Submitted:

02 October 2023

Posted:

03 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chronic liver disease

3. Liver inflammation

4. Liver macrophages

5. Macrophage phenotypes M1 and M2

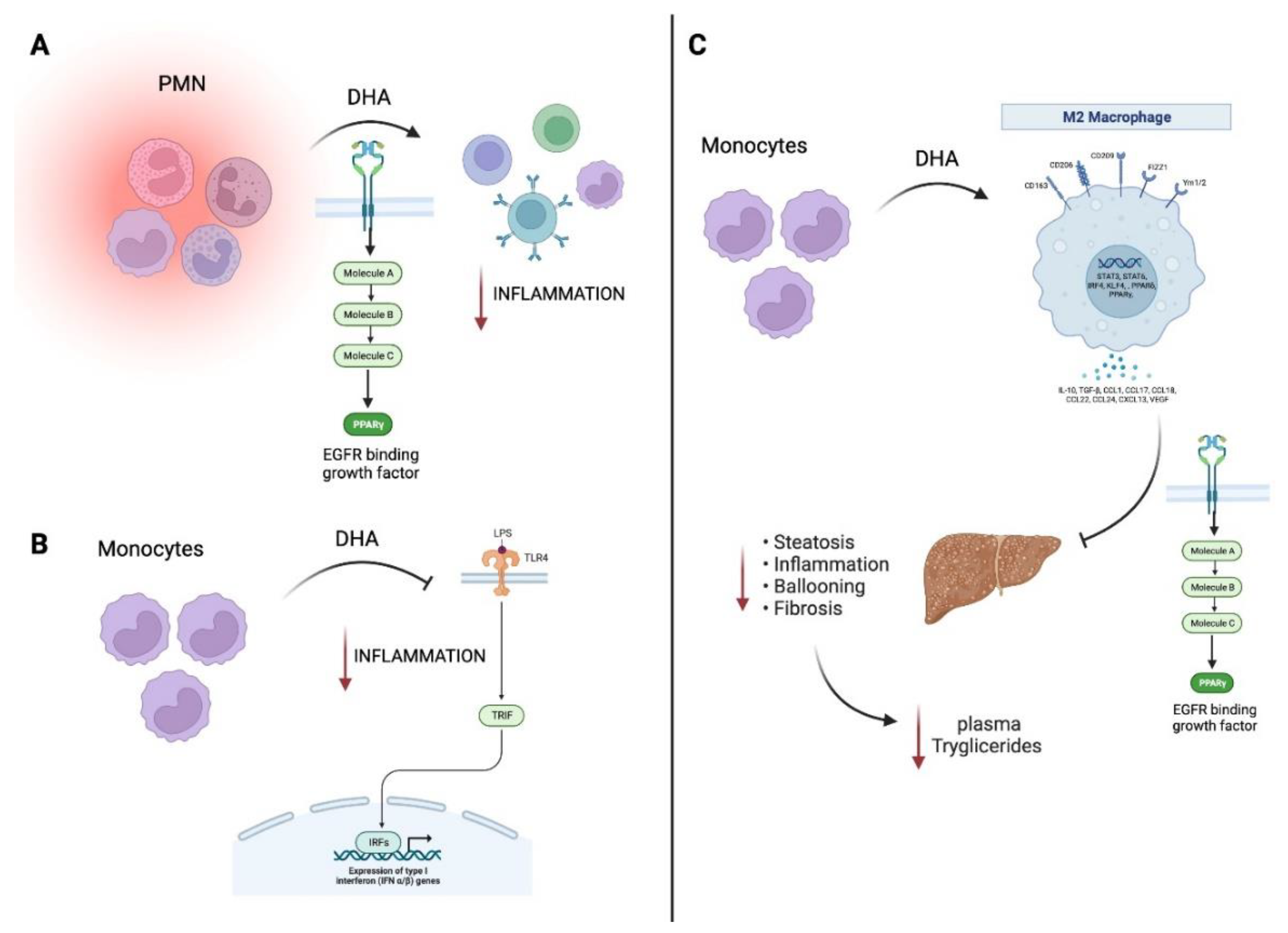

6. Omega-3 fatty acids and their role on M1/M2 macrophage polarization

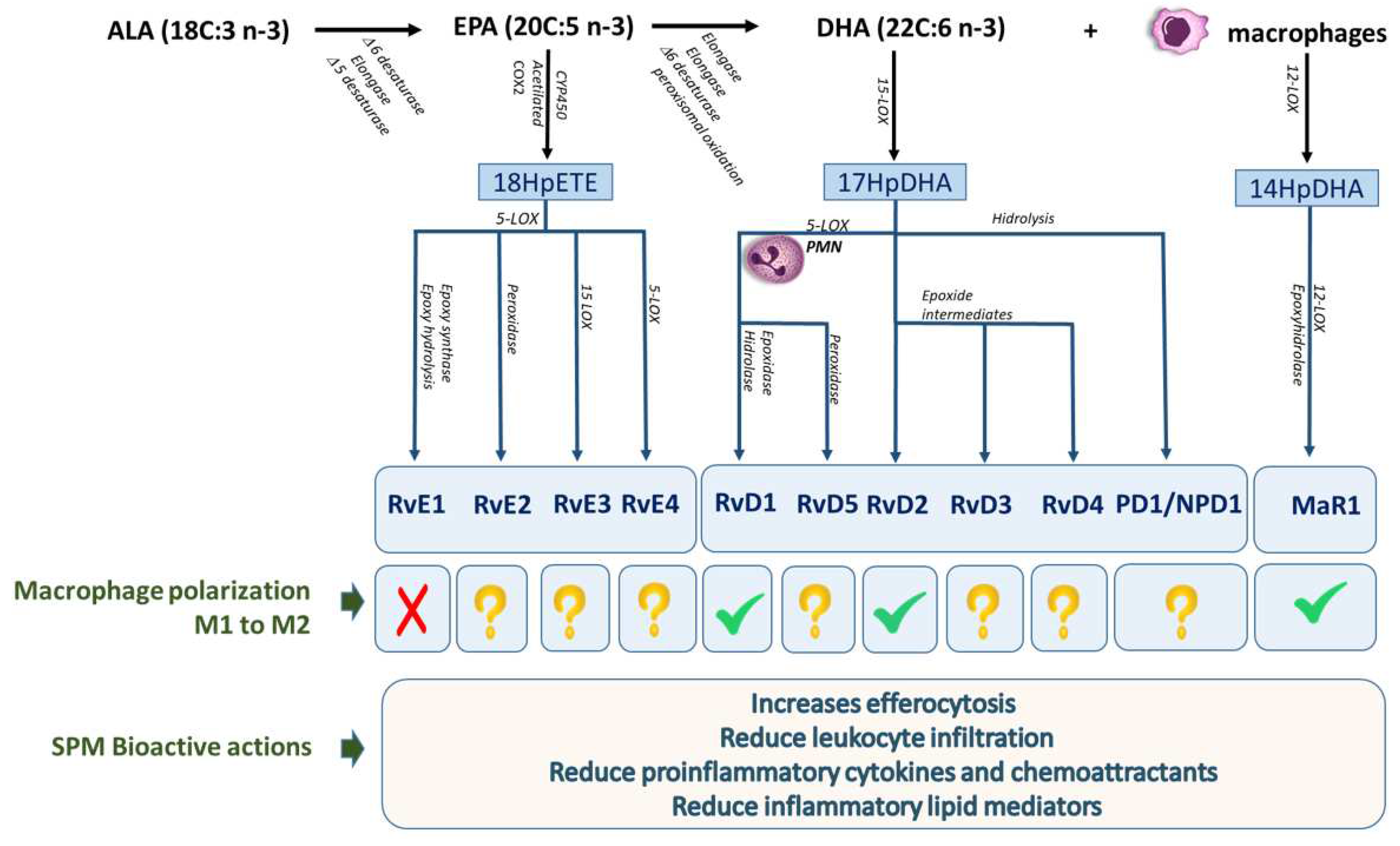

7. Omega-3 lipid mediators

8. The SPMs in relationship to the M1/M2 macrophage phenotype in chronic liver diseases

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyerberg, J.; Bang, H.O.; Stoffersen, E.; Mondaca, S.; Vane, J.R. Eicosaenoic acid and prevention of thrombosis and atherosclerosis? Lancet 1978, 2, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, R.; Ortiz, M.; Hernández-Rodas, M.C.; Echeverría, F.; Videla, L.A. Targeting n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 5250–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vielma, F.H.; Valenzuela, R.; Videla, L.A.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Lipid Mediators as A Potential Immune–Nutritional Intervention: A Molecular and Clinical View in Hepatic Disease and Other Non-Communicable Illnesses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheemerla, S.; Balakrishnan, M. Global Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, C.; Razavi, H.; Loomba, R.; Younossi, Z.; Sanyal, A.J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018, 67, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J. Crosstalk Between Liver Macrophages and Surrounding Cells in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Revin, V.V.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. The impact of interferon-regulatory factors to macrophage differentiation and polarization into M1 and M2. Immunobiology 2018, 223, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariqueo, T.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. Omega-3 derivatives, specialized pro-resolving mediators: Promising therapeutic tools for the treatment of pain in chronic liver disease. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2020, 158, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Li, W.; Ge, Y.; Huang, X.; He, J. A liver fibrosis staging method using cross-contrast network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 130, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelletti, M.M.; Manceau, H.; Puy, H.; Peoc’h, K. Ferroptosis in Liver Diseases: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, M.M.; Akcali, K.C. Liver fibrosis. Turkish J. Gastroenterol. 2018. 29, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Senoo, H.; Mezaki, Y.; Fujiwara, M. The stellate cell system (vitamin A-storing cell system). Anat. Sci. Int. 2017, 92, 387–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Serna-Salas, S.; Damba, T.; Borghesan, M.; Demaria, M.; Moshage, H. Hepatic stellate cell senescence in liver fibrosis: Characteristics, mechanisms and perspectives. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 199, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troeger, J.S.; Mederacke, I.; Gwak, GY.; Dapito, D.H.; Mu, X.; Hsu, C.C.; Pradere, J.P.; Friedman, R.A.; Schwabe, R.F. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, D.A.D.; Hughes, J. The Origins and Functions of Tissue-Resident Macrophages in Kidney Development. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Chawla, A.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature 2013, 496, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A.; Vannella, K.M. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 2016, 44, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röszer, T. Understanding the Biology of Self-Renewing Macrophages. Cells 2018, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wu, H.; Hua, J. Effect of modulation of PPAR-γ activity on Kupffer cells M1/M2 polarization in the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.J.; Barnes, M.; Tang, H.; Pritchard, M.T.; Nagy, L.E. Kupffer cells in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, K.; Nakashima, H.; Ikarashi, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Nakashima, M.; Aosasa, S.; Seki, S.; Yamamoto, J. Mouse CD11b+Kupffer Cells Recruited from Bone Marrow Accelerate Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0136774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, M.; Uchida, T.; Sato, A.; Nakashima, M.; Nakashima, H.; Shono, S.; Habu, Y.; Miyazaki, H.; Hiroi, S.; Seki, S. Characterization of two F4/80-positive Kupffer cell subsets by their function and phenotype in mice. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, M.; Zhu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, B.; Ping, H.; Geng, Q.; Zhu, P. Macrophages: First guards in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. 2020, 250, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J. Macrophage polarization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, S.; Murray, J.B.; O’connor, R. IGF-1 Signalling Regulates Mitochondria Dynamics and Turnover through a Conserved GSK-3β–Nrf2–BNIP3 Pathway. Cells 2020, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: Time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szondy, Z.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Király, R.; Sarang, Z.; Tsay, G.J. Transglutaminase 2 in human diseases. BioMedicine 2017, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.R.; Reyes, J.L.; Iannuzzi, J.; Leung, G.; McKay, D.M. The Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine, Interleukin-6, Enhances the Polarization of Alternatively Activated Macrophages. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e94188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, B.; Nagy, G.; Czimmerer, Z.; Horvath, A.; Hammers, D.W.; Cuaranta-Monroy, I.; Poliska, S.; Tzerpos, P.; Kolostyak, Z.; Hays, T.T.; et al. The Nuclear Receptor PPARγ Controls Progressive Macrophage Polarization as a Ligand-Insensitive Epigenomic Ratchet of Transcriptional Memory. Immunity 2018, 49, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ma, C.; Gong, L.; Guo, Y.; Fu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y. Macrophage Polarization and Its Role in Liver Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 803037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Dyerberg, J.; Sinclair, H.M. The composition of the Eskimo food in north western Greenland. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1980, 33, 2657–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur, J.A.; Bibiloni, M.M.; Sureda, A.; Pons, A. Dietary sources of omega 3 fatty acids: public health risks and benefits. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S23–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, R.; Metherel, A.H.; Cisbani, G.; Smith, M.E.; Chouinard-Watkins, R.; Klievik, B.J.; Videla, L.A.; Bazinet, R.P. Protein concentrations and activities of fatty acid desaturase and elongase enzymes in liver, brain, testicle, and kidney from mice: Substrate dependency. BioFactors 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videla, L.A.; Hernandez-Rodas, M.C.; Metherel, A.H.; Valenzuela, R. Influence of the nutritional status and oxidative stress in the desaturation and elongation of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Impact on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2022, 181, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinicolantonio, J.J.; O’Keefe, J.H. Importance of maintaining a low omega-6/omega-3 ratio for reducing inflammation. Open Heart 2018, 5(2), e000946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Kleczko, E.K.; Nemenoff, R.A. Eicosanoids in Cancer: New Roles in Immunoregulation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 595498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, C.; Ishida, M.; Ohba, H.; Yamashita, H.; Uchida, H.; Yoshizumi, M.; Ishida, T. Fish oil omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuate oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in vascular endothelial cells. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, K.R.; Walker, M.K. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids improve endothelial function in humans at risk for atherosclerosis: A review. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 134, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colussi, G.; Catena, C.; Novello, M.; Bertin, N.; Sechi, L. Impact of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on vascular function and blood pressure: Relevance for cardiovascular outcomes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikura, K.; Heydari, B.; Ge, Y.; Kaneko, K.; Abdullah, S.; Harris, W.S.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Kwong, R.Y. Insulin Resistance Modifies the Effects of Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters on Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction (from the OMEGA-REMODEL Randomized Clinical Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 125, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúñiga-Hernández, J.; Sambra, V.; Echeverría, F.; Videla, L.A.; Valenzuela, R. N-3 PUFAs and their specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators on airway inflammatory response: beneficial effects in the prevention and treatment of respiratory diseases. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 4260–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Tatsuno, I. Prevention of Cardiovascular Events with Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and the Mechanism Involved. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020, 27, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeini, Z.; Toupchian, O.; Vatannejad, A.; Sotoudeh, G.; Teimouri, M.; Ghorbani, M.; et al. Effects of DHA-enriched fish oil on gene expression levels of p53 and NF-kappa B and PPAR-gamma activity in PBMCs of patients with T2DM: A randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, R.G.; Wilson, R.L.; Deike, E.; Gentile, M. Fish Oil Supplementation Lowers C-Reactive Protein Levels Independent of Triglyceride Reduction in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2009, 24, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 48. Pisaniello, A.D.; Psaltis, P.J.; King, P.M.; Liu, G.; Gibson, R.A.; Tan, J.T.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids ameliorate vascular inflammation: A rationale f2or their atheroprotective effects. Atherosclerosis 2021, 324, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Plakidas, A.; Lee, W.H.; Heikkinen, A.; Chanmugam, P.; Bray, G.; et al. Differential modulation of Toll-like receptors by fatty acids: preferential inhibition by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Journal of Lipid Research 2003, 44, 479–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaf A; Kang J.X; Xiao Y.F; Billman G.E. Clinical prevention of sudden cardiac death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and mechanism of prevention of arrhythmias by n-3 fish oils. Circulation 2003, 107, 2646–52.

- Chen, J.; Shearer, G.C.; Chen, Q.; Healy, C.L.; Beyer, A.J.; Nareddy, V.B.; Gerdes, A.M.; Harris, W.S.; O’Connell, T.D.; Wang, D.; et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Prevent Pressure Overload–Induced Cardiac Fibrosis Through Activation of Cyclic GMP/Protein Kinase G Signaling in Cardiac Fibroblasts. Circulation 2011, 123, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, B.; Abdullah, S.; Pottala, J.V.; Shah, R.; Abbasi, S.; Mandry, D.; et al. Effect of Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters on Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction: The OMEGA-REMODEL Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation 2016, 134, 378–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, L.S.D.R.R.; Oliveira, C.P.; Stefano, J.T.; Nogueira, M.A.; da Silva, I.D.C.G.D.; Cordeiro, F.B.; Alves, V.A.F.; Torrinhas, R.S.; Carrilho, F.J.; Puri, P.; et al. Omega-3 PUFA modulate lipogenesis, ER stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction markers in NASH - Proteomic and lipidomic insight. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Zhao, X.G.; Ouyang, P.L.; Guan, Q.; Yang, L.; Peng, F.; Du, H.; Yin, F.; Yan, W.; Yu, W.J.; et al. Combined effect of n-3 fatty acids and phytosterol esters on alleviating hepatic steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease subjects: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, V.C.; Somers, E.C.; Stolberg, V.; Clinton, C.; Chensue, S.; Djuric, Z.; Berman, D.R.; Treadwell, M.C.; Vahratian, A.M.; Mozurkewich, E. Developmental programming for allergy: a secondary analysis of the Mothers, Omega-3, and Mental Health Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 316.e1–316.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupchian, O.; Sotoudeh, G.; Mansoori, A.; Nasli-Esfahani, E.; Djalali, M.; Keshavarz, S.A.; Koohdani, F. Effects of DHA-enriched fish oil on monocyte/macrophage activation marker sCD163, asymmetric dimethyl arginine, and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2016, 10, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, H.L.; Childs, C.E.; Miles, E.A.; Ayres, R.; Noakes, P.S.; Paras-Chavez, C.; Antoun, E.; Lillycrop, K.A.; Calder, P.C. Dysregulation of Subcutaneous White Adipose Tissue Inflammatory Environment Modelling in Non-Insulin Resistant Obesity and Responses to Omega-3 Fatty Acids – A Double Blind, Randomised Clinical Trial. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 922654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurak V.C; Lien V; Field C.J; Goruk S.D; Pramuk K; Clandinin M.T. Long-chain polyunsaturated fat supplementation in children with low docosahexaenoic acid intakes alters immune phenotypes compared with placebo. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008, 46, 570–579.

- Thies, F.; MC Garry, J.; Yaqoob, P.; Rerkasem, K.; Williams, J.; Shearman, C.P.; Gallagher, P.J.; Calder, P.C.; Grimble, R.F. Association of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with stability of atherosclerotic plaques: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003, 361, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, A.; Fukuda, D.; Tanaka, K.; Higashikuni, Y.; Hirata, Y.; Nishimoto, S.; Yagi, S.; Yamada, H.; Soeki, T.; Wakatsuki, T.; et al. Combination of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces atherogenesis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by inhibiting macrophage activation. Atherosclerosis 2016, 254, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, T.; Shimada, K.; Fukao, K.; Sai, E.; Sato-Okabayashi, Y.; Matsumori, R.; Shiozawa, T.; Alshahi, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Tada, N.; et al. Omega 3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Suppress the Development of Aortic Aneurysms Through the Inhibition of Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokin, A.V.; Arnardottir, H.; Svirydava, M.; Ng, Q.; Baumer, Y.; Berg, A.; Pantoja, C.J.; Florida, E.M.; Teague, H.L.; Yang, Z.-H.; et al. Comparison of the dietary omega-3 fatty acids impact on murine psoriasis-like skin inflammation and associated lipid dysfunction. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 117, 109348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Khor, T.O.; Saw, C.L.L.; Lin, W.; Wu, T.; Huang, Y.; Kong, A.-N.T. Role of Nrf2 in Suppressing LPS-Induced Inflammation in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages by Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Docosahexaenoic Acid and Eicosapentaenoic Acid. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 2185–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, O.; Hishikawa, K.; Kamiura, N.; Nakakuki, M.; Kawano, H.; Mizuguchi, K.; Fujita, T. Eicosapentaenoic acid regulates IκBα and prevents tubulointerstitial injury in kidney. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 669, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, H.R.H.; Anbar, H.S.; Rabei, M.R.; Adel, M.; El-Gamal, R. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids attenuate methotrexate-induced apoptosis and suppression of splenic T, B-Lymphocytes and macrophages with modulation of expression of CD3, CD20 and CD68. Tissue Cell 2021, 72, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontoria-Oviedo, I.; Amaro-Prellezo, E.; Castellano, D.; Venegas-Venegas, E.; González-Santos, F.; Ruiz-Saurí, A.; Pelacho, B.; Prósper, F.; del Caz, M.D.P.; Sepúlveda, P. Topical Administration of a Marine Oil Rich in Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Accelerates Wound Healing in Diabetic db/db Mice through Angiogenesis and Macrophage Polarization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, F.K.; Andre, A.; Prieur, X.; Loirand, G.; Meynier, A.; Krempf, M.; Nguyen, P.; Ouguerram, K. n-3 PUFA prevent metabolic disturbances associated with obesity and improve endothelial function in golden Syrian hamsters fed with a high-fat diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 107, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam-Ndoul, B.; Guénard, F.; Barbier, O.; Vohl, M.-C. Effect of different concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids on stimulated THP-1 macrophages. Genes Nutr. 2017, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, A.; Ariyoshi, W.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hikiji, H.; Nishihara, T.; Okinaga, T. Docosahexaenoic acid enhances M2 macrophage polarization via the p38 signaling pathway and autophagy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 12604–12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Kwon, K.; Bae, E.J.; Park, B. Enhanced M2 macrophage polarization in high n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid transgenic mice fed a high-fat diet. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2481–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontoria-Oviedo, I.; Amaro-Prellezo, E.; Castellano, D.; Venegas-Venegas, E.; González-Santos, F.; Ruiz-Saurí, A.; Pelacho, B.; Prósper, F.; del Caz, M.D.P.; Sepúlveda, P. Topical Administration of a Marine Oil Rich in Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Accelerates Wound Healing in Diabetic db/db Mice through Angiogenesis and Macrophage Polarization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpino, G.; Nobili, V.; Renzi, A.; De Stefanis, C.; Stronati, L.; Franchitto, A.; Alisi, A.; Onori, P.; De Vito, R.; Alpini, G.; et al. Macrophage activation in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) correlates with hepatic progenitor cell response via wnt3a pathway. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0157246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Recchiuti, A.; Chiang, N. Novel proresolving aspirin-triggered DHA pathway. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C.; Balas, L.; Bazan, N.G.; Brenna, J.T.; Chiang, N.; Souza, F.d.C.; Dalli, J.; Durand, T.; Galano, J.-M.; Lein, P.J.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101165–101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo-Garcia, L.; Achon-Tunon, M.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, M.P. The influence of the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention and promotion of cancer. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, C.; Birklein, F. Resolvins and inflammatory pain. F1000 Med. Rep. 2011, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. Immuno-resolving ability of resolvins, protectins, and maresins derived from omega-3 fatty acids in metabolic syndrome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, e1900824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divanovic, S.; Dalli, J.; Jorge-Nebert, L.F.; Flick, L.M.; Gálvez-Peralta, M.; Boespflug, N.D.; Stankiewicz, T.E.; Fitzgerald, J.M.; Somarathna, M.; Karp, C.L.; et al. Contributions of the Three CYP1 Monooxygenases to Pro-Inflammatory and Inflammation-Resolution Lipid Mediator Pathways. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 3347–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Petasis, N.A. Resolvins and Protectins in Inflammation Resolution. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5922–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Winkler, J.W.; Chiang, N. Protectins and maresins: New pro-resolving families of mediators in acute inflammation and resolution bioactive metabolome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1851, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, P.C.; Arnardottir, H.; Sanger, J.M.; Fichtner, D.; Keyes, G.S.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D3 multi-level proresolving actions are host protective during infection. Prostaglandins, Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2016, 138, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, J.; Orr, S.; Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Petasis, N.; Serhan, C. Resolvin D4 Potent Antiiinflammatory Proresolving Actions Confirmed via Total Synthesis. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 285–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, T.; Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Canova, D.F.; Aursnes, M.; Bonnet, D.; Alric, L.; Vergnolle, N.; Deraison, C.; Hansen, T.V.; et al. Protectin D1n-3 DPA and resolvin D5n-3 DPA are effectors of intestinal protection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017, 114, 3963–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.L.; Kakazu, A.H.; He, J.; Jun, B.; Bazan, N.G.; Bazan, H.E.P. Novel RvD6 stereoisomer induces corneal nerve regeneration and wound healing post-injury by modulating trigeminal transcriptomic signature. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheselli, V.L.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Arita, M.; Hong, S.; Antony, R.; Kristopher Sheets, K.; Winkler, J.W.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. Neuroprotectin D1/protectin D1 stereoselective and specific binding with human retinal pigment epithelial cells and neutrophils. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2010, 82, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Yang, R.; Martinod, K.; Kasuga, K.; Pillai, P.S.; Porter, T.F.; Oh, S.F.; Spite, M. Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, D.; Gilligan, M.M.; Serhan, C.N.; Kashfi, K. Resolution of inflammation: An organizing principle in biology and medicine. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 227, 107879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Dalli, J.; Karamnov, S.; Choi, A.; Park, C.-K.; Xu, Z.-Z.; Ji, R.-R.; Zhu, M.; Petasis, N.A. Macrophage proresolving mediator maresin 1 stimulates tissue regeneration and controls pain. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, A.; Zandee, S.; Mastrogiovanni, M.; Charabati, M.; Rubbo, H.; Prat, A.; López-Vales, R. Administration of Maresin-1 ameliorates the physiopathology of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, W.; Li, T.; Li, L.; Hu, L.; Cao, J. Maresin 1 attenuates the inflammatory response and mitochondrial damage in mice with cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in a SIRT1-dependent manner. Brain Res. 2019, 1711, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahyuni, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Tanaka, S.; Miyake, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Bahtiar, A.; Mori, S.; Kametani, Y.; Tomimatsu, M.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. Maresin-1 induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through IGF-1 paracrine pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 321, C82–C93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, X.-Y.; Li, L.-C.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, Y.-M.; Tian, Y.; Sheng, Y.-M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.-G.; Jin, S.-W. γδ T/Interleukin-17A Contributes to the Effect of Maresin Conjugates in Tissue Regeneration 1 on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cardiac Injury. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 674542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Qin, Z.; Yuliang Zhao, Y.; Su, B. Maresin 1 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury via inhibiting NOX4/ROS/NF-κB pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 782660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, B.; Wu, J.; Pu, Y.; Wan, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, M.; Luo, L.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Maresin 1 alleviates diabetic kidney disease via LGR6-mediated cAMP-SOD2-ROS pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 7177889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, G.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Fuentealba, R.; Treuer, A.V.; Castillo, I.; González, D.R.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. Maresin 1, a Proresolving Lipid Mediator, Ameliorates Liver Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Stimulates Hepatocyte Proliferation in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.J.; Sabaj, M.; Tolosa, G.; Herrera Vielma, F.; Zúñiga, M.J.; González, D.R.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. Maresin-1 prevents liver fibrosis by targeting Nrf2 and NF-κB, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. Cells 2021, 10, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Fu, G.; Li, W.; Sun, P.; Loughran, P.A.; Deng, M.; Scott, M.J.; Billiar, T.R. Maresin 1 protects the liver against ischemia/reperfusion injury via the ALXR/Akt signaling pathway. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, J.; Serhan, C.N. Specific lipid mediator signatures of human phagocytes: microparticles stimulate macrophage efferocytosis and pro-resolving mediators. Blood 2012, 120, e60–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.S.; Porter, D.W.; Orandle, M.S.; Green, B.J.; Barnes, M.; Croston, T.L.; Wolfarth, M.G.; Battelli, L.A.; Andrew, M.E.; Beezhold, D.H.; et al. Resolution of pulmonary inflammation induced by carbon nanotubes and fullerenes in mice: Role of macrophage polarization. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titos, E.; Rius, B.; González-Périz, A.; López-Vicario, C.; Morán-Salvador, E.; Martínez-Clemente, M.; Arroyo, V.; Clària, J. Resolvin D1 and Its Precursor Docosahexaenoic Acid Promote Resolution of Adipose Tissue Inflammation by Eliciting Macrophage Polarization toward an M2-Like Phenotype. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 5408–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Zhu, M.; Vlasenko, N.A.; Deng, B.; Haeggström, J.Z.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. The novel 13S,14S-epoxy-maresinis converted by human macrophages to maresin 1 (MaR1), inhibits leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H), and shifts macrophage phenotype. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 2573–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.-H.; Shin, K.-O.; Kim, J.-Y.; Khadka, D.B.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Cho, W.-J.; Cha, J.-Y.; Lee, B.-J.; Lee, M.-O. A maresin 1/RORα/12-lipoxygenase autoregulatory circuit prevents inflammation and progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Ye, D.; Wan, J. Maresin 1 alleviates the inflammatory response, reduces oxidative stress and protects against cardiac injury in LPS-induced mice. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 105. Ma, M.Q.; Zheng, S.S.; Chen, H.L.; Xu, H.B.; Zhang, D.L.; Zhang, Y.A.; Xiang, S.Y.; Cheng, B.H.; Jin, S.W.; Fu, P.H. Protectin conjugates in tissue regeneration 1 inhibits macrophage pyroptosis by restricting NLRP3 inflammasome assembly to mitigate sepsis via the cAMP-PKA pathway. Lab. Invest. 2023, 103, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, S.; Xie, Y.-K.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.-Z.; Ji, R.-R. GPR37 regulates macrophage phagocytosis and resolution of inflammatory pain. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3568–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-W.; Lee, S.-M. Resolvin D1 protects the liver from ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing M2 macrophage polarization and efferocytosis. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1861, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; Feng, N.; Cui, J.; Wang, S.; Qu, H.; Fu, G.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Resolvin D1 and D2 inhibit tumour growth and inflammation via modulating macrophage polarization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 8045–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yin, G.; Xu, W.; Jiang, H. Resolvin D1 inhibits the proliferation of lipopolysaccharide-treated HepG2 hepatoblastoma and PLC/PRF/5 hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting the MAPK pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 3603–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Meier, E.M.; Eisinger, K.; Krautbauer, S.; Buechler, C. Resolvin E1 and chemerin C15 peptide do not improve rodent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015, 98, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, H.; Hua, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, R. Resolvin D1 and E1 alleviate the progress of hepatitis toward liver cancer in long-term concanavalin A-induced mice through inhibition of NF-κB activity. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.J.; Herrera, F.; Donoso, W.; Castillo, I.; Orrego, R.; González, D.R.; Zúñiga-Hernández, J. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediator Resolvin E1 Mitigates the Progress of Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Sprague-Dawley Rats by Attenuating Fibrogenesis and Restricting Proliferation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, W.; Guo, K.; Yi, L.; Gong, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhong, W. Resolvin E1 reduces hepatic fibrosis in mice with Schistosoma japonicum infection. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 1481–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yin, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Zeng, X.; Yang, W.; i Zhang, R.; Tang, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. Maresin 1 mitigates concanavalin A-induced acute liver injury in mice by inhibiting ROS-mediated activation of NF-κB signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 147, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tao, K.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Li, R. Maresin 1 protects against lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver injury by inhibiting macrophage pyroptosis and inflammatory response. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 195, 114863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Du, K.; Jin, N.; Tang, B.; Zhang, W. Macrophage in liver Fibrosis: Identities and mechanisms. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 120, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koncz, G.; Jenei, V.; Tóth, M.; Váradi, E.; Kardos, B.; Bácsi, A.; Mázló, A. Damage-mediated macrophage polarization in sterile inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1169560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yang, H.; et al. Regulatory mechanism of M1/M2 macrophage polarization in the development of autoimmune diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 8821610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Huang, X.; Shi, J. Macrophages Serve as Bidirectional Regulators and Potential Therapeutic Targets for Liver Fibrosis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 81, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Omega-3 | Mechanism | Effect | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical trials analysis (A : | EPA+DHA) | ||

| A | Decrease of T helper 2/T helper 1 chemokines | Lower macrophage-derived chemokine/interferon-inducible protein | Cord plasma from newborns from pregnancy-related depressive mothers (prenatal supplementation55 |

| A | Decrease levels of sCD63* | Decrease of triglycerides, waist to height ratio and waist circumference | Type 2 diabetic patients 56 |

| A | Modulation of Wnt/beta-catenine pathways**. | White adipose tissue downregulation of inflammatory pathways with less macrophage infiltration | Obese subjects57 |

| A | Enhance of CD54 macrophages*** | Less T CD8+/T CD4+ after immune challenger and greater production of IL-10 (an anti-inflammatory cytokine) | Children, (ages 5-7 years) who had low intakes of DHA58 |

| A | Less macrophage in atherosclerotic plaques | Improvement of atherosclerotic plaque morphology (tin fibrous cap) | Patients awaiting carotid endartectomy59 |

| Animals model | (A: EPA+DHA) (B: EPA) | (C. EPA or DHA) | |

| A | Attenuated the development and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques and reduction of TLR4 | Suppressed atherogenesis | Apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe-/-) mice60 |

| A | Decreased of TNF-α, MCP-1, TGF β. And arginase 2, this last one is a marker of pro-inflammatory macrophages | Reduction of aneurism formation and macrophage infiltration | Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) animal model61 |

| C | increased levels of resolvin D5, protectin DX and maresin 2 in the mouse skin | Decrease proinflammatory cytokines altered psoriasis macrophage phenotypes and lipid oxidation, modulating psoriasis skin inflammation | K14-Rac1V12 mouse model62 |

| A | Induction of Nrf2 signaling | Decrease proinflammatory cytokines, iNOS and COX-2 | Nrf2 knockout (-/-; KO) mice63 |

| B | Down-regulation of NF-κB activation and regulated genes | Inhibited tubule-interstitial injury and the infiltration of macrophages into tubule-interstitial lesions | Thy-1 nephritis model64 |

| A | Reduce TNFα, caspase-3 and could increasing splenic GSH Bcl-2.Restorating macrophages, B- and T- lymphocytes. | Decrease the Methotrexate-induced histopathological injury. | Methotrexato-induced splenic suppression on Sprague-Dawley rats65 |

| A | Reduced pro-inflammatory macrophages | Promoted wound closure by accelerating the resolution of inflammation | Wound healing in db/db mice 66 |

| A | Reduction of hepatic SREBP-1c and enhancement of PPARγ nuclear receptor | Lower concentration on plasma lipids, triglycerides and liver lipid content. Enhance of endothelial function | HFD in hamsters67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).