1. Introduction

Many hydrophilic antioxidants, such as vitamin C, allicin, and melatonin, have been developed and marketed to react with oxidants in the cell cytoplasm and the blood plasma [

1]. On the other hand, water-soluble antioxidants have limitations in inhibiting lipid peroxidation in the cell membranes because of the low interaction with the hydrophobic interface [

2]. The development of lipid-soluble antioxidants is more advantageous to prevent oxidative damage to the cell membrane in a nonpolar environment [

3]. Many chronic aging-related diseases are frequently associated with oxidative damage in cell membranes by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [

4,

5], which have amphipathic properties between water and lipid interfaces. On the other hand, lipid-soluble antioxidants, such as carotenoids, vitamin E, coenzyme Q

10 (CoQ

10), docosahexaenoic (DHA), and beeswax alcohol (BWA), are well-known nutrients with the potential to protect the cell membrane and to treat chronic aging-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases [

6]. These compounds may prevent the cell membranes from damage by free radicals by readily scavenging peroxyl radicals, preventing lipid and protein oxidation in the amphipathic interface of plasma membrane in brain cells, neurons, and glia [

7]. Nevertheless, in vitro evidence has not been sufficiently accumulated to prove the mechanistic insight of the antioxidants due to their low solubility in water.

Beeswax alcohol (BWA), a substance purified from beeswax, contains a mixture of six primary aliphatic alcohols (C24, C26, C28, C30, C32, and C34) with antioxidant, anti-platelet, cholesterol-lowering, and gastroprotective effects [

8,

9]. In particular, BWA supplementation promoted the secretion and quality of gastric mucus in ethanol-ulcer rat models and attenuated inflammation in antigen-induced arthritis [

10,

11]. With these properties, BWA has been registered as a functional food ingredient to help protect the body from oxidative stress, maintain a healthy stomach by protecting the gastric mucosa, and maintain joint health in Korean health functional foods according to the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS,

https://www.foodsafetykorea.go.kr/portal/board/board Detail.do?menu_grp=MENU_NEW01&menu_no=2660&bbs_no=bbs987&nticmatr_yn=N&bbs_type_cd=01&ans_yn=N&ntctxt_no=21590). Oral acute treatment with BWA (5–100 mg/kg) reduces gastric ulceration and malondialdehyde (MDA) formation, a marker of lipid peroxidation, in the gastric mucosa of rats with indomethacin or ischemia reperfusion-induced ulcers [

12,

13]. The administration of BWA, 25–200 mg/kg, into rats by oral gavage revealed potent anti-inflammatory activity with a significant reduction of leukotriene B

4 (LTB

4) against carrageenan-induced pleuritic inflammation [

14].

An in vitro assay of the BWA has been a limitation in evaluating the antioxidant capacity because of their extreme insolubility in the physiological aqueous buffer system. An isotonic aqueous buffer was selected to solubilize BWA for enzyme assay, cell-based assay, and animal experiments. The hurdle was overcome by incorporating BWA into reconstituted high-density lipoproteins (rHDL) with apoA-I to evaluate the antioxidant capacities of BWA in the physiological buffer system, according to a previous report [

15]. The current study compared the in vitro effects of rHDL containing BWA (BWA-rHDL) and encapsulation of BWA into rHDL particles on the anti-glycation, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. The anti-glycation activity of BWA-rHDL was evaluated by testing the fructose or carboxymethyllysine (CML)-mediated glycation with HDL, which causes inflammation with neurotoxicity [

16]. Among the AGE, an elevated serum

N--carboxymethyllysine (CML) level was also associated with the exacerbation of atherosclerosis via lipoprotein modifications and increased susceptibility of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) oxidation [

17]. The antioxidant properties of the BWA have been compared using zebrafish embryos by testing the developmental speed, swimming ability, and survivability after the injection of the rHDL-BWA in the presence of the CML. Zebrafish embryos have well-developed innate and acquired immune systems like mammalian ones [

18]. An additional advantage of working with zebrafish embryos is external development and optically transparent during development. With these characteristics, zebrafish and their embryos are a valuable and popular animal model for various studies, including screening of antioxidants [

19], wound healing [

20], and tissue regeneration [

21].

This study was designed to compare the physicochemical characterizations of BWA-rHDL regarding particle size, morphology, and electromobility with the increased molar ratio of BWA. Each rHDL was evaluated in terms of the structural and functional correlations, antioxidant, anti-glycation, and anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo using zebrafish embryos and adults under acute hyperinflammation to provide information on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory of BWA in HDL in the physiological potential.

4. Discussion

Oxidative damage in the lipid and proteins of the cell membrane surface can induce cellular necrosis and apoptosis through chemical and biophysical changes in the lipid bilayer components via necrotic cell signaling [

35,

36]. Lipid hydroperoxide-modified protein adducts, such as

N-(hexanoyl)lysine, were also found in oxLDL with a positive correlation with the extent of oxidation [

37]. oxLDL could provoke acute cell death and foam cell formation by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines to build up atherosclerotic plaque [

38]. Therefore, inhibiting LDL oxidation is essential to prevent pro-inflammatory disease via suppressing ROS production, releasing adhesion molecules, the vicious cycle of inflammation, and apoptosis in the necrotic core while activating endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and platelets [

39]. On the other hand, the desirable antioxidant should protect HDL and apoA-I from oxidative modification, such as myeloperoxidase and lipoxygenase, and glycation stress, such as fructose and CML. Because HDL-associated paraoxonase activity is the principal power to exert inhibition of LDL oxidation, protection of HDL and apoA-I in the native state is essential for keeping the LDL healthy [

40]. Dysfunctional HDL lost antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, such as paraoxonase activity, therefore, dysfunctional HDL cannot protect LDL from oxidative stress [

41].

In general, lipid-soluble antioxidants protect cell membranes more efficiently from lipid peroxidation than water-soluble antioxidants, especially in oxidized lipids in the plasma membrane and inner membrane of mitochondria. Indeed, BWA in Tween 20 showed more potent inhibitory activity against LDL oxidation than that of vit C at lower concentrations (final 10–30 µM), as shown in

Figure 1. Although vit C inhibited LDL oxidation by myeloperoxidase in vitro, the dosage was too high to use practical application, such as 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM [

42]. In addition, vit C and E could not inhibit LDL oxidation by ferritin at lysosomal pH, which might help to explain why vit C and E did not reduce CVD in large clinical trials [

43]. Several phenolic compounds and flavonoids were developed as inhibitors of LDL oxidation [

44]; new pharmaceutical agents are needed to maximize the antioxidant, anti-glycation, protection of HDL, and stabilization of apoA-I via an interaction of amphipathic helix domain. Hence, HDL functionality is more important in exerting the protective effects of HDL against cardiovascular risk than the HDL-C quantity [

41]. Protection of apoA-I is critical to maintaining the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of HDL because apoA-I (28 kDa) is the principal protein component in HDL particles [

45]. Furthermore, apoA-I in a lipid-free state could exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, which can be impaired by nonenzymatic glycation [

29,

46].

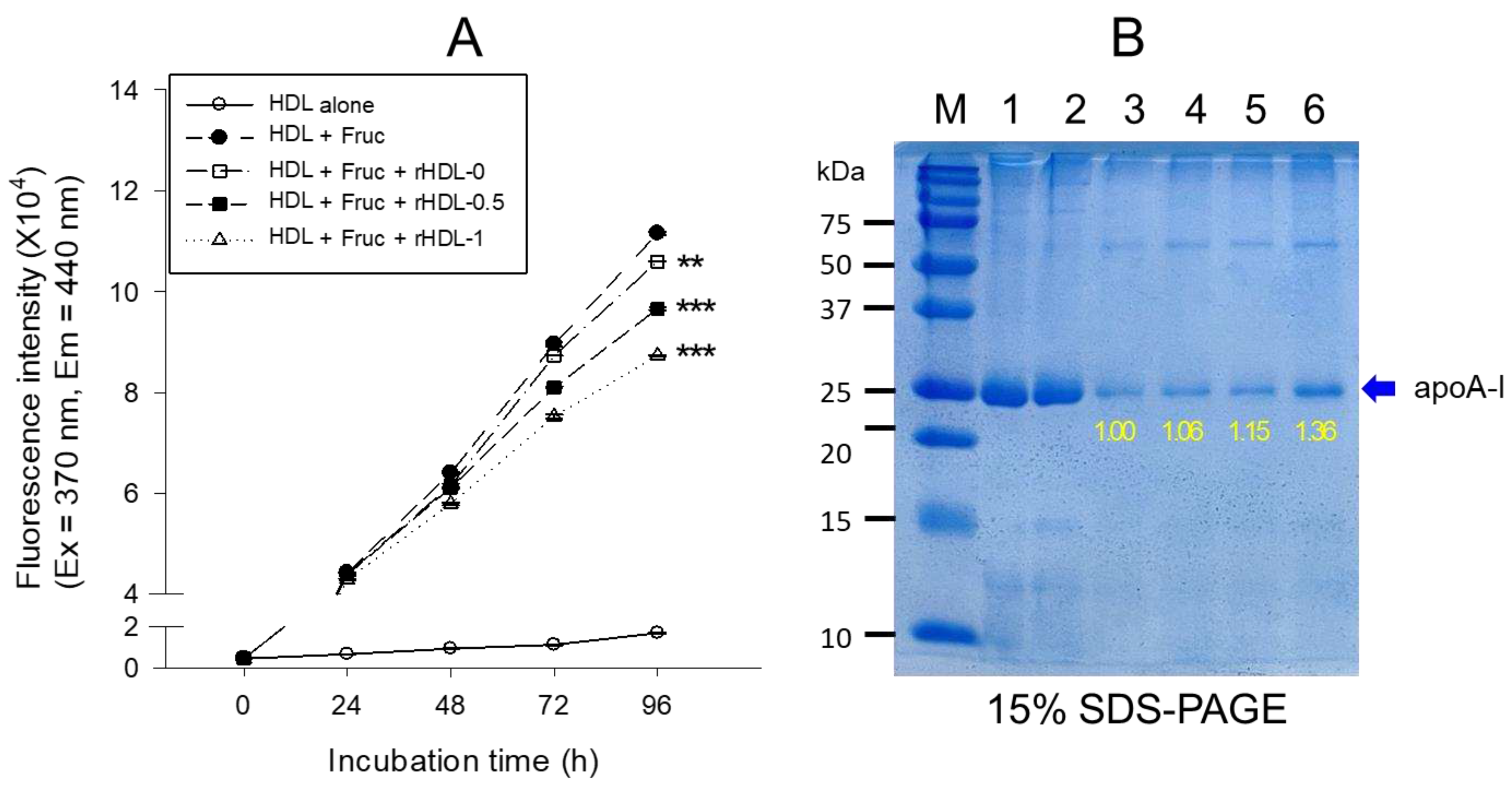

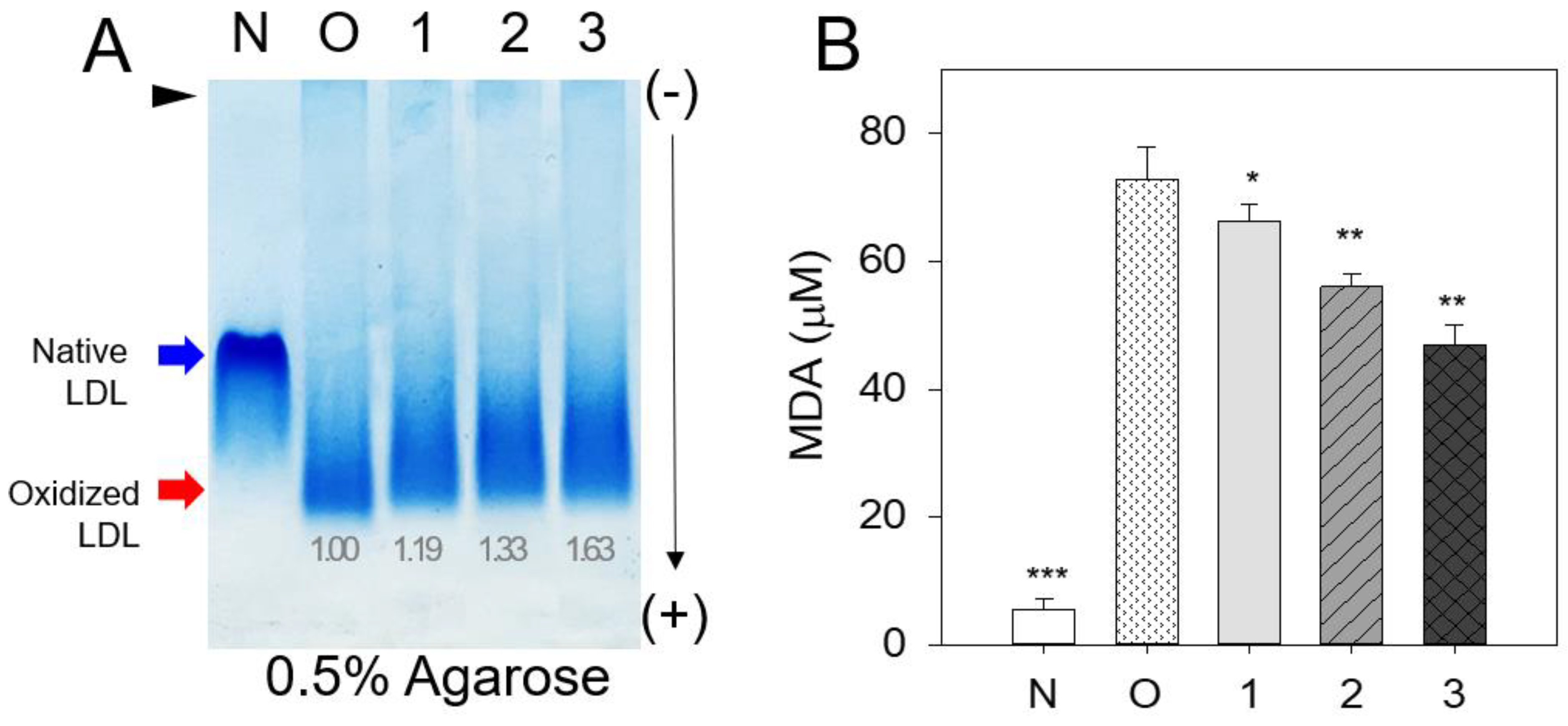

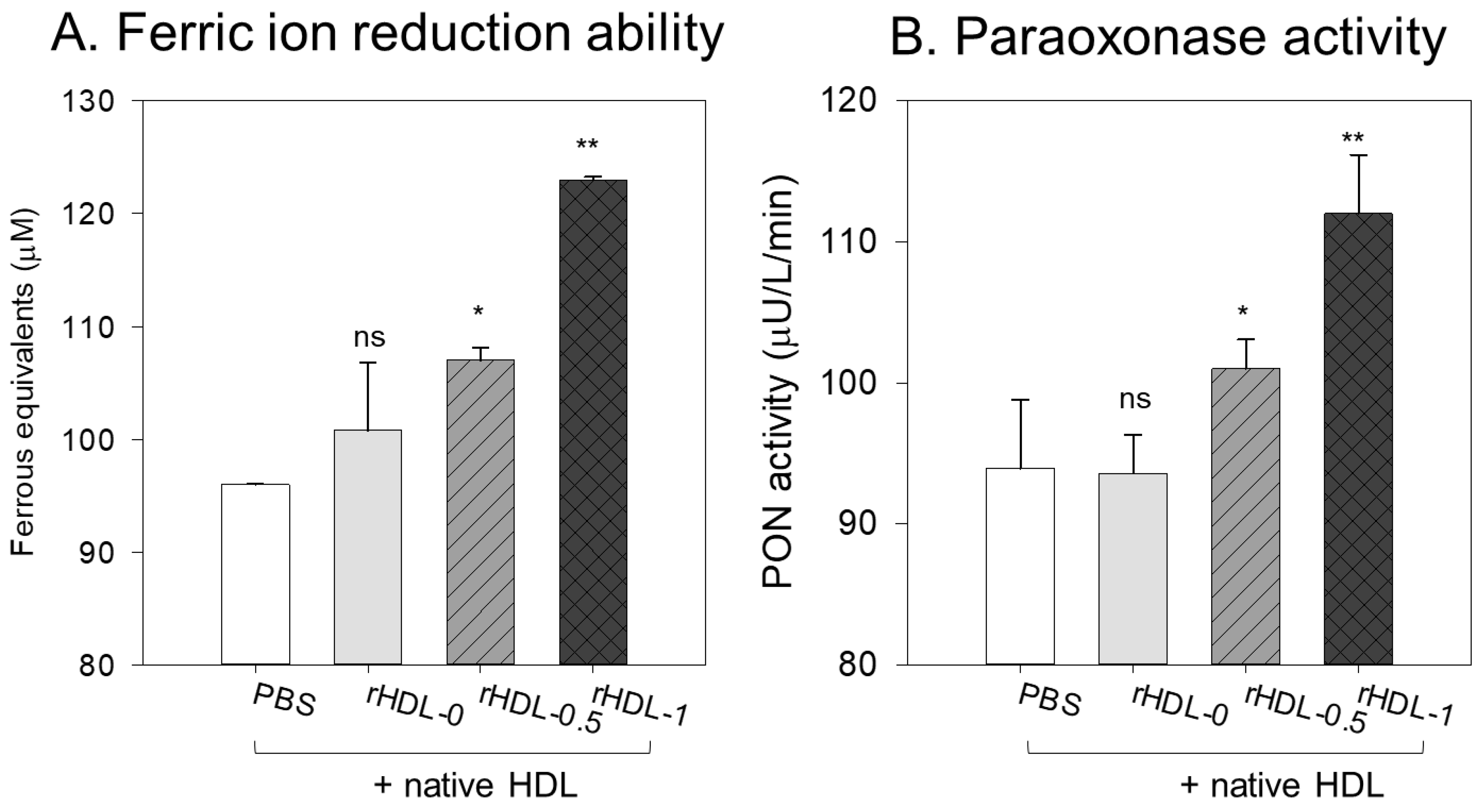

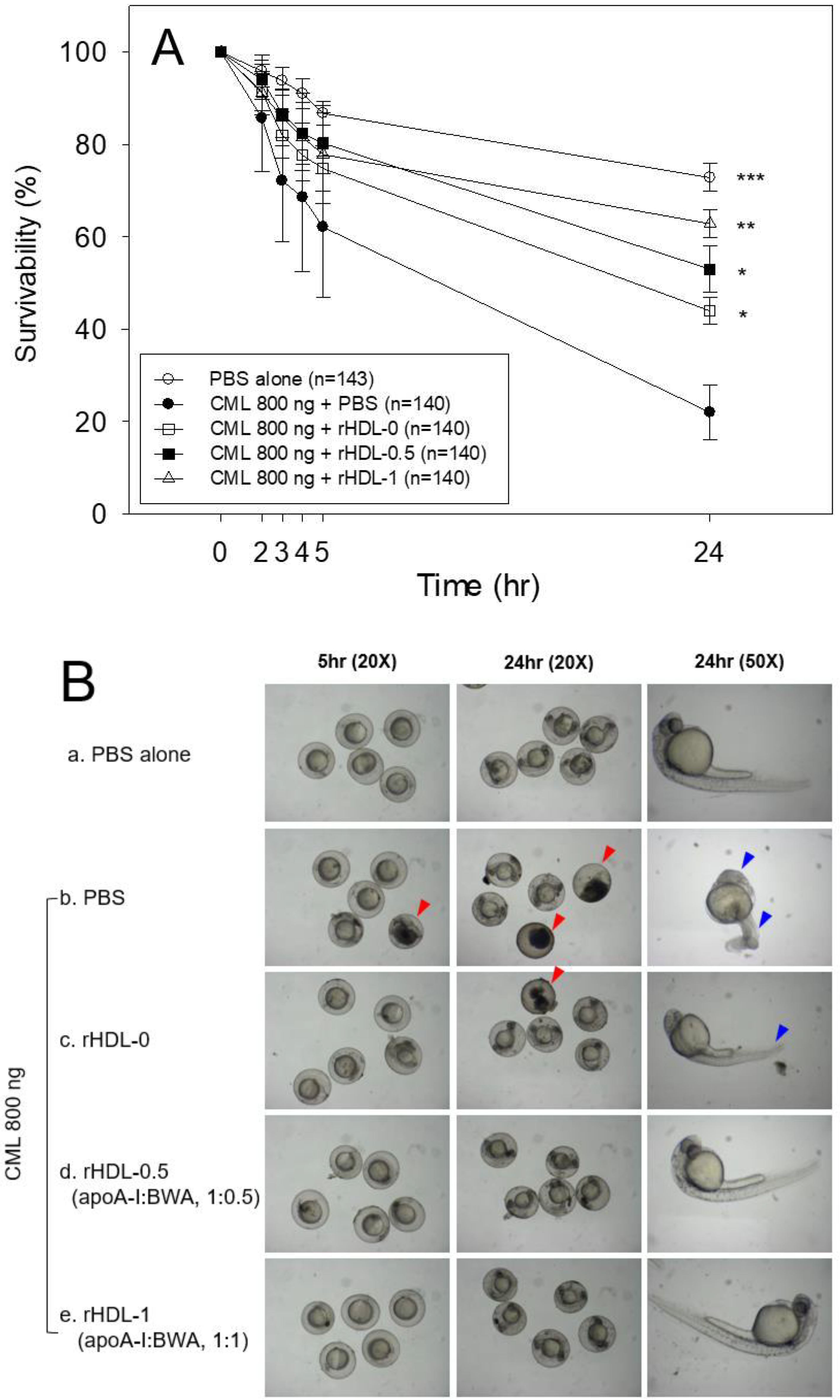

This study was designed to compare the structural-functional correlations of reconstituted HDL with the increase in BWA content under the same apoA-I content and maximize the antioxidant capacity of BWA in an aqueous buffer. The apoA-I in rHDL was more stabilized as the molar ratio of apoA-I:BWA increased to approximately 1:1 (

Figure 3). The rHDL particle morphology was changed to more distinct, and the size was larger (

Figure 4). Regarding functionality, the anti-glycation ability of rHDL containing was enhanced with more protection of apoA-I and less glycation in HDL in the presence of fructose (

Figure 5). The antioxidant ability of the rHDL was strengthened as the BWA molar ratio was increased to suppress cupric ion mediated LDL oxidation (

Figure 6). The FRA and PON activities of human HDL were enhanced remarkably by the rHDL as the BWA content was increased (

Figure 7). The rHDL containing BWA protected against embryo death from acute toxicity of CML by suppressing ROS production and apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (

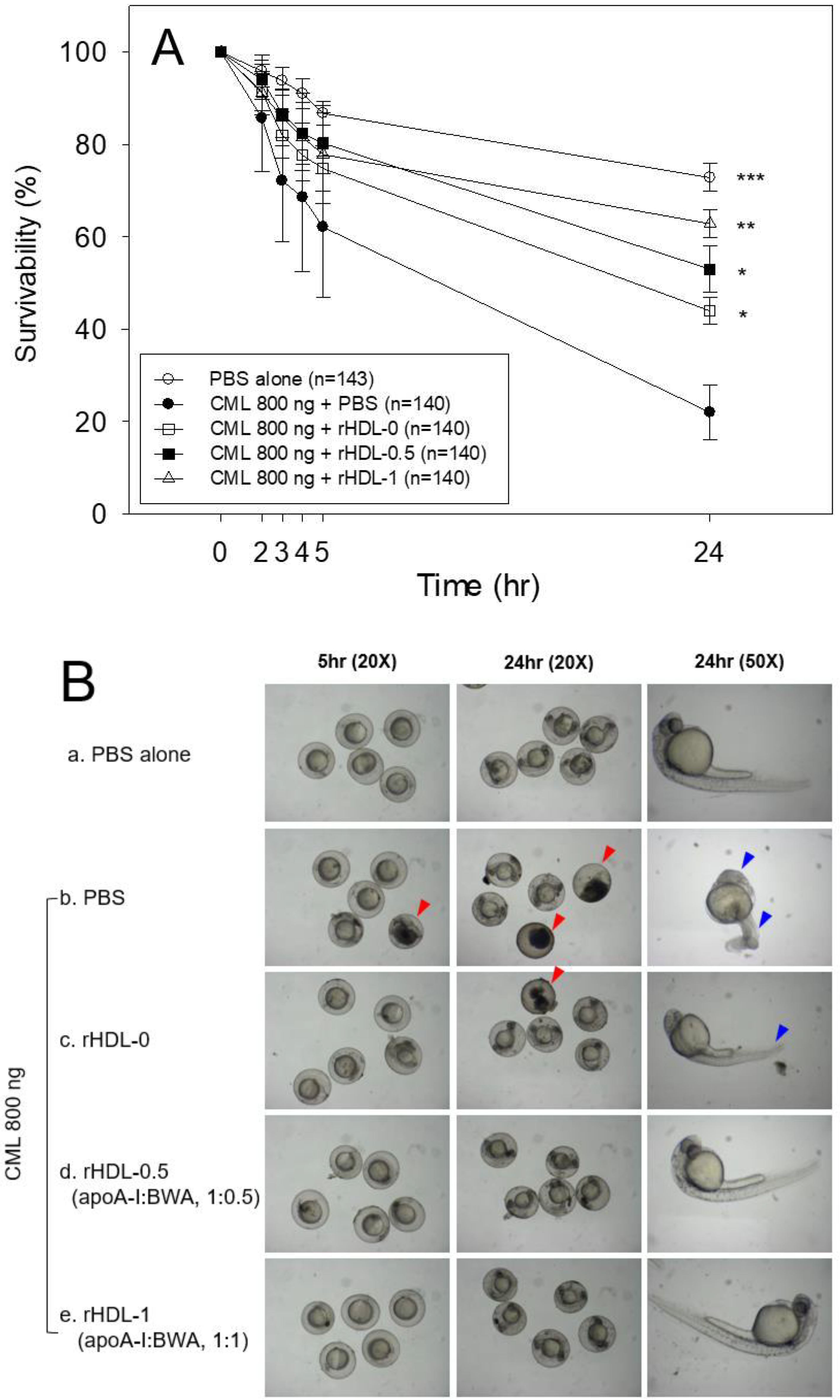

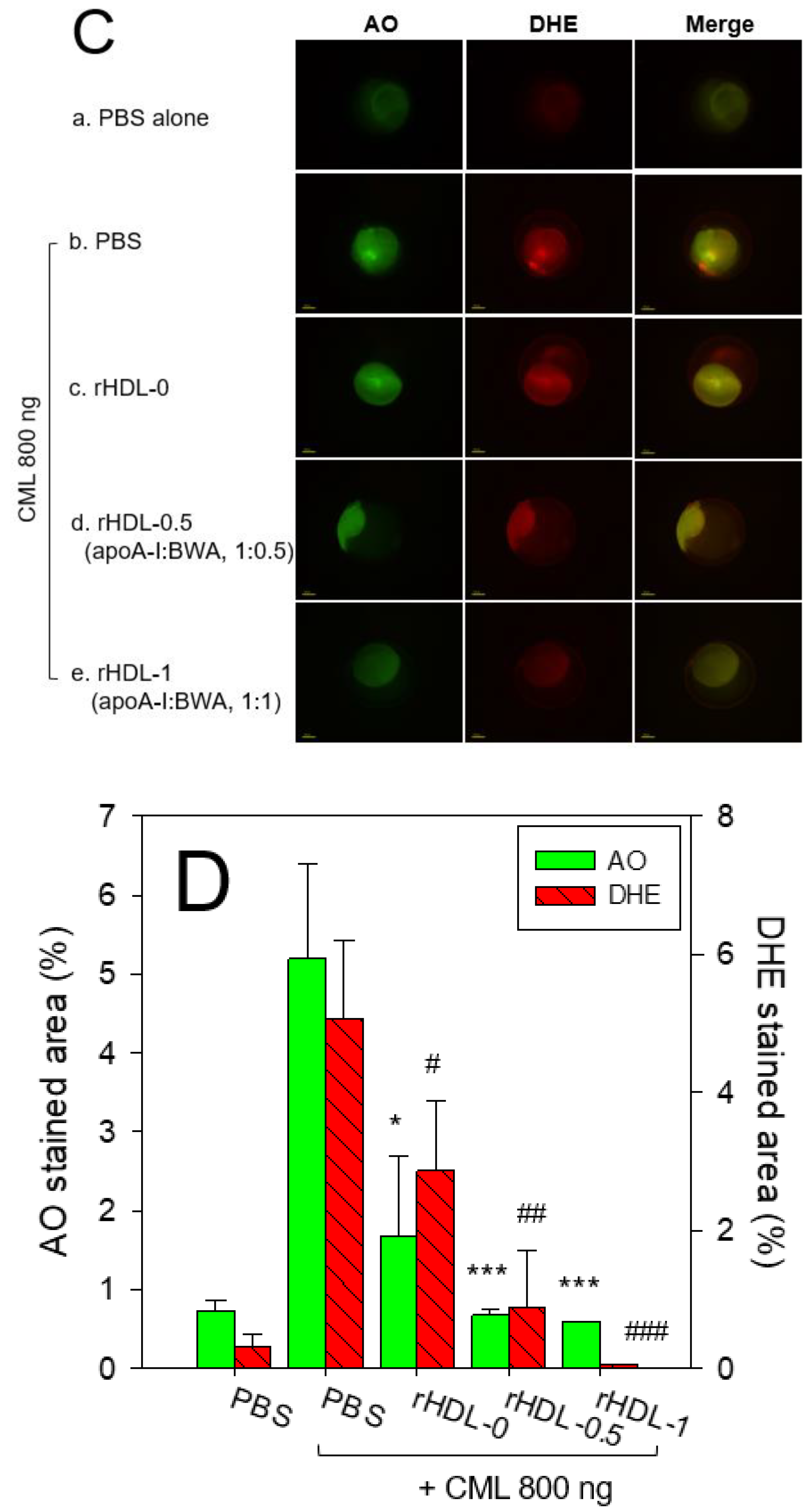

Figure 8). BWA in rHDL facilitated cutaneous wound healing activity under CML toxicity in adult zebrafish (

Figure 9).

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first study to show that BWA could bind with apoA-I and cholesterol to construct rHDL, suggesting that the six even number long chain aliphatic alcohols (C24, C26, C28, C30, C32, and C34) made a putative affinity interaction with amphipathic helix domain of apoA-I. As the BWA concentration was increased, the particle size of rHDL increased up to 15% with a 1.5 nm redshift of intrinsic Trp, suggesting that the Trp in apoA-I was exposed more to the polar phase upon binding with BWA. Interestingly, this behavior of fluorophore movement differed from rHDL synthesis with policosanol (PCO) in a previous report [

15]. A rHDL containing PCO (PCO-rHDL) showed a 1.9 nm blue shift of WMF, even though rHDL containing Cuban policosanol showed a 24% increase in particle diameter at 95:5:1:1 molar ratio for POPC:FC:apoA-I:PCO. The difference between BWA and PCO is two odd number aliphatic alcohols, C27 and C29 (1-hepacosanol and 1-nonacosanol, respectively), because policosanol is constituted with eight long chain aliphatic alcohols (C24, C26, C27, C28, C29, C30, C32, and C34). Although the incorporation of BWA and PCO caused an increase in the particle size of rHDL to a similar extent, but the movement of Trp in the amphipathic helix domain of apoA-I was different in the opposite direction. These results suggest that Trp108 of apoA-I showed different molecular motions and fluorophore environments between BWA-rHDL and PCO-rHDL by the putative interaction of C27 and C29. The intrinsic Trp108 was more exposed to the water phase BWA-rHDL, while PCO-rHDL showed more closed Trp108 toward the nonpolar phase of apoA-I. The BWA should have amphipathic properties between the water and lipid interfaces in the intercalated protein domain of the cell membrane to accomplish therapeutic activity for joint health benefits and gastroprotection.

On the other hand, the BWA-rHDL exerted stronger anti-glycation activity and antioxidant activity than rHDL alone, with an enhancement of the FRA and PON activities in HDL. Although many papers reported that BWA exhibited potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity from animal and human serum after oral supplementation, no study has identified the beneficial in vitro activity because of the insolubility in water. These enhancements of in vitro antioxidant activity of HDL by BWA-rHDL are in good agreement with previous in vivo reports that showed a decrease in various oxidized lipids and enzymes involved in inflammation, such as COX-2, by apoA-I in colon cancer and ovarian cancer [

47,

48]. In the same context, the consumption of BWA (5–100 mg/kg) lowered carboxyl groups (a marker of protein oxidation) and the generation of hydroxyl (*OH) radical and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (a marker of inflammation), and increased the catalase (CAT) activity in the gastric mucosa of rats with indomethacin ulcers [

49]. Lipid peroxidation is critical to induce acute gastric mucosal injuries, pro-inflammatory cascades, and carcinogenesis [

50,

51].

Despite the many papers from animal and human studies showing that supplementation of BWA ameliorated gastric ulcers, esophagitis, and osteoarthritis [

10,

11,

50], the in vitro antioxidant abilities of BWA and the mechanism of antioxidant activity after oral ingestion were not fully elucidated. Although BWA has adequate DPPH radical scavenging activity and ferric ion reduction ability in ethanol solvent assay systems [

52], the current results showed that the incorporation of BWA in rHDL resulted in more enhancement of HDL-associated PON and FRA activity to inhibit LDL oxidation. The encapsulation of BWA in the rHDL is needed to maintain its antioxidant activity to suppress LDL oxidation because an organic solvent or non-ionic detergent, e.g., Tween 20, for BWA, might be toxic (

Figure 1). The enforcement of HDL functionality by BWA encapsulation might be associated with the improvement of the barrier function by apoA-I stabilization (

Figure 3 and 4), reduction of glycation stress (

Figure 5) and oxidative stress (

Figure 6 and 7), inhibition of embryonic cell apoptosis (

Figure 7), and enhancement of wound healing (

Figure 9). The enhancement of the HDL quality and functionality by BWA was associated with that of 17 days BWA supplementation (10% in diet, wt./wt.) in ameliorating the liver function and dyslipidemia to suppress interleukin-6 by increasing HDL functionality in the ethanol-induced hepatic injury zebrafish model [

53].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the antioxidant ability between lipid-free BWA and vitamin C against cupric ion mediated LDL oxidation. A. Electromobility of LDL under a non-denatured state in the presence of Tween 20 and cupric ions with BWA or vit-C after 4 hr incubation at 37°C. Red-dotted line indicates the similar electromobility of native LDL (lane N) and BWA-treated ox-LDL (lane 6). B. Quantification of malondialdehyde in the LDL by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay. **, p<0.01.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the antioxidant ability between lipid-free BWA and vitamin C against cupric ion mediated LDL oxidation. A. Electromobility of LDL under a non-denatured state in the presence of Tween 20 and cupric ions with BWA or vit-C after 4 hr incubation at 37°C. Red-dotted line indicates the similar electromobility of native LDL (lane N) and BWA-treated ox-LDL (lane 6). B. Quantification of malondialdehyde in the LDL by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay. **, p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Anti-glycation ability of lipid-free BWA against CML-mediated glycation. A. Fluorescence intensity (Ex=370 nm, Em=440 nm) and wavelength maximum fluorescence (Ex=295 nm, Em=310-400 nm) of HDL3 in the presence of CML (final 400 µM) and BWA (final 10, 20, and 30 µM) at 144 hr incubation. *, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; **, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; #, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; ##, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML. B. Electrophoretic patterns of HDL in the presence of CML (final 400 µM) and BWA (final 10, 20, and 30 µM) at 72 hr and 144 hr incubation (15% SDS-PAGE). The protein bands were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The red font indicates the band intensity of apoA-I from three independent SDS-PAGE. Lane N, native HDL; lane M, molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad, prestained low-range). .

Figure 2.

Anti-glycation ability of lipid-free BWA against CML-mediated glycation. A. Fluorescence intensity (Ex=370 nm, Em=440 nm) and wavelength maximum fluorescence (Ex=295 nm, Em=310-400 nm) of HDL3 in the presence of CML (final 400 µM) and BWA (final 10, 20, and 30 µM) at 144 hr incubation. *, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; **, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; #, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML; ##, p<0.05 vs. HDL + CML. B. Electrophoretic patterns of HDL in the presence of CML (final 400 µM) and BWA (final 10, 20, and 30 µM) at 72 hr and 144 hr incubation (15% SDS-PAGE). The protein bands were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The red font indicates the band intensity of apoA-I from three independent SDS-PAGE. Lane N, native HDL; lane M, molecular weight marker (Bio-Rad, prestained low-range). .

Figure 3.

Electrophoretic profiles of rHDL containing BWA in the denatured state (A) and non-denatured state (B). A. Electrophoretic patterns of each rHDL under the denatured state on 14% SDS-PAGE (9 μg of protein/lane). The red arrowhead indicates phospholipid and BWA debris. The gel was stained by Coomassie brilliant blue (final 0.125%) staining to visualize apoA-I and phospholipid. Lane M, molecular weight standard (Precision plus protein standards, Bio-Rad Cat # 161-0374); lane 1, lipid-free apoA-I alone; lane 2, rHDL-0; lane 3, rHDL-0.5; lane 4, rHDL-1. B. Native electrophoresis of each rHDL under the non-denatured state on 0.6% agarose (10 μg of protein/lane) to compare the electromobility depends on the three-dimensional structure of apoA-I/HDL and its oxidation extent. The apoA-I in rHDL was visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (final 1.25 %). Lane 1, rHDL-0; lane 2, rHDL- 0.5; lane 3, rHDL-1.

Figure 3.

Electrophoretic profiles of rHDL containing BWA in the denatured state (A) and non-denatured state (B). A. Electrophoretic patterns of each rHDL under the denatured state on 14% SDS-PAGE (9 μg of protein/lane). The red arrowhead indicates phospholipid and BWA debris. The gel was stained by Coomassie brilliant blue (final 0.125%) staining to visualize apoA-I and phospholipid. Lane M, molecular weight standard (Precision plus protein standards, Bio-Rad Cat # 161-0374); lane 1, lipid-free apoA-I alone; lane 2, rHDL-0; lane 3, rHDL-0.5; lane 4, rHDL-1. B. Native electrophoresis of each rHDL under the non-denatured state on 0.6% agarose (10 μg of protein/lane) to compare the electromobility depends on the three-dimensional structure of apoA-I/HDL and its oxidation extent. The apoA-I in rHDL was visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (final 1.25 %). Lane 1, rHDL-0; lane 2, rHDL- 0.5; lane 3, rHDL-1.

Figure 4.

TEM image analysis of each rHDL containing BWA with 40,000 magnification. Among rHDLs, rHDL-1, (apoA-I: BWA, 1:1) (C) had the largest size, as shown in inset graph (D). The rHDL-1 exhibited the most distinct and uniform discoidal particle shape with a rouleaux pattern.

Figure 4.

TEM image analysis of each rHDL containing BWA with 40,000 magnification. Among rHDLs, rHDL-1, (apoA-I: BWA, 1:1) (C) had the largest size, as shown in inset graph (D). The rHDL-1 exhibited the most distinct and uniform discoidal particle shape with a rouleaux pattern.

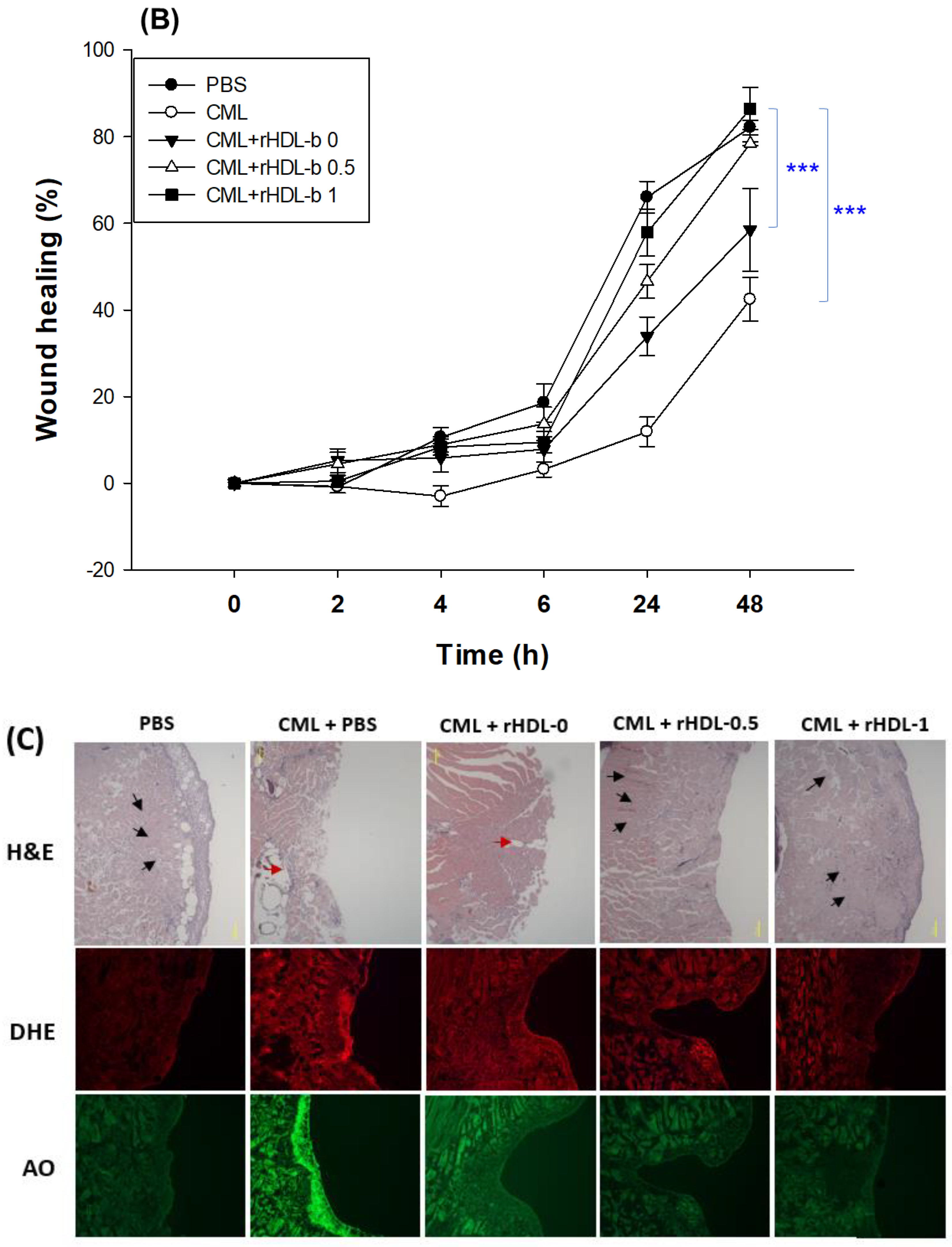

Figure 5.

Anti-glycation activity of rHDL-containing BWA in fructose-treated HDL. A. Fluorescence spectroscopic analysis (Ex = 370 nm, Em = 440 nm) of HDL (1 mg/mL of protein), which was co-treated with fructose (final 250 mM) and each rHDL (0.2 mg/mL of apoA-I) containing BWA (final 1.3 and 2.6 μg/mL for rHDL-0.5 and rHDL-1, respectively) during 96 h incubation. The data were expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples. ***, p < 0.001 vs. HDL2 + Fruc. Each rHDL treatment was compared with HDL2 + Fruc by independent t-test. B. Electrophoretic patterns of the HDL (5 μg/lane) after incubation with fructose and each rHDL (15% SDS-PAGE). M, molecular weight standard (Precision plus protein standards, Bio-Rad Cat # 161-0374). The protein bands were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue (final 0.125%) staining. M represents molecular weight marker (kDa), lane 1, HDL alone (0 h); lane 2, HDL alone (72 h); lane 3, HDL + Fruc; lane 4, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-0; lane 5, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-0.5; and lane 6, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-1.

Figure 5.

Anti-glycation activity of rHDL-containing BWA in fructose-treated HDL. A. Fluorescence spectroscopic analysis (Ex = 370 nm, Em = 440 nm) of HDL (1 mg/mL of protein), which was co-treated with fructose (final 250 mM) and each rHDL (0.2 mg/mL of apoA-I) containing BWA (final 1.3 and 2.6 μg/mL for rHDL-0.5 and rHDL-1, respectively) during 96 h incubation. The data were expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples. ***, p < 0.001 vs. HDL2 + Fruc. Each rHDL treatment was compared with HDL2 + Fruc by independent t-test. B. Electrophoretic patterns of the HDL (5 μg/lane) after incubation with fructose and each rHDL (15% SDS-PAGE). M, molecular weight standard (Precision plus protein standards, Bio-Rad Cat # 161-0374). The protein bands were visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue (final 0.125%) staining. M represents molecular weight marker (kDa), lane 1, HDL alone (0 h); lane 2, HDL alone (72 h); lane 3, HDL + Fruc; lane 4, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-0; lane 5, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-0.5; and lane 6, HDL + Fruc + rHDL-1.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the antioxidant abilities of rHDL-containing BWA during cupric-ion-mediated LDL oxidation. A. Comparison of the relative electromobility of a mixture of LDL (15 μg of protein) and each rHDL (6 μg of protein) under a non-natured state on 0.5% agarose gel (120 mm length 60 mm width 5 mm thickness). The electrophoresis was carried out with 50 V for 1 h in Tris-acetate-ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) buffer (PH 8.0). The apo-B in LDL was visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (final 1.25%). B. Extent of oxidation according to a TBARS assay with the malondialdehyde (MDA) standard. Each rHDL treatment was compared with LDL + CuSO4 (oxLDL) by independent t-test. The data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples. *, p < 0.05 vs. oxLDL alone **, p < 0.01 vs. oxLDL alone. lane N, native LDL; lane O, oxLDL; lane 1, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-0; lane 2, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-0.5; lane 3, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-1.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the antioxidant abilities of rHDL-containing BWA during cupric-ion-mediated LDL oxidation. A. Comparison of the relative electromobility of a mixture of LDL (15 μg of protein) and each rHDL (6 μg of protein) under a non-natured state on 0.5% agarose gel (120 mm length 60 mm width 5 mm thickness). The electrophoresis was carried out with 50 V for 1 h in Tris-acetate-ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) buffer (PH 8.0). The apo-B in LDL was visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (final 1.25%). B. Extent of oxidation according to a TBARS assay with the malondialdehyde (MDA) standard. Each rHDL treatment was compared with LDL + CuSO4 (oxLDL) by independent t-test. The data are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples. *, p < 0.05 vs. oxLDL alone **, p < 0.01 vs. oxLDL alone. lane N, native LDL; lane O, oxLDL; lane 1, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-0; lane 2, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-0.5; lane 3, LDL + CuSO4 + rHDL-1.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the ferric ion reduction ability (FRA) (A) and the paraoxonase (PON-1) activity (B) in HDL. *, p < 0.05 vs. HDL alone; **, p < 0.01 vs. HDL alone; ns, not significant vs. HDL alone. A. The FRA activity was expressed as the equivalent concentration of vitamin C (μM), which is equivalent to reducing the amount of ferric ion (μM) per hour. B. The PON-1 activity was expressed as the initial velocity of p-nitrophenol production per min (μU/L/min) at 37 °C during 180 min of incubation. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the ferric ion reduction ability (FRA) (A) and the paraoxonase (PON-1) activity (B) in HDL. *, p < 0.05 vs. HDL alone; **, p < 0.01 vs. HDL alone; ns, not significant vs. HDL alone. A. The FRA activity was expressed as the equivalent concentration of vitamin C (μM), which is equivalent to reducing the amount of ferric ion (μM) per hour. B. The PON-1 activity was expressed as the initial velocity of p-nitrophenol production per min (μU/L/min) at 37 °C during 180 min of incubation. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments with duplicate samples.

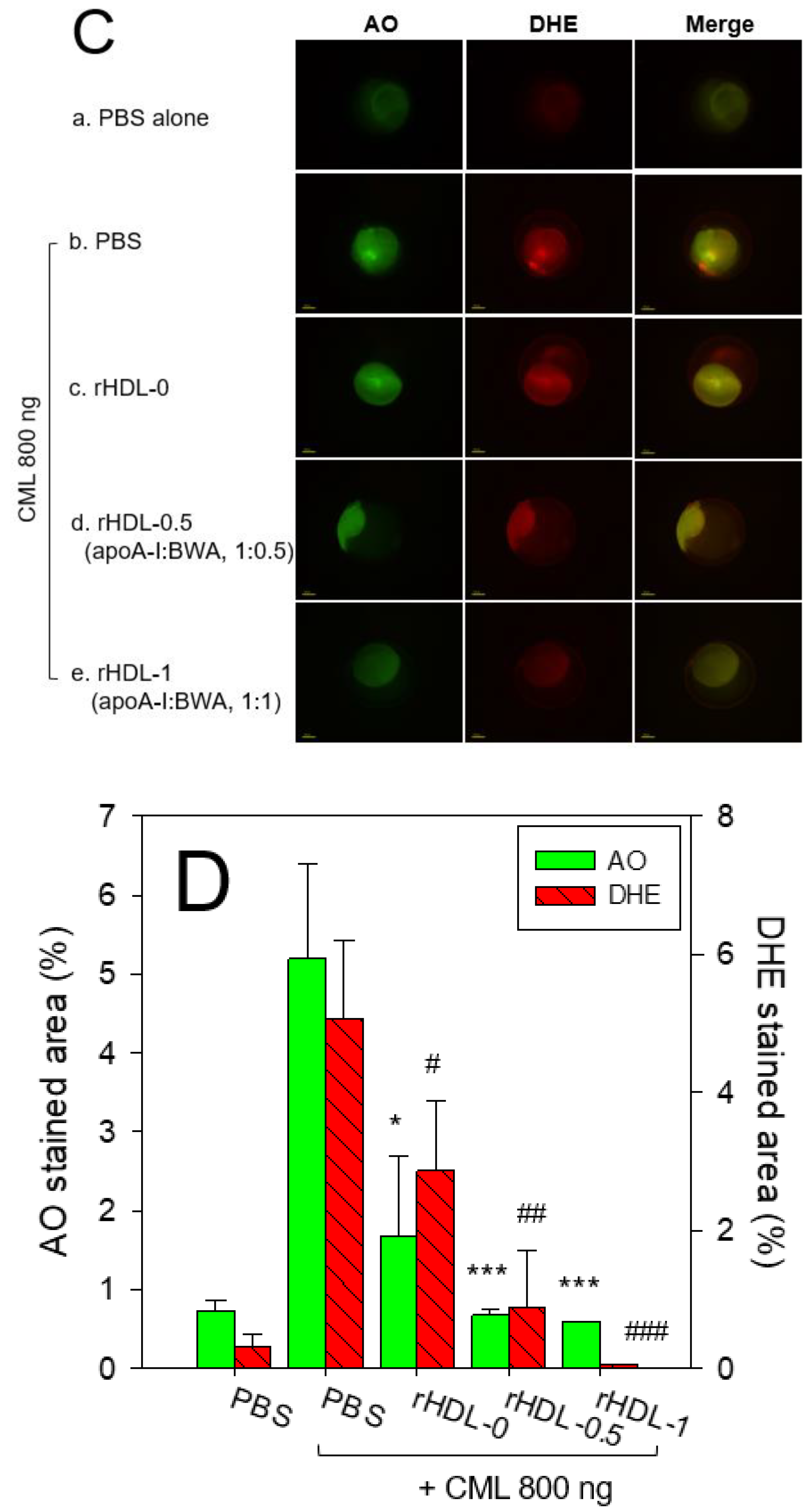

Figure 8.

Comparison of survivability and embryo development among rHDLs containing BWA in the presence of carboxymethyllysine (CML, final 800 ng). A. Survivability of embryos during 24 hr post-injection of each rHDL and CML from three independent experiments. *,

p < 0.05; **,

p < 0.01; ***,

p < 0.05 vs. CML alone. Statistical differences of multiple groups were compared using an independent

t-test. B. Developmental morphology of the embryo at 5 hr and 24 hr post-injection. The red arrowheads indicate defects of development and death of embryos in the CML alone group (photo b) and CML + rHDL-0 (photo c). The blue arrowheads indicate the slowest developmental speed in eye pigmentation and tail elongation in the CML alone group (photo b) and CML + rHDL-0 group (photo c) at 24 h post-injection. C. Fluorescence image of acridine orange (AO, Ex = 505 nm, Em = 535 nm) stained and dihydroethidium (DHE, Ex=585 nm, Em=615 nm) stained embryo at 5 hr post-injection. The extent of apoptosis and ROS production was visualized by AO and DHE staining, respectively. D. Quantification of the fluorescence from AO-stained and DHE-stained embryo images using Image J software (

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, accessed on 3 January 2023). The data are expressed as the mean±SD from five independent experiments. The statistical differences of multiple groups were compared using an independent

t-test. a. PBS-alone injected; b. CML + PBS injected; c. CML + rHDL-0 injected; d. CML + rHDL-BWA (1:0.5) injected; e. CML + rHDL-BWA (1:1) injected. *,

p < 0.05; ***,

p < 0.001 vs. CML + PBS; #,

p < 0.05; ##,

p < 0.01; ###,

p < 0.001 vs. CML + PBS.

Figure 8.

Comparison of survivability and embryo development among rHDLs containing BWA in the presence of carboxymethyllysine (CML, final 800 ng). A. Survivability of embryos during 24 hr post-injection of each rHDL and CML from three independent experiments. *,

p < 0.05; **,

p < 0.01; ***,

p < 0.05 vs. CML alone. Statistical differences of multiple groups were compared using an independent

t-test. B. Developmental morphology of the embryo at 5 hr and 24 hr post-injection. The red arrowheads indicate defects of development and death of embryos in the CML alone group (photo b) and CML + rHDL-0 (photo c). The blue arrowheads indicate the slowest developmental speed in eye pigmentation and tail elongation in the CML alone group (photo b) and CML + rHDL-0 group (photo c) at 24 h post-injection. C. Fluorescence image of acridine orange (AO, Ex = 505 nm, Em = 535 nm) stained and dihydroethidium (DHE, Ex=585 nm, Em=615 nm) stained embryo at 5 hr post-injection. The extent of apoptosis and ROS production was visualized by AO and DHE staining, respectively. D. Quantification of the fluorescence from AO-stained and DHE-stained embryo images using Image J software (

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, accessed on 3 January 2023). The data are expressed as the mean±SD from five independent experiments. The statistical differences of multiple groups were compared using an independent

t-test. a. PBS-alone injected; b. CML + PBS injected; c. CML + rHDL-0 injected; d. CML + rHDL-BWA (1:0.5) injected; e. CML + rHDL-BWA (1:1) injected. *,

p < 0.05; ***,

p < 0.001 vs. CML + PBS; #,

p < 0.05; ##,

p < 0.01; ###,

p < 0.001 vs. CML + PBS.

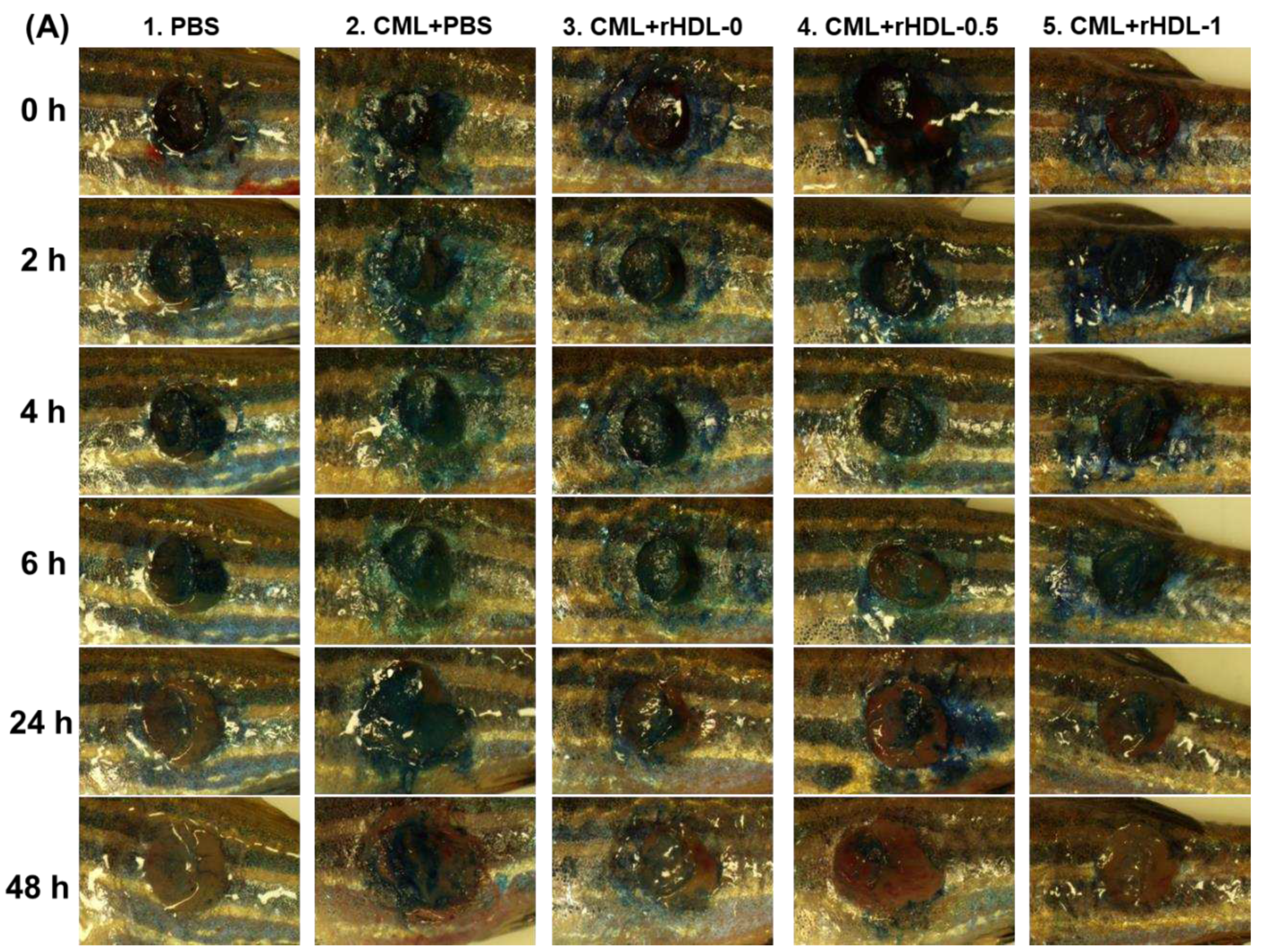

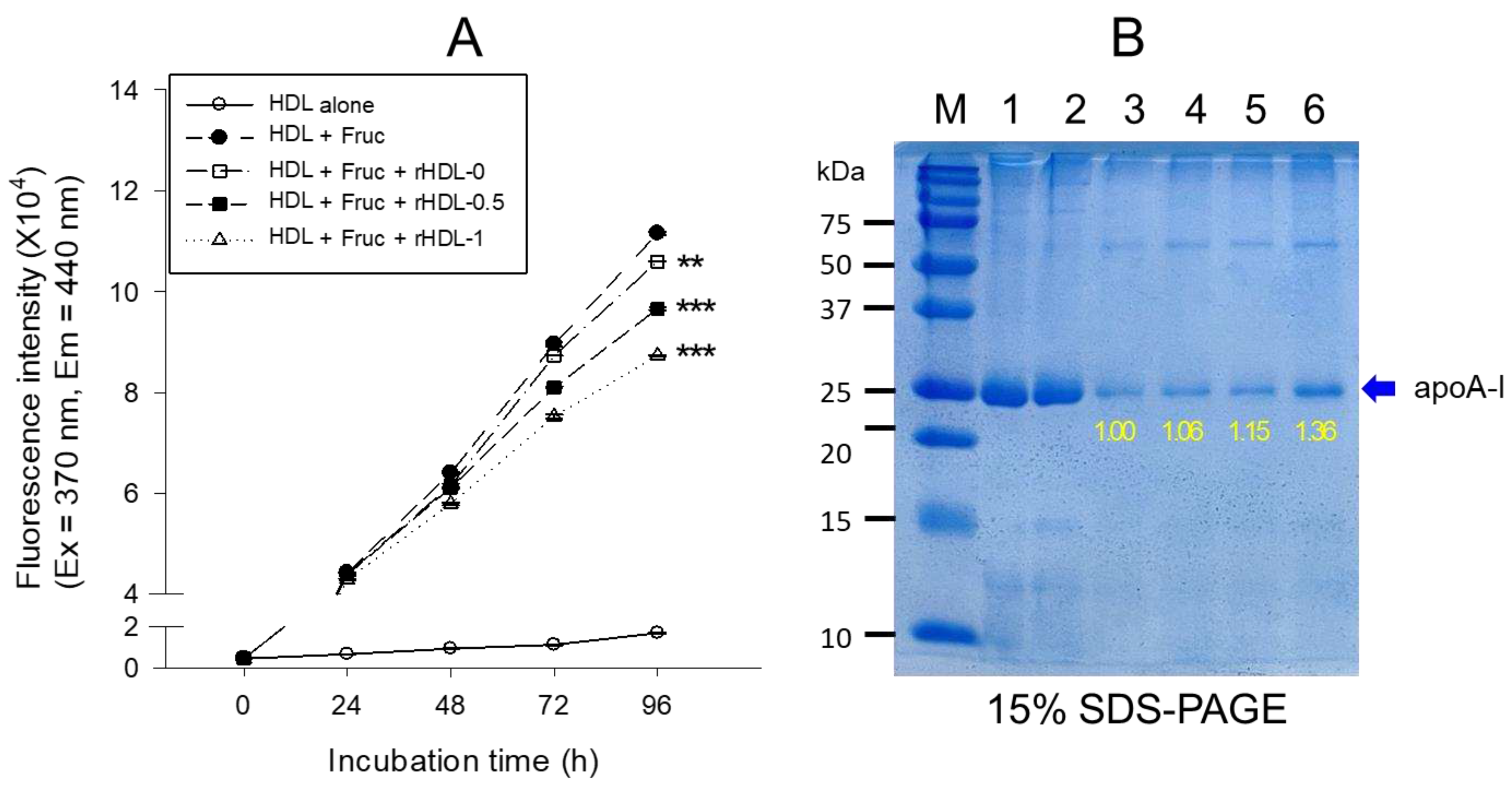

Figure 9.

A comparative wound healing effect of rHDL composed of different proportions of beeswax alcohol (BWA) against carboxymethyllysine (CML) impaired cutaneous wound in zebrafish.

(A) Pictorial view of the wounded area stained with methylene blue (0.1% (

w/v) final).

(B) A time-dependent wound healing up to 48 hours post-treatment. The wound healing was calculated by comparing the stained wound area measured at different time points against the wound stained area at 0 hr. P-value documented the pairwise statistical variance retrieved from the ANOVA using a Turkey test for Post Hoc analysis. (

C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H& E) staining of the wounded tissue at 48 hours post-treatment

. The black and red arrows indicate a compact and loosely packed muscular tissue, respectively.

(D) Dihydroethidium (DHE) and acridine orange (AO) staining of the wounded tissue at 48 hr post-treatment. The fluorescent intensity in DHE and AO staining was measured using Image J software (version 1.53,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/retrieved on 18 May 2023). The letters (a-d, A-D) above the bar charts indicate the significant statistical differences (p<0.05) among the groups.

Figure 9.

A comparative wound healing effect of rHDL composed of different proportions of beeswax alcohol (BWA) against carboxymethyllysine (CML) impaired cutaneous wound in zebrafish.

(A) Pictorial view of the wounded area stained with methylene blue (0.1% (

w/v) final).

(B) A time-dependent wound healing up to 48 hours post-treatment. The wound healing was calculated by comparing the stained wound area measured at different time points against the wound stained area at 0 hr. P-value documented the pairwise statistical variance retrieved from the ANOVA using a Turkey test for Post Hoc analysis. (

C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H& E) staining of the wounded tissue at 48 hours post-treatment

. The black and red arrows indicate a compact and loosely packed muscular tissue, respectively.

(D) Dihydroethidium (DHE) and acridine orange (AO) staining of the wounded tissue at 48 hr post-treatment. The fluorescent intensity in DHE and AO staining was measured using Image J software (version 1.53,

http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/retrieved on 18 May 2023). The letters (a-d, A-D) above the bar charts indicate the significant statistical differences (p<0.05) among the groups.

Table 1.

Characterization of rHDL containing different ratios of beeswax alcohol.

Table 1.

Characterization of rHDL containing different ratios of beeswax alcohol.

| Name |

MW of BWA1 (Averaged) |

Molar Ratio

POPC:FC:apoA-I:BWA |

WMF (nm) |

Diameter (nm) |

| rHDL-0 |

- |

95:5:1:0 |

330.9±0.1 |

61.2±1.6 |

| rHDL-0.5 |

429.1 |

95:5:1:0.5 |

331.0±0.0 |

65.4±2.3 |

| rHDL-1 |

95:5:1:1 |

331.4±0.1 |

70.5±2.3 |