2. Results and Discussion

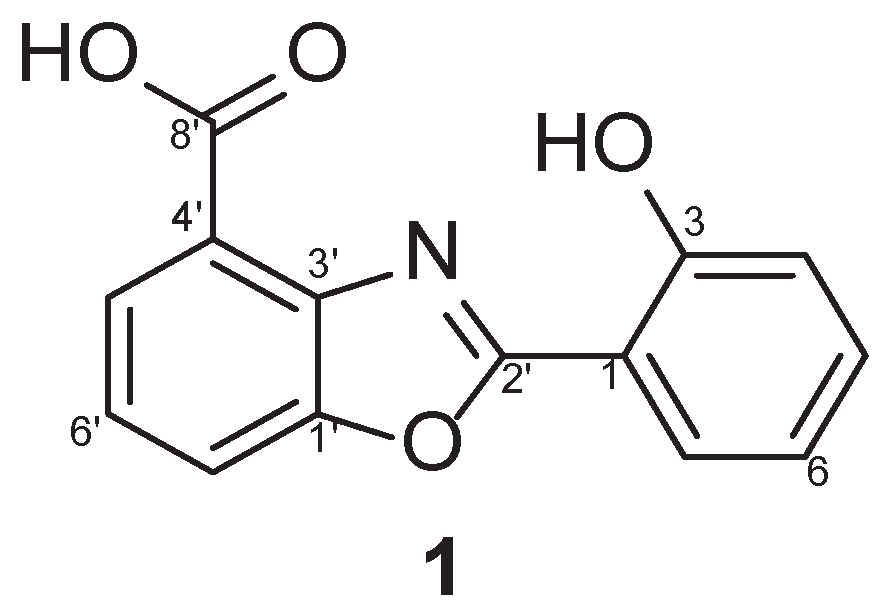

Identification of Compound 1. Compound 1 was isolated as a white powder with

a pseudomolecular ion peak at the

m/z = 256.23 [M+H]

+ in LRMS spectroscopic data. The

1H NMR spectrum of compound

1 displayed seven aromatic protons at

δH 8.09 (d,

J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-7′), 8.02 (d,

J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-5′), 7.81 (d,

J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H-6), 7.45 (t,

J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-6′), 7.44 (t,

J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-4), 7.13 (d,

J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, H-3), and 7.02 (t,

J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-5). Moreover, the

13C NMR spectrum of

1 displayed seven quaternary carbons at

δC 164.1 (C-8′), 158.9 (C-2′), 158.8 (C-2), 149.6 (C-1′), 140.1 (C-3′), 120.5 (C-4′) and 110.0 (C-1) and seven methines at

δC 134.5 (C-6′), 128.1 (C-7′), 127.7 (C-5′), 124.9 (C-4), 119.8 (C-5), 119.7 (C-3), 115.5 (C-6). Finally, compound

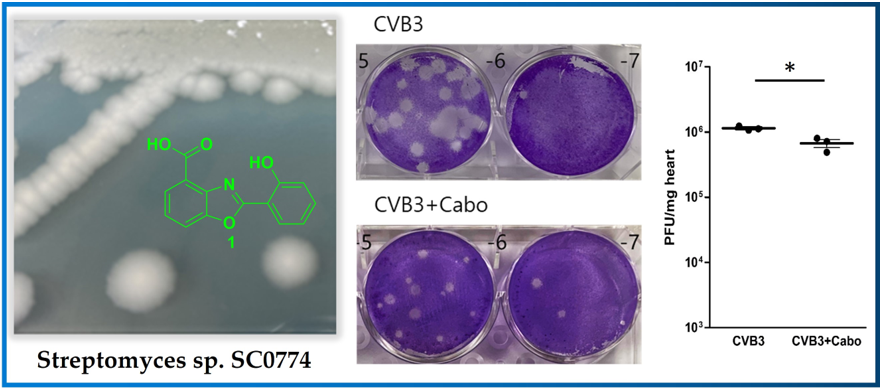

1 was identified as caboxamycin (

Figure 1A) based on a comparison of its NMR data to the literature [

14]. Caboxamycin (

1) was first isolated from the extracts of the marine

Streptomyces sp. NTK 937. Compound

1 possessed the benzoxazole scaffold as the core center as shown in

Figure 1 and was reported to exhibited antibiotic activity against Gram-positive bacteria

Bacillus subtilis and

Staphylococcus lentus, as well as the yeast

Candida glabrata [

12,

13]. In addition,

1 also possessed moderate cytotoxic effect against gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS), hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep G2) and breast carcinoma cells (MCF7).

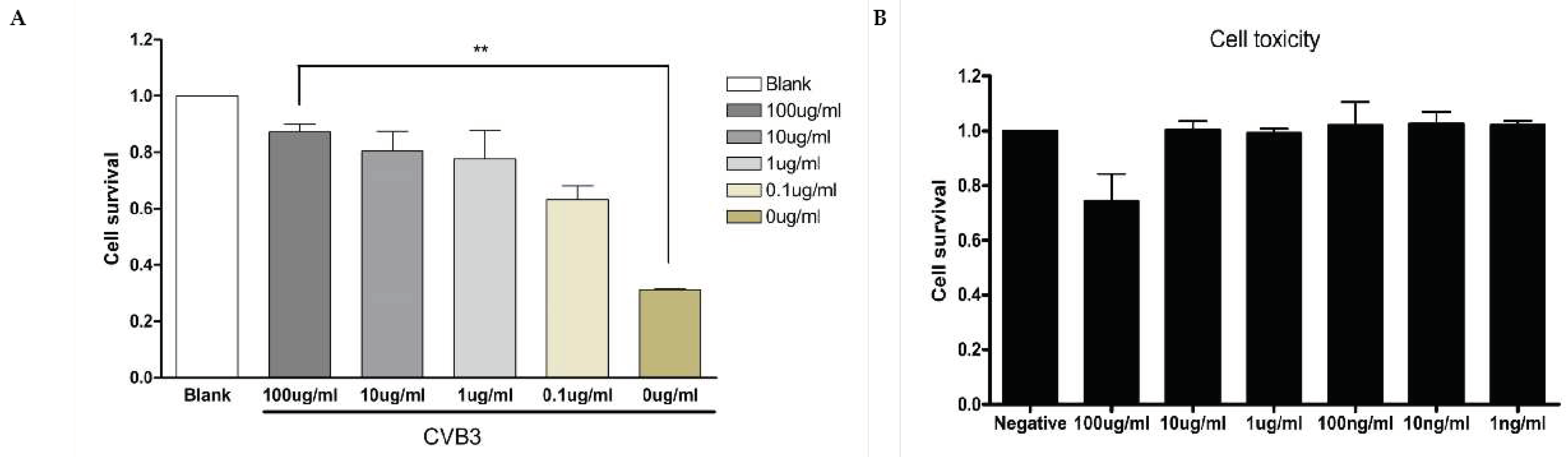

Caboxamycin Strongly Inhibit Coxsackievirus B3 Replication. The antiviral effect of caboxamycin (

1) was observed in HeLa cells with CVB3 infection. CVB3 was infected with 100 to 0.1 ug/ml serial diluted

1 for 16 hours, and then the cell survival was measured by CCK-8 kit. HeLa cell survival was strongly preserved by

1 treatment compared to untreated (

Figure 2A). In addition,

1 showed very weak cell toxicity in HeLa cells. But 100 μg/ml of

1 showed about 20% cell death (

Figure 2B). High dose of chemical has some cytotoxicity, so it is not a serious problem to apply the development of a new antiviral component based on caboxamycin.

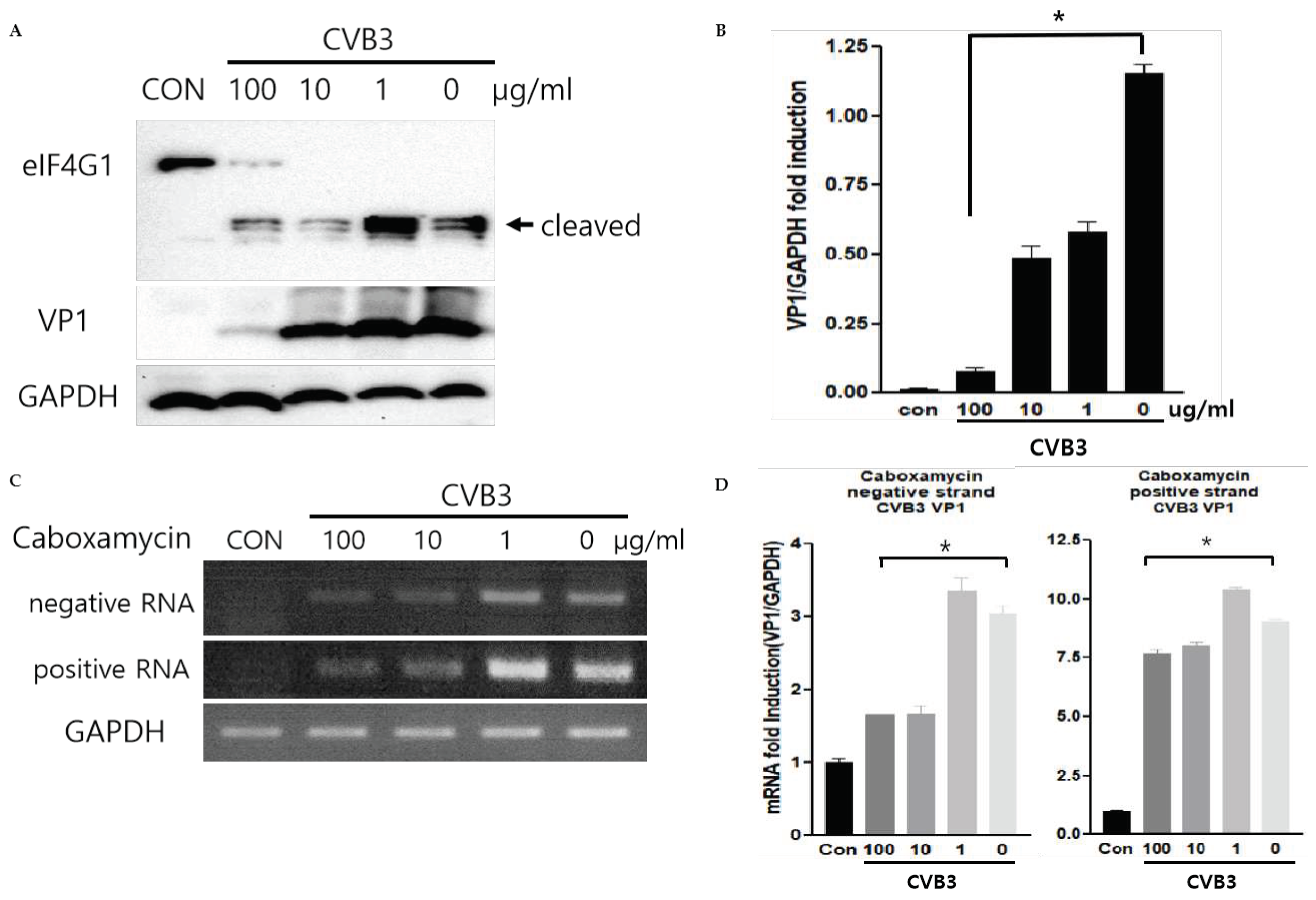

The CVB3 replication was observed by western blot analysis and quantitative RT-PCR of viral capsid protein (VP1). During replication, CVB3 produces protease 2A protein to cleave their polyprotein to generate viral particles. This protease 2A breaks down the host translation initiation factor eIF4G1. Caboxamycin (

1) treatment dramatically suppressed eIFG1 cleavage and VP1 viral capsid protein production (

Figure 3A and B). Virus replication is initiated from RNA genome amplification. Especially, negative-strand RNA amplification is the major step of CVB3 replication. 100, 10 ug/ml of

1 treatment inhibited positive and negative-strand RNA genome amplification (

Figure 3C and D). These results showed that

1 has a strong antiviral effect on both genome amplification and viral protein production.

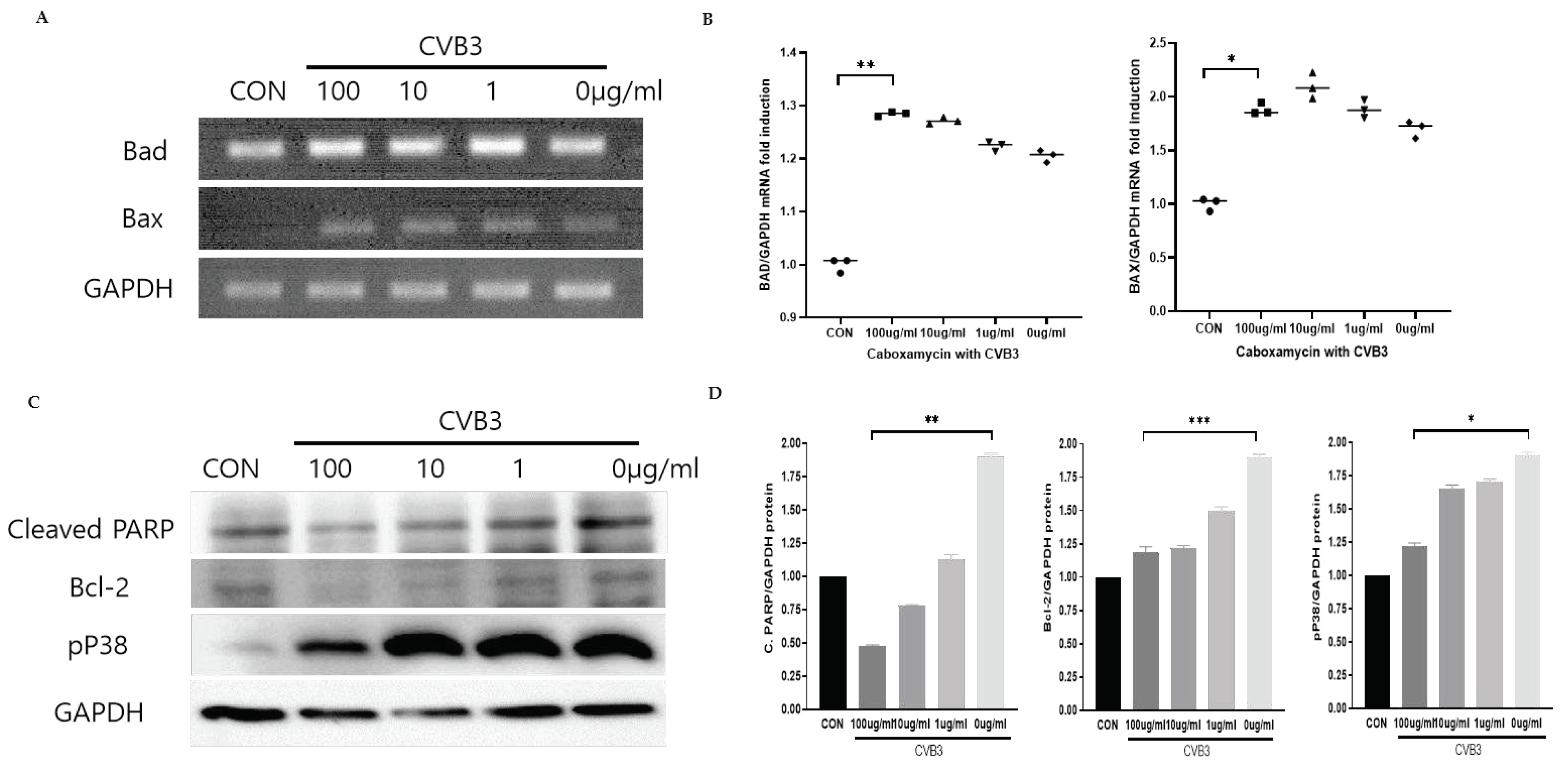

Caboxamycin treatment inhibited apoptosis and improved the survival cell signaling pathway. Virus infection activates the apoptosis pathway and kills the cells. This pathway was regulated by activating Bcl-2 family proteins such as pro-apoptotic BAD (Bcl-2 associated Agonist of cell death), and BAX (Bcl-2 Antagonist X) activation. We tested the apoptosis inhibition by treatment of

1 in CVB3-infected HeLa cells. However, pro-apoptotic BAD and BAX transcription levels were dramatically increased by CVB3 infection but were not affected by

1 treatment. Moreover, a high dose of

1 enhanced apoptosis gene transcription (

Figure 4A and B). This apoptosis activation may be beneficial for antiviral effects in CVB3-infected cells. In contrast, the PARP (Poly ADP-ribose polymerase) cleavage, Bcl-2, and p38 phosphorylation were significantly decreased by 100 ug/ml treatment of

1 (

Figure 4C and D). These results implied that apoptotic cell signaling was dramatically inhibited and virus-infected cell survival improved. The inhibition of CVB3 replication can reduce apoptotic activity, but BAX and BAD mRNA expression level was not decreased from the

1 treatment.

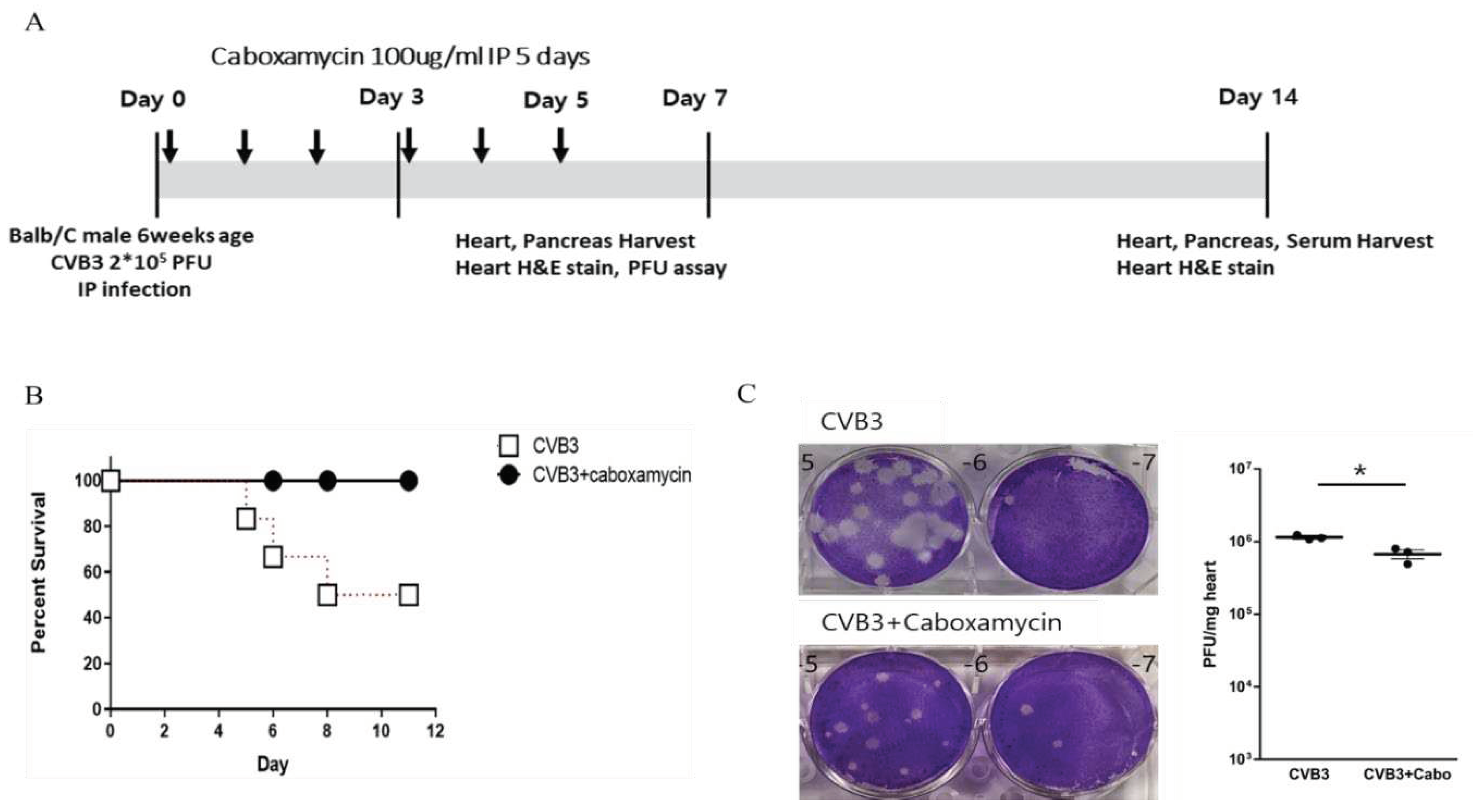

Caboxamycin reduced cardiac inflammation and virus replication in the CVB3-induced myocarditis mice model. Caboxamycin was administered in the CVB3-induced myocarditis mice model. The animal experiment was performed following the experiment design (

Figure 5A). The six-weeks-old male mice (about 20 g in weight) were infected intraperitoneally with 2 x 10

5 PFU of CVB3 (CVB3) or with caboxamycin (CVB3+Cabo). The mice survival rate was preserved in the caboxamycin-treated group compared to the untreated group (CVB3 Vs CVB3+Cabo; 45 Vs 100%, p<0.08). Heart virus titer was measured by PFU assay. The overall result showed that heart virus proliferation was significantly decreased in CVB3+cabo group compared to CVB3 group (CVB3 Vs CVB3+Cabo: 1143000±87369 Vs 670233±161678, p<0.05) (

Figure 5B, and C).

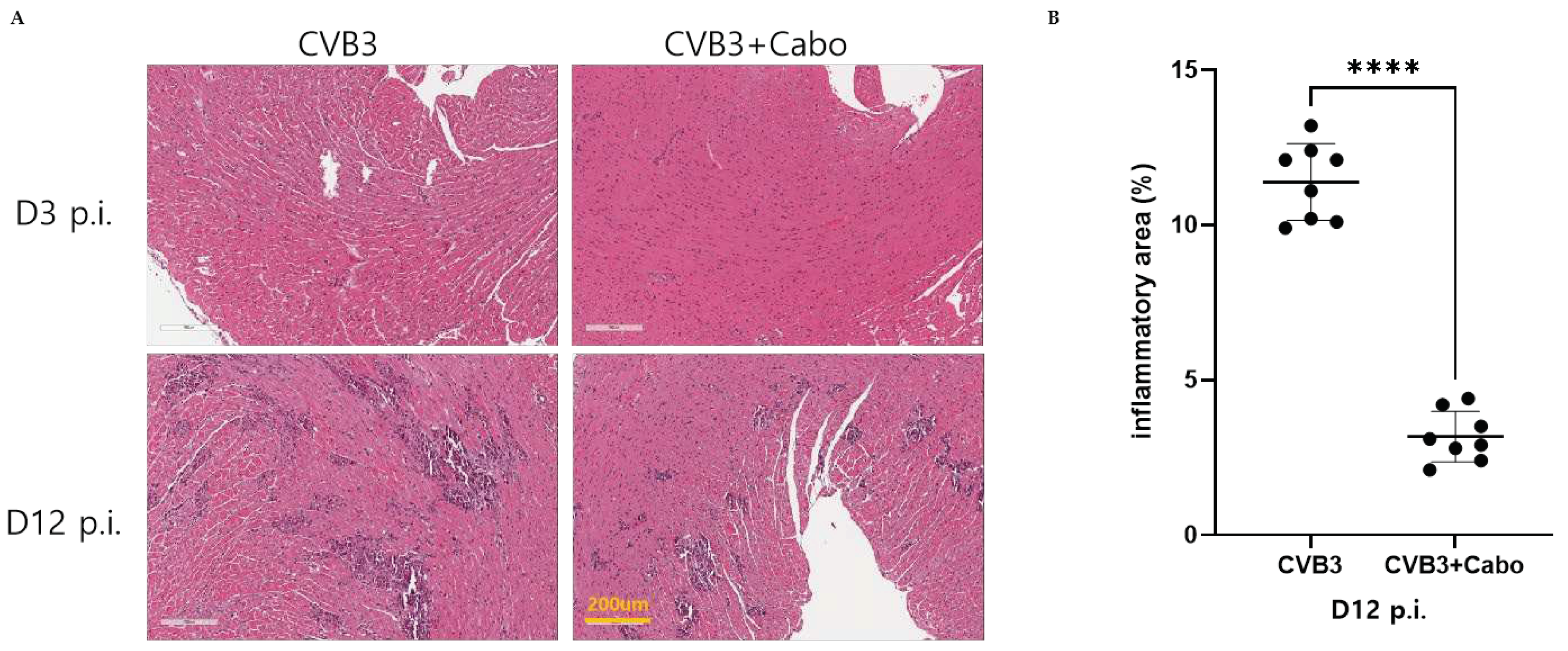

Heart inflammation was observed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains of day 3 and 12 post-infection mice hearts. NIH-ImageJ software quantified the focal inflammation area in two or three fields of each heart. The inflammation percent area was dramatically decreased by caboxamycin treatment compared to CVB3 group (

Figure 6A, and B). CVB3 infection activate innate immunity and enhance inflammatory cell infiltrate on the virus infected damaged myocyte area [

14,

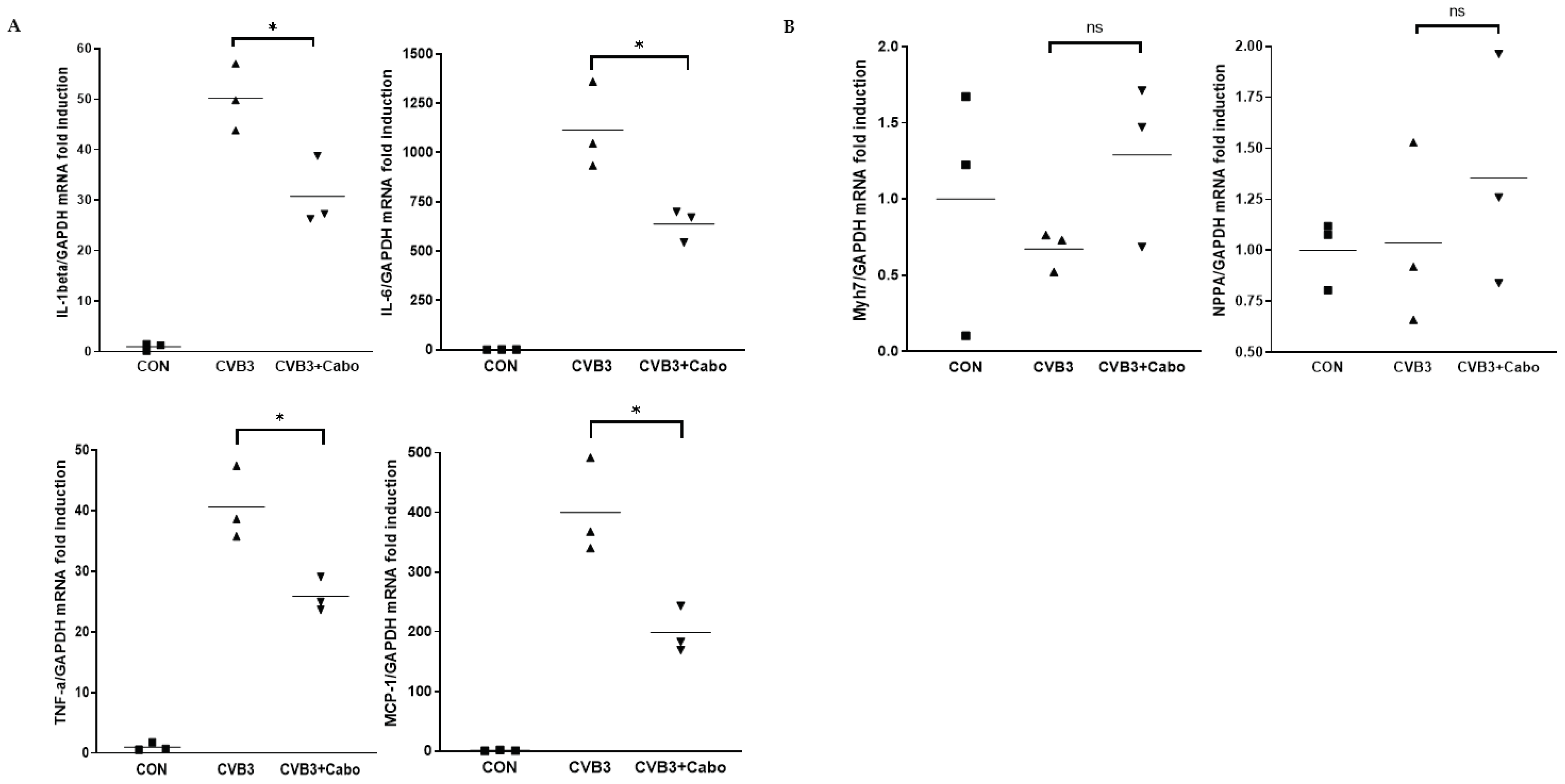

15]. Heart inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression was observed by quantitative RT-PCR using day 3 pi mice heart with caboxamycin treatment (CVB3+Cabo). IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha, and MCP-1 were significantly decreased by caboxamycin treated mice heart compared to CVB3-infected mice heart (

Figure 7A). In addition, myocardium damage marker Myh7 and NPPA were little changed by caboxamycin treatment, respectively. However, it was not significantly different between two groups (

Figure 7B). These results demonstrated that the inhibition of virus replication by caboxamycin treatment was effective to reduce inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine production in CVB3-infected mice heart. However, the myocardium damage still not occurred at the early stage of CVB3 infection.

Viral myocarditis is an inflammatory process that causes damage to cardiac muscle cells [

16]. The inhibitory effect of caboxamycin in CVB3 infection was tested. The result described that treatment with caboxamycin significantly suppressed CVB3 infection and cell mortality in HeLa cells. In addition, caboxamycin reduced apoptosis and cell death to HeLa cells by inhibiting virus replication and capsid protein (VP1) production. The cleavage of eIF4G1, a transcription initiation factor cleaved by viral protease 2A [

17], was significantly decreased by caboxamycin treatment. CVB3 is a positive single-strand RNA virus, and producing a negative-strand RNA is essential for viral genome amplification [

18]. caboxamycin treatment strongly inhibited negative strand RNA amplification of CVB3. Enterovirus replication occurs by activating ERK, a cell signaling molecule [

19]. MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinases) p38 activity was significantly suppressed following the drug concentration, and the cells remained viable. However, high concentration of caboxamycin has a cytotoxicity, therefore we should carefully define this reason by further experiment.

3. Materials and Methods

General Experimental Procedures. Low-resolution LC/MS measurements were performed using the Agilent Technologies 1260 quadrupole mass-spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Waters Micromass-ZQ 2000 MS system (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA) using a reversed-phase column (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 50 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 100 Å) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at the National Research Facilities and Equipment Center (NanoBioEnergy Materials Center) at Ewha Womans University [

20].

1H and 2D NMR spectra were recorded at 400 MHz in CDCl

3 using a solvent signal as internal standard on Varian Inova spectrometers (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

13C NMR spectrum was acquired at 100 MHz on the Varian Inova spectrometer. Open-column chromatography was performed on C-18 resin (40-63 μm, ZEO prep 90) with a gradient solvent of water (H

2O) and methanol (MeOH). The fractions obtained from open column chromatography were subsequently purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 100 Å, 250 nm × 10 mm, 5 μm column with a mixture of acetonitrile (CH

3CN) and H

2O at a flow rate of 2.0 mL min

−1.

Collection and Phylogenetic Analysis of Strain SC0774. The marine-derived actinomycete strain SC0774 was isolated from marine sediment sample collected in Antarctic. The strain SC0774 was identified as Streptomyces sp. with 100% similarity to that of Streptomyces griseolus, based on the NCBI blast analysis of the partial 16S rRNA. The gene sequence data are available from Genebank (deposit MW132412.1).

Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation. The strain SC0774 was cultured in 80 L of 2.5 L Ultra Yield Flasks, with each flask containing 1 L of SYP SW medium (10 g/L of Soluble starch, 2 g/L of yeast extract, 4 g/L of peptone, 139 g/L of sea salt in 1 L of distilled water) at 27°C with shaking at 120 rpm for 7 days. After a culture period of 7 days, the culture medium was extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc), yielding a total of 80 L of extract, which was concentrated in a rotary vacuum evaporator to yield 4.0 g of crude extract. The crude extract was fractionated into 8 fractions using reverse-phase C18 flash chromatography with a stepwise gradient elution of 80% of H2O in MeOH to 100% MeOH. The sixth fraction, 80% MeOH in H2O, was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 250 × 100 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 μm, 100 Å, UV = 210 nm) using isocratic condition with 45% aqueous CH3CN, to yield 4.9 mg of caboxamycin (1).

Caboxamycin (1): 1H (400 MHz, CDCl3); δH 8.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H), 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3); δC 164.1, 158.9, 158.8, 149.6, 140.1, 134.5, 128.1, 127.7, 124.9, 120.5, 119.8, 119.7, 115.5, 110.0, LRMS m/z = 256.23 [M+H]+

Viruses and Cells. Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) was derived from the infectious cDNA copy of the cardiotropic CVB3-H3 was amplified in HeLa cells [

5]. The HeLa cells, and mice tissue virus titer were determined by plaque forming unit (PFU) assay [

7]. HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Welgene, Inc. Gyeongsan-si, Korea) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Welgene, Inc.) solution at 37

°C.

Screening of optimization antiviral compounds. The antiviral activity was observed following the previous reports. Briefly, HeLa cells cultured on a 96-well plate were infected with 20 μL of CVB3-H3 (10

6 PFU/mL) and treated with individual compounds, which were serially diluted from 100 μg/mL to 0.1 μg/mL. At 16 hours of post-infection, cell survival was measured with the addition of 8 μL of Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. Rockville, MD) reagent [

5].

Myocarditis mouse model and drug administration. The protocols used in this study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). Six-week-old male Balb/C mice were infected on day 0 by intraperitoneal injection with 2x105 plaque-forming units (PFU) of CVB3. Mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation and sera and various organs (heart, liver, spleen, and pancreas) were collected on days 7, and 12. The virus titer was measured by PFU assay from collected heart and pancreas. Antiviral effects of caboxamycin (100 μg/ml in 100μl saline or saline alone) were administrated intraperitoneally from day 0 post-infection for five consecutive days (CVB3+caboxamycin group (CVB3+Cabo), n = 10; CVB3 group (CVB3); n=10). The heart, livers, and pancreas of mice were taken out and evaluated on days 3, 7, and 12 post infection (p.i). Before analysis, mice were injected with Evans blue dye 14 hours before being examined. The heart inflammation and myocardium damage were observed by histologic analysis. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI, #20191227002). SBRI is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) and abides by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (ILAR) guide.

Total RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR. RNA was isolated from virus-infected mice hearts. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cambridge, MA, USA) to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using 1ug RNA through a reverse transcription reaction using an oligo-dT primer for RNA quantification. Real-time PCR quantitative RNA or DNA analyses were performed in an ABI Sequence Detection System using the SYBR green fluorescence quantification system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The standard PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes, then 40 cycles at 95°C (30 seconds), and 60°C (60 seconds), followed by a standard denaturation curve. All samples were tested in duplicate. The primer sequences shown in the were shown in

Table S1.

Western blot analysis. Protein was extracted from frozen heart samples or cultured HeLa cells using LIPA buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.1% SDS, 1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 % Sodium-deoxycholate] or PBS lysis buffer [1x PBS buffer, 1% Triton-x100], respectively. Approximately 20 μg of protein was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted in 5% skim milk using standard methods. The membranes were probed with the primary antibodies anti-eIF4G1, enterovirus-VP1 (ThermoFisher Scientific), phosphor-p38, BCL-2, and GAPDH (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Detection was performed using an ECL solution (Intron Biotech, Inc. Seongnam-si, Korea), and band intensities were quantified by NIH-ImageJ software [

21].

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry. The hearts, pancreas, and liver were fixed in 10 % formalin, embedded in paraffin, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) was performed using 10 μm paraffin-embedded sections as described previously [

21]. Inflammatory cell infiltration was observed under a light microscope. Stained tissue images were taken and processed using a light microscope (Olympus Co. San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical Analysis. All data were analyzed by Prism9 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and were presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). For analyzing the statistical significance between the two groups, a student's t-test was used. For analyzing statistical significance between multiple groups, a one-way ANOVA was used.