Submitted:

27 September 2023

Posted:

28 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

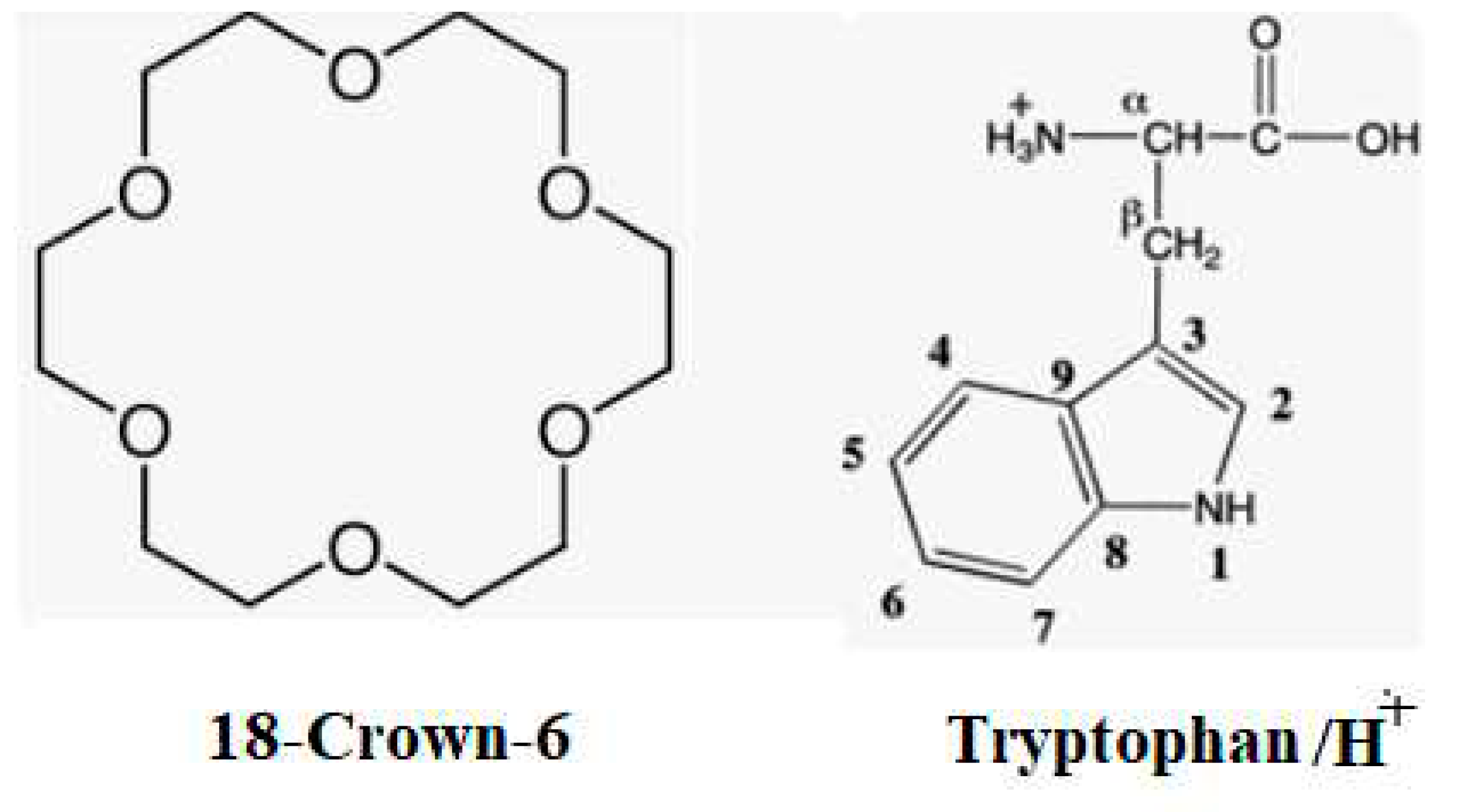

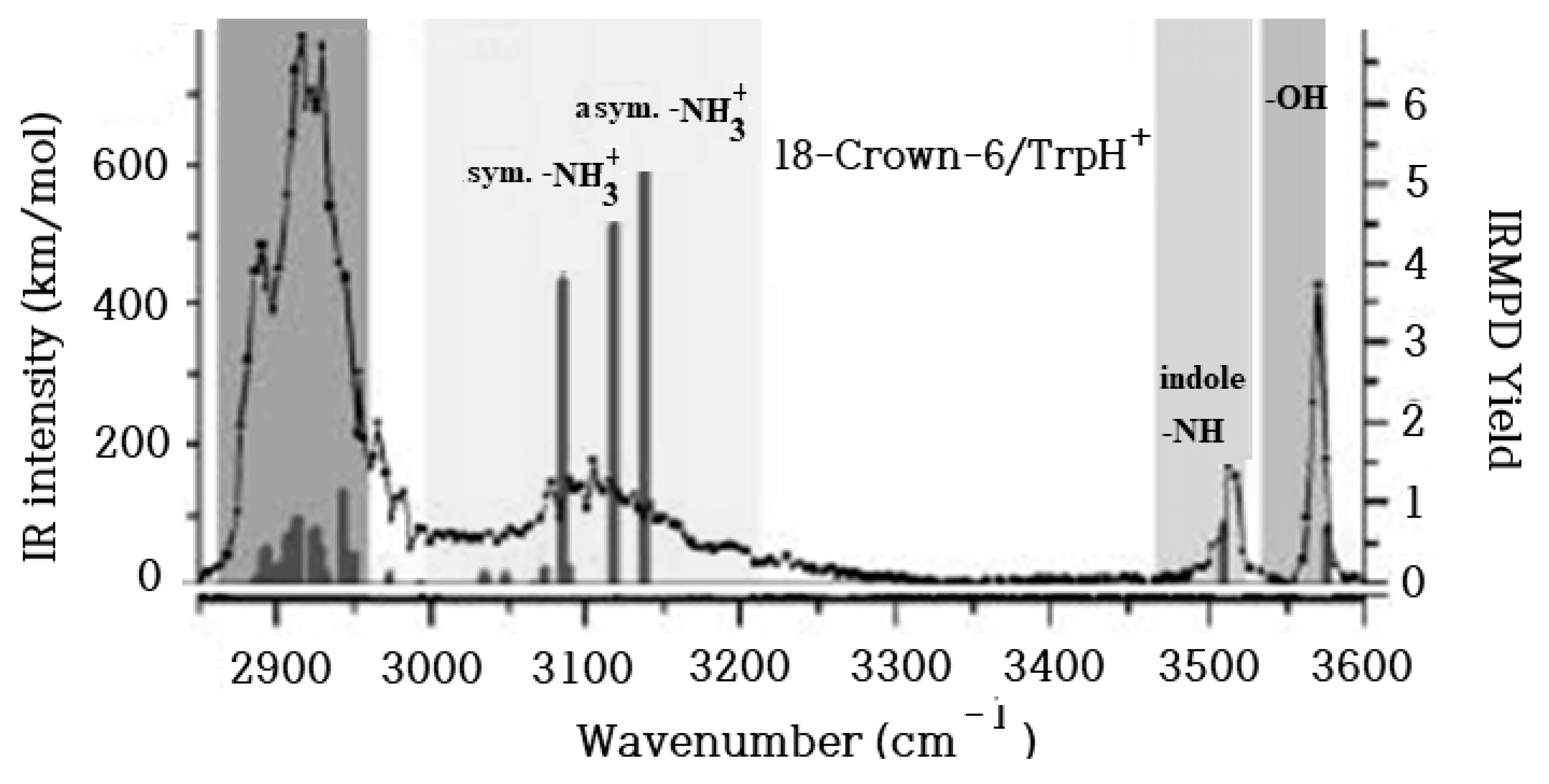

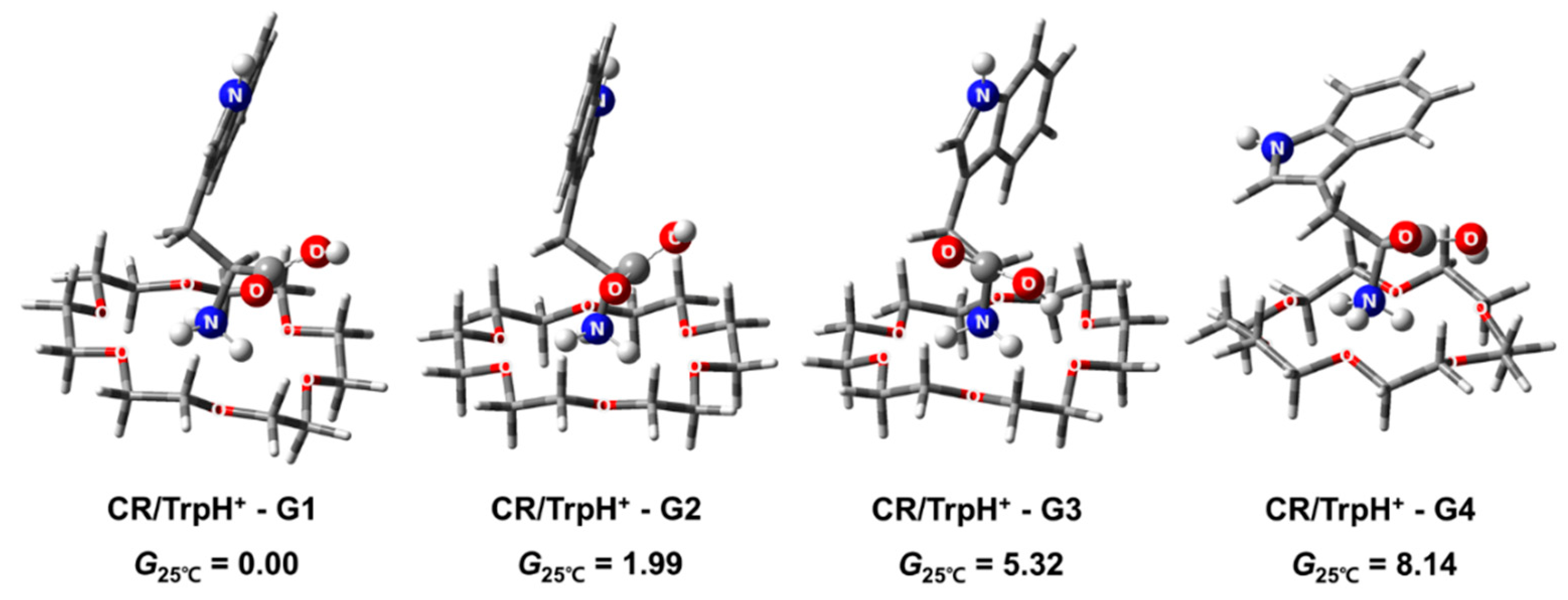

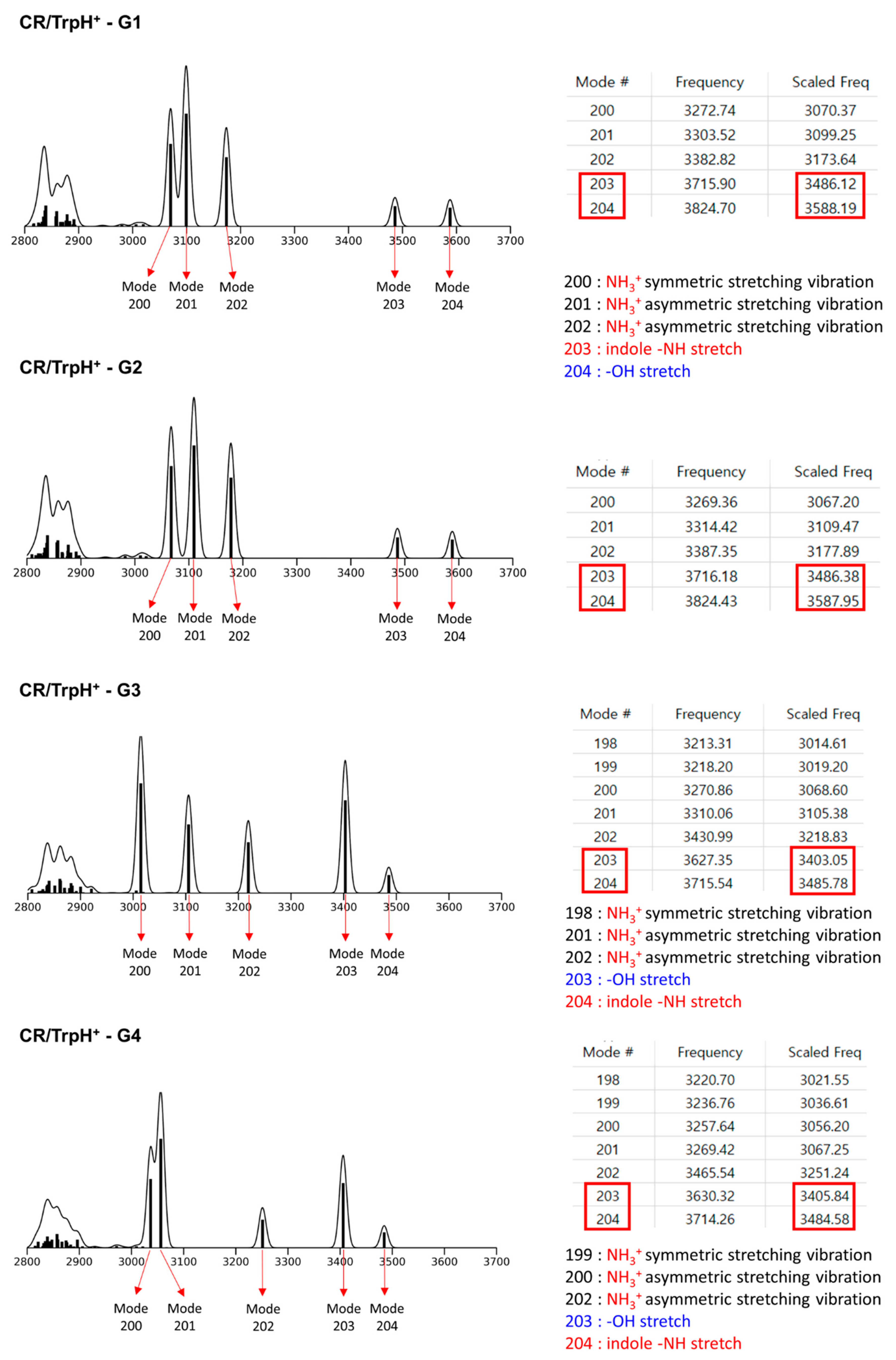

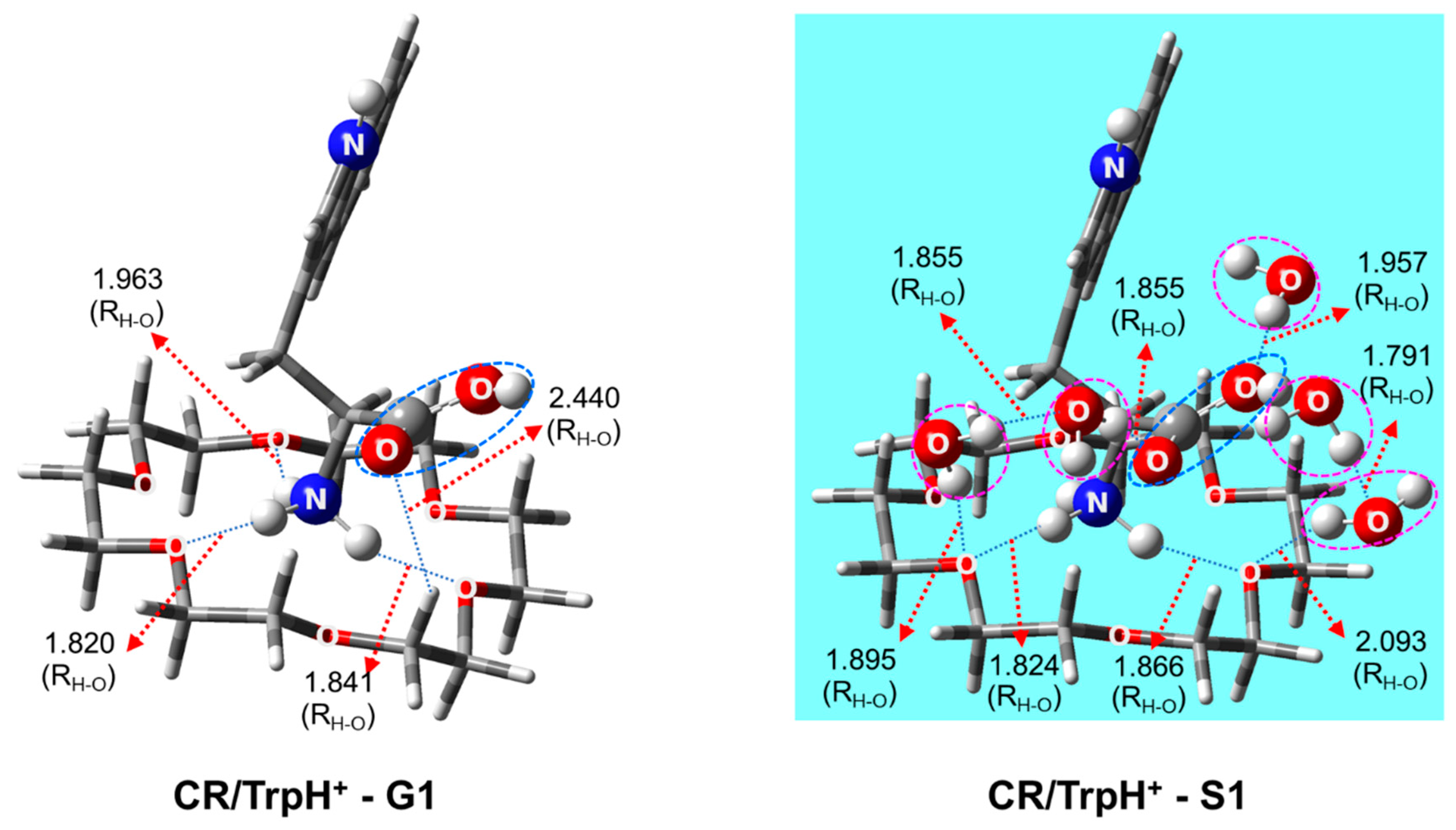

2.1. Structures and Thermodynamic Stability of 18-Crown-6/TrpH+ Non-Covalent Complexes in the Gas Phase

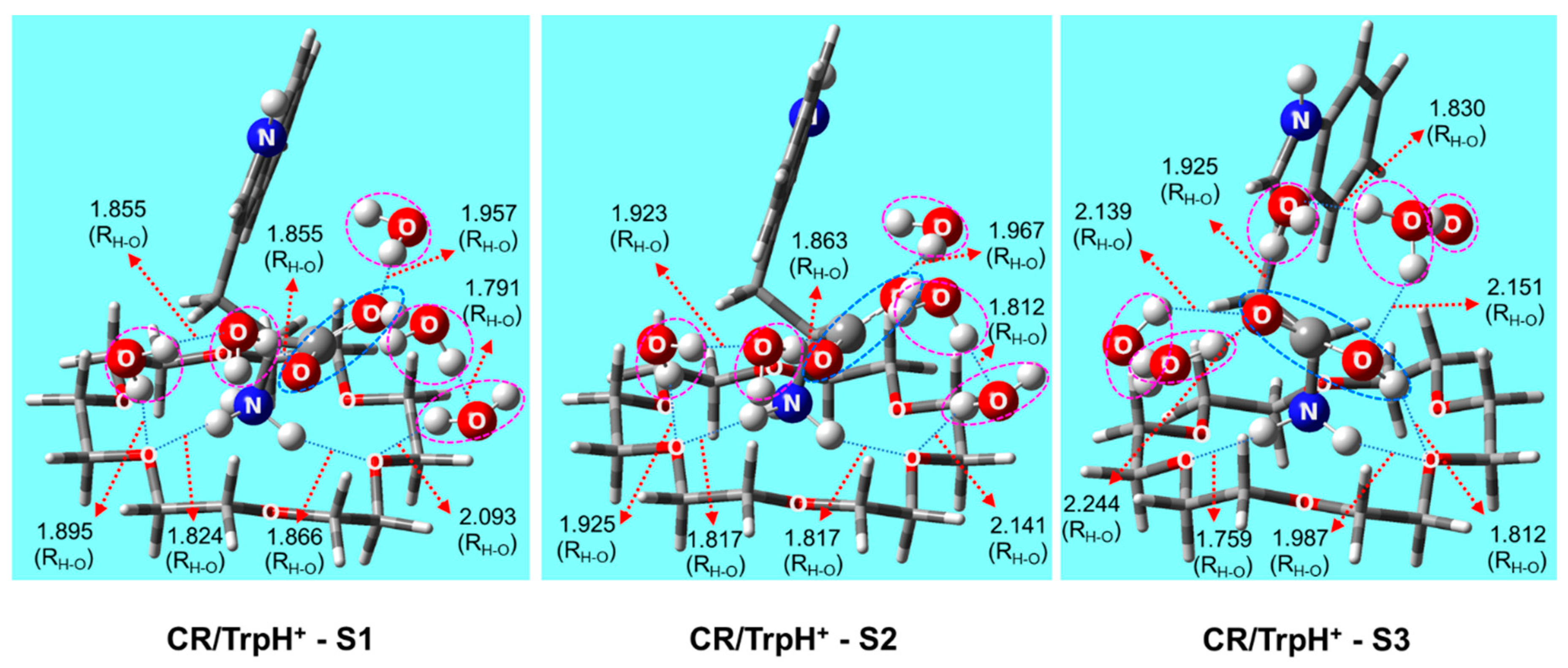

2.2. Structures of 18-Crown-6/TrpH+ Non-Covalent Complexes in Solution

3. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Robert, F. How Far Can We Push Chemical Self-Assembly? Science (80-. ). 2005, 309, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Percec, V.; Dulcey, A.E.; Balagurusamy, V.S.K.; Miura, Y.; Smidrkal, J.; Peterca, M.; Nummelin, S.; Edlund, U.; Hudson, S.D.; Heiney, P.A. Self-Assembly of Amphiphilic Dendritic Dipeptides into Helical Pores. Nature 2004, 430, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.E.; Zuckerman, J.E.; Choi, C.H.J.; Seligson, D.; Tolcher, A.; Alabi, C.A.; Yen, Y.; Heidel, J.D.; Ribas, A. Evidence of RNAi in Humans from Systemically Administered SiRNA via Targeted Nanoparticles. Nature 2010, 464, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, D.; Geng, J.; Loh, X.J.; Das, D.; Lee, T.; Scherman, O.A. Supramolecular Peptide Amphiphile Vesicles through Host–Guest Complexation. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9633–9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.-H.; Wang, Q.-C.; Zhang, Q.-W.; Ma, X.; Tian, H. Photoresponsive Host–Guest Functional Systems. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7543–7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Y. Biomedical Applications of Supramolecular Systems Based on Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7794–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, X.; Scherman, O.A. Supramolecular Chemistry at Interfaces: Host–Guest Interactions for Fabricating Multifunctional Biointerfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Wei, T.; Yu, Q.; Chen, H. Fabrication of Supramolecular Bioactive Surfaces via β-Cyclodextrin-Based Host–Guest Interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 36585–36601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Agasti, S.S.; Zhu, Z.; Isaacs, L.; Rotello, V.M. Recognition-Mediated Activation of Therapeutic Gold Nanoparticles inside Living Cells. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Caballero, F.; Rousseau, C.; Christensen, B.; Petersen, T.E.; Bols, M. Remarkable Supramolecular Catalysis of Glycoside Hydrolysis by a Cyclodextrin Cyanohydrin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3238–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgaldian, P.; Pieles, U. Cyclodextrin Derivatives as Chiral Supramolecular Receptors for Enantioselective Sensing. Sensors 2006, 6, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.-D.; Tang, G.-P.; Chu, P.K. Cyclodextrin-Based Host–Guest Supramolecular Nanoparticles for Delivery: From Design to Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, K.; Nishiyama, N.; Kataoka, K. Rational Design of Smart Supramolecular Assemblies for Gene Delivery: Chemical Challenges in the Creation of Artificial Viruses. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2562–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguiano-Igea, S.; Otero-Espinar, F.J.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Blanco-Méndez, J. Interaction of Clofibrate with Cyclodextrin in Solution: Phase Solubility, 1H NMR and Molecular Modelling Studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 5, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiron, D.; Iori, R.; Pilard, S.; Rajan, T.S.; Landy, D.; Mazzon, E.; Rollin, P.; Djedaïni-Pilard, F. A Combined Approach of NMR and Mass Spectrometry Techniques Applied to the α-Cyclodextrin/Moringin Complex for a Novel Bioactive Formulation. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.Z.; Li, L.; Qiu, X.M.; Liu, F.; Yin, B.L. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry and 1H NMR Studies on Host-Guest Interaction of Paeonol and Two of Its Isomers with β-Cyclodextrin. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 316, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsutdinova, N.A.; Strelnik, I.D.; Musina, E.I.; Gerasimova, T.P.; Katsyuba, S.A.; Babaev, V.M.; Krivolapov, D.B.; Litvinov, I.A.; Mustafina, A.R.; Karasik, A.A.; et al. Host-Guest" Binding of a Luminescent Dinuclear Au(i) Complex Based on Cyclic Diphosphine with Organic Substrates as a Reason for Luminescence Tuneability. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 9853–9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incavo, J.A.; Dutta, P.K. Zeolite Host-Guest Interactions: Optical Spectroscopic Properties of Tris(Bipyridine)Ruthenium(II) in Zeolite Y Cages. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 3075–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesu, J.G.; Visser, T.; Beale, A.M.; Soulimani, F.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Host-Guest Chemistry of Copper(II)-Histidine Complexes Encaged in Zeolite Y. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2006, 12, 7167–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, J.B.; Mann, M.; Meng, C.K.; Wong, S.F.; Whitehouse, C.M. Electrospray Ionization for Mass Spectrometry of Large Biomolecules. Science (80-. ). 1989, 246, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, B.N.; Ganguly, A.K.; Gross, M.L. Applied Electrospray Mass Spectrometry: Practical Spectroscopy Series Volume 32; CRC Press, 2002; Vol. 32; ISBN 0203909275.

- Kebarle, P.; Verkerk, U.H. Electrospray: From Ions in Solution to Ions in the Gas Phase, What We Know Now. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2009, 28, 898–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konermann, L.; Ahadi, E.; Rodriguez, A.D.; Vahidi, S. Unraveling the Mechanism of Electrospray Ionization 2013.

- Monge, M.E.; Harris, G.A.; Dwivedi, P.; Fernández, F.M. Mass Spectrometry: Recent Advances in Direct Open Air Surface Sampling/Ionization. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 2269–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takats, Z.; Wiseman, J.M.; Gologan, B.; Cooks, R.G. Mass Spectrometry Sampling under Ambient Conditions with Desorption Electrospray Ionization. Science (80-. ). 2004, 306, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cescutti, P.; Garozzo, D.; Rizzo, R. Effect of Methylation of β-Cyclodextrin on the Formation of Inclusion Complexes with Aromatic Compounds. An Ionspray Mass Spectrometry Investigation. Carbohydr. Res. 1997, 302, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Cui, M.; Liu, S.; Song, F.; Elkin, Y.N. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry of Cyclodextrin Complexes with Amino Acids in Incubated Solutions and in Eluates of Gel Permeation Chromatography. Rapid Commun. mass Spectrom. 1998, 12, 2016–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomens, J.; Sartakov, B.G.; Meijer, G.; Von Helden, G. Gas-Phase Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Mass-Selected Molecular Ions. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 254, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.F.; O’Brien, J.T.; Prell, J.S.; Saykally, R.J.; Williams, E.R. Infrared Spectroscopy of Cationized Arginine in the Gas Phase: Direct Evidence for the Transition from Nonzwitterionic to Zwitterionic Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuderi, D.; Lepere, V.; Piani, G.; Bouchet, A.; Zehnacker-Rentien, A. Structural Characterization of the UV-Induced Fragmentation Products in an Ion Trap by Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Le Barbu-Debus, K.; Scuderi, D.; Zehnacker-Rentien, A. Mass Spectrometry Study and Infrared Spectroscopy of the Complex between Camphor and the Two Enantiomers of Protonated Alanine: The Role of Higher-energy Conformers in the Enantioselectivity of the Dissociation Rate Constants. Chirality 2013, 25, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, M.; Wilson, K.; Marta, R.; Hasan, M.; Hopkins, W.S.; McMahon, T. Assessing the Impact of Anion–π Effects on Phenylalanine Ion Structures Using IRMPD Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 24223–24234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, P.; Gámez, F.; Hamad, S.; Martínez-Haya, B.; Steill, J.D.; Oomens, J. Crown Ether Complexes with H3O+ and NH 4+: Proton Localization and Proton Bridge Formation. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 7275–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNary, C.P.; Nei, Y.W.; Maitre, P.; Rodgers, M.T.; Armentrout, P.B. Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Action Spectroscopy of Protonated Glycine, Histidine, Lysine, and Arginine Complexed with 18-Crown-6 Ether. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12625–12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polfer, N.C. Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy of Trapped Ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azargun, M.; Fridgen, T.D. Guanine Tetrads: An IRMPD Spectroscopy, Energy Resolved SORI-CID, and Computational Study of M (9-Ethylguanine) 4+(M= Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs) in the Gas Phase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 25778–25785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Breuker, K.; Sze, S.K.; Ge, Y.; Carpenter, B.K.; McLafferty, F.W. Secondary and Tertiary Structures of Gaseous Protein Ions Characterized by Electron Capture Dissociation Mass Spectrometry and Photofragment Spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 15863–15868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, M.; Oh, Y.-H.; Lee, S.; Kong, X. Distinguishing Gas Phase Lactose and Lactulose Complexed with Sodiated L-Arginine by IRMPD Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Steill, J.D.; Oomens, J.; Jockusch, R.A. Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Action Spectroscopy and Computational Studies of Mass-Selected Gas-Phase Fluorescein and 2′, 7′-Dichlorofluorescein Ions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 9739–9747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Loire, E.; Fridgen, T.D. Hydrogen Bonding in Alkali Metal Cation-Bound i-Motif-like Dimers of 1-Methyl Cytosine: An IRMPD Spectroscopic and Computational Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 11103–11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Hoffmann, W.; Warnke, S.; Bowers, M.T.; Pagel, K.; von Helden, G. Retention of Native Protein Structures in the Absence of Solvent: A Coupled Ion Mobility and Spectroscopic Study. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14173–14176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.F.; Forbes, M.W.; Jockusch, R.A.; Oomens, J.; Polfer, N.C.; Saykally, R.J.; Williams, E.R. Infrared Spectroscopy of Cationized Lysine and ε-N-Methyllysine in the Gas Phase: Effects of Alkali-Metal Ion Size and Proton Affinity on Zwitterion Stability. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 7753–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Oh, Y.H.; Park, S.; Lee, S.S.; Oh, H. Bin; Lee, S. Unveiling Host–Guest–Solvent Interactions in Solution by Identifying Highly Unstable Host–Guest Configurations in Thermal Non-Equilibrium Gas Phase. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mino Jr, W.K.; Gulyuz, K.; Wang, D.; Stedwell, C.N.; Polfer, N.C. Gas-Phase Structure and Dissociation Chemistry of Protonated Tryptophan Elucidated by Infrared Multiple-Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedwell, C.N.; Galindo, J.F.; Gulyuz, K.; Roitberg, A.E.; Polfer, N.C. Crown Complexation of Protonated Amino Acids: Influence on IRMPD Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, R.; Nispel, M.; Häber, T.; Kleinermanns, K. Gas-Phase FT-IR-Spectra of Natural Amino Acids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 409, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Park, S.; Hong, Y.; Lee, J.U.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, D.; Kong, X.; Lee, S.; Oh, H. Bin Chiral Differentiation of D- and l-Alanine by Permethylated β-Cyclodextrin: IRMPD Spectroscopy and DFT Methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 14729–14737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-S.; Lee, J.; Oh, J.H.; Park, S.; Hong, Y.; Min, B.K.; Lee, H.H.L.; Kim, H.I.; Kong, X.; Lee, S. Chiral Differentiation of D-and L-Isoleucine Using Permethylated β-Cyclodextrin: Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy, Ion-Mobility Mass Spectrometry, and DFT Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 30428–30436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-R.; Lee, S.; Oh, H. Bin Infrared Multiple Photon Dissociation Spectroscopy and Density Functional Theory (DFT) Studies of Protonated Permethylated β-Cyclodextrin–Water Non-Covalent Complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 8376–8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.U.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, S.; Oh, H. Bin Noncovalent Complexes of Cyclodextrin with Small Organic Molecules: Applications and Insights into Host–Guest Interactions in the Gas Phase and Condensed Phase. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J. Da; Head-Gordon, M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom-Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H. Gaussian 16, Gaussian. Inc., Wallingford CT 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marenich, A. V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).