Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

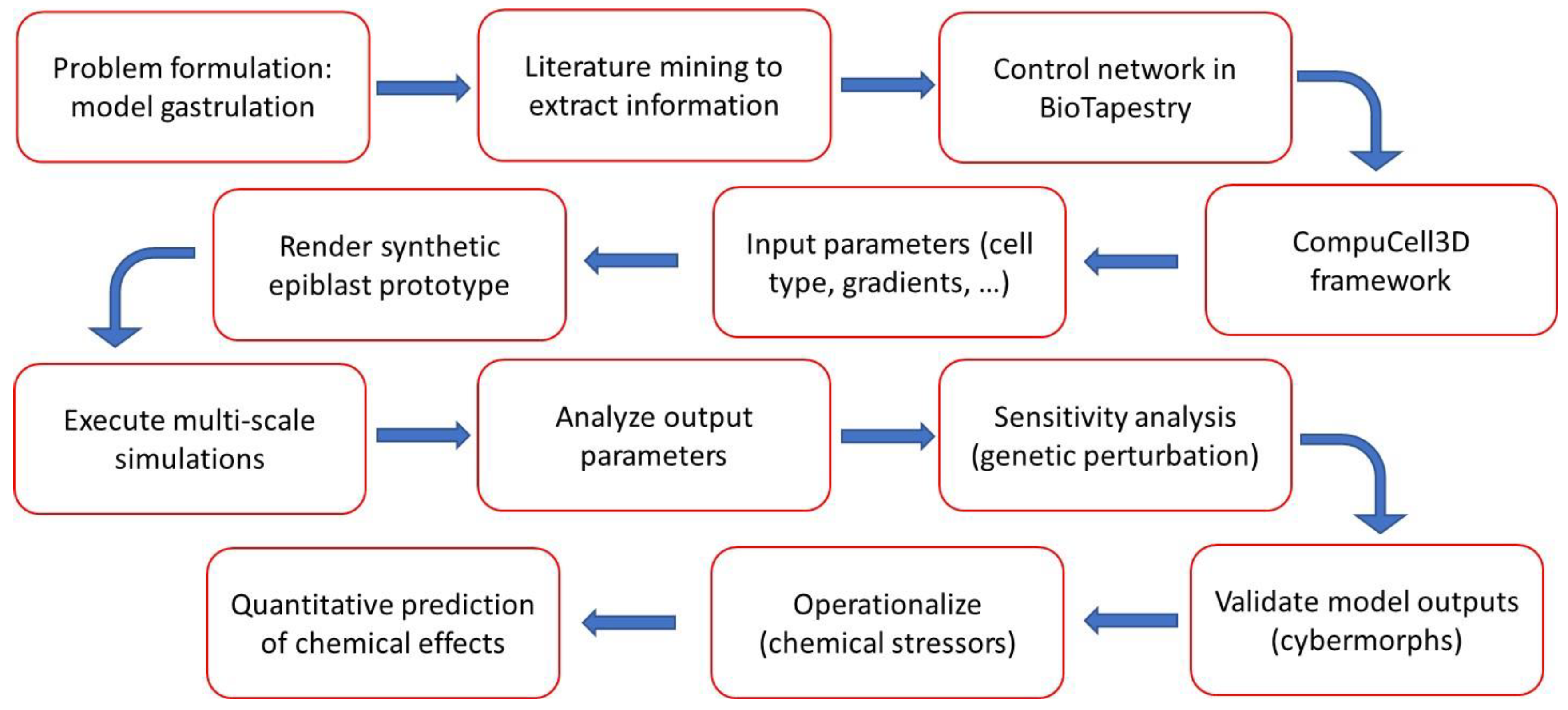

2. Methods and Implementation

2.1. Model scope

2.2. Model construction.

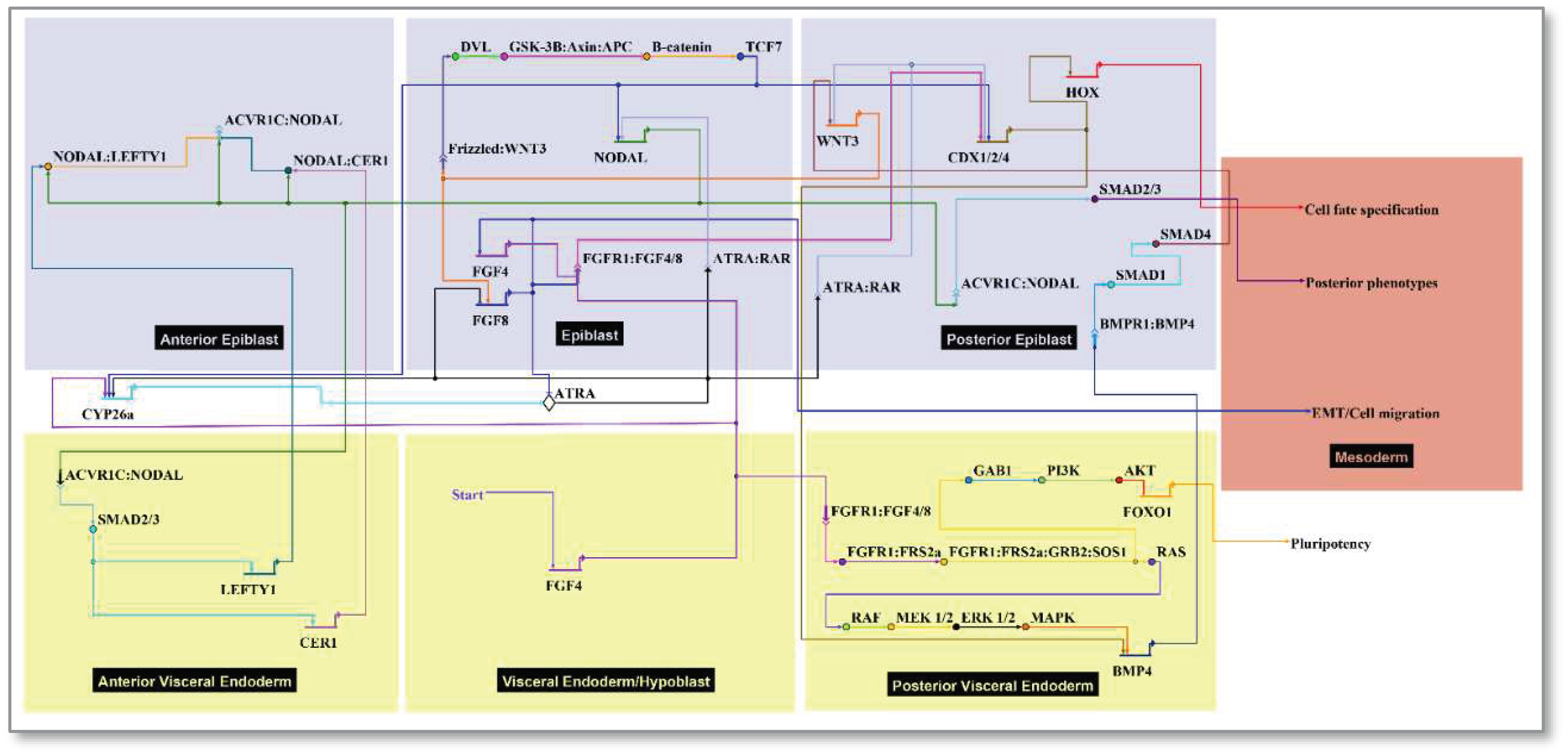

2.3. Cell types and signaling network:

- (i)

- Start FGF4: FGF is required for derivation and maintenance of a primed pluripotent state for human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) in vitro, and for post-implantation growth of the embryonic disc in vivo [25]. FGFR activation preserves hESC pluripotency by transducing information to the nucleus leading to negative regulation of FOXO1 phosphorylation [56,57]. FRS2a (FGFR substrate 2) is an adapter protein linking activated receptor to downstream transducers that regulate the epiblast-stem cell fate decision switch between pluripotency (eg, FOXO1) or differentiation (e.g., RAF/ERK). PI3K-AKT-FOXO1 signaling emerged as the top pathway domain of developmental toxicity from the ToxCast hESC data [58]. It is thus relevant to the epiblast which depends on FGF signals from the endoderm [59]. FGF/FGFR signaling is mediated by the activation of RAS-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT, Phospholipase C Gamma (PLCγ), and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), which intersect and synergize with other signaling pathways such as WNT, ATRA and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β [60]. Cerebrus (CER1) as an antagonist of NODAL/BMP/WNT is expressed near the AVE in co-expression with LEFTY1/2 [25]. The model represents broad expression of FGF4 and FGF8 expression localized to the primitive streak as a transient function of WNT signaling.

- (ii)

- Start ATRA: ATRA signaling is potentially active from early PSC stages [61], but the embryo does not make its own ATRA until mid-gastrulation (~E7.5) [62,63]. RAR/RXR liganding suppresses FGF-signaling and triggers Nodal/LEFTY1/CER1 antagonists in the AVE, ultimately influencing mesodermal Hox gene specification through CDX. The pluripotent epiblast is protected from premature differentiation until exposure to inductive cues in strictly controlled spatially and temporally organized patterns guiding fetal formation [31]. This includes precocious ATRA, an endogenous regulator of the patterned Hox gene expression. The removal of ATRA is required for correct Nodal expression during early embryonic patterning and is primarily due to Cytochrome P450 CYP26 enzymatic expression (primarily Cyp26a1) in the extraembryonic tissues surrounding the embryo E5.5 – E6.5 [39,40,54]. Cyp26-deficient mouse embryos show defects that resemble mutants lacking Lefty1 and Cer1 due to up-regulation of Nodal activity [64]. Similarly, exogenous maternal ATRA (oral, 50 mg/kg on E5.5) has similar effects suggesting the embryo is normally protected from premature ATRA exposure but may succumb to defects with retinoid drugs (e.g., tretinoin, isotretinoin) or CP26 inhibitors (e.g., triazole antifungal agents) [40]. TCF7 (gene for TCF-1, the WNT nuclear effector) has overlapping expression with SMADs.

3. Results

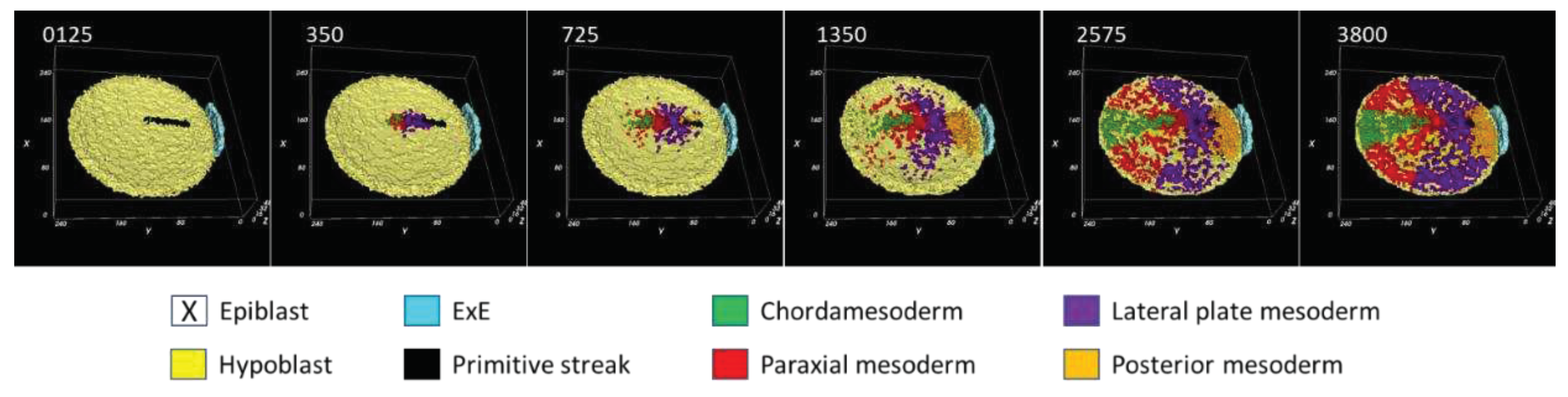

3.1. Morphodynamics:

3.2. Primitive streak formation:

3.3. Mesodermal lineages:

3.4. Dynamical regulation:

3.5. Perturbing the control network:

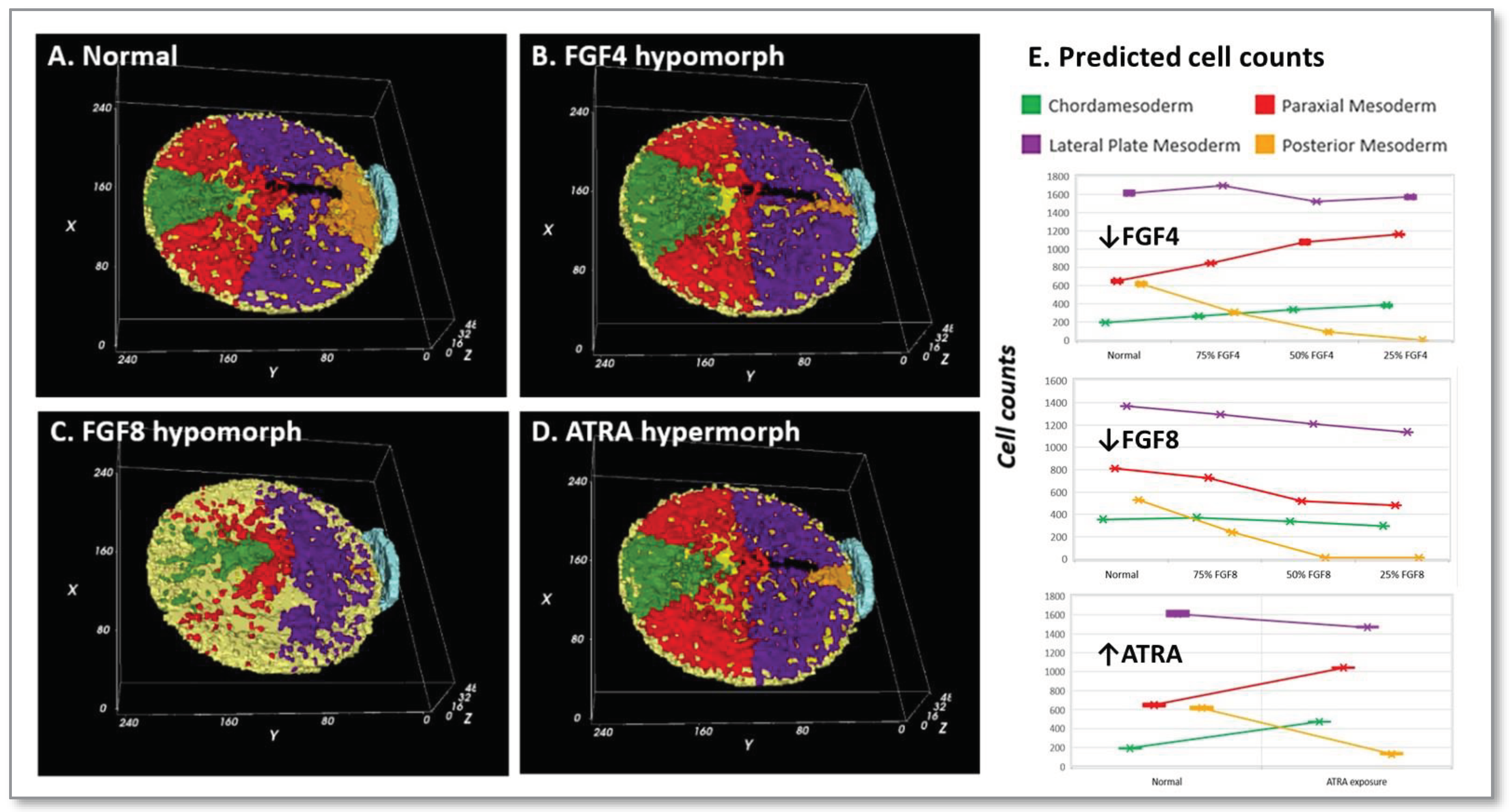

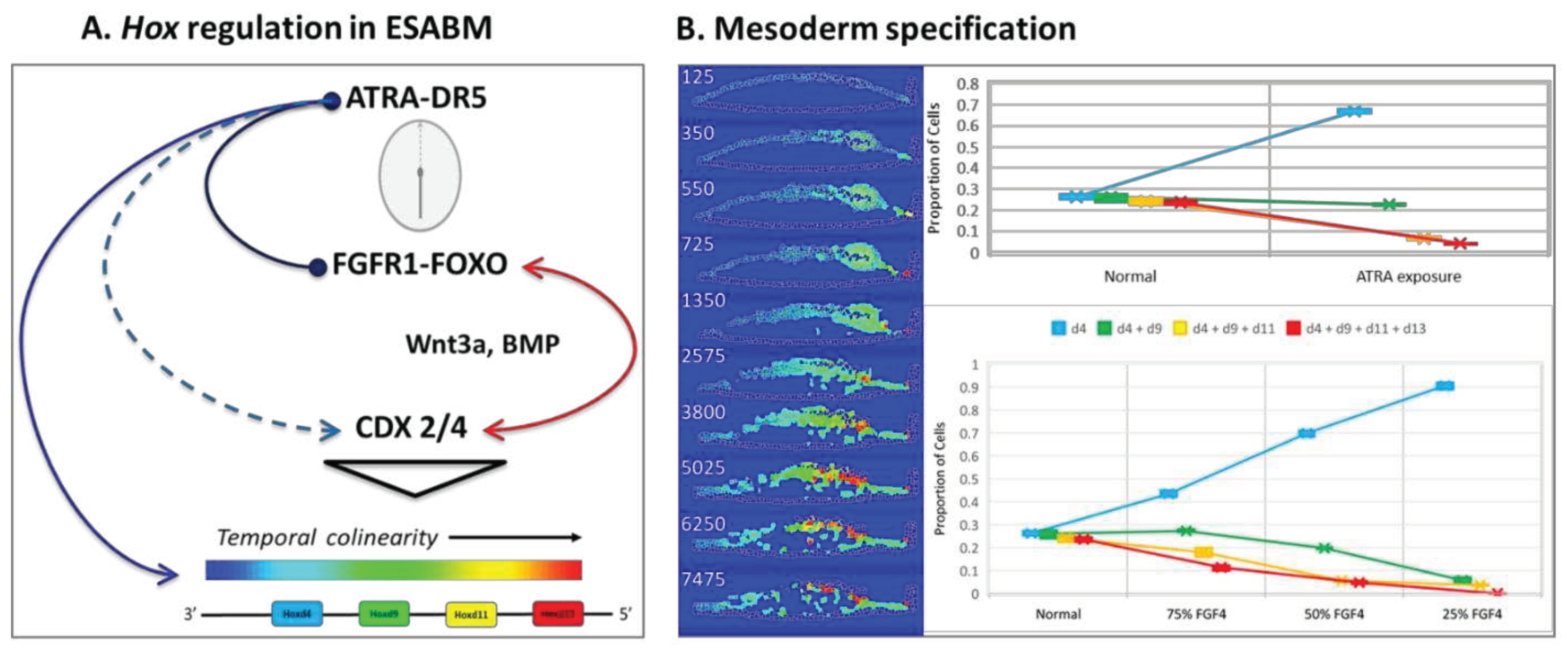

- (A)

- FGF4 is a positive determinant of CDX-dependent regulation of the HOX clock. Progressive activation of Cdx2/4 specifies progressive mesodermal cell fates (green, chordamesoderm; red, paraxial mesoderm; purple, lateral plate mesoderm; orange, posterior mesoderm), and endoderm (yellow). Trajectories of individual cells in each mesodermal field can be traced in the simulation (see supplemental video S2).

- (B)

- Pace of the synthetic HOX clock was slowed by FGF down-regulation, thereby affecting colinear Hox activation through Cdx2/4. A 25% reduction in FGF4 had a critical effect on posterior mesodermal specification, with rarefication of cell numbers in this field foreshadowing caudal deficiencies observed in the mouse with 25% to 50% loss of FGFR1 function [53]. The broader effect reflected anteriorization of the mesodermal field shown here at 50% FGF4 reduction with substantial rarefication of the posterior mesodermal population.

- (C)

- FGF8 signaling stimulates cell migration of nascent mesoderm away from the primitive streak [51]. Mesodermal cell migration speed is set as a function of FGF8 concentration, which is expressed at the primitive streak. A 50% reduction of FGF8 is shown. In the complete absence of FGF8 (not shown), we have no migration away from the primitive streak and the mesodermal cells pile up and slowly expand outwards only due to contact forces from more cells undergoing EMT.

- (D)

- Retinoid signaling: the embryo acquires its potential for de novo ATRA synthesis around E7.5 [62,63] and is protected from maternal ATRA exposure by the local expression of Cyp26a1 [69]. Precocious ATRA exposure was modeled as an inhibition of CYP26a1 activity at a level that yielded a 50% reduction in Cdx2/4 expression.

- (E)

- Quantitative mesodermal fields and cell counts computed for 5 replicates (mean + SD for n = 5 runs).

- (A)

- Regulatory network implemented for abstracted Hox genes in the model, limited for simplicity to sequential activation of Hoxd4, Hoxd9, Hoxd11, and Hoxd13 (3’-anterior, 5’-posterior) as reported in a mouse gastruloid system [67]. An autonomous HOX clock in ESABM is paced by FGF4 and ATRA signaling coordinated by CDX. FGF activation of Cdx2/4 (assisted by WNT, BMP4) speeds the HOX clock for co-linear expression of more posterior (5’) cell fates, according to color addresses in the abstracted model. Responsiveness to ATRA is highest for Hox genes at the 3’ end in a HOX cluster while genes at the 5’ end are more responsive to FGF signaling [54].

- (B)

- Hox states in the model cell field visualized across the 7500 MCS for a normal simulation. Mid-longitudinal sections of the embryonic disc shown as a snapshot at the designated MCS, with the trilaminar disc oriented anterior (left) to posterior (right). Quantitative mesodermal fields were scored at MCS 7500 for n = 5 replicates (mean + compucell SD). Anteriorization of Hox gene patterning is predicted for FGF4 hypomorphs or ATRA hypermorphs.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USEPA. New Approach Methods Work Plan (V2).U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, 2021,EPA/600/X-21/209. https://www.epa.gov/chemical-research/new-approach-methods-work-plan.

- Piersma, A.H.; Baker, N.C.; Daston, G.P.; Flick, B.; Fujiwara, M.; Knudsen, T.B.; Spielmann, H.; Suzuki, N.; Tsaioun, K.; Kojima, H. Pluripotent stem cell assays: Modalities and applications for predictive developmental toxicity. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmflash, A.; Sorre, B.; Etoc, F.; Siggia, E.D.; Brivanlou, A.H. A method to recapitulate early embryonic spatial patterning in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.T.; Lundin, B.F.; Iyer, N.; Ashton, L.M.; A Sethares, W.; Willett, R.M.; Ashton, R.S. Engineering induction of singular neural rosette emergence within hPSC-derived tissues. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrin, A.; Tabata, Y.; Paquet, E.R.; Vuaridel, A.R.; Rivest, F.R.; Naef, F.; Lutolf, M.P. Engineered signaling centers for the spatially controlled patterning of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunovic, M.; Metzger, J.J.; Etoc, F.; Yoney, A.; Ruzo, A.; Martyn, I.; Croft, G.; You, D.S.; Brivanlou, A.H.; Siggia, E.D. A 3D model of a human epiblast reveals BMP4-driven symmetry breaking. Nature 2019, 21, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xue, X.; Shao, Y.; Wang, S.; Esfahani, S.N.; Li, Z.; Muncie, J.M.; Lakins, J.N.; Weaver, V.M.; Gumucio, D.L.; et al. Controlled modelling of human epiblast and amnion development using stem cells. Nature 2019, 573, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.-F.; Borges, R.M.; Fillatre, J.; de Oliveira-Melo, M.; Cheng, T.; Thisse, B.; Thisse, C. Construction of a mammalian embryo model from stem cells organized by a morphogen signalling centre. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadei, G.; Handford, C.E.; Qiu, C.; De Jonghe, J.; Greenfeld, H.; Tran, M.; Martin, B.K.; Chen, D.-Y.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Hanna, J.H.; et al. Embryo model completes gastrulation to neurulation and organogenesis. Nature 2022, 610, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, N.R.; Shin, J.; Cuskey, S.; Tian, Y.; Nicol, N.R.; Doersch, T.E.; Seipel, F.; McCalla, S.G.; Roy, S.; Ashton, R.S. Modular derivation of diverse, regionally discrete human posterior CNS neurons enables discovery of transcriptomic patterns. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarazi, S.; Aguilera-Castrejon, A.; Joubran, C.; Ghanem, N.; Ashouokhi, S.; Roncato, F.; Wildschutz, E.; Haddad, M.; Oldak, B.; Gomez-Cesar, E.; et al. Post-gastrulation synthetic embryos generated ex utero from mouse naive ESCs. Cell 2022, 185, 3290–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, J.A.; Chaturvedi, R.; Huang, C.; Cickovski, T.; Coffland, J.; Thomas, G.; Forgacs, G.; Alber, M.; Hentschel, G.; Newman, S.A.; et al. CompuCell, a multi-model framework for simulation of morphogenesis. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macal, C.M.; North, M.J. Tutorial on agent-based modelling and simulation. J. Simul. 2010, 4, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirashima, T.; Rens, E.G.; Merks, R.M.H. Cellular Potts modeling of complex multicellular behaviors in tissue morphogenesis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2017, 59, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, C.M.; Kemp, M.L.; Voit, E.O. Agent-based modeling of morphogenetic systems: Advantages and challenges. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, T.B.; Spencer, R.M.; Pierro, J.D.; Baker, N.C. Computational biology and in silico toxicodynamics. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 23-24, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.S.; Bagheri, N. Agent-Based Models Predict Emergent Behavior of Heterogeneous Cell Populations in Dynamic Microenvironments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, S.D.; Belmonte, J.M.; Gens, J.S.; Clendenon, S.G.; Glazier, J.A. A Multi-cell, Multi-scale Model of Vertebrate Segmentation and Somite Formation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Judson, R.S.; Reif, D.M.; Sipes, N.S.; Singh, A.V.; Chandler, K.J.; DeWoskin, R.; Dix, D.J.; Kavlock, R.J.; Knudsen, T.B. Environmental Impact on Vascular Development Predicted by High-Throughput Screening. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2011, 119, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.C.; Hutson, M.; Seifert, A.W.; Spencer, R.M.; Knudsen, T.B. Computational modeling and simulation of genital tubercle development. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 64, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, M.S.; Leung, M.C.K.; Baker, N.C.; Spencer, R.M.; Knudsen, T.B. Computational Model of Secondary Palate Fusion and Disruption. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhyapok, P.; Piatkowska, A.M.; Norman, M.J.; Clendenon, S.G.; Stern, C.D.; Glazier, J.A.; Belmonte, J.M. A mechanical model of early somite segmentation. iScience 2021, 24, 102317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, D.L.; Jayaweera, D. Effective solar prosumer identification using net smart meter data. Int. J. Elect. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijuan-Sala, B.; Griffiths, J.A.; Guibentif, C.; Hiscock, T.W.; Jawaid, W.; Calero-Nieto, F.J.; Mulas, C.; Ibarra-Soria, X.; Tyser, R.C.V.; Ho, D.L.L.; et al. A single-cell molecular map of mouse gastrulation and early organogenesis. Nature 2019, 566, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molè, M.A.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Shahbazi, M.N.; Weberling, A.; Weatherbee, B.A.T.; Gantner, C.W.; Sancho-Serra, C.; Richardson, L.; Drinkwater, A.; Syed, N.; et al. A single cell characterisation of human embryogenesis identifies pluripotency transitions and putative anterior hypoblast centre. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossant, J.; Tam, P.P. Early human embryonic development: Blastocyst formation to gastrulation. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, S.; Qin, S.; Huang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Shi, Y.; et al. The single-cell and spatial transcriptional landscape of human gastrulation and early brain development. Cell Stem Cell 2023, 30, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Arias, A.M.; Sutherland, A. The primitive streak and cellular principles of building an amniote body through gastrulation. Science 2021, 374, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Mazutis, L.; Akartuna, I.; Tallapragada, N.; Veres, A.; Li, V.; Peshkin, L.; Weitz, D.A.; Kirschner, M.W. Droplet Barcoding for Single-Cell Transcriptomics Applied to Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell 2015, 161, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDole, K.; Guignard, L.; Amat, F.; Berger, A.; Malandain, G.; Royer, L.A.; Turaga, S.C.; Branson, K.; Keller, P.J. In Toto Imaging and Reconstruction of Post-Implantation Mouse Development at the Single-Cell Level. Cell 2018, 175, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-Y.; Huang, W.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Meir, Y.-J.J. Capturing Pluripotency and Beyond. Cells 2021, 10, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A. Role ofHoxgenes in stem cell differentiation. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 583–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, J.; Duboule, D. Embryonic timing, axial stem cells, chromatin dynamics, and the Hox clock. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017, 31, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Principles of Self-Organization of the Mammalian Embryo. Cell 2020, 183, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Mantziou, V.; Moris, N.; Arias, A.M. Human gastrulation: The embryo and its models. Dev. Biol. 2021, 474, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Zeng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Gu, J.; Ge, L.; Tang, F.; Qu, Z.; Hu, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, K.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals lineage segregation in early post-implantation mouse embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 9840–9854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzouanacou, E.; Wegener, A.; Wymeersch, F.J.; Wilson, V.; Nicolas, J.-F. Redefining the Progression of Lineage Segregations during Mammalian Embryogenesis by Clonal Analysis. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.; Knudsen, T.; Williams, A.J. Abstract Sifter: a comprehensive front-end system to PubMed. F1000Research 2017, 6, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Abed, S.; Dollé, P.; Metzger, D.; Beckett, B.; Chambon, P.; Petkovich, M. The retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1, is essential for normal hindbrain patterning, vertebral identity, and development of posterior structures. Minerva Anestesiol. 2001, 15, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, M.; Yashiro, K.; Takaoka, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Hamada, H. Removal of maternal retinoic acid by embryonic CYP26 is required for correct Nodal expression during early embryonic patterning. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, F.; Erler, T.; Russell, A.; James, R. Expression of Cdx-2 in the mouse embryo and placenta: Possible role in patterning of the extra-embryonic membranes. Dev. Dyn. 1995, 204, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neijts, R.; Amin, S.; van Rooijen, C.; Deschamps, J. Cdx is crucial for the timing mechanism driving colinear Hox activation and defines a trunk segment in the Hox cluster topology. Dev. Biol. 2017, 422, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, L.A.; Yamada, S.; Kuehn, M.R. Genetic dissection ofnodalfunction in patterning the mouse embryo. Development 2001, 128, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murohashi, M.; Nakamura, T.; Tanaka, S.; Ichise, T.; Yoshida, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Shibuya, M.; Schlessinger, J.; Gotoh, N. An FGF4-FRS2α-Cdx2 Axis in Trophoblast Stem Cells Induces Bmp4 to Regulate Proper Growth of Early Mouse Embryos. STEM CELLS 2009, 28, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouilleau, V.; Vaslin, C.; Robert, R.; Gribaudo, S.; Nicolas, N.; Jarrige, M.; Terray, A.; Lesueur, L.; Mathis, M.W.; Croft, G.; et al. Dynamic extrinsic pacing of the HOX clock in human axial progenitors controls motor neuron subtype specification. Development 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgani, S.M.; Metzger, J.J.; Nichols, J.; Siggia, E.D.; Hadjantonakis, A.-K. Micropattern differentiation of mouse pluripotent stem cells recapitulates embryo regionalized cell fate patterning. eLife 2018, 7, e32839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, S.; Davis, S.; Klingensmith, J.; Mishina, Y. BMP signaling in the epiblast is required for proper recruitment of the prospective paraxial mesoderm and development of the somites. Development 2006, 133, 3767–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Saijoh, Y.; Perea-Gomez, A.; Shawlot, W.; Behringer, R.R.; Ang, S.-L.; Hamada, H.; Meno, C. Nodal antagonists regulate formation of the anteroposterior axis of the mouse embryo. Nature 2004, 428, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theka, I.; Sottile, F.; Cammisa, M.; Bonnin, S.; Sanchez-Delgado, M.; Di Vicino, U.; Neguembor, M.V.; Arumugam, K.; Aulicino, F.; Monk, D.; et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway safeguards epigenetic stability and homeostasis of mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemler, R.; Hierholzer, A.; Kanzler, B.; Kuppig, S.; Hansen, K.; Taketo, M.M.; de Vries, W.N.; Knowles, B.B.; Solter, D. Stabilization of β-catenin in the mouse zygote leads to premature epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the epiblast. Development 2004, 131, 5817–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, K.M.; A Yatskievych, T.; Konieczka, J.; Bobbs, A.S.; Antin, P.B. FGF signalling through RAS/MAPK and PI3K pathways regulates cell movement and gene expression in the chicken primitive streak without affecting E-cadherin expression. BMC Dev. Biol. 2011, 11, 20–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimura, T.; Pourquié, O. Hox genes in time and space during vertebrate body formation. Dev. Growth Differ. 2007, 49, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.; Rowland, J.E.; van de Ven, C.; Bialecka, M.; Novoa, A.; Carapuco, M.; van Nes, J.; de Graaff, W.; Duluc, I.; Freund, J.-N.; et al. Cdx and Hox Genes Differentially Regulate Posterior Axial Growth in Mammalian Embryos. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, C.; De Kumar, B.; Krumlauf, R. Hox genes: Downstream “effectors” of retinoic acid signaling in vertebrate embryogenesis. genesis 2019, 57, e23306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.-Z.; Zhu, Y.; Warner, D.; Ding, J. Analysis of extraembryonic mesodermal structure formation in the absence of morphological primitive streak. Dev. Growth Differ. 2016, 58, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yalcin, S.; Lee, D.-F.; Yeh, T.-Y.J.; Lee, S.-M.; Su, J.; Mungamuri, S.K.; Rimmelé, P.; Kennedy, M.; Sellers, R.; et al. FOXO1 is an essential regulator of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nature 2011, 13, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wei, R.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, H.; Mu, Y.; Hong, T. FoxO1 inhibition promotes differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into insulin producing cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 362, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurlinden, T.J.; Saili, K.S.; Rush, N.; Kothiya, P.; Judson, R.S.; A Houck, K.; Hunter, E.S.; Baker, N.C.; A Palmer, J.; Thomas, R.S.; et al. Profiling the ToxCast Library With a Pluripotent Human (H9) Stem Cell Line-Based Biomarker Assay for Developmental Toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 174, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martello, G.; Smith, A. The Nature of Embryonic Stem Cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 647–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M.; Quan, M.; Zhang, J.-S.; Li, X. FGF Signaling Pathway: A Key Regulator of Stem Cell Pluripotency. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.A.; Smith, A.M.; Egnash, L.A.; Colwell, M.R.; Donley, E.L.; Kirchner, F.R.; Burrier, R.E. A human induced pluripotent stem cell-based in vitro assay predicts developmental toxicity through a retinoic acid receptor-mediated pathway for a series of related retinoid analogues. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 73, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, G. Retinoic Acid Synthesis and Signaling during Early Organogenesis. Cell 2008, 134, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, T.J.; Duester, G. Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Gomez, A.; Vella, F.D.; Shawlot, W.; Oulad-Abdelghani, M.; Chazaud, C.; Meno, C.; Pfister, V.; Chen, L.; Robertson, E.; Hamada, H.; et al. Nodal Antagonists in the Anterior Visceral Endoderm Prevent the Formation of Multiple Primitive Streaks. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Burdsal, C.; Periasamy, A.; Lewandoski, M.; Sutherland, A. Mouse primitive streak forms in situ by initiation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition without migration of a cell population. Dev. Dyn. 2011, 241, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Fan, R.; Lith, S.C.; Dicke, A.-K.; Drexler, H.C.; Kremer, L.; Kuempel-Rink, N.; Hekking, L.; Stehling, M.; Bedzhov, I. Rap1 controls epiblast morphogenesis in sync with the pluripotency states transition. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1937–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beccari, L.; Moris, N.; Girgin, M.; Turner, D.A.; Baillie-Johnson, P.; Cossy, A.-C.; Lutolf, M.P.; Duboule, D.; Arias, A.M. Multi-axial self-organization properties of mouse embryonic stem cells into gastruloids. Nature 2018, 562, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinglay, S.; Bulajić, M.; Rahe, D.P.; Huang, E.; Brosh, R.; Mamrak, N.E.; King, B.R.; German, S.; Cadley, J.A.; Rieber, L.; et al. Synthetic regulatory reconstitution reveals principles of mammalian Hox cluster regulation. Science 2022, 377, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Ivins, S.; Cook, A.C.; Baldini, A.; Scambler, P.J. Cyp26 genes a1, b1 and c1 are down-regulated in Tbx1 null mice and inhibition of Cyp26 enzyme function produces a phenocopy of DiGeorge Syndrome in the chick. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 3394–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengerke, C.; Daley, G.Q. Caudal genes in blood development and leukemia. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2012, 1266, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, V.P.S.; Humphries, R.K.; Buske, C. Beyond Hox: the role of ParaHox genes in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Blood 2012, 120, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houle, M.; Prinos, P.; Iulianella, A.; Bouchard, N.; Lohnes, D. Retinoic Acid Regulation of Cdx1: an Indirect Mechanism for Retinoids and Vertebral Specification. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 6579–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, T.E.; Hess, B.; Savory, J.G.A.; Ringuette, R.; Lohnes, D. Role of Cdx factors in early mesodermal fate decisions. Development 2019, 146, dev170498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menegola, E.; Broccia, M.L.; Di Renzo, F.; Giavini, E. Postulated pathogenic pathway in triazole fungicide induced dysmorphogenic effects. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006, 22, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Meyers, E.N.; Lewandoski, M.; Martin, G.R. Targeted disruption of Fgf8 causes failure of cell migration in the gastrulating mouse embryo. Minerva Anestesiol. 1999, 13, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciruna, B.; Rossant, J. FGF Signaling Regulates Mesoderm Cell Fate Specification and Morphogenetic Movement at the Primitive Streak. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Sakamuru, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; Huang, R.; Kleinstreuer, N.C.; Chen, Y.; Shu, Y.; Knudsen, T.B.; Xia, M. Identification and Profiling of Environmental Chemicals That Inhibit the TGFβ/SMAD Signaling Pathway. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anatomical Annotation | Index | Signals | Model Implementation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium (implantation chamber) 2 | Black | ATRA 3 | Slows HOX clock | [39] |

| Ectoderm | Blue | -- | -- | -- |

| Extraembryonic Ectoderm | EEE 4 | CYP26a1 | ATRA breakdown | [39], [40], [41], [42] |

| Epiblast | EPI 5 | NODAL | Mesoendoderm induction | [43] |

| Surface ectoderm, Neuromesoderm | Blue | -- | Residual epiblast | -- |

| Endoderm | Yellow | -- | -- | -- |

| Visceral Endoderm (primitive) | VE | FGF4 | PVE, HOX clock, draws mesoderm | [44], [45] |

| Posterior Visceral Endoderm | PVE | BMP4 | Posterior polarization | [46], [47] |

| Anterior Visceral Endoderm | AVE | CER1, LEFTY1 | NODAL antagonists | [48] |

| Primitive Streak | Black | WNT3, CDX 6 | EMT 7 | [40], [49], [50] |

| Organizer Node | Black | WNT3, FGF8 | Paces HOX clock, stimulates migration | [40], [42], [51] |

| Mesoderm | Multi | HOX pattern | Mesodermal fate | -- |

| Chordamesoderm | Green | Cdx-Hox | Rostral | [52], [53], [54] |

| Paraxial Mesoderm | Red | Cdx-Hox | Intermediate | [52], [53], [54] |

| Lateral Plate Mesoderm | Purple | Cdx-Hox | Lateral | [52], [53], [54] |

| Posterior Mesoderm | Orange | Cdx-Hox | Caudal | [52], [53], [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).