Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

04 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Construction

2.2. Cultures for Y. lipolytica cultivation and PHA Production

2.3. Growth Rate and PHB Content Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

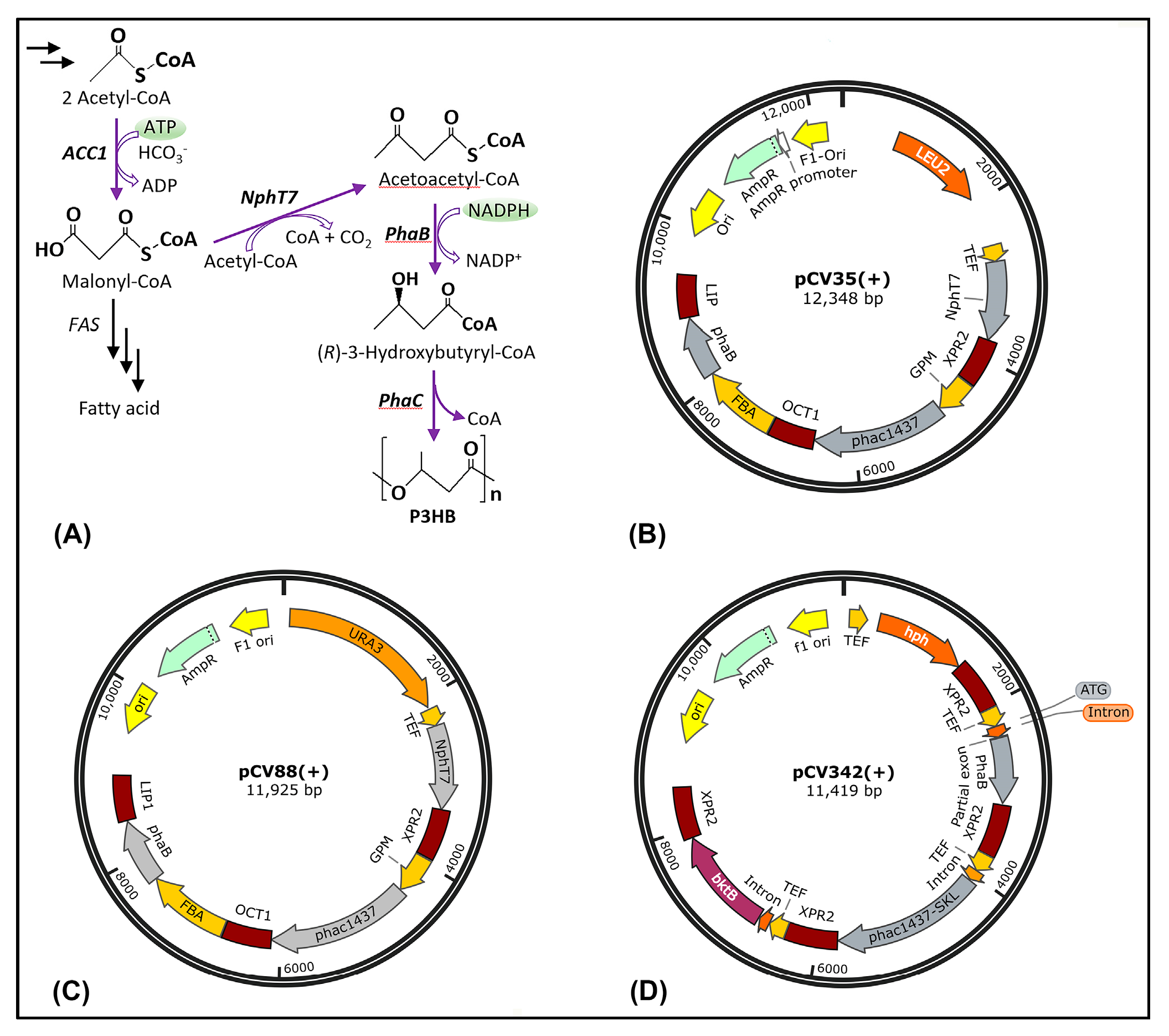

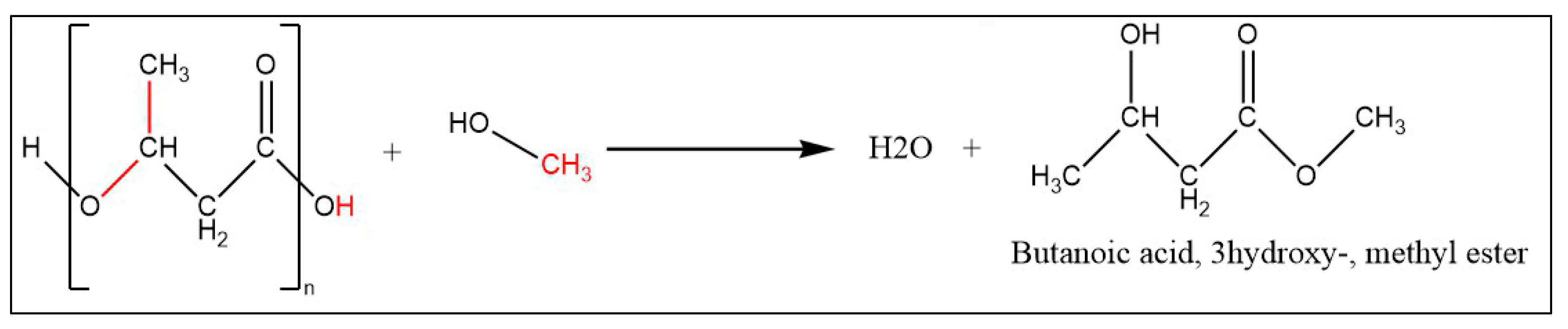

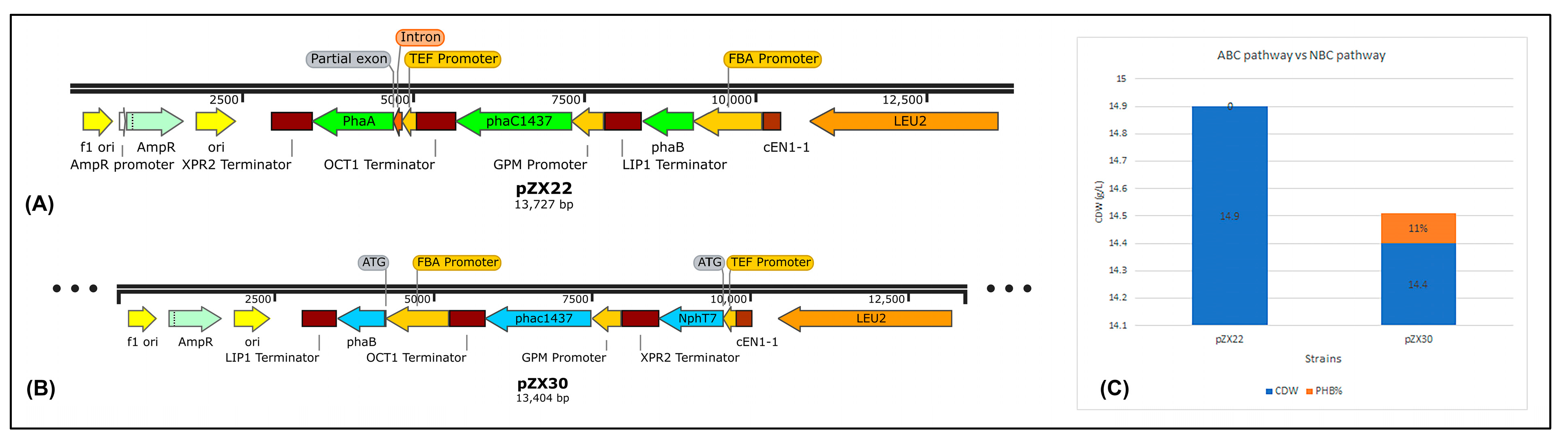

3.1. Metabolic Pathway Design

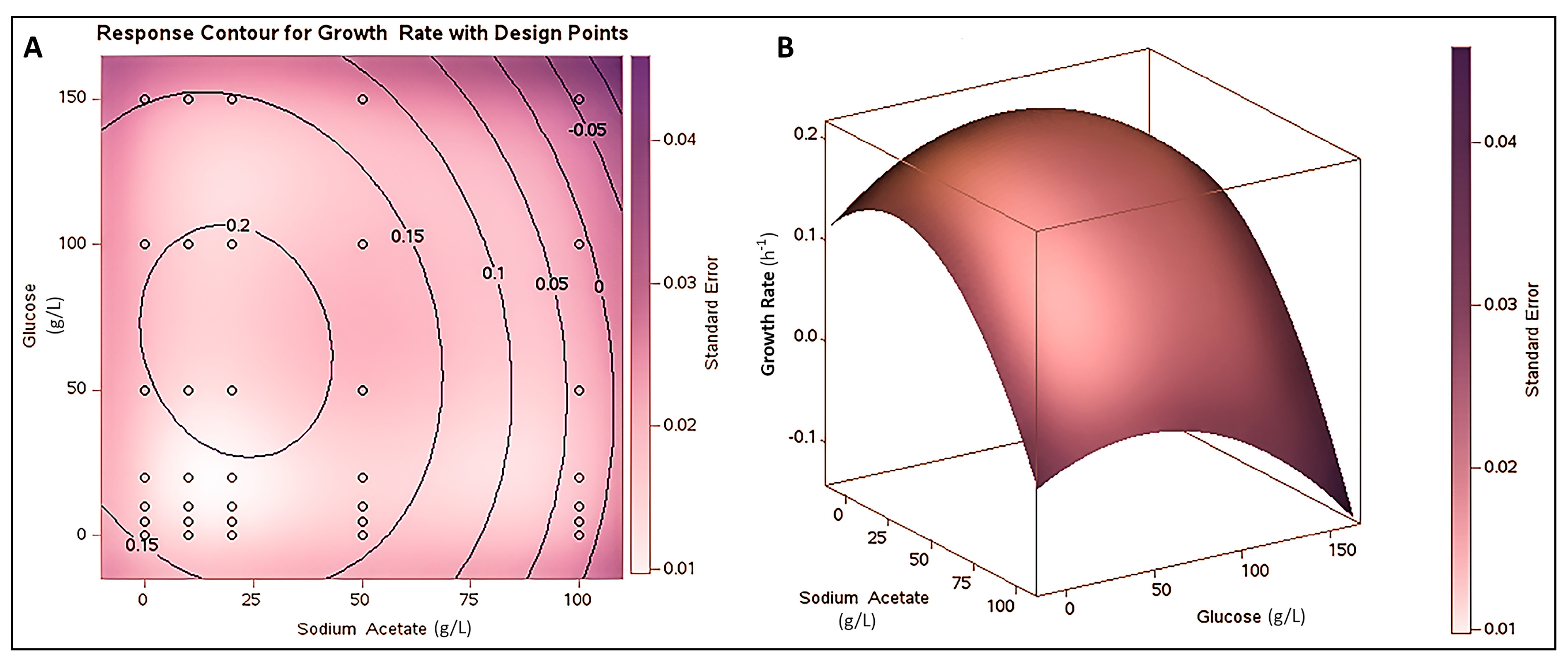

3.2. Co-substrate Strategy for PHB Production

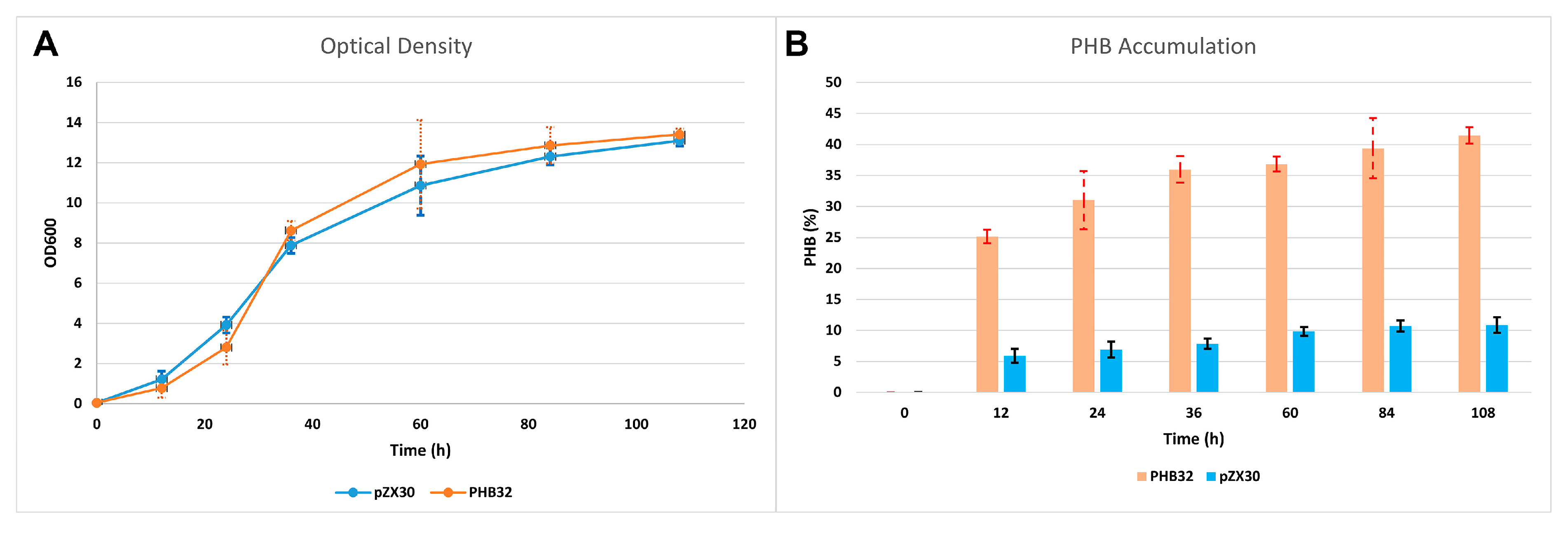

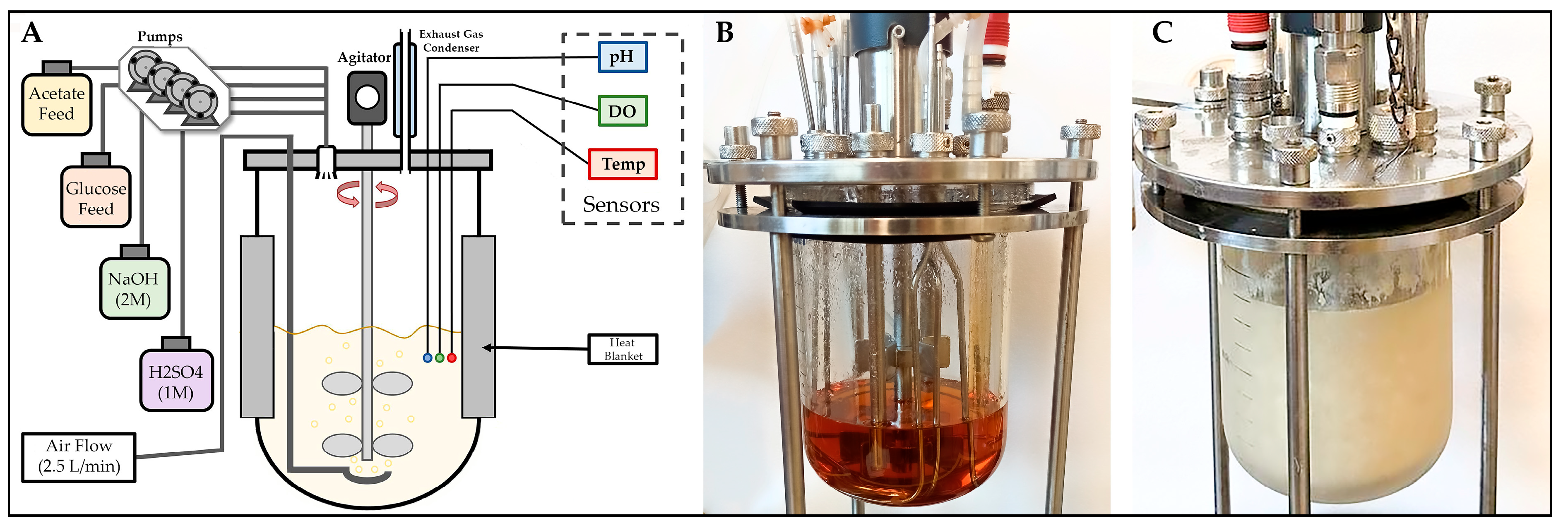

3.3. Bioreactor Production of PHB

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD Plastic Waste Generation in the United States in 2019, with Projections for 2030 and 2060 (in Million Metric Tons) [Graph]. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1339223/us-plastic-waste-generation-outlook/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Karan, H.; Funk, C.; Grabert, M.; Oey, M.; Hankamer, B. Green Bioplastics as Part of a Circular Bioeconomy. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Sehgal, R.; Gupta, R. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Properties and Modifications. Polymer 2020, 212, 123161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, D.; Proença, D.N.; Morais, P. V The Role of Bacterial Polyhydroalkanoate (PHA) in a Sustainable Future: A Review on the Biological Diversity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, E.; Hashemi, S.M.B. Lactic acid production – producing microorganisms and substrates sources-state of art. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, M.J.; Tran, V.G.; Tan, S.-I.; Mishra, S.; Fatma, Z.; Boob, A.; Li, H.; Xue, P.; Martin, T.A.; Zhao, H. Metabolic Engineering: Methodologies and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 5521–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-K.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. What Makes Yarrowia Lipolytica Well Suited for Industry? Trends Biotechnol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, M.R.; López-Núñez, J.C.; Jones, M.A.; Cox, E.J.; Pinkelman, R.J.; Bang, S.S.; Moser, B.R.; Jackson, M.A.; Iten, L.B.; Kurtzman, C.P.; et al. Irradiation of Yarrowia lipolytica NRRL YB-567 creating novel strains with enhanced ammonia and oil production on protein and carbohydrate substrates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9723–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celińska, E. “Fight-Flight-or-Freeze”–How Yarrowia Lipolytica Responds to Stress at Molecular Level? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 3369–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Siloto, R.M.P.; Lehner, R.; Stone, S.J.; Weselake, R.J. Acyl-CoA: Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: Molecular Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 350–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-J.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Wang, L.-R.; Shi, T.-Q.; Sun, X.-M.; Huang, H. Advanced Strategies for the Synthesis of Terpenoids in Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2367–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-J.; Qiao, K.; Liu, N.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica for poly-3-hydroxybutyrate production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Qi, Q.; Madzak, C.; Lin, C.S.K. Exploring medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates production in the engineered yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigouin, C.; Lajus, S.; Ocando, C.; Borsenberger, V.; Nicaud, J.M.; Marty, A.; Avérous, L.; Bordes, F. Production and characterization of two medium-chain-length polydroxyalkanoates by engineered strains of Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beopoulos, A.; Mrozova, Z.; Thevenieau, F.; Le Dall, M.-T.; Hapala, I.; Papanikolaou, S.; Chardot, T.; Nicaud, J.-M. Control of Lipid Accumulation in the Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 7779–7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQualter, R.B.; Petrasovits, L.A.; Gebbie, L.K.; Schweitzer, D.; Blackman, D.M.; Chrysanthopoulos, P.; Hodson, M.P.; Plan, M.R.; Riches, J.D.; Snell, K.D.; et al. The use of an acetoacetyl-CoA synthase in place of a β-ketothiolase enhances poly-3-hydroxybutyrate production in sugarcane mesophyll cells. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 13, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, H.; Rivero, C.P.; Li, C.; Cui, Z.; Qi, Q.; Lin, C.S.K. Robust succinic acid production from crude glycerol using engineered Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo, M.; Hussain, M.S.; Gambill, L.; Blenner, M. Alternative Substrate Metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Higashimori, A.; Wu, L.-J.; Hojo, T.; Kubota, K.; Li, Y.-Y. Phase separation and microbial distribution in the hyperthermophilic-mesophilic-type temperature-phased anaerobic digestion (TPAD) of waste activated sludge (WAS). Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Depraect, O.; Bordel, S.; Lebrero, R.; Santos-Beneit, F.; Börner, R.A.; Börner, T.; Muñoz, R. Inspired by nature: Microbial production, degradation and valorization of biodegradable bioplastics for life-cycle-engineered products. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.-E.; Shin, S.; Rhee, J.-S.; Pan, J.-G. Acetate Metabolism in a pta Mutant of Escherichia coli W3110: Importance of Maintaining Acetyl Coenzyme A Flux for Growth and Survival. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6656–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Sabirova, J.; Soetaert, W.; Ki Carol Lin, S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates Production from Low-Cost Sustainable Raw Materials. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2012, 6, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Mai, J.; Ding, Y.; Wei, Y.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Ji, X.-J. Improving the homologous recombination efficiency of Yarrowia lipolytica by grafting heterologous component from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2020, 11, e00152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredeweg, E.L.; Pomraning, K.R.; Dai, Z.; Nielsen, J.; Kerkhoven, E.J.; Baker, S.E. A molecular genetic toolbox for Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Park, H.M.; Kim, M.; Lee, M.-E.; Jeong, W.-Y.; Chang, J.; Cho, B.-H.; Han, S.O. Isopropanol biosynthesis from crude glycerol using fatty acid precursors via engineered oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.; Houmiel, K.L.; Tran, M.; Mitsky, T.A.; Taylor, N.B.; Padgette, S.R.; Gruys, K.J. Multiple β-Ketothiolases Mediate Poly (β-Hydroxyalkanoate) Copolymer Synthesis in Ralstonia Eutropha. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 1979–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLoache, W.C.; Russ, Z.N.; Dueber, J.E. Towards repurposing the yeast peroxisome for compartmentalizing heterologous metabolic pathways. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, S.; Xiong, X. Metabolic Engineering of Non-carotenoid-Producing Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for the Biosynthesis of Zeaxanthin. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.W.; Sharpe, P.L.; Zhu, Q. Bioengineering of Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia Lipolytica for Lycopene Production. Microb. carotenoids from fungi methods Protoc. 2012, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tourang, M.; Baghdadi, M.; Torang, A.; Sarkhosh, S. Optimization of carbohydrate productivity of Spirulina microalgae as a potential feedstock for bioethanol production. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 16, 1303–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, W.M.; Shafiq, M.; Mokhtar, K.; Aleng, N.A.; Rahim, H.A. RSREG (SAS). J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2016, 15, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Marsafari, M.; Deng, L.; Xu, P. Understanding lipogenesis by dynamically profiling transcriptional activity of lipogenic promoters in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 3167–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larroude, M.; Rossignol, T.; Nicaud, J.-M.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Synthetic biology tools for engineering Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 2150–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, E.; Tomita, T.; Sawa, R.; Nishiyama, M.; Kuzuyama, T. Unprecedented acetoacetyl-coenzyme A synthesizing enzyme of the thiolase superfamily involved in the mevalonate pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 11265–11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, R.J.; Rock, C.O. The Claisen condensation in biology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002, 19, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, T.H.T.; Nguyen, A.D.; Lee, E.Y. Engineering type I methanotrophic bacteria as novel platform for sustainable production of 3-hydroxybutyrate and biodegradable polyhydroxybutyrate from methane and xylose. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, A.; Jacobs, K.; Juretzek, T.; Mauersberger, S.; Barth, G. Overexpression of the ICL1 gene changes the product ratio of citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 77, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, M.; Förster, A.; Mauersberger, S.; Barth, G. Aconitase overexpression changes the product ratio of citric acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 81, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Jiao, L.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Yan, J.; Yan, Y. Overexpression of GRAS Rhizomucor miehei lipase in Yarrowia lipolytica via optimizing promoter, gene dosage and fermentation parameters. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 306, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Tong, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, S. Engineering the Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia Lipolytica for Β-farnesene Overproduction. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, 2100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.O.; Liu, N.; Holinski, K.M.; Emerson, D.F.; Qiao, K.; Woolston, B.M.; Xu, J.; Lazar, Z.; Islam, M.A.; Vidoudez, C.; et al. Synergistic substrate cofeeding stimulates reductive metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, S.; Arora, K.; Kulshrestha, S.; Mehariya, S.; Bhatia, R.K.; Kaur, P.; Kumar, P. Established and Emerging Producers of PHA: Redefining the Possibility. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 3812–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-K.; Dulermo, T.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Nicaud, J.-M. Optimization of odd chain fatty acid production by Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konzock, O.; Zaghen, S.; Norbeck, J. Tolerance of Yarrowia lipolytica to inhibitors commonly found in lignocellulosic hydrolysates. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narisetty, V.; Prabhu, A.A.; Bommareddy, R.R.; Cox, R.; Agrawal, D.; Misra, A.; Haider, M.A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, V. Development of Hypertolerant Strain of Yarrowia lipolytica Accumulating Succinic Acid Using High Levels of Acetate. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 10858–10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, W.; Qian, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, X.; Xin, F.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M.; Ochsenreither, K. Increased Lipid Production in Yarrowia lipolytica from Acetate through Metabolic Engineering and Cosubstrate Fermentation. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, L.; Strehlitz, B.; Aurich, A.; Zehnsdorf, A.; Bley, T. Optimization of Citric Acid Production from Glucose byYarrowia lipolytica. Eng. Life Sci. 2007, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.; Holt, P.; Thykaer, J. Comparing cellular performance of Yarrowia lipolytica during growth on glucose and glycerol in submerged cultivations. AMB Express 2013, 3, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rywińska, A.; Rymowicz, W.; Żarowska, B.; Skrzypiński, A. Comparison of Citric Acid Production from Glycerol and Glucose by Different Strains of Yarrowia Lipolytica. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazeck, J.; Hill, A.; Liu, L.; Knight, R.; Miller, J.; Pan, A.; Otoupal, P.; Alper, H.S. Harnessing Yarrowia lipolytica lipogenesis to create a platform for lipid and biofuel production. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.; Lopes, M.; Miranda, S.M.; Belo, I. Bio-oil production for biodiesel industry by Yarrowia lipolytica from volatile fatty acids in two-stage batch culture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2869–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Muniglia, L.; Chevalot, I.; Aggelis, G.; Marc, I. Accumulation of a Cocoa-Butter-Like Lipid by Yarrowia lipolytica Cultivated on Agro-Industrial Residues. Curr. Microbiol. 2003, 46, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaragnella, N.; Stirpe, M.; Marzulli, D.; Mazzoni, C.; Giannattasio, S. Acid Stress Triggers Resistance to Acetic Acid-Induced Regulated Cell Death throughHog1Activation Which RequiresRTG2in Yeast. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, P.; Mahé, Y.; Thompson, S.; Pandjaitan, R.; Holyoak, C.; Egner, R.; Mühlbauer, M.; Coote, P.; Kuchler, K. The pdr12 ABC transporter is required for the development of weak organic acid resistance in yeast. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 4257–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beilen, J.W.A.; de Mattos, M.J.T.; Hellingwerf, K.J.; Brul, S. Distinct Effects of Sorbic Acid and Acetic Acid on the Electrophysiology and Metabolism of Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5918–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axe, D.D.; Bailey, J.E. Transport of lactate and acetate through the energized cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1995, 47, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaragnella, N.; Bettiga, M. Acetic acid stress in budding yeast: From molecular mechanisms to applications. Yeast 2021, 38, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-J.; Hwang, S.-K.; Hahn, B.-S.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, J.-B.; Kim, Y.-H.; Yang, J.-S.; Ha, S.-H. Authentic seed-specific activity of the Perilla oleosin 19 gene promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis. Cell Biol. Morphog. 2007, 27, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Santala, S.; Stephanopoulos, G. Mixed Carbon Substrates: A Necessary Nuisance or a Missed Opportunity? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomar-Alba, M.; Morcillo-Parra, M.Á.; Olmo, M. lí del Response of Yeast Cells to High Glucose Involves Molecular and Physiological Differences When Compared to Other Osmostress Conditions. FEMS Yeast Res. 2015, 15, fov039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Mostofa, M.G.; Rahman, A.; Islam, R.; Keya, S.S.; Das, A.K.; Miah, G.; Kawser, A.Q.M.R.; Ahsan, S.M.; Hashem, A.; et al. Acetic acid: a cost-effective agent for mitigation of seawater-induced salt toxicity in mung bean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Tran, C.D.; Nguyen, K.H.; Chu, H.D.; Watanabe, Y.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.-S.P. Modulation of osmoprotection and antioxidant defense by exogenously applied acetate enhances cadmium stress tolerance in lentil seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddouche, R.; Delessert, S.; Sabirova, J.; Neuvéglise, C.; Poirier, Y.; Nicaud, J.-M. Roles of Multiple Acyl-CoA Oxidases in the Routing of Carbon Flow towards β-Oxidation and Polyhydroxyalkanoate Biosynthesis in Yarrowia Lipolytica. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010, 10, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primers | Sequences (5'‒3') | GC (%) | Length (mer) | Molecular Mass (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| phaA-F | CCCGGGTTACTTTCTCTCGACGGCC | 64 | 25 | 7560.9 |

| phaA-R | AAGCTTATGACCGACGTGGTGATCGTGTCC | 53 | 30 | 9238.1 |

| phaB-F | CCCGGGAGAGTCGACCTGCAGTTAGCCCATGTGC | 65 | 34 | 10444.8 |

| phaB-R | AAGCTTATGACCCAGCGAATCGCCTACGTCACC | 55 | 33 | 10027.5 |

| phaC1437-F | CCCGGGTTATCGCTCGTGGACGTAAGTGCC | 63 | 30 | 9215.0 |

| phaC1437-R | AAGCTTATGTCTAACAAGTCTAACGACGAGC | 42 | 31 | 9512.3 |

| NphT7-F | CCCGGGTTACCACTCAATCAGGGCAAAGGAAGC | 58 | 33 | 10141.6 |

| NphT7-R | AAGCTTACTGATGTGCGATTTCGAATTATTGGAAC | 37 | 35 | 10800.1 |

| bktB-F | AAGCTTATGACCCGAGAGGTGGTGGTCGTGTCCGG | 60 | 35 | 10884.1 |

| bktB-R | CCCGGGTTAAATTCGTTCGAAGATGGCGGCAATGCC | 56 | 36 | 11101.3 |

| phaC1437-SKL-F | AAGCTTATGTCTAACAAGTCTAACGACGAGCTGAAGTACC | 43 | 40 | 12297.1 |

| phaC1437-SKL-R | CCCGGGTTACAGCTTAGATCGCTCGTGGACGTAAGTGCCAGG | 60 | 42 | 12971.4 |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 0.110 | 6 | 0.0183 | 591.4 | <0.0001 |

| Acetate | 0.459 | 4 | 0.1148 | 3702 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose*Acetate | 0.078 | 24 | 0.00325 | 105.0 | <0.0001 |

| Model | 0.647 | 34 | 0.01904 | 614.0 | <0.0001 |

| Error | 0.002 | 70 | 0.00003 | ||

| Corrected Total | 0.6495 | 104 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).