1. Introduction

As a crucial environmental factor, temperature significantly impacts the embryonic development of aquatic organisms. Previous research has highlighted the high sensitivity of embryonic development and sexual maturity of aquatic organisms to temperature (Duan et al., 2020). Unlike fish, cephalopod embryos undergo a longer development process, typically lasting approximately 18-20 days for Sepiella japonica at a water temperature of 23-26 ℃. During this crucial period, temperature exerts a particularly influential role in embryonic development and incubation duration. Several studies on cephalopods have demonstrated an inverse relationship between the duration of embryonic development and temperature within a specific range (Jiang et al., 2020; Ramiro et al., 2020; Repolho et al., 2014). Furthermore, temperature also significantly impacts the mortality or survival rate of cephalopod embryos (Jiang et al., 2013; Ramiro et al., 2020). Presently, research on the relationship between embryo development and temperature in S. japonica primarily focuses on the impact of temperature on the developmental cycle and cumulative survival rate (Liu et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2010). However, there remains a lack of investigation into the occurrence of embryonic malformation resulting from abnormal temperatures and the molecular-level regulatory mechanism of relevant genes and pathways.

Autophagy, a crucial and evolutionarily conserved process in eukaryotes, serves as a response to various stress stimuli. In this process, damaged proteins or organelles are encapsulated within autophagic vesicles with a bilayer membrane structure and transported to lysosomes (in animals) or vesicles (in yeast and plants) for degradation and recycling. This process plays a pivotal role in maintaining cellular homeostasis (Glick et al., 2010; Mizushima et al., 2008; Wirawan et al., 2012). Under normal circumstances, autophagy is maintained at a certain baseline level, and it can be induced by various internal and external factors. Internal factors include broken senescent organelles and misfolded proteins, while external factors encompass nutrient deficiency, hypoxia, and temperature (Chao et al., 2017; Varshavsky et al., 2017). Although the impact of temperature on autophagy has been predominantly studied in cell lines and adult organisms (Chen et al., 2021; Kassis et al., 2020; McCormick et al., 2020), research in various plant and animal model organisms has indicated that high or low temperatures can activate autophagy to varying degrees (Dundar et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2016; Molina et al., 2023; Ruperez et al., 2022).

Autophagy and apoptosis often coexist in biological processes such as embryonic development, tumorigenesis, and organism aging (Das et al., 2021; Qu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2019). Apoptosis, known as type I programmed cell death, significantly influences organism development, cell renewal, and internal environment stability (Kanduc et al., 2002; Kaur et al., 2019). Studies in species including pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus), white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei), and disk abalone (Haliotis discus hannai) found that too high or too low temperatures can cause cell apoptosis, resulting in abnormal physiological activities of the organisms (Cheng et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2023; Li et al., 2014). Despite this, limited research exists on the exact relationship between autophagy/apoptosis and temperature during the embryo development process (Kassis et al., 2021; Mccormick et al., 2021; Shahabad et al., 2022).

Innexin (Inx) is a highly conserved gap junction protein found exclusively in invertebrates (Bauer et al., 2005; Beyer et al., 2018). It shares a similar membrane topology and quaternary structure with the vertebrate gap junction protein connexin (Cx). Gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) studies have demonstrated its crucial role in the apoptosis regulation (Akopian et al., 2014; Hiromi et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2001; Seul et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2001). Additionally, the involvement of connexin in autophagy has been observed in various studies. For instance, in mouse hepatocytes, Cx43 participates directly in the initial stage of autophagosome formation (Bejarano et al., 2014). In rats, the phosphorylation of Cx43 in astrocytes is positively correlated with autophagy intensity, and inhibiting this phosphorylation weakens autophagy occurrence (Sun et al., 2015).

Cephalopoda, a class of Mollusca comprising 901 known species (MolluscaBase, 2023), includes some cuttlefish, which are easily bred in artificial breeding (Domingues et al., 2006). Thus, they serve as suitable model species for studying the interaction of the changing environment on morphological and physiological aspects. However, the sensitivity of cephalopod embryos at different developmental stages to temperature has remained as mysterious as this group itself. S. japonica, commonly known as cuttlefish, holds important economic and medicinal value and is one of the “four major seafoods” in the East China Sea. It used to have a large yield, but now it is one of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Local scientists have invested a lot of effort in breaking through its artificial breeding technology and using it in resource rebuilding. Up to date, research on S. japonica has primarily focused on reproductive behavior, gonad development, and immune response (Liu et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022; Lv et al., 2019; Pang et al., 2019; Wada et al., 2018). Little is known about the specific effects of different temperatures on morphological characteristics, autophagy, and apoptosis during embryo development.

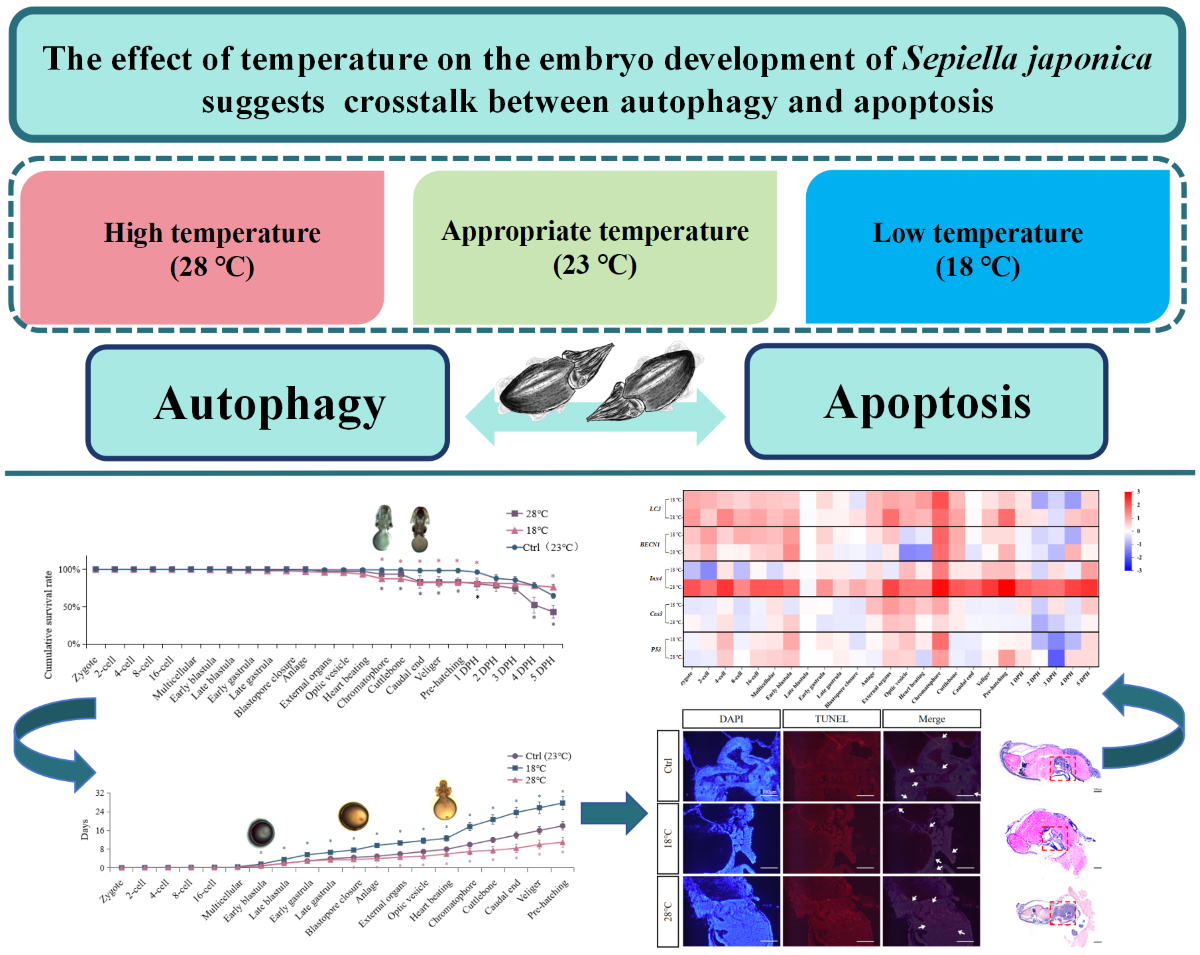

Building on the research background mentioned above, this study aims to establish a temperature gradient model (18 ℃, 23 ℃, and 28 ℃) to investigate the effect of high and low temperatures on survival rate, tissue structure changes, developmental duration, and expression characteristics of genes related to autophagy (LC3 / BECN1 / Inx4) and apoptosis (Cas3 / p53) in S. japonica embryos at different developmental stages. The objective is to gain initial insight into the interaction between autophagy and apoptosis during embryonic development under varying temperatures. The findings will lay a groundwork for understanding how environmental factors, like temperature, influence embryo development of this mysterious cephalopod. Additionally, this research will contribute to optimizing artificial nursery conditions, improving the survival rate of young adults, and offering valuable insights for the successful recovery of this precious species. The study holds significant scientific and industrial application value.

Results

2.1. Mortality rate and cumulative survival rate

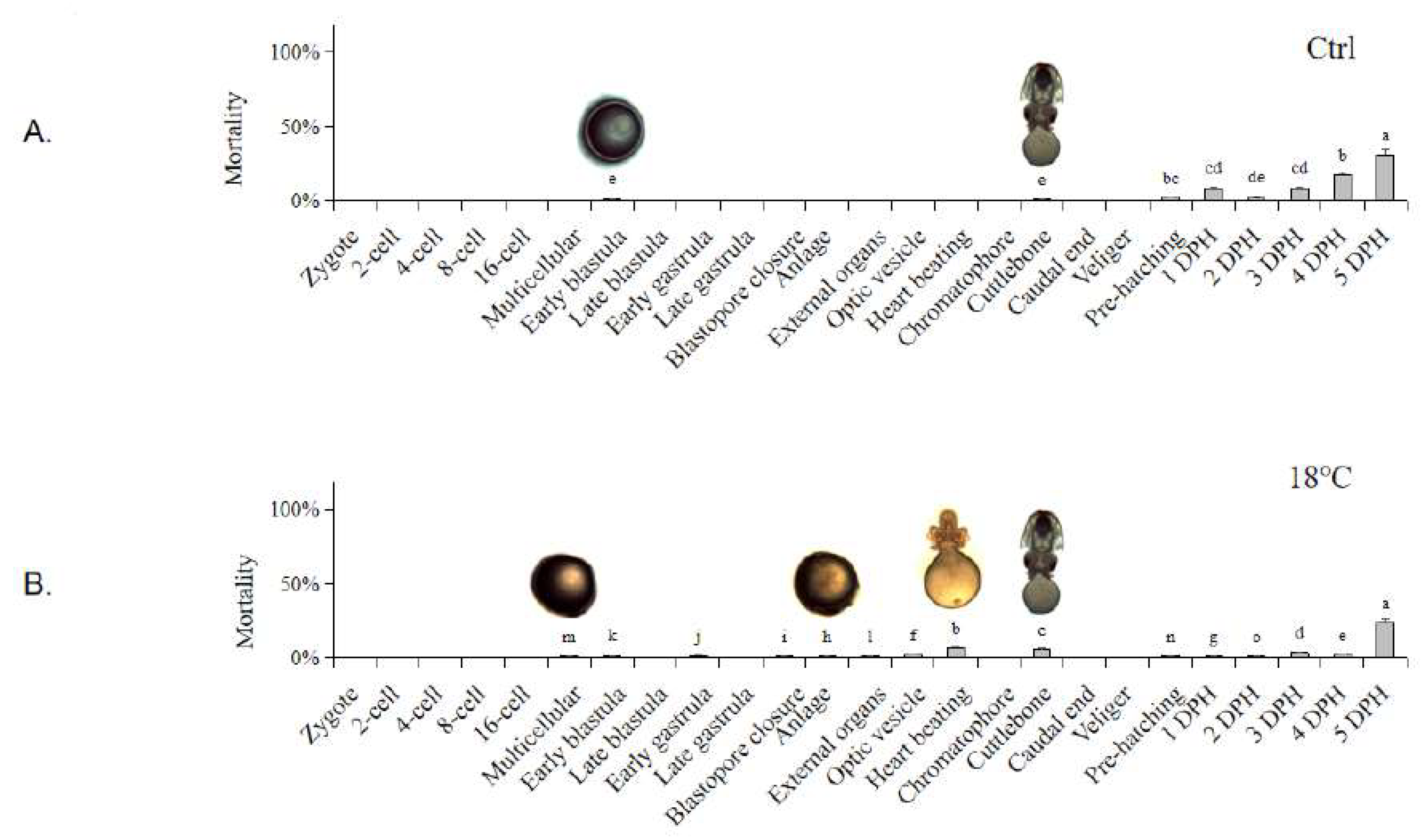

The mortality rate and cumulative survival curve at different embryonic development stages under different temperatures are shown in

Figure 1. In the Ctrl group, sporadic deaths of the embryos occurred at the Early blastula and Cuttlebone stages, with an overall mortality rate remaining below 4.5% before hatching (

Figure 1A). In the low-temperature group (18 ℃), significant mortality first occurred at the Multicellular stage, and then mainly occurred at the Anlage, Heart beating, and Cuttlebone stages. The mortality rate remained low until 4 DPH, with the highest death rate at 5 DPH (

Figure 1B). In the high-temperature group (28 ℃), significant mortality first occurred at the Anlage stage, then at the Heart beating and Cuttlebone stages, reaching its peak at 3 DPH, followed by a gradual decrease (

Figure 1C).

The cumulative survival rates (

Figure 1D) in the Ctrl group remained above 98.55 ± 2.96% before hatching and above 64.73 ± 3.24% until the end of the experiment (5 DPH). In the low-temperature group (18 ℃), the cumulative survival rate started to decline slightly at the Early blastula stage and decreased significantly at the Chromatophore and Caudal end stages before hatching. The cumulative survival rate remained above 82.42 ± 4.12% until hatching and dropped to 76.32 ± 3.82% at 5 DPH. In the high-temperature group (28 ℃), the cumulative survival rate began to decrease significantly at the Chromatophore stage and decreased again at the Caudal end stage. The cumulative survival rate decreased to 83.23 ± 4.99% before hatching. It decreased significantly at 4 DPH due to the mass death at 3 DPH, resulting in a cumulative survival rate of 42.90 ± 8.58% at the end of 5 DPH. Significant decreases in cumulative survival rate usually occurred at the stage following the high mortality period.

2.2. Effects of different temperatures on the embryonic development duration

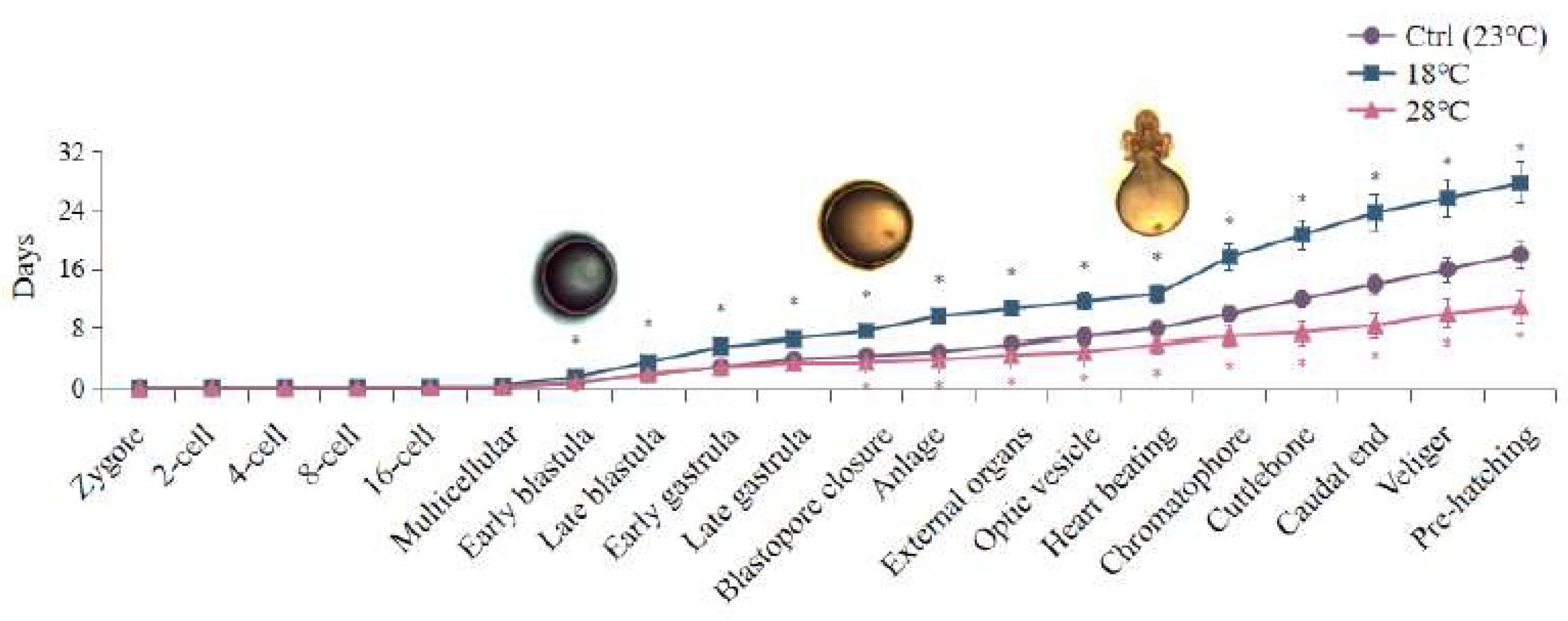

Different temperature treatments also caused changes in the duration of certain developmental stages (

Figure 2). Embryos exposed to low temperature (18 ℃) exhibited a delay starting at the 4-cell stage, with an average delay of 0.5 days in all subsequent periods. This resulted in a total developmental length delay of approximately 9 days compared to the Ctrl group. The delay was more significant at the Early blastula and Heart beating stages (

p < 0.05). Conversely, embryos cultured at high temperature (28 ℃) showed developmental advancement at the 4-cell stage. Each subsequent developmental period occurred, on average, 0.39 days earlier than the Ctrl group, resulting in a total advancement of 7 days in the overall embryonic development duration. The most notable advancement was observed at the Blastopore closure stage. The largest differences between the high and low temperature groups were observed at the Chromatophore stage, followed by the Cuttlebone, Caudal end, and Anlage stages.

2.3. Embryonic malformation caused by low and high temperatures

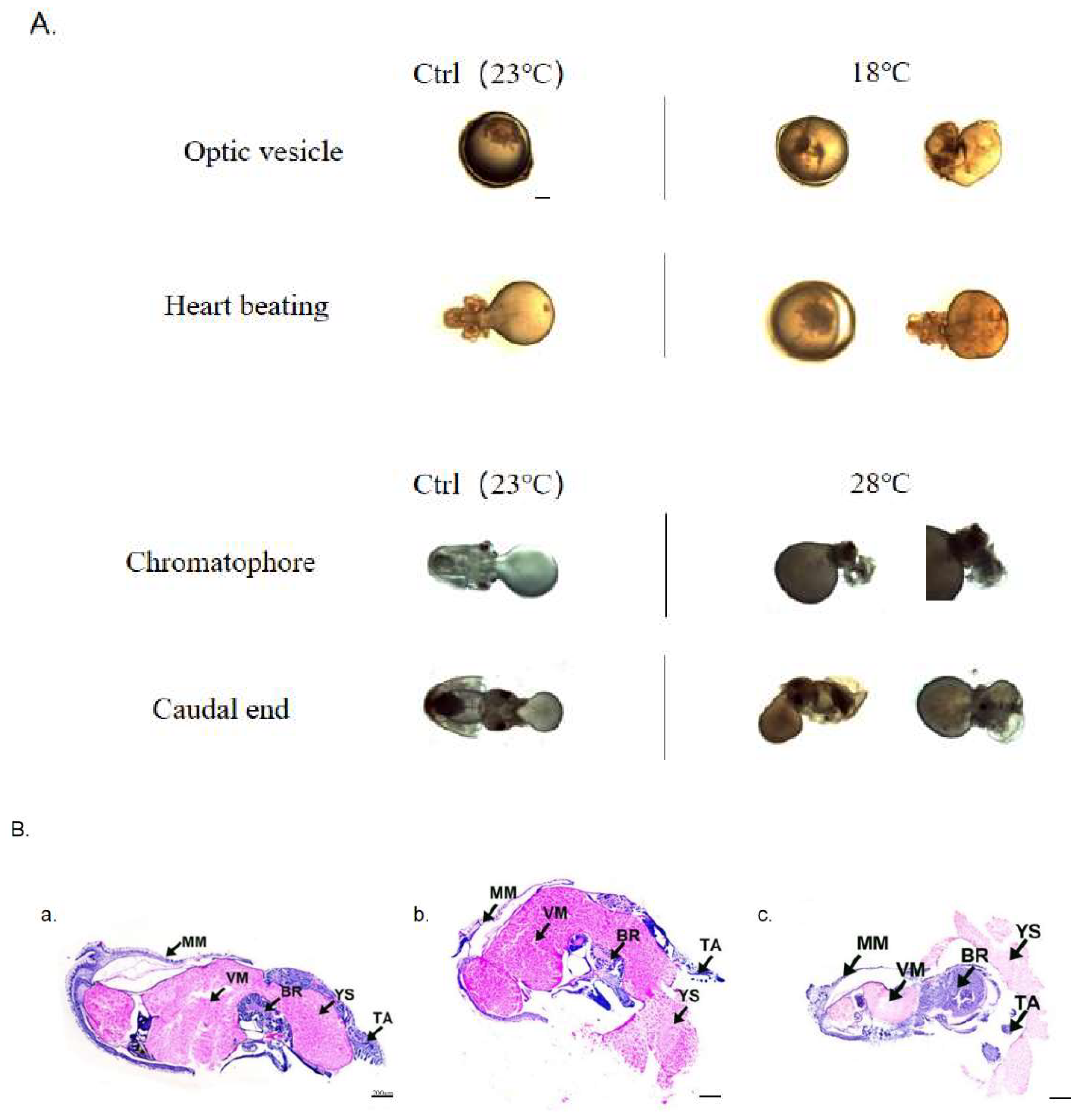

To investigate the impact of low and high temperatures on embryo morphology, we compared their morphological and histological changes according at the most sensitive stages, as depicted in

Figure 3. In the Ctrl group, no embryonic malformations were observed. However, in the low-temperature group (18 ℃), the rate of embryonic malformation was 12.97 ± 0.73%. Specifically, shortened arms and disordered external organ development were observed at the Optic vesicle stage and Heart beating stage, respectively. On the other hand, the high-temperature group (28 ℃) exhibited an even higher embryonic malformation rate of 20.04 ± 0.57%. At the Chromatophore and Caudal end stages, swelling of the visceral mass, exposed gills, and ectropion mantle were observed.

Further analysis of the histological changes at the Caudal end stage revealed significant malformations (

Figure 3B). Compared to the Ctrl group, embryos in the 18 ℃ group exhibited abnormal curvature resembling a “V” shape, along with swelling of the visceral mass and a tendency towards ectropion mantle. Additionally, in the high-temperature group (28 ℃), the morphology of the mantle was also distinctly different from that of the Ctrl group.

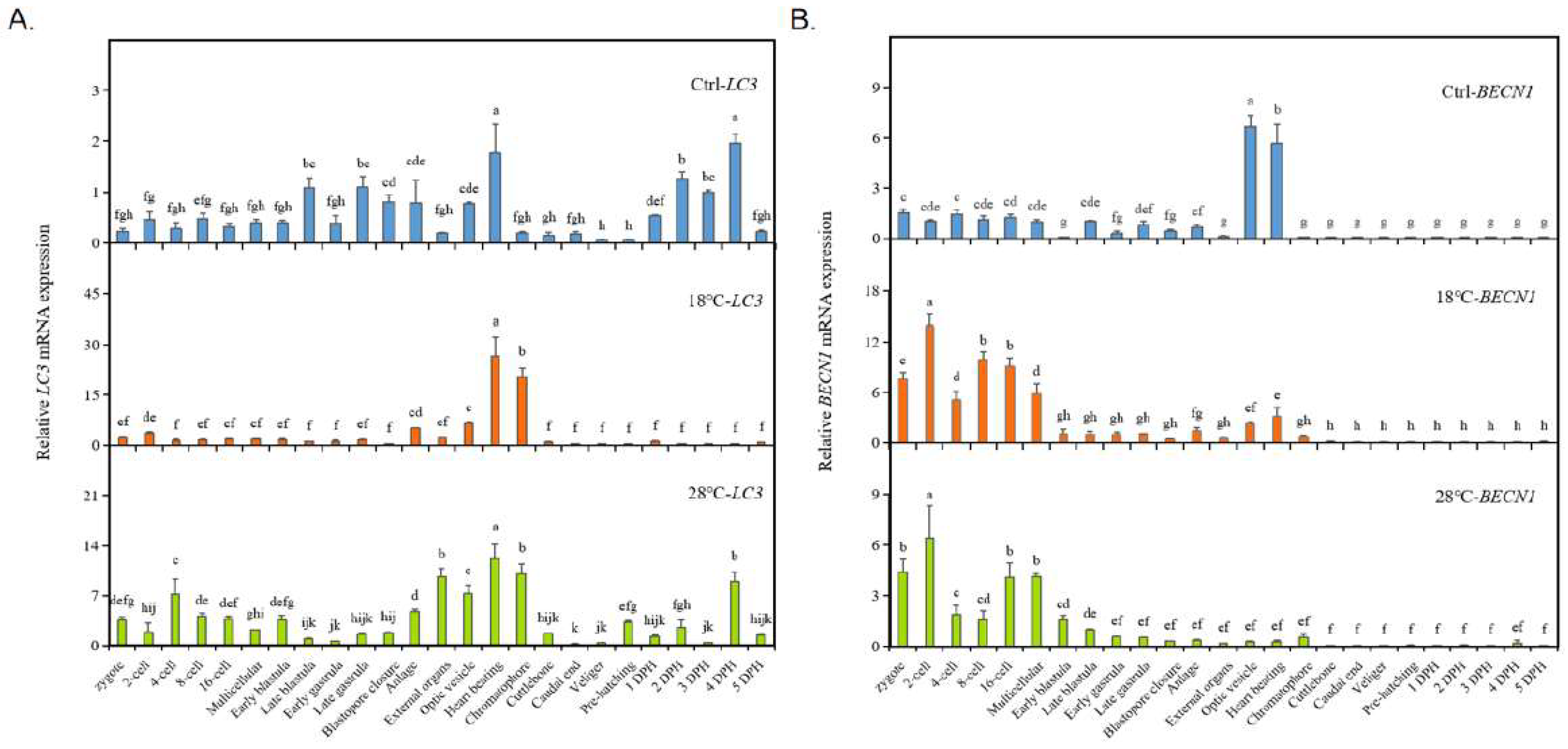

2.4. Expression of autophagy marker genes LC3 / BECN1 of the embryos

To investigate the impact of low and high temperatures on autophagy levels in embryos, we conducted a systematic study using the common autophagy marker genes

LC3 and

BECN1. The results are presented in

Figure 4. In the Ctrl group, the expression of

LC3 fluctuated, with high levels observed at the Late blastula, Late gastrula, and Heart beating stages, and the highest expression was observed at the Heart beating stage and 4 DPH. The expression patterns of

LC3 in the low temperature (18 ℃) and high temperature (28 ℃) groups were similar to the those in Ctrl group before hatching, with fluctuating expressions and a peak at the Heart beating stage. In the 18 ℃ group, the second highest expression was observed at the Chromatophore stage. Furthermore, the expressions of

LC3 at these two stages (Heart beating and Chromatophore) were significantly higher than those in the Ctrl group. In the high-temperature group (28 ℃), the overall expression level of

LC3 was also much higher than in the Ctrl group. However, the expression pattern in the 28 ℃ group was more similar to that of the Ctrl group (early fluctuations, high expression at the Heart beating stage and 4 DPH), and the two periods of highest expression (before hatching) were consistent with the 18 ℃ group (highest expressions observed at the Heart beating and Chromatophore stages). Additionally, a significant increase in

LC3 expression at the Chromatophore stage was observed in both temperature treatment groups.

However, both low and high temperature treatments significantly altered the expression pattern of

BECN1 (

Figure 4B). In the Ctrl group,

BECN1 remained at a low level until reaching the Optic vesicle stage (highest expression) and Heart beating stage (second-highest expression). However, both low and high temperatures caused a significant increase in

BECN1 expression during the early developmental stages, from the Zygote to the Multicellular stage, with similar “M”-shaped curves. In both the 18 ℃ and 28 ℃ groups, the highest expression occurred at the 2-cell stage, followed by a significant decrease at the 4-cell stage. After another increase around the 8-cell to 16-cell stages,

BECN1 expression decreased again at the Early blastula stage. From then on, it maintained a lower expression level until the end of the experiment. Compared to the Ctrl group, temperature treatments resulted in increased

BECN1 expression during the early stages and a significant decrease at the Optic vesicle and Heart beating stages.

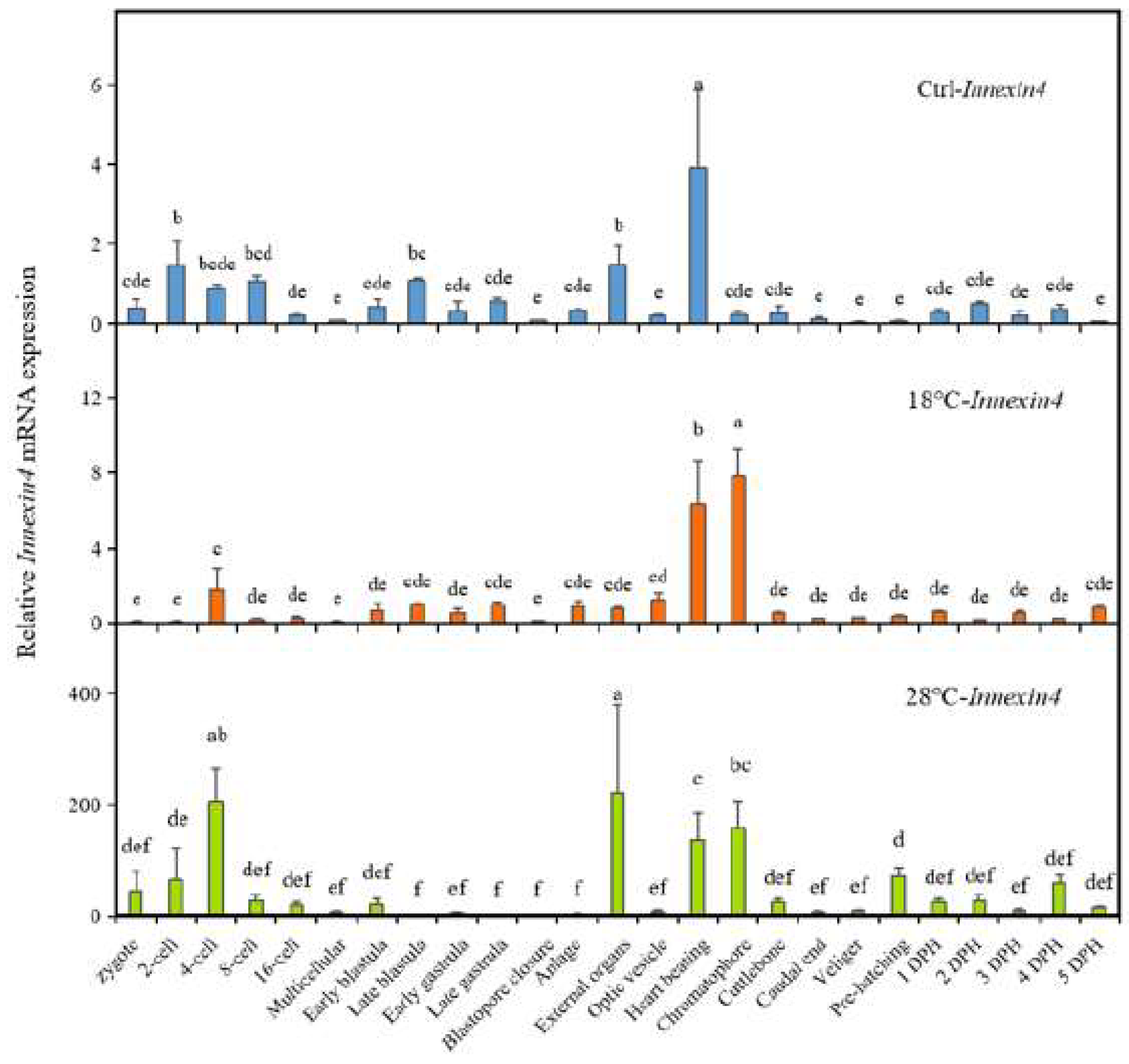

2.5. Expression of autophagy-related gene Inx4 of the embryos

We also examined the expression changes of the potential autophagy-related gene

Inx4 under different temperatures, as shown in

Figure 5. In the Ctrl group,

Inx4 reached its peak at the Heart beating stage, with relatively low expression levels during other periods. However, both low and high temperature treatments significantly increased the expression of

Inx4, especially at the Heart beating stage in the high-temperature group (28 ℃), which was approximately 45 times higher than in the Ctrl group. Additionally, there were other stages at which

Inx4 expression significantly increased, including the Chromatophore stage in the 18°C group, and the 4-cell, External organs, and Chromatophore stages in the 28°C group. The periods of high

Inx4 expression were directly influenced by the temperature treatment, with high temperature having a significant induction effect on

Inx4 expression.

2.6. Expression of apoptosis marker genes Cas3 / p53 of the embryos

To further investigate the effect of temperature on embryo apoptosis, we analyzed the expressions of the apoptosis-related genes

Cas3 and

p53 in the control (23 ℃), low temperature (18 ℃), and high temperature (28 ℃) groups. As shown in

Figure 6A, higher expressions of

Cas3 were mainly observed from the blastula to the Chromatophore stages. In the Ctrl group,

Cas3 expression first increased and then decreased, with the highest expression at the Late gastrula stage. In the 18 ℃ group,

Cas3 expression showed similar trends, with the highest expression point shifting to the Anlage stage, and this relatively high level of

Cas3 expression was consistently maintained until the Chromatophore stage. In the 28 ℃ group, the highest

Cas3 expression was observed at the Optic vesicle stage.

The results for

p53 in all groups, especially the temperature treatment groups, showed a similar trend of variation (

Figure 6B). In the control group,

p53 expression was higher at the Zygote, Late blastula, and Anlage stages. In both the low-temperature (18 ℃) and high-temperature (28 ℃) groups,

p53 expression was higher at the 4-cell stage, blastula, and Anlage stages.

2.7. Heat map of the gene expression elevated folds

To visualize the overall changes in gene expression under different temperatures, we analyzed the fold changes in expression of all autophagy and apoptosis-related genes. As shown in

Figure 7, the periods of increased

LC3 expression in the low and high temperature groups mainly occurred from the Zygote to the Early blastula stage and from the Anlage to the Cuttlebone stage. The expression patterns of

BECN1 in the low and high temperature groups were also similar. In contrast to the low-temperature group, the expression of

Inx4 in the high-temperature group showed significant differences compared to the Ctrl group at almost every stage. Additionally, the expression patterns of the apoptosis marker genes (

Cas3/

p53) in the embryos of the low-temperature group and high-temperature group were similar, with no significant differences in other periods except for a few stages. Furthermore, compared to the Ctrl group, the expressions of autophagy-related genes (

LC3/

BECN1/

Inx4) and apoptosis marker genes (

Cas3/

p53) all increased to varying degrees at the Chromatophore stage, regardless of whether it was the low or high temperature group. It is worth noting that the increased expression of

Inx4 in the 28 ℃ group was significantly higher than in the 18 ℃ group.

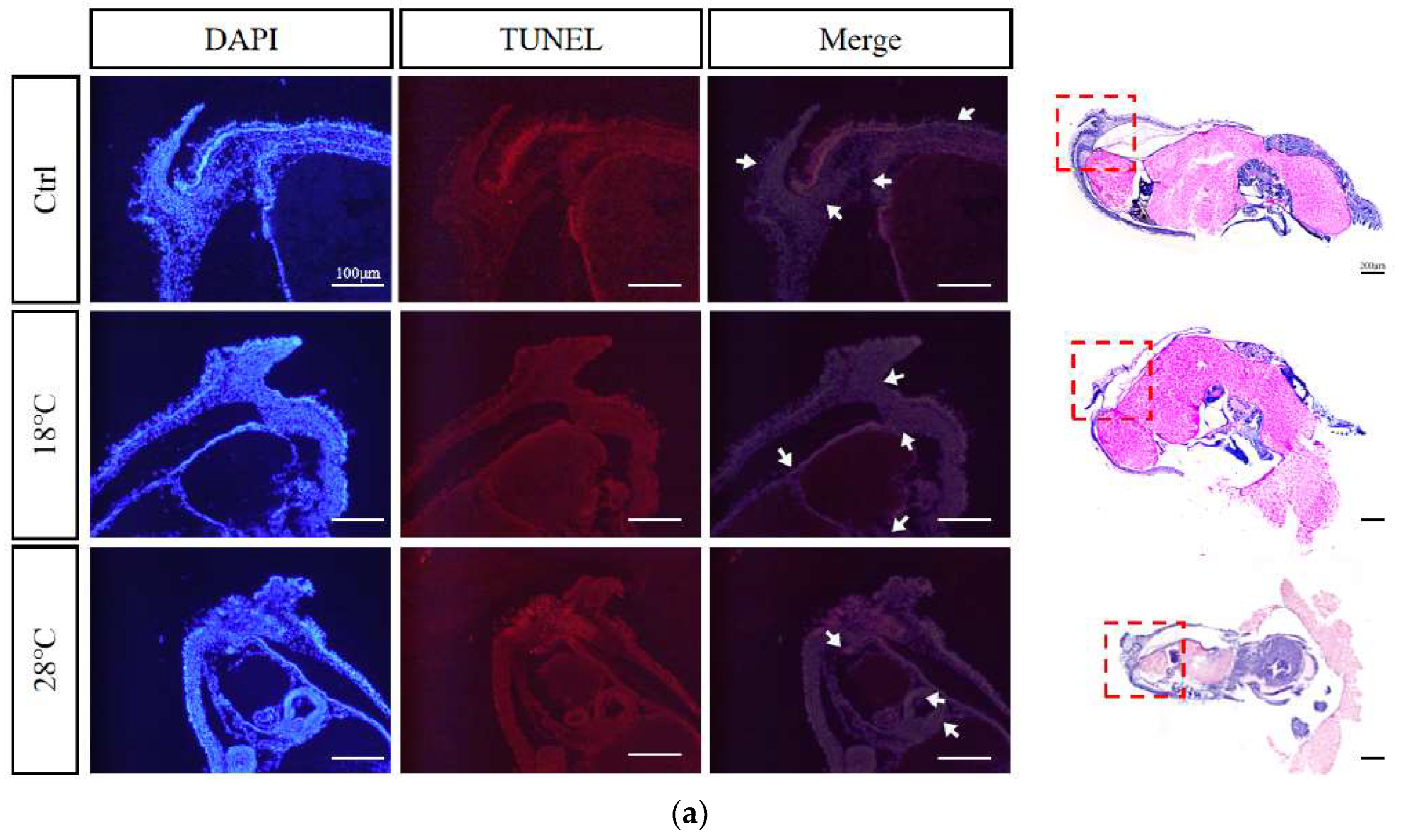

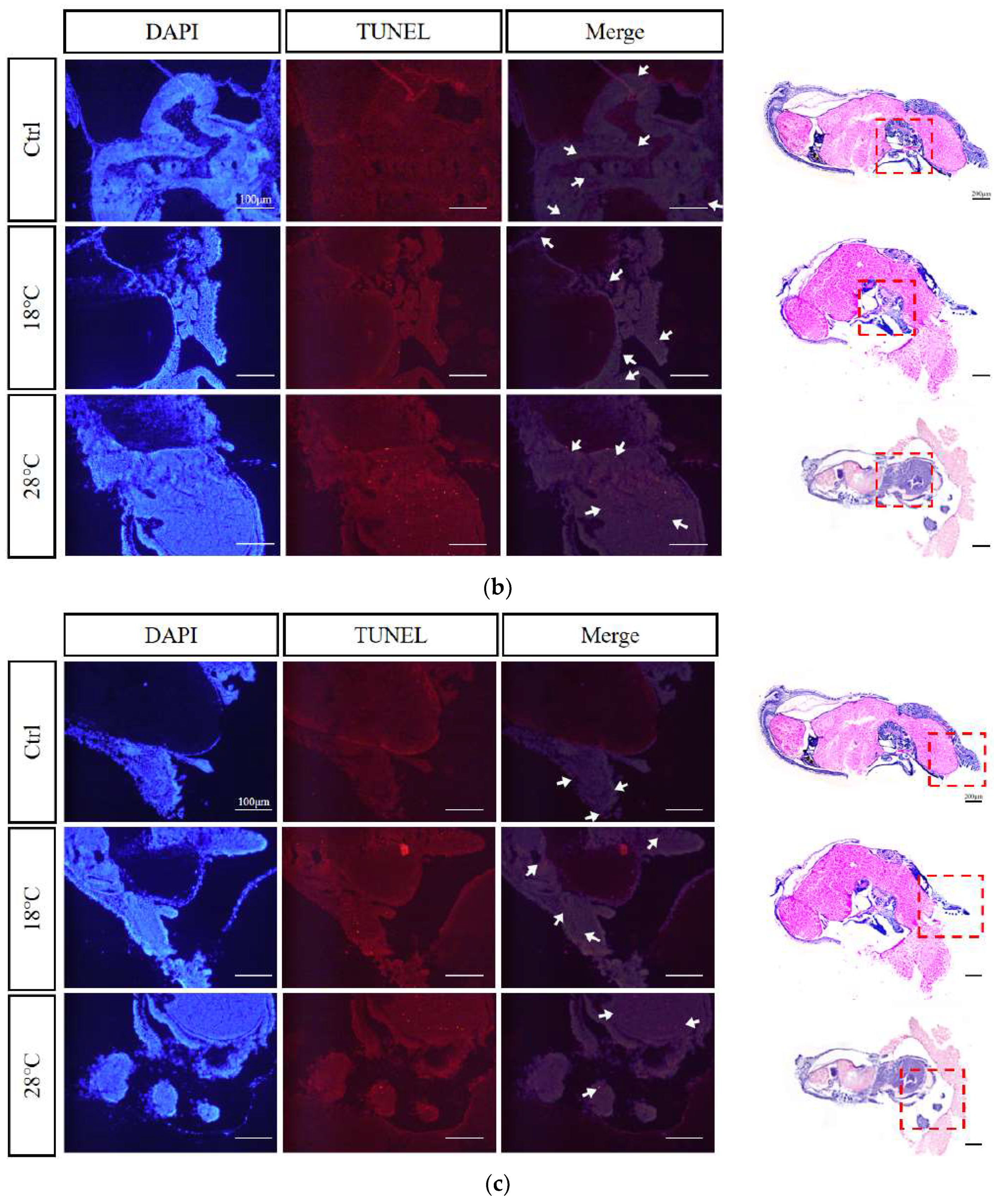

2.8. Apoptotic staining (TUNEL) of embryos at sensitive stages

Based on the previous findings, we selected embryos at the Caudal end stage, known for typical periods of embryonic malformations periods, from the control and temperature treatment groups. Using TUNEL staining, we further investigated the apoptosis levels of the embryos. The enlarged images were subsequently divided into three sections for presentation purposes: body, head, and arms (

Figure 8A-C). DAPI staining visualize nuclei (blue), TUNEL staining indicated apoptosis (red), and strong apoptosis signals were marked by white arrows.

Compared to the Ctrl group, the low-temperature group (18 ℃) showed concentrated apoptotic signals mainly in the arms, while the high-temperature group (28 ℃) exhibited signals mainly in the head and arms. Overall, the 28 ℃ group displayed more and stronger signals than the 18 ℃ group, highlighting the temperature-dependent impact on apoptosis during embryonic development.

3. Discussion

Among the environmental factors influenced by global change, temperature is, by far, the most documented as concerns effects on developmental plasticity (Vagner et al., 2019). Understanding favorable or optimal environmental conditions is crucial for the artificial propagation of any species (Soman et al., 2021). Water temperature is a key abiotic factor for the survival of aquatic organisms and plays a critical role in successful hatchery production (Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, changing oceanic water temperatures during early life stages is crucial for species recruitment and survival (Go et al., 2020). Previous studies showed that high temperatures lead to higher mortality rates than low temperatures in the Asian yellow pond turtle (Mauremys mutica) (Zhu et al., 2006), tehuelche octopus (Octopus tehuelchus) (Braga et al., 2021), and zebrafish (Dahlke et al., 2020). In the present study, compared to the Ctrl group, temperature treatments resulted in increased embryonic mortality, especially in the high-temperature group. We speculate that this is due to the slower metabolism and weaker stress response of embryos in the low-temperature group (Guiet et al., 2016), resulting in a higher survival rate compared to the high-temperature group. Many embryonic and adult studies have found that the cellular damage caused by high temperatures is much greater than that caused by low temperatures, which is usually irreversible (Gao et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Obrador et al., 2023).

It is worth mentioning that in both the low and high-temperature groups, periods of higher embryonic mortality mainly occurred during Heart beating and Cuttlebone stages. This suggests that these two periods are likely to be temperature-sensitive. However, in the temperature treatment groups, the embryonic development periods in which the cumulative survival rate significantly decreased occurred at the Chromatophore and Caudal end stages, slightly lagging behind the periods of high instantaneous mortality. Typically, significant decreases in cumulative survival rate occur in the stage following the high mortality period. Therefore, the lag phenomenon is caused by the accumulation of death.

The plasticity in hatching time of cephalopods can provide an advantage for their survival under heterogeneous environmental conditions (Boletzky, 2003). Hatching can be delayed if the embryonic developmental temperature is close to the lower temperature limit to which the species is adapted (Boletzky, 1987; Boletzky, 1994). In contrast, within a certain temperature range, an increase in temperature would shorten the duration of embryonic development (Radonic et al., 2005). For model animals, such as zebrafish: higher temperatures above 28.5 °C have been shown to accelerate zebrafish embryonic development (Pype et al., 2015). In addition, in arthropods, low temperatures can induce Artemia sinica to enter the diapause stage during embryonic development (Zhang et al., 2018). For mollusca, higher water temperature increased the metabolism of the embryos and consequently accelerating development (Paredes-Molina et al., 2023). Especially in cephalopods, according to Uriarte (2012) and Nande (2018), a shorter embryonic development and hatching period due to an increase in temperature would allow octopuses to hatch earlier, grow faster, and reach reproductive age. Embryos of Amphioctopus fangsiao hatched successfully at 40, 30, and 24 days post-fertilization (dpf) at temperatures of 18 °C, 21 °C, and 24 °C, respectively (Jiang et al., 2020). Similar results were observed in this study: compared to the Ctrl group, the overall development time of embryos in the low-temperature group was delayed by approximately 9 days, with significant delays occurring at the Early blastula and Heart beating stages. Our results indicate that the overall development time of embryos in the high-temperature group was shortened by 7 days compared to the Ctrl group. This inverse relationship between temperature and incubation period is consistent with other species. Additionally, the first significant advancement in embryonic development of S. japonica occurred at the stage of Blastopore closure in the high-temperature group, while the first significant delay occurred at the stage of Early blastula in the low-temperature group. However, the most notable differences in the duration of embryonic development between the high and low temperature groups were observed specifically at the Chromatophore stage. Therefore, these stages including Blastopore closure, Early blastula, and Chromatophore, may be abnormally sensitive to temperature in the embryonic development of S. japonica.

Abnormal temperatures not only impact the cumulative survival rate of embryos but also lead to the occurrence of malformations. It has been extensively documented in fishes that the temperature during egg incubation, as well as the larval and juvenile periods, is a critical environmental factor that influences malformation rates (Aritaki et al., 2004; Tsuji et al., 2013). Incubating zebrafish embryos at temperatures of 32.5°C and above from 2.5 until 96 hours post-fertilization caused malformations occurring as early as 24 hours post-fertilization (Pype et al., 2015). However, for mollusca, too high or too low incubation temperature would cause a certain increase in the possibility of embryonic development malformation. Lower rates of deformities were observed during the embryonic stages of C. seguenzae at 23 °C, whereas development at 17 °C and 29 °C led to high rates of deformities or total mortality (Doxa et al., 2021). In Coelomactra antiquata, fertilized eggs developed to the larval stage after 20 hours at a water temperature of 15.5 ± 0.5 °C but ceased to develop, while at a temperature of 28 ± 0.5 °C, the fertilized eggs became deformed (Liu and Chen, 1998). Similarly, in A. fangsiao, where 25.9% of eggs incubated at a lower temperature (24 °C) failed to undergo inversion from the animal pole to the vegetal pole (Jiang et al., 2020). In the present study, malformations caused by low temperature (18 °C) primarily occurred during the stages of Optic vesicle and Heart beating, resulting in shortened arms and disordered external organ development. Conversely, malformations caused by high temperature (28 °C) mainly occurred during the stages of Chromatophore and Caudal end, characterized by swelling of the visceral mass, exposed gills, and ectropion mantle. Comparing the malformation characteristics between the two, it was observed that S. japonica embryos were more intolerant to high temperature (28 °C). Our experimental results demonstrate that both high temperature (28 °C) and low temperature (18 °C) incubation conditions induce malformations in S. japonica embryos, with high temperature displaying a more severe effect than low temperature.

Autophagy has been shown to be a survival mechanism under different stress conditions (Jing et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2015). Furthermore, autophagy is an important response mechanism to temperature changes (Chen et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019). Current studies on the effect of temperature on the level of autophagy mainly focus on model organisms. In a study on the effects of high temperature on the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana, it was found that autophagy plays a crucial role in reducing the effects of high temperature on the growth of A. thaliana and maintaining specific pollen development (Dündar et al., 2019). Autophagy is also a major mechanism underlying heart remodeling in response to cold exposure and its subsequent reversion after deacclimation in mice (Ruperez et al., 2022).

In the present study, we found that the expression changes of LC3 after high/low temperature treatment tended to be generally consistent. The peak expression occurred during Heart beating and Chromatophore stages, indicating a high level of autophagy, which corresponded to the large number of malformations and high mortality observed at these two stages. The expression of BECN1 showed a similar pattern of change after high/low temperature treatment, with a significant increase at the stages of 2-cell and 8-16-cell and a significant decrease at the stages of Optic vesicle and Heart beating, corresponding to the large number of malformations during these stages. This suggests the important role of BECN1 in embryonic development. Similar results have been reported in mouse embryos (Qu et al., 2007), where mice lacking BECN1 died at an early embryonic stage, and embryos with low expression did not survive beyond 8.5 days (Yue et al., 2002; Yue et al., 2003). Based on the changes in the expression of LC3/BECN1, prolonged high/low temperature stress significantly inhibited autophagic activity in embryos, resulting in massive embryonic malformation and death at sensitive stages, especially during Heart beating and Chromatophore stages.

In the Ctrl group, the expression of Inx4 was highest at Heart beating stage. After high/low temperature treatment, Inx4 remained at a high level at the stage of Heart beating and significantly increased during Chromatophore stage. This corresponded to the significant number of embryonic malformations and high mortality observed around the stages of Heart beating and Cuttlebone. Notably, we found that after high/low temperature treatment, there was a strong correlation between a significant increase in the expression of Inx4 and high mortality. Innexin, as a unique gap junction protein gene in invertebrates, plays an irreplaceable role in embryonic development (Hong et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2019), immune response (Pang et al., 2015), and apoptosis (Liu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). Therefore, we speculate that the high expression of Inx4 during sensitive stages is associated with embryonic malformations and high mortality, and may also be related to the apoptotic pathway. However, the direct regulatory relationship still needs to be elucidated through systematic validation.

There is a complex interactive regulatory relationship between apoptosis and autophagy, (Yuan et al., 2013). The interaction between the two can achieve a dynamic balance to certain extent, which maintains the basic physiological functions of cells and reduces the damage to the body under stress (Xi et al., 2022). Previous studies have reported that high temperature challenge could increase endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the aquatic organisms (Li et al., 2014; Madeira et al., 2013), When the production of ROS is beyond the organism's capacity to deal with these reactive species, there is oxidative stress (Vinagre et al., 2012). Both autophagy and apoptosis are vital for optimal cellular functioning during encounters with internal or external stressors including uncontrolled cell growth, high levels of oxidative stress, and dysfunctional organelles (Wear et al., 2023). Autophagy typically prevents the induction of apoptosis, while caspase activation associated with apoptosis inhibits the autophagy process (Maejima et al., 2013; Pattingre et al., 2005). In Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), the combination of apoptosis and autophagy modulate follicular atresia under heat stress (Qiang et al., 2022). Research on the tunicate (Ciona intestinalis) has highlighted the significant role of autophagy during the late phases of development in lecithotrophic organisms and has also helped identify the coexistence of autophagy and apoptosis in cells (Baghdiguian et al., 2007). Similar results have been reported in mollusks, where cold and heat stress increased the activity of Cas8 in the gill tissues and blood cells of Mytilus coruscus and Mytilus galloprovincialis, leading to the activation of the apoptotic pathway (Zhang et al., 2014). In this study, the expression of Cas3 was higher from Blastula to Chromatophore stages in the Ctrl and high/low temperature groups. Compared to the Ctrl group, the expression of Cas3 significantly increased in the low-temperature (18 ℃) group from Anlage to Chromatophore stages, and in the high-temperature (28 ℃) group at the Optic vesicle stage. Similarly, the expressions of LC3 in the corresponding temperature treatment groups significantly increased compared to the Ctrl group. These findings indicate that the apoptotic pathway was significantly activated and the autophagic pathway was inhibited, corresponding to the increased mortality during the same periods.

Previous research found that high-temperature exposure up-regulated the activities of p53, Bax, caspase 9, and caspase 3 in pufferfish (T. obscurus), and the p53-Bax pathway and the caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway were involved in high temperature stress-induced apoptosis in pufferfish blood cells (Cheng et al., 2015). Similar results have been reported in a study of the effects of hyperthermia on human placental tissue cells, where 40 ℃ and 42 ℃ caused a significant increase in the expressions of p53 and Cas3 and in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, leading to the activation of the apoptotic pathway (Antonio et al., 2016). Loss of the apoptotic factor Bruce in mouse fibroblast cells also caused a significant elevation in the expression of p53 and activated Pidd/cas2 and Bax/Bak, which induced the activation of Cas3 and resulted in embryonic death (Ren et al., 2005). In this study, the expression trends of p53 in the control (23 ℃), low (18 ℃), and high (28 ℃) temperature groups were overall similar. However, compared to the Ctrl group, significantly higher expression mainly occurred at the 4-cell, Early blastula, and Chromatophore stages in the high and low temperature groups. It is speculated that low and high temperatures activate the expression of p53, which in turn activates the proapoptotic genes Bax/Bak and triggers apoptosis. Therefore, it is speculated that either too high or too low incubation temperature would cause abnormal activation of apoptosis-related signaling pathways, such as the BECN1-Bcl2 pathway and the p53 signaling pathway, which in turn would activate the proapoptotic genes Bax/Bak and induce the activation of Cas3, triggering apoptosis. However, further verification is needed to understand the specific regulatory mechanism of this pathway.

In this study, TUNEL apoptosis staining results also showed that the apoptotic signal was stronger in the high temperature group (28 ℃) than in the low temperature group (18 ℃), indicating that S. japonica embryos were more sensitive and intolerant to excessive temperatures. Comprehensive analysis reveals that the phenomenon of abnormal elevation of gene expression, embryonic malformation, and death caused by high temperature is more severe than that caused by low temperature, suggesting that during embryo culture, high temperature should be treated more cautiously.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Embryo culture and sampling

S. japonica embryos were obtained from the cuttlefish breeding center of Xixuan Island, Zhejiang Marine Fisheries Research Institute, and cultured in the laboratory of the National Marine Facilities Aquaculture Engineering Technology Research Center. Temporary culture conditions were as follows: tank size of 40 cm * 22 cm * 28 cm, salinity of 27, pH ranging from 6.8 to 7.2, continuous aeration, and 50% seawater renewal per day to maintain a dissolved oxygen concentration of more than 5 mg/L. Fresh seawater was pre-heated or pre-cooled to maintain stable temperatures in the different treatment groups: control group (Ctrl) at 23 ℃, low-temperature group at 18 ℃, and high-temperature group at 28 ℃. Each group had three parallel replicates, with each replicate including 300 fertilized eggs.

The hatching of fertilized eggs was regularly observed and recorded based on the developmental stages of the embryos. Referring to the embryonic stages as Naef (1928) and Jiang (2020), a total of 25 specific sampling periods were established, including Zygote, 2-cell, 4-cell, 8-cell, 16-cell, Multicellular, Early blastula, Late blastula, Early gastrula, Late gastrula, Blastopore closure, Anlage, External organs, Optic vesicle, Heart beating, Chromatophore, Cuttlebone, Caudal end, Veliger, Pre-hatching, 1 DPH (1 day post-hatching), 2 DPH (2 day post-hatching), 3 DPH (3 day post-hatching), 4 DPH (4 day post-hatching), and 5 DPH (5 day post-hatching). The number of dead and malformed embryos, as well as the duration of each developmental stage, were recorded. At each stage, 12 embryos were randomly sampled from each replicate group. The embryos were stored at -80°C for RNA analysis and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Solarbio, Shanghai, China) for histological study.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the protocols and guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Ocean University and the Academy of Experimental Animal Center of Zhejiang Ocean University.

4.2. Embryonic development observation and histological sections

Developmental features were observed under a stereoscopic microscope (Leica S9i, Wetzlar, Germany). Before taking pictures, the outer two layers of egg membranes were gently peeled off, leaving three layers of egg membranes. Embryos without outer membranes were fixed in 4% PFA for 24 hours, transferred to 50% Formamide deionized, and then storage at -20°C.

For hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, the samples were frozen and sectioned using a frozen microtome (Leica CM3050s, Wetzlar, Germany), and stored at -20°C. The frozen sections were refixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes, rinsed twice with distilled water for 2 minutes each. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining solution (Phygene, Fujian, China): hematoxylin was applied for 5 minutes, rinsed with tap water until the samples turned blue; the sections were then placed in 1% HCl solution for 5 seconds, rinsed with tap water again, followed by immersion in distilled water for 2 minutes, 50% ethanol for 2 minutes, 70% ethanol for 2 minutes, 80% ethanol for 2 minutes, eosin staining solution for 2 minutes, 95% ethanol for 2 minutes, 100% ethanol for 2 minutes, 50% xylene and 50% ethanol mixture for 2 minutes, and finally xylene for 5 minutes, twice. The sections were sealed with neutral resin and photographed under a microscope (Nikon NI-U, Tokyo, Japan).

4.3. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA from tissues was isolated using Trizol reagent (Takara, Kyodo, Japan) following the methods described in previous studies (Zhao et al., 2023). The quality, purity, and integrity of the RNAs were assessed using UV spectroscopy (A260/A280) on Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The mRNA was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara, Kyodo, Japan). The first-strand cDNA was used as the template.

4.4. Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR assay

Fluorescence quantification was performed using the SYBR Green dye method, and the internal reference genes β-actin and GAPDH were selected to minimize bias at each stage. Gene-specific primers (Table 1) were used for fluorescence quantification on a CFX Connect Real-time PCR amplifier (Bio-Rad, Richmond, VA, USA) with TB Green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, Kyodo, Japan). The levels of LC3/BECN1/Inx4/Cas3/p53 mRNA were analyzed using the threshold and Ct (threshold cycle) values according to the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

4.5. Apoptotic staining (TUNEL)

Apoptotic staining was performed using the One-step TUNEL Cell Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN Biotech, Jiangsu, China) with the red TRITC labeled fluorescence detection method, following the manufacturer's instructions. The stained samples were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI8, Wetzlar, Germany).

4.6. Data statistics

Only symptoms with a frequency of more than 75% were considered as meaningful typical deformity symptoms for recording and comparison. Data statistics were performed using the statistical software SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., USA). Data that did not conform to a normal distribution were transformed by natural logarithm before further analysis. Significance testing was conducted using one-way ANOVA (Duncan’s multiple range tests). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (p < 0.05). All data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD).

5. Conclusions

In summary, by analysis the study results of morphology, histology, and expression changes of autophagy marker genes (LC3/BECN1), autophagy-related gene (Inx4), and apoptosis-related genes (Cas3/p53) during the embryonic development of S. japonica at different temperatures, revealed that the most sensitive developmental stages were the Early blastula, Blastopore closure, and stages from Optic vesicle to Caudal end. S. japonica embryos exhibited greater sensitivity and intolerance to excessive temperature, with specific manifestations such as significantly higher embryo mortality in the high-temperature (28 ℃) group compared to the low-temperature (18 ℃) group. Moreover, embryonic malformations caused by high temperature (28 ℃) were more severe, characterized by swelling of the visceral mass, exposed gills, and ectropion mantle. Furthermore, an increase in temperature (28 ℃) led to a shorter the embryonic development duration, while a decrease in temperature (18 ℃) had the opposite effect. Therefore, our study demonstrated for the first time that maintaining the appropriate incubation temperature (around 23 ℃) during these sensitive stages (Early blastula, Blastopore closure, and stages from Optic vesicle to Caudal end) is crucial for survival and normal development of S. japonica embryos. High temperature (28 ℃), caused by heat waves or cultivation conditions is more harmful to embryos than low temperature (18 ℃). Additionally, we observed that the sensitive stages of gene changes related to autophagy/apoptosis roughly corresponded to the sensitive stages of malformation and high mortality, indicating a strong correlation and potential crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in embryonic response to temperature, which also provides intriguing insights for future research.

Author Contributions

Yifan Liu and Long Chen performed most of the laboratory analyses and wrote the manuscript; Bingjian Liu and Zhenming Lv designed the study, revised the manuscript, and provided the funding; Fang Meng and Jun Luo helped with the sample collection; Tao Zhang and Huilai Shi provided the broodstock and embryos; Shuang Chen helped with the daily feeding and seawater changes.

Funding

This research was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LY20C190008, LY22D060001), Science and technology project of Marine Fisheries Research Institute of Zhejiang (No. HYS-CZ-202203).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the laboratory for their technical advice and helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akopian A, Atlasz T, Pan F, Wong S, Zhang Y, Volgyi B, Paul DL, Bloomfield SA. Gap junction-mediated death of retinal neurons is connexin and insult specific: a potential target for neuroprotection. J Neurosci 2014, 34, 10582–10591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aritaki M, Ohta K, Hotta Y, Tagawa M, Tanaka M. Temperature effects on larval development and occurrence of metamorphosis-related morphological abnormalities in hatchery-reared spotted halibut Verasper variegatus juveniles (in Japanese with English abstract). Nippon Suisan Gakk 2004, 70, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdiguian S, Martinand-Mari C, Mangeat P. Using Ciona to study developmental programmed cell death. Semin Cancer Biol 2007, 17, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer R, Löer B, Ostrowski K, Martini J, Weimbs A, Lechner H, Hoch M Intercellular communication: the Drosophila innexin multiprotein family of gap junction proteins. Chem Biol 2005, 12, 515–526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejarano E, Yuste A, Patel B, Stout RF, Jr Spray DC, Cuervo AM. Connexins modulate autophagosome biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2014, 16, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. Gap junction gene and protein families: Connexins, innexins, and pannexins. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018, 1860, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletzky SV (1987) Embryonic phase. In: Boyle, P.R. (Ed.), Cephalopod Life Cycles. vol.2. Acad Press, London, pp. 5–31.

- Boletzky, SV. Embryonic development of cephalopods at low temperatures. Antarct Sci 1994, 6, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletzky, SV. Biology of early life stages in cephalopod molluscs. Adv Mar Biol 2003, 44, 143–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga R, Van der Molen S, Pontones J, Ortiz N. Embryonic development, hatching time and newborn juveniles of Octopus tehuelchus under two culture temperatures. Aquaculture 2021, 530, 735778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Zhao FG, Chen KX, Guo YH, Liang Y, Zhao HY, Chen SL. Exposure of zebrafish to a cold environment triggered cellular autophagy in zebrafish liver. J Fish Dis 2022, 45, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen YF, Culetto E, Legouis R A. DRP-1 dependent autophagy process facilitates rebuilding of the mitochondrial network and modulates adaptation capacity in response to acute heat stress during C. elegans development. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2654–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng CH, Yang FF, Liao SA, Miao YT, Ye CX, Wang AL, Tan JW, Chen XY. High temperature induces apoptosis and oxidative stress in pufferfish (Takifugu obscurus) blood cells. J Therm Biol 2015, 53, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlke FT, Wohlrab S, Butzin M, Prtner HO. Thermal bottlenecks in the life cycle define climate vulnerability of fish. Science 2020, 369, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das S, Shukla N, Singh SS, Kushwaha S, Shrivastava R Mechanism of interaction between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 512–533. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues PM, Bettencourt V, Guerra A. Growth of Sepia officinalis in captivity and in nature. Vie Milieu 2006, 56, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxa CK, Sfakianakis D, Sterioti A, Kentouri M. Effect of temperature on the development of deformities during the embryonic stages of Charonia seguenzae (Aradas & Benoit, 1870). J Therm Biol 2021, 100, 103046. [CrossRef]

- Duan ZH, Duan XY, Zhao S, Wang XL, Wang J, Liu YB, Peng YW, Gong ZY, Wang L. Barrier function of zebrafish embryonic chorions against microplastics and nanoplastics and its impact on embryo development. J Hazard Mater 2020, 395, 122621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar G, Shao ZH, Higashitani N, Kikuta M, Izumi M, Higashitani A. Autophagy mitigates high-temperature injury in pollen development of Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev Biol 2019, 456, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao WJ, Li HX, Feng J. Transcriptome Analysis in High Temperature Inhibiting Spermatogonial Stem Cell Differentiation In Vitro. Reprod Sci 2023, 30, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 2010, 221, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiet J, Aumont O, Poggiale JC, Maury O. Effects of lower trophic level biomass and water temperature on fish communities: A modelling study. Prog Oceanog 2016, 146, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong SM, Kang SW, Goo TW, Kim NS, Lee JS, Kim KA, Nho SK. Two gap junction channel (innexin) genes of the Bombyx mori and their expression. J Insect Physiol 2008, 54, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu CL, Chen LB, Hu CF, Han BS. Research on the role of autophagy in cell cold stress. Chin J Cell Biol 38 2016, 1077-1083. (in Chinese).

- Huang RP, Hossain MZ, Huang R, Gano J, Fan Y, Boynton AL. Connexin 43 (Cx43) enhances chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Int J Cancer 2001, 92, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang DH, Zheng XD, Qian YS, Zhang QQ. Development of Amphioctopus fangsiao (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) from eggs to hatchlings: indications for the embryonic developmental management. Mar Life Sci Technol 2020, 2, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang XM, Lu ZR, He HJ, Ye BL, Ying Z, Wang CL. Effects of several ecological factors on the hatching of Sepiella maindroni wild and cultured eggs. Chin J App Ecol, 2010, 21, 1321–1326. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jing HR, Luo FW, Liu XM, Tian XF, Zhou Y. Fish oil alleviates liver injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion via AMPK/SIRT-1/autophagy pathway. World J Gastroenterol 2018, 24, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanduc D, Mittelman A, Serpico R, Sinigaglia E, Sinha AA, Natale C, Santacroce R, Di Corcia MG, Lucchese A, Dini L, Pani P, Santacroce S, Simone S, Bucci R, Farber E. Cell death: apoptosis versus necrosis (review). Int J Oncol 2022, 21, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis S, Grondin M, Averill-Bates DA. Heat shock increases levels of reactive oxygen species, autophagy and apoptosis. BBA-Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868, 118924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur AP, Agrawal S. A review of the molecular mechanism of apoptosis and its role in pathological conditions. Int J Pharm Bio Sci 2019, 10, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim MJ, Kim JA, Lee DW, Park YS, Kim JH, Choi CY. Oxidative stress and apoptosis in disk abalone (Haliotis discus hannai) caused by water temperature and pH changes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li AJ, Leung PT, Bao VW, Lui GC, Leung KM. Temperature-dependent physiological and biochemical responses of the marine medaka Oryzias melastigma with consideration of both low and high thermal extremes. J Therm Biol 2015, 54, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li B, Xian JA, Guo H, Wang AL, Miao YT, Ye JM, Ye CX, Liao SA. Effect of temperature decrease on hemocyte apoptosis of the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquacult Int 2014, 22, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li D, Dorber M, Barbarossa V, Verones F. Global characterization factors for quantifying the impacts of increasing water temperature on freshwater fish. Ecol Indic 2022, 142, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li X, Shi BY, Li Q, Liu SK. High temperature aggravates mortalities of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) infected with Vibrio: A perspective from homeostasis of digestive microbiota and immune response. Aquaculture 2023, 568, 739309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Jian Z, Meng YS, Peng WL, Zhu Y, Jiang YH, Luo GP, Tang FQ, Xiao YB. Chronic hypoxia induces myocardial autophagy in mice. J Third Mi Med Univ 2017, 39, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu HB, Wu XQ, Feng Y, Rui L. Autophagy contributes to the feeding, reproduction, and mobility of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus at low temperatures. Acta Bioch Bioph Sin 2019, 51, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu HH, Huo LP, Yu QH, Ge DL, Chi CF, Lv ZM, Wang TM. Molecular insights of a novel cephalopod toll-like receptor homologue in Sepiella japonica, revealing its function under the stress of aquatic pathogenic bacteria. Fish Shellfish Immun 2019, 90, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu LQ, Zhao SJ, Zhang Y, Wang MT, Yan YJ, Lv ZM, Gong L, Liu BJ, Dong YH, Xu ZJ. Identification of Vitellogenin 1 Potentially Related to Reproduction in the Cephalopod, Sepiella japonica. J Shellfish Res 2022, 41, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu T, Li M, Zhang Y, Pang ZY, Xiao W, Yang Y, Luo KJ. A role for Innexin2 and Innexin3 proteins from Spodoptera litura in apoptosis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e7045670456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu ZY, Su YZ, Xie YQ, Zhou RF. Preliminary observation on embryonic development of Sepiella maindroni. Prog Fish Sci 2009, 30, 13–19. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv ZM, Zhu KH, Pang Z, Liu LQ, Jiang LH, Liu BJ, Shi HL, Ping HL, Chi CF, Gong L. Identification, characterization and mRNA transcript abundance profiles of estrogen related receptor (ERR) in Sepiella japonica imply its possible involvement in female reproduction. Anim Reprod Sci 2019, 211, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira D, Narciso L, Cabral HN, Vinagre C, Diniz MS. Influence of temperature in thermal and oxidative stress responses in estuarine fish. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2013, 166, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Tong L, Sadoshima J. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting Beclin1-Bcl-2 interaction. Nat Med 2013, 19, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccormick JJ, King KE, Cté MD, Meade RD, Kenny GP. Impaired autophagy following ex vivo heating at physiologically relevant temperatures in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from elderly adults. J Therm Biol 2021, 95, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 2008, 451, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MolluscaBase (2023) Cephalopoda. Available online: http://www.molluscabase.org (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Molina A, Dettleff P, Valenzuela-Muñoz V, Gallardo-Escarate C, Valdés JA. High-Temperature Stress Induces Autophagy in Rainbow Trout Skeletal Muscle. Fishes 2023, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, A. (1928) Cephalopoda embryology. In: Boletzky SV (ed) Fauna and flora of the Bay of Naples: Part I, vol 2. Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, pp 1-461.

- Nande AM, Domingues P, Rosas C. (2018) Effects of Temperature on the Embryonic Development of Octopus vulgaris. vol. 37. pp. 1013–1019. [CrossRef]

- Obrador E, Jihad-Jebbar A, Salvador-Palmer R, López-Blanch R, Oriol-Caballo M, Moreno-Murciano MP, Navarro EA, Cibrian R, Estrela JM. Externally applied electromagnetic fields and hyperthermia irreversibly damage cancer cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang Z, Zhang Y, Liu LQ. Identification and functional characterization of interferon-γ-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT) gene in common Chinese cuttlefish Sepiella japonica. Fish Shellfish Immun 2019, 86, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang ZY, Li M, Yu DS, Yan Z, Liu XY, Ji XL, Yang Y, Hu JS, Luo KJ. Two innexins of Spodoptera litura influences hemichannel and gap junction functions in cellular immune responses. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2015, 90, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu XP, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, Packer M, Schneider MD, Levine B. Bcl-2 Antiapoptotic proteins inhibit beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 2005, 122, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pype C, Verbueken E, Saad MA, Casteleyn CR, Van Ginneken CJ, Knapen D, Van Cruchten SJ. Incubation at 32.5 °C and above causes malformations in the zebrafish embryo. Reprod Toxicol 2015, 56, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang J, Tao YF, Zhu JH, Lu SQ, Cao ZM, Ma JL, He J, Xu P. Effects of heat stress on follicular development and atresia in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) during one reproductive cycle and its potential regulation by autophagy and apoptosis. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu XP, Zou ZJ, Sun QH, Luby-Phelps K, Cheng PF, Hogan RN, Gilpin C, Levine B. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell 2007, 128, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radonic M, L´opez AV, Oka M, Aristiz´abal EO. Effect of the incubation temperature on the embryonic development and hatching time of eggs of the red porgy Pagrus pagrus (Linne, 1758) (Pisces: Sparidae). Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr 2005, 40, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repolho T, Baptista M, Pimentel MS, Dionısio G, Trübenbach K, Lopes VM, Lopes AR, Calado R, Diniz M, Rosa R. Developmental and physiological challenges of octopus (Octopus vulgaris) early life stages under ocean warming. J Comp Physiol B 2014, 184, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruperez C, Blasco-Roset A, Kular D, Cairo M, Ferrer-Curriu G, Villarroya J, Zamora M, Crispi F, Villarroya F, Planavila A. Autophagy is Involved in Cardiac Remodeling in Response to Environmental Temperature Change. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 864427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas M, Tuchweber B, Kourounakis P, Selye H. Temperature-dependence of stress-induced hepatic autophagy. Experientia 1977, 33, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato H, Fukumoto K, Hada S, Hagiwara H, Fujimoto E, Negishi E, Ueno K, Yano T. Enhancing effect of connexin 32 gene on vinorelbine-induced cytotoxicity in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Chemoth Pharm 2007, 60, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seul KH, Kang KY, Lee KS, Kim SH, Beyer EC. Adenoviral delivery of human connexin37 induces endothelial cell death through apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 319, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabad ZA, Avci CB, Bani F, Zarebkohan A, Sadeghizadeh M, Salehi R, Ghafarkhani M, Rahbarghazi R, Bagca BG, Ozates NP. Photothermal effect of albumin-modified gold nanorods diminished neuroblastoma cancer stem cells dynamic growth by modulating autophagy. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 11774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman M, Chadha NK, Madhu K, Madhu R, Sawant PB, Francis B. Optimization of temperature improves embryonic development and hatching efficiency of false clown fish, Amphiprion ocellaris Cuvier, 1830 under captive condition. Aquaculture 2021, 536, 736417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun LQ, Gao JL, Zhao MM, Cui JZ, Li YX, Yang XJ, Jing XB, Wu ZX. A novel cognitive impairment mechanism that astrocytic p-connexin 43 promotes neuronic autophagy via activation of P2X7R and down-regulation of GLT-1 expression in the hippocampus following traumatic brain injury in rats. Behav Brain Res 2015, 291, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Fraizer GC, De LCJ, Cristiano RJ, Liebert M, Grossman HB. Connexin 26 enhances the bystander effect in HSVtk/GCV gene therapy for human bladder cancer by adenovirus/PLL/DNA gene delivery. Gene Ther 2001, 8, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji M, Abe H, Hanyuu K, Kuriyama I, Tsuchihashi Y, Tsumoto K, Nigou T, Kasuya T, Katou T, Kawamura T, Okada K, Uji S, Sawada Y. Effect of temperature on survival, growth and malformation of cultured larvae and juveniles of the seven-band grouper Epinephelus septemfasciatus. Fish Sci 2014, 80, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte I, Espinoza V, Herrera M, Zúñiga O, Olivares A, Carbonell P, Pino S, Farías A, Rosas C. Effect of temperature on embryonic development of Octopus mimus under controlled conditions. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 2012, 416-417, 168–175. [CrossRef]

- Vagner M, Zambonino-Infante JL, Mazurais D. Fish facing global change: are early stages the lifeline? Mar Environ Res 2019, 147, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshavsky, A. The Ubiquitin System, Autophagy, and Regulated Protein Degradation. Annu Rev Biochem 2017, 86, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinagre C, Madeira D, Narciso L, Cabral HN, Diniz M. Effect of temperature on oxidative stress in fish: Lipid peroxidation and catalase activity in the muscle of juvenile seabass, Dicentrarchus labrax. Ecol Indic 2012, 23, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada T, Takegaki T, Mori T, Natsukari Y. Reproductive Behavior of the Japanese Spineless Cuttlefish Sepiella japonica. Venus 2018, 65, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang SP, Chen FY, Dong L, Dong LX, Zhang YQ, Chen HY, Qiao K, Wang KJ. A novel innexin2 forming membrane hemichannel exhibits immune responses and cell apoptosis in Scylla paramamosain. Fish Shellfish Immun 2015, 47, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang SP, Chen FY, Zhang YQ, Ma XW, Qiao K. Gap junction gene innexin3 being highly expressed in the nervous system and embryonic stage of the mud crab scylla paramamosain. J Oceanol Limnol 2019, 37, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wear D, Bhagirath E, Balachandar A, Vegh C, Pandey, S. Autophagy Inhibition via Hydroxychloroquine or 3-Methyladenine Enhances Chemotherapy-Induced Apoptosis in Neuro-Blastoma and Glioblastoma. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei JL, Ma ZL, Li YL, Zhao BT, Wang DT, Jin Y, Jin YX. miR-143 inhibits cell proliferation by targeting autophagy-related 2B in non-small cell lung cancer H1299 cells. Mol Med Rep 2015, 11, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirawan E, Vanden Berghe T, Lippens S, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Autophagy: for better or for worse. Cell Res 2012, 22, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi HY, Wang S, Wang BB, Hong XL, Liu XP, Li MC, Shen RX, Dong QX. The role of interaction between autophagy and apoptosis in tumorigenesis. Oncol Rep 2022, 48, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu DJ, Jiang XH, He HS, Liu DB, Yang L, Chen HL, Wu L, Geng GX, Li QW. SIRT2 functions in aging, autophagy, and apoptosis in post-maturation bovine oocytes. Life Sci 2019, 232, 116639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan SJ, Akey CW. Apoptosome structure, assembly, and procaspase activation. Structure 2013, 21, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Yao F, Zhang H, Li N, Zou X, Sui L, Hou L. The Potential Roles of the Apoptosis-Related Protein PDRG1 in Diapause Embryo Restarting of Artemia sinica. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao XY, Yin XL, Ma TZ, Song WH, Zhang XL, Liu BJ, Liu YF, Yan XJ. The effect of chloroquine on large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea): From autophagy, inflammation, to apoptosis. Aquacult Rep 2023, 28, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu XP, Wei CQ, Zhao WH, Du HJ, Chen YL, Gui JF. Effects of incubation temperatures on embryonic development in the Asian yellow pond turtle. Aquaculture 2006, 259, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).