1. Introduction

The L-asparaginase (EC 3.5.1.1) hydrolyzes L-asparagine into aspartic acid and ammonia via an intermediate beta-acyl-enzyme [

1,

2]. This well-known enzyme is used in cancer therapy, such as childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and lymphoid system disorders [

3]. The antineoplastic action of L-asparaginase happens because cancer cells are not able to synthesize enough L-asparagine and the depletion of this compound in serum causes the death of cancer cells. However, several side effects have been reported in patients treated with the available L-asparaginases in the market. In addition, L-asparaginase has been frequently used in the food industry to reduces the formation of carcinogenic acrylamide in food during the heat treatment [

4,

5]. Therefore, recent studies have been focusing on finding new sources for obtaining this pharmaceutically and biotechnologically important protein [

6,

7]. Likewise, the studies look for the optimization of the production media [

8,

9] and the achievement of higher levels of the purified protein using several strategies such as including a signal peptide, optimizing a promoter to obtain extracellular proteins [

10,

11], and truncation from the N-terminus of L-asparaginase [

12,

13]; all of them to have better quality, efficiency, and safety of the L-asparaginase.

The sources for obtaining this protein are diverse including plants, animals, bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. However, bacterial sources are the most interesting and more comprehensively studied because of their easy handling and genetic manipulation, fast growth, lower genome complexity, and economically more viable production cost [

9,

14]. Moreover, L-asparaginases from bacteria isolated from hypersaline environments, especially from the

Bacillus genus, have been described as the most promising anticancer compounds as they show lower immune response and higher activity [

15,

16,

17]. The genome

of Bacillus subtilis (

B. subtilis) has two genes encoding for L-asparaginase (

ansA and

ansZ). The

ansA gene encodes L-asparaginase I, an intracellular protein with low affinity to the substrate. While the

ansZ gene encodes L-asparaginase II, an extracellular enzyme with higher substrate affinity[

12,

18].

In this paper, we describe cloning, heterologous expression, and purification of novel, N-terminally truncated, type II L-asparaginase of B. subtilis CH11 from Chilca salterns in Lima-Peru. In addition, we have characterized its thermostability along with contribution of temperature, pH, and co-factors to the enzymatic activity. We also determined the kinetic parameters of the enzyme.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria strains and chemicals

Bacillus subtilis CH11 strain belongs to the collection of Prof. Amparo Zavaleta, Molecular Biology Laboratory, Universidad Nacional de San Marcos (Lima, Peru). T4 DNA ligase, Phusion DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS were purchased from Thermo Scientific® (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Restriction endonucleases and 1 kb DNA Ladder were from New England Biolabs® (Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit was from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany). pET-15b and BugBuster® Master Mix from Novagen® (Merck - Darmstadt, Germany). Finally, Bicinchoninic Acid Kit were from Sigma-Aldrich® (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

2.2. Cloning of the ansZP21 gene encoding L-ASNasaZP21

The ansZ gene without the signal peptide YccC (first 60 base pairs) denominated ansZP21, was amplified by PCR from the extracted DNA of Bacillus sp. CH11 using the forward primer 5’-TTT CAT ATG CCA CAT TCT CC T GAA ACA AAA GAA TCC CC-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-TGC CGG ATC CTC AAT ACT CAT TGA AAT AAG C-3’. The gene was cloned using the restriction enzymes NdeI and BamHI whose recognition sequences are in bold in the primers described above. PCR was carried out using Phusion DNA polymerase (2 U µL-1) and the reaction conditions were an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 sec; followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 10 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 20 sec; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min (T100 Thermal Cycler, Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). The PCR products were cloned into pET-15b using 1 U of T4 DNA ligase and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. Then, the plasmids were extracted using the kit QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit and sending for sequencing to confirm the correct cloning of the ansZP21 gene. The correct expression vector was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS host cells.

2.3. Expression and purification of L-ASNasaZP21

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells were used for protein expression. Cells were grown using LB-Miller medium supplemented with 100 µg mL-1 ampicillin at 37°C. Protein expression was induced by adding Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM when the OD600 reached 0.6. Post-induction, the culture was incubated for 14 h at 22 °C and 230 rpm. Subsequently, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2133 g for 20 min at 4 °C and disrupted using BugBuster® Master Mix reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions. The clarified lysate containing 6X-His-tagged L-ASNasaZP21 was recovered and used for purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) using an FPLC system (ÄKTA start, GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Briefly, the clarified lysate in 50 mM Tris-HCl containing 100 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.5 was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated HisTrapTM FF column of 5 mL (GE Healthcare). Unbound proteins were eliminated by washing the column with 5 column volume (CV) of the buffer, and finally, the enzyme was eluted by linear gradient of imidazole (up to 500 mM), desalted in Tris-HCl pH 8.5, and stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

2.4. Molecular weight determination

The molecular weight of the purified L-ASNasaZP21 was determined by size exclusion chromatography using a HiPrep

TM 16/60 Sephacryl® S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare) and 50 mM Tris-HCl containing 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.5 at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min

-1. The standard curve was performed using a Protein Standard Mix 15-600 kDa (Sigma-Aldrich

®, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) composed of ρ-aminobenzoic acid (0.14 kDa), ribonuclease A type I-A (13.7 kDa), grade VI albumin (44.3 kDa), γ-globulin (150 kDa) and thyroglobulin (670 kDa). The estimation of the molecular weight was made on a semi-log graph following the method described by Mahajan

et al. [

19]

2.5. SDS-PAGE and zymography

The purity fraction of the L-ASNasaZP21 was evaluated by SDS-PAGE using β-mercaptoethanol as reducing agent. The zymography was used to evaluate the L-asparaginase activity

in situ following electrophoresis with 5% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was incubated in a solution containing 25 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.6, 2 mL of 189 mM L-asparagine, 2 mL of 2 M hydroxylamine, 1.6 mL of 2 M NaOH. The incubation was performed at 37 °C for 20 min in a Mini Rocker Platform (Bio-Rad). Finally, the gel was stained with a solution containing 10% FeCl

2, 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and 0.66 M HCl which allows visualizing a positive reaction based on the L-aspartic acid β-hydroxamate (AHA) colorimetric assay [

20]

2.6. L-asparaginase activity and protein assay

The L-asparaginase activity was evaluated by Nessler’s method with modifications [

21]. The reaction consisted of 100 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.6, 10 μL of 189 mM L-asparagine, 90 μL of H

2O, and 10 μL of sample. This mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C and stopped using 10 μL of 1.5 M trichloroacetic acid. A volume of 25 μL of the previous reaction was mixed with 25 μL of Nessler solution and 200 μL of H

2O and the released free ammonia was quantified measuring the absorbance at 436 nm. In the negative control, H20 was used instead of enzyme, and for the blank, the reaction was stopped before adding the enzyme. A standard calibration curve was performed using different known concentrations of ammonium sulfate. One unit of enzyme (U) produces 1.0 µmole of ammonia from L-asparagine per minute under optimum conditions.

Protein concentration was measured according to Bicinchoninic Acid Kit for 96-well plate-assay following the manufacturer’s instructions. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was used as a standard.

2.7. Biochemical characterization

The temperature effect on L-ASNasaZP21 activity was investigated between 22 and 80 °C at fixed pH equal to 8.6. The pH effect was evaluated between 3.0 and 10.0 using appropriate buffers: pH 3.0–5.0, 50 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0–7.0, 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0–9.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 10.0, sodium bicarbonate-NaOH. Temperature was fixed at 60 °C. The results were expressed as relative activity (%).

The half-life of L-ASNasaZP21 at 22, 37, and 60 °C was determined by incubation from 1 to 24 h, and the residual activity was measured at 60 °C for 10 min by Nessler method with modifications described above, a control sample without incubation was used. The rate of the reaction was calculated by plotting the time (h) along the X-axis

vs the logarithmic of the residual activity along the Y-axis. The inactivation rate constant (

k) was estimated using linear regression[

22]:

Where [A]

0 is the control activity (100 %) and the [A]

t is the activity at an indicated time

t (h). The half-life was determined with the following equation[

23]:

The effect of inhibitors and ions was examined following the same protocol described above and supplementing the standard reaction mixture with appropriate inhibitors and salts. The tested inhibitors were PMSF, Urea, Mercaptoethanol, DL-Dithiothreitol, SDS, and EDTA at final concentration of 10 mM and Glutathione at final concentration of 5 mM. The tested salts with mono and divalent cations were NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, BaCl2, CuCl2, and CoCl2, all at final concentration of 100 mM. The enzyme activity was expressed as relative activity (%) compared to control without any supplemented component.

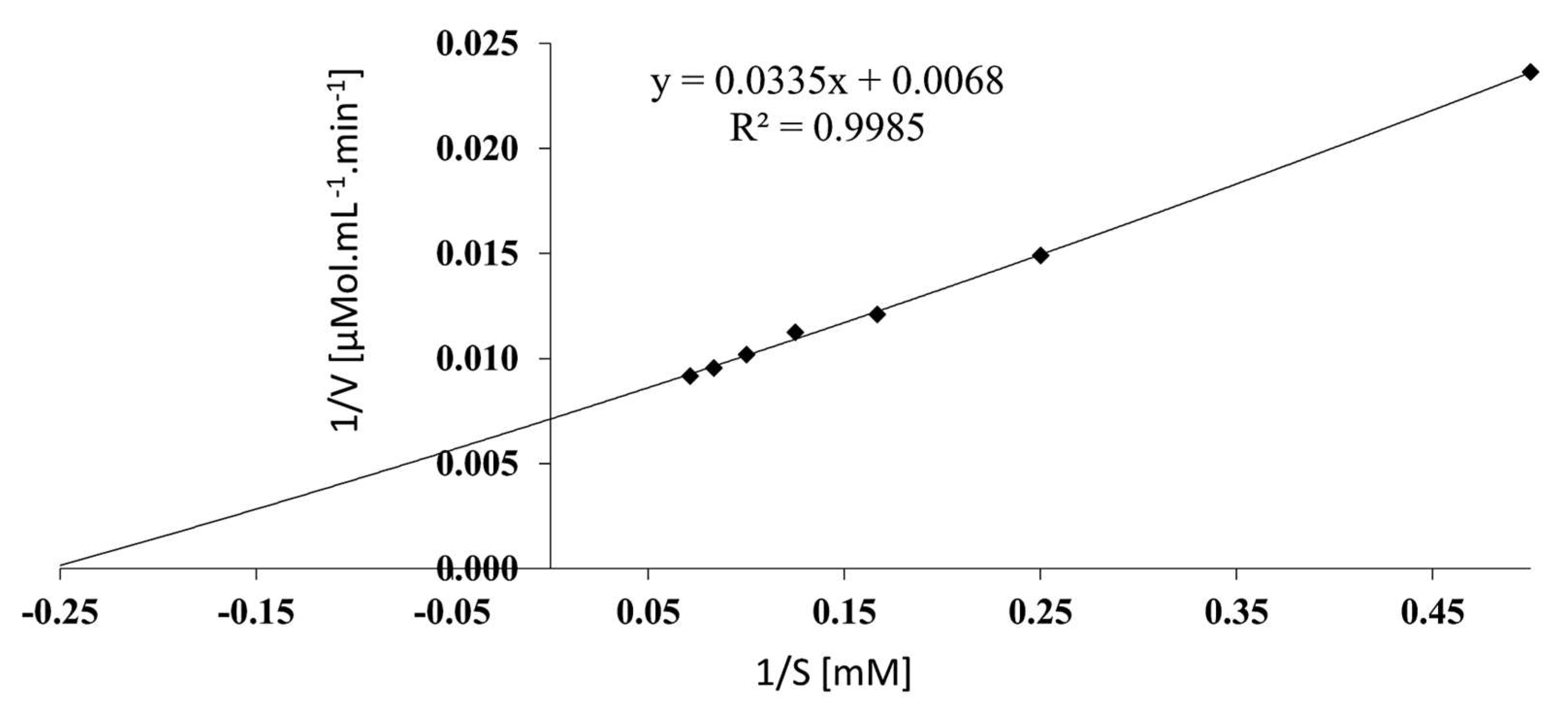

The reactions for kinetic assays were carried out at pH 9, 60 °C, and with an incubation time of 10 min. The substrate was tested in a concentration range from 2 to 14 mM. The Vmax and Km values were calculated by the Lineaweaver-Burk plot.

2.8. Data collection and analysis

All the analysis was carried out in duplicate and expressed as the mean ± standard deviations (SD). Data were evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.2. software (San Diego, USA) with significance defined as p < 0.01.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cloning of ansZP21 gene and sequence analysis

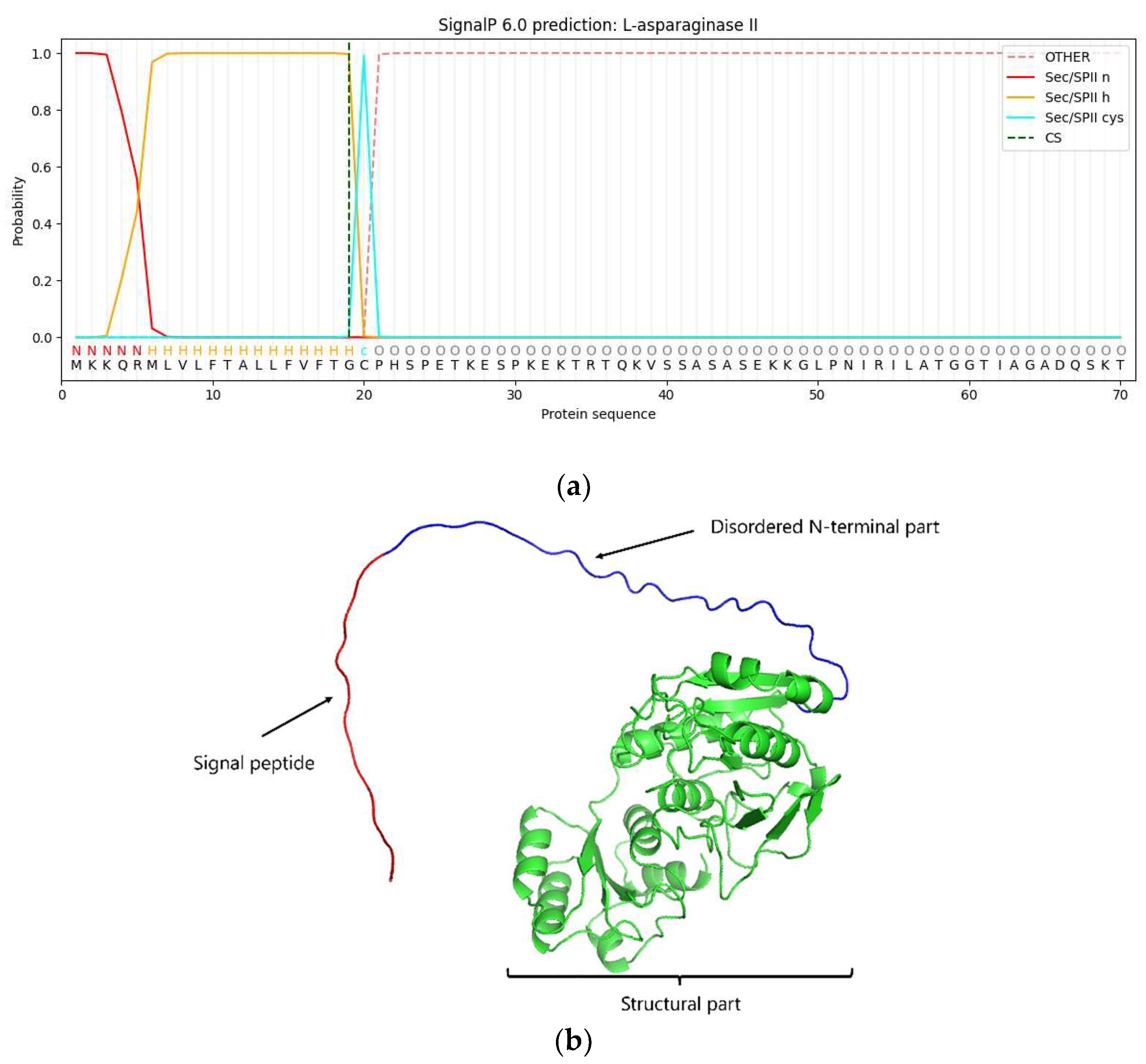

The native

ansZ transcript included a signal peptide (amino acid residues 1-19) identified via bioinformatics analysis conducted with SignalP – 6.0 server with a probability of 0.996% (

Figure 1a). This finding is in line with the AlphaFold2 structure prediction of L-asparaginase II from

B. subtilis (

Figure 1b) [

24,

25], and that lipoprotein signal peptide type II

YccC reported in

B. subtilis was found to be in the N-terminal amino sequence of the

ansZ gene used in the present study [

26,

27]. In addition, Onishi

et al. [

12] reported that

E. coli might not process the signal peptide of L-asparaginase from

Bacillus sp., resulting in incorrect protein folding leading to a lower purification yield and purity. On the other hand, studies have suggested that the formation of the mature protein is involved in the proper folding, where the diacylglycerol modification of the Cys20 residue is required for the signal peptide release [

12,

28,

29], it indicates a possible post-translational modification that might remove the N-terminal 6X-His-tag. Therefore, the lipoprotein signal peptide between 1-19 amino acid residues and Cys20 residue were removed when cloning the protein for

E. coli expression. Also, the molecular weight and isoelectric point of the mature protein were 37.91 kDa and 6.16, respectively, both estimated by ProtParam (SIB bioinformatics resource). In bases on that, the

ansZP21 gene has 1068 bps (

Figure 1), encoding the protein L-ASNasaZP21 of 355 amino acids.

3.2. Expression and purification of L-ASNasaZP21

B. subtilis L-ASNasaZP21 expressed in heterologous

E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS and purified showed a specific activity of 234.38 U mg

-1. This specific activity was higher than previously reported values in similar proteins [

10,

12,

30]. This may result from a better protein solubility and reduced misfolding associated with N-terminal truncation and optimized expression protocol [

13,

31]. Besides, Moura

et al. [

13] reported that

E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (89.0 ± 4.4) expresses L-asparaginase with higher enzymatic activity compared to other

E. coli strains. (T7 Express Crystal, 57.0 ± 1.7; Turned (DE3), 41.6 ± 2.0; C43 (DE3), 22.4 ± 1.6; BL21 (DE3), 12.5 ± 1.2; Lemo21 (DE3), 10.9 ± 1.2; SHuffe T7, 4.9 ± 1.9; GroEL (DE3), 2.2 ± 2.1)

A purification factor of 85.2-fold and a recovery yield of 61.9 % were achieved after the affinity chromatography (

Table 1). The N-truncated version of our L-asparaginase was expressed including an N-terminal 6X-His-tagg which allowed high selectivity to obtain a highly purified protein from a complex sample [

27,

32]. Studies on other L-asparaginases type II from

Bacillus sp. using affinity chromatography have been reported, obtaining activities of 4438.6 U mg

-1[

33], 1146 U mg

-1[

34], and 162.9 U mg

-1 with a recovery yield of 67.21% [

10].

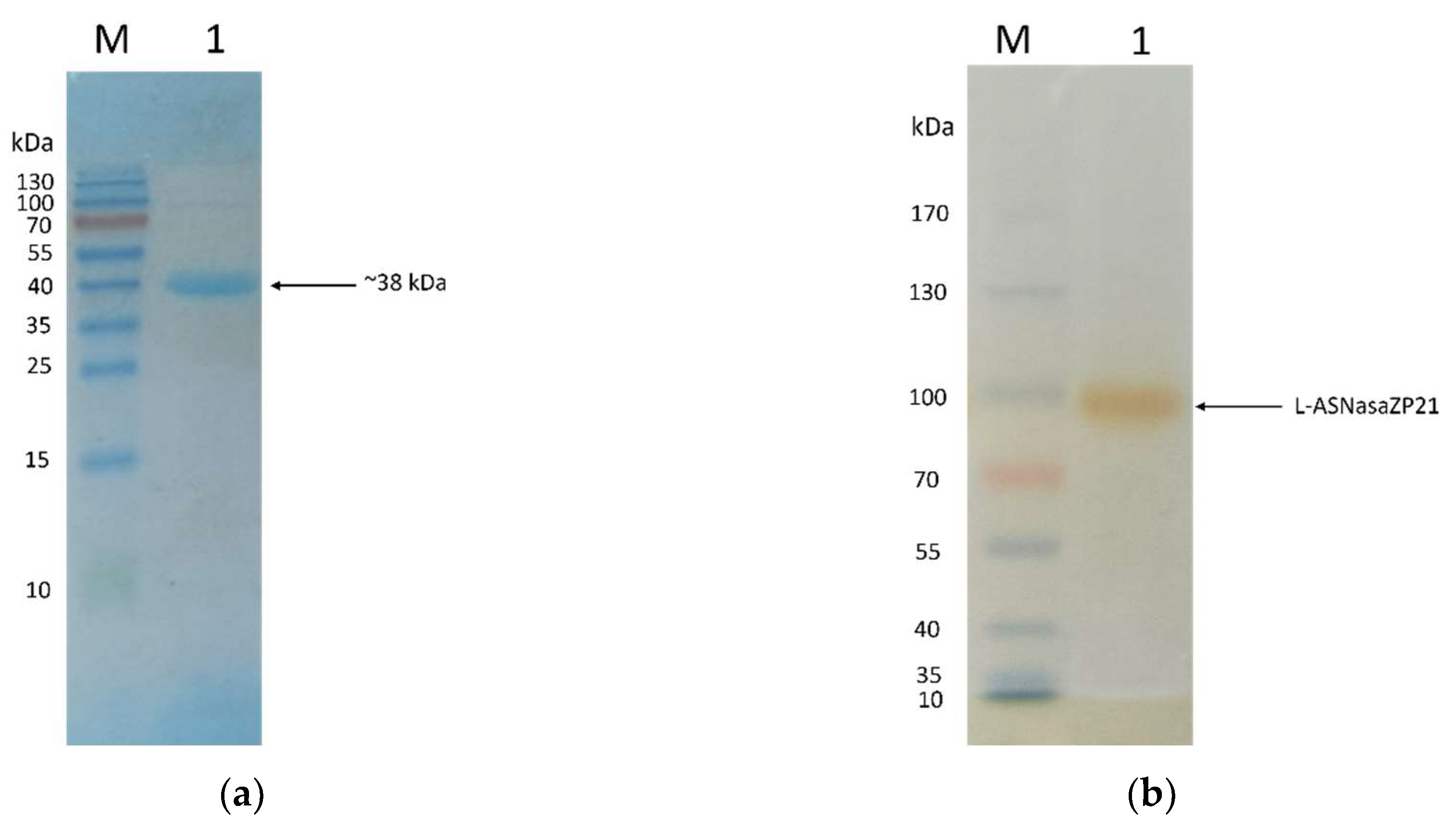

3.3. Molecular weight determination, SDS-PAGE, and zymography

The SDS-page analysis shows that the molecular weight of L-ASNasaZP21 was 38 kDa as expected and the purity grade was relatively high (

Figure 2a). The zymography shows the L-asparaginase activity

in situ, although the molecular weight does not match with the one observed in denaturing conditions (

Figure 2b). This is associated to presumably oligomerization of the protein in native conditions. In accordance with that, the molecular weight determined by gel filtration chromatography was 155 kDa, indicating L-ASNasaZP21 possible tetrameric structure in agreement with preliminary studies [

35,

36].

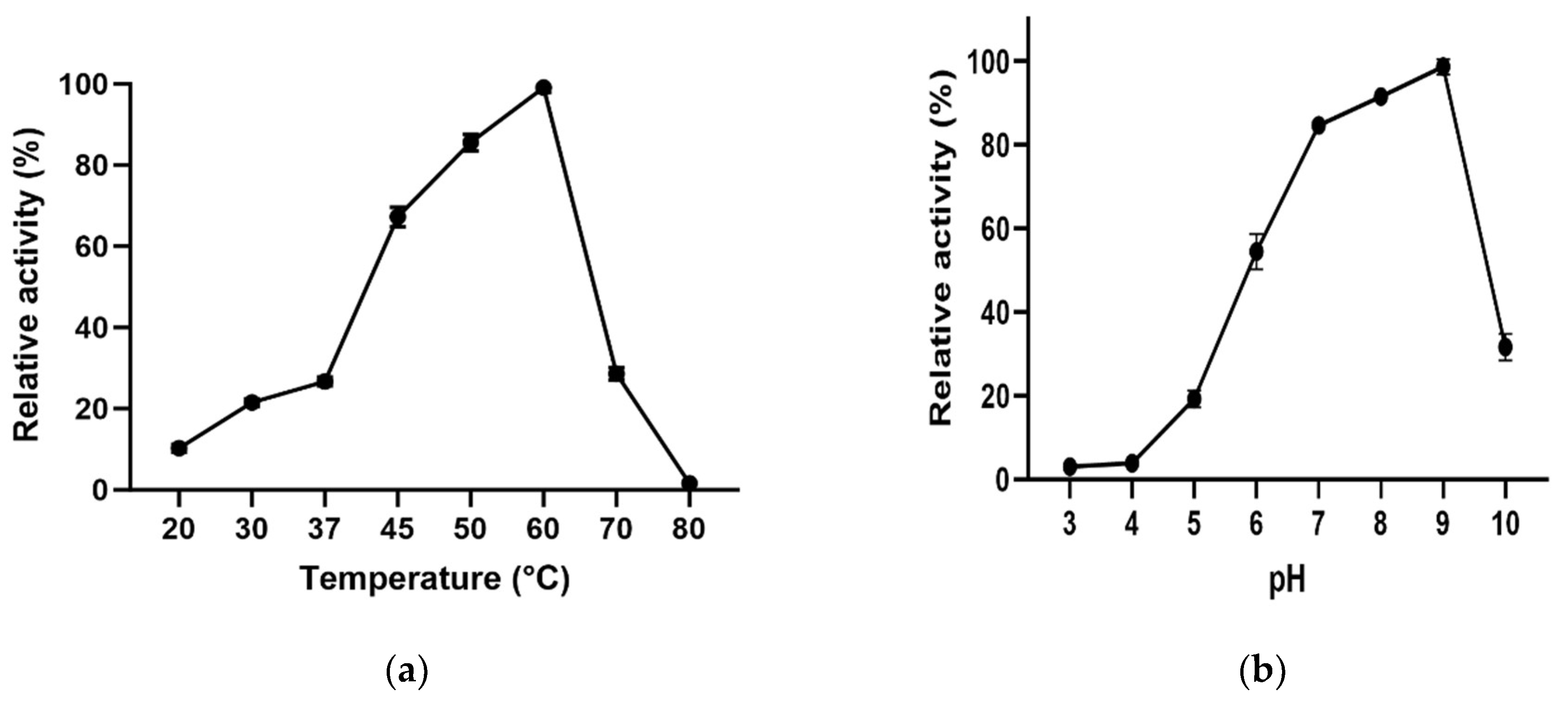

3.4. Effect of temperature and pH

L-ASNasaZP21 exhibited an optimum activity at 60 °C (

Figure 3a) which was 2.7-fold higher than at 37 °C. The enzyme retained more than 60% of its activity at 45 °C and around 30% at 70 °C. The optimum pH of L-ASNasaZP21 was 9.0 (

Figure 3b) keeping more than 80% of its activity at physiological pH (pH 7). Most bacterial L-asparaginases have been shown optimum activity between 30 and 50 °C [

37] and at pH between 7.0 and 9.0 [

38]. These results agree with Feng

et al. [

30], who reported an N-truncated L-asparaginase with an optimum temperature of 65 °C. However, they differ from those reported for other type II L-asparaginases from

B. subtilis, which exhibited optimum activity at 40 °C and pH of 7.5 [

39], as well as at 37 °C and pH of 5.0 [

40]. Onishi

et al. [

12] suggested that the different values in optimum temperature and pH may be caused by variations in the N-terminal structure of the protein. Also, these differences might be because of the protein is from a halotolerant bacterial in line with Lakshmi

et al. [

41]

3.5. Effect of metal ions and inhibitors

The effects on enzymatic activity of inhibitors and ions are described in

Table 2. The activity was slightly enhanced by KCl (1.2-fold) and MgCl

2 (1.5-fold). While the highest improvement in the activity was observed in the presence of CaCl

2 (3.1-fold). This positive effect of ions on the activity has also been described for L-asparaginases from

B. sonorensis [

33], and

B. amyloliquefaciens MKSE [

27]. Some authors have reported the inhibitory effect of MnCl

2, CuCl

2, and CoCl

2 on L-asparaginases activity[

30,

40]

On the other hand, L-ASNasaZP21 activity was enhanced in the presence of Mercaptoethanol (1.4-fold) and DL-dithiothreitol (2.7-fold). The presence of reducing agents might reduce possible protein aggregation due to intermolecular disulfide bridge formation. These findings are similar to L-asparaginases from

Pectobacterium carotovorum [

42] and

Erwinia carotovora [

43]. The activity was partially inhibited by EDTA, while the presence of SDS dropped the activity to zero as mentioned by other authors [

19,

44].

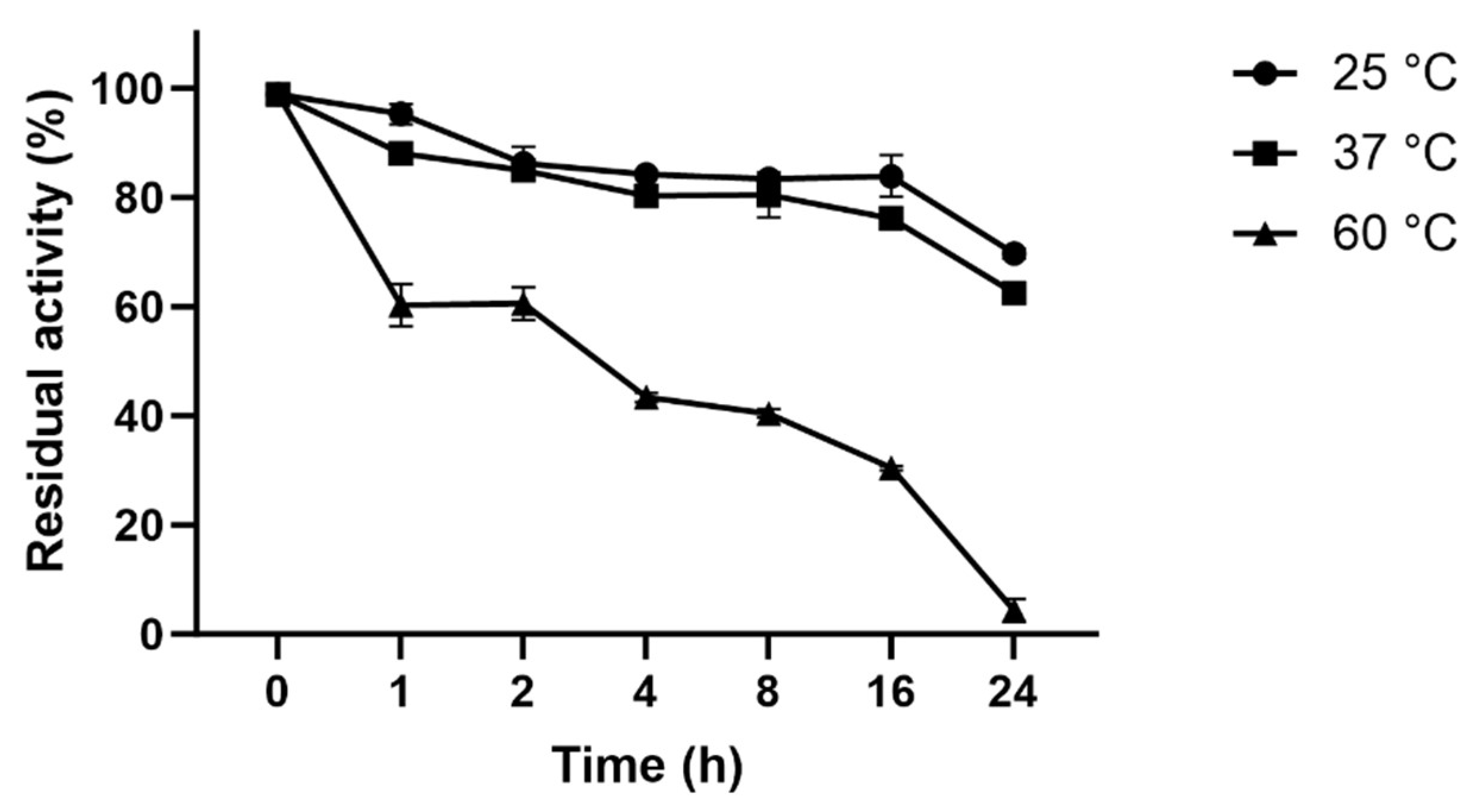

3.6. Thermostability of L-ASNasaZP21

Figure 4 shows the inactivation process at 22, 37 and 60 °C. The half-life of L-ASNasaZP21 at 60 °C was 3 h 48 min and it retained around 60% of its activity after 1 h of incubation. At 25 and 37 °C, the half-life was > 24 h and retained 50% of its activity after 24 h of incubation. L-ASNasaZP21 showed better thermal stability compared with previously studied L-asparaginases [

22,

39], which could be promising for industrial applications.

3.7. Determination of kinetic parameters

The kinetic constants were estimated by the Lineaweaver-Burk plot (

Figure 5). V

max and K

m were 145.2 µmol mL

-1 min

-1 and 4.752 mM, respectively. The K

m value was comparable to 5.29 mM described by Feng

et al [

30]

, and 7.06 mM by Onishi

et al [

12] and clearly in contrast to 0.43 mM reported by Jia

et al [

39].

5. Conclusions

This work contributes to the knowledge of L-asparaginases since it describes a novel type II L-asparaginase from B. subtilis isolated from a natural extreme environment and reports the biochemical properties of the engineered L-ASNasaZP21. The major modification to native enzyme sequence includes the removal of the signal peptide in the N-terminus. This improved the yield of the protein in heterologous expression system facilitating the purification procedures. The data show that L-ASNasaZP21 has higher thermal stability compared to other L-asparaginases and the activity is well retained even if the protein is incubated for a period longer than 3 hours at 60 °C; also the optimal pH is slightly higher. Both these characteristics are particularly interesting for industrial usage of L-ASNasaZP21. Moreover, the study reports a possible multimeric structure of the enzyme, which is obviously retained without the signal peptide. The multimeric structure of the enzyme might be crucial for the catalytic activity, therefore L-ASNasaZP21 represents an optimal protein construct for both improving protein expression and purification and retaining the enzymatic activity. It is worth noting that the presence of CaCl2 resulted in a 3.1-fold enhancement of the enzyme activity. This is, once more, valuable characteristics for potential industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z.; methodology, A.A., G.M., L.A. and P.P.; software, A.A., L.A. and P.P.; validation, A.A., L.A. and P.P.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A. and A.Z.; resources, A.A., L.A. and P.P.; data curation, C.F. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., C.F. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.A., G.M., C.F., L.A., P.P. and A.Z.; visualization, A.A., C.F. and P.P.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, A.A. and A.Z.; funding acquisition, A.Z. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by FONDECYT-CONCYTEC, grant number 169-2017. GM received grant from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP – grant number 2022/02456-0) and a Productivity Fellowship from the Brazilian National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq 306060/2022-1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mostafa, Y.; Alrumman, S.; Alamri, S.; Hashem, M.; Al-izran, K.; Alfaifi, M.; Elbehairi, S.E.; Taha, T. Enhanced production of glutaminase-free L-asparaginase by marine Bacillus velezensis and cytotoxic activity against breast cancer cell lines. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2019, 42, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakambari, G.; Ashokkumar, B.; Varalakshmi, P. L-Asparaginase – A promising biocatalyst for industrial and clinical applications. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2019, 17, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.F.; Almeida, M.R.; Paiva, G.B. De; Pedrolli, D.B.; Neves, M.C.; Freire, M.G.; Tavares, A.P.M. A flow-through strategy using supported ionic liquids for L-asparaginase purification. Separation and Purification Technology 315 2023, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselin, B.; Rizzari, C. Asparaginase pharmacokinetics and implications of therapeutic drug monitoring. Leuk Lymphoma 2015, 56, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhankhar, R.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, S.; Kapoor, R.K.; Gulati, P. Microbial enzymes for deprivation of amino acid metabolism in malignant cells: Biological strategy for cancer treatment. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugaprakash, M.; Jayashree, C.; Vinothkumar, V.; Senthilkumar, S.N.S.; Siddiqui, S.; Rawat, V.; Arshad, M. Biochemical characterization and antitumor activity of three phase partitioned L-asparaginase from Capsicum annuum L. Sep Purif Technol 2015, 142, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, W.A.F.; Schultz, L.; Breyer, C.A.; de Oliveira, A.L.P.; Tairum, C.A.; Fernandes, G.C.; Toyama, M.H.; Pessoa-Jr, A.; Monteiro, G.; de Oliveira, M.A. Functional and structural evaluation of the antileukaemic enzyme L-asparaginase II expressed at low temperature by different Escherichia coli strains. Biotechnol Lett 2020, 42, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenmozhi, C.; Sankar, R.; Karuppiah, V.; Sampathkumar, P. L-Asparaginase production by mangrove derived Bacillus cereus MAB5: Optimization by response surface methodology. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2011, 4, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, N.; Priyanka; Singh, J.; Singh, R.P. A potential type-II L-asparaginase from marine isolate Bacillus australimaris NJB19: Statistical optimization, in silico analysis and structural modeling. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 174, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiao, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, M.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Enhanced extracellular production of L-asparaginase from Bacillus subtilis 168 by B. subtilis WB600 through a combined strategy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2017, 101, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.F.; Hamdan, S.; Mahadi, N.M.; Murad, A.M.A.; Rabu, A.; Bakar, F.D.A.; Klappa, P.; Illias, R.M. A mutant L-asparaginase II signal peptide improves the secretion of recombinant cyclodextrin glucanotransferase and the viability of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett 2011, 33, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, Y.; Yano, S.; Thongsanit, J.; Takagi, K.; Yoshimune, K.; Wakayama, M. Expression in Escherichia coli of a gene encoding type II L-asparaginase from Bacillus subtilis, and characterization of its unique properties. Ann Microbiol 2011, 61, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, W.A.F.; Schultz, L.; Breyer, C.A.; de Oliveira, A.L.P.; Tairum, C.A.; Fernandes, G.C.; Toyama, M.H.; Pessoa-Jr, A.; Monteiro, G.; de Oliveira, M.A. Functional and structural evaluation of the antileukaemic enzyme L-asparaginase II expressed at low temperature by different Escherichia coli strains. Biotechnol Lett 2020, 42, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, T.; Jiao, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Chi, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xu, D.; Lu, F. Structures of L-asparaginase from Bacillus licheniformis reveal an essential residue for its substrate stereoselectivity. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolfaghar, M.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Khajeh, K.; Babavalian, H.; Tebyanian, H. Isolation and screening of extracellular anticancer enzymes from halophilic and halotolerant bacteria from different saline environments in iran. Mol Biol Rep 2019, 46, 3275–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-toledo, S.; Tapia-Bañez, Y.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Esquerre-Hullpa, C.; Zavaleta, A.I. Caracterización bioinformática y producción de L-asparaginasa de Bacillus sp. M62 aislado de las salinas de Maras, Cusco, Perú. Rev Peru Biol 2023, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamian, S.; Gholamian, S.; Nazemi, A.; Nargesi, M. Isolation and characterization of a novel Bacillus sp. strain that produces L-asparaginase, an antileukemic drug. Asian Journal of Biological 2013, 6, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, S.H.; Wray, L. V. Bacillus subtilis 168 contains two differentially regulated genes encoding L-asparaginase. J Bacteriol 2002, 184, 2148–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R. V.; Kumar, V.; Rajendran, V.; Saran, S.; Ghosh, P.C.; Saxena, R.K. Purification and characterization of a novel and robust L-asparaginase having low-glutaminase activity from Bacillus licheniformis: In vitro evaluation of anti-cancerous properties. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.; Flores-Santos, J.C.; Flores-Fernández, C.N.; Saavedra, S.; Santos, J.H.P.M.; Pessoa-Júnior, A.; Lienqueo, M.E.; Bayro, M.J.; Zavaleta, A.I. A novel L-asparaginase from Enterobacter sp. strain M55 from Maras salterns in Peru. Chem Biochem Eng Q 2022, 36, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrin, S.; Parrott, C.L.; Luborsky, S.W. Substrate binding and intersubunit interactions in L-asparaginase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1974, 249, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimzadeh, M.; Poodat, M.; Javadpour, S.; Qeshmi, F.I.; Shamsipour, F. Purification, characterization and comparison between two new L-asparaginases from PG03 and PG04. Open Biochem J 2016, 10, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant’Anna, V.; Cladera-Olivera, F.; Brandelli, A. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of thermal inactivation of the antimicrobial peptide P34 in milk. Food Chem 2012, 130, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; et al. AlphaFold protein structure database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjalsma, H.; Bolhuis, A.; Jongbloed, J.D.H.; Bron, S.; van Dijl, J.M. Signal peptide-dependent protein transport in Bacillus subtilis: A genome-based survey of the secretome. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2000, 64, 515–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Kim, M. Purification and characterization of thermostable L-asparaginase from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MKSE in korean soybean paste. Lwt 2019, 109, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, J.; Tjalsma, H.; Rivolta, C.; Hederstedt, L. Subunit II of Bacillus subtilis Cytochrome C oxidase is a lipoprotein. J Bacteriol 1999, 181, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesmeyanova, M.A.; Karamyshev, A.L.; Karamysheva, Z.N.; Kalinin, A.E.; Ksenzenko, V.N.; Kajava, A. V. Positively charged lysine at the N-terminus of the signal peptide of the Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase provides the secretion efficiency and is involved in the interaction with anionic phospholipids. FEBS Lett 1997, 403, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Du, G. Gene cloning and expression of the L-asparaginase from Bacillus cereus BDRD-ST26 in Bacillus subtilis WB600. J Biosci Bioeng 2019, 127, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falak, S.; Sajed, M.; Rashid, N. Strategies to enhance soluble production of heterologous proteins in Escherichia coli. Biologia (Bratisl) 2022, 77, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.L.; Poddar, S.; Iftekhar, S.; Suh, K.; Woolfork, A.G.; Ovbude, S.; Pekarek, A.; Walters, M.; Lott, S.; Hage, D.S. Affinity chromatography: A review of trends and developments over the past 50 Years. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2020, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, N.; El-Ahwany, A.; Ataya, F.S.; Saeed, H. Bacillus sonorensis L. asparaginase: Cloning, expression in E. coli and characterization. Protein Journal 2020, 39, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, J.; Jiao, L.; Zhong, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lu, F. Improvement of the activity of L-asparaginase I improvement of the catalytic activity of L-asparaginase I from Bacillus megaterium H-1 by in vitro directed evolution. J Biosci Bioeng 2019, 128, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, S.; Mahajan, R.; Prasad, J.P.; Sahoo, D.K.; Mihooliya, K.N.; Dhar, M.S.; Sharma, G. A comprehensive review on microbial L-asparaginase: Bioprocessing, characterization, and industrial applications. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2020, 67, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubkowski, J.; Wlodawer, A. Structural and biochemical properties of L-asparaginase. FEBS Journal 2021, 288, 4183–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapura, P.R.; Belur, P.D.; Subramanya, S. A critical review on properties and applications of microbial L-asparaginases. Crit Rev Microbiol 2016, 42, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, B.; Mu, W. Recent research progress on microbial L-asparaginases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 99, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Xu, M.; He, B.; Rao, Z. Cloning, expression, and characterization of L-asparaginase from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis B11-06. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 9428–9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi, G.; Bhimani, K.; Vaishnav, D.; Oza, T.; Dave, G.; Kunjadia, P. Mitigation of acrylamide by L-asparaginase from Bacillus subtilis KDPS1 and analysis of degradation products by HPLC and HPTLC. Springerplus 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, A. V; Mari, D.S. Screening and identification of asparaginase and glutaminase producing halophilic bacteria from natural saline habitats. International Journal on Recent Advancement in Biotechnology & Nanotechnology 2020, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Venkata Dasu, V.; Pakshirajan, K. Purification and characterization of glutaminase-free L-asparaginase from Pectobacterium carotovorum MTCC 1428. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warangkar, S.C.; Khobragade, C.N. Purification, characterization, and effect of thiol compounds on activity of the Erwinia carotovora L-asparaginase. Enzyme Res 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, V.; Ramalingam, A.; Sumantha, A.; Shankaranaya, R. Production, purification and characterization of extracellular L-asparaginase from a soil isolate of Bacillus sp. Afr J Microbiol Res 2010, 4, 1862–1867. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).