Submitted:

28 September 2023

Posted:

29 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

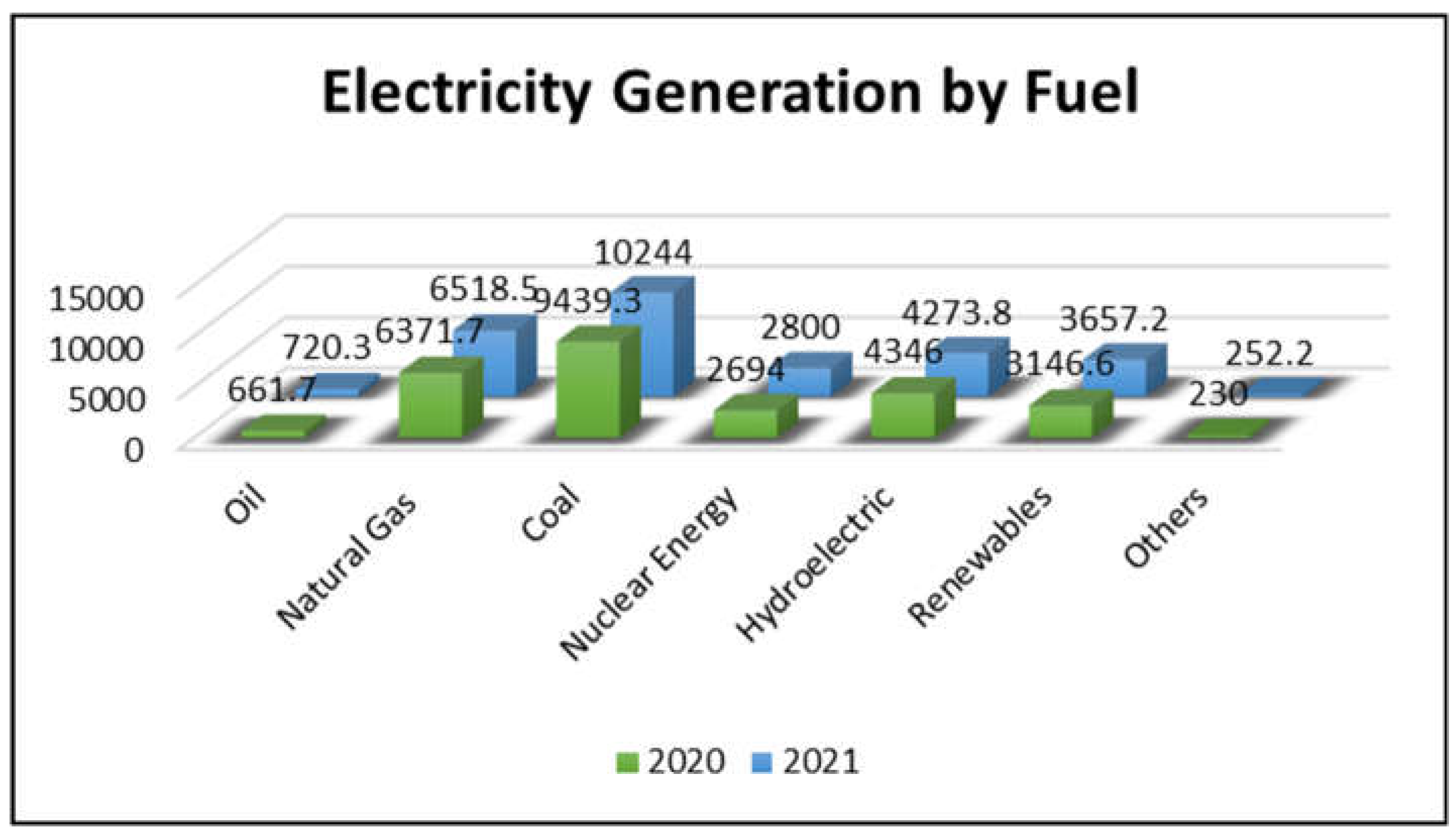

1. Introduction

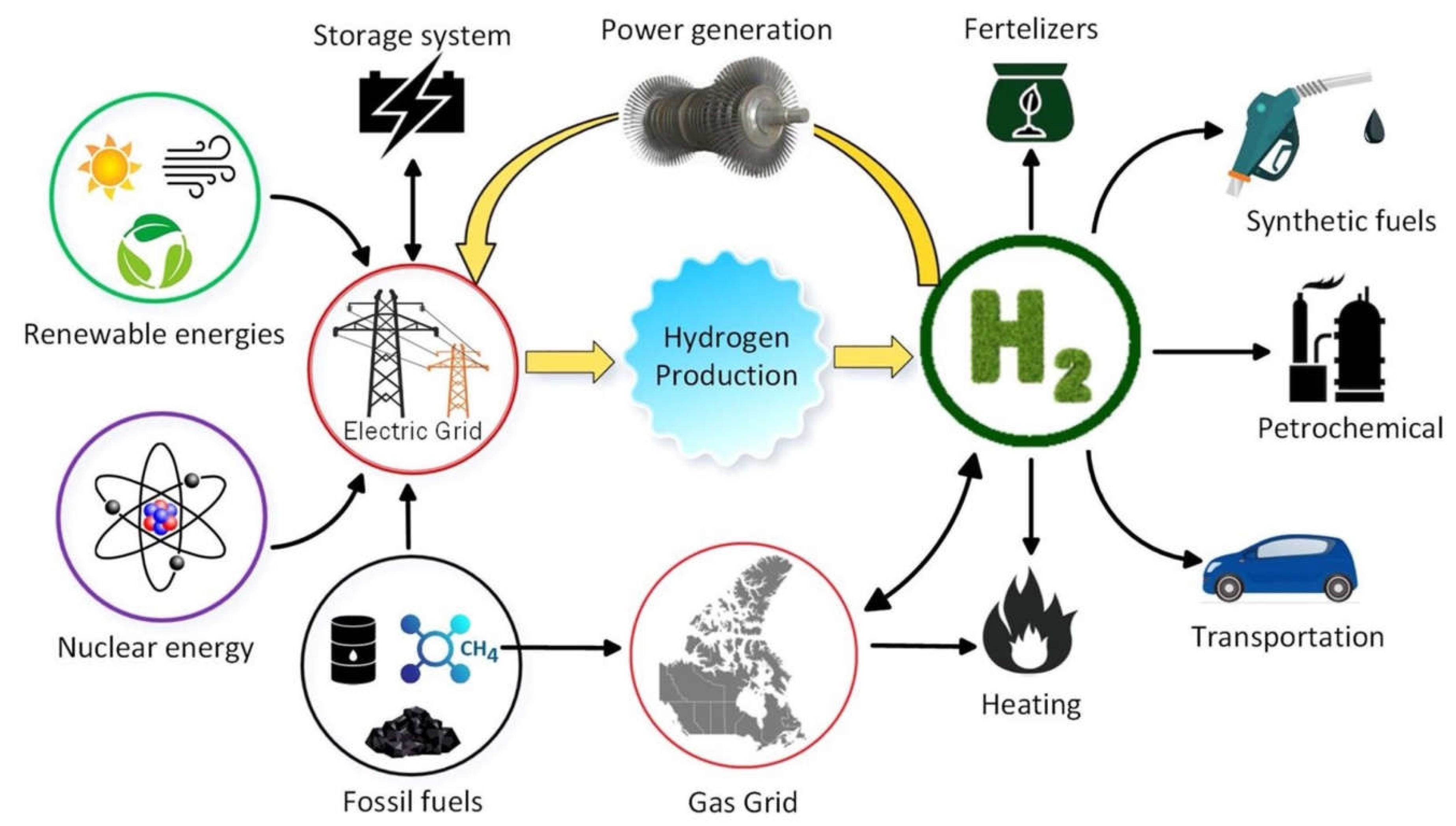

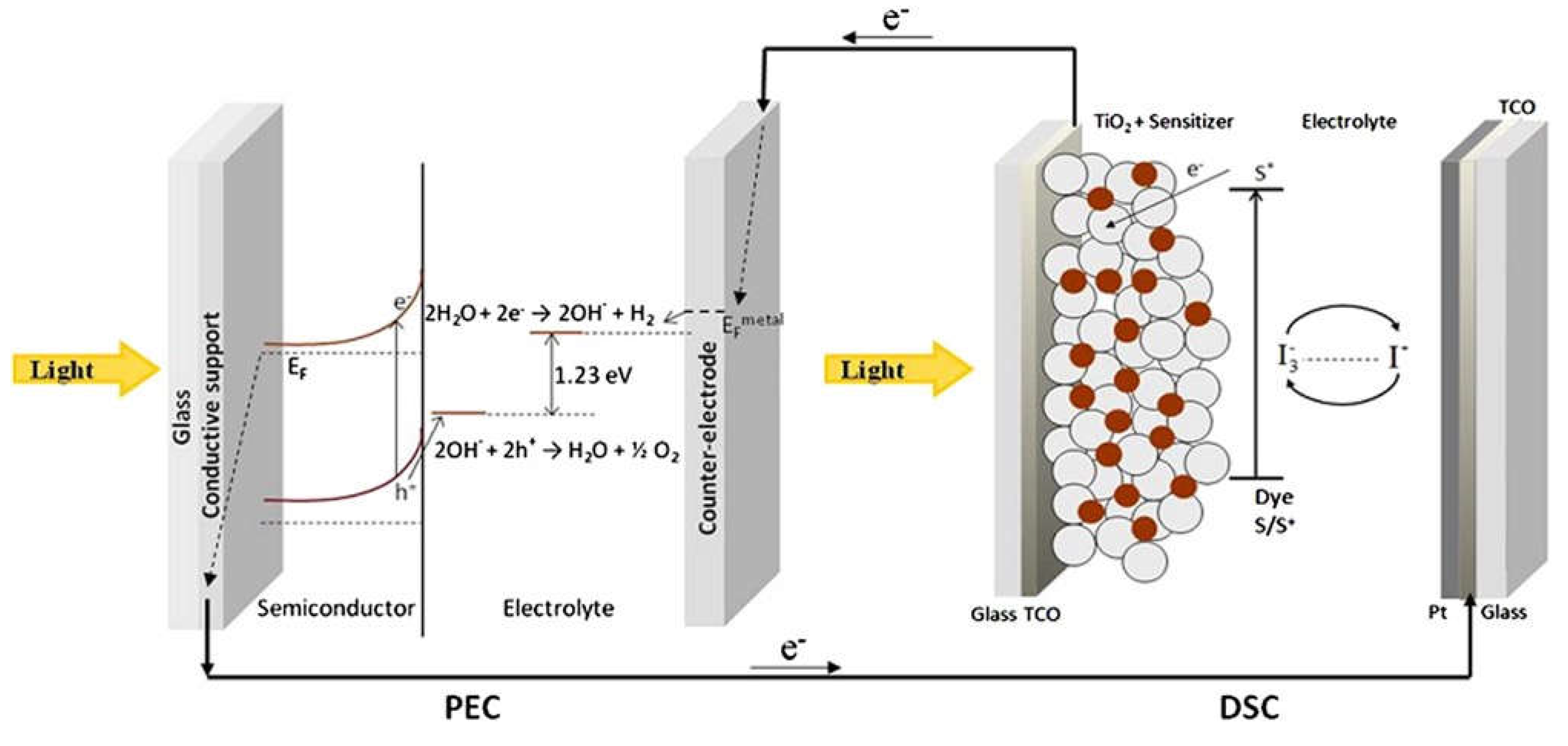

2. Hydrogen as Energy Carrier

3. Hydrogen Production Methods

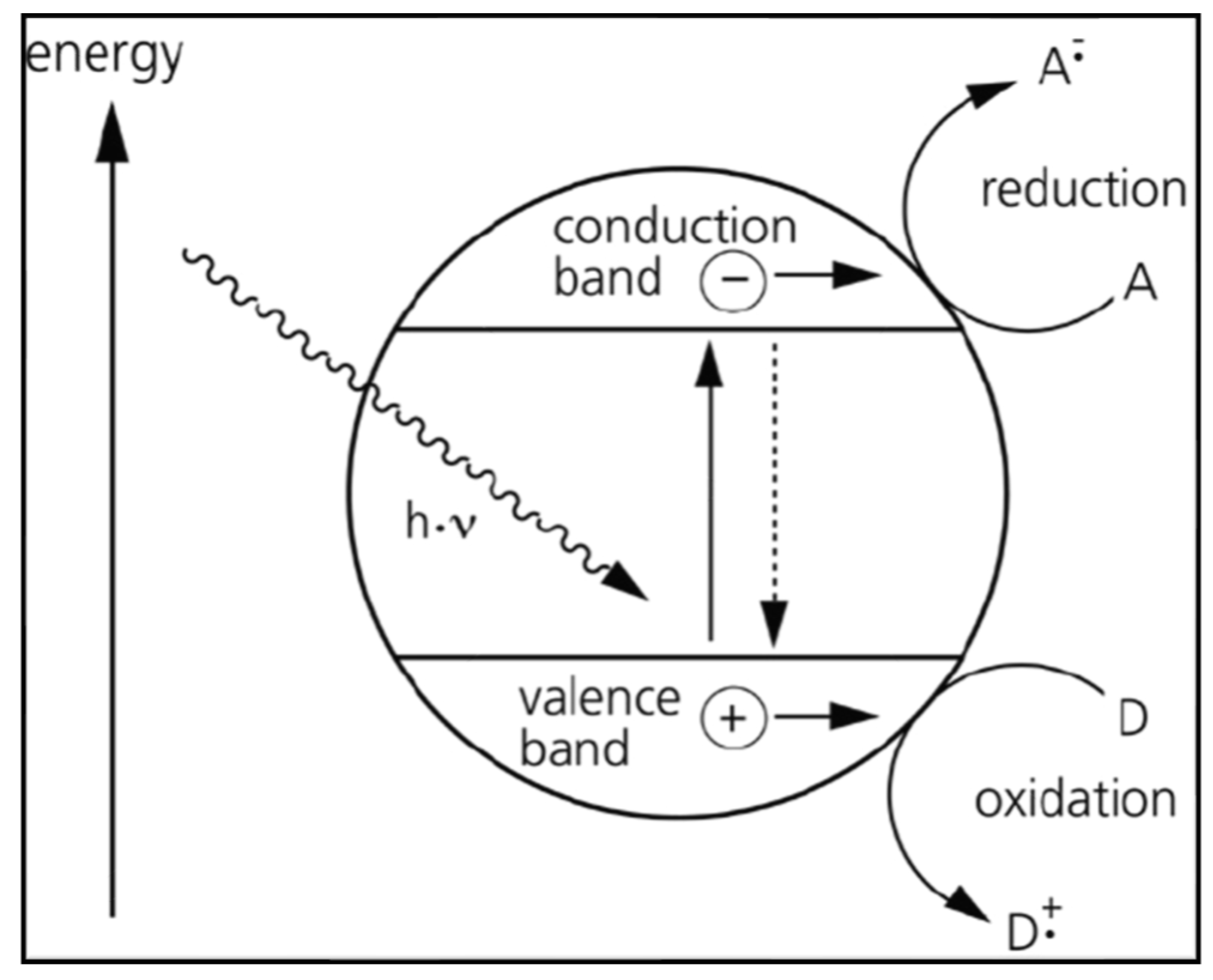

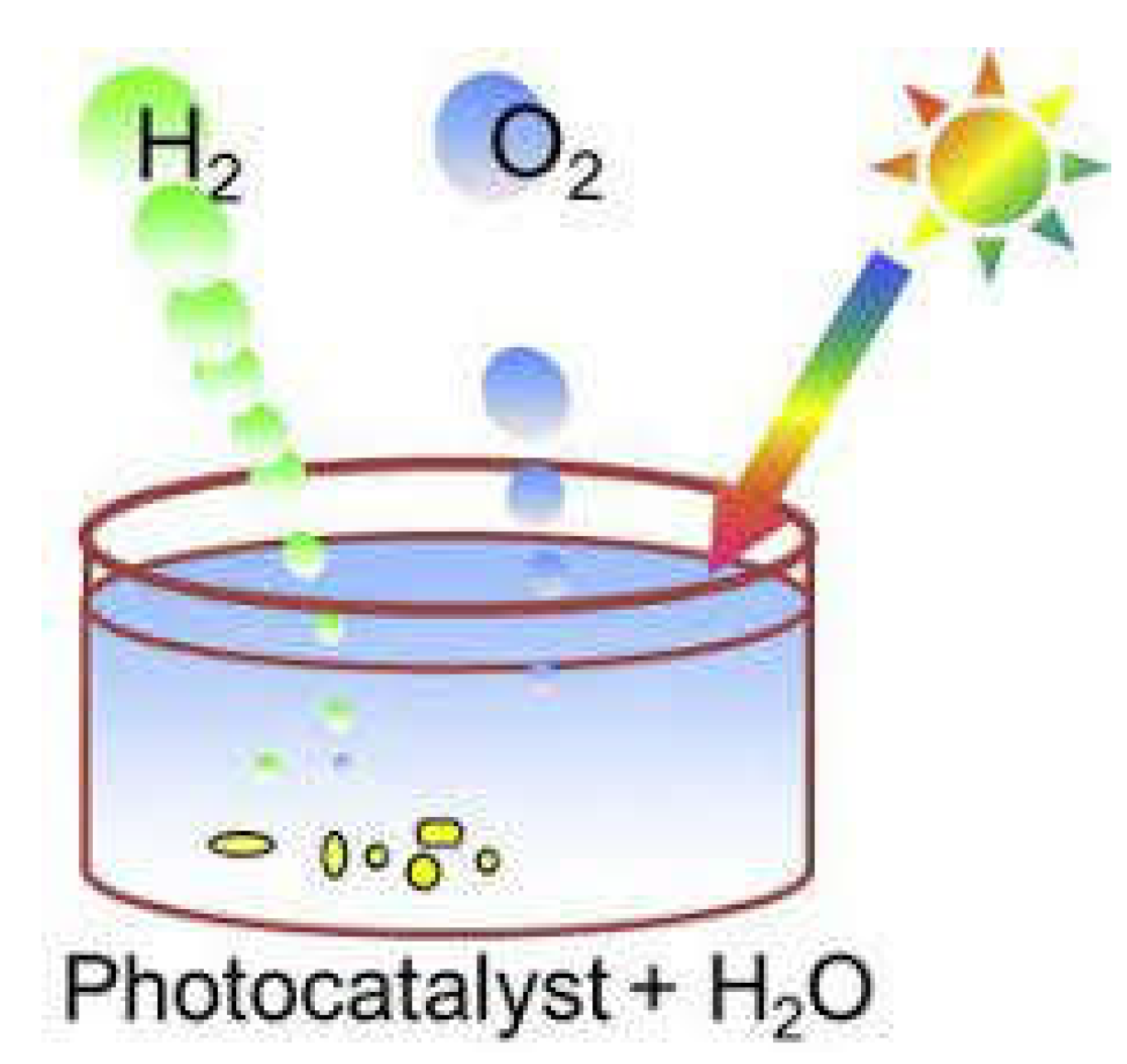

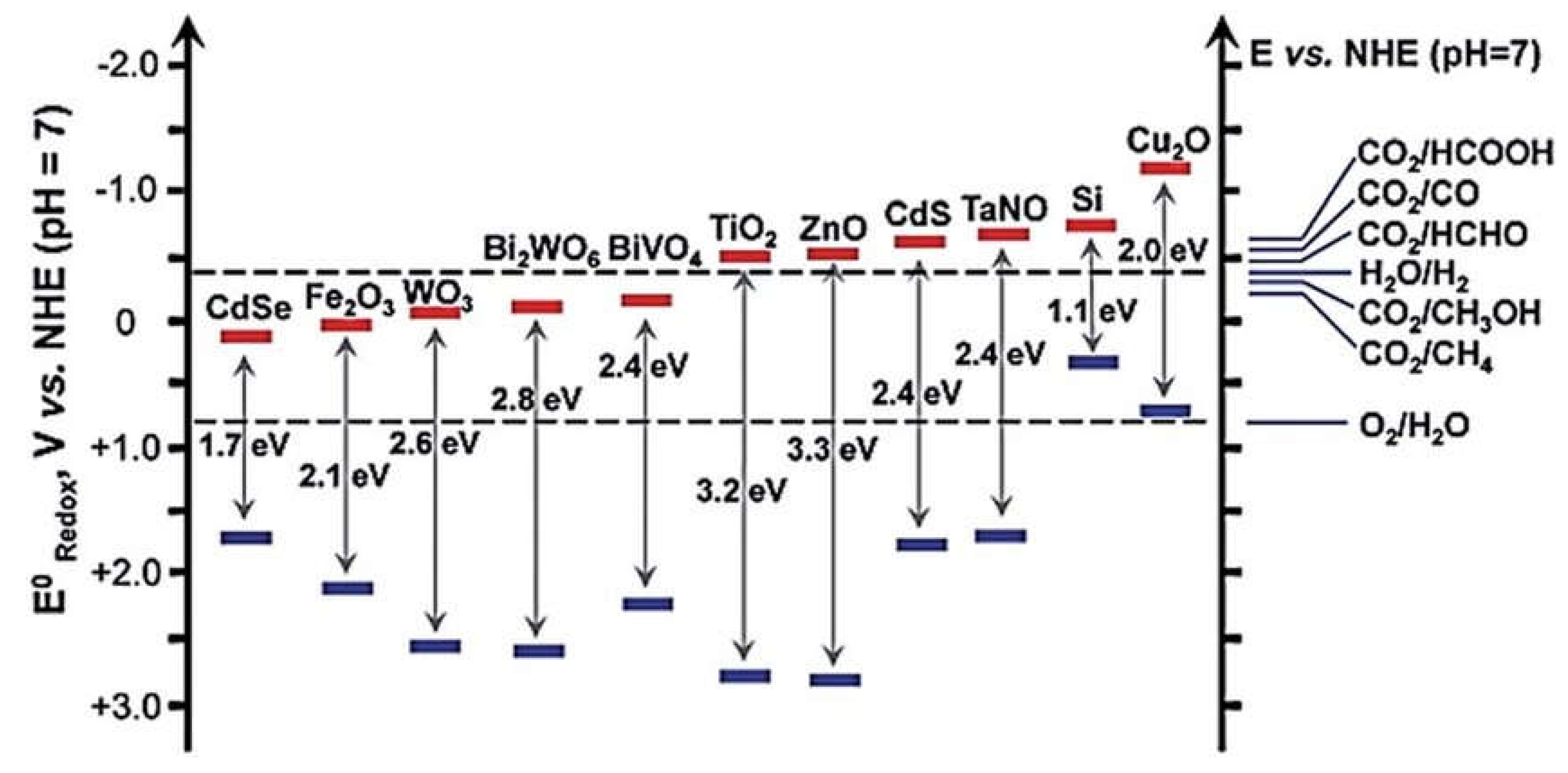

4. Photocatalytic Semiconductor Materials

5. Tandem Cells

6. Limitations Associated with Current Technologies for Hydrogen Production

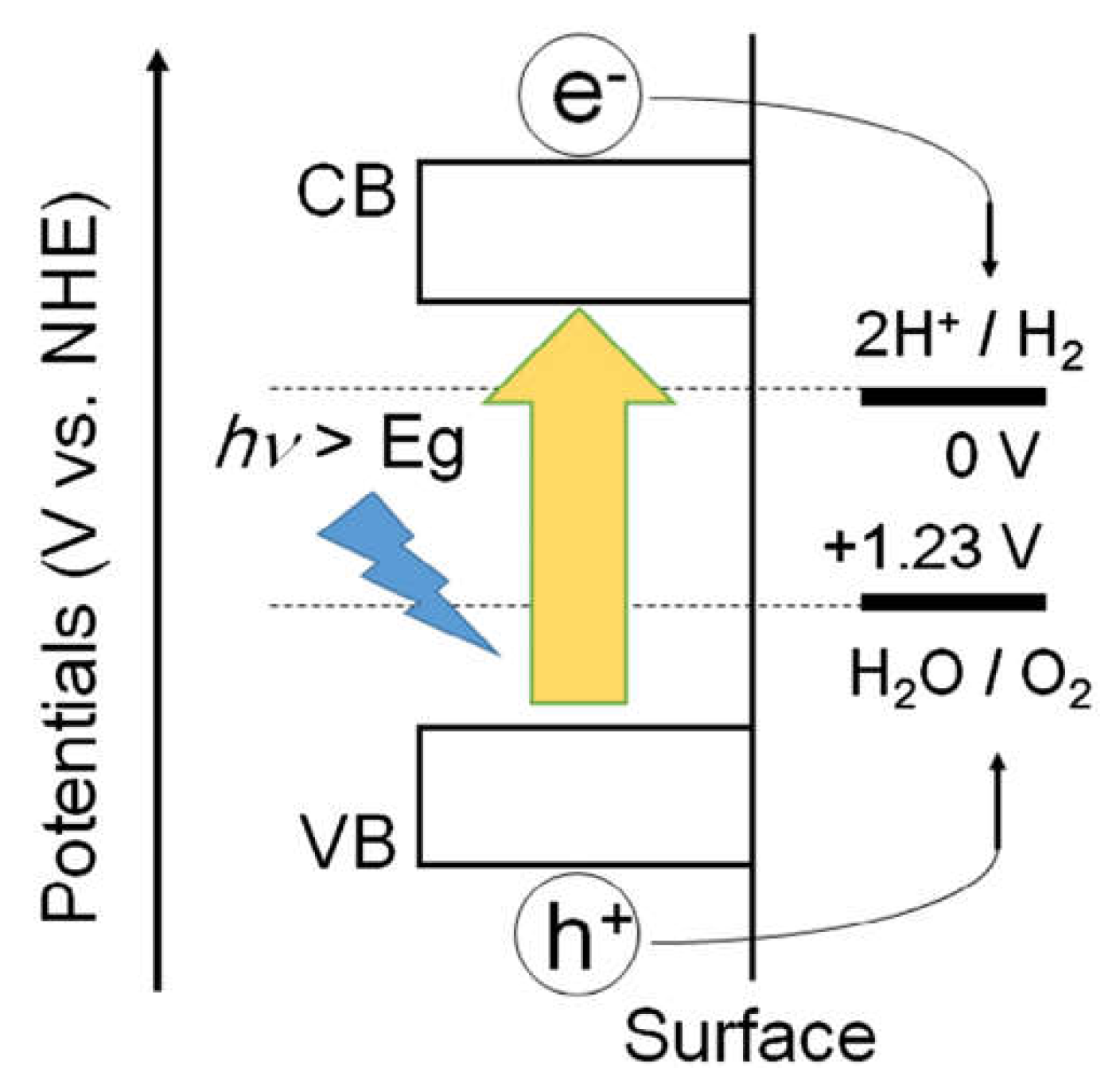

7. Theory of Water Splitting

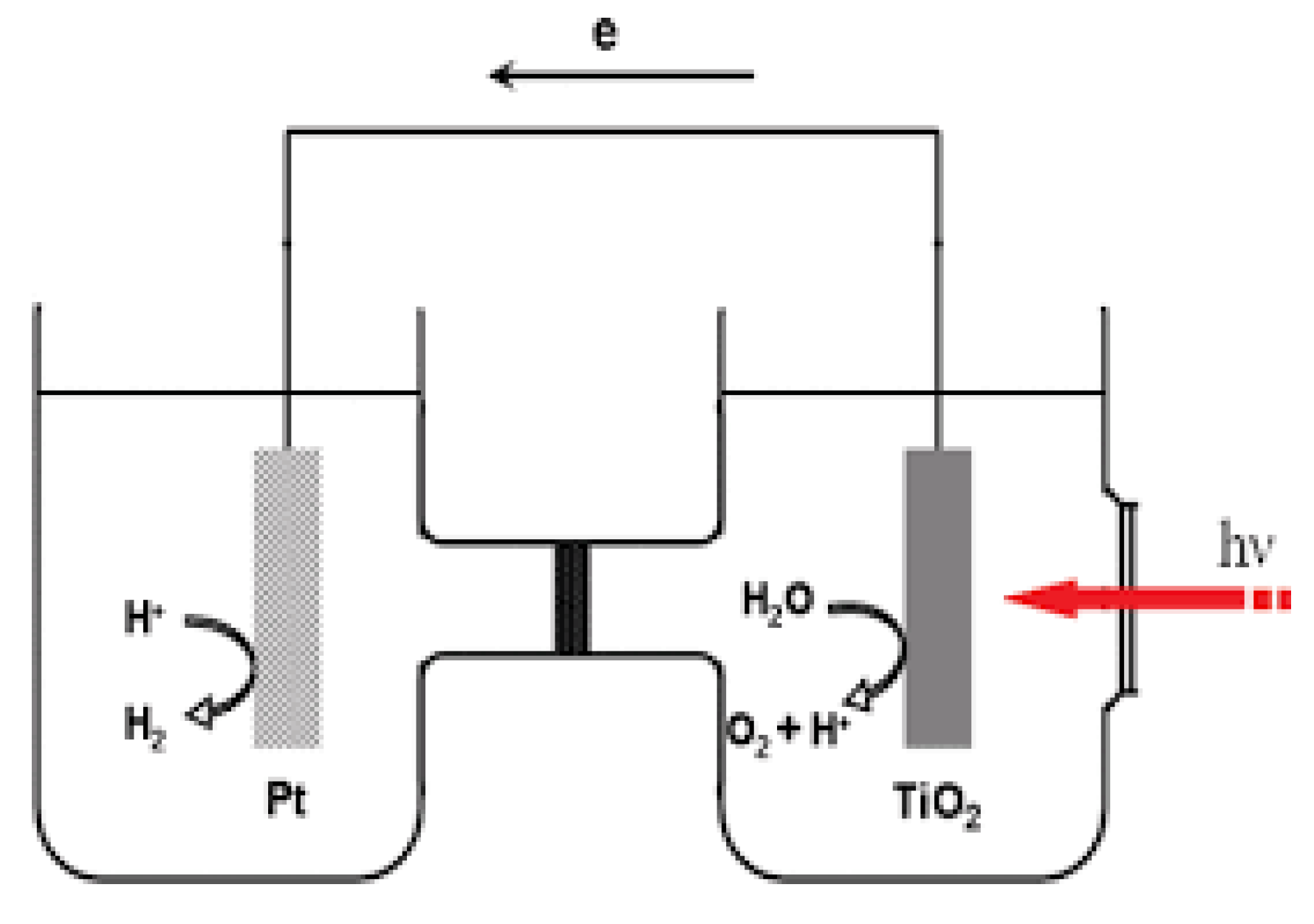

8. Principles of Photocatalytic Water Splitting in PEC Cell

9. PEC Water-splitting Process in Photoanode

10. Photocatalysis for Water Splitting

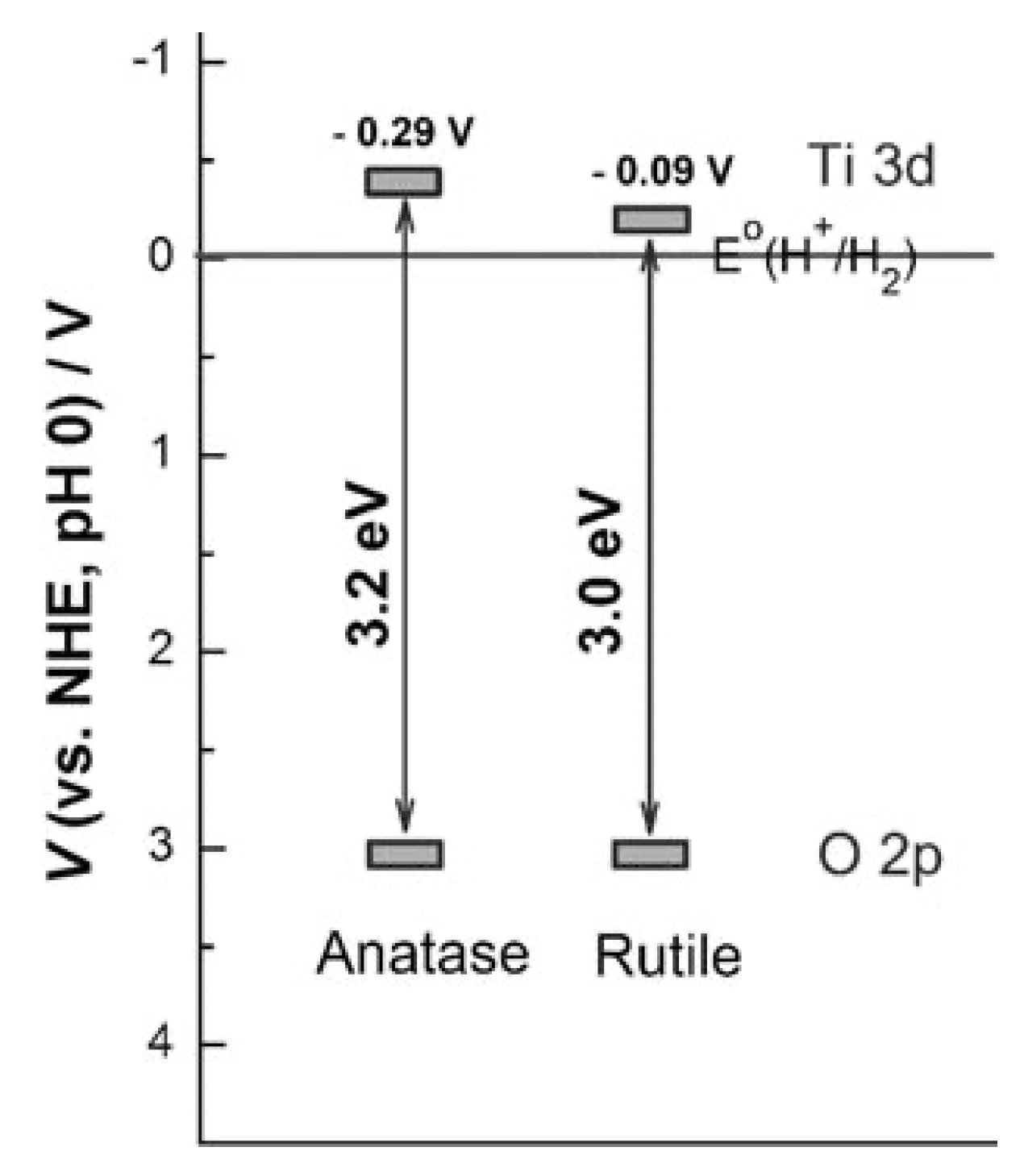

a. TiO2 Photocatalyst in PEC Cell

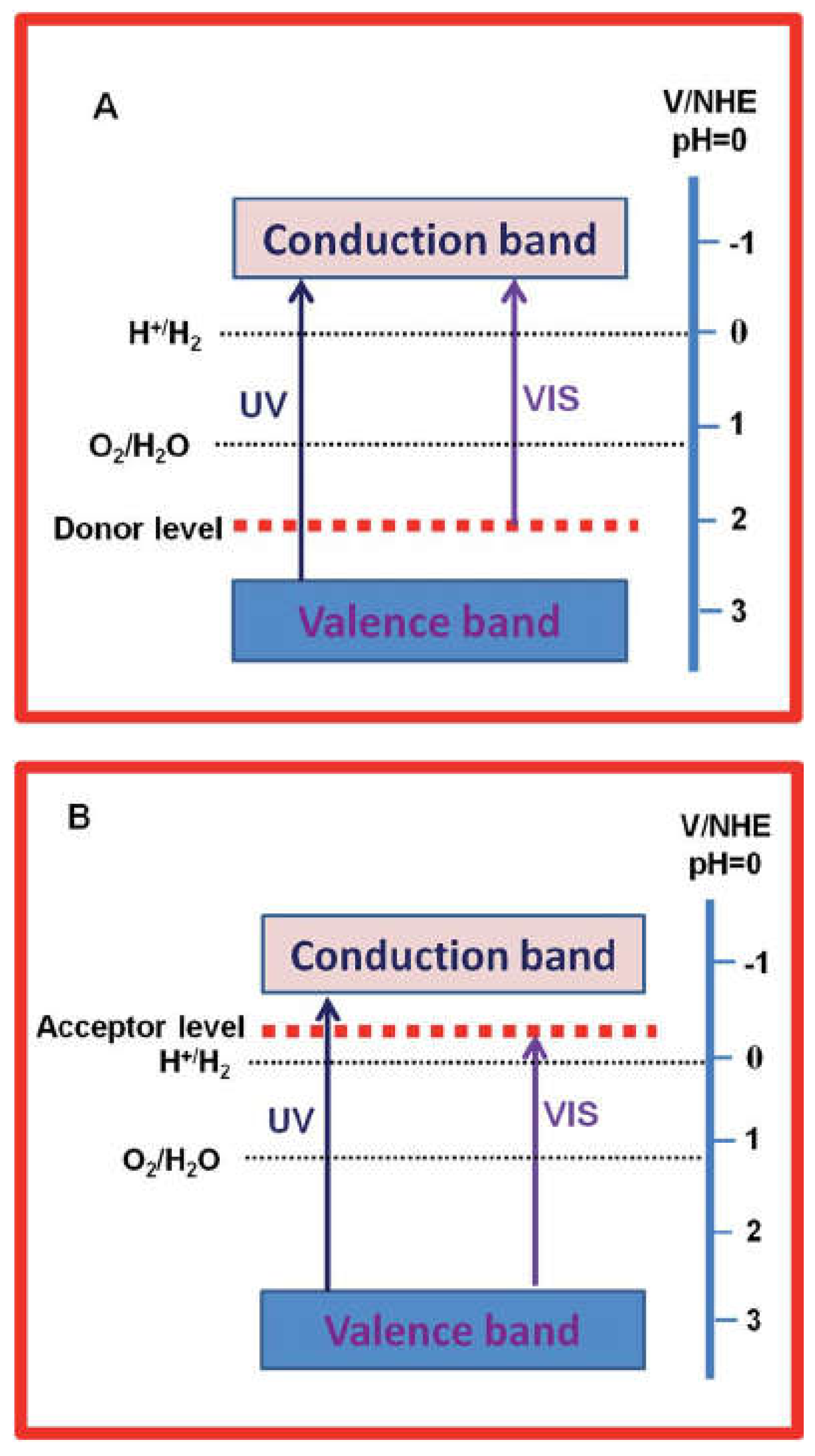

b. Modification of TiO2 Photocatalyst in PEC Cell

c. Monometallic Doped TiO2

d. Bimetallic Doped TiO2

11. Factors Influencing the Photocatalytic Water Splitting

a. Recombination of Photogenerated Charge Carriers

i. Calcination Temperature and Duration

ii. Metal Loading

iii. Metal Mass Composition

b.Photoanode Instability Mechanism

i. Sintering Temperature of Photoanode

ii. Photoanode Thickness

iii. Photoanode Geometric Area

c. Photocurrent Density Affects the Hydrogen Production

i. Distance Between Two Electrodes

ii. Depth of Electrode Immersion

iii. Illumination Intensity

iv. Sacrificial Agent

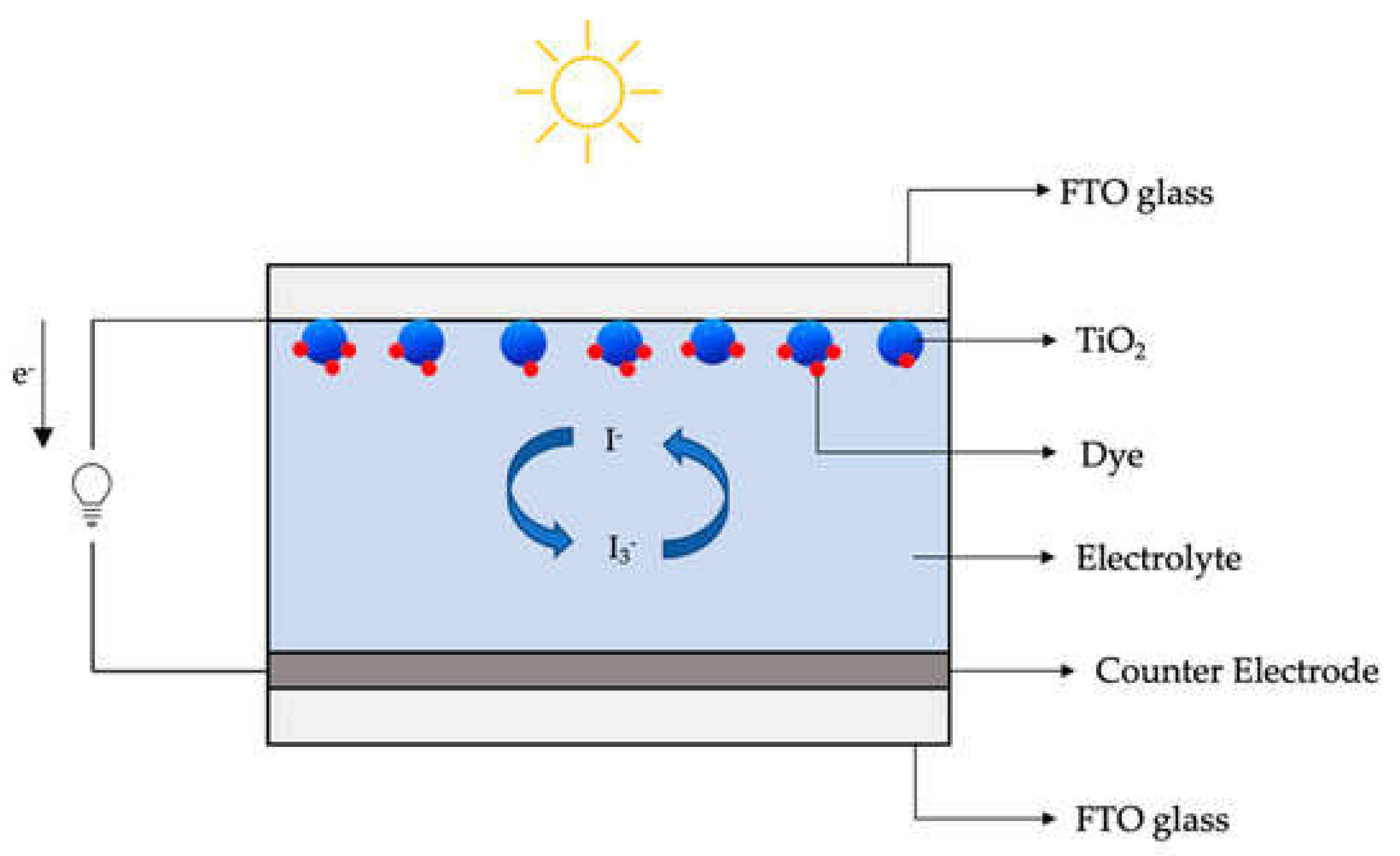

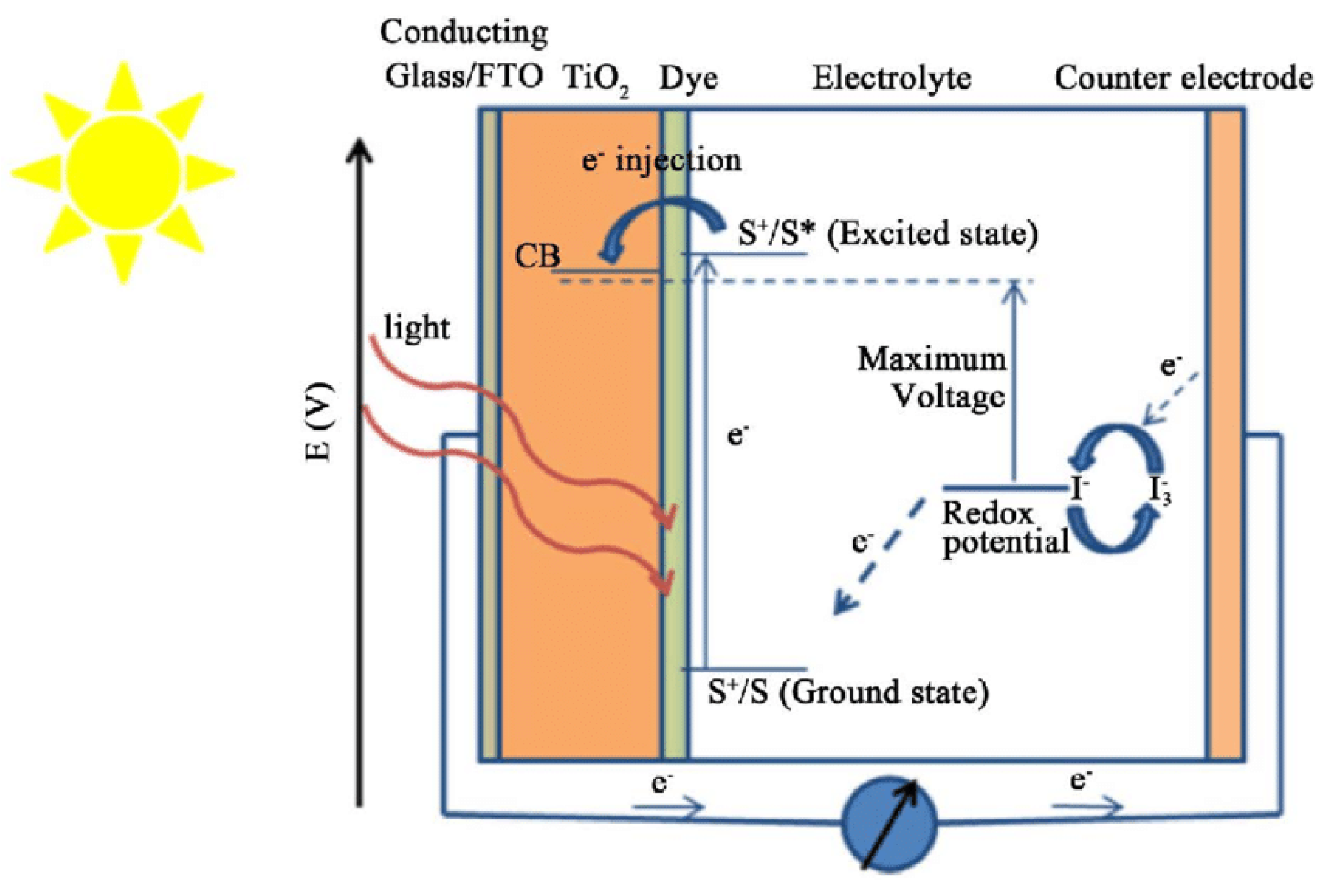

12. Dye Solar Cell (DSC)

13. Conclusion

References

- Energy. Agency and International Energy Agency., World energy outlook 2013. International Energy Agency, 2013.

- bp, “Statistical Review of World Energy 2022.

- Dincer, I.; Acar, C. Review and evaluation of hydrogen production methods for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11094–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Kellens, K.; Tang, R.; Chen, C.; Chen, G. Sustainability of additive manufacturing: An overview on its energy demand and environmental impact. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 21, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.M.Z.B.W.; Zainudin, W.N.R.A.B.; Ishak, W.W.B.M.; Sulong, F.B.; Haq, H.M.Z.U. Public Participation of Renewable Energy (PPRED) Model in Malaysia: An Instrument Development. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2020, 10, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.B. Energy poverty in energy rich Ghana: A SWOT analytical approach for the development of Ghana’s renewable energy. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2020, 40, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, B.A.; Adebayo, T.S.; Bekun, F.V.; Agyekum, E.B.; Kumar, N.M.; Alhelou, H.H.; Al-Hinai, A. Beyond environmental Kuznets curve and policy implications to promote sustainable development in Mediterranean. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 6119–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, C.; Çil, M.A. A study on hydrogen, the clean energy of the future: Hydrogen storage methods. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, S.J.; Motahhir, S.; Agyekum, E.B. A new model for a photovoltaic panel using Proteus software tool under arbitrary environmental conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 333, 130074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sudik, A.; Wolverton, C.; Siegel, D.J. High capacity hydrogenstorage materials: attributes for automotive applications and techniques for materials discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 39, 656–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Veras, T.; Mozer, T.S.; da Costa Rubim Messeder dos Santos, D.; da Silva César, A. Hydrogen: Trends, production and characterization of the main process worldwide. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 2018–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, E.S.; Deane, J.P.; Gallachóir, B.P.Ó. The role of hydrogen in low carbon energy futures—A review of existing perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3027–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, S.; Manzoor, T.; Pandith, A.H. Hydrogen storage: Materials, methods and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakenne, A.; Nuttall, W.; Kazantzis, N. Sankey-Diagram-based insights into the hydrogen economy of today. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 7744–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, F.; Dincer, I. A review and comparative evaluation of thermochemical water splitting cycles for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Lambert, H.; Pahon, E.; Roche, R.; Jemei, S.; Hissel, D. Hydrogen energy systems: A critical review of technologies, applications, trends and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.; Anda, M.; Shafiullah, G.M. Hydrogen Production for Energy: An Overview. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 3847–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, Y.S. Hydrogen safety: The road toward green technology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 10716–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Valverde, L.; Pino, F.J.; Patel, M.K. A review on the role, cost and value of hydrogen energy systems for deep decarbonisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, A.; Paranos, M.; Marciuš, D. Hydrogen in energy transition: A review. 14th Conference on Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems (SDEWES). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 10016–10035.

- Maggio, G.; Nicita, A.; Squadrito, G. How the hydrogen production from RES could change energy and fuel markets: A review of recent literature. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 11371–11384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, J.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Ajenifuja, E.; Popoola, O.M. Hydrogen energy, economy and storage: Review and recommendation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 15072–15086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Fujii, M.; Geng, Y.; Dong, L.; Fujita, T. Trends and future challenges in hydrogen production and storage research. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 31092–31104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Wang, J. Review and comparison of various hydrogen production methods based on costs and life cycle impact assessment indicators. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 38612–38635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Emam, R.S.; Özcan, H. Comprehensive review on the techno-economics of sustainable large-scale clean hydrogen production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, E.C.; Al-Breiki, M.; Bicer, Y.; Al-Ansari, T. Sustainable hydrogen roadmap: A holistic review and decision-making methodology for production, utilisation and exportation using Qatar as a case study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 35525–35549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Reed, J.; Shaffer, B.; Samuelsen, S. Forecasting renewable hydrogen production technology shares under cost uncertainty. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 27293–27306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Luo, S.; Huang, H.; Deng, B.; Ye, J. Solar-Driven Hydrogen Production: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima Akira, Sugiyama Eiichi, and Honda Kenichi, “Photosensitized Electrolytic Oxidation of Iodide Ions on Cadmium Sulfide Single Crystal Electrode”.

- Oliveira, A.M.; Beswick, R.R.; Yan, Y. A green hydrogen economy for a renewable energy society. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.; Weeda, M. The hydrogen economy—Vision or reality? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 7903–7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. Green methods for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 37, 1954–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I. Green methods for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 37, 1954–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Yu, H. Water electrolysis based on renewable energy for hydrogen production. Chin. J. Catal. 2018, 39, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirollahivash, M.; Rashidi, F.; Moshrefi, M.M. Hydrogen Production from Methane Decomposition Using a Mobile and Elongating Arc Plasma Reactor. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2019, 39, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D. Review of renewable energy-based hydrogen production processes for sustainable energy innovation. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2019, 2, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, T.Y.; Raj, A.; Chanaphet, J.; Mohammed, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Al Shoaibi, A. A detailed reaction mechanism for hydrogen production via hydrogen sulphide (H2S) thermolysis and oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 6662–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, J.; Jing, T.; Chang, J.-S.; Ho, S.-H. Recent advances in hydrogen production by thermo-catalytic conversion of biomass. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 14266–14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, F.; Dincer, I. A review and comparative evaluation of thermochemical water splitting cycles for hydrogen production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, P.; Narayanan, K.S. Hydrogen production from steam gasification of biomass: Influence of process parameters on hydrogen yield – A review. Renew. Energy 2014, 66, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D. First law energy analysis of thermochemical waste-heat recuperation by steam methane reforming. Energy 2018, 143, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, R.J.; Al-Ali, K.; Green, W.H. Thermochemical production of hydrogen from hydrogen sulfide with iodine thermochemical cycles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 12939–12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Kothari, R.; Tyagi, V.; Anand, S. Integrated approach for textile industry wastewater for efficient hydrogen production and treatment through solar PV electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 25768–25782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Leung, M.K.; Leung, D.Y.; Sumathy, K. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, M.; Lee, B.-K. Recent advances in BiVO4 semiconductor materials for hydrogen production using photoelectrochemical water splitting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 111, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain Rather, A. Kumar Srivastav, and A. Abdul, “A Study on Biohydrogen Production based on Biophotolysis from Cyanobacteria,” 2021. [Online]. Available: http://annalsofrscb.

- Łukajtis, R.; Hołowacz, I.; Kucharska, K.; Glinka, M.; Rybarczyk, P.; Przyjazny, A.; Kamiński, M. Hydrogen production from biomass using dark fermentation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.P.; Evans, B.R.; Mielenz, J.R.; Hopkins, R.C.; Adams, M.W. High-Yield Hydrogen Production from Starch and Water by a Synthetic Enzymatic Pathway. PLOS ONE 2007, 2, e456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.S.; Marigorta, A.B.; Quintana, J.P. Review on hydrogen production technologies from solar energy. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 2011, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpooya, M.; Valizadeh, F.; Askarimoghadam, R.; Sadeghi, S.; Pourfayaz, F.; Mousavi, S.A. Fabrication of nano-platinum alloy electrocatalysts and their performance in a micro-direct methanol fuel cell. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2020, 135, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, J.I.; Mann, M.K.; Margolis, R.M.; Milbrandt, A. An analysis of hydrogen production from renewable electricity sources. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.-C.; Illathukandy, B.; Wu, W.; Chang, J.-S. Energy, exergy, and environmental analyses of renewable hydrogen production through plasma gasification of microalgal biomass. Energy 2021, 223, 120025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D. Optimisation of a hydrogen production – storage – re-powering system participating in electricity and transportation markets. A case study for Denmark. Appl. Energy 2020, 265, 114800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilanci, A.; Dincer, I.; Ozturk, H.K. A review on solar-hydrogen/fuel cell hybrid energy systems for stationary applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H.; Dincer, I. A comparative evaluation of OTEC, solar and wind energy based systems for clean hydrogen production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 246, 118736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, F.; Dincer, I. A critical evaluation of potential routes of solar hydrogen production for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasiano, D.; Marotta, R.; Malato, S.; Fernandez-Ibañez, P.; Di Somma, I. Solar photocatalysis: Materials, reactors, some commercial, and pre-industrialized applications. A comprehensive approach. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2015, 170-171, 90–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, N.; Padilla, R.; Rose, A.; Habibullah, H. Increasing the efficiency of hydrogen production from solar powered water electrolysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 135, 110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, A. Solar thermochemical production of hydrogen–A review. Sol. Energy 2005, 78, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoh, S.K.; Njomo, D. An overview of hydrogen gas production from solar energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6782–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wu, S.-Y.; Li, Y.-R. Advances in solar hydrogen production via two-step water-splitting thermochemical cycles based on metal redox reactions. Renew. Energy 2012, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, R.; Sahu, S.; James, O.O.; Maity, S. A review on development of industrial processes and emerging techniques for production of hydrogen from renewable and sustainable sources. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrafiotis, C.; Roeb, M.; Sattler, C. A review on solar thermal syngas production via redox pair-based water/carbon dioxide splitting thermochemical cycles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 254–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafán-Vidales, H.; Arancibia-Bulnes, C.; Riveros-Rosas, D.; Romero-Paredes, H.; Estrada, C. An overview of the solar thermochemical processes for hydrogen and syngas production: Reactors, and facilities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, S.; Mao, S.S. Black TiO 2 for solar hydrogen conversion. J. Materiomics 2017, 3, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Show, K.-Y.; Yan, Y.; Zong, C.; Guo, N.; Chang, J.-S.; Lee, D.-J. State of the art and challenges of biohydrogen from microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Shi, R.; Waterhouse, G.I.; Zhang, T. Recent advances in niobium-based semiconductors for solar hydrogen production. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 419, 213399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H. High visible transmittance of VO2 film prepared by DC magnetron sputtering with situ annealing. J. Opt. 2021, 50, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Shafiq, I.; Hussain, M.; Lam, S.S.; Rhee, G.H.; Park, Y.-K. A review on integrated thermochemical hydrogen production from water. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 47, 4346–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, C. Scalable solar water splitting using particulate photocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 33, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Zeb, Z.; Ullah, H.; Suliman, M.H.; Humayun, M.; Ullah, L.; Shah, S.N.A.; Ahmed, U.; Saeed, M. A review of metal-organic frameworks/graphitic carbon nitride composites for solar-driven green H2 production, CO2 reduction, and water purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidin, N.; Azni, S.R.; Abu Bakar, M.A.; Johari, A.R.; Munap, D.H.F.A.; Salebi, M.F.; Razak, S.N.A.; Sahidan, N.S.; Sulaiman, S.N.A. The effect of sunlight in hydrogen production from water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Valverde, L.; Pino, F.J.; Patel, M.K. A review on the role, cost and value of hydrogen energy systems for deep decarbonisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, S.M.; Müller, M.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. The investment costs of electrolysis – A comparison of cost studies from the past 30 years. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, P.; Poullikkas, A. A comparative overview of hydrogen production processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, J.; Sorrell, C.; Sheppard, L.; Bak, T. Solar-hydrogen: Environmentally safe fuel for the future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-H.; Huang, C.-W.; Wu, J.C.S. Hydrogen Production from Semiconductor-based Photocatalysis via Water Splitting. Catalysts 2012, 2, 490–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenzi, N.; Liao, W.-S.; Cremer, P.S.; Sanchez-Torres, V.; Wood, T.K.; Ehlig-Economides, C.; Cheng, Z. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen production from water/methanol decomposition using Ag/TiO2 nanocomposite thin films. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11768–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, K.; Majlan, E.H.; Daud, W.R.W.; Kassim, M.B. Bimetallic complexes in artificial photosynthesis for hydrogen production: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 3066–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Bak, J. T. Bak, J. Nowotny, M. Rekas, and C. C. Sorrell, “Photo-electrochemical hydrogen generation from water using solar energy. Materials-related aspects,” 2002. [Online]. Available: www.elsevier.

- Kudo, A.; Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 38, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Krol, R.; Liang, Y.; Schoonman, J. Solar hydrogen production with nanostructured metal oxides. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, J.; Sorrell, C.; Sheppard, L.; Bak, T. Solar-hydrogen: Environmentally safe fuel for the future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.; Cruz, R.; Ribeiro, H.A.; Mendes, A. Impedance characterization of dye-sensitized solar cells in a tandem arrangement for hydrogen production by water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 8876–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusastre and Vincent, “Materials for Sustainable Energy,” 2010. [Online]. Available: www.worldscientific.

- Muradov, N.; Veziroǧlu, T. From hydrocarbon to hydrogen–carbon to hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubitz, W.; Tumas, W. Hydrogen: An Overview. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3900–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Song, W.; Li, G.; Yi, B.; Shao, Z. A novel photoelectrochemical cell with self-organized TiO2 nanotubes as photoanodes for hydrogen generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 14374–14380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 Photocatalysis: Mechanisms and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévot, M.S.; Sivula, K. Photoelectrochemical Tandem Cells for Solar Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 17879–17893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Deutsch, T.G.; Kleiman-Shwarsctein, A.; Forman, A.J.; Gaillard, N.; Garland, R.; Takanabe, K.; Heske, C.; Sunkara, M.; et al. Accelerating materials development for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production: Standards for methods, definitions, and reporting protocols. J. Mater. Res. 2010, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkez-Kuyumcu. ; Kibar, E.; Dayıoğlu, K.; Gedik, F.; Akın, A.N.; Özkara-Aydınoğlu,. A comparative study for removal of different dyes over M/TiO 2 (M = Cu, Ni, Co, Fe, Mn and Cr) photocatalysts under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2015, 311, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandam, G.; Lalitha, K.; Kumari, V.D.; Shankar, M.V.; Subrahmanyam, M. Cobalt doped TiO2: A stable and efficient photocatalyst for continuous hydrogen production from glycerol: Water mixtures under solar light irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 9655–9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.C.; Fu, X.; Wang, C.; Ni, M.; Leung, M.K.H.; Wang, X.; Fu, X. Hydrogen Production over Titania-Based Photocatalysts. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. P25-Graphene Composite as a High Performance Photocatalyst. ACS Nano 2009, 4, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Lin, X.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, H.; Lin, J. Photocatalytic degradation kinetics and mechanism of phenobarbital in TiO2 aqueous solution. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1514–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.-D.; Yan, S.; Huang, Q.-D.; Fan, M.-T.; Yuan, Y.-Z.; Tan, T.T.-Y.; Liao, D.-W. TiO2 promoted by two different non-noble metal cocatalysts for enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 309, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreethawong, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshikawa, S. Photocatalytic evolution of hydrogen over mesoporous TiO2 supported NiO photocatalyst prepared by single-step sol–gel process with surfactant template. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriman, A.; Pickering, I.J.; Thomas, J.M.; Christensen, P.A. Metal oxides as heterogeneous catalysts for oxygen evolution under photochemical conditions. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1: Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 1988, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, P.; Li, W.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Tong, X.; Cai, Q.; Grimes, C.A. A novel method for the preparation of a photocorrosion stable core/shell CdTe/CdS quantum dot TiO2 nanotube array photoelectrode demonstrating an AM 1.5G photoconversion efficiency of 6.12%. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 7806–7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, L. Recent research progress on operational stability of metal oxide/sulfide photoanodes in photoelectrochemical cells. Nano Res. Energy 2022, 1, e9120020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Nakato, H. Y. Nakato, H. Akanuma, J.-I. Shimizu, and Y. Magari, “Photo-oxidation reaction of water on an n-TiO 2 electrode. Improvement in efficiency through formation of surface micropores by photo-etching in H2SO 4 1,” 1995.

- Koyale, P.A.; Delekar, S.D. A review on practical aspects of CeO2 and its composites for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Shinde, P.S.; Go, G.H.; Ramasamy, E. Ag grid induced photocurrent enhancement in WO3 photoanodes and their scale-up performance toward photoelectrochemical H2 generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 5262–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Shukla, P.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, O. Investigation and optimization of nanostructured TiO2 photoelectrode in regard to hydrogen production through photoelectrochemical process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, R.; Mohamed, N.M.; Kait, C.F.; Sufian, S.; Kakooei, S.; Khatani, M.; Gholami, Z. Optimization hydrogen production over visible light-driven titania-supported bimetallic photocatalyst from water photosplitting in tandem photoelectrochemical cell. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minggu, L.J.; Daud, W.R.W.; Kassim, M.B. An overview of photocells and photoreactors for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 5233–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenzi, N.; Liao, W.-S.; Cremer, P.S.; Sanchez-Torres, V.; Wood, T.K.; Ehlig-Economides, C.; Cheng, Z. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen production from water/methanol decomposition using Ag/TiO2 nanocomposite thin films. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11768–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, A.; Miseki, Y. Heterogeneous photocatalyst materials for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 38, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.; Andrade, L.; Ribeiro, H.A.; Mendes, A. Characterization of photoelectrochemical cells for water splitting by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11601–11608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minggu, L.J.; Daud, W.R.W.; Kassim, M.B. An overview of photocells and photoreactors for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 5233–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. Photoelectrocatalytic Water Splitting: Significance of Cocatalysts, Electrolyte, and Interfaces. ACS Catal. 2016, 7, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, P.; Wei, N.; Wang, D. Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water-Splitting Property on TiO2 Nanotubes by Surface Chemical Modification and Wettability Control. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20110–20118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Rao, D.; Tian, W.; Cao, F.; Yan, X.; Li, L. Simultaneous Manipulation of O-Doping and Metal Vacancy in Atomically Thin Zn 10 In 16 S 34 Nanosheet Arrays toward Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16882–16887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K. Photocatalytic water splitting using semiconductor particles: History and recent developments. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2011, 12, 237–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, A. Photocatalysis and solar hydrogen production. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 1917–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zäch, M. Nanostructured materials for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 14, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, S.J.A.; Shevlin, S.A.; Martin, D.J.; Guo, Z.-X.; Tang, J. Visible-light driven heterojunction photocatalysts for water splitting – a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Lu, X.; Tong, Y. Towards highly efficient photoanodes: boosting sunlight-driven semiconductor nanomaterials for water oxidation. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 7142–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dette, C.; Pérez-Osorio, M.A.; Kley, C.S.; Punke, P.; Patrick, C.E.; Jacobson, P.; Giustino, F.; Jung, S.J.; Kern, K. TiO2 Anatase with a Bandgap in the Visible Region. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 6533–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Linsebigler, G. L. Linsebigler, G. Lu, and J. T. Yates, “Photocatalysis on TiOn Surfaces: Principles, Mechanisms, and Selected Results,” 1995.

- Fan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Semiconductor-based nanocomposites for photocatalytic H2 production and CO2 conversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 15, 2632–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Solar Energy Storage in an All-Vanadium Photoelectrochemical Cell: Structural Effect of Titania Nanocatalyst in Photoanode. Energies 2022, 15, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholam, R.; Patel, N.; Adami, M.; Miotello, A. Physically and chemically synthesized TiO2 composite thin films for hydrogen production by photocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 6896–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourikas, K.; Kordulis, C.; Lycourghiotis, A. Titanium Dioxide (Anatase and Rutile): Surface Chemistry, Liquid–Solid Interface Chemistry, and Scientific Synthesis of Supported Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9754–9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitputti, J.; Pavasupree, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshikawa, S. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity for water-splitting reaction of nanocrystalline mesoporous titania prepared by hydrothermal method. J. Solid State Chem. 2007, 180, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, G.L.; Selli, E.; Forni, L. Photocatalytic hydrogen production over flame spray pyrolysis-synthesised TiO2 and Au/TiO2. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2008, 84, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. E. Karakitsou and X. E. Verykios’, “Effects of Altervalent Cation Doping of Ti02 on Its Performance as a Photocatalyst for Water Cleavage,” 1993.

- M. V Rao, K. M. V Rao, K. Rajeshwar, V. R. Pal Verneker, and J. Dubow, “Photosyntlhetic Production of H2 and H202 on Semiconducting Oxide Grains in Aqueous Solutlons,” 1980.

- Kolen’ko, Y.; Churagulov, B.; Kunst, M.; Mazerolles, L.; Colbeau-Justin, C. Photocatalytic properties of titania powders prepared by hydrothermal method. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2004, 54, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreethawong, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshikawa, S. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution of nanocrystalline mesoporous titania prepared by surfactant-assisted templating sol–gel process. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Kominami and B. Ohtani, “Preparation of Titanium Oxide-Based Powders and Thin Films of High Photocatalytic Activities Using Solvothermal Methods,” 2010, pp. 113–132. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Ying, J.Y. Sol−Gel Synthesis and Hydrothermal Processing of Anatase and Rutile Titania Nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 3113–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreethawong, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshikawa, S. Photocatalytic evolution of hydrogen over nanocrystalline mesoporous titania prepared by surfactant-assisted templating sol–gel process. Catal. Commun. 2005, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzhak, A.V.; Ermokhina, N.I.; Stroyuk, A.L.; Bukhtiyarov, V.K.; Raevskaya, A.E.; Litvin, V.I.; Kuchmiy, S.Y.; Ilyin, V.G.; Manorik, P.A. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over mesoporous TiO2/metal nanocomposites. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2008, 198, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, W. Interfacial Charge Transport in 1D TiO2 Based Photoelectrodes for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Small 2019, 17, e1903378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Gutiérrez, M.; Rivero, E.; Cruz-Díaz, M.; Niño-Gómez, M.; Pedraza-Avella, J. Photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen production from oilfield-produced wastewater in a filter-press reactor using TiO2-based photoanodes. Catal. Today 2016, 266, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramian, A.; Rezaeivala, M.; He, K.; Dionysiou, D.D. Enhanced visible-light photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution through degradation of methyl orange in a cell based on coral-like Pt-deposited TiO2 thin film with sub-2 nm pores. Catal. Today 2018, 335, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldo, T.; Gonçales, V.; Silva, B.; de Torresi, S.; Zanoni, M. Hydrogen production and simultaneous photoelectrocatalytic pollutant oxidation using a TiO2/WO3 nanostructured photoanode under visible light irradiation. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015, 765, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chou, L.; Bi, Y. Tuning surface electronegativity of BiVO4 photoanodes toward high-performance water splitting. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 262, 118267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshay, V.R.; Arun, B.; Mandal, G.; Mutta, G.R.; Chanda, A.; Vasundhara, M. Observation of Optical Band-Gap Narrowing and Enhanced Magnetic Moment in Co-Doped Sol–Gel-Derived Anatase TiO2 Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 26592–26604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q. Mechanism of higher photocatalytic activity of anatase TiO2doped with nitrogen under visible-light irradiation from density functional theory calculation. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2007, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Hajra, S.; Irshad, M.; Usman, M.; Imran, M.; Assiri, M.A.; Ashraf, W.M. Hydrogen Production Using TiO2-Based Photocatalysts: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 25640–25648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseler, O.; Shankar, M.V.; Karkmaz-Le Du, M.; Schmidlin, L.; Keller, N.; Keller, V. Solar light photocatalytic hydrogen production from water over Pt and Au/TiO2(anatase/rutile) photocatalysts: Influence of noble metal and porogen promotion. J. Catal. 2010, 269, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, G.; Sadanandam, G.; Ledwaba, K.; Maroju, R. An efficient photocatalytic synthesis of benzimidazole over cobalt-loaded TiO2 catalysts under solar light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2022, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.T.; Gillan, E.G. Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution from Transition-Metal Surface-Modified TiO2. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2947–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchet, D.; Santos, J.B.O.; Damyanova, S.; Gallo, J.M.R.; Bueno, J.M.C. Toward Understanding Metal-Catalyzed Ethanol Reforming. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3841–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Jaroniec, M.; Yu, J.; Ran, J.; Qiao, S.-Z. Metal–organic framework with atomically dispersed Ni–N4 sites for greatly-raised visible-light photocatalytic H2 production. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.W.; Ran, J.; Zhuang, Z.W.; Chen, C.; Qiao, S.Z.; Li, Y.D.; Wang, G.X. Atomically dispersed Ni in cadmium-zinc sulfide quantum dots for high-performance visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-H.; Huang, B.-K. Photocatalytic Degradation of Using Ni-Containing TiO2. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, L. Study on the synthesis of Ni doped mesoporous TiO2 and its photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution in aqueous methanol solution. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 415, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholam, R.; Patel, N.; Adami, M.; Miotello, A. Hydrogen production by photocatalytic water-splitting using Cr- or Fe-doped TiO2 composite thin films photocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 5337–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-W.; Sun, D.; Zou, Y.; Ma, D.; He, C.; Ji, X.; Niu, C. Trap-level-tunable Se doped CdS quantum dots with excellent hydrogen evolution performance without co-catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 364, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, D.; An, L.; Hou, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H. Ni-Mo nanoparticles as co-catalyst for drastically enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production activity over g-C3N4. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 243, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Gao, F.; Feng, W.; Liu, P. CdS nanorods decorated with inexpensive NiCd bimetallic nanoparticles as efficient photocatalysts for visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 243, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanu, D.; Recchia, S.; Mohajernia, S.; Tomanec, O.; Kment. ; Zboril, R.; Schmuki, P.; Altomare, M. Templated Dewetting–Alloying of NiCu Bilayers on TiO2 Nanotubes Enables Efficient Noble-Metal-Free Photocatalytic H2 Evolution. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5298–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.-Y.; Kang, M. Effect of Al-Cu Bimetallic Components in a TiO2Framework for High Hydrogen Production on Methanol/Water Photo-Splitting. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Fan, J.; Liu, E.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Dai, H.; Yang, Y.; Hou, W.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Z. Fe and Ni co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by alcohol-thermal method: Application in hydrogen evolution by water splitting under visible light irradiation. Powder Technol. 2012, 228, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Liu, E.; Fan, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, F.; Hou, W.; Yang, Y.; Kang, L. High photocatalytic activity of hydrogen production from water over Fe doped and Ag deposited anatase TiO2 catalyst synthesized by solvothermal method. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Tian, W.; Meng, A.; Yang, L. CoNi Bimetal Cocatalyst Modifying a Hierarchical ZnIn2S4 Nanosheet-Based Microsphere Noble-Metal-Free Photocatalyst for Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 20190–20201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.Y.; Kandiel, T.A.; Oekermann, T.; Bahnemann, D. Photocatalytic Activities of Different Well-defined Single Crystal TiO2 Surfaces: Anatase versus Rutile. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 2461–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, N.; Chong, F.; Dutta, B.K.; Man, Z.B.; Khan, M.S.; Nurlaela, E. Photodegradation of Orange II under visible light using Cu–Ni/TiO2: Effect of calcination temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 185-186, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, F.; Nakata, M.; Asami, K.; Yamakata, A. Photocatalytic activity of titania particles calcined at high temperature: Investigating deactivation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 579, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Lee, C.-Y.; Yeng, M.-Y.; Chiu, H.-T. The effect of calcination temperature on the crystallinity of TiO2 nanopowders. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 247, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-M.; Yi, G.-R.; Moon, J.H.; Heo, C.-J.; Yang, S.-M. Superhydrophobic Films of Electrospun Fibers with Multiple-Scale Surface Morphology. Langmuir 2007, 23, 7981–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Niu, X.; Zheng, L.; Ding, X. The preparation of Zn2+-doped TiO2 nanoparticles by sol–gel and solid phase reaction methods respectively and their photocatalytic activities. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyong, Y.; Bensimon, M.; Sarria, V.; Stolitchnov, I.; Jardim, W.; Laub, D.; Mielczarski, E.; Mielczarski, J.; Kiwi-Minsker, L.; Kiwi, J. ZnSO4–TiO2 doped catalyst with higher activity in photocatalytic processes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2007, 76, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, B.; Gulicovski, J.; Dohčević-Mitrović, Z.; Bučevac, D.; Prekajski, M.; Zagorac, J.; Matović, B. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3+ doped titanium dioxide nanopowders. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padikkaparambil, S.; Yaakob, Z.; Narayanan, B.N.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Viswanathan, S. Novel preparation method of nanosilver doped sol gel TiO2 photocatalysts for dye pollutant degradation. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, L.; Chong, F.; Dutta, B.K. Development of copper-doped TiO2 photocatalyst for hydrogen production under visible light. Energy 2009, 34, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angkaew, S.; Limsuwan, P. Preparation of silver-titanium dioxide core-shell (Ag@TiO2) nanoparticles: Effect of Ti-Ag mole ratio. Procedia Eng. 2012, 32, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, D.; Akbal, F. Photocatalytic Degradation of Textile Dye and Wastewater. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2010, 216, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adán, C.; Bahamonde, A.; Fernández-García, M.; Martínez-Arias, A. Structure and activity of nanosized iron-doped anatase TiO2 catalysts for phenol photocatalytic degradation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2007, 72, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Huo, Y.; Zhu, J. Supercritical Preparation of a Highly Active S-Doped TiO2 Photocatalyst for Methylene Blue Mineralization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4410–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Wang, P.; Ding, D.; Liu, J.; Ren, Z.; Fu, H. Effect of surface species on Cu-TiO2 photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2569–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.M.; Bashiri, R.; Kait, C.F.; Sufian, S. Photocatalytic water splitting over titania supported copper and nickel oxide in photoelectrochemical cell; optimization of photoconversion efficiency. 348, 0120; 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.-L.; Chen, G.; Yu, J.C. Simultaneous photocatalytic removal of ammonium and nitrite in water using Ce3+–Ag+ modified TiO2. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 67, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Enhanced photocatalytic activity for titanium dioxide by co-modification with copper and iron. Transit. Met. Chem. 2010, 35, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogawa, T.; Isobe, T.; Matsushita, S.; Nakajima, A. Preparation and visible-light photocatalytic activity of Au- and Cu-modified TiO2 powders. Mater. Lett. 2012, 82, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongwisate, P.; Chavadej, S.; Gulari, E.; Sreethawong, T.; Rangsunvigit, P. Effects of monometallic and bimetallic Au–Ag supported on sol–gel TiO2 on photocatalytic degradation of 4-chlorophenol and its intermediates. Desalination 2011, 272, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, T.-C.; Chang, F.-W.; Roselin, L.S. Production of hydrogen via partial oxidation of methanol over bimetallic Au–Cu/TiO2 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2008, 293, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jin, R.; Chen, J.; Guan, X.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, F.; Guan, N. Titania-supported bimetallic catalysts for photocatalytic reduction of nitrate. Catal. Today 2004, 90, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B.; Babacan, O.; Kafizas, A.; Hankin, A. A Review of Inorganic Photoelectrode Developments and Reactor Scale-Up Challenges for Solar Hydrogen Production. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Niu, S.; Han, D.; Liu, T.; Wang, G.; Li, Y. Progress in Developing Metal Oxide Nanomaterials for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Vanka, S.; Wang, Y.; Gim, J.; Wang, Y.; Ra, Y.-H.; Hovden, R.; Guo, H.; Shih, I.; Mi, Z. Solar Water Oxidation by an InGaN Nanowire Photoanode with a Bandgap of 1.7 eV. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shen, X.; Shen, S.; Reese, M.O.; Hu, S. Stable CdTe Photoanodes with Energetics Matching Those of a Coating Intermediate Band. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Pu, Y.-C.; Zhang, J.Z.; Tong, Y.; Li, Y. An electrochemical method to enhance the performance of metal oxides for photoelectrochemical water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 2849–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Hisatomi, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Teshima, K.; Nakabayashi, M.; Shibata, N.; Nishiyama, H.; Katayama, M.; Yamada, T.; et al. Highly Active GaN-Stabilized Ta3 N5 Thin-Film Photoanode for Solar Water Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4739–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, D.; Xu, P.; Xue, W.; Lei, L.; Cheng, M.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Deng, R. Semiconductor-based photocatalysts for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting: will we stop with photocorrosion? J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 2286–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, P. Mechanisms of water photooxidation at n-TiO2 rutile single crystal oriented electrodes under UV illumination in competition with photocorrosion. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2011, 86, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Fan, Z.; Nakabayashi, M.; Ju, H.; Pastukhova, N.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, C.; Shibata, N.; Domen, K.; Li, Y. Interface engineering of Ta3N5 thin film photoanode for highly efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Jia, S.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X. General and Robust Photothermal-Heating-Enabled High-Efficiency Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanyam, P.; Kumar, P.N.; Deepa, M.; Subrahmanyam, C.; Ghosal, P. Bismuth sulfide nanocrystals and gold nanorods increase the photovoltaic response of a TiO2/CdS based cell. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 159, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, P.; Vinodkumar, T.; Nepak, D.; Deepa, M.; Subrahmanyam, C. Mo-doped BiVO4@reduced graphene oxide composite as an efficient photoanode for photoelectrochemical water splitting. 9th International Symposium on Group Five Elements. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 73–80.

- Subramanyam, P.; Meena, B.; Suryakala, D.; Deepa, M.; Subrahmanyam, C. Plasmonic nanometal decorated photoanodes for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Catal. Today 2020, 379, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cushing, S.K.; Zheng, P.; Senty, T.; Meng, F.; Bristow, A.D.; Manivannan, A.; Wu, N. Solar Hydrogen Generation by a CdS-Au-TiO2 Sandwich Nanorod Array Enhanced with Au Nanoparticle as Electron Relay and Plasmonic Photosensitizer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8438–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dahoudi, N.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, G. Low-Temperature Processing of Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles Photoanodes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Renew. Energy 2012, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Peng, T.; Lu, L.; Cai, P.; Jiang, P.; Bian, Z. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Photoelectrochemical Properties of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Made with Mesoporous TiO2 Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 8486–8494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, R.; Fan, K.; Peng, T. Effects of annealing conditions on the photoelectrochemical properties of dye-sensitized solar cells made with ZnO nanoparticles. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, R.; Mohamed, N.M.; Kait, C.F.; Sufian, S. Effect of heat treatment on the physical properties of bimetallic doped catalyst, Cu-Ni/TiO2. PROCEEDINGS OF THE 23RD SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE OF MICROSCOPY SOCIETY MALAYSIA (SCMSM 2014). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MalaysiaDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Zhang, L.J.; Zheng, R.; Li, S.; Liu, B.K.; Wang, D.J.; Wang, L.L.; Xie, T.F. Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Generation on Cadmium Sulfide Nanorods with Cobalt Hydroxide as Cocatalyst and Insights into Their Photogenerated Charge Transfer Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 13406–13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M. Porous Cupric Oxide: Efficient Photocathode for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Sakamoto, M.; Jiu, J.; Ogata, Y.; Isoda, S. Determination of Parameters of Electron Transport in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 13872–13880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, G.; Wheeler, D.A.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y. Sn-Doped Hematite Nanostructures for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2119–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, M.; Puukilainen, E.; Ritala, M.; Leskelä, M. Effect of thickness of ALD grown TiO2 films on photoelectrocatalysis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2009, 204, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z. Effects of TiO2 film thickness on photovoltaic properties of dye-sensitized solar cell and its enhanced performance by graphene combination. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 49, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-M.; Wu, J.-M.; Yan, M. Photocatalytic and photoelectrocatalytic degradation of aqueous Rhodamine B by low-temperature deposited anatase thin films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 112, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, Y.; Appel, P.; Rietveld, L.C. Optimisation of parameters in a solar light-induced photoelectrocatalytic process with a TiO2/Ti composite electrode prepared by paint-thermal decomposition. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2015, 305, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.L.; Marsen, B.; Paluselli, D.; Rocheleau, R. Optimization of Hybrid Photoelectrodes for Solar Water-Splitting. Electrochem. Solid-state Lett. 2005, 8, A247–A249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Barnes, P.R.F.; Bertram, W.; Luca, V. Strong photoresponse of nanostructured tungsten trioxide films prepared via a sol–gel route. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyarthi, V.S.; Hofmann, M.; Savan, A.; Sliozberg, K.; König, D.; Beranek, R.; Schuhmann, W.; Ludwig, A. Enhanced photoelectrochemical properties of WO3 thin films fabricated by reactive magnetron sputtering. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 4724–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Jun, H.; Lee, J.S. Nanocrystalline WO3 film with high photo-electrochemical activity prepared by polymer-assisted direct deposition. Scr. Mater. 2010, 63, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.M.; Bashiri, R.; Kait, C.F.; Sufian, S.; Khatani, M. Investigation of photoconversion efficiency of Cu and Ni doped TiO2 thin film in photoelectrochemical cell. 4TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON FUNDAMENTAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES (ICFAS2016). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, MalaysiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 050022.

- Mishra, P.; Shukla, P.; Srivastava, O. Study of modular PEC solar cells for photoelectrochemical splitting of water employing nanostructured TiO2 photoelectrodes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Shinde, P.S.; Go, G.H.; Ramasamy, E. Ag grid induced photocurrent enhancement in WO3 photoanodes and their scale-up performance toward photoelectrochemical H2 generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 5262–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Döscher et al., “Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency: shining light on photoelectrochemical device performance,” in AIChE Annual Meeting, Conference Proceedings, American Institute of Chemical Engineers, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, R.; Mohamed, N.M.; Kait, C.F.; Sufian, S. Optimization of hydrogen production over TiO2 supported copper and nickel oxides: effect of photoelectrochemical features. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2018, 49, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, N.; Takeuchi, M.; Kimura, T.; Oka, T. Existence of optimum space between electrodes on hydrogen production by water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2003, 28, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, M.A.; Tahvildari, K.; Bigdeli, T. Eco-friendly synthesis of biodiesel from WCO by using electrolysis technique with graphite electrodes. Fuel 2020, 270, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzer, B.; Selcuk, H.; Chehade, G.; Demir, M.; Dincer, I. Evaluation of hydrogen production via electrolysis with ion exchange membranes. Energy 2019, 190, 116420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S.; Saracco, G.; Alexe-Ionescu, A.; Barbero, G. Electric investigation of a photo-electrochemical water splitting device based on a proton exchange membrane within drilled FTO-covered quartz electrodes: under dark and light conditions. Electrochimica Acta 2014, 144, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of Operating Parameters on Performance of Alkaline Water Electrolysis. 01-902-664-9706 2015, 09. [CrossRef]

- Riegel, H.; Mitrovic, J.; Stephan, K. Role of mass transfer on hydrogen evolution in aqueous media. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1997, 28, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, J.E.; Thorpe, J.F. Void Fraction and Current Density Distributions in a Water Electrolysis Cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1969, 116, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshikawa, T.; Yamada, M.; Kikuchi, R.; Eguchi, K. Impedance Analysis of Internal Resistance Affecting the Photoelectrochemical Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, E68–E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curteanu, S.; Piuleac, C.G.; Godini, K.; Azaryan, G. Modeling of electrolysis process in wastewater treatment using different types of neural networks. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 172, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M.; Sedahmed, G. Effect of gas evolution on the rate of mass transfer at vertical electrodes. Electrochimica Acta 1972, 17, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Terrones, M.; Hare, J.; Terrones, H.; Kroto, H.; Walton, D. Electrolytic formation of carbon nanostructures. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 262, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Will, G.; Bell, J. Light intensity effects on photocatalytic water splitting with a titania catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 6938–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.M.; Bashiri, R.; Chong, F.K.; Sufian, S.; Kakooei, S. Photoelectrochemical behavior of bimetallic Cu–Ni and monometallic Cu, Ni doped TiO2 for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 14031–14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.H.; Jeong, S.M.; Kim, S.D.; Gyenis, J. Photocatalytic decomposition of NO by TiO2 particles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2000, 134, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Moon, K.J.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, D.; Kim, S.H. Effects of various light-intensity and temperature environments on the photovoltaic performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy 2015, 113, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wan, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Low, J.; Gao, X.; Fu, F. Synergistic effect of oxygen defect and doping engineering on S-scheme O-ZnIn2S4/TiO2-x heterojunction for effective photocatalytic hydrogen production by water reduction coupled with oxidative dehydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 430, 133125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayama, K.; Sugihara, H.; Arakawa, H. Photoelectrochemical Properties of a Porous Nb2O5 Electrode Sensitized by a Ruthenium Dye. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 3825–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Sayama and H. Arakawa+, “Effect of Na,CO, addition on photocatalytic decomposition of liquid water over various semiconductor catalysts,” 1994.

- Patsoura, A.; Kondarides, D.I.; Verykios, X.E. Enhancement of photoinduced hydrogen production from irradiated Pt/TiO2 suspensions with simultaneous degradation of azo-dyes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2006, 64, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; DuBois, D.L.; Roberts, J.A.S.; Shaw, W.J. Amino acid modified Ni catalyst exhibits reversible H 2 oxidation/production over a broad pH range at elevated temperatures. 111, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seadira, T.; Sadanandam, G.; Ntho, T.A.; Lu, X.; Masuku, C.M.; Scurrell, M. Hydrogen production from glycerol reforming: conventional and green production. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 695–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, H.; Rinderle, M.; Freitag, R.; Benesperi, I.; Edvinsson, T.; Socher, R.; Gagliardi, A.; Freitag, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells under ambient light powering machine learning: towards autonomous smart sensors for the internet of things. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.; Zhao, C.; You, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W. Recent progress of thin-film photovoltaics for indoor application. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 31, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian O’Regan and Michael Grätzel, “A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films,” Nature, vol. 353, pp. 737–740, 1991.

- Liu, S.; Yuan, J.; Deng, W.; Luo, M.; Xie, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zou, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, H.; Cao, Y. High-efficiency organic solar cells with low non-radiative recombination loss and low energetic disorder. Nat. Photon- 2020, 14, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burschka, J.; Pellet, N.; Moon, S.-J.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Gao, P.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 2013, 499, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, M.; Talebi, P.; Zhou, J.; Asgari, S.; Soomro, S.A.; Elsehrawy, F.; Halme, J.; Ahmad, S.; Hagfeldt, A.; Hashmi, S.G. Advanced research trends in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 10527–10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Teuscher, J.; Saygili, Y.; Zhang, X.; Giordano, F.; Liska, P.; Hua, J.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Moser, J.-E.; Grätzel, M.; et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells for efficient power generation under ambient lighting. Nat. Photon- 2017, 11, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grätzel, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2003, 4, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A.; Boschloo, G.; Sun, L.; Kloo, L.; Pettersson, H. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6595–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Sun, L. Iodine-free redox couples for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 10592–10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Yella, A.; Gao, P.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Curchod, B.F.E.; Ashari-Astani, N.; Tavernelli, I.; Rothlisberger, U.; Nazeeruddin, K.; Grätzel, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells with 13% efficiency achieved through the molecular engineering of porphyrin sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazeeruddin, Mohammad K., Filippo De Angelis, Simona Fantacci, Bessho Takeru, and Michael Grätzel., “Combined Experimental and DFT-TDDFT Computational Study of Photoelectrochemical Cell Ruthenium Sensitizers,” J Am Chem Soc, vol. 127, no. 48, pp. 16835–16847, 2005.

- Tennakone, K.; Senadeera, G.K.R.; Perera, V.P.S.; Kottegoda, I.R.M.; De Silva, L.A.A. Dye-Sensitized Photoelectrochemical Cells Based on Porous SnO2/ZnO Composite and TiO2 Films with a Polymer Electrolyte. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 2474–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asagoe, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ngamsinlapasathian, S.; Yoshikawa, S. TiO2-Anatase Nanowire Dispersed Composite Electrode for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. 61, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Z. Design methods for large scale dye-sensitized solar modules and the progress of stability research. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 3178–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastrawan, R.; Beier, J.; Belledin, U.; Hemming, S.; Hinsch, A.; Kern, R.; Vetter, C.; Petrat, F.M.; Prodi-Schwab, A.; Lechner, P.; et al. New interdigital design for large area dye solar modules using a lead-free glass frit sealing. Prog. Photovoltaics: Res. Appl. 2006, 14, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späth, M.; Sommeling, P.M.; van Roosmalen, J.A.M.; Smit, H.J.P.; van der Burg, N.P.G.; Mahieu, D.R.; Bakker, N.J.; Kroon, J.M. Reproducible manufacturing of dye-sensitized solar cells on a semi-automated baseline. Prog. Photovoltaics: Res. Appl. 2003, 11, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fuel | HHV (kJ/g) | LHV (kJ/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 141.9 | 119.9 |

| Methane | 55.5 | 50.0 |

| Gasoline | 47.5 | 44.5 |

| Diesel | 44.8 | 42.5 |

| Methanol | 20.0 | 18.1 |

| Process | Hydrogen Production Method | Feedstocks | Brief description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical energy | Electrolysis | Water | Conversion of electric power to chemical energy in the form of H2 and O2 as a by-product of water with two reactions in each electrode; anode and cathode | [11] [12] |

| Plasma arc decomposition | Natural gas | H2 and carbon soot were produced through methane decomposition in a plasma reactor with a parallel set of screw type helix and rod-like electrodes | [37] |

|

| Thermal energy | Thermolysis | Water | Steam is brought to temperature of over 2500K at which water molecule decomposes thermally into H2 and O2 | [38] |

| Thermocatalysis H2S cracking |

Hydrogen sulfide | Sufficient heat is supplied to break down H2S into H2 and S2 | [39] | |

| Biomass conversion |

Biomass | Thermocatalytic conversion of biomass to H2 | [40] | |

| Thermochemical processes Water splitting |

Water | Water decomposition through a repetitive series of chemical reactions using intermediate reactions and substances which are all recycled during the process so that the overall reactions is equivalent to the dissociation of the water molecule into H2 and O2 | [41] | |

| Gasification | Biomass | Biomass steam gasification converts carbonaceous material to permanent gases (H2, CO, CO2, CH4 and light hydrocarbon), char and tar | [42] | |

| Reforming | Biofuels | Transformation of exhaust heat into the chemical energy of a new synthetic fuel that has higher calorimetric properties such as low heating value | [43] | |

| H2S splitting | Hydrogen sulfide | Decompose H2S into H2S and S2 over two reaction steps; creating and then decomposing hydroiodic acid. | [44] | |

| Photonic energy | PV-electrolysis | Water | The system is equipped with 20 W photovoltaic panel to generate electricity and drive electrolyzer which is exposed to direct solar radiation till mid noon | [45] |

| Photocatalysis | Water | For H2 production, the conduction band level should be more negative than hydrogen production level while the valence band should be more positive than water oxidation level for efficient O2 production from water by photocatalysis | [46] | |

| Photoelectrochemical | Water | H2 and O2 are generated from water dissociation on the surface of PEC materials with enough solar energy absorption and proper use of electrolysis | [47] | |

| Bio-photolysis | Water | Under anaerobic condition, the cyanobacterium carries out the biological fixation of atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3), concurrently producing H2 as by-product | [48] | |

| Biochemical energy | Dark fermentation | Biomass | In dark fermentation, substrates are converted by anaerobic bacteria grown in the dark | [49] |

| Enzymatic | Water | A synthetic enzymatic pathway consisting of 13 enzymes for producing hydrogen from starch and water | [50] |

| No | Year | Description | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2004 | Dr. Aldo Steinfeld's work in the field of solar thermochemical hydrogen generation aligns with the broader efforts to harness solar energy for sustainable and low-carbon hydrogen production. | [61] |

| 2. | 2009 | The work conducted by Yilanci et al. involving a PV/fuel cell system that harnesses concentrated solar energy to produce hydrogen is indicative of advancements in sustainable hydrogen production. | [56] |

| 3. | 2011 | The study conducted by González et al., which investigates hydrogen generation using various methods, including photochemical, electrochemical, and thermochemical processes driven by solar energy, is indicative of comprehensive research into sustainable hydrogen production. | [51] |

| 4. | 2012 | The work conducted by Ngoh and Njomo, which involved a hydrogen generation experiment using hybrid thermochemical cycles and concentrated solar energy, addresses an important aspect of solar-driven hydrogen production. Their findings, particularly the emphasis on solar-to-electricity conversion efficiency as a key factor in overall hydrogen generation efficiency, highlight a crucial consideration in the development of sustainable hydrogen production technologies. | [62] |

| 5. | 2012 | The research conducted by Xiao et al., which focuses on solar energy-driven hydrogen production through a thermochemical cycle, sheds light on the challenges and potential advancements in this field. One of the key takeaways from their work is the importance of developing a reactor that can simultaneously perform the synthesis and hydrolysis of reduced metal/oxide nanoparticles, along with the capacity to recover the regenerated oxide particles. | [63] |

| 6. | 2013 | The work conducted by Chaubey et al., which involves the development of a hydrogen-based method utilizing concentrated solar energy in biological, electrochemical, and thermochemical processes, showcases a multidisciplinary approach to sustainable hydrogen production. Their research likely explores various methods for harnessing concentrated solar energy to generate hydrogen while emphasizing the use of biomass as a clean and renewable resource. | [64] |

| 7. | 2015 | The research by Agrafiotis et al. contributes to the understanding of concentrated solar energy applications in thermochemical hydrogen and syngas production. Such processes are essential for developing clean and sustainable pathways for hydrogen and syngas production, aligning with the goals of reducing carbon emissions and advancing renewable energy technologies. | [65] |

| 8. | 2016 | The work by Dan Zhao et al., involving the use of TiO2 and CdS nanocomposites, is related to the development of materials with applications in solar energy storage, photocatalysis, and particularly in photocatalytic hydrogen production and water splitting. | [66] |

| 9. | 2017 | The review conducted by Villafán-Vidales et al. on the thermochemical process of hydrogen production using concentrated solar energy likely provides a comprehensive overview of the various steps and considerations involved in this innovative and sustainable approach. | [66] |

| 10. | 2017 | By addressing the challenge of TiO2's wide bandgap and enhancing its light-absorbing capabilities, Wang et al.'s research likely contributes to the advancement of photocatalytic processes for solar-driven hydrogen production, which is a critical component of sustainable and clean energy systems. Blackening TiO2 can improve solar absorption and thus contribute to the improvement of solar-hydrogen efficiency. | [67] |

| 11. | 2018 | The review conducted by Jun Chi et al., which focuses on different water electrolysis processes and their various operating characteristics, is likely a comprehensive examination of electrolysis methods for hydrogen production. | [35] |

| 12. | 2019 | The research conducted by Kuan-Yeow Show et al., involving the use of laboratory-scale systems to produce biohydrogen from microalgae with the assistance of solar energy, is a significant contribution to the field of renewable energy and sustainable hydrogen production. | [68] |

| 13. | 2020 | The work conducted by Chao Zhou et al., which focuses on niobium-based semiconductors for photocatalysis, represents an important area of research within the field of solar-driven hydrogen production. | [69] |

| 14. | 2021 | The review conducted by Chen and Hainin focuses on the topic of photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting, specifically delving into the principles and development of Sb2Se3 photocathodes within this context. | [70] |

| 15. | 2021 | Jung Eun Lee et al. addresses the use of metal oxides, metal halides, and sulfur oxides in thermochemical processes for hydrogen production, with a focus on mitigating excessive temperature rise and stress on metal oxides during redox reactions. | [71] |

| 16. | 2022 | Rengui Li et al. appears to focus on the concept of a water splitting panel and a hydrogen farm, particularly in the context of photocatalyst particulate and the photocatalytic water splitting method. | [72] |

| 17. | 2022 | Muhammad Usman et al. appears to focus on the discussion of composites involving Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) for sustainable hydrogen production and portable energy harvesting applications. | [73] |

| Photoanode material | Electrolyte | Illumination | Performance | Advantage | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface modified TiO2 nanotube arrays |

NaOH | 300 W xenon lamp (100 mW.cm-2) equipped with an AM 1.5 G filter | Incident photon-current conversion efficiency = 36% at 350 nm |

Reduced charge carrier recombination and improved hole injection efficiency | H2 production | [117] |

| TiO2 films prepared by sol–gel dip-coating |

KCl, MgCl2, CaCl2, Phenol and Na2SO4 (simulated wastewater) or oilfield-produced wastewater | 150 W metal-halide lamp with UV filter | rH2 = 12.36 mmol/h and 80% phenol degradation (simulated wastewater) rH2 = 9.11 mmol/h (oil field-produced wastewater) |

Low-cost, reduced toxicity, remarkable stability | H2 production and wastewater treatment | [142] |

| Photoanode material | Electrolyte | Illumination | Performance | Advantage | Application | Ref. |

| TiO2/Pt/FTO | Methyl orange, methanol and Na2SO4 |

400 W xenon lamp (100 mW.cm-2) equipped with optical filters |

Quantum Yield = 3.70% at λ=420nm rH2 = 11.4 mmol/h |

Enhanced charge separation | H2 production and wastewater treatment | [142] |

| TiNT/WO3/Ti | RB5 dye and Na2SO4 | 125 W high-pressure Hg lamp (12.55 mWcm-2) | H2 generation efficiency = 46% | Enhanced charge separation | H2 production and wastewater treatment | [143] |

| TiO2-1 wt% Au@TiO2/ Al2O3/Cu2O |

Humic acid and Na2SO4 | 150 W xenon lamp (100 mW.cm-2) equipped with an AM 1.5G filter |

Solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency = 0.5% and 87% humic acid degradation |

Self-biased PEC. Enhanced charge separation. Wide spectral absorption | H2 production and wastewater treatment | [144] |

| Photocatalyst | Light source | H2 Production Efficiency | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | UV irradiation | 200 μmol.h-1 | [161] |

| Au/TiO2 | 150W metal halide lamp | 120 μmol.min-1 | [148] |

| Ag/TiO2 | UV irradiation | 147.9 ± 35.5 μmol.h-1.g-1 for anatase Ag/TiO24.65 ± 0.39 μmol.h-1.g-1 for amorphous TiO2 | [11] |

| Co/TiO2 | 300 W Xe lamp | 11, 021 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [96] |

| Co/TiO2 | 8500 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [150] | |

| Ni/TiO2 | visible light irradiation (λ > 420 nm) | 21 712 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [152] |

| Al/TiO2 | UV irradiation | 312 μmol.h-1 | [161] |

| Cu/TiO2 | UV irradiation | 900 μmol.h-1 | [161] |

| Ni/ZCS QDs | 18.87 mmol.h−1.g−1 | [153] | |

| Ni/TiO2 | 300W high pressure Hg lamp | 185 μmol.h-1 | [155] |

| Fe/TiO2 | 250 W tungsten halogen lamp | 15.5 μmol.h-1 | [156] |

| Cr/TiO2 | 250 W tungsten halogen lamp | 5.3 μmol.h-1 | [156] |

| CdS0.9Se0.1 QDs | simulated solar irradiation (320–780 nm) | 29.12 mmol.h−1.g−1 | [157] |

| Ni-Mo/g-C3N4 | 1785 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [158] | |

| NiCd/CdS | under visible light irradiation (λ>410 nm) | 11.57 mmol·h−1·g−1 | [159] |

| NiCu-TiO2 | filtered illumination (λ>420nm) | 0.02μL.h-1cm-2 | [160] |

| Al-Cu/TiO2 | UV irradiation | 1093 μmol.h-1 | [161] |

| Fe-Ni/TiO2 | 500W Xenon lamp | 361.64 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [162] |

| Fe-Ag/TiO2 | Hg lamp (λ=254 nm) and 500W Xenon lamp | 515.45 μmol.h-1.g-1 | [163] |

| CoNi-ZIS | under visible light irradiation (λ>420 nm) | 100.1 μmol.h-1 | [164] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).