Submitted:

29 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Defining excess folate

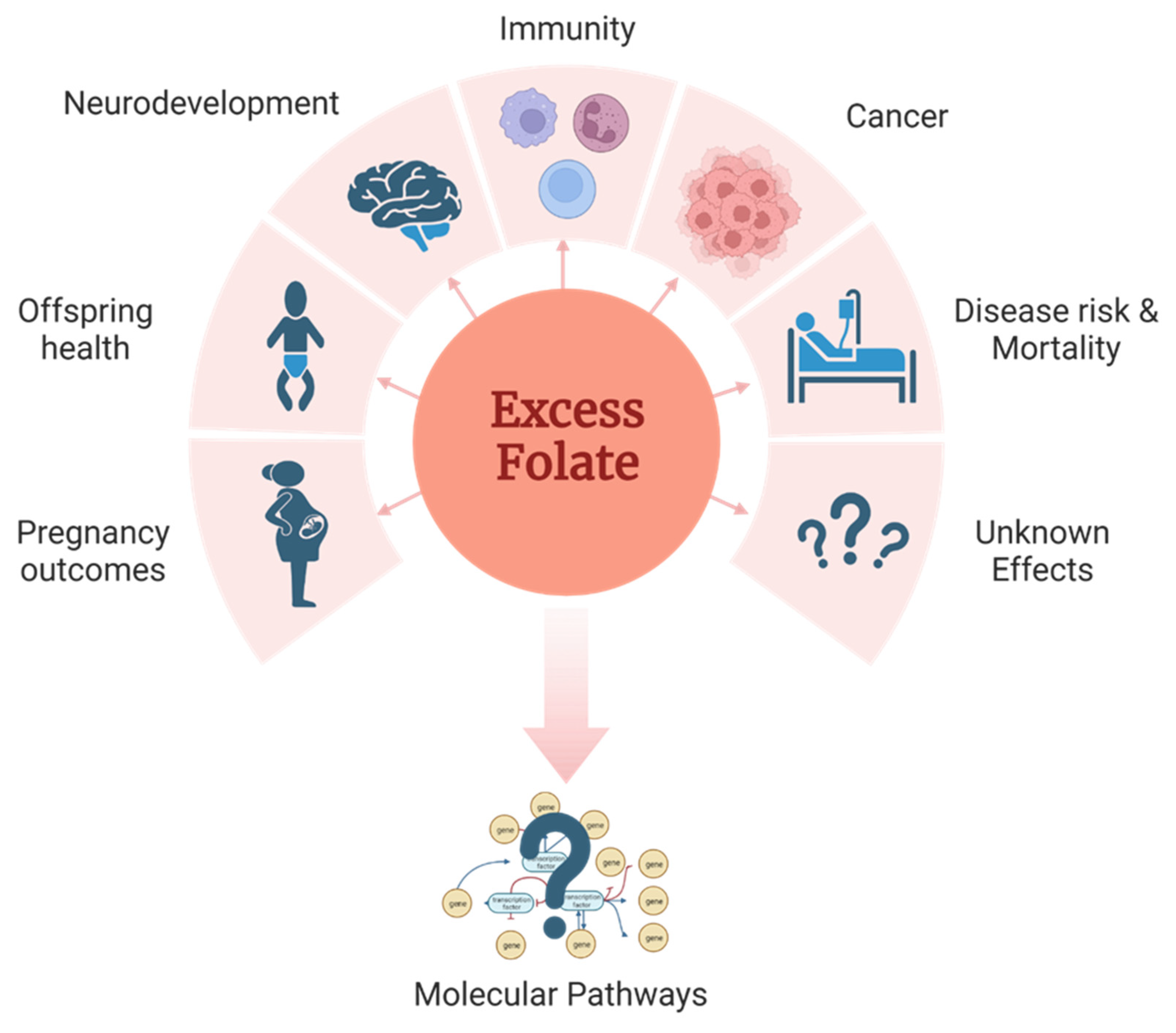

3. Health impact of excess folate

3.1. Pregnancy and birth related outcomes

3.2. Disease risk in offspring

3.3. Neurodevelopment

3.4. Immune function and allergies.

3.5. Carcinogenesis

3.6. Morbidity and mortality.

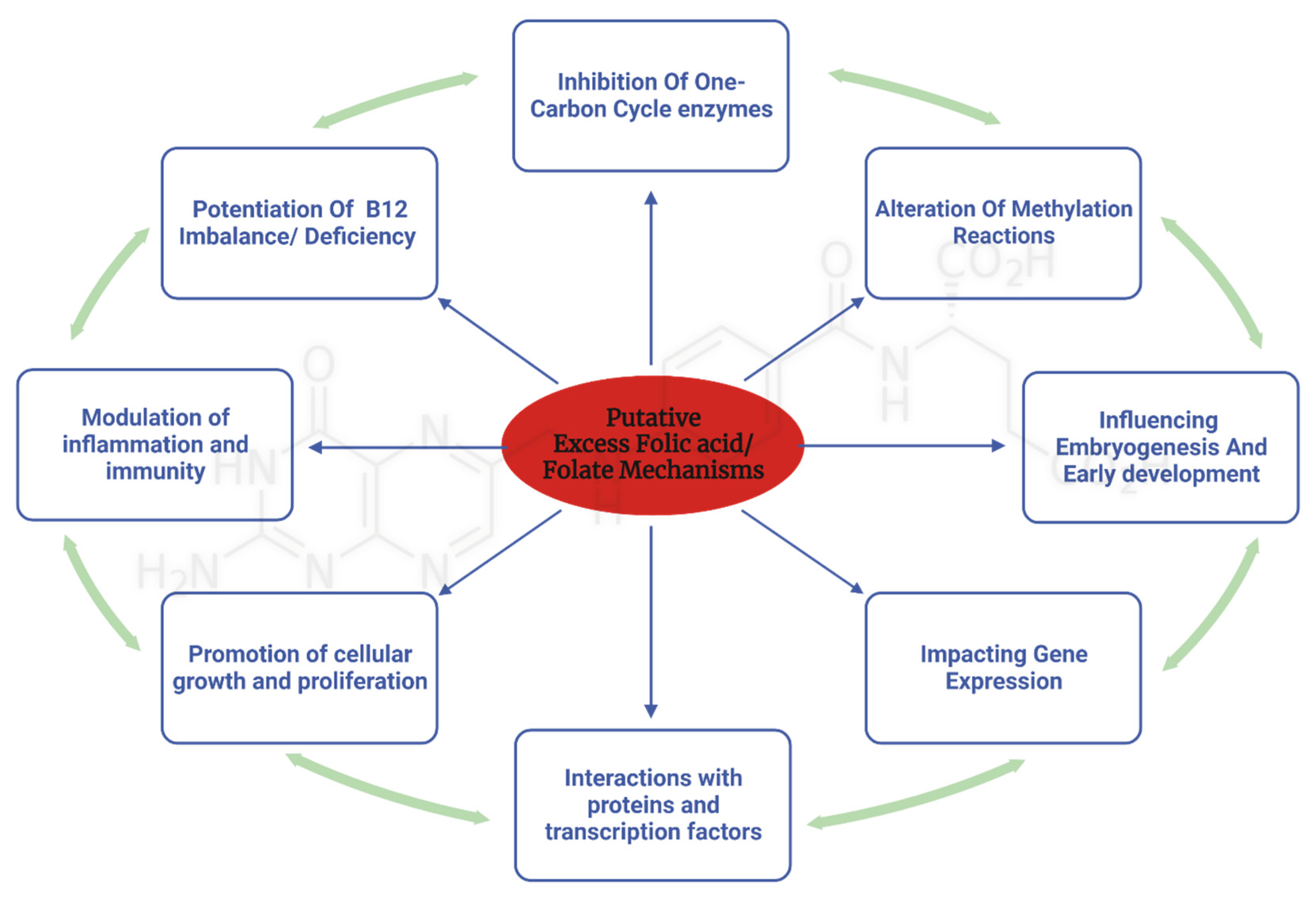

4. Mechanisms Underlying the Adverse Effects of Excess Folate Intake

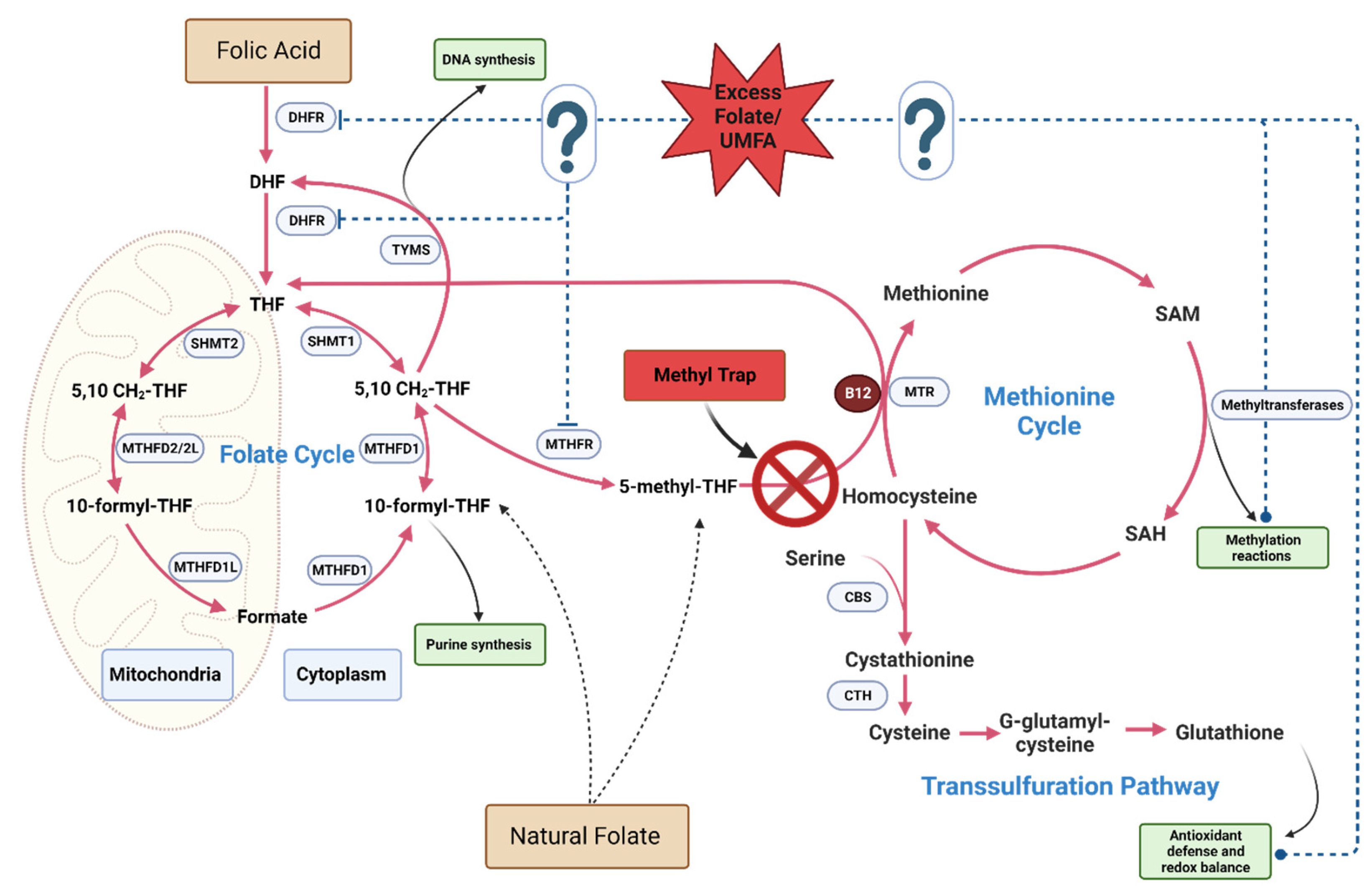

4.1. Excess folate and B12 dependent mechanisms

4.2. Mechanisms Related to the One-Carbon Cycle

4.2.1. Pseudo-MTHFR Deficiency

4.2.2. Altered folate cycle and Methylation Patterns

4.2.3. Accumulation of Unmetabolized Folic Acid (UMFA)

4.3. Non-Canonical pathways

4.3.1. Folic acid specific pathways

4.3.2. Mechanisms related to elevated folate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maruvada, P.; Stover, P.J.; Mason, J.B.; Bailey, R.L.; Davis, C.D.; Field, M.S.; Finnell, R.H.; Garza, C.; Green, R.; Gueant, J.-L., et al. Knowledge gaps in understanding the metabolic and clinical effects of excess folates/folic acid: a summary, and perspectives, from an NIH workshop. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020, 112, 1390-1403. [CrossRef]

- Field, M.S.; Stover, P.J. Safety of folic acid. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2018, 1414, 59-71. [CrossRef]

- Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. Excessive folic acid intake and relation to adverse health outcome. Biochimie 2016, 126, 71-78. [CrossRef]

- Crider, K.S.; Bailey, L.B.; Berry, R.J. Folic acid food fortification-its history, effect, concerns, and future directions. Nutrients 2011, 3, 370-384. [CrossRef]

- Shulpekova, Y.; Nechaev, V.; Kardasheva, S.; Sedova, A.; Kurbatova, A.; Bueverova, E.; Kopylov, A.; Malsagova, K.; Dlamini, J.C.; Ivashkin, V. The Concept of Folic Acid in Health and Disease. Molecules 2021, 26, 3731. [CrossRef]

- Menezo, Y.; Elder, K.; Clement, A.; Clement, P. Folic Acid, Folinic Acid, 5 Methyl TetraHydroFolate Supplementation for Mutations That Affect Epigenesis through the Folate and One-Carbon Cycles. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 197. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.D.; O’Connor, D.L. Maternal folic acid and multivitamin supplementation: International clinical evidence with considerations for the prevention of folate-sensitive birth defects. Prev Med Rep 2021, 24, 101617. [CrossRef]

- P, M.; Pj, S.; Jb, M.; Rl, B.; Cd, D.; Ms, F.; Rh, F.; C, G.; R, G.; Jl, G., et al. Knowledge gaps in understanding the metabolic and clinical effects of excess folates/folic acid: a summary, and perspectives, from an NIH workshop. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2020, 112, 1390-1403. [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R.; Kirsch, S.H.; Dilmann, S.; Klein, C.; Eckert, R.; Geisel, J.; Herrmann, W. Folic acid causes higher prevalence of detectable unmetabolized folic acid in serum than B-complex: a randomized trial. European Journal of Nutrition 2016, 55, 1021-1028. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.; McPartlin, J.; Scott, J. Folic acid fortification and public health: Report on threshold doses above which unmetabolised folic acid appear in serum. BMC Public Health 2007, 10.1186/1471-2458-7-41. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.S.Q.; Muldoon, K.A.; Sheyholislami, H.; Behan, N.; Lamers, Y.; Rybak, N.; White, R.R.; Harvey, A.L.J.; Gaudet, L.M.; Smith, G.N., et al. Impact of high-dose folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on biomarkers of folate status and 1-carbon metabolism: An ancillary study of the Folic Acid Clinical Trial (FACT). Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 113, 1361-1371. [CrossRef]

- Palchetti, C.Z.; Paniz, C.; De Carli, E.; Marchioni, D.M.; Colli, C.; Steluti, J.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Fazili, Z.; Guerra-Shinohara, E.M. Association between Serum Unmetabolized Folic Acid Concentrations and Folic Acid from Fortified Foods. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2017, 36, 572-578. [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Mayer, C.; McCartney, H.; Devlin, A.M.; Lamers, Y.; Vercauteren, S.M.; Wu, J.K.; Karakochuk, C.D. Detectable Unmetabolized Folic Acid and Elevated Folate Concentrations in Folic Acid-Supplemented Canadian Children With Sickle Cell Disease. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 642306. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; Sternberg, M.R.; Fazili, Z.; Yetley, E.A.; Lacher, D.A.; Bailey, R.L.; Johnson, C.L. Unmetabolized folic acid is detected in nearly all serum samples from US children, adolescents, and adults. J Nutr 2015, 145, 520-531. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; Johnson, C.L.; Jain, R.B.; Yetley, E.A.; Picciano, M.F.; Rader, J.I.; Fisher, K.D.; Mulinare, J.; Osterloh, J.D. Trends in blood folate and vitamin B-12 concentrations in the United States, 1988 2004. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 86, 718-727.

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; Hughes, J.P.; Lacher, D.A.; Bailey, R.L.; Berry, R.J.; Zhang, M.; Yetley, E.A.; Rader, J.I.; Sempos, C.T.; Johnson, C.L. Estimation of Trends in Serum and RBC Folate in the U.S. Population from Pre- to Postfortification Using Assay-Adjusted Data from the NHANES 1988–2010. The Journal of Nutrition 2012, 142, 886-893. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; Dodd, K.W.; Gahche, J.J.; Dwyer, J.T.; McDowell, M.A.; Yetley, E.A.; Sempos, C.A.; Burt, V.L.; Radimer, K.L.; Picciano, M.F. Total folate and folic acid intake from foods and dietary supplements in the United States: 2003-2006. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 91, 231-237. [CrossRef]

- Colapinto, C.K.; O’Connor, D.L.; Sampson, M.; Williams, B.; Tremblay, M.S. Systematic review of adverse health outcomes associated with high serum or red blood cell folate concentrations. Journal of Public Health 2016, 38, e84-e97. [CrossRef]

- Colapinto, C.K.; O’Connor, D.L.; Dubois, L.; Tremblay, M.S. Prevalence and correlates of high red blood cell folate concentrations in the Canadian population using 3 proposed cut-offs. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2015, 40, 1025-1030. [CrossRef]

- Colapinto, C.K.; O’Connor, D.L.; Tremblay, M.S. Folate status of the population in the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2011, 183, E100-E106. [CrossRef]

- Fazili, Z.; Sternberg, M.R.; Potischman, N.; Wang, C.-Y.; Storandt, R.J.; Yeung, L.; Yamini, S.; Gahche, J.J.; Juan, W.; Qi, Y.P., et al. Demographic, Physiologic, and Lifestyle Characteristics Observed with Serum Total Folate Differ Among Folate Forms: Cross-Sectional Data from Fasting Samples in the NHANES 2011–2016. The Journal of Nutrition 2019, 150, 851-860. [CrossRef]

- Plumptre, L.; Tammen, S.A.; Sohn, K.J.; Masih, S.P.; Visentin, C.E.; Aufreiter, S.; Malysheva, O.; Schroder, T.H.; Ly, A.; Berger, H., et al. Maternal and Cord Blood Folate Concentrations Are Inversely Associated with Fetal DNA Hydroxymethylation, but Not DNA Methylation, in a Cohort of Pregnant Canadian Women. J Nutr 2020, 150, 202-211. [CrossRef]

- Plumptre, L.; Masih, S.P.; Ly, A.; Aufreiter, S.; Sohn, K.-J.; Croxford, R.; Lausman, A.Y.; Berger, H.; O’Connor, D.L.; Kim, Y.-I. High concentrations of folate and unmetabolized folic acid in a cohort of pregnant Canadian women and umbilical cord blood. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015, 102, 848-857. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.F.; Field, C.J.; Olstad, D.L.; Loehr, S.; Ramage, S.; McCargar, L.J.; Team, t.A.S. Use of micronutrient supplements among pregnant women in Alberta: results from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2015, 11, 497-510. [CrossRef]

- Maruvada, P.; Stover, P.J.; Mason, J.B.; Bailey, R.L.; Davis, C.D.; Field, M.S.; Finnell, R.H.; Garza, C.; Green, R.; Gueant, J.L., et al. Knowledge gaps in understanding the metabolic and clinical effects of excess folates/folic acid: a summary, and perspectives, from an NIH workshop. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 112, 1390-1403. [CrossRef]

- Fardous, A.M.; Beydoun, S.; James, A.A.; Ma, H.; Cabelof, D.C.; Unnikrishnan, A.; Heydari, A.R. The Timing and Duration of Folate Restriction Differentially Impacts Colon Carcinogenesis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 16.

- Alnabbat, K.I.; Fardous, A.M.; Shahab, A.; James, A.A.; Bahry, M.R.; Heydari, A.R. High Dietary Folic Acid Intake Is Associated with Genomic Instability in Peripheral Lymphocytes of Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, P.G. Components of the AIN-93 Diets as Improvements in the AIN-76A Diet. The Journal of Nutrition 1997, 10.1093/jn/127.5.838s. [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals,: Fourth Revised Edition, 1995; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 1995 . [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Marcu, A.; Guo, A.C.; Liang, K.; Vázquez-Fresno, R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Karu, N., et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 46, D608-D617. [CrossRef]

- Fazili, Z.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Zhang, M. Comparison of Serum Folate Species Analyzed by LC-MS/MS with Total Folate Measured by Microbiologic Assay and Bio-Rad Radioassay. Clinical Chemistry 2007, 53, 781-784. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.D.; Pirona, A.C.; Sarvin, B.; Stern, A.; Nevo-Dinur, K.; Besser, E.; Sarvin, N.; Lagziel, S.; Mukha, D.; Raz, S., et al. Tumor Reliance on Cytosolic versus Mitochondrial One-Carbon Flux Depends on Folate Availability. Cell Metab 2021, 33, 190-198.e196. [CrossRef]

- López, J.M.; Outtrim, E.L.; Fu, R.; Sutcliffe, D.J.; Torres, R.J.; Jinnah, H.A. Physiological levels of folic acid reveal purine alterations in Lesch-Nyhan disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 12071-12079. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Keating, E.; Pinto, E. The impact of folic acid supplementation on gestational and long term health: Critical temporal windows, benefits and risks. Porto Biomed J 2017, 2, 315-332. [CrossRef]

- Ledowsky, C.; Mahimbo, A.; Scarf, V.; Steel, A. Women Taking a Folic Acid Supplement in Countries with Mandatory Food Fortification Programs May Be Exceeding the Upper Tolerable Limit of Folic Acid: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.L.; Mistry, K.B.; Wang, G.; Zuckerman, B.; Wang, X. Folate Nutrition Status in Mothers of the Boston Birth Cohort, Sample of a US Urban Low-Income Population. American Journal of Public Health 2018, 108, 799-807. [CrossRef]

- Page, R.; Robichaud, A.; Arbuckle, T.E.; Fraser, W.D.; Macfarlane, A.J. Total folate and unmetabolized folic acid in the breast milk of a cross-section of Canadian women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017, 105, 1101-1109. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Lu, D.-W.; Shi, B.; Chen, H.-Q. Significant Evidence of Association Between Polymorphisms in ZNF533, Environmental Factors, and Nonsyndromic Orofacial Clefts in the Western Han Chinese Population. DNA and Cell Biology 2010, 30, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, A.J.; Lie, R.T.; Solvoll, K.; Taylor, J.; McConnaughey, D.R.; Abyholm, F.; Vindenes, H.; Vollset, S.E.; Drevon, C.A. Folic acid supplements and risk of facial clefts: national population based case-control study. Bmj 2007, 334, 464. [CrossRef]

- Bille, C.; Olsen, J.; Vach, W.; Knudsen, V.K.; Olsen, S.F.; Rasmussen, K.; Murray, J.C.; Andersen, A.M.N.; Christensen, K. Oral clefts and life style factors — A case-cohort study based on prospective Danish data. European Journal of Epidemiology 2007, 22, 173-181. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.-L.; Shi, B.; Chen, C.-H.; Shi, J.-Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, X. Maternal malnutrition, environmental exposure during pregnancy and the risk of non-syndromic orofacial clefts. Oral Diseases 2011, 17, 584-589. [CrossRef]

- Wehby, G.; Félix, T.; Goco, N.; Richieri-Costa, A.; Chakraborty, H.; Souza, J.; Pereira, R.; Padovani, C.; Moretti-Ferreira, D.; Murray, J. High Dosage Folic Acid Supplementation, Oral Cleft Recurrence and Fetal Growth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2013, 10, 590-605. [CrossRef]

- Little, J.; Gilmour, M.; Mossey, P.A.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Cardy, A.; Clayton-Smith, J.; Fryer, A.E. Folate and Clefts of the Lip and Palate—A U.K.-Based Case-Control Study: Part I: Dietary and Supplemental Folate. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 2008, 45, 420-427. [CrossRef]

- Rozendaal, A.M.; Van Essen, A.J.; Te Meerman, G.J.; Bakker, M.K.; Van Der Biezen, J.J.; Goorhuis-Brouwer, S.M.; Vermeij-Keers, C.; De Walle, H.E.K. Periconceptional folic acid associated with an increased risk of oral clefts relative to non-folate related malformations in the Northern Netherlands: a population based case-control study. European Journal of Epidemiology 2013, 28, 875-887. [CrossRef]

- Lassi, Z.S.; Salam, R.A.; Haider, B.A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Folic acid supplementation during pregnancy for maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, 10.1002/14651858.CD006896.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Chatzi, L.; Papadopoulou, E.; Koutra, K.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Georgiou, V.; Stratakis, N.; Lebentakou, V.; Karachaliou, M.; Vassilaki, M.; Kogevinas, M. Effect of high doses of folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy on child neurodevelopment at 18 months of age: the mother-child cohort ‘Rhea’ study in Crete, Greece. Public health nutrition 2012, 15, 1728-1736. [CrossRef]

- Csáky-Szunyogh, M.; Vereczkey, A.; Kósa, Z.; Gerencsér, B.; Czeizel, A.E. Risk Factors in the Origin of Congenital Left-Ventricular Outflow-Tract Obstruction Defects of the Heart: A Population-Based Case–Control Study. Pediatric Cardiology 2014, 35, 108-120. [CrossRef]

- Vereczkey, A.; Kósa, Z.; Csáky-Szunyogh, M.; Czeizel, A.E. Isolated atrioventricular canal defects: Birth outcomes and risk factors: A population-based hungarian case–control study, 1980–1996. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2013, 97, 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Xu, P.; Fu, Z.; Gu, X.; Li, H.; Cui, X.; You, L.; Zhu, L.; Ji, C.; Guo, X. Association of maternal folate status in the second trimester of pregnancy with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Food Science & Nutrition 2019, 7, 3759-3765. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ge, X.; Huang, K.; Mao, L.; Yan, S.; Xu, Y.; Huang, S.; Hao, J.; Zhu, P.; Niu, Y., et al. Folic Acid Supplement Intake in Early Pregnancy Increases Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Evidence From a Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, e36-e37. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Sha, T.; Gao, X.; He, Q.; Wu, X.; Tian, Q.; Yang, F.; Tang, C.; Wu, X.; Xie, Q., et al. The Associations between the Duration of Folic Acid Supplementation, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Adverse Birth Outcomes based on a Birth Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 4511.

- Huang, L.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, H.; Xu, D., et al. Duration of periconceptional folic acid supplementation and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2019, 28, 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.M.; Parker, S.E.; Benedum, C.M.; Mitchell, A.A.; Tinker, S.C.; Werler, M.M. Periconceptional folic acid and risk for neural tube defects among higher risk pregnancies. Birth Defects Res 2019, 111, 1501-1512. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, M.; Dou, Y.; Sun, X.; Huang, G., et al. Association of Maternal Folate and Vitamin B12 in Early Pregnancy With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hou, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J., et al. Joint effects of folate and vitamin B12 imbalance with maternal characteristics on gestational diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes 2019, 11, 744-751. [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Valero, M.; Navarrete-Muoz, E.M.; Rebagliato, M.; Iñiguez, C.; Murcia, M.; Marco, A.; Ballester, F.; Vioque, J. Periconceptional folic acid supplementation and anthropometric measures at birth in a cohort of pregnant women in Valencia, Spain. British Journal of Nutrition 2011, 105, 1352-1360. [CrossRef]

- Michels, A.; Bakkali, N.E.; Bastiaenen, C.H.; De Bie, R.A.; Colla, C.G.; Van der Hulst, R.R. Periconceptional Folic Acid Use and the Prevalence of Positional Plagiocephaly. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2008, 19, 37-39. [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Sajjadi, S.; Tomar, A.S.; Saffari, A.; Fall, C.H.D.; Prentice, A.M.; Shrestha, S.; Issarapu, P.; Yadav, D.K.; Kaur, L., et al. Candidate genes linking maternal nutrient exposure to offspring health via DNA methylation: a review of existing evidence in humans with specific focus on one-carbon metabolism. Int J Epidemiol 2018, 47, 1910-1937. [CrossRef]

- Callinan, P.A.; Feinberg, A.P. The emerging science of epigenomics. Hum Mol Genet 2006, 15 Spec No 1, R95-101. [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Cooper, C.; Thornburg, K.L. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008, 359, 61-73. [CrossRef]

- Mikael, L.G.; Deng, L.; Paul, L.; Selhub, J.; Rozen, R. Moderately high intake of folic acid has a negative impact on mouse embryonic development. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2013, 97, 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Chadman, K.K.; Kuizon, S.; Buenaventura, D.; Stapley, N.W.; Ruocco, F.; Begum, U.; Guariglia, S.R.; Brown, W.T.; Junaid, M.A. Increasing maternal or post-weaning folic acid alters gene expression and moderately changes behavior in the offspring. PLoS ONE 2014, 10.1371/journal.pone.0101674. [CrossRef]

- Whitrow, M.J.; Moore, V.M.; Rumbold, A.R.; Davies, M.J. Effect of Supplemental Folic Acid in Pregnancy on Childhood Asthma: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 2009, 170, 1486-1493. [CrossRef]

- Burdge, G.C.; Lillycrop, K.A. Folic acid supplementation in pregnancy: Are there devils in the detail? Br J Nutr 2012, 108, 1924-1930. [CrossRef]

- Haggarty, P.; Hoad, G.; Campbell, D.M.; Horgan, G.W.; Piyathilake, C.; McNeill, G. Folate in pregnancy and imprinted gene and repeat element methylation in the offspring. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012, 97, 94-99. [CrossRef]

- Hoyo, C.; Murtha, A.P.; Schildkraut, J.M.; Forman, M.R.; Calingaert, B.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Kurtzberg, J.; Jirtle, R.L.; Murphy, S.K. Folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy in the Newborn Epigenetics STudy (NEST). BMC Public Health 2011, 10.1186/1471-2458-11-46. [CrossRef]

- Hoyo, C.; Murtha, A.P.; Schildkraut, J.M.; Jirtle, R.L.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Forman, M.R.; Iversen, E.S.; Kurtzberg, J.; Overcash, F.; Huang, Z., et al. Methylation variation at IGF2 differentially methylated regions and maternal folic acid use before and during pregnancy. Epigenetics 2011, 6, 928-936. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaveni, G.V.; Veena, S.R.; Karat, S.C.; Yajnik, C.S.; Fall, C.H.D. Association between maternal folate concentrations during pregnancy and insulin resistance in Indian children. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.H.; Liu, Y.J.; Retnakaran, R.; Macfarlane, A.J.; Hamilton, J.; Smith, G.; Walker, M.C.; Wen, S.W. Maternal folate status and obesity/insulin resistance in the offspring: a systematic review. International Journal of Obesity 2016, 40, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Sie, K.K.Y.; Li, J.; Ly, A.; Sohn, K.-J.; Croxford, R.; Kim, Y.-I. Effect of maternal and postweaning folic acid supplementation on global and gene-specific DNA methylation in the liver of the rat offspring. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2013, 57, 677-685. [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.; Chan, D.; Landry, M.; Angle, C.; Martel, J.; Trasler, J. Impact of mothers’ early life exposure to low or high folate on progeny outcome and DNA methylation patterns. Environmental Epigenetics 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, R.; Pannia, E.; Kubant, R.; Wasek, B.; Bottiglieri, T.; Malysheva, O.V.; Caudill, M.A.; Anderson, G.H. Choline and Folic Acid in Diets Consumed during Pregnancy Interact to Program Food Intake and Metabolic Regulation of Male Wistar Rat Offspring. The Journal of Nutrition 2021, 151, 857-865. [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.E.; Sánchez-Hernández, D.; Reza-López, S.A.; Huot, P.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Anderson, G.H. High folate gestational and post-weaning diets alter hypothalamic feeding pathways by DNA methylation in Wistar rat offspring. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 710-719. [CrossRef]

- Tojal, A.; Neves, C.; Veiga, H.; Ferreira, S.; Rodrigues, I.; Martel, F.; Calhau, C.; Negrão, R.; Keating, E. Perigestational high folic acid: impact on offspring’s peripheral metabolic response. Food & Function 2019, 10, 7216-7226. [CrossRef]

- Kintaka, Y.; Wada, N.; Shioda, S.; Nakamura, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Mochizuki, K. Excessive folic acid supplementation in pregnant mice impairs insulin secretion and induces the expression of genes associated with fatty liver in their offspring. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03597. [CrossRef]

- Morakinyo, A.O.; Samuel, T.A.; Awobajo, F.O.; Oludare, G.O.; Mofolorunso, A. High-Dose Perinatal Folic-Acid Supplementation Alters Insulin Sensitivity in Sprague-Dawley Rats and Diminishes the Expression of Adiponectin. J Diet Suppl 2019, 16, 14-26. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, Y.; Sun, X.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Maternal high folic acid supplement promotes glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in male mouse offspring fed a high-fat diet. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 10.3390/ijms15046298. [CrossRef]

- Keating, E.; Correia-Branco, A.; Araújo, J.R.; Meireles, M.; Fernandes, R.; Guardão, L.; Guimarães, J.T.; Martel, F.; Calhau, C. Excess perigestational folic acid exposure induces metabolic dysfunction in post-natal life. Journal of Endocrinology 2015, 224, 245-259. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, P.T.; Manziello, A.; Howard, J.; Palbykin, B.; Runyan, R.B.; Selmin, O. Gene expression profiling in the fetal cardiac tissue after folate and low-dose trichloroethylene exposure. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2010, 88, 111-127. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, A.; Irwin, R.E.; McNulty, H.; Strain, J.J.; Lees-Murdock, D.J.; McNulty, B.A.; Ward, M.; Walsh, C.P.; Pentieva, K. Gene-specific DNA methylation in newborns in response to folic acid supplementation during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy: epigenetic analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 107, 566-575. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R.E.; Pentieva, K.; Cassidy, T.; Lees-Murdock, D.J.; McLaughlin, M.; Prasad, G.; McNulty, H.; Walsh, C.P. The interplay between DNA methylation, folate and neurocognitive development. Epigenomics 2016, 8, 863-879. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Liu, S.M.; Zhang, Y.Z. Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation Mediates Offspring Health via DNA Methylation. Reprod Sci 2020, 27, 963-976. [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, J.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, N.; Liu, F. Excess Folic Acid Supplementation Before and During Pregnancy and Lactation Activates Fos Gene Expression and Alters Behaviors in Male Mouse Offspring. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 313. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Chadman, K.K.; Kuizon, S.; Buenaventura, D.; Stapley, N.W.; Ruocco, F.; Begum, U.; Guariglia, S.R.; Brown, W.T.; Junaid, M.A. Increasing Maternal or Post-Weaning Folic Acid Alters Gene Expression and Moderately Changes Behavior in the Offspring. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e101674. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Kuizon, S.; Brown, W.T.; Junaid, M.A. DNA Methylation Profiling at Single-Base Resolution Reveals Gestational Folic Acid Supplementation Influences the Epigenome of Mouse Offspring Cerebellum. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2016, 10. [CrossRef]

- Huot, P.S.; Ly, A.; Szeto, I.M.; Reza-López, S.A.; Cho, D.; Kim, Y.I.; Anderson, G.H. Maternal and postweaning folic acid supplementation interact to influence body weight, insulin resistance, and food intake regulatory gene expression in rat offspring in a sex-specific manner. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016, 41, 411-420. [CrossRef]

- Soubry, A. POHaD: why we should study future fathers. Environmental Epigenetics 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Calvo, N.; Mínguez-Alarcón, L.; Gaskins, A.J.; Nassan, F.L.; Williams, P.L.; Souter, I.; Hauser, R.; Chavarro, J.E. Paternal preconception folate intake in relation to gestational age at delivery and birthweight of newborns conceived through assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online 2019, 39, 835-843. [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.; Chan, D.; Aarabi, M.; Landry, M.; Behan, N.A.; MacFarlane, A.J.; Trasler, J. Intergenerational impact of paternal lifetime exposures to both folic acid deficiency and supplementation on reproductive outcomes and imprinted gene methylation. Molecular Human Reproduction 2017, 23, 461-477. [CrossRef]

- Aarabi, M.; Christensen, K.E.; Chan, D.; Leclerc, D.; Landry, M.; Ly, L.; Rozen, R.; Trasler, J. Testicular MTHFR deficiency may explain sperm DNA hypomethylation associated with high dose folic acid supplementation. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, 1123-1135. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Martel, J.; Karahan, G.; Angle, C.; Behan, N.A.; Chan, D.; Macfarlane, A.J.; Trasler, J.M. Moderate maternal folic acid supplementation ameliorates adverse embryonic and epigenetic outcomes associated with assisted reproduction in a mouse model. Human Reproduction 2019, 34, 851-862. [CrossRef]

- McNulty, H.; Rollins, M.; Cassidy, T.; Caffrey, A.; Marshall, B.; Dornan, J.; McLaughlin, M.; McNulty, B.A.; Ward, M.; Strain, J.J., et al. Effect of continued folic acid supplementation beyond the first trimester of pregnancy on cognitive performance in the child: a follow-up study from a randomized controlled trial (FASSTT Offspring Trial). BMC Medicine 2019, 17, 196. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, A.; McNulty, H.; Rollins, M.; Prasad, G.; Gaur, P.; Talcott, J.B.; Witton, C.; Cassidy, T.; Marshall, B.; Dornan, J., et al. Effects of maternal folic acid supplementation during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy on neurocognitive development in the child: an 11-year follow-up from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Medicine 2021, 19, 73. [CrossRef]

- Valera-Gran, D.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; Garcia de la Hera, M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Tardón, A.; Ibarluzea, J.; Balluerka, N.; Murcia, M.; González-Safont, L.; Romaguera, D., et al. Effect of maternal high dosages of folic acid supplements on neurocognitive development in children at 4-5 y of age: the prospective birth cohort Infancia y Medio Ambiente (INMA) study. Am J Clin Nutr 2017, 106, 878-887. [CrossRef]

- Compañ Gabucio, L.M.; García de la Hera, M.; Torres Collado, L.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Tardón, A.; Guxens, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Rebagliato, M.; Murcia, M.; Ibarluzea, J., et al. The Use of Lower or Higher Than Recommended Doses of Folic Acid Supplements during Pregnancy Is Associated with Child Attentional Dysfunction at 4–5 Years of Age in the INMA Project. Nutrients 2021, 13, 327.

- Egorova, O.; Myte, R.; Schneede, J.; Hägglöf, B.; Bölte, S.; Domellöf, E.; Ivars A’roch, B.; Elgh, F.; Ueland, P.M.; Silfverdal, S.A. Maternal blood folate status during early pregnancy and occurrence of autism spectrum disorder in offspring: a study of 62 serum biomarkers. Mol Autism 2020, 11, 7. [CrossRef]

- Valera-Gran, D.; García de la Hera, M.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.M.; Fernandez-Somoano, A.; Tardón, A.; Julvez, J.; Forns, J.; Lertxundi, N.; Ibarluzea, J.M.; Murcia, M., et al. Folic Acid Supplements During Pregnancy and Child Psychomotor Development After the First Year of Life. JAMA Pediatrics 2014, 168, e142611-e142611. [CrossRef]

- Wiens, D.; Desoto, M. Is High Folic Acid Intake a Risk Factor for Autism?—A Review. Brain Sciences 2017, 7, 149. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Riley, A.W.; Volk, H.; Caruso, D.; Hironaka, L.; Sices, L.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Ji, Y.; Brucato, M., et al. Maternal Multivitamin Intake, Plasma Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels and Autism Spectrum Disorder Risk in Offspring. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2018, 32, 100-111. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zou, M.; Sun, C.; Wu, L.; Chen, W.-X. Prenatal Folic Acid Supplements and Offspring’s Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. J Autism Dev Disord 2022, 52, 522-539. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Selhub, J.; Paul, L.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Hong, X.; Zuckerman, B.; Fallin, M.D.; Wang, X. A prospective birth cohort study on cord blood folate subtypes and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 112, 1304-1317. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, W.; Wu, Q.; Lin, H.; Lu, Z.; Shen, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, F., et al. Excess Folic Acid Supplementation before and during Pregnancy and Lactation Alters Behaviors and Brain Gene Expression in Female Mouse Offspring. Nutrients 2021, 14, 66. [CrossRef]

- Harlan De Crescenzo, A.; Panoutsopoulos, A.A.; Tat, L.; Schaaf, Z.; Racherla, S.; Henderson, L.; Leung, K.-Y.; Greene, N.D.E.; Green, R.; Zarbalis, K.S. Deficient or Excess Folic Acid Supply During Pregnancy Alter Cortical Neurodevelopment in Mouse Offspring. Cerebral Cortex 2020, 31, 635-649. [CrossRef]

- Cosín-Tomás, M.; Luan, Y.; Leclerc, D.; Malysheva, O.V.; Lauzon, N.; Bahous, R.H.; Christensen, K.E.; Caudill, M.A.; Rozen, R. Moderate Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Mice Results in Behavioral Alterations in Offspring with Sex-Specific Changes in Methyl Metabolism. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1716.

- Henzel, K.S.; Ryan, D.P.; Schröder, S.; Weiergräber, M.; Ehninger, D. High-dose maternal folic acid supplementation before conception impairs reversal learning in offspring mice. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 3098. [CrossRef]

- Girotto, F.; Scott, L.; Avchalumov, Y.; Harris, J.; Iannattone, S.; Drummond-Main, C.; Tobias, R.; Bello-Espinosa, L.; Rho, J.M.; Davidsen, J., et al. High dose folic acid supplementation of rats alters synaptic transmission and seizure susceptibility in offspring. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Pickell, L.; Brown, K.; Li, D.; Wang, X.L.; Deng, L.; Wu, Q.; Selhub, J.; Luo, L.; Jerome-Majewska, L.; Rozen, R. High intake of folic acid disrupts embryonic development in mice. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2011, 91, 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, D.; Wu, R.; Shi, R.; Shen, X.; Jin, N.; Gu, J.; Gu, J.H.; Liu, F.; Chu, D. Excess folic acid supplementation before and during pregnancy and lactation activates β-catenin in the brain of male mouse offspring. Brain Res Bull 2022, 178, 133-143. [CrossRef]

- Cianciulli, A.; Salvatore, R.; Porro, C.; Trotta, T.; Panaro, M.A. Folic Acid Is Able to Polarize the Inflammatory Response in LPS Activated Microglia by Regulating Multiple Signaling Pathways. Mediators Inflamm 2016, 2016, 5240127. [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, J.V.C.; Ribeiro, M.R.; Luna, R.C.P.; Lima, R.P.A.; Nascimento, R.; Monteiro, M.; Lima, K.Q.F.; Fechine, C.; Oliveira, N.F.P.; Persuhn, D.C., et al. Food Intervention with Folate Reduces TNF-α and Interleukin Levels in Overweight and Obese Women with the MTHFR C677T Polymorphism: A Randomized Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Lucock, M.; Scarlett, C.J.; Veysey, M.; Beckett, E.L. Folate and Inflammation – links between folate and features of inflammatory conditions. Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism 2019, 18, 100104. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Jabir, M.S.; Liu, X.; Cui, W.; Li, D. Associations between Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 382.

- Lazzerini, P.E.; Capecchi, P.L.; Selvi, E.; Lorenzini, S.; Bisogno, S.; Galeazzi, M.; Laghi Pasini, F. Hyperhomocysteinemia, inflammation and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews 2007, 6, 503-509. [CrossRef]

- Asbaghi, O.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Bagheri, R.; Moosavian, S.P.; Nazarian, B.; Afrisham, R.; Kelishadi, M.R.; Wong, A.; Dutheil, F.; Suzuki, K., et al. Effects of Folic Acid Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers: A Grade-Assessed Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2327.

- Troen, A.M.; Mitchell, B.; Sorensen, B.; Wener, M.H.; Johnston, A.; Wood, B.; Selhub, J.; McTiernan, A.; Yasui, Y.; Oral, E., et al. Unmetabolized folic acid in plasma is associated with reduced natural killer cell cytotoxicity among postmenopausal women. J Nutr 2006, 136, 189-194. [CrossRef]

- Crider, K.S.; Cordero, A.M.; Qi, Y.P.; Mulinare, J.; Dowling, N.F.; Berry, R.J. Prenatal folic acid and risk of asthma in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 98, 1272-1281. [CrossRef]

- Whitrow, M.J.; Moore, V.M.; Rumbold, A.R.; Davies, M.J. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2009, 170, 1486-1493. [CrossRef]

- Zetstra-van der Woude, P.A.; De Walle, H.E.; Hoek, A.; Bos, H.J.; Boezen, H.M.; Koppelman, G.H.; de Jong-van den Berg, L.T.; Scholtens, S. Maternal high-dose folic acid during pregnancy and asthma medication in the offspring. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014, 23, 1059-1065. [CrossRef]

- Veeranki, S.P.; Gebretsadik, T.; Mitchel, E.F.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Hartert, T.V.; Cooper, W.O.; Dupont, W.D.; Dorris, S.L.; Hartman, T.J.; Carroll, K.N. Maternal Folic Acid Supplementation During Pregnancy and Early Childhood Asthma. Epidemiology 2015, 26, 934-941. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, L.; Bi, M.; Jia, X.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. High dose of maternal folic acid supplementation is associated to infant asthma. Food Chem Toxicol 2015, 75, 88-93. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Zhang, J. Periconceptional folic acid supplementation is a risk factor for childhood asthma: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Magdelijns, F.J.; Mommers, M.; Penders, J.; Smits, L.; Thijs, C. Folic acid use in pregnancy and the development of atopy, asthma, and lung function in childhood. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e135-144. [CrossRef]

- Martinussen, M.P.; Risnes, K.R.; Jacobsen, G.W.; Bracken, M.B. Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy and asthma in children aged 6 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012, 206, 72.e71-77. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.K.; Sharma, S.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Weiss, S.T.; Oken, E.; Gillman, M.W.; Gold, D.R.; DeMeo, D.L.; Litonjua, A.A. Folic Acid in Pregnancy and Childhood Asthma: A US Cohort. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2018, 57, 421-427. [CrossRef]

- Vereen, S.; Gebretsadik, T.; Johnson, N.; Hartman, T.J.; Veeranki, S.P.; Piyathilake, C.; Mitchel, E.F.; Kocak, M.; Cooper, W.O.; Dupont, W.D., et al. Association Between Maternal 2nd Trimester Plasma Folate Levels and Infant Bronchiolitis. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2019, 23, 164-172. [CrossRef]

- Veeranki, S.P.; Gebretsadik, T.; Dorris, S.L.; Mitchel, E.F.; Hartert, T.V.; Cooper, W.O.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Dupont, W.; Hartman, T.J.; Carroll, K.N. Association of Folic Acid Supplementation During Pregnancy and Infant Bronchiolitis. American Journal of Epidemiology 2014, 179, 938-946. [CrossRef]

- Håberg, S.E.; London, S.J.; Stigum, H.; Nafstad, P.; Nystad, W. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and early childhood respiratory health. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2009, 94, 180-184. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Kocak, M.; Hartman, T.J.; Vereen, S.; Adgent, M.; Piyathilake, C.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Carroll, K.N. Association of prenatal folate status with early childhood wheeze and atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2018, 29, 144-150. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xing, Y.; Yu, X.; Dou, Y.; Ma, D. Effect of Folic Acid Intake on Infant and Child Allergic Diseases: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Timmermans, S.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H.; Steegers, E.A.; de Jongste, J.C.; Moll, H.A. High Circulating Folate and Vitamin B-12 Concentrations in Women During Pregnancy Are Associated with Increased Prevalence of Atopic Dermatitis in Their Offspring. The Journal of Nutrition 2012, 142, 731-738. [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, J.A.; West, C.; McCarthy, S.; Metcalfe, J.; Meldrum, S.; Oddy, W.H.; Tulic, M.K.; D’Vaz, N.; Prescott, S.L. The relationship between maternal folate status in pregnancy, cord blood folate levels, and allergic outcomes in early childhood. Allergy 2012, 67, 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Kominsky, D.J.; Keely, S.; MacManus, C.F.; Glover, L.E.; Scully, M.; Collins, C.B.; Bowers, B.E.; Campbell, E.L.; Colgan, S.P. An Endogenously Anti-Inflammatory Role for Methylation in Mucosal Inflammation Identified through Metabolite Profiling. The Journal of Immunology 2011, 186, 6505-6514. [CrossRef]

- Schaible, T.D.; Harris, R.A.; Dowd, S.E.; Smith, C.W.; Kellermayer, R. Maternal methyl-donor supplementation induces prolonged murine offspring colitis susceptibility in association with mucosal epigenetic and microbiomic changes. Human Molecular Genetics 2011, 20, 1687-1696. [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Nagy-Szakal, D.; Dowd, S.E.; Szigeti, R.G.; Smith, C.W.; Kellermayer, R. Prenatal Methyl-Donor Supplementation Augments Colitis in Young Adult Mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e73162. [CrossRef]

- Pannia, E.; Cho, C.E.; Kubant, R.; Sánchez-Hernández, D.; Huot, P.S.P.; Chatterjee, D.; Fleming, A.; Anderson, G.H. A high multivitamin diet fed to Wistar rat dams during pregnancy increases maternal weight gain later in life and alters homeostatic, hedonic and peripheral regulatory systems of energy balance. Behavioural Brain Research 2015, 278, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Alnabbat, K.I.; Fardous, A.M.; Cabelof, D.C.; Heydari, A.R. Excessive Folic Acid Mimics Folate Deficiency in Human Lymphocytes. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2022, 44, 1452-1462.

- Alnabbat, K.I.; Fardous, A.M.; Shahab, A.; James, A.A.; Bahri, M.R.; Heydari, A.R. High Dietary Folic Acid Intake is Associated with Genomic instability in Peripheral Lymphocytes of Healthy Adults. Preprints 2022. [CrossRef]

- Courtemanche, C.; Huang, A.C.; Elson-Schwab, I.; Kerry, N.; Ng, B.Y.; Ames, B.N. Folate deficiency and ionizing radiation cause DNA breaks in primary human lymphocytes: a comparison. FASEB J 2004, 18, 209-211. [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.B.; Dickstein, A.; Jacques, P.F.; Haggarty, P.; Selhub, J.; Dallal, G.; Rosenberg, I.H. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007, 16, 1325-1329. [CrossRef]

- F, W.; K, W.; Y, L.; R, S.; Y, W.; X, Z.; M, S.; L, L.; Sa, S.-W.; El, G., et al. Association of folate intake and colorectal cancer risk in the postfortification era in US women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2021, 114, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Ebbing, M.; Bønaa, K.H.; Nygård, O.; Arnesen, E.; Ueland, P.M.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Rasmussen, K.; Njølstad, I.; Refsum, H.; Nilsen, D.W., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and vitamin B12. Jama 2009, 302, 2119-2126. [CrossRef]

- Wien, T.N.; Pike, E.; Wisloff, T.; Staff, A.; Smeland, S.; Klemp, M. Cancer risk with folic acid supplements: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000653. [CrossRef]

- Oliai Araghi, S.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; van Dijk, S.C.; Swart, K.M.A.; van Laarhoven, H.W.; van Schoor, N.M.; de Groot, L.; Lemmens, V.; Stricker, B.H.; Uitterlinden, A.G., et al. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Supplementation and the Risk of Cancer: Long-term Follow-up of the B Vitamins for the Prevention of Osteoporotic Fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019, 28, 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Cole, B.F.; Baron, J.A.; Sandler, R.S.; Haile, R.W.; Ahnen, D.J.; Bresalier, R.S.; McKeown-Eyssen, G.; Summers, R.W.; Rothstein, R.I.; Burke, C.A., et al. Folic Acid for the Prevention of Colorectal Adenomas. JAMA 2007, 10.1001/jama.297.21.2351. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.C.; Grau, M.V.; Haile, R.W.; Sandler, R.S.; Summers, R.W.; Bresalier, R.S.; Burke, C.A.; McKeown-Eyssen, G.E.; Baron, J.A. Folic acid and risk of prostate cancer: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2009, 10.1093/jnci/djp019. [CrossRef]

- Liss, M.A.; Ashcraft, K.; Satsangi, A.; Bacich, D. Rise in serum folate after androgen deprivation associated with worse prostate cancer-specific survival. Urol Oncol 2020, 38, 682.e621-682.e627. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; He, J.; Li, C.; Deng, Z.; Chang, H. Folate intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and up-to-date meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Cancer Prev 2023, 32, 103-112. [CrossRef]

- Pieroth, R.; Paver, S.; Day, S.; Lammersfeld, C. Folate and Its Impact on Cancer Risk. Current Nutrition Reports 2018, 7, 70-84. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Sohn, K.J.; Medline, A.; Ash, C.; Gallinger, S.; Kim, Y.I. Chemopreventive effects of dietary folate on intestinal polyps in Apc+/- Msh2-/- Mice. Cancer Research 2000.

- Le Leu, R.K.; Young, G.P.; McIntosh, G.H. Folate deficiency reduces the development of colorectal cancer in rats. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 2261-2265. [CrossRef]

- Lindzon, G.M.; Medline, A.; Sohn, K.J.; Depeint, F.; Croxford, R.; Kim, Y.I. Effect of folic acid supplementation on the progression of colorectal aberrant crypt foci. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1536-1543. [CrossRef]

- Galeone, C.; Edefonti, V.; Parpinel, M.; Leoncini, E.; Matsuo, K.; Talamini, R.; Olshan, A.F.; Zevallos, J.P.; Winn, D.M.; Jayaprakash, V., et al. Folate intake and the risk of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer: a pooled analysis within the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Int J Cancer 2015, 136, 904-914. [CrossRef]

- Tio, M.; Andrici, J.; Cox, M.R.; Eslick, G.D. Folate intake and the risk of upper gastrointestinal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 29, 250-258. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zeng, J.; Liu, C.; Gu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Chang, H. Folate Intake and Risk of Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Updated Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. Dig Dis Sci 2021, 66, 2368-2379. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zou, Y.; Liu, C.; Fu, H.; Chang, H. Folate Intake and Risk of Urothelial Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. Nutr Cancer 2022, 74, 1593-1605. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shui, B. Folate intake and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2014, 65, 286-292. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.W.; Hou, A.J.; Gao, H.F.; Zhou, Y.H. Association between folate intake and the risk of lung cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93465. [CrossRef]

- Stanisławska-Sachadyn, A.; Borzyszkowska, J.; Krzemiński, M.; Janowicz, A.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Jassem, J.; Rzyman, W.; Limon, J. Folate/homocysteine metabolism and lung cancer risk among smokers. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0214462. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, P.; Hu, P.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Chu, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H. Folate intake and MTHFR polymorphism C677T is not associated with ovarian cancer risk: evidence from the meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 6547-6560. [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y. Folate intake and the risk of endometrial cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 85176-85184. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Shi, W.W.; Gao, H.F.; Zhou, L.; Hou, A.J.; Zhou, Y.H. Folate intake and the risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100044. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Chu, R.; Wang, H. Higher dietary folate intake reduces the breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2014, 110, 2327-2338. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Gu, Y.; Fu, H.; Liu, C.; Zou, Y.; Chang, H. Association Between One-carbon Metabolism-related Vitamins and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. Clin Breast Cancer 2020, 20, e469-e480. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wang, K.; Ye, F.; Lei, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, G.; Chang, H. Folate intake and the risk of breast cancer: an up-to-date meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Clin Nutr 2019, 73, 1657-1660. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, R.; Ma, H.; Cabelof, D.C. Folate and colorectal cancer in rodents: A model of DNA repair deficiency. 2012; 10.1155/2012/105949.

- Hansen, M.F.; Jensen, S.Ø.; Füchtbauer, E.-M.; Martensen, P.M. High folic acid diet enhances tumour growth in PyMT-induced breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer 2017, 116, 752-761. [CrossRef]

- Ly, A.; Lee, H.; Chen, J.; Sie, K.K.Y.; Renlund, R.; Medline, A.; Sohn, K.J.; Croxford, R.; Thompson, L.U.; Kim, Y.I. Effect of maternal and postweaning folic acid supplementation on mammary tumor risk in the offspring. Cancer Research 2011, 71, 988-997. [CrossRef]

- Deghan Manshadi, S.; Ishiguro, L.; Sohn, K.-J.; Medline, A.; Renlund, R.; Croxford, R.; Kim, Y.-I. Folic Acid Supplementation Promotes Mammary Tumor Progression in a Rat Model. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e84635. [CrossRef]

- Been, R.A.; Ross, J.A.; Nagel, C.W.; Hooten, A.J.; Langer, E.K.; DeCoursin, K.J.; Marek, C.A.; Janik, C.L.; Linden, M.A.; Reed, R.C., et al. Perigestational dietary folic acid deficiency protects against medulloblastoma formation in a mouse model of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Nutr Cancer 2013, 65, 857-865. [CrossRef]

- Rycyna, K.J.; Bacich, D.J.; O’Keefe, D.S. Opposing roles of folate in prostate cancer. Urology 2013, 82, 1197-1203. [CrossRef]

- Savini, C.; Yang, R.; Savelyeva, L.; Göckel-Krzikalla, E.; Hotz-Wagenblatt, A.; Westermann, F.; Rösl, F. Folate Repletion after Deficiency Induces Irreversible Genomic and Transcriptional Changes in Human Papillomavirus Type 16 (HPV16)-Immortalized Human Keratinocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tang, Y.S.; Kusumanchi, P.; Stabler, S.P.; Zhang, Y.; Antony, A.C. Folate Deficiency Facilitates Genomic Integration of Human Papillomavirus Type 16 DNA In Vivo in a Novel Mouse Model for Rapid Oncogenic Transformation of Human Keratinocytes. J Nutr 2018, 148, 389-400. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Ali, T.; Kaur, J. Folic acid depletion as well as oversupplementation helps in the progression of hepatocarcinogenesis in HepG2 cells. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 16617. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Dong, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, D.; Sun, H.; Han, L. Associations of dietary folate, vitamin B6 and B12 intake with cardiovascular outcomes in 115664 participants: a large UK population-based cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 2022, 10.1038/s41430-022-01206-2. [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wan, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Z. Intakes of Folate, Vitamin B6, and Vitamin B12 in Relation to All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A National Population-Based Cohort. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Muka, T.; Troup, J.; Hu, F.B. Folic Acid Supplementation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bønaa, K.H.; Njølstad, I.; Ueland, P.M.; Schirmer, H.; Tverdal, A.; Steigen, T.; Wang, H.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Arnesen, E.; Rasmussen, K. Homocysteine Lowering and Cardiovascular Events after Acute Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 2006, 354, 1578-1588. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Li, Q.; He, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Liang, M.; Wang, X., et al. Relationship of several serum folate forms with the risk of mortality: A prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 4255-4262. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Dong, B.; Wang, Z. Serum folate concentrations and all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality: A cohort study based on 1999–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). International Journal of Cardiology 2016, 219, 136-142. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.V.; Schooling, C.M.; Zhao, J.X. The effects of folate supplementation on glucose metabolism and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Epidemiol 2018, 28, 249-257.e241. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.T.; Lee, M.; Hong, K.S.; Ovbiagele, B.; Saver, J.L. Efficacy of folic acid supplementation in cardiovascular disease prevention: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Intern Med 2012, 23, 745-754. [CrossRef]

- Pannia, E.; Hammoud, R.; Simonian, R.; Arning, E.; Ashcraft, P.; Wasek, B.; Bottiglieri, T.; Pausova, Z.; Kubant, R.; Anderson, G.H. [6S]-5-Methyltetrahydrofolic Acid and Folic Acid Pregnancy Diets Differentially Program Metabolic Phenotype and Hypothalamic Gene Expression of Wistar Rat Dams Post-Birth. Nutrients 2020, 13, 48. [CrossRef]

- Dose-dependent effects of folic acid on blood concentrations of homocysteine: a meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 82, 806-812. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Q.; Jia, M.; Zheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, E. Hypercysteinemia promotes atherosclerosis by reducing protein S-nitrosylation. Biomed Pharmacother 2015, 70, 253-259. [CrossRef]

- Kalita, J.; Kumar, G.; Bansal, V.; Misra, U.K. Relationship of homocysteine with other risk factors and outcome of ischemic stroke. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009, 111, 364-367. [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, F.; Brombo, G.; Magon, S.; Zuliani, G. Cognitive Status According to Homocysteine and B-Group Vitamins in Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015, 63, 1158-1163. [CrossRef]

- Yajnik, C.S.; Chandak, G.R.; Joglekar, C.; Katre, P.; Bhat, D.S.; Singh, S.N.; Janipalli, C.S.; Refsum, H.; Krishnaveni, G.; Veena, S., et al. Maternal homocysteine in pregnancy and offspring birthweight: epidemiological associations and Mendelian randomization analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014, 43, 1487-1497. [CrossRef]

- den Heijer, M.; Brouwer, I.A.; Bos, G.M.; Blom, H.J.; van der Put, N.M.; Spaans, A.P.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Thomas, C.M.; Haak, H.L.; Wijermans, P.W., et al. Vitamin supplementation reduces blood homocysteine levels: a controlled trial in patients with venous thrombosis and healthy volunteers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998, 18, 356-361. [CrossRef]

- van der Griend, R.; Biesma, D.H.; Haas, F.J.; Faber, J.A.; Duran, M.; Meuwissen, O.J.; Banga, J.D. The effect of different treatment regimens in reducing fasting and postmethionine-load homocysteine concentrations. J Intern Med 2000, 248, 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Tighe, P.; Ward, M.; McNulty, H.; Finnegan, O.; Dunne, A.; Strain, J.; Molloy, A.M.; Duffy, M.; Pentieva, K.; Scott, J.M. A dose-finding trial of the effect of long-term folic acid intervention: implications for food fortification policy. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 93, 11-18. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tian, D.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Ge, M.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, W. Efficacy of Folic Acid Therapy in Patients with Hyperhomocysteinemia. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2017, 36, 528-532. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, E.H. What is the safe upper intake level of folic acid for the nervous system? Implications for folic acid fortification policies. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016, 70, 537-540. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L.; Jun, S.; Murphy, L.; Green, R.; Gahche, J.J.; Dwyer, J.T.; Potischman, N.; McCabe, G.P.; Miller, J.W. High folic acid or folate combined with low vitamin B-12 status: potential but inconsistent association with cognitive function in a nationally representative cross-sectional sample of US older adults participating in the NHANES. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020, 112, 1547-1557. [CrossRef]

- Paul, L.; Selhub, J. Interaction between excess folate and low vitamin B12 status. Mol Aspects Med 2017, 53, 43-47. [CrossRef]

- Will, J.J.; Mueller, J.F.; Brodine, C.; Kiely, C.E.; Friedman, B.; Hawkins, V.R.; Dutra, J.; Vilter, R.W. Folic acid and vitamin B12 in pernicious anemia; studies on patients treated with these substances over a ten year period. J Lab Clin Med 1959, 53, 22-38.

- Lear, A.A.; Castle, W.B. Supplemental folic acid therapy in pernicious anemia: the effect on erythropoiesis and serum vitamin B12 concentrations in selected cases. J Lab Clin Med 1956, 47, 88-97.

- Bok, J.; Faber, J.G.; De Vries, J.A.; Kroese, W.F.; Nieweg, H.O. The effect of pteroylglutamic acid administration on the serum vitamin B12 concentration in pernicious anemia in relapse. J Lab Clin Med 1958, 51, 667-671.

- Moore, E.M.; Ames, D.; Mander, A.G.; Carne, R.P.; Brodaty, H.; Woodward, M.C.; Boundy, K.; Ellis, K.A.; Bush, A.I.; Faux, N.G., et al. Among vitamin B12 deficient older people, high folate levels are associated with worse cognitive function: combined data from three cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis 2014, 39, 661-668. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.S.; Selhub, J.; Jacques, P.F. Vitamin B-12 and folate status in relation to decline in scores on the mini-mental state examination in the framingham heart study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012, 60, 1457-1464. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.S.; Jacques, P.F.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Selhub, J. Folate and vitamin B-12 status in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive impairment in older Americans in the age of folic acid fortification. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 85, 193-200. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Bienias, J.L.; Tangney, C.C.; Hebert, L.E.; Scherr, P.A.; Schneider, J.A. Dietary folate and vitamin B12 intake and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older persons. Arch Neurol 2005, 62, 641-645. [CrossRef]

- van Gool, J.D.; Hirche, H.; Lax, H.; Schaepdrijver, L. Fallacies of clinical studies on folic acid hazards in subjects with a low vitamin B(12) status. Crit Rev Toxicol 2020, 50, 177-187. [CrossRef]

- Selhub, J.; Miller, J.W.; Troen, A.M.; Mason, J.B.; Jacques, P.F. Perspective: The High-Folate-Low-Vitamin B-12 Interaction Is a Novel Cause of Vitamin B-12 Depletion with a Specific Etiology-A Hypothesis. Adv Nutr 2022, 13, 16-33. [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.; Sobczyńska-Malefora, A. The Relationship Between Folate, Vitamin B12 and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus With Proposed Mechanisms and Foetal Implications. J Family Reprod Health 2021, 15, 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kale, A.; Dangat, K.; Sable, P.; Kulkarni, A.; Joshi, S. Maternal micronutrients (folic acid and vitamin B12) and omega 3 fatty acids: Implications for neurodevelopmental risk in the rat offspring. Brain and Development 2012, 34, 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.M.; Tai, D.C.; Aleliunas, R.E.; Aljaadi, A.M.; Glier, M.B.; Xu, E.E.; Miller, J.W.; Verchere, C.B.; Green, T.J.; Devlin, A.M. Maternal folic acid supplementation with vitamin B(12) deficiency during pregnancy and lactation affects the metabolic health of adult female offspring but is dependent on offspring diet. Faseb j 2018, 32, 5039-5050. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Dangat, K.; Kale, A.; Sable, P.; Chavan-Gautam, P.; Joshi, S. Effects of Altered Maternal Folic Acid, Vitamin B12 and Docosahexaenoic Acid on Placental Global DNA Methylation Patterns in Wistar Rats. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e17706. [CrossRef]

- Sable, P.; Dangat, K.; Kale, A.; Joshi, S. Altered brain neurotrophins at birth: consequence of imbalance in maternal folic acid and vitamin B12 metabolism. Neuroscience 2011, 190, 127-134. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.E.; Mikael, L.G.; Leung, K.Y.; Levesque, N.; Deng, L.; Wu, Q.; Malysheva, O.V.; Best, A.; Caudill, M.A.; Greene, N.D., et al. High folic acid consumption leads to pseudo-MTHFR deficiency, altered lipid metabolism, and liver injury in mice. Am J Clin Nutr 2015, 101, 646-658. [CrossRef]

- Bahous, R.H.; Jadavji, N.M.; Deng, L.; Cosin-Tomas, M.; Lu, J.; Malysheva, O.; Leung, K.Y.; Ho, M.K.; Pallas, M.; Kaliman, P., et al. High dietary folate in pregnant mice leads to pseudo-MTHFR deficiency and altered methyl metabolism, with embryonic growth delay and short-term memory impairment in offspring. Hum Mol Genet 2017, 26, 888-900. [CrossRef]

- Cornet, D.; Clement, A.; Clement, P.; Menezo, Y. High doses of folic acid induce a pseudo-methylenetetrahydrofolate syndrome. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2019, 7, 2050313x19850435. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.E.C.; Hornstra, J.M.; Kok, R.M.; Blom, H.J.; Smulders, Y.M. Folic acid supplementation does not reduce intracellular homocysteine, and may disturb intracellular one-carbon metabolism. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM) 2013, 51, 1643-1650. [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.J.; Nemkov, T.; Casas-Selves, M.; Bilousova, G.; Zaberezhnyy, V.; Higa, K.C.; Serkova, N.J.; Hansen, K.C.; D’Alessandro, A.; DeGregori, J. Folate dietary insufficiency and folic acid supplementation similarly impair metabolism and compromise hematopoiesis. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1985-1994. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, B.; Jin, D.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Zu, Y. Precise Dose of Folic Acid Supplementation Is Essential for Embryonic Heart Development in Zebrafish. Biology 2021, 11, 28. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Kuizon, S.; Ted Brown, W.; Junaid, M.A. High Gestational Folic Acid Supplementation Alters Expression of Imprinted and Candidate Autism Susceptibility Genes in a sex-Specific Manner in Mouse Offspring. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2016, 58, 277-286. [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Kuizon, S.; Chadman, K.K.; Flory, M.J.; Brown, W.T.; Junaid, M.A. Single-base resolution of mouse offspring brain methylome reveals epigenome modifications caused by gestational folic acid. Epigenetics and Chromatin 2014, 10.1186/1756-8935-7-3. [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Cosín-Tomás, M.; Leclerc, D.; Malysheva, O.V.; Caudill, M.A.; Rozen, R. Moderate Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Mice Results in Altered Sex-Specific Gene Expression in Brain of Young Mice and Embryos. Nutrients 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.W.; Ayling, J.E. The extremely slow and variable activity of dihydrofolate reductase in human liver and its implications for high folic acid intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 15424-15429. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, X.; Yao, J.; Yang, X. Paternal chronic folate supplementation induced the transgenerational inheritance of acquired developmental and metabolic changes in chickens. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2019, 286, 20191653. [CrossRef]

- Ducker, G.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Cell Metabolism Review One-Carbon Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metabolism 2017, 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.08.009. [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.G. Roles of folylpoly-gamma-glutamate synthetase in therapeutics with tetrahydrofolate antimetabolites: an overview. Semin Oncol 1999, 26, 24-32.

- Mohanty, V.; Shah, A.; Allender, E.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Monick, S.; Ichi, S.; Mania-Farnell, B.; G. McLone, D.; Tomita, T.; Mayanil, C.S. Folate Receptor Alpha Upregulates Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 and Downregulates miR-138 and miR-let-7 in Cranial Neural Crest Cells. STEM CELLS 2016, 34, 2721-2732. [CrossRef]

- Boshnjaku, V.; Shim, K.W.; Tsurubuchi, T.; Ichi, S.; Szany, E.V.; Xi, G.; Mania-Farnell, B.; McLone, D.G.; Tomita, T.; Mayanil, C.S. Nuclear localization of folate receptor alpha: a new role as a transcription factor. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 980. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, V.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tomita, T.; Mayanil, C.S. Folate receptor alpha is more than just a folate transporter. Neurogenesis (Austin) 2017, 4, e1263717. [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, B.; Bizzoni, C.; Jansen, G.; Leamon, C.P.; Peters, G.J.; Low, P.S.; Matherly, L.H.; Figini, M. Folate receptors and transporters: biological role and diagnostic/therapeutic targets in cancer and other diseases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019, 38, 125. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.F.; Greibe, E.; Skovbjerg, S.; Rohde, S.; Kristensen, A.C.; Jensen, T.R.; Stentoft, C.; Kjær, K.H.; Kronborg, C.S.; Martensen, P.M. Folic acid mediates activation of the pro-oncogene STAT3 via the Folate Receptor alpha. Cell Signal 2015, 27, 1356-1368. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Huang, G.W.; Tian, Z.H.; Ren, D.L.; Wilson, J.X. Folate stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell proliferation in fetal neural stem cells. Nutr Neurosci 2009, 12, 226-232. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.T.; Chang, C.; Lee, W.S. Folic acid inhibits COLO-205 colon cancer cell proliferation through activating the FRα/c-SRC/ERK1/2/NFκB/TP53 pathway: in vitro and in vivo studies. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 11187. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Gobinath, A.R.; Wen, Y.; Austin, J.; Galea, L.A.M. Folic acid, but not folate, regulates different stages of neurogenesis in the ventral hippocampus of adult female rats. J Neuroendocrinol 2019, 31, e12787. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.Y.; Dixon, H.M.; Yoganayagam, S.; Price, N.; Lang, D. Folic acid modulates eNOS activity via effects on posttranslational modifications and protein-protein interactions. Eur J Pharmacol 2013, 714, 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Köbel, M.; Madore, J.; Ramus, S.J.; Clarke, B.A.; Pharoah, P.D.; Deen, S.; Bowtell, D.D.; Odunsi, K.; Menon, U.; Morrison, C., et al. Evidence for a time-dependent association between FOLR1 expression and survival from ovarian carcinoma: implications for clinical testing. An Ovarian Tumour Tissue Analysis consortium study. Br J Cancer 2014, 111, 2297-2307. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Yu, B.; Mao, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D. Effect of maternal folic acid supplementation on hepatic proteome in newborn piglets. Nutrition 2013, 29, 230-234. [CrossRef]

- Pannia, E.; Hammoud, R.; Kubant, R.; Sa, J.Y.; Simonian, R.; Wasek, B.; Ashcraft, P.; Bottiglieri, T.; Pausova, Z.; Anderson, G.H. High Intakes of [6S]-5-Methyltetrahydrofolic Acid Compared with Folic Acid during Pregnancy Programs Central and Peripheral Mechanisms Favouring Increased Food Intake and Body Weight of Mature Female Offspring. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.M.; Kamynina, E.; Field, M.S.; Stover, P.J. Folate rescues vitamin B(12) depletion-induced inhibition of nuclear thymidylate biosynthesis and genome instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E4095-e4102. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B.A.; Willis, G. How folate metabolism affects colorectal cancer development and treatment; a story of heterogeneity and pleiotropy. Cancer Letters 2015, 356, 224-230. [CrossRef]

- Pufulete, M.; Emery, P.W.; Sanders, T.A.B. Folate, DNA methylation and colo-rectal cancer. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2003, 10.1079/pns2003265. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.P.; Aladelokun, O.; Kadaveru, K.; Rosenberg, D.W. Methyl donor deficiency blocks colorectal cancer development by affecting key metabolic pathways. Cancer Prevention Research 2020, 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0188. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.M.; Weir, D.G. Relevance of folate metabolism in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 2001, 138, 164-176. [CrossRef]

- Charles, M.A.; Johnson, I.T.; Belshaw, N.J. Supra-physiological folic acid concentrations induce aberrant DNA methylation in normal human cells in vitro. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 689-694. [CrossRef]

- Ortbauer, M.; Ripper, D.; Fuhrmann, T.; Lassi, M.; Auernigg-Haselmaier, S.; Stiegler, C.; Konig, J. Folate deficiency and over-supplementation causes impaired folate metabolism: Regulation and adaptation mechanisms in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016, 60, 949-956. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, B.; Jin, D.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Zu, Y. Precise Dose of Folic Acid Supplementation Is Essential for Embryonic Heart Development in Zebrafish. Biology (Basel) 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zgheib, R.; Battaglia-Hsu, S.F.; Hergalant, S.; Quéré, M.; Alberto, J.M.; Chéry, C.; Rouyer, P.; Gauchotte, G.; Guéant, J.L.; Namour, F. Folate can promote the methionine-dependent reprogramming of glioblastoma cells towards pluripotency. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 596. [CrossRef]

- Kaittanis, C.; Andreou, C.; Hieronymus, H.; Mao, N.; Foss, C.A.; Eiber, M.; Weirich, G.; Panchal, P.; Gopalan, A.; Zurita, J., et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen cleavage of vitamin B9 stimulates oncogenic signaling through metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Exp Med 2018, 215, 159-175. [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.K.; Smith, M.J.; Jadavji, N.M. Maternal oversupplementation with folic acid and its impact on neurodevelopment of offspring. Nutrition Reviews 2018, 76, 708-721. [CrossRef]

- Ondičová, M.; Irwin, R.E.; Thursby, S.J.; Hilman, L.; Caffrey, A.; Cassidy, T.; McLaughlin, M.; Lees-Murdock, D.J.; Ward, M.; Murphy, M., et al. Folic acid intervention during pregnancy alters DNA methylation, affecting neural target genes through two distinct mechanisms. Clin Epigenetics 2022, 14, 63. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.C.; Sharp, G.C.; Herbert, G.; Atkinson, C.; Taylor, C.; Bhattacharya, S.; Campbell, D.; Hall, M.; Kazmi, N.; Gaunt, T., et al. The long-term impact of folic acid in pregnancy on offspring DNA methylation: follow-up of the Aberdeen Folic Acid Supplementation Trial (AFAST). Int J Epidemiol 2018, 47, 928-937. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gueant-Rodriguez, R.M.; Quilliot, D.; Sirveaux, M.A.; Meyre, D.; Gueant, J.L.; Brunaud, L. Folate and vitamin B12 status is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in morbid obesity. Clin Nutr 2018, 37, 1700-1706. [CrossRef]

- Yajnik, C.S.; Deshpande, S.S.; Jackson, A.A.; Refsum, H.; Rao, S.; Fisher, D.J.; Bhat, D.S.; Naik, S.S.; Coyaji, K.J.; Joglekar, C.V., et al. Vitamin B12 and folate concentrations during pregnancy and insulin resistance in the offspring: the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Paniz, C.; Bertinato, J.F.; Lucena, M.R.; De Carli, E.; Amorim, P.M.D.S.; Gomes, G.W.; Palchetti, C.Z.; Figueiredo, M.S.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Fazili, Z., et al. A Daily Dose of 5 mg Folic Acid for 90 Days Is Associated with Increased Serum Unmetabolized Folic Acid and Reduced Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity in Healthy Brazilian Adults. The Journal of Nutrition 2017, 147, 1677-1685. [CrossRef]

- Sawaengsri, H.; Wang, J.; Reginaldo, C.; Steluti, J.; Wu, D.; Meydani, S.N.; Selhub, J.; Paul, L. High folic acid intake reduces natural killer cell cytotoxicity in aged mice. J Nutr Biochem 2016, 30, 102-107. [CrossRef]

- Kadaveru, K.; Protiva, P.; Greenspan, E.J.; Kim, Y.I.; Rosenberg, D.W.; K, K.; P, P.; Ej, G.; Yi, K.; Dw, R., et al. Dietary methyl donor depletion protects against intestinal tumorigenesis in Apc(Min/+) mice. Cancer Prevention Research 2012, 5, 911-920. [CrossRef]

- Protiva, P.; Mason, J.B.; Liu, Z.; Hopkins, M.E.; Nelson, C.; Marshall, J.R.; Lambrecht, R.W.; Pendyala, S.; Kopelovich, L.; Kim, M., et al. Altered folate availability modifies the molecular environment of the human colorectum: implications for colorectal carcinogenesis. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa.) 2011, 4, 530-543. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.B.; Kennelly, J.P.; Ordonez, M.; Nelson, R.; Leonard, K.; Stabler, S.; Gomez-Munoz, A.; Field, C.J.; Jacobs, R.L. Excess Folic Acid Increases Lipid Storage, Weight Gain, and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in High Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Nutrients 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Annibal, A.; Tharyan, R.G.; Schonewolff, M.F.; Tam, H.; Latza, C.; Auler, M.M.K.; Antebi, A. Regulation of the one carbon folate cycle as a shared metabolic signature of longevity. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Janssens, G.E.; McIntyre, R.L.; Molenaars, M.; Kamble, R.; Gao, A.W.; Jongejan, A.; Weeghel, M.V.; MacInnes, A.W.; Houtkooper, R.H. Glycine promotes longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans in a methionine cycle-dependent fashion. PLoS Genet 2019, 15, e1007633. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).