1. Introduction

The term cerebral palsy (CP) refers to a non-progressive disorder of posture and movement due to a non-progressive malformation or lesion in the brain [

1]. A distinction is made between ataxic, dyskinetic and spastic (unilateral or bilateral) forms of CP [

2]. Children with CP suffer from a variety of comorbidities in addition to motor symptoms such as epilepsy, intellectual impairment, behavioral, musculoskeletal, and nutritional issues, sleeping problems, and pain [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. A wide variety of therapeutic approaches and drug treatments for the individual symptom complexes of patients with CP have been described [

9]. Medications are often prescribed to address the treatment of epilepsy as well as movement disorders [

5,

10,

11,

12]. In addition to conventional medications, cannabinoids are increasingly used for various indications in children. Cannabis (Cannabis sativa) is a plant-based drug composed of over 100 phytocannabinoids. Among them, the psychoactive substance Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are of particular interest.

CBD has an anti-inflammatory, anti-epileptic and anxiety-alleviating effect [

13] and is used in children primarily to treat epileptic seizures, anxiety disorders and psychoses [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Its use has been well studied for epilepsy. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studied the effect of CBD in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome and showed a greater reduction in seizures frequency compared to placebo with good tolerance [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. A case series in children from the UK Medical Cannabis Registry suggests that treatment with cannabinoids (CBD oils and a combination of CBD and THC may have a beneficial effect on seizure frequency [

20].

THC is used in children and adults for different indications [

14,

21,

22]. In adults, it is mainly used for the treatment of chronic pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis [

21]. There is moderate evidence that THC reduces spasticity in adults with multiple sclerosis [

22,

23], but the evidence for the treatment in other indications for adults is weak [

22]. In children and adolescents, the use of THC has been described in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder and Tourette's syndrome [

14], to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [

24] and to treat spasticity in the context of pediatric palliative care [

25]. So far, apart possibly from Tourette’s syndrome [

26], there is little evidence in these indications on effectiveness in children [

27]. In January 2019, a systematic literature review summarized the literature on the use of cannabinoids for spasticity with a special focus on children [

28]. A conclusion regarding the effect of cannabinoids on childhood spasticity could not be drawn. Shortly afterwards (March 2019), an RCT on the effect of Nabiximols (Sativex®) in 72 children with spasticity (mostly with spastic CP) was published. It showed no significant improvement in spasticity 12 weeks after treatment compared to placebo [

29].

Despite the limited evidence for cannabinoids in children (with exception of CBD in Lennox-Gastaut and Dravet syndrome) [

30], cannabinoids seem to be used in Switzerland and other countries in a wide range of indications for children with CP. Information on prescription practices is mostly based on anecdotal reports and case descriptions. A recent Swiss parent survey showed that THC and CBD are mainly used in children with neurological disorders [

31]. It remains unclear in which context and for what indications cannabinoids are prescribed to children with CP and what experience specialists have had in treating children with CP with cannabinoids.

Therefore, we sent a questionnaire to medical experts in Europe, North America, and Australia with the aim to determine for which indications cannabinoids were prescribed, what effects and side effects were observed, and how the prescribing physicians acquired their knowledge about treatment with cannabinoids.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design and data collection

This prospective observational study collected data from physicians who treat children (<18 years) affected by CP. A questionnaire in English was developed and reviewed by the steering board members of the Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry. The revised questionnaire (Supplementary Table S.1) was used for data collection through an online survey on the SurveyMonkey® platform (San Mateo, California, USA;

www.surveymonkey.com). Access to the questionnaire was given by e-mail. The targeted participants were physicians in Europe, North America, and Australia with expertise in the care of children with CP. The initial address list (n= 102) was developed by the Steering Board of the Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry in collaboration with the Swiss Academy of Childhood Disability and was a convenience sample of personal contacts. Using chain-sampling referral, addressees were invited to forward the survey to relevant colleagues (n unknown). Data collection took place from October 2019 to February 2020.

The questionnaire was composed of three sections: (I) four questions to assess if the participants fulfil the inclusion criteria; (II) demographic data such as sex, age, country of residence, medical specialization, work experience, and workplace of the participants; (III) prescription practices of cannabinoids in children with CP, including participants years of experience on the subject, indications and formulas used, observed efficacy and short-/long-term adverse effects.

Inclusion criteria and definition of groups

Participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria and obtained access to the complete questionnaire, if they answered positively to one or more of the questions of section (I):

Have you already worked with patients treated with cannabinoid drugs?

Were any of them of pediatric age (0-18y)?

Were any of these children/adolescents diagnosed with cerebral palsy?

Did you ever experience a situation in which the prescription of cannabinoids in this type of patient was debated, but for some reason not prescribed?

Physicians who answered negatively to all four questions or who did not complete the questionnaire were excluded from the study. Participants affirming all four questions of section (I) were defined as experienced in the treatment of children with CP using cannabinoids, while participants affirming one to three questions were defined as unexperienced.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize participants by experience of cannabinoids in children with CP (yes vs. no) and by region and assessed differences between groups using chi-square, Fisher's exact, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All analyses were done in Stata (version 15.1, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical statement

For this study, no approval by an institutional review board was required within the context of Swiss law.

3. Results

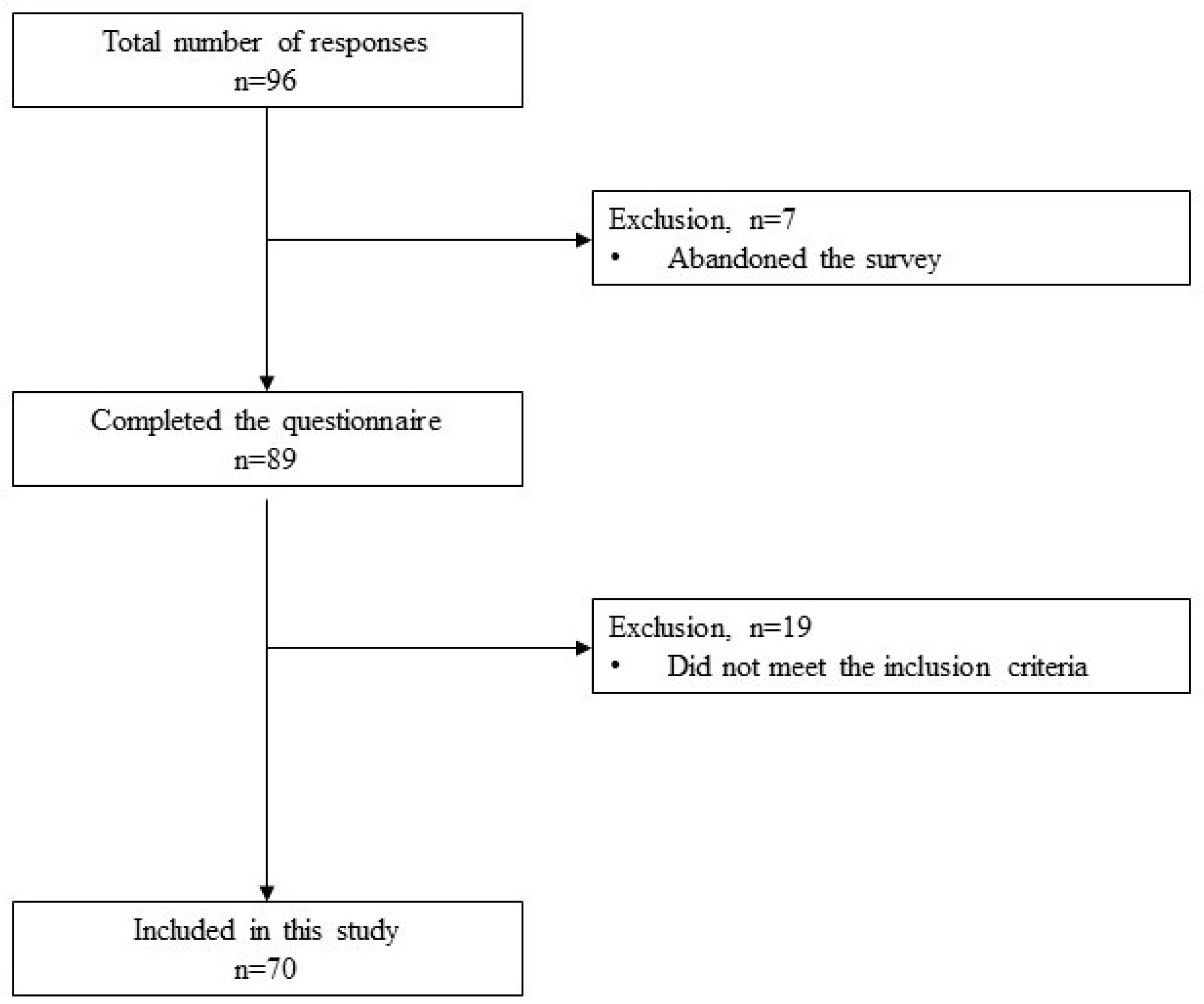

The total number of physicians responding to the survey was 96. We excluded 7 physicians for not completing the survey and 19 physicians for not meeting at least one of the four inclusion criteria. Hence, 70 participants were included in the study (

Scheme 1). Of these, 23 (33%) belonged to the unexperienced group and 47 (67%) were experienced in the prescription of cannabinoids to children with CP.

3.1. Study participants

The median age of participants was 48 years (interquartile range 42-57), and 43 (61%) were female (

Table 1). Most were pediatricians (45, 64%), followed by rehabilitation medicine physicians (28, 40%), neurologists (10, 14%), and an anesthetist (1, 1%). Only 12 (17%) participants had less than 5 years’ work experience in their specialization. The work experience in the treatment of children and adolescents with CP was similar between groups (experienced vs. unexperienced, p=0.8). Participants with experience were more likely to work in any hospital (university and/or general hospital) than unexperienced participants (42, 89% vs. 14, 61%; p=0.01). Most participants indicated that they gained their knowledge of cannabinoid treatment primarily through individual learning (45, 64%), followed by colleagues (28, 40%), conferences (17, 24%), and as part of their continuing education (15, 21%). 10 (14%) indicated that they had been informed by patients and families about cannabinoid therapy options.

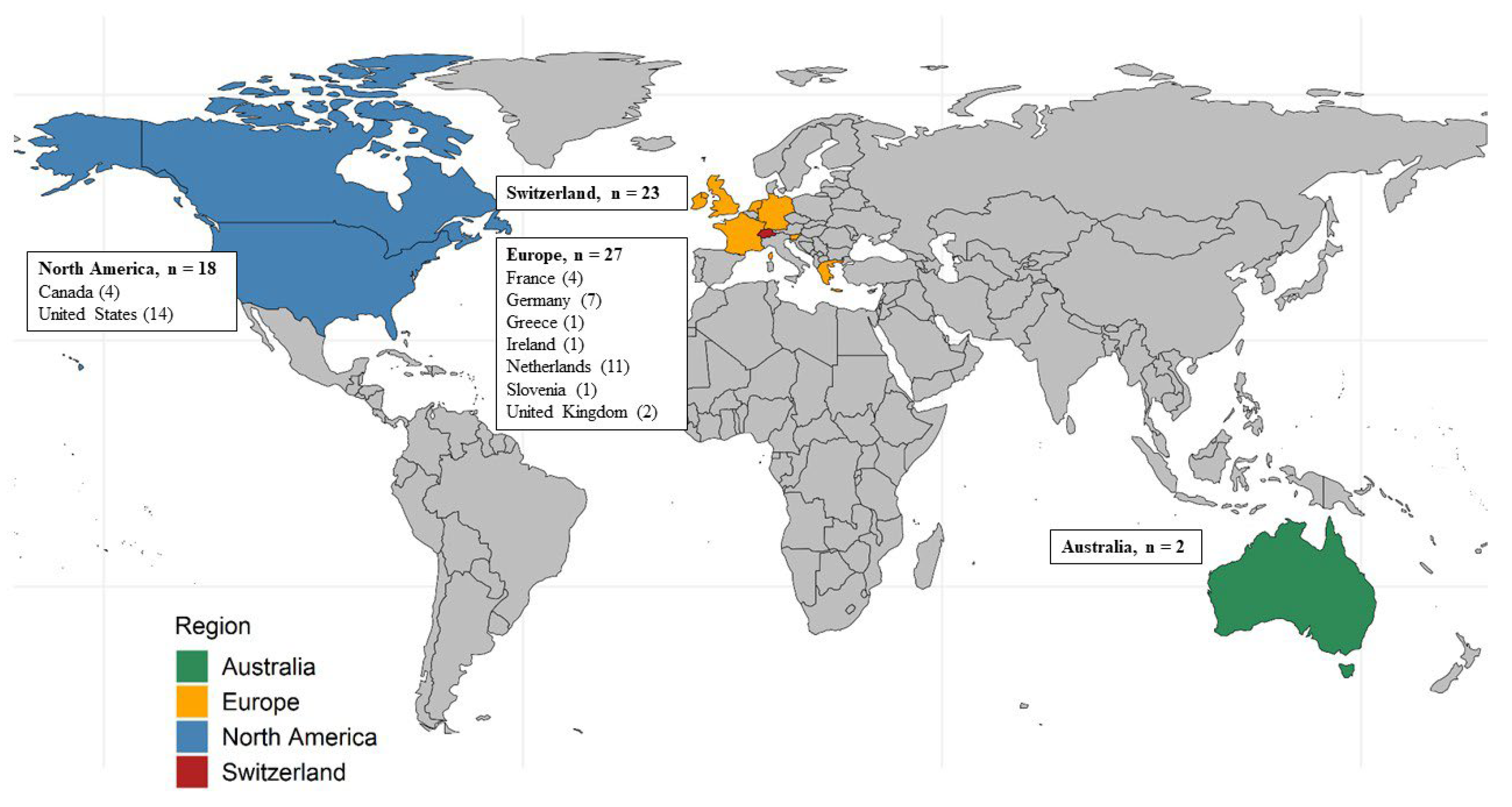

Most participants came from Europe, followed by Switzerland, North America, and Australia (

Figure 1). Characteristics of the participating physicians by region are provided in supplementary Table S.1.

3.1. Indications

The most frequent indication for the treatment with cannabinoid medication in children with CP was epilepsy (48, 69%), followed by spasticity (45, 64%), pain (44, 63%), behavioral problems (12, 17%), sleeping disturbance (11, 16%), and dystonia (8, 11%;

Table 2). Experienced participants were more likely to indicate cannabinoids for epilepsy, spasticity, and a tendency towards pain compared to the unexperienced ones. Cannabinoids were most frequently prescribed as a co-medication (28, 40.0%) and as a second line treatment (16, 23%). The most common reasons not to initiate cannabinoids in children with CP were lack of cost coverage (24, 34%), age of the patient (19, 27%), lack of evidence on effectiveness and side effects (15, 21%), and parents wish (13,19%).

3.1. Perceived effect of the treatment and side effects

The perceived effect of the treatment with cannabinoids was reported to be strong or moderate by 32 (68%), weak in 10 (21%), and insignificant by 1 (2%) of the experienced participants (

Table 4). Twenty-nine (41%) participants reported short-term side effects and more experienced participants than unexperienced ones reported side-effects (25, 53% vs. 4, 17%, p=0.004). The most frequently reported side effects among the experienced participants were drowsiness (12, 26%), somnolence (9, 19%), fatigue (6, 13%), and diarrhea (6, 13%). Less frequently reported side effects are listed in

Table 4. No long-term side effects were described.

4. Discussion

This international online survey assessed the prescription practices of cannabinoids in children with CP by their treating physicians. The participating physicians (n=70) mainly acquired their knowledge on cannabinoids outside of medical training. The physicians frequently prescribed differing formulas of cannabinoids for various indications in children with CP. The most common indications were epilepsy, spasticity and pain, and treatment was initiated as co-medication or second line. Overall, a moderate efficacy of cannabinoids and no long-term side effects were reported.

Participants from a range of countries took part in the survey. Most participants who prescribed cannabinoids for children with CP worked in clinics, especially in university hospitals, while participants without experience in prescribing these drugs often worked in rehabilitation centers. Participants indicate that they acquired their knowledge on the topic primarily through individual learning. This highlights the need to promote knowledge transfer and education on the topic.

In our study, epilepsy was among the three most frequently reported indications for cannabinoids in children with CP. These prescriptions are probably based on the benefit of the treatment with cannabinoids of specific forms of epilepsy in children [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, the verification is based on the use of CBD compounds in children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome. Physicians seem to use cannabinoids to treat epilepsy in young CP patients with associated epilepsy based on these findings. We cannot assess which forms of epilepsy were treated using cannabinoids and whether they were used as the sole substance or as an add-on therapy. Also, it remains unclear whether cannabinoids were used for the treatment of epilepsy or other symptoms.

Spasticity was also among the most often reported indications for cannabinoids in our survey. Cannabinoids are used to treat spasticity in adult CP patients [

21,

22,

23,

32], and the treatment of young patients is an ongoing debate [

33]. The high prescription rate of cannabinoids for spasticity in children with CP in our study could derive from the evidence in adults. However, a recent RCT showed no benefit of cannabinoids in the treatment of spasticity in children with CP [

29]. We conducted our survey before the publication of this RCT. This recent finding might reduce the prescription rate of cannabinoids to treat spasticity in children with CP in the future.

The third of the most common indications of cannabinoids in children with CP was pain. This finding was to be expected, since cannabinoids are used to treat chronic pain of various etiologies [

34,

35], and chronic pain is a common problem in children with CP, especially in more severe forms [

36]. However, the efficacy of cannabinoids to relieve neuropathic pain in children is not supported [

14]. Studies on the use of cannabinoids to specifically treat pain in children with CP do not exist yet. An interesting aspect of the survey was the responses regarding dystonia. Several colleagues independently indicated dystonia as their most important indication in the personal comments. To date, there is little information regarding the use of cannabinoids in dystonia. Individual case reports from the adult literature describe positive effects [

37]. A pilot study in children with complex movement disorders described improvements in dystonia with the use of cannabinoids [

38,

39].

Our study revealed that a variety of cannabis preparations with widely varying THC and CBD content are used in children with CP. The recurrent use of cannabidiol compounds is probably due to many colleagues primarily treating patients with epilepsy. Unfortunately, we cannot determine from our survey which substance was used for which indication. In the multiple-choice question addressing the prescribed preparations, we only listed the preparations that are best known to us and most frequently used in Switzerland. However, many colleagues stated that they used other preparations. The reasons for the choice of preparations were not asked. We also do not know which preparations are predominantly available in which countries and the legal background of their purchase. The pharmacologically manufactured Nabiximols (Sativex®), which can be purchased as standard in many countries, was rarely used.

The perceived effect of cannabinoids was reported to be moderate by most experienced physicians. However, the survey does not allow conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness of cannabinoids for various indications. Half of the experienced physicians described short-term side effects, drowsiness and somnolence were most common. No long-term adverse effects were perceived. Nonetheless the survey was not designed to cover the safety spectrum of medicinal cannabinoids. Such a survey is not capable of doing this, nor do we wish to make a definitive statement about safety. Still, our findings on side effects are in line with previous research [

40,

41]. To answer questions on efficacy and safety of cannabinoids in children with CP, interventional studies with a randomized controlled design or through single case study designs are mandatory.

This study has some limitations. The survey format provides insight into the topic and an impression of whether and how colleagues in western countries treat children with CP with cannabinoids. However, our observation is not representative. We cannot determine the response rate since we used several distribution paths. Statements about national preferences are not possible since we obtained a convenience sample mainly driven by personal contacts.

As it is not possible to track how many physicians received the survey and how many completed it, we could not assess the response rate. It is possible, for example, that colleagues who felt concerned by the topic completed the survey, biasing our findings. Also, the number of participants per region is too small to draw conclusions per region. Furthermore, it is not possible to check the quality of the data, since the survey was conducted anonymously. Accordingly, the results of our study should be interpreted with caution and no conclusions must be drawn regarding the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids in children with CP.

5. Conclusions

This survey shows that cannabinoids are prescribed for a wide range of indications in children with CP in western countries despite the lack of evidence for their use in this patient group. Accordingly, it is important that further clinical trials clarify for which indications and in which situations the use of cannabinoids is justified. Regarding epilepsy, it seems important to closely examine the use of cannabidiol specifically in CP patients. Further studies should also include indications, such as pain, behavioral problems, or dystonia. This will require multicenter RCTs, which could be based, for example, within national or international research platforms such as the Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Characteristic of the participating physicians by region; Table S2: Online survey questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Anne Tscherter and Sebastian Grunt; Data curation, Federico Morosoli and Kathrin Zuercher; Formal analysis, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli, Kathrin Zuercher and Sebastian Grunt; Investigation, Federico Morosoli, Anne Tscherter and Sebastian Grunt; Methodology, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli, Kathrin Zuercher, Anne Tscherter and Sebastian Grunt; Project administration, Anne Tscherter; Supervision, Anne Tscherter and Sebastian Grunt; Validation, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli and Kathrin Zuercher; Visualization, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli and Kathrin Zuercher; Writing – original draft, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli and Sebastian Grunt; Writing – review & editing, Sandra Hunziker, Federico Morosoli, Kathrin Zuercher, Anne Tscherter and Sebastian Grunt.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Nevertheless, we would like to thank the Swiss Foundation for Cerebral Palsy Children and the Anna Mueller Grocholski Foundation. Their support of the Swiss Cerebral Palsy registry laid the foundation for this survey. The funders of the Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry did not play a role in the conduct of this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as approval by an institutional review board was not required within the context of Swiss law.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to individual answers to the survey which could possibly be assigned due to the small sample.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all physicians who took the time to complete our survey and who shared it with colleagues. Without them, this work would not have been possible. We would also like to thank all the members of the Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry group for their contribution to the design of the survey and for their input, ideas, and comments on the topic. Swiss Cerebral Palsy Registry Group members (alphabetical): Joel Fluss, Pediatric Neurology Unit, Geneva Children's Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland, joel.fluss@hcuge.ch (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-6413-162X); Sebastian Grunt, Division of Neuropediatrics, Development and Rehabilitation, Children's University Hospital, Inselspital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, sebastian.grunt@insel.ch (Orcid ID: 0000-0003-2820-9650); Stephanie Juenemann, Division of Neuropediatrics and Developmental Medicine, University Children's Hospital of Basel (UKBB), University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, stephanie.juenemann@ukbb.ch; Claudia E. Kuehni, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, and Children's University Hospital, Inselspital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, claudia.kuehni@ispm.unibe.ch (Orcid ID: 0000-0001-8957-2002) ; Christoph Kuenzle, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St Gallen, Switzerland, christoph.kuenzle@kispisg.ch; Andreas Meyer-Heim, Swiss Children’s Rehab, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Affoltern a. A, Switzerland, andreas.meyer-heim@kispi.uzh.ch (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-6094-6717); Christopher J. Newman, Pediatric Neurology and Neurorehabilitation Unit, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland, christopher.newman@chuv.ch (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-9874-6681); Gian Paolo Ramelli, Neuropediatric Unit, Pediatric Institute of Southern Switzerland, Ospedale San Giovanni, Bellinzona, Switzerland, gianpaolo.ramelli@eoc.ch; Peter Weber, Division of Neuropediatrics and Developmental Medicine, University Children's Hospital of Basel (UKBB), University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland. peter.weber@ukbb.ch;

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy april 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in europe: A collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in europe (scpe). Dev Med Child Neurol 2000, 42, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, L.; Li, P.; Mok, E.; Oskoui, M.; Shevell, M.; Constantin, E. Behavioral difficulties, sleep problems, and nighttime pain in children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil 2019, 95, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwood, L.; Li, P.; Mok, E.; Shevell, M.; Constantin, E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of sleep problems in children with cerebral palsy: How do children with cerebral palsy differ from each other and from typically developing children? Sleep Health 2019, 5, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururaj, A.K.; Sztriha, L.; Bener, A.; Dawodu, A.; Eapen, V. Epilepsy in children with cerebral palsy. Seizure 2003, 12, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubouchi, Y.; Tanabe, A.; Saito, Y.; Noma, H.; Maegaki, Y. Long-term prognosis of epilepsy in patients with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019, 61, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhi, P.; Jagirdar, S.; Khandelwal, N.; Malhi, P. Epilepsy in children with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol 2003, 18, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluss, J.; Lidzba, K. Cognitive and academic profiles in children with cerebral palsy: A narrative review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2020, 63, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; McIntyre, S.; Morgan, C.; Campbell, L.; Dark, L.; Morton, N.; Stumbles, E.; Wilson, S.A.; Goldsmith, S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013, 55, 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.R.; Baker, L.B.; Reddihough, D.S.; Scheinberg, A.; Williams, K. Trihexyphenidyl for dystonia in cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 5, CD012430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M.J.; Rice, J.E. Intrathecal baclofen for treating spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015, CD004552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, B.J.; Wallen, M.A.; Imms, C.; Villanueva, E.; Rawicki, H.B.; Carey, L. Botulinum toxin a as an adjunct to treatment in the management of the upper limb in children with spastic cerebral palsy (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, CD003469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, M.M.; Queiroz, R.H.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A. Safety and side effects of cannabidiol, a cannabis sativa constituent. Curr Drug Saf 2011, 6, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.S.; Wilens, T.E. Medical cannabinoids in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S.; Cannabidiol in Dravet Syndrome Study Group. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Patel, A.D.; Cross, J.H.; Villanueva, V.; Wirrell, E.C.; Privitera, M.; Greenwood, S.M.; Roberts, C.; Checketts, D.; VanLandingham, K.E.; et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the lennox-gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.A.; Marsh, E.D.; French, J.A.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Benbadis, S.R.; Joshi, C.; Lyons, P.D.; Taylor, A.; Roberts, C.; Sommerville, K.; et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with lennox-gastaut syndrome (gwpcare4): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, A.; Cayam-Rand, D. Medical cannabis in children. Rambam Maimonides Med J 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Scheffer, I.E.; Sadleir, L.G. Efficacy of cannabinoids in paediatric epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019, 61, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erridge, S.; Holvey, C.; Coomber, R.; Hoare, J.; Khan, S.; Platt, M.W.; Rucker, J.J.; Weatherall, M.W.; Beri, S.; Sodergren, M.H. Clinical outcome data of children treated with cannabis-based medicinal products for treatment resistant epilepsy-analysis from the uk medical cannabis registry. Neuropediatrics 2023, 54, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcher, G.; Zwahlen, M.; Ritter, C.; Fenner, L.; Egger, M. Medical use of cannabis in switzerland: Analysis of approved exceptional licences. Swiss Med Wkly 2017, 147, w14463. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, P.F.; Wolff, R.F.; Deshpande, S.; Di Nisio, M.; Duffy, S.; Hernandez, A.V.; Keurentjes, J.C.; Lang, S.; Misso, K.; Ryder, S.; et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 2456–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, S.; Germanos, R.; Weier, M.; Pollard, J.; Degenhardt, L.; Hall, W.; Buckley, N.; Farrell, M. The use of cannabis and cannabinoids in treating symptoms of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review of reviews. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2018, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.S.; Friend, A.J.; Gibson, F.; Houghton, E.; Gopaul, S.; Craig, J.V.; Pizer, B. Antiemetic medication for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 2, CD007786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlen, M.; Hoell, J.I.; Gagnon, G.; Balzer, S.; Oommen, P.T.; Borkhardt, A.; Janssen, G. Effective treatment of spasticity using dronabinol in pediatric palliative care. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2016, 20, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, D.; Taylor, K. Medicinal cannabis for paediatric developmental, behavioural and mental health disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, E.; Goren, K.; Switzer, L.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Fehlings, D. Pharmacological and neurosurgical interventions for individuals with cerebral palsy and dystonia: A systematic review update and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2021, 63, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, S.; Murnion, B.; Campbell, G.; Young, H.; Hall, W. Cannabinoids for the treatment of spasticity. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019, 61, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, C.; Kumar, R.; Checketts, D.; Tayo, B.; Turner, S. Efficacy and safety of nabiximols cannabinoid medicine for paediatric spasticity in cerebral palsy or traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020, 62, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawliuk, C.; Chau, B.; Rassekh, S.R.; McKellar, T.; Siden, H.H. Efficacy and safety of paediatric medicinal cannabis use: A scoping review. Paediatr Child Health 2021, 26, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, K.; Dupont, C.; Weber, P.; Grunt, S.; Wilhelm, I.; Eigenmann, D.E.; Reichumth, M.L.; Fankhauser, M.; Egger, M.; Lukas, F. Medical cannabis in children and adolescents in switzerland: A retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- da Rovare, V.P.; Magalhaes, G.P.A.; Jardini, G.D.A.; Beraldo, M.L.; Gameiro, M.O.; Agarwal, A.; Luvizutto, G.J.; Paula-Ramos, L.; Camargo, S.E.A.; de Oliveira, L.D.; et al. Cannabinoids for spasticity due to multiple sclerosis or paraplegia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med 2017, 34, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Hall, W. Efficacy of cannabinoids for treating paediatric spasticity in cerebral palsy or traumatic brain injury: What is the evidence? Dev Med Child Neurol 2020, 62, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockings, E.; Campbell, G.; Hall, W.D.; Nielsen, S.; Zagic, D.; Rahman, R.; Murnion, B.; Farrell, M.; Weier, M.; Degenhardt, L. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain 2018, 159, 1932–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, J.; Samuelly-Leichtag, G. Efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E755–E796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, C.T.; Meehan, E.M.; Harvey, A.R.; Antolovich, G.C.; Morgan, P.E. Prevalence and characteristics of pain in children and young adults with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019, 61, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascia, M.M.; Carmagnini, D.; Defazio, G. Cannabinoids and dystonia: An issue yet to be defined. Neurol Sci 2020, 41, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libzon, S.; Schleider, L.B.; Saban, N.; Levit, L.; Tamari, Y.; Linder, I.; Lerman-Sagie, T.; Blumkin, L. Medical cannabis for pediatric moderate to severe complex motor disorders. J Child Neurol 2018, 33, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayasirisobhon, S. The role of cannabidiol in neurological disorders. Perm J 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: New therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009, 30, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.; Ali, D.W. Pharmacology of medical cannabis. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1162, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).