In case of the

pulsed blinding light, very strong laser pulses keep detectors thermally blinded. In the original DBA described in Refs. [

4,

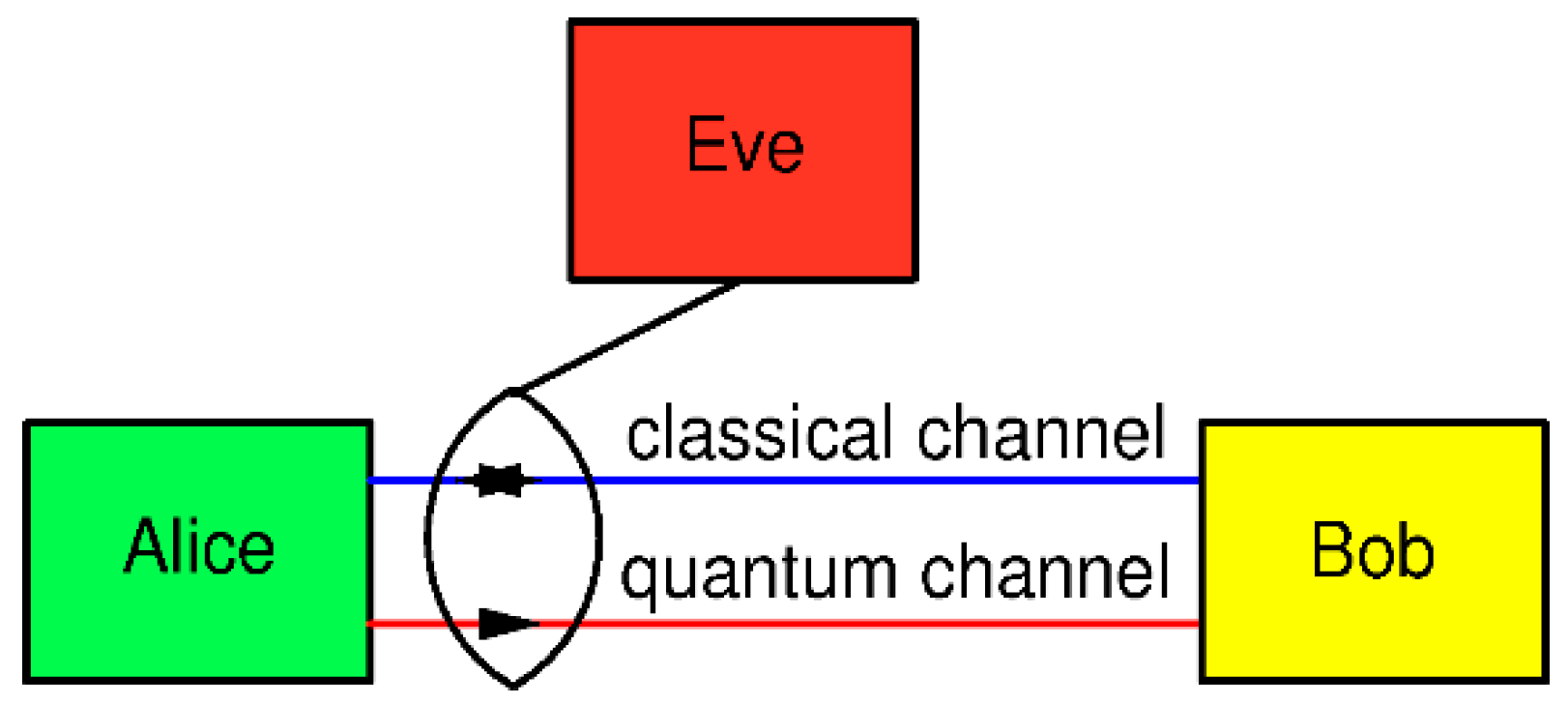

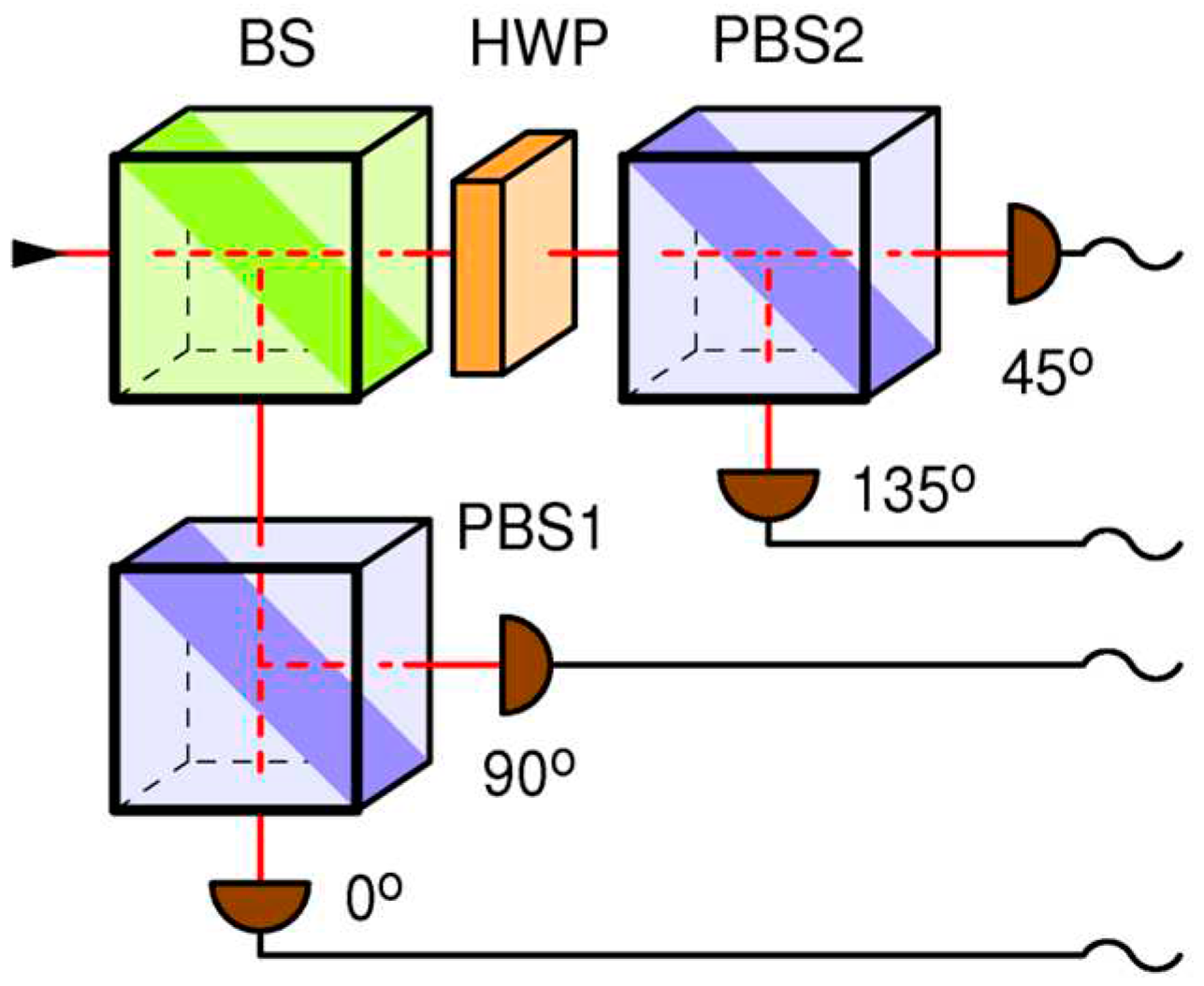

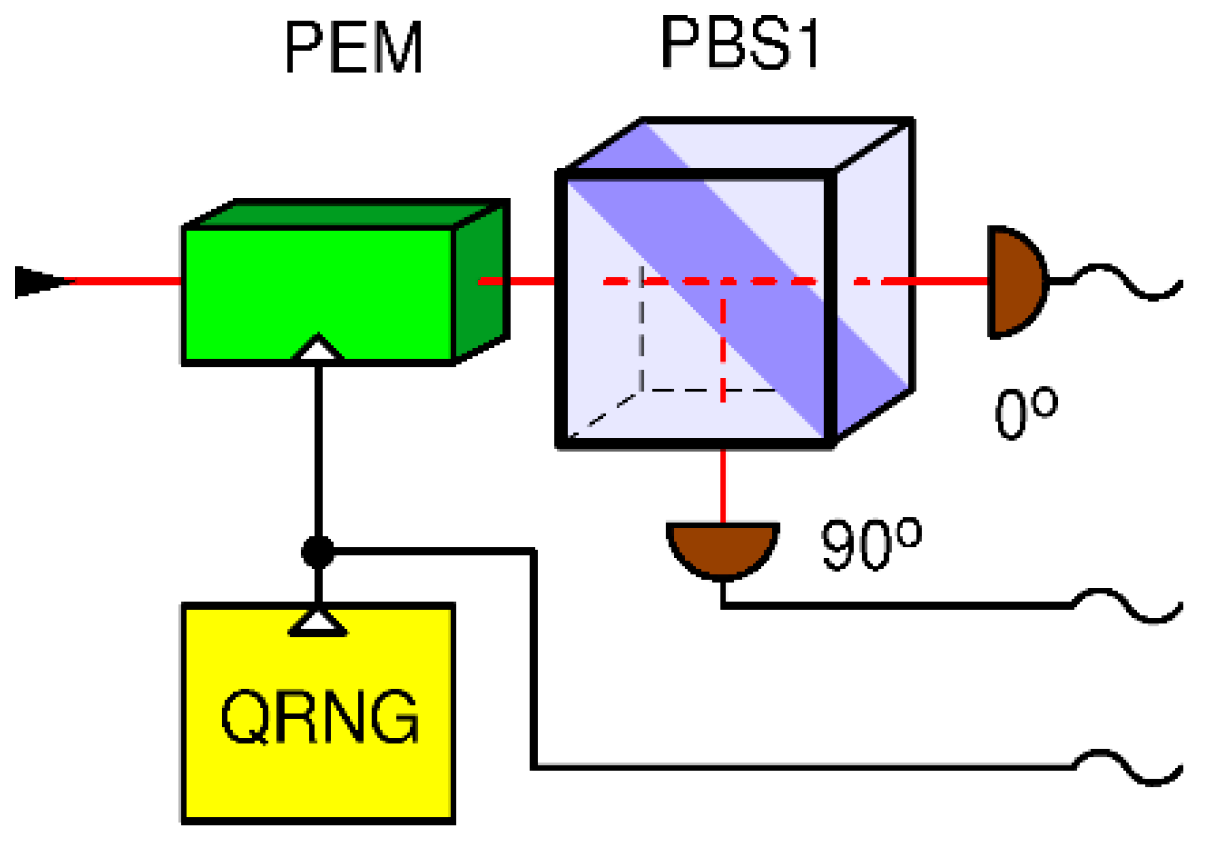

7], performed on the setup shown in

Figure 2, it is noted that such strong pulses will cause simultaneous detection in all affected detectors. Because of that, Eve keeps the blinding pulses outside of gate so that they do not generate extra in-gate coincidences, and shoots them frequent enough to keep all the detectors blinded at all times. However, when this attack is applied to the setup in

Figure 4, Eve is not sure which base gets blinded, because bases are selected at random with probability 1/2, therefore she needs to rise the blinding rate by at least twice. Even so, because of the binomial statistics of base selection, occasionally a base might get out of blinding and generate an extra in-gate coincidence when hit by a fake state. While details of this behavior would have to be investigated further, it is safe to assume that, in her best scenario, Eve will be able to achieve blinding and retrieve the full key, albeit at the expense of 6 dB loss caused merely by the random base choice. The un-avoidable price paid for the pulsed blinding is causing the out-of-gate coincidences between two detectors in the active (selected) base.

5.1. Attack Analysis

It would naively seem that Eve can successfully eavesdrop on the receiver in

Figure 4 using blinding techniques. However, this particular setup enables yet another lever arm available for Alice and Bob to defeat Eve, which relies on monitoring in-gate and out-of-gate coincidences.

Let us first discuss a regular quantum communication with single qubits, in which Bob knows the arrival time of Alice's qubit and opens a short detection time window

, named "gate", around it, to detect the qubit. In order to have a non-zero secret key rate of the BB84 protocol, the bit error rate of the first phase must be

% [

27]. The dark count occurrence probability during the gate for a single detector is:

where

is the dark count rate (DCR) of the detector and

is duration of the gate. The right-hand approximation is valid for

, which is often the case. Bob can confidently determine the dark count rates for all four detectors by disconnecting the receiver from the quantum channel and performing measurements in the dark. To simplify calculation, we will henceforth assume equal DCR for all detectors. DCR-caused "accidental" coincident detection between a pair of detectors belonging to the same base is a Poissonian random event. Its probability during the gate-open period

, or "in gate" probability, is given by:

When receiving qubits, the coincidence rate between two detectors forming a base, is described by the Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) effect, which characterizes the probability of simultaneous photon detection at the two outputs of a beamsplitter [

28]. By considering a coherent input state qubit, emitted from Alice with an average photon number

within a gate-open period

, the per-gate-coincidence-probability measured by Bob in any of its two bases is given by [

29]:

where

is Bob's system quantum efficiency, which includes effects of finite detector quantum efficiency, optics imperfections and other losses in Bob, while quantum channel efficiency

is a fraction of qubits that survive through the quantum channel connecting Alice and Bob. The right-hand approximation is valid for

, which holds true in a practical QKD where typically

and

while loses can be anywhere between a few dB and few tens of dB. The overall factor

equals probability that the qubit is in a "wrong" base. In the case that the base is "right" for the given qubit, there will be no coincidence in principle because photon will end up in only one detector. Here we neglect a possible imperfection in Bob's polarizers, which in may allow for a small probability of coincidence (typically less than 0.01). The coincidence probability is composed of both the accidental coincidences and qubit-related coincidences. Both being Poisson random processes, the total in-gate coincidence probability

, for the regular BB84 protocol in setup in

Figure 4, is given by:

As an example, assuming the following realistic values: gate time ns, the dark count rate cps, average photon number in a qubit , Bob's system quantum efficiency , and the quantum channel transfer efficiency (-8 dB), one arrives to .

Using the same approach, we can calculate out-of-gate coincidence rate for DCR:

The qubits do not fall outside of gate and therefore do not cause out-of-gate coincidences:

The total out-of-gate coincidence probability, for the regular BB84 protocol in setup in

Figure 4, equals:

where

is rate at which Alice emits qubits. Using the same set of communication parameters as in the previous example and

MHz, one arrives to

.

Our defense strategy relies on the fact that both in-gate and out-of-gate coincidence probabilities, described by Equation (5) and Equation (8), are dramatically enhanced under a strong-light attack, as will be shown below.

The case of the CW DBA. Let

be the number of photons arriving during a gate onto a detector. Then the probability

that the detector, having a quantum efficiency

, will detect at least once is given by [

29]:a = 1,

or even closer to unity in case of superlinear detectors [

6]. Considering a coherent blinding light, with an average photon number

arriving on Bob during a gate, the overall coincidence probability, according to Equation (9), is:

Assuming an attack using as few as photons incident on Bob per gate, and assuming that , then the coincidence probability is about and it would quickly approach theoretical maximum of for a larger . This is about 6 orders of magnitude higher than in-gate coincidence probability of the regular BB84 protocol , as calculated above, even though the incident optical power considered in this example is much smaller than required for an actual detector blinding attack.

In the case of the pulsed DBA, which operates upon the principle of thermal blinding with strong out-of-gate pulses, such an attack will not enlarge in-gate coincidences between detectors in the same base. However, as explained above, each blinding light pulse will create one out-of-gate coincident pair of detections in two detectors belonging to the base which is currently selected by the QRNG. The coincidence probability for either detection base, per gate, is given by:

where

is a minimum required blinding pulse rate, being 70 kHz according to [

4] and, as explained above, this needs to be at least doubled by Eve because of the active base selection in this setup. As justified above, we do not add dark counts to that rate.

Assuming kHz and other parameters the same as in the previous examples, we obtain . On the other hand, the coincidence probability of the undisturbed QKD , as calculated above, is more than 6 orders of magnitude smaller.

This demonstrates that, both in the in-gate and in the out-of-gate DBA, the corresponding coincidence rates will be strongly enhanced with respect to the undisturbed BB84, when using the setup shown in

Figure 4. This fact is the basis for our defense strategy, which should work for any type of strong light attack, DBA included.

5.2. Proposed Defense Strategy against Strong-Light Attacks

To defend from strong light attacks, we focus on two pairs of equations: on one hand Equation (5) and Equation (8) which model in- and out- of-gate coincidence probabilities during execution of a pristine BB84 QKD protocol, and on the other hand Equation (10) and Equation (11) which model the same coincidence probabilities, but under a strong-light attack. The huge rise in coincidence probabilities under a strong light attack, even for injected light level far less than required to mount an actual blinding attack, present a robust figure of merit for discerning undisturbed quantum communication from an attack condition. In modern QKD systems, output of each detector is connected to a dedicated channel of a time-tagger and time stamps are recorded, thus the above probabilities can be evaluated by a simple data analysis.

The defense strategy, valid for the receiver in

Figure 4, is outlined below.

In the first step, one collects information about Bob's system quantum efficiency , dark count rates of all four detectors, where index marks the detector dedicated for measuring of the k-th polarization (namely linear polarization of angle ), and estimate their respective statistical uncertainties . As before, in order to simplify treatment, but with an obvious extension to the general case, we henceforth assume that all detectors exhibit the same dark count parameters: and . All these parameters may be known in advance. Alternatively, one may disconnect Bob from the quantum channel and perform an appropriate set of measurements (calibration) to obtain them. We also assume that parameters , , are known or negotiated before the start of QKD protocol. While Eve may know all of these parameters (by Kerchoff's principle), she may not influence them.

In the second step, during the quantum communication session (namely the first phase of BB84), one measures Bob's in-gate and out-of-gate coincidence probabilities related to reception of qubits, namely

and

. For example,

is evaluated as the sum of rates of coincidences between pairs of detectors (0, 2) and (1, 3) that happen only during gates, divided by the rate of gates

. Similarly is evaluated

except that said coincidences are now counted out of gates. Furthermore, if the quantum channel transmissivity

is not known/calibrated beforehand, it should be estimated. To that end, one measures the total rate of detections of all four detectors within coincidence windows,

and estimates its variance

. The qubit reception probability is then equal to:

According to Equation (10), for undisturbed BB84, it should be equal to:

Solving for

gives:

Note that Eve does not control nor , but she can manipulate apparent to a certain extent. On one hand, she could make lower by randomly omitting qubits from Alice, but that would not enable her to increase her information on the resulting key, while the key would only get shorter for all three parties. On top of that, communication-induced coincidence probabilities would became smaller, thus ratio of probability of blinding-induced coincidences would rise in comparison to ones from communication. That would make Eve's attack more easily discoverable. On the other hand, she could make higher, by removing a (part of) loss she induced beforehand, as explained before, if any. In that case, she must "invent" new qubits for Bob that would cause rising of BER, causing Alice and Bob to remove this extra information in the privacy amplification so Eve will not gain any new knowledge on the key nor would the effective key length change. By doing so, her discoverability would get smaller by a factor she enlarged , but that is not a significant gain, as will be shown below.

Before going to the final step, one needs to estimate the statistical uncertainty of

. To that end we assume that predominant uncertainty of

comes from statistical uncertainties of

and dark count rates. We further assume that qubit detection and dark counts are Poissonian events. It is then straightforward to show, using standard statistical theory of propagation of uncertainty, that its variance is given by:

At the end of this step, following parameters, pertaining to the hardware and the quantum communication, are known: , , , , , , , , , and . These are input to the final step.

In the third and final step, one calculates upper limits on probabilities of in- and out- of gate coincidence probabilities for undisturbed QKD communication ( and , and compares them to the directly measured probabilities of in- and out- of gate coincidence ( and ) in order to detect whether the QKD system is under attack, at a desired (arbitrary) level of confidence.

The in- and out- of gate undisturbed coincidence probabilities

and

can be estimated using Equations (5) and (8) respectively and parameters available from the previous step. Their respective variances are:

Next, without any assumption on the statistical distribution(s) governing their values, one can find the respective upper limits on those probabilities, using Chebyshev's inequality [

30]:

Having in mind that all variables in the above equation are positive, an upper limit on

is given by:

which can be interpreted as:

where

is an arbitrarily chosen probability (confidence level) that inequality

holds. Equivalently we obtain:

Finally, we define the following security criterion. If both inequalities below hold, for coincidence probabilities measured for a QKD session:

one concludes that the QKD session is not under a DBA with confidentiality level of

. On the other hand, if any of the two inequalities fail, the session is insecure and should be aborted.

Let us now work out one numerical example. We assume the same realistic parameters as above for easier comparison, namely: , MHz, ns, , kcps, on top of that cps, total in-gate detection rate cps, and kcps. From Equarions (12), (14) and (15) we obtain: , and . Then, Equarions (16) and (17) yield: and . Finally, even requiring a very high confidence level of 99.9999% , Eqs.(20) and (21) give a rather small/strict threshold values on coincidence probabilities: and .

The criterion in Equation (22) tells us that as soon as

or

one concludes, with 99.9999% confidence, that the session has been compromised. To appreciate the discerning capability of this defense, we should remember that for the DBA attacks described in the previous section, using the same values of communication parameters, we got

and

which is several orders of magnitude higher than their respective thresholds

and

. We conclude that it is very unlikely that any multi-photon attack strategy would pass the criterion Equation (22) in conjunction with the setup of

Figure 4.