1. Introduction

Arsenic is a highly toxic and hazardous element that is commonly found in numerous mineral deposits [

1]. Arsenic poses severe health and environmental hazards, and frequently co-occurs with gold in ore deposits [

2,

3]. In Ecuador, several studies have reported the presence of high concentrations of arsenic in soils, sediments, surface waters, and tap waters in gold mining areas, mainly in the province of Azuay and El Oro [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, the presence of this element constitutes a concern for mining companies and the community.

Mining companies are now compelled to process ore deposits laden with impurities like antimony, arsenic, mercury, and bismuth, raising both economic and environmental concerns [

9,

10]. Gold-bearing deposits are characterised by low gold recoveries since gold is often chemically bound or encapsulated in sulphide minerals or coexists with carbonaceous matter, restricting conventional cyanide leaching techniques [

10,

11]. Consequently, an arsenal of pretreatment methods, including roasting, pressure oxidation, and bio-oxidation, has been employed to liberate gold for subsequent cyanide solution leaching [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Historically, pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes have been adopted to remove arsenic [

10]. The former leverages as a pretreatment method to oxidise the sulphide for further processing and extraction. This technique, however, often proves uneconomical and poses considerable environmental hazards due to arsenic volatilisation [

17]. As a result, these limitations necessitate exploring alternative, more efficient, and environmentally friendly arsenic treatment processes.

Hydrometallurgical processes present their own set of challenges, including strict environmental regulations on arsenic release, the complexity of gas/dust capture, separation facilities, and the stability of arsenic compounds [

10,

18]. However, they have shown potential in addressing the complicated nature of the pyrometallurgical processes involving arsenic. The choice of arsenic removal technique often depends on the amount of arsenic in solution and the arsenic species present, with precipitation being a widely employed method [

14].

Among the metallurgical processes used in the mining industry, leaching stands out as one of the common methods for extracting valuable metals from minerals [

14,

19]. This process involves bringing a liquid phase into contact with a solid phase to separate the desired minerals or eliminate unwanted minerals. In the case of gold extraction, cyanide leaching is widely employed when the ore exhibits favourable metallurgical properties and a low concentration of elemental arsenic, as it proves to be economically viable.

This paper intends to focus on alkaline leaching, a hydrometallurgical process that has shown promise in selectively removing arsenic [

20]. This approach involves subjecting the ore to alkaline treatment before cyanide leaching, aiming to stabilise the solution and reduce the presence of arsenic. It has been demonstrated that this pretreatment can reduce the consumption of sodium cyanide by 70% and increase the gold recovery rate by 80% for ores with high arsenic concentrations.

Ecuador is renowned for its mining potential, boasting an abundance of resources such as gold, silver, copper, and other minerals [

21]. It holds a strategic location and a suitable climate, both conducive to the development of economic activities in general, with the mining industry standing out. This geological wealth has led to the development of the mining industry in various regions of the country, with the Province of El Oro being one of the main sources of economic income in southern Ecuador [

22].

In Atahualpa Canton, specifically in the locality of Cerro Azul, gold extraction faces a significant challenge due to the abundant presence of arsenic in the gold-bearing ore. This toxic element is present in proportions ranging from 4% to 15% by weight, directly affecting the cyanide leaching process. Arsenic acts as a cyanide-consuming agent, depleting the free cyanide present in the leaching solution, thus reducing the efficiency of the process, and raising environmental concerns [

23].

The aim of this study is to apply the alkaline leaching process for arsenic removal in a gold-bearing ore from Miraflores mine, located in Cerro Azul. An experimental reactor will be utilised to conduct the process, aiming to achieve a reduction of up to 60% in the arsenic concentration.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we outline the process of the proposed descriptive, cross-sectional, and experimental study aimed at the removal of arsenic, a significant toxic metalloid that can be found in gold-leaching solutions.

2.1. Sample Selection and Characterisation

We conducted the sample collection using the manual quartering method, specifically employing a split with a cloth [

24]. This method allows for quick and flexible sampling, although it is subject to human error. We selected 10 samples, each weighing 500 g, for the metallurgical tests. We utilised polarised optical microscopy and flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry to characterise the initial sample and determine its parameters such as moisture content, particle size, concentration of payable metals, and detrimental metals for commercialisation. These analyses were performed at the Lima and Portovelo laboratories, respectively.

We followed the Gy method (1982) to determine the minimum required sample size. This method considers the gold grade in the mineral, the general particle form, the specific weight of valuable species, the particle size distribution, and the degree of liberation.

2.2. Mineralogical Analysis by Fire Assay and Atomic Absorption

The selected mineral underwent pulverisation using a ring pulveriser with a maximum capacity of 350 grams per crucible for 1 minute and 25 seconds, resulting in a grinding mesh of approximately -200 microns. Afterwards, we conducted fire assay analysis to determine the gold and silver content in the mineral and atomic absorption analysis to measure the presence of arsenic. The METALOR Laboratory performed these analyses.

We prepared the sample by adding fusion chemicals, selected based on the mineral’s colorimetry for the fire assay analysis. We then placed the mixture in an electric furnace at an approximate temperature of 1050 ºC. This process yielded a button, which we subjected to cupellation to obtain a doré. The doré was weighed and refined to determine the amount of gold and silver present.

Regarding the atomic absorption analysis, we chemically attacked the sample with concentrated nitric acid and hydrochloric acid in a 3:1 ratio, forming aqua regia. We performed the analysis using a Perkins Elmer 300 instrument with a highly sensitive burner, operating at a lamp wavelength of 193.7 nm, an energy of 33 mA, a minimum absorbance of 0.072, a maximum absorbance of 0.285, and a margin of error of ±0.03%. Additionally, one of the samples was sent to the PLENGE laboratory with international accreditation for determining the mineralogical characteristics.

2.3. Preparation of the Leaching Solution

The leaching solution used was sodium sulphide, commercially available in solid form. However, due to its hydrolysis property, the preparation of the sulphide solution leads to the formation of hydrogen sulphide gas (H2S), which is highly toxic. To prevent the hydrolysis of sulphide, we relied on the principle of Chemical Equilibrium stated by Le Chatelier’s law. By increasing the concentration of hydroxide ions (OH-), we were able to shift the direction of the reaction (from products to reactants). For this purpose, sodium hydroxide was used as the alkalising agent.

Therefore, for the preparation of the sulphide solution, stoichiometric calculations determined that a minimum of 1 mole of OH- is required for every 1 mole of S2- (s), or we can express it as 0.53 grams of OH- (Dry Base) for every 1 gram of S2-.

2.4. Experimental Plan - Kinetic Tests to Determine the Effect of Variables

Once we obtained knowledge of the mineral’s mineralogical and physicochemical characteristics, we conducted comparative leaching tests with and without pretreatment. For the pretreatment processes, we fabricated a leaching reactor and added varying doses of the leaching solution (sodium sulphide + sodium hydroxide). We accelerated leaching by continuously agitating the mixture at a high temperature to remove higher amounts of arsenic present in the mineral effectively.

We performed batch leaching tests in the laboratory by preparing mixtures of pulverised gold-bearing ore and water at different pulp densities, thereby varying the liquid-to-solid ratio. We maintained a constant weight of 130 grams for the dry ore (free of moisture) in all tests while adjusting the volume of the solution accordingly. We introduced different doses of the leaching solution (sodium sulphide + caustic soda) into a leaching reactor. To ensure uniform conditions, we agitated the reactor at 500 RPM using a propeller. We maintained a controlled temperature of 90°C throughout the process, monitoring it with a thermometer placed in the middle zone of the reactor.

We controlled the reaction time in hours once the kinetic test conditions were established. After completing the reaction time, we transferred the pulp to a filtration system and poured it onto a filter paper with a porosity grade of 11 microns to prevent any residual leaching solution from remaining in the concentrate. We then repeatedly washed the pulp with distilled water. The final mineral obtained had a moisture content of 3%. Subsequently, we analysed the samples at the METALOR Laboratory using flame atomic absorption spectroscopy to evaluate the final quality of the mineral and leachate.

The chemical reaction during the leaching process is as follows:

To explain the chemical reaction during the leaching process, we transferred the pulp to a vacuum filtration system at the end of the reaction time. We poured it onto a filter paper with a minimal porosity grade, ensuring no residual leaching solution remained in the mineral. We then repeated the washing process with distilled water. The final mineral obtained had a moisture content of 3%. Subsequently, we sand analysed the samples at the METALOR Laboratory using flame atomic absorption spectroscopy to evaluate the final quality of both the mineral and leachate.

We precipitated the toxic leachate with a high arsenic content and a high arsenic content, using thioacetamide in an acidic medium. We then dried the resulting residue and placed it in storage containers for laboratory residual minerals. Later, we processed the residue in a nearby beneficiation plant and transported it to the community tailings pond in Tablón.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Characterisation of the Mineral

Through fire assay analysis, results were obtained for the gold content, 4.32 g/Tm, and the silver content, 146.95 g/Tm. The initial atomic absorption analysis determined the copper, zinc, and arsenic contents, resulting in 0.38%, 2.93%, and 2.53% per metric ton, respectively. These results were later compared with the arsenic removal.

X-ray diffraction analysis evaluated the mineralogical characteristics and components. The sample consisted of quartz, pyrite, chamosite, muscovite, arsenopyrite, sphalerite, diaspore, phlogopite, galena, chalcopyrite, and others, as shown in

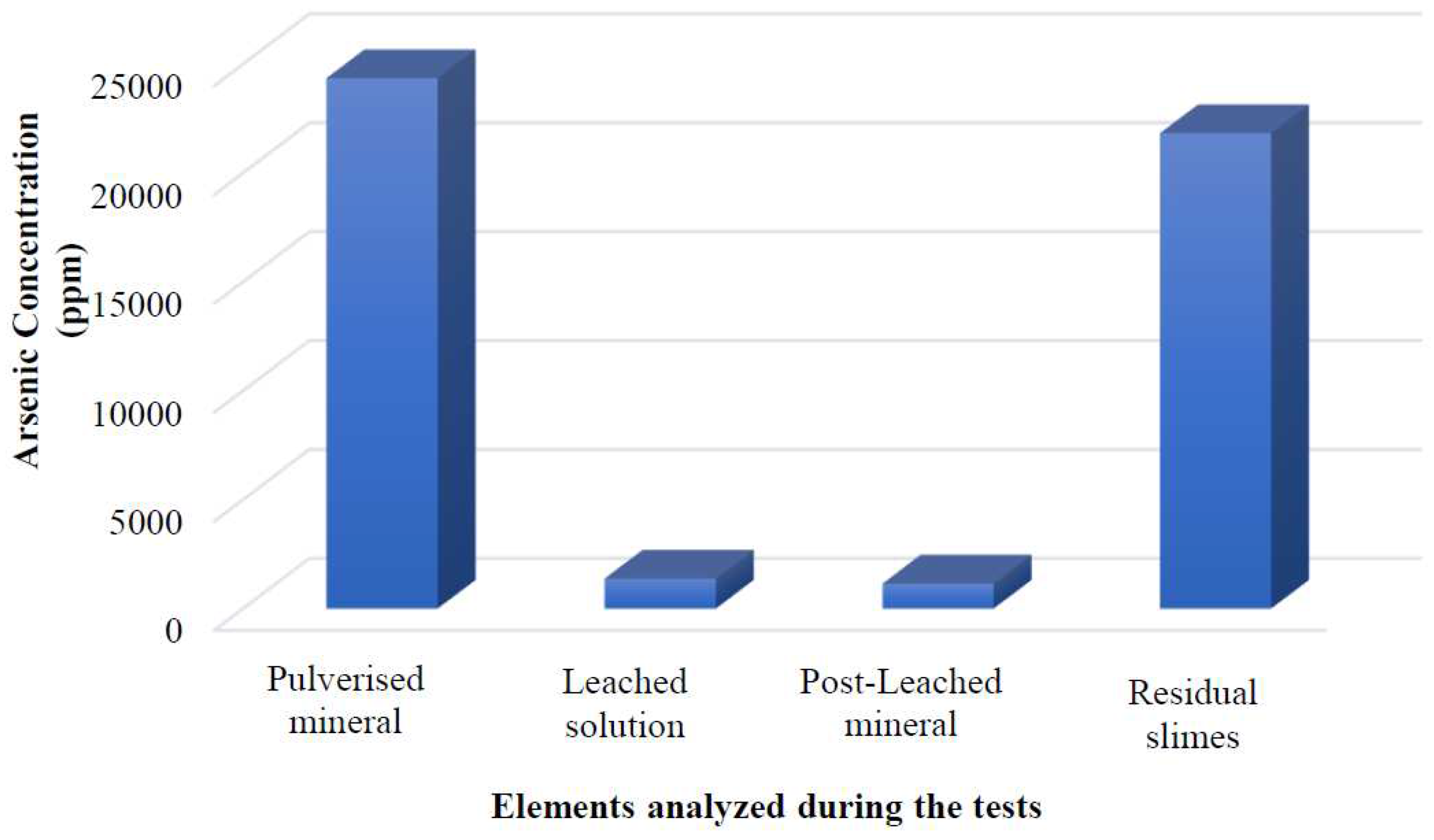

Table 1. Quartz had the highest distribution at 40.8%, while chalcopyrite had the lowest at 1.0%. Similarly, the metallic and non-metallic elements present in the gold-bearing mineral from the Miraflores mine deposit were determined. A high arsenic content of 24357 milligrams per liter was obtained, which corresponds to 2.43% of the mineral.

3.2. Arsenic Removal through Alkaline Leaching

For this process, we homogeneously quartered the mineral and subjected it to a grinding process similar to that used in large-scale operations. The obtained results are presented in

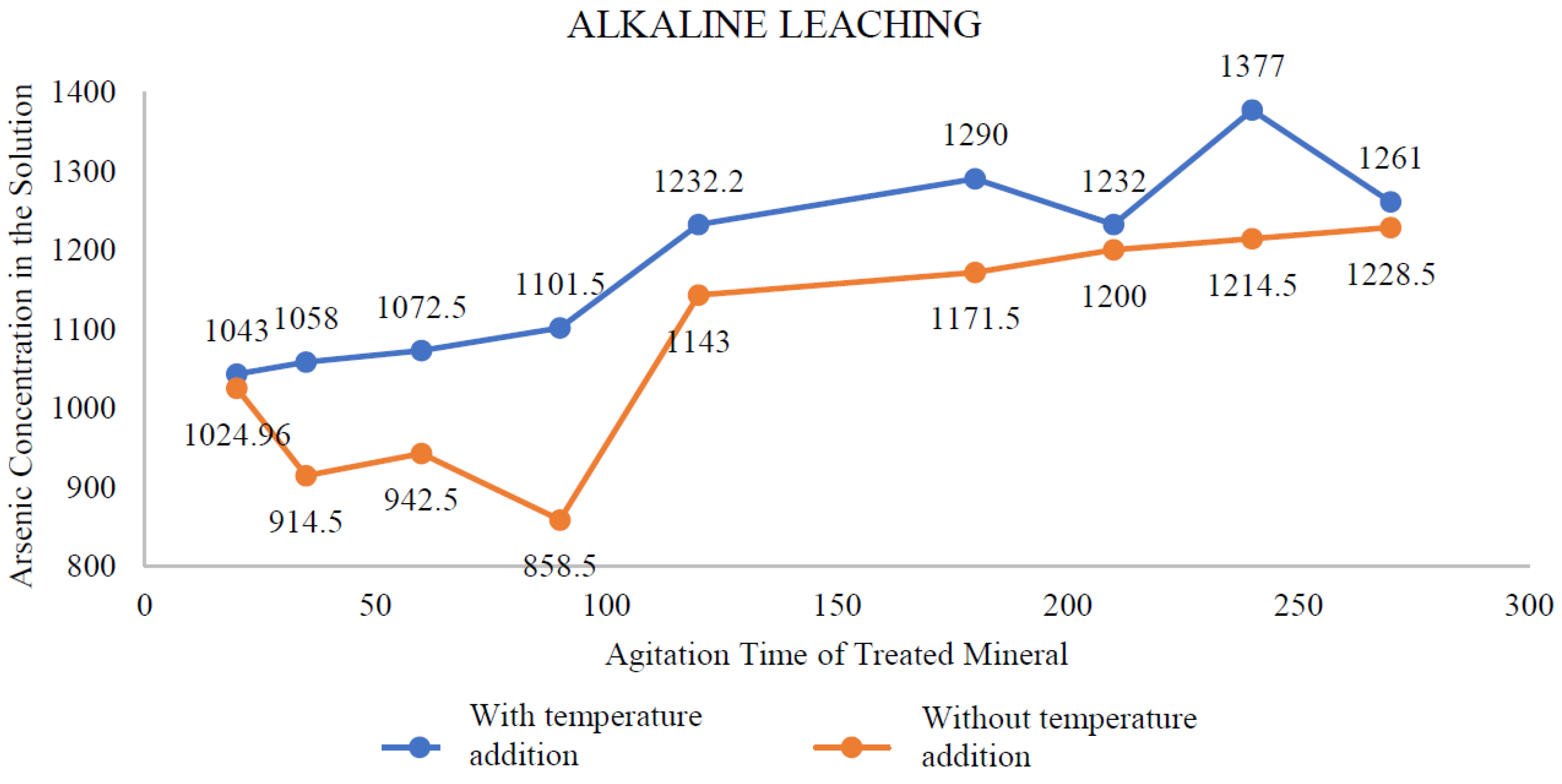

Table 2. We took samples at regular intervals to monitor the leaching of arsenic with increasing heat input. At the fourth hour (240 minutes), the addition of heat achieved removal of 1377 mg/L of arsenic, while without heat addition, the arsenic removal was 1214.50 mg/L at the fourth hour. The study by Anderson (2016) observed that sulphide concentration and temperature were critical factors in maximising leaching.

At the end of the leaching process, we observed the presence of mineral sludge mixed with the reacting chemicals, which exhibited excessive arsenic content in both cases. The sludge did not exceed 2 to 3% of the processed mineral quantity.

The post-leached sample with heat addition had an arsenic content of 0.23% per metric ton, considering that the process generates a certain amount of sludge with a high arsenic content. Conversely, the arsenic content measured 0.27% per metric ton in the process without heat addition.

Figure 1 visually represents the behaviour of alkaline leaching with and without temperature addition, demonstrating similar trends in both cases.

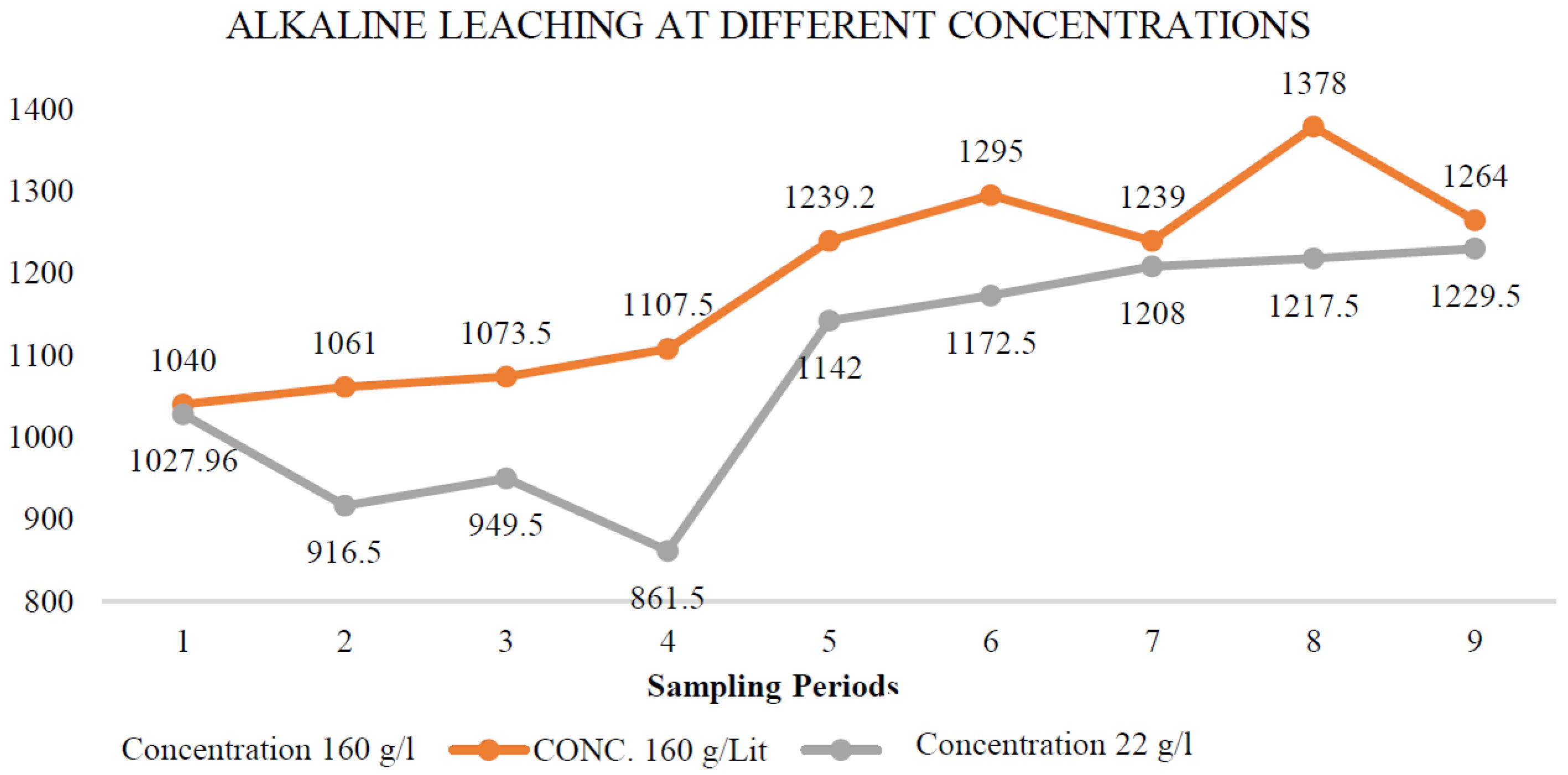

Furthermore,

Figure 2 illustrates the behaviour of alkaline leaching at different concentrations of reactants. It shows that comparable amounts of arsenic were leached with sodium sulphide concentrations of 160 g/L and 22 g/L.

Finally,

Figure 3 displays the results of the alkaline leaching treatment, illustrating the behaviour of the mineral treated with this process and achieving an arsenic removal rate of 90.54% from the mineral.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of our research was the application of alkaline leaching for arsenic removal in gold-bearing ore from the Miraflores Mine. The challenges arsenic presents in gold-bearing ores, especially from this region, are not unique. Several studies have approached arsenic remediation using diverse methodologies, highlighting the global importance of this issue.

In our study, 90.54% arsenic removal efficiency was achieved, enhancing the quality of the ore before metallurgical processes. This aligns with the findings of Anderson [

25], who noted that the concentration of sulphide and temperature were critical factors in maximising gold leaching. Their research underscores the importance of optimising these parameters for effective arsenic removal and gold recovery.

Similarly, Zhang et al. [

13] employed an alkaline leaching approach, using NaOH-H2O2, to address arsenic contamination in copper and cobalt slag. Their results, with arsenic removal efficiency reaching up to 94.5%, further validate our methodology. Using alkaline leaching, especially in high-concentration NaOH solutions, seems to be a promising approach for treating arsenic-rich ores.

Su et al. [

18] proposed a three-step process for arsenic immobilisation using siderite as the iron source. While their focus was on waste sulfuric acid, their efficiency (up to 99.99% arsenic removal) illustrates the potential of using mineral-based methods in arsenic remediation. Their technique could be applied or adapted for gold-bearing ores like the ones in the Miraflores Mine.

Tongamp et al. [

14] worked on removing arsenic impurities in copper ores and concentrates. They applied an alkaline leaching in NaHS media, reminiscent of our study. Their success in achieving arsenic removal rates of over 90% further supports our methodology and the broader application of alkaline leaching.

Regarding the importance of arsenic immobilisation, Nazari et al. [

10] highlighted the challenges arsenic poses in the mining industry. They emphasised the importance, both in hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical processes. Their comprehensive review serves as a reminder of the significance of our research and the global urgency to address arsenic contamination.

The consistent theme across these studies is the necessity to address arsenic in mining activities. Alkaline leaching, as evidenced by our research and supported by other studies, emerges as a promising method for arsenic removal. Future research and collaboration will be essential to refine these techniques and ensure sustainable mining practices globally.

5. Conclusions

The proposed process has been demonstrated to be technically efficient, surpassing the expected arsenic removal percentage by 30%, with an achieved arsenic removal rate of 90.54% from the mineral. The remaining arsenic is present in the alkaline solution, and the process residues are known as sludge.

While adding heat incurred higher economic costs due to combustion, approximately $30 more per alkaline leaching test, it is evident that without heat addition, there is a higher release of arsenic as the agitation time increases. It should be noted that excessive reactant dosages do not improve arsenic removal from the mineral but rather the agitation time.

Implementing this arsenic removal process enhances the quality of the Miraflores mine mineral from the Cerro Azul sector of the Atahualpa canton prior to artisanal miners’ application of metallurgical processes. This, in turn, contributes to the reduction in the use of reagents such as sodium cyanide and, consequently, the profitability of the process.

It is recommended to conduct further laboratory tests with other mineral samples to confirm the preliminary results obtained in this project. Additionally, it is advisable to carry out tests on a larger scale and, if possible, pilot tests. These trials will validate the laboratory findings and demonstrate the technical and economic feasibility of the conducted studies.

The hazardous nature of arsenic in mining necessitates diligent efforts to address its potential risks and find effective and sustainable solutions. Therefore, this study is important in contributing to the advancement of responsible and environmentally conscious mining practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.E.R. and O.R.R.; methodology, E.P.C.; formal analysis, J.M.A. and S.J.O.; investigation, W.E.R., O.R.R. and K.E.S; writing—original draft preparation, W.E.R., O.R.R., E.P.C., S.J.O., J.M.A., K.E.S., D.P.B; writing—review and editing, D.P.B., S.J.O., and K.E.S.; supervision, J.M.A.; project administration, J.M.A., E.P.C., S.J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the Facultad de Ingeniería en Ciencias de la Tierra at the Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral for their support and resources provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Montoya, E.A.R. , Hernández L.E.M., Escareño M.P.L., Balagurusamy N. Impacto del arsénico en el ambiente y su transformación por microorganismos. Terra Latinoamericana. Published online 2015, pp.103-118.

- Hadizadeh, M.; Barakan, S.; Aghazadeh, V. Arsenic Removal from Lead Concentrate-Containing Mimetite Mineral to Solve the Environmental Problem for Smelting Process. J. Sustain. Met. 2021, 7, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, S.L.M.; Lapidus, G.T. Arsenic removal strategy in the processing of an arsenopyritic refractory gold ore. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 203, 105628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Oyola, S.; Valverde-Armas, P.E.; Romero-Crespo, P.; Capa, D.; Valdivieso, A.; Coronel-León, J.; Guzmán-Martínez, F.; Chavez, E. Heavy metal(loid)s contamination in water and sediments in a mining area in Ecuador: a comprehensive assessment for drinking water quality and human health risk. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2023, 45, 4929–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Crespo, P.; Jiménez-Oyola, S.; Salgado-Almeida, B.; Zambrano-Anchundia, J.; Goyburo-Chávez, C.; González-Valoys, A.; Higueras, P. Trace elements in farmland soils and crops, and probabilistic health risk assessment in areas influenced by mining activity in Ecuador. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2023, 45, 4549–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Oyola, S.; Chavez, E.; García-Martínez, M.-J.; Ortega, M.F.; Bolonio, D.; Guzmán-Martínez, F.; García-Garizabal, I.; Romero, P. Probabilistic multi-pathway human health risk assessment due to heavy metal(loid)s in a traditional gold mining area in Ecuador. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 224, 112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Oyola, S.; García-Martínez, M.-J.; Ortega, M.F.; Chavez, E.; Romero, P.; García-Garizabal, I.; Bolonio, D. Ecological and probabilistic human health risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s in river sediments affected by mining activities in Ecuador. Environ. Geochem. Heal. 2021, 43, 4459–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Segovia, K.; Jiménez-Oyola, S.; Garcés-León, D.; Paz-Barzola, D.; Navarrete, E.C.; Romero-Crespo, P.; Salgado, B. Heavy metals in rivers affected by mining activities in ecuador: pollution and human health implications. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2021, 250, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, P.; Venhauerova, P.; Strnad, L. Speciation and mobility of arsenic and antimony in soils and mining wastes from an abandoned Sb–Au mining area. Appl. Geochem. 2023, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.M.; Radzinski, R.; Ghahreman, A. Review of arsenic metallurgy: Treatment of arsenical minerals and the immobilization of arsenic. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 174, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R.G.; Jayaweera, L.D. Arsenic in Gold Processing. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 1992, 9, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudert, L.; Bondu, R.; Rakotonimaro, T.V.; Rosa, E.; Guittonny, M.; Neculita, C.M. Treatment of As-rich mine effluents and produced residues stability: Current knowledge and research priorities for gold mining. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 386, 121920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, J.; Han, H.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, T.Y.L.; Yang, Y.; Cao, X.; Tang, H. Arsenic removal from arsenic-containing copper and cobalt slag using alkaline leaching technology and MgNH4AsO4 precipitation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 238, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongamp, W.; Takasaki, Y.; Shibayama, A. Arsenic removal from copper ores and concentrates through alkaline leaching in NaHS media. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 98, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qing, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Zeng, L.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Cao, Z.; Wang, M.; Guan, W. A feasible strategy for deep arsenic removal and efficient tungsten recovery from hazardous tungsten residue waste with the concept of weathering process strengthening. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, T.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, G. Sustainable and reagent-free cathodic precipitation for high-efficiency removal of heavy metals from soil leachate. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 320, 121002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tymbayeva, A.A.; Mamyachenkov, S.V.; Bannikova, S.A.; Anisimova, O.S. Studying the impact of alkaline sulfide leaching parameters upon the efficiency of arsenic recovery from copper skimmings of lead production. Non-ferrous Met. 2020, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Ma, X.; Yin, X.; Zhao, X.; Yan, Z.; Lin, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Jia, Y. Arsenic removal from hydrometallurgical waste sulfuric acid via scorodite formation using siderite (FeCO3). Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, J.I.S.; Gómez, R.D.J.T.; Pinilla, M.P.; Otálora, C.A.O. Comparación de cianuro y tiourea como agentes lixiviantes de un mineral aurífero colombiano. Revista Facultad de Ingeniería 2013, 22, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubaldini, S.; Vegliò, F.; Fornari, P.; Abbruzzese, C. Process flow-sheet for gold and antimony recovery from stibnite. Hydrometallurgy 2000, 57, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MERNNR. Plan Nacional De Desarrollo Del Ecuador Del Sector Minero.; 2020.

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Ordoñez-Alcivar, R.; Arguello-Guadalupe, C.; Carrera-Silva, K.; D’orio, G.; Straface, S. History, Socioeconomic Problems and Environmental Impacts of Gold Mining in the Andean Region of Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylmore, M.G. Alternative Lixiviants to Cyanide for Leaching Gold Ores. In Gold Ore Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 447–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-M, M.; Campos-C, R. Applications of quartering method in soils and foods. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2017, 7, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. Alkaline sulfide gold leaching kinetics. Miner. Eng. 2016, 92, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).