates Nerve Growth Factor in Lung Fibroblasts through an NFκB-Dependent Mechanism. PLoS One 2014, 9, e109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, R.; King-Pospisil, K.; Son, K.W.; Hennig, B.; Toborek, M. Nicotine Upregulates Nerve Growth Factor Expression and Prevents Apoptosis of Cultured Spinal Cord Neurons. Neurosci Res 2003, 47, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, R.; Toledano, A.; Álvarez, M.I.; Turégano, L.; Colman, O.; Rosés, P.; Gómez de Segura, I.; De Miguel, E. Chronic Nicotine Administration Increases NGF-like Immunoreactivity in Frontoparietal Cerebral Cortex. J Neurosci Res 2003, 73, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, R.; Garcia, A.A.; Braschi, C.; Capsoni, S.; Maffei, L.; Berardi, N.; Cattaneo, A. Intranasal Administration of Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) Rescues Recognition Memory Deficits in AD11 Anti-NGF Transgenic Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 3811–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czubak, A.; Nowakowska, E.; Kus, K.; Burda, K.; Metelska, J.; Baer-Dubowska, W.; Cichocki, M. Influences of Chronic Venlafaxine, Olanzapine and Nicotine on the Hippocampal and Cortical Concentrations of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). Pharmacol Rep 2009, 61, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.; Wetmore, C.; Stromberg, I.; Leonard, S.; Olson, L. α-Bungarotoxin Binding to Hippocampal Interneurons: Immunocytochemical Characterization and Effects on Growth Factor Expression. Journal of Neuroscience 1993, 13, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Mizuno, M.; Nabeshima, T. Role for Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Learning and Memory. Life Sci 2002, 70, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, K.M.; Kennedy, K.M.; Devous, M.D.; Rieck, J.R.; Hebrank, A.C.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Mathews, D.; Park, D.C. β-Amyloid Burden in Healthy Aging: Regional Distribution and Cognitive Consequences. Neurology 2012, 78, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahs, K.R.; Ashe, K.H. β-Amyloid Oligomers in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2013, 5, 51139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Kumar, V.B.; Farr, S.A.; Nakaoke, R.; Robinson, S.M.; Morley, J.E. Impairments in Brain-to-Blood Transport of Amyloid-β and Reabsorption of Cerebrospinal Fluid in an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Are Reversed by Antisense Directed against Amyloid-β Protein Precursor. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2011, 23, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.; Boche, D.; Wilkinson, D.; Yadegarfar, G.; Hopkins, V.; Bayer, A.; Jones, R.W.; Bullock, R.; Love, S.; Neal, J.W.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Aβ42 Immunisation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Follow-up of a Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase I Trial. The Lancet 2008, 372, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström-Lindahl, E.; Court, J.; Keverne, J.; Svedberg, M.; Lee, M.; Marutle, A.; Thomas, A.; Perry, E.; Bednar, I.; Nordberg, A. Nicotine Reduces Aβ in the Brain and Cerebral Vessels of APPsw Mice. European Journal of Neuroscience 2004, 19, 2703–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsuki, T.; Shoaib, M.; Holloway, H.W.; Ingram, D.K.; Wallace, W.C.; Haroutunian, V.; Sambamurti, K.; Lahiri, D.K.; Greig, N.H. Nicotine Lowers the Secretion of the Alzheimer’s Amyloid β-Protein Precursor That Contains Amyloid β-Peptide in Rat. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2002, 4, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordberg, A.; Hellström-Lindahl, E.; Lee, M.; Johnson, M.; Mousavi, M.; Hall, R.; Perry, E.; Bednar, I.; Court, J. Chronic Nicotine Treatment Reduces β-Amyloidosis in the Brain of a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease (APPsw). J Neurochem 2002, 81, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Yamada, M.; Naiki, H. Nicotine Breaks down Preformed Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Fibrils in Vitro. Biol Psychiatry 2002, 52, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineley, K.T.; Westerman, M.; Bui, D.; Bell, K.; Ashe, K.H.; Sweatt, J.D. β-Amyloid Activates the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade via Hippocampal A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: In Vitro and in Vivo Mechanisms Related to Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21, 4125–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Talebi, M.; Farhoudi, M.; Golzari, S.E.J.; Sabermarouf, B.; Mahmoudi, J. Beta-Amyloid Exhibits Antagonistic Effects on Alpha 7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Orchestrated Manner. Journal of Medical Hypotheses and Ideas 2014, 8, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inestrosa, N.C.; Godoy, J.A.; Vargas, J.Y.; Arrazola, M.S.; Rios, J.A.; Carvajal, F.J.; Serrano, F.G.; Farias, G.G. Nicotine Prevents Synaptic Impairment Induced by Amyloid-β Oligomers through A7-Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Activation. Neuromolecular Med 2013, 15, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdi, A.; Kamari, F.; Vafaee, M.S.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S. Revisiting Nicotine’s Role in the Ageing Brain and Cognitive Impairment. Rev Neurosci 2017, 28, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J.; Zucca, F.A.; Duyn, J.H.; Crichton, R.R.; Zecca, L. The Role of Iron in Brain Ageing and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, A.M.; Raz, N. Appraising the Role of Iron in Brain Aging and Cognition: Promises and Limitations of MRI Methods. Neuropsychol Rev 2015, 25, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, M.; Jahromi, S.R.; Sagar, B.K.C.; Patil, R.K.; Shivanandappa, T.; Ramesh, S.R. Brain Aging, Memory Impairment and Oxidative Stress: A Study in Drosophila Melanogaster. Behavioural Brain Research 2014, 259, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GuanZ. Z.; YuW.F.; NordbergA.; Guan, Z.-Z.; Yu, W.-F.; Nordberg, A. Dual Effects of Nicotine on Oxidative Stress and Neuroprotection in PC12 Cells. Neurochem Int. 2003, 43, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachauri, V.; Flora, S.J.S. Effect of Nicotine Pretreatment on Arsenic-Induced Oxidative Stress in Male Wistar Rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 2013, 32, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Otero, R.; Méndez-Alvarez, E.; Hermida-Ameijeiras, A.; López-Real, A.M.; Labandeira-García, J.L. Effects of (-)-Nicotine and (-)-Cotinine on 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Oxidative Stress and Neurotoxicity: Relevance for Parkinson’s Disease. Biochem Pharmacol 2002, 64, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goerig, M.; Ullrich, V.; Schettler, G.; Foltis, C.; Habenicht, A. A New Role for Nicotine: Selective Inhibition of Thromboxane Formation by Direct Interaction with Thromboxane Synthase in Human Promyelocytic Leukaemia Cells Differentiating into Macrophages. Clin Investig 1992, 70, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linert, W.; Bridge, M.H.; Huber, M.; Bjugstad, K.B.; Grossman, S.; Arendash, G.W. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies Investigating Possible Antioxidant Actions of Nicotine: Relevance to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1999, 1454, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Nesil, T.; Cao, J.; Yang, Z.; Chang, S.L.; Li, M.D. Nicotine Mediates Expression of Genes Related to Antioxidant Capacity and Oxidative Stress Response in HIV-1 Transgenic Rat Brain. J Neurovirol 2016, 22, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.L. Crowley-Weber C. Crowley, H. Bernstein, C. Bernstein, H. Garewal, C.M. Payne, K.D. Nicotine Increases Oxidative Stress, Activates NF-KappaB and GRP78, Induces Apoptosis and Sensitizes Cells to Genotoxic/Xenobiotic Stresses by a Multiple Stress Inducer, Deoxycholate: Relevance to Colon Carcinogenesis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2003, 145, 53–66.

- Igloi, G.; Brandsch, R. Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans PAO1 Megaplasmid Sequence,Strain ATCC 49919. GenBank 2002. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sabeh, A.; Honceriu, I.; Kallabi, F.; Boiangiu, R.-S.; Mihasan, M. Complete Genome Sequences of Two Closely Related Paenarthrobacter Nicotinovorans Strains. Microbiol Resour Announc 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, A.; Min, H.; Zhu, W. Studies on Biodegradation of Nicotine by Arthrobacter Sp. Strain HF-2. J Environ Sci Health B 2006, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Tang, H.; Ren, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, P. Genome Sequence of a Nicotine-Degrading Strain of Arthrobacter. J Bacteriol 2012, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, A.; Gao, Y.; Fang, C.; Xu, Y. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Nicotinophilic Bacterium, Arthrobacter Sp. ARF-1 and Its Metabolic Pathway. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2018, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yu, H.; Tai, C.; Huang, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Yao, Y.; Wu, G.; Xu, P. Genome Sequence of a Novel Nicotine-Degrading Strain, Pseudomonas Geniculata N1. J Bacteriol 2012, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, K.; Wang, W.; Nie, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, S.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Physiological and Biochemical Characterization of a Novel Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas Geniculata N1. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Lei, L.; Xia, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, P.; Liu, X. Characterisation of a Novel Aerobic Nicotine-Biodegrading Strain of Pseudomonas Putida. Ann Microbiol 2008, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Lv, P.; Wu, X.; Li, Q.X.; Cao, H.; Hua, R. Characterization of Nicotine Catabolism through a Novel Pyrrolidine Pathway in Pseudomonas Sp. S-1. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.; Lei, L.P.; Wu, Y.P.; Ren, K.; Li, Y.; Zou, C.M. A Novel Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas Fluorescens Strain 1206. Appl Biochem Microbiol 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, A.; Min, H.; Peng, X.; Huang, Z. Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas Sp. Strain HF-1, Capable of Degrading Nicotine. Res Microbiol 2005, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, G.; Mohan, K.N.; Manohar, V.; Sakthivel, N. Biodegradation of Nicotine by a Novel Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium, Pseudomonas Plecoglossicida TND35 and Its New Biotransformation Intermediates. Biodegradation 2014, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wen, Y.; Liu, W. Cloning of a Novel Nicotine Oxidase Gene from Pseudomonas Sp. Strain HZN6 Whose Product Nonenantioselectively Degrades Nicotine to Pseudooxynicotine. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Yin, B.; Peng, X.X.; Wang, J.Y.; Xie, Z.H.; Gao, J.; Tang, X.K. Biodegradation of Nicotine by Newly Isolated Pseudomonas Sp. CS3 and Its Metabolites. J Appl Microbiol 2012, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Gong, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.Q. Isolation of Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas Sp. Nic22, and Its Potential Application in Tobacco Processing. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2008, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.N.; Liu, Z.; Xu, P. Biodegradation of Nicotine by a Newly Isolated Agrobacterium Sp. Strain S33. J Appl Microbiol 2009, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; He, Q.; Jiang, J.; Hong, Q.; He, J. Isolation and Characterization of the Cotinine-Degrading Bacterium Nocardioides Sp. Strain JQ2195. J Hazard Mater 2018, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobzaru, C.; Ganas, P.; Mihasan, M.; Schleberger, P.; Brandsch, R. Homologous Gene Clusters of Nicotine Catabolism, Including a New ω-Amidase for α-Ketoglutaramate, in Species of Three Genera of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Res Microbiol 2011, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.F.; Xia, Z.Z.; Yao, J.C.; Feng, Z.; Li, D.H.; Liu, T.; Cheng, G.J.; He, D.L.; Li, X.H. Functional Analysis of the Ocne Gene Involved in Nicotine-Degradation Pathways in Ochrobactrum Intermedium SCUEC4 and Its Enzymatic Properties. Can J Microbiol 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tang, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, P. Molecular Mechanism of Nicotine Degradation by a Newly Isolated Strain, Ochrobactrum Sp. Strain SJY1. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.J.; Lu, Z.X.; Wu, N.; Huang, L.J.; Lü, F.X.; Bie, X.M. Isolation and Preliminary Characterization of a Novel Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium, Ochrobactrum Intermedium DN2. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2005, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; He, J.; Lu, Z. The Complete Genome Sequence of the Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Shinella Sp. HZN7. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.J.; Ma, Y.; Qiu, G.J.; Wu, F.L.; Chen, S.L. Biodegradation of Nicotine by a Novel Strain Shinella Sp. HZN1 Isolated from Activated Sludge. J Environ Sci Health B 2011, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Yao, Y.; Min, H.; Lu, Z. Nicotine Degradation by Two Novel Bacterial Isolates of Acinetobacter Sp. TW and Sphingomonas Sp. TY and Their Responses in the Presence of Neonicotinoid Insecticides. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2011, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Gong, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, B.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zou, C. Biodegradation of Nicotine and TSNAs by Bacterium Sp. Strain J54. Iran J Biotechnol 2021, 19, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yin, M.; Lei, S.; Zhang, H.; Yin, X.; Niu, Q. Bacillus Sp. YC7 from Intestines of Lasioderma Serricorne Degrades Nicotine Due to Nicotine Dehydrogenase. AMB Express 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhi, X.Y.; Qiu, J.; Shi, L.; Lu, Z. Characterization of a Novel Nicotine Degradation Gene Cluster Ndp in Sphingomonas Melonis TY and Its Evolutionary Analysis. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wen, R.; Qiu, J.; Hong, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D. Biodegradation of Nicotine by a Novel Strain Pusillimonas. Res Microbiol 2015, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.W.; Yang, J.K.; Duan, Y.Q.; Dong, J.Y.; Zhe, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.H.; Zhang, K.Q. Isolation and Characterization of Rhodococcus Sp. Y22 and Its Potential Application to Tobacco Processing. Res Microbiol 2009, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganas, P.; Sachelaru, P.; Mihasan, M.; Igloi, G.L.; Brandsch, R. Two Closely Related Pathways of Nicotine Catabolism in Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans and Nocardioides Sp. Strain JS614. Arch Microbiol 2008, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Zhang, W.; Wei, H.; Xia, Z.; Liu, X. Characterization of a Novel Nicotine-Degrading Ensifer Sp. Strain N7 Isolated from Tobacco Rhizosphere. Ann Microbiol 2009, 59, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, W.; He, F.; Zhang, P.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Structural Insights into 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Amine Oxidase from Pseudomonas Geniculata N1, the Key Enzyme Involved in Nicotine Degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol 2020, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grether-Beck, S.; Igloi, G.L.; Pust, S.; Schilz, E.; Decker, K.; Brandsch, R. Structural Analysis and Molybdenum-dependent Expression of the PAO1-encoded Nicotine Dehydrogenase Genes of Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans. Mol Microbiol 1994, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Qiu, J.; Chen, D.; Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Tong, L.; Jiang, J.; Chen, J. Characterization and Genome Analysis of a Nicotine and Nicotinic Acid-Degrading Strain Pseudomonas Putida JQ581 Isolated from Marine. Mar Drugs 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lei, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, H.L. Genome-Wide Investigation of the Genes Involved in Nicotine Metabolism in Pseudomonas Putida J5 by Tn5 Transposon Mutagenesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Cloning and Characterization the Nicotine Degradation Enzymes 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Amine Oxidase and 6-Hydroxy-3-Succinoylpyridine Hydroxylase in Pseudomonas Geniculata N1. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2019, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, K.; Yu, W.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. Nicotine Dehydrogenase Complexed with 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Oxidase Involved in the Hybrid Nicotine-Degrading Pathway in Agrobacterium Tumefaciens S33. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandsch, R.; Mihasan, M. A Soil Bacterial Catabolic Pathway on the Move: Transfer of Nicotine Catabolic Genes between Arthrobacter Genus Megaplasmids and Invasion by Mobile Elements. J Biosci 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sabeh, A.; Mlesnita, A.M.; Munteanu, I.T.; Honceriu, I.; Kallabi, F.; Boiangiu, R.S.; Mihasan, M. Characterisation of the Paenarthrobacter Nicotinovorans ATCC 49919 Genome and Identification of Several Strains Harbouring a Highly Syntenic Nic-Genes Cluster. BMC Genomics 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igloi, G.L.; Brandsch, R. Sequence of the 165-Kilobase Catabolic Plasmid PAO1 from Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans and Identification of a PAO1-Dependent Nicotine Uptake System. J Bacteriol 2003, 185, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihǎşan, M.; Boiangiu, R.Ş.; Guzun, D.; Babii, C.; Aslebagh, R.; Channaveerappa, D.; Dupree, E.; Darie, C.C.; Mihǎşan, M. Time-Dependent Analysis of Paenarthrobacter Nicotinovorans PAO1 Nicotine-Related Proteome. ACS Omega 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăşan, M.; Babii, C.; Aslebagh, R.; Channaveerappa, D.; Dupree, E.J.; Darie, C.C. Exploration of Nicotine Metabolism in Paenarthrobacter Nicotinovorans PAO1 by Microbial Proteomics. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăşan, M.; Babii, C.; Aslebagh, R.; Channaveerappa, D.; Dupree, E.; Darie, C.C. Proteomics Based Analysis of the Nicotine Catabolism in Paenarthrobacter Nicotinovorans PAO1. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiribau, C.B.; Mihasan, M.; Ganas, P.; Igloi, G.L.; Artenie, V.; Brandsch, R. Final Steps in the Catabolism of Nicotine Deamination versus Demethylation of γ-N-Methylaminobutyrate. FEBS Journal 2006, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihasan, M.; Brandsch, R. PAO1 of Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans and the Spread of Catabolic Traits by Horizontal Gene Transfer in Gram-Positive Soil Bacteria. J Mol Evol 2013, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganas, P.; Brandsch, R. Uptake of L-Nicotine and of 6-Hydroxy-L-Nicotine by Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans and by Escherichia Coli Is Mediated by Facilitated Diffusion and Not by Passive Diffusion or Active Transport. Microbiology (N Y) 2009, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberg, W.; König, K.; Andreesen, J.R. Nicotine Dehydrogenase from Arthrobacter Oxidans: A Molybdenum-Containing Hydroxylase. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1988, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, P.F.; Chadegani, F.; Zhang, S.; Roberts, K.M.; Hinck, C.S. Mechanism of the Flavoprotein l -Hydroxynicotine Oxidase: Kinetic Mechanism, Substrate Specificity, Reaction Product, and Roles of Active-Site Residues. Biochemistry 2016, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, I.; Yildiz, B.S. Mechanistic Study of L-6-Hydroxynicotine Oxidase by DFT and ONIOM Methods. J Mol Model 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koetter, J.W.A.; Schulz, G.E. Crystal Structure of 6-Hydroxy-D-Nicotine Oxidase from Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans. J Mol Biol 2005, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachelaru, P.; Schiltz, E.; Brandsch, R. A Functional MobA Gene for Molybdopterin Cytosine Dinucleotide Cofactor Biosynthesis Is Required for Activity and Holoenzyme Assembly of the Heterotrimeric Nicotine Dehydrogenases of Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, C.; Otto, A.; Igloi, G.; Nick, P.; Brandsch, R.; Schubach, B.; Böttcher, B.; Brandsch, R. Molybdate-Uptake Genes and Molybdopterin-Biosynthesis Genes on a Bacterial Plasmid. Characterization of MoeA as a Filament-Forming Protein with Adenosinetriphosphatase Activity. Eur J Biochem 1997, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleberger, C.; Sachelaru, P.; Brandsch, R.; Schulz, G.E. Structure and Action of a C‒C Bond Cleaving α/β-Hydrolase Involved in Nicotine Degration. J Mol Biol 2007, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiribau, C.B.; Mihasan, M.; Ganas, P.; Igloi, G.; Artenie, V.; Brandsch, R. Final Steps in the Catabolism of Nicotine - Deamination versus Demethylation of Gamma-N-Methylaminobutyrate. Febs Journal 2006, 273, 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganas, P.; Mihasan, M.; Igloi, G.L.; Brandsch, R. A Two-Component Small Multidrug Resistance Pump Functions as a Metabolic Valve during Nicotine Catabolism by Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans. Microbiology (N Y) 2007, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiber, N.; Schulz, G.E. Structure of 2,6-Dihydroxypyridine 3-Hydroxylase from a Nicotine-Degrading Pathway. J Mol Biol 2008, 379, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiribau, C.B.; Sandu, C.; Igloi, G.L.; Brandsch, R. Characterization of PmfR, the Transcriptional Activator of the PAO1-Borne PurU-MabO-FolD Operon of Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans. J Bacteriol 2005, 187, 3062–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihasan, M.; Chiribau, C.-B.; Friedrich, T.; Artenie, V.; Brandsch, R. An NAD(P)H-Nicotine Blue Oxidoreductase Is Part of the Nicotine Regulon and May Protect Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans from Oxidative Stress during Nicotine Catabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 2479–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandu, C.; Chiribau, C.B.; Brandsch, R. Characterization of HdnoR, the Transcriptional Repressor of the 6-Hydroxy-D-Nicotine Oxidase Gene of Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans PAO1, and Its DNA-Binding Activity in Response to L- and D-Nicotine Derivatives. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 51307–51315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhi, X.Y.; Qiu, J.; Shi, L.; Lu, Z. Characterization of a Novel Nicotine Degradation Gene Cluster Ndp in Sphingomonas Melonis TY and Its Evolutionary Analysis. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Tang, H.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, P. Molecular Mechanism of Nicotine Degradation by a Newly Isolated Strain, Ochrobactrum Sp. Strain SJY1. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; He, J.; Lu, Z. The Complete Genome Sequence of the Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Shinella Sp. HZN7. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wei, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wen, R.; Hong, J.; Liu, W. Isolation, Transposon Mutagenesis, and Characterization of the Novel Nicotine-Degrading Strain Shinella Sp. HZN7. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 2625–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xie, K.; Yu, W.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. Nicotine Dehydrogenase Complexed with 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Oxidase Involved in the Hybrid Nicotine-Degrading Pathway in Agrobacterium Tumefaciens S33. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016, 82, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Cloning and Characterization the Nicotine Degradation Enzymes 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Amine Oxidase and 6-Hydroxy-3-Succinoylpyridine Hydroxylase in Pseudomonas Geniculata N1. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation 2019, 142, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yu, W.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Agrobacterium Tumefaciens S33 Reveal the Molecular Mechanism of a Novel Hybrid Nicotine-Degrading Pathway. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yi, J.; Shang, J.; Yu, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine Dehydrogenase Delivers Electrons to Electron Transfer Flavoprotein during Nicotine Degradation by Agrobacterium Tumefaciens S33. Appl Environ Microbiol 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Huang, H.; Xie, K.; Xu, P. Identification of Nicotine Biotransformation Intermediates by Agrobacterium Tumefaciens Strain S33 Suggests a Novel Nicotine Degradation Pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 95, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. Green Route to Synthesis of Valuable Chemical 6-Hydroxynicotine from Nicotine in Tobacco Wastes Using Genetically Engineered Agrobacterium Tumefaciens S33. Biotechnol Biofuels 2017, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wei, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, R.; Wen, Y.; Liu, W. A Novel (S)-6-Hydroxynicotine Oxidase Gene from Shinella Sp. Strain HZN7. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 5552–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Ma, Y.; Wen, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, W. Functional Identification of Two Novel Genes from Pseudomonas Sp. Strain HZN6 Involved in the Catabolism of Nicotine. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012, 78, 2154–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, T.E.; Zhao, F. Consumption and Production Waste: Another Externality of Tobacco Use. Tob Control 1999, 8, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civilini, M. Nicotine Decontamination of Tobacco Agro-Industrial Waste and Its Degradation by Micro-Organisms. Waste Management & Research 1997, 15, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Lanying, M.; Wang, S.; He, X.; Wu, G.; Xu, P. Novel Nicotine Oxidoreductase-Encoding Gene Involved in Nicotine Degradation by Pseudomonas Putida Strain S16. Appl Environ Microbiol 2009, 75, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wei, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wen, R.; Wen, Y.; Liu, W. A Novel (S)-6-Hydroxynicotine Oxidase Gene from Shinella Sp. Strain HZN7. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkey, A.A.; Hills, S. Nicotine Removal Process and Product Produced Thereby 1987.

- Wang, M.; Yang, G.; Min, H.; Lv, Z.; Jia, X. Bioaugmentation with the Nicotine-Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas Sp. HF-1 in a Sequencing Batch Reactor Treating Tobacco Wastewater: Degradation Study and Analysis of Its Mechanisms. Water Res 2009, 43, 4187–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Zhu, C.; Shu, M.; Sun, K.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Ye, Z.; Chen, J. Degradation of Nicotine in Tobacco Waste Extract by Newly Isolated Pseudomonas Sp. ZUTSKD. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 6935–6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.S.; Wang, L.J.; He, H.Z.; Wang, M.Z. Effect of Transient Nicotine Load Shock on the Performance of Pseudomonas Sp. HF-1 Bioaugmented Sequencing Batch Reactors. J Chem 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, L.; Yao, Y.; Wang, H.; Min, H.; Lu, Z. Bioremediation of the Tobacco Waste-Contaminated Soil by Pseudomonas Sp. HF-1: Nicotine Degradation and Microbial Community Analysis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013, 97, 6077–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Z.; He, H.Z.; Zheng, X.; Feng, H.J.; Lv, Z.M.; Shen, D.S. Effect of Pseudomonas Sp. HF-1 Inoculum on Construction of a Bioaugmented System for Tobacco Wastewater Treatment: Analysis from Quorum Sensing. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 7945–7955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briški, F.; Kopčić, N.; Ćosić, I.; Kučić, D.; Vuković, M. Biodegradation of Tobacco Waste by Composting: Genetic Identification of Nicotine-Degrading Bacteria and Kinetic Analysis of Transformations in Leachate. Chemical Papers 2012, 66, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, N.; Lalević, B.; Raičević, V.; Radojičić, V. Impact of Composting Conditions on the Nicotine Degradation Rate Using Nicotinophilic Bacteria from Tobacco Waste. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 20, 7787–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Chu, P.; Shi, H.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Zheng, S. Cultivation and Application of Nicotine-Degrading Bacteria and Environmental Functioning in Tobacco Planting Soil. Bioresour Bioprocess 2023, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.N.; Xu, P.; Tang, H.Z.; Meng, J.; Liu, X.L.; Qing, C. “Green” Route to 6-Hydroxy-3-Succinoyl-Pyridine from (S)-Nicotine of Tobacco Waste by Whole Cells of a Pseudomonas Sp. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 6877–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Tang, H.; Xu, P. Green Strategy from Waste to Value-Added-Chemical Production: Efficient Biosynthesis of 6-Hydroxy-3-Succinoyl-Pyridine by an Engineered Biocatalyst. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xu, P.; Tang, H. Sustainable Production of Valuable Compound 3-Succinoyl-Pyridine by Genetically Engineering Pseudomonas Putida Using the Tobacco Waste. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 16411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalache, G.; Babii, C.; Stefan, M.; Motei, D.; Marius, M. Steps towards an Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans Based Biotechnology for Production of 6-Hidroxy-Nicotine. In Proceedings of the 16 th INTERNATIONAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY SCIENTIFIC GEOCONFERENCE ; 2016; pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hrițcu, L.; Ștefan, M.; Brandsch, R.; Mihășan, M. 6-Hydroxy-l-Nicotine from Arthrobacter Nicotinovorans Sustain Spatial Memory Formation by Decreasing Brain Oxidative Stress in Rats. J Physiol Biochem 2013, 69, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hritcu, L.; Stefan, M.; Brandsch, R.; Mihasan, M. Enhanced Behavioral Response by Decreasing Brain Oxidative Stress to 6-Hydroxy-l-Nicotine in Alzheimer’s Disease Rat Model. Neurosci Lett 2015, 591, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritcu, L.; Ionita, R.; Motei, D.E.; Babii, C.; Stefan, M.; Mihasan, M. Nicotine versus 6-Hydroxy-l-Nicotine against Chlorisondamine Induced Memory Impairment and Oxidative Stress in the Rat Hippocampus. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 86, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioniță, R.; Valu, V.M.; Postu, P.A.; Cioancă, O.; Hrițcu, L.; Mihasan, M. 6-Hydroxy-l-Nicotine Effects on Anxiety and Depression in a Rat Model of Chlorisondamine. Farmacia 2017, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Boiangiu, R.S.; Mihasan, M.; Gorgan, D.L.; Stache, B.A.; Petre, B.A.; Hritcu, L. Cotinine and 6-Hydroxy-L-Nicotine Reverses Memory Deficits and Reduces Oxidative Stress in Aβ25-35-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiangiu, R.S.; Mihasan, M.; Gorgan, D.L.; Stache, B.A.; Hritcu, L. Anxiolytic, Promnesic, Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Antioxidant Effects of Cotinine and 6-Hydroxy-L-Nicotine in Scopolamine-Induced Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Lv, M.; Xu, H. Acetylcholinesterase: A Primary Target for Drugs and Insecticides. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 17, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S.S.; Girgis, A.S.; Prakash, A.; Khanna, L.; Khanna, P.; Shalaby, E.M.; Fawzy, N.G.; Jain, S.C. Protective Effects of Aporosa Octandra Bark Extract against D-Galactose Induced Cognitive Impairment and Oxidative Stress in Mice. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Liao, C.; Ge, F.; Ao, J.; Liu, T. Acetylcholine Bidirectionally Regulates Learning and Memory. Journal of Neurorestoratology 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, C.; Bordoni, B. Physiology, Acetylcholine; 2021.

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Farlow, M.R.; Snyder, P.J.; Giacobini, E.; Khachaturian, Z.S. Revisiting the Cholinergic Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease: Emerging Evidence from Translational and Clinical Research. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2019, 6, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K. Cholinesterase Inhibitors as Alzheimer’s Therapeutics (Review). Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihășan, M.; Căpățînă, L.; Neagu, E.; Ștefan, M.; Hrițcu, L. In-Silico Identification of 6-Hydroxy-L-Nicotine as a Novel Neuroprotective Drug. Rom Biotechnol Lett 2013, 18, 8333–8340. [Google Scholar]

- Mocanu, E.M.; Mazarachi, A.L.; Mihasan, M. In Vitro Stability and Antioxidant Potential of the Neuprotective Metabolite 6-Hydroxy-Nicotine. JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY 2018, 19, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, H.; Tanji, K.; Wakabayashi, K.; Matsuura, S.; Itoh, K. Role of the Keap1/Nrf2 Pathway in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pathol Int 2015, 65, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taly, A.; Corringer, P.-J.; Guedin, D.; Lestage, P.; Changeux, J.-P. Nicotinic Receptors: Allosteric Transitions and Therapeutic Targets in the Nervous System. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Maskos, U. Role of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology and Treatment. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, I.; López-Hernández, B.; Ceña, V. Nicotinic Receptors in Neurodegeneration. Curr Neuropharmacol 2013, 11, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvani, A.H.; Levin, E.D. Cognitive Effects of Nicotine. Biol Psychiatry 2001, 49, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Model inducer (dose, route of administration, time of exposure) | Dose of 6HLN, route of administration and time of exposure | Behavioral task | Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratus norvegicus | |||||

| Normal | - | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., for 7 consecutive days |

Y-maze | Improves short-term memory acquisition and increases locomotor activity | [167] |

| Normal | - | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., for 7 consecutive days |

Radial arm-maze | Improves working memory. no effect on long-term memory |

[167] |

| AD | SCOP (0.7 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Y-maze | Improves spatial working memory. no effect on locomotor activity |

[168] |

| AD | SCOP (0.7 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Radial arm-maze | Improves spatial memory formation | [168] |

| AD | CHL (10 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Y-maze | Enhances spatial memory formation | [169] |

| AD | CHL (10 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Radial arm maze | Improves short- and long-term memory | [169] |

| AD | CHL (10 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Elevated plus maze | Anxiolytic properties (increased time and entries in open arms) | [170] |

| AD | CHL (10 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 24 h before testing) | 0.3 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., 30 min before testing |

Forced swimming | Anti-depressant effect (reduce the immobility period) | [170] |

| AD | Aβ25-35 peptide fragment (0.5 mg/ml, 4 µl, i.c.v.) | 0.3 and 0.7 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., for 33 days | Y-maze | Improves spatial recognition memory. Restored the normal locomotor activity. |

[171] |

| AD | Aβ25-35 peptide fragment (0.5 mg/ml, 4 µl, i.c.v.) | 0.3 and 0.7 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., for 33 days |

Radial arm maze | Rescue short- and long-term memory | [171] |

| AD | Aβ25-35 peptide fragment (0.5 mg/ml, 4 µl, i.c.v.) | 0.3 and 0.7 mg/kg, b.w., i.p., for 33 days | Novel object recognition | Improves recognition memory | [171] |

| Danio rerio | |||||

| AD | SCOP (100 µM, immersion, 30 before testing) | 1 and 2 mg/L, immersion, for 3 min |

Y-maze | Rescue spatial recognition memory. Enhances locomotor activity. |

[172] |

| AD | SCOP (100 µM, immersion, 30 before testing) | 1 and 2 mg/L, immersion, for 3 min |

Novel object recognition | Improves recognition memory. | [172] |

| AD | SCOP (100 µM, immersion, 30 before testing) | 1 and 2 mg/L, immersion, for 3 min | Novel tank diving test | Reduces anxiety-like behavior. Induces hyperactivity. |

[172] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).