1. Introduction

The notion of mental trauma encompasses psychological damage inflicted by an event that the individual perceives as jeopardizing fundamental needs, such as self-esteem, personal safety, socio-economic standing, or physical health (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). The psychological toll of war-related violence can have enduring ramifications on the emotional and mental well-being of both victims and witnesses. Individuals exposed to such traumatic incidents may experience a spectrum of psychological challenges, including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, pervasive feelings of helplessness, heightened anxiety, and chronic fear.

The enduring impact of war violence extends beyond immediate harm, leaving a lasting imprint on the mental health of communities residing in conflict-affected areas. The long-term psychological consequences of mass violence are predominantly attributable to the trauma it engenders (MacDermid Wadsworth, 2010). Consequently, instances of military conflict and associated stressors can be classified as traumatic events, capable of eliciting a range of post-traumatic symptoms (Blevins et al., 2015; Paryente, 2021).

The ramifications of psychological stress are not only distressing in their immediate effects on mental well-being but also have far-reaching consequences. Elevated levels of trauma, fear, depression, and anxiety can culminate in emotional exhaustion, impair social interactions, and pose significant obstacles to daily functioning. Such psychological states frequently precipitate alterations in the behavior and decision-making patterns of affected individuals (Bayer, 2023; Bayer et al., 2019; Bayer and Shtudiner, 2023; Solomon and Bayer, 2022).

The enduring conflict between Israel and Hamas has resulted in considerable human suffering and loss for both parties. While there has been extensive research into the conflict’s dynamics, there remains a notable dearth of information concerning the psychological repercussions of rocket alarms on residents in the affected areas. This study seeks to fill this knowledge gap by examining the relationship between socioeconomic status and the prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among Israelis residing in regions impacted by the Israel-Hamas hostilities. Specifically, we investigate the association between PTSD symptoms and various factors, including the degree of exposure to rocket attacks, individual characteristics, and socio-economic variables. Our focus is on Israeli civilians who lived through the intense period of the Israeli military’s "Guardian of the Walls" operation in May 2021. The objective is to elucidate the extent to which PTSD correlates with these diverse factors, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of the psychological toll that armed conflict exacts on civilian populations.

"Guardian of the Walls" peration

During the 12-day conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza in May 2021, Hamas and other militant organizations launched a total of 4,360 rockets and mortar shells, primarily targeting densely populated areas within Israel. Of these, 3,573 rockets landed within Israeli territory, while the remainder either misfired, landing within the Gaza Strip, or fell into the Mediterranean Sea.

Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system successfully intercepted approximately 90% of the rockets aimed at populated areas. The rocket attacks directly resulted in 11 fatalities, including one soldier killed by an anti-tank missile strike. Additionally, 357 individuals sustained injuries. According to a 2022 report by The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center, the rocket attacks caused substantial damage to residential buildings, educational facilities, factories, and agricultural structures.

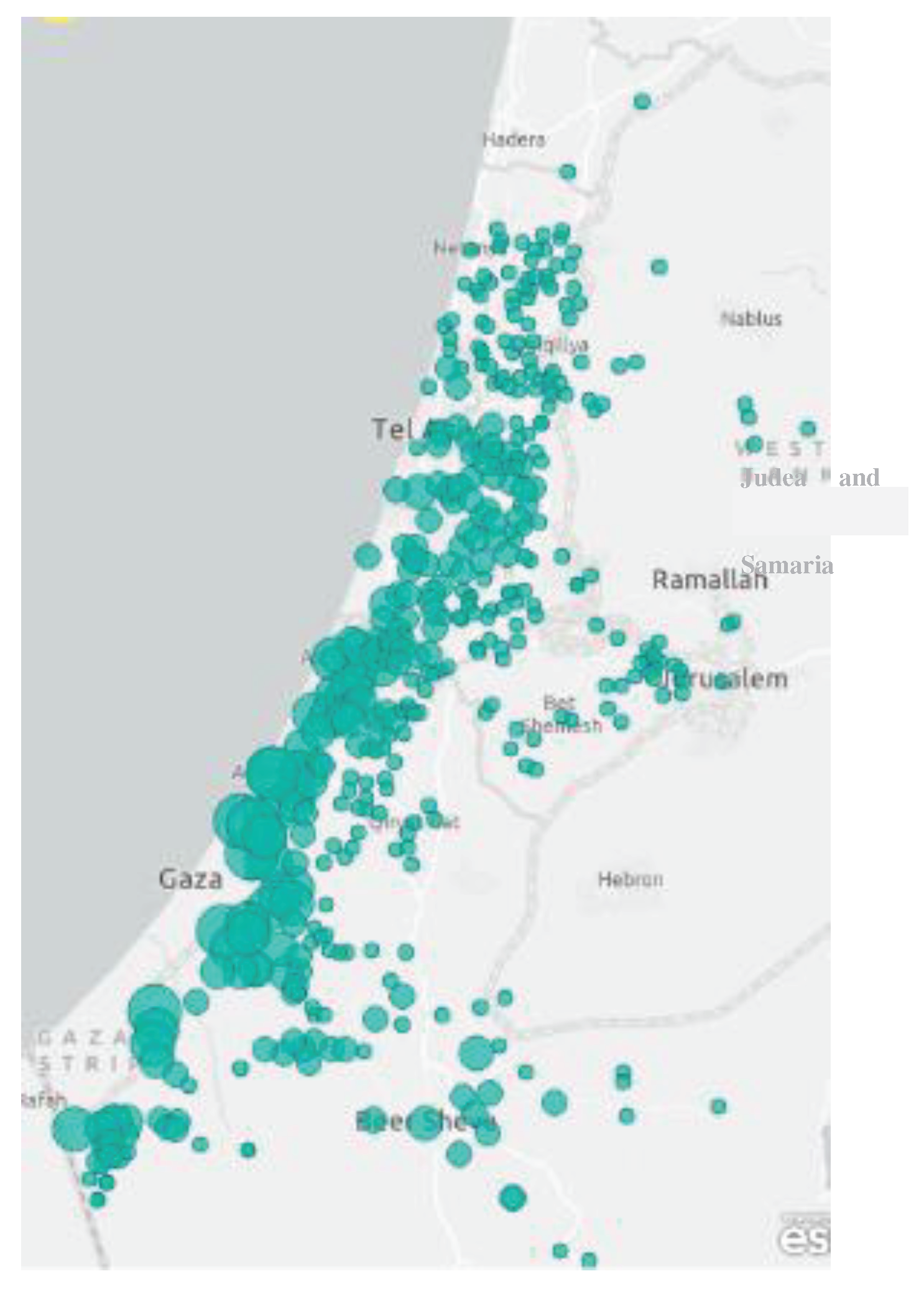

Figure 1 offers a geographical representation of the areas where rocket alerts were activated during the "Guardian of the Walls" military operation.

2. Methodology

Questionnaires

To assess the prevalence and severity of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms among participants, we employed the Post-Traumatic Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)[1]. This self-report questionnaire is a widely recognized tool for evaluating the intensity of PTSD symptoms, aligning with the 20 diagnostic criteria specified in the DSM-5 (Blevins et al., 2015). The PCL-5 consists of 20 multiple-choice questions, each scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, which participants complete to indicate the extent to which they have been troubled by each symptom over the past month.

The questionnaire has demonstrated high internal reliability, boasting an alpha coefficient of 0.96 (Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016). The cumulative scores from all items yield a total severity score, which can vary between 0 and 80. In accordance with previous research (Bovin et al., 2016; Wortmann et al., 2016), the PCL-5 was also utilized to offer a provisional PTSD diagnosis. A symptom was acknowledged if any item was rated as 2, denoting "Moderately," or higher. To align with the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which necessitate at least one item from Criterion B (questions 1-5), one item from Criterion C (questions 6-7), two items from Criterion D (questions 8-14), and two items from Criterion E (questions 15-20), we created a dichotomous variable termed ’PTSD Binary.’ This variable was assigned a value of 1 for participants meeting the diagnostic criteria and 0 for those who did not. For the scope of this study, participants who did not exhibit any PTSD symptoms were classified as "healthy," regardless of any other existing physical health conditions.

Participants were asked to provide demographic information, including gender, age, income, education level, and number of children, as well as specific experiences related to Operation "Guardian of the Walls." In this context, participants were queried about their residential locations. This data was used to create a variable that quantified the frequency of missile alarms activated in their respective localities. This variable was generated by cross-referencing the residential information supplied by participants with data from the Israeli Home Front Command, which tracks the number of alarms triggered in each settlement. Given that the Israeli defense system activates a missile alarm for each incoming missile aimed at a specific residential area, the frequency of these alarms serves as a proxy for the number of missile strikes targeting a given locality.

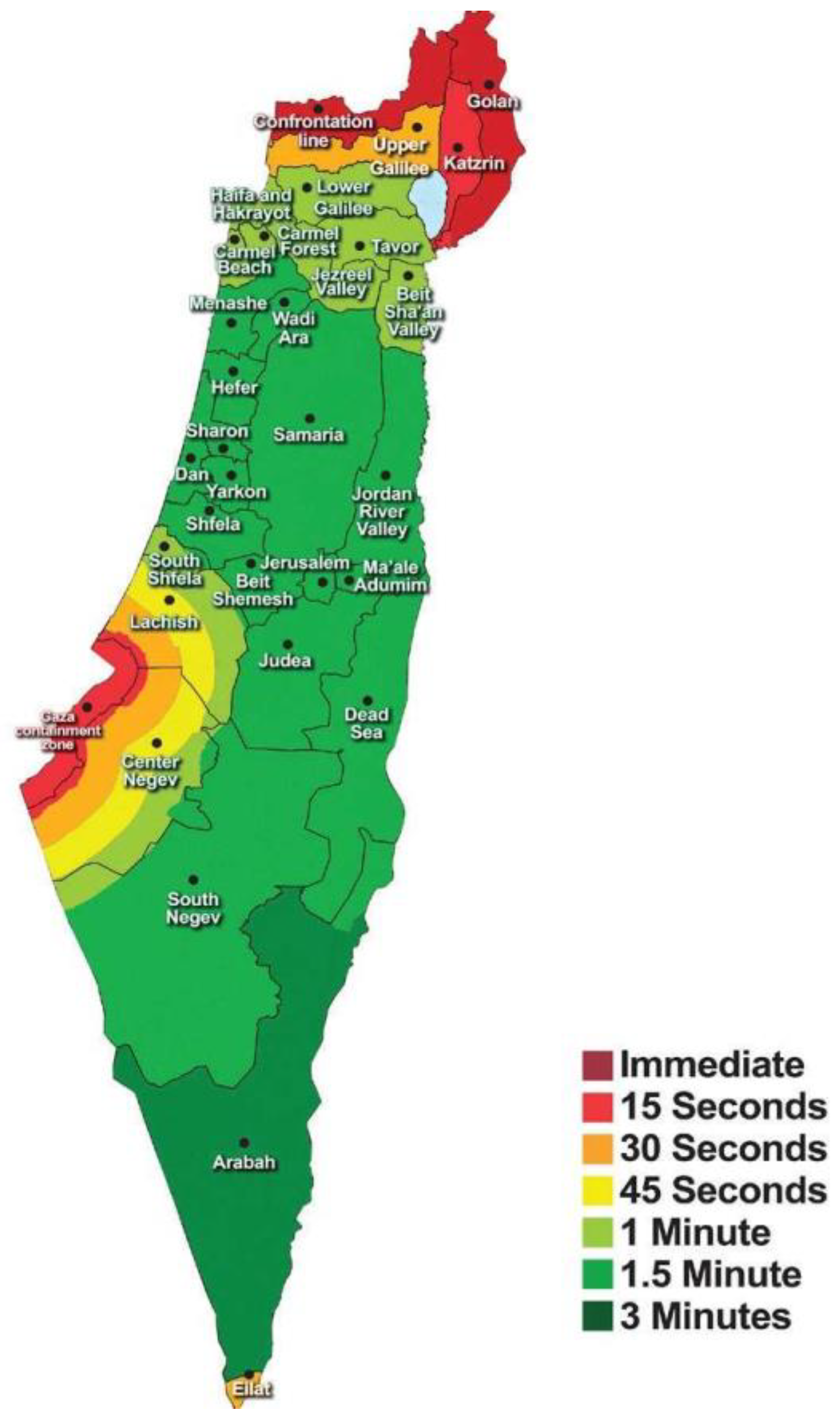

Moreover, we employed a categorical variable to delineate various regions within Israel, categorizing them based on the time residents have to seek shelter following a rocket alarm. These time-based regions were divided into seven categories, ranging from "Immediate" to "3 minutes," as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Research population

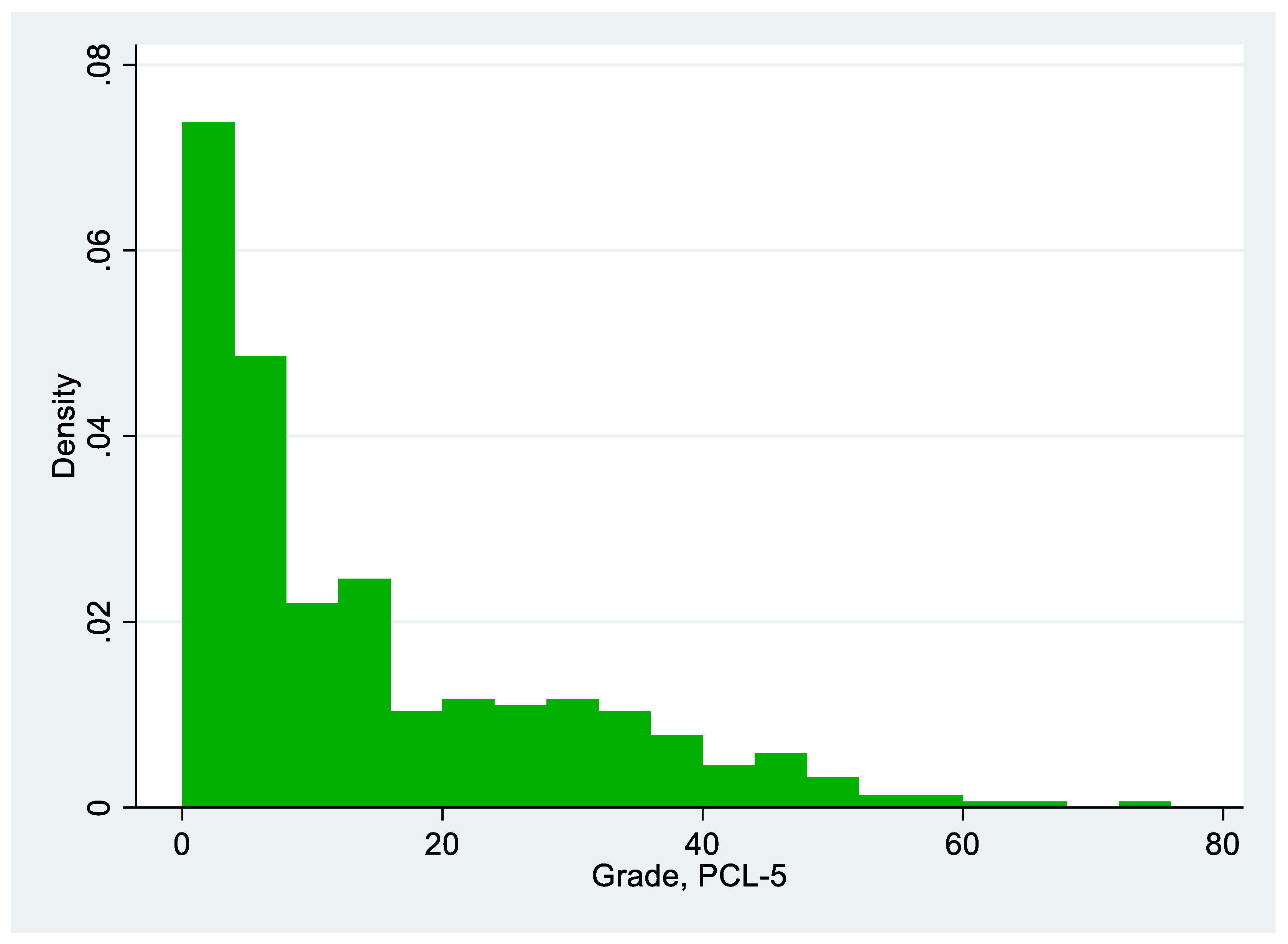

The study utilized an online survey distributed across multiple social media platforms, initially attracting 395 respondents. After eliminating thirteen entries due to either incomplete or irrelevant information, the final sample consisted of 382 participants. Of these, 78.8% were female, with an average age of 38.72 years. Participation was voluntary and free of charge. Importantly, the participants came from various regions of Israel, each affected to varying degrees by rocket attacks during the "Guardian of the Walls" operation—ranging from heavily impacted areas to those with minimal exposure. Based on the established diagnostic criteria, 62 participants exhibited PCL-5 scores indicative of significant PTSD symptoms. The distribution of these scores is graphically represented in

Figure 3.

3. Results

Table 1 provide Descriptive Statistics for Our 382-Participant Sample, categorized by the PTSD Binary Variable According to DSM-5 Post-Trauma Criteria. The participants are categorized into two groups based on a binary PTSD variable, which serves as a dichotomous indicator for meeting the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Socioeconomic status and PTSD symptoms

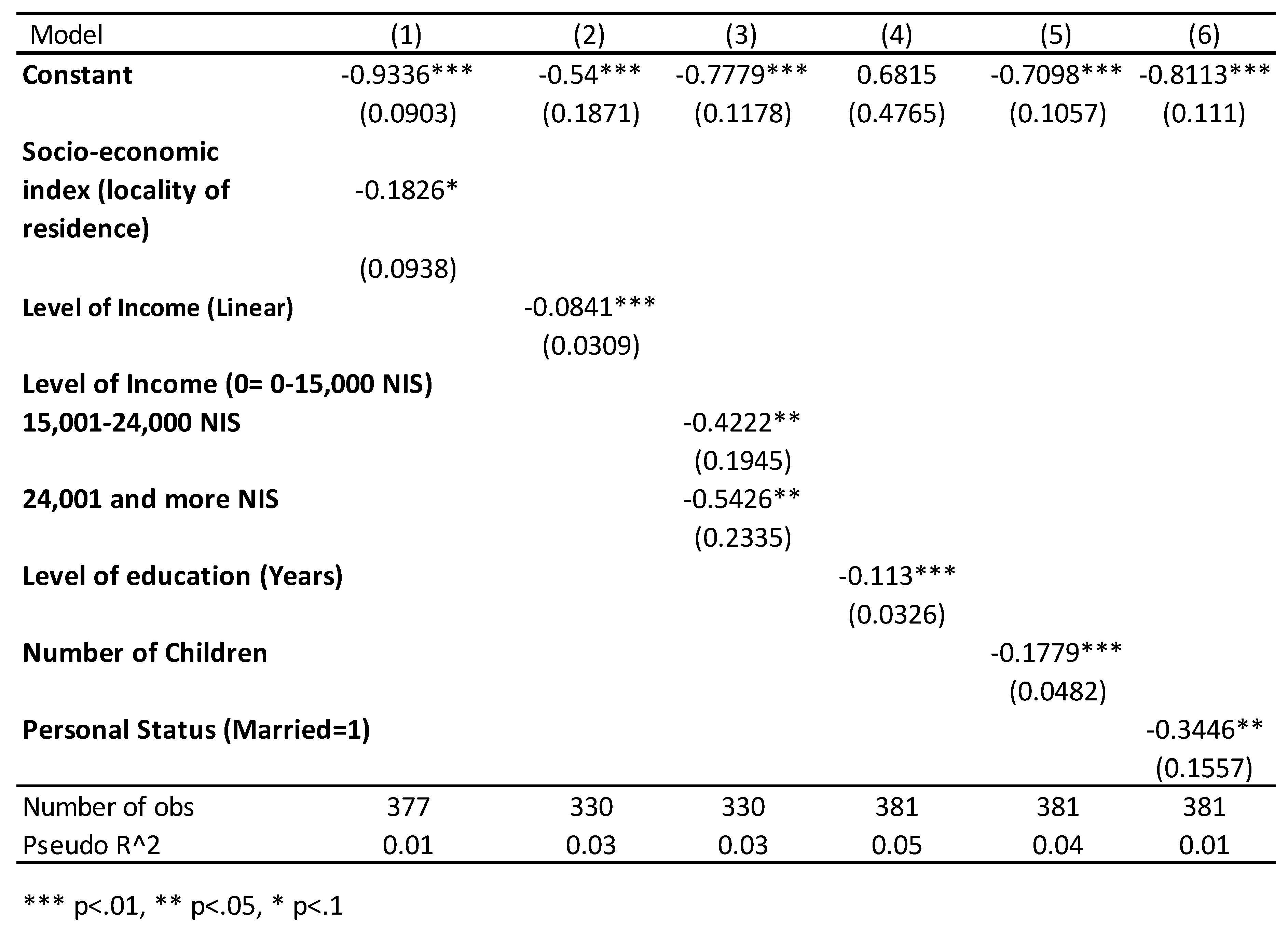

To assess the relationship between socio-economic factors and the presence of post-traumatic symptoms, we employed simple probit models. These models use a binary dependent variable to indicate whether an individual is experiencing PTSD symptoms or is considered healthy. By utilizing single-variable models, we can isolate the impact of each socio-economic factor to gauge its specific association with the likelihood of manifesting PTSD symptoms. The details of these models are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Outcomes of the Simple Probit Estimation Model, featuring a Binary Variable to Indicate Clinical-Level Presence (1) or Absence (0) of Post-Traumatic Symptoms. The model explores the association between socio-economic factors and the probability of manifesting symptoms of post-trauma.

The examination of socio-economic variables reveals that individuals possessing higher educational and income levels, as well as those who are married with more children, exhibit a statistically significant reduced likelihood of experiencing post-traumatic symptoms. Furthermore, a negative correlation exists—though with a lower degree of statistical significance—between the socio-economic standing of a respondent’s place of residence and the probability of manifesting symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Socioeconomic status and PTSD symptoms - Multi-variable model

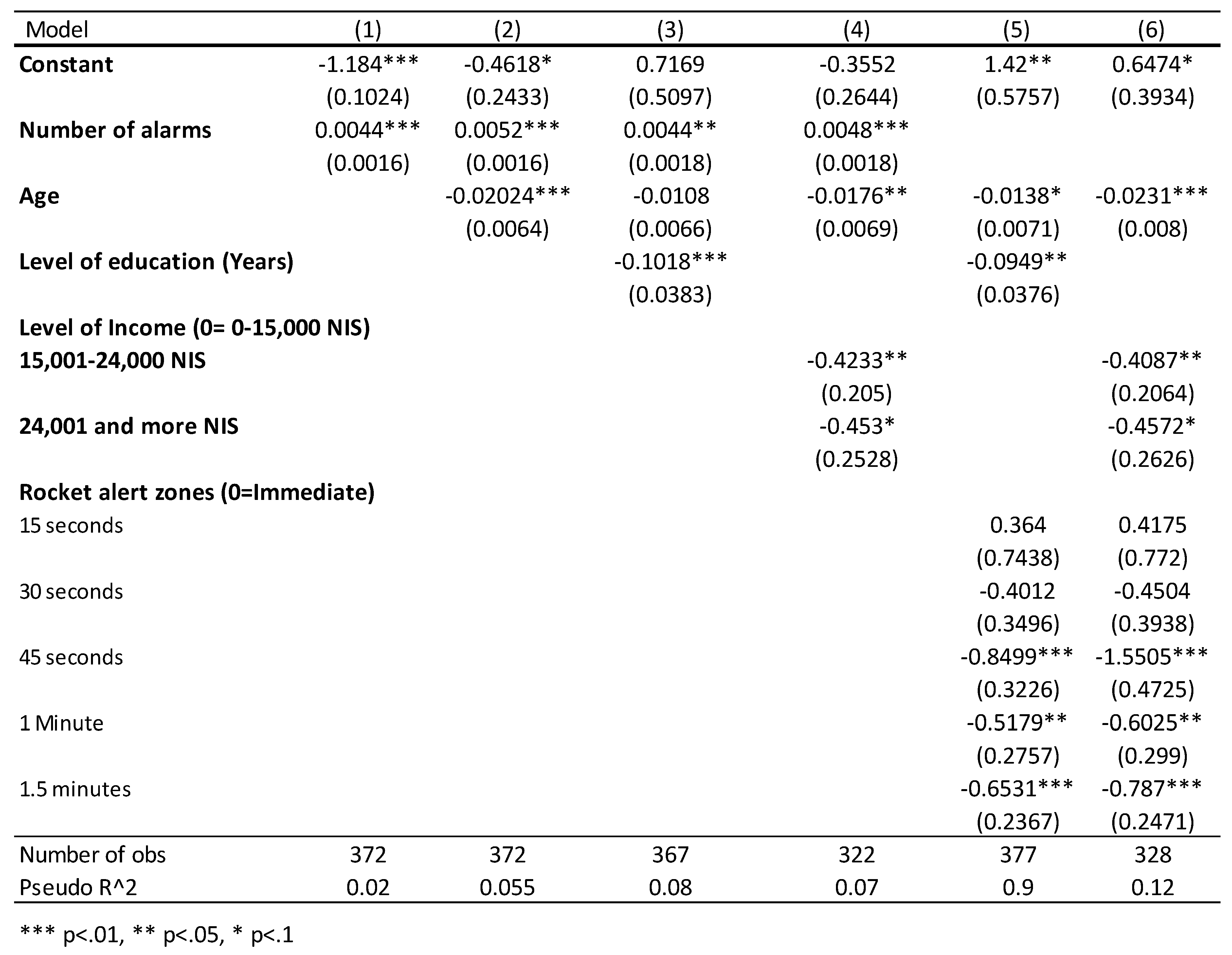

Based on the data outlined in

Table 1, significant disparities are evident between the two groups in terms of age, income, education, and number of children. To explore the interplay between PTSD symptoms, the frequency of missile alarms, and demographic factors, while controlling for these variables, we employed multivariate probit models. Table 3 showcases these models, which use a binary variable as the dependent variable to indicate the presence or absence of PTSD symptoms, as measured by the PCL-5 test. These models serve to scrutinize the association between PCL-5 test outcomes and variables such as the frequency of missile alarms in the participants’ residential areas, age, level of education, and other relevant control factors. Through this regression analysis, our objective was to pinpoint the variables most strongly correlated with PCL-5 test results.

Table 3. Multivariate Probit Estimation Model with a Binary Variable Indicating Clinical-Level Presence (1) or Absence (0) of Post-Traumatic Symptoms.

Our analysis demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation between the frequency of alarms in a residential area and the probability of manifesting post-traumatic symptoms (p<0.01 across all tested models, models 1-4). When employing the categorical area variable as a substitute for the number of alarms (models 5 and 6), it became evident that regions situated at greater distances from the Gaza Strip were less likely to fall into the PTSD category. Although distance from the Gaza Strip and the number of missile attacks are inversely related, the frequency of sirens serves as a more precise predictor of missile attacks than mere geographical proximity to the Gaza Strip. This is likely due to the variable intensity of rocket fire targeting different areas, making siren activations a more reliable gauge of missile threat.

In the majority of models that included age as a variable (except for model 3), a statistically significant relationship emerged between age and the likelihood of developing post-traumatic symptoms. Specifically, the propensity for experiencing such symptoms decreased with age, aligning with previous academic research (Kongshøj & Berntsen, 2022).

Our data also underscore the influential roles of education and income in determining an individual’s risk of falling into the PTSD category. According to our models, individuals with higher educational attainment (models 3 and 5) and greater income levels (models 4 and 6) were generally less prone to PTSD symptoms. Due to the high correlation between education and income, it was not feasible to include both variables in a single model without without affecting its accuracy. The inclusion of additional variables did not improve the model’s predictive power.

4. Discussion

Our study establishes a compelling link between the frequency of missile siren activations—serving as a proxy for exposure to missile attacks—and the manifestation of post-traumatic symptoms. Notably, individuals from lower socioeconomic strata are at elevated risk for developing PTSD symptoms, highlighting a critical public health issue.

Socioeconomic status can significantly influence the availability and quality of support systems. Individuals from lower-income brackets may lack robust support networks, rendering them more susceptible to PTSD. Education is another crucial factor; higher educational levels often provide individuals with a nuanced understanding of mental health, better access to information, and more effective communication with healthcare providers. Conversely, lower educational levels may result in limited awareness or misconceptions about PTSD, thereby impeding early diagnosis and treatment.

The intricate relationship between PTSD and socioeconomic factors is further complicated by the substantial financial strain associated with psychiatric conditions. Individuals with psychiatric disorders often struggle to maintain stable employment, exacerbating their financial instability (Kessler & Frank, 1997). This can create a self-perpetuating cycle, as those with PTSD may experience worsening symptoms and face barriers to effective treatment.

Given these complexities, it is imperative for public health initiatives and policymakers to understand these correlations to craft more targeted and accessible mental health resources. Such efforts should aim to address the elevated rates of PTSD among economically disadvantaged populations. Potential interventions could include broadening access to mental health services, enhancing educational opportunities, and initiating programs to alleviate chronic stress and trauma within these communities.

Our findings also lend credence to the potential efficacy of government policies aimed at evacuating civilians to minimize their exposure to missile alerts and attacks. However, the possible traumatic repercussions of such evacuations must be carefully weighed, and additional research is needed to fully understand these impacts. This is particularly relevant for vulnerable populations, such as young individuals without extensive family support or those in economically disadvantaged situations.

It is important to note that our study has some limitations. One significant limitation is that the assessment of PTSD was based on self-reported questionnaires rather than clinical evaluations. While the PCL-5 questionnaire is a widely used and validated tool for assessing post-traumatic symptoms, it is not a substitute for a comprehensive clinical diagnosis. Therefore, the prevalence and severity of PTSD symptoms may be different if assessed through clinical interviews or other diagnostic methods. Future research should consider incorporating clinical assessments for a more accurate understanding of PTSD prevalence and its associated factors. Another limitation of our study is that it did not assess the impact of missile alerts on children. A follow-up study focusing on this demographic, and incorporating our findings related to age, would be invaluable for a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

5. Declarations

The authors of this article declare that the article is the original work of the authors, has not been published or submitted elsewhere, and that all sources used in the preparation of this article have been properly cited and referenced. Furthermore, no financial support was received for the writing of this article, and there is no direct or indirect financial involvement with any of the organizations or individuals mentioned. Additionally, no conflicts of interest exist with regard to the authorship or publication of this academic article. Before conducting any research described in this article, the authors obtained approval from the relevant institutional ethics committee and ensured that the research was conducted ethically by relevant ethical guidelines. Research data is available on OSF.io, a platform for storing, sharing, and managing research data.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) DSM-IV-TR, 4th ed.

- Anderhub, V. , Güth, W., Gneezy, U., & Sonsino, D. (2001). On the interaction of risk and time preferences: An experimental study. German Economic Review 2, 2399–253.

- Bayer, Ya’akov M. (2023) Challenges in Autonomous Financial Management Among Patients with Serious Mental Illness During Long-Term Hospitalization: Insights from Israel. Preprints 2023.

- Bayer, Ya’akov M., Ruffle Bradely, Zultan Ro’i, Dwolazky Tzvi (2018) Time preferences in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Laurier Centre for Economic Research and Policy Analysis: Toronto.

- 6. Bayer, Ya’akov M. Shtudiner, Z., Suhorukov, O., & Grisaru, N. (2019). Time and risk preferences, and consumption decisions of patients with clinical depression. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 78, 138–145.

- 7. Bayer, Ya’akov M. and Shtudiner, Ze’ev (2023) Sirens of Stress: Financial Risk, Time Preferences, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - Evidence from the Israel-Hamas Conflict. Journal of Health Psychology.

- Blevins, C. A. , Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The post-traumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM--5 (PCL--5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of traumatic stress 28, 489–498. [PubMed]

- Bovin, M. J. , Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological assessment 28, 1379. [PubMed]

- Ehlers, A. , & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior research and therapy 38(4), 319–345.

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2012), Financial Literacy Survey: Knowledge, Opinions, and Behavior in Financial Issues, Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics [Hebrew].

- Kessler, R. C. , & Frank, R. G. (1997). The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychological medicine 27(4), 861–873. [PubMed]

- Kongshøj, I. L. L. , & Berntsen, D. (2022). Is young age a risk factor for PTSD? Age differences in PTSD-symptoms after Hurricane Florence. Traumatology.

- Langner, T. S. , & Michael, S. T. (1963). Life stress and mental health: II. The midtown Manhattan study.

- MacDermid Wadsworth, S. M. (2010). Family risk and resilience in the context of war and terrorism. Journal of Marriage and Family 72, 537–556. [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R. F. , Wyshak, G., & Lavelle, J. (1987). The psychosocial impact of war trauma and torture on Southeast Asian refugees. The American journal of psychiatry.

- Paryente, B. (2021). Parenting Experiences under Ongoing Life-threatening Conditions of Missile Attacks. Journal of Child and Family Studies 30, 1685–1696. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. , & Bayer, Y. M. (2022). Reading mental harm through the lens of socio-economic rights: An empirical study of the impact of education, family, and income on the notion of civilian mental harm in warfare. Brunel University London, Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

- The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center. Available online: https://www.terrorism-info.org.il/ (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Vinck, P. , Pham, P. N., Stover, E., & Weinstein, H. M. (2007). Exposure to war crimes and implications for peace building in northern Uganda. Jama 298(5), 543–554. [PubMed]

- Wortmann, J. H. , Jordan, A. H., Weathers, F. W., Resick, P. A., Dondanville, K. A., Hall-Clark, B.,... & Litz, B. T. (2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological assessment 28, 1392. [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

| [1] |

It is important to note that the questionnaire is one of the diagnostic tools for people with PTSD. A complete diagnosis of PTSD includes a clinical diagnosis that was not included in our study. Therefore, this is not a clinical diagnosis but a general and partial evaluation and assessment according to the validated questionnaire. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).