Submitted:

26 September 2023

Posted:

27 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

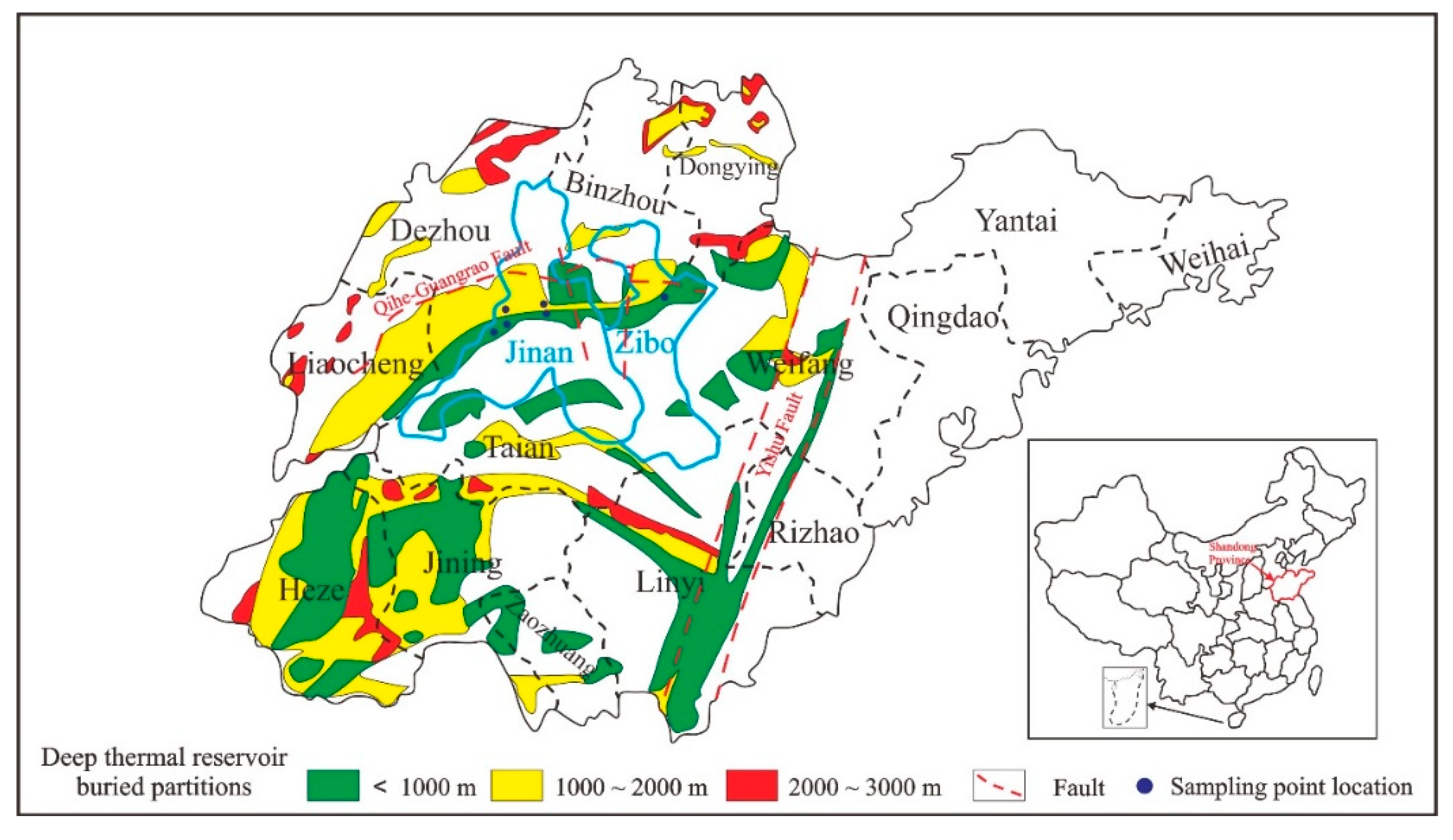

2. Geological Setting

3. Sampling and Analytical Methods

3.1. Sampling Sites

3.2. Analytical Methods

4. Results

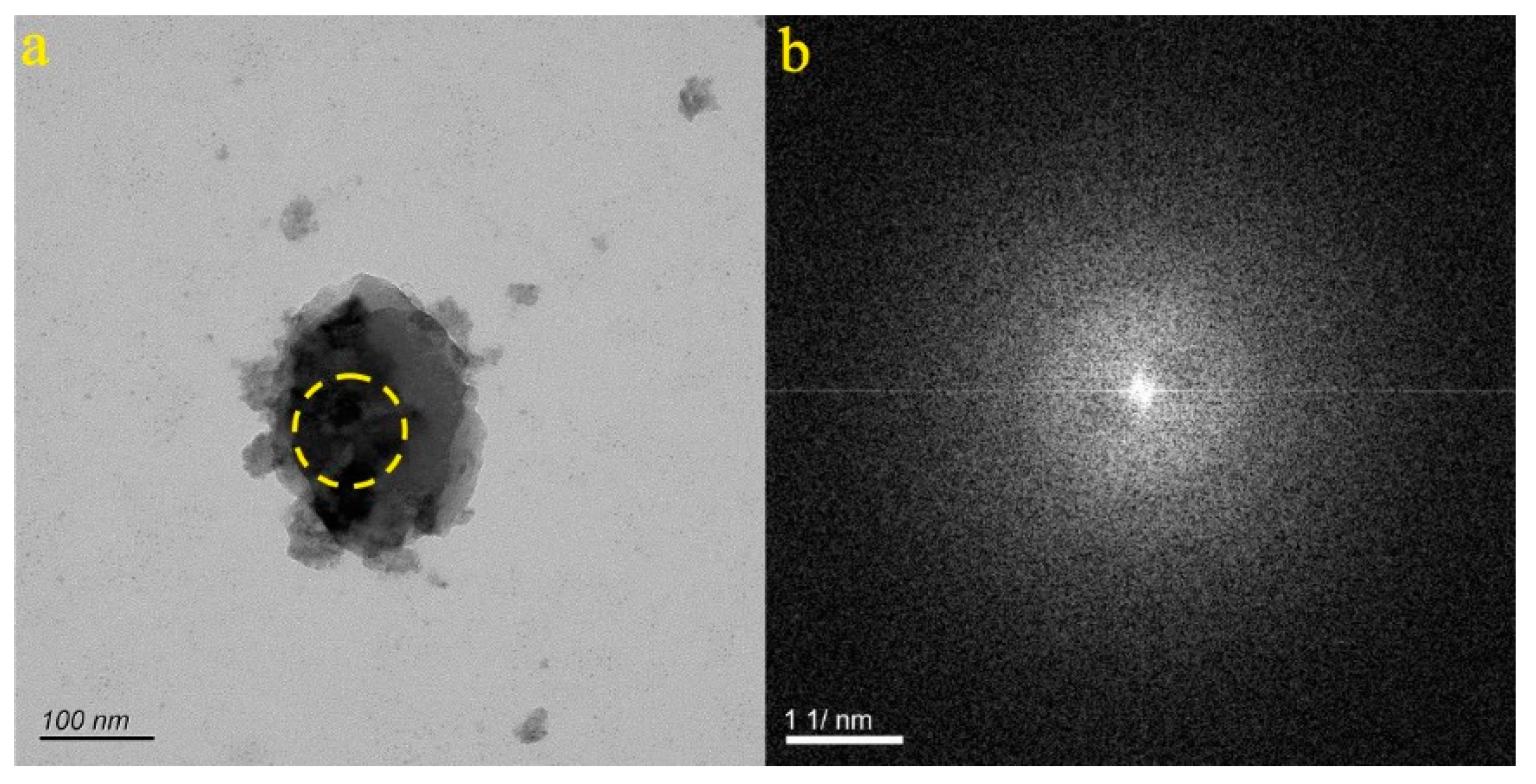

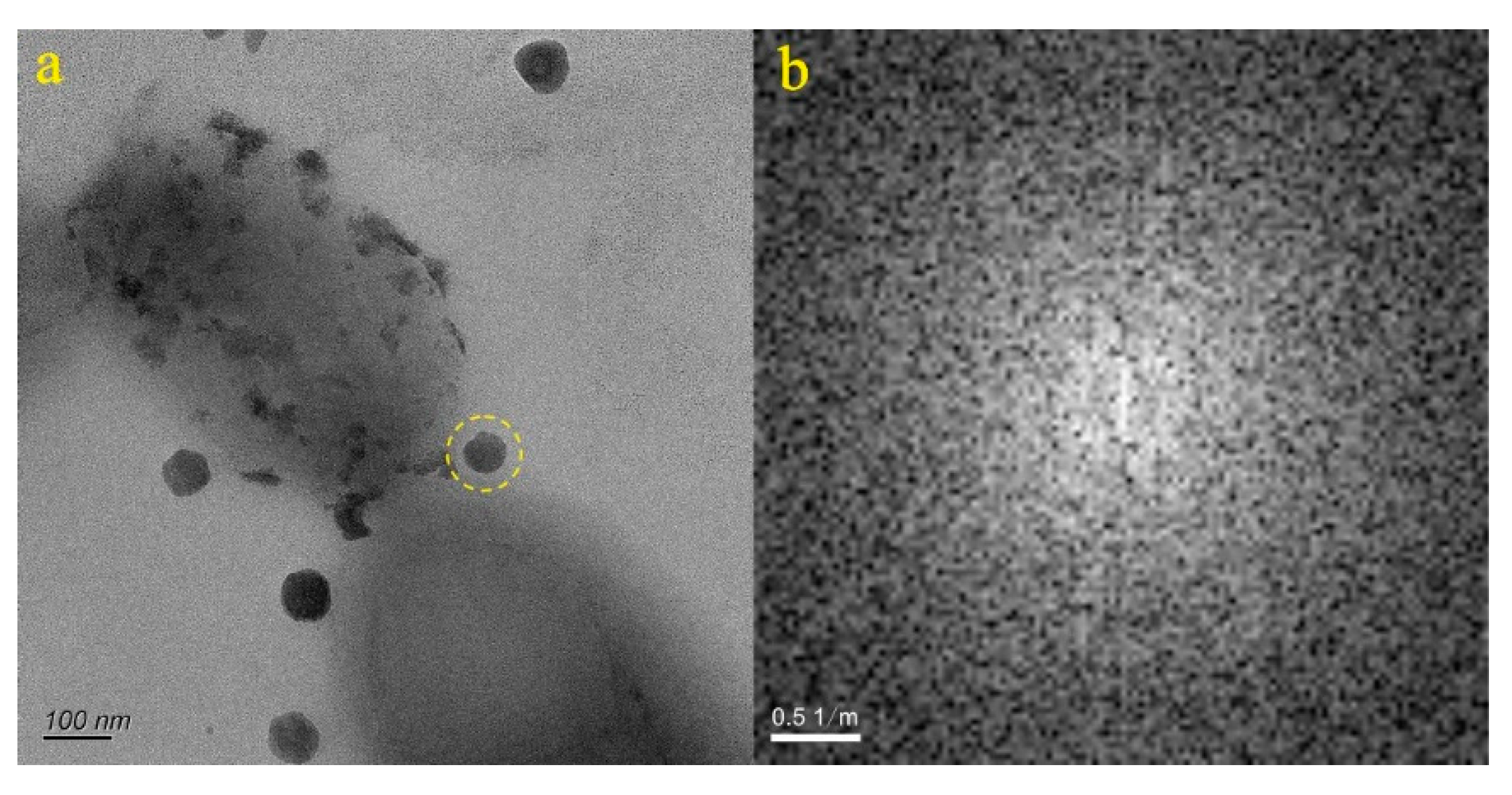

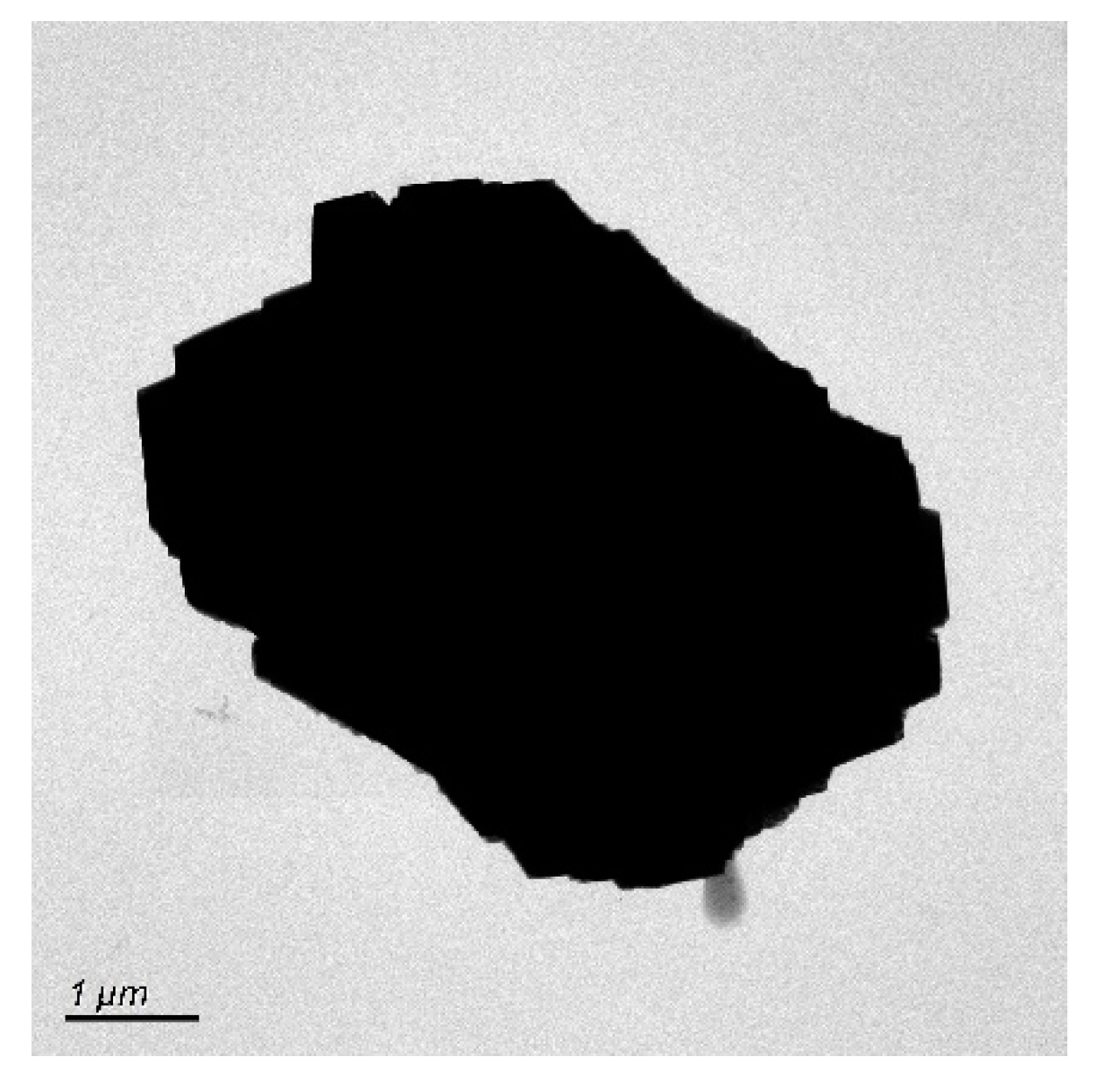

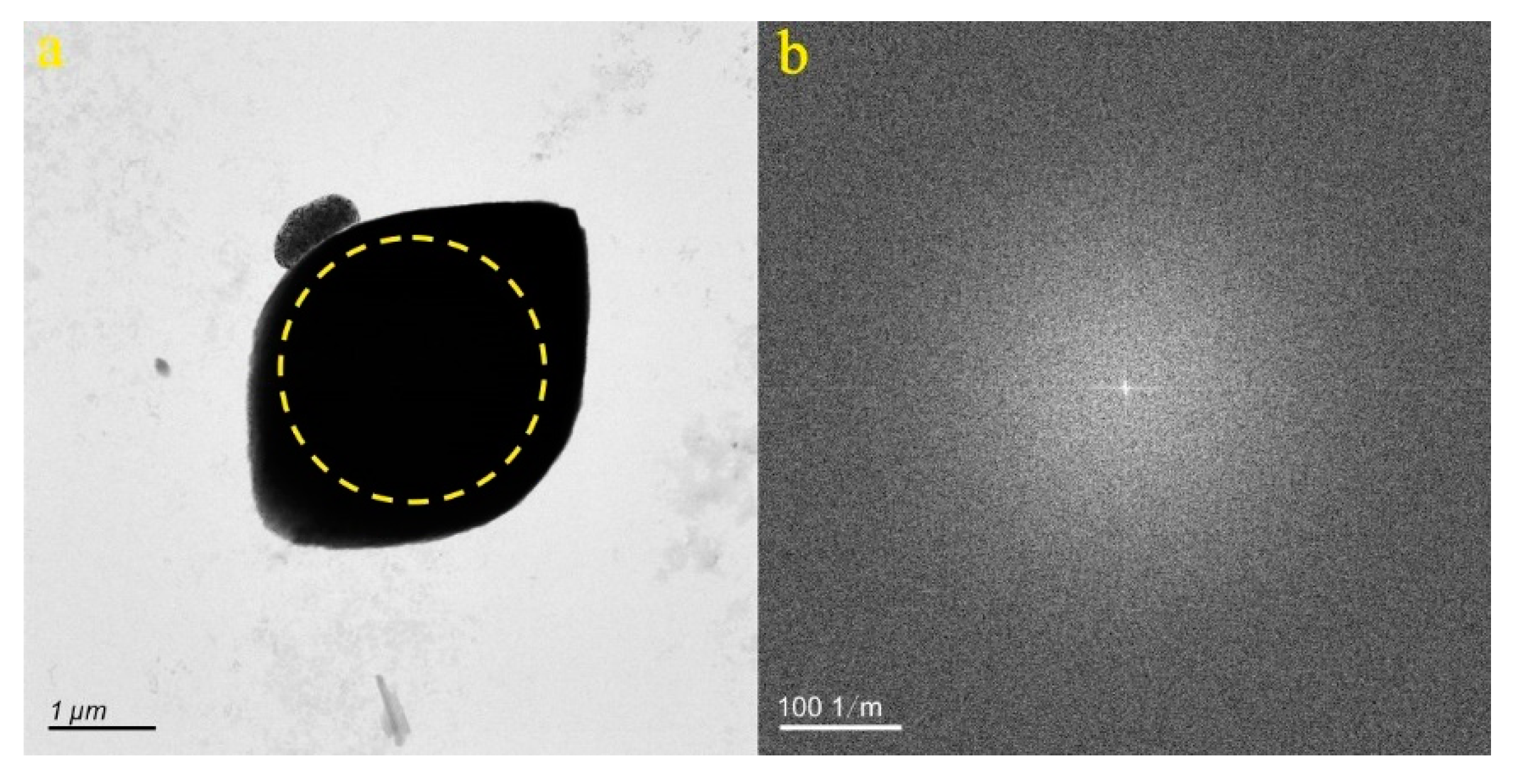

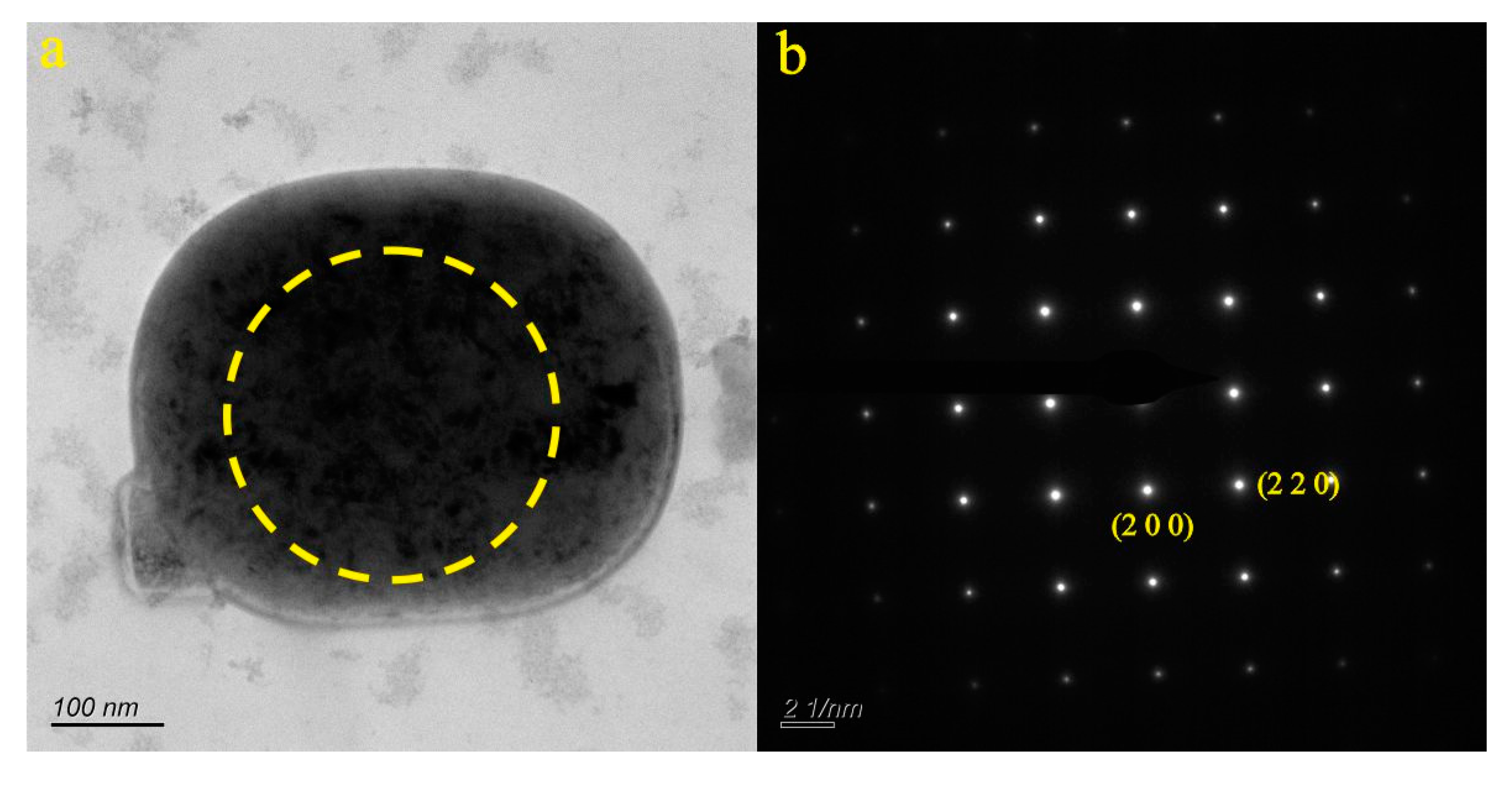

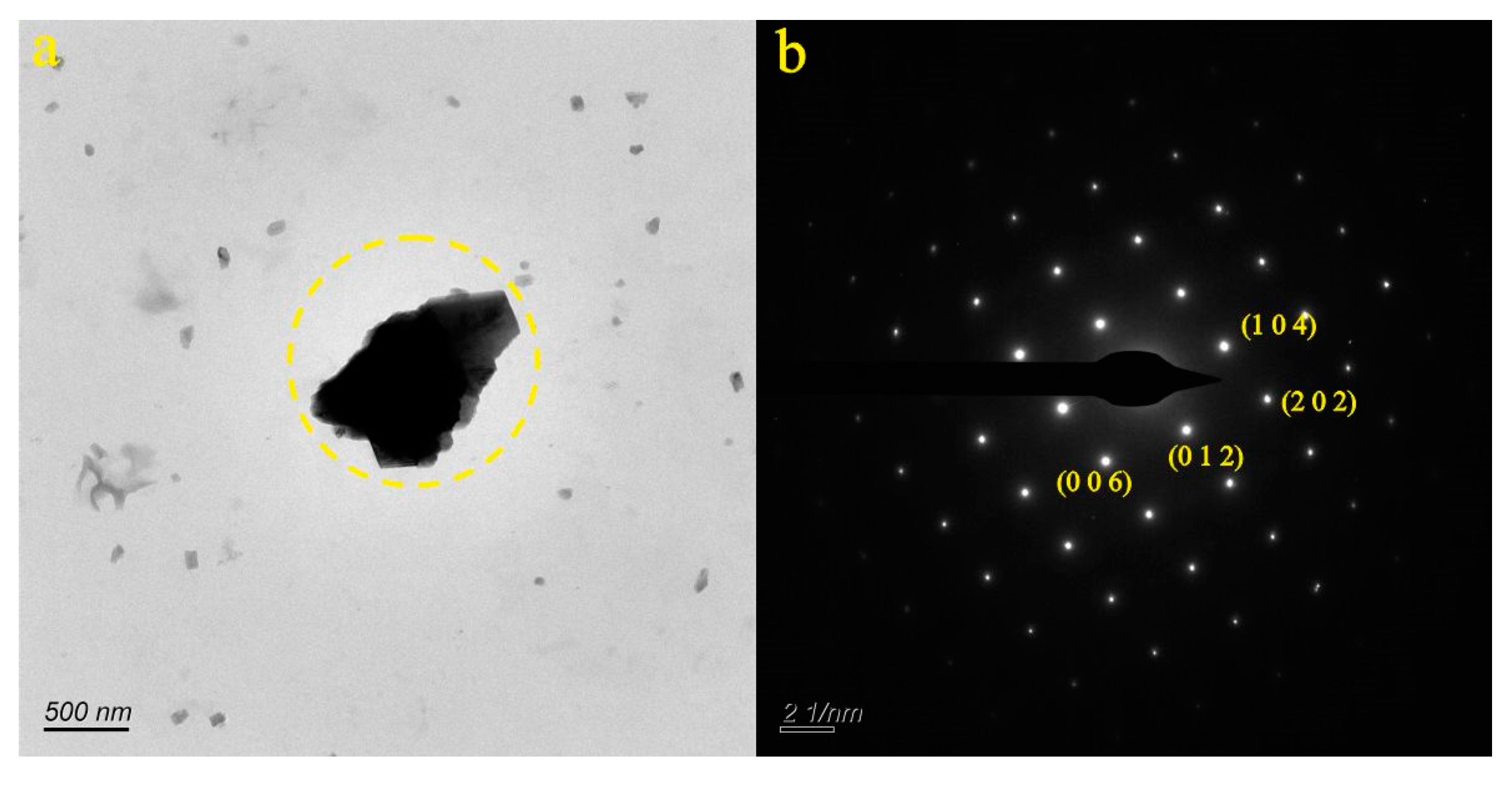

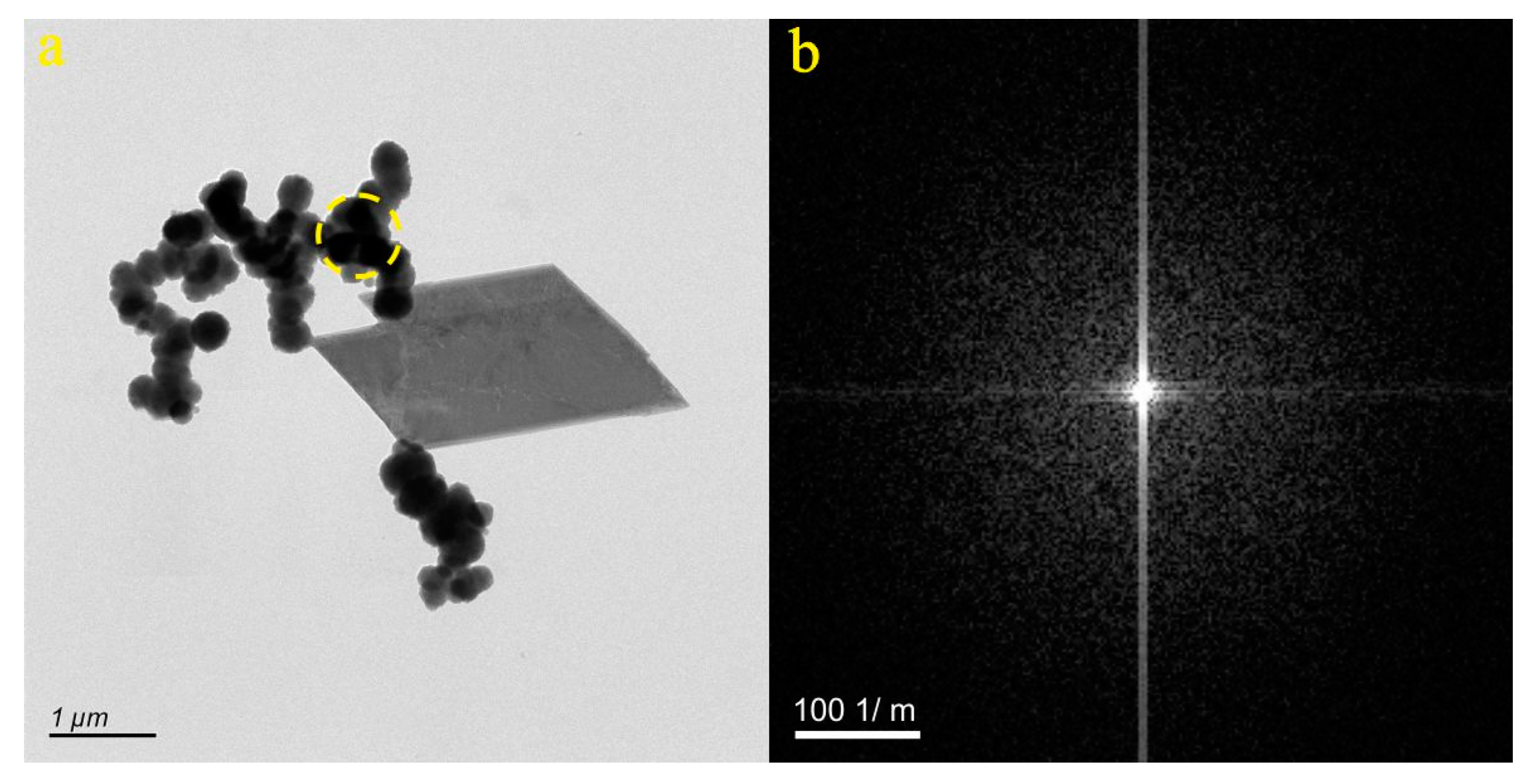

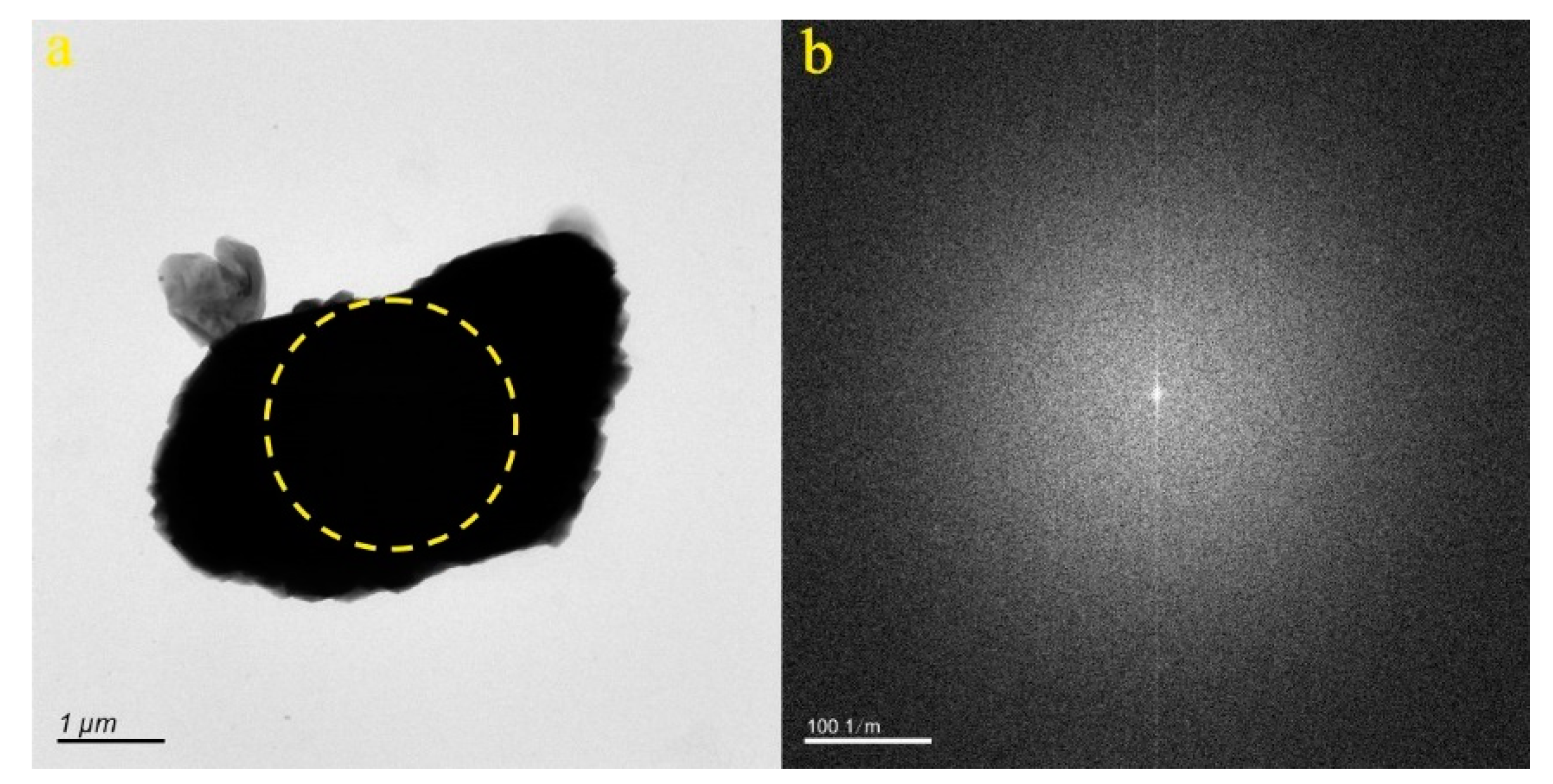

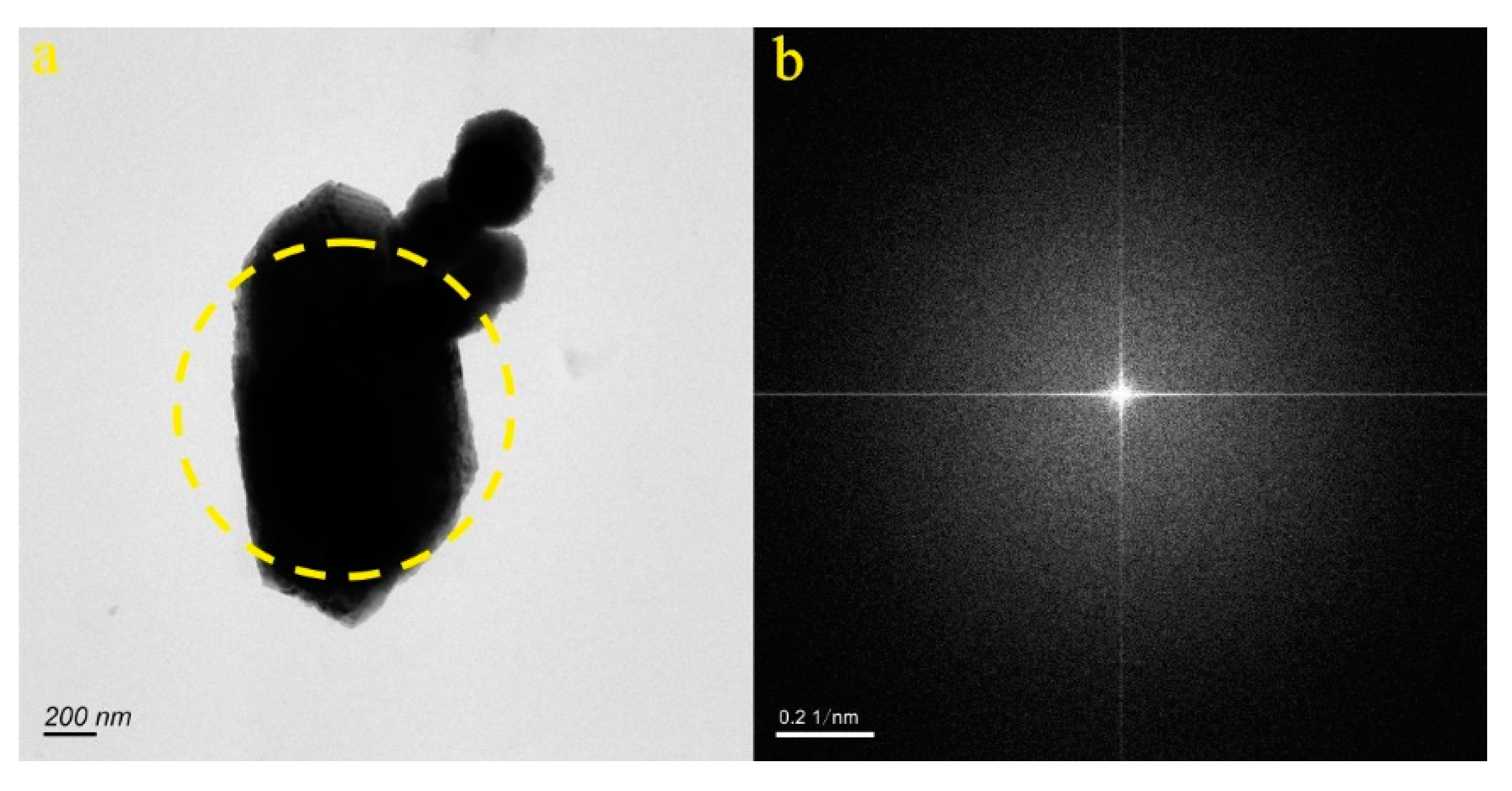

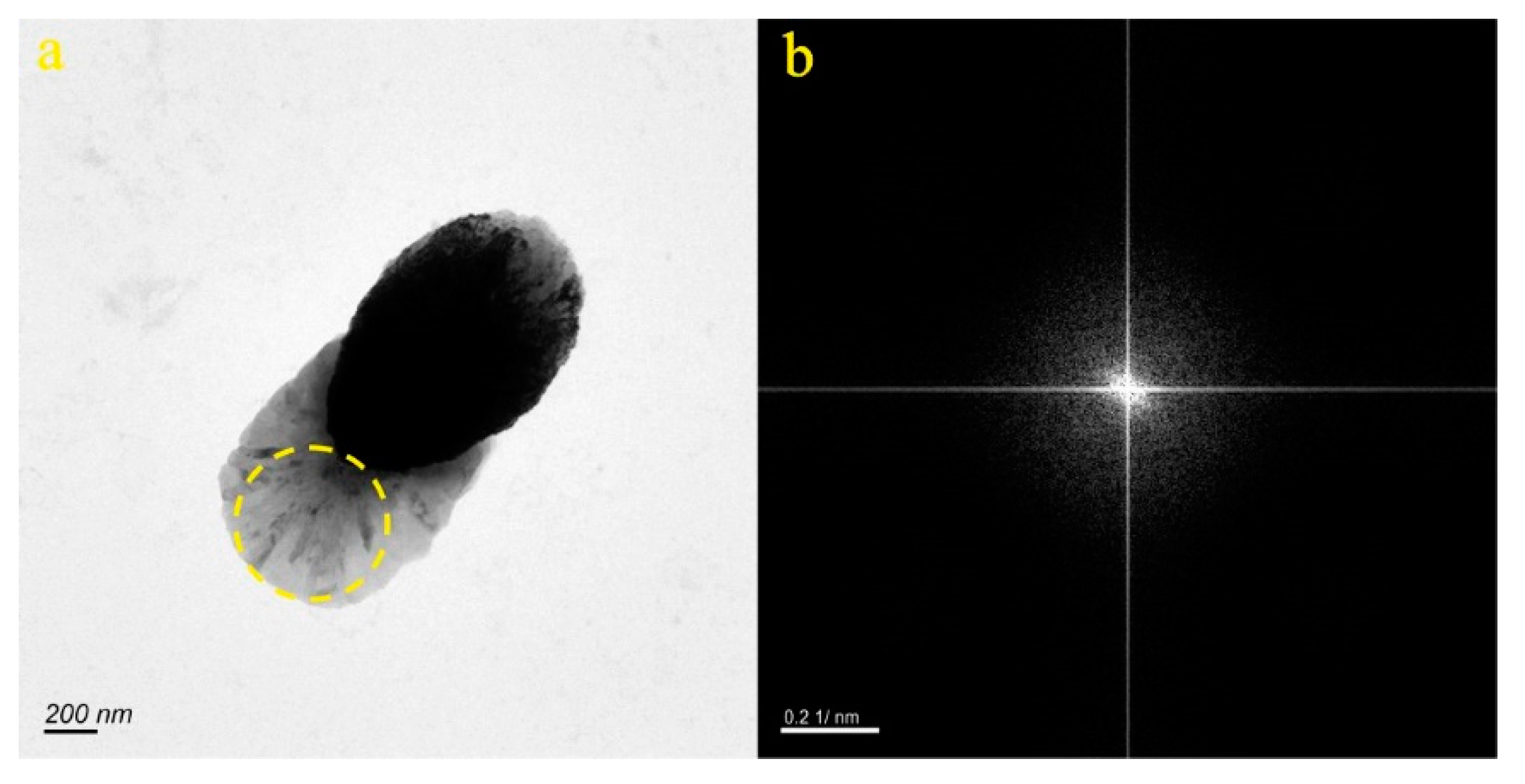

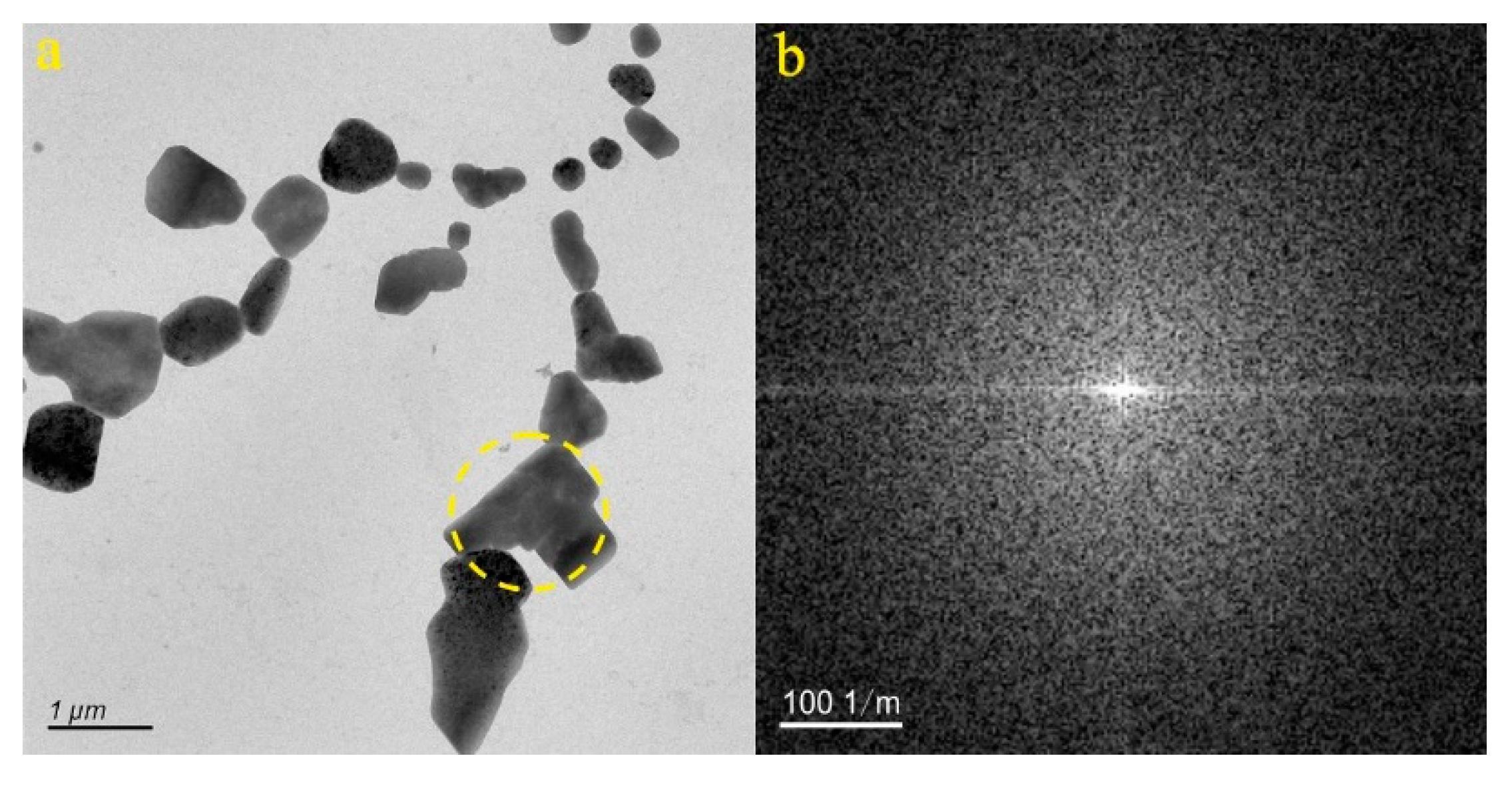

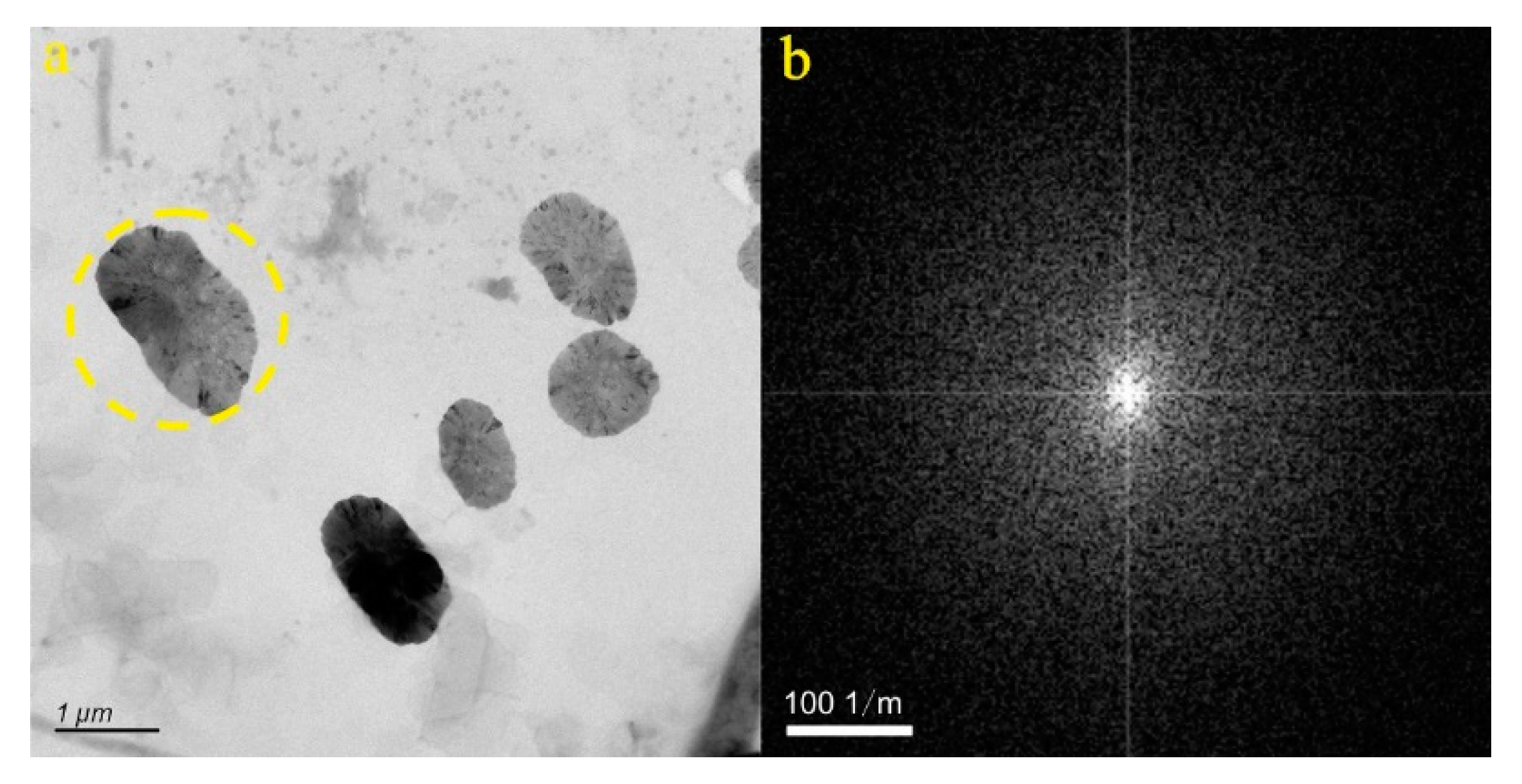

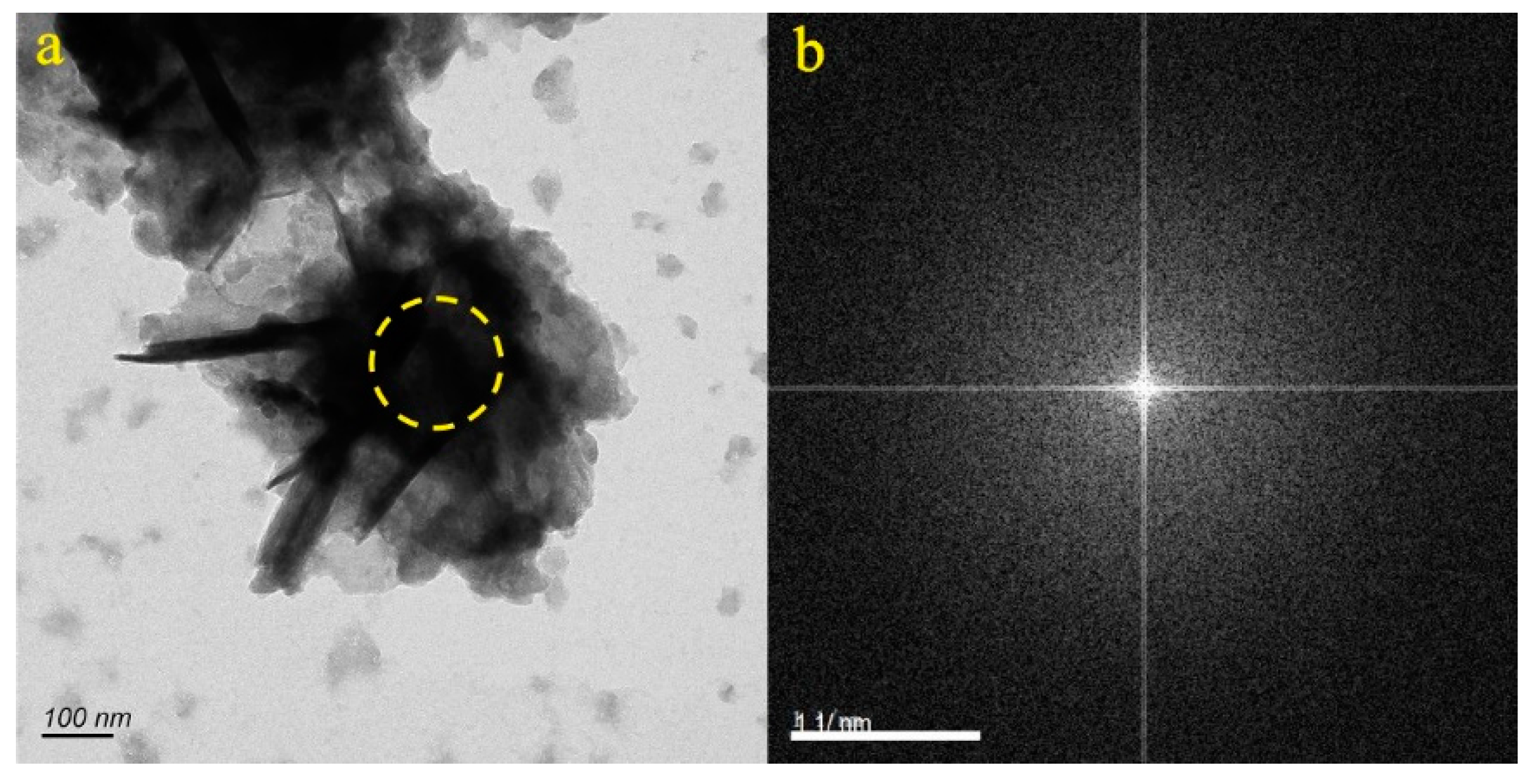

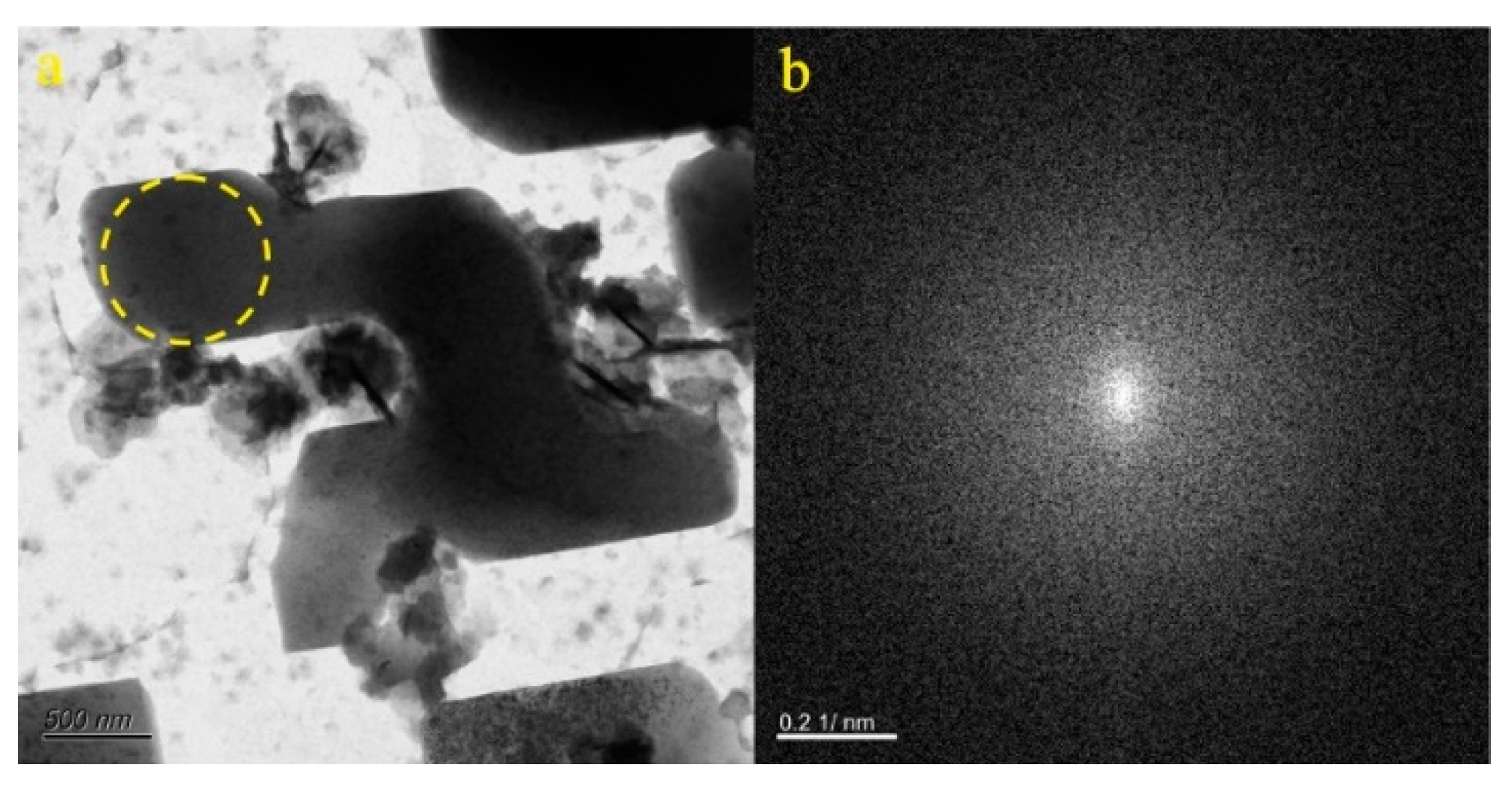

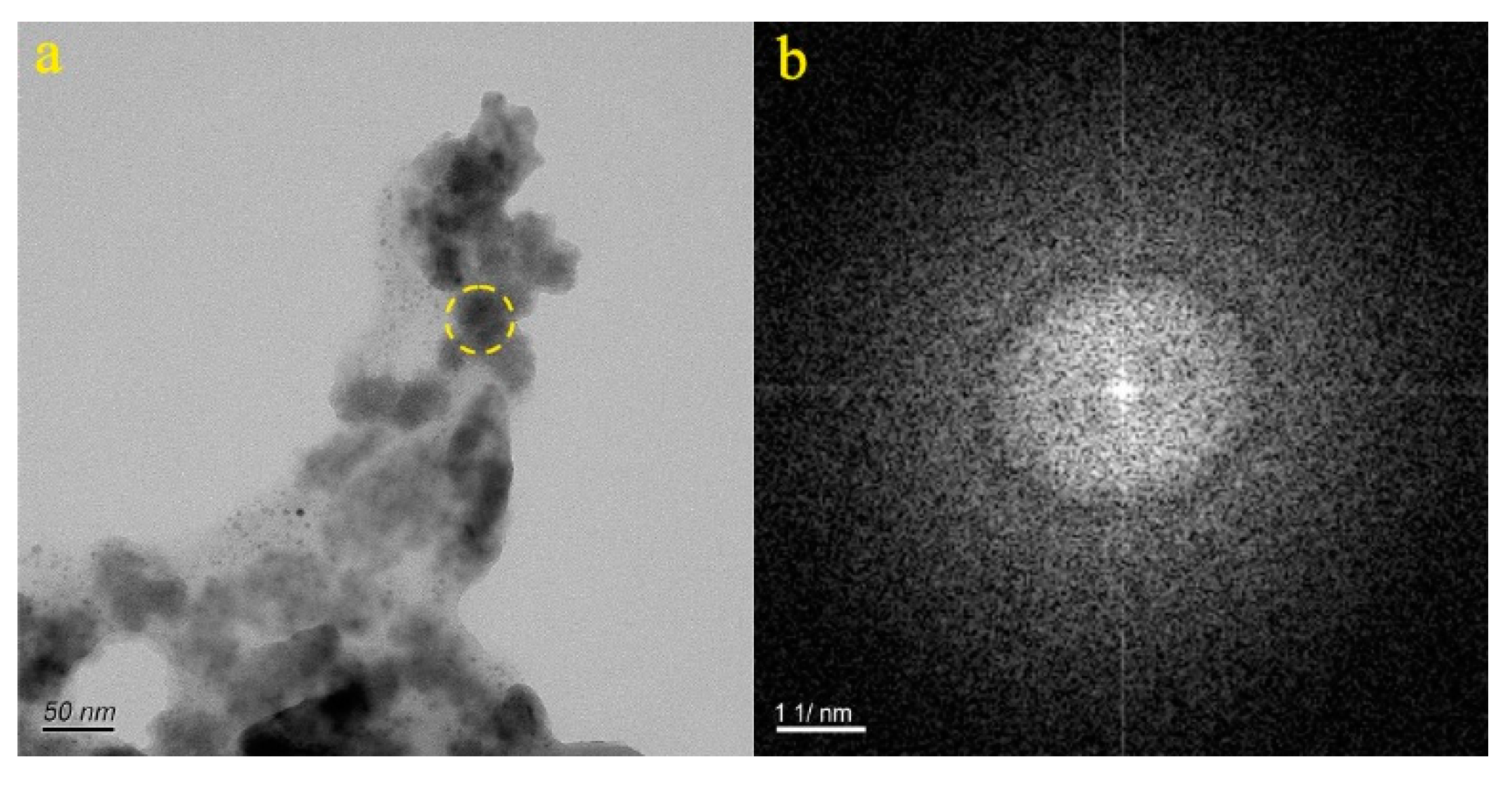

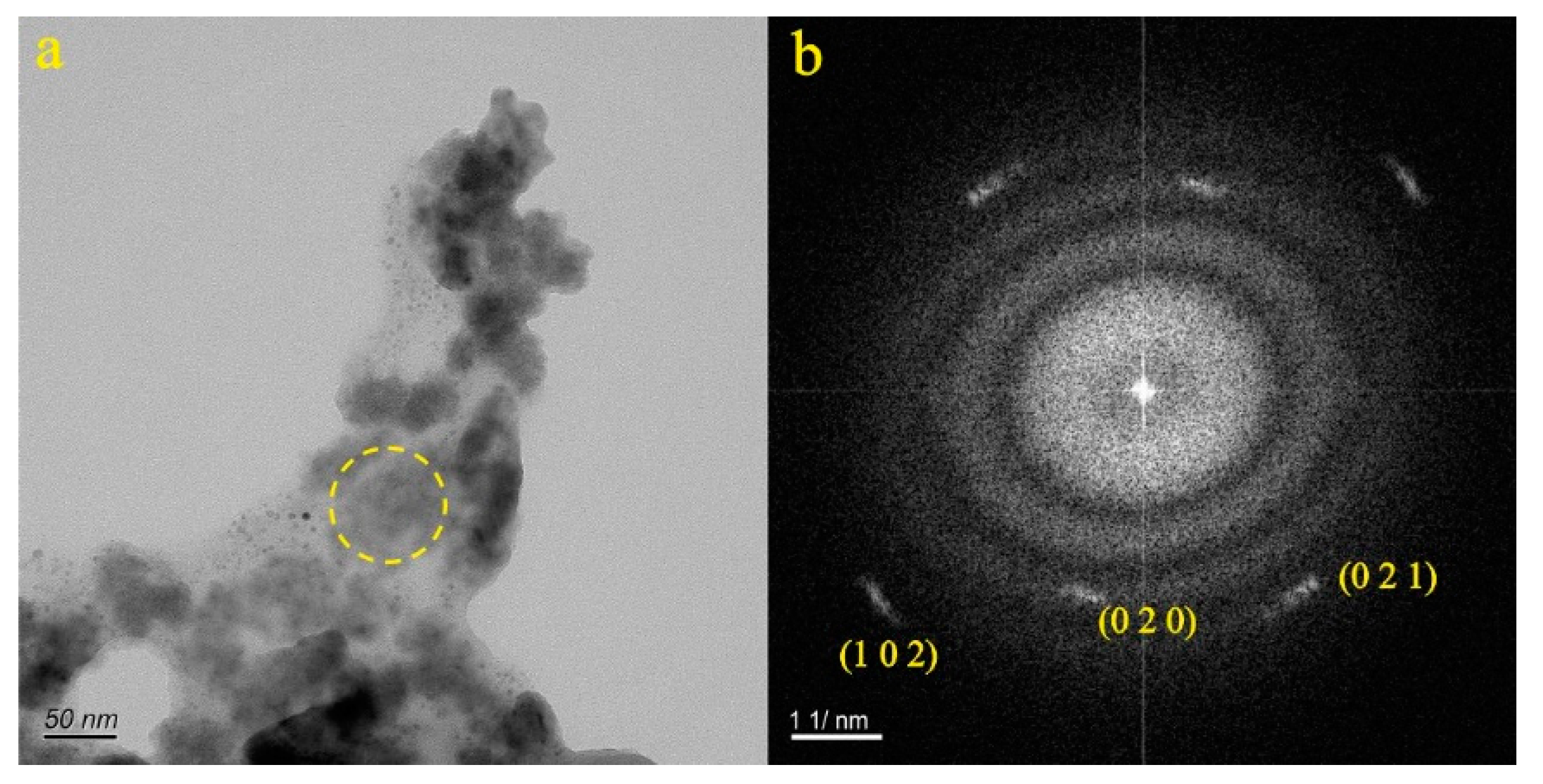

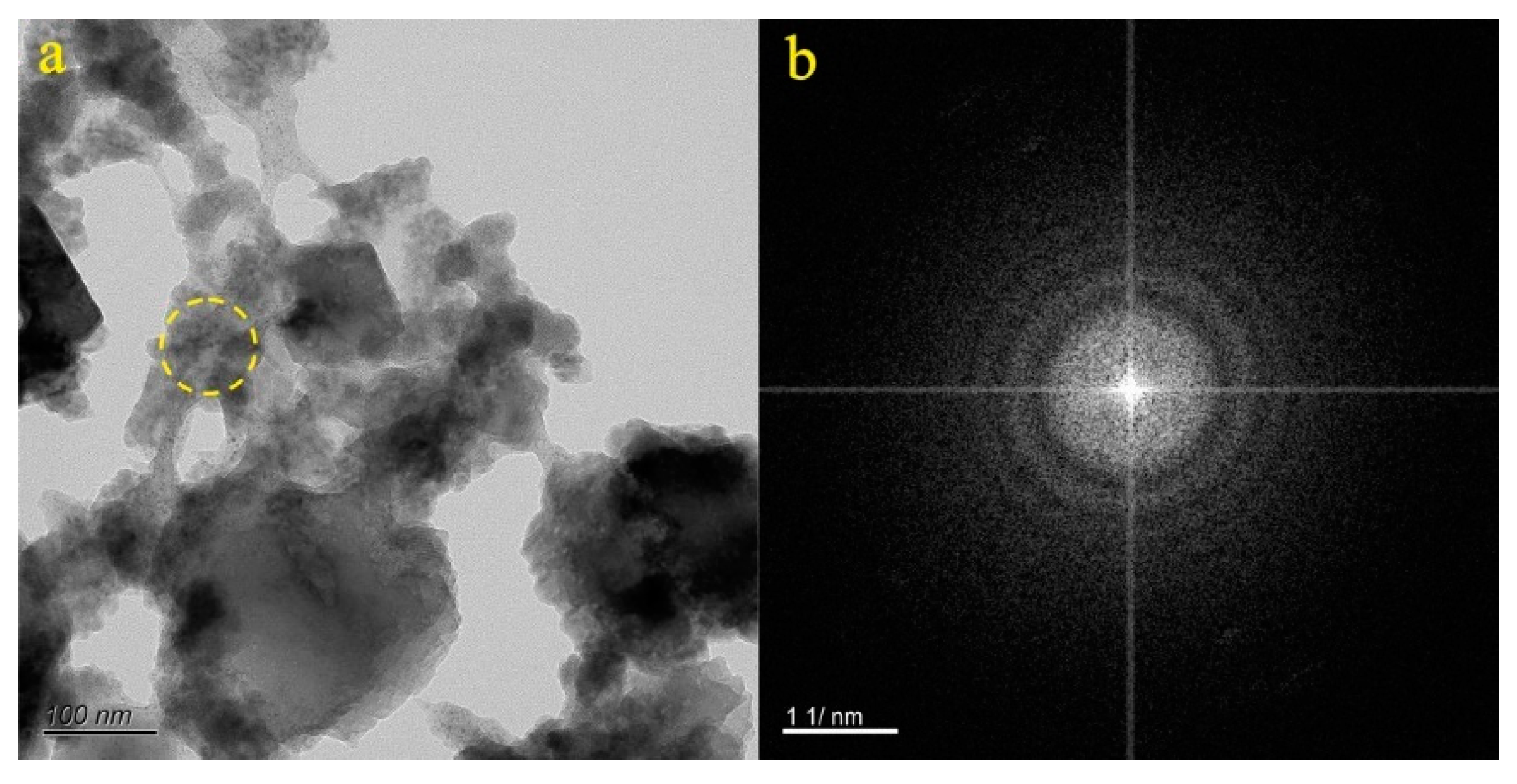

4.1. Micro-Nanoparticles in Geothermal Fluids in Jinan

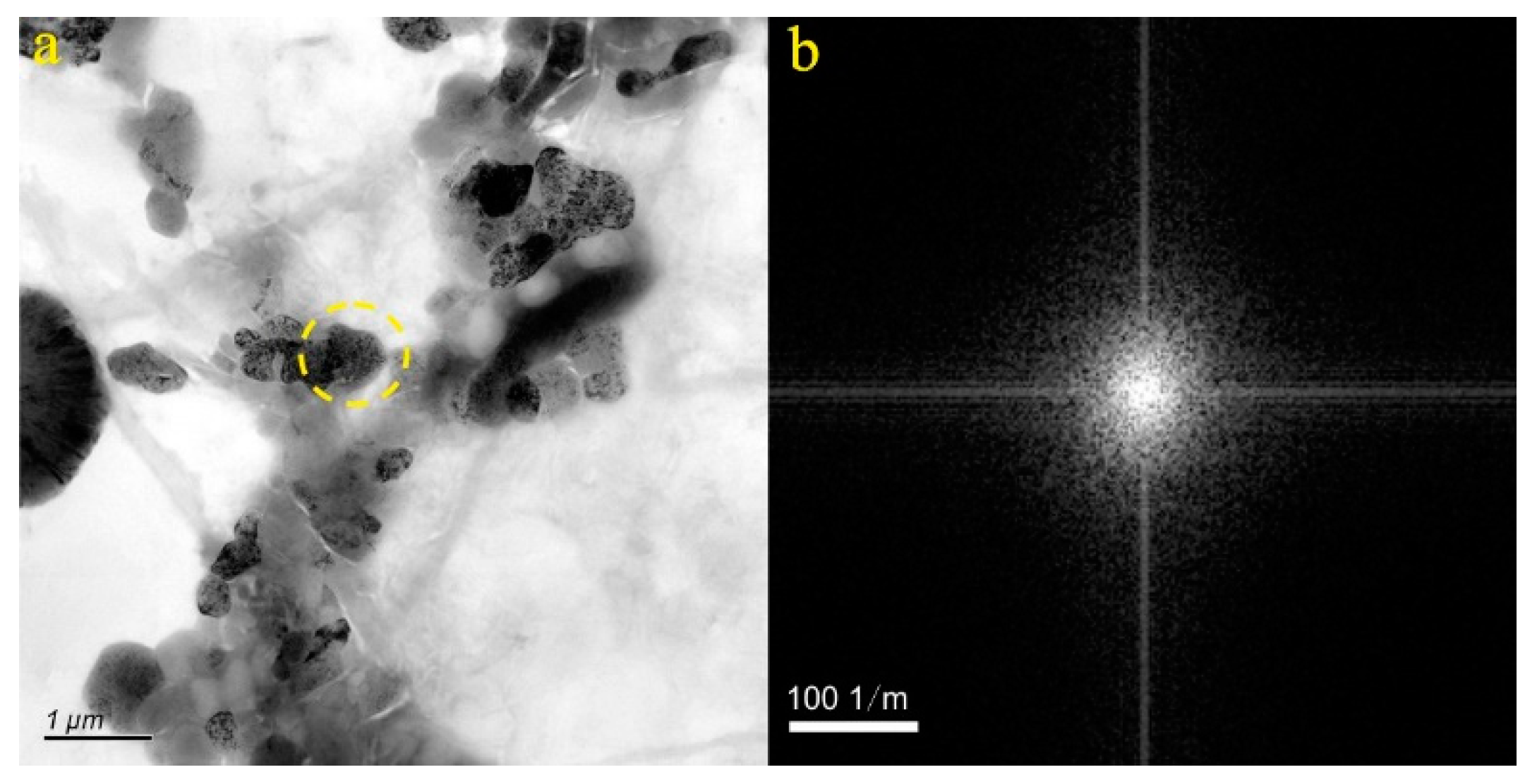

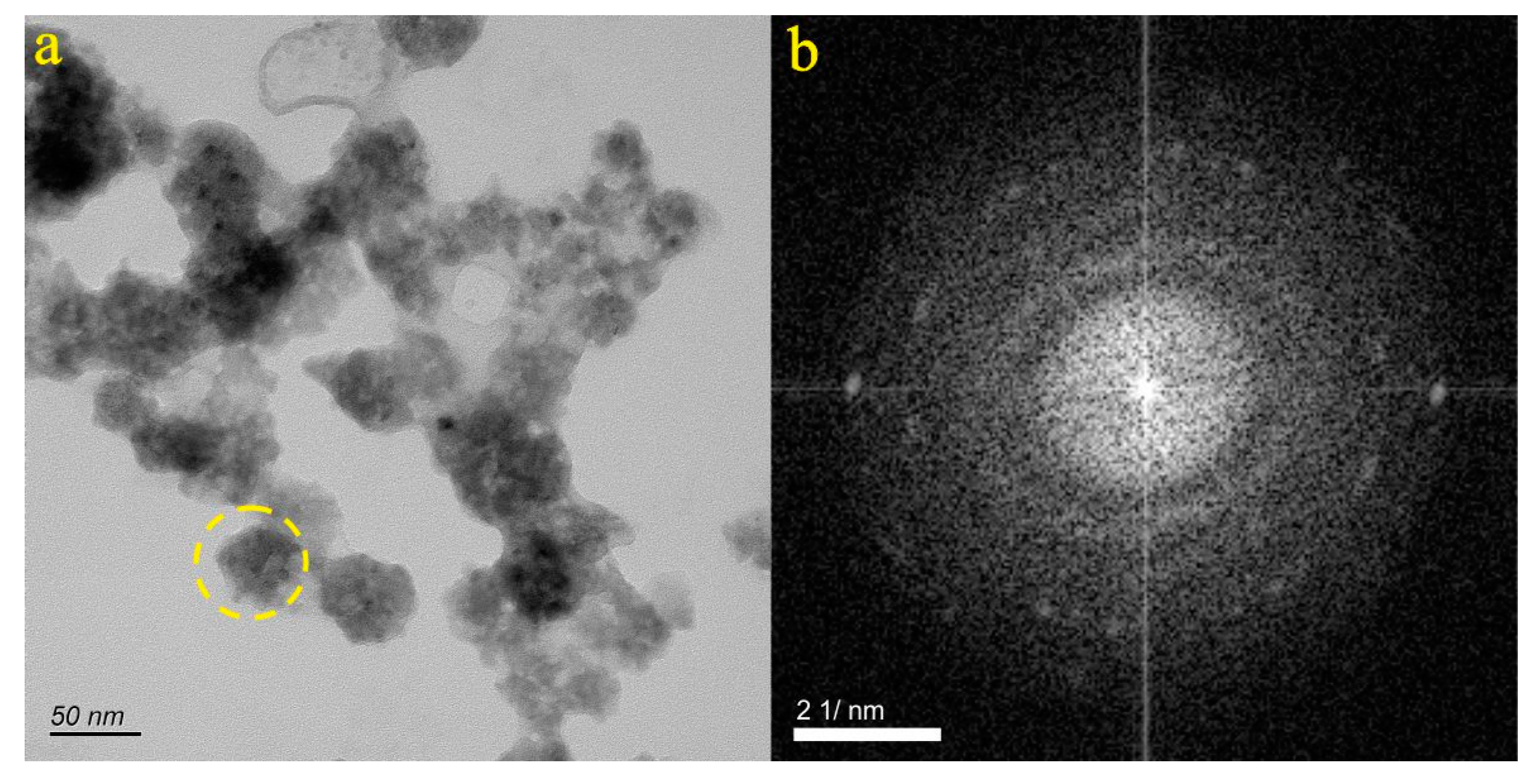

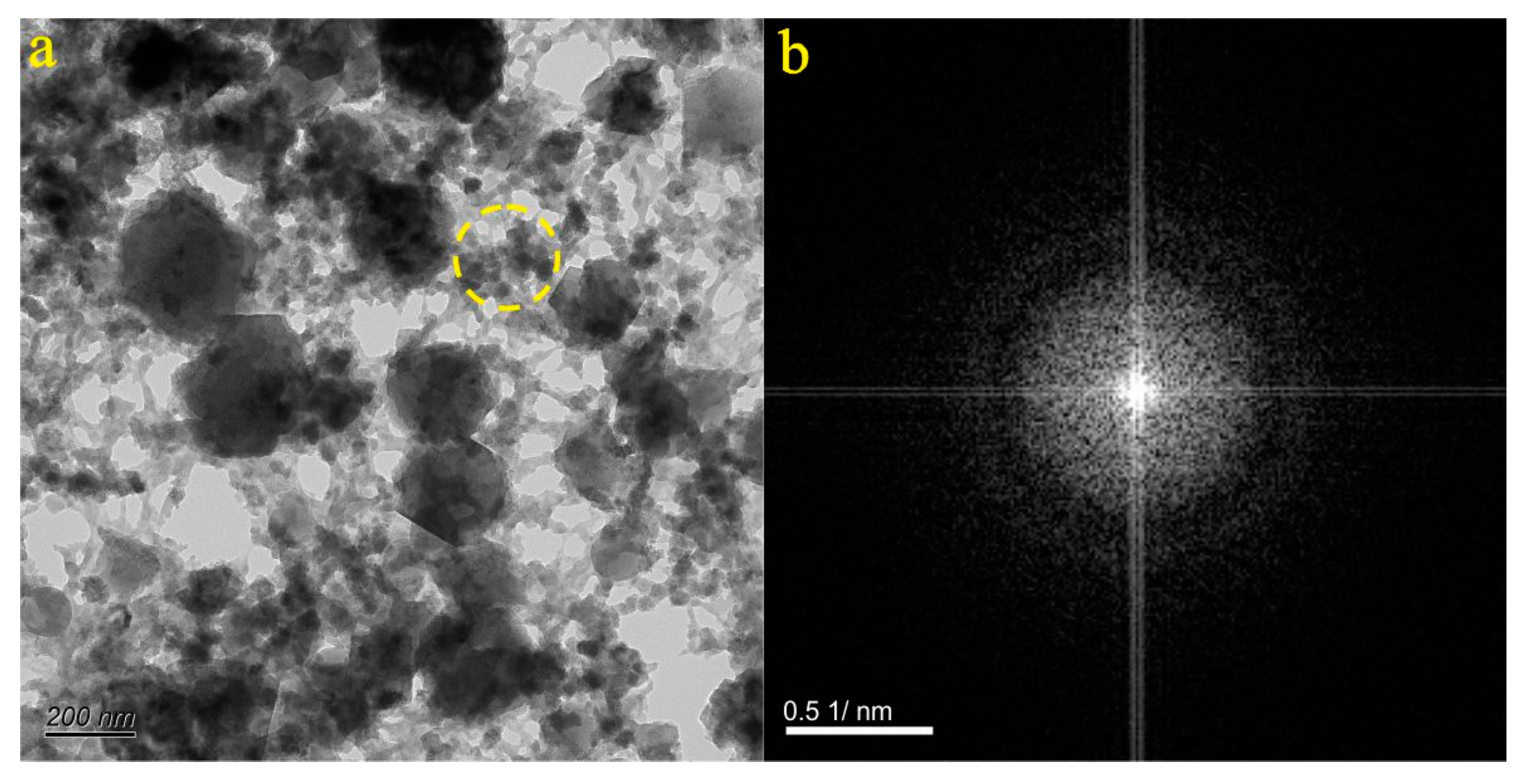

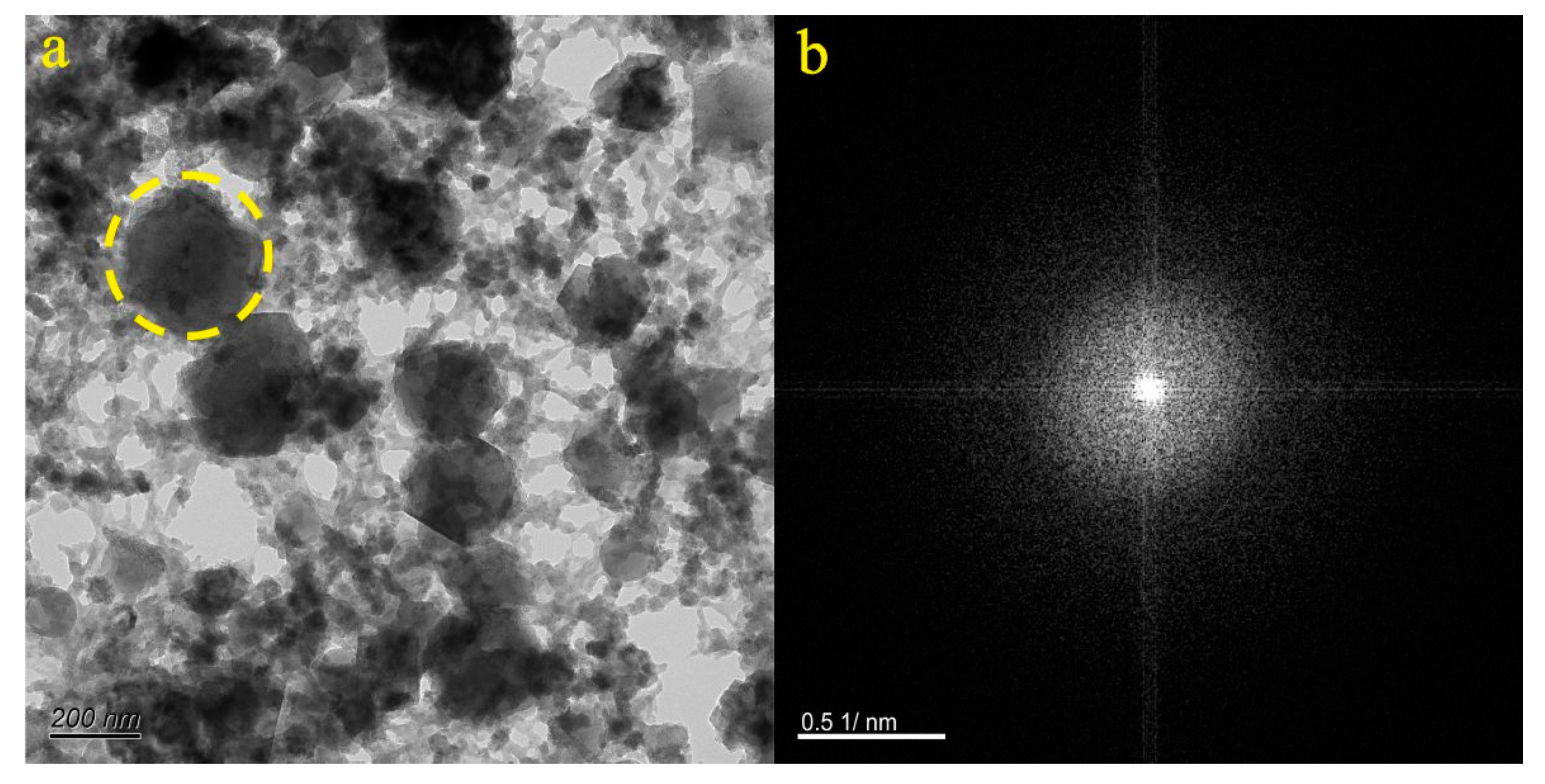

4.2. Micro-Nanoparticles in Geothermal Fluids in Zibo

5. Discussion

5.1. Characteristics of Micro-Nanoparticles in Geothermal Samples in the Central Area of Shandong Province

5.2. Characteristics and Significance of Micro-Nanoparticles in Geothermal Samples in Different Regions of the Central Area of Shandong Province

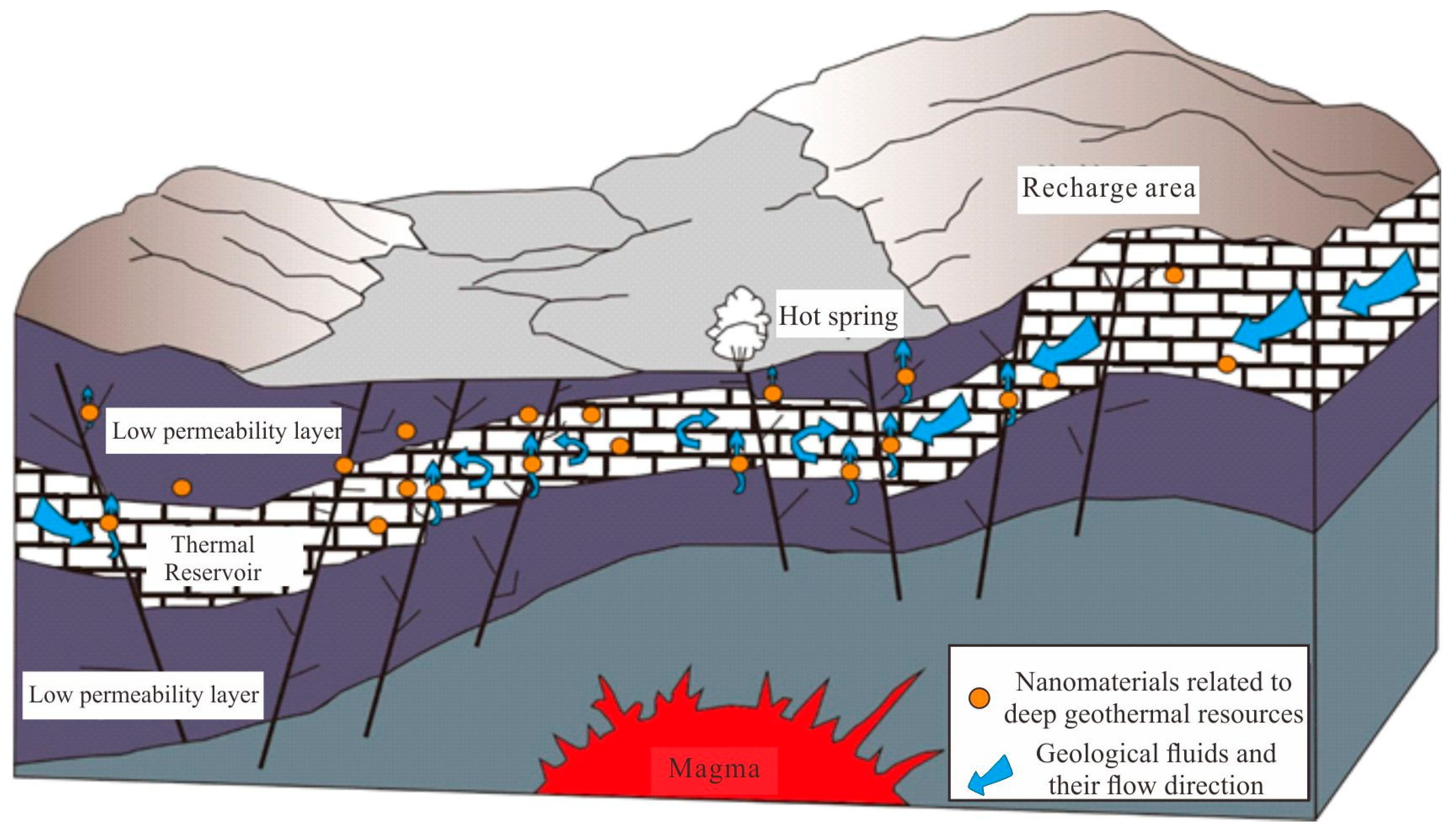

5.3. Source and Significance of the Micro-Nanoparticles in the Geothermal Fluids

5.4. Application Prospects of Nanomaterials in Fluids in Deep Geothermal Resource Exploration

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Chen, M.X.; Wang, J.Y. Review and prospect on geothermal studies in China. Acta Geophysica sinica. 1994, 37, 320–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.B.; He, L.J.; Wang, J.Y. Compilation of heat flow data in the China continental area (3rd edition). Chinese Journal of geophysics. 2001, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.L.; Wang, L.S.; Liu, S.W.; Li, C.; Han, Y.B.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Cai, J.G. Distribution characteristics of terrestrial heat flow in Jiyang depression. Science in China (Series D). 2003, 33, 384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.B.; Zhu, C.Q.; Xu, M.; Shan, J.N.; Tian, Y.T.; Rao, S.; Wang, J.Y. Thermal history reconstruction of sedimentary basin and its application. Geophysics in China. 2009, 785. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.G.; Guo, Y.S. Heat Foundation. Beijing Science Press. 2009.

- Li, Y.Y.; Duo, J.; Zhang, C.J.; Chi, G.X.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, F.F.; Xing, Y.F.; Zhang, B.J. Genetic relationship between geothermal energy and hydrothermal uranium deposits: research progress and method. Geological Review. 2020, 66, 1361–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, M.; Wang, B.Y.; Ai, Y.F.; Fang, G. Geophysical analysis of geothermal resources and temperature structure of crust and upper mantle beneath Guanzhong Basin of Shaanxi, China. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2021, 43, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.J.; Zhao, P. Yunnan-Tibet geothermal zone: geothermal resources and typical geothermal systems. Beijing Science Press. 1999.

- Wang, G.L.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J.Y.; Lin, W.J.; Liu, Z.M.; Wang, W.L. Evaluation of geothermal resources potential in China. Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 2017, 38, 449–459. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Nan, G.; et al. Geothermal resources in Tibet of China: current status and prospective development. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.L.; Lu, C. Stimulation technology development of hot day rock and enhanced geothermal system driven by carbon neutrality target. Geol. Resour. 2023, 32, 85–95+126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.L.; Liu, Y.G.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W. The status and development trend of geothermal resources in China. Earth Sci. Front. 2020, 27, 001–009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Lin, W.; Liu, F.; Gan, H.; Wang, S.; Yue, G.; Long, X.; Liu, Y. Theory and survey practice of deep heat accumulation in geothermal system and exploration practice. Acta Geologica Sinica 2023, 97, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjing Lin, Guiling Wang, Haonan Gan, Shengsheng Zhang, Zhen Zhao, Gaofan Yue, Xiting Long, 2022. Heat source model for Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) under different geological conditions in China, Gondwana Research. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.Q.; Li, F.; Zheng, H.S.; Ding, Z.Q. Geophysical technologies and their application effects for exploration of deep metallic mineral. Comput. Tech. Geophys. Geochem. Exploration. 2010, 32, 495–499. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, F.; Luo, D.F.; et al. The effects of applying integrated geophysical method to the prospecting for the Jiangcheng concealed lead Yunnan Province. Geophys. Geochem. Exploration. 2015, 39, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, F.L.; Gong, J.J.; Bao, Z.Y.; Xie, S.Y.; Cui, F.; Su, Z.W.; Zeng, Y.H. Application of hydrocarbons in concealed tungsten ore prediction in Weijia, Nanling Area. Earth Sci. —J. China Univ. Geosci. 2012, 37, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Jiao, J.J.; Huang, J.; Huang, R. Multivariate statistical evaluation of trace elements in groundwater in a coastal area in Shenzhen, China. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 147, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, S.H. Effect of groundwater components on hydroxyl radical production by Fe (Ⅱ) oxygenation. Earth Sci. 2017, 42, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J. A technique for detecting concealed deposits by combining geogas particle characteristics with element concentrations. Metal mine 2009, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Frimmel, F.H.; Niessner, R. Nanoparticles in the water cycle. (No Title). 2010.

- Banfield, J.F.; Zhang, H. Nanoparticles in the environment. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2001, 44, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.; He, Z.L.; Harris, W.G. Natural nanoparticles: implications for environment and human health. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 861–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consani, S.; Carbone, C.; Dinelli, E.; Balić-Žunić, T.; Cutroneo, L.; Capello, M.; Salviulo, G.; Lucchetti, G. Metal transport and remobilisation in a basin affected by acid mine drainage: the role of ochreous amorphous precipitates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 15735–15747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Bo, B.; Zhang, P.; et al. Carbonaceous nanoparticles in Zibo hot springs: Implications for the cycling of carbon and associated elements. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4009–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Li, C.; Liu, S.W.; Li, H.; Xu, M.J.; Yu, D.Y.; Jia, C.Z.; Wei, G.Q. Terrestrial heat flow distribution in Kuqa foreland basin, Tarim, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2005, (04), 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.C. Study on buried geologic body and fractured atmospheric field. Final report of the project funded by the National Natural Science Foundation. 2013.

- Liu, X.H.; Tong, C.H. Preliminary study on elements transportation in underground vitrification form. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 2009, 26, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.S.; Zhao, Y.X.; Wang, S.J.; Zhang, H.L. Analysis of the rules of water enrichment in the geothermal field, northern Jinan, Shandong Province. Earth Environ. 2008, (02), 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.C.; Xue, H.M.; Li, T.F.; Yang, H.R.; Liu, L.F. Enriched characteristics of late Mesozoic mantle under the Sulu orogenic belt: geochemical evidence from gabbro in Rushan. Atca Petrologica Sinica 2005, 21, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.X.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, F.W. Geochemical environment of trace element strontium (Sr) enriched in mineral waters. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2004, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.Z.; Duan, X.M.; Gao, Z.D.; Wang, Q.B.; Li, W.P.; Yin, X.L. Hydrochemical study of karst groundwater in the Jinan spring catchment. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2007, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Cao, X.H. Preliminary study on geothermal resources in Nanding, Zibo. Professional Committee of China Energy Research Society. Selected papers of the third National Geothermal Academic Conference. Beijing Science Press. 1989, 91-99.

- Yang, S.; Zhang, H.D.; Li, W.Z.; Wu, L. Genesis of geothermal anomaly in Southern Zhangdian district of Zibo City. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2005, 32, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Q.K.; Han, J.J.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, L.X. Research on forming condition of geothermal resource in Zhangdian region of Zibo City. Shandong Land Resour. 2009, 25, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.L.; Sui, H.B.; Kang, F.X.; Li, C.S.; Wei, S.M.; Yu, L.Q.; Li, Y. Hydrogeochemical characteristics and formation mechanism of the karst thermal reservoir in the northern edge of the Luzhong Uplift. Carsologica Sinica. 2023, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.K.; Cao, J.J.; Chen, J.; Yi, J. The research of particles carried by ascending gas flow from Qingmingshan Cu-Ni sulfide deposit in Guangxi Province. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 2017, 33, 831–842. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, W.M.; Smedley, P.L. Residence time indicators in groundwater: the East Midlands Triassic sandstone aquifer. Appl. Geochem. 2000, 15, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.M.; Cao, J.J.; Mi, Y.B.; Liu, X.; Hu, G. Study of nanoparticles in groundwater of Yagongtang Cu-Pb-Zn-S polymetallic deposit, Hunan Province. Metal Mine. 2020, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo, J. The basic characteristics of the Yangbajing geothermal field-A typical high temperature geothermal system. Eng. Sci. 2003, 5, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.Q.; Qiu, N.S.; Chang, J.; Rao, S. Current situation of geothermal resource industry and the future development of geothermal education. Chin. Geol. Educ. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.J.; Liu, Z.M.; Wang, W.L.; Wang, G.L. The assessment of geothermal resource potential of China. Geol. China 2013, 40, 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, C.H.; Li, J.C.; Ge, L.Q. A new form of elemental migration and its influence on geochemical environments. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. 2002, 29, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; et al. A study of metal-bearing nanoparticles from the Kangjiawan Pb-Zn deposit and their prospecting significance. Ore Geol. Rev. 2019, 105, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Cheng, S.; Luo, S.; et al. Study of particles in the ascending gas of ruptures caused by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Applied Geochemistry. 2017, 82, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.H. Present situation and trending of geochemical prospecting techniques for metal mineral resources. Contrib. Geol. Miner. Resour. Res. 2000, 15, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | Size (nm) | Concentration (Particles/mL) | Aquifer |

|---|---|---|---|

| CJQ | 154.0-482.4 | 0.56-1.8 105 | Ordovician Majiagou Formation |

| JR3 | 113.3-501.9 | 0.96-2.1 105 | Ordovician Majiagou Formation |

| QJZ | 171.4-574.8 | 3.1-3.7 105 | Ordovician Majiagou Formation |

| BL | 152.6-469.5 | 1.6-3.9 105 | Ordovician Majiagou Formation |

| DR2 | 151.4-457.0 | 0.62-1.5 105 | Ordovician |

| Zibo | 196.4-232.4 | 0.71-3.2 105 | Ordovician |

| Sample | C | O | Ca | Cu | Si | S | Cl | Mg | Na | Al | K | Fe | Sr | F | Te | In | Pd | Ba | |

| CJQ | JN-1 | 54.83 | 15.88 | 9.81 | 18.57 | 0.68 | 0.21 | ||||||||||||

| JN-2 | 7.51 | 8.74 | 62.23 | 20.54 | 0.61 | 0.35 | |||||||||||||

| JR3 | JN-3 | 5.38 | 20.31 | 58.06 | 12.20 | 2.35 | 1.11 | 0.44 | 0.12 | ||||||||||

| JN-4 | 8.87 | 2.48 | 12.96 | 40.33 | 0.31 | 35.01 | |||||||||||||

| QJZ | JN-5 | 14.99 | 32.02 | 33.77 | 15.61 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 1.42 | ||||||||||

| BL | JN-6 | 7.27 | 33.00 | 1.66 | 9.27 | 3.65 | 0.14 | 44.99 | |||||||||||

| JN-7 | 9.52 | 15.78 | 56.10 | 16.47 | 1.97 | 0.13 | |||||||||||||

| JN-8 | 17.38 | 30.78 | 30.00 | 13.07 | 1.63 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 5.79 | |||||||||||

| DR2 | JN-9 | 21.55 | 42.49 | 10.62 | 8.96 | 0.41 | 12.05 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 2.55 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| JN-10 | 18.68 | 1.82 | 12.57 | 0.26 | 34.23 | 0.29 | 32.12 | ||||||||||||

| JN-11 | 12.2 | 36.02 | 11.28 | 9.79 | 0.16 | 10.6 | 1.19 | 0.95 | 3.25 | 1.49 | 11.4 | 1.6 | |||||||

| JN12 | 14.1 | 4.09 | 0.33 | 15.92 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 32.92 | 0.74 | 23.6 | 7.6 | |||||||||

| Zibo | ZB-1 | 51.16 | 27.36 | 1.15 | 2.14 | 18.18 | |||||||||||||

| ZB-2 | 7.76 | 53.38 | 3.56 | 4.21 | 31.07 | ||||||||||||||

| ZB-3 | 13.55 | 21.29 | 1.93 | 12.47 | 17.48 | 33.26 | |||||||||||||

| ZB-4 | 17.95 | 46.58 | 1.56 | 11.14 | 22.75 | ||||||||||||||

| ZB-5 | 42.87 | 18.72 | 1.35 | 2.82 | 7.50 | 26.71 | |||||||||||||

| ZB-6 | 32.55 | 46.15 | 20.41 | 0.87 | |||||||||||||||

| ZB-7 | 32.42 | 29.62 | 2.02 | 9.70 | 5.47 | 20.74 | |||||||||||||

| ZB-8 | 24.61 | 31.92 | 8.99 | 14.58 | 19.87 | ||||||||||||||

| ZB-9 | 32.96 | 31.95 | 30.77 | 4.31 | |||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).