1. Introduction

Originating in Wuhan, China, in early December 2019, coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly, with cases confirmed in every country. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, is still a persistent threat to global public health, resulting in widespread morbidity and mortality and highly intensive care unit use. SARS-CoV-2 targets both the respiratory and extrapulmonary systems. COVID-19 can cause acute lung injury, myocardial infarction, liver injury, kidney injury, and other injuries [

1] endothelium dysfunction is evidence of COVID-19 syndrome [

2].

Clinical symptoms varied in severity from mild to severe cases. The disease is characterized by pneumonia, fatigue, fever of 38°C or higher, cough, dyspnea, headache, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pains, fatigue, and muscle pains, as well as changes in taste and smell [

3].

During this pandemic, novel variants of SARS-CoV-2 have emerged as a major challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) classified some variants as variants of interest (VOIs) and variants of concern (VOCs) in late 2020, due to the emergence of variants that presented a potential threat to global public health [

4]

The Delta variant prevailed during the 4th wave of the epidemic in Greece, from mid-summer to the end of 2021, followed by the Omicron variant and the 5th wave to the period during which the Omicron variant was dominant (approximately January to May of 2022). Despite the disease's milder severity, the Omicron variant is more contagious than the Delta variant [

5,

6]. In this period immunity was based on protection due to prior vaccination and infection [

7].

Severe cases of COVID-19 are characterized by hyper-inflammatory and thrombotic episodes, suggesting that one of the major targets of this disease is endothelium, one of the body’s largest organs.

Endothelial cells line the inner layer of blood vessels, which is considered a partially transparent biomechanical barrier, and vessel gatekeeper are responsible for preserving micro- and macrovascular health by identifying pathogen/danger signs and secreting vasoactive molecules [

8]. In addition, endothelial cells release pro-fibrinolytic agents that initiate fibrinolysis to degrade clots [

9]

In recent decades, an improved understanding of the biological functions of the endothelium has led to its identification as a ubiquitous tissue that modulates the tone of the blood vessels, cell behavior, innate immunity, cell interactions, and cellular metabolism in the vessels [

10].

The endothelial angiopoietin/Tie2 system is involved in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Endothelial cells primarily express and contain the tyrosine kinase receptor Tie2. The activity of Tie2 is modulated by its ligands, Ang–1 and Ang–2, which are vascular growth factors that contribute to the process of angiogenesis. They act in an agonist/ antagonist manner and may alter the structure and integrity of the vascular endothelium directly or indirectly [

11,

12].

Ang-1 promotes barrier function by reorganizing endothelial cells. During inactivation, pericytes secrete angiopoietin 1, which plays a role as a Tie2 agonist and contributes to the maintenance of an effective endothelial barrier. Depending on the circumstances, angiopoietin-2 is either an antagonist or a partial agonist of the Tie2 receptor. Weibel-Palade bodies release angiopoietin-2 during pathological conditions, which binds antagonistically to the Tie2 receptor [

13]. Thus, downstream Tie2 signaling is deactivated, cell–cell junctions deteriorate, and endothelial hyperpermeability and vascular leakage are induced. Therefore, alterations in the endothelial angiopoietin/Tie2 system may contribute to organ injury during critical illness. Therefore, endothelial angiopoietin/Tie2 system disruptions may contribute to organ damage during critical illness [

11], [

14]. In the face of endothelial dysfunction, endothelial cells trigger fibrin formation, as well as platelet adhesion and aggregation [

9]

The study aimed to identify the appropriate prognostically significant biomarkers and provide the ability to stratify the risk of thrombosis in COVID-19 patients. Many studies have suggested that an increase in Ang-2 and a decrease in Ang-1 may be indicative of a pro-inflammatory state that is best described by the Ang-2 to Ang-1 ratio [

15], [

16]. Considering these findings, our primary objective was to examine the relationship between decreased Ang-1 and increased Ang-2 concentrations and the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio with clinical outcomes [

16,

17]. They may appear valid as disease severity and survival biomarkers and a prospective and promising therapeutic target.

2. Results

Among 90 individuals, 51 males (56.7%) and 39 females (43.3%) divided into three groups with specific disease severity. Specifically, 30 patients with COVID-19 were hospitalized in intensive care units (ICU), 30 patients with COVID-19 outside of intensive care units in the hospital wards (non-ICU), and 30 asymptomatic non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (outpatient).

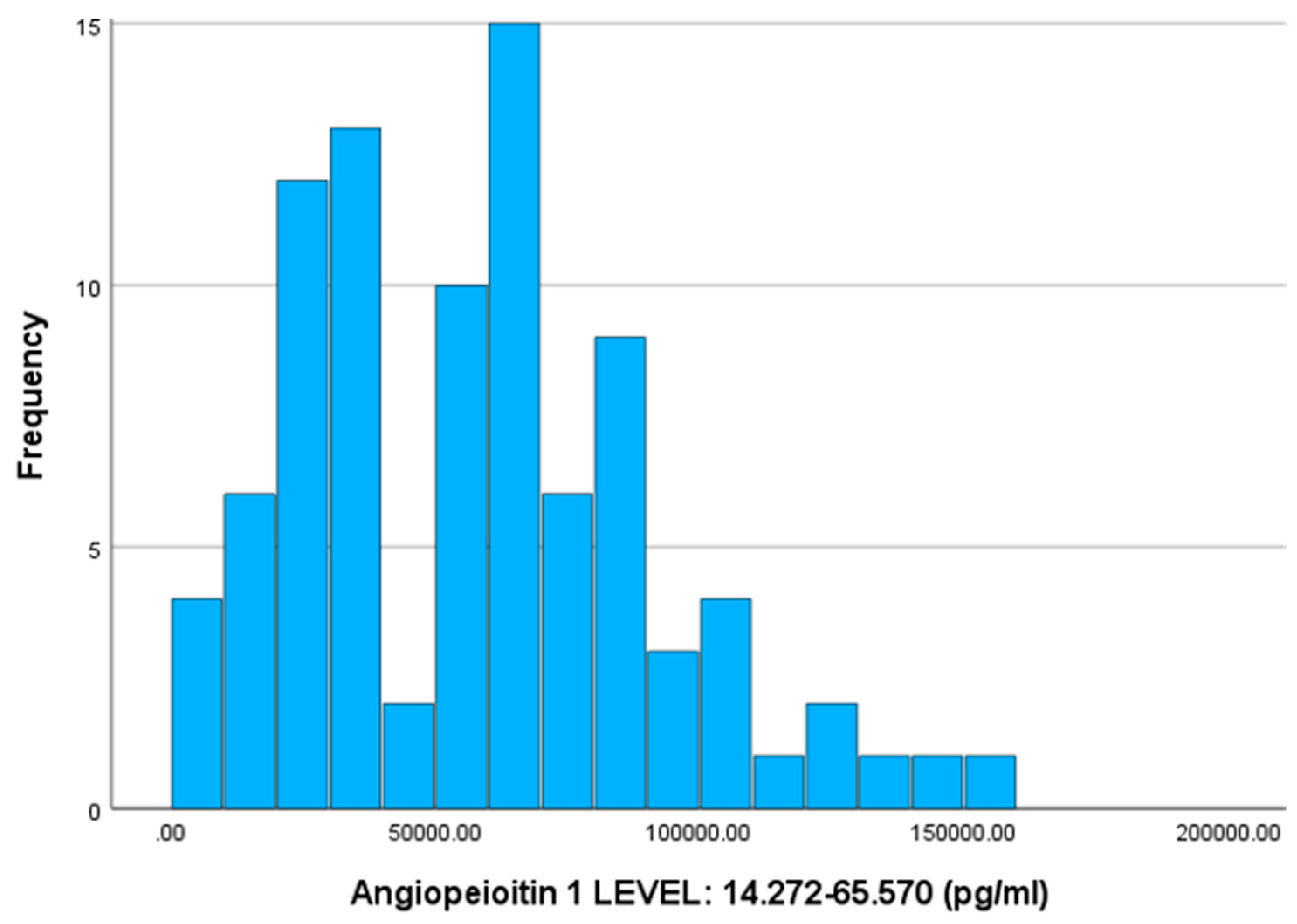

2.1. Results of Ang-1

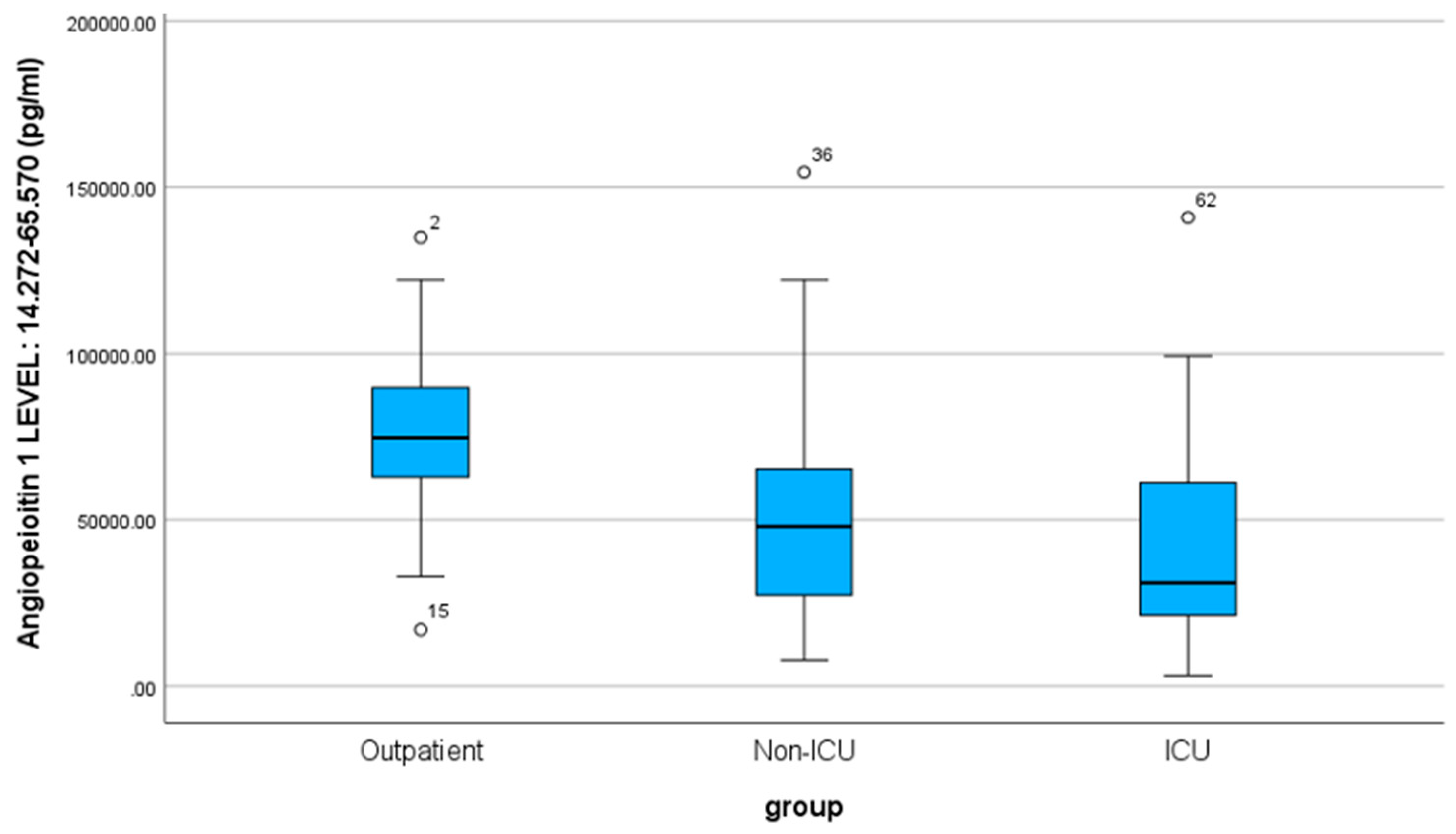

The mean value of Ang-1 is 57102.23 pg/ml, with a standard deviation of 33876.23 (SD). Correspondingly, for the three specific patient groups, the values are as follows: outpatients 77126.83 pg/ml (SD 26539.95), non-ICU 51805.47 pg/ml (SD 34254.29), and ICU 42374.40 pg/ml (SD 31240.87). The outpatients, non-ICU, and ICU medians are 74450 pg/ml, 47890 pg/ml, and 31070 pg/ml, respectively.

According to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney-U test, there is a statistically significant difference between the outpatient - non-ICU (Sig. < 0.001) and outpatient - ICU (Sig. < 0.001) groups. In contrast, the mean values between the non-ICU - ICU groups do not differ significantly (Sig. = 0.243) regarding the angiopoietin-1 index.

Figure 1.

Histogram of Frequencies for Angiopoietin-1.

Figure 1.

Histogram of Frequencies for Angiopoietin-1.

Figure 2.

Box Plot of Angiopoietin-1 for the three groups of patients.

Figure 2.

Box Plot of Angiopoietin-1 for the three groups of patients.

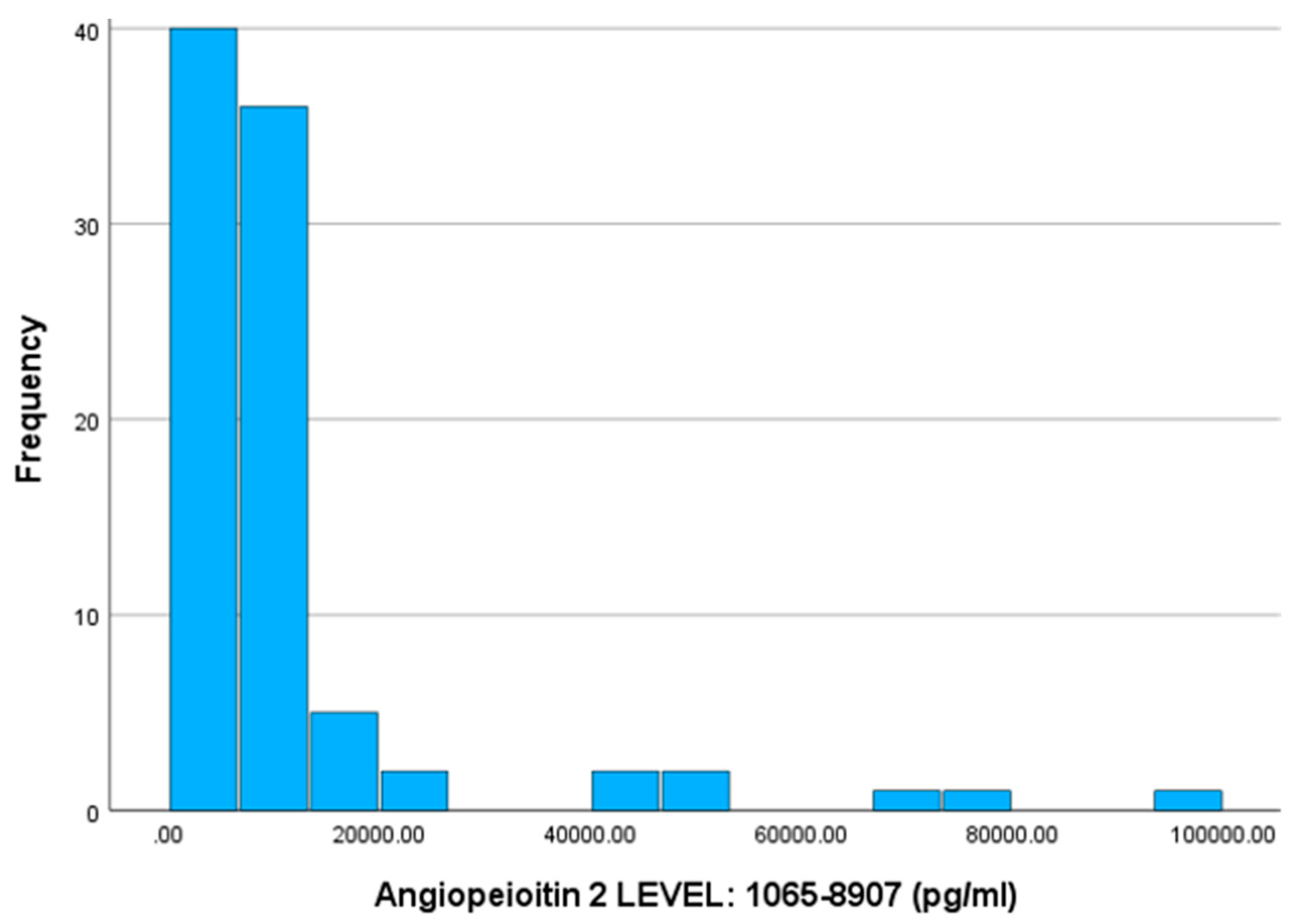

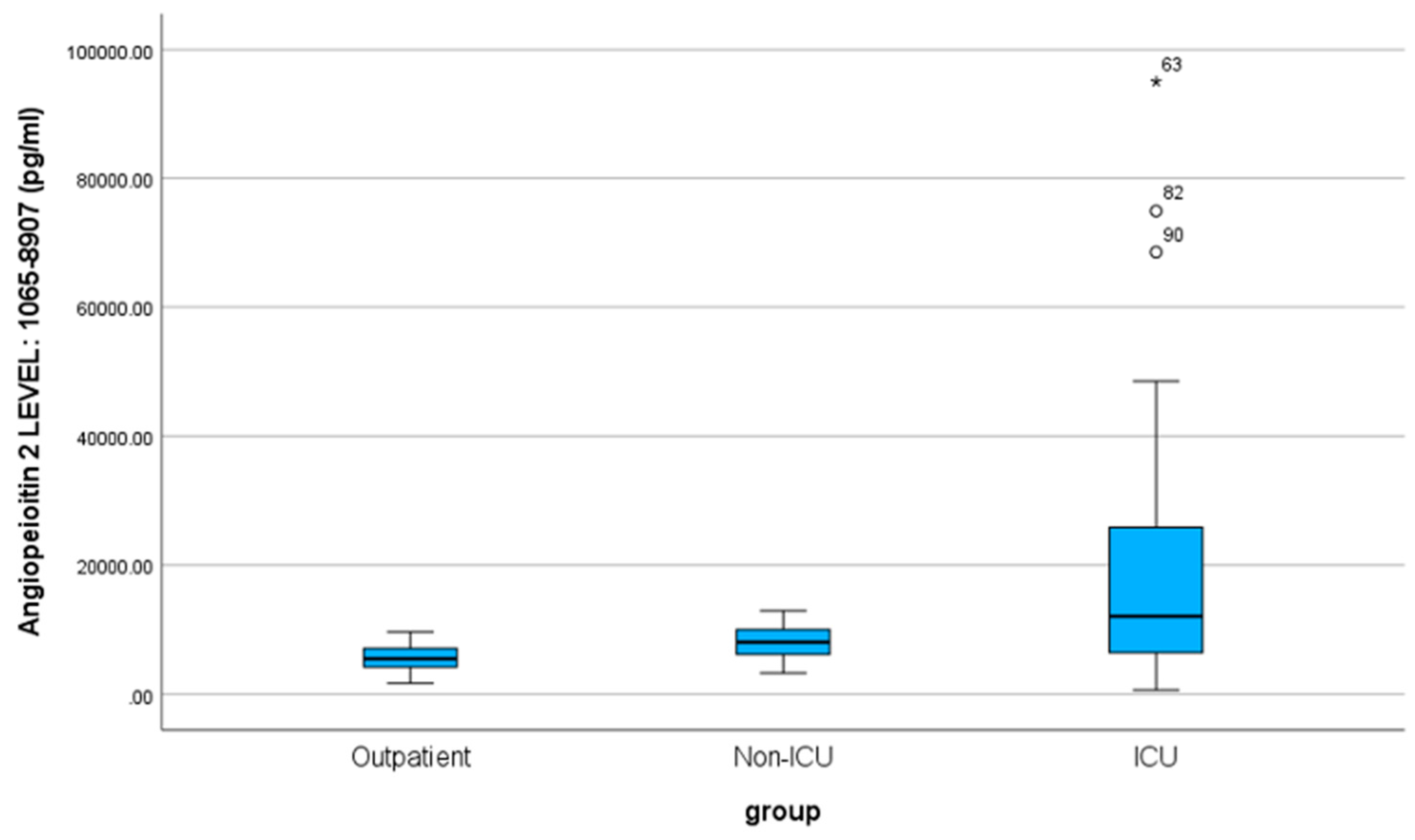

2.2. Results of Ang-2

Also, according to the normality test for the Ang-2 index, it does not follow a normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (sig. < 0.001). The mean value of the angiopoietin-2 index is 11955.74, with a standard deviation of 15647.54 (SD). Correspondingly, for the three specific patient groups, the values are as follows: outpatient 5611.00 pg/ml (SD 1933.16), non-ICU 8103.63 pg/ml (SD 2346.85), and ICU 22152.60 pg/ml (SD 24033.78). Additionally, the medians for outpatient, non-ICU, and ICU patients are 5475 pg/ml, 8057.5 pg/ml, and 12038.5 pg/ml, respectively. According to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney-U test, there is a statistically significant difference between the outpatient-non-ICU and outpatient-ICU (Sig. < 0.001) and (Sig. < 0.001) groups. In contrast, the mean values between the non-ICU-ICU groups do not differ significantly (Sig. = 0.060) regarding the angiopoietin-2 index.

Figure 3.

Histogram of Frequencies for Angiopeioitin-2.

Figure 3.

Histogram of Frequencies for Angiopeioitin-2.

Figure 4.

Box Plot of Angiopoietin-2 for the three groups of patients.

Figure 4.

Box Plot of Angiopoietin-2 for the three groups of patients.

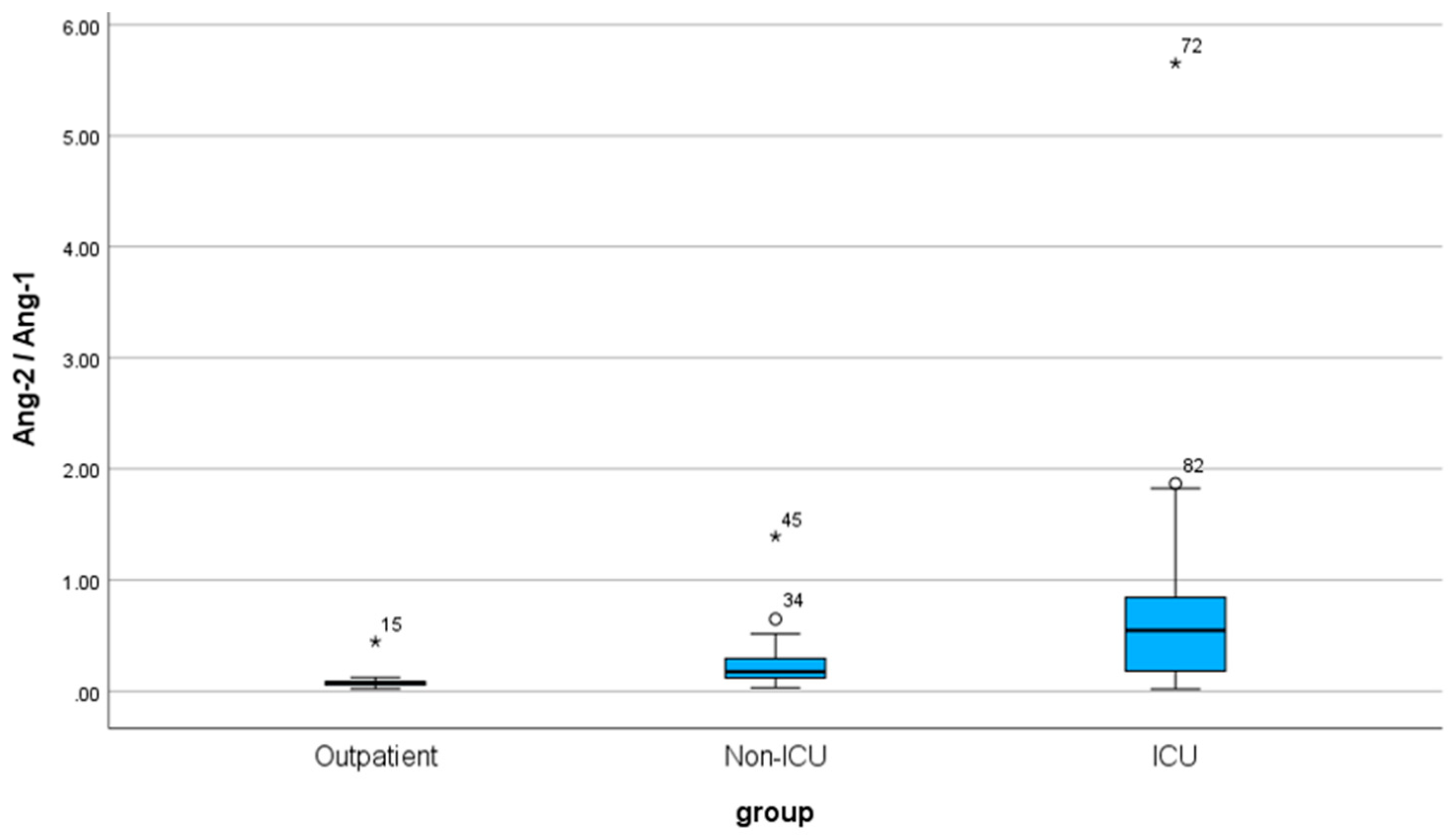

2.3. Results of Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio

Regarding the ratio, the Ang-2/Ang-1 variable does not follow a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Sig. ≤ 0.001). The mean value of the Ang-2 / Ang-1 index is 0.3697, with a standard deviation of 0.7877 (SD). Correspondingly, for the three specific patient groups, the values are as follows: outpatient 0.0862 (SD 0.0727), non-ICU 0.2534 (SD 0.2567), and ICU 0.7694 (SD 1.0573). The outpatient, non-ICU, and ICU medians are also 0.0767, 0.1790, and 0.5455, respectively.

According to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test, there is a statistically significant difference among the individual patient groups for the Ang-2 / Ang-1 index: outpatient - ICU (Sig. < 0.001), outpatient - non-ICU (Sig. < 0.001), and non-ICU - ICU (Sig. = 0.002).

Figure 5.

Histogram of Frequencies for index Ang-2 / Ang-1.

Figure 5.

Histogram of Frequencies for index Ang-2 / Ang-1.

Figure 6.

Box Plot of Ang-2/ Ang-1 for the three groups of patients.

Figure 6.

Box Plot of Ang-2/ Ang-1 for the three groups of patients.

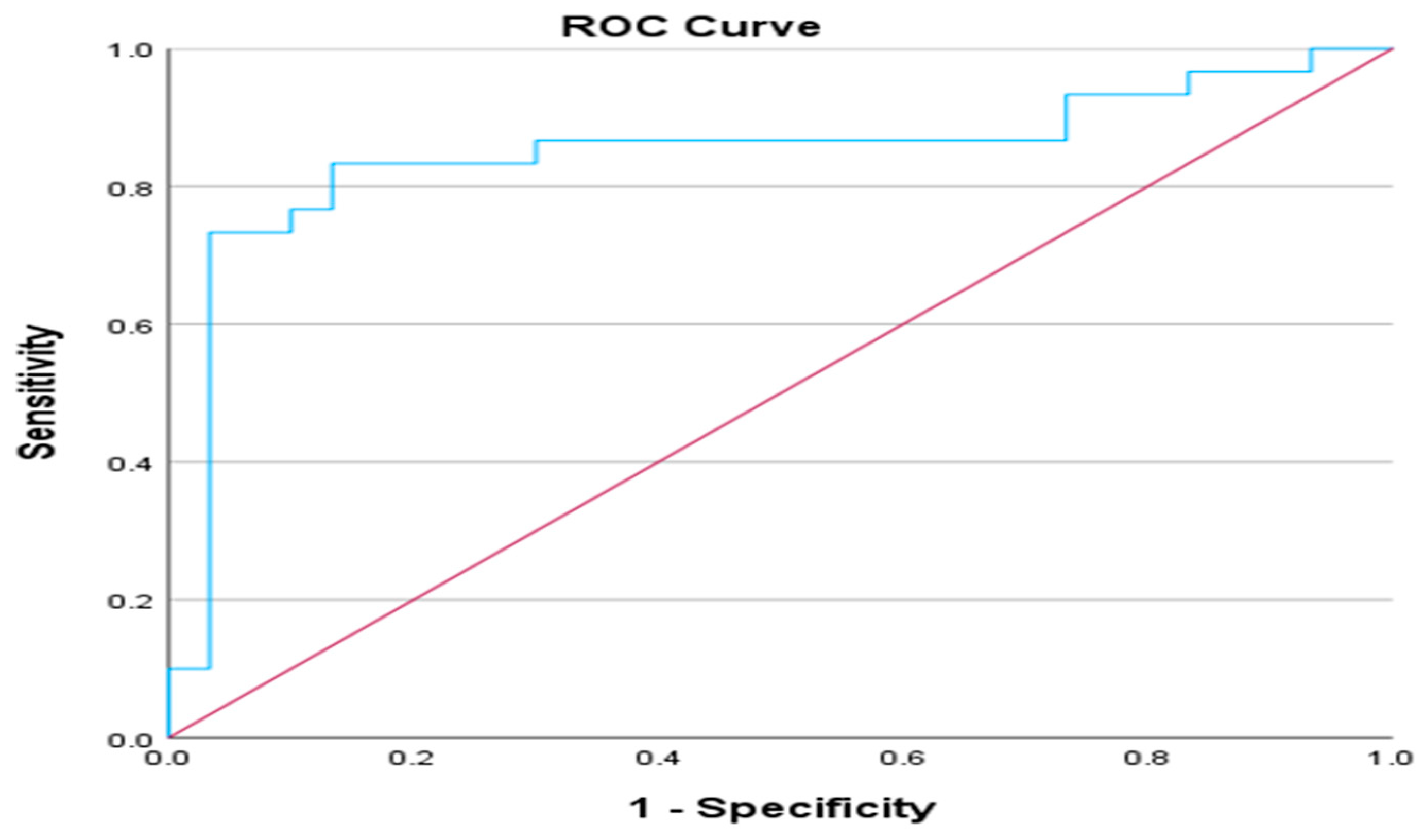

2.4. Results of ROC analysis and Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio

Exploring the categories of outpatient and non-ICU patients, we conducted a ROC analysis utilizing the Ang-2/Ang-1 index to ascertain the optimal threshold for distinguishing between these groups. The area under the curve (AUC) attained the value of 0.849 (p < 0.001), meaning that the model is effective in classification tasks. The asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval ranges from 0.738 to 0.959, further underscoring the robustness of these findings. Youden's Index is a commonly used statistic that aims to find a threshold that maximizes the difference between sensitivity and (1-specificity). It is calculated for each threshold by adding sensitivity and specificity and subtracting 1. The threshold corresponding to the highest Youden's Index is a potential cut-off point. Based on the extracted results, the optimal cut-off point based on Youden's Index would be 0.1122 or 0.1271. Youden's index is a commonly used statistic that aims to find a threshold that maximizes the difference between sensitivity and (1 - specificity).

Figure 7.

ROC analysis of Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of outpatient and non-ICU patients.

Figure 7.

ROC analysis of Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of outpatient and non-ICU patients.

Table 1.

Area Under the Curve f Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of outpatient and non-ICU patients. Test Result Variable(s): ratio Ang-2/Ang-1

Table 1.

Area Under the Curve f Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of outpatient and non-ICU patients. Test Result Variable(s): ratio Ang-2/Ang-1

| Area |

Std. Errora

|

Asymptotic Sig.b

|

Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| .849 |

.056 |

.000 |

.738 |

.959 |

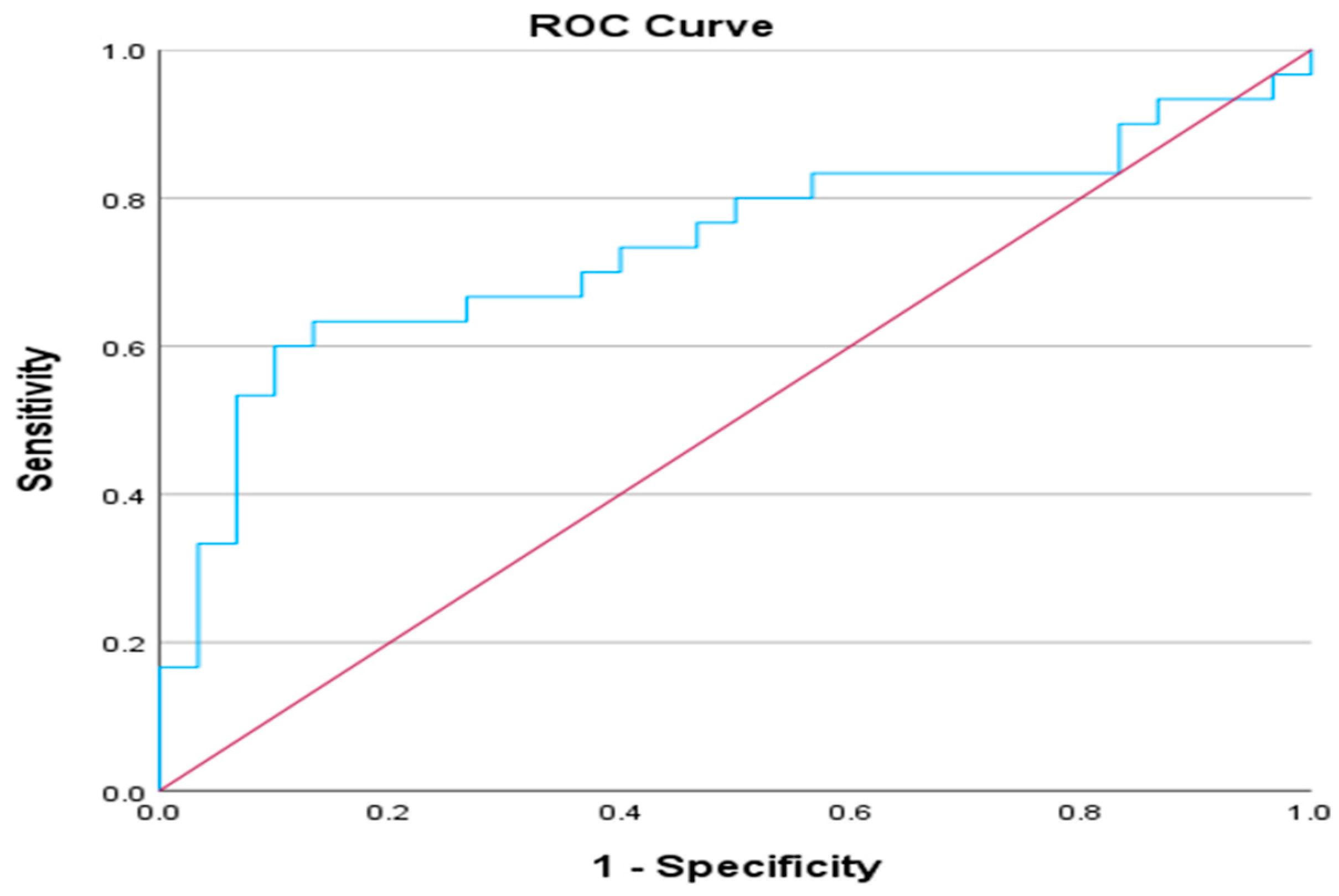

Furthermore, we conducted a ROC analysis based on the Ang-2 / Ang-1 index comparing non-ICU and ICU patients. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) attained a value of 0.734 (p = 0.002), meaning the model is acceptably effective in classification tasks. The asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval ranges from 0.602 to 0.867. Youden's index is utilized to extract the potential cut-off point of 0.3825 or 0.4510.

Figure 8.

ROC analysis of Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of non-ICU – ICU patients.

Figure 8.

ROC analysis of Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio of non-ICU – ICU patients.

Table 2.

Area Under the Curve f Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio non-ICU – ICU patients. Test Result Variable(s): ratio Ang-2/Ang-1

Table 2.

Area Under the Curve f Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio non-ICU – ICU patients. Test Result Variable(s): ratio Ang-2/Ang-1

| Area |

Std. Errora

|

Asymptotic Sig.b

|

Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval |

| Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

| .734 |

.068 |

.002 |

.602 |

.867 |

3. Discussion

Different conditions such as diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and impaired angiogenesis contribute to microvascular dysfunction [

10], [

17]. It has been demonstrated that markers of endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis markers have been predictors of disease severity in heart failure, renal failure, and after cardiac surgery [

18], [

19] These biomarkers circulate in the blood and can cause and effect microvascular dysfunction.

To enhance early diagnosis and risk stratification, it is crucial to identify useful biomarkers. In our study, we analyzed the Angiopoietin-1 and Angiopoietin-2 indexes and Angiopoiten-2/Angiopoiten-1 ratio as indicators that will serve as a screening tool for severity in COVID-19 patients in delta and omicron waves. Regarding the angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 index, we showed significant differences between outpatient and hospitalized patients (non-ICU and ICU groups). In contrast, the non-ICU - ICU groups did not differ significantly. Also, for the Ang-2/Ang-1 index, there is a significant difference among the individual patient groups: outpatient - non-ICU, outpatient- ICU, and ICU- Non-ICU. Further, an ROC analysis using the Ang-2/Ang-1 index was conducted to ascertain the optimal threshold for distinguishing between groups. Between outpatient and non-ICU patient categories, the AUC was 0.849, indicating the model's effectiveness. The 95% Confidence Interval ranged from 0.738 to 0.959, indicating robustness. Youden's Index suggested the optimal cut-off point as 0.1122 or 0.1271. Furthermore, the ROC analysis showed an acceptable model for classification tasks between non-ICU and ICU groups, with an AUC of 0.734 and a potential cut-off point of 0.3825 or 0.4510. However, the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio in our research is regarded as an important biomarker for rapid risk stratification and prognosis. The ratio of Ang-2 to Ang-1 demonstrated greater prognostic and diagnostic utility, surpassing the levels of Ang-1 and Ang-2 indexes. Moreover, this ratio demonstrated notable diagnostic and prognostic efficacy in predicting severity.

In addition to supporting the value of decreasing levels of angiopoietin-1 as an indicator for hospitalization, particularly when comparing patients requiring hospital care to those who can be managed as outpatients, our research reinforces prior findings. Researchers in two separate studies, Abou-Arab et al. and Vassilliou et al., have provided additional insights that there is no difference in Ang-1 levels between severe and critical COVID-19 patients and survivors and non-survivors. In our study, there is no difference between hospitalized patients (non-ICU – ICU patients) [

20], [

21] We also assessed the endothelial damage resulting from increased levels of Ang-2. This discovery reinforces the theory that COVID-19 is a vascular condition marked by injury to the endothelium, angiogenesis, and thrombosis.

According to Six et al. and Alay et al., circulating levels of angiopoietin-2 as a marker of endothelial injury were higher in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 than in healthy controls [

8], [

22]. Also, Smadja et al. study indicated that angiopoietin-2 is a relevant predictive factor for ICU direct admission in COVID-19 patients [

23]. Henry et al. as well found that increased Ang-2 expression is related to endothelial activation and an increased risk of ICU admission in patients admitted with COVID-19 [

24], [

25]. Also, three other studies have reported the significant role of Ang-2. In the first study, Abou-Arab et al. found that Ang2 was significantly higher in the critical group [

20]. In the second study, Vill et al. showed that there is a strong correlation between angiopoietin-2 course and mortality in hospitals and a non-resolving pulmonary condition associated with COVID-19 [

26]. In the third study, Kümpers et al. highlight the independent prognostic impact of circulating Ang-2 in critical illness [

27].

In another study by Vassilliou et al., patients who were directly admitted to the ICU rather than the ward had elevated levels of Ang-2[

21]. In our research, angiopoietin-2 is a valuable indicator for the hospitalization of patients in comparison to the outpatient and hospitalized group and not only in critical care patients. The discrepancies between our observations and the aforementioned studies and others may be due to the emergence of new virus variants, and the availability of new therapies and vaccines may lead to different outcomes.

In the research of Ong et al., the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio may be a prognostic biomarker of endothelial activation in patients with acute lung injury and may also be useful for risk stratification in these patients [

28]. Also, in the Gouzi et al. survey, the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio is a potential marker of vascular impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients [

29]. Moreover, according to the findings of Fang et al, angiopoietin-2/angiopoietin-1 and ratios could have a prognostic value for early sepsis in an emergency department [

30].

In the study of Lázaro et al., the Ang2/Ang1 ratio was shown to be a predictor of severity among critically ill patients [

31]. According to our research, the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio is a potent severity indicator considerably higher in the critical group of COVID-19 patients, consistent with the findings of Abou-Arab et al. research.

Monitoring the ratio of Ang-2 to Ang-1 in COVID-19 patients could aid in identifying those at a higher risk for critical outcomes and engaging treatment decisions. Modifications in the levels of Ang-1 and Ang-2 and Ang2/Ang1 ratio may additionally indicate the efficacy of treatment and serve as plausible therapeutic objectives for multi-targeted therapies.

Our study agrees with Seol et al. results for sepsis.[

32] The levels of Ang-1 and Ang-2 concentrations exhibit a correlation with disease severity and survival, as indicated by their predictive values. The potential ability of Ang-1 and Ang-2 concentrations to differentiate is clinically important and should be further explored prior to implementation in routine practice.

The limitations of our study include the fact that (1) the patient selection process was conducted in a random manner without considering specific variables that may have influenced the indices, such as diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc. (2) Additionally, cases pertaining to the α wave were not incorporated into the study. (3) As an agonist or antagonist of the Tie-2 receptor, Ang-2 has also been shown to be context-dependent, and its role may depend on other growth factors, such as VEGF-A. We did not measure VEGF-A and Tie-2 receptors in our cohort, so we are unable to corroborate their role in relation to angiopoietins. (4) Finally, the small cohort size conducted in a singular center prevents us from extracting broad conclusions from our data. In addition, lacking information included anthropometric data for patients. To confirm and extend these findings, we propose that the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio be validated as a prognostic factor in a larger cohort of patients. Future research should investigate the relationship between Ang-2/Ang-1 and other endothelial permeability markers to improve severity and stratification prediction.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study design and patient characteristics

This single-center, cross-sectional, observational, study included 90 COVID-19 adult patients (>18 years) and was conducted at AHEPA University Hospital from 20 July 2021 to 30 December 2022. The study included 90 patients that fulfilled the criteria for hospitalization (30 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in intensive care units, 30 patients with COVID-19 disease hospitalized in ward units) and 30 asymptomatic patients, non-hospitalized individuals with COVID-19 disease, who were used as controls for biomarker measurements.

Between groups patient characteristics, such as age and sex, were not significantly different. The diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) in nasopharyngeal swab samples. The study was approved by the AHEPA Hospital Research Ethics Committee (129/19-03-2020, and the bioethics approval committee of Aristotle University. All procedures carried out on patients complied with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients prior to any study procedure.

In the study enrollment information, the patient's age, sex, symptoms, medical history, and laboratory findings were reported. Patients younger than 18 years old, with a history of cancer, a diagnosis of hematological disease or thrombophilia, liver disease or renal failure, or a critical illness related to another diagnosis other than COVID-19, are not included in the study.

4.2. Blood-Sampling Procedures

Venous blood was collected with the first scheduled morning draw within 72 hours post-ward and ICU admission. Based on the test, blood samples were drawn into plastic vacutainer tubes with 0.129 M (3.8%) trisodium citrate (catalog number 363095; Becton Dickinson) for plasma samples in a 9:1 ratio of blood to anticoagulant. Test samples were centrifuged twice at 2500 g for 15 min at 18–25 °C to obtain poor platelet plasma. Venus blood samples are also collected in vacutainer tubes coated with silicon and micronized silica particles to accelerate clotting for procedures that require serum samples (catalog number 367837; Becton-Dickinson).

Serum, was collected, portioned into 0.5 mL aliquots, and stored at 80°C until used. All samples remained frozen until used. A freeze-thaw cycle was avoided.

4.3. Laboratory procedures

The routine clotting assays, including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen, and D-Dimers were performed in ACL TOP 50 series (Instrumentation Laboratory; Bedford, MA, USA), with manufacturer reagents and controls per laboratory protocol.

Endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis laboratory markers, angiopoietins 1 and 2 (Ang-1 and Ang-2, respectively) were measured in serum by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). A 50-fold dilution is suggested for Ang-1 serum samples. All samples were assayed in duplicate. Biomarkers are presented with their standard reference range and a ratio.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables or median with an interquartile range (Q1–Q3) for skewed data. For the quantitative indices of the study, mean values and standard deviations are estimated for the entire sample and the individual groups of patients (outpatient, non-ICU, and ICU). Additionally, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality is performed. Plasma Ang-1, Ang-2, and Ang-2 / Ang-1 levels were not normally distributed, so data were compared using a non-parametric test (Mann-Whitney rank sum). The statistical analysis of the data was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.

5. Conclusions

We have identified circulating vascular markers that can be used to monitor disease severity in COVID-19 patients in delta and omicron waves. Monitoring the Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio could aid in identifying COVID-19 patients at higher risk for critical outcomes. Moreover, these markers will assist clinicians in tailoring treatment strategies for improved outcomes. All hospitalized COVID-19 patients exhibited an increase in angiogenesis markers, which might suggest the presence of hypoxemia and inflammation. Endothelial cell integrity provides an antithrombotic environment, and the findings of pulmonary angiopathy in patients with severe COVID-19 highlight the involvement of endotheliopathy in pulmonary perfusion defects, coagulopathy, and thrombosis.

As vaccine-resistant variants are likely to emerge in the future, studies must use biomarkers that correlate with severity. In addition, the findings of our investigation support the hypothesis that COVID-19 induces microvascular dysfunction by activating the endothelium. Moreover, not only in COVID-19 but in various other diseases such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, endothelial dysfunction is a crucial factor. This dysfunction has a substantial role in disease progression, especially in vascular issues and thrombosis. Therefore, a better understanding of the role of endothelium can provide new possibilities for exploration and innovative treatments for the management of thromboembolisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.; Investigation, P.T.; K.K.; T.V.; A.L.; E.P.; M.P.; LL.S. Resources, P.T.; Writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; Writing—review and editing, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was not funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the AHEPA Hospital Research Ethics Committee (129/19-03-2020), and the bioethics approval committee of Aristotle University. All procedures carried out on patients complied with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients prior to any study procedure.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to intellectual property concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the stuff of laboratory Hematology, Microbiology Department

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- T. Mokhtari, F. T. Mokhtari, F. Hassani, N. Ghaffari, B. Ebrahimi, A. Yarahmadi, and G. Hassanzadeh, “COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms,” Journal of Molecular Histology 2020 51:6, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 613–628, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. wen Xu, I. S. wen Xu, I. Ilyas, and J. ping Weng, “Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: an overview of evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms and potential therapies,” Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022 44:4, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 695–709, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohan and N. Vinod, “COVID-19: An Insight into SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic Originated at Wuhan City in Hubei Province of China,” Journal of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, vol. 6, no. 4, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Akkız, “The Biological Functions and Clinical Significance of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Corcern.,” Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 9, p. 849217, 22. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, F. Ferrara, A. M. Auti, M. Di Domenico, and M. Boccellino, “Advances in the Omicron variant development,” J Intern Med, vol. 292, no. 1, pp. 81–90, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Antonelli, J. C. M. Antonelli, J. C. Pujol, T. D. Spector, S. Ourselin, and C. J. Steves, “Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2,” The Lancet, vol. 399, no. 10343, pp. 2263–2264, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Liossi, E. S. Liossi, E. Tsiambas, S. Maipas, E. Papageorgiou, A. Lazaris, and N. Kavantzas, “Mathematical modeling for Delta and Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics in Greece,” Infect Dis Model, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 794–805, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- et al. , “The Endothelium and COVID-19: An Increasingly Clear Link Brief Title: Endotheliopathy in COVID-19,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 11, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Yau, H. W. Yau, H. Teoh, and S. Verma, “Endothelial cell control of thrombosis,” BMC Cardiovasc Disord, vol. 15, no. 1, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Krishna Kolluru, S. C. G. Krishna Kolluru, S. C. Bir, C. G. Kevil, and J. W. Calvert, “Endothelial Dysfunction and Diabetes: Effects on Angiogenesis, Vascular Remodeling, and Wound Healing,” Int J Vasc Med, vol. 2012, p. 30, 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Thurston and C. Daly, “The Complex Role of Angiopoietin-2 in the Angiopoietin–Tie Signaling Pathway,” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, vol. 2, no. 9, 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Angiopoietins: Possible biomarkers in severe pneumonia? | European Respiratory Society.” Accessed: Oct. 01, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://erj.ersjournals.

- R. G. Akwii, S. R. G. Akwii, S. Sajib, F. T. Zahra, and C. M. Mikelis, “Role of Angiopoietin-2 in Vascular Physiology and Pathophysiology,” Cells, vol. 8, no. 5, 19. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- C. Volleman et al., “Endothelial Permeability and the Angiopoietin/Tie2 System Following Mild and Severe COVID-19,” Artery Res, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 83–93, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fang, C. Y. Fang, C. Li, R. Shao, H. Yu, Q. Zhang, and L. Zhao, “Prognostic significance of the angiopoietin-2/angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-1/Tie-2 ratios for early sepsis in an emergency department,” Crit Care, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. Flaumenhaft, K. R. Flaumenhaft, K. Enjyoji, and A. A. Schmaier, “Review Series Vasculopathy in COVID-19”. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Lázaro et al., “Predictors of mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 and diabetes,” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, vol. 56, p. e12728, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. F. M. J. Baaten, S. C. F. M. J. Baaten, S. Vondenhoff, and H. Noels, “Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Increased Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease,” Circ Res, vol. 132, no. 8, p. 970, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- et al. , “New mechanisms involved in the development of cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease,” Nefrología (English Edition), vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 63–80, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- et al. , “Association between inflammation, angiopoietins, and disease severity in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a prospective study,” Br J Anaesth, vol. 126, no. 3, pp. e127–e130, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Vassiliou, C. S. G. Vassiliou, C. S. Vrettou, C. Keskinidou, I. Dimopoulou, A. Kotanidou, and S. E. Orfanos, “Endotheliopathy in Acute COVID-19 and Long COVID,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, Vol. 24, Page 8237, vol. 24, no. 9, p. 8237, 23. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- H. Alay and E. Laloglu, “The role of angiopoietin-2 and surfactant protein-D levels in SARS-CoV-2-related lung injury: A prospective, observational, cohort study,” J Med Virol, vol. 93, no. 10, pp. 6008–6015, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Smadja et al., “Angiopoietin-2 as a marker of endothelial activation is a good predictor factor for intensive care unit admission of COVID-19 patients,” Angiogenesis, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 611–620, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Pine et al., “Circulating markers of angiogenesis and endotheliopathy in COVID-19,” Pulm Circ, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 1–4, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Henry et al., “Circulating level of Angiopoietin-2 is associated with acute kidney injury in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19),” Angiogenesis, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 403, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Villa et al., “Dynamic angiopoietin-2 assessment predicts survival and chronic course in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” Blood Adv, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 662, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Kümpers et al., “Excess circulating angiopoietin-2 is a strong predictor of mortality in critically ill medical patients,” Crit Care, vol. 12, no. 6, p. R147, Nov. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Ong, D. E. T. Ong, D. E. McClintock, R. H. Kallet, L. B. Ware, M. A. Matthay, and K. D. Liu, “The Ratio of Angiopoietin-2 to Angiopoietin-1 as a Predictor of Mortality in Acute Lung Injury Patients,” Crit Care Med, vol. 38, no. 9, p. 1845, 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. Gouzi et al., “Plasma ratio of angiopoietin-2 to angiopoietin-1 is a biomarker of vascular impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients”. [CrossRef]

- Y. Fang, C. Y. Fang, C. Li, R. Shao, H. Yu, Q. Zhang, and L. Zhao, “Prognostic significance of the angiopoietin-2/angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-1/Tie-2 ratios for early sepsis in an emergency department,” Crit Care, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. P. Lázaro et al., “Predictors of mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 and diabetes,” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, vol. 56, p. e12728, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Seol et al., “The ratio of plasma angiopoietin-2 to angiopoietin-1 as a prognostic biomarker in patients with sepsis,” Cytokine, vol. 129, p. 155029, 20. 20 May. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).